1. Introduction: Towards a Framework between the Physical and Digital and Back

Over the last ten years, I have developed an endurance running art practice as part of a larger inquiry into the performative nature of human physical activity, in the interplay between the body and technology. The runs I undertake are performed in specific places along pre-determined routes and are mediated to an audience live through mobile technology that is enabled to track my journey as it is taking place and to relay images of my viewpoint and location.

I align this work to performance art practices in the ways in which the limits of my body are tested through the physical demands of long-distance running, whilst the limits of technology are also challenged through the ways in which I communicate that experience to others. In doing this, I do not attempt to demonstrate the reliability (or not) of technology to convey a first-hand, ‘lived’ experience, but point to the increasing presence of technology in our everyday environment: to the proliferation of technology as a primary means of communication and of mediating experience; to the ‘need’ to always be connected; to the fallibility of the human body and of technology. Rather than make claims to a ‘loss’ in visceral experience, I look to how different technological formats might constitute new ways of thinking about the experience of place and of creating new mediated spaces. At the same time, I also consider how the nature of our engagement with technology also grounds us in our own physicality by drawing attention to questions of presence and embodiment in the ontological dynamics between recording and representation.

This is closely linked to relationships between live performance and its documentation, a subject that has long dogged the histories of performance art practices and which, for some, continues to be a bone of contention as to what constitutes the true nature of an ‘original’ performance and our understanding of it. I have previously stated with reference to the work of

Peggy Phelan (

1993),

Amelia Jones (

1997), and

Philip Auslander (

2006,

2008,

2018) that the increasing inclusion of technology and its mechanisms into and as live performance has complicated this relationship in that ‘what initially appeared to separate what is live and what is recorded in the experience of a performance by an audience as it is taking place and the experience of a performance after it has occurred [via its documentation], has become increasingly blurred’ (

Chance 2017, p. 270).

This has led me to reconsider the status of performance (and of the document) by suggesting new insights into the nature of liveness through documentation, in the live recording and representation of the runs I undertake. In doing so, I expand on previous observations regarding the nature of presence in live performance (which suggests the need for an audience to be physically present in the same space and place as the performance), by attributing the notion of presence to the real-time recording and representation of documentation. Here, the status of the document becomes intertwined through its immediate creation within the live ‘action’ of the run as a performance, where there is no direct audience present, and its live dissemination as a moving image sequence of still photographic images (of my viewpoint and location) to an audience located elsewhere. Both occur simultaneously. This questions the space and place in which the performance occurs. Moreover, the document, traditionally considered secondary to an ‘original’ live performance because it ‘cannot convey the total event and the audience’s engagement with it’ (

Auslander 2018, p. 42) as part of the live action of the performance, now has equal status with it.

The status of the document is further challenged in subsequent representations of the work in archive form, that can, in the first instance, be reshown from an Internet database through the replay of the original sequence of images and GPS tracking embedded within an online interface, subsequent to the ‘original’ live run event. There is very little difference to an audience experiencing this, with regard to the manner in which the work was originally experienced as documentation (through a sequence of live-streamed images during the run), versus how it is experienced as a sequence of recorded, replayed images after the run that are reactivated to re-perform the journey originally undertaken.

In the second instance, the printing of the images into a physical document/artist’s book work allows a further consideration of the image and of the document to take place in its transformation from a digital to a physical, tangible format and for status of the image to be reconsidered and re-presented through its status as a physical document and artwork. In this case, the (re)production of the images are not foregrounded as part of the live action of the event (the original run) nor through their physical output in the process of printing but through the physicality of the image as a printed document and record of a journey undertaken, and through what the images and the document themselves depict and represent. Specifically, the hybrid status of the document as a sculptural artwork and artist’s book enables a further interrogation of the form and concept of the latter as embodying ‘a diverse set of artistic practices’ and ‘span[ning] vast artistic territories’ (

Burkhart 2006, p. 248). Its “Mongrel Nature” (

Phillpot 1998, via

Burkhart 2006, p. 249), perfectly attune to work against a singular definition, sits ‘at the juncture where art, documentation and literature all come together’ (ibid.).

The Great Orbital Run was a live performance and artwork initiated within this framework. What was significant about this work was not only how it shaped a particular methodology and the development of subsequent artworks, but how a further iteration of the work as the

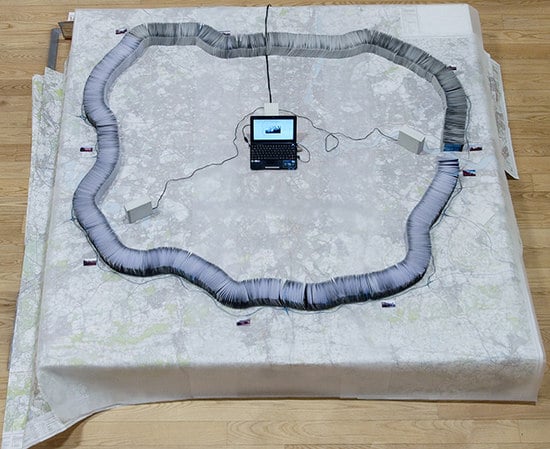

M25 in 4000 Images, as seen in

Figure 1, further interrogates the status of the image, the document, and the artist’s book through its reconfiguration as a physical outcome, artwork, and archive, making what had been relayed digitally, tangible. In its digital format, each image was visible only as a single instance that made each individual image (or page) briefly visible through a sequential passage of time; as a physical output, all of the approximately 4000 images representing the run can be seen in their entirety at the same time, as part of an extendable, concertina book work/sculpture. However, embedded as they are into the ‘folds’ of the ‘book’, the images are only visible as small glimpses of the landscape and viewpoint they depict. In addition, they are not of the run itself, but images taken of the artist’s viewpoint whilst running. A hybrid object that is singularly neither document nor archive nor book nor sculpture, but all of these, the work exceeds the limits and status of each of these individual formats. A separate sound file is the only reminder of the original activity. The inclusion of a map as part of the work is further indication of its location, but the work is not wholly dependent on its inclusion; it has been shown both with and without it.

