Abstract

An often cited 1938 repatriation from the Museum of the American Indian in New York City to the members of the Water Buster or Midi Badi clan of the Hidatsa tribe in North Dakota is revisited. Rather than focusing on this event as a “first” in repatriation history or using it as a character assessment of the director of the museum, this account highlights the clan’s agency and resistance through an examination of their negotiation for the return of a sacred bundle and the objects they selected to provide in exchange. Through this example, we see how tribes have had to make hard choices in hard times, and how repatriation is a form of resistance and redress that contributes to the future of a community’s wellbeing in the face of a history of religious and colonial oppression.

Trusting that you will see this in the same light as we do and decide to co-operate with us for the return of the Sacred Bundle.Hidatsa Water Buster Clan to George Heye at the Museum of the American Indian, 1934

1. Introduction

The return of a medicine bundle in 1938 from the Museum of the American Indian in New York City to the Water Buster or Midi Badi clan of the Hidatsa tribe is often mentioned as the first known successful repatriation in the United States (Bad Wound 1999; Carpenter 2005; Colwell 2017, p. 35; Cooper 2008, p. 68; Fine-Dare 2002, p. 66; Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 315).1 It has also been cited as a means to assess the character of George Gustav Heye, the collector who founded the Museum of the American Indian—either praising his actions (Alivizatou 2012; Mason 1958, p. 24) or critiquing them (Cooper 2008, p. 69; Fialka 2004; Grabouski 2011, p. 115; Jacknis 2006, p. 533; Kidwell 1999, p. 17; McKeown 2013, p. 30). Even in a news article published on the day of the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), the 1938 repatriation was mentioned to indicate Heye’s character as “an imperious man who didn’t always know what he was doing”, because he called the “Gros Ventre” (Hidatsa) leaders “Sioux” during their meeting with Heye (Fialka 2004). Rarely, with the exception of (Gilman and Schneider 1987) The Way to Independence: Memories of a Hidatsa Indian Family, 1840–1920, is a recounting of this event about the Hidatsa themselves and their extraordinary efforts to bring the Bundle home, or about what happened since and the role the Bundle plays in the lives of the Water Buster clan members today. But that was always the point of the return: securing the health and wellbeing of their community into the future.

Long before the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990), which provides guidelines and legal mechanisms for repatriation, we see the Hidatsa identifying a sacred item as key to this process of community wellbeing, explaining the meaning of cultural patrimony, and taking the initiative to advocate for return. I focus on what most earlier accounts miss: the agency and activism of the Water Buster clan members to achieve the Bundle’s return—the support they marshalled, the money they raised, and the way they managed the publicity.

I came to this story unintentionally in 2016, when someone working for the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara (MHA) Nation gave me some digital files and told me he thought I might find them interesting given my work with community members. They were scans of letters between a number of people, including a few who I recognized immediately: Reverend Harold Case, a missionary about whom I had produced a video documentary in collaboration with elders in the MHA community (Shannon 2017b); George Gustav Heye, founder of a museum collection that would later become the National Museum of the American Indian, where I had worked in the past; and John Collier, who I had often read about in my studies of American Indian Law. In the following months, while trying to write about something else I kept being drawn back to the letters, transcribing over one hundred and twenty pages of them as a form of listening to the conversations among many individuals and over many years regarding the Water Buster Bundle. As I was reading, I grew frustrated that Hidatsa clan members’ concerns, requests, and pleas had to be mediated by anthropologists, missionaries, and Indian agents. But then, in the midst of the circulating letters about the Hidatsa clan members, there was a signed document with their names and their finger prints. At the conclusion of the letter, they stated, “Trusting that you will see this in the same light as we do and decide to co-operate with us for the return of the Sacred Bundle”.

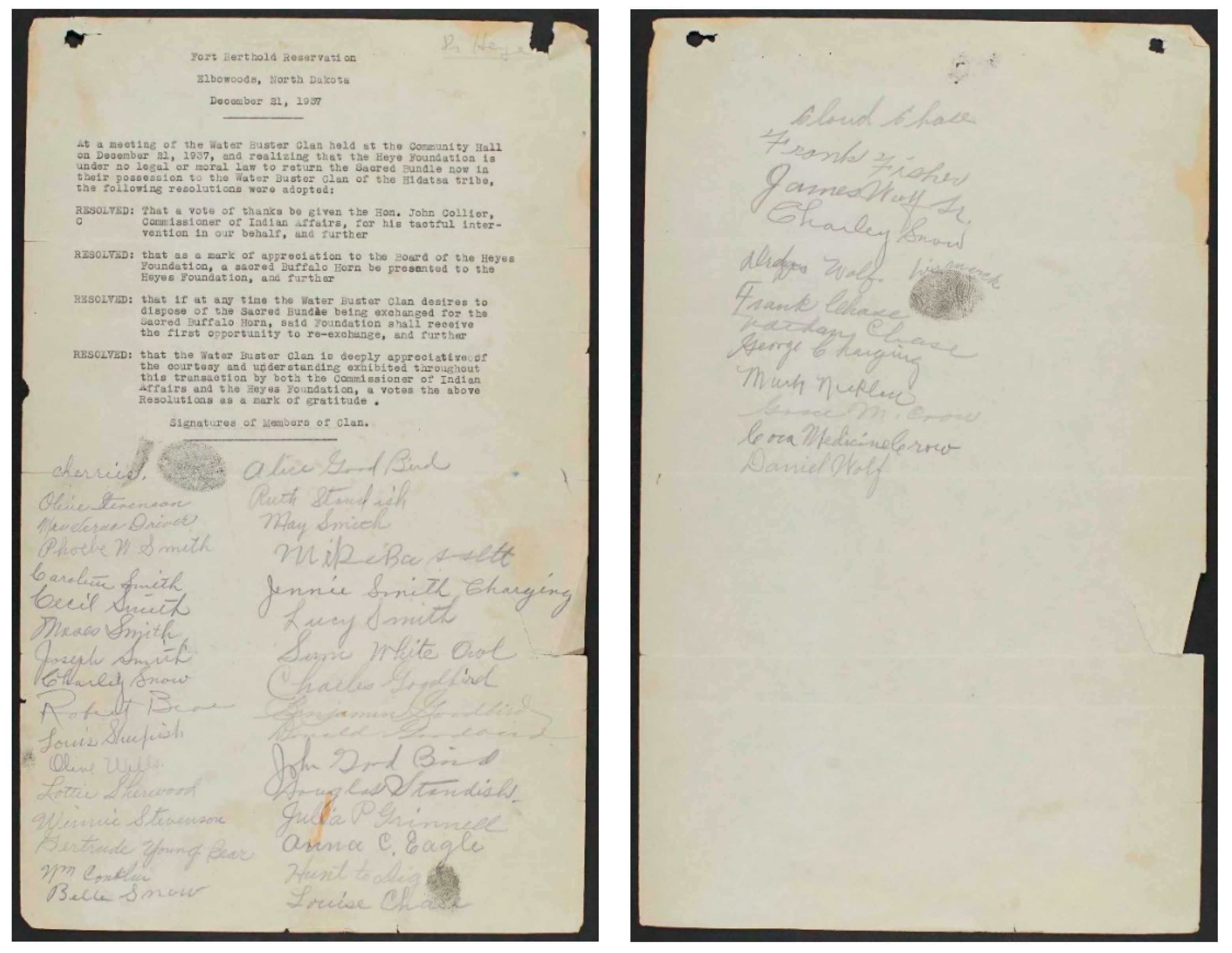

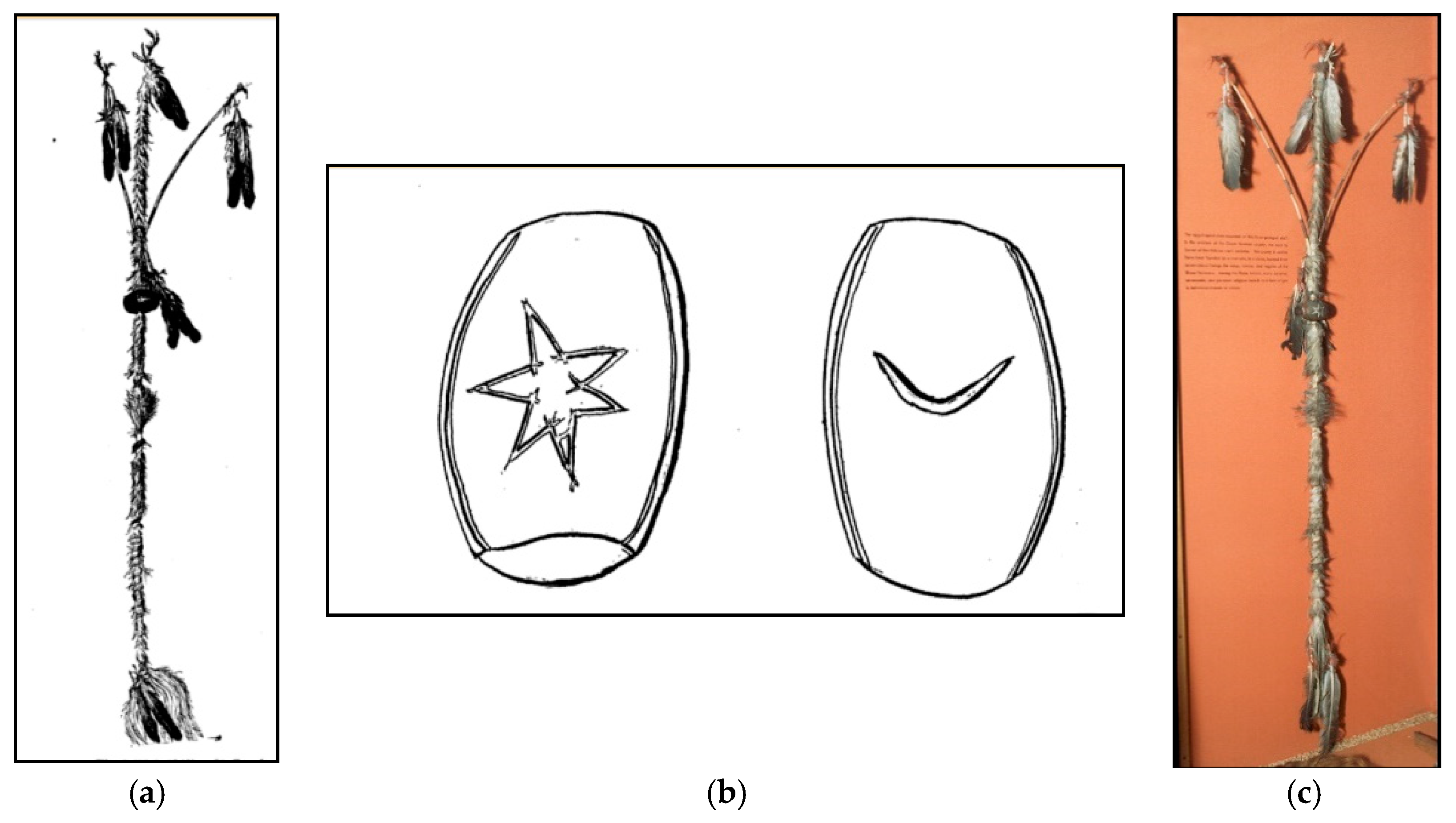

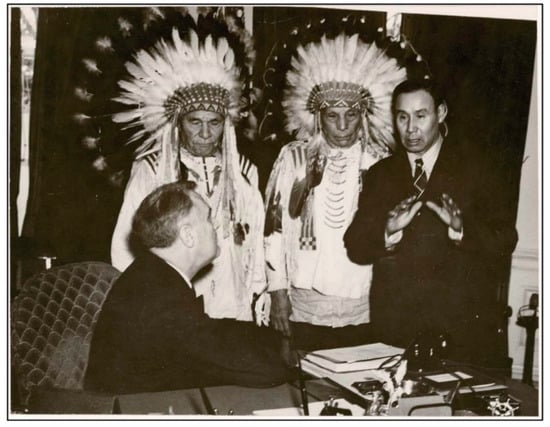

In 1934, twelve Water Buster clan members signed a letter to George Heye requesting the return of the sacred Water Buster Bundle from the Museum of the American Indian in New York City (Figure 1).2 After four years of negotiations, and urging from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the museum agreed to return the Bundle.

