The Torah Ark of Arthur Szyk

Abstract

:1. Introduction

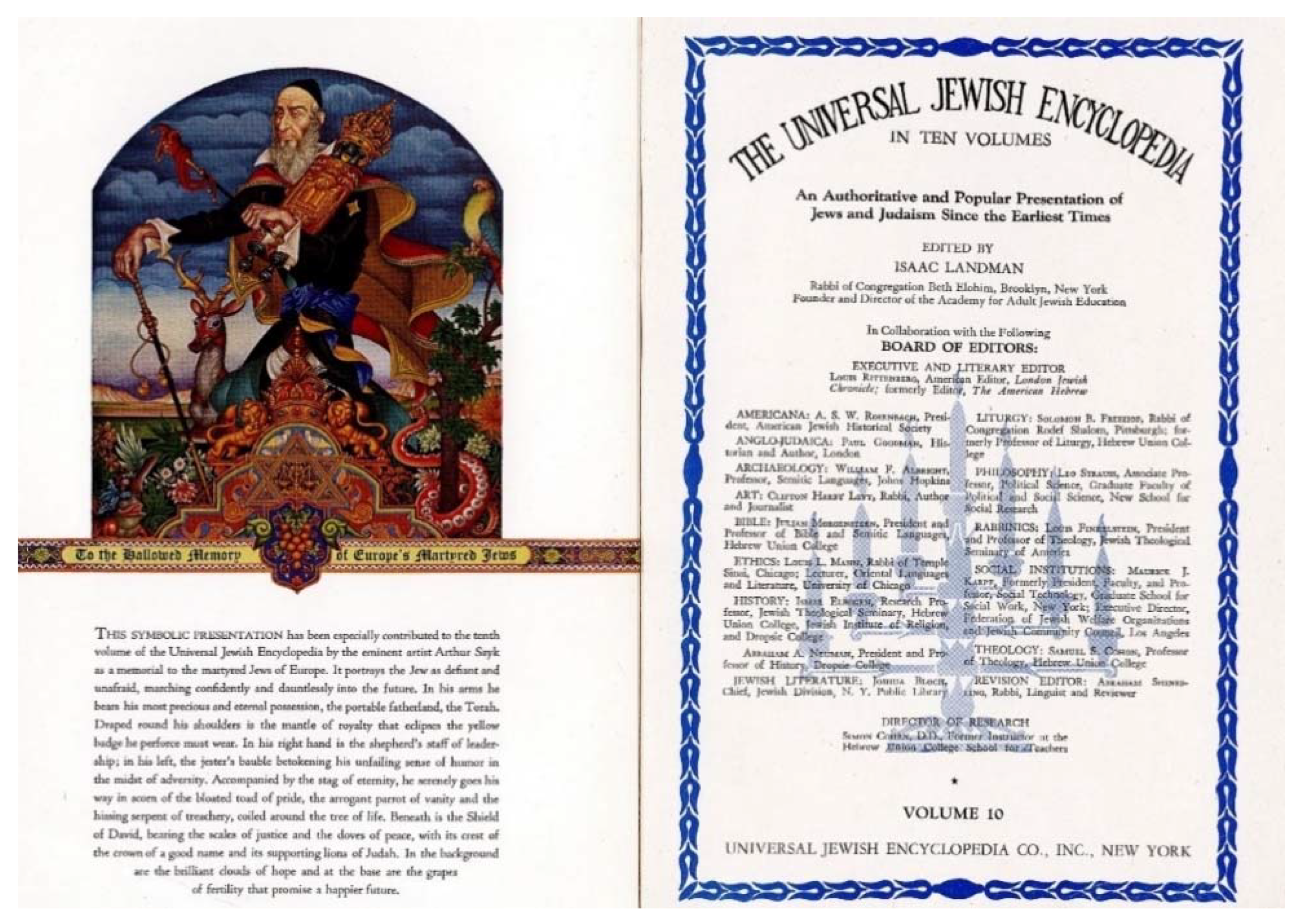

2. The Artist

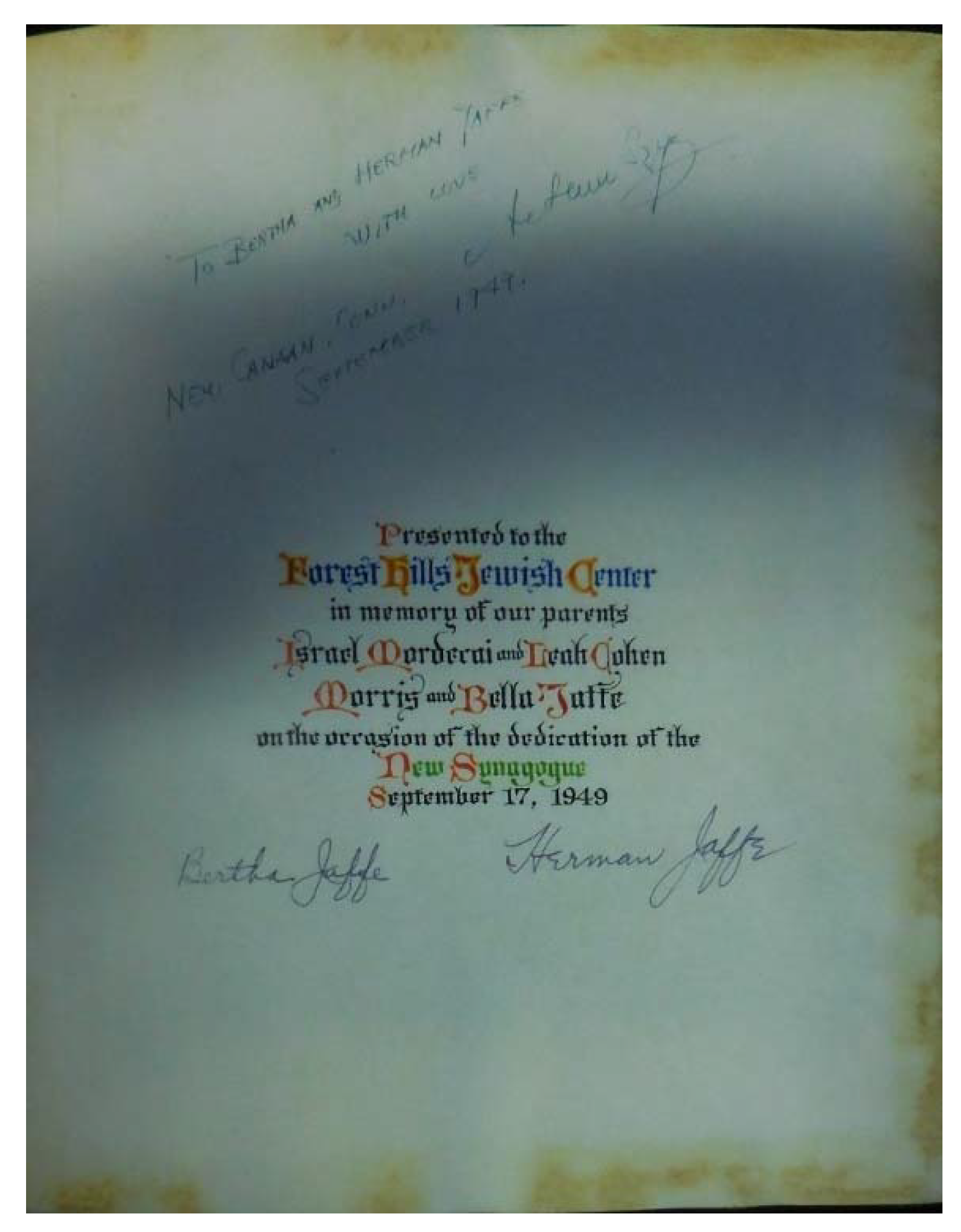

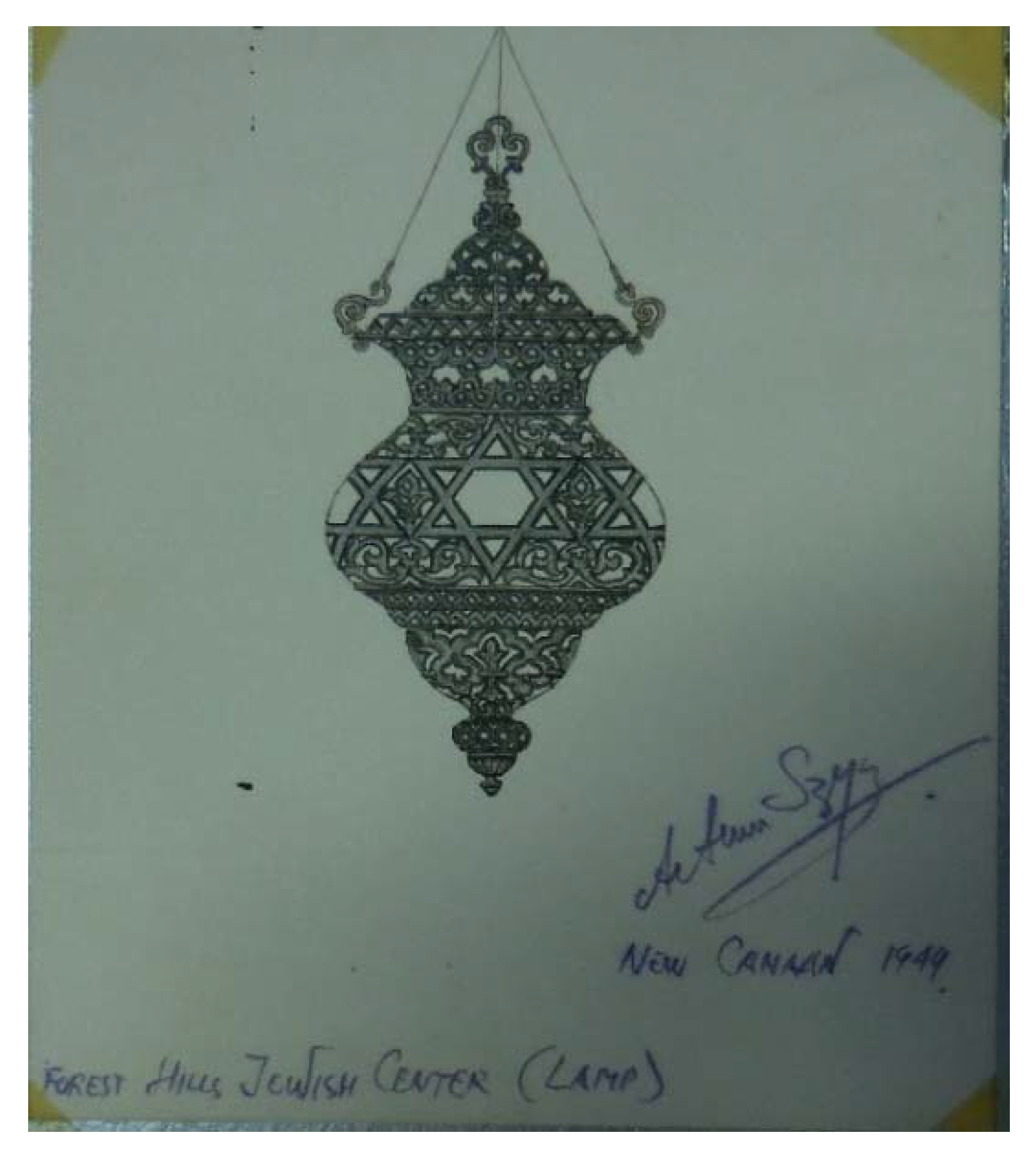

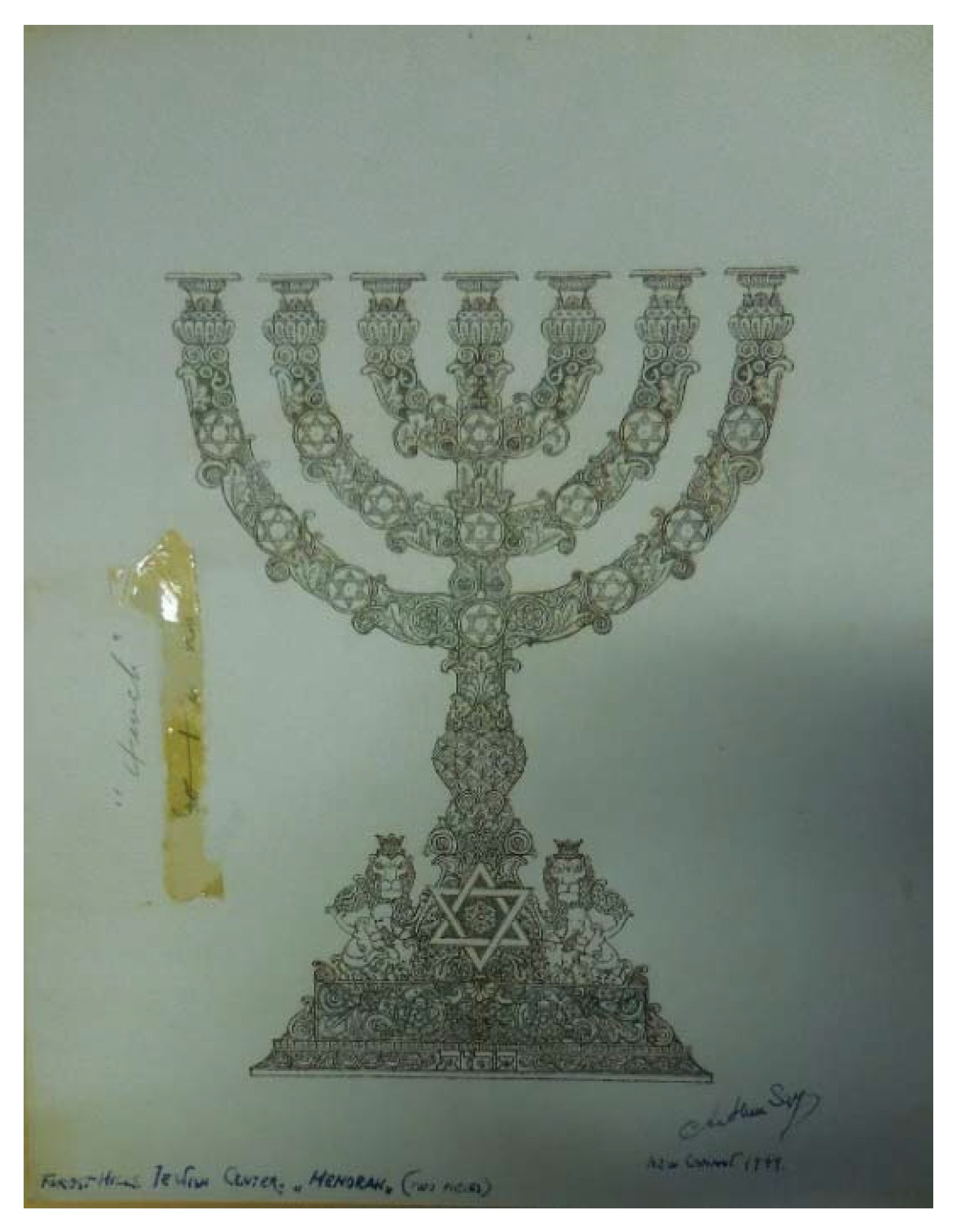

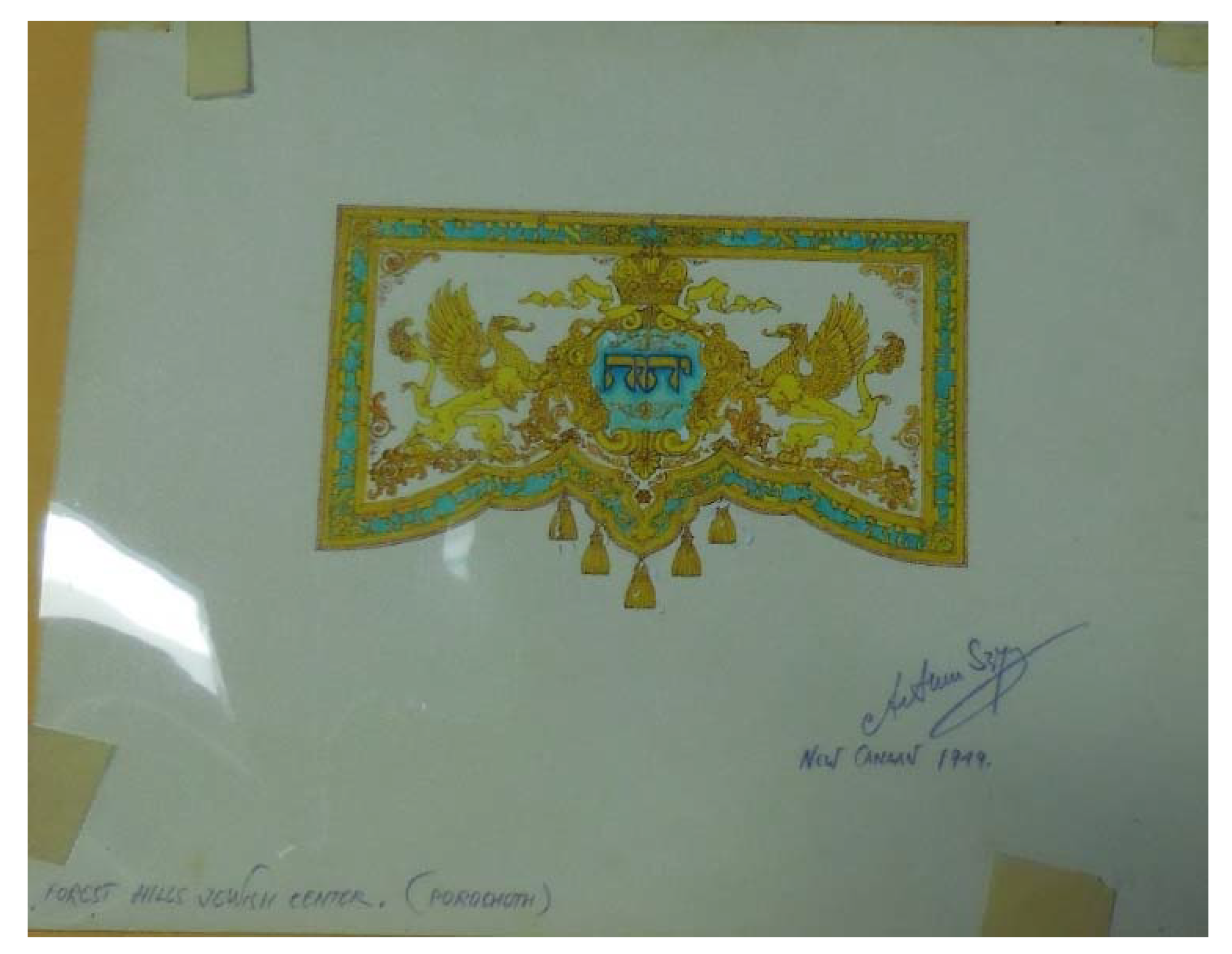

3. The Forest Hills Project

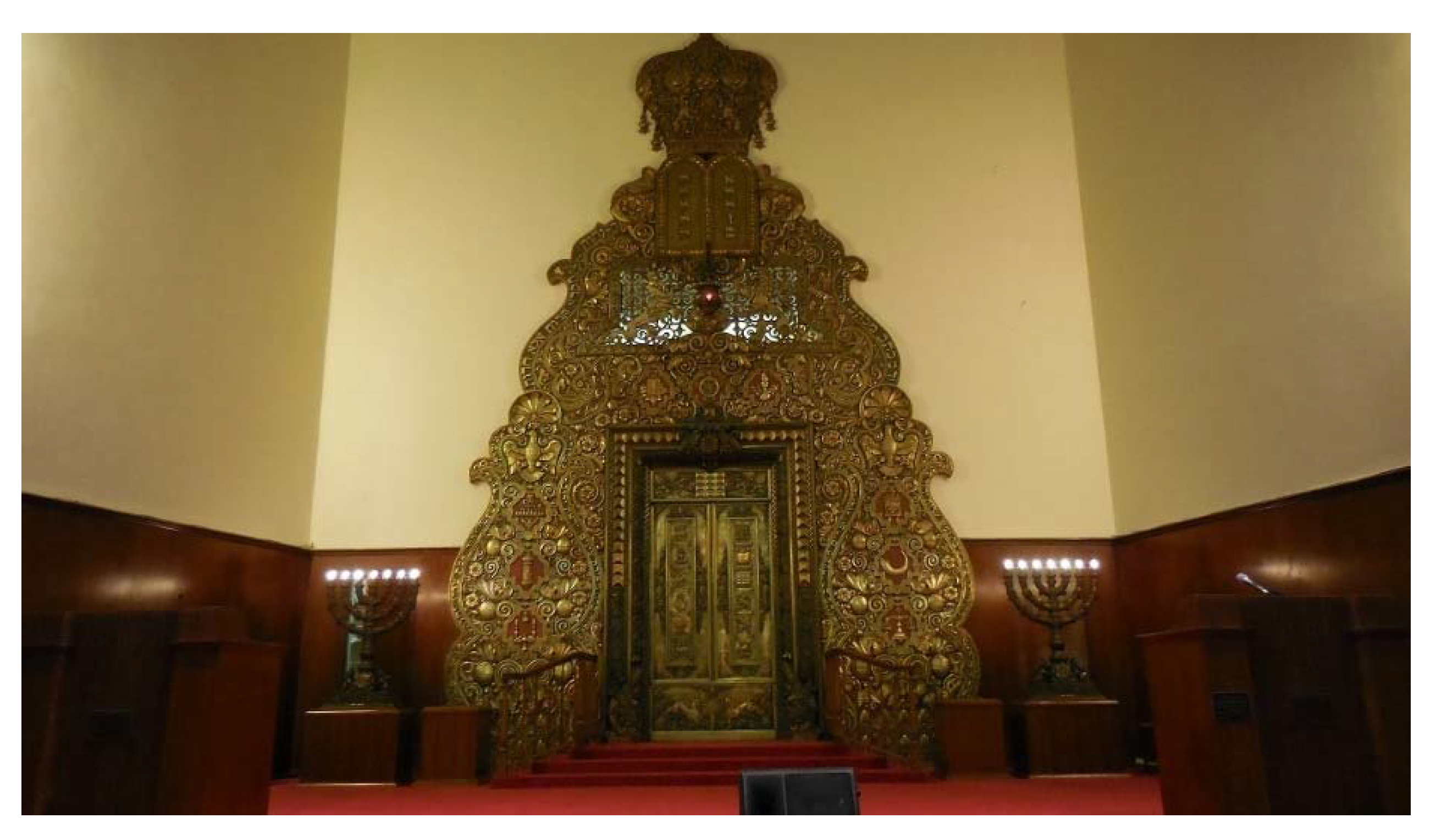

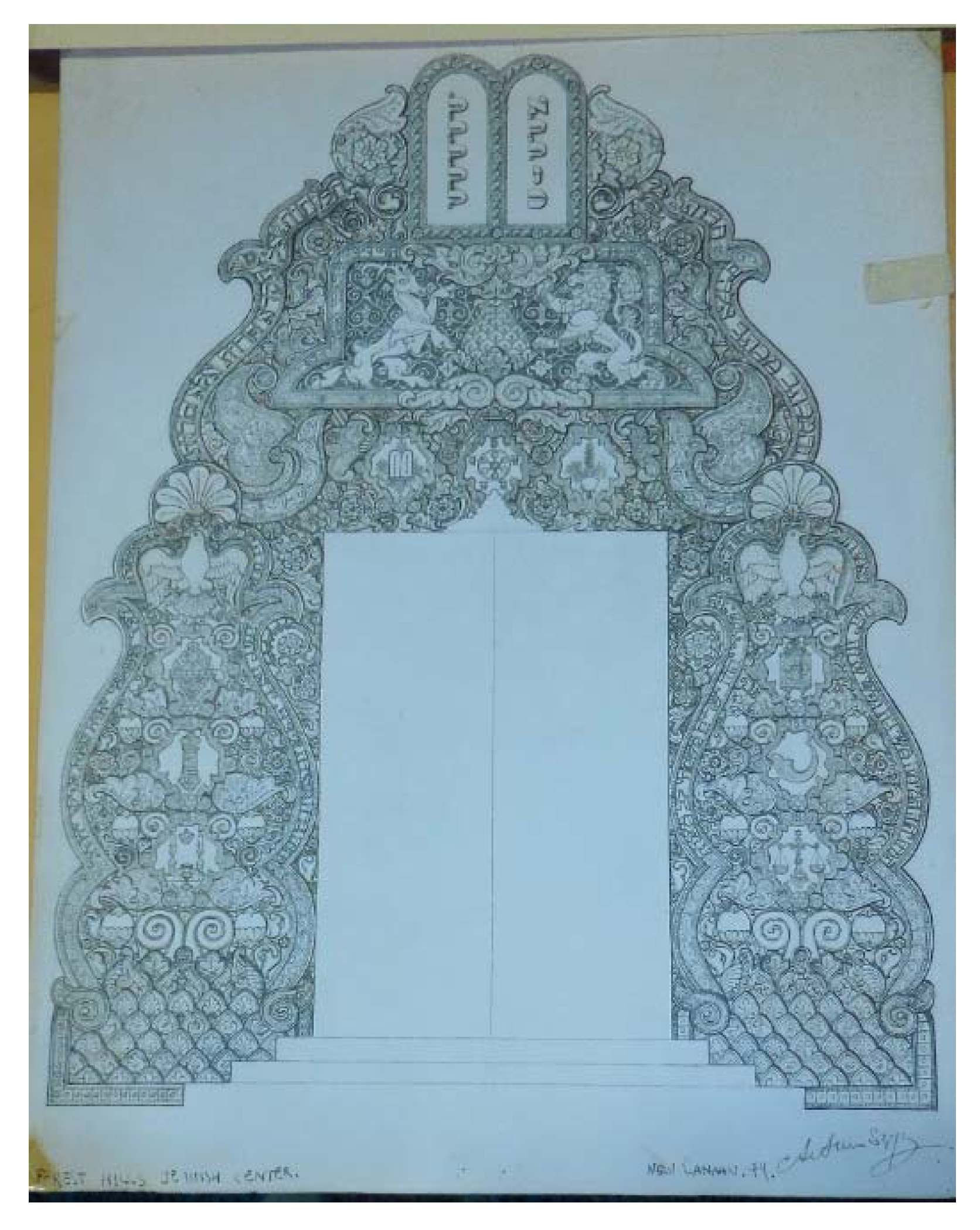

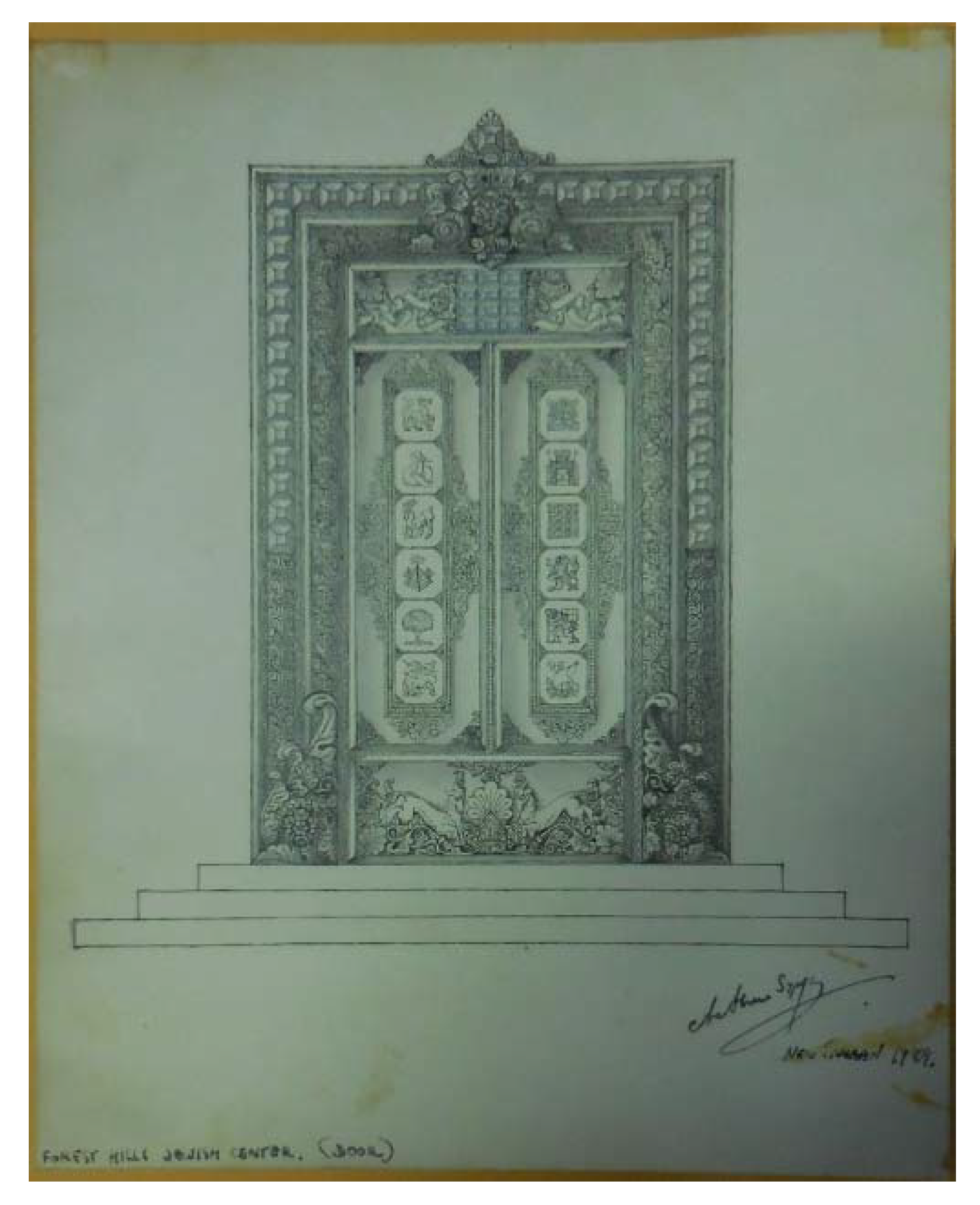

4. The Ark

