Applications of Photogrammetric Modeling to Roman Wall Painting: A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius

Abstract

:1. Introduction

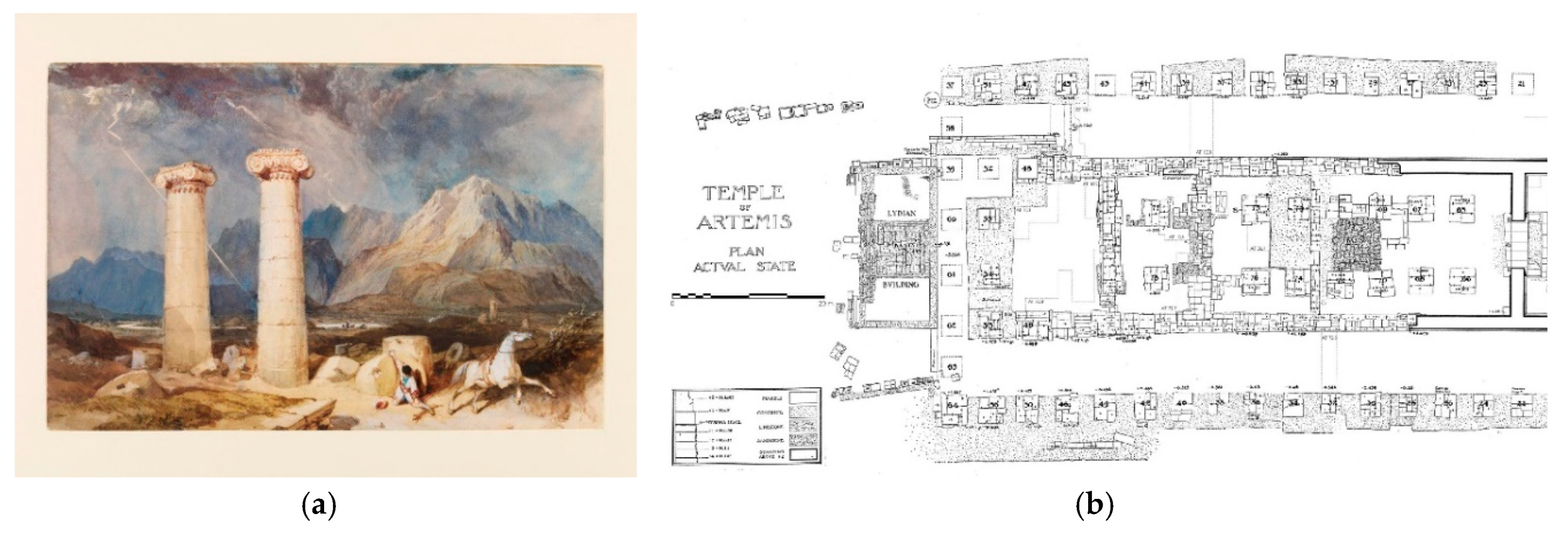

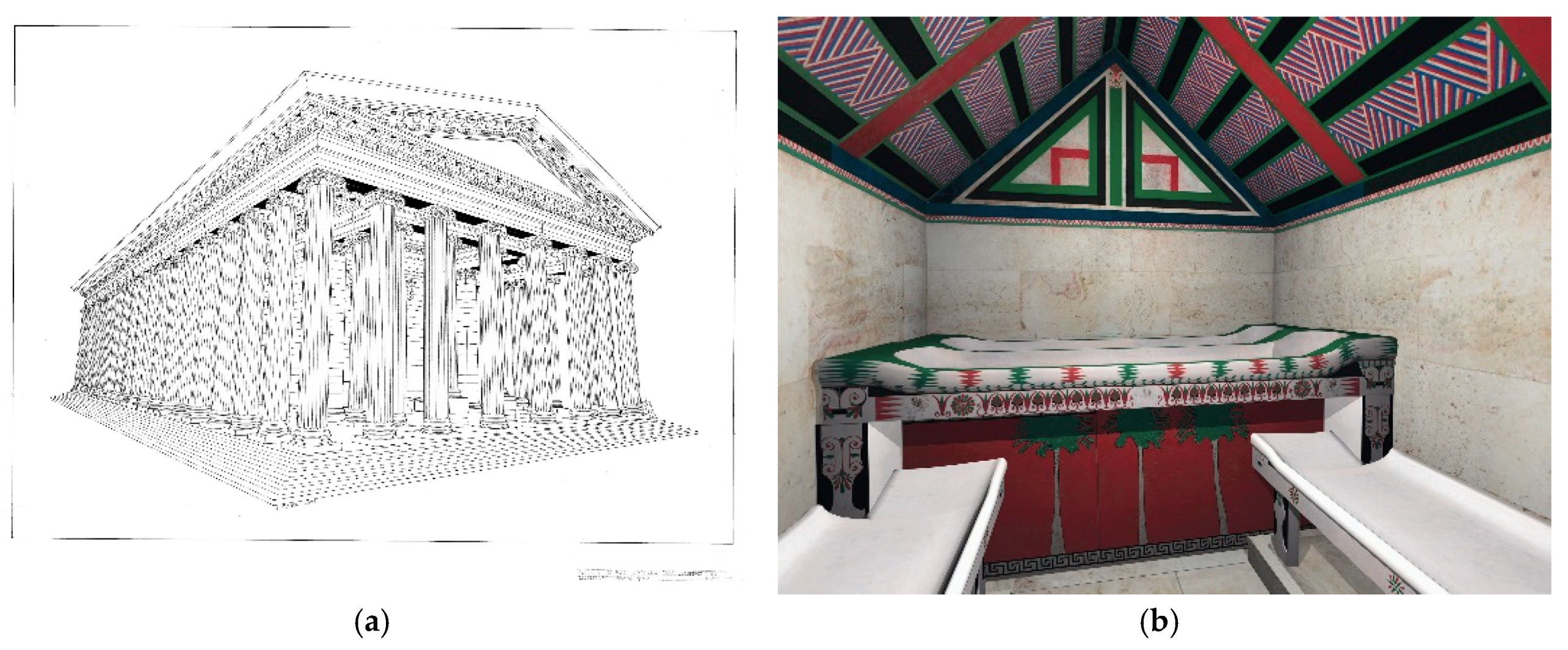

1.1. Brief History of Archaeological Illustration

1.2. Pioneering Projects

1.3. Validity and Utility of Using Models for Visual Analysis

- Facilitating greater understanding of visual interactions between architecture and objects.2

- Promoting the perception of unanticipated emergent properties.

- Highlighting areas where sources conflict (if multiple sources were used in the creation of the 3D model).

- Elucidating the relationship of large- and small-scale features.

- Helping us to formulate hypotheses.

