The Almohad Caliphate: A Look at Al-Andalus through Arabic Documentation and Their Artistic Manifestations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Interrelation between the Maghreb and Al-Andalus: Material and Documentary Evidence

2.1. The Beginnings of a New Reformist Movement

2.2. The Legitimation of the Almohad Caliphate: The “Memory” of Al-Andalus

To the right of the mihrab stands the pulpit, a work without equal in the whole world. It is made of ebony, box and fragrant wood. The annals of the Umayyad dynasty explain that it took seven whole years to finish it; six teachers were employed there, not counting those who were in their service as laborers; each of these teachers received a daily salary of half mitqāl muhammadī

This pulpit was made with the most extraordinary art, of which its artisans were capable. The richest wood was chosen carved and sculpted, painted and adjusted, according to the rules of art and calculation for it with admirable work and great shape and modeling, inlaid with sandalwood and with ivory and ebony applications, shining like an ember in the fire, and with plates of gold and silver and drawings in its work of pure gold, which shine with light, and takes them, the one who sees them in the dark night, by full moons

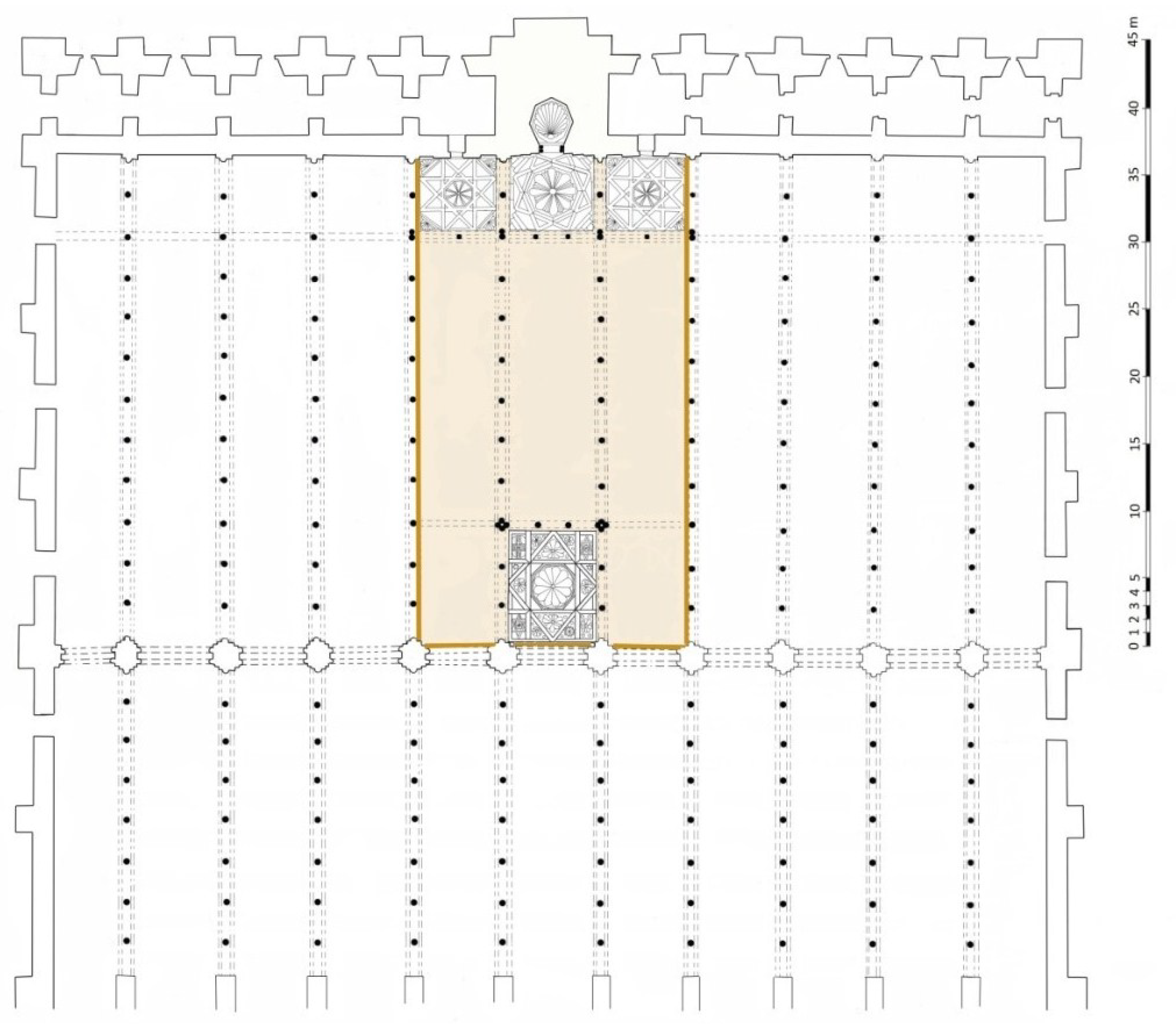

The merit of this maqṣūra is that it was made with a mechanism with which it rose when the caliph would leave the palace and was lowered when he entered. That is, a door was made to the right of the miḥrab, inside which is the almimbar and to its left another door, inside which there is a room, where the mechanisms of the maqṣūra and the almimbar are and by it had ‘Abd al-Mu’mīn’s entrance and exit. When the time to go to the mosque was approaching, on Friday, the mechanisms were set in motion, after removing the tapestries from the site of the maqṣūra and raising their sides at the same time, without exceeding each other in the least. The door of the pulpit (almimbar) was closed, and when the preacher got up to go to it, the door was opened and the pulpit came out with a single thrust of the mechanism and there was no noise or visual trace of the device

