Mixed-Media Domestic Ensembles in Roman Sicily: The House of Leda at Soluntum

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Soluntum’s History and Excavation

3. A Walk through the House of Leda

4. Cross-Media Dialogue in Stone and Marble

4.1. A “Statue” of Leda and the Swan

4.2. Faux Marble Blocks, Decorative Stone Floors

5. The Owner of the House of Leda

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aberle, Karen Ann. 2012. Studies in the Urban Domestic Housing of Mid-Republican Sicily (ca. 211–70 BC): Aspects of Cross-Cultural Contact. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver and Kelowna, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Fabio. 2017. ‘Painting in stone’: Early modern experiments in metamedium. Art Bulletin 99: 30–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartman, Elizabeth. 1988. Decor et Duplicatio: Pendants in Roman Sculptural Display. American Journal of Archaeology 92: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Malcolm. 2011. Osservazioni sui mosaici greci della casa di Ganimede a Morgantina. In Pittura ellenistica in Italia e in Sicilia: linguaggi e tradizioni. Edited by Gioacchino Francesco La Torre and Mario Torelli. Roma: G. Bretschneider, pp. 105–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2002a. Art and Nature in the Villa at Oplontis. In Pompeian Brothels, Pompeii’s Ancient History, Mirrors and Mysteries, Art and Nature at Oplontis & the Herculaneum “Basilica”. Edited by Thomas A. McGinn. Journal of Roman Archaeology suppl. 47: 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Bettina. 2002b. Playing with Boundaries: Painted Architecture in Roman Interiors. In The Built Surface. Volume 1, Architecture and the Pictorial Arts from Antiquity to the Enlightenment. Edited by Christy Anderson and Karen Koehler. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Mark. 2006. Colour and Marble in Early Imperial Rome. The Cambridge Classical Journal 52: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlot, Delphine, and Daniel Roger. 2012. Les Muses des praedia de Julia Felix. Paris: Louvre éditions. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, Marietta. 1975. Pitture e mosaico a Solunto. BABesch 1: 195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Di Christina, Luciana Nattoli. 1966. Caratteri della cultura abiativa soluntina. In Scritti in onore de Salvatore Caronia. Edited by Salvatore Caronia Roberti. Palermo: La Cartografia, pp. 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, Sheila. 2012. Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects and Styles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jas. 2007. Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fant, Clayton. 2007. Real and Painted (Imitation) Marble at Pompeii. In The World of Pompeii. Edited by John Joseph Dobbins and Pedar William Foss. London: Routledge, pp. 336–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fresina, Adriana. 2014. Introduzione Storico-Archeologica. In Solunto: paesaggio città architettura. Edited by Alberto Sposito. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goulet, Crispin Corrado. 2001. The “Zebra Stripe” Design: An Investigation of Roman Wall Painting in the Periphery. Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 12–13: 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, Caterina. 1997. Pavimenti in opus signinum e tessellati geometrici da Solunto: Una messa a punto. In Atti del IV Colloquio dell’Associazione italiana per lo studio e la conservazione del mosaico, Palermo, 9–13 dicembre 1996. Edited by Rosa Maria Bonacasa Carra and Federico Guidobaldi. Ravenna: Edizioni del Girasole, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, Caterina. 2011. I sistemi decorativi di Solunto: Appunti e riflessioni. In Pittura ellenistica in Italia e in Sicilia linguaggi e tradizioni: atti del convegno di studi, Messina, 24–25 settembre 2009. Edited by Mario Torelli and Gioacchino Francesco La Torre. Roma: Giorgio Bretschneider, pp. 279–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kahil, Lily, and Pascale Linant De Bellefonds. 1992. Leda. In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VI. Zurich: Artemis. [Google Scholar]

- Laken, Lara. 2003. Zebra Patterns in Campanian Wall Painting: A Matter of Function. BABesch 78: 167–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lancha, Janine. 1994. Mousa/Mousai/Musae. In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VII. Zurich: Artemis. [Google Scholar]

- Marconi, Clemente. 2011. The Birth of an Image: The Painting of a Statue of Herakles and Theories of Representation in Ancient Greek Culture. RES 59/60: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, Clemente. 2013. Sculpture in Sicily from the Age of the Tyrants to the Reign of Hieron II. In Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome. Edited by Claire L. Lyons, Michael Bennett and Clemente Marconi. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 159–73. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. Rebecca. 2017. The Art of Contact: Comparative Approaches to Greek and Phoenician Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