Figure 1.

Signature page, 1934 letter from Water Buster clan to Heye requesting the return of the sacred Bundle. MAI/Heye Foundation Records, Box 318 Folder 8; NMAI Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution (SI).

In the accounts of the 1938 repatriation, often an image of the Bundle is included—even recently in an NMAI publication (Spruce 2004, p. 112). Today, it is generally agreed that medicine bundles or other sacred items should not be reproduced or shared publicly (at least not without explicit permission from the originating community). So here, I hope to present a more community-oriented perspective on this historic event. I am deliberately not including previously published images or mentioning the name, contents, or purpose of the sacred Bundle that was returned for two main reasons: first, out of respect for the clan and the cultural sensitivity of sacred bundles; and second, because that knowledge is not necessary to communicate the remarkable achievement of the Hidatsa in not only negotiating its return, but publicizing their request and allowing their experience to become an example for other tribes to be inspired by and learn from (cf. Bad Wound 1999). Hidatsa leaders at the time also demonstrated to the public how important sacred items are and that they were still in use in Native communities.

Instead, I focus here on the items the Water Buster clan selected to exchange for the Bundle—because this was not just a return, something of equal ceremonial value was required to take its place. It is this negotiation that I want to focus on for this Special Issue that is highlighting resistance, resilience, and survivance of Native peoples through the objects they created in the 19th and 20th centuries. The objects I highlight here represent this negotiation: they are a buffalo horn (NMAI 197237.000) and a stone hammer (NMAI 197236.000), as well as a document provided at the same time to the museum that includes resolutions passed by the clan and signed by forty-five of its members. These items are now housed in the National Museum of the American Indian because, in 1989, George Heye’s collection from the Museum of the American Indian became the founding collection of the NMAI.

This account is based on eight years of working with members of the MHA Nation on various collaborative projects. It was developed through archival research including repatriation records and letters to George Heye and others in the NMAI archives, object research at the National Museum of the American Indian, close attention to archival photographs, and interviews and conversations with NMAI repatriation staff, the MHA tribal historian and a former museum administrator, conversations with the current Bundle keeper, and other MHA Nation community members.

1.1. The Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation

Today, the Water Buster or Midi Badi clan is one of seven clans of the Hidatsa tribe.3 The Hidatsa are one of three tribes—along with the Mandan (Nueta) and the Arikara (Sahnish)—that reside on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. The Missouri River passes through the center of the reservation which was established in 1870 by the US government. The three tribes came to live together in the mid-19th century after their populations had been drastically reduced in number through disease, intertribal warfare with the Sioux nations, and other hardships. After describing the history of the three individual tribes, the tribal government of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara (MHA) Nation explains under “Three Affiliated Tribes History”,

Each tribe maintained separate bands, clan systems, and separate ceremonial bundles. After the devastation of the small pox epidemics of 1792, 1836, and 1837, homogenous societies evolved for economic and social survival. The three tribes lived in earth lodges, were farmers, hunted wild game and relied heavily on the buffalo… They maintained a vast trading system and were considered middlemen by neighboring tribes with different types of trade products.(MHA Nation 2018)

Note the centrality of bundles and the banding together as a strategy for survival.

From when MHA tribal representatives signed the Fort Laramie Treaty in 1851 to present day, the land base of the MHA Nation has been reduced from 12,500,000 to 457,837 acres (Berman 1988). Contributing to this reduction in lands was the Garrison Dam, completed in 1953 by the US Army Corps of Engineers—another large-scale event, like smallpox in the 19th century, which community members identify as contributing to intergenerational trauma.4 The dam created a reservoir covering 155,000 acres that were home to the most precious lands and settlements on the reservation. The flood devastated the community, relocating 90% of tribal members (Berman 1988; Lawson 2009). Until the relocation, the three tribes had been self-sufficient. Tribal members moved from the fertile Missouri River bottomlands to the harsher bluffs above the newly created Lake Sakakawea. MHA community members were not only relocated to other areas of the reservation in 1953 but also to cities like Denver as part of a broader US policy later formalized in the Indian Relocation Act of 1956. This act aimed to move Native Americans away from reservations as part of the government’s policy of termination at the time which focused on dismantling reservations and terminating the government’s trust responsibility to tribes (Fixico 2000, p. 10).

There are now over 16,000 enrolled tribal members and about half live on the reservation (MHA Nation 2019a). Like other reservations in the United States, the MHA Nation is a sovereign tribal nation with its own constitution, government, police force, tribal courts, and health and education programs. A casino opened in 1993, along with rights to oil and mineral resources, have become means for the Nation to increase economic development, support health and education services, and start construction of a new cultural center.

The focus of this essay is the 1930s. During this time, the three tribes were, as Meyer (1977, p. 190) puts it, “cushioned” from some of the worst effects of the Great Depression. In 1931, a settlement was reached between the tribe and the US government that compensated enrolled members for the wrongful taking of lands promised in the Treaty of Fort Laramie due to executive orders in 1870 and 1880 and a land sale in 1894. The funds were used primarily for housing and other needs like dairy cattle and farm machinery (Meyer 1977, pp. 188–89). As a result, in comparison to other tribes, they had a “higher material standard of living”. But the drought still proved devastating, with crop failures two years in a row and then, in 1934—the worst year of the drought—there was no crop at all (Meyer 1977, p. 190). Also in 1934, 90% of eligible voters on the reservation voted on whether to adopt the Indian Reorganization Act and create a tribal constitution and governing council; 77% of them voted yes (Meyer 1977, p. 195).

There were significant improvements in transportation with new roads and the construction of the Four Bears Bridge in 1934 which connected the reservation on either side of the Missouri River at the main town of Elbowoods. People at the time were leaving their allotments and concentrating into community centers (Meyer 1977, p. 203). Also during the 1930s, along with an increase in population size and more integration of people from the outside, there was “growing indications of a desire to retain such elements of the aboriginal culture as survived and even to recover some of those that had been lost … [and a] revival of pride in traditional customs and values” (Meyer 1977, pp. 204–5). During this time, there were requests to reclaim Native names, and the Water Buster Bundle.

1.2. Repatriation as Resistance and a Strategy for Survivance

Until the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act, Native Americans did not have the freedom to practice their religious ceremonies in the United States. As the act acknowledges:

Whereas such laws at times prohibit the use and possession of sacred objects necessary to the exercise of religious rites and ceremonies; Whereas traditional American Indian ceremonies have been intruded upon, interfered with, and in a few instances banned: Now, therefore, be it Resolved… That henceforth it shall be the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions of the American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut, and Native Hawaiians, including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonials and traditional rites.(American Indian Religious Freedom Act 1978)

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990) was the complement to gaining that religious freedom: ensuring disinterred ancestors could be laid to rest with their burial items, and that items in museums that people needed to conduct particular ceremonies could be returned to be put back into practice. However, as this case and others show, requests for repatriation were going on long before these laws were enacted.

The attempt to reclaim the Water Buster Bundle was not the first request for return of sacred items from a museum to a tribe, or even the first claim made to Heye. In 1914, he was challenged by someone in the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs on behalf of the Six Nations Chiefs in Grant River Territory regarding illegal procurement of Haudenosaunee wampum belts; Heye denied the charges and the request for return (Bruchac 2018, p. 79). Other earlier cases have been documented, but they too were unsuccessful, like the Apaches request in 1883 for the return of items that cavalrymen had looted from a cave in Arizona (Colwell 2017, p. 35).5 The return of the Water Buster Bundle was, however, “the earliest nationally celebrated case of repatriation” (Colwell 2017, p. 35). In 1999, Indian Country Today published a weekly series titled “Millennium Countdown” which included “some of the significant moments and individuals of the last hundred years” in the lives of Native peoples. There were two events for 1938, one of which was “The sacred Midipadi Bundle is returned to the Hidatsa people marking the first successful efforts to repatriate Native American sacred objects to their rightful caretakers” (Bad Wound 1999, p. A6). It was also one of the earliest examples to demonstrate publicly how sacred items are understood to be essential to community wellbeing.

In her discussion of the return of wampum, Bruchac describes the “insidious logic” in which museums posited that if a sacred item was “a relic of forgotten heritage”, and if it was “not essential to tribal survival, then it rightfully belonged in museums” (Bruchac 2018, pp. 72–73). She describes the “tactics of strategic alienation” that shift the meaning of items from sacred to secular, from tribal heritage to museum relics. These tactics include removing sacred items from tribal custody, de-tribalizing them by representing Native Nations and their traditions as dead or dying, shifting ownership from tribal heritage to settler colonial heritage, concealing them or the information associated with them, and displaying them as valuable relics or collectables (Bruchac 2018, pp. 74–75).

Repatriation is a form of resistance—to these tactics of strategic alienation, to colonial and religious oppression. Repatriation is also a form of survivance, a form of taking action to go beyond survival, to ensure community health and wellbeing through maintaining, reclaiming, and revitalizing cultural knowledge and practices. While “survivance” is a term coined by (Vizenor 1999, 2008), it is Sonya Atalay’s (Anishinabe-Ojibwe) direct and clear interpretation that I turn to as a framework for understanding the Water Buster Bundle exchange as resistance and survivance. She explains that “The concept of survivance … does not refuse stories of struggle, particularly those that create a context for understanding and appreciating the creative methods of resistance and survival in the face of such unimaginable turmoil … One cannot appreciate and experience the power of Native survivance if the stories and memories of our histories are not placed within the context of struggle” (Atalay 2006, pp. 609–10).

This understanding of repatriation as resistance and survivance comes from many examples. I highlight here We Are Coming Home: Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence (Conaty 2015), a book that includes chapters authored by a number of Blackfoot tribal members who were involved in the return of medicine bundles to their communities from the Glenbow Museum in Canada. They describe the pressures that led to the loss, and to the reclaiming, of their sacred bundles and knowledge. Allan Pard explains that “missionaries worked to imbue us with negative attitude toward our culture, our activities, our ways, our language, and ourselves as a people. Many of us ended up believing that it was wrong to do what we were doing; it was wrong to be ‘Indian’. Our interest in repatriating bundles was stimulated when we finally came out of that way of thinking” (Pard 2015, p. 132). Until that time, Frank Weasel Head explains that “in consideration of the anthropologists’ expressed purpose of saving the religious materials for our own future generations, some of our Elders decided to ceremonially transfer their bundles to museum representatives” (Weasel Head 2015, pp. 155–56). That is to say, while this 1938 case is more well-known, it is not entirely unique.

