An Aesthetic Pattern of Nonbelonging—Immigration and Identity in Contemporary Israeli Art

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Methodology and Theoretical Framework

1.2. Defining a Local Migratory Pattern and Its Context in the Historiography of Israeli Art

Collage—in denying semblances of order and purist wholeness, in its hybridism and artificialness, in its confronting pieces of reality with fiction, what we know with what we see—presents reality as a simultaneous existence, reciprocal in the affinities of complementary and conflicting powers. Meaning and identity are constituted within it through the examination of their mutual relationships. In this sense—and in the cultural-social context—the very collagist construction may be a statement.

I think that during the 1990s, things gradually started to change. Artists began using collages as a means of talking about personal experiences, that is, not to make them universal but to let them operate as a particular narrative.

1.3. Moshe Gershuni as a Precedent and the Negation of Diaspora

The “melting pot” policy, a dominant national strategy that the State employed during the first years of its existence in order to cope with the mass immigration between 1948 and 1951, institutionalized and reinforced this stance. Driven by the perception that cultural diversity poses a threat to the construction of a collective identity, this policy was designed to unite immigrants from all over the world under a new cohesive national identity. In Anita Shapira’s words, this meant:Zionism was constituted ex negativo, relying on the two postulates “negation of Diaspora” and the birth of the “new Jew”. This is why everything Jewish, reminiscent of “Diaspora”, was pejoratively perceived and fought to be erased.

The local socio-cultural mentality of negating former cultural identities clashes with the fact that many Israelis have only arrived in the country relatively recently. Despite significant cultural changes in the postmodern mindset, which undermines the belief in national ideology—sometimes locally termed post-Zionism—the formative Zionist ethos of a new monolithic Israeli identity still prevails. Although the change in global cultural discourse in recent decades has significantly influenced local mentality with regard to acknowledging differences and accepting diversity, the fact that Israeli history is so young acts as a counterbalance.[…] bringing all the Jewish Diaspora under one cultural roof and having them all adopt the principle of progress, a nonreligious national worldview, and Hebrew language and culture. All Jews from the Diasporas were called upon to shed the characteristics of their former culture and unite under the banner of the state and its symbols.

