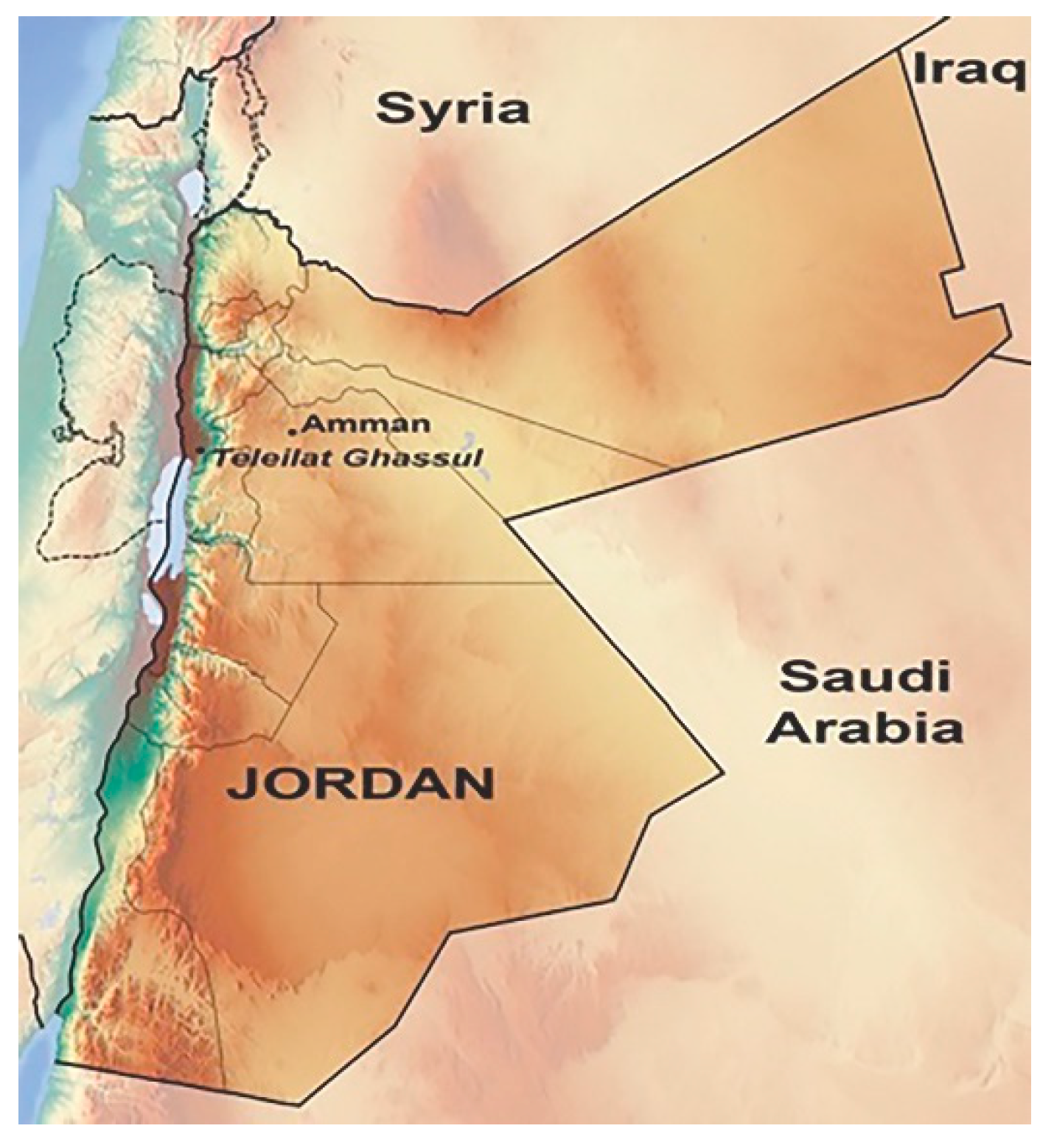

Early Visual Communication: Introducing the 6000-Year-Old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Frescoes of Teleilat Ghassul

