Abstract

With a relational view of landscapes and natural environments as continuously “in process” and formed from the over-layered and interdependent connections between nature and culture, the human and the non-human, this paper considers some recent practices by artists who have worked in the largely rural border region of Northern England and Southern Scotland. Expanding from a focus on the artist Tania Kovats’ 2019 Berwick Visual Arts exhibition, Head to Mouth, and a wider frame of non-anthropocentric ecological thought in relation to the visual arts, it explores the significance of diverse creative engagements with water, here with the River Tweed, and their potential value in a current cross-border context of social and environmental challenges and concern.

1. Introduction

The UK border region of Northern England and Southern Scotland is sparsely populated and often perceived and experienced as marginal and remote, with associations either of peace and tranquility, or of isolation and peripherality. Amidst social and political anxieties wrought by referenda on Scottish Independence (2014) and Brexit (2016), and the environmental problems that face this primarily rural, cross-border location overall, the significance of its shared resources, practices, and identities and the value in this context of recent forms of visual arts practice are important considerations.

The contention here is that cross-border, or ‘borderland’ communities are mutually constituted through longstanding, dynamic human and non-human relations with shared material resources—such as wood, water, wool, soil, and stone. In which case, and despite some historic and legislative distinctions regarding the north and south, we might speak in a progressive sense of the deeply entangled material communities of the borderland. For example, to consider the region’s abundant resource of water is to reflect upon habitual interactions with, and across its streams, tributaries, and confluences, upon rivers that form geo-physical borders at particular points, then flow off in other directions and out into estuaries and along coastlines—the Solway to the west and the North Sea to the east—from where borders and boundaries are meaningful perhaps only for fishing rights. Alongside the continual movement of water flowing throughout the borderland is the conception of place, and of identities, as fluid and unfixed, not static and unchanging. With these concepts in mind, what follows is a study of a recent body of work produced by the artist Tania Kovats related to the borders river, the Tweed, within a larger context of relational thinking about landscape and environment (Massey 1994; Wylie 2007); diverse but connected examples of environmental art, eco-art or eco-activism, and of non-anthropocentric, ecological thought within the visual arts more broadly. Here, I expand on the notion of ‘border-crossing’ as a generative one in both geo-political and conceptual terms.1

2. Natural Environments, Processes, and the Connective Element of Water

Uniting a practice, border-crossing in itself which for past decades has ranged across drawing, sculpture, installation, and writing, Kovats’ central preoccupation has been with environments—as demonstrated in multi-layered projects concerning human relationships to the natural world, with extensive research and travel to the Galapagos islands, the Arctic, New Zealand, and South America. Invested in working ‘with’ natural environments, materials, processes, and systems, early examples include Mountain, (2001), a mountain-making machine replicating the formation of mountain ranges, pushing up rock as folded layers. Emphasising, as here, geological forces of eruption and erosion, landscape is understood to be constantly changing and evolving.

The element of water has been a fundamental concern for Kovats, spanning engagements with the sea, with river systems, maritime culture, flooding, and tides. She perceives water as a ‘connective element’ in the landscape, rivers are formative and a ‘restless energy’, carving the land with glacial action through valleys, coastal erosion, and the shifting of sediments (Kovats in Bright 2018). In the process, geo-political and other borders can be established, but equally weakened and undermined. Her 2016 installation Evaporation, at the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, underlined scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock’s 1970s Gaia hypothesis that all living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings to form a self-regulating system that maintains the conditions for life on the planet. From sculptural bowls cast in the shape of the world’s three largest oceans, to drawings on blotting paper using salt, ink, and processes of evaporation, the work demonstrated the vital, interconnected nature of the blue planet. From 2012 to 2014, Kovats developed the theme of underlying interconnections through practices of water collection. A 2012 installation and permanent collection, Rivers, in the boathouse at Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, displayed bottles of water the artist herself had collected from travels to 100 UK rivers. A related exhibition, Oceans, including the work All the Seas, brought sea water from across the world to the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh in 2014. This was participatory work—if at some distance—to the extent that labelled bottles were sent to the gallery in response to a social media call, demonstrating a widespread public impulse to be part of a symbolic act of connectivity.