תּוֹרַת ה’ תְּמִימָה מְשִׁיבַת נָפֶשׁ עֵדוּת יְהוָה נֶאֱמָנָה מַחְכִּימַת פֶּתִי. פִּקּוּדֵי ה’ יְשָׁרִים מְשַׂמְּחֵי לֵב מִצְוַת

The second half of verse 9 continues on the left side, followed by verse 10. These texts surround the following motifs (Figure 9b): a two-branched candlestick, with two challot and a kiddush goblet in front of them; the scroll case of a Megillah; and, above that, an oil lamp for Hanukkah. The text starts at the level of the candlesticks and works upward, around the bird atop the Hanukkah lamp, and curls down the outer left side of the ark.The law of the LORD is perfect, restoring the soul; the testimony of the LORD is sure, making wise the simple. The precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart…

ה’ בָּרָה מְאִירַת עֵינָיִם. יִרְאַת ה’ טְהוֹרָה עוֹמֶדֶת לָעַד מִשְׁפְּטֵי ה’ אֱמֶת צָדְקוּ יַחְדָּו

[T]he commandment of the LORD is pure, enlightening the eyes. The fear of the LORD is clean, enduring forever; the ordinances of the LORD are true, they are righteous altogether.(Psalms 19, pp. 9–10)16

The verse then continues down the left side:וְהַלֻּחֹת מַעֲשֵׂה אֱלֹהִים הֵמָּה וְהַמִּכְתָּב מִכְתַּב אֱלֹהִים הוּא חָרוּת עַל

הַלֻּחֹת, אַל תִּקְרָא חָרוּת אֶלָּא חֵרוּת

5. The Iconography of the Ark

הוי …, רץ כצבי, וגבור כארי לעשות רצון אביך שבשמים

[Judah ben (son of) Taima said] be [bold as a leopard, light as an eagle], swift as a deer, and strong as a lion to do the will of your Father in Heaven.

6. The Unique Iconography of Szyk

- Reuven is depicted as a flowering plant (Midrash on Numbers);

- Simeon as the gate of Shechem (Midrash on Numbers);

- Levi—by the Priestly Breastplate (in Hebrew, Hoshen) (Exodus 28:15–21);

- Judah by a Rampant Lion (Genesis 49:9);

- Issachar by man in ancient garb, hunched over with basket on back (Genesis 49:15);37

- Zebulun by a Ship (Genesis 49:13).

- Benjamin—wolf (Genesis 49:27);38

- Dan, a snake (Genesis 49:17);

- Naftali a hind (Genesis 49:21).

