Curating on the Web: The Evolution of Platforms as Spaces for Producing and Disseminating Web-Based Art

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Rationale for This Study and Method of Research

2. The Domain and Characteristics of Curating on the Web

3. The Genealogy of Curating on the Web and Its Technological Context

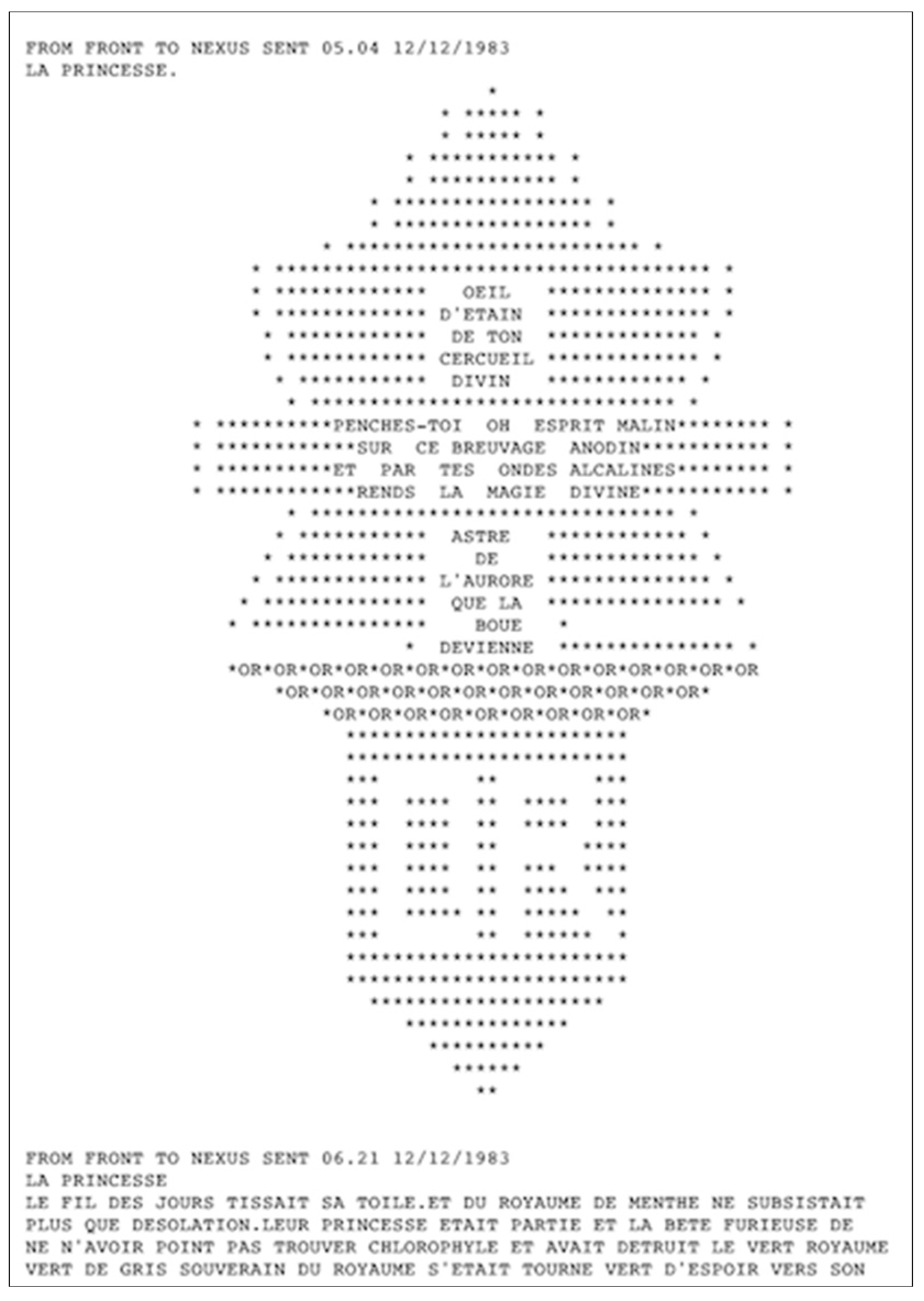

3.1. The Internet: Experiments with the Network as a Preamble to the World Wide Web

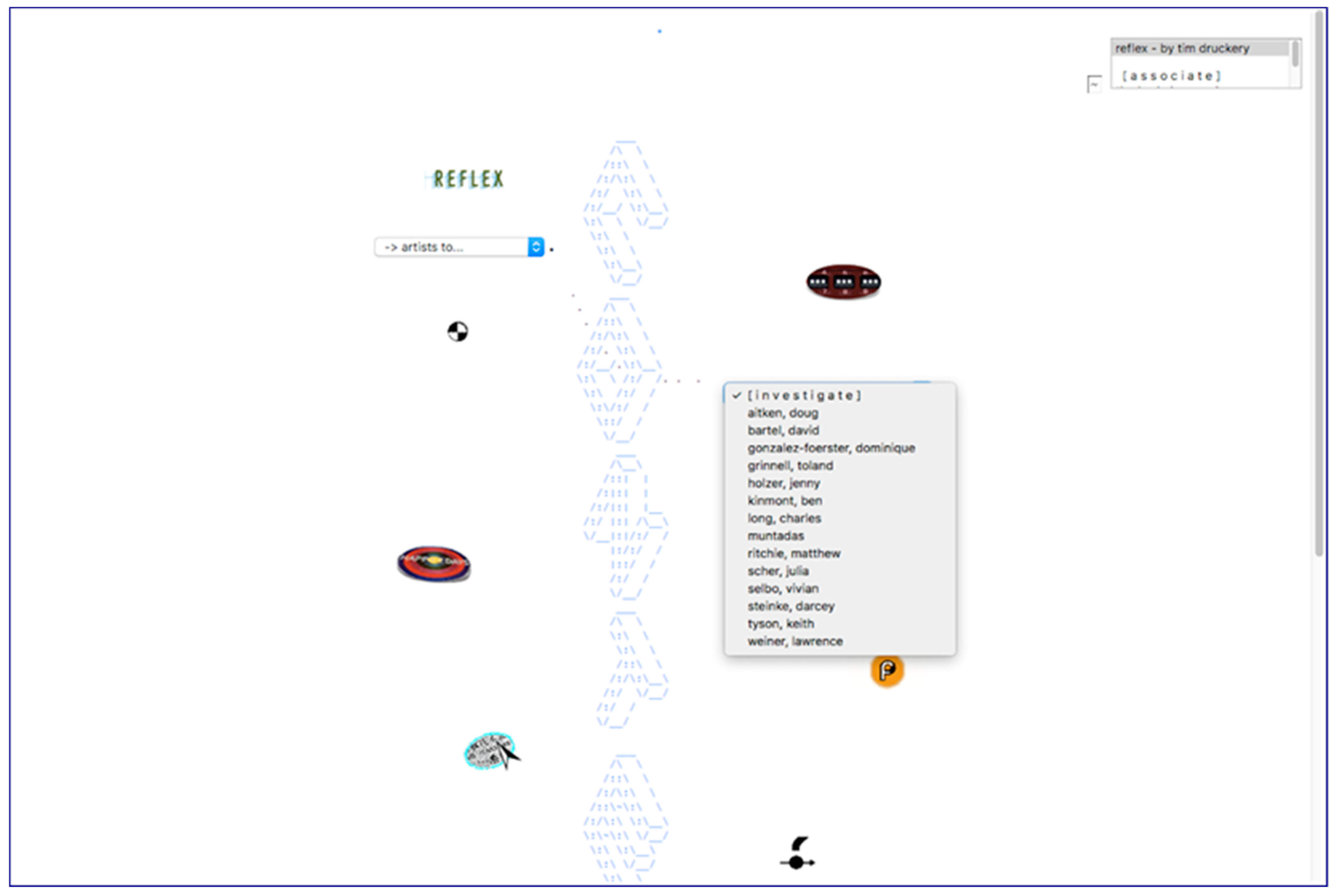

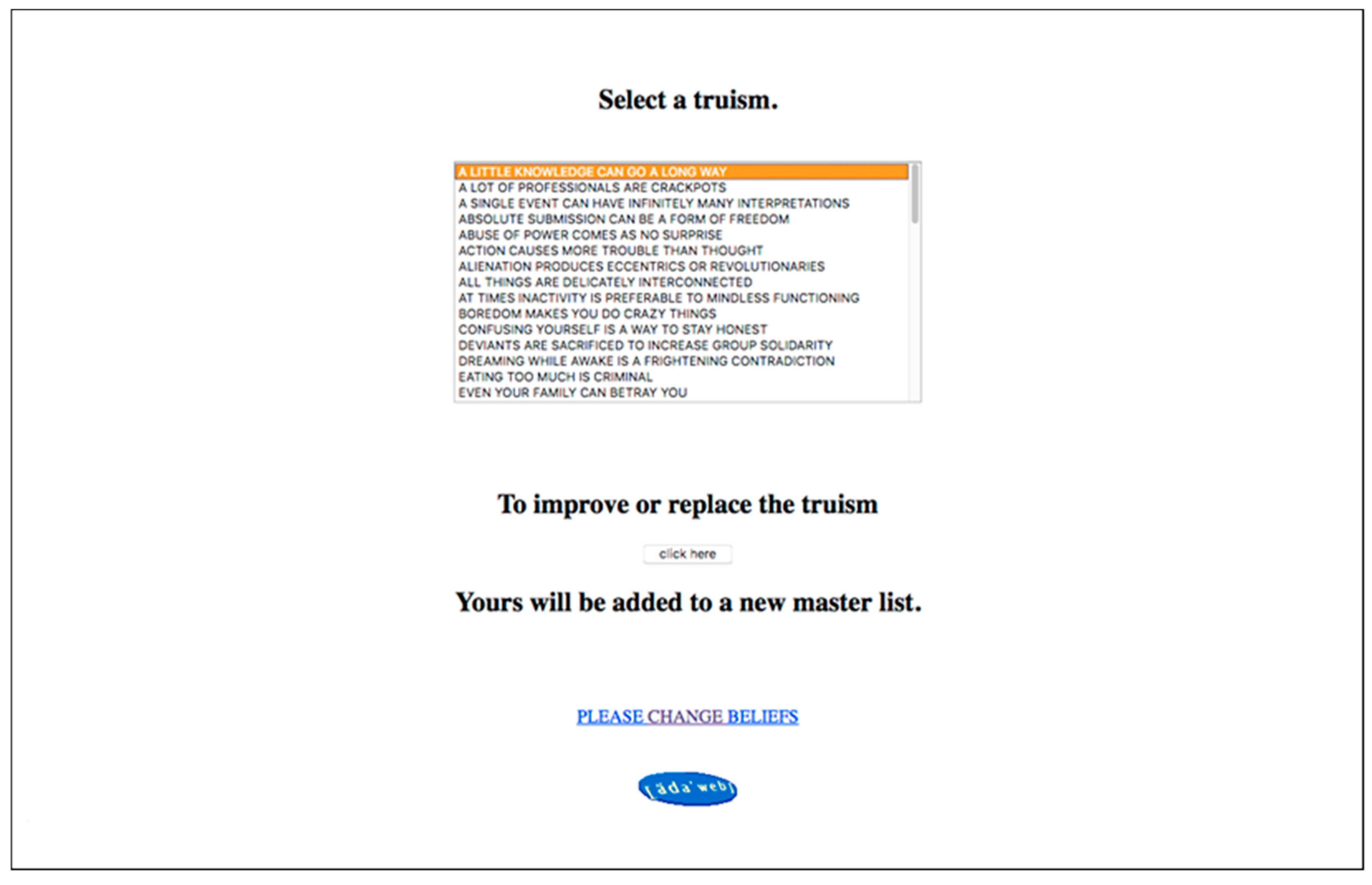

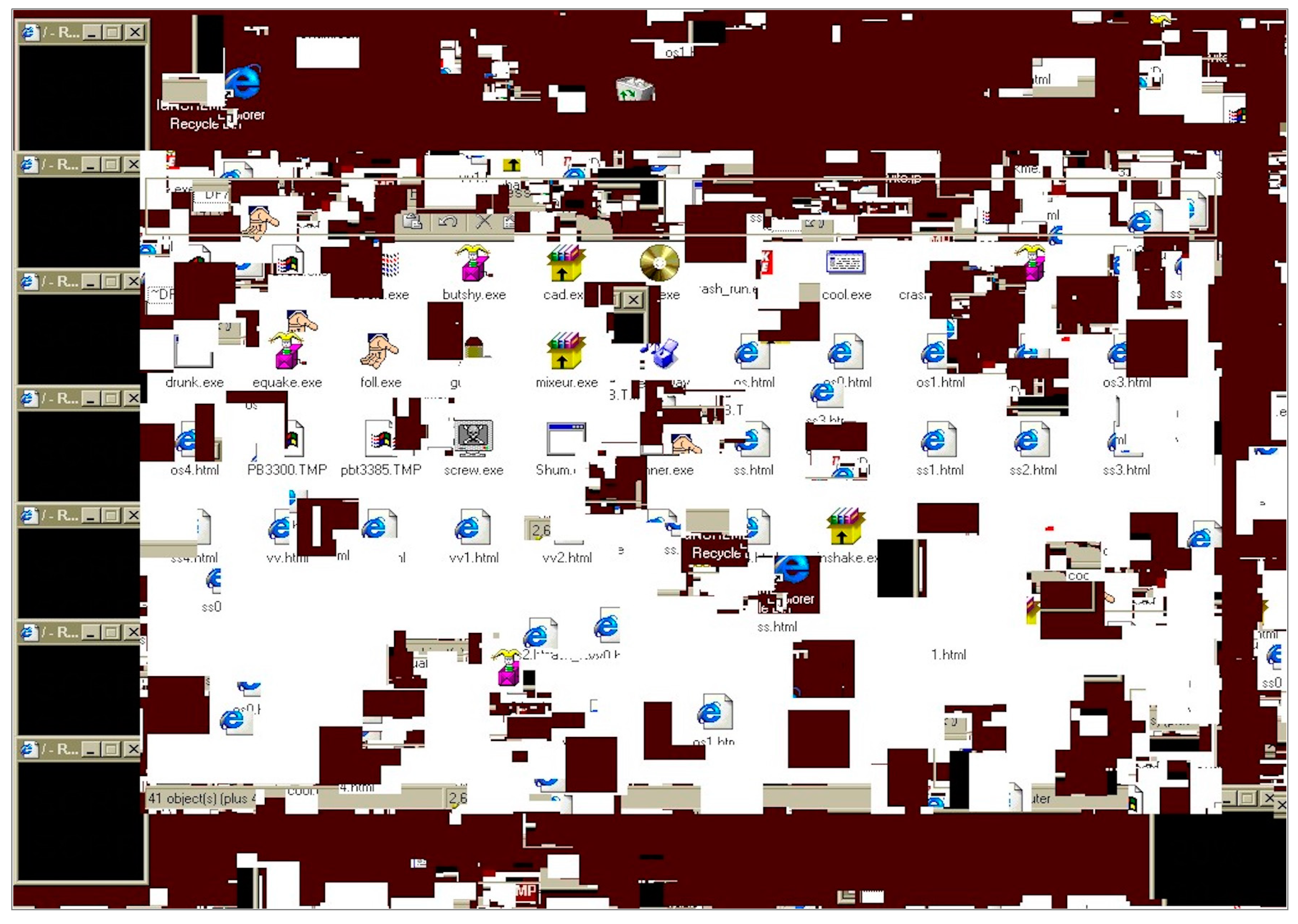

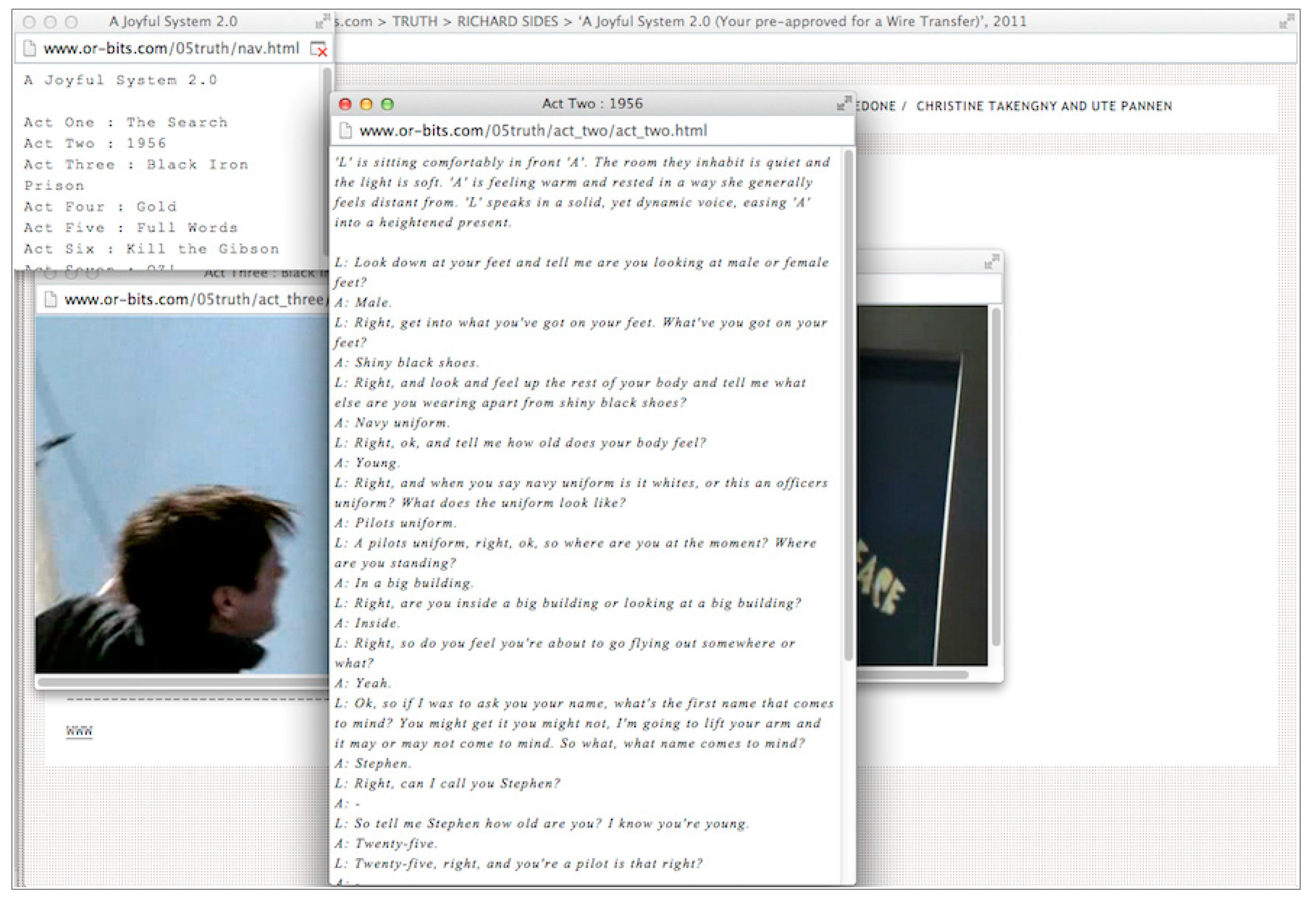

3.2. The Nineties Counterculture: Experiments with the Web Browser

3.3. The Web 2.0: Experiments with the Proprietary and Scripted Web of Platforms

3.3.1. Curating through Publishing Platforms: From the Blog to Visual Displays

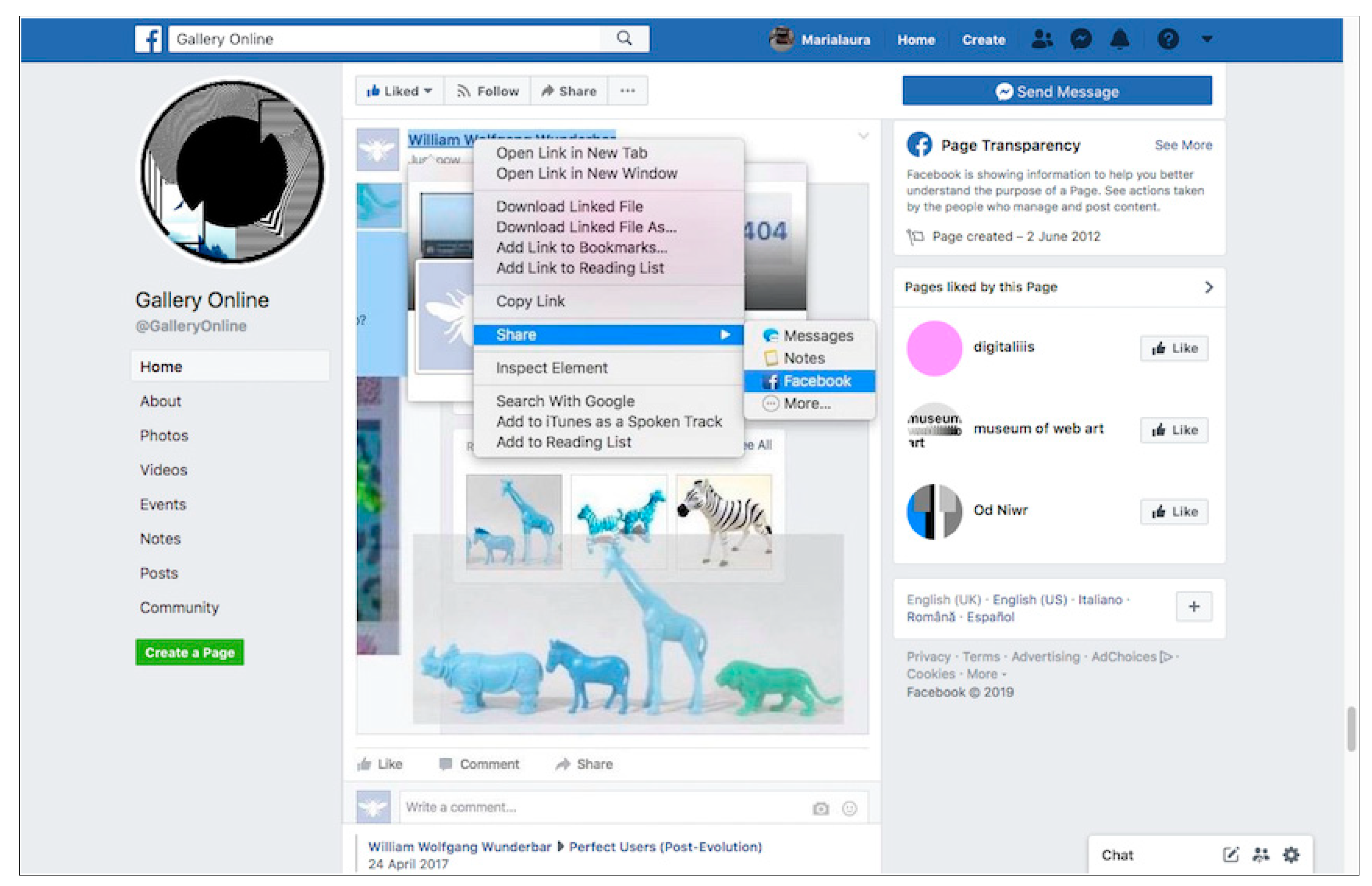

3.3.2. Curating through Social Platforms: From Entertainment Services to Social Media

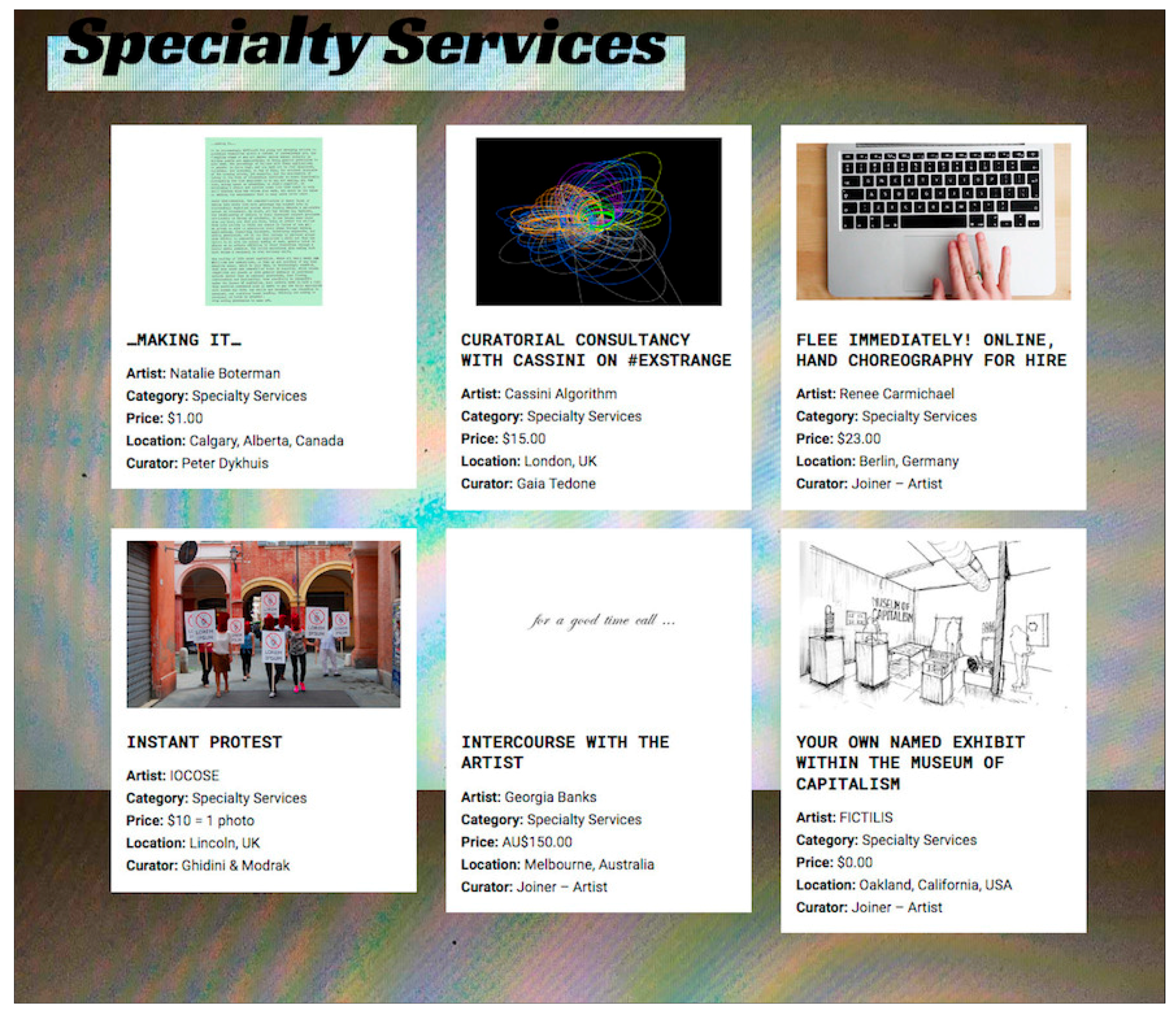

3.3.3. Curating through Bespoke Platforms: From the Themed Group Exhibitions to Online–Offline Displays

3.4. Today’s Web: Experiments with the Commercial Network of Networks

4. Conclusion: An Assessment of the Relevance of This Historical Trajectory

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alberro, Alexander. 2003. Conceptual Art and the Politic of Publicity. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Rob. 2013. Do We Need Buildings for Digital Art? The Guardian. July 19. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/culture-professionals-blog/2013/jul/19/does-digital-art-need-buildings#start-of-comments (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Ault, Julie. 