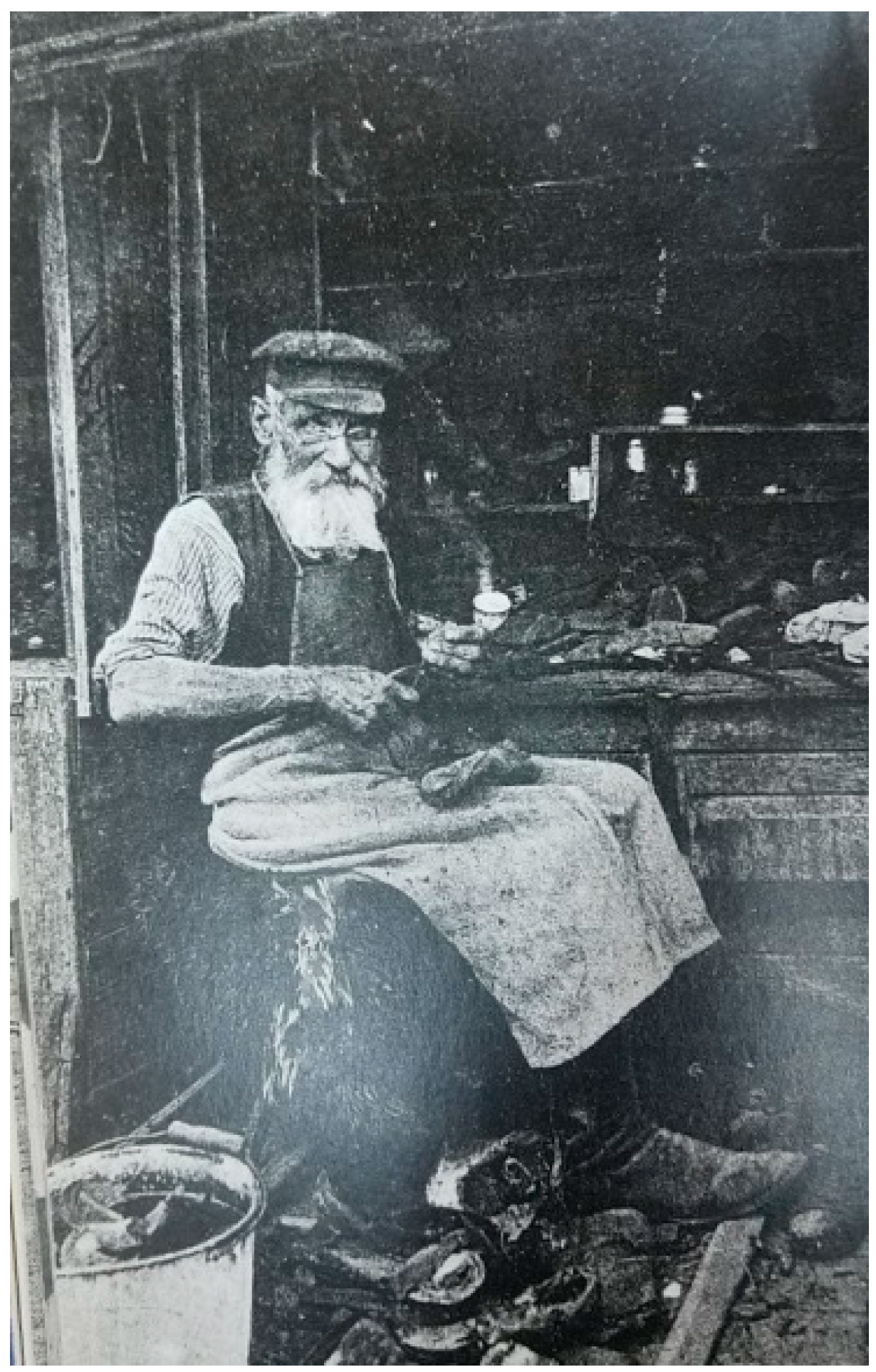

1.4. David Wakstein—Sonia, Salma, and the Shoemaker

Clearly, Wakstein’s experience of failed assimilation and cultural clashes was especially strong on a kibbutz during the 1960s. The discrepancy lying at the core of the estrangement, which this work conveys, derives not only from the screened double image, but also from the decision to frame the canvas with local mosaic stones. This unusual frame alludes both to the concrete aspects of the new homeland and to its ancient cultural history in stark contrast to the diasporic cobbler. It is an intimate work, conveying an irreconcilable identity in which the diasporic parental presence thwarts his attempts to fit in.As I was adapting to this particular social sensitivity, I felt that my father wasn’t part of the kibbutz’s “clique”. He was a simple shoemaker, perceived as a diasporic outsider. His work accentuated his foreignness in the social humanscape of the kibbutz. I was ashamed in him for not being a tractor or jeep driver, or planting cotton.