This essay examines relationships between the original artwork as a performance and its status as documentation, linking to perceived previous binary divisions between the two, firstly from the perspective of the context of performance and performance documentation, then from a more direct consideration of the document as an artist’s book, document, and artwork in its own right. Rather than assign the status of documentation and of the book as ‘secondary’ to the ‘original’ running event, the document is considered through its performative potential, which is further extended to consider the documentary properties of the artist’s book. As well as a discussion on the form and concept of the book and what constitutes an artist’s book (

Drucker 2004), I will refer to the spatial and temporal nature of the book as a particular kind of document, expanding upon previous relationships I have made between documentation and performance. This is extended to the consideration of the book as a ‘form of three-dimensional representation’, drawing specifically on Marian Macken’s 2016 essay on artists’ books and documentation in which she asserts agency to the artist’s book through ‘the strategy of aligning books with spatial practice’ (p. 13).

The next section begins as a narrative account of the original M25 run

1 told in the first person from the perspective of the artist as a means of first considering the relationship between the work as a performance and its status as documentation through the making of the original artwork.

2 This is then reconsidered through its archival replay as a digital document and then through the representation of the work as The M25 in 4000 Images. A discussion of the relationship between artwork and art documentation in performance follows as a means of developing the theoretical context before its further reconsideration in relation to the artist’s book.

2. From The Great Orbital Run to the Making of The M25 in 4000 Images

At approximately 10 a.m. on Monday, 5 March 2012, I set off alone on foot from the Premier Inn, Thurrock, at Junction 31 of the M25 London Orbital, just north of the River Thames. It was the first day and first stage of a planned nine-day journey, the objective of which was to make my way around the inside boundary of the London Orbital, not walking, but running.

Moving anti-clockwise, I began my journey following the direction and sound of traffic, keeping as close to the edge of the boundary as I could. I was dressed from head to foot in light but durable clothing that would not only protect me from all weathers but would also enable me to move through the variations in landscape and terrain that I would encounter en route. I knew that, as well as running on undefined territory, I would have to climb, jump, and squeeze myself through different spaces to make my own path. A small rucksack on my back held just enough for one change of clothing, a small notebook computer, spare batteries and chargers, a flask of high glucose fluid, some powder sachets, and some energy bars, enough to last me the nine days of the journey. Strapped to my head and body were a number of media devices that were not only recording the activity as I ran, but were also sending data approximately every 30 s to an Internet database in the form of a photographic image and GPS coordinates.

Both images and GPS location were accessible through a web interface that was simultaneously being projected onto a pre-installed, pieced-together 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map and tracing of the route, which was installed on a wall of the Stephen Lawrence Gallery at the University of Greenwich (the location of the exhibition of which this work was a part). These elements enabled visitors to not only track my progress in real time as I ran (through the projection of a moving black line indicating my position on the route), but to also glimpse my viewpoint and location through a continuous sequence of pulsing images that were being streamed from my mobile phone to the projected interface.

The sound of my breath and running footfall could be heard through speakers installed at each side of the map, indicating both the running activity and its location. As long as the technology did not break down, this would continue to show my progress until I completed the run. This work was therefore not only a test of my physical and mental capacities in performing and completing the task of the run, away from an audience that I could not see, but also of the technology I was using in relaying the activity at the same time to another space and audience located some distance away. With no other direct means of communication, I had to trust that the technology was performing its task. The audience, presuming there was one, had to trust that what it was seeing in the gallery was really taking place at the same time in another location. This pattern would continue for the nine days of the run. Although I was not physically present in the gallery space, my presence was being activated through the live mediation of images and the slow delineation of a route being marked out on a map as I ran.

Once I had completed the run, an ‘archived’ version of the images and GPS tracking replayed the whole journey as a moving-image projection from its Internet storage place in real time until the end of the exhibition. Two glass cabinets were added to the left of the large map, displaying items of clothing and other ephemera as relics from the recent running activity and as ‘proof’ that it had taken place. The sound of my breath and footfall could still be heard through speakers installed at each side of the map, indicating both the running activity and its location. Although I was not physically present in the gallery space, my presence was still being activated through the live mediation of images and the slow delineation of a route being marked out on a map as I ran (

Figure 2).

It took two years to conceive of and develop the

M25 in 4000 Images (2014) a unique, digitally printed, hand-cut and folded, extendible and unbound concertina artist’s bookwork/sculpture, made as a physical reiteration of the above work from the nearly 4000 images that had been live-streamed as part of it. These ‘pages’, previously relayed digitally as fleeting glimpses of the viewable landscape lying ahead of me and that disappeared with the appearance of the next image, were now connected together in sequence as a physical entity and as a means of reconfiguring and making present the journey in its entirety. As an artwork, it was also an attempt to make sense of our current engagement with the image and with the pictorial representation of the world around us, in the dynamics between the digital and physical. No longer a ‘live’ presentation nor a digital replay of a live event, the quest was in how these archived images and their representation as a document in physical form could be a distinct means of representing the journey and the landscape they embodied. During the run, I had not been able to ‘see’ any of the images that had been live-streamed each day, but I was very aware of the quantity of images that were being temporarily stored as data to a folder on my mobile phone. To make room for the next day’s images, I had to move these images to another folder or I could have deleted them. However, it was their ephemerality that made me want to keep them, firstly as a back-up should the live-streaming not work and, secondly, as a personal pictorial record and archive of the journey that could have future potential as an additional artwork. This was not to be a replacement for the previous work, nor was it to be considered secondary to the original ‘live’ running event, but an opportunity to further examine the performativity of the document itself (

Jones 1997;

Auslander 2006), as a tangible ‘holder of experience’ (

Macken 2016, p. 13). This would not be a journey I would be repeating so the images were a palpable reminder of the journey I had undertaken.

In the immediate, I could not contemplate how I might use this sheer mass of images, the quantity of which, even when separated into folders representing each day, averaged approximately 445 images. It was too overwhelming to even begin to make sense of these, let alone begin to think of their repurposing into something like a book, yet this seemed to be the most logical format to represent this nine-day journey. At the same time, I knew this would not be a book in the conventional sense. I was well aware of ‘iconic’ books by artists using photography that were representative of particular routes, journeys, or places, such as Ed Ruscha’s

Twenty Six Gasoline Stations (1963), a publication ‘consisting of twenty-six black and white documentary photographs of petrol stations along the highway between the artist’s home in Los Angeles and his parents’ house in Oklahoma City’,

3 and

Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1967), a twenty-five-foot-long folded ‘concertina’ book of two continuous simultaneous photographic views representing each side of a mile and a half stretch of Los Angeles’ famous Sunset Boulevard,

4 or, more recently, Brazilian artist Leticia Lampert’s

Conhecidos de Vista (Known by Sight) (2018)

, a double-sided, concertina-folded book-work representing apartment buildings in the urban neighbourhood of Porto Alegre in which she grew up.