Kovats’ sense of the symbolic, social, and cultural, as well as the environmental, significance of water has a parallel in recent observations of a broader cross-disciplinary shift in focus on water—from the hydrological to the hydrosocial. As James Linton and Jessica Budd have outlined, in the context of the ‘hydrosocial cycle’, the move from a hydrological emphasis on ordered and universal systems of water governance brings greater recognition of water’s social dimension. Water and society are here seen to make and remake each other. Water is not an inert backdrop, but in its multiplicities of states, forms, spaces, materialities, and temporalities, it actively embeds and expresses social relations. Increasingly, as they note, water’s entanglements with other ecological processes is regarded as integral to its management (Linton and Budd 2014, pp. 170–80). Following this and adopting a language now regularly shared across disciplines, including the arts, water restoration activities regularly take ‘place-based’ approaches (Westling et al. 2014). This border-crossing between disciplines, practices, experience, and bodies of knowledge is significant for the specific arts practices considered below.

Water collections such as Rivers and All the Seas relate interestingly to artist, sculptor, and filmmaker Amy Sharrocks’ installations, Museum of Water, displayed for example in 2016 at the Wray Castle boathouse on Lake Windermere in the Cumbrian Lake District. Following the severe flooding in Cumbria in 2015, here 700 donated bottles of water—including a 129,000 year old bottle from the Antarctic—were displayed along with accompanying stories and soundscapes—encouraging the public to examine its connection, and develop a new relationship with ‘this most essential to life substance’.2 The bottled water in these collections contains molecules and memories related to rivers and seas that, again, are fundamentally interconnected, if vastly separated in time and space. Kovats and Sharrock’s practices might also be seen in terms of UNESCO’s very recently formed Global Network of Water Museums, which exhibits and interprets ‘natural and cultural, tangible and intangible forms of water civilisation’, to communicate the value of water heritage, understand global water crises, and form potential solutions, in recognition that present problems are not simply resolvable through technocratic processes.3 Most relevant here in an international context is artist Roni Horn’s earlier installation Library of Water (Horn 2007) located in the coastal town of Stykkishólmur in Iceland, with its 24 glass columns containing water collected from ice from major icebergs and recordings of people talking of their experiences of weather and its changes. The shared ambition here is to ‘reconnect people with the liquid element… including social, cultural, artistic and spiritual dimensions’ (watermuseums.net).

As the environmental historian Peter Coates observed, and the above demonstrates, rivers prompt considerations of time and memory, of local, regional, and national identities and, crucially here, of the bioregional—referring to those areas with similar plant, animal, and topographic features that define them over and above the politically organised regions of counties, nations, etc. The Anglo-Scottish borderland indeed could itself be considered a bioregion in this context of shared resources and the formation of material communities. Returning to Coates, rivers are also imbued with human qualities, sometimes gender-specific ones, and he speaks of the ‘personality’ of rivers, as at times temperamental, fickle, sometimes raging, sometimes calm. Discussion of rivers’ ‘agency’ amongst both human and non-human actor networks refers us to Bruno Latour, and to Tim Ingold’s conception of the human being as an organism-in-its-environment (Ingold 2000). Agency, Coates notes, resides in the linkages and relations within a network rather than its individual components (Coates 2013, pp. 23–27). Significant too for the relational focus of this paper is Jane Bennett’s account of ‘vibrant materiality’, the vitality of matter which in itself builds upon Latour’s (2005) definition of an ‘actant’—a source of action that can be either human or non-human (Recognition of this innate agency, of the unruliness, at times, of non-human matter, elements and so on, which possess ‘trajectories, propensities or tendencies of their own’ encourages us to reflect upon, and hopefully readjust, our instinctive tendency to privilege the human over the non-human in favour of “a more distributive agency”(Bennett 2010, pp. vii–xi). For Bennett, the inequality of the former tendency ‘feeds human hubris and our earth destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption’ and prohibits the ‘emergence of more ecological and sustainable modes of production and consumption’, which are vital indeed for human survival (ibid).