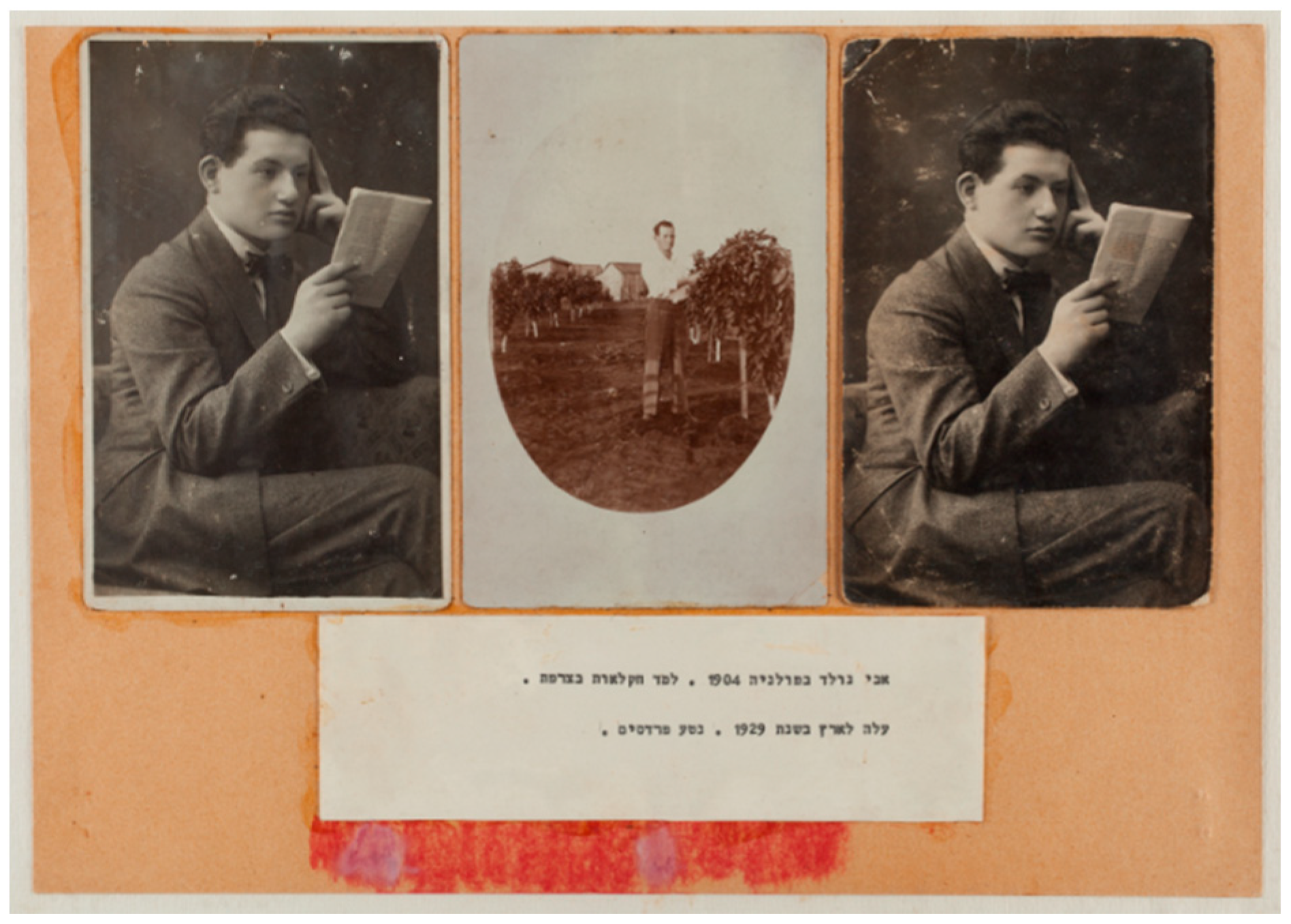

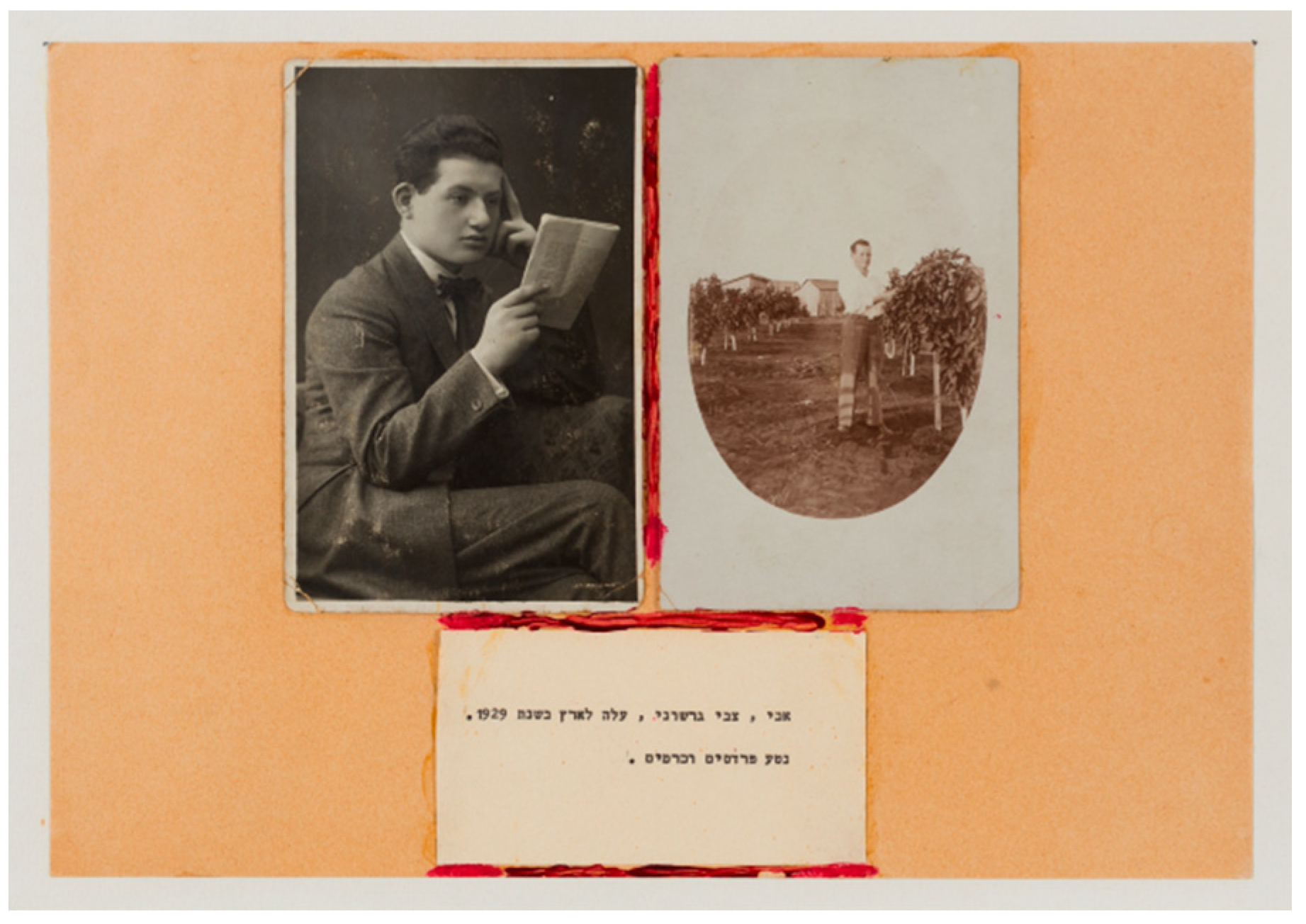

1.5. Haim Maor—Letste Nayes

“In 1949 I arrived in Israel with a single wooden suitcase”.

I never saw it. After his passing I cleared the house. In a distant corner in the attic the lost suitcase was found. His name, David Moshkovitz, was written on one of its sides in blue ink, in the hesitant handwriting of a new immigrant. I opened it. It was filled with old Yiddish newspapers.

18 December 1951—“Letste Nayes: catastrophale lage in di ma’abarot” (“Latest News: Catastrophic Situation in the Transit Camps”). Fifty years later, the catastrophes and transit camps are still packed in his suitcase.

Thus, the artist visually translates wandering—perceived as a cultural mindset—into a strikingly stereotypical representation of Jewish identity. Rather than referring to the land, a prime feature in the construction of the new Hebrew identity, this representation is in keeping with the perception of Jews as “people of the book” (עם הספר). Maor not only detaches these portraits from the background and from each other, while preserving an estranged diasporic language, but his use of a black silhouette creates a negative representation in which he outlines the figures in a way that denotes absence rather than presence. He underscores this impression by leaving the entire work devoid of color. In harnessing this visual language, which he intertwined with Yiddish, Maor incorporates his traumatic familial story into his own self-representation. He has recently elaborated on this notion by which his familial identity is imprinted on his sense of self:My father was a skilled wandering Jew: his possessions were always ready […].