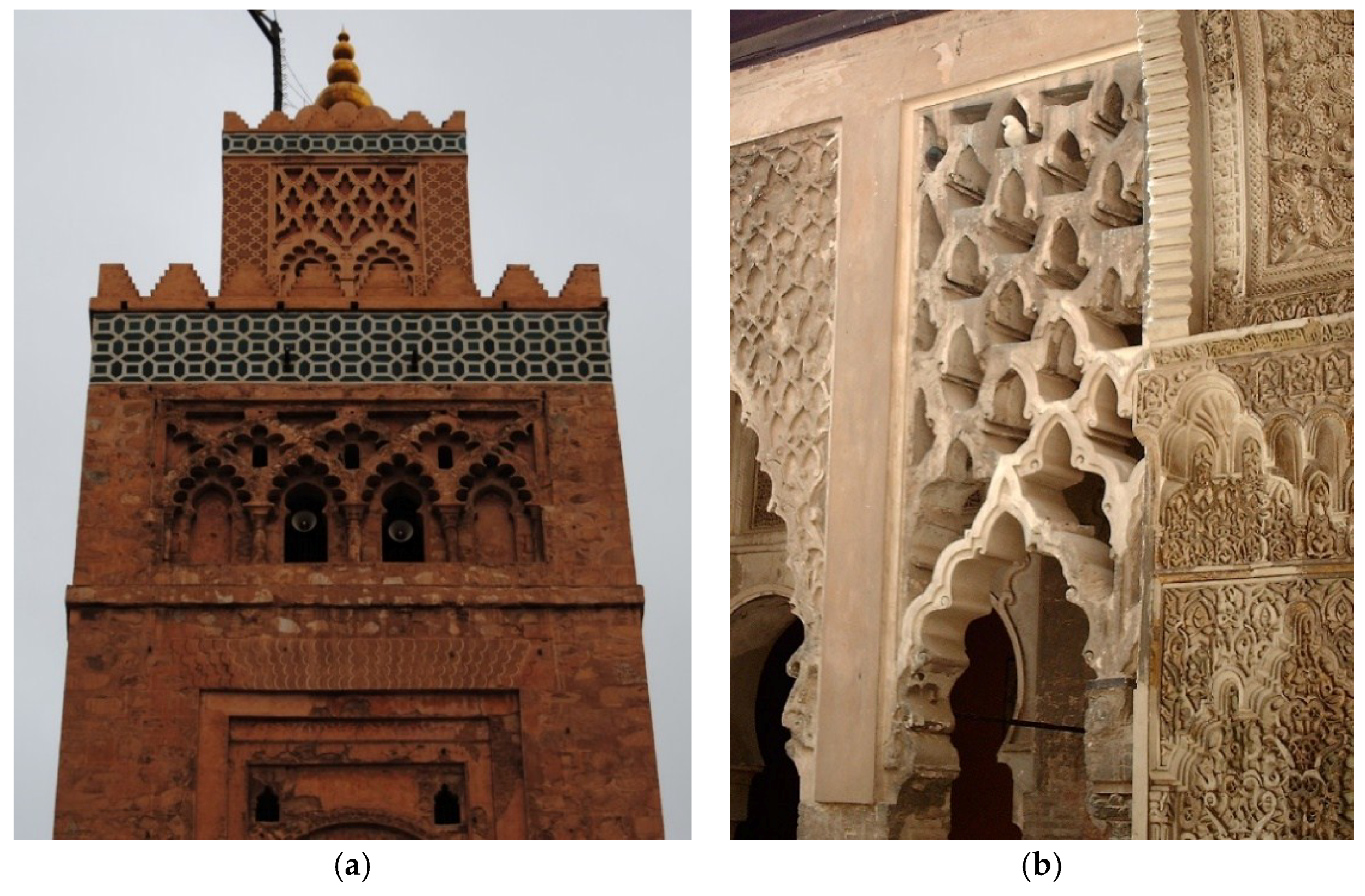

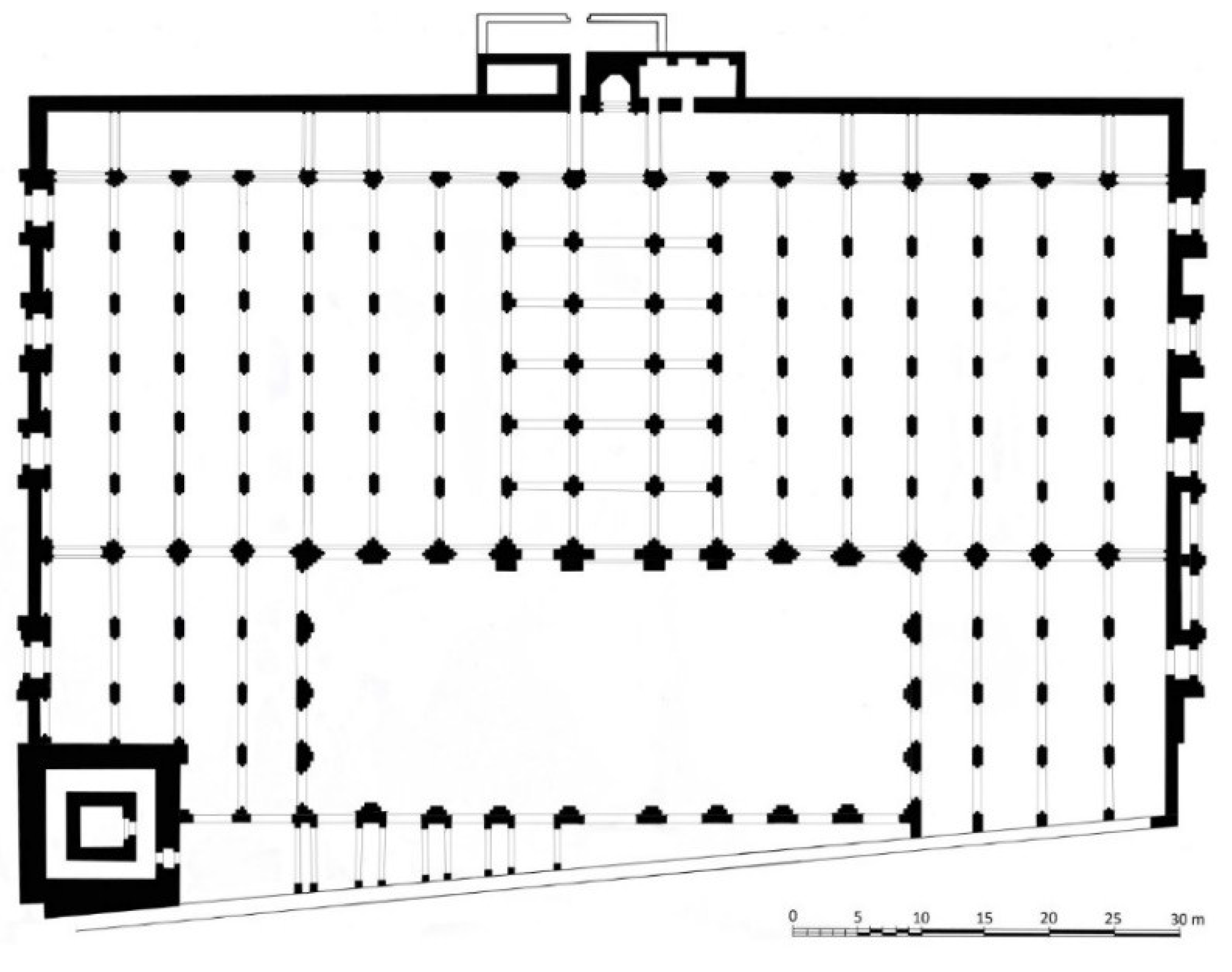

[…] Caliph al-Imama [‘Abd al-Mu’min] built a great mosque there [the Kutubiyya], then he enlarged it equally or greater [than it was before] from his Qibla because it was small, and built its great minaret, as none have been known in Islam and it was finished by his son, the caliph Abū Ya’qūb which Allāh is pleased with

They received the supreme order [to the sayyides] to settle down in Cordova […] to be the seat of government in al-Andalus, as the Banu Umaya were entitled to, since it occupies the center of al-Andalus, and where the functions of the government officials should be fixed on, so that they would be within the reach of those who came from their region