3. The River Tweed as ‘Troubled Water’

These considerations are deeply relevant to interactions with the river under discussion here—the 97-mile River Tweed, which for part of its course forms an actual border between Scotland and England and was the focus of Kovats’ 2019 Berwick Visual Arts commission, Head to Mouth, a title recalling lines perhaps from Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha: ‘the river is everywhere at the same time, at the source, and at the mouth… in the oceans and in the mountains…’ (Hesse [1922] 2002, p. 87). The Tweed’s location at the historically and politically contested and yet ‘soft’ border between two nations makes it an especially apt site for Kovats’ interest in what she terms ‘troubled water’. In 1296, King Edward the First captured what had been the vital Scottish trading port of Berwick-upon-Tweed for England, at which time: ‘As leaves in the autumn the Scots fell, and for days the Tweed was stained crimson as it ran across the bar into the great sea beyond, carrying the dead with it’ (Lang 1928, p. 143).4 Forward to 2014 and the moment of the politically tense Scottish independence referendum, two visual arts projects had the Tweed as their focus, both of which compare to Kovats’ own practice in interesting ways, raising wider issues of forms of arts practice and environmental and ecological sensibilities. That referendum had prompted a wider interest in the shared as well as distinct social and cultural heritage and identities of the border region, and the extent to which those who live and work on both sides considered themselves to be ‘borderers’ before being either Scottish or English (Shaw 2018, p. 13). The long history and mutual experience of conflict and the centuries’ long processes of contact and exchange were understood to have produced an essentially hybrid, or cross-border identity.

The annual international Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival had ‘‘Crossing Borders’’ as its theme that year, and the Scottish Borders filmmaker John Wallace showed his Tweed-Sark Cinema in a redundant ice house on the banks of the river. This study of ‘work, place and ecosystems’ was an immersive installation on four screens with a found soundscape drawing on live sensors located across the course of the two rivers—the Sark, which borders England and Scotland in the west, and the Tweed in the east—using documentary footage, archive material, and interviews with those who live their lives in close relation to the rivers (Holt 2018, p. 64). On this, and on a later work, The Same Hillside (2017), Wallace worked in an art–science collaboration with soil scientist Pete Smith using the lens of ecosystem services, in which nature (including natural ecosystems such as rivers) are understood as forms of capital with social and economic value. Extended to the sphere of ‘cultural ecosystem services’, their collaboration also values what are defined as ‘the non-material benefits people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetic experiences’ (Sarukhán and Whyte 2005). Within this latter context, the value of artists in responding and drawing wider attention to natural and environmental processes and to problems related to environmental degradation, climate change etc., is increasingly acknowledged across the academy and beyond (Coates et al. 2014).

One example of this increasing visibility is the 2013–2014 collaborative and participatory ‘Working the Tweed’ project funded by Natural Scotland, which involved Borders’-based environmental artist Kate Foster, writer Jules Horne, composer James Wyness, and choreographer Claire Pençak. Discussed more fully in Pençak’s own contribution to this issue, their place-based approaches are valuable in the context of the other practices considered here. ‘Working the Tweed’ followed a 1995–2005 ‘Tweed Rivers Interpretation Project’ that drew together visual artists, writers, and poets with the understanding that ‘river catchments’… shape identity and forge connections in ways that transcend politics” (Cockburn and Carter 2005). ‘Tweed Rivers’ was a celebratory venture to encourage wider exploration and appreciation of relationships with place and the richness of local cultural life. However, ‘Working the Tweed’ and in that hydro-social context discussed above, brought together scientists, local environmental organisations, land owners, businesses, and communities and, similar to Wallace and Smith’s collaboration, was also connected to cultural ecosystem services thinking, exploring through diverse creative forms and methodologies the interconnected ecologies related to the river, past forms of knowledge, submerged local histories, voices, music, and language. This knowledge was seen to be of value at the time to the developing Scottish Borders Council Land Use Strategy, raising issues of the instrumental role of arts projects in support of wider policies. Artists’ intentionality is key here, of course. Some artists, understandably, are content to be instrumentalised if their practices encourage greater sensitivity and responsibility to fragile environments.