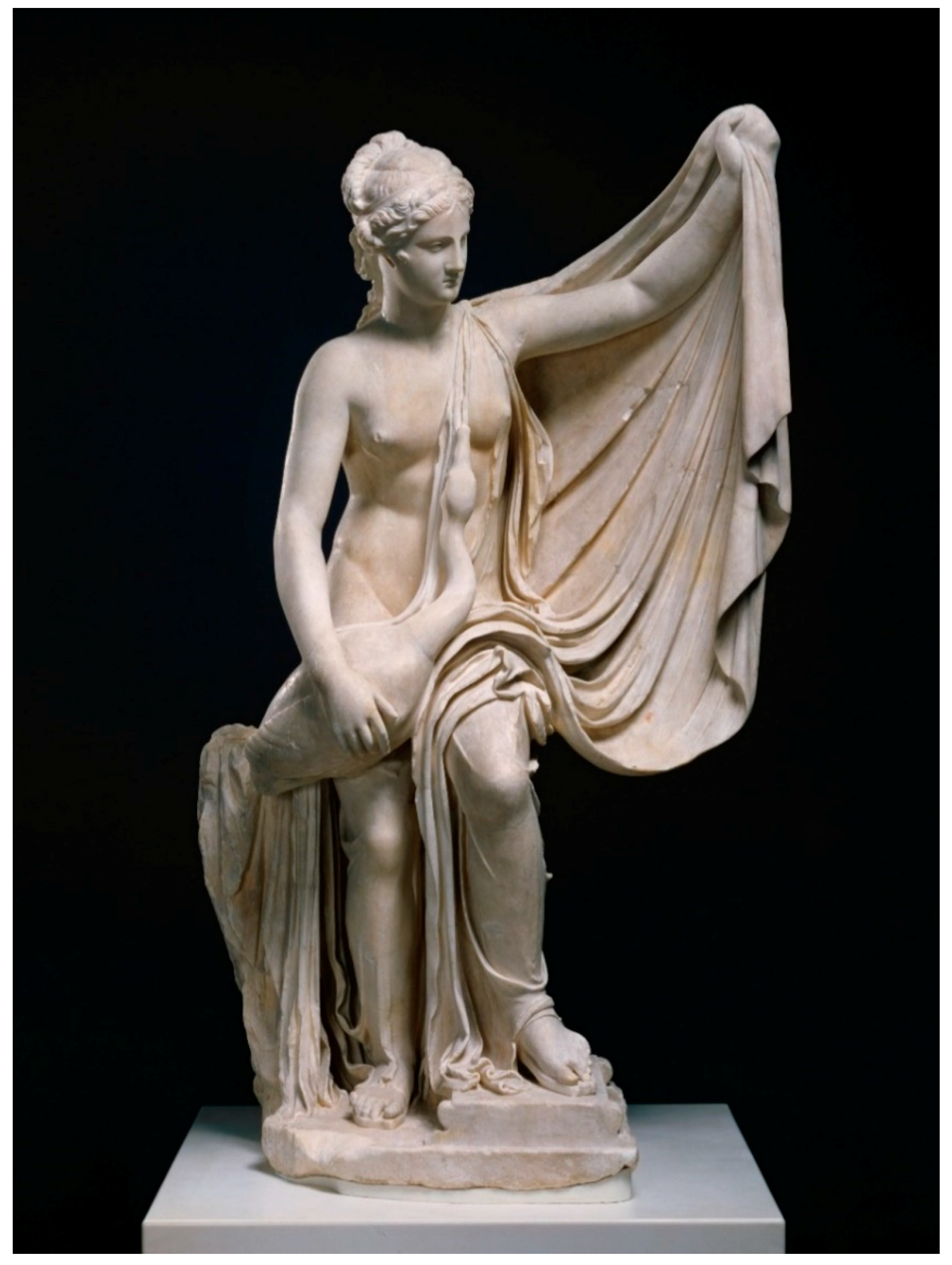

- Marvin, Miranda. 2008. The Language of the Muses: The Dialogue between Roman and Greek Sculpture. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, Lynley. 2014. Marble, Memory, and Meaning in the Four Pompeian Styles of Wall Painting. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, Lynley. 2016. Heirlooms on the Walls: Republican Paintings and Imperial Viewers. In Beyond Iconography: Materials, Methods, and Meaning in Ancient Surface Decoration. Edited by Sarah Lepinski. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America, pp. 167–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moormann, Eric M. 1988. La pittura parietale romana come fonte di conoscenza per la scultura antica. Assen and Wolfeboro: Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Moormann, Eric M. 2008. Statues on the Wall: The Representation of Statuary in Roman Wall Painting. In The Sculptural Environment of the Roman Near East: Reflections on Culture, Ideology, and Power. Edited by Yaron Z Eliav, Elise A Friedland and Sharon Herbert. Leuven and Dudley: Peeters, pp. 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mulliez, Maud. 2014. Le luxe de l'imitation: Les trompe-l'oeil de la fin de la République romaine, mémoire des artisans de la couleur. Napoli: Centre Jean Berard. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, Alessandra. 2013. Hellenistic Tradition in the Mural Painting of Ancient Sicily. In Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome. Edited by Claire L Lyons, Michael J Bennett and Clemente Marconi. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 202–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nevett, Lisa. 2011. Housing and Cultural Identity: Delos, Between Greece and Rome. In Domestic Space in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Marden. 2016. Vitruvius on Vermillion: Faberius’s Domestic Decor and the Invective Tradition. Arethusa 49: 317–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Marden. 2017. Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De Architectura. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pfuntner, Laura. 2019. Urbanism and Empire in Roman Sicily. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Verity. 2018a. Double Vision: Epiphanies of the Dioscuri in Classical Antiquity. Archiv Für Religionsgeschichte 20: 229–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Verity. 2018b. Of sponges and stones: Matter and ornament in Roman painting. In Ornament and Figure in Graeco-Roman Art: Rethinking Visual Ontologies in Classical Antiquity. Edited by Nikolaus Dietrich and Michael Squire. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, GmbH, pp. 241–78. [Google Scholar]

