Abstract

This article aims to approach the Mudejar architecture developed in Mexico during the 16th and 17th centuries. The subject has been little studied, although both general and specific contributions have been made by the author’s research group. At the methodological level, this study is based on the existing bibliography, as well as archive and field research which allow for an accurate scientific approach and results. The article analyzes the social and productive conditions in Mexico during the Viceregal period, along with the systematization carried by the Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, the guild ordinances and the architectural typologies. The perception of territory and the use of constructive models by the Viceregal authorities would justify the use of the Mudejar style as cultural and unity criteria.

1. Introduction

In our geographical ambit, the Modern era is marked by the cultural encounter between the Old and the New World after the discovery of America; for our culture, this contact could be seen as a continuation of the encounter that the Christian kingdoms had, from the Late Middle Age until the conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, with the Islamic States of Southern Spain.

In regards to the studied territory, we must point out that the fall of the Aztec Empire in 1521 has radically changed the perception and conditions of the Spanish occupation of America. The precarious situation of the insular Caribbean cultures differed from the Mesoamerican reality since the latter was structured as a state, which possessed different crafts-related institutions and highly technological construction knowledge. In addition, the Spanish monarchy imposed strict regulations, both urban and architectural, managed by the local councils and, ultimately, by the viceroys.

2. Production System and Ordinances

In the inherited prehispanic society, there were numerous masters in the different construction crafts, who since the beginning would become the base for any creations made by the Spaniards. Their well-known importance is essential since the qualified Spanish masters would not have arrived until approximately 1550, with important exceptions such as Toribio de Alcaraz, who worked in the utopian project of Don Vasco de Quiroga in Pátzcuaro (Michoacán)

These indigenous masters not only became proficient in adapting a series of techniques to the needs demanded by the Spaniards, but also had a deep knowledge of the indigenous building materials, that is, the constructive possibilities, resistance and mechanical characteristics of the native tree species. The adaptable workforce, the ligneous richness of the area and the constructive necessities made carpentry essential for the new urban definition of the territory. Thus, the systems that we can qualify as strictly Mudejar were developed according to the importance of the building and the needs of the clients.

Thatched roofs and poles were used in the initial buildings, both religious and civil; however, they were slowly replaced by rubble walling and collar-beam covers. The civil constructions, initially built with adobe, adopted the quarrying or bricklaying as the new construction techniques; moreover, the single-storey structures were replaced by multi-storey buildings which had alfarjes as supporting elements of the covers.

Having said that, all the constructive work was controlled by the guilds; these institutions of medieval origin were transferred to America where they were settled into the most important cities of the viceroyalties. As far as our study is concerned, the guilds established in the capital and in Puebla de los Ángeles were exceptionally well organized.

The functioning and guild regulations were included in the City Ordinances; these were the legal corpus that allowed both use and mercantile activities. These ordinances did not have an irrevocable nature; they could be reformed and new concepts or trades could be added. Their content was beyond the internal organization of the guilds; they ruled, with absolute precision, all the details concerning the government of the city, acting, simultaneously, as the legal framework.

Since the mid-15th century, the guild activities and the ordinances of the cities of the kingdoms of Spain were practically homogeneous; the new legislation created by the Catholic Monarchs in 1495, “Primer Proyecto de Ordenanzas Generales para Castilla”, would contribute to the uniformity of the legislation.

Hence, when the American documents were analyzed the concomitance and reflection of the ordinances on this side of the Atlantic were noticeable; particularly, the regulation from the Andalusian area (Seville and Granada). For instance, the definition that the Sevillian masonry guild gave of the construction of a temple: “…que sepa el dicho maestro edificar una Iglesia de tres naves con su Capilla principal … y a la Capilla, segun conviene, assi de madera como, como de cruzería” (Ordenanzas de Sevilla 1975, Fol. 150 r.) is the description of a late medieval or 16th century Sevillian church. A similar text can be found in the masonry guilds (Bonilla 1998) of Mexico and Puebla de los Ángeles (Guzmán 2005). As a result of these common regulations, churches such as Santa Marina in Seville and the church of San Francisco de Asis in Zacatlán de las Manzanas (State of Puebla) share strikingly similar spatial schemes, despite being in two different continents.