The director of the Glenbow Museum supported the return of the Blackfoot bundles, noting “the importance of repatriation to enhancing community well-being” (Janes 2015, p. 12), or as Krmpotich puts it, “repatriation acts as one means of healing and improving the well-being of multiple generations … past, present, and future” (Krmpotich 2014, p. 69; see also Atalay 2019; Shannon 2019b; Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2012). In literature about repatriation, its connection to healing first appeared in 1995, when Steven Newcomb (Shawnee/Lenape) asserted that such “efforts are aimed at assisting our communities to heal from generations of genocide and cultural devastation” (cited in (Atalay 2019, p. 80)). Frank Weasel Head puts it in these terms: “Whenever we bring home something that came from our ancestors, it ignites our will and our self-esteem. We remember that, at one time, we were able to do all these things on our own. If we bring back a bundle, we can bring back other parts of our culture. To me, it is all part of repatriation. It is not only a repatriation of sacred items. It is a repatriation of a way of life that was taken away from us through residential schools and all those other efforts to assimilate us” (Weasel Head 2015, pp. 179–81).

2. Negotiating the Return of the Water Buster Clan’s Bundle

In 1907, the Waterbuster Clan sacred Bundle was sold to missionary and anthropologist Gilbert Wilson by Wolf Chief, the son of Small Ankle. Small Ankle had been the Bundle keeper until he suddenly passed away in 1888.6 It is customary for the Bundle to be purchased by another clan member to transfer guardianship within the clan. It had ended up in Wolf Chief’s care, but he was not a Water Buster and was not trained or appointed to be the next keeper. George Gustav Heye provided the funding for Wilson to make the purchase and placed it in his collection. More than ninety years later, Heye’s collection was acquired by the Smithsonian to be the foundational collection of the National Museum of the American Indian. People may wonder, why did Native individuals part with treasured items? It was often a result of hard times, and hard choices. The story of the return of the Water Buster Bundle provides a specific example through which to understand these hard choices.

2.1. Hard Times

During the period in which Wolf Chief made the decision to sell the Bundle, the US government was engaged in the religious and colonial oppression of Native peoples. They had been confined to reservations, reservations were being broken up through the Dawes Act, and there was fear associated with practicing Native spiritual traditions as their ceremonies were banned by authorities and condemned by missionaries.7 There were also significant changes in leadership happening with new administrations both on the reservation and within the federal government.

In 1870, the Fort Berthold reservation was established, and tribal members were barred from leaving the reservation without a pass. During the 1870s, the Federal government assigned the Protestant Christian, Congregational Church to the Three Affiliated Tribes. At the time, the government was dividing up reservations among the various religions to determine which missionaries would be allocated to them as part of a larger policy of assimilation. Missionary Charles Hall arrived in 1876 and worked with the Indian agent towards this goal. Native languages, cultural practices, spiritual practices, and families were all being systematically undermined through US government policies of assimilation, missionization, and boarding schools.

Edward Goodbird was the first MHA tribal member to become an ordained Congregational minister. In 1913 he said, “I thought also that this Indian life and these Indian customs of ours cannot long continue. I could see that white men’s ways of thinking about God were becoming stronger; Christian ways are being recognized on this reservation, and they are going to prevail” (as quoted in Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 280). Goodbird, who was an interpreter for Gilbert Wilson, was also the grandson of Small Ankle and Wolf Chief’s nephew. He provided more context for these thoughts and for the sale of the Bundle in a 1935 statement to the Superintendent of the reservation.8 Goodbird attested that, at the time of the sale in 1907,

Medicine bundles, customs and ceremonies were being disregarded. The United States Government, in order to civilize its wards had prohibited pagan practices among them, knowing that in many instances self-torture existed in the ceremonies. Failure to comply with such requirements encouraged severe punishment. Hence, it is easy to realize why the “Water Buster” [Bundle] was totally ignored. Christianity had already been introduced many years before that period of time, and, that too, counteracted matters not Christian.9

Daniel Wolf mentioned similar pressures in his 1935 interview with the Superintendent, who reported:

Dan Wolf, although a convert to the Roman Catholic faith, still exhibits a strong leaning toward the rituals, beliefs, and ceremonies of the Water Buster Clan. He is the present Judge of the Indian Court and enjoys a good reputation among the Fort Berthold Indians. He appears one of the most anxious for the return of these medicine bundles. He states that the policy of the government, in years past, was to oppose meetings of the Water Busters and similar so-called pagan organizations, and hence these organizations did not flourish as they otherwise might have done. Dan Wolf also firmly believes that the long period of drought on this reservation is caused by the absence of these medicine bundles and the loss of them to the Clan members. In this belief Louis Sheepish, Foolish Bear and Foolish Woman concur. All of these members are most sincere in their belief.10

In other words, in the past “the traditional ceremonies required of a keeper were outlawed by the [Indian] agent, and anyone who performed them risked jail” (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 297).

During the already trying times of the Great Depression in the 1930s, and on top of the assimilation pressures from the government, the taking of Indian lands in the Great Plains resulted in an environmental catastrophe that was manmade. Low precipitation in the region coupled with over-cultivation and power farming practices culminated in massive soil erosion and dust storms that, by 1935, became known as the Dust Bowl (McLeman et al. 2014, p. 419). As an agricultural tribe, the Hidatsa were suffering, as were farmers across the plains. The Hidatsa lobbied the US government in various ways to address this crisis, including the request for the return of the Water Buster Bundle.

2.2. Hard Choices

By 1907, the Water Buster Bundle had ended up in the care of Wolf Chief, son of Small Ankle who had been the last Bundle keeper. Small Ankle passed away suddenly in 1888 before a new keeper had been identified, and for a time it remained in the care of a relative who was not a Water Buster, Charging Enemy.11 Wolf Chief was also not a Water Buster, he was Prairie Chicken clan. For the Hidatsa, clan membership comes from the mother. It remained in Wolf Chief’s care until 1907. The housing for the Bundle was in ill repair, he had converted to Christianity, he had asked clan members to retrieve it but no one stepped forward, and a number of hardships had befallen him, including the death of all his children, the last one while in college (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 297).

Wolf Chief, who had never allowed a white man to view the Bundle because “the spirits might be made angry”, invited Gilbert Wilson to do so (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 297). He trusted Wilson. Wilson told him about a “big fireproof house”, a “nice and dry” museum building in New York that would keep the Bundle “safe”, and he provided Wolf Chief with an oil painting of the Bundle by his brother Fred Wilson; Wolf Chief then sold the Bundle to Gilbert Wilson (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 298; Pepper and Wilson 1908, p. 28). He told Wilson the stories associated with the Bundle and how his father cured many people, adding “I am glad you are putting these things in a book—writing them down, for when men read them they will be interested” (Pepper and Wilson 1908, pp. 305–6). Even though he had converted to Christianity, and ceremonies were discouraged by the government and the church, Wolf Chief did not want the traditions to be forgotten nor the Bundle to be threatened by environmental, governmental, ecclesiastical, or cultural forces. His decision to sell the Bundle to someone who promised its safety and the documentation of knowledge associated with it leaves open the question of whether this was an act of resistance to oppression, or a transgression against clan rules, or both.12

Later, Wolf Chief became Wilson’s key informant and their relationship remained strong, so it would seem there was no ill will between them as a result of the sale. A few years after the sale, Wilson wrote to Heye to follow up on a promise he had made to Wolf Chief to provide a photograph of the Bundle “in its case”. There is no evidence Heye ever responded or sent the requested documentation.13 And then the letters to Heye ceased, for 24 years.

2.3. A New Deal

In 1932, during the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president, ushering in the “New Deal”. But it was not just a new deal for economic recovery, he ushered in new approaches to Native peoples and reservations, as well. Fine-Dare highlights Roosevelt’s influence on changing government attitudes and increasing interest in the preservation of cultural objects (Fine-Dare 2002, p. 66). In 1933, Roosevelt had hired John Collier, an activist for Native American rights, to head the Office of Indian Affairs. Collier initiated the “Indian New Deal”, turning “federal Indian policy away from the assimilationist approach it had taken for decades”, ending the attempts to eradicate Native languages and traditions. Instead, “Indian Office employees were instructed to encourage expressions of tribal culture. The moment the Hidatsa felt free to speak of their heritage again, their minds turned toward the Waterbuster Bundle” (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 314).

The Indian New Deal’s first major legislation was the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, which was aimed at reversing the allotment program, decreasing federal control over Indian affairs, and increasing Native American self-government. The Three Affiliated Tribes voted to create a tribal council under the act in 1936; both Arthur Mandan and Drags Wolf supported the act. Arthur Mandan was the first elected tribal Chairman, and Drags Wolf served on his council as representative of the Shell Creek community. Mandan served from 1936 to 1938 and helped draft the tribal constitution and established credit programs. In response to the severe drought of the Dust Bowl, he negotiated for programs to aid in recovery. Drags Wolf advocated for a local school so that children would not have to travel far from home. He served on the council from 1936 to 1941; two day schools were established in 1937 and 1938, keeping children closer to home in a time of boarding schools (Meyer 1977, p. 203). Before and after their elections to the council, these two tribal leaders were advocating for the Bundle’s return.

2.4. The Request

On 7 November 1934, four Hidatsa men set into motion the return of the Bundle via a letter from anthropologist Alfred Bowers to George Heye.14 Bowers writes, “I have in my office Drags Wolf, Bears Arm, Louie Wolf, and Arthur Mandan of the Hidatsa Indian Tribe. They have asked me as a community worker among them to write you in behalf of them relative to the Water Buster Medicine Bundle which Rev. G. L. Wilson secured of Wolf Chief a great many years ago”.15 He mentions the extreme drought which was destroying the crops, “and the older Indians feel that this is due to the sale and disposing of certain of their ritual paraphern[al]ia”. Then Bowers explains that Wolf Chief was not the owner of the Bundle, that he was Prairie Chicken Clan, and had no authority to sell. He adds that Wolf Chief was “thinking it was for the good of his own tribe” to turn over the Bundle. He concludes:

The Indians want these Bundles returned and are holding meetings this week to secure money to pay for their return, and they asked me to offer you $75.00 for the return of the Water Buster Bundles… I hope that you will bear in mind the fact that this property was secured from a person not entitled to sell; that these people will be very happy to get it back to their men.

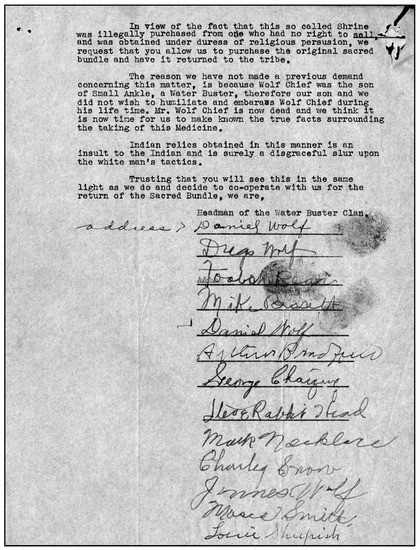

The following month, and after a series of letters to Heye that included a plea from an anthropologist, caution from a missionary, and rebuff from the museum director, Hidatsa Water Buster clan members wrote to Heye directly:

We are writing you concerning the return of a bundle of Medicine, sacred to us, the Water Buster Clan of the Hidatsa Indians of the Ft. Berthold Reservation … The Water Buster Clan still survives, and there are a great number of us. We resent the fact that this bundle was taken from us and from our people … Mr. Wolf Chief’s father, Small Ankle, was a member of the Clan during his life, it was his duty to be the keeper or care taker of this Medicine which hung in the Medicine Lodge. But while Small Ankle was a Water Buster, the bundle did not belong to him alone, but to the whole Clan … As no one but a Water Buster is supposed to care for or touch this sacred bundle, we feel that its loss is the cause of the many misfortunes which have been visited upon our people and the proper ritual for allaying this distress is attendant upon the possession of this Medicine. In view of the fact that this so called Shrine was illegally purchased from one who had no right to sell, and was obtained under duress of religious persu[a]sion, we request that you allow us to purchase the original sacred bundle and have it returned to the tribe.16

They go on to explain why they are making this request now, and not before:

The reason we have not made a previous demand concerning this matter, is because Wolf Chief was the son of Small Ankle, a Water Buster, therefore our son and we did not wish to humiliate and embarrass Wolf Chief during his life time. Mr. Wolf Chief is now dead and we think it is now time for us to make known the true facts surrounding the taking of this Medicine.