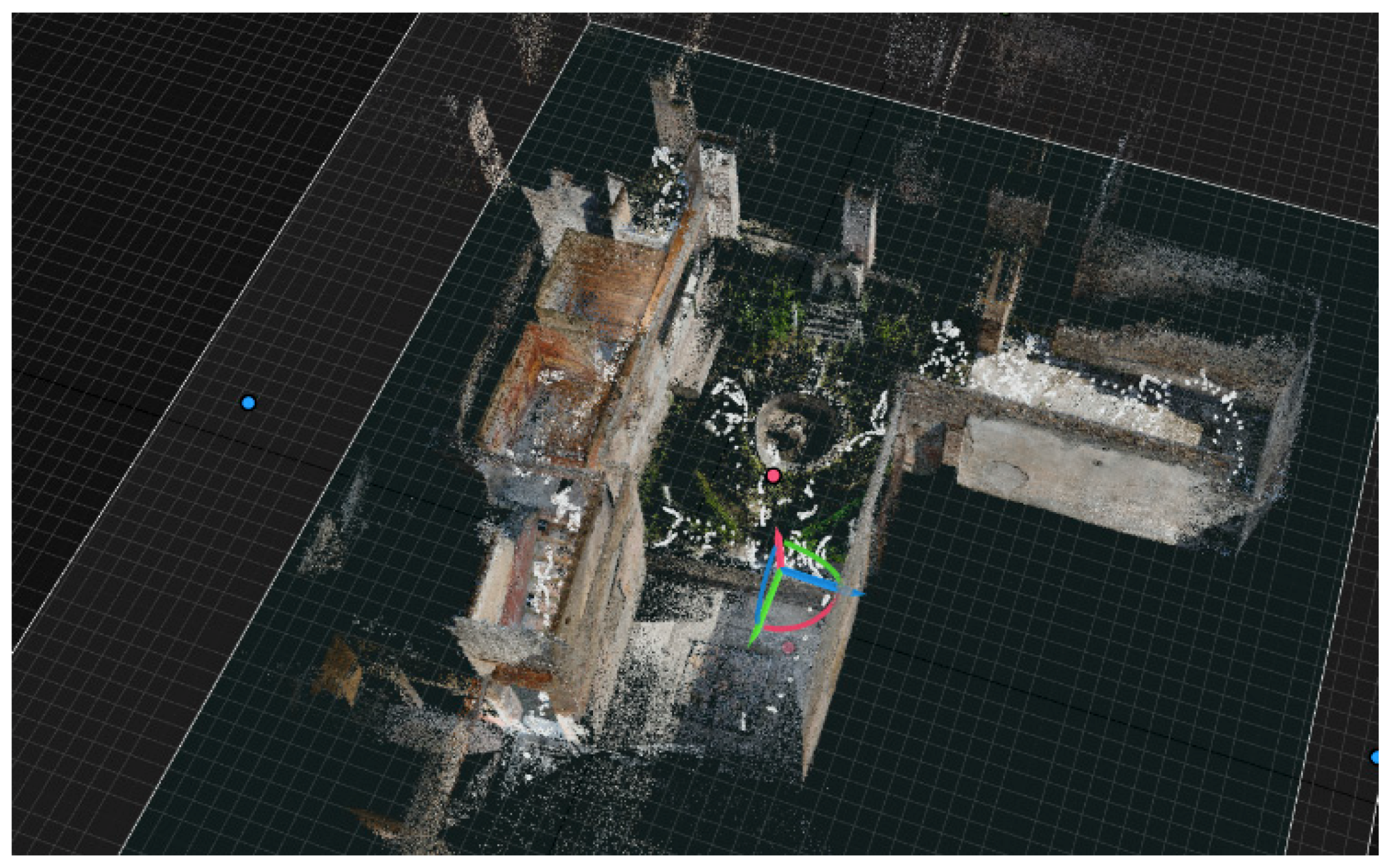

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius

3.2. The Garden Sculpture in Room 18

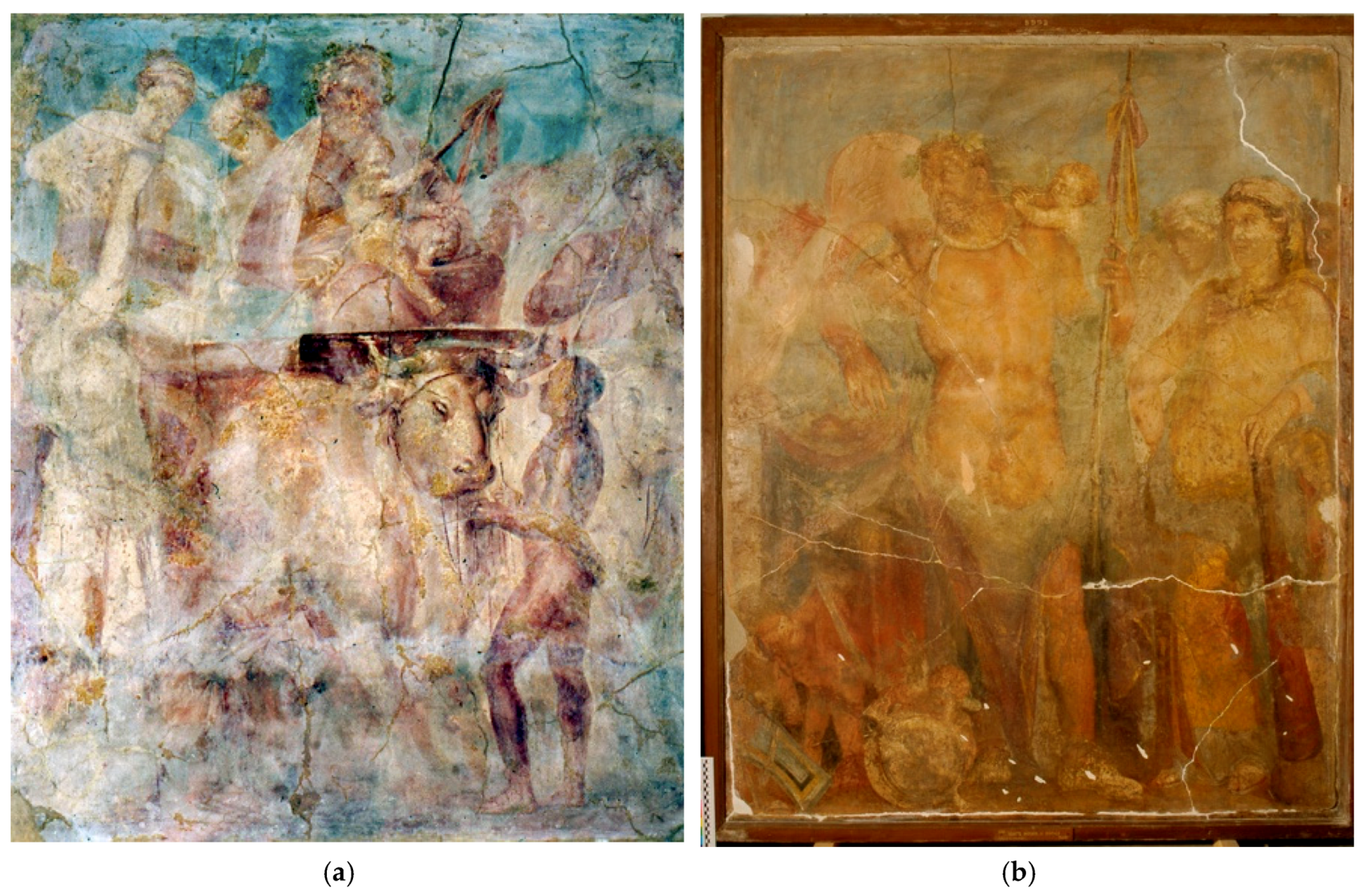

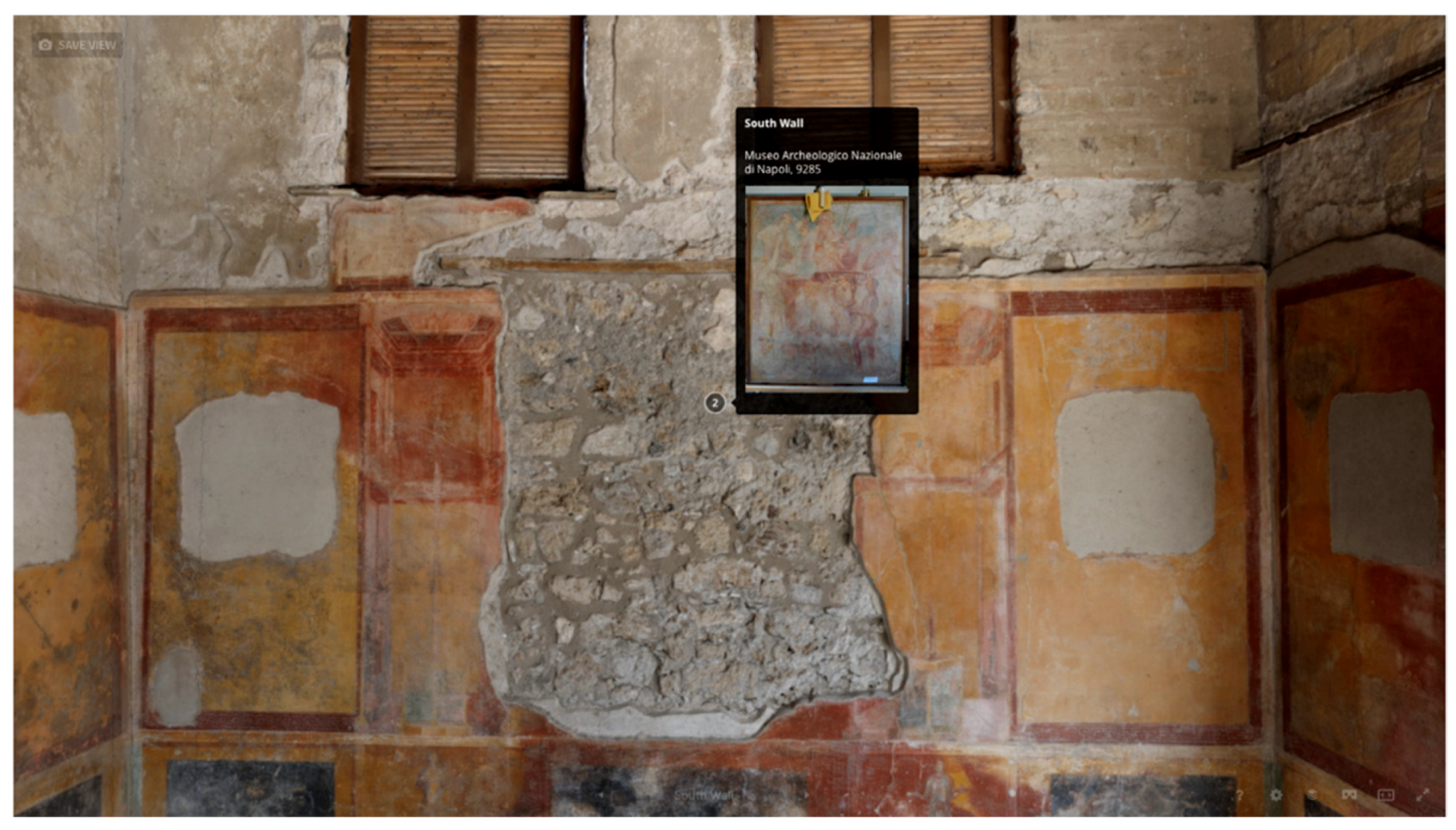

3.3. The Wall Paintings in Room 16

4. Discussion

The Use of 3D Models for Visual Analyses

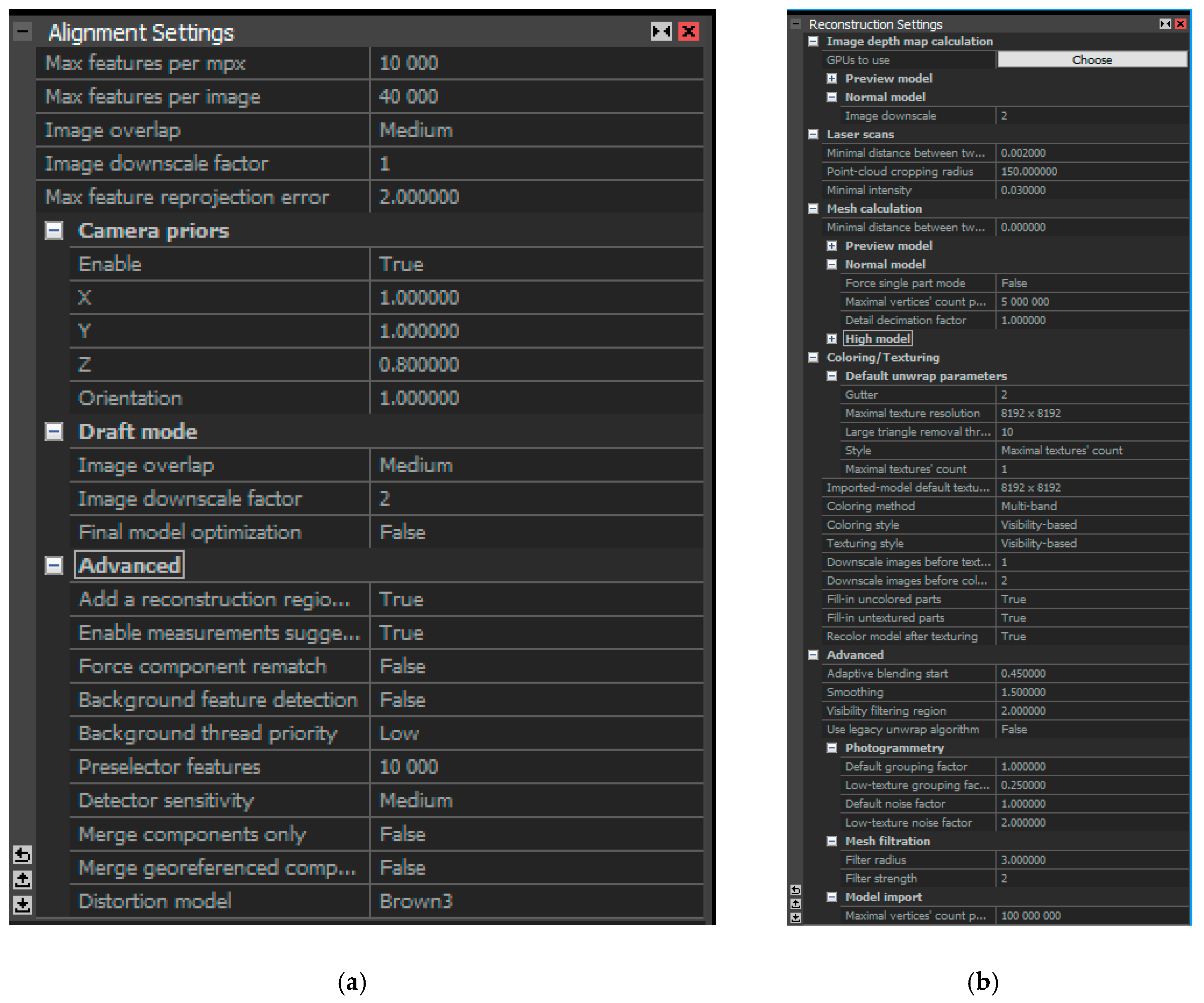

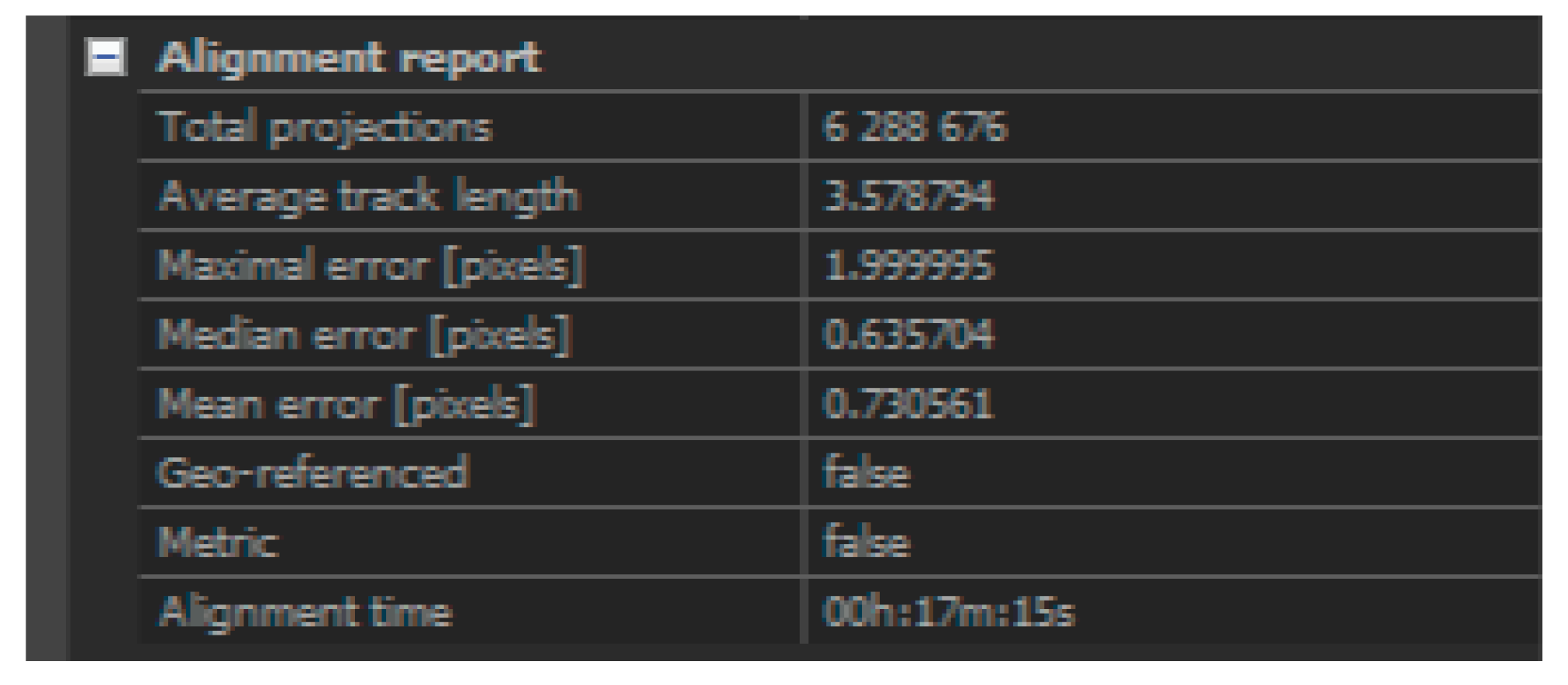

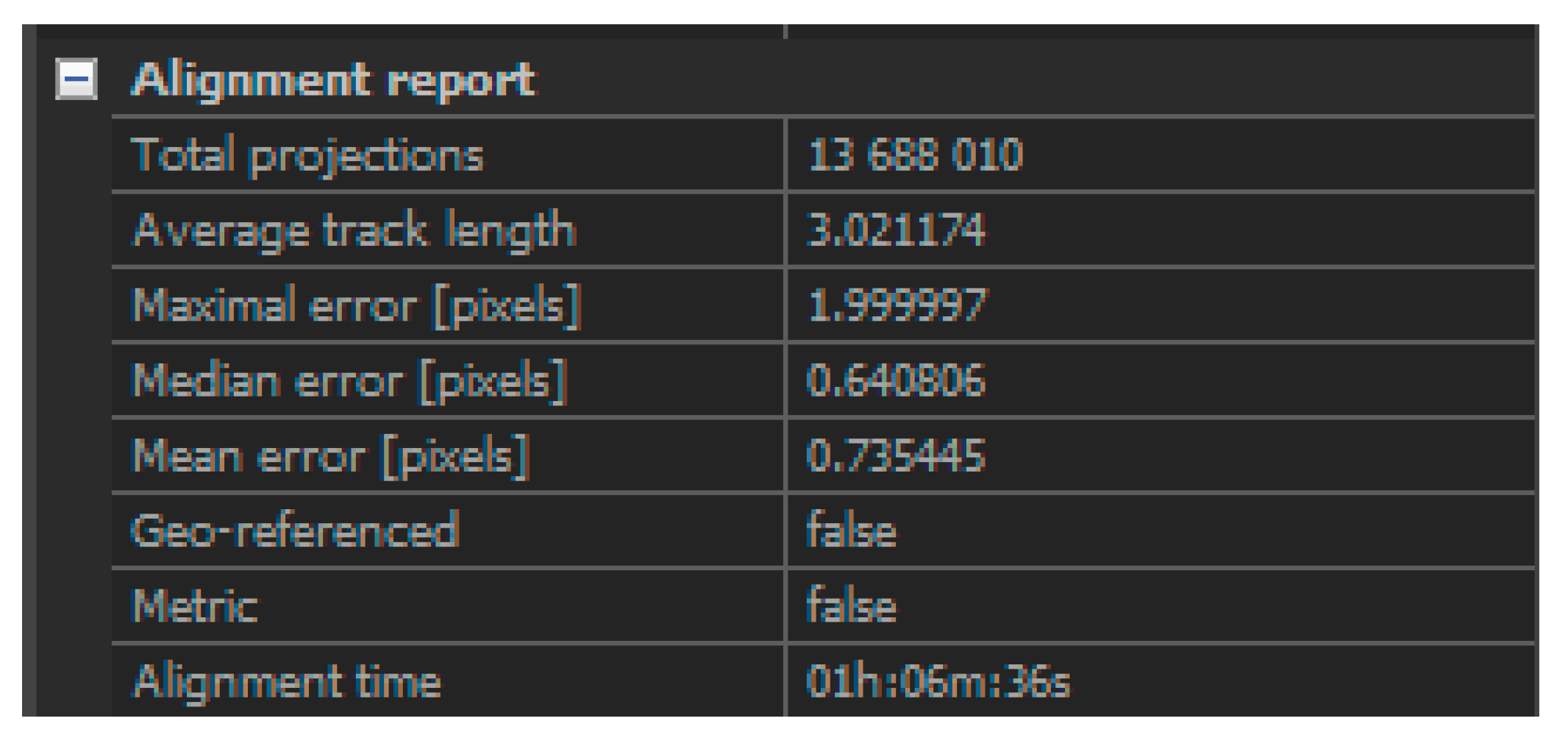

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Digital Publication

5.2. Metadata and Paradata

6. Conclusions

Looking Beyond Illustration: A Federated Database for 3D Models of Roman Wall Paintings

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Paradata for the House of Marcus Lucretius

