Abstract

The art history of Native North America built its corpus through considerations of “art-by-appropriation,” referring to selections of historically produced objects reconsidered as art, due to their artful properties, in addition to “art-by-intention,” referring to the work by known artists intended for the art market. The work of Siyosapa, a Hunkpapa/Yanktonai holy man active at Fort Peck, Montana during the 1880s and 1890s, troubles these distinctions with his painted drums and muslin paintings featuring the Sun Dance sold to figures of colonial authority: Military officers, agency officials, and others. This essay reassembles the corpus of his work through the analysis of documentary and collections records. In their unattributed state, some of his creations proved very influential during early attempts by art museums to define American Indian art within a modernist, twentieth century sense of world art history. However, after reestablishing Siyosapa’s agency in the creation and deployment of his drums and paintings, a far more complicated story emerges. While seemly offering “tourist art” or “market art,” his works also resemble diplomatic presentations, and represent material representations of his spiritual powers.

Keywords:

Sioux; Yanktonai; Hunkpapa; Fort Peck; drum; Sun Dance; painting; American Indian art; Native American art 1. Art, Intention, and Appropriation

Within any over-arching narrative of Native American art history, there remains a hidden watershed acknowledged, analyzed, but not yet reconciled (Igloliorte and Taunton 2017; Penney 1989, p. 9). It is located somewhere between “historic” and “contemporary” Native arts. It lies near the time-worn distinctions between art and artifact. Often, but not always, those distinctions refer to objects whose authorial source is clear versus those where any individual creator remains unknown. It lies squarely between what anthropologist Maruška Svašek characterized as “art-by-intention” versus “art-by-appropriation” (Svašek 2007, pp. 11–12). If art-by-appropriation refers to an after-the-fact reassessment of an object—whether by a connoisseur, collector, or curator—art-by-intention privileges authorial agency, the intention of an artist to deploy his or her creations within a museum/gallery/commodity-driven art world.

Art-by-appropriation, of course, is an outgrowth of the twentieth century modernist reinvention of “art” as a material category and a practice. It depends upon retroactive generalizations about cultural relativity: Everyone makes art (of some sort); art is a fundamental attribute of humanity. It requires the scaffolding of modernity to stand: This has always been true; we just have not seen it before; our seeing it now is evidence of our progress from then. For this kind of rubric, art-by-appropriation is corrective endeavor. It remediates ethnocentric judgments of the past that failed to recognize the artful cultural practices and productions that were once considered (by pre-moderns) to be primitive and inferior to the scope of art and civilization. This fluid and adaptable twentieth century redefinition of art also challenged aesthetic and cultural authorities, opening the door to consideration of more diverse and inclusive arts practices and products within the museum and the academy. An art history of American Indian art is inconceivable without such a turn. Art museums today, with their multi-cultural formulations, bank on such redefinitions with art-as-self-evident presentations of diverse North American objects in their galleries. Museums present Native art as evidence of a world art common to all humanity. The flaws in this reasoning, clustering around considerations of intentionality and authority, led to the 1990 Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, when Native communities asserted further redefinitions of objects in art museums, forced by circumstance into legalistic definitions of “sacred object,” “cultural patrimony,” or “associated funerary object.”

Art-by-intention would require an awareness of and engagement with the gallery/museum/commodity-driven art world, rather than retrofitted reassessments by arts authorities. Recent generations of art historians have looked to the emergence of Native tourist arts, or market arts, for evidence of such analogous engagements of Native agency and intentionality in the historical record of object exchanges (Graburn 1976; Wyckoff 1990; Drooker 1998; Phillips 1999). Market art transactions, the creation and sale of objects to tourists and other outsiders, characterize the colonial spaces of cross-cultural encounter. Frameworks of modernity also structure the transformation of the object into a commodity and the connections to networks of far-ranging relations that commodities inextricably entangle. Art historical assessments of art made for the market tends to focus on the entrepreneurial contexts of market art production. As public policy, for example, mid-twentieth century the United States embraced the promise of Native art as a progressive path to economic development with the Indian New Deal and the Arts and Crafts Board (Schrader 1983). The historical record is rich in episodes of artistic revival and cultural renewal stemming from market arts production and its support of economic and cultural sustainability. Interpreting those early Native producers of market arts as simply cottage business, however, may unnecessarily narrow the narrative.

There are other, prior, more Native-centric structures for Native deployments of objects as part of cross-cultural transactions, beyond tourist or market art commodification to undergird cultural renewal of art traditions. Ancient North American protocols called for formal exchanges of meaningful objects. These kinds of exchanges also structured the earliest episodes of cross-Atlantic diplomacy and trade. “Fur trade” models of such transactions, however, also tend to emphasize capitalist commodity exchange. Native motivations for certain kinds of material exchanges, on the other hand, often emphasized diplomatic objectives, principally the creation and maintenance of dependable, kinship-like relationships and alliances. Native-made objects created meaning within the performative settings of their exchanges and then, of course, thereafter in the paths of their transmission and transitions within the other worlds to which they were committed. Intentionality ties to the work such objects were tasked to perform. Diplomatic exchange of wampum provides one such example. Consider as well the many references in the historical record of the formal exchanges of clothing. In the diplomatic protocols of North America, “dressing” another established mutual obligations and kinship relations (Penney 2007, pp. 85–86). Like kinds of “work” intended for market arts remain under-explored by art historians, in terms of any intentionality of their makers and vendors, but there are hints. Ruth Phillips, for example, examined the diplomatic purposes of quilled boxes, a kind of market art, presented by Mississuaga Ojibwa of Rice Lake, Ontario, to Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, on the occasion of his royal visit in 1860 (Phillips 2004). The tasks put to objects when placed in the hands of others deploy agency and intentionality. Within the asymmetrical relations of authority and power that colonialism constructs, can we perceive strategic efforts of makers/purveyors/donors of objects to engage, influence, obligate, or mitigate such authorities?

2. Siyosapa, Artist/Holy Man

Such questions come to mind when considering the works of Siyosapa (“Black Prairie Chicken”), born Hunkpapa Lakota, probably in the 1840s, but living the latter part of his life listed on the rolls of the Yanktonai (Nakota) of the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana, until 1902.1 His name appears on notes from collectors and documentation associated with objects obtained from him, sometimes inscribed directly on the object. Two short literary sources offer some detail of his biography and persona. He is a protagonist in an anecdote contained within the memoirs of an army wife, Mary Rippey Heistand, who was posted to Camp Poplar River, Fort Peck, with her husband Lt. Henry O.S. Heistand from 1880 to 1884 (Heistand 1908a). Much later, Stewart Culin, then Curator of Ethnology at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, described a visit to Siyosapa’s home at Fort Peck in his memoirs of a summer-collecting expedition in 1900 (Culin 1901).

Siyosapa was a charismatic Wicasa wakan, (holy man or shaman), more specifically a stone dreamer (Posthumus 2015, pp. 234, 250–51; Densmore 1918, pp. 204–47), who lived through violent conflicts of the northern Plains in the 1860s and 1870s and the starvation winters of northern Plains reservation life in the 1880s and 1890s. With the Sun Dance banned among the Lakota in 1883 and the creation of a Court of Indian Offenses at Fort Peck in 1891, the spiritual gifts and sacred knowledge he possessed would seem to have become obsolete, if not criminal. In this environment, Siyosapa became a creator and purveyor of objects, some of which now circulate at the pinnacle of today’s art world. His story may resemble a kind of personal reinvention, forced by historical circumstance, from medicine man to artist, but it may not be that simple. He sold ceremonial equipment, such as buffalo horn cups, rawhide rattles, and medicine objects. Most of these were evidently his, but some he acquired from others. His most spectacular creations, to modern eyes, are the several painted drums either documented or attributed to him. He also created elaborate, multi-part paintings on muslin cloth showing images of equestrian battles, scenes of hunting buffalo from horseback, and the Sun Dance.

Muslin paintings like Siyosapa’s are often interpreted as a kind of market art or auto-ethnography, to borrow Mary Louise Pratt’s (1992, p. 7) term, produced as records and expressions of historical memory. Culin may have been referring to these and painted hand-drums when he noted that Siyosapa “carried on a lively trade in curios which he made for visitors at the post” (Culin 1901, pp. 171–72). It is tempting to see Siyosapa’s efforts here as primarily entrepreneurial and motivated by concerns for a livelihood and support. Life on the ill-provisioned and criminally administered Fort Peck reservation was, in fact, tenuous and certainly needed for sustenance motivated many to sell precious possessions—or desirable manufactures. However, considering what we can glean about Siyosapa’s world view, his efforts extended beyond simply making items for sale. From collections records we know his creations went to the government agent and clerk, ranking military officers, even the boarding school charged with assimilating Fort Peck children into American society, all-powerful and potentially dangerous agents of authority and control over him and the Fort Peck Yanktonai. The evidence suggests Siyosapa sought out these agents of authority as recipients for significant objects.

In the early 1880s Heistand described Siyosapa as, “a tall, slim fellow of erect and dignified carriage”, while in 1900, close to the end of his life, Culin found him, “a spare old man, shabby and poor noticeable only for his eyes which were like those of a hunted animal.” Heistand was impressed with his “superior intelligence,” and Culin described him as “the most intelligent, industrious, and capable Indian I met on the reservation.” They also agreed about his notoriety within the Fort Peck community. “He enjoyed among his people a great reputation for skill in all the magic and black art both for healing and other purposes,” wrote Heistand, and added, “Among white people his reputation was equally great as a humbug.” Culin wrote much later, “Doctor Black Chicken had a record as dark as his name and many were the crimes imputed to him…. He had acted as an intermediary between the whites and the Indians in the old days, now on one side, now on the other, and through natural cunning and shrewdness had preserved his life and freedom” (Heistand 1908b, p. 206; Culin 1901, pp. 170–72).

Culin and Heistand reference Siyosapa’s doctoring practices. Culin observed and collected three sacred stones belonging to him.

