1. Introduction

… there is one thing that reading will never be and that is something new.

Simon Ford, The Art of Reading

1

From the prehistoric advent of image making, the development of handwriting into codices, volumes and manuscripts, and the revelation of the printed book, to e-books of the present, reading has provided a route in the development of visual language and communication. Yet, where the artist’s book fits into this historiography has always been a matter of much debate.

The danger has always been to think about artists’ books as a medium in and of itself that should be understood in isolation from other modes of expression.

In today’s world of competing technologies, the flexibility of the book as a format to absorb change and its ability to re position are what make it such a dynamic medium in which, to reflect on, respond to and simply become practice and artefact. Whether engaging with viewers in gallery, library, bookshop or indeed any other location, the book is a primary medium for the artists’ imagination in exploring the limitless range of function and form.

Nowhere is artistic intention more concretely wed to the circumstances of its production and reception than in the field of publishing. Whether a limited edition artist’s book, a trade publication printed in a run of 10,000, a compact disk, or a website that reaches millions, the number of projects published by artists is at an all-time high. Never before have so many artists taken an interest in manipulating their representations in print.

This paper looks to broaden the discussion of the idea of the book within contemporary art through looking at the presence and role of book works within the context of the art biennale. By examining the assimilation and presence of the book at the current Venice International Art Biennale and collateral events in the wider locality of Venice itself, the city in which I work and live as an artist, writer and curator, we can come to understand the ways in which producers and publishers operating in this expanding and influential sector create context and dissemination for the book, in and through exhibition, installation, performance and documentation.

For many, the International Art Biennale, Venice, now in its 58th edition represents a primary arena for artists and curators on a global scale. The exhibition, which takes place over a period of seven months, is without doubt one of the broadest exposés of contemporary practice with attendance at the previous Biennale in 2017 registered as over 615,000 visitors and the 2019 event set to surpass this. Entitled ‘May You Live In Interesting Times’, it takes terms of reference from a counterfeit curse, at a moment when the digital dissemination of fake news and ‘alternative facts’ is corroding political discourse and the trust on which it depends: ‘It will not have a theme per se, but will highlight a general approach to making art and a view of art’s social function as embracing both pleasure and critical thinking. The Exhibition will focus on the work of artists who challenge existing habits of thought and open up our readings of objects and images, gestures and situations’ (

Rugoff 2019). The use of the term ‘reading’ is here being applied in broad terms, as noted by Clive

Phillpot (

2003):

The act of reading has been stretched from reading a literary work, to reading a map, to reading a painting, to reading a city, but in essence it applies to the decoding of writing.

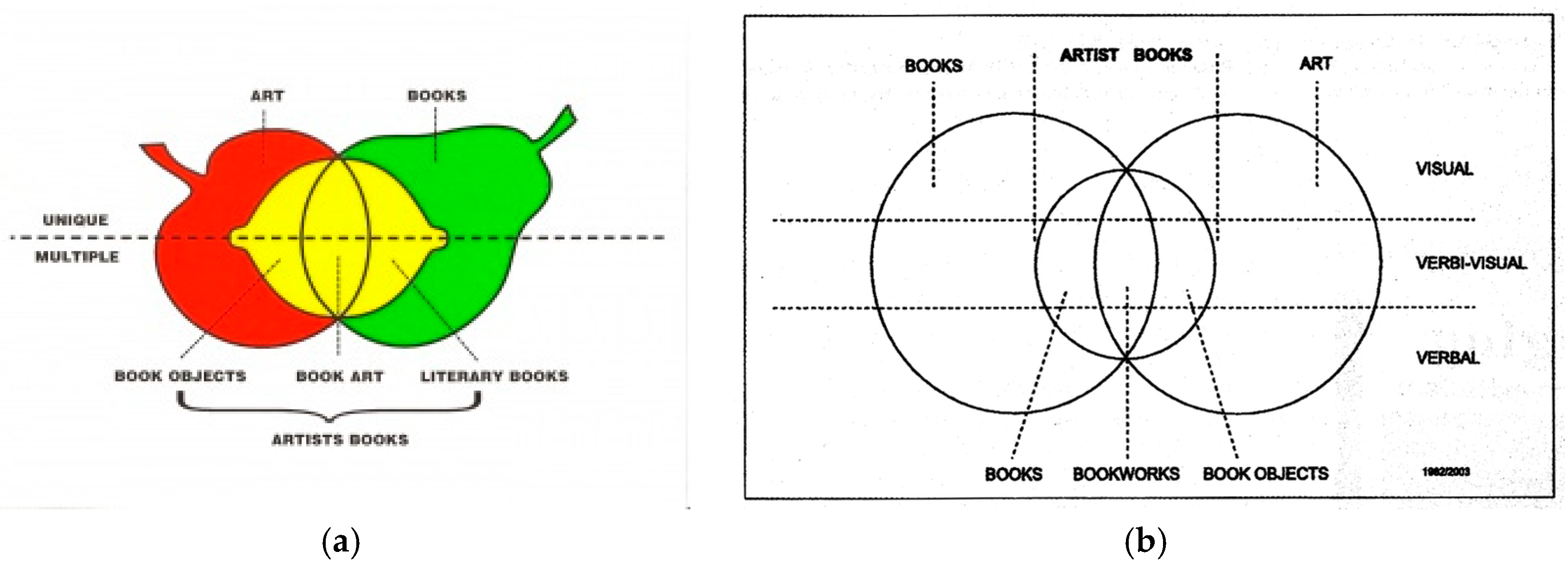

Since 1982, Clive Phillpot (curator, author, and librarian, Chelsea School of Art, UK and MoMA, New York) has tried to define a location for artists’ books within the greater art/book milieu. This diagrammatic overview, visualised as a ‘fruit’ version in 1980s and further distilled in 2003, is still a useful point of reference having provided the fluid term ‘verbi-visual’ (

Figure 1).

Ralph Rugoff, curator writes that ‘May You Live In Interesting Times’ is to be formulated in the belief that human happiness depends on substantive conversations, because as social animals we are driven to both create and find meaning, and to connect with others. From the objectives of the biennale: … to underscore the idea that the meaning of artworks are not embedded principally in objects but in conversations—first between artist and artwork, and then between artwork and audience, and later between different publics (

Rugoff 2019). So, how are these conversations initiated within the arena and what role does the artist’s book play in this connectivity?

Below are a selection of ‘conversations’ on offer in the curated central pavilion of the Giardini: presented in isolation in a glass case, ‘The Encyclopedia of Invisibility’ by Tavares Strachan makes reference to the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768). The notion of encyclopaedia, shelved volumes, once represented an investment in enlightenment and education but is now somewhat redundant in the age of the Internet and Wikipedia. Growing up in the Bahamas, formerly a British colony, Strachan came to understand the historical nature of encyclopaedia as a tool of imperial conquest and power over knowledge—a signal of cultural domination. Strachan’s large single volume of 15,000 entries describes people, places, objects, concepts, artworks, and scientific phenomena not to be found in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, a personal re-writing of history, selected printed pages from which are included in the large scale collage works surrounding the display case (

Figure 2).

