Reflecting on the Development of a Digital Platform for the Analysis of Fairs for Modern and Contemporary Art—Approach, Challenges, and Future Perspectives Using the Project ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE as an Example

Abstract

:1. Introduction: On the Potential and the Use of Digital Mapping in Art Market Studies

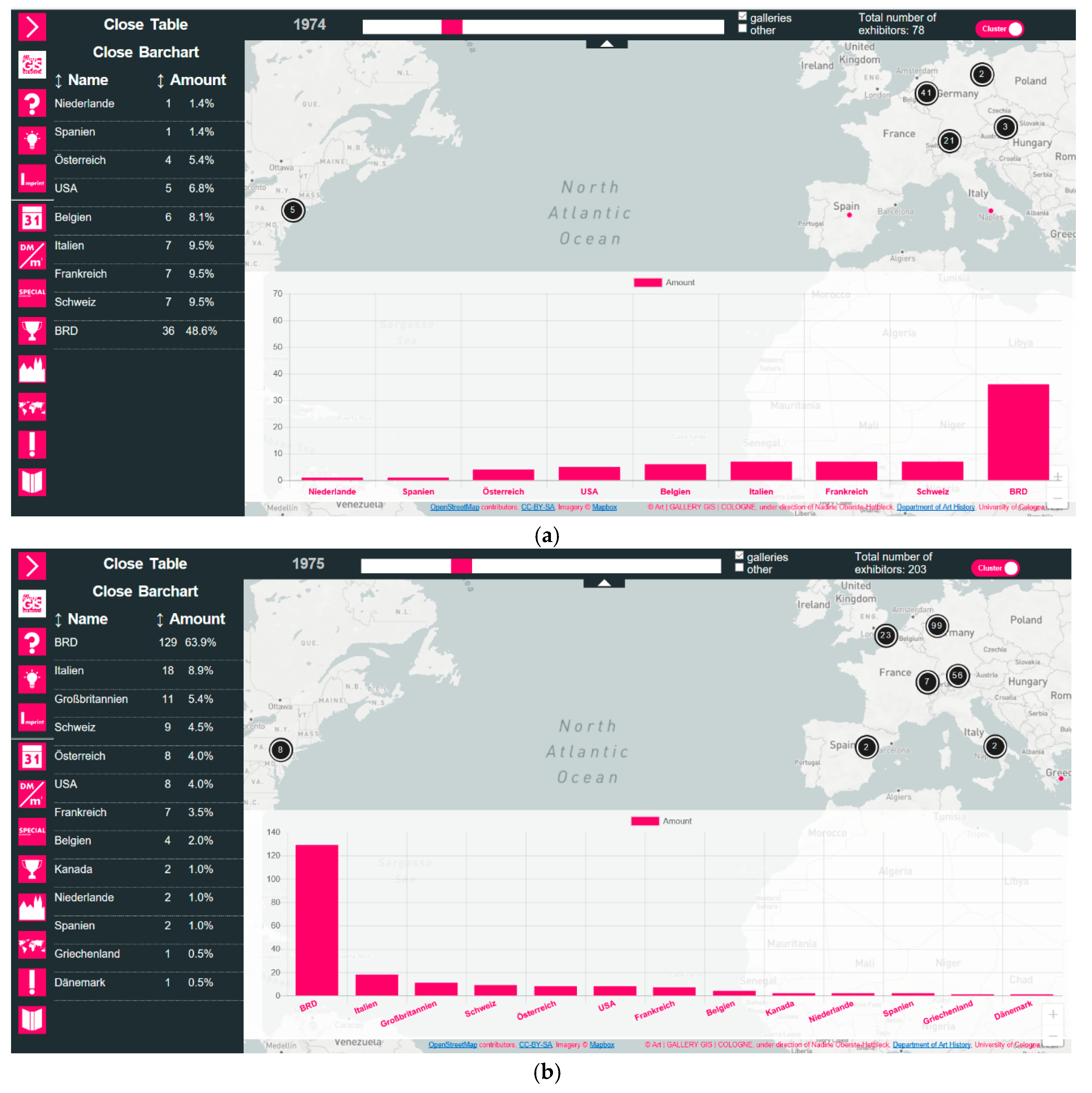

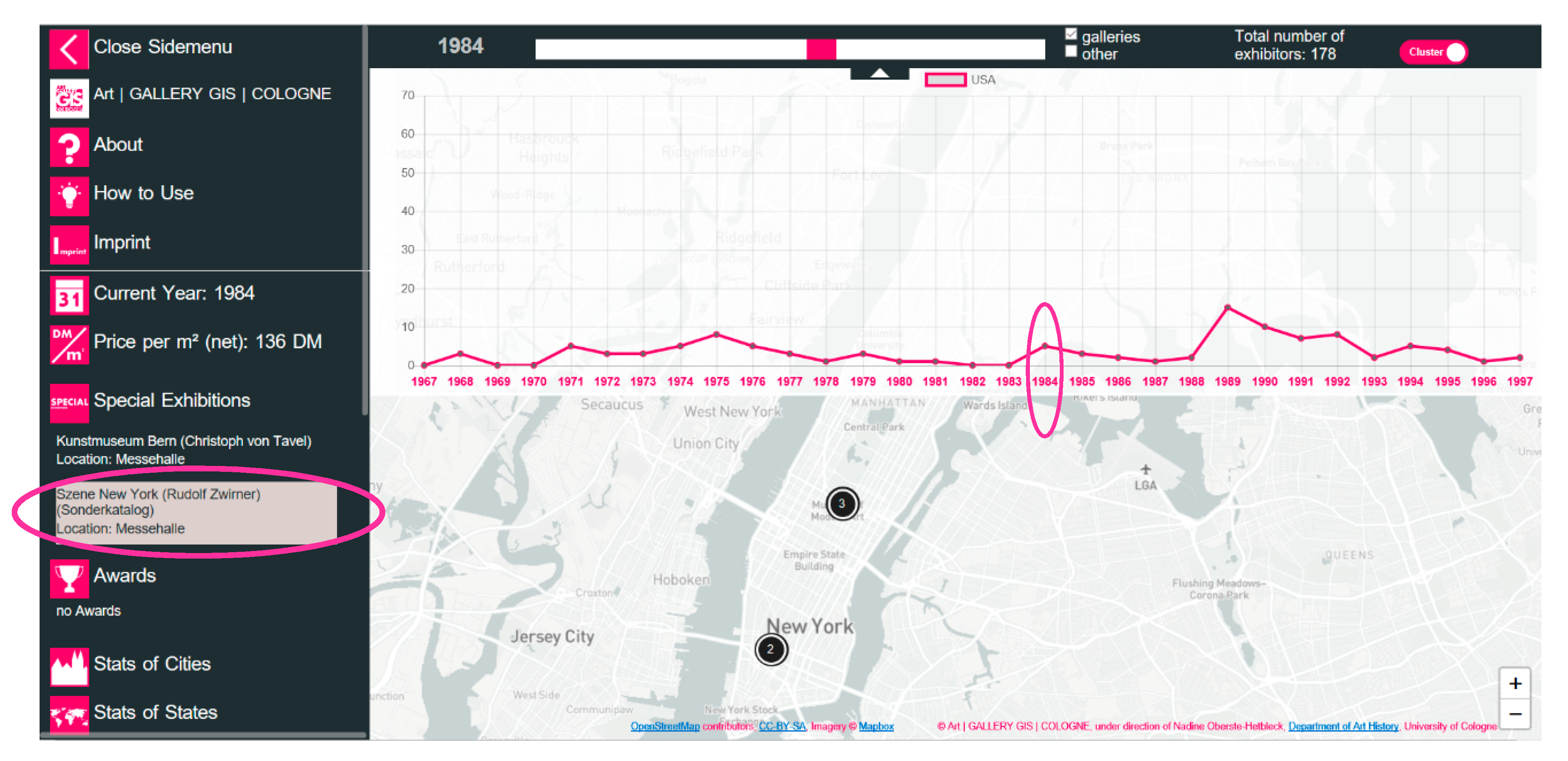

2. Introducing Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE and Its Research Status

3. ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE—Aims, Previous Stages of Development, and Status Quo

4. Challenges of Digital Mapping and the Importance of Providing Contextual Information to Support Adequate Analysis of Digital Maps in the Example of AGGC

- ⮚

- Economic and political events,

- ⮚

- Competitor fairs and mergers of art fairs,

- ⮚

- The organizers of the fair,

- ⮚

- Conditions of admittance,

- ⮚

- Admission committees (and other juries) and the selection criteria they employ,

- ⮚

- The respective location and spatial configuration of the fair,

- ⮚

- Special exhibitions at Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE (already included in AGGC)

- ⮚

- Awards and Awardees (already included in AGGC),

- ⮚

- Net square meter prices of the stands per year (already included in AGGC),

- ⮚

- Total turnover at the fair and the individual turnover of exhibitors,

- ⮚

- The exhibitors’ artistic program,

- ⮚

- Contemporary assessments of the significance of Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE.

- ⮚

- Subsidies made available by city of Cologne authorities,

- ⮚

- Displays on the stands,

- ⮚

- Number of visits,

- ⮚

- Number of fair catalogues printed.

5. From Where? Or: A Critical Consideration of the Source Materials

5.1. Fair Catalogues

5.2. Press Releases

5.3. Photographic Documentation

5.4. Minutes of the Board, Member, and General Meetings of the Associations and Admission Committees

5.5. The Art Fair’s General Conditions for Participation (GCP) and Special Conditions of Participation (SCP)

5.6. First-Hand Reports from Protagonists Involved in Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE26

6. The Parameters of Integrating Contextual Information

7. Conclusions and Future Developments

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayers, Edward L. 2010. Turning Toward Place, Space, and Time. In The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of the Humanities Scholarship. Edited by David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Baia Curioni, Stefano. 2012. A Fairy Tale: The Art System, Globalization, and the Fair Movement. In Contemporary Art and its Commercial Markets: A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios. Edited by Maria Lind and Olav Velthuis. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 115–51. [Google Scholar]