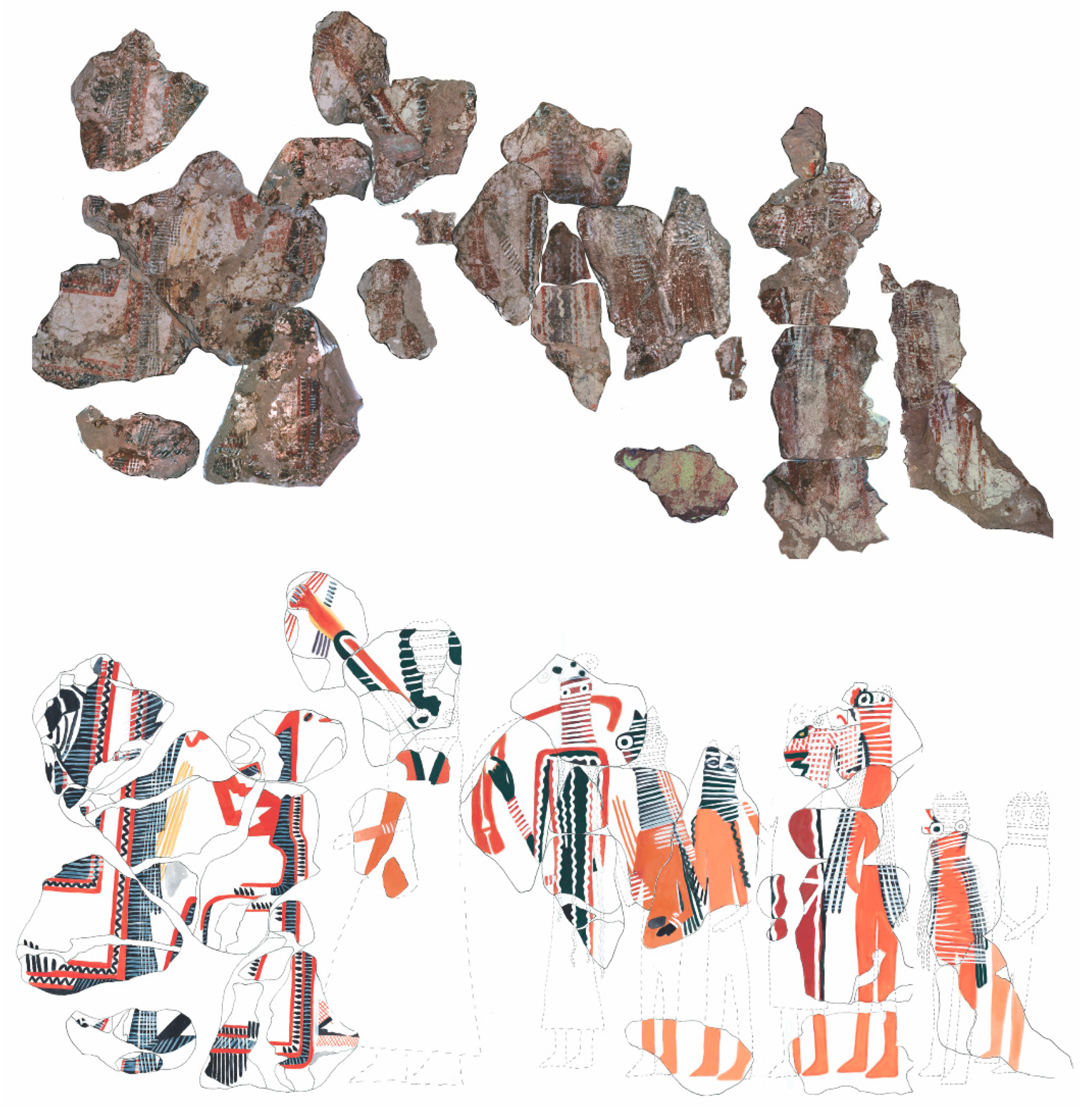

2.1. The Notables/Personnages Freize (Middle Chalcolithic ca. 4200 BC) PBI Stratum III

2.2. The Star of Ghassul (Late Chalcolithic ca. 4000–3900 BC) PBI Stratum IVB

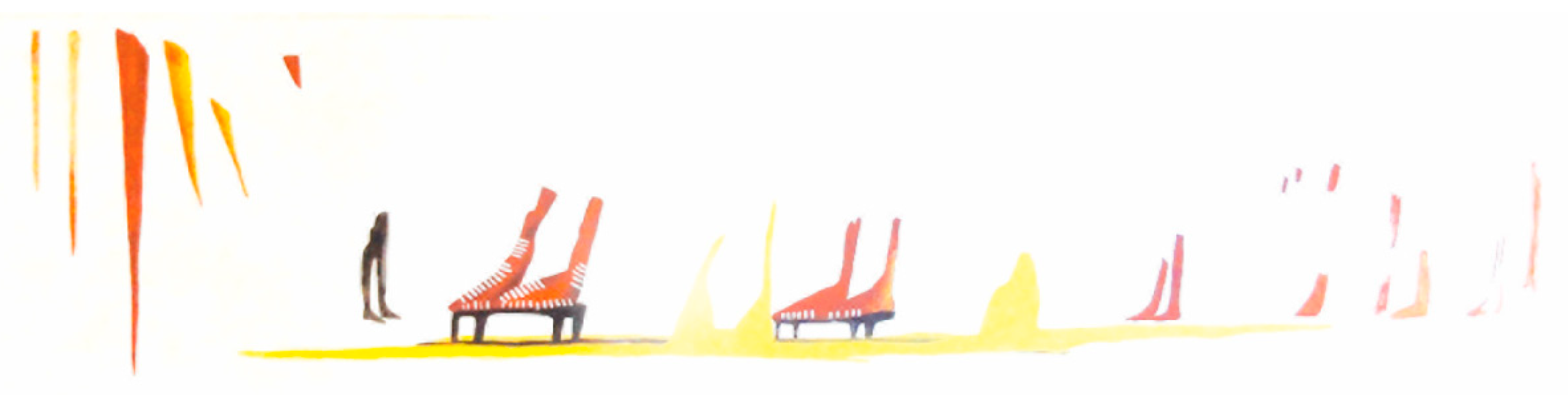

2.3. Hennessy’s Processional Fresco (Middle Chalcolithic ca. 4200 BC) PBI stratum III—Hennessy’s Phase E

2.4. The ‘Tiger/Landscape’ Fresco (Early Chalcolithic ca. 4700 BC) PBI Stratum II

3. Discussion

3.1. Technical Evaluation

3.2. Art-Historical Importance

3.3. Archaeological and Anthropological Importance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aruz, Joan, ed. 2003. Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Asher-Greve, Julia. 1997. The Essential Body: Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Gendered Body. Gender & History 9: 432–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Adon, Pessah. 1980. The Cave of the Treasure—The Finds from the Caves in Nahal Mishmar. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Stephen. 2008. The Chalcolithic Period. In Jordan—An Archaeological Reader. Edited by R. Adams. London: Equinox Publishing, pp. 109–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Stephen, Ugo Zoppi, John Meadows, Quan Hua, and Samantha Gibbins. 2004. The End of the Chalcolithic Period in the South Jordan Valley: New C14 Determinations from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. Radiocarbon 46: 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, Ann. 2008. The Power of Technology in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean—The Case of Painted Plaster. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Dorothy. 1981. The Ghassulian Wall Paintings. London: Kenyon-Deane. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Mark, Richard Jones, and Sophocles Philippakis. 1977. Scientific Analyses of Minoan Fresco Samples from Knossos. The Annual of the British School at Athens 72: 121–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, Nicholas. 2008. The Dawn of Astrology: A Cultural History of Western Astrology. London: Continuum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Case, Humphrey, and Joan Crowfoot Payne. 1962. Tomb 100: The Decorated Tomb at Hierakonpolis. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 48: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, Anne. 2010. Frescoes. In The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Edited by Eric Cline. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 223–36. [Google Scholar]