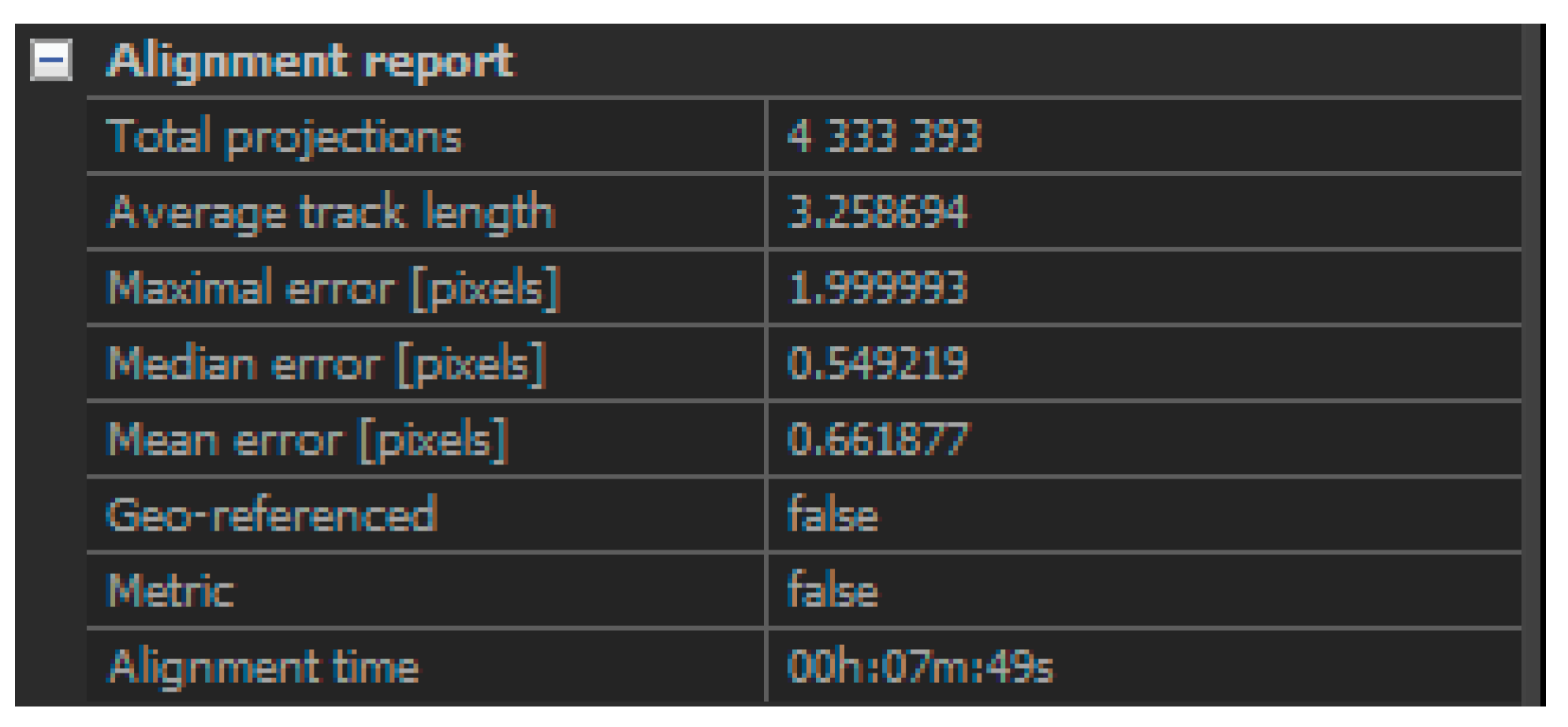

| Orientation | No absolute orientation; photos aligned using internal camera GPS + onsite targets. |

| Software | RealityCapture Version 1.0.3.5681 |

| Mesh Quality | Normal |

| Color Control | Photos Color Balanced Using Adobe Lightroom and X-Rite Digital Colorchecker Passport, Balance System |

- Title/Name: Room 16 in the House of Marcus Lucretius

- Format: Room

- Artist: N/A

- Date: 1st century CE

- Materials: mosaic, fresco.

- Inscription: n/a

- Dimensions: 34.7 m2

- Camera: Nikon D850 with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28mm f/1.4E ED Lens

- Photographers: Kelly E. McClinton & Meghan McCullough.