5 I also knew of books made by artists such as Richard Long, Hamish Fulton, Helen Douglas, and, recently, Stuart Mugridge, who are ‘part of the tradition of artists inspired by nature, landscape and [the physical act of] walking.’

6 None of these examples are considered conventional, but all use significantly fewer pages and somehow seem in the ways in which they are constructed, presented or ‘packaged’, still to be somewhat contained or finite.

About ten years earlier I had also been struck by the artist Susan Hiller’s

J. Street Project (2002–2005), a moving image artwork that consisted of a sequence of still photographic images of street signs in Germany that incorporated ‘Jude’, the German word for Jew. These ‘mundane’ signs from ‘city centres, villages, suburban and rural settings’ had been found in ‘streets, lanes, avenues and alleys scattered throughout the country.’ Although this work was primarily concerned with evoking the ‘memory of Jewish presence in the locations’, and with that the ‘tension between past and present’, as a means of highlighting ‘the sense of absence and traumatic loss’,

7 it was the banality of these images and Hiller’s approach in her employment of a ‘neutral seriality’ that was particularly powerful in emphasising the fact that the most ordinary of images are themselves rarely neutral. In the case of the M25 London Orbital, it was its status as a boundary or ‘perimeter fence’ surrounding Greater London and its outer suburbs that marked it: ‘Encircling London like a noose, the M25 is a road to nowhere.’

8 As the writer Iain Sinclair succinctly puts it:

The dull silvertop that acts as a prophylactic between driver and landscape. Was this grim necklace, opened by Margaret Thatcher on the 29 October 1986, the true perimeter fence? Did this conceptual ha-ha mark the boundary of whatever could be called London? Or was it a tourniquet, sponsored by the Ministry of Transport and the Highways Agency, to choke the living breath from the metropolis?

Like Sinclair I had been determined to find out where my journey would lead me, keeping within the ‘

acoustic [and visual]

footprints’ of this road, around which there is no existing pedestrian path. Unlike him, my quest had not been to stop and visit the ‘converted asylums, industrial and retail parks, ring-fenced government institutions and lost villages’.

9 I stumbled upon, but to keep moving through them, negotiating my own route and to keep streaming images of the viewpoint ahead of me until I reached my next pre-booked motel stop for the night.

Hiller’s work also incorporated a soundtrack recording, including ‘traffic noise, church bells and other incidental sounds,’ and was part of a larger project that included a photographic installation and book identifying each of the signs. Importantly, no one element of the project was considered more significant than the other. Likewise,

The M25 in 4000 Images is one component of a bigger project that includes the original run, a photographic and mixed media web interface and map installation, a pre-recorded soundtrack recording identifying the run and other incidental sounds marking its location, and the ‘book’ incorporating every photograph taken and live-streamed during the run. The latter’s status as another iteration of the earlier work enables another means of considering both the journey and the landscape it represents, its unboundedness marking it as both unwieldly and able to be contained at the same time, but not fixed to a particular format or means of presentation. This was as much a practical decision as one that seemed particularly fitting, as was the re-orientation of the large constructed map and drawing from the original exhibition onto which the images ‘sit’, from vertical to horizontal, reflecting the way in which we often engage with large maps, in the book’s first outing as part of a new installation, as seen in

Figure 1. More sculpture than book, its concertina format enables its pages to be squeezed together to fit around the inside contours of the M25 boundary that is traced out on the drawing superimposed on the map, its circularity also indicating an endlessness that is only split by a small gap marking the beginning and end of the route at each end of the River Thames at the Queen Elizabeth Bridge, the only part of the route that cannot be crossed as a pedestrian (

Figure 3).

The installation also includes the real-time ‘archived’ replay of the original streamed images and GPS tracking line from its web interface, this time displayed on a small notebook computer, complete with soundtrack and positioned strategically in the centre of the map at the heart of the city of London. The juxtaposition of both kinds of image in both digital and physical format enable the viewer, on the one hand, to see the entirety of the book as representative of the whole of the journey undertaken, positioned within its topographical location; on the other hand, the digital replay allows a ‘page by page’ view of what lies within the folds of the book, reflecting the original activity as both a physical act and an act of technological mediation. Both deny the viewer the possibility of easily seeing all of the images contained within the book unless they are prepared to take the time to physically prize open each of its pages as a physical book or to sit through the several hours or days that the digital sequence of its pages would take to replay. If this work is intended as a reflection on our current engagement with the ‘flow’ of images within our current era, then its durational nature, from its conception as a nine-day run to the real time remediation and slow viewing of the images that are representative of that run, is potentially significant, telling us that we might want to slow down and take time to look not only at what lies ahead of us but at how we engage with images as documents of the world around us. It has also led me to reconsider the status of the images in themselves as documentation.

3. Developing the Context: Between Artwork and Art Documentation in Performance

Within the context of performance art, documentation has traditionally served as a record of a past (live) performance event through which it can be ‘reconstructed’ and acts ‘as evidence that that it actually occurred’ (

Auslander 2006, p. 1;

Auslander 2012, p. 47;

Auslander 2018, p. 22). However, as Philip Auslander points out, with reference to

Kathy O’Dell (

1997) ‘the reconstruction is bound to be fragmentary and incomplete’ (

Auslander 2012). The connection between performance and documentation has also presumed an ontological distinction between the performance as a preceding event and the document as its authorial record, a status which Auslander claims is ideological. This is related to the idea that documentation (particularly photographic documentation), is a means of accessing the ‘reality’ of the performance, a status which is itself linked to the ideological status of photography as ‘representationally accurate’ and ‘connected to the real world’. This connection to the real world through representation has allowed documentation to be treated as a substitute for the original event. (2012),

10 a status that largely caused the previously stated contentions and antagonisms regarding what constitutes performance.

Peggy Phelan’s (

1993) classic argument against reproduction and its insistence on distinguishing performance from other (reproductive) media has served to enforce a view that a (true) performance in its immediacy exceeds reproduction and thus documentation and, in doing so, has maintained a negative relation to reproductive media as performance (

Phelan 1993;

Westerman 2015).

