Abstract

Masks, as a locus of mimetic potential, serve both to typify and to disguise, distilling character traits and translating them visually, even as they hide the visage of those who might wear them, suggesting a performative persona through the partial negation of the form of the actor. As a multi-dimensional depiction, they enable the generation of distance between viewer and viewed, translating an animate individual into an inanimate object and thus, through the intervention of a worked surface, inviting interpretation. To explore the ways that these ideas interact within a domestic space, the article focuses on the House of the Gilded Cupids, interrogating the interplay between materiality and depiction by pairing masks with mirrors, considering the ways in which both media use surface to highlight liminality, eliding viewer and viewed in a complex commentary on the mutability of visual perception. Highlighting the juxtaposition of inset obsidian panels with depictions of reflective surfaces in the mythological wall paintings within the domestic space, the article argues that the conflation of mirror, mask, and reflection within the space enables the viewer to utilize depicted conceptual doubles to both reinforce and undermine the boundaries of the viewer’s embodied reality in order to confront the extent to which an individual is predicated on perception, both internal and external.

1. Introduction

The polysensory multi-valenced interplays within Pompeian domestic spaces invite engagement. As visitors move through the space of a house, they are confronted with a system of quantum-like complexity, with multiple potential interpretations of spatial and social interactions all simultaneously extant. Even as the visitor observes one level of interaction, that observation alters the system, prompting an iterative cycle of insight and reaction. Such interplays are themselves loci of commentary within these spaces, as wall paintings and sculptures, spatial boundaries and environmental mediations are joined and juxtaposed in an exploration of the slippages between experience and perception. While such juxtapositions may be implicit interlocutors in Pompeian houses more generally, in the House of the Gilded Cupids (VI.16.7), they become the focus, as interactions across space and media present an on-going commentary upon the entanglements between mimetic potential and embodied experience, allowing the visitor to confront the mechanisms that enable individuals to enact successful social performances. Even as visitors are met with successive layers of visual and environmental interventions, designed to impress and engage, they confront social processes that otherwise are largely both invisible and uninterrogated.

2. Framing Perception in the House of the Gilded Cupids

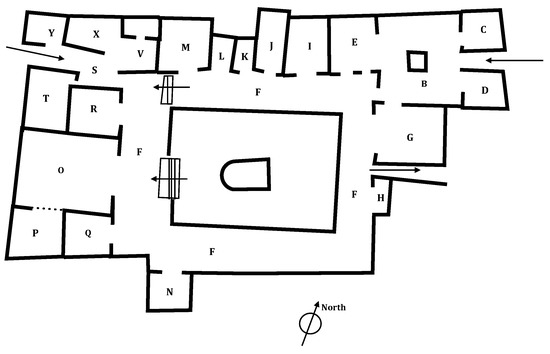

Situated near the gate now known as the Porto Vesuvio, on the north side of the town of Pompeii, in the neighborhood that also contains the intricately programmed House of the Vettii, the House of the Gilded Cupids is notable for the collection of sculpture found in its peristyle, which when considered in conjunction with the preserved paintings and inset wall decor, provides the opportunity to explore the ways in which decorative programs communicate across spatial and material divisions. While houses occupied the lot on which the House of the Gilded Cupids sits as early as the late third century BCE, the current plan dates to the first half of the first century BCE, when two houses that had occupied the space were joined (Powers 2006, p. 46; Seiler 1992, pp. 75–80) (Figure 1). Although restored in the aftermath of the earthquake of 62 CE and subsequent seismic activity, the house retains decorative elements from previous periods, even as it adopts new decorative styles (Powers 2006, pp. 46–48; Seiler 1992, pp. 81–84). Thus, while the figural paintings of Room G (Sogliano 1906, p. 375), to which we will return below, were initially painted at the end of the first quarter of the early first century CE and carefully restored in the period between the earthquake of 62 CE and the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, the wall paintings of Room I, into which were set the gilded medallions depicting cupids that give the house its contemporary moniker, were a new installation in this later period (Powers 2006, p. 48).

Figure 1.

House of the Gilded Cupids, Plan, after Powers (2006). Created by Author.

While other Pompeian houses engage visitors1 and passers-by alike, with axial layouts providing tantalizing glimpses of the peristyle foliage visible through the open doors of the entrance, to engage with carefully decorated interior spaces of the House of the Gilded Cupids, one has to venture within the structure; its intricate commentaries are thus reserved more for invited intimates than for general viewership (Powers 2006, pp. 66–82). Those standing in the atrium itself are confronted by a juxtaposition of depiction and construction. From the entryway, the view is one into space, rather than through it. In the absence of intervening drapes or shutters, a visitor to the atrium could look directly into Room E, its large door framing a wall painting depicting Paris and Helen.

This painting, now partially preserved, is not singular within the Pompeian corpus. In composition and in theme, it is a near double of a painting in the House of Jason (IX.5.18); a comparison of the two paintings makes clear the import of the example at the House of the Gilded Cupids. In the House of the Gilded Cupids as in the House of Jason, a winged putto points toward an open door and the shadowed space beyond, gazing up at Helen, her body fully and appropriately covered by both tunic and mantle. To the left of the door, a seated Paris, his body fully covered by a purple tunic and a diaphanous wrap gazes out at the viewer. While in the House of Jason, the programmatic connections between Paris, Helen, and the rest of the women depicted in the space highlight notions of appropriate dress and potential political dissent, the outward gaze of Paris in the House of the Gilded Cupid draws attention to Paris, and to the open door alongside him, drawing the viewer into closer communication with the imaginal space of the painting.

Even as Helen stands poised at a threshold, so, too does the visitor to this house. While other domestic spaces in Pompeii might signal differential social access by providing glimpses of spaces that may not be entered, in the House of the Gilded Cupids, such inaccessibility is instead indicated in part through this depiction. When standing in the atrium, the view into this space is paired with a view through a physical doorway. Much as the painter obscures the view into the space that Helen has not yet chosen to enter, for the uninvited visitor, the doorway on the west end of the atrium provides only a truncated view into the space beyond, one which for the majority of visitors would remain as obscured as the space beyond the open door depicted in Room E. As Paris gazes out, inviting interaction, full interaction with the space of the house itself is barred to all but a few. Indeed, this differential potential could be underscored by the limits not only of the viewer’s spatial access, but also his or her sense apparatuses. While a visitor with sharp eyesight might be able to perceive these figures from an exterior space, for a more myopic viewer, these figures would appear as a hazy blur, not unlike living figures glimpsed from afar.