For The Same Hillside, another immersive form of looped video and audio installation, Wallace and Smith explored upland ecosystems, in particular the location in the Lowther Hills in the Scottish southern uplands where three major rivers—the Tweed, the Annan, and the Clyde—all have their source. Their installation traces the interconnections between life-supporting reservoirs, carbon-storing blanket bogs, economically struggling hill farms, commercial forestry and subalpine habitats, human stories and so on, taking what is termed a watershed-based approach, underlining the extent to which the communities below and beyond the hillside all depend on the healthy sustainability and resilience of this particular upland area.

Wallace and Smith’s educative, or in Chris Fremantle’s terms “gently activist” (Fremantle 2017) “upstream” approach relates to but takes a different form in Alec Finlay and Gill Russell’s th’ fleety wud, 2017. Here, an environmental arts, ecopoetic collaboration which they termed “a remediation proposal” focussed on the implications of climate change through close consideration of the Upper Teviot watershed—the Teviot river itself flows on into the larger River Tweed. Alec Finlay describes th’ fleety wud as a “place-aware” project, and it drew upon Douglas Scott’s 2005 Hawick Word Book, which is a vast and detailed account of local history and language. ‘A fleety wud’ is translated there as the flooding wood, although as Finlay observed, it’s not the wood that floods, but the heugh (the level ground) below. He and Russell developed a walking and naming practice, which Finlay termed “the new walking”, as derived from 19th century Scottish naturalist William MacGillivray, who suggested that the “botanically minded should walk alongside a river to its source, making digressions, using the returning journey to carry out closer inspections of objects of interest. The learning comes in the to-and-fro” (Finlay 2017). MacGillivray appears as a precursor here to the various artist-walking strategies relating to land and environmental art practices that have evolved since the 1970s and to that recent emphasis in social science disciplines on a multi-sensory, embodied engagement with place that is not “merely symbolically read but is somatically experienced and apprehended” (Edensor 2017, p. 597). Crucial for Finlay is the call for action that proper understanding of an ancient place-name—‘th’ fleety wud’—brings with it, namely to “take the arboreal form of the watershed as a hint to plant trees”, to recognise that “we need to form a new commons at the head of each river and plant them with woods”, or otherwise “neglect your watershed and you must be prepared to heap sandbags”.5

Another Scottish Borders water-based arts practice relevant to the discussion of Kovat’s work in Berwick is the “durational performance with watercourse” that Glasgow artists Minty Donald and Nick Millar conducted for the 2015 Environmental Arts Festival (EAF) staged in sites across rural Dumfriesshire to the west of the region. This was also a walking-related work, one the artists had performed elsewhere, but involving local community participation in a sensorial, playful, and even absurdist exploration of human–water relations titled Guddling About (Scots for fishing using just fingers, but also for messing around). Pertinent too perhaps to Claire Pencak’s choreographic methods, Donald drew upon feminist theorist Karen Barad’s notion of “intra-action” and invited Fluxus-inspired, active engagements with water through the form of a score designed, as she wrote, to encourage exploration of human and non-human, human and water interrelations. The score developed for the EAF festival and for other “watermeets” experiments to date has called upon participants to “borrow” small flasks of water from streams and rivers, ask the rivers’ permission and then thank them, label and line up flasks from different watercourses, and then introduce the samples to each other. Actions include the impossible task of carrying river water in the hands. Donald is concerned here with avoiding what performance theorist Rebecca Schneider views as the, at times, “reductively homogenising” emphasis of new materialist philosophies such as Jane Bennett’s. In Schneider’s terms, “considering the world as an entanglement of vibrant matter can… [negate] variances and antagonisms and working against the formation of any kind of meaningfully differentiated entities” (Donald 2016, p. 255). However, Bennett’s own particular emphasis on the “capacity of things to… impede or block the will and designs of humans” (Bennett 2010, p. vii) seems to me to avoid that suggestion. Schneider and Donald’s larger point about the risks of a “potential essentialism” as it might apply within certain environmental arts practices is well made, and emphasis on potential difference and antagonism is central within relational thinking.