Although there are similar constructive instructions in the ordinances, differences can be traced in the American regulations. Thus, a bricklayer was allowed to build “French chimneys”1, a typology that can be found in the ordinances of Granada, but not in the Sevillian documents; the American regulations also included activities such as the creation of “city plants” (Calvo 2011), a labor only reserved for a mason of the primo, a prerogative absent in both Granada and Seville regulations.

We consider that it is important to address the ethnic issue through analysis of the guild documents. In Granada, each guild was formed of two groups: old Christians and Moriscos2. In Seville no Moorish apprentice could be part of a workshop since he should be: “christiano, y de linage de christianos limpio…” (Ordenanzas de Sevilla 1975, Fols. 147 v.–148 r.). The black population and slaves could labor only as workforce, but they could not be journeymen, since they were not allowed to follow the standard examination process: “…no pueda ser examinado del dicho oficio ni poner tienda del dicho oficio en la calle de los carpinteros desta cibdad, porque estos a tales no es honra de los dichos oficiales que entren con ellos en sus cabildos, y ayuntamientos” (Ordenanzas de Sevilla 1975, Fol. 148 r.). Mexican ordinances shared several parallelisms with Sevillian regulations, since neither the black population nor slaves could be examined, although they could reach officer grade by learning in a workshop (Maquívar 1999). Moreover, in New Spain there was an additional and unique group: the native population. The Mexican ordinances stated: “Mandamos que los indios de esta ciudad, sean examinados…” (Maquívar 1999), that is, they could be masters and own workshops, although it is not clear if they were examined by guilds’ alarifes (master builders) or if they could reach positions of responsibility in the guild and in the municipal council. We should not forget that, as we previously mentioned, before the Spanish arrival the native population had mastered different construction techniques and had their own systems of organization. For instance, in the minutes of the Council of Tlaxcala the following names relating to construction occupations are specified: tetzonzonque (stonemasons), texima (stoneworkers), cuauhxima (carpenters) (Solis et al. 1984).

In Mexico, carvers were part of the carpenters’ guild until 1589 when they funded an independent guild. In 1568 the first ordinances praised their work: “En lo que toca al oficio de los entalladores, por ser como son adornadores del Credo Divino, hay muy gran necesidad particularmente de los miembros de ella, con lo que tocare a los cinco géneros que son: toscano, dórico, jónico, corintio y composito; asimismo ha de ser examinado de la talla y de la escultura, tomando razón de cada cosa por práctica y teórica y demostración para que en todo en lo que está facultado, quedare examinado…” (Maquívar 1999). The need to endow churches with altarpieces is the main reason behind the creation of the carvers’ guild in 1589; in these ordinances the native population were allowed to carve religious sculptures without being examined, the only prohibition was that the masters could not buy works from the natives and sell them as their own.

In summary, despite the unified and generic content of both Peninsular and American ordinances, there were adapted to each territorial reality.

In the course of our research we found a subject that might be interesting to analyze: the examination process of a carpenter in Puebla de los Ángeles in 1641. Agustín de Prado, son of the deceased master Joan Gomes Melgarejo, had a serious sight condition that made him completely blind; although initially this might be considered a hindrance to practice his craft, the examination process proved otherwise: “…y porque el susodicho es siego de la bista corporal y por el tacto suple el defecto de la bista y obra en su ministerio como si la tuviera en un vanco, una mesa y un caxón, y para poderle dar carta de exsamen pidieron a los dichos jueses bean por vista de ojos obrar al dicho Agustín de Prado, y para ello los dichos juezes diputados, por ante mi el escribano fueron a la casa de la morada del susodicho, y estando en ella el dicho Agustín de Prado tomó una tabla y le echó sus junteras a sepillo y labró a boca de asuela como diestro ofisial, lo qual pasó en presençia de mi el escrivano y de los dichos juezes de que da fe, y los dichos alcalde y vehedor juraron a Dios y a la cruz que el susodicho es ávil y sufiçiente, y como a tal se le puede mandar dar carta de exsamen para que pueda tener tienda pública, con ofiçiales y aprendiçes del dicho Agustín de Prado, siego de la vista corporal, natural desta çiudad, de hedad de veinte y çinco años, y los dichos jueses lo ubieron exsaminado y mandaron que como tal maestro use y exerze (sic) el dicho oficio en todos los casos y cosas que le tocan…” (Examen de carpintero de Agustín de Prado 1641).