- Reconstruction Software: RealityCapture, ZBrush

- Modeler: Kelly E. McClinton

- Title/Name: Room 16 in the House of Marcus Lucretius

- Format: Room

- Artist: N/A

- Date: 1st century CE

- Materials: mosaic, fresco.

- Inscription: n/a

- Dimensions: 46.1 m2

- Camera: Nikon D850 with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28mm f/1.4E ED Lens

- Photographer: Kelly E. McClinton

- Reconstruction Software: RealityCapture, ZBrush

- Modeler: Kelly E. McClinton

- Title/Name: Room 19 in the House of Marcus Lucretius

- Format: Room

- Artist: N/A

- Date: 1st century CE

- Materials: mosaic, fresco.

- Inscription: n/a

- Dimensions: 7.0 m2

- Camera: Nikon D850 with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28mm f/1.4E ED Lens

- Photographer: Kelly E. McClinton

- Reconstruction Software: RealityCapture, ZBrush

- Modeler: Kelly E. McClinton

- Title/Name: Room 25 in the House of Marcus Lucretius

- Format: Room

- Artist: N/A

- Date: 1st century CE

- Materials: mosaic, fresco.

- Inscription: n/a

- Dimensions: 26.3 m2

- Camera: Nikon D850 with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28mm f/1.4E ED Lens

- Photographer: Kelly E. McClinton

- Reconstruction Software: RealityCapture, ZBrush

- Modeler: Kelly E. McClinton

- Title/Name: Rooms 16, 18, 19, 20, and 25 in the House of Marcus Lucretius

- Format: Room

- Artist: N/A

- Date: 1st century CE

- Materials: mosaic, fresco.