Sacred stones (tuŋkan) revealed themselves through dreams. Dreamers found them, often spherical or egg-shaped, in high, exposed places, like the top of a butte. Some thought that Thunder Beings or lightning bolts had left them there. Their owners kept them in a small pouch wrapped in eagle down to inhibit their movement. When activated to find lost horses, predict future events, or to cure the sick, they flew through the air to distant places and returned to speak to their owners in a secret language. The Lakota regarded those who healed with sacred stones as the most powerful category of holy men. Their practice required support by powerful spirit beings (Posthumus 2015, p. 327; Densmore 1918, pp. 205–6).The large one he called “Beats the Drum.” When horses are stolen, the doctor made a tipi in his house under which he placed his drum with this stone. After a time, the rock would beat the drum and reveal the thief and the location of the horses. When a person was very sick and his death anticipated, he painted the two smaller stones. These he called the “Large and Small Doctor”.(Culin 1901, p. 171)

Heistand described an incident of his ability to inflict illness and death upon others, or ĥumúŋğA, to bewitch, poison, or hex (Posthumus 2015, p. 284). Heistand had befriended a Yanktonai woman at Camp Poplar River whom she called “Dolly,”

At the conclusion of the story, Heistand confronts Siyosapa to demonstrate to Dolly the fiction of Siyosapa’s power over her life. It is difficult to assess in Heistand’s writing the differences between reporting and story-telling, but even if the melodramatic and more satisfying ending is simply Heistand’s wish-fulfillment and a literary emplotment, she confirms this more sinister, but not unfamiliar aspect of Lakota “sorcery” or “witchcraft.”It appeared that sometime previous Dolly had provoked Chicken [Siyosapa]; whereupon he had approached and struck her menacingly with a bird’s claw fastened to the end of a stick which he carried as a sorcerer’s wand. Then he told her that the claw had entered her breast and would kill her in forty days.(Heistand 1908b, p. 207)

Heistand offered a few words about Siyosapa’s healing practice,

In this brief statement, Heistand alludes to Siyosapa’s training, “inherited from generations of medicine men.” Siyosapa’s powers required long apprenticeship with elder Wicasa wakan. Certainly, his preparation would require participation in the Sun Dance, the most sacred of Lakota ceremonies, most likely at the highest, most grueling fourth grade when the dancer is suspended from the Sun Dance pole (Walker 1980, pp. 181–82). This conjecture is supported by Siyosapa’s depiction of this ritual act in his muslin paintings.He treated his patients by sorcery entirely—beating a tom-tom and pronouncing mysterious sounds over the affected parts; using the incantations inherited from generations of medicine men, to which he added others of his own invention.(Heistand 1908b, p. 206)

By “tom-tom” Heistand refers to a hand-drum and there are several hand-drums documented or attributed to Siyosapa scattered in museum and private collections. The Oglala Wiscasa wakan, George Sword, said, “A shaman should have a drum and two rattles, these should be made by secret ceremony… He should always sound his drum and rattles when he is performing a ceremony…” (Walker 1980, p. 94).

The several drums tied to Siyosapa represent a singular and influential corpus. Two, in particular, became exemplars of Plains Indian visionary painting during early, art-as-appropriation assessments of American Indian art for late twentieth century museums and their exhibitions. From the scant documentary record, it seems that Siyosapa made painted drums, reproducing their designs, and sold or otherwise transferred them, throughout his adult life, from as early as 1872 to the late 1890s. His repetition of themes and reproduction of designs raise questions about their ritual use and reproduction—made-for-ritual/made-for-sale—or whether such distinctions need to apply in his instance.

3. The “Sitting Bull” Drum

The earliest notice of a drum linked to Siyosapa, if only tenuously, dates to the 1870s, long before he appears in any other documentary record. In 1962, the Museum of the American Indian of New York City acquired a square drum (Figure 1) accompanied by a letter from the former owner, Mrs. Edith Story Gray, a descendant of a long lineage of influential Mohegan women (Morgan 2014).

Figure 1.

Hand Drum, Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai), Collected during the mid-1870s, wood, rawhide, buffalo horn, paint, hide thong, 59 cm × 49 cm × 7 cm. Used by permission of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (232202). Photo by NMAI Photo Services.

In her letter, Mrs. Gray wrote that she had inherited the drum along with a collection of beaded items from her uncle. “This Indian regalia was the personal property of Chief Sitting Bull, a warrior of the Sioux nation of the Black Hills in North Dakota,” she claimed (Gray 1962).

The drum hide is stretched on both sides of a square frame. The image of a yellow buffalo head with piercing red eyes outlined with dense black appears on one side. A faded pair of circles outlined with dotted frames hover above to either side of the buffalo head, one black, one red. A pair of buffalo horns tacked to the upper edges, an unusual feature for any Plains Indian drum, suggests the drum itself as the horned head of a buffalo. The minimalist mystery of the buffalo head painting, its bright chromium yellow with vermillion red trade pigments, all heavily outlined with a charred bone black, would appeal to modernist sensibilities of the latter twentieth century.

The Museum of the American Indian had fallen on hard times by 1962. In 1978, in an effort to revitalize support and call attention to its vast collections, Roland Force, the museum’s reformist director, organized an ambitious exhibition in a newly-renovated federal building, the Customs House, at Bowling Green in lower Manhattan. He seized upon the square drum as a metaphorical theme and visual face of the exhibition. “Echoes of the Drum is a symbolic title,” Force explained to Gary Settle of the New York Times. “The echoes are the artifacts we are showing; the drum is the Indian culture.” In his review of the show, Settle described, “Sitting Bull’s medicine drum,” as “…a square thumper rigged out with steer horns” (New York Times, 21 July 1978, p. C18). Another press piece called out, “a selection of drums stand[ing] in the entry [of the exhibition]. Prominent among them is Sitting Bull’s drum which is used as the show’s logo” (Northwest Arkansas Times, 17 September 1978, p. 24). “The centerpiece is Sitting Bull’s drum…” wrote New York Magazine, “with attached buffalo horns, which looks as though Klee had helped stretch it” (New York Magazine, 16 October 1978, p. 163). The powerful, surrealist-like image with its Max Ernst-like-horns, combined with the legendary persona of Sitting Bull, positioned the drum well for its cross-over into the art-by-appropriation cannon of American Indian art history. It struck a chord of mystery and power with implications of spiritual, ritual and visionary experience as an artistic muse. The 1978 exhibition joined other art exhibitions and new art museum galleries of the 1970s and 1980s to establish the discourse and connoisseurship (the terms of appropriation) of modernist Native American art history.

But what of Mrs. Gray’s claim about Sitting Bull? “Captain John Crawford was the Indian agent for the Sioux tribe of Indians at that time,” she wrote, “and it was through him this regalia was presented to my uncle Elisha.” “My Uncle Elisha Slocum,” she explained, “when a young man was sent out by the Adams Express Co out of Norwich, Conn to open a new office in No [sic] Dakota” (Gray 1962). In addition to the square drum, the collection included an assortment of beaded items: leggings, moccasins, a knife case, and a pierced shirt, all from the tribes living in what is now Montana and North Dakota during the 1870s.

The Adams Express Company, incorporated in 1854 under President and CEO George Washington Cass, shipped goods and money along the proliferating North American railways after mid-century. Cass was also one of founders and directors of Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) and was appointed President of that company during construction, in 1872, of the span striking out west from Fargo, Minnesota, originating in Duluth, but stalled at the Missouri River crossing at Bismarck, North Dakota, as a consequence of the economic “Panic of 1873.” Construction did not resume until 1876. “The railroad practically ended nowhere,” wrote an early historian of the NPRR, speaking of Bismarck at the Missouri River terminus. Although, “[r]unning expenses could with difficulty be earned.” (Smalley 1883, pp. 185–98). G. W. Cass, at that time the CEO of both Adams Express and NPRR, evidently called upon experienced Adams Express managers like Slocum—long employed in Norwich, Connecticut and in his early 40s (Slocum 1882, p. 378)—to help direct shipping along the spur, while the company was reorganizing and waiting for better times.

Militant bands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho opposed the Northern Pacific Railroad with an armed confrontation. After crossing the Missouri River, at Bismarck where the river arches to the northwest, the NPRR planned a route through the center of prime buffalo hunting territories in the Yellowstone basin, land then hunted by Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne who refused to remain at agencies to the east. They regularly attacked railroad survey parties and insisted, during hastily arranged councils with government agents and the military, that the territory was closed to railroads, military posts, and traders. The U.S. military established a cantonment at Bismarck, becoming Fort Abraham Lincoln in 1872, to protect railroad survey parties and enforce the railroad’s progress. The army reconnoitered in strength with survey teams in the Yellowstone country and fought several small actions with Lakota war parties. Fort Abraham Lincoln was the base of operations for George Armstrong Custer’s Black Hills expedition of 1874, seeking gold in the Black Hills to the southwest, and an advanced base for war with the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne in 1876–77 when Custer lost his life (Ostler 2004, pp. 51–62; Miller et al. 2008, pp. 68–80; DeMallie 1986, pp. 31–39).

Captain John “Jack” Crawford was not an Indian agent, but rather an officer of the “Black Hills Rangers,” a militia group organized to protect the gold miners who flocked illegally to the Black Hills after Custer’s 1874 expedition had confirmed the presence of gold there. He is best known today, however, as a showman confederate of Buffalo Bill and the author of The Poet Scout published in 1879 (Nolan 1981). He left the Dakota’s for the stage in 1876, and Slocum had also returned east by 1877, so the timing is right for them to have crossed paths in Bismarck, North Dakota. It is hard to imagine, however, how Crawford would acquire “Sitting Bull’s regalia” as described by Mrs. Gray. At that time, Sitting Bull was actively leading the resistance to both the gold miner’s occupation of the Black Hills and further extension of the railroad west.

Slocum’s collection is an eclectic assortment of different things, in different styles, by different hands. It does not add up to any individual’s “regalia”, but most of the objects are consistent with the mix of northern Plains tribes crowding into the upper Missouri region during this time of mounting conflict. Since mid-century, the buffalo herds had retreated north and west away from the emigration corridor through Nebraska, southern Wyoming, and the central Plains. The Sioux nations followed: Hunkpapa, Oglala, Brule and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies hunted the Yellowstone basin south of the Missouri River and raided against resident Crows. Yankton, Yanktonai, and Dakota bands pushed into the Milk River country north of the Missouri River into territories then occupied by Assiniboine, Blackfeet, and Gros Ventres. President Grant’s administration had hoped to enforce assimilation policies within the confines of the “Great Sioux Reservation” established by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, but the buffalo had not stayed there. In a significant concession to the geopolitics of the moment, the government agreed in 1872 to establish a new agency in Montana for the Sioux at the old Fort Peck trading post site on the upper Missouri River (Miller et al. 2008, p. 75).