My works do not spring ex nihilo. They do not begin with a blank white canvas, just as I, born in this country, was not born of the sea, nor did I romp on golden sands. From the moment I was born it was impressed upon me that I was a substitute, a continuation of members of the family killed in the extermination camp. I am supposed to perpetuate and memorialize them and the Jewish heritage of the Moshkowitzes from Plonsk and the Rutters from Lanzut, in Poland. This sensation filtered down into my artwork […].

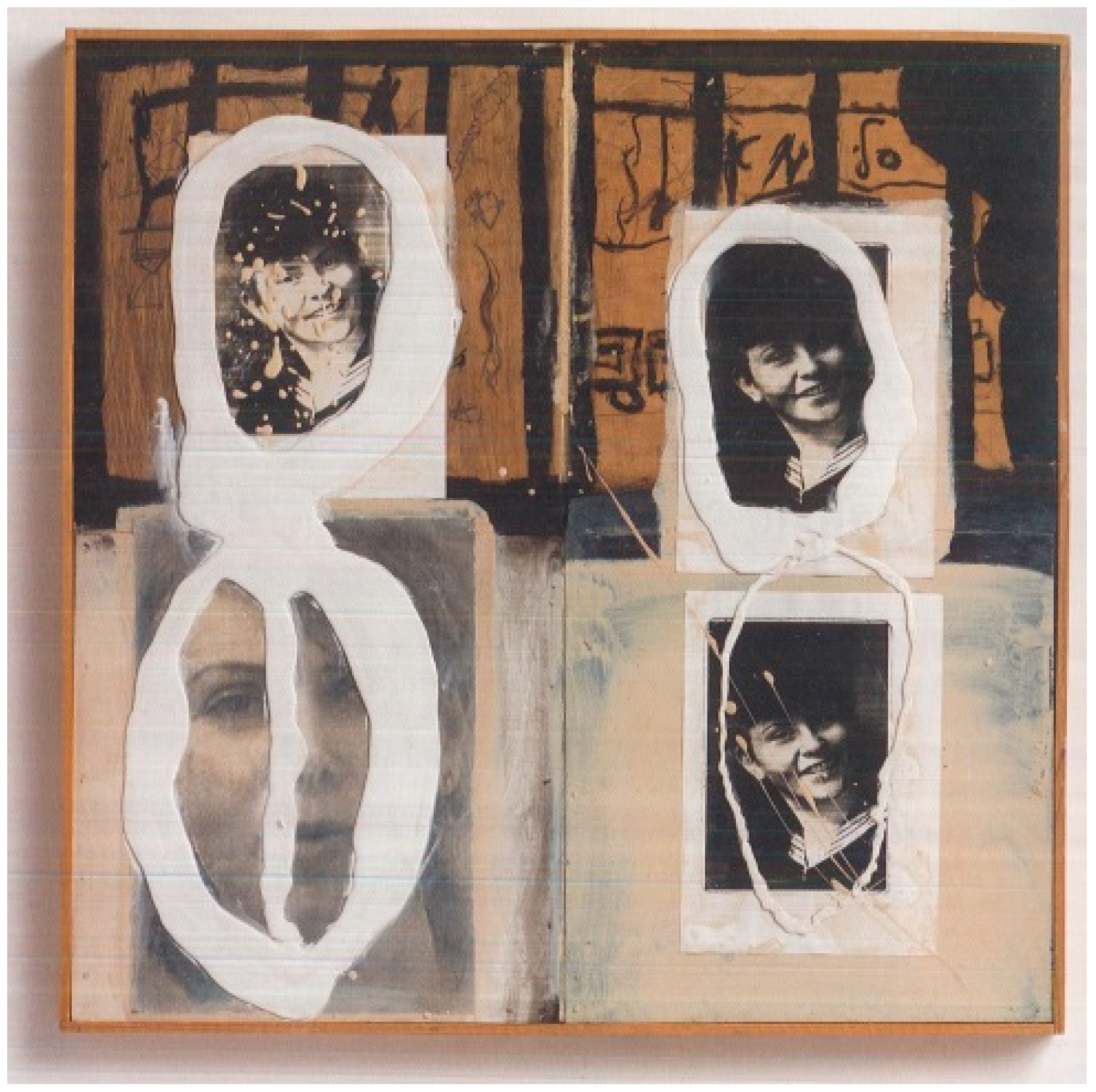

1.6. Neither Here nor There—Gary Goldstein’s Ghosts

I always knew that both my parents came from very large families. […] All those family members were murdered during the war. […] I never thought of their families, my families, and what happened to them. For me, their presence was one of lack. While preparing for a lecture at a conference at Bezalel, […] I realized with surprise that my work assumed the guise of a forest of faces, a forest of portraits of people that I never met […] Yet, I never stop thinking about them. Their images appear, transform and reappear in drawing after drawing, year after year on pages of old books upon which I create my works.

This childhood recollection of painful awareness of dissimilation emphasizes an important aspect that the works of Wakstein and Maor clearly articulate as well: constructing personal identity through utter rejection of their parents’ identity.Each sentence when I was growing up never ended in the same language in which it began. The English words were pronounced in a heavy, Yiddish accent something which made me ashamed. I looked down upon my parents, upon their foreignness. Those diminutives, Gersheleh, Hanka, Moisheleh, made them small. They made us small. They diminished us. They created the feeling in me of Gershon, a stranger in a strange land. Nicht a hier. Nicht a heir. Neither here nor there.