2011. Remembering and Forgetting in the Archive: Instituting “Group Material’’ (1979–1996). Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Josephine. 2001. The Thematics of Site-Specific Art on the Net. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, Josephine. 2007. Constructing Media Spaces. Mwdien Kunst Netz. February 15. Available online: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/public_sphere_s/media_spaces/10/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Bosma, Josephine. 2011. Nettitudes—Let’s Talk Net Art. Amsterdam: NAi Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bridle, James. 2014. Beyond Pong: Why Digital Art Matters. The Guardian. June 18. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jun/18/-sp-why-digital-art-matters (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Campanelli, Vito. 2010. Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society—Fictions, Invisible Processes. Amsterdam: NAi Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Catlow, Ruth, and Marc Garrett. 2018. Spring Editorial 2018 Blockchain Imaginaries. Furtherfield. January 22. Available online: https://www.furtherfield.org/blockchain-imaginaries/#easy-footnote-bottom-4-38513 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Chan, Jennifer. 2012. From Browser to Gallery (and Back): The Commodification of Net Art 1990–2012. Master’s Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2541835/From_Browser_to_Gallery_and_Back_The_Commodification_of_Net_Art_1990-2010 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Chandler, Annmarie, and Norie Neumark. 2005. At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger, Curt. 2009. Commodify Your Consumption: Tactical Surfing/Wakes ofResistance. Available online: http://lab404.com/articles/commodify_your_consumption.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Connor, Michael. 2015. After VVORK: How (and Why) We Archived a Contemporary Art Blog. Rhizome Blog. September 2. Available online: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/feb/9/archiving-vvork/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Connor, Michael. 2017. ‘Between the Net and the Street’. Rhizome Blog. October 4. Available online: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2017/apr/10/between-the-net-and-the-street/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Cook, Sarah. 2004. The Search for a Third Way of Curating New Media Art: Balancing Content and Context in and out of the Institution. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Sarah, and Marialaura Ghidini. 2015. Internet Art [Net Art]. Sunderland: Grove Art Online-Oxford Dictionary, Available online: http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7002287852 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Cook, Sarah, and Beryl Graham. 2010. Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Geoff, and Joasia Krysa. 2000. On Immaterial Curating: The Generation and Corruption of the Digital Object. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Steve. 1998. Curating on the Web: The Museum in an Interface Culture. In When Is the Next Museums and the Web? Toronto: archimuse.com, Available online: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw98/papers/dietz/dietz_curatingtheweb.html (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Dekker, Annet. 