As noted above, the letter closes with “Trusting that you will see this in the same light as we do and decide to co-operate with us for the return of the Sacred Bundle”.17 Twelve clan members signed the document, including Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear. They also raised 400.00 with the intention to go to New York (Prairie Public News 2019).

In their request, three main things are established: the Bundle is an item of cultural patrimony belonging to the clan and no single person has the right to sell it; the loss of the Bundle resulted in hardships for their community and its return will alleviate them; and out of respect for Wolf Chief they waited until after his passing to make the request. In addition, they were not asking for the item to be gifted to them, they were willing to purchase it back.

After a Museum of the American Indian board meeting three months later, George Gustav Heye replied to their letter. He wrote addressing Daniel Wolf:

The Board of Trustees feel that they are under the deed of gift the custodians of all specimens in the Museum, the primary object of which is to preserve and keep safely for future generations anything pertaining to the American Indian and to have a place where the descendants of the old Indians can always see and study the objects that belonged to their forefathers. It is a good thing for you Indians to know that there is such a place in our country where the Indian possessions are taken care of and kept safely from fire and theft so their history may be known for future generations.18

He was speaking directly to the appropriate keepers of the Bundle, and telling them it was in better hands in the museum, and that somehow this served future generations of Indians. This was about preserving objects, not knowledge and lifeways.

Heye communicated a similar conclusion by the Board to John Collier: that they hold Native American objects in trust “for the public benefit, in order that they may be preserved and perpetually available for scientific research and for educational purposes, [so] they have no authority under their trusteeship to surrender any specimens”.19 Heye notes that in 28 years no claim for the Bundle had been made “or even hinted at on behalf of the Indians”. Then he explains the intentions of his museum and collection, that it is “dignified” and that he successfully endeavored “to found an institution where the objects which had been sacred to [Indians], but which were falling into disuse and in danger of destruction under modern conditions, could be preserved and given proper and understanding treatment in sympathetic surroundings”. He continues, “In all my personal experience with North American Indians, I have never had any question like this raised before and I am at a loss to understand the present request in view of the invariable record of friendliness of Indians everywhere to this Institution”. Although “in accord with and sympathetic to your attitude on Indian affairs and desire to promote the best interests of the Indians”, it is “always within the limits prescribed by their duties as Trustees” (ibid.). In other words: I am keeping these items faithfully and safely here in New York, and I cannot imagine why they would want them back; our mandate to keep safe these objects for the benefit of the public means we cannot relinquish them back to their makers. Again, he is suggesting that promoting the interests of Indians means keeping the items in the museum.

According to Mason (1958, p. 24), in his biography about Heye, the Water Buster clan’s medicine Bundle “was one of the most prominently displayed and greatly prized possessions of the Museum”. So how did the Water Buster clan change his mind?

2.5. The Negotiation

The Water Buster clan and Arthur Mandan garnered support from not only Bowers, but also the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the press. It is recognized that “public opinion and political pressure” on the Heye Foundation influenced the change in their position (McKeown 2013, p. 29). A Washington Post article in July of 1937 declared “protest has run like a wild dog across the plains” (The Washington Post 1937a). Fifteen days later, the Post reported the negotiations were stalled and the Hidatsa were on their way to Washington to demand its return (The Washington Post 1937b). At the same time, Arthur Mandan increased pressure on the museum by telling legislators and reporters the story of the Bundle (Heng 1998, p. 3).

The Hidatsa also appealed to John Collier, the new Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He and his staff wrote letters, and acted as intermediaries, in support of the tribe’s request. Some people were less in the public eye and laboring behind the scenes, like Department of the Interior field representative Louis Balsam who wrote letters advocating the return and interviewed Heye shortly before he decided to agree to an exchange. D’Arcy McNickle (Salish Kootenai) was not part of the letter writing campaign to Heye, but he was hired to work at the Office of Indian Affairs under Collier in 1936. According to his biographer Dorothy Parker, McNickle had participated in the Water Buster Bundle negotiations and considered his efforts to support the return a significant event in his life—so much so that the idea for the plot of his novel, Wind from an Enemy Sky (1988), originated with the Water Buster clan’s story (Schweninger 2009, p. 176).20

Tribal members traveled to DC and New York in 1937 to press their case, and the Office of Indian Affairs considered using “unfavorable publicity” to support them (Meyer 1977, p. 209). By December of that year Heye had changed his mind. The New York Times (1937, pp. 1–2) reported on it:

Delegations of Water Busters journeyed to Washington and New York to try to get their [Bundle] returned; but the Heye Foundation was adamant, on the theory that this would set a precedent that would soon empty the museum of all its Indian relics. The Indians even raised $250, a very large sum for them, in an effort to buy the Sacred Bundle, but they were unsuccessful … Today it was announced at the Office of Indian Affairs that the Heye Foundation had been persuaded to agree to an exchange.21

By late 1937, the negotiations for this “exchange” arrived at three main things that were emphasized in all the correspondence and resolutions: the Museum of the American Indian did not illegally obtain the Bundle so this was an act of “good will”, as reservation Superintendent Beyer and Collier called it;22 some equally authentic item must be provided in exchange; and, should the Bundle leave the Water Buster clan it must return back to the museum. The clan had offered cash to buy the Bundle back, but Heye would not accept the money, nor would he simply return it. Instead, he asked that the clan provide something in its place, something “authentically antique and valuable for its traditional Indian association”.23

The next month, the Board unanimously approved with this condition—and in their resolution they reiterate: “RESOLVED that this Board ratifies the negotiations of the Chairman with the Hon. John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and through him, with the Water Buster Clan of the Hidatsa Indians, for the exchange of the Medicine Bundle of the Hidatsa for some article authoritatively antique and valuable for its traditional Indian association”.24 Heye added after the resolution that,

By making this exchange, the Water Buster Clan may retain, as long as they desire, the possession of the Sacred Bundle in question, while at the same time we have in our possession some article authoritatively antique and valuable for its traditional Indian association which we can make the subject of study and scientific research. However, may I repeat what must always be understood that our participation in this exchange is in no way a recognition of any legal or moral right on the part of the Water Buster Clan to the Sacred Bundle and that we are making this exchange voluntarily as a gesture of friendship to the Indians and for the purpose of broadening our opportunities for study and research under the governing requirements of our Foundation Deed.

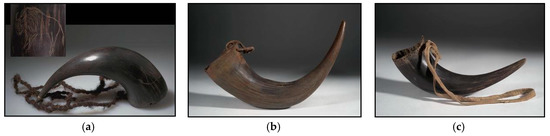

A few days later, on 6 December 1937, the Assistant to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Herrick, notified Heye that the Water Buster clan had selected a “Sacred Medicine Horn” to exchange for the Bundle, and “that the members of the Clan should be willing to part with such a treasure testifies, I think, to the sincerity of their desire to gain possession of the Sacred Bundle… The Indians will also present you with some sort of resolution”.25 After additional correspondence regarding the planning for travel and media attendance, the date for the exchange, to take place at the Museum of the American Indian, was set for 14 January 1938.