Following all of the examples above, there are some common preoccupations throughout Kovats’ water-based work to date and a sense of past themes and approaches sensitively attuned to the specificity of place. Although the Berwick commissioned work is not participatory, collaborative, socially engaged, or overtly eco-activist, there have certainly been examples of those approaches in her past practice. As with the other artists considered above, the hydro-social and a cultural eco-system approach, if not adopted explicitly here, clearly has resonance. Similar to Working the Tweed, Cinema Tweed-Sark, and The Same Hillside, Head to Mouth references the river’s source—its first crossing as a wooden plank in the Lowther Hills—through to its meeting with the sea at Berwick. As in th’ Fleety Wud, the artist’s own walking and tracing the course of a river—here in sections over several weeks—was a vital engagement, providing an embodied, sensory experience of its changing mood, colour, forms, and temporalities; in other words, it showcased its various personalities, as in Peter Coates’ terms above. Similar to Finlay and Russell, Kovats is interested in the particular language associated with or emanating from the Tweed. In her focus on the river as both a geo-physical and a psychological border, it is both bilingual—Scots and English—and gendered. Similar to Guddling About, in extending her previous water-collecting practices, the work engages the river’s unique identities as shifting, various, and endlessly in flux.

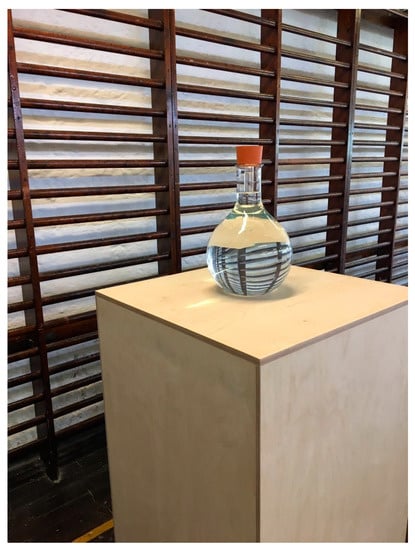

Head to Mouth was installed in Berwick Visual Arts’ Gymnasium Gallery, which is part of the 18th century barracks next to the town’s ramparts, and so an appropriate location for artworks engaged with borders and boundaries. The water collection element takes the form of glass vessels on plinths. One is filled with water gathered underneath the Union Chain Bridge, which is the 19th century suspension bridge that spans the river between Horncliffe, the northernmost village in England, and the parish of Fishwick in Berwickshire, Scotland, seven miles upstream from the ‘English’ town of Berwick itself. If waters are indeed identified with nations, there is symbolic and bioregional intermingling here (Figure 1). On the second plinth, two glass vessels are joined at their neck by a clear moulded tube, or pipe, as shown in Figure 2. One side contains water from the source, or the head of the river, while the other contains water from its mouth—hence the title. For Kovats, art itself is a vessel of the self, one of containment, leakage, and communication; the liquid, in this sense, is a stand in for the self. To hold the self is as hard as holding liquid in the hands. A theme throughout the Gymnasium exhibition is liquidity and “our liquid selves”, registering again that theme of interconnection, the intermingling of human and non-human elements, or matter.

Figure 1.

Tania Kovats, Head to Mouth, 2019 (courtesy of the artist. Photo author’s own).

Figure 2.

Tania Kovats, 2019, Head to Mouth (courtesy of the artist. Photo. Janina Sabialauskaite).

An earlier, 2016–2017 residency for Kovats, ‘Thames Tideway’ resulted in a limited edition artwork that took the form of a newspaper titled Dirty Water, which began with a ‘Letter from the Editor’, old River Thames herself: “I am an old river. I want to tell you some things while I can.” Dredging up memories long-settled in sediments, the river remembers her youth as a sparkling wide, restless stream. She recalls pilgrimages once made to her and offerings later dug up as finds, and later the plastic bags, bottles, and stinking sewage thrown in and flushed out on her tides. The newspaper reproduces classic images representing historical moments and scenes from her past, of murder, of those “found drowned” and so on; and of those artists, such as Turner, who could translate her mood. It references literary figures, such as Dickens, and the narratives into which the river is wound, so becoming a metaphor. Still, old woman river looks forward to the future. At low tide on the morning of the autumn equinox, 6000 copies of Kovats’ artwork were given away at locations from east to west along her course (Tideway 2017).