- Inscription: n/a

- Dimensions: 34.7 m2

- Camera: Nikon D850 with a Nikon AF-S NIKKOR 28mm f/1.4E ED Lens

- Photographer: Kelly E. McClinton

- Reconstruction Software: RealityCapture, ZBrush

- Modeler: Kelly E. McClinton

References

- Allison, Penelope. 1999. The Archaeology of Household Activities. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Autodesk ReCap. n.d. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/solutions/ photogrammetry-software (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Bartman, Elizabeth. 1988. Decor et Duplicatio: Pendants in Roman Sculptural Display. American Journal of Archaeology 92: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartman, Elizabeth. 2010. Sculptural Collecting and Display in the Private Realm. In Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula, 2nd ed. Edited by Elaine K. Gazda. assisted by Anne E. Haeckl, 71–88. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beacham, Richard. 1992. The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beacham, Richard, Hugh Denard, and Francesco Niccolucci. 2006. An Introduction to the London Charter. In The E-Volution of Information Communication Technology in Cultural Heritage: Where Hi-Tech Touches the Past: Risks and Challenges for the 21st Century, Short Papers from the Joint Event CIPA/VAST/EG/EuroMed. Budapest: Archaeolingua. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 1994. With reconstructions by Victoria I. The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii. The Art Bulletin 76: 225–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2010. New Perspectives on the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale. In Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale: The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 67, no. 4 (2010). Edited by Bettina Bergmann, Stefano De Caro, Joan R. Mertens and Rudolf Meyer. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2017. Frescoes in Roman Gardens. In Gardens of the Roman Empire. Edited by Change Jashemski, Wilhelmina F, Kathryn L. Gleason, Kim J. Hartswick and Amina-Aïcha Malek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 278–316. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, David, and Anders Fagerjord. 2017. Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borbein, Adolf Heinrich, and Walter Herwig Schuchhardt. 1962. Antike Plastik. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, Mark. 1991. Pitt Rivers: The Life and Archaeological Work of Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, DCL, FRS, FSA. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campanaro, Danilo Marco, Giacomo Landeschi, Nicoló Dell’Unto, and Anne-Marie Leander Touati. 2016. 3D GIS for cultural heritage restoration: A ‘white box’workflow. Journal of Cultural Heritage 18: 321–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carare Metadata Scheme. n.d. Available online: https://pro.carare.eu (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Castrén, Paavo, Ria Berg, Antero Tammisto, and Eeva-Maria Viitanen. 2008. In the Heart of Pompeii: Archaeological Studies in the Casa di Marco Lucrezio (IX, 3, 5.24). Studi della Soprintendenza archeologica di Pompei 25: 331–40. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John. 1991. The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John. 2006. Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 315. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- John, Clarke, and Nayla Muntasser. 2014. Oplontis: Villa A ("of Poppaea") at Torre Annunziata, Italy. Vol. 1, The ancient setting and modern rediscovery. New York: American Council of Learned Societies. [Google Scholar]

- John R. Clarke, Richard Beacham, Andrew Coulson, Timothy Liddell, and Marcus Abbott. 2016. Digital Imaging at Oplontis. In Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis near Pompeii. Edited by Elaine Gazda and John Clarke. with the assistance of Lynley McAlpine. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum Publication, pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambra, Eve. 1998. Roman Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arms, John. 1999. Performing Culture: Roman Spectacle and the Banquets of the Powerful. In The Art of Ancient Spectacle; Edited by Bettina Bergmann and Christine Kondoleon. Washington: National Gallery of Art, pp. 301–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Unto, Nicolò. 2014. The Use of 3D Models for Intra-Site Investigation in Archaeology. BAR International Series 2598: 151–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Unto, Nicolò, A. M. Leander, Matteo Dellepiane, Marco Callieri, Daniele Ferdani, and Stefan Lindgren. 2013. Reconstruction and Visualization in Archaeology: Case-Study Drawn from the Work of the Swedish Pompeii Project. Digital reconstruction and visualization in archaeology: Case-study drawn from the work of the Swedish Pompeii Project. In 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage). Paestum: IEEE, vol. 1, pp. 621–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Unto, Nicoló, Giacomo Landeschi, Anne-Marie Leander Touati, Matteo Dellepiane, Marco Callieri, and Daniele Ferdani. 2016. Experiencing ancient buildings from a 3D GIS perspective: a case drawn from the Swedish Pompeii Project. Journal of archaeological method and theory 23: 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Eugene. 1974. Pompeian Sculpture in Its Domestic Context: A Study of Five Pompeian Houses and Their Contents. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Eugene. 1982. Pompeian Domestic Sculpture: A Study of Five Pompeian Houses and Their Contents. Roma: G. Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Eugene. 2010. The Pompeian Atrium House in Theory and in Practice. In Roman art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula, 2nd ed. Edited by Elaine Gazda. assisted by Anne E. Haeckl. Haeckl, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jas. 1995. Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. n.d. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/home (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Falkener, Edward. 1860. Report on a House at Pompeii. In The Museum of Classical Antiquities: A Quarterly Journal of Architecture and the Sister Branches of Classic Art. Edited by Edward Falkener. 1814–1896. London: Triibner and Co., pp. 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Maurizio, Stefano Tilia, Angela Bizzarro, and Alessandro Tilia. 2001a. 3D visual information and GIS technologies for documentation of paintings in the M sepulcher in the Vatican necropolis. BAR International Series 931: 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Maurizio, Eva Pietroni, Claudio Rufa, Angela Bizzarro, Alessandro Tilia, and Stefano Tilia. 2001b. DVR-Pompei: A 3D information system for the house of the Vettii in openGL environment. Paper presented at the 2001 Conference on Virtual Reality, Archeology, and Cultural Heritage, Glyfada, Greece, November 28–30; pp. 307–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrick, David. 2014. Time.deltaTime: The vicissitudes of presence in visualizing Roman houses with game engine technology. AI & SOCIETY 29: 461–72. [Google Scholar]