Although there has been a detailed and copious historiographical debate on the acceptance of natives and mestizos we had not encountered with a similar situation, a disable person, who despite his condition, passed the examination.

3. Don Antonio de Mendoza and the “Traza Moderada”

A key figure in the transformations that took place in Mesoamerica is Don Antonio de Mendoza; he was the first Viceroy of New Spain, being appointed in 1535. Upon his arrival in Mexico he perceived the colonization through a disorganized, though effective, process based on the presence of the mendicant orders. Mendoza was aware of the Modern state definition developed by the Catholic Monarchs and later by Charles V. Territorial and religious unity had clear artistic manifestations; first the use of Late Gothic style during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella and later by following the classical unified style imposed by the Emperor.

In New Spain religious architecture, the most frequent type until that moment, aimed to repeat Spanish traditional models, particularly Sevillan. Before Mendoza’s arrival the prototypical construction system was overseen by managers who were more concerned with the spiritual aspects of it rather than the technical and constructive practices, of which they were largely unaware. Moreover, the indigenous workforce was used to work in their traditional style and methods and the construction procedure was not supervised by any Spanish master.

To address these issues Antonio de Mendoza applied in the new created viceroyalty the above-mentioned policy of definition and endowment. He established the traza moderada (moderate design) aiming to avoid the excesses of luxury that was the cause of the abusive conditions towards the native population, as well as to serve as reference for those constructions that lacked qualified masters. In this sense, the memorandum that Mendoza left to his successor is quite enlightening: “En lo que toca a edificios de monasterios y obras públicas, ha habido grandes yerros, porque ni en las trazas ni en las demás no se hacía lo que convenía, por no tener quien los entendiese, ni supiese dar orden en ello. Para remedio desto, con los religiosos de San Francisco y San Agustín concerté una manera de traza moderada, y conforme a ella se hacen todas las casas” (Instrucciones que los virreyes de Nueva España dejaron a sus sucesores 1987).

Although the model proposed by the traza moderada is not known, it is plausible that it was based on the following design: a church with a rectangular nave without side chapels with a presbytery that would be separated from the other spaces by an arch. The design of the cover would depend on the funds; although it is common to find Mudejar roof framings in the nave and masonry roofs in the presbytery. The cloister would gather the traditional conventual spaces (refectory, chapter house, cells and other rooms). All these spaces would be included in a large atrium along with (if needed) open chapels and posa chapels.

The use of the traza moderada had a double significance; on the one hand it allowed the different religious orders to follow a master design; until that moment the projects were based on improvisations and the distant memory of Spanish architectural designs. On the other, it granted visual uniformity to the constructions and, therefore, to the viceregal territories, a concept that emphasized the idea of these territories as a part of the Spanish state (Aranda 1979; Henares and Guzmán 1989)3. The functionality of this proposal would depend on the still timid development of the guilds and the skills of the newly arrived Spanish masters.

4. Spaces and Carpentry

As we mentioned earlier, the indigenous technology, guild regulations and initial projects of the mendicant orders combined with the implementation of the traza moderada helped to develop New Spain’s architecture during the second half of the 16th century and the 17th century. The outcomes of these elements combined allow us to theorize, catalogue and classify these structures.

The social order, without being a perfectly structured estate, prevented the development of completed ecclesiastical designs. The lack of brotherhoods, nobility and guilds in most of the towns resulted in the absence of side chapels in the majority of the temples. Thus, these spaces are defined by a single-nave plan with a differentiated structural or ornamental chevet. Three-nave churches, of which we will speak later, are rare, and Latin cross-plan churches are almost non-existent. The case of the church of San Mateo de Calpulalpan de Méndez (State of Oaxaca) is exceptional.

The rubblework walls without buttresses, unnecessary since the roofs were made of wood, made later interventions possible, particularly in the Baroque period when new chapels were created. Occasionally these chapels had detailed designs and complex Latin cross-plans to such an extent that they could be considered churches per se, such as San Francisco of Tlaxcala (State of Puebla).