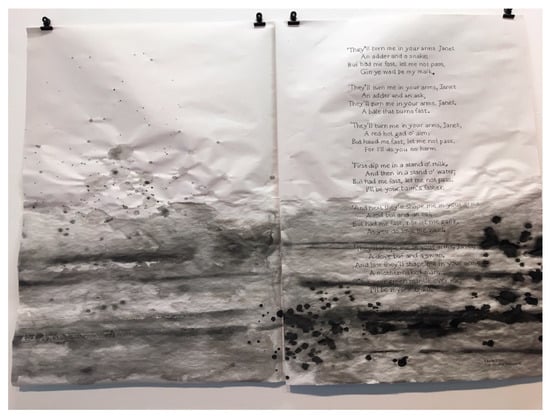

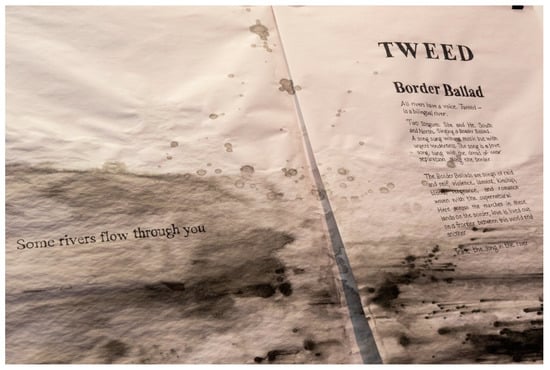

The Thames and Tweed are extreme contrasts; the Tweed is largely a rural river with little industry on its banks, and is therefore famous for its salmon. The Gymnasium exhibition includes a series of images specifically related to the Tweed that are hung on screens, ultimately to be printed and distributed locally in a newspaper format. These are paper sheets into which ink and paint has seeped, forming atmospheric dabs and horizontal bands that suggest river surfaces and mist. Overlaid is a hand-written transcription of the Borders ballad, Tam Lin of Carterhaugh, which is an imaginary location, as shown in Figure 3. That this is a ballad of the supernatural and not a “reivers”, or raiding, ballad is significant.6 The Tweed is freighted with myth, legend, and poetry. For example, Merlin the magician, the last of the Druids, was allegedly cast into the river at its confluence with the river Powsail near the village of Drumelzier. Much Borders legend of course is associated with Sir Walter Scott, whose house, Abbotsford, overlooks the river near the small town of Melrose. Tam Lin is understood to have been written in the 13th century, but with roots in earlier centuries and several transformations later, and the artist Iain Biggs in own extensive research on the ballad—with much walking of the Border country too—cites it as between Pagan and Christian cultures (Biggs 2004).7 Tam Lin, both hunter and hunted, was once an “earthly knight” but was taken captive by the Queen of the Fairies. To rescue him on All Hallows Eve, when the fairies ride, Janet (or Lady Margaret) must endure the magical spells that have been cast upon him and hold on to him as he shape-shifts from wolf, to adder, to a red hot iron, to dove, etc., and finally to a naked knight. ‘Linn’ is an original borders name for a waterfall or rushing water, and so for Janet to hold onto the knight is also as hard as holding water in the hands.

Figure 3.

Tania Kovats, Head to Mouth, 2019 (courtesy of the artist. Photo author’s own).

Kovats’ engagement with Tam Lin in the context of this exhibition resonates with the wider references in this paper to entangled interpenetrations between the human and the non-human. Here are other forms of border-crossing; of permeable boundaries between the visible and invisible, the real and the imaginary, the natural and the supernatural. To counter the reservations of Schneider above, this particular entanglement of matter at least is full of variance and antagonism. This section of Head to Mouth then segues into a contemporary supernatural love story, with the voices of the river, and written by Kovats herself, prompting connections between past, present, and potential futures and asking, “Who are you to tell me what is real and what is not?” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Tania Kovats, 2019, Head to Mouth (courtesy of the artist. Photo Janina Sabialauskaite).