- Portale, Elisa Chiara. 1997. I mosaici nell aparato decorativo delle case ellenistiche siciliane. In Atti del IV Colloquio dell’Associazione italiana per lo studio e la conservazione del mosaico, Palermo, 9–13 dicembre 1996. Edited by Rosa Maria Bonacasa Carra and Federico Guidobaldi. Ravenna: Edizioni del Girasole, pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Portale, Elisa Chiara. 2001. Per una rilettura delle arti figurative nella Provincia Sicilia: Pittura e mosaico tra continuità e discontinuità. SEIA 6–8: 43–90. [Google Scholar]

- Portale, Elisa Chiara. 2006. Problemi dell’archeologia della Sicilia ellenistico-romana: Il caso di Solunto. Archeologia Classica 5: 49–107. [Google Scholar]

- Portale, Elisa Chiara. 2007a. A proposito di ‘romanizzazione’ della Sicilia. Riflessioni sulla cultura figurativa. In La Sicilia romana tra Repubblica e Alto Impero: atti del Convegno di studi, Caltanissetta 20–21 maggio 2006. Edited by Calogero Micciché, Simona Modeo and Luigi Santagati. Caltanissetta: Siciliantica, pp. 150–69. [Google Scholar]

- Portale, Elisa Chiara. 2007b. Per una rilettura del II stile a Solunto. In Villas, maisons, sanctuaires et tombeaux tardo-républicains: découvertes et relectures récentes: Actes du colloque international de Saint-Romain-en-Gal en l’honneur d’Anna Gallina Zevi: Vienne, Saint-Roman-en-Gal, 8–10 février 2007. Edited by Anna Gallina Zevi and Bertrand Perrier. Roma: Quasar, pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Jessica Davis. 2006. Patrons, Houses and Viewers in Pompeii: Reconsidering the House of the Gilded Cupids. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Jessica Davis. 2011. Beyond Painting in Pompeii’s Houses: Wall Ornaments and Their Patrons. In Pompeii: Art, Industry, and Infrastructure. Edited by Eric Poehler, Miko Flohr and Kevin Cole. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sposito, Alberto. 2014. Solunto: paesaggio città architettura. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, Michael. 2013. Embodied Ambiguities on the Prima Porta Augustus. Art History 36: 242–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Peter. 2003. Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble, Jennifer. 1999. Replicating the Body Politic: The Herculaneum Women Statue Types and the Construction of Identity. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakirgis, Barbara. 1989. The Decorated Pavements of Morgantina I: The Mosaics. American Journal of Archaeology 93: 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusa, Vincenzo. 1972. Solunto nel quadro della civiltà punica della Sicilia Occidentale. Sicilia Archeologia 5: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tusa Cutroni, Aldina. 1994. Solunto. Roma: Libreria dello Stato, Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Valladares, Hérica N. 2005. The Lover as a Model Viewer: Gendered Dynamics in Propertius 1.3. In Gendered Dynamics in Latin Love Poetry. Edited by Ellen Greene and Ronnie Ancona. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 206–42. [Google Scholar]