The communication between depiction, constructed space, and the visitor that is begun in the interchange between doorways in the atrium and decorations in Room E continues in the spaces beyond; the invitation issued by Paris is one that is insistent as a visitor traverses the house. As visitors move through an inconspicuous doorway on the south side of the atrium into the peristyle space, they experience the play of light and shadow that is made central within the painting of Paris and Helen in Room E. Yet, in this space, what was conceptual becomes experiential, as interpretation gives way to embodied perception. This shift, while prefaced by the painting in Room E is enhanced by a lack of overt architectural signaling in the space of the atrium itself. While in other spaces in Pompeii, the view into the peristyle is carefully framed, as Jessica Powers argues, this “contrast between atrium and peristyle creates an element of visual surprise” (Powers 2006, pp. 93–94).

This surprise, compounded by the influx of fresh air and light, together with the sounds of a splashing fountain, situated at the center of the space, invites further engagements; indeed, the space itself appears to be designed to incite curiosity. For while peristyle spaces, from a functional standpoint, enable perambulation, joining multiple spaces of the house, they do not necessarily enable visual connectivities. Thus, at the Villa of the Mysteries, a low wall divides the intercolumnar views of the peristyle, encouraging the visitor to consider the visual relationships of painted wall, columnar division, and human forms, juxtapositions that are further activated in the space of Room 5 (McFerrin 2015, p. 136). In the House of the Gilded Cupids, however, the peristyle is in active communication with garden space it encloses. The sound of the fountain and the play of light on foliage draw attention towards the center of the space, even as carefully spaced columns and equally carefully situated reliefs, set into the south wall and framed by columns, encourage the viewer to traverse the edges of the peristyle zone (Powers 2006, p. 96).

The sculptures of the garden, which include multiple double-sided reliefs, similarly encourage multi-directional movement. To engage fully with them, the visitor must walk around the peristyle, perhaps even descending into the garden space itself (Powers 2006, p. 97). Such a system highlights privileged accessibility. While other houses frame interior views, highlighting differential access by allowing street-side viewers to view what they cannot fully experience, the House of the Gilded Cupids presents a model of accessibility that depends upon the staging of a set of tiered immersions. Thus, from the street, the viewer contemplates edges that underscore social boundaries. Looking into the atrium from the exterior, the viewer may look directly into Room E, glimpsing distinctions between yellow wall and black socle, but it is not until the visitor enters the atrium itself that the full view into the space is made available, offering the opportunity to consider the painting of Paris and Helen. For many visitors, this experience would constitute the whole of their own engagement with the house. As Helen stands forever suspended on the edge of a threshold, so too would the majority of visitors to the house glimpse the door into the peristyle without the potential to move through it (Wallace-Hadrill 1988, pp. 54–56). That boundary, crossed by the owner’s familia and intimates, gives way into a space in which it is possible to move through frames and around barriers, experiencing a complete view that is forever denied in the paintings that are the focus of the more public spaces of the house, engendering perceptual freedoms that allow the visitor to perform social access, and thus social hierarchy, through the traversal of space.

3. Negotiating Masks

Yet, even as physical access to the space parallels a more conceptual social access through the generation of ephemeral limits that are crossed by visitors as they seek out new viewing vantage points, the sculptures themselves highlight another set of interpretational boundaries, shifting focus to on-going slippages that confound and enable social processes and individual perception alike. For suspended between several of the peristyle columns were oscilla, marble reliefs that hung from colonnaded porticoes (Taylor 2005, p. 83; Wootton 1999, p. 315) (Figure 2). In the House of the Gilded Cupids, several oscilla take the form of theatrical masks. Two of these, one found in the north portico between the first two columns and the second found near the wall of the south portico, depict female theatrical masks (Powers 2006, pp. 187, 196; Sogliano 1907, pp. 590–91). A third, found near the southwest corner of the peristyle, takes the form of a young man, his hair pulled back from his face (Powers 2006, pp. 191–92; Sogliano 1907, p. 591). Carved in high relief, these figures could be apprehended from a distance (Hughes 2014, p. 240). Often discussed in religious contexts that highlight Dionysiac connections or votive functions, or more recently as a component of a theatrical setting, notions that are underscored in this space by persistent Bacchic references within the sculptural program of the peristyle and garden, these depicted masks emphasize and define multiple intersecting liminal zones (Taylor 2005, pp. 86–88; Powers 2006, pp. 189, 194, 214, 216–18, 224–25; Hughes 2014, pp. 242–43).2

Figure 2.

Oscilla hanging in the liminal space between peristyle and garden. House of the Gilded Cupids, Pompeii, ca. 1900. Photograph. Alinari/Art Resource, NY. Used by Permission.

To consider such intersections, I focus here not upon what these masks signal, represent, or reference, but upon what they do; asking questions not of what, or why, but of how (Gell 1998, pp. 16–27). Such a focus on function signals a similar theoretical reassessment, one that attempts to integrate materiality and questions of embodied subjectivity into semiotic debates, and in so doing reintegrate signs and the material world, in an attempt to overcome the separation between the two that scholars such as Webb Keane have argued is one of the most enduring legacies of Ferdinand de Saussure’s conceptualization of semiotics. In privileging “meaning over actions, consequences, and possibilities” such approaches treat objects as a means to an interpretive end, rather than as communicative agents in their own right (Keane 2005, p. 183). Similarly, in a search for meaning, it is possible to become too focused on highlighting one of a range of potential understandings rather than exploring instabilities. Thus, even while depicted masks have agreed upon meanings, meanings that tie them to Dionysiac ritual and theatrical performance alike, these meanings need not remain stable (Keane 2008, p. S214), and the oscilla themselves can become cross-temporal loci of exploration. Thus, we turn now to what masks do, and how the affordances of their materials enable their actions.

For the twentieth-century psychologist James J. Gibson, interaction is predicated upon perception, not only of what something is, but also of what something can do. This emphasis upon what a material can offer, provide, or furnish highlights reciprocal relationships between surfaces and the individuals that use them. Thus, a floor affords support, and it is able to do so because it is horizontal, flat, extended, and rigid, relative to the individual that walks upon it (Gibson 1986, pp. 127–28). Within such a system, a mask has multiple affordances, dependent in large part upon the materials used to create its form. Notions of masking are enmeshed with those of boundary building. As modes of dress, masks function much like a bracelet or a breastplate, as a rigid marker of the distinction between the wearer and the space beyond. Such boundaries are both reciprocally informing and reciprocally restrictive.