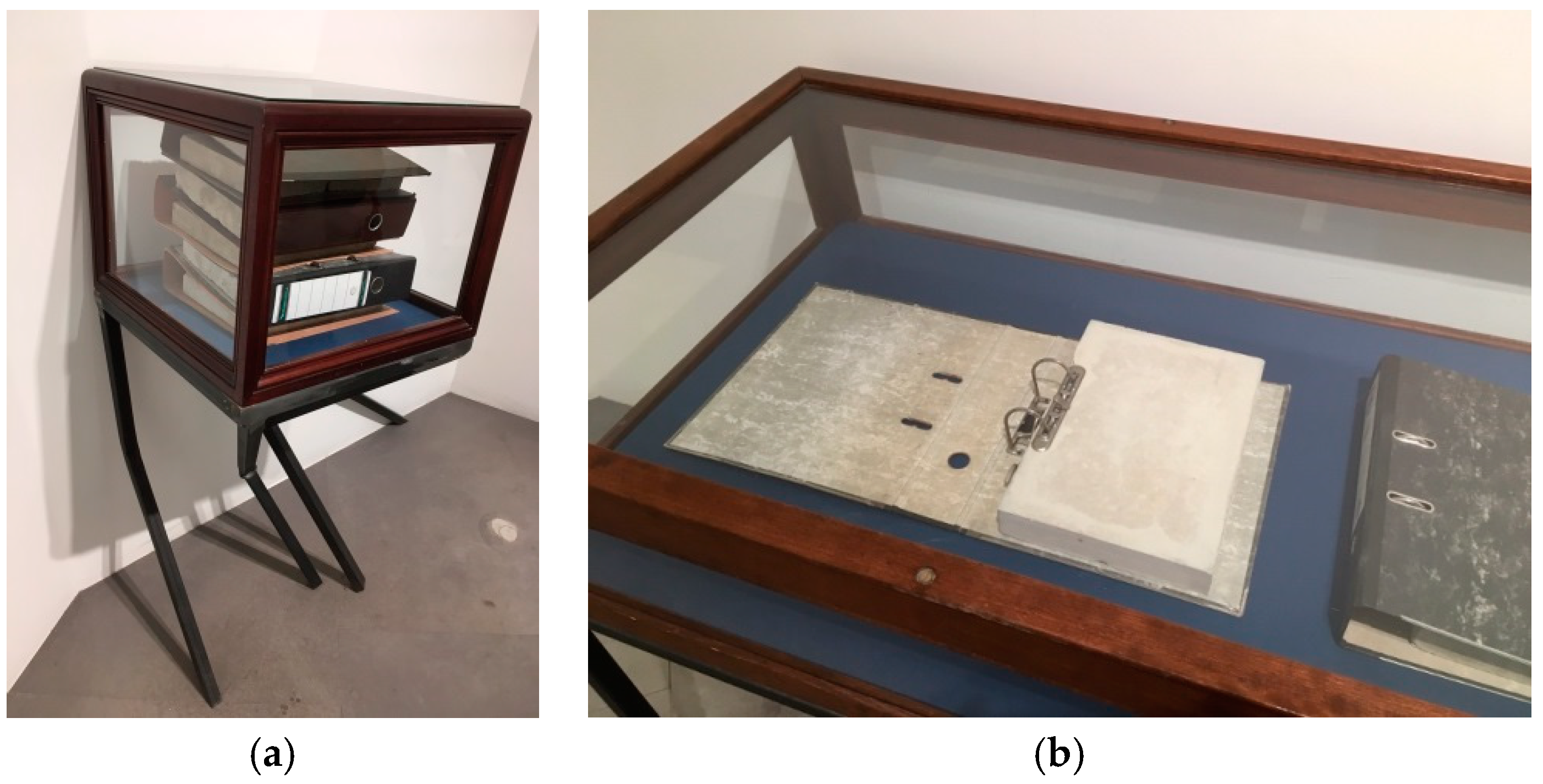

Jesse Darling’s, Epistemologies are presented in purpose made vitrines. The ‘Shamed Cabinet’ with spindly legs, which seem to buckle underneath its weight, contains a stack of archival binders with contents resembling compactly filed documents, but which are in fact cast concrete. The ‘Limping Cabinet’ similarly contains opened out ring files with blocks of concrete inserted. These cabinets of curiosity both form part of a larger installation, ‘The Ballard of St Jerome’, presented at Tate Britain in 2018. Set in the library, the tale of St Jerome’s kindness and compassion towards a ferocious lion, who then becomes his faithful companion, inspires Darling in this work to explore how meaning and value are assigned through the dynamics of power and also includes other playful sculptures and drawings (

Figure 3).

Chinese artist Yin Xiuzhen presents a used bookshelf made of recycled materials. Each item of used clothing is archived as one book, making it a unique piece telling its own story. The books with contrasting soft textiles from all around the world are compacted together, referenced by the buttons and label size on the spine. Conceived as a library, the work on show is just one of 30 bookshelves which reveal all the garments, when viewed from the rear (

Figure 4).

Shilpa Gupta’s, ‘For in your tongue I cannot fit’ (2017–2018), invites individual participation within a multi-point sound installation which addresses the violence of censorship. Described as a ‘symphony of recorded voices’, 100 speakers and microphones, speak or sing the words of 100 poets who have been imprisoned for their work, the corresponding verse printed on paper waiting to be read (

Figure 5). Although not in the form of a book, this work draws the viewer in, towards a personal sensory experience of pages, reading and understanding.

Without being confined to the numerous definitions of what an artist’s book can be,

2 the work highlighted here aims to identify and reference ideas of ‘bookness’, where artists are exploring ground using mechanisms of all aspects of the book as interpreted and re-presented in relationship to their individual practice and experience of the world. A sensibility expounded by the artist Les Bicknell:

The book is a symbol of power and knowledge, a tool which communicates directly; it is a form that is understood in these terms. Repositioning its context and redirecting its purpose challenges these very notions. The work becomes a question rather than an answer, collaboration in the mind and hand between maker and reader/viewer.

3

There are a number of diverse contexts evident here, which present books within installations instrumental in creating dialogue with the viewer, dealing with powerful ideas through meaningful experience. An interaction which seems to be an important objective for curator Ralph Rugoff who states that ‘Ultimately, Biennale Arte 2019 aspires to the ideal that what is most important about an exhibition is not what it puts on display, but how audiences can use their experience of the exhibition afterwards, to confront everyday realities from expanded viewpoints and with new energies. An exhibition should open people’s eyes to previously unconsidered ways of being in the world and thus change their view of that world’ (

Rugoff 2019).

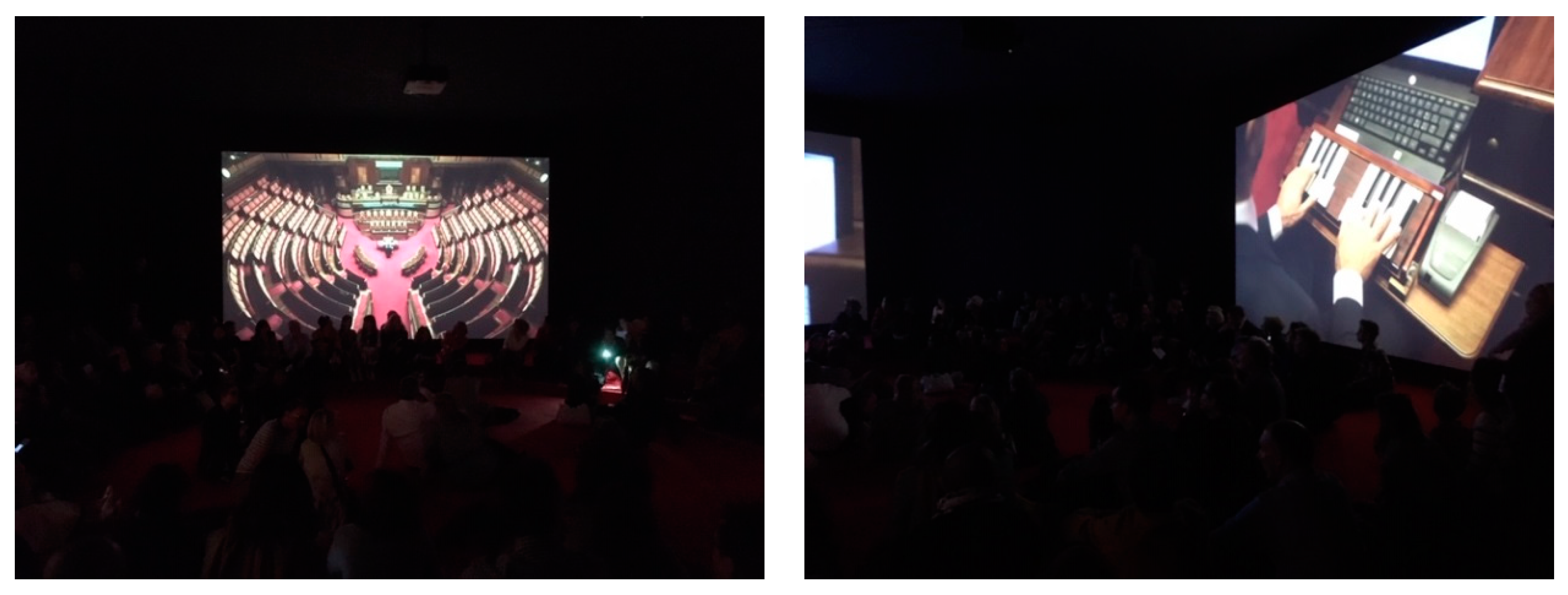

This is certainly within the scope of ‘Assembly’ by Angelica Mesiti, a three-channel video work installed in the Australian pavilion. Assembly takes as its starting point the poem ‘To Be Written in Another Tongue’ by David Malouf. Angelica Mesiti’s Venetian ‘assembly’ room, presents an Italian parliamentary stenographer transcribing Malouf’s text; scenes of typing, keyboard, printed text, signs and symbols, images of gesture around the theme of transliteration. ‘Assembly’ mimics page turning and other aspects of the book, as audiences are absorbed in watching multiple screens, testing our abilities to read images simultaneously. Mesiti expresses a desire for a high level of public interaction with the work which will tour Australia after the Biennale has ended (

Figure 6). On entering or leaving the installation, audience members are handed a printed booklet which can only be read in the light of day, and after the event. It is this small, printed and distributed folio that is the key to the videos’ content—text, diagram and notation—providing a physical context and interpretation which will remain with the audience for the duration.

4It may aspire to have the longevity of ‘Covering Letter’ (2012) at the Indian pavilion, where the artist Jitish Kallat has chosen to present the letter written by Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler in July 1939 imploring him to choose peace in anticipation of World War II. The type written words of the letter are projected into a curtain of descending mist; creating a cascade of words flowing through a shaft of light which the audience is directed to walk through, reading elements, as the ascending text dissipates all around. An occasion for open reading and self-reflection of a ‘... letter from the past destined to carry its message into our turbulent present, well beyond its delivery date and intended recipient.’