- Valladares, Hérica N. 2014. Pictorial Paratexts: Floating Figures in Roman Wall Painting. In The Roman Paratext: Frame, Texts, Readers. Edited by Laura Jansen. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Von Boeselager, Dela. 1983. Antike Mosaiken in Sizilien: Hellenismus und römische Kaiserzeit, 3. Jh. v. Chr.-3. Jh. n. Chr. Roma: Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1994. Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 2010. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Roger. 1990. Sicily Under the Roman Empire: The Archaeology of a Roman Province, 36 BC–AD 535. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Roger. 2012. Agorai and fora in Hellenistic and Roman Sicily: An overview of the current status quaestionis. In Agora greca e agorai di Sicilia. Edited by Carmine Ampolo. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, pp. 245–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Markus. 2003. Die Häuser von Solunt und die hellenistische Wohnarchitektur. Mainz am Rhein: Von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Markus. 2013. Die Agora von Solunt: öffentliche Gebäude und öffentliche Räume des Hellenismus im griechischen Westen. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, 14.48 and 20.69. Soluntum was intended as a “retirement” settlement for Agathocles’ soldiers, who had been fighting in North Africa against Carthaginian forces. The Greek soldiers would have been transported directly from North Africa to the northern Sicilian coast. |

| 2 | Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, 23.1 and 23.18. |

| 3 | It is hypothesized by excavator Vincenzo Tusa that the two Punic sanctuaries of Soluntum were in use through the second century CE, suggesting that even in the Roman period the city’s residents were worshipping Punic deities. See (Tusa 1972, p. 41). |

| 4 | For more on the agora of Soluntum, see (Wolf 2013) and (Wilson 2012) for those on Sicily more generally. |

| 5 | Elisa Chiara Portale has written extensively on Sicilian houses, especially those from Soluntum. See (Portale 1997, 2001, 2006, 2007a). |

| 6 | Marcus Tullius Cicero, Against Verres, 2.3.103. This is an example of rhetorical exaggeration on the part of Cicero, given Soluntum’s occupation well into the Roman Imperial period. |

| 7 | Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 3.14 (8). Pliny the Elder’s description of Soluntum as a smaller city or town seems to be accurate as, unlike the lager cities of Tyndaris and Agrigento, it was not deemed important enough to be given the status of colony during the Roman Empire. |

| 8 | For more on the gradual abandoment of Soluntum, see (Pfuntner 2019, pp. 62–66). |

| 9 | “…a most ancient city today totally in ruins.” Fazello’s recognition of the site came from Soluntum’s fortification walls on the western edge of the city that still remain on the cliffs of Mount Catalfano. The most complete history of the excavations at Soluntum can be found in (Fresina 2014, pp. 9–12). |

| 10 | Further excavations occurred under Francesco Paolo Perez in 1863, Professor Giuseppe Patricolo in 1868 and 1869 when the frescoes from the House of the Masks were discovered, and in 1875 under Francesco Cavallieri, the director of the Commissione di Antichità e Belle Arti di Sicilia (Fresina 2014, pp. 9–12). |

| 11 | During this excavation three integral points of information about Soluntum came to light—that it had a strong Punic presence through most of the city’s life, that it was laid out according to a Hippodamian grid plan, and that it had relationships with other cities both near and far around the Mediterranean (Tusa Cutroni 1994, pp. 15–16). |