- Corteggiania, Jean-Pierre. 1987. The Egypt of the Pharaohs at the Cairo Museum. London: Scala. [Google Scholar]

- De Miroschedji, Pierre. 2011. At the Origins of Canaanite Cult and Religion: The Early Bronze Age Fertility Ritual in Palestine. Eretz-Israel 30: 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Drabsch, Bernadette. 2015. The Mysterious Wall Paintings of Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. In Context. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Drabsch, Bernadette, and Stephen Bourke. 2014. Ritual, art and society in the Levantine Chalcolithic: The ‘Processional’ wall painting from Teleilat Ghassul. Antiquity 88: 1081–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabsch, Bernadette. Forthcoming. Nude, Robed and Masked Processions: Considering the Figural Images in the Teleilat Ghassul Wall Paintings, Jordan. In Iconography and Symbolic Meaning of the Human in the Near East. Edited by Bernd Muller-Neuhof and Claudia Beuger. Vienna: OREA.

- During, Bleda. 2005. Building Continuity in the Central Anatolian Neolithic: Exploring the Meaning of Buildings at Asikli Hoyuk and Catalhoyuk. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 18: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During, Bleda, and Arkadiusz Marciniak. 2005. Households and Communities in the Cnetral Anatolian Neolithic. Archaeological Dialogues 12: 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Iener. 1987. The Pyramids of Egypt. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Carolyn. 1977. The Religious Beliefs of the Ghassulians. Palestine Exploration Fund 109: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Claire. 1985. Laden Animal Figurines from the Chalcolithic Period in Palestine. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 258: 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Arthur. 1921–1935. The Palace of Minos. 4 vols. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, Kent, and Joyce Marcus. 2012. The Creation of Inequality. How our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery and Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef. 1998. Dancing and the Beginning of Art Scenes in the Near East and South-East Europe. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8: 207–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, John Basil. 1969. Preliminary Report on a First Season of Excavations at Teleilat Ghassul. Levant 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian. 2006. Catalhoyuk—The Leopard’s Tale, Revealing the Mysteries of Turkey’s Ancient ‘Town’. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2007. Catalhoyuk in the Context of the Middle Eastern Neolithic. Annual Review of Anthropology 36: 105–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Sinclair. 1978. The Arts of Prehistoric Greece. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, David, and Yorke Rowan. 2011. Deconstructing and Recomposing the Narrative of Spiritual Life in the Chalcolithic of the Southern (4500–3700 BC). In Beyond Belief: The Archaeology of Religion and Ritual. Edited by Yorke Rowan. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Richard, and Effie Photos-Jones. 2005. Technical Studies of Aegean Bronze Age wall painting: Methods, results and future prospects. In Aegean Wall Painting: A Tribute to Mark Cameron. Edited by Louise Morgan. London: British School at Athens Studies, vol. 13, pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Barry J. 1973. Photographs of the decorated tomb at Hierakonpolis. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59: 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Barry J. 1989. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Koeppel, Robert, Jacques Senes, John Murphy, and Gerald Mahan. 1940. Teleilat Ghassul. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, John Robert. 1973. Chalcolithic Ghassul: New Aspects and Master Typology. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Thomas Evan. 1986. Archaeological Sources for the Study of Palestine: The Chalcolithic Period. The Biblical Archaeologist 49: 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, Jaimie. 2010. Community is Cult, Cult is Community: Weaving the Web of Meanings for the Chalcolithic. Paleorient 36: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, Alexis, Robert Koeppel, and Rene Neuville. 1934. Teleilat Ghassul. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 2000. A Sacred Tree in the Chalcolithic Shrine at En Gedi: A Suggestion. Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Society 18: 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mellaart, James. 1967. Catal Huyuk—A Neolithic town in Anatolia. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Midant-Reynes, Beatrix. 2008. The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Pharaohs. Oxford: Blackwells. [Google Scholar]