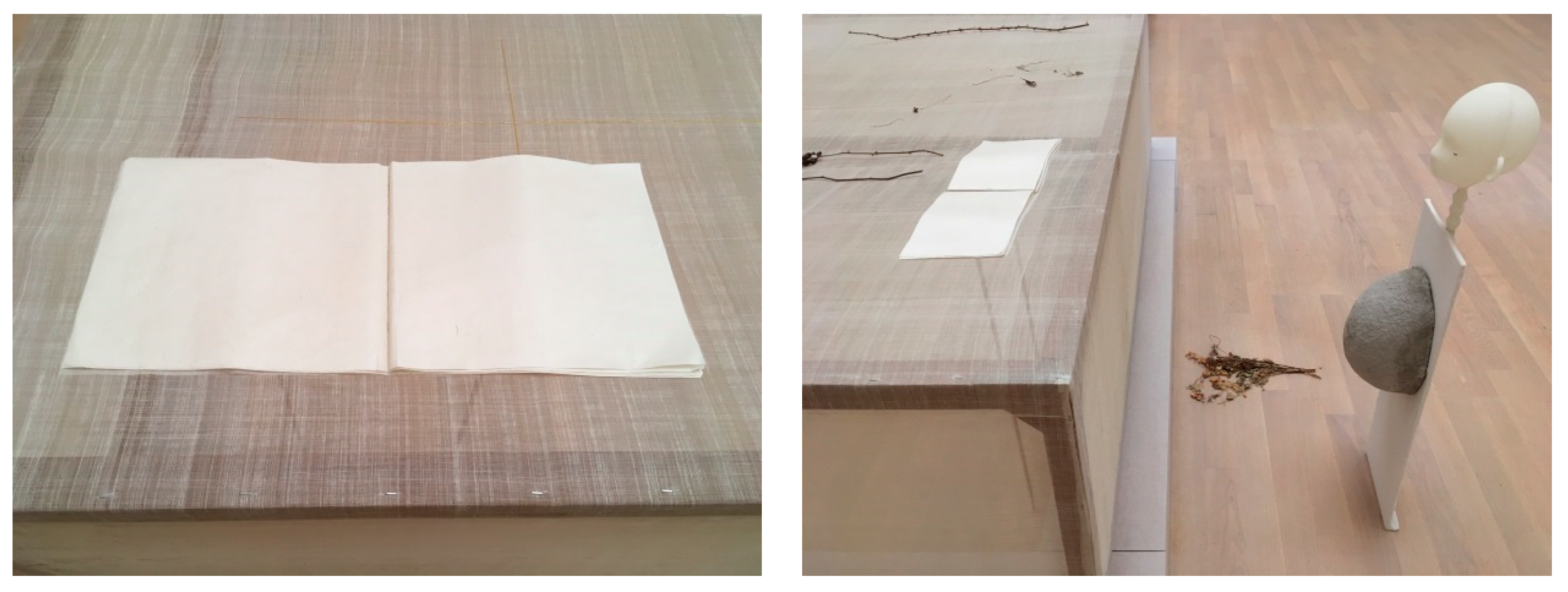

5Continuing with ‘conversations’ from the principal national participating pavilions, the artist Cathy Wilkes, presents her ‘creations’ which ‘occupy’ the six rooms of the UK pavilion. As objects are placed around the entire space, from floor skirting level, to hanging from the ceiling, only a small number of visitors are allowed at any one time. There are two sets of folded pages laid out upon an ephemeral table’ like structure, presented at reading level height but blank, empty of what we might consider visual content (

Figure 7).

Clive Phillpot identifies a distinction between ‘primarily visual books or books for looking at’ and ‘primarily verbal books or books for reading’:

What I’m getting at is that, if we accept that reading is ‘the decoding of writing’, the other activity we engage in with books by artists is looking. Thus, simplistically, we read artists’ books, but we look at artists’ bookworks. My ongoing preoccupation with the identification of bookworks is over the nature of those books that are artworks, designed to be looked at, and designed specifically page by page, verso by recto, opening by opening, to constitute an integrated flowing whole.

Wales in Venice features the work of Sean Edwards in ‘Undo things done’ described as ‘a poetic enquiry into place, politics, and class intertwined with personal histories’ and presented at Santa Maria Ausiliatrice, a former convent. The installation comprised largely autobiographical works exhibited with sensitivity to the traces that remain of the building’s past, presented through live performance, radio broadcast, handmade quilt, film work and digital print as well as an artist’s book. This book work, ‘Llanedeyrn’ (2019), is described as a ‘wordless art work’ placed casually in the room encouraging visitors to leaf through. Flicking through the pages, thus activating the work, the reader encounters black-and-white images of the housing estate where Sean Edwards grew up. The book depicts the estate in daytime, as deserted, empty of life; a quietness which connects back to the atmosphere of the exhibition space and installation (

Figure 8).

The reader can peruse an artist’s book with the almost certain assurance that he or she is responding to the work in a state which completely corresponds with the intention of the artist (

Phillpot 2013, p. 56).

The entrance hall of the Romanian pavilion features ‘White Library—Memories of Absence’, by artist Belu-Simion Fãinaru (

Figure 9). More white books, blank pages on wooden bookshelves scaled to fit in the alcove, part of a site specific installation which takes the form of an uninhabited domestic interior. The interpretation material suggests that ‘Belongs Nowhere and to Another Time (part 1)’ places the viewer in an ‘

in-between space of a non-specific and transnational culture’, touching on issues of displacement, migration and the nomadic.

The same theme is explored in ‘Written by Water’ mixed media installation created by Marco Godinho for the Luxembourg Pavilion. This piece is composed of two back to back videos of the artist walking through the landscape, through cemeteries and along the seashore, whilst reading from and tearing the pages of a French translation of Homer’s ‘

Belles-lettres’, the remainder of the book, its cover and tattered spine, visible through a narrow slit in the gallery wall. An adjacent gallery tells a narrative of refugees moving from South to North across the Mediterranean, most of whom have never encountered the sea, its enormity expressed in a third video, this time of exercise books that have been bathed in sea water, battered by the waves, presented on a slope, the roof of the pavilion, appearing to have been washed up like bodies, clothing or stories on the shore and left out to dry (

Figure 10). In addition there is a text project which takes literally the idea of ‘conversations’, as explicitly talked about by

Rugoff (

2019)—a new text every day, for 100 days, printed onto a t-shirt and worn by the invigilator present at the exhibition who actively attempts to engage with the visiting public, to elicit reaction and dialogue relating to themes within the artwork.

A ‘List of lists’, an index of things that have disappeared, or that are absent, withdrawn or otherwise no longer in existence, flows on paper waves filling the floor of the library space in Post hoc (after this) by Dane Mitchell and hosted in the Palazzina Canonica, former headquarters of the National Research Council for Marine Sciences (CNR-ISMAR), the New Zealand Pavilion (

Figure 11). The only sound in the library, which for this occasion has been emptied of its significant collection of books, manuscripts and maps of Venice and the lagoon dating back to the 16th century, is that of a printer placed on a raised stand in the centre of the floor. Over the duration of the exhibition, a list of titles are being churned out, item after item, the enormity of which, is evident by the accumulation of paper which becomes almost impossible to read. Words can be glimpsed through waves of paper folds: ‘extinct’, ‘banned’, ‘lost’, ‘past’, ‘former’, ‘obsolete’, ‘discontinued’; language which refers to things of another time, censored, removed, hidden. The reader encounters this list in a place dedicated to the transmission of knowledge, the empty library shelves underlining the sense of loss, abandoning the viewer to determine their own relationship to an invisible past. Further to this, a series of electronic transmission posts in the form of trees relay the growing list in sync with the printer at specific locations around Venice: hospital, university, remembrance garden and the Arsenale, places all chosen for their relationship to ideas of invisibility, transformation and loss.

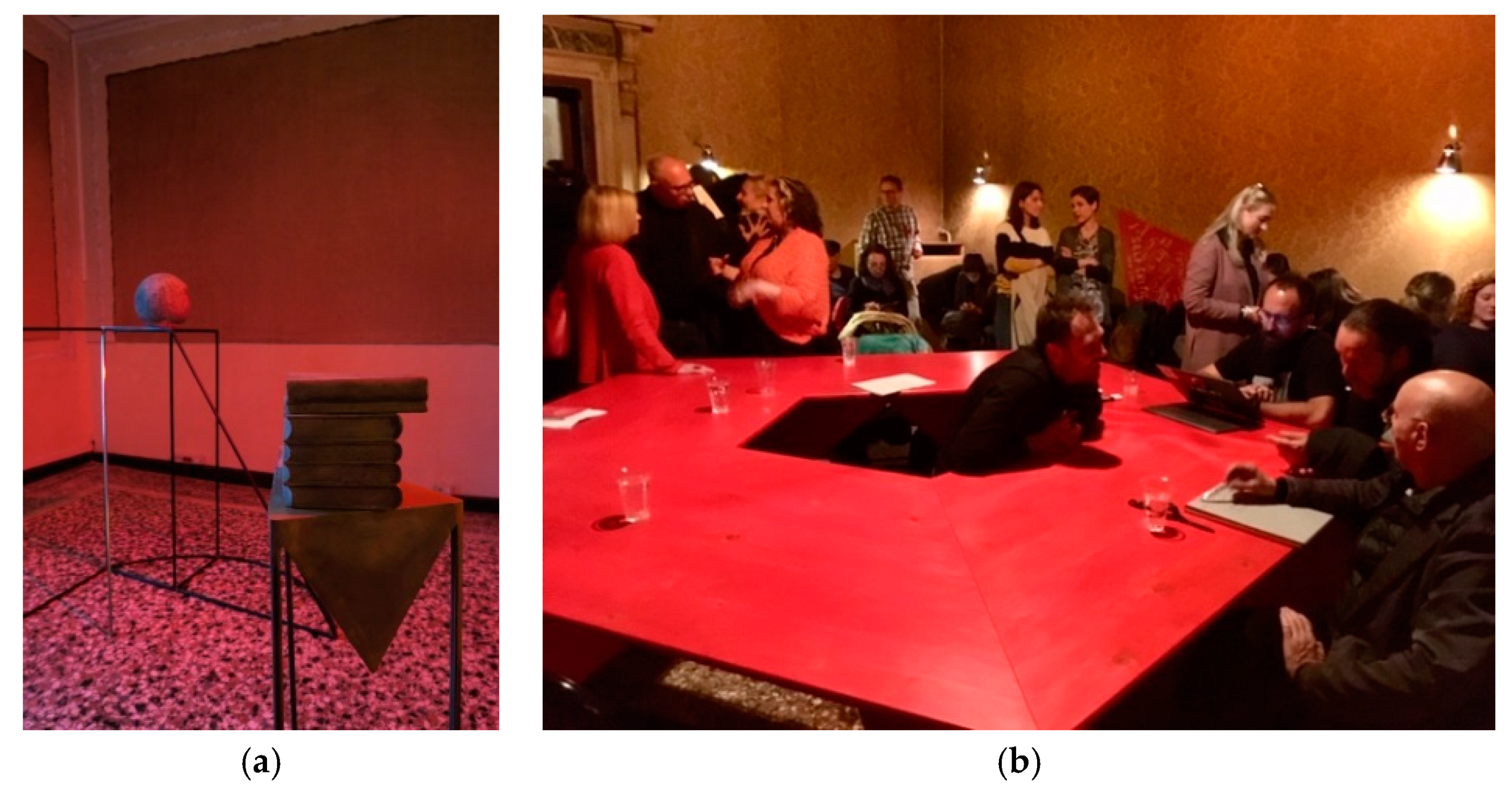

The aspiration that artistic action can promote change is intrinsic also to the dialogue with Palazzo Rota Ivancich, the Republic of North Macedonia Pavilion, an installation and performance entitled ‘Subversion to Red’ by Nada Prlja. The principal installation, ‘The Collection: She does What She wants untitled II’, references significant artworks from the former Yugoslavia and MOCA Museum of Contemporary Art Skopje; sculptural works, dynamic compositions on geometric shaped metal plinths, which include a series of book forms taken from historical volumes and cast in concrete (

Figure 12).