More nuanced understandings of the relationship between performance and documentation such as those put forward by

Amelia Jones (

1997) and

Philip Auslander (

2006,

2012,

2018), respectively, have challenged the ontological priority of performance to assert a consideration of the document as an artwork and performance in its own right. Jones takes up the idea of documentation as an indexical supplement

11 to live performance to suggest a mutual (or ‘inter-subjective’) co-dependence between the two, elevating the status of the document beyond a mere record of a past performance event. She claims much of our knowledge and understanding of the latter comes from their documentation as ‘textual, oral, video and/or film traces’ (

Jones 1997, p. 11), and ‘the experience of viewing a photograph [or] reading a text is clearly different from… watching an artist perform.’ She states, ‘neither has a privileged relationship to the historical “truth” of the performance.’ Crucially, she insists that there is ‘no possibility of an unmediated relationship’ (p. 12). This is a view shared by Auslander, who concurs that, in these circumstances, the document replaces the absent performance ‘to the extent that an event become a performance through the performativity of its documentation’ (2018, p. 42). The point that both Jones and Auslander are trying to make is that performance documents should not be ‘limited to providing secondary information about performances’, but that they ‘equally, though differently, provide experiences of performances’ (p. 43). Whilst Jones emphasizes the ontology of the document, Auslander goes further to develop a phenomenological understanding of the performativity of the document by insisting that ‘the playback of a recording should be understood as a performance in itself…regardless of its ontological status’ (ibid.). Drawing on Walter Benjamin’s notion of “reactivation”, referred to in a short paragraph in his influential essay

The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936),

12 Auslander (

2018, p. 46) points to Benjamin’s suggestion that technical reproduction can put an original (object or event) within the reach of the ‘beholder’ (or audience) by bringing it to be ‘reactivated’ and experienced in their own] spatial and temporal context. Whilst this is not the same as experiencing the original, the reproduction acts as a kind of ‘conduit’ or channel to be ‘received’ by the beholder wherever they may be (ibid.). What is significant about this is the implication of mediation by Benjamin in the temporary ‘removal’ of the original from its original context and its reconstitution (or ‘reactivation’) ‘via reproduction’, in the beholder’s own setting or situation (p. 49). Although still bound to an ‘original’ past event or object, the document as a “reactivation” becomes an event in and of itself, particular to the time and place in which it is being experienced by the beholder in the present moment.

13Auslander takes this further to identify a category of documentation, which he calls ‘performed photography’, that includes work that ‘had no prior meaningful existence as autonomous events presented to audiences’ (

Auslander 2006, p. 2;

Auslander 2012, p. 49), and were staged solely to be photographed or filmed, thus placing the performance (and our understanding of it as an event) squarely within the space of the document itself: ‘What difference does it make to our understanding of an image in relation to performance documentation’, he asks, ‘that one documents a performance that never really happened?’ (2006, p. 1). Whilst this points to the current role of digital technology in the creation of images in the absence of an original event, it also points to a category of documentation long before developments in digital technology in which ‘performances were staged solely to be filmed or photographed and had no prior meaningful existence as [independent] events presented to audiences’ (p. 2) A key example Auslander refers to is Yves Klein’s

Leap into the Void (1960),

14 a photographic image documenting an apparent action performed by the artist, but which is, in fact, a constructed, composite image: ‘The image we see thus records an event that never took place except in the photograph itself’ (2006, p. 2; 2012, p. 49). The point that Auslander is trying to make is that

Leap into the Void is not any less of a performance because it never actually happened. It is the photograph itself and our consideration as an audience of the action depicted in it that makes it a performance (

Westerman 2015). As such, we should think of the document as he concludes, as less of ‘an indexical access point to a past event but [we should perceive] the document itself as a performance’ (

Auslander 2006, p. 9;

Auslander 2012, p. 57). Auslander advances this through a reconsideration of the notion of performativity, as (an action) taking place within the very act and creation of the document itself. He points to an example of this in an early performance artwork by Vito Acconci called

Blinks in which the artist takes a photograph every time he blinks, ‘while walking a continuous line down a city street’ (

Auslander 2006, p. 4;

Auslander 2018, p. 29) The work fulfils the traditional functions of performance documentation in that the photographs produced are evidence that the work took place and that Acconci performed the work ‘allowing us to reconstruct the performance’ (ibid.). However, like

The Great Orbital Run, in its conception as a performance, and the later

The M25 in 4000 Images, as performance documentation, they do not serve the traditional function of performance in that they: ‘do not actually show [the artist] himself performing: they are ostensibly photographs taken by [him] while performing, not photographs of [him] performing’ (

Auslander 2006, p. 4;

Auslander 2018, p. 30). In other words, it is the ‘performance action’ of taking the photographs that constitutes the performance: ‘the photographs produced

as an

by the performance rather than

of the performance’ (ibid.). If traditionalists of performance have argued that a live performance cannot be ‘reproduced’ or ‘represented’ to put forward an argument against documentation, then this is effectively turned on its head by the action of documenting an event as a performance which ‘constitutes it as such’ (2006, p. 5).

15 Importantly,

Auslander (

2018, p. 30) also stresses that the performance was not made available to an audience ‘apart from [through] its documentation’, at least not knowingly:

A look at the photographs shows that the street was deserted- there were no bystanders to serve as audience…the only thing the bystanders would have seen was a man walking and taking pictures: they would have had no way of understanding they were witnessing a performance.

Crucially, for this essay, ‘it is only through his documentation that his performance exists qua performance’ (2018, p. 31). This is something to consider in relation to the artist’s book, that through the act and structures of making, might offer a means of rethinking its potential as an artwork and document.

16A further contemplation on the performative dimension of the document that is beyond the scope of this essay to discuss in detail but that might give us further food for thought, is a possible rethinking of the relationship between performance and document as existing between representation, in the intersection between action and image. This could go some way towards reconsidering the fraught relationship between performance and documentation and provide another space for rethinking representation within the artist’s book. The relationship between performance and documentation, as has been stated, has often existed unhelpfully at opposing polarities that, on the one hand, has performance in a negative relation to reproductive media (

Phelan 1993) but that, on the other hand, has these as generators of the performance event (

Auslander 2006,

2008,

2012,

2018). The former ‘effaces any connection between performance and its traces’, whilst the latter ‘elides any difference between action and artifact’ (

Westerman 2015, p. 4). Jonah Westerman proposes a rethinking of this relationship in performance’s relationship to media, whilst respecting their distinctions. This has its roots in the notion of “intermediality”, a term that emerged in the 1960s to reflect artwork that fell ‘between media’ (ibid.).