| 12 | See, for example, (Di Christina 1966). |

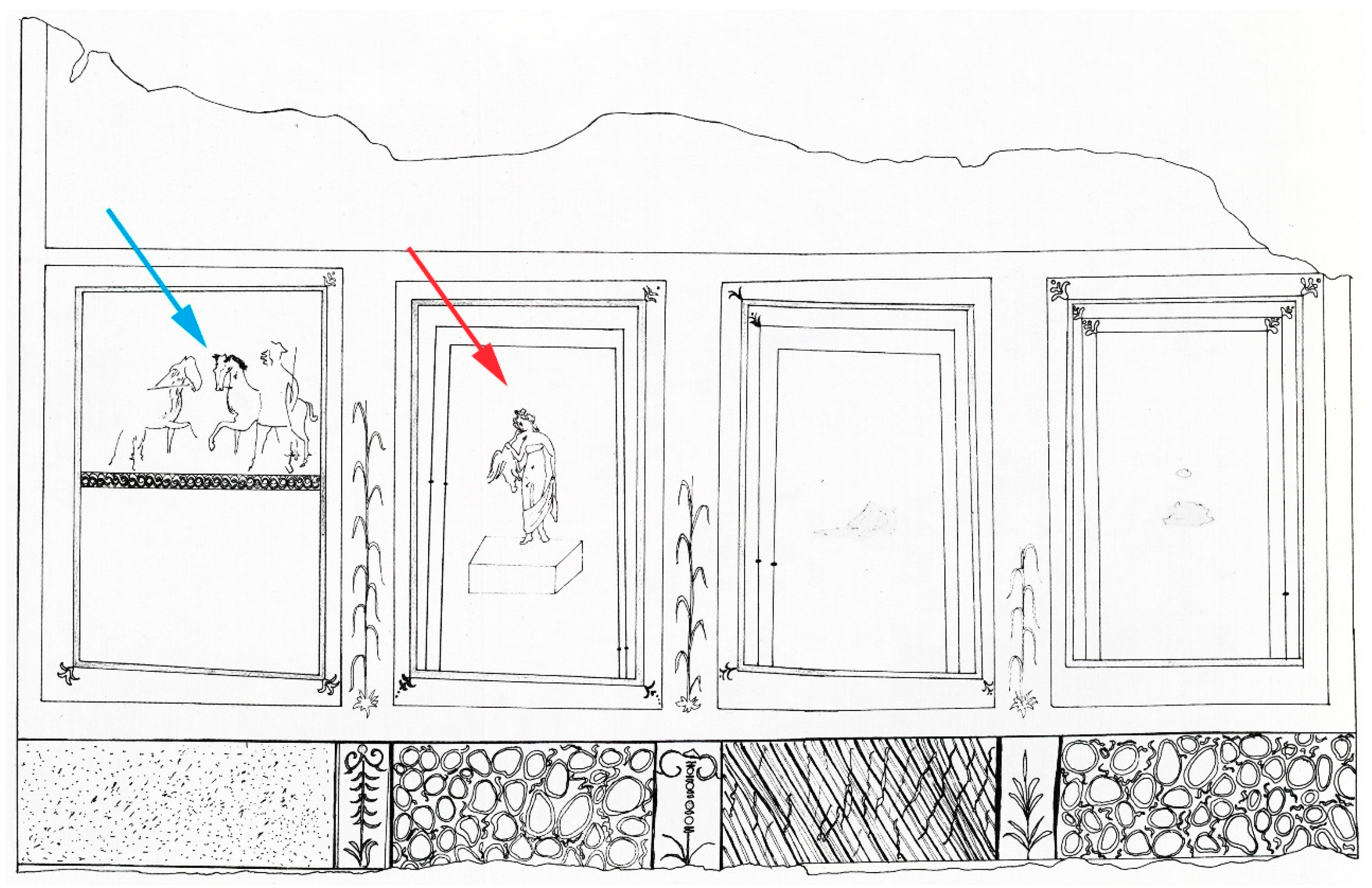

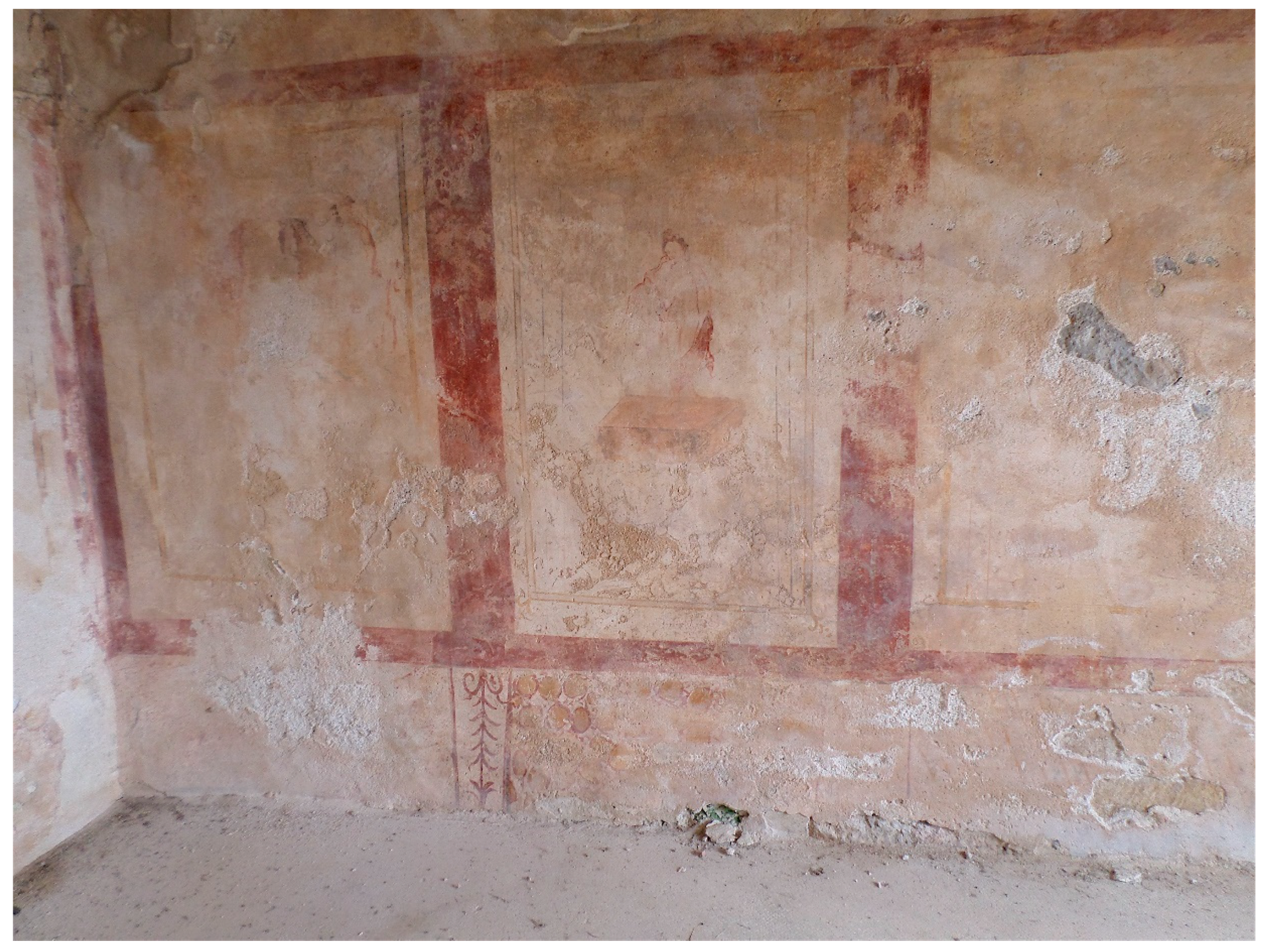

| 13 | (De Vos 1975, p. 200). Layers of First-Style painting can be found below those that are currently visible, including in dining room g, revealing the house went through numerous phases of renovation from the Hellenistic period onwards, a phenomenon documented throughout Soluntum. |

| 14 | Marietta de Vos first proposed that these paintings date to the mid-to-late first century CE based on their similarity to Fourth-Style compositions elsewhere in the Mediterranean (De Vos 1975, p. 202). Elisa Chiara Portale provides a further justification for this dating given the multiple layers of fresco below those currently visible in the House of Leda (Portale 2007b, especially p. 304). For more on wall painting in Sicily in general, see (Mura 2013). |

| 15 | When the distinct phases of a house are visible in the archaeological record, they are often described by scholars as separate entities, or “slices” of time, which seemingly developed without human intervention. However, the framework of renovation, as it is used in this article, allows us to think diachronically about continually occupied spaces such as the houses of Roman-era Sicily. The primary benefit of this approach is that it restores the human element to the architectural evidence, such as viewers who would have experienced the older and newer parts of a domestic ensemble, including those of different media, simultaneously. |

| 16 | Of course, most elite houses in the Roman world would have been “mixed-media” with ensembles that contained mosaics, wall paintings, and more portable artworks or furniture in bronze, woven cloth, etc. The House of Leda is unique because it still preserves many of these decorative elements into the modern day. |