Nada Prlja recounts memories, connections with other artists and relationship to materials, as key to leftist thought and the notion of solidarity that underpin the work, the theoretical and visual approach to which can be found in a series of essays in the accompanying soft cover booklet, referred to as an Artbook, one of the many publications accessible at the Book Pavilion (

Figure 13).

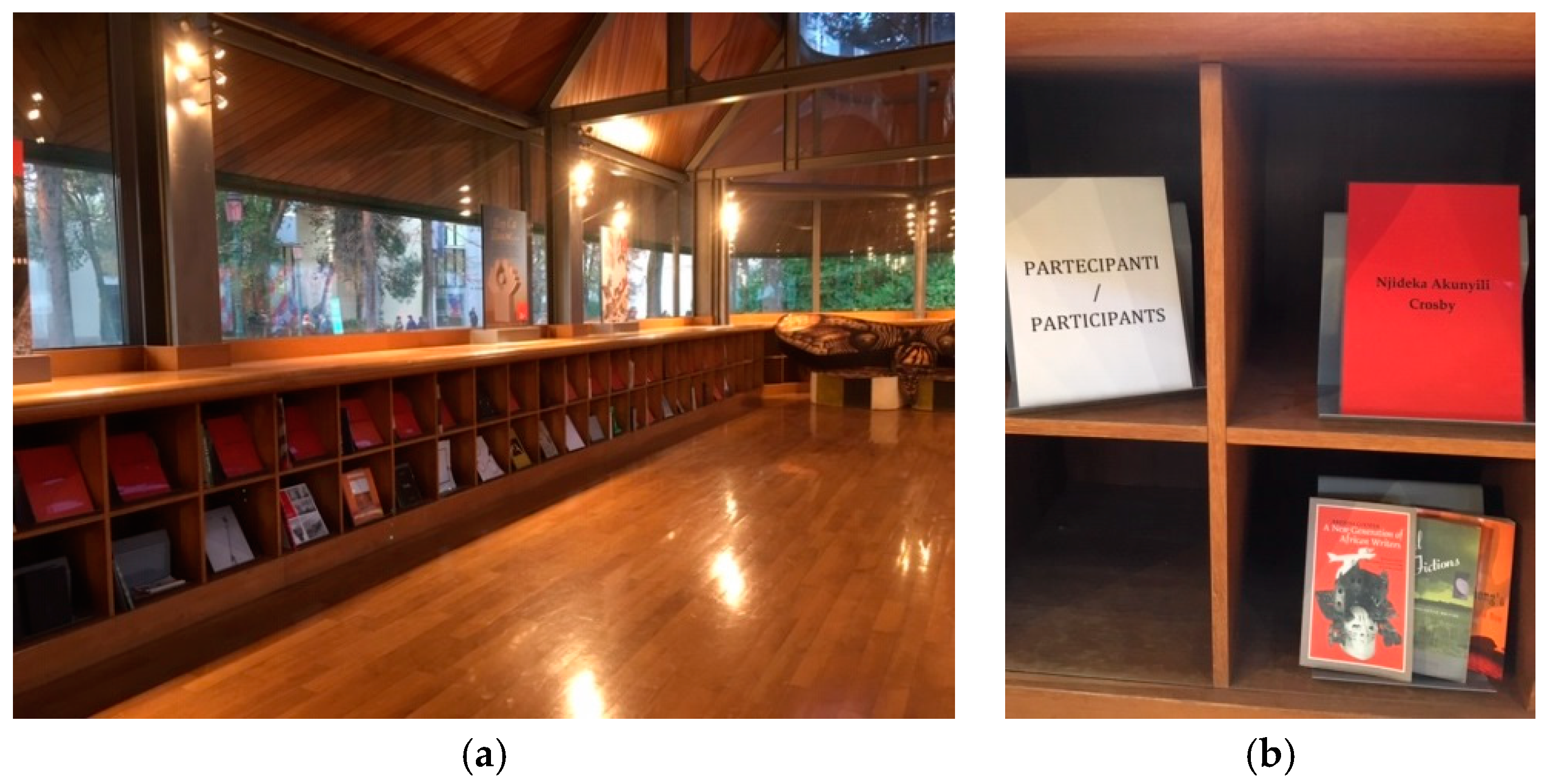

Designed by British architect James Stirling, the ‘Book Pavilion’ is located within the Giardini area of the Biennale alongside the independent International cultural offerings. When it was built in 1991, the building was surrounded by trees, now the 30metre long glass and metal structure stands on a sparse area of ground, isolated and outward looking, as distinct from the other pavilions. The rounded ends of the building and the lack of doors create a feeling of security within the space. Further nautical references are found, in the purpose designed, deep set lacquered wood bookshelf which runs the length of the room, for the display of books donated by participating artists and architects in the Biennale. At the invitation of the appointed curator, all kinds of publications which may range from Pavilion catalogues to selected titles for reading by participating artists, are presented here as archive, arranged in alphabetical order with their country references (

Figure 14).

Contributions to the ‘Book Pavilion’ are subsequently transferred to the Biennale Library which since 2009 has been an integral part of the Central Pavilion at Giardini. It is worth noting that The Biennale Library is open all year round irrespective of ongoing Biennales: architecture, visual arts, cinema, dance, photography, music, or theatre. It is now one of the main libraries of contemporary art in Italy, with more than 153,000 volumes and 3000 periodicals; preserving all catalogues and bibliographic material relating to Biennale activities.

6The opening week of the Biennale particularly, holds a frenzied atmosphere with the multitude of events and exhibition openings to attract press and media, collectors and curators in particular. There is a drive within the cultural sector to maximize opportunities for visitors to interact at this important occasion, to meet and exchange. This generates a deluge of all nature of printed matter including books, catalogues, booklets, cards, leaflets, masks, badges, stickers, bags and rubber stamps around the production of exhibitions with some evidence of a conscious move towards print-free communication with USB keys being offered or Q codes available for PR information.