2.6. The Exchange

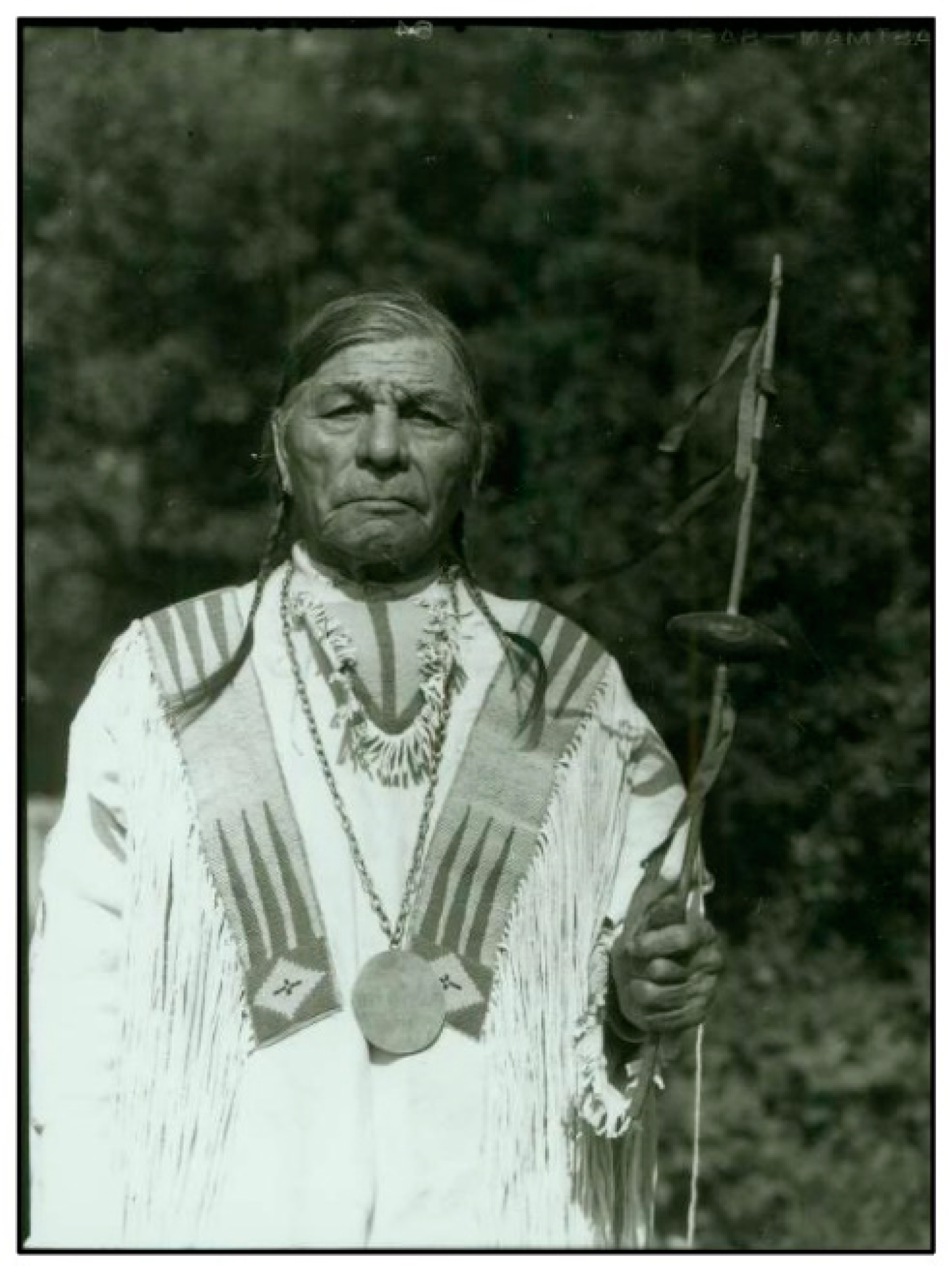

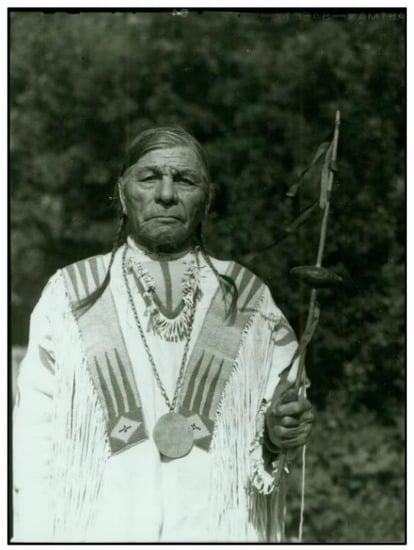

The Water Buster clan selected Drags Wolf, age 75, and Foolish Bear, 84, to represent them and receive the sacred Bundle from Heye in New York, with Arthur Mandan, 56, acting as interpreter. Arthur Mandan (1882–1955) was past the midpoint in his two year term as tribal chairman, which ended in August of 1938. He attended Carlisle Boarding school in Pennsylvania before returning to the reservation in 1908. He was an interpreter for anthropologist Alfred Bowers and for the Catholic Church, of which he was a member (Stevens 2003). Drags Wolf (1862–1943) lived off the reservation with a group led by his father Crow Flies High until they were forced to return to Fort Berthold in 1894. He “came of age while living in the traditional ways—hunting, trading and growing a few crops… many considered [him] to be among the last great Hidatsa chiefs” (Helm 2015). Foolish Bear (1854–1941) had been a scout under Bloody Knife with Custer against the Hidatsa’s traditional enemy, the Sioux. He was a survivor of Little Big Horn and had been a mail carrier between Forts Buford and Stevenson (Cox 2011).

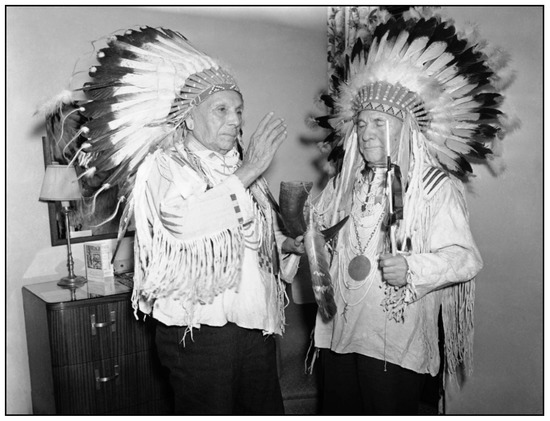

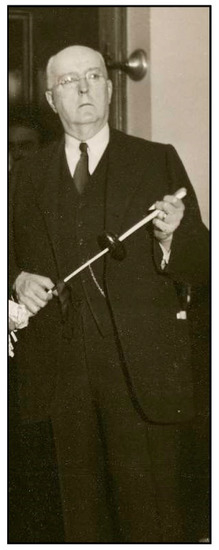

Foolish Bear, Drags Wolf, and Mandan arrived to Washington, DC, on 13 January 1938. Media documented their visit both to DC and to New York City. Dressed in dark suits, they visited the staff at the Office of Indian Affairs (Figure 2). They were dressed in full regalia for their meeting with President Roosevelt (Figure 3), during which they assured Roosevelt that should he run again, he will have the Indian vote (Bronx Home News 1938; see also New York Post 1938). They also expressed their gratitude for the return of the Bundle (Sylvester 1943, p. 14). A photo of this meeting was published in the newspaper at the time and is now a highly valued representation of tribal sovereignty for clan members. This was a significant communication of presidential support and a powerful acknowledgment of tribal leadership on the eve of their visit to the Museum of the American Indian.26

Figure 2.

Meeting with Indian Commissioner John Collier, who is holding the Sacred Buffalo Medicine Horn, on 13 January 1938. NMAI, SI (P12894).

Figure 3.

Meeting with President Roosevelt, 13 January 1938. NMAI, SI (P12908).

The following day, they traveled to New York City with staff from Collier’s office. It was four years since Drags Wolf and Arthur Mandan, along with Bears Arm and Louie Wolf, had walked into Alfred Bowers’ office asking for help. Their hosts had arranged for them to stay at the Hotel New Yorker in Midtown Manhattan. It was a week of travel from the open plains of North Dakota, to Washington, DC, to meet President Roosevelt. Opened in 1930 and with 43 stories, the New Yorker was the largest hotel in New York at the time, and its basement hosted the largest power plant in the country (Fletcher n.d.).

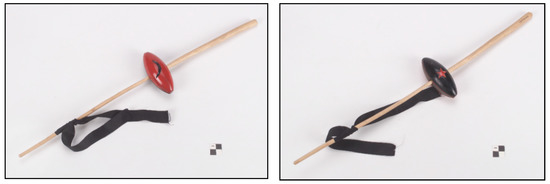

Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear were hungry as they arrived to their rooms on the thirty-fourth floor, and they did not feel right because they were “too far from the good earth” (Bronx Home News 1938). Despite the long journey, they were not tired and their humor shone through: they told one reporter that although Drags Wolf was here once before in 1913, Foolish Bear had never been and was interested in seeing a burlesque show (New York Post 1938) (which suggests they were not part of the delegation that visited in 1937). A photograph taken in the hotel that evening shows the men holding two objects they had brought for the exchange: the promised buffalo horn, and also a stone club (Figure 4). The stone club was never mentioned in letters with Heye or in any correspondence prior to the event.

Figure 4.

This photography shows Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf in their hotel room in New York before the ceremony at the MAI. They are holding the items they intended to exchange for the Bundle. Note how Drags Wolf orients the Stone Hammer, with narrower end upwards. ©1938 The Associated Press (AP380113028).

The next day, Foolish Bear, Drags Wolf, and Mandan arrived at the Museum of the American Indian dressed in full regalia (Figure 5). However, as one reporter noted, “the clan’s emissaries were so harassed by photographers and reporters that they left behind in their room at the Hotel New Yorker the sacred buffalo horn which they had brought to trade for the bundle” (New York Herald Tribune 1938). They did remember the stone club, as evidenced in a photograph in which Heye is standing next to Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear next to a podium, holding the club (upside down) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

The exchange ceremony, 14 January 1938, at the Museum of the American Indian. From left: William Zimmerman (Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs), Arthur Mandan, Drags Wolf, Foolish Bear, George Heye, and Thomas Roberts (MAI treasurer). NMAI, SI (P12910, detail).

Figure 6.

Later during the exchange, Heye holding the Stone Hammer Society club. NMAI, SI (P12915, detail).

During the ceremony of exchange, the Bundle was laid out, uncovered, on a table. This must have been difficult for Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf, to have a sacred item exposed like this. Only one reporter mentioned the moment when the Bundle was uncovered, and their reaction: “for the first time Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf came near losing their composure … They started forward, but checked themselves, again assuming their stony expressions” (New York Herald Tribune 1938). A group of people surrounded Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf during the exchange, and Mandan translated between them and Heye. William Zimmerman, Assistant Commissioner in the Office of Indian Affairs, was present “to show that the ideas have changed… it is now the policy of the Government to encourage Indian customs and legends” (The New York Sun 1938). There were speeches, elements of the Bundle were held aloft between Heye and Foolish Bear, and the press took lots of photographs.

After the ceremony concluded, there were interviews and more photographs. Then Foolish Bear, Drags Wolf, and Mandan returned to the hotel. Museum staff Kenneth Miller also went to the hotel to retrieve the Sacred Buffalo Medicine Horn and clan resolutions that had been left behind (New York Herald Tribune 1938). A flurry of appreciative letters amongst all parties followed, including between George Heye and Daniel Wolf, who was now the keeper of the Bundle. Heye wrote to Wolf, “I liked the medicine horn and the stone club that your delegates brought to me, and I highly prize the resolutions that accompanied them”.27

When Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear left New York City, they did not have the Bundle in their possession. Museum records indicate that the Bundle was shipped to Minot, North Dakota the day after the ceremony. Foolish Bear, Drags Wolf, and Arthur Mandan traveled home by train, retrieved the Bundle in Minot, ND on 21 January, and arrived back to the Fort Berthold reservation the same day.28 To ensure safe and dry housing for the Bundle, Marilyn Hudson recalled that the Bureau of Indian Affairs provided 500.00 for community members to build a “little house” for it in Elbowoods. Even though the structure was later moved to the land of the next custodian, and now the Bundle is housed elsewhere with the current keeper, the “little house” still stands today (Figure 7).29 By all accounts—from community members, to the weather service, to the newspapers—when the Bundle returned, the rains returned.

Figure 7.

The structure funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to house the Bundle when it returned home in 1938. Photo courtesy of Marilyn Hudson, October 2019.

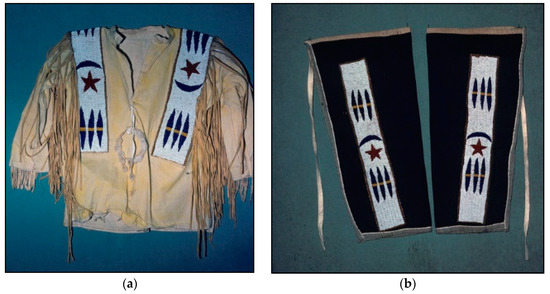

2.7. Objects of Resistance

The “Sacred Medicine Horn” was referenced throughout the negotiations and in the resolution by the clan members. But, Drags Wolf also brought a stone club associated with the Stone Hammer society. The most interesting thing to me was that Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf had forgotten the promised exchange items at the hotel (the buffalo horn and resolution) when they left that morning. For a long time, I thought they left all of the items at the hotel, and that they had orchestrated the image of a one way return for the cameras… until I saw the photographs in the archives. Heye was holding the Stone Hammer at the podium during the exchange (Figure 7). Perhaps it was a deliberate choice to leave the promised items behind and bring the stone club, or perhaps it was just an oversight.

In any case, these exchanged items were not in the same category as the Bundle—they were not owned by the clan as a whole. They were individual possessions that Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf had the right to give, and it is very possible they were created specifically for the museum exchange. In talking to MHA Nation community members, there is a general sense that the Water Busters pulled one over on Heye, in that the items given to the museum were not of the same ceremonial value as the Bundle, which was what the museum had intended. Because, of course, items like that are not meant to be separated from the clan or housed in a museum.

Along similar lines, in a piece for Prairie Public News commemorating the week of the return of the Bundle, these objects were described as “a roughed up stone hammer and a sun-bleached bison horn stuffed with sage” (Helm 2019, n.d.). On examination of the horn, it neither appeared sun bleached nor was there evidence of sage; nor did sage appear to be in the horn when Foolish Bear had it in the hotel the night before the exchange (Figure 4) or in the photograph of him at the BIA offices in DC (Figure 2). According to NMAI staff, the horn has never been studied, which was the intention of the exchange (recall Heye asking for something that would be “authoritatively antique and valuable for its traditional Indian association which we can make the subject of study and scientific research”). The museum never produced an image of the horn, nor has it ever been published. So a turn to the objects themselves provides some new insight.