17 In Westerman’s reconfiguration, he proposes an ‘inter-zone’ between ‘art-media’ and ‘life media’ (p. 5) as a means of considering the relationship between action and mediation in performance. With its roots in the notion of the “readymade”, a term that refers to ‘found objects’ that found their way into art galleries to become artworks, “intermediality” brings these together in the merging of art and life (ibid.). This uncertain status is what the artist Marcel Duchamp referred to as the “infrathin” (or in the French, “inframince”)—‘too thin to be thin or more thin than thin’—it refers to a space that Westerman describes as being ‘between two elements that remains intelligible and perceptible but where one stops and the other starts is unidentifiable [and] too fine to grasp’ (

Westerman 2015, p. 6). Amongst the examples Westerman gives via Duchamp, is ‘the space between the front and back sides of a sheet of paper’ (ibid.).

Westerman argues that performance brings ‘art-media’ and ‘life-media’ together along an ‘infrathin edge’, meaning that, when we consider performance, we should not ‘lament its irretrievable loss’ or ‘erase its distinction’ but focus on the ‘threshold moment between these two in a co-mingling of media- what we could call ‘the inframedium’ (ibid.). This reimagines performance ‘less as a thing in itself. and more as a spatial situation, as a mobile and profoundly indistinct dividing line that joins form to experience and by virtue of its specific siting in a given work, describes the location and composition of each’ (ibid.). When applying this to an image, whether it is through the live mediation of the document as in

The Great Orbital Run or as a printed document within an artist’s book as in

The M25 in 4000 Images, the performance happens ‘at the threshold between action and image’, a ‘place that is impossible to identify definitively to cordon or sequester’ (

Westerman 2015, p. 7). With this approach, Westerman argues, ‘we no longer have to worry about the time of performance, about whether it was then or now or always and think more about where it happens, what brings it together and how that spatial situation both questions and describes our own vantage onto the nexus of art and life’ (ibid.).

4. What Makes It a Book: between Artwork, Art Documentation, and the Artist’s Book

The above reflection on the performativity of the document draws an interesting parallel with what might be termed the “performativity of the artist’s book” and with the hybrid nature of the artist’s book. In my introduction, I referred to the ‘‘Mongrel Nature” of artists’ books, using Clive Phillpot’s characterization via Anne L. Burkhart’s essay to point to the multi-disciplinary nature of artists’ books and their status as art forms that operate ‘against singular definitions’ (

Burkhart 2006, p. 249). Burkhart suggests that Phillpot’s term ‘hints at the wide variety of works that can be categorized as artists’ books’ maintaining that ‘there is no consensus regarding definitions of artists’ books, nor is there a single form, production method, or conceptual framework that embodies what an artists’ book is’ (ibid.). It is precisely their ‘hybrid nature’ and their ‘multi-sensory, experiential and culturally embedded aspects’ that are of interest to her in advocation of their use in art-education. Likewise, in the first chapter of her book

The Century of Artist Books (2004), Joanna Drucker states that what is unique about the artist’s book is precisely its ‘elusiveness’ and its inability to be defined in any singular way. She claims the growing popularity of artists’ books is ‘attributed to the flexibility and variation of the book form, rather than to any single aesthetic or material factor’ (p. 1). Thus she proceeds her interrogation of artists’ books across a ‘zone of activity’ that sits ‘at the intersection of a number of disciplines, fields and ideas- rather than at their limits’ (ibid.). It is this space of intersection, rather like the ‘threshold’ that Westerman describes and that I referred to in the section above, that is of particular interest here. That is not to say that ‘anything goes’ in an uncritical sense. As Burkhart suggests, via Drucker, ‘a consideration of differing opinions can be illuminating and help “put fundamental parameters into place for [a] critical evaluation of artists’ books as an artistic practice”’ (

Burkhart, quoting Drucker 2004, p. 249).

18 Drucker’s ‘zone of activity’ is helpful in this respect as it eschews the idea of placing artists’ books within a single category to suggest the meeting of ‘elements or activities which contribute to artists’ books as a field’, and for the emergence of a ‘space made by their intersection’ (

Drucker 2004, p. 2). For scope and focus, I will continue with reference to Drucker’s first chapter that outlines the

Artist’s Book as Idea and Form, although I acknowledge there are other authors I could refer to for a more extended discussion.

19 The activities that Drucker lists include:

Fine printing, independent publishing, the craft tradition of book arts, conceptual art, painting and other traditional arts, politically motivated art activity and activist production, performance of both traditional and experimental varieties, concrete poetry, experimental music, computer and electronic arts, and last but not least, the tradition of the illustrated book, the livre d’artiste. (Ibid.)

Her mission is not to treat artists’ books as ‘attributes or sidelines of the movements with which the artists are associated’, but as a field of artistic practice in its own right, ‘as books and as examples of artistic involvement with the book as a form’; to look at the latter as a means of critical interrogation, ‘not merely [as] a vehicle for reproduction’ (p. 9). In the same way, The M25 in 4000 Images as an artist’s book is not merely ‘a vehicle for reproduction’ (although, paradoxically, it could be said that its predecessor in The Great Orbital Run was precisely that in its interrogation of the document), it enables a more complex investigation to develop not only of its status as documentation but through its conception as an artist’s book.

Drucker points out that artists’ books have ‘served to express aspects of mainstream art which were not able to find expression in the form of wall pieces, performances, or sculpture’ (p. 9), hence their easy alignment with “intermediality” as a combination of all of these. Similarly, she draws attention to how artists have exploited the ‘documentary potential’ of the book form whilst also engaging with the book’s ‘capacity to be a highly malleable, versatile form of expression’ (ibid.). At the same time, she is also quick to remind us that ‘not every book made by an artist is an artist’s book’ (ibid.).

20 Ultimately, Drucker leaves it to the ‘informed viewer’ to determine what makes a book a book in ‘the extent to which [a book work] makes integral use of the specific features of this form’ (ibid.). As such, it is the extent to which a book critically operates as an examination of ‘a book’s book-ness, its identity as a set of aesthetic functions, cultural operations, formal conceptions, and metaphysical spaces,’ that makes it a book (ibid.). Importantly, whilst a book’s structure (through an ‘attention to materials, their interactions and content bound within a book’) may be an key ‘component’ of a ‘successful’ book, it is not enough on its own ‘to constitute the substance of an artist’s book.’ A book for Drucker has to be more than a finely crafted product; an artist’s book, on the contrary, can be badly or sloppily made, ‘falling short of perfection’ in terms of production values. But, to ‘succeed’ in Drucker’s terms, it has to have ‘some conviction, some soul, some reason to be and to be a book’ (p. 10). I would tend to agree.