- Baia Curioni, Stefano, Laura Forti, and Ludovica Leone. 2015. Making Visible: Artists and Galleries in the Global Art System. In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art. Edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Curioni. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, Filippo. 2014. The Art Basel Effect. A Research on the Relation between Young Artists and Art Fairs. Master Arts, Culture & Society. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam, Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2105/17984 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Baus, Cathérine Dominique. 2008. Kunstmarkt 67: Von der Institution Kunst zur Organisation Kunstmesse. Ph.D. thesis, Cologne University, Cologne, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhamer, David J., John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris. 2015. Introduction. Deep Maps and the Spatial Humanities. In Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Edited by David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossin, Catherine. 2015. Towards a Spatial (Digital) Art History. ARTL@S BULLETIN 4: 4–6. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1070&context=artlas (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Dossin, Catherine, and Joyeux-Prunel Béatrice. 2015. The German Century? How a Geopolitical Approach Could Transform the History of Modernism. In Circulations in the Global History of Art. Edited by Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Catherine Dossin and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel. Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Johanna, Anne Helmreich, Matthew Lincoln, and Francesca Rose. 2015. Digital art history: The American scene. Perspective [En ligne] 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Pamela. 2015. Reflections on Digital Art History. CAA Reviews. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, Susan Elizabeth, and Joanna Gardner-Huggett. 2017. Spatial Art History in the Digital Realm. Historical Geography 45: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Genoni, Ilona. 2009. Just What Is It That Makes It So Different, So Appealing? Art Basel-Von der Verkaufsmesse zum Kulturereignis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, Jost. 2016. Archivrecht. Ein Leitfaden. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag für Standesamtwesen. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Günter. 2016. Kunstmarkt Köln 67, Gürzenich und Kölnischer Kunstverein, 13. bis 17. September 1967. In ART COLOGNE 1967–2016: Die Erste aller Kunstmessen/The First Art Fair. Edited by Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels e.V. ZADIK. Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice. 2013. Do Maps Lie? ARTL@S BULLETIN 2: 4–6. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas/vol2/iss2/1/ (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Kapferer, Judith. 2010. Twilight of the Enlightenment. The Art Fair, the Culture Industry, and the ‘Creative Class’. Social Analysis 54: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler-Lehmann, Margrit. 1993. Die Kunststadt Köln: Von der Raumwirksamkeit der Kunst in einer Stadt. Cologne: Selbstverlag im Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeographischen Institut der Universität zu Köln. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, Werner. 1996. Vom Kunstmarkt ’67 zur Art Cologne ´96. Pulheim: ART COLOGNE. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Soo Hee, and Jin Woo Lee. 2016. Art Fairs as a Medium for Branding Young and Emerging Artists: The Case of Frieze London. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 46: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, Jochen. 2000. Pop Art in Deutschland. Die Rezeption der amerikanischen und englischen Pop Art durch deutsche Museen, Galerie, Sammler und ausgewählte Zeitungen in der Zeit von 1959 bis 1972. Ph.D. dissertation, Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2018. The Art Market 2018. An Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel and Zurich: Art Basel & UBS. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2019. The Art Market 2019. An Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel and Zurich: Art Basel & UBS. [Google Scholar]

- Mehring, Christine. 2008. Emerging Market: The Birth of the Contemporary Art Fair. Artforum 46: 322–28, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Messe- und Ausstellungs-Ges.m.b.H., ed. 1989. ART COLOGNE. 23. Internationaler Kunstmarkt, 16.-22.11.1989. Cologne: Messe- und Ausstellungs-Ges.m.b.H. [Google Scholar]

- Morgner, Christian. 2014a. The Art Fair as Network. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 44: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgner, Christian. 2014b. The evolution of the art fair. Historical Social Research 39: 318–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberste-Hetbleck, Nadine. 2018a. Sonderprogramm Junge Galerien auf der Art Cologne. sediment. Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels 28/29: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oberste-Hetbleck, Nadine. 2018b. A Didactic Teaching and Learning Project in Art Market Research. Researching and Publishing the History of Commercial Art Dealing. Art History Pedagogy & Practice 3: 1–27. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ahpp/vol3/iss1/3 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Quemin, Alain. 2006. Globalization and mixing in the visual arts. An empirical survey of “high culture” and “globalization”. International Sociology 21: 522–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemin, Alain. 2013. International Contemporary Art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market. European Societies 15: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattemeyer, Volker. 1986. 20 Jahre Kunstmarkt. Cologne: Bundesverband Deutscher Galerien e.V. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, Corina. 2008. Art Basel—Entstehung und Erfolgsfaktoren einer Kunstmesse: Die Art Basel im Vergleich mit dem Kunstmarkt Köln. Master’s dissertation, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis, Franz. 2015. Economy of Symbolic Goods: Ethnographical Explorations at the Art Basel. Paper presented at a Workshop on “Documenta 2017”, Athenes, Greece, February 12; pp. 1–4. Available online: www.alexandria.unisg.ch/240447 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Spuhler, Gregor. 2010. Das Interview als Quelle historischer Erkenntnis. Methodische Bemerkungen zur Oral History. In Interviews: Oral history in Kunstwissenschaft und Kunst. Edited by Dora Imhof and Sibylle Omlin. Munich: Edition Metzel, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Velthuis, Olav. 2014. The Impact of Globalisation on the Contemporary Art Market. In Risk and Uncertainty in the Art World. Edited by Anna M. Dempster. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeylen, Filip. 2015. The India Art Fair and the Market for Visual Arts in the Global South. In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art. Edited by Olav Velthuis. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Hannah. 2018. Artists in Paris: Mapping the 18th-Century Art World. Journal18: A Journal of Eighteenth-Century Art and Culture 5: Coordinates: Digital Mapping and 18th-Century Visual, Material, and Built Cultures. Edited by Nancy Um and Carrie Anderson. Available online: www.journal18.org/issue5_williams (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Yogev, Tamar, and Thomas Grund. 2012. Network Dynamics and Market Structure: The Case of Art Fairs. Sociological Focus 45: 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, ed. 2003. Sediment—Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels 6. Cologne: Self-publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, ed. 2015. Sediment—Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels 25/26. Vienna: VfmK Verlag für moderne Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Zentralarchiv des Internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK, ed. 2016. ART COLOGNE 1967–2016: Die Erste aller Kunstmessen/The First Art Fair. Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For the linguistic distinction between gallery owner and art dealer in German, compare the explanations by Oberste-Hetbleck (2018b, p. 1). |