| 17 | For the “model” viewer, see (Valladares 2005). The ideal viewer, for the sake of this article, had the social status and educational background to identify and appreciate Greek and Roman mythological figures, popular statue or iconographic types, and different mosaic and wall painting styles. Although I cannot account for the perspective of every person who would have visited the House of Leda, I aim to capture the majority of them. |

| 18 | All rooms will be referred to by their letter as seen on the plan in Figure 1. |

| 19 | For a comparable border from Morgantina, see (Tsakirgis 1989), especially room 1 of the House of Ganymede, room 12 of the House of the Arched Cistern, and room 10 of the House of the Tuscan Capital. See p. 409 for a discussion of this pattern more generally. Morgantina provides some of the best houses for comparison to those from Soluntum since many of them were constructed or redecorated in the second and early-first centuries BCE. |

| 20 | Preserved fragments of both the columns and the balustrade have allowed for this reconstruction. A similar arrangement was found in the so-called “Gymnasium” house and is illustrated in (Wolf 2003, p. 39). |

| 21 | The precise find spots of the statues are not recorded. This suggestion about the placement of the sculptures in the House of Leda is based on the fact that when Hellenistic-era statues have been found in situ, it is almost always in the most visible or public spaces of a house, such as porticoes, peristyles, and gardens. As an example, see (Nevett 2011). |

| 22 | Two Hellenistic-era examples of this statue type have been found at Delos. While one of the Delian examples has an unknown provenance, the other comes from the House of the Lake, a Hellenistic courtyard house (Trimble 1999, p. 22). |