Here is where Siyosapa may enter the story. Stewart Culin, during his interview with Siyosapa in 1900, is quite definite in his statement, “He was a Hunkpapa, a renegade from Sitting Bull’s band, and had lived at Fort Peck the last twenty-eight years” (Culin 1901, p. 170). Twenty-eight years before would have been 1872 when the government established the Fort Peck agency on the upper Missouri River. Railway survey crews accompanied by hundreds of troops had swarmed through the prime buffalo country of the Yellowstone that summer, attacked ineffectually by Sitting Bull’s warriors. That fall, a well-treated delegation of Yanktonai and non-militant Hunkpapa leaders returned from meetings in Washington to be reunited with their communities and camped at the newly established agency at Fort Peck, awaiting distributions of payments and food. Militant Hunkpapas under Sitting Bull camped nearby, but the leaders refused to come in. Many of their followers did anyway, tired of war and, perhaps, sensing the futility of their leaders’ resistance (Miller et al. 2008, pp. 76–77; DeMallie 1986, pp. 34–35). Siyosapa, if Culin heard correctly, was one of them. If Siyosapa is the source of the Slocum square drum, he brought it with him or made it shortly thereafter. There is no reason to believe Sitting Bull had anything to do with it, although Siyosapa belonged to Sitting Bull’s band of Hunkpapa. Through some transaction or series of transactions, the square drum may have passed through the hands of Jack Crawford or other intermediaries to Elisha Slocum before 1876. Slocum’s collection is consistent with what one might expect from Fort Peck in the early 1870s: Yanktonai and Hunkpapa beadwork and, significantly, the square drum. The Fort Peck agency lies a few hundred miles upriver by steamboat from Bismarck, the railhead, and a path leading to Mrs. Gray and the Museum of the American Indian.

4. Siyosapa and Fort Peck

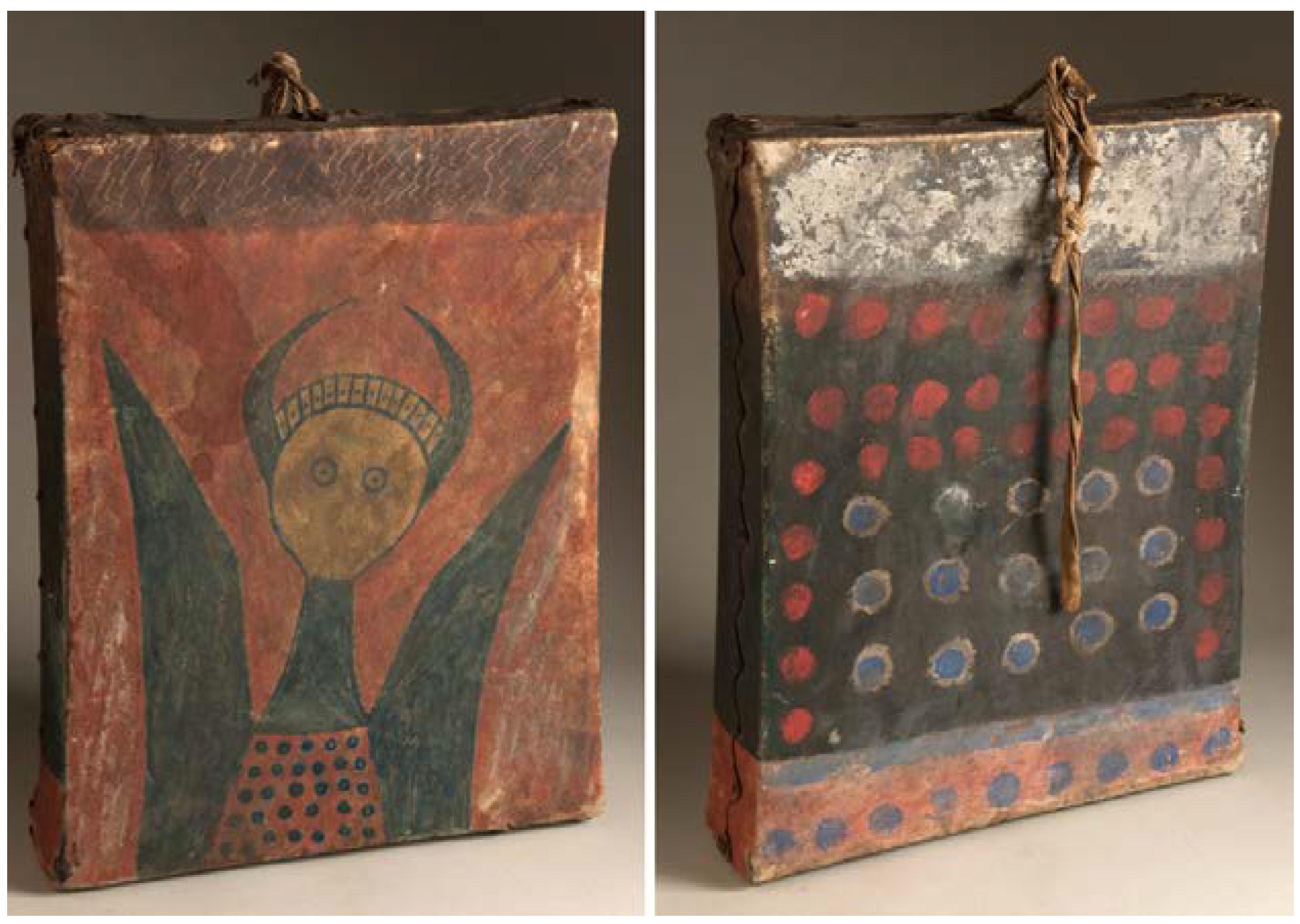

There is another square drum, closely related to the Slocum drum at the Museum of the American Indian, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts: Double-sided with a hide stretched around a slightly smaller square frame and laced along the edges (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hand Drum. Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai), Collected at Fort Peck, Montana in 1885. Wood, rawhide, paint, 40.6 cm × 45.1 cm × 12.1 cm. Used by permission from Detroit Institute of Arts (1990.109). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Pohrt.

Instead of the head of a buffalo, we see a winged and horned figure with the same featureless face and circular red eyes. As in the Slocum drum, two disks heavily outlined with black, their centers alternating green and red, hover in the upper corners tethered to the wings of the figure below. The figure wears a kind of black cloak rising at the shoulders as pointed wings with wavy spines of red and green in reverse symmetry with the colored disks. Instead of thick buffalo horns, the figure wears narrow, curving horns suggesting the split-horn bonnets of northern Plains regalia. The figure resembles the two Thunder Beings on horseback, with their horns and oversized eyes, drawn by the Sans Arc Lakota artist Black Hawk in his book of drawings dating to the 1880s (Berlo 2000, pp. 26–30). Portions of the drum were repainted. Technical analysis shows that the dense white background and heavy black outlines are lead-based commercial house paints and added post collection. Originally, the winged figure had been painted directly on the prepared hide, like the Slocum drum. Beneath the newer painting are still traces of bone black, while the chromium yellow, vermilion red, and green areas remain untouched. Construction, style, materials, iconography, all point to a single hand responsible for both painted drums.

The Detroit drum, like the Slocum drum, helped establish the modernist aesthetic for American Indian art during the 1970s. Curator Norman Feder featured the drum in his 1971 landmark exhibition for the Whitney Museum of American Art, 200 Years of American Indian Art, where he reproduced its image as one of six color plates in the widely disseminated catalogue (Feder 1971, pl. 6). This early and influential project attempted to lay claim to American Indian objects, like the square drum, for nascent art history by emphasizing painting and sculpture “to the exclusion of many types of crafts,” as Feder wrote (1971, p. 2). First here, and then thereafter, the Detroit drum, like its mate, was celebrated as a masterpiece of Plains Indian painting and world art, making significant exhibition appearances in Detroit, Washington, Seattle, Dallas, and more recently, the Museé de Quai Branly in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Penney 1992, no. 215; Torrence 2015, no. 86).

At the time of the Whitney show, the drum was in the care of Richard Pohrt, a collector and former employee of AC Spark Plug of Flint, Michigan, who, in his retirement, showed his collection in an informal private museum he operated in Cross Village, Michigan (Penney 1992, pp. 317–18). The drum and a small collection of beadwork and other materials had come to Pohrt from Burton G. Parker (b. 1903) of Pontiac, Michigan, who had inherited it all from his grandfather, Burton C. Parker (b. 1844). Parker the grandfather had been a former mayor of Monroe, Michigan, a political functionary, and for one year, in 1885, as a reward for service to his party, the federally-appointed agent of the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana (Moore 1915, pp. 1426–28) from where Parker the younger told Pohrt his grandfather gathered the collection.

Conditions at the ill-provisioned agency had become chaotic by 1885. Parker wrote in his annual report that he found the reservation in “a destitute state… [T]he weather was very cold and they were suffering very much for want of clothing” (Parker 1885, p. 132). The Fort Peck Agency, with Yanktonai and Assiniboine under its care and jurisdiction, had moved in 1878 to the mouth of the Poplar River, a location less prone to flooding. Custer was dead, and Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa had fled north to Canada in exile. By 1880, smaller parties of Hunkpapa started to come back across the border to hunt the few remaining buffalo in the Milk River region and visit their relations in the vicinity of Fort Peck. Alarmed, the military established an outpost at the agency, Fort Poplar River, to intercept surrendering Hunkpapa and police the resident tribes. This is when Lt. Henry O. Heistand of the 11th Infantry and his wife, the memoirist Mary Rippey Heistand who wrote about Siyosapa, were posted to Fort Poplar River, from fall of 1880 through May of 1884 (DeMallie 1986, pp. 48–49).

Lieutenant Heistand’s commanding officer in the 11th Infantry, Captain Ogden B. Read, also assembled a substantial collection of objects during his four years there. He received several important gifts of beadwork or other treasures offered by community leaders and those who wanted to be friends. Read also claimed objects from battle sites and from at least one Yanktonai burial. Most of his collection, however, resulted from purchases of objects of ethnographic interest from individuals whose names he recorded in a notebook, including several items from “Black Chicken [Siyosapa], principal medicine man of the Yanktonai tribe.” Two ledger entries hint at Siyosapa’s darker reputation alluded to by Heistand, and Culin: A “scalp and beaded hair ornament…believed to be that of a white woman” purchased from Siyosapa in 1881; and an “ornamented buffalo calf skin….medicine against lightning…It was more valued by the Indians than any other article in this collection. It was purchased from ‘Black Chicken’ … and is believed to have been stolen by him from a medicine woman in the same camp.” Siyosapa sold Read additional items related to medicine practices in 1882, a “buzzard head, etc. medicine,” a “Medicine man’s cap—skin of a white pelican,” a buffalo horn cup, a buffalo scrotum rattle, and a hand drum. There is no reason to believe, on the basis of Read’s notations in his ledger, that Siyosapa had made any these objects or used them in his practice, rather than having procured them from others, like the calfskin (Markoe 1986, pp. 169–74).