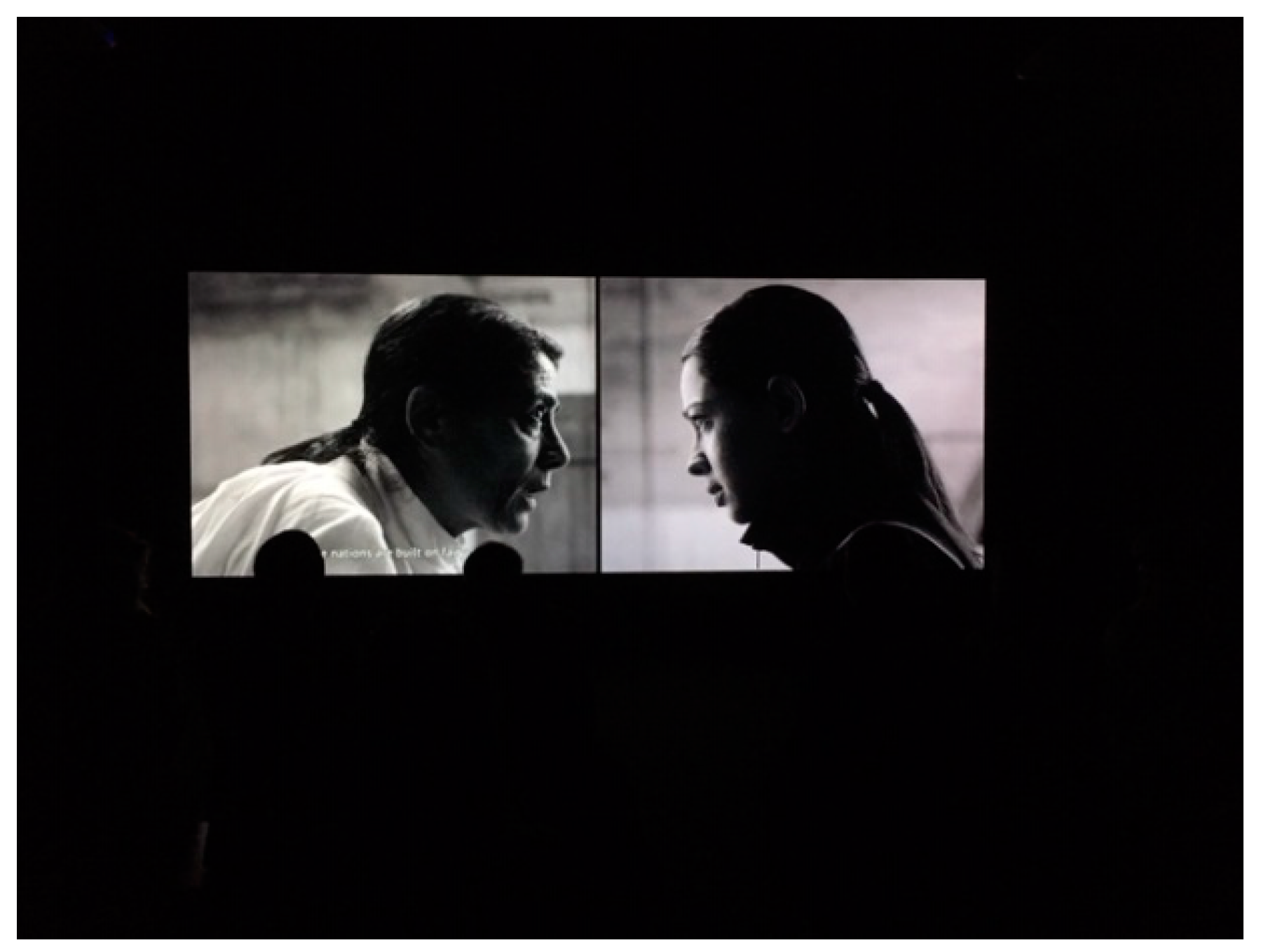

Paradoxically, the Japanese Pavilion produced an elaborate multi-layered publication for Cosmo Eggs, a coexistence through converging resonances and dissonances, collaboration between an artist, a composer an anthropologist and an architect together trying to imagine a possible ecological symbiosis between human and non-human. A spiral-bound A4 book in both English and Japanese uses a variety of papers sizes and plastic sleeves, a representation of the project and its research and development in the form of a facsimile: exercise books, photographs, musical scores, statistics tables, a music fingering chart, a calendar detailing the production process, and a large fold-out map—more than mere documentation of this complex project, the resulting publication can be located somewhere in Phillpot’s ‘verbi-visual’ strand providing a rich resource of material, scraps and textures for the viewer/reader to engage with, challenging their ‘existing habits of thought’ as how we might read an image or view a text. This rupture in structure and/or fragmentation in the information that we receive is also played out in Heirloom (Danish Pavilion), the accompanying booklet using divided page and image layouts to re-present the split screen device used in ‘In Vitro’, a film that features two women in a world that has gone underground after an ecological disaster.

The parallel stories are presented alternating from one screen to another. The book’s designer, Alexis Mark, worked closely with the artist Larissa Sansour and curator Nat Muller devising ways to accentuate this to and fro structure embellished through the formalism of black and white photography in print (

Figure 15).

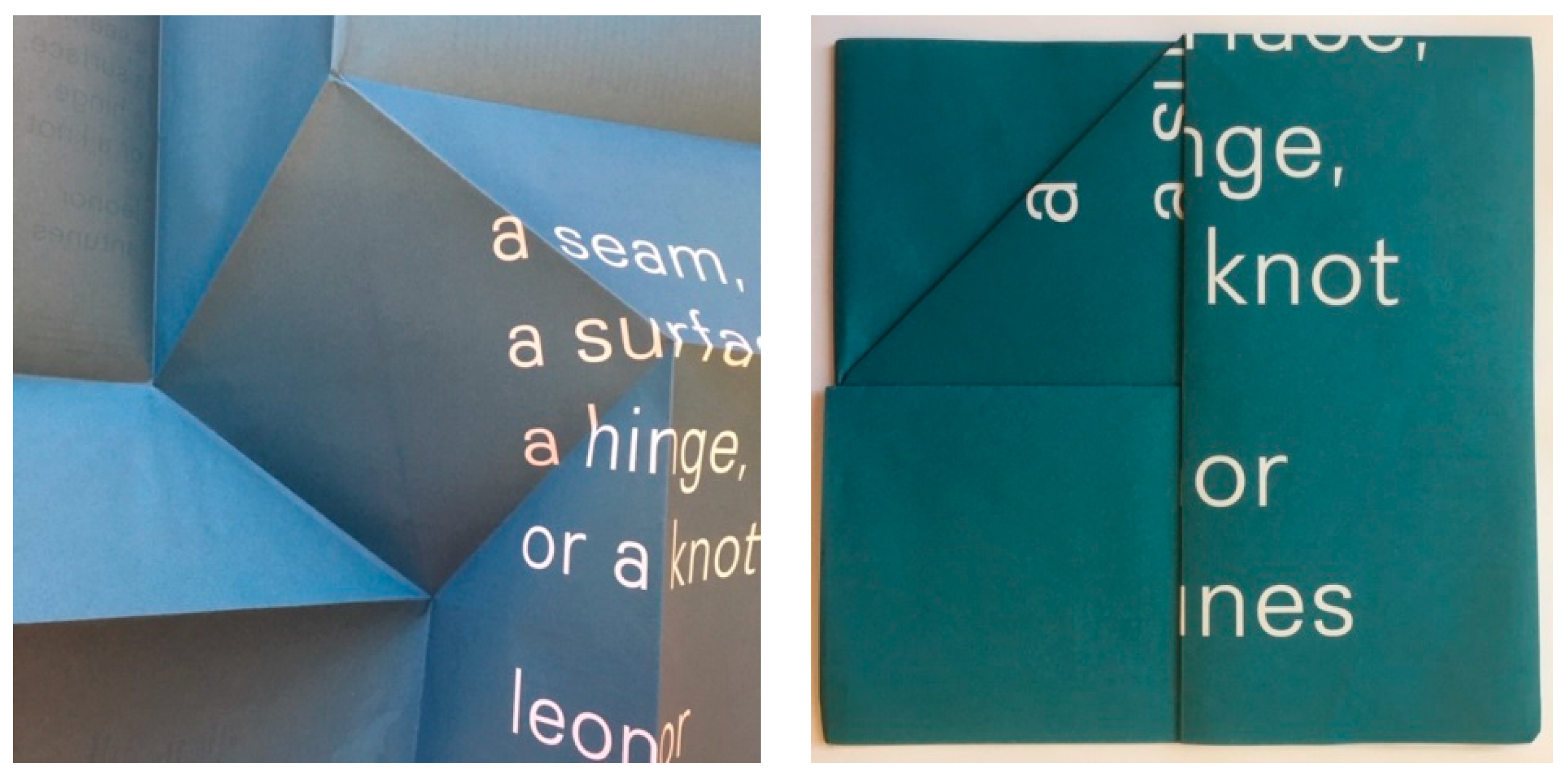

In contrast, the Portuguese Pavilion representation is publicized by a single sheet folded paper leaflet (

Figure 16).

Memorable for its marked simplicity in announcing the exhibition, ‘a seam, a surface, a hinge, or a knot’, Leonor Antunes’s, site specific, large scale abstract sculpture, responding to the location of Palazzo Giustinian Lolin.