| 23 | Sicily had very limited sources for marble and thus much of it was likely imported from elsewhere then carved at workshops on the island (Marconi 2013, p. 159). |

| 24 | The original is now housed at the Soluntum Archaeological Museum and a replica stands within room f. |

| 25 | For more on the mosaic, see (Von Boeselager 1983, p. 57; Wilson 1990, p. 120; Tusa Cutroni 1994, pp. 62–63). The date of the mosaic and its origin have sparked much debate about the overall chronology of the House of Leda. Caterina Greco argues that the dating of the house has always been based on the assumption that the mosaic was imported from Alexandria in the second century BCE, even though we do not have definitive proof. See (Greco 1997, pp. 45–47) as well as (Greco 2011). |

| 26 | The Fourth-Style frescoes in dining room g are the only ones that were figural in nature. Those elsewhere in the house were in a palatte of red and white, sometimes with a decorative garland, but not as intricate as the ones in room g. |

| 27 | That these rooms may have served as cubicula (or bedrooms in English, though they were used for more than just sleeping and could operate as small spaces for intimate gatherings) is indicated by the opus sectile thresholds. |

| 28 | Under the Fourth-Style frescoes there is evidence of First-Style wall painting (De Vos 1975, p. 201). |

| 29 | Ibid. For more on replicative media as it relates to trompe l’oeil marble panels like those in the House of Leda, see (McAlpine 2014; Platt 2018b, especially pp. 258–73). More generally, see (Barry 2017, especially pp. 30–35). For the interplay between media in the Roman house see, (Bergmann 2002a, 2002b). |

| 30 | According to one version of the myth, Zeus seduced Leda in the guise of a swan on the same night that she lay with her husband Tyndareus. Leda then gave birth to her twin sons who have different fathers—Castor is the son of Zeus and thusly divine, whereas Pollux, as the son of Tyndareus, is mortal. |

| 31 | For the idea of the “floating figure” in Roman wall painting, see (Valladares 2014). |

| 32 | See (Marconi 2011) for more on “ambiguous” figures who oscillate between a character from Greek myth and a sculpture or representation of said person. For “ambiguous” sculptures see (Squire 2013). Ambiguously living sculptures are also explored in ancient literature, most explicitly in the story of Pygmalion in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which Jas Elsner explores in his book chapter “Viewing and Creativity: Ovid’s Pygmalion as Viewer” (Elsner 2007, pp. 113–31). |

| 33 | The depiction of statues in Roman wall painting has been discussed extensively by (Eric Moormann 1988, 2008). |

| 34 | (Kahil and De Bellefonds 1992, p. 238). The House of the Gilded Cupids (VI.16.7) at Pompeii, where Leda and the swan are painted in two separate rooms (C and R), exemplifies the popularity and particular interest in the myth. Jessica Powers argues that this double depiction within a single residence was intentional and encouraged a viewer to compare the different representations of Leda (Powers 2006, pp. 131–41). |

| 35 | For a recent analysis of the Dioscouri in Greek and Roman art, see (Platt 2018a). |

| 36 | On the replication of sculpture types in the Roman period, see (Bartman 1988, p. 222). |

| 37 | There could have been more than two sculptures in the house but only these two survive. |

| 38 | The limestone sculpture from the House of Leda also finds parallels in the “Arm-Sling” type, which is related to the Small Herculaneum Woman type in its body position. This type takes its name from the way the right arm is bent across the chest and supported by the mantle, appearing to look like a sling (Dillon 2012, p. 91). |

| 39 | Two examples from the second century BCE confirm that the sculpture from Soluntum likely depicts Clio and reveal the popularity of the sculptural type. One is the second-century BCE Apotheosis of Homer Relief, signed by Archelaos of Priene, which depicts the so-called “Muse with a Scroll” i.e., Clio. The other is the Halikarnassos Base, now at the British Museum, dated to 130–120 BCE, which also depicts a “Muse with a Scroll.” For the muses in Greco-Roman sculpture more broadly see, (Marvin 2008). |

| 40 | See (Burlot and Roger 2012). The Muses here are in the same order as in Hesiod’s text, suggesting the viewer was meant to connect the images to their mythological origin story. |

| 41 | (De Vos 1975, p. 201). The pattern of the Carystian marble closely resembles “zebra stripe” patterns that are well-documented in Roman painted ensembles. The “zebra pattern” frescoes have resulted in a number of interpretations from earlier scholars asserting that such a “simple” pattern must be indicative of slave quarters in a house to more recent explanations that the pattern served to mark public reception and circulation spaces. See (Wallace-Hadrill 1994, pp. 39–45) for the former. For the latter, see (Goulet 2001; Laken 2003). |