Drucker notes the development of the artist’s book in the 1960s, particularly in the United States as a means of independent print production by artists to produce inexpensive multiples and its significant impact on artists’ work. It is not coincidental that conceptual artwork of the 1970s include a number of artist’s books that were more easily able to extend previous experimentations with the form from artists’ forays in the earlier part of the century (ibid.). However, as Drucker has observed, this is a field that that defies easy definitions and has multiple entry points, where ‘there are always inventors and numerous mini-genealogies and clusters, [and]… which belies the linear notion of a history with a single point of origin’ (p. 11).

21 More pertinent f is the book’s object-like status and its alignment with sculpture in what Drucker defines as ‘large-scale book works which are as much installation and performance as object’ and which have their roots in 1960s Fluxus (p. 13). She notes a trajectory in artists’ work that have developed from this since the 1980s in large-scale installation artworks that use multiple media and components: ‘ambitious in scale and physical complexity, closet size to room size, with video, computers and any moment now a virtual reality apparatus’ (ibid.). Many of these are acknowledged as a natural development of the artists’ previous involvement with artists’ books or at least the ‘book’ is considered an integral part of the installation.

22 These, as Drucker suggests, ‘pose important questions for the identity of a book and its cultural, social, poetic or aesthetic functions,’ but for her they also run the risk of ‘stretching the parameters’ of what defines an artist’s book. However, for me, it is this precisely the potential ‘awkwardness’ in the interrogation of what an artist’s book might be that I find particularly compelling. It is unfortunate that Drucker is dismissive of these approaches in her study, somewhat contradicting her earlier claims of the hybrid nature of the artist’s book. In my view, a book can still be a book if it poses questions of what a book is or does. It does not necessarily have to function ‘traditionally’ as a book, but can function nonetheless as an artist’s book by maintaining some idea of ‘book-ness’ or ‘book identity’ (ibid.) about it.

As Drucker acknowledges, we have already experienced through developments in electronic and digital media, the book as ‘a mutating archive of collective memory and space- … functioning as extension of the artist’s book form’ (p. 14). In this sense, I think it is absolutely appropriate for a book to be non-linear and to ‘[provide] a reading or viewing experience sequenced into [

an infinite rather than finite] space of text and images’ (p. 14).

23 Drucker concludes her chapter by stressing again that: ‘There are no specific criteria for defining what an artist’s book is’ whilst maintaining that ‘there are many criteria for defining what it is not, or what it partakes of or what it distinguishes itself from’ (p. 14). In her attempt at a definition she insists on the artist’s book as a form that ‘draws upon a wide spectrum of activities’ whilst maintaining its uniqueness in duplicating none of these. As such, it is its ‘own genre’, with its ‘own forms and traditions, as any art form or activity’. Unbound by the ‘constraints of a medium’ (ibid.), Drucker acknowledges that it is, at the same time, a field that ‘needs description, investigation and critical attention before its specificity will emerge’ (p. 15). I would add to this the word ‘disruption’, for if, as she suggests, we are to engage with books ‘which are artists’ books’ and to ‘allow that specific space of activity, somewhere at the intersection and boundaries and limits of all the above activities, to acquire its own particular definition’, then a little critical disruption is necessary.

5. The Performativity and Agency of the Document: Artists’ Books as Spatial Practice

In her critical survey, Drucker devotes a chapter to the

Book as Document, acknowledging the capacity of artists’ book to ‘serve as documents- either reproducing a record of experience and information or serving as the document themselves’ (

Drucker 2004, p. 335). It is the ability of the book to ‘serve as a record extending aspects of conceptual and performance art into book form’, that is of particular interest to her (and also to me) in its function as a ‘space of information’ (ibid.). Although she gives numerous examples of approaches and form from the ‘banal to the extraordinary’, I find it odd that she aligns the book as a document to a ‘standard format’, which she states ‘serves very well as a place in which an experience, account, or testimonial can be produced’ (ibid.) Whilst I agree with the latter, in the notion of the book, as a ’holder of experience’ (

Macken 2016), I think Drucker’s consideration needs to be extended beyond the ‘standard format’ she refers to, which contradicts her previous assertions. To expand on Drucker’s consideration of the book as document, I would like to return to the performativity of the document and the notion of the ‘inframedium’ proposed by Westerman that I referred to in the previous section. To recap, this reimagines a performance ‘less as a thing in itself and more as a spatial situation, as a mobile and profoundly indistinct dividing line that joins form to experience and by virtue of its specific siting in a given work, describes the location and composition of each’ (2015, p. 6). I will align this specifically to Marion Macken’s essay

Designing with/ for/ through the Existing: Artists’ Books and Documentation (2016) as a means of furthering my previous discussion of the document and taking Westerman’s proposition towards its consideration through the artist’s book and the artwork that is the subject of this essay,

The M25 in 4000 Images.In her essay, Macken aligns the book form as having ‘inherently within it the notion of the archive’, linking this to its status as a document. As a ‘record of experience’, she claims, it serves as a document in itself (p. 13). The text goes on to survey the ‘repository quality’ of books and their ‘archival role in the documentation of event, place, journey and interior space’ (ibid.). Whilst primarily written in the context of architectural and interior design, Macken makes an important distinction between the archival role of the book as ‘housing post-factum documentation’, in relation to the documentation of something that has already been constructed or made, in the contexts of teaching of architecture and the use of the word ‘documentation’, which predominantly refers to ‘representations that are made to ‘get to’ a design’ (i.e., ‘tangible representations’ of proposals that have no ‘tangible existence’), and which may never get constructed or made (ibid.).

Moreover, she associates the book itself with spatial practice, that, due its format, physical qualities, and characteristics, it may be considered ‘as a form of three-dimensional representation within spatial practice’ (ibid.), as opposed to something that is considered within the context of ‘spatial design as content’. Different from (architectural) models or orthographic drawings, the book is proposed as a complimentary format for spatial representation that is able to form close connections with architectural models and drawings and yet remain utterly distinctive. Its formal qualities of ‘pagination, sequentiality, and the physicality of the page’ as well as the consideration of its interior, as ‘a folded model with volume’ (ibid.), may reveal and facilitate certain aspects of the design process; however, for Macken, it is the repercussions for this in spatial drawing and representation that are of particular interest and which, more importantly, enable the book to have ‘agency’ within spatial practice (ibid.).