When wearing a mask, the interface of the firm materials of the mask itself and the mobile face of the wearer amplifies the wearer’s experience of his or her own features, even as it hides them from the viewer. Such shielding is often tied to deception, to the manipulation of body imagery. By concealing one set of identity markers, another set can be effectively substituted (Pollock 1995, p. 584). Such deceptive capacities, enabled by the opaque materials of the mask itself, allow actors to persuade audiences to perceive alternate realities. The firm surface of the mask elides the boundaries between reality and fantasy by translating the mobile surface of the face into the fixed form of a stable depiction, transmuting the human form from public art into an imaginal zone that parallels the paintings upon Pompeian walls. Given the multivalent potentialities of masks, both worn and depicted, it is perhaps not surprising that in the House of the Gilded Cupids, the oscilla suspended around the peristyle depict a suite of figures—maenads, a satyr, and a silenus—associated with a particular masked deity, Dionysus, who was known for eliding boundaries and altering perceptions. As Shelley Hales has noted, masks are so tied to Dionysus that the god could be worshipped as a mask. The mask marked the god’s “slippery character” as suspended masks, like those encountered by visitors to this space, mark both absence and presence. As Hales states, “their suspension and disembodiment reveal them to be empty, but their ability to stare out… makes them an unnerving presence” (Hales 2008, pp. 237, 239). Such manipulations of perception are not limited to masks, indeed social performances that extend beyond the theatrical stage onto the stages of the Pompeian house similarly rely on the careful crafting of personal identities. Much as masks might allow an actor to put on a new social role, social actors in the space of a Pompeian house might turn to dress to highlight and maintain social position.

Masks can then be conceptualized as part of an on-going negotiation of self-presentation, one that is undertaken through a range of bodily modifiers. Indeed, if masks are a form of dress accessory, with rigid forms that encircle a portion of the body, emphasizing and isolating it simultaneously, then masks function in parallel to adornments such as jewelry (Cappellieri and Romanelli 2004, p. 25). For even as masks create a stable external image, they form a material boundary that is mutually perceptible, serving not only as a communicative tool, but as a haptic negotiation of the edges of the wearer’s physical form. By considering poly-sensorial interplays, integrating a range of sense modalities beyond sight, masking becomes a process that is not only externally driven, but internally informing. The integration of the wearer into the interpretive system highlights a broader range of potential and unstable experiences. The body is thus not only a sight of display, or a medium through which to communicate; it is itself “constitutive of our social world” (Bulger and Joyce 2013, p. 70).

For the wearer, the touch of the mask against skin offers the opportunity to experience what is otherwise difficult to perceive—the shape of one’s own face. Masks facilitate external communication through the generation of distance. Indeed, distance is key for multiple perceptive processes. To engage visually, the viewer must be physically removed from the thing he or she sees; viewing is, at its core, a lack of embodiment. While a person might be aware of the movement of components of the face, and can feel the act of smiling, or blinking, or furrowing one’s brow, that person cannot see such acts unless the form is projected outward. To see is to be separated. Masks underscore such separation for viewers, even as they undermine it for wearers.

If sight depends on separation, touch requires proximity. As the surface of the mask presses against the surface of the skin, the wearer has the opportunity to perceive a broader range of facial features than he or she might otherwise confront. The interjection of an opaque surface prevents external visual engagement, even as it enables self-perception. While the mask helps to objectify the wearer for the external viewer, distilling the on-going process of facial communication into a readily observable form, it simultaneously serves to prompt self-scrutiny. As the wearer’s face presses against the interior of the mask itself, the wearer has the opportunity to encounter their own form from another perceptive angle, inviting self-objectification that can facilitate individual reappraisal which can, in turn, facilitate participation in shared activities, as individuals consider their own actions in relationship to those of groups (Strauss 2009, pp. 35–38).

Yet, even as the affordances of the material of masks prompts haptic negotiations for the wearer, social objects have multivalenced communicative potentials. They are “Bohrian” because “like the affordances of subatomic set-ups they may have contradictory manifestations or displays, for example, a set up can afford a display of particles or a display of waves, but not both at the same time and place” (Harré 2002, p. 27). Much like faces themselves, one cannot simultaneously wear a mask and look upon its features. Yet, even as masks enable proximal interaction with the face of the wearer, they distance that wearer from the viewer. Masks then are an “excarnation,” a means of visual disembodiment, one that distills and distances simultaneously (Belting 2017, p. 19). Even as masks enable self-perception, they facilitate self-othering, placing communicative power in the hands of the wearer by privileging a single, planned performance, one that is constructed around interdependent tensions. Masks depend upon distance, yet they simultaneously help to negotiate it. The interior form of the mask could help to amplify the voice of an actor, while the exterior features of the mask underscore the distinctions between the unseen face of the wearer and the fixed form presented to the viewer. In this, they distill not only a desired expression or type of character, but also the enmeshed practices of viewership and social recognition.

Much as a mask’s form enables haptic negotiation on the part of the wearer, it also facilitates a contemplation of viewing practices, highlighting both the separation inherent in the process and the gaze itself. Theatrical masks provide mechanisms for sight as a matter of practicality; there must be some manner of eye-hole to allow the actor to see. The mask mediates perception, preventing direct engagement with the majority of the wearer’s face. Yet, even as the mask forces separation, it offers the potential for reciprocal interaction, an interaction focused not upon a range of expressions shared between faces, but through another distillation. Masks allow reciprocal interaction across a single focal point—the eyes (Belting 2017, p. 7).

If mimetic potential enables connections between the body of the perceiver and that of the perceived, as Michael Taussig contends (Taussig 1993, p. 21), then such connectivities are predicated, in part, upon perceived potential for reciprocal interactions; an individual is thus “defined and sustained” through comparison with an exterior other (Taussig 1993, p. 237). On both the personal and the communal level, if there is a perception of shared experience, if others are seen as a “you” rather than an “it” in the words of Eduardo Kohn (2013, pp. 1–2), then this occurs as a result of complex internal processes that allow individuals both to formulate perceptions of themselves, while simultaneously determining commonalities between internal landscapes and exterior worlds. For interactions across a mask, even as the material of the mask itself generates a boundary, the eyes of the wearer, when caught in a reciprocal exchange with the viewer, serve to elide it. Such notions are underscored etymologically, much as the Greek πρόσωπον references both the mask, the dramatic part, the person, and the face, the Latin persona, indicates both the mask as object and the role it references (Napier 1986, p. 8). The mask reinforces the person, rather than supplanting them; even as the eyes of the wearer enliven the viewed mask, they highlight the connection between the masked face and the unmasked one.)