2013. Speculative Scenarios. Eindoven: Baltan Laboratories. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, Lesley, Elizabeth Grierson, and Dianne Waite. 2008. Thinking in a Creative Field. In Thinking through Practice: Art as Research in the Academy. Edited by Lesley Duxbury and Elizabeth Grierson. Melbourne: RMIT Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, Michael Anthony. 2015. The Wrong Biennale: First Impressions. Art Fag City. November 11. Available online: http://artfcity.com/2015/11/11/the-wrong-biennale-first-impressions/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Ghidini, Marialaura. 2015. Curating Web-Based Art Exhibitions: Mapping Online and Offline Formats of Display. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ghidini, Marialaura. 2019. Mostre d’arte sul web: formati di reinterpretazione di un contesto performativo ed esperienze dinamiche. In Arte e Tecnologia. Teorie e pratiche di preservazione. Edited by Domenico Quaranta and Valentino Catricalà. Roma: Kappabit, Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Goriunova, Olga. 2012. Art Platforms and Cultural Production on the Internet. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Reesa. 1996. The Exhibited Redistributed: A Case for Reassessing Space. In Thinking About Exhibitions. Edited by Bruce Ferguston, Sandy Nairne and Reesa Greenberg. New York: Routledge, pp. 349–66. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Rachel. 2004. Internet Art. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Helmond, Anne. 2015. The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Lindsay. 2010. DUMP.FM IRL Press Release. 