| 42 | For more on the dialogue between marble and its faux painted equivalents, see (McAlpine 2014). For this phenomenon as related to Second-Style frescoes in the Roman Republic, see (Mulliez 2014). |

| 43 | Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 35.1(3). This is reaffirmed by McAlpine who says “A few streaks or loops of red on yellow could easily be recognized as Numidian marble (McAlpine 2014, p. 198).” |

| 44 | Numidian yellow marble may have been particularly appealing to audiences in Sicily given the island’s close proximity to Africa, and Numidia more specifically. Wilson notes that in the first century CE “readily identifiable” marble from all over the Mediterranean, including Numidian yellow, was imported to the island as paneling for floors and walls (less so for larger architectural elements such as columns). See (Wilson 1990, p. 241) for a complete list of marble types found on Sicily in the first century CE. |

| 45 | (Fant 2007, specifically p. 341). Pliny the Elder records that Numidian yellow marble first arrived in Rome in 78 BCE, when the consul M. Lepidus constructed the lintels of his house from this material (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 35.8). This practice of using exotic marbles in one’s house was initially criticized by many Roman authors at the end of the Late Republic as explored by Marden Nichols (2017). |

| 46 | Colored marbles were not as widely known before Augustus’ conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, after which they became more prominent on the Italian mainland. For the use of colored marble under Augustus, see (Bradley 2006, especially pp. 4–5), as well as (McAlpine 2014, especially chapter six, “Imperial Marble in Pompeian Wall Painting,” pp. 184–203). |

| 47 | For example, see Horace, Odes, 2.18.5 for African marble columns; Seneca the Younger on the use of luxurious marbles including Numidian yellow in public baths (Letters, 86.6–7); Martial on the baths of the freedman Etruscus (Epigrams, 6.42); Statius on the villa of Pollio (Silvae, 2.2.36–106). McAlpine (2014, p. 76) observes that Numidian yellow was especially prevalent in Augustan-era Rome where it made up a column erected at Caesar’s funeral pyre, the paneling in the portico of the Danaids at the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, and the paving in the Forum of Augustus. |

| 48 | Roman authors from the end of the first century CE, such as Statius and Martial, included descriptions of the origin and physical characteristics of colored marble into their writings. Marble “offered contemporary literati a rich opportunity to demonstrate authority and knowledge, and to participate in erudite debate on the aesthetics of empire and the character of Roman imperial culture (Bradley 2006, p. 8).” |

| 49 | Although one might question how cognizant the provincial elite might have been about trends on the Italian mainland, Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (2010, p. 437) explains that “By the end of Augustus’ reign, the new rhythms that characterize the Empire are set. Appetites that have grown in Italy become the hallmark of Roman living, however far from home: already under Augustus, the elite of south Gaul […] decorate their houses with the “third style” fashion of the day…” In other words, in the first century CE decorative trends were exported from Italy to the provinces where local workshops created their own luxury goods from loosely Roman models. |

| 50 | Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 5.2 (“Numidia”). |

| 51 | Martial, Epigrams, 6.42. |

| 52 | For more on how fresco colors and their pigments were associated with elite luxury, see (Nichols 2016). |

| 53 | For an example from Morgantina, see (Tsakirgis 1989, pp. 403–4). |

| 54 | According to De Vos (1975, p. 200), this is one of the only representations of such an instrument anywhere in the ancient world aside from a first-century BCE fresco at Stabiae. |

| 55 | For the mosaics from the House of Ganymede, see (Bell 2011, pp. 105–23). |

| 56 | S. Rebecca Martin (2017, pp. 52–56, 61–66) has shown that Sicily (among other locales, like Delos and Pergamon) played a key role in the development of Hellenistic picture mosaics. |

| 57 | Ovid, Fasti, VI. 277–279. |

| 58 | For more on how artworks and household décor gained value with age, as well as the preservation of older artworks as “heirlooms,” see (McAlpine 2016, pp. 176–77; Powers 2011). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berlin, N. Mixed-Media Domestic Ensembles in Roman Sicily: The House of Leda at Soluntum. Arts 2019, 8, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020062

Berlin N. Mixed-Media Domestic Ensembles in Roman Sicily: The House of Leda at Soluntum. Arts. 2019; 8(2):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerlin, Nicole. 2019. "Mixed-Media Domestic Ensembles in Roman Sicily: The House of Leda at Soluntum" Arts 8, no. 2: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020062

APA StyleBerlin, N. (2019). Mixed-Media Domestic Ensembles in Roman Sicily: The House of Leda at Soluntum. Arts, 8(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020062