The visible presence of the wearer’s eyes signals a conceptual conundrum, another nested paradox in the interpretive system. If to be mimetic is to approximate reality, then the mimetic is by definition not reality. Yet, to be comprehended, it must be perceived, suggesting that experience, perception, and material reality are distinct, if intersecting spheres. In the House of the Gilded Cupids, we encounter not masks, but depictions of masks, representations of representations that invite thought more than interaction. If theatrical masks are a locus of mimetic potential, in part because they facilitate interpretation of the human form through externalization, then depictions of masks externalize the masks themselves, inviting the viewer to think about mimetic processes, serving as a sort of memento depicti.

4. Mirroring and Externalized Embodiments

While the visitors may inhabit the space of the peristyle, as they gaze from the space of the garden towards the painted rooms visible from within it, they are reminded of the utility of depiction. As these depicted masks hang between peristyle columns, overseeing the physical boundaries between the garden and the ambulatory space of the peristyle, they reinforce the conceptual boundaries between what it is possible to see and what it is possible to experience. Indeed, the form of the oscilla themselves underscore such thoughts. Although they have both curved backs and pierced eyes, which would facilitate wearing, the weight of their materials, and the height at which they would have hung, both prevent even an adventurous visitor from fitting them against the face. Even as intervening environmental conditions might shift these depicted masks, generating movement that could animate the space, drawing further attention to them, their position precludes a normative wearer. Like the painting of Paris and Helen in Room E, they comment upon an interaction that they do not allow.

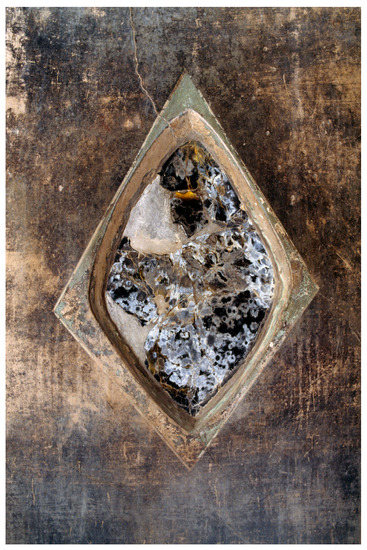

Yet, much as the door to the peristyle creates the possibility of access that is denied in the depictions of Room E, visitors who see the potential for externalization in the forms of the mask are met with the reality of it on the north end of the space. Set into the plaster of the wall alongside the door that links peristyle to atrium is an obsidian mirror (Figure 3).3 The reflective surface of the mirror draws the form of the visitor into direct communication with the reciprocal interchanges made material in the form of the oscilla of the peristyle, further integrating the ephemeral interactions, both internal and external, that occur throughout the space into the visual program. While the visitor may have suspected that the space offers comment upon processes that resonate beyond the realm of the conceptual, the presence of a mirror both reinforces and expands upon such an interpretive framework.

Figure 3.

Inset Obsidian, House of the Gilded Cupids, Pompeii. De Agnostini Picture Library/Archivo J. Lange/Bridgeman Images. Used by Permission.

Such integrations themselves bridge conceptual and material boundaries, for even as the placement of this obsidian mirror in the interstitial zone between two doors arrests the visitor’s attention as he or she turns from the sculptures of the peristyle towards the painted program of Room G, it doubles the surface into which it is set. As Bettina Bergmann has noted, the black painted walls that surround the portico space were themselves reflective, polished with marble dust, they had the capacity to echo the forms of vegetation, sculpture and visitor alike (Bergmann 2008, p. 57). Inset mirrors serve to amplify a form of engagement that immerses the space, clarifying the interaction even as they reflect the image of the visitor. Such surfaces highlight movement and form more than particulars, creating, as Verity Platt argues, “an ambiguous, unstable form of figurations that parallels the faux-marble face” (Platt 2018, p. 266). For while obsidian is reflective, the reflections that it generates are more echoes than likenesses, generating an interplay of movement and form, without capturing detail; more like the polished walls in which they are set than modern silver backed mirrors, these obsidian panels make briefly and imperfectly perceptible what is an otherwise internally embodied interaction. It is through this iterative reinforcement that the visitor begins to comprehend the mutually constitutive nature of perception, experience, and matter. The presence of a visitor, otherwise ephemeral and largely unmarked becomes, for a moment, a visible component of the program of the space—a fleeting mark of a fleeting presence.

This momentary externalization highlights a nested paradox. The marble masks that hang from the eaves of the peristyle highlight the motion of the face by stilling it; the transmutation of skin to stone makes permanent and comprehensible what is otherwise infinitely changeable. Similarly, the tangible physical form of the visitor is underscored through the generation of a transient marker—a reflection. While this image may be an impermanent addition to the visual program of the space, it offers an opportunity for self-othering, the chance to view what is otherwise embodied, to see, for a moment, as if with the eyes of another. As the internal surface of a mask activates a haptic engagement that externalizes and therefore underscores a sense of embodiment, the mirror provides the opportunity to exchange a reciprocal gaze, not with another, but with oneself. If it is through reciprocal gazing that we acknowledge shared perception, then such self-reflexivity further underscores our roles as active perceptive agents, a role that we fully recognize when we meet our own gaze.

In making the individual a perceived other, the mirror provides insight not only into internal processes, but also into broader interactions. While the mirror provides the opportunity to view as a whole what might otherwise be perceived as haptic fragments, it does not provide a fixed image. Indeed, even when we gaze upon the face of another, we do not encounter an unchanging form. For our gaze itself forces adaptation. As Matti Fischer argues, “society manifests itself concretely through the gaze of another human” (Fischer 2001, p. 32); when one person looks upon another, this perceptive connection is itself a social situation, one to which the viewed responds, moderating expressions as part of the on-going social performance. The reciprocal gaze is thus both mutually constituting and mutually constitutive. The reflection thus acts as its own kind of mask (Taylor 2005, p. 100), presenting the face of the viewer as an externalization, an object to be interpreted. It is in this interpretation that the gaze becomes fully reciprocal; in considering him or herself, the viewer acts as both subject and object, and through such an act, has the capacity to appreciate the subjectivity of other viewed actors.