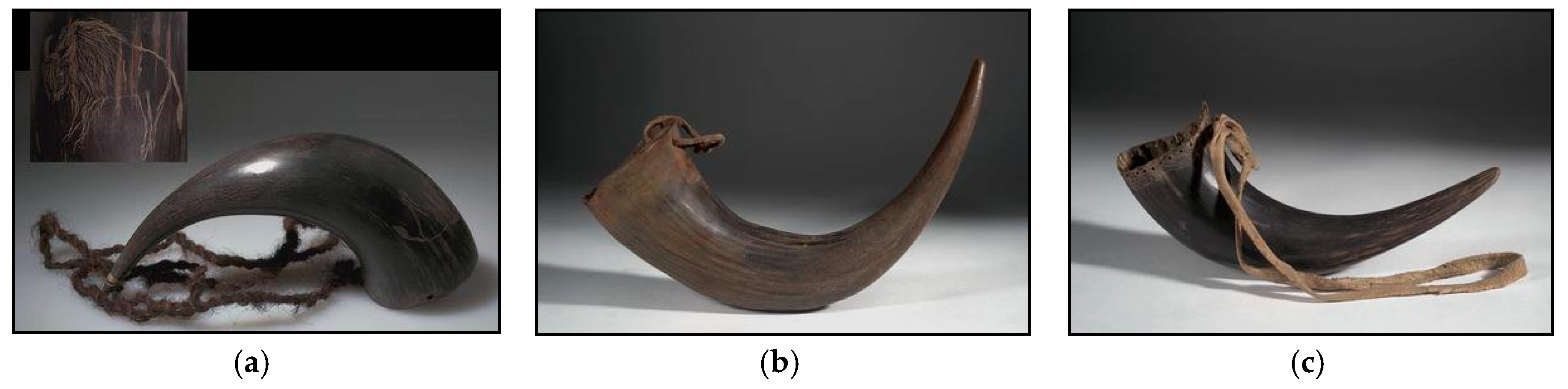

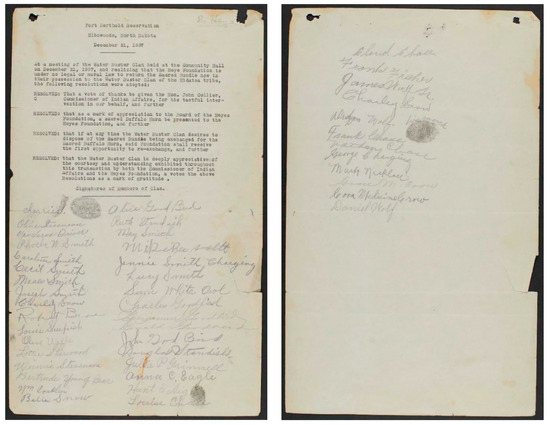

At the end of December in 1937, the Water Buster clan met in Elbowoods, North Dakota, to develop the resolutions they promised as part of the exchange with Heye. The document is now in the archives of the National Museum of the American Indian (Figure 8). It states:

At a meeting of the Water Buster Clan held at the Community Hall on 21 December 1937, and realizing that the Heye Foundation is under no legal or moral law to return the Sacred Bundle now in their possession to the Water Buster Clan of the Hidatsa Tribe, the following resolutions were adopted:

RESOLVED: that a vote of thanks be given to Hon. John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, for his tactful intervention on our behalf, and further

RESOLVED: that as a mark of appreciation to the Board of the Heyes [sic] Foundation, a sacred Buffalo Horn be presented to the Heyes Foundation, and further

RESOLVED: that if at any time the Water Buster Clan desires to dispose of the Sacred Bundle being exchanged for the Sacred Buffalo Horn, said Foundation shall receive the first opportunity to re-exchange, and further

RESOLVED: that the Water Buster Clan is deeply appreciative of the courtesy and understanding exhibited throughout this transaction by both the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Heye Foundation, & votes the above Resolutions as a mark of gratitude.

Figure 8.

Water Buster Clan resolutions passed 21 December 1937 in Elbowoods, ND; MAI/Heye Foundation Records, Box 321 Folder 11; NMAI Archive Center, SI.

Forty-five members of the Water Buster clan signed the document, including one person who had not been supportive when they first made the request.

The day of the exchange, through interpretation by Mandan, Foolish Bear provided the museum with an account of how the horn had been a part of his family for three generations, and had provided his grandfather, father, and himself protection and healing (Figure 9). The same account that was recorded in the museum catalog record was also printed in the Bureau of Indian Affairs circular, Indians at Work, the following March of 1938. The account closes with “it is the most valued possession of any member of the clan” (Foolish Bear 1938). This phrasing was similar to Assistant Commissioner Herrick’s language in a telegram to Heye: “horn is veritably old and regarded as clans [sic] most valuable remaining possession”.30

Figure 9.

Hidatsa horn. NMAI, SI (197237.000). Photo by author.

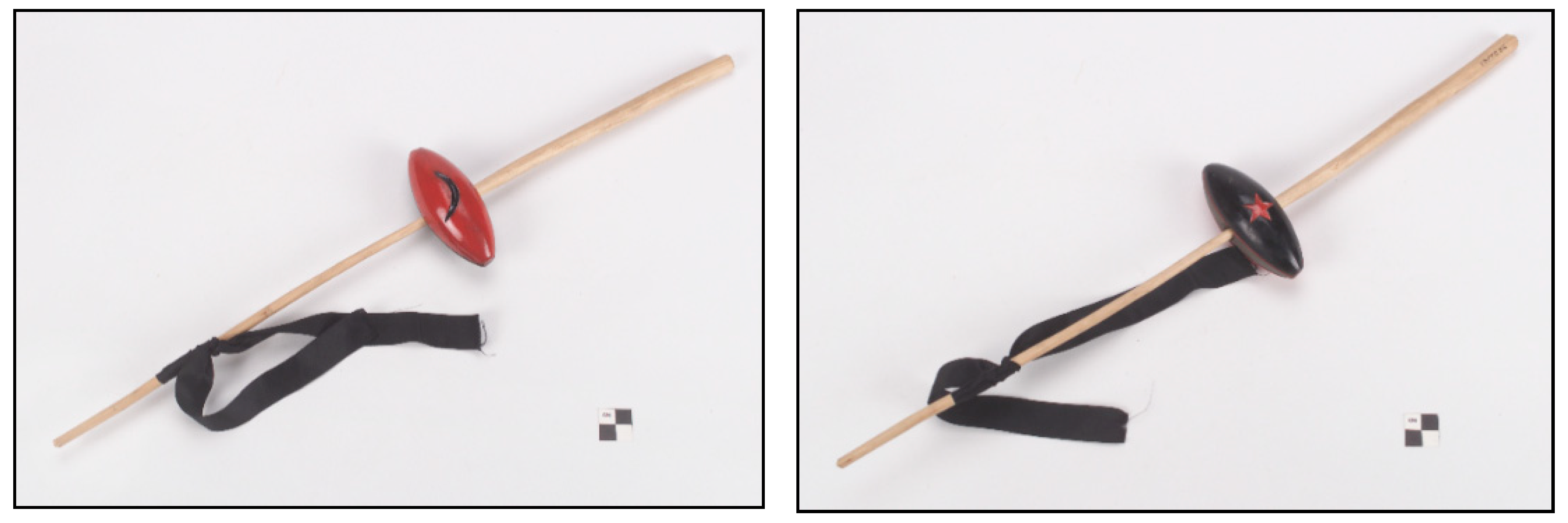

In various sources, this object has been called a “buffalo horn” (New York World Telegram 1938), “powder horn” (Infinity of Nations 2019), “buffalo medicine horn” (Mason 1958, p. 24) and a “sun-bleached bison horn stuffed with sage” (Prairie Public News 2019). As noted earlier, upon examination the horn does not appear sun bleached, nor is there sage inside. It had little modification but for a hole through which a feather is attached. The feather is identified in the records to be from an eagle; it looks to be a Golden Eagle tail feather.31

I could not find any accounts of sacred buffalo medicine horns in literature or museum collections searches relating to the Hidatsa or the Three Affiliated Tribes. So I reached out to an independent collections research specialist, Mike Cowdrey, for assistance. In his first assessment and without knowing the context of the buffalo horn, he associated it with similar items in collections that tend to be functional and not sacred—horns for drinking cups or carried on belts during war expeditions (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

(a) Flathead drinking cup, 1934 (50.2/3691); (b) Shoshoni drinking cup, 1901 (50/2332); (c) Shoshoni drinking cup with strap, 1901 (50/2386). Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

It was the eagle feather that made this piece stand out to Cowdrey, and when placed in context of the 1938 repatriation, he reconsidered the meaning of the feather and the horn. The eagle feather attachment associates it with war, a center-tail feather holds particular meaning in the context of this particular Bundle, and the feather was worth a good horse on the Plains. In other words, Foolish Bear had provided to the museum a significant “inheritance” that would have gone to his descendants.32