1.7. Philip Rantzer’s Wandering Homes

As a child, having arrived from a neighborhood of immigrant transit camp evacuees to a neighborhood where we mixed with the local “salt of the earth”, I was ridden by feelings of inferiority. I looked for a way to be an equal among equals. I couldn’t be equal the Sabra way. […] I took the Diaspora way (the Jewish way): using humor, becoming the classroom artist.

I still feel like an immigrant. I am an old-newcomer, but still a newcomer. An old immigrant […] I still speak Romanian with my parents. This is the language I grew up with. Somehow I feel intimacy precisely with that which is remote. […] I feel Jewish in an almost stereotypical sense.

The notion of nonbelonging as inherent to a Jewish frame of mind in contradiction to an assimilated, stable, sense of self—as highlighted in Rantzer’s works and certainly in Maor’s and Goldstein’s art as well—is not a new one. In the context of artistic practice, it is especially evident in Jewish American artist R. B. Kitaj’s (1932–2007) well-known First Diasporist Manifesto (Kitaj 1989). First published in 1989, it might well have been a direct source of influence on Rantzer and his colleagues, echoing their own personal experiences. Kitaj’s manifesto captures the same essence of Jewishness as an inner state of wandering, of being uprooted, living “in two or more cultures at once”44 (ibid., p. 19).[…my art] expresses a type of dissociation, detachment. Israeliness is comprised of this detachment, and mainly of not knowing. Israeliness is to be a conqueror and a defeatist, hero and dodger, to be all these things simultaneously. It’s the crystallization of a new and reformed place, which consists of these antithetical components. In the meantime, everything here is constantly crystallizing. In relation to this, Judaism is eternity. It is something so ancient and elementary—perhaps it is my anchor.

1.8. A Concluding Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aharonson, Meir, ed. 1999a. In a Closed Space. In Memory as History, History as Memory—Philip Rantzer, Simcha Shirman. The Venice Biennale, Israeli Pavilion Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Education, pp. 145–48. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonson, Meir, ed. 1999b. A Jewish Peter Pan. In Memory as History, History as Memory—Philip Rantzer, Simcha Shirman. The Venice Biennale, Israeli Pavilion Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Education, pp. 158–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonson, Meir, ed. 1999c. Memory as History, History as Memory—Philip Rantzer, Simcha Shirman. The Venice Biennale, Israeli Pavilion Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Ankori, Gannit. 2006. Palestinian Art. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke. 2007. Lost in Space, Lost in the Library. In Essays in Migratory Aesthetics: Cultural Practices between Migration and Art-Making. Edited by Sam Durrant and Catherine M. Lord. Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex and Race. Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V., vol. 17, pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Barkai, Sigal. 2016. ‘Historiographic Irony’: On Art, Nationality and In-Between Identities. Studies in Visual Arts and Communication 3: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Bolas, Gerald D., ed. 1996. Ketav, Flesh and Word in Israeli Art. Exhibition Catalog. Chapel Hill: Ackland Art Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Translated by Gino Raymond, and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Branden, Joseph W. 2003. Random Order—Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-Garde. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breitberg-Semel, Sarah, ed. 1986. The Want of Matter as Quality in Israeli Art. Exhibition catalog. Tel-Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Breitberg-Semel, Sarah, ed. 2011a. Gershuni—Selected Translations from the Hebrew Edition. Exhibition catalog. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Breitberg-Semel, Sarah, ed. 2011b. Radicalism with a Fold: The First half of the 1970s. In Gershuni. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 52–69. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Cage, John. 1961. Silence. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, Pauline. 2011. Implications of Blackness in Contemporary Art. In A Companion to Contemporary Art since 1945. Edited by Amelia Jones. Malden: Blackwell Press, pp. 356–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2016. Transnational Identities—Women, Art and Migration in Contemporary Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal, Efrat Yerday, Esti Almo Wexler, and Shula Keshet (Kashi), eds. 2017. The Monk and the Lion: Contemporary Ethiopian Visual Art in Israel. Gila Svirsky, trans. Tel Aviv: Ahoti—for Women in Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, Sam, and Catherine M. Lord, eds. 2007a. Essays in Migratory Aesthetics: Cultural Practices between Migration and Art-Making. Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex and Race. Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V., vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, Sam, and Catherine M. Lord. 2007b. Introduction. In Essays in Migratory Aesthetics: Cultural Practices between Migration and Art-Making. Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex and Race. Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V., vol. 17, pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Edelsztein, Sergio. 1993. Choreographer of Junk—Sergio Edelsztein and Philip Rantzer, a conversation. In Philip Rantzer. Edited by Sergio Edelsztein. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Artifact Gallery, pp. 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Haim. 1999. Gary Goldstein: Cyclical/Recycled. Exhibition Catalog. Beer Sheva: Avraham Baron Art Gallery, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, pages unnumbered. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Yona, and Tamar Manor-Fridman, eds. 2008. The Birth of Now: Art in Israel in the 1960s. Anat Schultz, trans. Exhibition Catalog. Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, Calvin. 2016. Immigration: Social Strains and the Challenge of Diversity. In Contemporary Israel, New Insights and Scholarship. Edited by Frederick E. Greenspahn. Jewish Studies in the Twenty-First Century. New York: New York University Press, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Gary. 2015. Searching for a Homeland among the Leaves of Old Books. In Israel: Land and Identity—Artworks from the Levin Collection, Jerusalem. Edited by Emma Gashinsky. Exhibition Catalog. Vienna and Jerusalem: The Levin Foundation, pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Gary. 2017. Extract from an unpublished text. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1959. Collage. In Art and Culture—Critical Essays. Edited by Clement Greenberg. New York: Beacon Press, pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Guilat, Yael. 2019a. ‘Living Room’ and ‘Family Gaze’ in Contemporary Israeli Art: Comparative Perspectives on Cultural-Identity Representations. Israel Studies 24: 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilat, Yael. 2019b. The ‘Lost’ Generation: Young Artists in 1980s Israeli Art. Sede Boker: The Ben-Gurion Research Institute. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hadar, Irith. 2009. Connections and Attributions. In Mind the Cracks!—Collages from the Museum and from Other Collections. Edited by Irith Hadar. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 169–72. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Avraham, Yigal Yadin, and Amir Gilboa. 1958. Israel’s First Decade. Tel Aviv: Masada. [Google Scholar]