Conceptualizations of intersubjectivity, of reciprocality that is both internal and external (Gallese 2009a, p. 6), project notions of mimetic potential from the imaginal zone of reflection and depiction into the performative interactional space of the house itself, wherein visitors and owner alike are engaged in continuous process of social negotiation. Such negotiations are similarly structured around tensions. Even as individuals seek to promote their exceptionality within the group, they balance this desire with their wish to remain part of the group. If to be exceptional is to be excluded, then those who would seek to distinguish themselves must remain cognizant of the boundaries that may be overcome, and those that must be maintained. In this, the notion of mirroring is once more central.

Mirroring is embedded in social interactions. Facial mimicry, the observation and imitation of expressions correlated to emotions, depends upon “embodied simulation” as much as it does upon interpretive analogy (Gallese 2009a, p. 10). Understanding is predicated upon the recognition of a shared system. While social identification may be embodied in shared neural circuits, in an intercorporality that allows for the “mutual resonance of intentionally meaningful sensory-motor behaviors” (Gallese 2009b, p. 11), the similarities that arise from shared embodiment are not the endpoint of a social dialogue, but an entryway. Indeed, the mirroring of emotion itself constitutes a system of social communication, delivering information about an individual’s relationship to a larger social system (Gallese 2009a, p. 11) one that is not intrinsic, but taught through the observation of individuals who are fully incorporated into the desired group. Studies on infants suggest that such imitative systems are dependent upon recognition of similarities between what is seen and what is felt, that it is through interpreting another as a second self, that an individual is able to develop (Meltzoff 2007, pp. 130–37). Individuals are discursive entities.

5. Doubling and Second Selves in Room G

While cognitive scientists considering such ideas reference mirror neurons (Rizzolati and Craighero 2004, pp. 176, 183–84) and Lacanian philosophers and psychoanalysts discuss the mirror stage (Lacan 1977, pp. 1–8; Athanassopoulos 2012, p. 4; O’Neill 1986, pp. 202–3), visitors to the House of the Gilded Cupids turn to another set of references to consider the connections between reciprocity, reflection, and social interaction, one that is at the forefront in the room situated directly alongside the embedded obsidian mirror: Room G (Figure 4). Situated between attenuated columns and placed against a background that, in some areas of the room, appears to have once been black, the figures of the paintings of Room G continue the discourse prompted by the reflective walls of the peristyle. While dark walls served as reflective surfaces in the peristyle, integrating the form of the visitor into the visual program of the space, in Room G, depicted figures are framed by similar visual devices, further conflating imaginal and real, heightening the ability of the depictions to comment upon the visitor’s experiences. Indeed, the commentary upon reflection and externalization that is evident throughout the peristyle space is reinforced within the depictions of Room G, all of which include a depicted reference to another type of mirror.

Figure 4.

View into Room G from the peristyle, House of the Gilded Cupids, Pompeii. Robert Harding/Alamy Stock Photo. Used by permission.

On the north wall of the space, a seated woman, her body covered in a pale tunic and bright blue mantle, rests her head, no longer extant, upon one hand, her body twisted toward a man with a lame foot who holds a shield upright for her perusal; a helmet and greaves lean against the base of her chair. Behind this man, two other male figures sit, one straddling a workbench, his hands hovering above a vessel, as if in the act of working it (Figure 4). Such depictions of Thetis in the workshop of Hephaestus are not uncommon in the Pompeian corpus. Compositionally, this depiction in Room G is nearly identical to one in the House of Siricus (VII.1.47), which is situated in a space that similarly connects the depiction of Thetis and Hephaestus to depictions of theatrical masks, this time placed in the hands of Muses (Carrateli and Baldassare 1996, p. 279).

Yet, while both compositions center upon the shield, their treatments of the armament differ. In the House of Siricus, a winding band meanders in defined bends across the depicted surface of the shield, characteristic of a river, suggesting that this iteration of Achilles’s armor references Homeric descriptions, in which the shield of Achilles becomes an ekphrasic excursus on the structure of the cosmos. Like the surfaces the shield references, ekphrasis itself is entwined with processes of perception and othering. As words describe images, they invite the reader to contemplate the process of viewing, and in the process to evaluate its mechanisms and ambiguities. As James Francis argues, “the image refers back to the absent model just as ekphrasis refers back to its absent image, ekphrasis makes the absent present; it conveys both presence and absence at the same time” (Francis 2009, p. 7). As the fleeting shadows of living visitors are briefly inscribed onto the walls of the peristyle through the intervention of polished walls and obsidian insets, thus highlighting both the presence of the visitor and the ephemerality of that presence, the shield of Achilles, in both its Homeric iteration and in the House of Siricus, encapsulates what cannot be bound, providing insight into concepts that are both vast and intangible.

Such ekphrastic exchanges revolve around a confrontation with the other. Even as texts “encounter their own semiotic others” (Mitchell 1994, p. 156), in the House of the Gilded Cupids, the viewer confronts herself as other. Here, Thetis looks upon, not the river Ocean and scenes of war and peace, but upon a gleaming surface, a rarity within the corpus of such compositions, appearing in only two other Pompeian houses (Taylor 2008, p. 153). While in examples such as that from house IX.1.7 in Pompeii, Thetis’s reflection is clearly visible (Figure 5), in the House of the Gilded Cupids, her projected form is more amorphous. While fragmentary, the extant portion of Thetis’s figure suggests that her right hand rests against her face, perhaps in a gesture of contemplation common in such images. Similarly, her body turns to suggest that her gaze is fixed upon the shield (Figure 4). Given the lack of ornamentation on the shield itself, it is likely that the polished surface would be understood as a reflective one, with the pale blue wash upon the edge of the shield perhaps referencing the form of Thetis. Even without a clearly depicted reflection, the smooth surface of the shield shifts the interpretive emphasis from the armor to Thetis. Rather than highlighting the virtuosity of a verbal, visual, or material craftsperson, this shield provides Thetis with the opportunity to confront herself.

Figure 5.

Thetis in the Workshop of Hephaestus, Room E, IX.1.7, Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, MANN 9529. PRISMA ARCHIVO/Alamy Stock Photo. Used by permission.