Rather than the concern for ‘space yet to be materialised’ or for proposed drawings of ‘imagined buildings’ (ibid.) that are dominant within architectural representation and commonly referred to as “documentation”, Macken’s interest in ‘post-factum documentation’ is in the ‘words, drawings and models that come after the building or event, not leading towards it’ (ibid.).

24 In relation to this, it is the repository quality of books, alongside their documentary function and focus that she considers a core quality and role within spatial practice. Thus four identified categories of documentation are considered in terms of ‘

Documentation as Content;’ ‘

Documentation as Object and Outcome’; ‘

Documentation as Process’ and ‘

Documentation as Tool’. Each of these is proposed as a means of examining the role of the book and to put forward the argument for how the book format brings agency to spatial practice. I would like to end by applying these to my own consideration of the document in the creation and conception of

The M25 in 4000 Images, as a ‘post-factum’ physical document of a performance artwork (a journey undertaken on foot) that was originally live-streamed digitally, ‘page by page’, through a continuous sequence of images. Although not yet a ‘book’ in its original conception, the artwork nonetheless initially existed in relation to documentation in the live relay of images that were subsequently made into a tangible object.

In the category ‘

Documentation as Content’, Macken aligns architecture’s relationship to documentation as vital in the belief between what is real and what is physical, but points out that the existence of the ‘thing itself’, as almost exclusively ‘through its representations’ (2016, p. 13).

25 In relation to this, she acknowledges the role of the book within the contexts of conceptual and performance art ‘to act as a document’ and ‘as the holder of experience, account and testimonial for diaristic and personal statements’ (ibid.). Such books, she says, ‘bear witness and give enduring form to personal experience and document that which has passed…[they] record the ephemeral in another format as documentation’ (ibid.). It is not clear whether Macken is referring to the performer or to the audience or to both, but she alludes to the possible need to hold onto something beyond the event and experience itself, in the documentation of place itself. This is made clear in the examples of artists’ books she gives that enable the documentation of place ‘through different points of view’, through an embedded imprint or trace from a specific site, and through the ‘movement of the body through space’ that is ‘tracked’ in an ‘accumulation of pages’ (ibid.). Important in this configuration is the consideration of time ‘through association’ and through the ‘seriality, sequencing and “reading” of the book’ (ibid.).

The M25 in 4000 Images aligns itself with this understanding in its existence as the sequential document of a series of mediated images of the artist’s viewpoint of a nine-day journey, undertaken on foot whilst running. The (concertina) book format enables further experimentation, as it does for Macken, ‘with notions of seriality, sequence, narrative’ (2016, p. 15), though in its singular status as a tangible object, not necessarily to a wider audience, but to a different one (

Figure 4).

In the category ‘

Documentation as Object and Outcome’, Macken quotes from K. Michael Hays in a statement that strikes a chord in the relationship he makes between the architectural object or pictorial surface and the construction of an image of the outside world. He refers to this as ‘a kind of surrogate for the perceiving subject.’

26 If the

M25 in 4000 Images is a sequence of images made of the artist’s viewpoint whilst running that can only be experienced through documentation, then whether it is live-streamed, replayed subsequent to the event (in its previous incarnations as

The Great Orbital Run), or represented as a physical document, it is a surrogate for any audience experiencing the work. The documentation of the landscape depicted in the image/s is experienced by an audience through the artist’s viewpoint and experience of the journey undertaken. Macken refers to projects undertaken with (architecture) students in which the notions of ‘experimental travel’ and ‘invisible cities’ are proposed through the creation of a (concertina) book, as a means of ‘exploring the city and the documentation of journeys, in response to a literary provocation, such as a story’ (2016, p. 15). The intention is to enable the re-examination of a familiar environment ‘to bring fresh eyes to the worlds we can sometimes blindly inhabit’ (ibid.). The

M25 in 4000 Images becomes a ‘vehicle for looking anew’ (ibid.) at the terrain surrounding Greater London that is less about what is depicted in the image itself than what the sheer quantity of the physical pages themselves represent. In this sense, the sequential nature of the images and their physical placing in space uses the agency of the concertina book form to ‘explore how the landscape [surrounding London], operate[s] over time and space and how [the artist’s] movement through the landscape [operated] in the form of a journey’ (ibid.) in the physical exploration of that space. The idea of narrative is implied in the representation of both the landscape reproduced in the printed pages and in the understanding of its exploration as a journey undertaken through human agency in time and space that was first mediated through the live, digital relay of images over a period of nine days from the artist’s viewpoint and location in the landscape itself. (

Figure 1,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4)

The category ‘

Documentation as Process’ considers tacit understanding in the design process of making a book that Macken states is ‘not something fixed, crystalline or frozen… It is processual, fluid, in constant flux… It can never reach finality or completion’ (ibid.). As an artist, I am loathe to use the word ‘design’ precisely for this reason. In this instance, the word conceptual is perhaps a better word for something that points to what Macken refers to as the ‘possibility of new understandings’ (ibid.).

The M25 in 4000 Images uses material from the original artwork,

The Great Orbital Run to (in Macken’s words) ‘elicit new responses from the past; and plays forward to elicit new responses from the [present and from the] future’ (ibid.).

27 Its expandable (unbound) form enables it to be flexible and to be shown differently as an exhibited object that can adapt, squeeze, stretch, and shape itself to the specifics of different spatial contexts and locations. The question of re-interpretation becomes implicit in this process. This includes the context of design, which is re-interpreted as a process. This conception of the term enables the artwork to exist, as Macken suggests, ‘between representation: the outcome of one task is the beginning of another, of moving forward due to what has been created’ (ibid.), as a reflective document and outcome of a process. Another way of looking at this is in the implied narrative given over by the process of documentation, as a record of something undertaken. In Macken’s case, this refers to the ways in which (architecture) students operate within the confines of the design studio. In the case of

The M25 in 4000 Images, it refers, in the first instance, to the original task undertaken in the making of the

Great Orbital Run as an artwork, in the undertaking of the run itself, the live process of documentation through the live streaming of images and in the narrative enacted in its viewing by an audience; all of these are part of the work’s process. In the second instance, it refers to the making of the physical document from the original electronic images and to the narrative implied in the work’s physical output as an artist’s book/ artwork, that is, a document reflecting the original journey undertaken. In both instances, it is an ‘agent of documentation’ (2016, p. 16). If we consider the document (or book) as a compilation of images, it could also be referred to as a portfolio, repository, or archive. Macken suggests that the core repository no longer exists in the post-digital realm (ibid.). Whilst this is true in relation to our previous understandings of a repository as a physical domain, the storage of digital material in digital repositories exists nonetheless (whether it is on a memory stick, hard-drive, or on ‘the cloud’), but it is a continuous problem and a work in progress that reflects the precarity and speed of technological development and its ephemeral status.