- Kessus Gedalyovich, Michael, ed. 2006. Liberty: David Wakstein + Art Team. Tel Aviv: Omanut La’am. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kitaj, Ronald Brooks. 1989. First Diasporist Manifesto. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg, Aviad. 2010. Look Back in Anger—Aviad Kleinberg in Conversation with Philip Rantzer. In Philip Ranzter—Look Back in Anger. Edited by Ruti Ofek and Amon Yariv. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: The Open Museum, Tefen Industrial Park and Gordon Gallery, pp. 161–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Ora. 2010. Preface. In Down to the Smallest Details. Edited by Ora Kraus. Exhibition Catalog. Rehovot: Rehovot Municipal Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Liss, Dvora, ed. 2014–2015. Good Jew. Exhibition Catalog. Ein Harod: Mishkan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Makhoul, Bashir, and Gordon Hon. 2013. The Origins of Palestinian Art. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, Haim. My Father’s Suitcase. In Haim Maor—They Are Me. Edited by Ruthi Ofek. Exhibition Catalog. Tefen: The Open Museum and Omer Industrial Parks, p. 228.

- Maor, Haim, ed. 2014a. Broken Beads—Contemporary Artists on their Moroccan Identity. Exhibition Catalog. Be’er Sheva: Senate Gallery, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, Haim. 2014b. A Good Jew—Twice as Good. In Good Jew. Edited by Dvora Liss. Exhibition Catalog. Ein Harod: Mishkan Museum of Art, pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, Saloni, ed. 2011. The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora. Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchel, William J. T. 2011. Migration, Law, and the Image: Beyond the Veil of Ignorance. In The Migrant’s Time: Rethinking Art History and Diaspora. Edited by Mathur Saloni. Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, Ruthi. 2010. A calculated Game. In Philip Rantzer—Look Back in Anger. Edited by Ruthi Ofek and Amon Yariv. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: The Open Museum, Tefen Industrial Park and Gordon Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, Ruthi. 2011a. Haim Maor—They Are Me. Edited by Ruthi Ofek. Exhibition Catalog. Tefen: The Open Museum and Omer Industrial Parks. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, Ruthi. 2011b. They are Me—Ruthi Ofek in Conversation with Haim Maor. In Haim Maor—They Are Me. Edited by Ruthi Ofek. Exhibition Catalog. Tefen: The Open Museum and Omer Industrial Parks, pp. 280–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, Ruthi, and Amon Yariv, eds. 2010. Philip Ranzter—Look Back in Anger. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: The Open Museum, Tefen Industrial Park and Gordon Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat, Gideon. 1980. The New Jerusalem School. In The Story of Israeli Art. Edited by Binyamin Tamuz. Tel Aviv: Masada, pp. 277–327. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat, Gideon. 1998. One Hundred Years of Art in Israel. Translated by Peretz Kidron. Boulder: Westview Press in Cooperation with the Mizel Museum of Judaica. [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat, Gideon. 2013. Broader Horizons—120 Years of Israeli Art, from the Ofrat Collection to the Levin Collection, Selected Works, Part II. Tel-Aviv: Vienna-Jerusalem Foundation for Israeli Art. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, Anne Ring. 2017. Migration into Art; Transcultural Identities and Art-making in a Globalised World. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raz-Krakotzkin, Amnon. 2017. Exile within Sovereignty: Critique of "The Negation of Exile" in Israeli Culture. In The Scaffolding of Sovereignty. Edited by Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, Stefanos Geroulanos and Nicole Jerr. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rojanski, Rachel. 2004. The Status of Yiddish in Israel, 1948–1951: An Overview. In Yiddish after the Holocaust. Edited by Joseph Sherman. Syracuse: Boulevard Books, pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Romberg, Osvaldo. 2011. Haim Maor: A Lone Rider. In Haim Maor—They are Me. Edited by Ruthi Ofek. Exhibition Catalog. Tefen: The Open Museum, Tefen and Omer Industrial Parks, pp. 247–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, Sarit. 1991. Landmarks: A Local Development. In Routes of Wandering: Nomadism, Journeys and Transitions in Contemporary Israeli Art. Edited by Sarit Shapira. Translated by Richard Flantz. Exhibition Catalog. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, pp. 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, Anita. 2012. Israel—A History. Translated by Anthony Berris. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, Yaniv, ed. 2014. David Wakstein Painting, 1975–2014. Exhibition Catalog. Ein Harod: Mishkan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Shehori, Ran. 1974. Art in Israel. Tel Aviv: Sadan. [Google Scholar]