| 2 | E.g., Artl@s Exhibitions database (Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Catherine Dossin, and Léa Saint-Raymond, “Artl@s Exhibitions database, The Artl@s Project,” accessed 10 April 2019, http://artlas.ens.fr/en/database-2); London Gallery Project (Pamela Fletcher and David Israel, “London Gallery Project,” 2007, revised September 2012, accessed 10 April 2019, http://learn.bowdoin.edu/fletcher/london-gallery); Géographie du Marché de l’Art à Paris (Julien Cavero, Félicie Faizand de Maupeou, and Léa Saint-Raymond, “Géographie du Marché de l’Art à Paris. GeoMAP,” 2017, accessed 10 April 2019, https://paris-art-market.huma-num.fr); Artists in Paris (Hannah Williams and Chris Sparks, “Artists in Paris: Mapping the 18th-Century Art World,” accessed 10 April 2019, www.artistsinparis.org). |

| 3 | “A geographic information system (GIS) is a system designed to capture, store, manipulate, analyze, manage, and present all types of geographical data. The key word to this technology is Geography [emphasis added]—this means that some portion of the data is spatial. In other words, data that is in some way referenced to locations on the earth. Coupled with this data is usually tabular data known as attribute data. Attribute data can be generally defined as additional information about each of the spatial features.” (Definition of GIS following: Research Guides University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, “What is GIS? Information on Maps/Mapping & Geographic Information Systems (GIS),” accessed 10 April 2019, https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/GIS). |

| 4 | The acronym GIS should already make it clear that this is a point of entry to a project that functions primarily through geographical locations (of the exhibitors). |

| 5 | For more information about the symposium, see: Symposium | Mapping The Art Market, accessed 10 January 2019, https://amskoeln.hypotheses.org/1497. |

| 6 | The art fair best known under its current title ART COLOGNE has changed names several times over the course of its history: 1967–1969 Kunstmarkt Köln, 1970–1973 Kölner Kunstmarkt, 1974–1983 Internationaler Kunstmarkt Köln/Düsseldorf, and since 1984 ART COLOGNE. In the following, the term Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE is used throughout for reasons of representability and better legibility. The arrow serves to visualize the development of the art fair’s name from 1967 to today. |

| 7 | Genoni (2009) examines Art Basel in its development 1970–2008 and in this context also comparatively analyzes Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE into the 1970s (especially its first three years), because she understands Art Basel primarily as a response to this first fair for modern and contemporary art, positioning itself in the subsequent years in opposition to it (id., p. 7). |

| 8 | As a specialized archive for the art market, ZADIK—based in Cologne—comprises approximately 160 individual archives and has been an associated institution and research archive of the University of Cologne since 2015. It is a very close collaborative partner in the Art Market Master module at the Department of Art History in Cologne. |

| 9 | According to Morgner (2014a, p. 34), fairs for modern and contemporary art developed in especially those locations lacking the density of galleries that were to be found in such art metropolises as New York and Paris, but which were geographically located close to such centers; id. 2014b. |

| 10 | In those cases where a tabular listing was not available, the individual entries for exhibitors were reviewed and evaluated. Where discrepancies arose between the address in the list of exhibitors and the one noted on the gallery’s catalogue page, the address from the list of exhibitors was preferred. |