319 Scholes Website. Available online: http://319scholes.org/exhibition/dump-fm-irl/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Laric, Oliver. 2013. An Incomplete Timeline of Online Exhibitions and Biennials. Rhizome ArtBase. Available online: https://rhizome.org/art/artbase/artwork/an-incomplete-timeline-of-online-exhibitions-and-biennials/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Lialina, Olia. 2013. Net Art Generations. Art Teleportacia. November 19. Available online: http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/net_art_generations/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Lichty, Patrick. 2002. Reconfiguring the Museum. SWITCH, San Jose State University/CADRE. Available online: http://intelligentagent.com/archive/v03%5b1%5d.01.curation.lichty.PDF (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Lind, Maria. 2013. About Working with and Around Tensa Kunsthall. Presentation at LJMU, Liverpool, March 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, Maria, and Liam Gillick. 2005. Curating with Light Luggage: Reflections, Discussions and Revisions. Frankfurt am Main: Revolver. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Oscar. 2016. The Tech behind Bitcoin Could Help Artists and Protect Collectors. So Why Won’t They Use It? Artsy Blog. December 16. Available online: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-tech-bitcoin-could-help-artists-protect-collectors-so-why-won-they-use-it (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Maithani, Charu. 2015. Works of Three Net Artists in India: 1999 Onwards. Sarai Social Media Fellowships Blog. August 29. Available online: http://sarai.net/works-of-three-net-artists-in-india-1999-onwards/#03 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- McHugh, Gene. 2011. Post Internet. Brescia: Link Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Sifry, Micah L. 2016. Trebor Scholz on the Rise of Platform Cooperativism. P2P Foundation Blog. January 11. Available online: https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/trebor-scholz-on-the-rise-of-platform-cooperativism/2016/11/01 (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Miranda, Maria. 2009. Uncertain Practices: Unsitely Aesthetics. Ph.D. Thesis, Macquarie University, Sidney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, Maria. 2013. Unsitely Aesthetics. Berlin: Errant Bodies. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Marisa. 2009. Lost Not Found: The Circulation of Images in Digital Visual Culture. In Words Without Pictures. Edited by Alex Klein. Los Angeles: LACMA, pp. 274–84. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Christiane. 2006. Flexible Contexts, Democratic Filtering, and Computer Aided Curating—Models for Online Curatorial Practice. In Curating Immateriality: The Work of the Curator in the Age of Network Systems. Edited by Joasia Krysa. New York: Autonomedia Press, pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Christiane. 2009. Online Curatorial Practice—Flexible Contexts and “Democratic” Filtering. Art Pulse Magazine. November 28. Available online: http://artpulsemagazine.com/online-curatorial-practice-flexible-contexts-and-democratic-filtering (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Quaranta, Domenico. 2003. Net Art 1994–1998. La Vicenda äda’web. Brescia: V&P Strumenti. [Google Scholar]