A third element of the exhibition speaks again to a gendering of rivers, and sea, as female. It consists of a series of headless aquatic figures cast in concrete using wetsuits as moulds (Figure 5). They appear caught in the act of diving into the water, although actually and incongruously into the marked up wooden gymnasium floor. All but one of the forms are female and for the most part ungainly and unidealised. For figures shaped out of concrete, they appear slippery and unruly. They seem to bulge out of the (now removed) constraining wetsuits whose rubbery internal texture is still imprinted into their concrete flesh, and the visible remains of wetsuit zips suggest an entry point between the inside and outside of their forms. Although these seem prosaic, everyday figures, in conversation, Kovats references the Scottish maritime legend of the Selkies, the mythical female figures who appear as seals in the water but are capable of shedding their skins on land and assuming everyday human lives. However, if they should come upon their skins at any time, they will desert their human husbands and children and flea back to the sea, becoming seals once again. Similar to Tam Lin, these are mutable, shape-shifting figures that are closely identifiable with place and endlessly border-crossing between the human and non-human.

Figure 5.

Tania Kovats, 2019 Head to Mouth (courtesy of the artist. Photo Janina Sabialauskaite).

4. Conclusions

While, as above, Head to Mouth seems not explicitly to be environmental or eco-art, there is nevertheless a deeply ecological consciousness at play here that connects the work to other borders-related art practices that are rather more overtly concerned with, for example, contemporary problems of land use and the impact of climate change. However, with a shared sensibility and certain methodologies in common, Kovats’ Gymnasium installation deep dives into the history, the cultural heritage, legend, language, and so on of place—here of a vital section of the borderland’s natural environment. From the perspectives of both performance theory and archaeology, Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks once observed of “deep mapping” strategies—which also have some resonance with the works so far discussed—that:

Reflecting 18th-century antiquarian approaches to place, including history, folklore, natural history, and hearsay, the deep map attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and the interpenetration of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the fantastical and the fictional, the discursive and the sensual… and everything you might ever want to say about a place.(Pearson and Shanks 2001, p. 64)

The claim here is that the art practices considered all speak in various ways to the notions of crossing borders, dissolving boundaries, and making connections between diverse forms of life, inanimate objects, and materials associated with the region’s vital and watery border-forming rivers. To this extent, they can be understood as operating with future-oriented potential for a region facing social, cultural, and environmental challenges. Beyond engaging directly with communities, councils, and conservationists in collaborative and creative ways to support necessary shifts in understanding and greener forms of behaviour, they demonstrate the wider significance and implications of interconnected ways of thinking, of remembering, belonging, being, and doing within environments through a profound investment in the material human and non-human resources of place. Indeed, the arts have a particular value in this regard. Heather Davis and Etienne Turpinhave argued cogently that of crucial importance now are “visual, discursive and sensual strategies that are not confined by the regimes of scientific objectivity, political moralism or psychological depression” (Davis and Turpin 2015, p. 4). There is a broader issue of agency here, and of an equally necessary optimism to be drawn from thinking through, and from living “with”, not “off”, for example, the material communities of a borderland which, to this degree and from the legacy of these recent art practices, might well prove to be a generative space from which to contemplate the future. In broader contexts here, UK and Scottish Government cross-bordering policy initiatives such as the 2019 ‘Borderlands Inclusive Growth Deal’ intended to support “quality of place” and “sustainable and inclusive” futures for the South of Scotland and the North of England will require exactly the kind of relational thinking these art practices present if they are to succeed in their ambitions (borderlandsgrowth.com).8