Heistand’s memoir confirms Siyosapa’s familiarity and interactions with the post and its personnel (her husband was camp Quartermaster). Her anecdote about Siyosapa’s abuse of Dolly echoes Read’s notes regarding his theft of sacred calfskin from a rival “medicine woman.” He had no reason to sell his own medicine objects, but perhaps incentive to dispose of those of potential rivals. Siyosapa had established himself among the Yanktonai community at Fort Peck and evidently planned to stay there. We sense, in the treacherous conditions of the military occupation of the agency, the Siyosapa later described by Culin: “[A]ct[ing] as an intermediary between the whites and the Indians…now on one side, now on another.”

The hand drum Siyosapa sold Read is round, not square, two-sided, laced at the edges, and painted with the image of a rudimentary face with three circles for a pair of eyes and a mouth (Markoe 1986, pp. 110–11, 123). It does not share many attributes with the two square drums beyond a kind of abstract figural presence familiar more generally to northern Plains graphic imagery. Siyosapa may have made it. He may have had it made in the context of his practice and training of others at Fort Peck. He may have acquired it from another, like the calfskin and perhaps other objects he sold to Read.

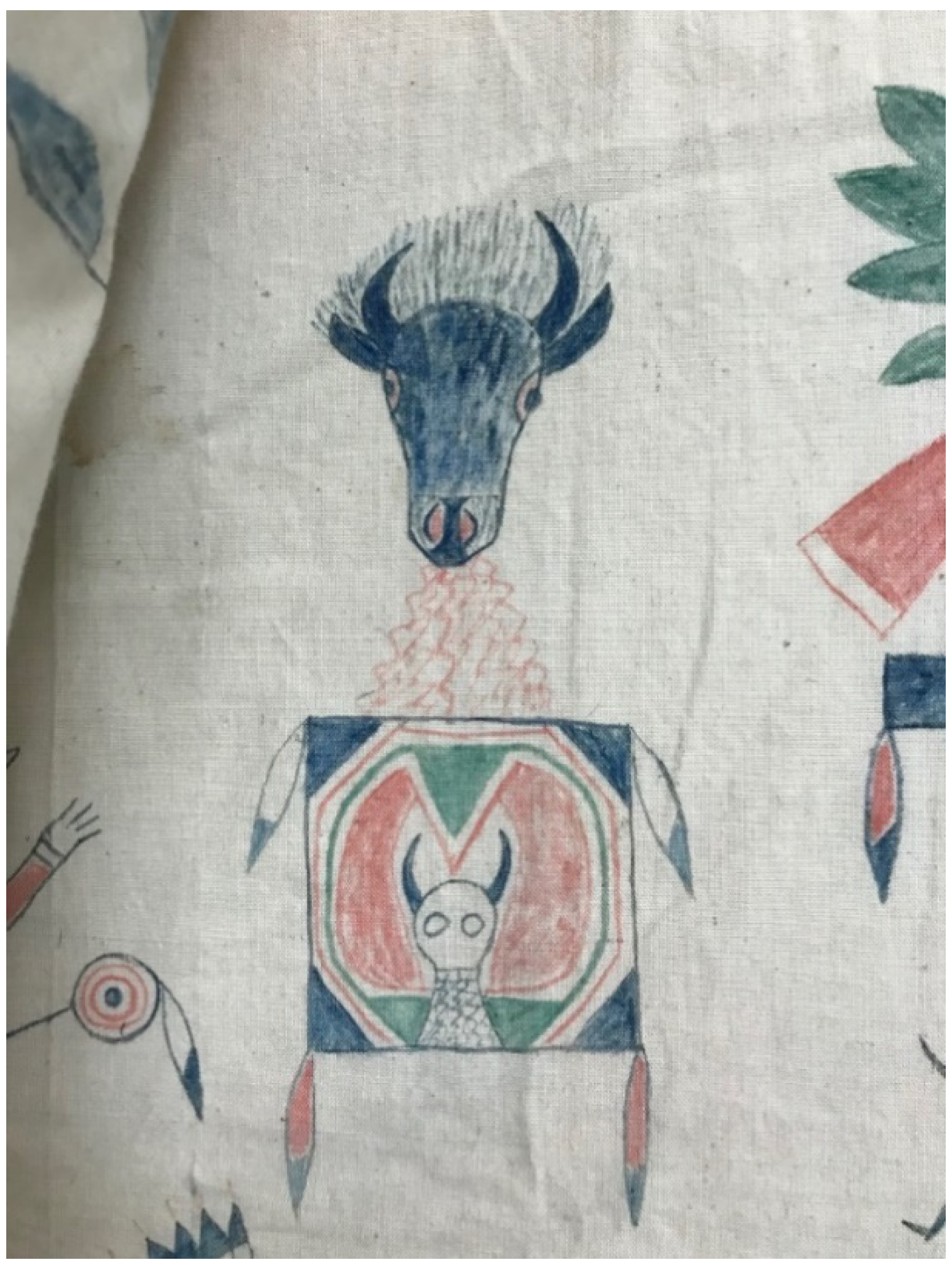

Siyosapa’s activity as a maker of drums is more firmly documented by Frank A. Hunter, employed as the Fort Peck agency clerk a decade later, from 1892 through 1897 (Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Employees of the Indian Service 1892, p. 823; Civil Service Commission 1897, p. 372). He identified Siyosapa in an inscription written on the face of a drum now at the Smithsonian Institution, “Dr. Black Chicken/medicine man/Fort Peck Montana/Presented by F. A. Hunter” (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hand Drum, Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai). Collected at Fort Peck, Montana in the 1890s. Wood, hide, nails, paint, 39.4 cm × 39 cm × 6.4 cm. Used by permission of the National Museum of Natural History (E360130).

Separate circular pieces of hide cover both sides of the drum, but secured with tacks instead of lacing. Like the Slocum square drum, this drum features two buffalo horns nailed to the upper left and right edges. The painting on one side suggests an anthropomorphic buffalo head, but someone later added the lips, a little curved chin, and a Picasso-esque nose drawn in pencil, presumably post collection. Without these added details, the buffalo head image becomes clear, with the tangle of curved lines below representing the buffalo’s breath exhaled through nostrils outlined in black. The Hunter drum also includes two circles with concentric rings, as in both the Slocum and Parker square drums, in this instance connected by an arched band that frames the head.

The painting style of the Hunter drum seems a little more cartoonish than the Slocum and Parker square drums, in contrast to their reductive and heavily-outlined faces, but it dates at least a decade later than both of those. The Smithsonian possesses another closely related drum, from a different source, with the same later buffalo head featuring graphic representation of its breath, and buffalo horns attached to the sides (National Museum of Natural History catalogue no. 331537). At least two more drums with buffalo horns and painted buffalo head images have been located in other collections (Hansen et al. 2017, cover; Montana Historical Society, catalogue no. X1982.44.57). A square drum, also dating to the 1890s and in this later style, repeats the design of the horned-and-winged figure on the Parker drum (Latini 2004, p. 28) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hand Drum (front and back) Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai). Unknown collection date. Wood, rawhide, paint, 44.5 cm × 33.0 cm × 5.7 cm. Used by permission of The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College (1973.1.12).

Altogether, at least seven additional drums, including the Hunter Drum with the “Black Chicken” inscription, would seem to derive from the buffalo or Thunder Being designs of the Slocum and Parker square drums. All of his drums belong to one of these two complementary themes.