- Silvain, Gerard, and Henri Minczeles. 1999. Yiddishland. Translated by David Wharry. English Edition Edited by Donna Wiemann. Corte Madera: Gingko Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinlauf, Varda. 2002. Neverending Story. In Philip Rantzer—No No No Don’t Leave Me Alone Here. Edited by Varda Steinlauf. Exhibition Catalog. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zalmona, Yigal. 2013. 100 Years of Israeli Art. Farnham: Lund Humphries in Association with the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Zalmona, Yigal, and Tamar Manor-Friedman, eds. 1998. Kadima—The East in Israeli Art. Exhibition Catalog. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermann, Moshe. 2015. Aspects of the Negation of Diaspora. In Israeli Exiles: Homeland and Exile in Israeli Discourse. Edited by Ofer Shiff. Iyunim Bitkumat Israel: Thematic Series Vol. 10; Be’er Sheva: Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, pp. vii, 232–39. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Artistic preoccupation with migration and diaspora has always been present in local Israeli art, although it was consistently marginalized in the past. Former representations of migration differ significantly from contemporary ones in their use of symbolic language, as exemplified by the works of artists Naftali Bezem (Germany 1924–Israel 2018) and Yosl Bergner (Austria 1920–Israel 2017). |

| 2 | Bourdieu defines habitus as “a set of dispositions that incline agents to act and react in certain ways” (Bourdieu 1991, p. 12). |

| 3 | Three central references on migration and aesthetics are (Petersen 2017; Mathur 2011; Durrant and Lord 2007a). |

| 4 | On the mobility turn, see (Urry 2007). For a contextualization of this term into current migratory aesthetic discourse, see (Petersen 2017, pp. 1–46). |

| 5 | See, for example, (Bal 2007; Durrant and Lord 2007b, pp. 23–36; Mitchel 2011; and Mathur 2011, pp. 59–77). |

| 6 | This includes ‘Mizrahi’ Israelis (a local term for immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa). In 1998 the Israel Museum held the first major exhibition focusing on Eastern influences on local art (Zalmona and Manor-Friedman 1998). Israeli Mizrahi identity has gradually become a significant artistic subject during the last two decades, see (Maor 2014a). For research on the art and identity of women who emigrated from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia in the early 1990s, see (Dekel 2016; Dekel et al. 2017). On artistic explorations of identity stratification among local Palestinian, Arab-Israeli, Bedouin, and Druze and their intricate state of imposed migration, see (Makhoul and Hon 2013; Ankori 2006). |

| 7 | See, for example, (Barkai 2016). Barkai focuses on Israeli-born artists from a younger generation who live and work outside of the country, and thus on the impact of their decision to emigrate on their self-articulation, which results in a state of mind of being in-between. |

| 8 | A 2019 exhibition at the Artists’ House in Tel Aviv, the show And the Ship Still Sails (curator: Dalia Danon) focused on found personal objects as agencies of childhood memory and diasporic origin. The exhibition Souvenirs, which Haim Finkelstein and Haim Maor co-curated (May–August 2008, The Senate Gallery, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev), explored repressed historical and personal memories in works by Israeli and Polish artists. The 2009 exhibition Family Traces at the Israel Museum (curator: Tamar Manor-Friedman) explored family photo albums, with a section referring to the work of Israeli artists, which notably served as “testimony to a history of displacement and loss.” Exhibition site, The Israel Museum, https://museum.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2009/FamilyTraces/about.html. Retrieved: 5 April 2019. |

| 9 | Ibid., see especially pp. 113–114, 203–205. |

| 10 | On the dominance of collage as a central feature of local art during the 1960s and the 1970s, and the inclusion of texts within it, see (Fischer and Manor-Fridman 2008, pp. 49–53). |

| 11 | Two additional directions in local art during the 1970s were conceptual art absorbed in epistemological interrogations and political actions and performances. See (Ofrat 1980, pp. 277–327). |

| 12 | The word “collage” appears 19 times in her relatively short catalog essay (Breitberg-Semel 1986). This matter demands further consideration, but that lies beyond the limits of this research. |

| 13 | Wakstein studied in the Bezalel school of art, Jerusalem (1975–1979), whereas Maor and Rantzer studied at the Midrasha (Arts Teachers’ Training College, Ramat Hasharon) (1973–1976, 1979–1982, respectively). |

| 14 | (Edelsztein 1993, p. 55). Similarly, Haim Maor recalled Raffi Lavie’s negative reaction to his first show, which dealt with Jewish and identity-related content through the biblical story of Cain—an unequivocally repudiated subject in the art scene at that time—dismissing his potential for becoming an accepted artist. In a similar vein, Lavie told Gary Goldstein that he would never be successful in becoming Israeli and would always be an outsider, meaning that as an insult. From conversations with the artists, April–June 2019. |

| 15 | From a conversation with the artist, March 2019. |

| 16 | For a detailed account of this complexity, see (Ankori 2006, pp. 178–196). |

| 17 | For a detailed discussion on the internal and external circumstances of immigration to Israel and their complex social and demographic implications, see (Goldscheider 2016). |

| 18 | Quoted from English abstract, for more, see (ibid., pp. 232–239). |

| 19 | For more on this subject, see (ibid., pp. 222–270). |

| 20 | Gershuni’s focus on identity stratification during the early 1980s also largely addressed his homosexuality and confronted the ethos of Israeli masculinity by homoerotic references to soldiers. See, for example, (Zalmona 2013, pp. 323–27). |

| 21 | All information, unless specified otherwise, is taken from my conversations with the artist, May–July 2019. |