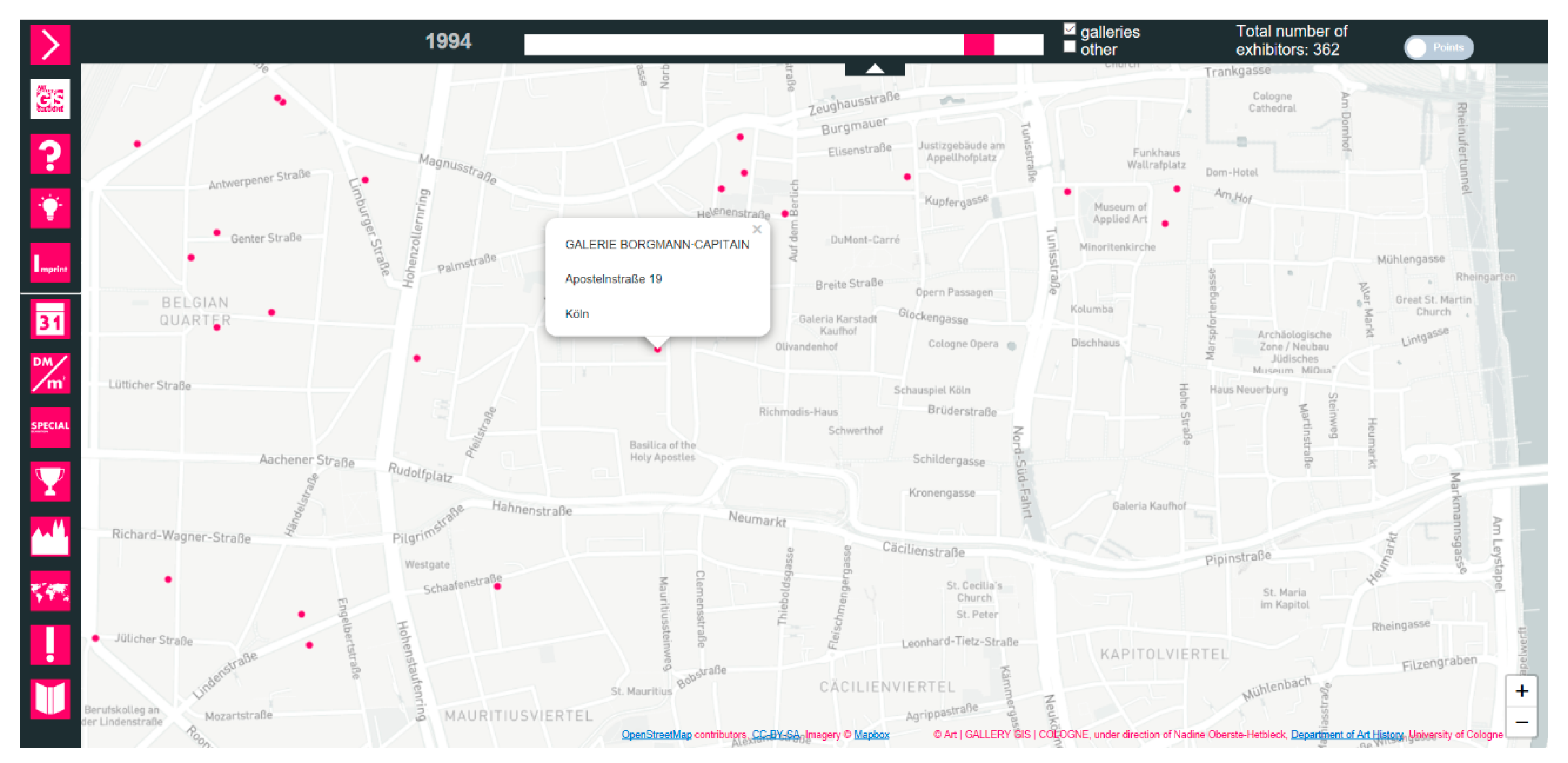

| 11 | These entries are, however, not identical to the total number of exhibitors, since various exhibitors have participated in the fair several times. The addresses for some exhibitors had to be further researched, the reasons for which were various: 1. Missing addresses of the participating exhibitors in Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE catalogues/in some cases only the PO box was noted. 2. Historical addresses that no longer exist as such/for several other addresses no clear coordinates could be determined. 3. In some cases, several locations for one and the same exhibitor were noted in the catalogue. The missing historical addresses were identified during intensive research using source materials (e.g., contemporary correspondence, gallery publications), works of reference (e.g., the International Art Directory, specialist publications), by computer, and through contact with those who owned a respective business at the time. To date, 16 addresses remain absent, that could not be discovered. Missing and hitherto unidentifiable historical addresses are listed in the left navigation bar of AGGC under Annotations for each year. There are no points for these on the map; they have, however, been taken into account statistically. |