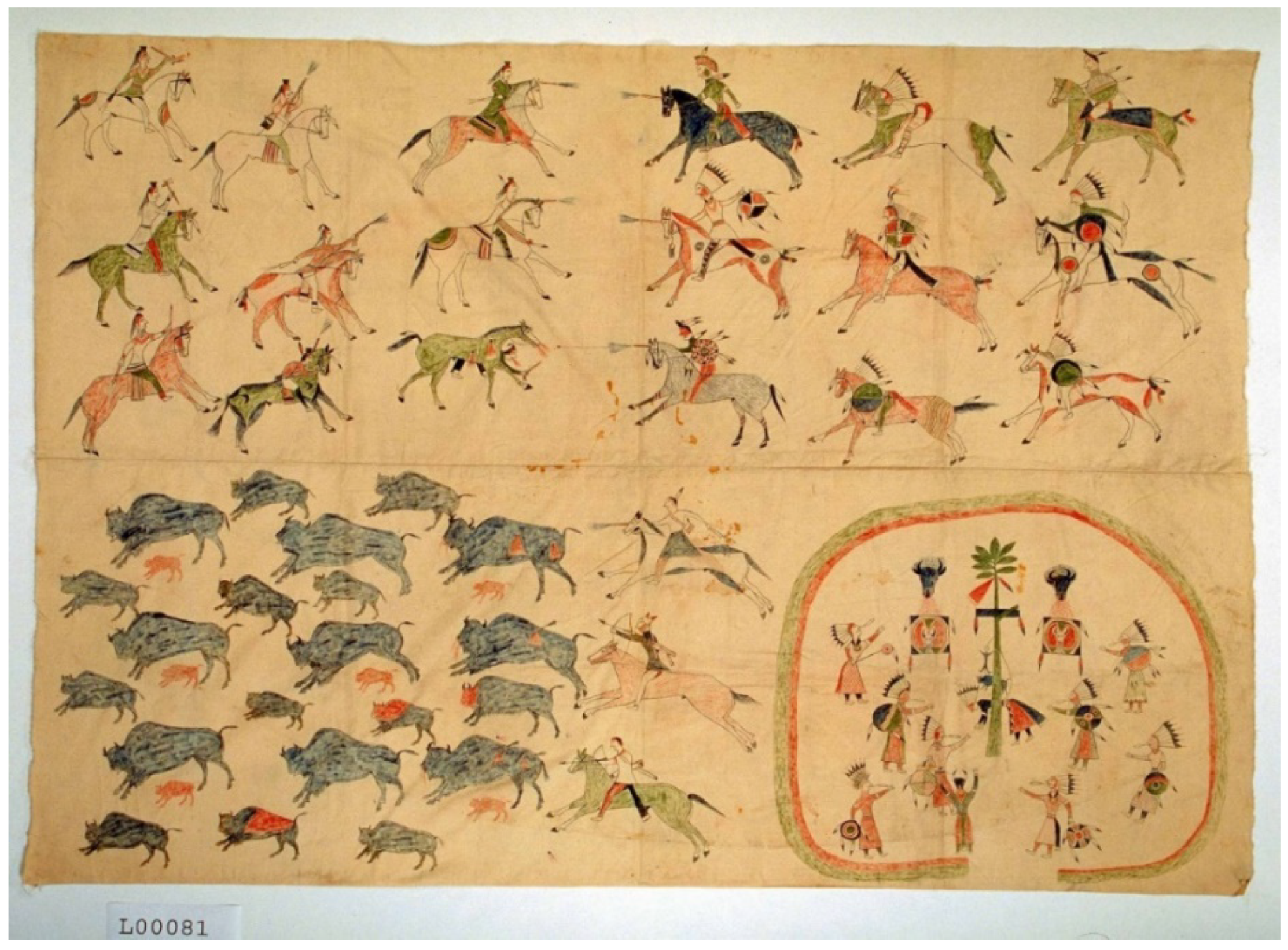

5. The Sun Dance Paintings

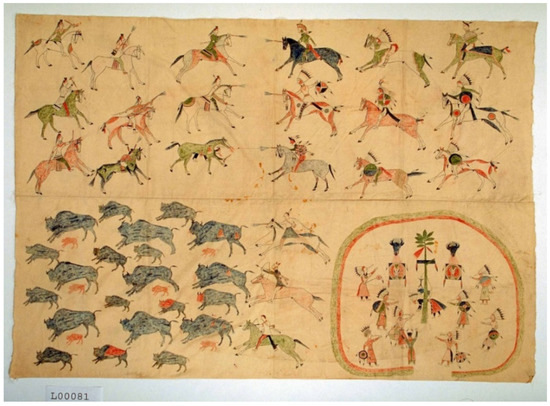

Siyosapa’s muslin paintings shed some light on the paired drums and the larger context of Siyosapa’s creative activity. The earliest, in terms of a verifiable date of collection, links back to the fateful winter of 1880/1881 with the arrival of the military at Fort Peck. The muslin painting in question was donated to the Smithsonian by Captain James Bell who visited Fort Peck during an operation of a scant three weeks over New Year’s when he was ordered to Fort Poplar River in support of Captain Read (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Painting on Muslin. Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai) Collected at Fort Peck, Montana in 1880/1881. Cotton muslin, paint, 259 cm × 178 cm. Used by permission of National Museum of Natural History (EL81-0).

The unusually cold winter had contributed to an episode of crises. The military insisted that any “hostile” Sioux linked to Sitting Bull in Canada should surrender at Fort Buford, downriver. However, the bitter season had prompted smaller or larger Hunkpapa groups in Canada to split off and establish winter camps in the vicinity of Fort Peck with the hope of remaining there. Chief Gall, a prominent leader among those who had followed Sitting Bull to Canada, camped with seventy-three lodges directly across the river from the Fort, and Read considered this a threat. Entreaties to surrender for transport to Fort Buford down river by wagon met with passive resistance building to increasing belligerence on both sides. Read called for reinforcements. Captain Bell arrived with his detachment on December 16 followed by five companies under Major Guilio Ilges for a coordinated attack on Gall’s winter camp on January 2, forcing his surrender. On January 6, Captain Bell accompanied over 300 prisoners-of-war overland to Fort Buford (DeMallie 1986, pp. 52–53).

Years later, in 1895, when Bell offered his collection to the Smithsonian Institution, he identified several objects taken from prisoners at Poplar River when annotating a checklist while he was infirm. He failed to recognize the muslin painting, however, misidentifying it (without seeing it) as a Comanche painting (Gasset 2018). Mary Rippey Heistand recalled, however, that Mrs. “Jimmie” Emily Bell stayed on at Fort Poplar after her husband’s departure that January (Heistand 1908b, p. 306), rather than travel with the prisoners’ guard detail. Plausibly, Emily Bell acquired the painted muslin from Siyosapa and took it with her when she returned to Fort Buford and her husband at a more convenient moment later in the season.

The Bell Muslin is a large and impressive painting on two strips of cotton cloth seamed together by hand along their long edges, measuring combined over eight feet wide and six feet tall. The thirty-six inch-wide bolts of cotton muslin fabric as issued found use as “tipi liners,” a low muslin inner wall that encircles the interior of the conical tent, and rises from the floor. The Bell muslin combines two lengths of cloth with no signs of wear or hanging, today in remarkably fresh condition as if commissioned by or prepared for Mrs. Bell. Across the upper half, above the middle seam, nine mounted Lakota charge from the right facing nine Crow charging from the left, holding weapons and shields, some firing rifles. On the lower left, three equestrian hunters, one with a rifle and two with bows and arrows, pursue a herd of buffalo. To the lower right, Siyosapa depicts a Sun Dance with dancers holding shields and blowing eagle bone whistles arranged around the central Sun Dance pole and encircled by a bower. A single dancer, wearing a feather bonnet like the others, hangs suspended from the central pole (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Painting on Mulin (detail) Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai) Collected at Fort Peck, Montana in 1880/1881. Cotton muslin, paint, 259 cm × 178 cm. Used by permission of National Museum of Natural History (EL81-0).

The Sun Dance is the most powerful of Lakota sacred rites. Sun Dancers historically pledged to dance in fulfillment of vows: To heal ailing family members; for the general health and well-being of the people; to prevail over one’s enemies; to capture many enemy horses or perform other notable acts. “We believed there is a mysterious power greater than all others which is represented by nature, one form of representation being the sun. Thus, we made sacrifices to the sun and our petitions were granted,” said Red Bird, an elderly informant of ethnomusicologist Francis Densmore who danced at age twenty-four. Sun Dancers may offer a sacrifice by cutting their flesh. “A man’s body is his own and when he gives his body or his flesh he is giving the only thing which really belongs to him,” said Chased-by-Bears who had vowed his first Sun Dance in 1867 (Densmore 1918, pp. 86, 96). Siyosapa’s painting shows the fourth and highest degree of self-sacrifice, a dancer suspended from the Sun Dance pole. There is every reason to believe that Siyosapa focused on this episode because he had fulfilled such a pledge on his path to becoming a Wicasa wakan, a holy man or shaman. “If one wishes to become a shaman of the highest order,” a group of Lakota holy men told investigator James Walker in 1896, “he should dance the Sun Dance suspended from the pole so that his feet do not touch the ground” (Walker 1980, pp. 181–82). The painting on the Bell muslin would seem to represent Siyosapa’s fulfillment of this particularly challenging and advanced Sun Dance vow.

Other Lakota artists created images of the Sun Dance on paper and muslin, but Siyosapa’s painting is earlier than many, given the 1880/1881 collection date, and the Bell muslin is clearly not his first given the clarity of concept and skillful drawing. Later Lakota Sun Dance images by others seem more instructive or didactic, often annotated with written inscriptions—in Lakota or English—to explain the ritual. The anthropologist Clark Wissler, for example, commissioned Sun Dance paintings from Short Bull, an Oglala Wicasa wakan, in 1912, under the supervision of investigator (and reservation physician) James R. Walker. He organized his two large muslin paintings by showing activities of the “third day” and “fourth day” and dictated descriptive notes “written by his son in Lakota” (Walker 1980, pp. 183–91). Amos Bad Heart Bull, an Oglala Lakota born in 1869, created a comprehensive collection of over 400 heavily annotated drawings in a ledger book produced between 1891, when he purchased the book, and 1910, the date of its latest drawing. His mere seven Sun Dance drawings in the book show successive stages of the ceremony accompanied by descriptive notes, including a more diagrammatic illustration of the altar, pipes, and other ceremonial items. Too young for the fighting or Sun Dance, Bad Heart Bull is believed to have garnered his knowledge of Lakota ritual and history through interviews with elderly men (Blish 1967, pp. 7–8, 91–97). Walter, or “Junior” Bone Shirt, a Brule Lakota born in 1856 and later enrolled on the Rosebud Reservation, produced probably the most comprehensive collection of Sun Dance illustrations in dozens of drawings in four bound books. Scholar Michael Cowdry argues that Bone Shirt’s many drawings of different Sun Dances show that Bone Shirt had pledged and danced several times himself and had likely achieved the status of Itančan, or Sun Dance leader. Collection dates for Bone Shirt’s drawings cluster between 1889 and 1896 (Cowdrey 2006, pp. 93–117; Margolin 1994). Earlier, in 1883, Hiram Price, the Commissioner for Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior, had issued a memorandum directing the agencies to establish “courts of Indian offenses” and specifying the Sun Dance as one such “Indian offense.” The last Lakota Sun Dance noted officially took place at the Rosebud reservation in 1883 (Hyde 1956, p. 75). Fort Peck organized a Court of Indian Offenses under the direction of Agent C. R. A. Scobey in 1891 with an explicit prohibition of the Sun Dance and other religious practices (Miller et al. 2008, p. 157). There is no evidence of Sun Dances at Fort Peck in the 1880s.

Siyosapa’s Sun Dance image seems less a narrative and more a signification of his particular achievements. In the Bell painting, as mentioned, a single dancer hangs suspended from the Sun Dance pole, the highest form of sacrifice. Eight dancers also in feather bonnets dance with eagle bone whistles in their mouths, looking upward at the sun. Sun Gazing is the most common form of Sun Dance vow. A ninth dancer, with his back to us, wears a horned headdress. In other Siyosapa Sun Dance paintings, this figure wears a more explicitly-rendered buffalo head or headdress. This may be a Buffalo Dancer, an advanced form of Sun Dance performed only by those who have pledged and danced before (Walker 1917, pp. 114–15), perhaps another vow fulfilled by Siyosapa.