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Tania Kovats for the conversation that initiated this research and to the journal’s two anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, Iain. 2004. Between Carterhaugh & Tamshiel Rig: A Borderline Episode. Bristol: Wild Conversation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, Richard. 2018. ‘Mediating between Nature and Self’, interview with Tania Kovats. Interalia Magazine. Available online: https://www.interaliamag.org/interviews/tania-kovats/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Coates, Peter. 2013. A Story of Six Rivers: History, Culture and Ecology. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, Peter, Emily Brady, Andrew Church, Ben Cowell, Stephen Daniels, Caitlin DeSilvey, Rob Fish, Vince Holyoak, David Horrell, Sally Mackey, and et al. 2014. UK National Ecosystem Assessment Follow-on Work Package Report 5: Arts & Humanities Annex 1—Perspectives on Cultural Ecosystem Services. Arts & Humanities Working Group Final Report. Cambridge: UNEP-WCMC. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, Ken, and James Carter, eds. 2005. Tweed Rivers: New Writing and Art Inspired by the Rivers of the Tweed Catchment. Edinburgh: Luath Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Heather, and Etienne Turpin, eds. 2015. Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. London: Open Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, Minty. 2016. ‘The Performance ‘apparatus’: Performance and its documentation as ecological practice’. Green Letters, Studies in Ecocriticism 20: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Edensor, Tim. 2017. ‘Rethinking the landscapes of the Peak District’. Landscape Research 42: 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, Alec. 2017. Available online: https://alecfinlayblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/th-fleety-wud.html (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Fremantle, Chris. 2017. Available online: http://www.sustainablepractice.org/2017/05/28/the-same-hillside/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Hesse, Herman. 2002. Siddharta. London: Penguin. First published 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Ysanne. 2018. ‘Performing the Anglo-Scottish Border: Cultural Landscapes, Heritage and Borderland Identities’. Journal of Borderland Studies 33: 1, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, Roni. 2007. Available online: https://www.artangel.org.uk/project/library-of-water/ (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Jean. 1928. A Land of Romance: The Border, Its History and Legend. London and Edinburgh: T.C. & E.C. Jack. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, James, and Jessica Budd. 2014. ‘The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilising a relational-dialectical approach to water’. Geoforum 57: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, Mike, and Michael Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 2005. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Synthesis Report. Available online: http://matagalatlante.org/nobre/down/MAgeneralSynthesisFinalDraft.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Shaw, Keith. 2018. ‘Bringing the Anglo-Scottish Border “Back in”: Reassessing Cross-border Relations in the Context of Greater Scottish Autonomy. Journal of Borderlands Studies 33: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tideway, Thames. 2017. Available online: https://www.tideway.london (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Westling, Emma, Ben Surridge, Liz Sharp, and David Lerner. 2014. Making sense of landscape change: Long term perceptions among local residents following river restoration. Journal of Hydrology 519: 2613–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, John. 2007. Landscape. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This article has its origins in a gallery ‘in-conversation’ between the author and Tania Kovats at the opening of her exhibition ‘Head to Mouth’ commissioned by Berwick Visual Arts for the Gymnasium Gallery, Berwick-upon-Tweed in June 2019. Thanks to the artist, to James Lowther, Head of Visual Art, Berwick Visual Arts, and to the audience for their contributions on that day. |

| 2 | http://www.museumofwater.co.uk/water-museum/ (accessed on 20 June 2019). |

| 3 | Water Museums Global Network. Available online: https://www.watermuseums.net/project/ (accessed on 20 June 2019). |

| 4 | Berwick changed between English and Scottish hands thirteen times through the Border wars of the Middle Ages. |

| 5 | Alec Finlay discussed ‘Th Fleety wud’ at a pecha kucha event, ‘Mapping the Borders: Charting Change’ organised by Inge Pannels in November 2017. The presentation can be viewed here: https://www.pechakucha.com/cities/galashiels/presentations/mapping-the-borders-charting-change. |

| 6 | The “Border Reivers” were outlaw figures who terrorised both sides of the Anglo-Scottish border from the 13th to early 17th centuries, burning homes, taking lives, and stealing livestock. |

| 7 | Iain Biggs notes that Walter Scott claimed Carterhaugh existed at the confluence of Yarrow Water and Etterick Water—outside Selkirk. Both rivers flow into the Tweed. |

| 8 | Borderlands Inclusive Growth Deal. Available online: http://www.borderlandsgrowth.com/ (accessed on 9 August 2019). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).