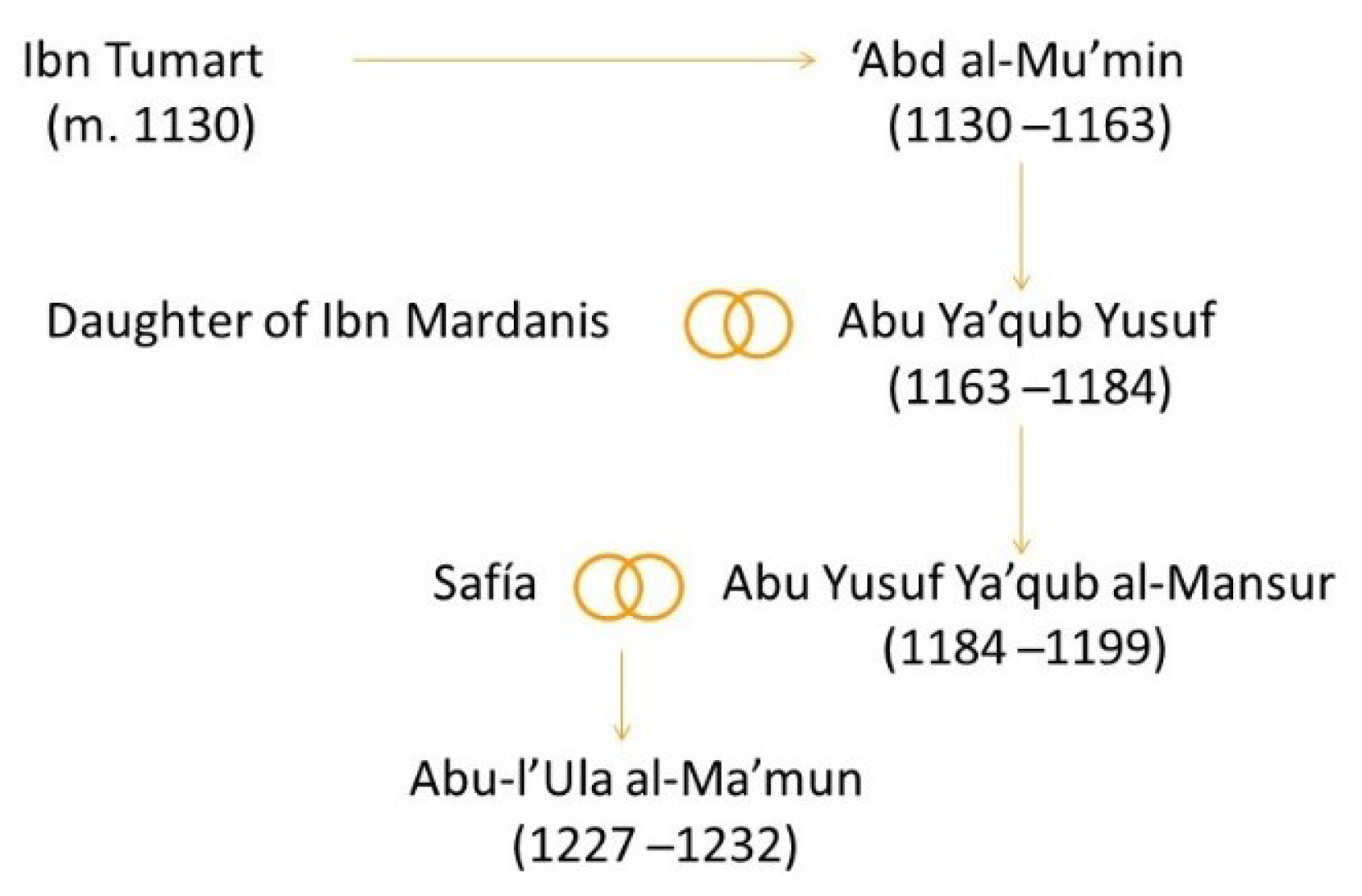

2.3. The Andalusian Legacy in the Political, Artistic and Religious Landscape

Abū-l-’Ulā al-Ma’mūn also wrote with his own hand to all his country about suppressing the name of the Mahdī in the ceca and in the jutba -sermon- […] This is the letter quoted: From the servant of God, Idrīs, Amīr al-Mu’minīn, son of Amīr al-Mu’minīn, grandson of Amīr al-Mu’minīn, the talibes and the notables and the people and those who are with you of the believers and of the Muslims […] What we order is the fear of God and asking Him for help and trust Him; know that we have rejected the false and we have published the truth and that there is no more Mahdī than Jesus, son of Mary […] Our Lord al-Manṣūr -God be pleased with him- had thought to declare what he saw more clearly than us and in replacing for the people the truth that we have restored; but his hope was not successful and his death did not give him time […]

3. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abad Castro, Concepción. 2009. El ‘oratorio’ de al-Ḥakam II en la mezquita de Córdoba. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teorías del Arte (UAM) 21: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud, Soha. 1996. Doctrina de Ibn Tumart. Cuadernos de Historia 65: 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abd al-Wāḥid, al-Marrākušī. 1955. Kitāb al-Mu’ŷib fī taljīṣ ajbār al-Magrib, Lo admirable en el resumen de las noticias del Magrib. Translated by Ambrosio Huici Miranda. Colección de Crónicas Árabes de la Reconquista. Tetuán: Editoria Marroqui. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ḥimyarī. 1963. Kitab al-rawd al-mi’tar. Translated by M. Pilar Maestro González. Valencia: Gráficas Bautista. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. 2007. Una nueva interpretación del patio de la Casa de Contratación del Alcázar de Sevilla. Al-Qanṭara 1: 181–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. 