- Frischer, Bernard. 2008. From Digital Illustration to Digital Heuristics. In Beyond Illustration: 2D and 3D Digital Technologies as Tools for Discovery in Archaeology. Edited by Bernard Frischer and Anastasia Dakouri-Hild. BAR International Series 1805: v-xxiv; Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Frischer, Bernard. 2015. Three-dimensional scanning and modeling. In Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture. Edited by Elise A. Friedland and Melanie G. Sobocinski. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Frischer, Bernard, and Philip Stinson. 2007. Scientific verification and model-making methodology: Case studies of the virtual reality models of the House of Augustus (Rome) and Villa of the Mysteries (Pompeii). In “The Importance of Scientific Authentication and a Formal Visual Language in Virtual Models of Archaeological Sites: The Case of the House of Augustus and Villa of the Mysteries,” in Interpreting The Past: Heritage, New Technologies and Local Development. Sponsored by Flemish Heritage Institute, Provincial Archaeological Museum Ename, Province of East Flanders, Ename Center for Public Archaeology and Heritage Presentation. Proceedings of the Conference on Authenticity, Intellectual Integrity and Sustainable Development of the Public Presentation of Archaeological and Historical Sites and Landscapes, Ghent, East-Flanders 11-13 September 2002. Edited by Neil A. Silberman and Dirk Callebaut. Brussels: Flemish Heritage Institute, pp. 49–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gabellone, Francesco. 2009. Ancient contexts and Virtual Reality: From reconstructive study to the construction of knowledge models. Journal of Cultural Heritage 10: e112–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, Elaine. 2010. Introduction. In Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula, 2nd ed. Edited by Elaine Gazda. assisted by Anne E. Haeckl. Haeckl, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, Elaine. 2015. Domestic Displays. In The Oxford handbook of Roman Sculpture. Edited by Elise A. Friedland, Melanie G. Sobocinski and with Elaine Gazda. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 374–89. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, Guy, J.-A. Beraldin, John Taylor, Luc Cournoyer, Marc Rioux, Sabry El-Hakim, Réjean Baribeau, François Blais, Pierre Boulanger, and Jacques Domey. 2002. Active Optical 3D Imaging for Heritage Applications. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 22: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, Gabriele, Alessandro Spinetti, Luca Carosso, and Carlo Atzeni. 2009. Digital three-dimensional modelling of Donatello’s David by frequency-modulated laser radar. Studies in Conservation 54: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, Gabriele, J-A. Beraldin, and Carlo Atzeni. 2004. High-accuracy 3D modeling of cultural heritage: The digitizing of Donatello’s ‘Maddalena’. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 13: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidi, Gabriele, Laura Loredana Micoli, S. Gonizzi, Rodriguez Navarro, and Michele Russo. 2013. 3D digitizing a whole museum: A metadata centered workflow. Paper presented at the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress IEEE, Marseille, France, October 28–November 1; pp. 307–10. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, Gabriele, Michele Russo, and Davide Angheleddu. 2014. 3D survey and virtual reconstruction of archeological sites. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 1: 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, Pier Giovanni. 2018. The discovery of Herculaneum and Pomepii and the dissemination of a knowledge of them. In Ercolano e Pompei: visioni di una scoperta = Herculaneum and Pompeii: visions of a discovery. Edited by Guzzo Pier Giovanni, Maria Rosaria Esposito and Nicoletta Ossanna Cavadini. Geneva: Skira, pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, Pier Giovanni, Maria Rosaria Esposito, and Nicoletta Ossanna Cavadini. 2018. Ercolano e Pompei: visioni di una scoperta = Herculaneum and Pompeii: visions of a discovery. Geneva: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Hartswick, Kim. 2017. Sculpture in Ancient Roman Gardens. In Gardens of the Roman Empire. Edited by Change Jashemski, Wilhelmina F, Kathryn L. Gleason, Kim J. Hartswick and Amina-Aïcha Malek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 341–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Ine. 2013. Aesthetic maintenance of civic space: the" classical" city from the 4th to the 7th c. AD. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Jashemski, Wilhelmina. 1979. The Gardens of Pompeii: Herculaneum and the Villas Destroyed by Vesuvius. New Rochelle: Caratzas Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Katsianis, Markos, Spyros Tsipidis, Kostas Kotsakis, and Alexandra Kousoulakou. 2008. A 3D digital workflow for archaeological intra-site research using GIS. Journal of Archaeological Science 35: 655–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kockel, Valentin. 2016. The rediscovery and visualisation of Pompeii: the work by the Niccolini brothers and its context. In The Houses and Monuments of Pompeii. Edited by Valentin Kockel and Sebastian Schütze. Köln: Taschen, pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, David, Bernard Frischer, and Greg Humphreys. 2009. Research challenges for digital archives of 3D cultural heritage models. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH) 2: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivalainen, Ilkka. 2008. Le sculture del giardino. In Domus pompeiana: una casa a Pompei: mostra nel museo d’arte Amos Anderson, Helsinki, Finlandia, 1 marzo–25 maggio 2008. Edited by Paavo Castrén. Helsinki: Otava, pp. 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Landeschi, Giacomo. 2018. Rethinking GIS, Three-dimensionality and Space Perception in Archaeology. World Archaeology, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeschi, Giacomo, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Karin Lundqvist, Daniele Ferdani, Danilo Marco Campanaro, and Anne-Marie Leander Touati. 2016. 3D-GIS as a platform for visual analysis: Investigating a Pompeian house. Journal of Archaeological Science 65: 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levoy, Mark. 1999. The Digital Michelangelo Project. Paper presented at 3DIM’99 the 2nd International Conference on 3-D Digital Imaging and Modeling, Ottawa, ON, Canada, October 4–8; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lingua, Andrea, Paolo Piumatti, and Fulvio Rinaudo. 2003. Digital photogrammetry: A standard approach to cultural heritage survey. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences ISPRS Archives 34: 210–15. [Google Scholar]

- London Charter. n.d. Available online: http://www.londoncharter.org (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Maschek, Dominik, Michael Schneyder, and Marcel Tschannerl. 2010. Virtual 3D Reconstructions–Benefit or Danger for Modern Archaeology? In International Conference ‘Cultural Heritage and New Technologies 14. Edited by Wolfgang Börner. Vienna: Verlag der Stadt Wien, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, August. 1902. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. Translated by Francis Kelsey. New York: Macmillan & Co. [Google Scholar]

- McClinton, Kelly. 2019. The Garden in the House of Marcus Lucretius. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Paul, and Julian Richards. 1995. The Good, the Bad, and the Downright Misleading: Archaeological Adoption of Computer Visualisation. In Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology 1994. Edited by Huggett Jeremy and Nick Ryan. BAR International Series 600; Oxford: Tempus Reparatum, pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- . Münster, Sander, Wolfgang Hegel, and Cindy Kröber. 2016. A Model Classification for Digital 3D Reconstruction in the Context of Humanities Research. In 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage II: How to Manage Data and Knowledge Related to Interpretative Digital 3D Reconstructions of Cultural Heritage. Edited by Sander Münster, Mieke Pfarr-Harfst, Piotr Kuroczyński and Marinos Ioannides. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nocerino, Erica, Fabio Menna, and Fabio Remondino. 2014. Accuracy of typical photogrammetric networks in cultural heritage 3D modeling projects. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing & Spatial Information Sciences 45: 465–72. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, Rachel. 2017. An Experiment in Using Visual Attention Metrics to Think About Experience and Design Choices in Past Places. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24: 1203–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, Mario. 1992. Metodologia dei restauri borbonici a Pompei ed Ercolano. Rivista di studi pompeiani 5: 169–91. [Google Scholar]

- Paliou, Eleftheria. 2011. The communicative potential of Theran murals in Late Bronze Age Akrotiri: applying viewshed analysis in 3D townscapes. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 30: 247–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliou, Eleftheria, and David Wheatley. 2005. Integrating spatial analysis and 3D approaches to the study of visual space: Late Bronze Age Akrotiri. Paper presented at the XXXIII Computer Applications in Archaeology Conference, Tomar, Portugal, March; pp. 307–12. [Google Scholar]