וְאֵלֶּה, שְׁמוֹת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, הַבָּאִים, מִצְרָיְמָה… רְאוּבֵן שִׁמְעוֹן, לֵוִי וִיהוּדָה. יִשָּׂשכָר זְבוּלֻן, וּבִנְיָמִן דָּן וְנַפְתָּלִי, גָּד וְאָשֵׁר

So Moses and Aaron came before Pharaoh and did just as the LORD had commanded: Aaron cast down his rod in the presence of Pharaoh and his courtiers, and it turned into a serpent.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ansell, Joseph. 2004. Arthur Szyk, Artist, Jew, Pole. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Philip S. 1945. Jewish Chaplains in World War II. American Jewish Yearbook 47: 180. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Francis, Samuel Rolles Driver, and Charles Augustus Briggs. 1951. A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmin, Itzhak, ed. 1955. World Jewish Register. New York: Monde, pp. 631–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mortimer J. 1946. Pathways Through the Bible. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mortimer J. 1946/1947. Szyk—Illustrator of Jewish Books. Jewish Book Annual V: 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Evelyn L. 1993/1994. The Tabernacle in the Wilderness: The “Mishkan” theme in Percival Goodman’s modern American synagogues. Jewish Art 19/20 (1993–1994): 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenheim, Tom. 2017. Arthur Szyk: Immigrant as Quintessential American Patriot. In Arthur Szyk, Soldier in Art. Edited by Irvin Ungar. London: Giles, pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Samuel D. 2003. American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Hetman, Yakov. 1977. The Great Synagogue. In Libovner. New York: Ktav, pp. 145–48. [Google Scholar]

- Israelowitz, Oscar. 1992. Synagogues of the United States. Brooklyn: Israelowitz Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kabakoff, Jacob. 2003. E.M. Lilien as interpreter of Morris Rosenfeld’s Ghetto Poems. Yiddish 13: 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kampf, Avram. 1966. Contemporary Synagogue Art. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Kandelshteyn, Shimon. 1977. Candid Snapshots of our Town. In Libovner. New York: Ktav, p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, Stephen. 1951. The Synagogue Interior Today. Conservative Judaism VII: 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, Isaac, ed. 1948. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Universal Jewish Encyclopedia Co., vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Libovner Voliner Benevolent Society. 1977. Luboml, the Memorial Book of a Vanished Shtetl. New York: Ktav. [Google Scholar]

- Luckert, Steven. The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk. Washington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Mendelsohn, Ezra. 2010. Arthur Szyk. Artist, Jew, Pole. European Journal of Jewish Studies 4: 324–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishori, Alec. 2019. The Twelve Tribes of Israel: From Biblical Symbolism to Emblems of a Mythical Promised Land. In Secularizing the Sacred Aspects of Israeli Visual Culture. Brill’s Series in Jewish Studies; Leiden: Brill, vol. 65, pp. 209–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nashman Fraiman, Susan. 2006. Joy and Gladness, Happy Festivals for the House of Judah: A unique parochet from Alessandria Della Paglia. Ars Judaica; the Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art 2: 151–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, Jacob. 2001. Dear Friends A Prophetic Journey through Great Events of the 20th Century. Hoboken: Ktav. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, Morris. 1902. Lieder des Ghetto. Translated by Berthold Feiwel. Berlin: Seeman. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Cecil. 1969. A Bibliographical Note on the Szyk Haggadah. Studies in Bibliography and Booklore IX: 50. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 1987. The Beginnings and Flourishing of “Ketubbah” Illustrations in Italy. Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 1998. Messianic aspirations and Renaissance urban ideals: The image of Jerusalem in the Venice Haggadah, 1609. In The Real and Ideal Jerusalem in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Art; Studies in Honor of Bezalel Narkiss on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. Special issue of the Journal of Jewish Art, 23/24, 295–321. Edited by Bianca Kühnel. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, Center for Jewish Art. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2003. The harmony of the cosmos: The image of the ideal Jewish world according to Venetian "kettubah" illuminators. In I beni Culturali Ebraici in Italia; Situazione Attuale, Problemi, Prospettive e Progetti per il Futuro. Edited by Mauro Perani. Ravenna: Longo Editore, pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2008a. The Historical and Artistic Context of the Szyk Haggadah. In Freedom Illuminated: Understanding The Szyk Haggadah. Edited by Byron L. Sherwin and Irvin Ungar. Burlingame: Historicana, pp. 33–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2008b. Between Calvinists and Jews: Hebrew script in Rembrandt’s art. In Beyond the Yellow Badge; Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture. Edited by Mitchell B. Merback. Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–404. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfatti, Gad Ben Ami. 1990. The Tablets of the Law as a Symbol of Judaism. In The Ten Commandments in History and Tradition. Edited by Ben-Zion Segal and Gershon Levi. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, pp. 383–418. [Google Scholar]

- Schack, William. 1956. Modern Art in the Synagogue II. Commentary 21: 152–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin, Byron L, and Irvin Ungar, eds. 2008. Freedom Illuminated: Understanding The Szyk Haggadah. Burlingame: Historicana. [Google Scholar]

- Shinan, Avigdor. 2015. Sefer Ha’Aggada. Compiled by CH.N. Bialik & Y.Ch. Ravnitzky. Edited with a New Commentary by Avigdor Shinan. Or Yehuda: Dvir. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Judah Slotki, trans. 1939, Midrash Rabba Numbers I. London: Soncino.

- Szyk, Arthur. 2011. The Haggadah. Translation and Commentary by Byron L. Sherwin with Irvin Ungar. New York: Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, Irvin. 2008. Telling the Story: A History of the Szyk Haggada. In Freedom Illuminated: Understanding The Szyk Haggadah. Edited by Byron L. Sherwin and Irvin Ungar. Burlingame: Historicana, pp. 121–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, Irvin, ed. 2017a. Arthur Szyk—Soldier in Art. Burlingame: Historicana. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, Irvin. 2017b. Behind the Great Art and the Great Messages Stands Arthur Szyk, the Great Man. In Arthur Szyk—Soldier in Art. Edited by Irvin Ungar. Burlingame: Historicana, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- The Jewish Biographical Bureau. 1980. Who’s Who in American Jewry. Los Angeles: Standard. [Google Scholar]

- Wischnitzer, Rachel. 1955. Synagogue architecture in the United States. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, Bracha. 2006. Praising the Lord: Discovering a Song of Ascents on Carved Torah Arks in Eastern Europe. Ars Judaica 2: 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, Bracha. 2017. The Carved Wooden Torah Arks of Eastern Europe. Oxford: Littman. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See (Ansell 2004) and a scholarly reevaluation of his famous Haggadah, (Sherwin and Ungar 2008). |

| 2 | To mention a few in the last twenty years: Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom at the Library of Congress, 9 December 1999–6 May 2000. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/szyk/, accessed on 8 December 2019; The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 10 April 2002–14 October 2002; https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/szyk/, accessed on 8 December 2019; and the exhibit at the New York Historical Society, 15 September 2017–21 January 2018; https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/arthur-szyk-soldier-art, accessed on 8 December 2019. |

| 3 | The Haggadah was published in 1940 in England (Roth 1969, p. 50). According to the Jewish Theological Seminary announcement (Alfred Werner collection, M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives University at Albany, SUNY archive), some 240 copies were printed, of which 115 were in the United States. The Haggadah was printed multiple times in both Israel and the United States. A recent facsimile was reissued, with translation and commentary by Byron L. Sherwin with Irvin Ungar, in 2011 (Szyk 2011). |