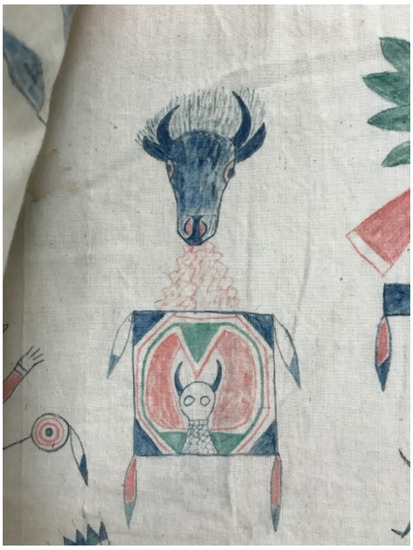

The most unique features of Siyosapa’s Sun Dance painting, however, are the representations of a pair of what appear to be square drums with feather plumes at each of their four corners, flanking the Sun Dance pole above the suspended dancer. Buffalo heads hover above them exhaling fans of tangled lines representing their sacred breath, seeming to consecrate the drums (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Painting on Mulin (detail) Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai) Collected at Fort Peck, Montana in 1880/1881. Cotton muslin, paint, 259 cm × 178 cm. Used by permission of National Museum of Natural History (EL81-0).

A single buffalo skull serves as an altar in the Sun Dance lodge, typically, but the two buffalo heads in Siyosapa’s painting seem to refer to something else. They replicate images of buffalo heads with their sacred breath on some of Siyosapa’s drum paintings, like the Hunter drum. The drums represented in the muslin painting are shown with the busts and heads of horned figures painted on them, also recalling the figures and faces on Siyosapa’s hand drums. None but Siyosapa’s, representations of the Sun Dance include these idiosyncratic representations of square drums. Customarily, singers at a Sun Dance sit around a large horizontal drum, as illustrated by Amos Bad Heart Bull (Blish 1967, p. 95). The hand drums represented in Siyosapa’s Sun Dance paintings, if, in fact, that is what they are, draw an explicit connection to Siyosapa’s painted hand drums with their imagery of horned Thunderer Beings and buffalo, linking these two material expressions of his ritual practice and spiritual achievements, and raising intriguing implications for his painted drums.

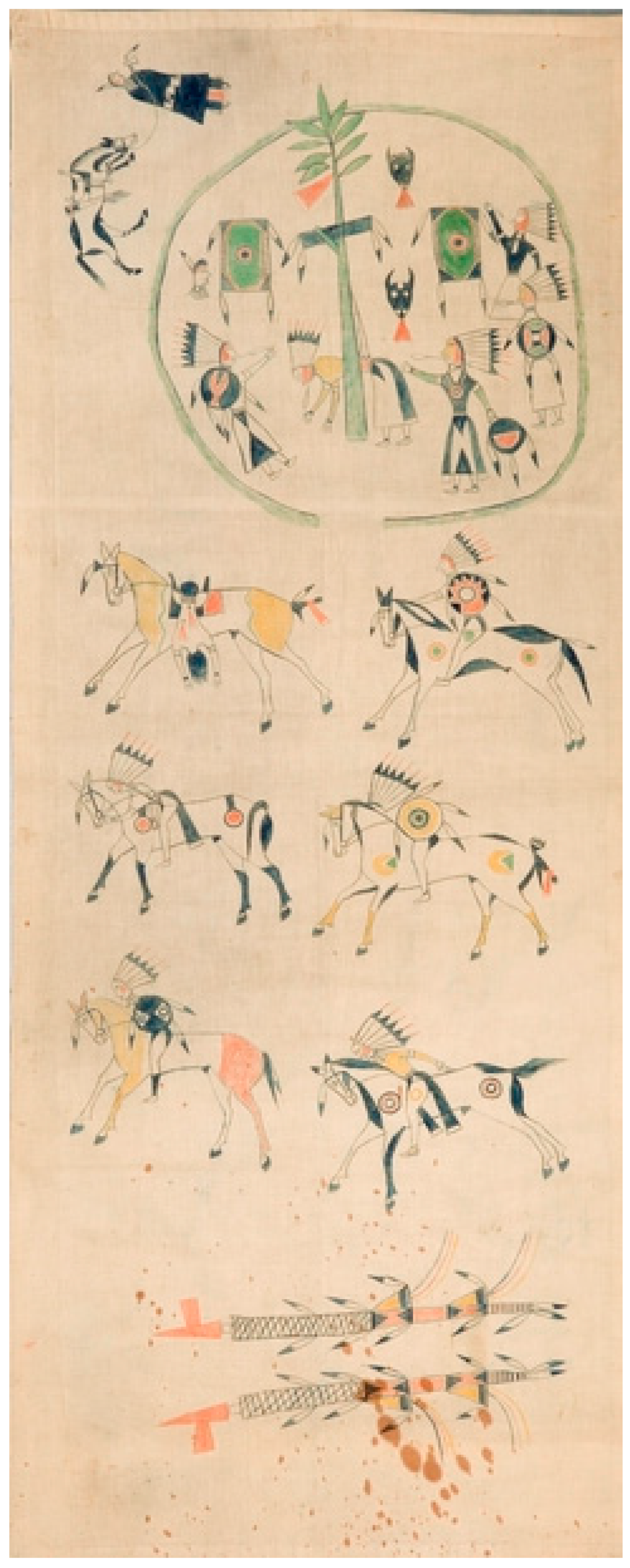

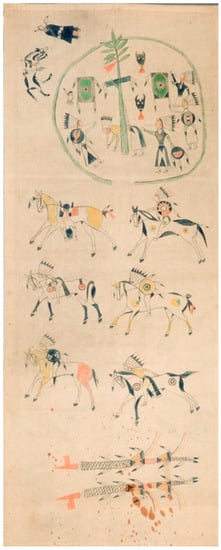

Siyosapa’s distinctive Sun Dance composition is duplicated, with variations of detail, in many additional paintings. One that is firmly documented to him, through a dedication by the donor, was “presented by Black Chicken, a Sioux Chief of the Oglala Tribe to Major General Lloyd Wheaton stationed at Fort Peck Indian Agency, Montana” to the Chicago History Museum (Catalogue no. 1923.88a-b). Captain Wheaton was posted to Fort Poplar River in 1886 and left as Major and Commanding Officer when the post closed in 1893 (Coe 1896, pp. 670–72; Powell 1890, p. 634). Another of Siyosapa’s painting with a Sun Dance scene, and otherwise mirroring the Bell muslin, spent 60 years as part of the Indian furnishings at Mary Merriweather Post’s “camp” in the Adirondacks called Camp Topridge (National Museum of Natural History catalogue no. E418686A-0). Yet another with a vertical format and smaller version of the Sun Dance scene now at NMAI (Figure 8) was purchased by George Heye in 1909, from Emil W. Lenders, a wildlife artist who at that time was assembling large collections of Native material to sell to ethnographic museums in Germany and the American Museum of Natural History, New York, as well (Feest and Corum 2017, pp. 35–42).

Figure 8.

Painting on Muslin. Attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai), unknown collection date. Cotton muslin, paint, ink, 216.4 cm × 85 cm. Used by permission of National Museum of the American Indian (023304). Photo by NMAI Photo Services.

And to cap off this open ended list, a vertical muslin painting showing the Sun Dance, two drums, and another painting on cloth of Siyosapa’s arrived, somehow, at the infamous Carlisle Indian School, the government-sponsored Indian boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania (Latini 2004, pp. 25, 27–28). Siyosapa’s Sun Dance compositions replicate one another in detail. His drawing is sure-handed and consistent. His paintings can be attributed with certainty on such bases, and there are more, undoubtedly, waiting to be identified (Ewers n.d.).

But what of the buffalo hunt and the fight with the Crows on the Bell muslin? These scenes also re-appear with little variation on others of Siyosapa’s paintings. They may seem little more than generic references to key activities of Lakota traditional life, but their combination with the Sun Dance calls for an alternative consideration. Siyosapa’s youth, in the 1850s and 1860s, falls within a long episode of violent belligerence between Crows resident to the Yellowstone Valley, and Lakota who wished to expand into that territory. Unlike the many other Lakota drawings of battles with Crows, Siyosapa does not seem to refer to any particular event or battle honor, as was customary, although one of the Crow warriors suffers from wounds. Some of his other paintings dispense with the Crow warriors altogether, showing only Lakota riders with feather bonnets (Figure 8). The buffalo hunt scene also seems generic, but includes the unusual detail of small buffalo calves in red, unharmed amidst full-grown and adolescent bulls and cows, while each of the pursuing hunters wounds only one buffalo each at the rear of the fleeing herd. The scene would seem to model conservation-conscious hunting, taking only what is needed and encouraging the herd to bear calves and increase. Siyosapa heightens this impression by his use of red pigment for the buffalo calves. The scene is particularly poignant in the historical context of the diminishing buffalo herds of 1880/1881—commercial hunters had already devastated the herds of the upper Missouri River. The only bison meat available to Fort Peck residents in 1881 had been scavenged from carcasses left by commercial hunters (Miller et al. 2008, p. 126). The hunting and battle scenes in Siyosapa’s paintings may not be simply representations of activities, but rather a visualization of his wishes and the object of his Sun Dance vows: Success against his enemies—the Crow; return and proliferation of the buffalo; and, perhaps, the sacred empowerment of his practice as represented by the hand drums consecrated with buffalo breath.

6. Culbertson and Culin: Intermediaries

When reading museum curator Stewart Culin’s account of his meeting with Siyosapa in 1900, we sense something of a set-up. Culin spent a few weeks at Fort Peck that summer, waiting to rendezvous with fellow museum anthropologist George Dorsey who was collecting on the West Coast. Culin stayed at the fort abandoned in 1893 in lodgings maintained by the agency. He teamed up with Joseph Culbertson, a mixed-blood born in 1856 to trader Alexander Culbertson and Natawista, his Blackfeet wife. Joseph Culbertson had served as a government scout and translator at Fort Poplar since he was a young man. He had acted as an intermediary between Chief Gall and Captain Read leading up to their violent confrontation in 1880/1881 (DeMallie 1986, p. 52). In 1900, Culbertson was the Chief of Indian Police at Fort Peck, and a judge for the Court of Indian Offenses under Agent C. R.A. Scobey. He guided Culin around the reservation to find objects to collect. “He commanded fear and respect of all the Indians on the reservation, and was able to secure access for me to tipis, where, had I been alone, I should have met with refusal,” wrote Culin (1901, p. 168).