| 22 | See (Silvain and Minczeles 1999), pages of photographs unnumbered. |

| 23 | Wakstein, 2014, interviewed by Yaniv Shapira (2014, p. 201). |

| 24 | Wakstein identified the other photograph as a portrait of Israeli curator Ruthi Director; it derives from another series dedicated to female curators on the Israeli art scene. The artist deliberately connects the image of these women with images of his mother in what he terms images of women who have influenced his life and are part of the constant blurring of boundaries in his art between his private life and the local art scene as artistic subject matter. As for the recurring male portrait, it is loosely based on a photograph of the former mayor of Rishon LeZion, where Wakstein lives; his students altered the image in one of Wakstein’s studio lessons. |

| 25 | Ramla is mostly Jewish but also has a significant Arab minority of 25%. |

| 26 | Wood not only serves as a surface in Maor’s work, but is also a dominant feature in his art, which he sometimes emphasizes by using crude rather than treated wood. This is especially evident in a series executed over what bears the impression of a wooden fence: for example, in the works Pupil, 1995, industrial paint and lacquer on wood, 129 cm × 81 cm; Susanna-Shoshana, 1987, high-gloss paint and lacquer on wood, 70 cm × 131 cm. See the images in (Ofek 2011a, pp. 131–32). |

| 27 | On the struggle between Yiddish and Hebrew during the first years of the State of Israel, see (Rojanski 2004); “The story of Yiddish in Israel is the story of the melting pot policy in miniature, a policy whose zealous implementers believed that immigrants from all the diasporas must relinquish—immediately and unhesitatingly—the cultures and traditions they had brought with them and adopt the local ethos and its culture. It was an unrealistic policy. In actuality the immigrants created cultural ‘niches’ that supplied their cultural desires and needs” (Shapira 2012, pp. 250–51). |

| 28 | “I was a child growing up in Israel during the 1950s. Yet, mentally, I was growing up in a ‘bubble’ of Warsaw. The language spoken in my home was Yiddish, and my parents spoke Polish between them.” From a conversation with the artist, July 2019. |

| 29 | From conversations with the artists, May–July 2019. |

| 30 | Maor has often collaborated with Bedouin-Palestinian artist Khader Oshah, and Arab-Israeli artist Mohammad Said Kalash. Another interesting example is a Maor piece in which he wrote in Yiddish the words: “איך בין אן אארבער” (“I am an Arab”; untitled, 1989, 208 cm × 152 cm, collection of the artist). He embroidered this text on an ornamental satin curtain resembling the curtains covering the front of the Holy Ark in the synagogue. The result is an ironic obstruction of meaning and a hybridization of local identity that deals with religious Judaism, Yiddish, and Arab identity. |

| 31 | From a conversation with the artist, July 2019. |

| 32 | See (Ofek 2011b). They Are Me—Ruthi Ofek in Conversation with Haim Maor. In (Ofek 2011a, p. 290). |

| 33 | See (Maor 2011). My Father’s Suitcase. In (Ofek 2011a, p. 228). |

| 34 | This account refers to Maor’s decision to Hebraize his family name of Moshkovits as a young adult and also relates to the fact that he bears his paternal grandfather’s name. |

| 35 | From a conversation with the artist, July 2015. |

| 36 | The artist commented recently that he has never been cynical about the Zionist dream (Goldstein 2015, p. 21). |

| 37 | Rantzer’s art is often referred to as Neo-Dada (Steinlauf 2002, p. 111). |

| 38 | The result bears a strong resemblance to Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblages (termed “combines”) of the 1950s, in dealing with childhood memories through the inclusion of ready-made objects in his work. On this aspect of Rauschenberg’s early works, see (Branden 2003, pp. 141–44). For a similar interpretation, see (Cage 1961, p. 103). |

| 39 | Rantzer has described this work as “a kind of a hybrid stage comprised of fragmented furniture”. From a conversation with the artist, July 2019. |

| 40 | In a Closed Space. In (Aharonson 1999c, p. 148). |

| 41 | The words “minchunile din vis” (“the lies of the dream”), which Rantzer quoted from this song, reappear in another multimedia installation that he created in 2006 under the title 10E, consisting of a car, a video, and sound. See the image in (Ofek and Yariv 2010, pp. 140–41). |

| 42 | It is a romantic and lively account of the first moment he saw her, and his immediate realization, while conversing with a friend on the street, was that she would become his wife. |

| 43 | A Jewish Peter Pan, in (Aharonson 1999c, p. 158). |

| 44 | “Painting is a great idea I carry from place to place. It is an idea full of ideas, like a refugee’s suitcase, a portable Ark of the Covenant” (ibid., p. 11). As noted above, on the significance of the notion of wandering in Jewish thought and in shaping Israeli self-articulation, see also (Shapira 1991). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gashinsky, E. An Aesthetic Pattern of Nonbelonging—Immigration and Identity in Contemporary Israeli Art. Arts 2019, 8, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040157

Gashinsky E. An Aesthetic Pattern of Nonbelonging—Immigration and Identity in Contemporary Israeli Art. Arts. 2019; 8(4):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040157

Chicago/Turabian StyleGashinsky, Emma. 2019. "An Aesthetic Pattern of Nonbelonging—Immigration and Identity in Contemporary Israeli Art" Arts 8, no. 4: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040157

APA StyleGashinsky, E. (2019). An Aesthetic Pattern of Nonbelonging—Immigration and Identity in Contemporary Israeli Art. Arts, 8(4), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040157