| 4 | They lived in London from 1937 until 1940 (Ansell 2004, pp. 117–19). |

| 5 | Cover of The American Hebrew “For Better Understanding between Christians and Jews”, 16 January 1942. |

| 6 | The Haggadah was put on display at the Jewish Theological Seminary in the spring of 1942, as mentioned in the Flatbush Jewish Center Bulletin of the same year, undated (Alfred Werner collection, M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives University at Albany, SUNY archive). This exhibit does not appear in the list that appears at the end of (Ungar 2017a). |

| 7 | Irvin Ungar in discussion, December 2018. Jaffe was an art printer who lived in Forest Hills, so it is not surprising that he would have known Szyk. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/05/08/archives/herman-jaffe-77-printed-art-stamps.html, accessed on 22 December 2019; in this obituary, it is mentioned that he printed stamps for Liberia, and Szyk seems to have designed them (Ungar 2017a, p. 215, plate 176). |

| 8 | The Temple was converted into an arts center in 2010, since the community has a new home. https://www.clevelandjewishnews.com/archives/the-temple-unlocks-key-to-the-past/article_5d9fc945-9f21-5a76-854b-a5af426a89ed.html, accessed on 6 December 2019. |

| 9 | Forest Hills Home News, March 1945, vol. 1, no. 4, 2, JTA, Bokser archives box 15/3. |

| 10 | Correspondence Ben Zion Bokser Rabbinical Papers, The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY, ARC.1000.026, (Box 15) (Bernstein 1945, p. 180); Bokser was inducted in 1944 and released in 1946. All of his service was stateside. |

| 11 | Mentioned briefly by Wischnitzer (1955, p. 165). The synagogue, designed on “very plain lines”, dispensed with the flexible plan which was coming into its own at that time, and “[i]t was felt, before long, however, that the prayer hall needed spiritual content, color, emotional stimulation”. |

| 12 | “New Forest Hills Synagogue and Jewish Center Is Opened: Dedicatory Service in New Synagogue in Forest Hills”, New York Herald Tribune (1926–1962), 19 September 1949, p. 17. |

| 13 | 30 feet tall, according to Israelowitz (1992, p. 129). |

| 14 | The Forest Hills Jewish Center 1931–1981, 1981, unpaged, in the collection of the synagogue. |

| 15 | From an explication of the ark in Bokser’s papers at the Jewish Theological Seminary, “An Interpretation of Our Ark,” Ben Zion Bokser Rabbinical Papers, The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY, ARC.1000.026, (Box 17, Folder 5). |

| 16 | The texts are not vocalized, with the important exception of two words, as we shall see later. |

| 17 | This element also appears in the Haggadah. See (Sabar 2008a, pp. 54–55). |

| 18 | The vowels appear on the verse on the ark to make the distinction—there is no vocalization in the other Hebrew verses on the ark. |

| 19 | The motif of the crown is discussed by Yaniv (2017, pp. 104–11), and on arks 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 11, in her appendix I; all four animals mentioned in Ethics of the Fathers 5:20 appear on the Torah ark from Kepno, 1816–1817 (Yaniv 2017, p. 262; Yaniv 2006, p. 85, note 5). They appear on a 17th century ark from Krakow in the collection of the Heichal Shlomo Museum. http://kng58.org.il/sliding-doors/, accessed on 16 December 2019. |

| 20 | Known in the Polish and Yiddish literature as the “Lemberg” Haggadah because it was originally to be dedicated to a group of Jews in Lvov who were sponsors of Szyk (Sabar 2008a, p. 54). He even made a contract with the community of Lvov to publish the Haggadah, see (Ungar 2008, pp. 190, 198–99). |

| 21 | Forty of the drawings are dated 1935. All of the watercolor and gouache paintings were done by Szyk on paper (Ungar 2008, p. 209). |

| 22 | The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, ID 169143-169144. |

| 23 | Griffins holding the crown are on the ark from Druya (Yaniv 2017, pp. 117–18); they appear as substitutes for the cherubim on the ark of Yarishiv (ibid., pp. 166–67); Yaniv concludes that “the griffin, an imaginary creature which combines a lion’s body with an eagle’s head and wings was a suitable replacement [for the cherubim]” (ibid., p. 169). |

| 24 | For a complete discussion, see (Sabar 2008a, pp. 33–170). |

| 25 | Also reproduced in (Ungar 2017a, p. 58, fig. 25). |

| 26 | Reproduced in (Sabar 2008a, p. 61). |

| 27 | For one such example, see (Nashman Fraiman 2006). |

| 28 | The Forest Hills Jewish Center 1931–1981, unpaged. |

| 29 | From an explication of the ark in Bokser’s papers at the Jewish Theological Seminary, “An Interpretation of Our Ark,” Ben Zion Bokser Rabbinical Papers, The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY, ARC.1000.026, (Box 17, Folder 5). |

| 30 | Szyk has more naturalistic doves also in his dedication to King George VI. See (Sabar 2008a, p. 57). |

| 31 | Although listed as being copyrighted in 1948, it seems that some of the entries were only updated to 1943; so, for instance, the Warsaw Ghetto uprising is not mentioned in the entry for Warsaw, nor is the end of World War II. |

| 32 | For a full list of articles that discuss the Ten Commandments, in both Jewish and Christian art, see (Sabar 2008b, p. 394, note 70). Sabar discusses the Ten Commandments in the synagogue of Amsterdam and in the work of Rembrandt on pages 393–402. |

| 33 | It is important to note that the use and diffusion of the symbolism of the twelve tribes appears already on Italian Ketubbot of the 17th century, as well as on the walls of painted European synagogues in the 19th century. For a discussion of the imagery of the tribes, see (Sabar 1987, pp. 181–92; Sabar 1998, pp. 308–10) and notes there. According to Sabar (2003, p. 204), the earliest extant depiction of the twelve tribes in a Jewish context has survived on an illuminated marriage contract from Verona, dated to 1695. |

| 34 | The doors of the “Little Synagogue” ark are carved from wood, The Forest Hills Jewish Center 1931–1981, unpaged. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | For the Hebrew, see (Shinan 2015, p. 101); for English, see (Slotki 1939, p. 30). |

| 37 | Sabar (2008a, p. 152, note 109) suggested that Szyk changed the traditional symbolism of Issachar as a donkey, to suit the message of the Haggadah, but the description is in fact based on the literal meaning of the verse (“For he saw a resting-place that it was good, and the land that it was pleasant; and he bowed his shoulder to bear, and became a servant under task-work”) and already appears in earlier works of Szyk’s (). See also note 46, below. |

| 38 | Benjamin’s symbol looks like a horse, but it may have been a technical problem of a misinterpretation of the drawing by Szyk. |

| 39 | Sources for some of this imagery can also be found in Szyk’s other works. The exact same tribal imagery appears in an early work for a Haggadah depicting the Pharaoh’s maid saving the baby Moses from the Nile (Ungar 2008, p. 178, fig 50), as well in later works, such as in in the plate Israel, from the Visual History of the Nations, published in 1948. |