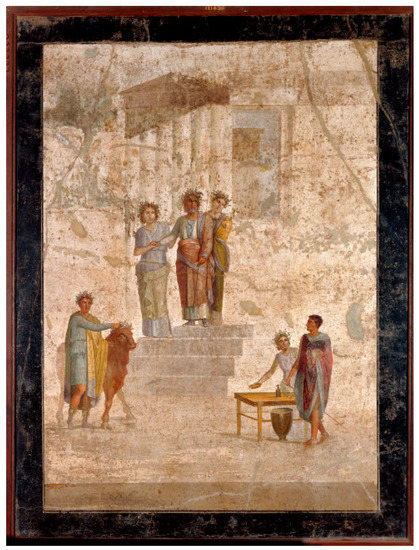

This invitation is equally insistent in the painting that mirrors this one within the space of Room G. On the south wall of the space is another painting with a potentially Illiadic connection (Figure 6). In this depiction, a figure with the tanned skin common to men depicted in Pompeii, his form draped in deep red fabric with a pale blue border, sits in the center of the composition; a shield leans against the right side of his raised seat. To the right, an unbearded man in a light blue tunic leans his elbow against his companion’s seat, his chin caught in his fingers, a gesture of contemplation that doubles that of Thetis on the opposite side of the space. To the left of the seated man, a woman with red hair gathered into a low chignon gazes over her bare right shoulder, her right hand catching the fabric of her pale lavender tunic. While the head of the seated figure is no longer extant, and the standing man looks down at the reflective surface of the shield, this woman gazes out of the frame into the space of the viewer.

Figure 6.

Briseis, Achilles and Patroclus, Room G, House of the Gilded Cupids, Pompeii. Age Fotostock/Alamy Stock Photo. Used by permission.

Like the painting of Thetis, this depiction highlights interplays between viewer and viewed, utilizing the surface of the shield as a tool that, like a mirror, allows for the externalization of the form of the viewer. Such visual connections may be underscored by the identifications of the figures. Unlike the depiction of Thetis and Hephaestus on the north wall, the identification of these figures is less certain. Both Antonio Sogliano and Florian Seiler associate the seated woman with Briseis, the war captive at the heart of conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon (Sogliano 1908, pp. 31–32; Seiler 1992, p. 111; Powers 2006, p. 121). The potential identities of her male companions have been variously identified as a seated Agamemnon and contemplative Achilles or as a seated Achilles and a contemplative Patroclus (Newby 2016, pp. 175–76). Such difficulties need not impede interpretation; indeed, as Bettina Bergmann has noted, formal parallels do much to underscore thematic connections (Bergmann 1994, p. 245). Viewers familiar with the range of intersecting stories associated with Thetis and Briseis might take the repeated shield as a conceptual jumping off point.

As the standing figure contemplates his reflection, he externalizes an internal process, and in doing so, completes the ekphrasic circle begun on the north wall. As images are a semiotic other from the perspective of words, words are a semiotic other from the perspective of images. Much as simile and divine intervention serve to externalize internal processes in Homer’s texts (Strauss Clay 1997, p. 136), in these depictions, reflection allows the opportunity to consciously interrogate what might otherwise be fleetingly experienced. The juxtaposition of these two scenes together with the centrality of the shield within both invites the viewer to consider the personage that connects the two scenes—Achilles.

The hero is exceptional, and in his exceptionality, he is isolated, tethered to humanity through an externalization, an individual who embodies the traits that Achilles must deny to successfully undertake his destructive mission. This individual is Patroclus, the living complement to Achilles, the hero’s second self (Van Nortwick 1996, pp. 39–61). While these two figures are intimately connected, they cannot be fully equated. The visual merging of the two undertaken in Book 16 of the Iliad, when Patroclus takes up the arms of Achilles, highlights the disjunction between external performances and internal processes. Although Patroclus may look like his friend, he does not have Achilles’s skill. Both his life and the armor are lost, prompting Thetis to seek out new armor from Hephaestus. This struggle between external and internal, between performance and experience, is foregrounded within the space of Room G through the reflection of depicted figures, who, like the visitors themselves confront the performances that both undermine and underscore social interactions.

The third painting in Room G subverts the expectation of the visitor. If the north and south wall are engaged in a dynamic interplay highlighting self-conscious viewership and the utility of self-awareness in social performances, the central panel of the room, situated on the east wall, opposite the entrance to the space, reframes the visitor’s understanding of this conversation (Figure 4). In this painting, to the right, a beardless man with close-cropped hair wearing a single sandal stands alongside a simple table. Two women stand across from him, their hair bound with greenery. One holds a shallow dish, possibly a patera. On the opposite side of the painting, a man draped in pale blue with tall boots leads a bull into the frame, his hand settled upon the animal’s head as the animal gazes out of the frame. In the center of the composition, a man and two women, their figures only partially extant, make their way down a flight of stairs (Figure 4).

The foregrounding of footwear suggests the identification of the scene as one described in the opening lines of the Argonautica. Jason, previously dispossessed of his position in Iolcus by his half-uncle Pelias, confronts the latter as he makes a sacrifice to Poseidon. Pelias, recognizing Jason as the man prophesied to bring about his downfall by virtue of the fact that he wears only one sandal, sets into motion a series of events that will culminate in his downfall, through the agency of Jason’s wife, Medea (Apollonios Rhodius. 1.5–1.6). In many ways, the story of Jason mirrors integrative social processes. For Jason, unaware of the larger contexts within which he operates, has only a limited grasp of the interactions that swirl around him. Such interactions would similarly have been ongoing within the space of Room G itself.

While Room O is the only space within the house marked with the floor pavements that denote triclinia, Room G is sizeable enough to have served as a dining space (Powers 2006, pp. 87, 91). Such spaces necessitate the self-aware self-presentation highlighted by masks and mirrors in the peristyle, and underscored by the paintings within the room itself. It is within such spaces that visitors might display their erudition, putting on a social performance with the potential to underscore exceptionality or to undermine social pretentions. Here, in-group hierarchies are both crafted and maintained, through careful interpretation of both the space itself and the social codes that dictate behavior within it. Sophisticated visual programs, such as those in the House of the Gilded Cupids, offer the opportunity to perform social standing, a standing that might be based as much upon knowledge differentials as upon monetary resources (McFerrin 2015, pp. 265–68). It is fitting that Jason, whose story highlights distinctions between situational and self-knowledge, is visible from multiple spaces that might have been interactional loci. The large entryway of Room G makes the rear wall visible elsewhere in the peristyle, particularly from Room O (Powers 2006, p. 89), another space in which competitive conversations likely took place.