Horse theft, Culbertson told Culin, and alcohol were his biggest concerns as Chief of Police. During their ramblings, Culbertson stopped a reservation resident with unbranded horses for questioning. When Culbertson brought Culin to Siyosapa’s home, composed of a cabin and a tipi, he was not there. Culbertson took Culin into Siyosapa’s cabin and found there Siyosapa’s medicine for locating stolen horses: A miniature tipi, a drum, a sacred stone, and a horned headdress made of a horse’s scalp and mane. Siyosapa arrived later and, “[a]fter some negotiation, the agent having prohibited the native medicine rites, I purchased the entire outfit, and obtained from the doctor an account of the names and uses” (ibid., p. 171). A crack-down against so-called Indian offenses that summer is evidenced in an order signed and posted by Agent Scobey, recorded by Culin, “April 2, 1900. The following practices are contrary to the regulations of the department and must cease [original emphasis]” Among a long list of infractions Scobey specified, “the pow-wow or sorcery by medicine men” (ibid., p. 173).

Was Siyosapa suspected of colluding with horse thieves, and therefore, coerced into giving up his medicine things? Agent Scobey had outlawed Siyosapa’s practice explicitly, and Culbertson was bound to enforce the regulations. On the other hand, maybe Culin was the one set up. The order had been issued months before. Culbertson and Siyosapa had known each other for decades, and it seems unlike Siyosapa not to have reached some provisional understanding with a figure of authority like Culbertson. Rather than confiscate Siyosapa’s horse medicine and sacred stones, Culbertson brought Culin to buy them.

Culin’s summer journal provides the only known account of Siyosapa’s interactions with a buyer, and introduces the mediation of long-time Fort Peck translator and agency employee, Joseph Culbertson. The 1900 U.S. census for the reservation, prepared by Agent Scobey, identified “Black Chicken” as a “ration Indian” who could not speak English. Culbertson had likely acted as translator and intermediary for Siyosapa before and we can imagine similar occasions, perhaps with Captain Read, Mrs. Bell, Agent Parker, Major Wheaton, Clerk Frank Hunter, and others: The offer of intriguing, mysterious and desirable things, “some negotiation” through Culbertson as translator, and the sale.

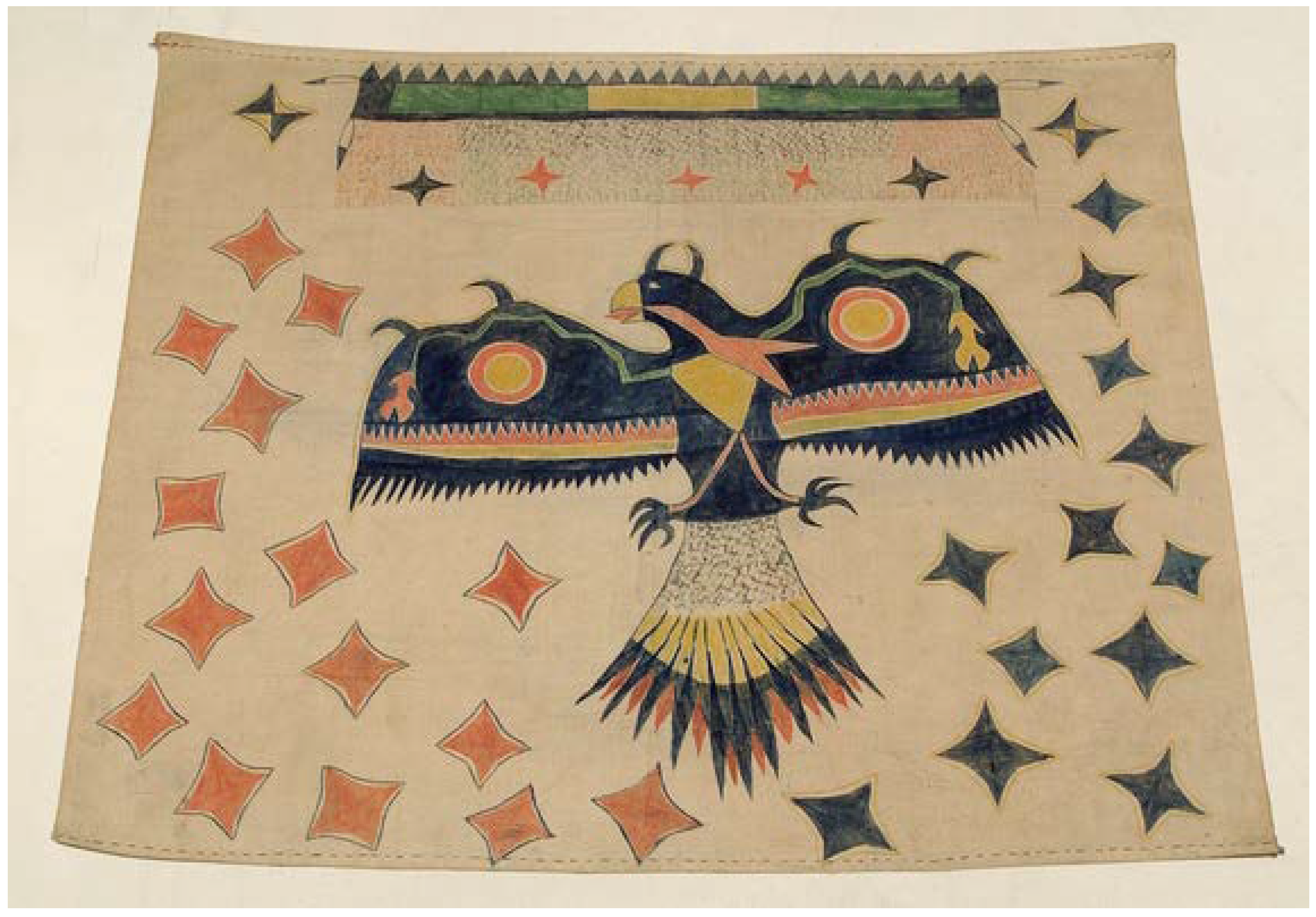

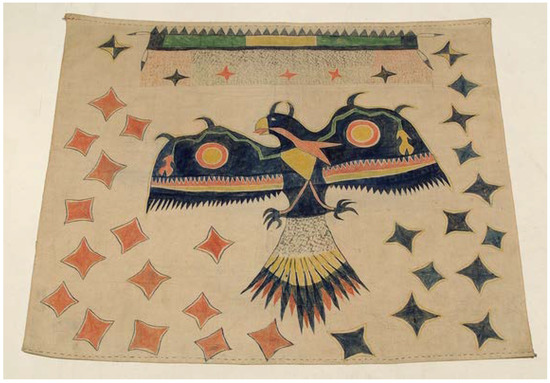

Culbertson’s collaboration with Siyosapa may help explain how five of Siyosapa’s creations made their way to Carlisle Indian School. These five objects represent the largest assemblage of Siyasapa’s work in any one place and include a Sun Dance muslin painting, a square drum that reproduces the Thunder Being image of the Detroit Drum, another half-square drum with buffalo figures related to the Slocum and Hunter drums, a painted shield, and what appears to be a painted cape. The “cape,” if that is what it is, resembles protective garments worn by warriors, but more simply it is a painting of a heraldic Thunderbird, wings spread, on an oblong piece of cotton cloth. It relates closely to a cape or “kilt” sold to George Heye by Emil Lenders in 1909, and attributed much later to Siyosapa by John C. Ewers (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Painting on Muslin, attributed to Siyosapa (Hunkpapa/Yanktonai) Cotton muslin, paint, ink, 90.3 cm × 77 cm. Used by permission of the National Museum of the American Indian (023132). Photo by NMAI Photo Services.

The cotton cloth cover for the shield at Carlisle is painted in a similar style with the figure of a rampant bald eagle confronting Siyosapa’s familiar buffalo head (Latini 2004, Figures 54 and 57). These images, and others that resemble them also attributed to Siyosapa, broaden our understanding of Siyosapa’s visual and material vocabulary. Records from Carlisle confirm their presence at the school, but provide no information about when they arrived or how they got there. Siyosapa’s son Peter, born in 1884, would seem a logical candidate, and he is designated as “at school” in the 1900 national census, but there is no sign of him in any of the records at Carlisle (Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center n.d., Student Records). He likely went to Fort Shaw Indian Industrial Training School, located just west of Great Falls, Montana, which opened in 1892 and was preferred by the Fort Peck agents. The Montanian and Chronicle reported that a Peter Chicken won the sack race during the 1901 Fourth of July celebrations in nearby Chouteau, Montana. In 1890 and 1891, Fort Peck sent two groups of older students to Carlisle (Miller et al. 2008, p. 162). The 1890 group included Joseph Culbertson’s sixteen-year-old daughter Josephine, who had been living among the Canadian Blackfeet with her grandmother Natawista up until that time (Wischmann 2004, p. 36, n. 55). The next year Culbertson’s fourteen-year-old son Joseph joined her at Carlisle. She withdrew in 1893, while Joseph remained at Carlisle until 1896 (Student Records, Carlisle Digital Resource Center). Rather than Peter, the Culbertson family is the most likely connection between Siyosapa and the Carlise Indian School, but why Joseph, Sr., would have sent Siyosapa’s things there, particularly in light of the school’s assimilationist mission, remains a mystery.

Siyosapa’s 1900 interaction with Culin resulted in no bitterness, so it seemed to Culin. He wrote that their working relationship and his respect for Siyosapa grew thereafter, as he commissioned two pairs of sticks for the “hoop and pole” game and a set of stones and markers for a women’s game played on the ice called umpapi in Hunkpapa. “He worked night during the remainder of my stay, manufacturing the implements used in the old games for our collection” (Culin 1901, pp. 171–72). Later, in his magnum opus of foundational ethnography, Games of the North American Indian, Culin called out Siyosapa twice by name, “Black Chicken,” identifying him as a Hunkpapa of Sitting Bull’s band and an authority on Hunkpapa traditional knowledge (Culin 1907, pp. 509, 729). Siyosapa’s sacred stones, his horse medicine and the “big and little doctor,” remained at Culin’s sponsoring institution, the University of Pennsylvania Museum, only for a short while. The museum deaccessioned them in 1908, in favor of a collection of California baskets, and then they sold again to the Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Bolz and Sanner 1999, p. 94; Hartmann 1973, pp. 357–58, cat. Nos. 136–39; Feest and Corum 2017, pp. 39–40).

For his part, Siyosapa appears on the Yanktonai rolls at Fort Peck for the last time in 1902, age reported as sixty-eight, father to two children, Sally, five, and “Buck,” two, with their mother Canku, “Road,” short for “Good Road Woman,” thirty-eight. Peter did not return. In 1903 there is just Canku and Sally.