- Ramocki, Marcin. 2008. Surfing Clubs: Organized Notes and Comments. Halifax: College of Arts and Crafts, Available online: http://www.ramocki.net/surfing-clubs.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Sakrowski, Robert. 2013. Interview about CYT and An Acoustic Journey Through YouTube Interview by Marialaura Ghidini. In Curating Web-Based Art Exhibitions: Mapping Online and Offline Formats of Display. Edited by Marialaura Ghidini. Ph.D. thesis. Sunderland, UK: University of Sunderland, pp. 188–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sarai Media Lab. 2001. ‘Sarai New Media Initiative’. Daniel Langlois Foundation. January. Available online: www.fondation-langlois.org/html/e/page.php?NumPage=74 (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Schleiner, Anne-Marie. 2003. Fluidities and Oppositions among Curators, Filter Feeders, and Future Artists. Intelligent Agent. Available online: http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/Vol3_No1_curation_schleiner.html (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Scholz, Trebor. 2006. The Participatory Challenge. In Curating Immateriality: The Work of the Curator in the Age of Network Systems. Edited by Joasia Krysa. New York: Autonomedia Press, pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Shai, Ronen, and Thomas Cheneseau. 2012. Gallery Online—About. Gallery Online. Available online: https://gallery0nline.wordpress.com/about/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Skorokhodova, Ekaterina. 2019. Curating in the Digital Age. Semester Thesis, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39224398/Curating_in_the_Digital_Age (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Slocum, Paul. 2016. Catalog of Internet Artist Clubs. Rhizome Archive. Available online: http://archive.rhizome.org/surfclubs/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Stallabrass, Julian. 2003. Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce. London: Tate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Storz, Reinhard. 2014. Interview about Xcult and Beam Me Up. Interview by Marialaura Ghidini. In Curating Web-Based Art Exhibitions: Mapping Online and Offline Formats of Display. Edited by Marialaura Ghidini. Ph.D. thesis. Sunderland, UK: University of Sunderland, pp. 230–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Lumi, and Nicholas Weist. 2008. Online Curation: A Discussion Between Nicholas Weist and Lumi Tan. Rhizome Blog. April 23. Available online: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2008/apr/23/online-curation-a-discussion-between-nicholas-weis/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- The Present Group. 2011. Art Micro Patronage—About. Art Micro Patronage Website. Available online: http://artmicropatronage.org/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Troemel, Brad. 2010. What Relational Aesthetics Can Learn From 4Chan. Art Fag City. September 9. Available online: http://artfcity.com/2010/09/09/img-mgmt-what-relational-aesthetics-can-learn-from-4chan/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- van den Eeden, Amber. 2014. Interview about Temporary Stedelijk. Interview by Marialaura Ghidini. Email. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, R. 2009. Interview with Sarah Tucker (Dia). PACKED. Available online: https://scart.be/?q=en/content/interview-sarah-tucker-dia (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Wunderbar, William Wolfgang. 2017. Wednesday Web Artist of the Week: William Wolfgang Wunderbar Interview by Christian Petersen. Artslant Magazine. August. Available online: https://www.artslant.com/ew/articles/show/48308-wednesday-web-artist-of-the-week-william-wolfgang-wunderbar (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industry. 2019. Interview about Korea Web Art Festival. Interview by Marialaura Ghidini. Email. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | To date the only timeline of web-based exhibitions, An Incomplete Timeline of Online Exhibitions and Biennials, was compiled by artist Oliver Laric (2013)—a work to which I am also indebted for this research. |

| 2 | In Curating in the Digital Age (2019), Ekaterina Skorokhodova (2019) describes how “curating has slipped outside of the artistic field and becomes a sociological phenomenon that has been absorbed into current social structure and culture” the more social media platforms have become the way we communicate with each other. |

| 3 | See also footnote 4. |

| 4 | Bulletin Board System (BBS) is a technology that indicates a computer server to which multiple users can connect through a software on their own computer to access threaded messages in the form of bulletins and upload or download digital files. |

| 5 | Net criticism originated from discussions about internet culture and online art that took place on mailing lists such as Nettime, Rhizome and Eyebeam by net.art artists, critics, technologists and producers from the 1990s. These discussions were characterised by the cacophony of voices of their participants who came from different disciplines, had international perspectives, and discussed in a manner (because of the online medium) that was less rigid than that of art magazines, books and academic publications. Net art criticism started to “fade away” (Bosma 2011, p. 28) with the proclaimed “death” of net.art. And because, it did not comprehensively enter either new media art discourses or contemporary art ones, it was slowly replaced by discourses that often emphasised the visual aspects of art produced online rather than new media theory. Some of the critics who actively wrote about artistic production online during the hiatus are Julian Stallabrass (2003), Rachele Greene (2004), and the already mentioned Cook and Graham, Cox and Krysa (2000), and Paul and Lichty, with reference to curatorial practice. |

| 6 | The term net.art indicates a group of international artists, predominantly located in Europe, who met through the mailing list Nettime in the mid-1990s. They discussed, shared ideas and works that were based on their exploration of the possibilities of the internet and web technology as a “new communication space” (Bosma 2011, p. 130). One of the characteristics of this exploration was the group’s interest in “fostering new independent art organizations and approaches to evade traditional structures” (Bosma 2011, p. 120). The term net.art was coined by Pit Schulz in 1995, and now indicates a period of artistic production that goes from 1995 to about 2002. Amongst these artists are Heath Bunting, Alexei Shulgin, Olia Lialina and JODI. |

| 7 | Seemingly, the competition Curate Award, co-organised by Fondazione Prada and Qatar Museum in 2014, emphasised the figure of the non-professional curator. The call for submissions opened with the following statement: “The competition recognises that we are all curators.” |

| 8 | Artist and critic James Bridle (2014) has argued that “‘the digital’ is not a medium, but a context, in which new social, political and artistic forms arise;” stressing that, however, art “institutions are still trying to work out its relevance, and how to display and communicate it—a marker, perhaps, that it is indeed a form of art.” |

| 9 | Josephine Berry (2001, p. 9) was one of the first researchers to define the web as a medium that combines together “production, publication, distribution, promotion, dialogue, consumption and critique.” |