2011. Sistemas constructivos almohades: Estudios de dos bóvedas de arcos entrecruzados. In Actas del Séptimo Congreso Nacional de la Construcción, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, October 26–29. Edited by Santiago Huerta, Ignacio Javier Gil, Silvia García and Miguel Taín. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, vol. I, pp. 45–53. ISBN 9788497283717. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nuwayrī. 1917. Historia de los musulmanes de África, Sicilia y Creta. Translated by Mariano Gaspar Remiro. Granada: Tipografía “El Defensor”, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, Henri, and Terrasse Henri. 2001. Sanctuaires et forteresses almohades. París: Maisonneuve & Larose, ISBN 9782706814983. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Jonhatan M. 1998. The minbar from the Kutubiyya mosque. In The Minbar from the Kutubiyya mosque. Edited by John P. O’Neill and Margaret Donovan. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 2–29. ISBN 9780870998546. [Google Scholar]

- Boruouiba, Rachid. 1982. Ibn Tumart. Alger: Société Nationale d’Édition et de Diffusion. [Google Scholar]

- Buresi, Pascal. 2008. Une relique almohade: l’utilisation du Coran de la Grande Mosquée de Cordoue (attribué à ‘Utmān b. ‘Affān [644–656]). In Lieux de cultes: aires votives, temples, églises, mosques—IXe coloque international sur l’histoire et l’archéologie de l’Afrique du Nord antique et médiévale, Tripoli, 19th–25th February 2005. París: CNRS Editions, pp. 273–80. ISBN 9782271066138. [Google Scholar]

- Buresi, Pascal. 2010. D’une Péninsule à l’autre: Cordoue, ‘Uṯmān (644–656) et les arabes à l’époque almohade (XIIe-XIIIe siècle). Al-Qanṭara 1: 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañero Subiza, Bernabé, and Lasa Gracia Carmelo. 2004. El Salón Dorado de la Aljafería. Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y del Oriente Próximo, ISBN 8495736349. [Google Scholar]

- Chronique des almohades et des hafçides attribuée a Zerkechi. 1895. Edmond Fagnan, trans. Constantine: Imprimerie Adolphe Braham.