7. The Edge of Art

Culin confirms with certainty that Siyosapa was still pursuing his medicine practice in 1900, as he had evidently throughout his long life at Fort Peck, his hard-earned sacred powers presumably undiminished. It is safe to say that his practice—curing the sick, finding stolen horses, cursing his enemies—included as well the making, disposing of, and replicating painted drums, Sun Dance paintings, and other works. Any understanding of Siyosapa’s motivations when making these objects, and facilitating their acquisition by figures of authority, has to account for the context of his knowledge, skills, and practice as a Wicasa wakan, or “medicine man” as the authorities called him. His understandings of such transactions, the powers of the objects he created, the purposes to which he put them when they left his possession, remain as mysterious to us as the sources of his power and the sacred and secret knowledge he possessed. The motivations we can imagine, limited by our own epistemologies, remain incomplete. Sales for much-needed compensation and support. The desire to ingratiate and influence those of authority and power. The desire to avoid punitive consequences. These motivations are likely all true in part, but stop short of any understanding of how Siyosapa adapted his knowledge and practice to the quickly changing and potentially dangerous world he faced after the 1870s. His works drew directly upon his sacred knowledge and powers. His offering them to others can be understood as one of the methods by which Siyosapa attempted to manage his relations with outsiders and their growing authority over him.

While it is not possible to entirely comprehend Siyosapa’s intention, one can certainly trace its effect. Collection histories reveal his efforts to deploy his creations strategically: To personnel linked to the expanding Northern Pacific Railroad, to military commanders during particular moments of unrest or conflict, to agency employees, to a government boarding school, and to an ethnographer. We can confirm the care and skill he applied to creating such objects and imagery in reference to his powers, their consistency, their insistence in repetition, all contributing to the “quality” of his creations when some are evaluated much later as art. Ironically, it is the turn of modernism with art-by-appropriation assessments of Indian-made objects that brought some of Siyosapa’s creations to broader awareness, even if only at first as exemplars of a constructed, mystic primitivism stemming from early art historical efforts define American Indian art. The broadness of the impact of his creations, the breadth of their circulation, the power of the many different kinds of significations they have inspired, can these facts be in any way tied to Siyosapa’s intentionality? Hard to say.

First and clearly, Siyosapa’s sustained output and engagement with these pictorial media over time created a coherent and consistent visual vocabulary as expressions of his sacred knowledge, prerogatives, and experience. The integrity and authority of the knowledge that informs his visual expression merits consideration of his work alongside other recognized Lakota pictorial interpreters of Lakota worldview, cosmology and ritual, including Black Hawk, Walter Bone Shirt and several other Lakota “artists.” His esoteric visualizations of sacred buffalo and Thunder Beings within the metaphysics of the Sun Dance present a consistent theme too vast to pursue further here, but that invites further inquiry.

Secondly, Siyosapa built upon a broad Lakota pictorial tradition when he committed his knowledge and experience to material form. He deployed his works to influence, instruct, or otherwise engage the outside world in a sustained way. While Siyosapa could not have foreseen the modernist turn that brought his creations to the attention of the art world, art museums, and art history, by what degree did he anticipate it, narrowing the conceptual gap between intention and appropriation? Encroaching modernity, in the form of military and government officials and their agenda of world progress, shaped the latter half of his life. He created material and pictorial expressions of his experiences and powers using media and visual forms proven appealing and accessible to those authorities, to entice, instruct, and perhaps in some measure, to tame them. Siyosapa inhabits a conceptual space within narratives of Native American art history between historic and contemporary, confronted and entangled along the borders of expanding, global modernity, exploring the cusp of commodification, poised at the edge of art. After they left him, Siyosapa’s works often lay dormant, separated from their histories and authorship, positioned in that liminal space between intention and appropriation, their visual language ready to reanimate consideration of their themes and mysteries.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Berlo, Janet Catherine. 2000. Spirit Beings and Sun Dances: Black Hawk’s Vision of the Lakota World. New York: Braziller. [Google Scholar]

- Blish, Helen H. 1967. A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolz, Peter, and Hans-Ulrich Sanner. 1999. Native American Art: The Collections of the Ethnological Museum Berlin. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. n.d. Available online: http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Civil Service Commission. 1897. Fourteenth Annual Report of the Civil Service Commission; Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office.

- Coe, J. N. 1896. Twentieth Regiment of Infantry. In The Army of the U.S.: Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Staff. Edited by Theo F. Rodenbough and William L. Haskins. New York: Maynard Merrill & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Employees of the Indian Service. 1892. Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior; Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Cowdrey, Michael. 2006. An Intact and Complete Album of 30 Walter Boneshirt Drawings, Pine Ridge, South Dakota. In Important Native American Art: The Hendershott Collection. Dallas: Heritage Auction Galleries, Sale no. 643. September 29. [Google Scholar]

- Culin, Stewart. 1901. A Summer Trip Among the Western Indians. Bulletin: University of Pennsylvania, Free Museum of Science and Art, Department of Archaeology, University Museum, vol. 3, pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Culin, Stewart. 1907. Games of the North American Indians. Washington: Bureau of American Ethnology, Fourth Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- DeMallie, Raymond J. 1986. The Sioux in Dakota and Montana Territories: Cultural and Historical Background of the Ogden B. Read Collection. In Vestiges of a Proud Nation: The Ogden B. Read Northern Plains Indian Collection. Edited by Glen E. Markoe. Burlington: Robert Hull Flemming Museum, pp. 19–70. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, Frances. 1918. Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 61. [Google Scholar]

- Drooker, Penelope B., ed. 1998. Makers and Markets: The Wright Collection of Twentieth Century Native American Art. Cambridge: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers, John C. 1994. Graphic Interpretation of the Sun Dance. In Creation’s Journey: Native American Identity and Belief. Edited by Tom Hill and Richard W. Hill Sr. Washington: National Museum of the American Indian, pp. 138–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers, John. n.d. Papers of John Canfield Ewers. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Box 9.

- Feder, Norman. 1971. Two Hundred Years of North American Indian Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art and Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Feest, Christian, and C. Ronald Corum. 2017. Frederick Weygold: Artist and Ethnographer of North American Indians. Louiseville: The Speed Art Museum and ZKF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gasset, David. 2018. Hidden Agencies: Recovering the Role of Historical Indigenous Producers from Museum Documentation. Washington: Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, Nelson. 1976. Ethnic and Tourist Arts: Cultural Expressions from the Fourth World. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Edith Story. 1962. Accession Correspondence, Catalogue No. 23/2202. Washington: National Museum of the American Indian. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Emma I., David W. Penney, and Gaylord Torrence. 2017. Plains Indian Art: Made in Community. Tulsa: Helmerich Center for American Research, Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Horst. 1973. Die Plains- und Prarieindianer Nordamerikas. Berlin: Museum fur Volkerkunde. [Google Scholar]

- Heistand, Mary Rippy. 1908a. Scraps from an Army Woman’s Diary: The Way of the Medicine Man. Army and Navy Life 12: 206–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heistand, Mary Rippy. 1908b. Scraps from an Army Woman’s Diary: Lothario of the Prairie. Army and Navy Life 12: 304–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, George E. 1956. A Sioux Chronicle. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Igloliorte, Heather, and Carla Taunton. 2017. Introduction: Continuities between Eras; Indigenous Art Histories. Canadian Art Review 12: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, Stephanie. 2004. Ceremonial Imagery in Plains Indian Artifacts from the Trout Gallery’s Permanent Collection. In Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery from the Carlisle Indian School. Edited by Molly Fraust, Stephanie Latini, Kathleen McWeeney, Kathryn M. Moyer, Laura Turner and Antonia Valdes-Depena. Carlisle: The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Linda G. 1994. A Lakota Sioux Ledger Book. Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 68: 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoe, Glen E., ed. 1986. Vestiges of a Proud Nation: The Ogden B. Read Northern Plains Indian Collection. Burlington: Robert Hull Flemming Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David, Dennis Smith, Joseph R. McGeshick, James Shanely, and Caleb Shields. 2008. The History of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, Montana, 1800–2000. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, Poplar: Fort Peck Community College. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Charles. 1915. History of Michigan. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Mary Virginia. 2014. Address at the 100th Anniversary of the Mohegan Church. In Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, Paul T. 1981. John Wallace Crawford. Woodbridge: Twayne Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ostler, Jeffrey. 2004. The Plains Sioux and U. S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Burton C. 1885. Fort Peck Agency, Poplar Creek, Mont. August 15, 1885. In Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior; Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 132–35. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, David W., ed. 1989. Great Lakes Indian Art: An Introduction. In Great Lakes Indian Art. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, David W. 1992. Art of the American Indian Frontier: The Chandler/Pohrt Collection. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, David W. 2007. Captains Coats. In Three Centuries of Woodlands Indian Art: A Collection of Essays. Edited by Jonathan C. H. King and Christian F. Feest. Altenstadt: European Review of Native American Studies Mongraphs 3. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B. 1999. Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B. 2004. Making Sense out/of the Visual: Aboriginal Presentations and Representations in Nineteenth-Century Canada. Art History 27: 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthumus, David C. 2015. Transmitting Sacred Knowledge: Aspects of Historical and Contemporary Oglala Lakota Belief and Ritual. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, April. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, William H. 1890. Powell’s Records of Living Officers in the United States Army. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, Robert F. 1983. The Indian Arts and Crafts Board: An Aspect of New Deal Policy. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, Charles Elihu. 1882. A Short History of the Slocums, Slocumbs, and Slocombs of America, Geneological and Biographical. Syracuse: Published by the author. [Google Scholar]

- Smalley, Eugene Virgil. 1883. History of the Northern Pacific Railroad. New York: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Svašek, Marušek. 2007. Anthropology, Art and Cultural Production. London and Ann Arbor: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torrence, Gaylord. 2015. The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky. Milan: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, James R. 1917. The Sun Dance and Other Ceremonies of the Oglala Division of the Teton Sioux. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 16: 53–221. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, James R. 1980. Lakota Belief and Ritual. Edited by Raymond B. DeMallie and Elaine A. Jahner. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmann, Lesley. 2004. Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culbertson and Natoyst-Siksina’. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, Lydia L. 1990. Designs and Factions: Politics, Religion, and Ceramics on the Hopi Third Mesa. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | I am indebted to John C. Ewers for his pioneer work on Siyosapa and to Candace Greene for bringing Ewers’ files about his Siyosapa research at the National Archives of Anthropology to my attention. Greene also guided the research of intern David Gasset (2018). See (Ewers 1994) although the individual identified in the illustration is not Siyosapa of Fort Peck. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).