The question of knowledge is also brought into the equation through the ways in which process is understood as an ongoing mechanism and act of learning ‘embodied in the doing’ (ibid.).

28 This not only refers to making as a process in itself but to the ways in which ‘immersion in the act of making’ also enables a process of analysis, critical reflection, and evaluation (ibid.). This brings us back to the idea of the unfixed nature of the artwork as a continuous work in progress that compels the artist to ‘hover between production and reflection’ (ibid.). This is demonstrated first in the

Great Orbital Run, for which the run and the live streaming of images becomes both the subject of the work and also the means of documenting a process of working. Secondly, in its reconfiguration as the

M25 in 4000 Images, the process of making is embedded in the ‘act of translation and transformation’ (ibid.), that makes a digital repository of images visible and tangible, the accumulation of images in the (concertina) book representing a passage over time and space of the original journey undertaken.

In the final category, ‘

Documentation as Tool’, Macken talks of (architecture) students ‘making scaled drawings rather than full-scale landscapes’ (2016, p. 16). Since the ‘translation from paper to full-scale projects rarely occurs’, she says, the ‘drawings become an end in themselves.’ Making books, she argues, ‘provide a vehicle for students to work [differently], with a full-scaled object’; its three-dimensionality inviting them ‘to make and handle their final work, rather than [present] scaled images of it’ (ibid.). I am not sure I entirely agree with this argument since it puts forward the view of the book as a finite object, contradicting what was previously stated as something unfixed and in flux. The question of scale is also questionable since the book may include images that are not drawn or photographed to the actual scale of what is depicted. However, it presents an interesting paradox when considering the object status of the book and what is represented inside it. In the case of the

M25 in 4000 Images, the individual photographic images cannot be the full scale of the landscape they depict, but they do relate to the scale of their origin as digitally mediated images. These are low-resolution,

poor images29 and their optimum scale as printed images relates directly to the small size of the screen on the original mobile phone they were taken on. In this sense, they could be considered full-scale. Their original presentation in the

Great Orbital Run, as singular live-streamed ‘pages’, enabled documentation as process to be mediated on a larger scale as a projected image to an audience located elsewhere as it was taking place; their reconfiguration as

The M25 in 4000 Images makes it possible to have a closer encounter with the image through pages that are physical and tangible. Whilst they cannot be ‘turned’ and the ‘book cannot be handled in the conventional way’ (ibid.), the hidden aspect of the folds of the book, and the fact that the images themselves cannot be immediately seen in their entirety, allows an element of intrigue to become part of the encounter with the work. The ‘changed format’ invites a different way of engaging with the book and for a haptic and intimate relationship to develop in the careful prising open of its pages (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

6. Closing Remarks

Reconsidering The Great Orbital Ultra Run as the M25 in 4000 Images has enabled a focussed interrogation on the nature of the document to evolve beyond an initial contemplation that focussed more specifically on its relationship and its contentions within a performance art context. Whilst this relationship is very relevant, and it continues to be pertinent in an age of ever-evolving technological development, it is also a subject that is very well-known and much discussed within contemporary art contexts and debates on performance. However, it was necessary to articulate and develop the critical context between art work and art documentation in performance before extending this to the artist’s book. Westerman’s notion of the ‘inframedium’ was a helpful addition in its function as a critique of the polarizing distinctions relating to live performance and its documentation and also in its relationship to ‘intermediality’, in the proposition of a ‘co-mingling of media.’

This was useful in providing a bridge towards the discussion that followed the document as an artists’ book and the consideration of the latter in relation to its ‘hybrid status’. To open the notion of the document up within the context of the artists’ book allowed me to step outside my comfort zone and to find new ground and new material to think about the document in a different way. Drucker’s attempt at a definition was helpful in the first instance in enabling the discussion of the form of the artist’s book to be considered more specifically. Her initial proposition of defining artists’ books as a ‘zone of activity’, rather than within a single category, appeared to embrace intermediality by placing artists’ books ‘somewhere at the intersection and boundaries and limits’ of a range of media as a means of ‘acquiring its own particular definition’ (

Drucker 2004, p. 14). However, despite its critical focus, for me, it fell short of this by focusing too much on ‘what an artist’s book is not’ rather than allowing the questions of what defines an artist’s book to open up further critical intervention, discussion, and possible disruption towards new considerations, especially in the contemplation of the artist’s book as an object, sculpture, or as part of an installation.

The further consideration of the document, with specific reference to Macken’s understanding in her short essay in the relation to three-dimensional representation within spatial practice, enabled a more nuanced and detailed understanding of the document and of the artist’s book to develop that took me to unexpected places I would not have otherwise considered. I am not a book artist and the context of artists’ books is one that is new to me, but it is something I have increasingly had to consider in relation to my artistic practice through the development of artworks that sit on the edge of what might be considered an artist’s book. By that I mean they do not follow traditional conventions of artist’s book, in that they are hybrid objects that tend to come after a related artwork and allow a reconsideration of the original artwork, taking it in new directions. Often un-editioned and without a “codex” or “spine”, these are books in other ways: in their uses of volume, sequence, folds, “pages”, and other attributes that enable their consideration as a book nonetheless.

Macken’s essay and its four categories of documentation in the consideration of ‘Content’, ‘Object and Outcome’, ‘Process’ and ‘Tool’, challenged me to delve more deeply into a detailed analysis of both The Great Orbital Run and its reconfiguration into The M25 in 4000 Images and, through its associations with the document and the book, to discuss relevant and meaningful concepts that I had previously found hard to articulate in relation to this artwork in its new status. Such concepts included the notion of the book as a thing in itself and as a ‘holder of experience’; the book as the documentation of place and as the record of the movement of the body in space; the book as a surrogate for the viewing subject; the book as a vehicle for looking differently at what is represented within its pages; the book in the form of a journey; the book as between representation; the narrative implications of the book; the book as embodied learning; and the book as a means of engaging with and of presenting things differently. All these are what Macken refers to as the ‘agency’ of the book. Its alignment by her within spatial practice gives it a new dimension. That, given the original status of The M25 in 4000 Images, as The Great Orbital Run, a live performance that took place in an external environment, seems particularly fitting.