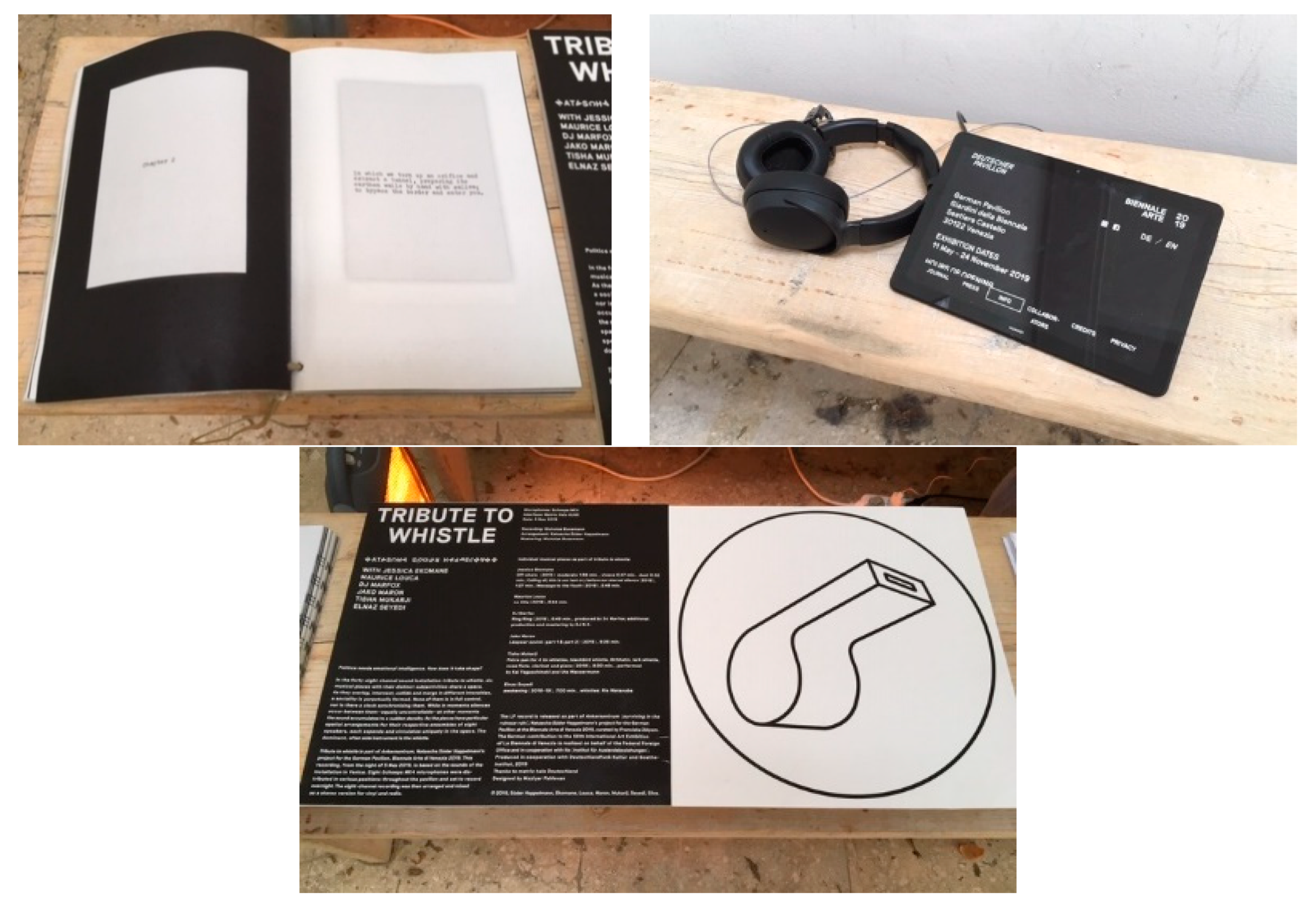

Ankersentrum (surviving in the ruinous ruin) is large scale installation which fills the German Pavilion, the structure composed of sculptural and sonic elements, reflected in the delivery of available resource materials in the form of a vinyl LP record, scroll through digital presentation and a publication designed to enhance and expand on the experience (

Figure 17). Also entitled ‘Ankersentrum’, the publication is importantly described as ‘an essential part of the artistic contribution’ to the pavilion. It contains poems, drawings, photographs and texts by Natasha Süder Happelmann and other artists addressing the main concepts of containment and isolation, graphically presented through plays on the reading of image and text by designer Maziyar Pahlevan. It is published by Archive Books, founded in Berlin 2009, whose publishing manifesto reads as ‘an ecosystem where authors, translators and editors work to build lines of communication with diverse publics.’

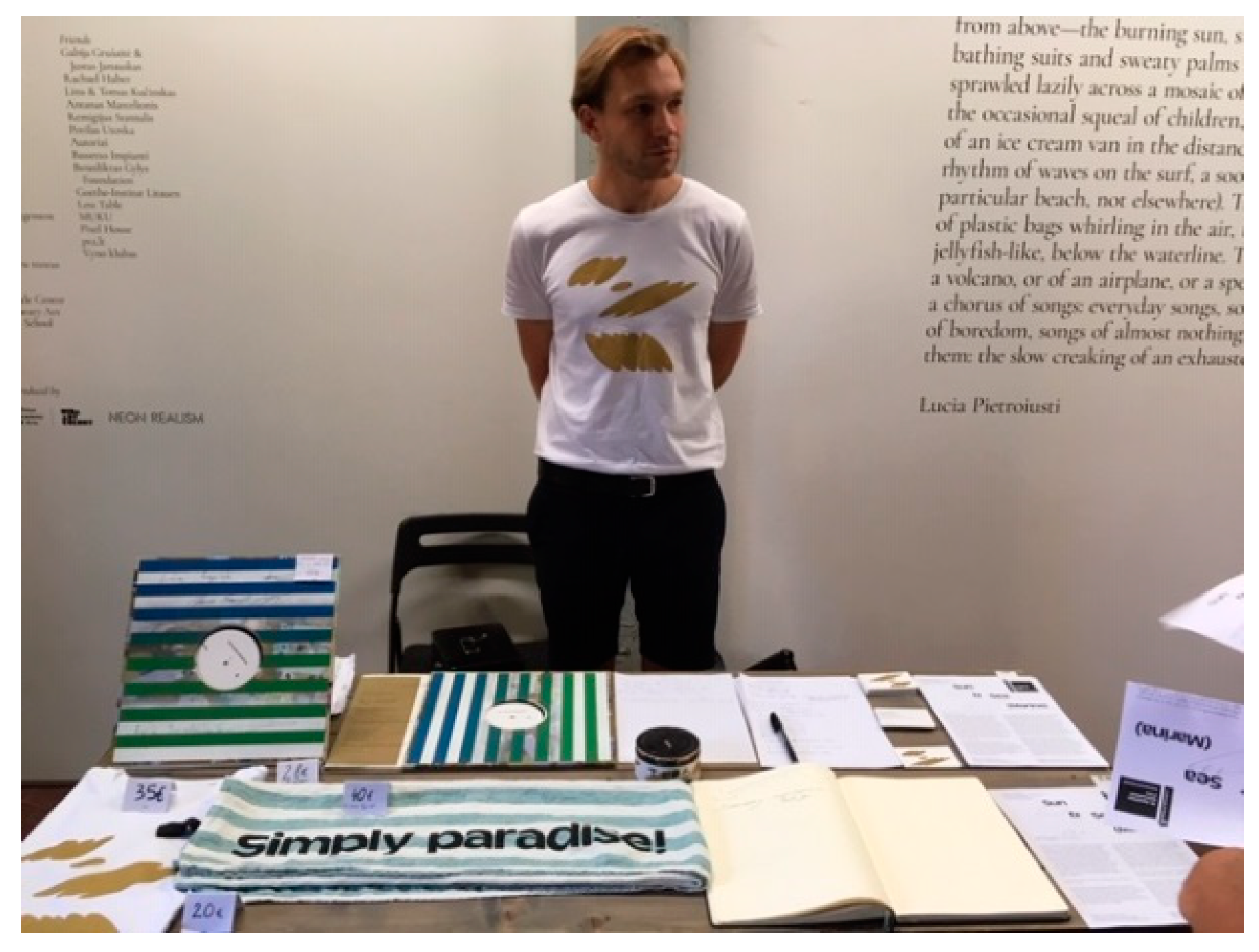

7‘Sun & Sea (Marina)’ by Lina Lapelyte, Vaiva Grainyte and Rugile Barzdziukaite (Lithuanian Pavilion) won the Golden Lion award for best National participation in the 2019 Biennale, a performance work (opera), 70 min long which takes place on an artificial beach crowded with people. The opera is sung in English by performers and volunteers, while being watched from above by a ‘chorus’ of people. The opera’s full libretto is published in a special-edition vinyl LP catalogue accompanied by texts on the mythology of the sea by curator Lucia Pietroiusti; although they have chosen vinyl here, a Q code is available inside for access to a digital player version (

Figure 18). The vinyl catalogue, designed by Åbäke, was conceived partially as an opportunity for local collaboration, screen-printed in Venice by inmates of the male prison of Santa Maria Maggiore. There is an increasing trend which sees artists from the Biennale wanting to interact with Venetian organisations, a consciousness that the Biennale has roots in this particular place and that there is also life taking place alongside, which is not ‘outside’ of art. Since the 2017 Biennale, the artist Mark Bradford has been collaborating with Rio Tera di Pensieri cooperative for training in the women’s prison, a number of diverse publications resulting from this relationship.