| 40 | I am grateful to Sergey Kravtsov for pointing this out to me. |

| 41 | Lilien’s depiction of the tribes may predate this version, as seen in his design for the cover of the Jewish National Fund Golden Book, ca. 1902 (Mishory 2019, p. 225). Lilien was consistent in his depictions, but Mishory does not analyze specific motifs. This article is the most recent treatment of the tribes in Israeli art. |

| 42 | The frame was reused again, later in the book, for other poems (Sephirah, pp. 78–79 and Das Wunderschiff, pp. 128–129), with no relationship to the content. |

| 43 | Unsigned article, “Rosenfeld’s Poetry in German Form, illustrated by Lilien”, in the American Hebrew, vol. LXXII, no. 16, 6 March 1903, pp. 530–31, cited by Kabakoff (2003, p. 70). |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 46 | Mentioned by Sabar (2008a, pp. 78–79) and stated by Irvin Ungar at his lecture “Freedom Illuminated—Understanding the Szyk Haggadah”, at the National Library in Jerusalem, 8 November 2018. |

| 47 | Reproduced in (Ungar 2017a, p. 215, fig 175), issued 31 August 1950. |

| 48 | On the right door are labeled medallions for Reuven, Simeon, and Levi, together with Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, and Dan. On the left door are symbols for Naftali, Gad, Asher, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Menasseh. Mentioned in Shinan editor, Parashat Veyechi, 12, 1/2001, unpaged in Nehardea, Sheets in the weekly Torah Portion of the Hebrew University (Nehardea, Dapei Parashat HaShavua shel HaUniversita Hivrit). |

| 49 | Szyk depicted the Polish eagle in his cycle on the Statute of Kalisz, published in 1928, https://www.polin.pl/en/event/the-statute-of-kalisz-the-750th-anniversary-of-the-first, accessed on 6 December 2019, and also in the Visual History of Nations Series (New Canaan, 1946), an ambitious project to depict sixty countries. Only nine were every completed. He depicted the American Eagle in 1945 as part of this same series. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/szyk/szyk-ex.html#obj2, accessed on 6 December 2019. |

| 50 | |

| 51 | Ben Zion Bokser Rabbinical Papers, The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY, ARC.1000.026, (Box 17, Folder 5). |

| 52 | Cited by (Ungar 2017b, pp. 25–26). |

| 53 | Neither at the synagogue nor in Bokser’s archive at the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary. Pressman does not have an archive at the Jewish Theological Seminary in NYC. Bokser was only decommissioned in April 1946. Pressman moved to Los Angeles in 1948, as an assistant rabbi at Temple Sinai and he served as the congregational rabbi of Temple Beth Am from 1950 until his retirement (Bnai Brith Messenger, 1 October 1948, p. 71; The Jewish Biographical Bureau 1980, p. 380). He was a prominent Jewish leader for the rest of his career, often speaking at political events. https://www.tbala.org/about/our-history, accessed on 16 December 2019. |

| 54 | The ark in use, up until the latest renovation, was modeled after the Torah case given to Harry Truman by Chaim Weizmann and designed by Ludwig Wolpert of the Bezalel School. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/2003-290, accessed on 16 December 2019. In 1966, a wall in memory of the Holocaust was created in the sanctuary at Pressman’s initiative. If anything, this may speak of the influence of Bokser on Pressman. https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-l-a-s-mostly-forgotten-holocaust-wall-1.5464671, accessed on 16 December 2019. |

| 55 | A short page of his memories, “Our Shtetl”, appears in the English translation of the Luboml Yizkor Book (Libovner Voliner Benevolent Society 1977, p. 114). |

| 56 | Other accounts mention depictions of the Holy Temple and the Zodiac (Hetman 1977, pp. 146–47; Kandelshteyn 1977, p. 160). |

| 57 | September 1945 issue of The Message, p. 1, Ben Zion Bokser Rabbinical Papers, The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, NY, ARC.1000.026, (Box 16, Folder 4). |

| 58 | The shape of this Torah Ark does not at all resemble the Torah ark depicted in Szyk’s Haggadah but is more similar to the frontispiece design of the Haggadah. In an album commemorating the 50th anniversary of the synagogue, The Forest Hills Jewish Center 1931–1981 (in the collection of the synagogue--unpaged), the shape was likened to a breastplate. However, it is more likely to be based loosely on the form of European wooden synagogue arks that are wide at the bottom and taper off at the top, often topped with a crown. See, for instance, the Torah Ark of Vyzuonos (Yaniv 2017, p. 235) and of Lukiv (ibid., p. 246). |

| 59 | Several more contemporary synagogues have tried to hearken back to the wooden synagogues of Eastern Europe, for instance, the Hampton Synagogue in Westhampton Beach, New York (Gruber 2003, pp. 201–02). |

| 60 | However, it was unlike many other synagogues being built at that time, such as the synagogues designed by Erich Mendelsohn and Percival Goodman. For more on Goodman, see (Cohen 1993/1994). Most, but not all of the 50 synagogues he was involved in belonged to the Reform Movement, which, not surprisingly, embraced the modernist visual idiom. At least two of Mendelsohn’s designs were for Conservative congregations, The Park Synagogue of Cleveland Heights and Bnai Amoona of St. Louis (now a center for the arts, https://www.cocastl.org/createourfuture/historic-mendelsohn-building/, accessed on 8 December 2019). |

| 61 | Kayser does not mention Szyk or the synagogue by name; he simply hints at them: “For example, at one of our new synagogues, after the rather modern structure was completed, an artist was commissioned to design an Aron Kodesh. The artist’s general inclination is toward renewal of certain picturesque features in Jewish pictorial at and whose thinking is much more in terms of minute details than in monumental structures” (Kayser 1951, p. 16); Schack (1956, p. 156) mentions Szyk by name. |

| 62 | Szyk became a United Stated citizen in 1948 (Ansell 2004, p. 227). |

| 63 | Szyk was to be investigated for activities alongside dignitaries such as Einstein. See (Freudenheim 2017, pp. 93–94). |

| 64 | https://patch.com/new-york/foresthills/forest-hills-jewish-centers-redevelopment-put-hold-report, accessed on 10 December 2019. |

| 65 | Conversation with the Center’s Executive Director, Deborah Gregor, April 2018. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nashman Fraiman, S. The Torah Ark of Arthur Szyk. Arts 2020, 9, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020060

Nashman Fraiman S. The Torah Ark of Arthur Szyk. Arts. 2020; 9(2):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020060

Chicago/Turabian StyleNashman Fraiman, Susan. 2020. "The Torah Ark of Arthur Szyk" Arts 9, no. 2: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020060

APA StyleNashman Fraiman, S. (2020). The Torah Ark of Arthur Szyk. Arts, 9(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020060