Such conversations need not center primarily around literary referents. Like the depiction of Paris and Helen in Room E, the painting of a one-sandaled Jason confronting Pelias is nearly identical in composition to a painting from the House of Jason (Figure 7); indeed, that iteration of the image gives that house its colloquial name. The iteration of the image in the House of Jason highlights the hero’s lack of situational knowledge through a juxtaposition of gazes. Pelias stares down at the young hero, his widened eyes emphasizing the import of his realization. His daughter, standing alongside him, tilts her head as she looks upon Jason. Like the hero, she is unaware of the implications of the newcomer. Like Jason, she does not yet realize the fate that awaits her. The state of preservation of the painting from Room G prevents direct comparison of these figures, but it offers up a compositional shift suggestive of a similar shift in focus.

Figure 7.

Jason and Pelias, Room F, House of Jason, Pompeii. Fotografica Foglia. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, MANN 111436. Scala/Art Resource, NY. Used by Permission.

In the example from the House of Jason, the sacrificial bull mirrors the king. The gaze of the animal is similarly fixed upon Jason; its eyes are widened. The coat of the bull and the skin of the king are nearly identical in shade. Like Pelias, the bull appears to foresee its fate. Unlike Pelias, it does not attempt to circumvent it, suggesting that the bull is perhaps the most self-aware actor in the depiction. However, in Room G, the bull gazes, not at the hero, but away from him, shifting the viewer’s attention from an interplay of reciprocal gazing, to the interjection of another potential means of self-recognition. While in the House of Jason, the two daughters of Pelias occupy their hands with aiding their father, in the House of the Gilded Cupids, one daughter holds another visual link, one which invites the viewer to reconsider Jason’s relationship to the notion of self-perception. Just above the hero’s head, one of the women holds a round shield, a visual double for the shields that are central to both the compositions and the narratives of the paintings on the north and south walls of Room G.

Thetis seeks out a new shield for her son, and then contemplates her reflection in it; Patroclus gazes down upon the armor that serves both to connect him visually to his second-self and to highlight his ultimate distinction from him. In both situations, shields are both a component of the established narrative and appropriate to the space. The procurement of armament is the point of Thetis’s trip to Hephaestus’s workshop. Armor is logically to be found in the vicinity of heroes who, at least occasionally, find themselves on the battlefield. But there is no particular reason why a woman might decide to wield a shield in the midst of a sacrifice. Apollonius Rhodius mentions no shield in this portion of his narrative, nor does a shield appear in the example from the House of Jason. This intervention appears to be one made in response to the program of the House of the Gilded Cupids.

Much as Jason’s narrative stands apart from the stories of the Trojan cycle that bracket it in Room G, this shield is similarly distinct from its depicted fellows. It does not appear to reflect any of the figures depicted within the scene. Thetis’s hazy reflection is suggested upon the shield on the north side of the room. Patroclus’s form is visible in the shield on the south. Both Thetis and Patroclus gaze upon these polished surfaces, their hands lifted in gestures of contemplation that underscore their engagement. While the face of Jason is not preserved clearly enough to track his line of sight fully, the tilt of his head suggests that he looks, not up at the shield, but across the frame, perhaps at the attendant who leads the sacrificial bull. Like his counterpart in the House of Jason, this iteration of the hero is similarly trapped within a moment that he cannot fully comprehend. However, while the depiction in the House of Jason highlights Jason’s lack of knowledge through juxtaposition, here, Jason is provided the opportunity to experience reflective reciprocity, and through this to interrogate himself as a social actor. He neglects to do so, an action that, within his own larger narrative, leads to the destruction of his line.

The interactions across this space function as a set of interrelated microcosms, yet these microcosms are not disconnected from the experience of the viewer. Beyond the mirror that prefigures the interplays within the space, inviting the visitor to conceptualize him or herself as an image, the dress of the depicted figures comment upon contemporary norms. The twisting snake bracelet that winds its way up Thetis’s arm has direct parallels within the material record of the site of Pompeii; a similar set was excavated at the House of the Faun. The thin gold bracelets that adorn the wrists of both the woman holding the dish in the central panel and of Briseis are similarly well-attested (Deppert-Lippitz 1996, pp. 132–34). Similar adornments would likely have been worn by the women who visited the space, further emphasizing the connections between the space of the visitor and the space of depiction.

Dress provides a final link within the depictions of Room G. Even as Jason overlooks the potential for reflective viewing, his blue-bordered red tunic ties him to another depicted individual whose lack of self-knowledge, or perhaps self-acceptance, brings pain to those around him. On the south side of the space, Achilles sits, similarly attired in a blue-bordered red tunic. Like Jason, he fails to contemplate either of his doubles. For unlike Jason, Achilles is provided with multiple opportunities to engage with an externalization of himself. A set of polished disks sits alongside him. His own double, Patroclus, leans into his space. The position of his legs and the twist of his hips suggest that he looks, not at these externalized others, but at Briseis, who denies him the opportunity to share a reciprocal gaze by engaging the viewer.

Briseis’s outward stare further entangles the viewer into this set of recursive reflections, wherein self and other are iterated and re-iterated across liminal zones, with the visitor perpetually caught in the middle. In Room G, the visitor sits or stands in the midst of an ongoing commentary on the utility of self-evaluation. In the peristyle, the visitor walks between reflective walls and hanging masks, replicating the labyrinthine process of personal self-reflection. This process is underscored in Room G, where depicted reflective surfaces and depicted viewers alike encourage the visitor to the space to enter into a reciprocal process of generation. Much as mimetic interactions reinforce social relationships, the realization that one is engaged in such a process allows an individual to become an effective social actor. If the shield held by one of the two daughters of Pelias in Room G comments upon Jason’s inability to engage in both self-reflection and reflective reciprocity, it affords an opportunity to the visitor. The smooth surface of the depicted shield reflects nothing, its surface reflecting neither the figures within the scene nor the figures who move through the room that it faces. The visitor, confronted with his or her reflection upon entry into the space, is forced to consider the import of that reflection through confrontation with another potential surface of interaction. If the visitor wishes to be an effective social actor, he or she must be aware both that mirroring is possible and that one may choose what to mirror.