- North, Robert. 1960. A Unique new Palestine Art-Form. Miscelanea Biblica—Andres Fernandez 34: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- North, Robert. 1961. Ghassul 1960 Excavation Report. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ochshorn, Judith. 1996. Sumer—Gender Role Reversals. In Gender Reversals and Gender Cultures—Anthropological and Historical Perspectives. Edited by Sabrina Ramet. London: Routledge, pp. 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, Michel. 2001. Blue—The History of a Color. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Yitzhak, Ianir Milevski, and Nimrod Getzov. 2013. ‘Sound-track of the sacred marriage? A newly discovered cultic scene on an EB seal impression’. Ugarit-Forschungen 44: 243–60. [Google Scholar]

- Porath, Yehoshua. 1992. Domestic architecture of the Chalcolithic Period. In The Architecture of Ancient Israel, from Prehistoric to the Persian Period. Edited by Aharon Kampinski and Ronny Reich. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 14–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, Yorke. 2014. The Southern Levant (Cisjordan) during the Chalcolithic Period. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant c.8000-332 BCE. Oxford: Oxfors University Press, pp. 223–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, Yorke M., and Jonathan Golden. 2019. The Chalcolithic Period of the Southern Levant: A Synthetic Review. Journal of World Prehistory 22: 1–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, Yorke, and David Ilan. 2007. The Meaning of Ritual Diversity in the Chalcolithic of the Southern Levant. In Cult in Context: Reconsidering Ritual in Archaeology. Edited by David Barrowclough and Christopher Malone. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 249–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. 2007. When Writing met Art—From Symbol to Story. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzbaum, Paul, Constance Silver, and Christopher Wheatley. 1980. Consolidation and Mounting of Chalcolithic Mural Painting Fragments from the Site of Teleilat Ghassul. Rome: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, Peta. 2008. The Chalcolithic Cult and Risk Management at Teleilat Ghassul—The Are E Sanctuary. Series 1864; Oxford: Archaeopress BAR International. [Google Scholar]

- Stager, Lawrence. 1992. The Periodization of Palestine from Neolithic through Early Bronze Age Times. In Chronologies in Old World Archaeology. Edited by Robert Ehrich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 1, pp. 22–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tefnin, Roland. 1979. Image et histoire. Réflexions sur l’usage documentaire de l’image égyptienne. Chronique d’Égypte 54: 218–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavapalan, Shiyanthi. 2018. Radiant Things for Gods and Men: Lightness and Darkness in Mesopotamian Language and Thought. Colour Turn VI: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ussishkin, David. 1971. The ‘Ghassulian’ Temple in Ein Gedi and the Origin of the Hoard from Mishmar. The Biblical Archaeologist 34: 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussishkin, David. 2014. The Chalcolithic Temple in En Gedi: Fifty Years after its Discovery. Near Eastern Archaeology 77: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, David. 2007. Basic Colour Term Evolution in Light of Ancient Evidence from the Near East. In Anthropology of Color: Interdisciplinary Multilevel Modeling. Edited by Robert E. MacLaury, Galina V. Paramei and Don Dedrick. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 229–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, Timothy. 1993. Frameworks for an Archaeology of the Body. In Interpretive Archaeology. Edited by Christopher Tilley. Oxford. pp. 31–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Burcu, Laurel Hackley, and Sharon Steadman. 2018. Sanctifying the House: Child Burial in prehistoric Anatolia. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 164–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoffee, Norman. 2005. Myths of the Archaic State. Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drabsch, B.; Bourke, S. Early Visual Communication: Introducing the 6000-Year-Old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. Arts 2019, 8, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030079

Drabsch B, Bourke S. Early Visual Communication: Introducing the 6000-Year-Old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. Arts. 2019; 8(3):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030079

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrabsch, Bernadette, and Stephen Bourke. 2019. "Early Visual Communication: Introducing the 6000-Year-Old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan" Arts 8, no. 3: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030079

APA StyleDrabsch, B., & Bourke, S. (2019). Early Visual Communication: Introducing the 6000-Year-Old Buon Frescoes from Teleilat Ghassul, Jordan. Arts, 8(3), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030079