- Paliou, Eleftheria, David Wheatley, and Graeme Earl. 2011. Three-dimensional visibility analysis of architectural spaces: Iconography and visibility of the wall paintings of Xeste 3 (Late Bronze Age Akrotiri). Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 375–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photoscan. n.d. Now called Metashap. Available online: https://www.agisoft.com (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Photoscan: Merging Chunks. n.d. Merging Chunks in Photoscan Tutorial. Available online: https://www.agisoft.com/forum/index.php?topic=6995.0 (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Piggott, Stuart. 1978. Antiquity Depicted. Aspects of Archaeological Illustration. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt-Rivers, Augustus Henry Lane-Fox. 1887. Excavations in Cranborne Chase, near Rushmore, on the borders of Dorset and Wilts. London: Harrison and Sons, Printers, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Raoul Rochette, Desiree. 1852. Notice des découvertes les plus récentes, opérées dans le royaume de Naples et dans l‟État romain, de 1847 à 1851. Journal des Savants 65–80: 32–47, 296–304. [Google Scholar]

- RealityCapture. n.d. Available online: https://www.capturingreality.com (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- RealityCapture: Error Measurement. n.d. Quality Assessment. Available online: https://support.capturingreality.com/hc/en-us/articles/115001552532-Quality-assessment (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- RealityCapture: Merging Components. n.d. Working with Components Merging. Available online: https://support.capturingreality.com/hc/en-us/articles/115001569011-Working-with-Components-Merging-components (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- RealityCapture: Scale Projection. n.d. How to Geo-Reference the Scene in RealityCapture Using Ground Control Points Faster. Available online: https://support.capturingreality.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001577032-How-to-geo-reference-the-scene-in-RealityCapture-using-ground-control-points-faster (accessed on 21 March 2019).

- Remondino, Fabio. 2011. Heritage Recording and 3D Modeling with Photogrammetry and 3D Scanning. Remote Sensing 3: 1104–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sear, Frank. 2006. Roman Theatres. An Architectural Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Phillip. 2003. Infinite Points. In The City of Sardis: Approaches in Graphic Recording. Edited by Crawford H. Greenewalt. Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums, pp. 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip. 2011. Perspective Systems in Roman Second Style Wall Painting. American Journal of Archaeology 115: 403–26. [Google Scholar]

- Studies in Digital Heritage. 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/sdh (accessed on 3 April 2019).

- Viitanen, Eeva-Maria, and James Andrews. 2008. Storia edilizia e architettura della Casa di Marco Lucrezio. In Domus pompeiana: una casa a Pompei: mostra nel museo d’arte Amos Anderson, Helsinki, Finlandia, 1 marzo–25 maggio 2008. Edited by Paavo Castrén. Helsinki: Otava, pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1994. Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, Colin. 2012. Information Visualization: Perception for Design, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Series in Interactive Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- Ynnilä, Heini. 2012. Pompeii, Insula IX,3: A Case Study of Urban Infrastructure. Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 1998. Pompeii: Public and Private Life. Translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- ZBrush. n.d. Available online: http://pixologic.com (accessed on 20 February 2019).

| 1 | This project represents a collaborative effort of the Virtual World Heritage Lab at Indiana University. Please see the acknowledgements at the end of the article. |

| 2 | Parituclarly in the study of an entire archaeological site, visual program, or domestic structure, it can often be difficult to mentally hold an image of all the small finds, paintings, and architecutre. 3D models can thus be a useful way to “cognitively offload” this information. Once the objects are externalized, it is possible for a researcher to consider interactions that may only occur when observing the entire area wholistically. For a full discussion of the benefits of thinking with visalizations, see (Ware 2012, pp. 1–27). On the benefits for the fields of archaeology and art history in particular, see (Frischer 2008, pp. v–vi; Münster et al. 2016, pp. 7–8). |

| 3 | On the creation of a scale within RealityCapture, see (RealityCapture: Scale Projection n.d.). To ensure that the individual room models align accurately for this case study, the photogrammetric modeling team will collect a geo-referenced laser scan dataset in 2019 and then globally align the state model to this secondary dataset. |

| 4 | The Canon 5DSR averages 60.5 MP per photo and the Nikon D850 averages 45.4 MP per photo. |

| 5 | There are many proprietary software options: (Photoscan n.d.); (RealityCapture n.d.); and (Autodesk ReCap n.d.). For this project, RealityCapture was selected because it easily allows for the alignment of laser scan data and photogrammetric data. |

| 6 | This is an acceptable range for a visualization model (RealityCapture: Error Measurement n.d.). |

| 7 | This is possible through the “component merge” feature of RealityCapture (RealityCapture: Merging Components n.d.), or the “merge chunks” feature of (Photoscan: Merging Chunks n.d.). |

| 8 | This was the subject of a recent MA essay (McClinton 2019). While this was the primary goal for the project, it is worth noting that the Eskenazi Museum of Art, the campus art museum of Indiana University, also wanted to use the resulting visualization as part of a museum exhibit on Roman housing (Gabellone 2009, p. e113) and create a record of the house as it appears today (Forte et al. 2001b, pp. 7–8). |

| 9 | Discussed at length with Viitanen, Eeva-Maria. in Email Correspondence, January, March, and April 2019. |

| 10 | The primary iconographic theme in the garden is Bacchus and his retinue (Falkener 1860, pp. 71–78; Jashemski 1979, pp. 42–43). See (Dwyer 1982, pp. 38–52; Kuivalainen 2008, pp. 127–37) for a complete catalouge of the sculpture. In brief: four oscilla were suspended between the intercolumniations: one square; two resembling an Amazonian pelta; the fourth circular with a sacrifice of a calf on one side, and on the other a bearded man. At the rear of the garden, Silenus inside the fountain niche. On each side of the mosaic niche: two herms: one depicting Bacchus and Ariadne and the other, a male and female Faun. At the front of the garden: two herms of Bacchus and Ariadne and a statue of a Faun attempting to extract a thorn from the foot of a Pan. On the left of the central pool: a Faun with two short horns was found with a pedestal behind. On the left of the fountain: a half herm, half satyr holding a baby goat. Around the central pool, a series of sculptures are arranged in a circle: a panther eating grapes, two identical cupids riding on dolphins, two toads, two birds, a cow, a hind on right, and a goose on the left. |

| 11 | Alternative sculptural arrangements will be further explored in a subsequent reconstruction model. |

| 12 | An excellent model for cultural heritage data is the (Carare Metadata Scheme n.d.). The (London Charter n.d.) provides an excellent example of paradata standards. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McClinton, K.E. Applications of Photogrammetric Modeling to Roman Wall Painting: A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius. Arts 2019, 8, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030089

McClinton KE. Applications of Photogrammetric Modeling to Roman Wall Painting: A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius. Arts. 2019; 8(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcClinton, Kelly E. 2019. "Applications of Photogrammetric Modeling to Roman Wall Painting: A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius" Arts 8, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030089

APA StyleMcClinton, K. E. (2019). Applications of Photogrammetric Modeling to Roman Wall Painting: A Case Study in the House of Marcus Lucretius. Arts, 8(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030089