- Codera y Zaidín, Francisco. 2004. Decadencia y desaparición de los almorávides en España. Edited by Mª Jesús Viguera Molíns. Pamplona: Urgoiti Editores, ISBN 9788493339821. First published 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Dessus Lamare, Alfred. 1938. Le Muṣḥaf de la Mosquée de Cordoue et son mobilier mécanique. Journal Asiatique 230: 551–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1986. The Mosque of Tinmal (Morocco) and Some New Aspects of Islamic Architectural typology. London: British Academy, ISBN 0856725684. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian, and Wisshak Jens-Peter. 1984. Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee. Lfg.2, die Mosche von Tinmal (Marokko). Edited by Phillip Von Zabern. Madrider Beiträge: Main-sur-le-Rhin. [Google Scholar]

- Ferre de Merlo, Luis. 2000. Bóvedas nevadas en el castillo de Villena (Alicante). In Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción, Sevilla, 26th–28th October. Edited by Amparo Graciani, Santiago Huerta, Enrique Rabasa and Miguel Ángel Tabales. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, pp. 303–7. ISBN 8495365545. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro Bello, Maribel. 2005. Doctrina y práctica jurídicas bajo los almohades. In Los almohades: problemas y perspectivas. Edited by Patrice Cressier, Maribel Fierro and Luis Molina. Madrid: CSIC, vol. II, pp. 895–935. ISBN 9788400083939. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro Bello, Maribel. 2009. Algunas reflexiones sobre el poder itinerante almohade. e-Spania. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/18653?&id=18653&lang=fr (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Huici Miranda, Ambrosio. 1949. La leyenda y la historia en los orígenes del Imperio Almohade. Al-Andalus 2: 339–76. [Google Scholar]

- Huici Miranda, Ambrosio. 2000. Historia política del Imperio Almohade. Granada: Universidad de Granada, vol. I, ISBN 9788433826602. First published 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥulal al-mawšiyya, Crónica árabe de las dinastías almorávide, almohade y benimerín. 1952. Ambrosio Huici Miranda, trans. Colección de Crónicas Árabes de la Reconquista. Tetuán: Editoria Marroqui, vol. I.

- Ibn, ‘Iḏārī. 1901–1904. Histoire de l’Afrique et de l’Espagne, intitulée Al-Bayano’l-Mogrib. Translated by Edmond Fagnan. Argel: Imprimerie orientale P. Fontanta et cie., vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, ‘Iḏārī. 1953–1954. Al-Bayān almugrib fī ijtiṣār ajbār mulūk al-Andalus wa-l-Magrib por Ibn ‘Iḏārī al-Marrākušī. Los Almohades. Translated by Ambrosio Huici Miranda. Colección de Crónicas Árabes de la Reconquista. Tetuán: Editoria Marroqui, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, ‘Iḏārī. 1963. Al-Bayan al-mugrib. Nuevos fragmentos almorávides y almohades. Translated by Miranda Ambrosio Huici. Valencia: Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de Zaragoza, Aragón y Rioja. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, AbīZar’. 1964. Rawḍ al-qirṭās. Translated by Ambrosio Huici Miranda. Valencia: Anubar, vol. II. First published 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, al-Aṯīr. 1898. Al-Kāmil fī l-ta’rīj, Annales du Maghreb et de l’Espagne. Translated by Edmond Fagnan. Alger: Typographie Adolphe Jourdan. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, Ṣāḥib al-Salā. 1969. Al-Mann bil-imāma (Historia del Califato Almohade). Translated by Ambrosio Huici Miranda. Anubar: Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Martín, Alfonso. 2000. La explanada de Ibn Jaldún. Espacios civiles y religiosos de la Sevilla almohade. In Sevilla 1248. Congreso Internacional Conmemorativo del 750 Aniversario de la Conquista de la Ciudad de Sevilla por Fernando III, Rey de Castilla y León, Seville 23rd–27th November 1998. Coordinated by Manuel González Jiménez. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Ramón Areces, pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kitāb, al-Ansāb. 1928. Extraits du Kitāb al-Ansāb fī ma’rifat al-aṣhāb, ‘Le Livre des Généalogies pour la connaissance des Compagnons’ du mahdī Ibn Tūmart. In Documents inédits d’histoire almohade. Edited and Traslated by Evariste Lévi-Provençal. París: Paul Geuthner, pp. 18–49 (ed.), 25–74 (trans.). [Google Scholar]

- Le Livre de Mohammed Ibn Toumert, Mahdi des Almohades. 2010. Introduced by I. Goldziher. Montana: Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 9781168154804. First published 1903.