| 10 | If Julian Stallabrass’ analysis of viewership and engagement online is useful for this study because it proposed a method that included a reflection on the socio-technical status of the web and web tools, his examination only pertained the production of net.art and predominately focused on comparing artistic work online to the system of production enabled by the gallery and the museum. |

| 11 | Many are the critics who have coined metaphors of curatorial work online, such as, the “filter feeder” of Anne-Marie Schleiner (2003) that distils and edits the array of content everyone’s fingertips, to the “cultural producer” of Trebor Scholz (2006) that “sets up contexts for artists to provide contexts.” |

| 12 | With regards to art institutions’ neglect of networked art, Stallabrass (2003) quoted artist Robert Adrian to explain some of the reasons for the disconnect between artists working with the internet network and the institutionalised art world: “The older traditions of art production, promotion and marketing did not apply,” in that these projects did not have a specific product-based outcomes and were often collaborative in nature, “and artists, art historians, curators and the art establishment, trained to operate with these traditions, found it very difficult to recognise these projects as being art.” |

| 13 | Maria Miranda (2009) used the notion “unsitely” to discuss artworks and practices that make use of the internet as “a site of production and reception” and have an “audience spread across the globe in a ‘local’ context of reception.” Because of this, according to the author, they “disrupt our common notions of place and being in one place at one time;” hence they require a different type of art historical categorisation. |

| 14 | Rachel Baker defined these exchanges as a mix of “ranting and poetry, maybe some music files, very short little music files, maybe an image file.” (Connor 2017). |

| 15 | JAVA, the software that allowed users to interact with websites, was released in 1996 and was incorporated in the Mosaic Netscape browser. |

| 16 | See footnote 6. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | It was artist Vuk Ćosić who, critical of the curators’ approach to the project, copied the original website and put it online on a different server with the title Documenta Done. |

| 19 | Media and digital art started to be discussed in India, where Subbaiah was based, in the early 2000s, predominantly through the work of SARAI, the Academy of Electronic Arts, and Apeejay Media Gallery. New Delhi. The scarcity of initiatives across the country made, therefore, the sharing of ideas and collaboration difficult to happen in person from the place where artists were located. |

| 20 | Besides providing a fee to the invited artists, the curators included a Net Art Contest open to Korean artists, to further nurture net.art production and discourses in South Korea. However, despite a cash prize, there were—to the surprise of the curators—very few entries and of low quality (Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industry 2019). |

| 21 | The spread of internet access on a geographic and demographic mass scale in India, in fact, happened with the mobile networks and smartphone devices (early 2010s); which explains the reasons for Barua to adopt the CD-rom format. |

| 22 | Surf Clubs are one of the most discussed phenomena in the context of artistic production online. In fact, the artists involved in these projects, from Marisa Olson (2009) and Marcin Ramocki (2008) to Curt Cloninger (2009) and Brad Troemel (2010), were widely active in promoting a critical discussion of their art and the work they conducted on their platforms. |

| 23 | Jennifer Chan proposed, alongside many others, one of the definitions of postinternet art and artists. According to Chan, postinternet art “differs from the formalist play on code and information architecture that was more visible in late-nineties net.art,” and post internet artists are “more willing to exhibit in galleries […] and modifying artworks for different contexts of presentation in physical space and cyberspace.” (Chan 2012). |

| 24 | In an interview with Michael Connor (2015), VVORK curators stated that “seeing the sequences [of digital images] was useful [to them] to understand tendencies and to view the potential of different interpretations of an idea.” |

| 25 | The serial format of web services was also widely explored in relation to broadcasting art on people’s computer screens, as in the instances of Mitch Trale’s Idle Screening (2012–2014) and Rebecca Birch and Rob Smith’s Field Broadcast (2011–2017). |

| 26 | Julie Ault (2011) aptly described the web context in relation to viewership when discussing online databases, where viewers feel “disoriented and confused” because of the “overloading of short-term memory and user’s difficulty in forming a mental model of the information space.” |

| 27 | I argued elsewhere (Ghidini 2019) how print publishing can function as a way of archiving web-based art. |

| 28 | In conversation with Nicholas Weist about their curatorial work, Lumi Tan expressed her concerns with showing online the work of artists that required “a physical encounter with objects.” She stressed how curators, in dialogue with artists, should understand in which way the artwork would “translate, if at all, to the internet.” (Tan and Weist 2008). |

| 29 | This approach differs from the various independent web festivals that emerged in the same period, whose focus was on creating nodes of distribution. An instance is The Wrong New Digital Art Biennale (2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 forthcoming), founded by David Quiles in Alicante (Spain), which hosts a multitude of web-based projects—the Pavilions—for each edition, often giving life, according to reviewers, to a difficult space for “tracking down individual works” for the lack of a curatorial narrative (Farley 2015). |

| 30 | When collectors buy an artwork on s[edition] they receive a numbered limited edition in digital format, a unique certificate of authenticity and free online storage where the artwork and the certificate are held. Terms and Conditions regulate the use of the purchased art—it cannot be printed for example. s[edition] also offers a subscription service to stream rented digital art. |

| 31 | In the mid-2000s, the unique URL became an intrinsic component of web-based artworks, as in the instance of the practices of Constant Dullaart and Rafaël Rozendaal—an exploration that led to Rozendaal’s Art Website Sales Contract (2011–2014), which was made publicly available to other artists. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghidini, M. Curating on the Web: The Evolution of Platforms as Spaces for Producing and Disseminating Web-Based Art. Arts 2019, 8, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030078

Ghidini M. Curating on the Web: The Evolution of Platforms as Spaces for Producing and Disseminating Web-Based Art. Arts. 2019; 8(3):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030078

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhidini, Marialaura. 2019. "Curating on the Web: The Evolution of Platforms as Spaces for Producing and Disseminating Web-Based Art" Arts 8, no. 3: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030078

APA StyleGhidini, M. (2019). Curating on the Web: The Evolution of Platforms as Spaces for Producing and Disseminating Web-Based Art. Arts, 8(3), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030078