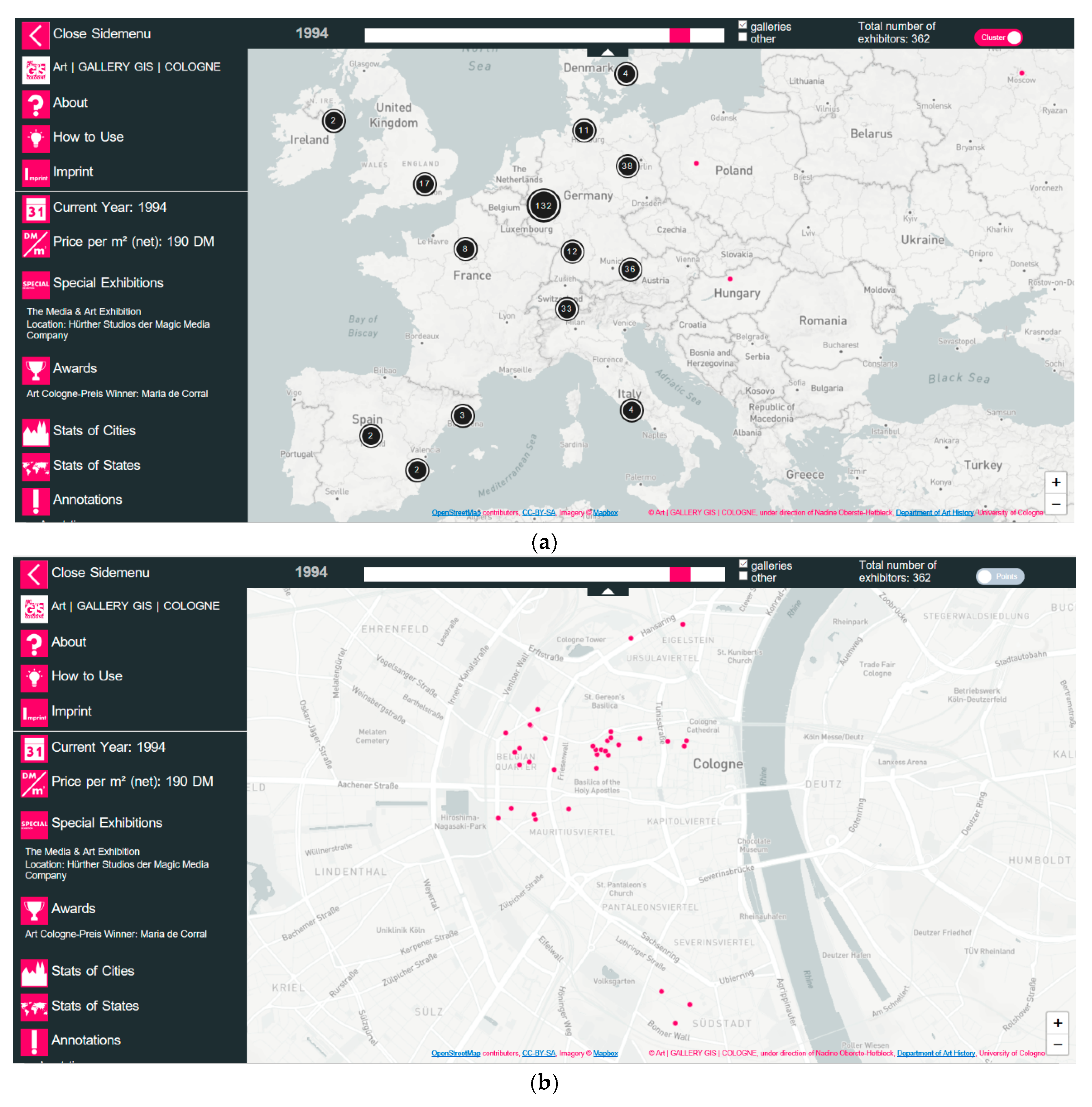

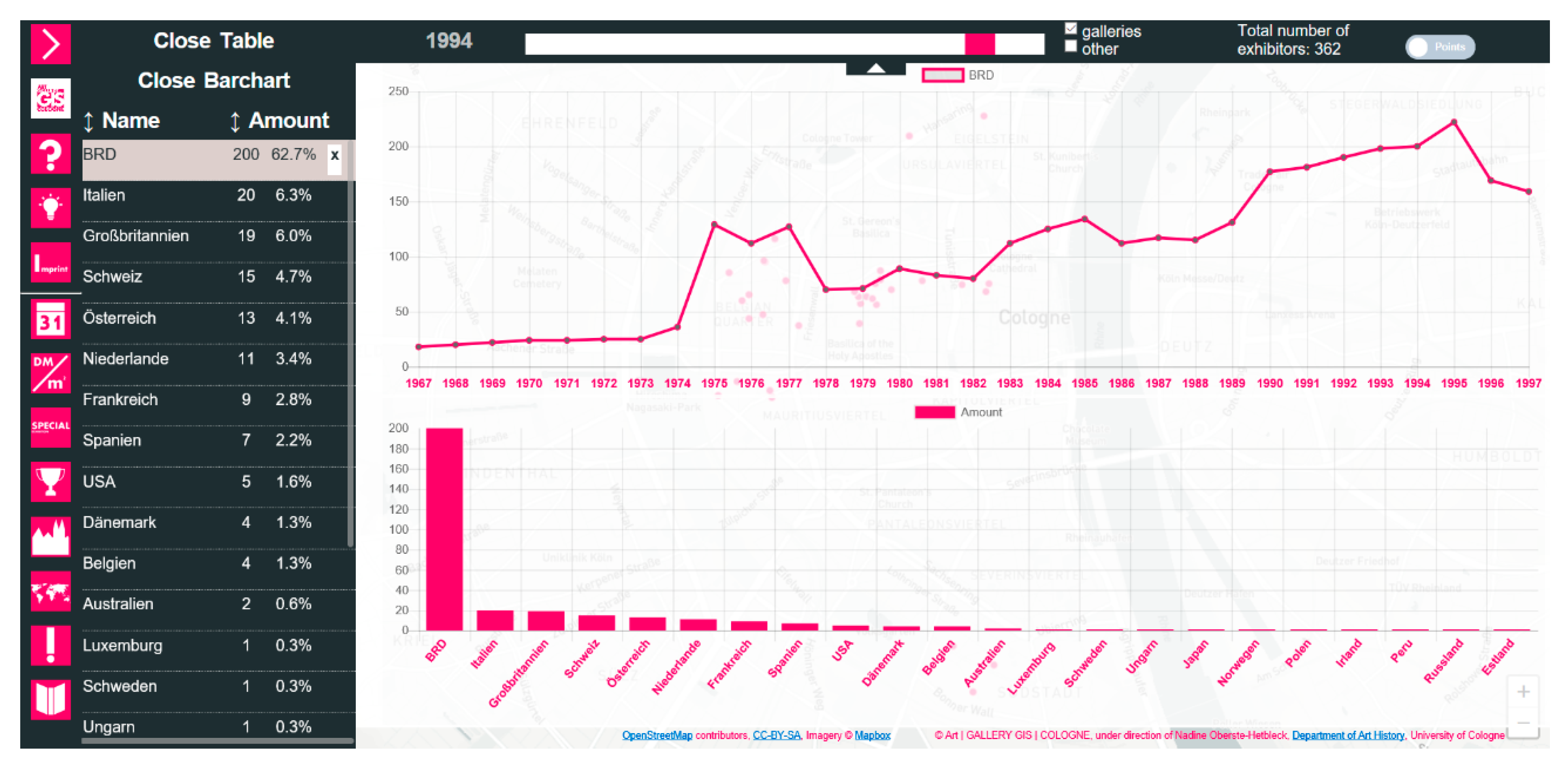

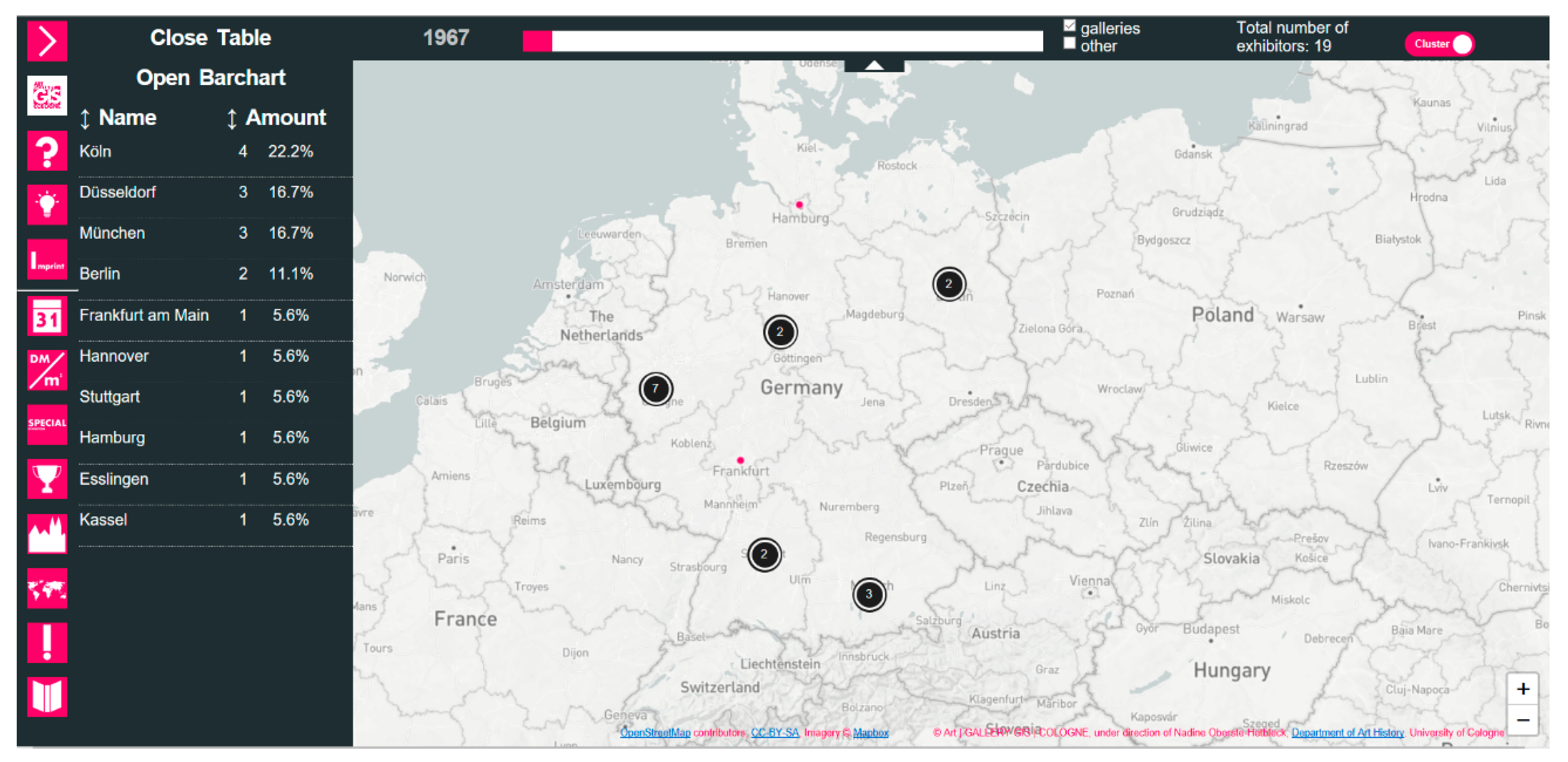

| 12 | In the latter display mode, the locations are bundled in accordance with the zoom factor, thus enabling more meaningful visualizations on the world map view. |

| 13 | The minutes of the admissions meeting for the 1994 edition of Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE note the cumulative admission as a result of the merger. Cf. minutes [Irene Saxinger] of the admissions meeting for ART COLOGNE 1994 on 25 and 26 April 1994, Cologne, 28 April 1994, ZADIK, no signature. |

| 14 | In the period 1975–1983, the location of the fair alternated annually between the trade fair exhibition spaces in Düsseldorf and Cologne. |

| 15 | Ultimately, researchers who create and provide digital maps cannot be held responsible for misinterpretations by third parties, and such a warning in AGGC would make users accordingly aware. |