8 3. Book Biennale

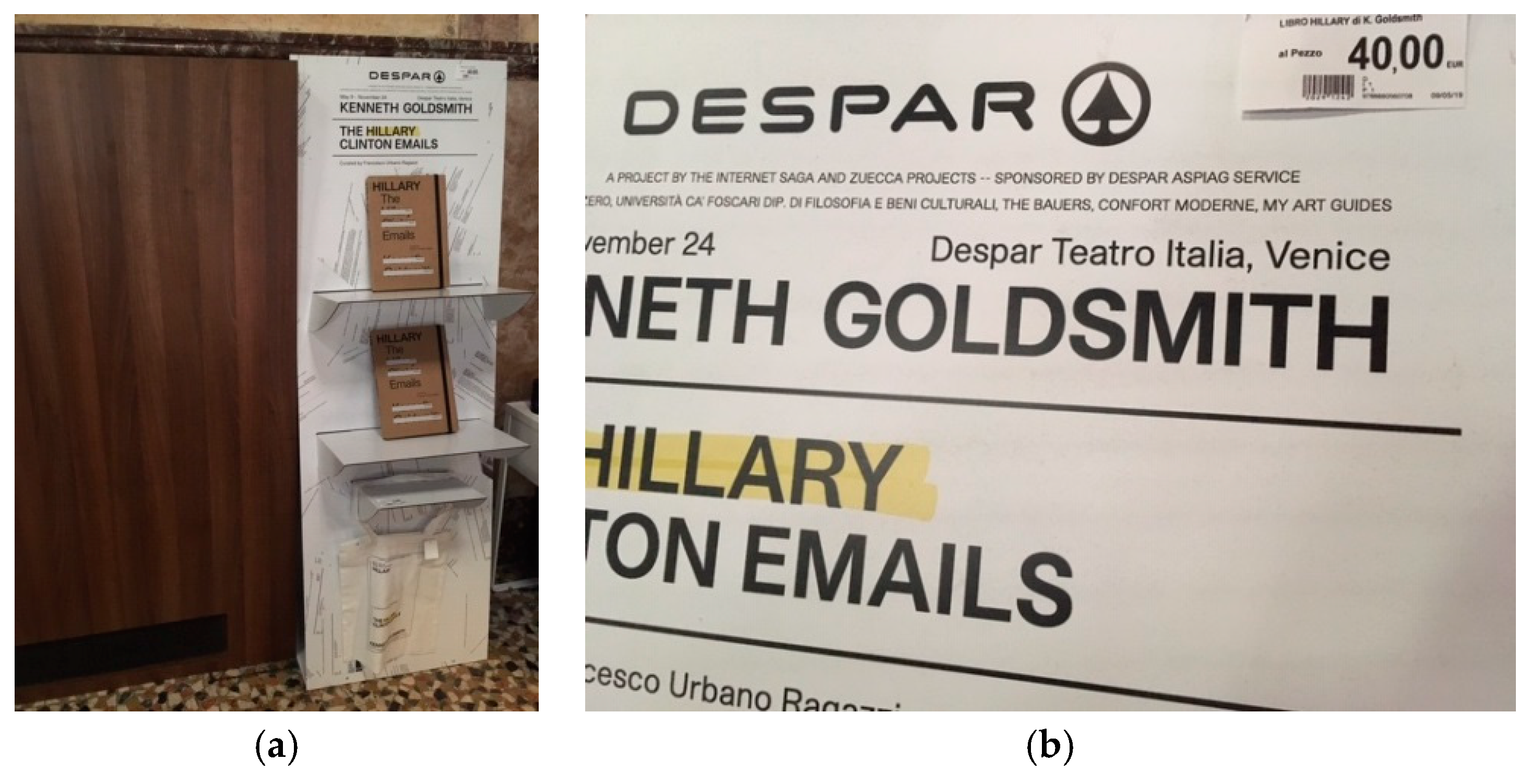

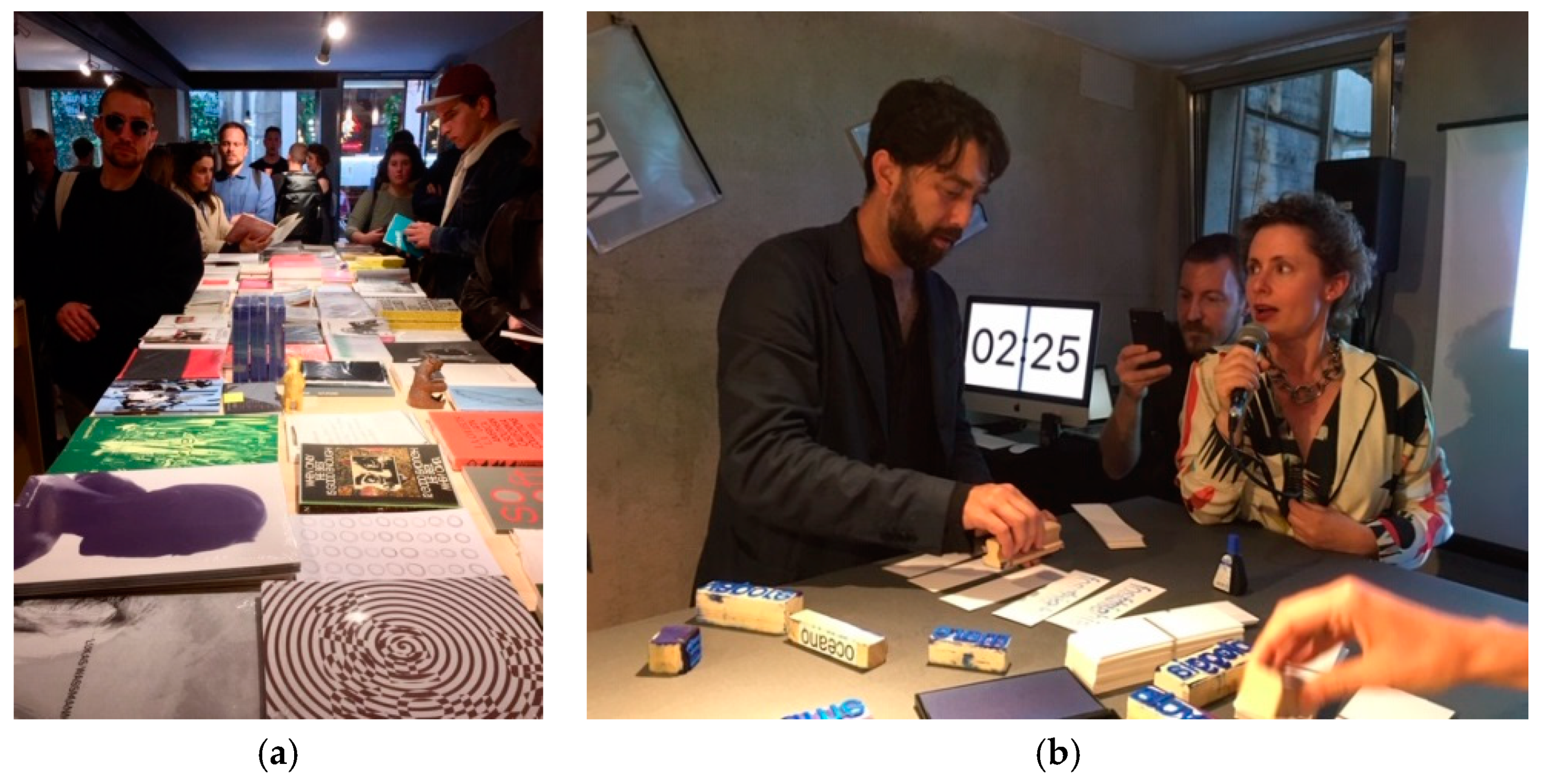

Not to be confused with the previously discussed Book Pavilion, the 58th edition saw the appearance of ‘Book Biennale’. The brainchild of ‘b-r-u-n-o’, in collaboration with Giovanna Silva, Book Biennale was born out of a desire to dialogue with the International Art Biennale, to give a presence to the book, capitalising on a particular moment in the cultural calendar.

Book Biennale is a question we either pose or try to answer, a crisp blank page, an interview, a vaporetto ride in the heatwave, a bookmark, a phone number you might want to call, a train ticket, a friend of a friend who has heard about it, a bear, a workshop, an artists’ book, a way to enrich one’s biennale experience, or to escape from it, a bookshop that you have probably spent time in, or have peered into while passing by, a tool to look at what it means or does not mean to be a publisher today.

10The ‘b-r-u-n-o’, project was initiated in 2013, by Giacomo Covacich and Andrea Codolo, simply conceived as a journey with the book as a companion. Venice was chosen as a location for the graphic design studio and bookshop because of its links to the history of the book and because of the unprecedented concentration of artistic and cultural activity at the level of production of print and related materials. ‘Open Book Launch’ programmed 10 short interventions, dialogues, proposed by artists, curators and graphic designers involved directly in the participating national pavilions, with contributions from the Danish, Italian, Lithuanian, and Luxembourg pavilions and, significantly, Mousse Publishing who are responsible for extensive number of publications that include the Nordic, Iraqi, Kosovo, Korean, New Zealand, Maltese, Mexican, Albanian and Chilean Pavilions. The presentations covered the relationships involved in catalogue design and delivery, development and production as well as examining distinctions and overlaps between catalogues and artists’ books. Most publications were printed by ‘Grafiche Veneziane’, the principal offset printer in Venice, the short and numerous deadlines, making rapport between, graphic designer publisher and printer even more important. By contrast, the evening culminated with David Horovitz’s 10 min performance, ‘Bookmark’, filmed making an edition of bookmarks, printed and distributed there and then (

Figure 21).

The Book Biennale project continues with ‘Flicks books’, a series of film projections taking place over three evenings in the bookshop, shorts/films that contain books or where the narration of the film takes the book as starting point; each presentation thought of as a progressive ‘reading’. Book Biennale also includes a podcast and an online presence using Instagram called ‘Index Book’, documenting the indexes and structural elements of the biennale publications. ‘b-r-u-n-o’ are committed to continue with Book Biennale, through a fluid and open approach in the use of open space; hoping to add to the variety of possible platforms including those yet to be discovered or invented.

Whilst there is currently no annual artists’ book fair in Venice, previous one-off events such as The Book Affair, 2013 and Scuola Internazionale di Grafica in 2011 aroused momentary interest, but the Book Biennale does seem to offer promise of a new and alternative approach.

4. Venice Bound

Artists, writers, calligraphers, printers, bookbinders and graphic designers can all be found in the city, operating at the level of idea, production and distribution, which makes Venice a special location for the book and by extension the artists’ book. The occasion of the Biennale has become an engine for production of new work and all kinds of publishing, a driving force that is nurtured by ‘historical’ and ‘physical’ conditions. The Marciana Library is the cornerstone of the history of the book. Constructed in 1537, it now holds about 1,000,000 items. Venice is also the place where Aldus Manutius founded the Aldine Press; his small portable books (enchiridia) revolutionised personal reading and are considered to be the predecessor of the modern paperback.

11The painter and poet, Emilio Isgrὸ made his first erasures of books in 1964, in Venice, this the reference for his retrospective at Fondazione Cini San Giorgio, curated by Germano Celant. The installation has been designed to give the visitor the sensation of entering a large book. Isgrὸ writes:

The theme I addressed for this exhibition in Venice, the city where I made the first erasures in 1964, inevitably focuses on language. That’s why I thought I had to resort to the biblical tradition as interpreted in Moby Dick, Melville’s wonderful novel. Visitors to the exhibition will enter Melville’s erased text—‘the belly of the whale’, that is also, the belly of media language that smothers with noise its real, desperate silence.

12

Text explodes onto the wall, words printed as image on wallpaper. Books are laid open, but displayed in transparent cases, so unavailable to leaf through. However, a digital screen shows scrolling book pages, a different way of viewing/reading his books with text erasures. Invention and intervention in the design of exhibition layout and the use of new technology seeks to impact on the depth of experience.