- Lettres d’Ibn Tūmart et de ‘Abd al-Mu’mīn. 1928, In Documents inédits d’histoire almohade. Edited and Traslated by Evariste Lévi-Provençal. París: Paul Geuthner, pp. 1–13 (ed.), 1–21 (trans.).

- Lévi-Provençal, Evariste. 1928. Ibn Tūmart et ‘Abd al-Mu’min. Le ‘faḳīh du Sūs’ et le ‘flambeau des Almohades. In Mémorial Henri Basset: Nouvelles études nord-africaines et orientales. París: Paul Geuthner, vol. II, pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Lorca, Andrés. 2004. La reforma almohade: del impulso religioso a la política ilustrada. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma 17: 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, Henri. 1928. La profession de foi (‘aqîda) et les guides spirituels (morchida) du mahdi Ibn Toumart. In Mémorial Henri Basset: nouvelles études nord-africaines et orientales. París: Paul Geuthner, vol. II, pp. 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Meunié, Jaques. 1952. La première mosquée almohade de Marrakech. In Recherches archéologiques à Marrakech. París: Arts et métiers graphiques, pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Millet, René. 1923. Les Almohades. Histoire d’une dynastie berbére. París: Société d’éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Tilman. 1997. La destrucción de la ciencia de la sari’a por Muhammad b. Tumart. Al-Qanṭara 2: 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2005. Siyāsa. Estudio arqueológico del despoblado andalusí (ss. XI–XIII). Murcia: Excmo, Ayuntamiento de Cieza (Murcia). ISBN 8492065354. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Cumplido, Manuel. 2008. La catedral de Córdoba. Córdoba: Cajasur, ISBN 9788479596521. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser-Owen, Mariam. 2014. Andalusi Spolia in Medieval Morocco: Architectural Politics, Political Architecture. Medieval Encounters 20: 152–98. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, Omar. 1984. The unification of the Maghrib under the Almohads. In Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century, General History of Africa, IV. Edited by Joseph Ki-Zerbo and Djibril Tamsir Niane. California: UNESCO, pp. 13–56. ISBN 9780852550946. [Google Scholar]

- Un recueil des lettres officielles almohades. Étude diplomatique analyse et commentaire historique. 1942. Evariste Lé vi-Provençal, trans. París: Librairie Larose.

- Valor Piechotta, Magdalena. 2008. Sevilla Almohade. Málaga: Sarriá, ISBN 9788496799141. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera Molins, MªJesús. 1992. Los reinos de taifas y las invasiones magrebíes. (Al-Andalus del XI al XIII). Madrid: Fundación MAPFRE, ISBN 8471004313. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera Molins, Mª Jesús. 1998. La ciudad almohade de Sevilla. In VIII Centenario de la Giralda (1198–1998), Seville, 9th–13rd Mars 1998. Cordova: Cajasur, pp. 15–30. ISBN 9788479592295. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba Sola, Dolores. 2015. La senda de los almohades. Arquitectura y patrimonio. Granada: Universidad de Granada, ISBN 9788433857767. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | On the biographies of Ibn Tūmart and ‘Abd al-Mu’mīn see the studies carried out by Lévi-Provençal (1928) and Boruouiba (1982). |

| 3 | I would like to thank Professor Concepción Abad Castro for all the observations and comments made in this regard. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | On this point, see also (Huici Miranda [1956] 2000, vol. II, pp. 476–77). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Cavero, I. The Almohad Caliphate: A Look at Al-Andalus through Arabic Documentation and Their Artistic Manifestations. Arts 2018, 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7030033

González Cavero I. The Almohad Caliphate: A Look at Al-Andalus through Arabic Documentation and Their Artistic Manifestations. Arts. 2018; 7(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Cavero, Ignacio. 2018. "The Almohad Caliphate: A Look at Al-Andalus through Arabic Documentation and Their Artistic Manifestations" Arts 7, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7030033

APA StyleGonzález Cavero, I. (2018). The Almohad Caliphate: A Look at Al-Andalus through Arabic Documentation and Their Artistic Manifestations. Arts, 7(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7030033