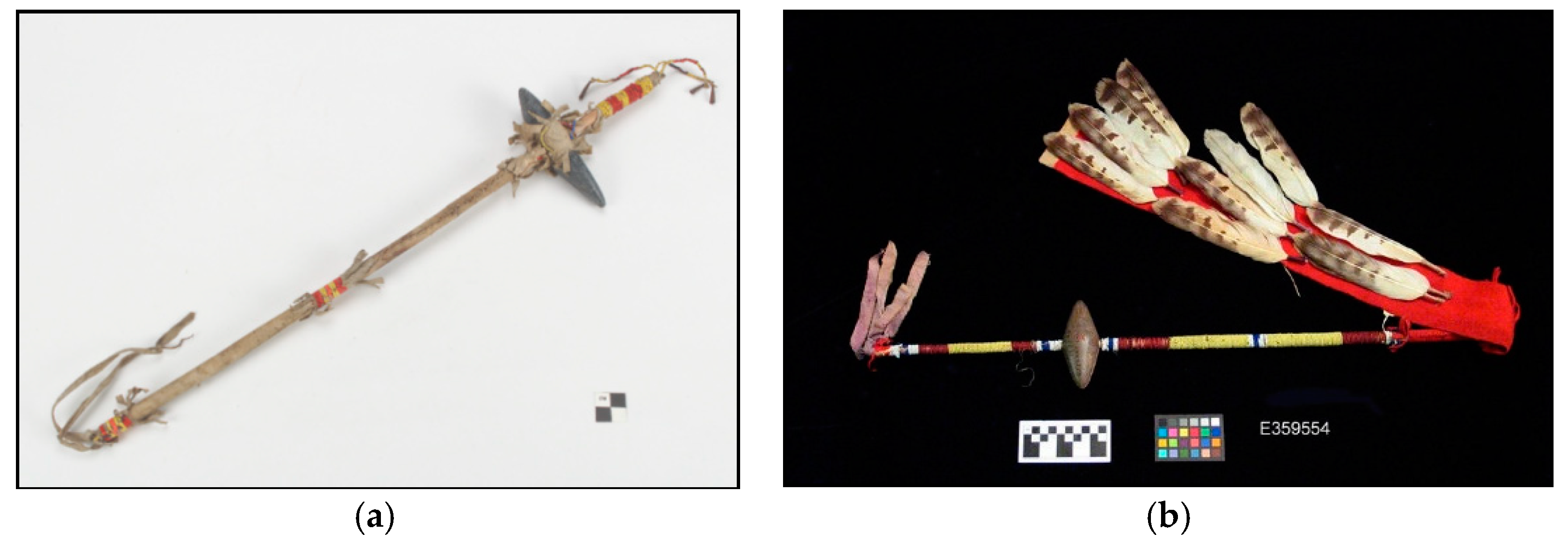

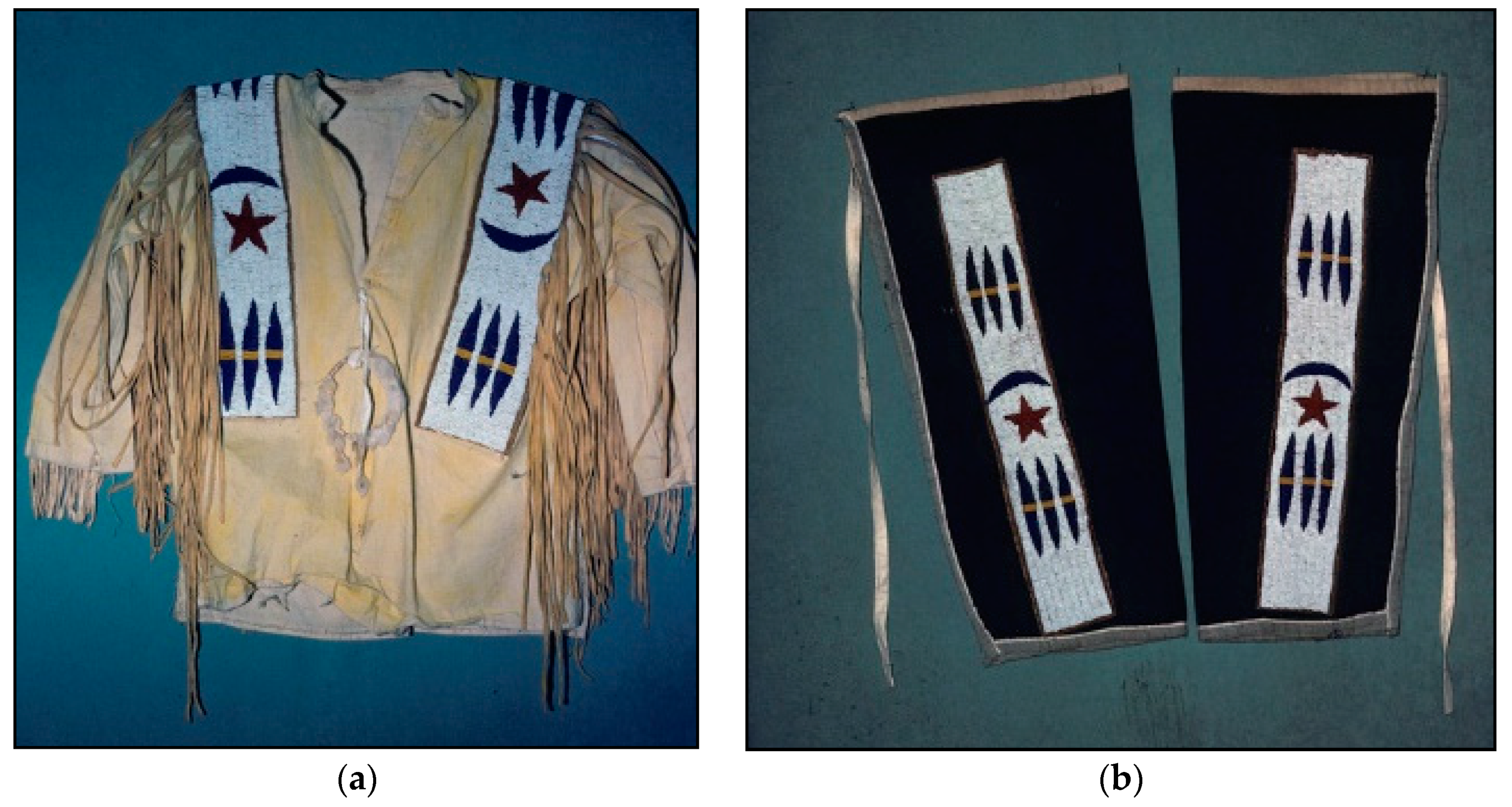

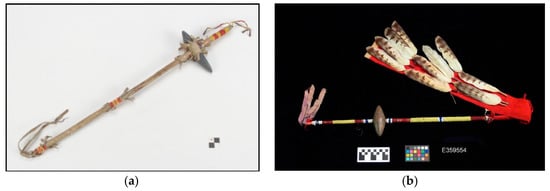

Drags Wolf also brought an item: a stone club, associated with the Stone Hammer Society (Figure 11).33 Unlike the “Sacred Buffalo Medicine Horn”, there were plenty of sources to compare this item to. There are images of other stone clubs from this society in museum collections, and the Stone Hammer Society is referenced in (Bowers 1992, pp. 180–81; Lowie 1913, 1917; Densmore 1923, vol. 80, pp. 113–20) and Wilson cited in (Gilman and Schneider 1987, pp. 90–92). It is the first age-grade society Hidatsa boys enter into. What seems particularly significant to me is, as a choice among all other objects that Drags Wolf may have made for the exchange, he chose an object associated with both Wilson and Wolf Chief. The person who had provided the accounts of the Stone Hammer Society to both Wilson and Bowers, was Wolf Chief.

Figure 11.

Hidatsa Dance Wand/Baton, front and back. NMAI, SI (197236.000). Photo by NMAI Photo Services. Note: Not only did Heye hold this hammer upside down at the exchange ceremony, the NMAI photographed the club upside down as well.

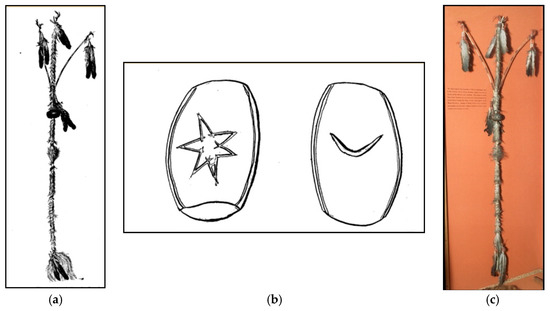

In most examples of the Stone Hammer Society club, there are these features: a stone hafted on a slender wooden shaft, one side has a moon symbol and the other side an image of a star or sun, and a material is tied to the shaft and hangs from it. This material can be horse hair (MHS 9598.6, as cited in (Gilman and Schneider 1987, p. 90), quill wrapped hide strips (NMAI 218508.000), or cloth or wood with feathers attached (NMNH E359554-0; AMNH 50.1/4342) (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Variably, the shafts are wrapped in hide, beads, quills, or feathers. In contrast, the stone club offered in the exchange was plain: a single ribbon tied around the shaft, with the moon and sun images carved into the two sides of a stone painted red and black, and no adornment on the shaft. There is another stone club in a photograph that also has no adornment on the shaft from 1942, but it does have more than one simple ribbon attached to the shaft (Figure 14).

Figure 12.

(a) Hidatsa Dance Wand/Baton, NMAI, SI (218508.000). Photo by NMAI Photo Services. (b) Hidatsa Stone Hammer Society Wand, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, collected by Frances Densmore on or before 1915 and accessioned to the museum in 1931 (E359554-0).

Figure 13.

(a,b) Drawings of Stone Hammer Society wand by Robert H. Lowie (Lowie 1913, pp. 240–41); (c) Same Stone Hammer on display at the American Museum of Natural History (50.1/4342). Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

Figure 14.

Drags Wolf with what looks to be a Stone Hammer Society stone club in 1942. State Historical Society of North Dakota (00039-0009).

It is clear in examining this item that it was made quickly, and simply. It was most likely made specifically for the exchange with Heye. Beyond the nature of the construction of this stone club, according to Bowers “the Hidatsa do not consider the men’s societies as sacred, and speak freely of their participation in society activities… unlike the sacred ceremonies which are never discussed except under rigidly prescribed conditions” (Bowers 1992, p. 175).34 This, too, is significant in that it suggests that this kind of object was not sacred, it was acceptable to share knowledge about it, and it was a more appropriate kind of item to place in a museum.

The catalog record for Drags Wolf’s stone club includes the story of the sun and the moon and how the Stone Hammer Society was created. The account concludes,

This Society was to be the first stage for other Societies which would follow. It was called the Stone Club and included as members boys whose ages range from approximately 10 to 17 years. [The son of a Hidatsa maiden and the Moon] warned that the Society should continue through each succeeding generation for when it is discontinued or forgotten, the end of the world is at hand. The symbol of this society is a stone, one side of which is painted red in honor of his brother the Sun, and the reverse side of which is black, representing his father the Moon. These colors show the rising and setting of the two Orbs. On the side of the sun, is carved a star and on the black side, is carved the Moon. Two lines or grooves run around the stone from tip to tip, these indicated the paths of the Sun and Moon.

From the 1930s to today, the society has not been forgotten—as evidenced in Native arts. Not only are there examples of associated regalia from the mid-20th century (Figure 15), but there is a 21st century dress by Lauren Good Day Giago (Arikara/Hidatsa/Blackfeet/Plains Cree) that was recently accessioned into the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian (Figure 16). The piece, made in 2012 and titled Warrior’s Story, Honoring Grandpa Blue Bird, “tells the story of her grandfather’s journey as a warrior in the Stone Hammer Society and his service in Vietnam through intricate imagery and beadwork. The dress, like much of her artwork, serves as a vessel for sharing stories and preserving history in a non-traditional format” (BWW News Desk 2013).

Figure 15.

Child’s (a) shirt (32971) and (b) leggings (32961) with Stone Hammer Society symbols. Copyright University of Colorado Museum of Natural History.

Figure 16.

Lauren Good Day Giago dress accessioned by the NMAI, which includes a drawing of a Stone Hammer below the right shoulder, with wrapped shaft and feathers hanging. A Warrior’s Story, Honoring Grandpa Blue Bird, 2012. NMAI, SI (268817.000). Photo by R.A. Whiteside, NMAI Photo Services.

2.8. The (Long) Return Home

It took twenty-eight years of patience and four years of persistence by the Water Buster clan, along with the intervention of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, for Heye and the Museum of the American Indian board to agree to return the medicine Bundle to the clan. But the story did not end there. More items associated with the Bundle were returned over fifty years later, shortly before the Museum of the American Indian transitioned into the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian. A remaining item was returned in 2004—70 years after the original request.

Jacknis notes in his account of the NMAI’s history that “unfortunately, the best example of Heye’s progressive behavior was not what it appeared to be. In 1938, he agreed to repatriate a medicine bundle to the Water Buster Clan of the Hidatsa. It seems, however, that Heye could not bear to part with it… In 1977 the museum returned what remained of the original. One might note that if Heye may have been a little more disrespectful than most, such practices were relatively common at the time” (Jacknis 2006, p. 533).35 Leaving aside the characterization of Heye’s deception as just a sign of the times, while the remaining contents were found in 1977 during an audit required by the New York City attorney general’s office, the staff did not actually alert the clan until 1989. What they had found a decade earlier was a box, hidden under stairs in the back of a gallery containing items from the Bundle with no catalog numbers. This was later determined to be a deliberate deceit in an internal investigation within the museum.36 Carpenter (2005, p. 106) notes that Heye did something “suspect” in his cataloging of the Bundle; McKeown (2013) notes that he may have “intentionally miscataloged” the items.

In September of 1989, MAI curator Gary Galante was asked to determine if the Bundle was still being used by the Hidatsa clan and provide a recommendation of what to do about the Bundle items that had remained in the museum’s collection. He visited Fort Berthold Reservation that November, and learned from Water Buster clan member Ed Lone Fight the continuing importance of the Bundle to the Water Buster clan. Gerard Baker assured him that there was also renewed interest among younger generations in these traditions. Galante also learned that the Water Buster clan had been commemorating the Bundle’s return every year since 1938 with a powwow.