At the Punta della Dogana, ‘Luogo e Segni’, curated by Martin Bethenod, Director of Palazzo Grassi and Mouna Mekouar, features a number of book works. Taking its title from a painting by Carol Rama (1974), ‘Luogo e Segni’ features 100 works from the Pinault Collection. Dhikr (Incantation) is the work of Etel Adnan (1978), an artist’s book, pastel, watercolour and ink on Japanese paper, displayed in a glass case and constructed to show the leporello fully opened, beautifully positioned across the centre of the space. Writing is mixed with drawing and drawing is mixed up with the writing. “To write is to draw,” says the poet. Adnan’s work stands at the point of intersection between image and text. The line, the sign (writing, in other words) runs through her work; ideas at heart of the exhibition which also features work by Anri Sala in collaboration with Ari Benjamin Meyers, musician and composer. The Breathing Line (2012), three leporello books presented on custom-made shelves, transcribes the relation between time and space. Each corresponds to a time (a tempo): the ‘living time’, that of breath and breathing, the ‘musical time’ and the ‘counted and measured tempo’ of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Pathétique’.

There is no doubt here that the book in its many creative forms is given parity with other types of work in the collection.

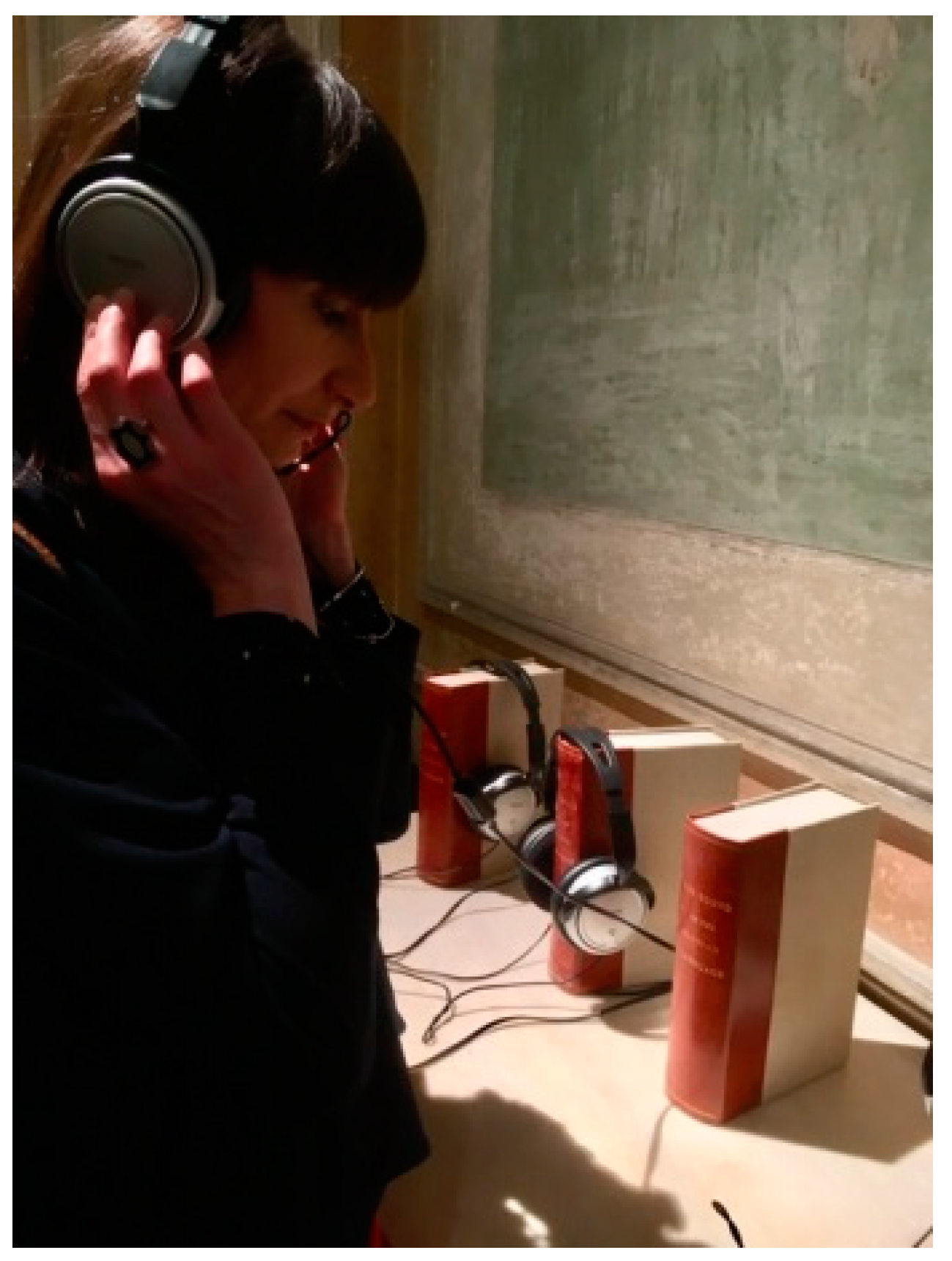

13The Querini Stampalia Foundation is another fixed point of reference in Venice. Maria Teresa Sartori’s work ‘The Sound of Language’ which is part of the museum’s collection is included in the current exhibition, ‘Dire il tempo’ (Telling the time). The 11 audio books contain sound recordings of poems, literary extracts in different languages which have been reworked, leaving accent and length of words, rhymes and metre unaltered making it possible to listen to the sound of each individual language in terms of ‘pure sound’, freed from its original meaning (

Figure 22). The Querini is celebrating 150 years of what it refers to as ‘conserving the future’. Curated by Chiara Bertola, the exhibition integrates the use of its library, house, museum and contemporary galleries.

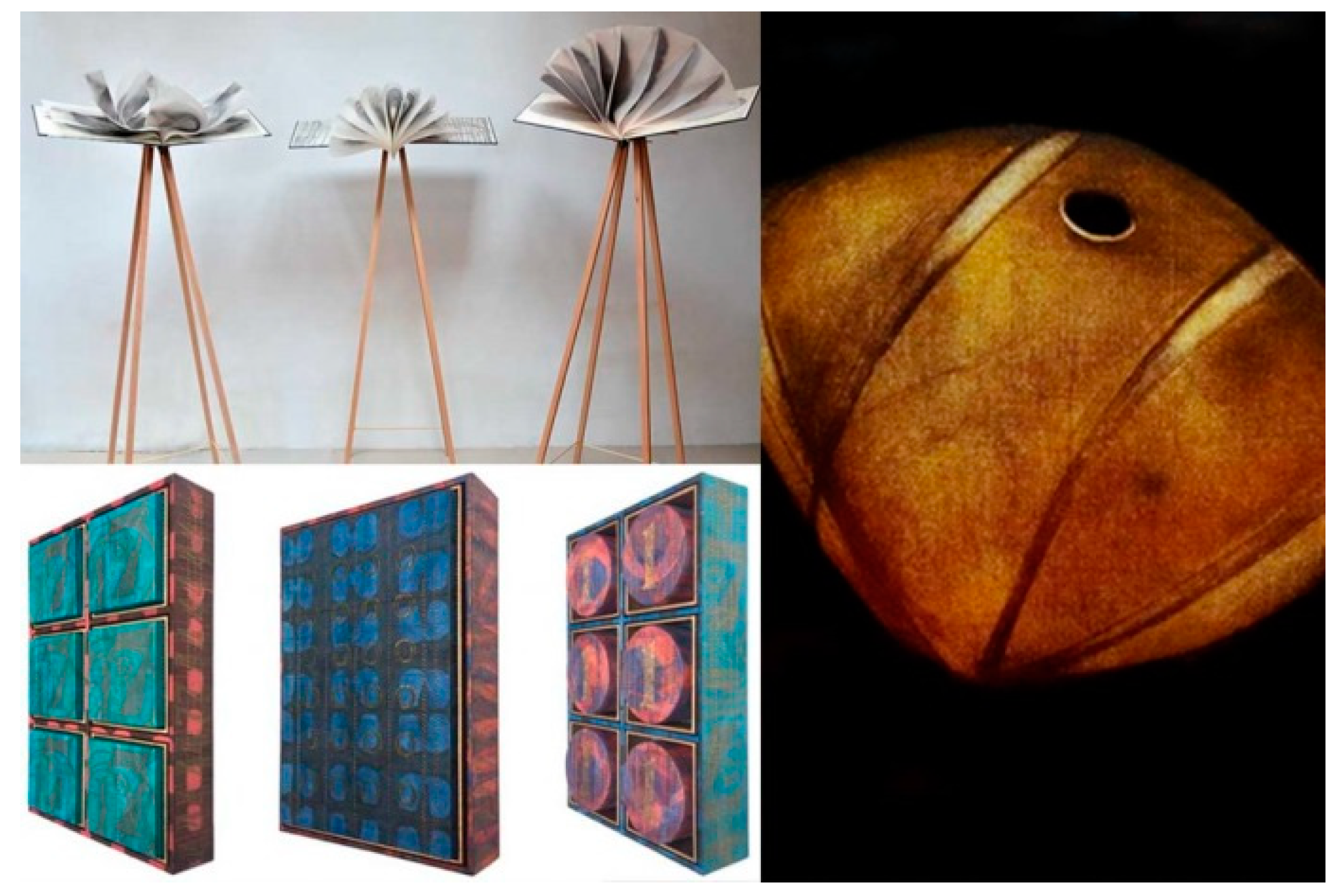

14The Scuola Internazionale di Grafica has had a presence in Venice since the 1960s over which time it has amassed a collection of over 500 artists’ books, many of which were produced by artists participating in the artist in residence programme coordinated by Artistic director Matilde Dolcetti, in respect of “

A little art form which has great breath, hidden in its discreet appearance”. Artists’ book courses, first established in the 1960s, are now held by invited international artists, supported by didactic use of the collection and by an events and exhibitions programme and focused around the SG gallery (

Figure 23).

15