Even as Homer externalizes internal processes, making patterns of thought evident by removing them from the inner landscape of the mind, thrusting them into and onto individuals, the House of the Gilded Cupids distills and reiterates the processes through which individuals frame their relationships to their social groups, highlighting the mechanisms that might equally prompt inclusion and destruction. In this confrontation, individuals are offered the opportunity to perceive themselves, not as others perceive them—as a nexus of social expectations and pressures that adorn the body which responds to them through daily performance—but as an inverse, set by the affordances of surrounding surfaces into a world of opposites, a two-dimensional zone that, like a painting, can be analyzed and perhaps even understood.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Elaine Gazda both for introducing me to the possibilities of the Pompeian corpus and to making a detour to explore the House of the Gilded Cupids, to Megan Cifarelli for mountains of theoretical insight, to Jessica Powers for her painstaking work on this space, to Susan Siegfried who showed me how to look with new eyes, to Thomas Van Nortwick who introduced me to the second self, to Geoff Pollick who entertained wild early iterations of this idea, to Regina Gee, whose warmth and good humor made much possible that would have otherwise been impossibly difficult, and to the comments of the anonymous reviewers whose thoughts made this work stronger.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Athanassopoulos, Vangelis. 2012. Why Do Vampires Avoid Mirrors? Reflections on Specularity in the Visual Arts. Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 4: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans. 2017. Face and Mask: A Double History. Translated by Thomas S. Hansen, and Abbey J. Hansen. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 1994. The Roman House as Memory Theater: The House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii. The Art Bulletin 76: 225–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2008. Staging the Supernatural: Interior Gardens of Pompeian Houses. In Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture around the Bay of Naples. Edited by Carol Mattusch. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger, Teresa, and Rosemary Joyce. 2013. Archaeology of Embodied Subjectivities. In Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Archaeology: A Companion to Gender Prehistory. Edited by Diane Bolger. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellieri, Alba, and Marco Romanelli. 2004. Il design della gioia: Il gioiello fra progetto e ornamento. Milan: Charta. [Google Scholar]

- Carrateli, Giovanni Pugliese, and Ida Baldassare. 1996. Pompei, Pitture e Mosaici. Roma: Instituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Deppert-Lippitz, Barbara. 1996. Ancient Gold Jewelry in the Dallas Museum of Art. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Matti. 2001. Portrait and Mask, Signifiers of the Face in Classical Antiquity. Assaph: Studies in Art History 6: 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, James A. 2009. Metal Maidens, Achilles’ Shield, and Pandora: The Beginnings of ‘Ekphrasis’. American Journal of Philology 130: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, Vittorio. 2009a. The Two Sides of Mimesis: Girard’s Mimetic Theory, Embodied Simulation and Social Identification. Journal of Consciousness Studies 16: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese, Vittorio. 2009b. Mirror Neurons, Embodied Simulation, and the Neural Basis of Social Identification. Psychoanalytic Dialogues 19: 519–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, Alfr. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, James J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, Shelley. 2008. Aphrodite and Dionysus: Greek Role Models for Roman Homes? Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome Suppl. 7: 235–55. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom. 2002. Material Objects in Social Worlds. Theory, Culture, and Society 19: 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Lisa A. 2014. Sculpting Theatrical Performance at Pompeii’s Casa degli Amorini Dorati. Logeion: A Journal of Ancient Theater 4: 227–47. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2005. Signs are Not the Garb of Meaning: On the Social Analysis of Mateiral Things. In Materiality: An Introduction. Edited by Daniel Miller. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2008. The Evidence of the Senses and the Materiality of Religion. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14: S110–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1977. The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function, as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience. In Ecrits: A Selection. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Routledge, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- McFerrin, Neville. 2015. The Art of Power: Ambiguity, Adornment, and the Performance of Social Position in the Pompeian House. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff, Andrew. 2007. ‘Like Me’: A Foundation for Social Cognition. Developmental Science 10: 126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1994. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, David A. 1986. Masks, Transformation and Paradox. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, Zahra. 2016. Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture: Imagery, Values, and Identity in Italy, 50 BC–AD 250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, John. 1986. The Specular Body: Merleau-Ponty and Lacan on Infant Self and Other. Synthese 66: 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Verity. 2018. Of Sponges and Stones: Matter and Ornament in Roman Painting. In Ornament and Figure in Graeco-Roman Art: Rethinking Visual Ontologies in Classical Antiquity. Edited by Nikolaus Dietrich and Michael Squire. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 241–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Donald. 1995. Masks and the Semiotics of Identity. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 1: 581–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, Jessica. 2006. Patrons, Houses, and Viewers in Pompeii: Reconsidering the House of the Gilded Cupids. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolati, Giacomo, and Laila Craighero. 2004. The Mirror Neuron System. Annual Review of Neuroscience 27: 169–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, Florian. 1992. Casa degli Amorini Dorati (VI 16, 7.38). Häuser in Pompeji, Volume 5. Munich: Himer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Sogliano, Antonio. 1906. Pompei—Relazione degli scavi fatti dal dicembre 1902 a tutto marzo 1905. Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 374–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sogliano, Antonio. 1907. Pompeii—Relazione degli scavi fatti dal diecembre 1902 a tutto marzo 1905. Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 549–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sogliano, Antonio. 1908. Pompei—Relazione degli Scavi fatti dal decembre 1902 a tutto marzo 1905. Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm L. 2009. Mirrors and Masks: The Search for Identity. London: Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss Clay, Jenny. 1997. The Wrath of Athena: Gods and Men in the Odyssey. London: Bowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Taussig, Michael. 1993. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Rabun. 2005. Roman Oscilla: An Assessment. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48: 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Rabun. 2008. The Moral Mirror of Roman Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nortwick, Thomas. 1996. Somewhere I Have Never Travelled: The Hero’s Journey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1988. The Social Structure of the Roman House. Papers of the British School at Rome 56: 43–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, Glenys E. 1999. A Mask of Attis ‘Oscilla’ as Evidence for a Theme of Pantomime. Latomus 58: 314–35. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Here, I use the term visitor to denote individuals outside the familia who might have been given access to the house. Following Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, I assume here that those of higher social rank would have had greater access to the most interior spaces, while a greater variety of individuals might have experienced the atrium and the rooms that open onto it. Unless focusing upon viewing processes, the term visitor is preferred here, as it allows for the integration of multiple interpretive modalities. Similarly, throughout this text, the focus upon embodied perception offers the potential to look beyond gender binaries, focusing instead upon perceptive capacities that might be shared across multiple potential divides, including that between the ancient visitior and his or her modern counterpart. |

| 2 | In addition to the oscilla listed above, two further oscilla are attributed the house, although they were found in upper layers of the insula, rather than within the structure itself. These include an oscilium of a Silenus mask, and one of a mask of a Satyr. See (Powers 2006, p. 230). |

| 3 | A second, smaller mirror is embedded in the plaster of the south-eastern portion of the peristyle space, alongside the lararium. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).