| 16 | In reviewing the research literature, certain contextual information has been considered by general consensus to be relevant and compiled. These include the venue, the number of exhibitors, and the number of visitors. Rombach (2008) collates the following contextual information in tabular form: Table 2: year, number of exhibitors in total, as well as national and international exhibitors, location, dates, number of visitors, entrance fees, and sales in deutschmarks; Table 12: artists represented at Kunstmarkt (categorized by specific styles); Tables 3–10: the most frequently represented artists; Table 11: galleries represented. ZADIK (Zentralarchiv des internationalen Kunsthandels ZADIK 2016) in its yearly reviews systematically surveys the number of exhibitors, the number of visitors, the venue, and the accompanying program. In addition, extensive relevant contextual information is also included. |

| 17 | In 2013, RBA received more than four million analogue photographs from Koelnmesse. See the press release from Koelnmesse. 2013. Neue Bleibe für historische Koelnmesse-Fotos, no. 11/Cologne, from May 2013, accessed 29 December 2018, www.koelnmesse.de/Koelnmesse/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/index.php?aktion=pfach&p1id=kmpresse_kmu&format=html&base=&tp=k3content&search=&pmid=kmeigen.km_pr08_1369306979&start=0&anzahl=10&channel=kmeigen&language=d&archiv=. |

| 18 | For this, see the holdings C1 Bundesverband Deutscher Galerien [und Kunsthändler] BVDG, Cologne, and C2 Kunstmessen Köln u. Düsseldorf (submitted by BVDG). In addition, the archives of those galleries and art dealers who participated in Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE or were even members of one of the fair’s organizing bodies also contain relevant documents on Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE. |

| 19 | These concern the number of individual visitors to the fair, which means that statistically multiple visits should not be taken into account. |

| 20 | Cf. Rombach (2008, p. 7), who states with regard to Art Basel that no reliable data is available concerning the turnover at the fair. |

| 21 | See for example the holdings of Wolf P. Prange, Berlin (ZADIK, H6), Johanna Schmitz-Fabri (ZADIK, H1), Anita Kloten, and Peter Fischer (Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln/HAStK, inventory no. 1401). Angelika Platen, in particular, also took photographs at Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE. |

| 22 | Since, according to current information, the stands’ identification is rarely photographed, the exhibitors’ stands can only be assigned to the photographs on the basis of the works of art in each stand, handwritten notes by the photographers, and the clues displayed on such identifiers as information signs that can be discerned in photographs of the fair’s aisles. This requires use of the researcher’s knowledge of Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE, the art market, and art history. |

| 23 | As a collaborative partner, the RBA is currently digitizing just one initial year, namely 1974. With the involvement of students at the Department of Art History at the University of Cologne, during a seminar by Johanna Gummlich and Nadine Oberste-Hetbleck in the 2019 summer semester, the digitized photographs in the Art Publishing System (APS) database of RBA are being formally inventoried and indexed, and in addition some are being more deeply examined for the research project. It is a trial run focusing on one year, to assess the effort that will be required in the subsequent years. |

| 24 | For more information see Oberste-Hetbleck (2018a, pp. 9f). |

| 25 | They were taken from the SCP for AGGC. |

| 26 | Especially gallery owners who participated in the art fair, members of the admissions committee or the Exhibition Jury, Koelnmesse employees, rejected applicants, and contemporary observers. |

| 27 | At this point, the media-informatic aspect of AGGC should be briefly mentioned: The locations of the participating galleries during the first three decades were georeferenced (GeoJSON) and visualized in an online map (Leaflet.js). Through a reactive environment (Vue.js), the online map is embedded with further information. |

| 28 | Making the data relating to the relevant persons anonymous would be one solution, which would at least make statistical evaluations feasible. |

| 29 | Quemin (2013), 166 assesses the composition of exhibitors with regard to countries of origin, in the context of an analysis of Art Basel 2008, stating: “The national diversity of exhibiting galleries is generally a good indication of the quality of an art fair, which should ideally resist the frequent pressure to favour domestic galleries and limit the number of places available to national exhibitors (unless it is organised by a leading art-market country with highly reputable galleries).” He also, with reference to his statements in Quemin (2006), includes Germany amongst the latter, so that a strong presence of German galleries at Kunstmarkt Köln->ART COLOGNE is not essentially surprising. |

| 30 | For this purpose, a data set was created from the business telephone directory. This included all entries found under the categories of art dealers, paintings, galleries, even though not every category was to be found in every edition of the business telephone directory. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oberste-Hetbleck, N. Reflecting on the Development of a Digital Platform for the Analysis of Fairs for Modern and Contemporary Art—Approach, Challenges, and Future Perspectives Using the Project ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE as an Example. Arts 2019, 8, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030088

Oberste-Hetbleck N. Reflecting on the Development of a Digital Platform for the Analysis of Fairs for Modern and Contemporary Art—Approach, Challenges, and Future Perspectives Using the Project ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE as an Example. Arts. 2019; 8(3):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030088

Chicago/Turabian StyleOberste-Hetbleck, Nadine. 2019. "Reflecting on the Development of a Digital Platform for the Analysis of Fairs for Modern and Contemporary Art—Approach, Challenges, and Future Perspectives Using the Project ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE as an Example" Arts 8, no. 3: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030088

APA StyleOberste-Hetbleck, N. (2019). Reflecting on the Development of a Digital Platform for the Analysis of Fairs for Modern and Contemporary Art—Approach, Challenges, and Future Perspectives Using the Project ART|GALLERY GIS|COLOGNE as an Example. Arts, 8(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030088