On 18 November 1989, President George H. Bush signed the legislation that created the NMAI as part of the Smithsonian. On 18 May 1990, the items in the box were returned at Gary Galante’s recommendation. The return was still not complete. In July of 2001, Byron Grinnell, assistant to then Bundle keeper Roy Bird Bear, contacted the NMAI’s Repatriation Department to inquire whether any additional items from the Bundle may still be in the museum’s possession. Dorene Red Cloud (Oglala Lakota) responded and began a search. Byron Grinnell visited the NMAI in 2003, and with the assistance of Terry Snowball (Prairie Band Potawatomi/Wisconsin Ho-Chunk) from the Repatriation Department, identified the missing item in the collection and filed a request for repatriation. It was returned in 2004.

In 2019, Red Cloud reflected on her role the return of the Water Buster Bundle, saying her job was to be a kind of detective seeking information to support claims, and that the “main objective and goals is to heal, and to make something positive happen”. She continued,

It’s historic—the Three Affiliated, they were on it—[saying] “Hey, this is ours”. They followed through. These things do take time. Sometimes it’s just in how the greater picture works, in how the creator works. There’s a timing for things. I just played a little minor role, but I’m glad to know that it got completed … The generation after all this historic trauma has come along, and they are renewing ceremonies or just picking up the thread and going from there … these bundles are there for them. They’re meant to go home and they’re meant to be with these newer generations who are a part of it. And I think it’s a healing process. It’s like taking a history that you maybe felt victimized by, and empowering people”.37

3. Discussion

3.1. Agency in the Exchange

The current Bundle keeper told me he heard that when their community was experiencing the severe drought a group of men sat down over coffee to decide what to do, and the decision to request the return of the Bundle was made “before they poured the cream”. Although the return of the Water Buster Bundle is often called a repatriation, at the time this term was never used; it was expressly called an “exchange” and what I have highlighted here: a “negotiation”. When required to leave something behind in its place, Foolish Bear and Drags Wolf provided objects that were individually owned, simply and perhaps recently or quickly made, and not inappropriate for the public to view or learn about; the associated documentation and knowledge they provided was not sacred. All of this is to say, that through a letter writing campaign and marshalling public pressure and federal allies, they achieved something unheard of at the time and made it very public. In so doing, they demonstrated to America the continuity and vitality of Native traditions and Native peoples, and they safeguarded the wellbeing of their people.

3.2. In the Spirit of Visual Sovereignty

In her articulation of visual sovereignty, Raheja (2007, p. 1161) encourages us to locate and advocate “for indigenous cultural and political power both within and outside of Western legal jurisprudence. The visual… is a germinal and exciting site for exploring how sovereignty is a creative act of self-representation that has the potential to both undermine stereotypes of indigenous peoples and to strengthen what Robert Warrior has called the ‘intellectual health’ of communities in the wake of genocide and colonialism”. Although Mandan, Drags Wolf, and Foolish Bear were not creating the visual representations of themselves and the exchange (and the Bundle was exposed and photographed against their will during the exchange at the Museum of the American Indian), they did engage with media and influence visual representations of themselves in a deliberate way to place pressure on Heye and to press their case.

During the exchange, Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear endured the repeated speeches for the cameras and crowd, they endured the exposure of the Bundle, they endured the interviews. They did this for the return of the Bundle. And all the while they carefully attended to their image and the story being reproduced for the public, knowing as is often the case that they were not just representing Water Buster, or Hidatsa, but that for many people they would stand in for all Native Americans at a time when people assumed Native traditions and maybe even Native peoples themselves were destined to disappear.

They did not just say we are here; they communicated we are here, we are strong and we advocate for our rights, we practice our traditions, and this Bundle matters. It has value not just as something “veritably old” to preserve in a museum, but as something that is vital to our lives today. One series of photographs shows Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear leaving the museum, feather bonnets in hand as they look up and see the photographer in the distance, and the next photograph their feather bonnets are on. The photographs of their travels on the east coast include them in suits when speaking with Indian Affairs staff, dressed from the waist up in regalia at the hotel, and in full regalia with President Roosevelt and George Heye. At each stage, they were carefully managing the images captured, projecting strength and pride in their cultural heritage. Alongside them was Arthur Mandan, whose tailored suit also signified to the public, we are modern, too.

3.3. Repatriation and (This Community’s) Health and Wellbeing

The Elbowoods Health Center on the Fort Berthold reservation is named after the main town that was inundated by the Garrison Dam. As you walk into this health clinic you enter a rotunda with a series of displays in glass cases. One exhibit is about bundles and healing. It lists who the different bundle keepers are in the community and explains what to bring to the keeper. This display places bundles and their associated ceremonies at the center of understandings about community health. The text explains,

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara have always practiced their traditional ways of healing. Ceremonies for different types of healing were conducted by those individuals who had either earned or been given the right to perform them. For a time in the 1800s and 1900s, federal policy forbade Native American ceremonial practices. Government agents and others encouraged people to burn their medicine bundles, which were used for healing and the well being of the people. Some tribal members did burn their bundles; others did not. Regardless of their spiritual practices being outlawed, some Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara clandestinely carried on their traditional ways of praying. Today, there are individuals on the Fort Berthold Reservation who continue to practice the healing traditions of their tribes. Some have tribal or clan medicine bundles; others have individual or personal bundles.

The Water Buster Bundle and its current keeper, Delvin Driver, Sr., figure prominently in the display.

Tribal historian Calvin Grinnell, who is a member of the Water Buster clan, describes the responsibility of a bundle keeper as “a daunting responsibility. It’s like being a doctor—you’re on call 24 h a day sometimes. People want to pray to [the bundle] or they want help from it”.38 Grinnell emphasizes how the Bundle has been used to heal and protect community members in the past and today. The celebration of its coming home has continued annually since its return (MHA Nation 2019b). The January 2018 Hidatsa Herald headline was “Miri Baadi Naagi Maa Aru Nishuc ‘Water Buster Celebrates’”. The first day of the commemoration was a “Clan Bundle Keepers feed” and community celebration, the second day a powwow.

The current Bundle keeper is called to pray, to conduct seasonal ceremonies, and to do blessings at important events. He does this, he explains, for the whole community—for all three tribes, the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara. The clan has prayed for all three tribes ever since they came together in the 1860s, “and we’re still together to this day”.39 The Bundle did alleviate some of the hardship in their community when it returned home, and it continues to be central to community wellbeing today. The people, their language, and the Bundle carry on.

4. Conclusions

I recently answered my phone and heard, “Jen! Repatriation works!” “Calvin, what’s on your mind?” I replied, smiling at his enthusiasm. Calvin Grinnell, MHA Nation tribal historian and Water Buster clan member, had visited the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History where I work for a repatriation consultation and later the return of sacred objects to the MHA Nation five years ago. He wanted to tell me the fate of some of the items that had been returned, and that they were being used in ceremony today.

Unlike during the negotiations in the exchange for the Water Buster Bundle, today NAGPRA provides a structure and process that both museums and tribes can rely on to facilitate repatriation. Since our first consultation, Calvin Grinnell and I have worked together on many projects over the years (Shannon 2017a, 2017b). In fact, I often advocate that repatriation is an excellent foundation for research (Shannon 2019a). Doing the work of repatriation as a museum professional can be very rewarding, and not just from a social justice perspective. Speaking as a curator who hosts repatriation consultations, the coming together to do this work creates meaningful relationships, opens up new avenues for collaborative research, and is transforming how my students and staff and I see the purpose of our work in museums and the potential for museums to play a role in support of Native American communities (Shannon 2017a, 2019a).

Perspectives and attitudes are changing about the potential for museum professionals and Native communities to work together, and towards common goals—a stark contrast to the “long return” the Water Buster clan members endured. Frank Weasel Head (2015, p. 181) concluded his account about the return of Blackfoot medicine bundles from the Glenbow Museum by noting that the museum people—who at first they “regarded with suspicion”—are now allies and friends. Jisgang (Nika Collison) (Haida), Curator of the Haida Gwaii Museum, writes, “whether we are bringing home an ancestor’s remains, or repatriating knowledge, the healing is visible on the faces of our community members… the people working in [museums] today (for the most part) did not steal our relative’s bones or hide our cultural heritage away. Like us, they’ve inherited the right and responsibility to do things differently—to make things right” (Krmpotich and Peers 2013, p. 24). Sonya Atalay (Anishinabe-Ojibwe) captures the potential of this shared labor to make things right, like John Collier and Louis Balsam supporting the return, or Gary Galante and Dorene Red Cloud working to bring the long return to a close. Atalay (2019, p. 88) explains that “what those who engage in the work of reclaiming and repatriation are witnessing is an unfolding of the future in new and exciting ways. It’s a future in which Indigenous people engage in the work of reclaiming together with museum professionals and archaeologists, working in partnership to transform institutions—how they work, their goals, and their methods, while at the same time contributing to healing their communities”. So let us do things differently, work in partnership, and transform institutions.

Funding

This research received funding from the University of Colorado.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful for the guidance provided by Calvin Grinnell, Elijah Benson, Terry Snowball, Emma Noffsinger, Michael Pahn, Cynthia Chavez Lamar, and Delvin Driver Sr. Special thanks for detailed feedback, additional sources, and line edits from Marilyn Hudson, Mike Cowdrey, Dorene Red Cloud, and Lauren Sieg. Thanks to Sonya Atalay, Indrek Park, and Candace Greene for recommending related material. This research was funded in part by a University of Colorado Boulder Outreach Award. I am indebted to Craig Howe, my supervisor in 1999 when I first started working at the National Museum of the American Indian, for his instruction to find first person, Native voices in the archives and to highlight them in telling Native histories. I could have cited countless sources that discuss colonialism and religious oppression during this time, but as much as possible I wanted to cite people from the community and highlight their lived experience and testimony.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alivizatou, Marilena. 2012. Intangible Heritage and the Museum: New Perspectives on Cultural Preservation. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, Sonya. 2006. No Sense of the Struggle: Creating a Context for Survivance at the NMAI. The American Indian Quarterly 30: 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Sonya. 2019. Braiding Strands of Wellness: How Repatriation Contributes to Healing through Embodied Practice and Storywork. Public Historian 41: 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bad Wound, Barbara. 1999. Millennial Countdown—The 1930s. Indian Country Today, November 24. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, Terri. 1988. For the Taking: The Garrison Dam and the Tribal Taking Area. Available online: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/taking-garrison-dam-and-tribal-taking-area (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Bowers, Alfred W. 1992. Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organization. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronx Home News. 1938. Two North Dakota Indians Come to New York to Retrieve Sacred Relics Lodged on Heights. Bronx Home News, January 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchac, Margaret M. 2018. Broken Chains of Custody: Possessing, Dispossessing, and Repossessing Lost Wampum Belts. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 162: 56–105. [Google Scholar]

- BWW News Desk. 2013. Artist Lauren Good Day Giago Builds Platform for Native Art. Available online: https://www.broadwayworld.com/article/Artist-Lauren-Good-Day-Giago-Builds-Platform-for-Native-Art-20130625 (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Carpenter, Edmund. 2005. Two Essays: Chief and Greed, 2nd ed. North Andover: Persimmon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, Chip. 2017. Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip. 2012. The Work of Repatriation in Indian Country. Human Organization 71: 278–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, Rachel Maxson, and Jami Powell. 2011. The Repatriation of Culturally Unidentifiable Human Remains. Museum Management and Curatorship 26: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]