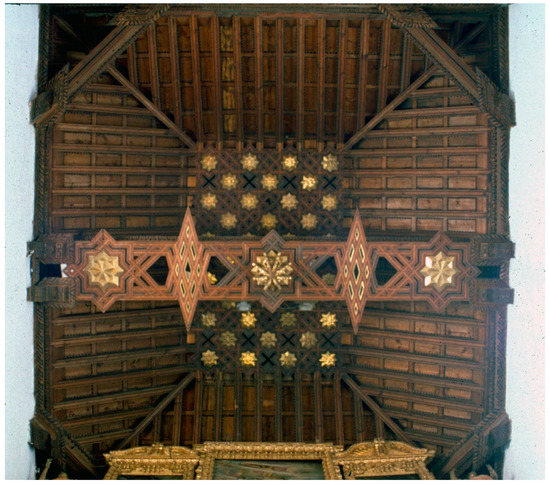

The roof structures respond to the typical Mudejar typologies, from the armadura de limas4 to the alfarjes, the simplest and most common type. There are few remaining examples of the former, for instance San Francisco in Tlaxcala and San Diego in Huejotzingo (State of Puebla) (Figure 1 and Figure 2); however, the extensive documentation and various engravings, kept in different archives, bear testament of the complex architectural solutions that nowadays are not noticeable.

Figure 1.

Main chapel’s ceiling of San Francisco church. Tlaxcala. Photo took by author.

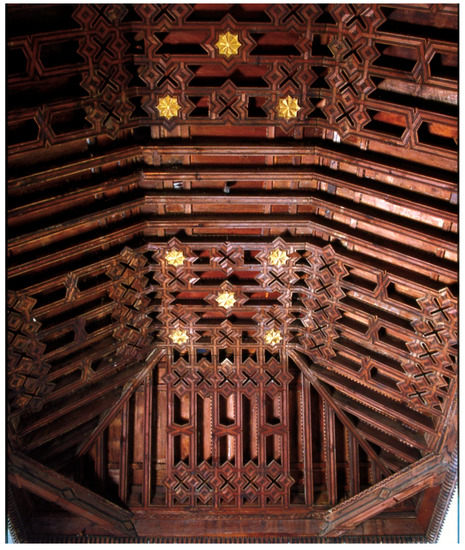

Figure 2.

Sacristy ceiling of San Diego church. Huejotzingo. Photo took by author.

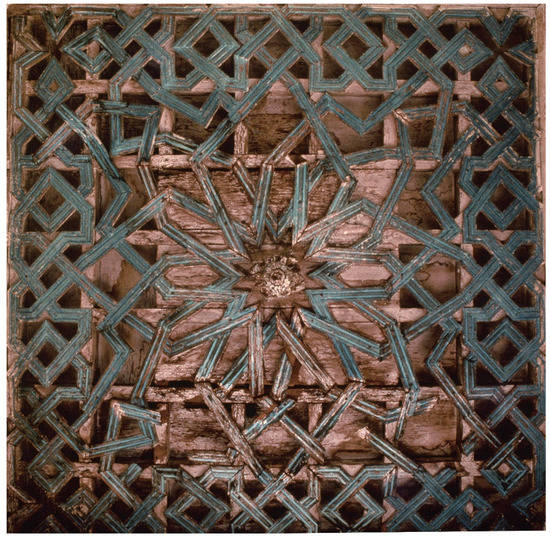

The decorative complexity of the choirs’ alfarjes varies from the rigorous Mudejar scheme of San Francisco in Tlaxcala to the almost sculptural approaches of the Santos Reyes de Atlatlahucan (State of Morelos).

The open chapels were also spaces suitable for experimenting with the shape and structure of the roof; as a result of these imaginative processes the alfarjes of San Esteban Tizatlán (Tlaxcala) and the roof of the open chapel in the Hospital of Tzintzuntzan (State of Michoacán) were built.

The cloister structure was conditioned by the use of carpentry; it was a key element for the development of the style. The thrust system and sustentation force of the alfarjes made possible lighter closures which allowed the use of Renaissance arcades instead of the robust buttresses and the dimmed lights that ogival solutions provided. Additionally, the creation in the cloisters of decorative patterns located in the corners was possible since Renaissance coffered ceilings were employed; perfect examples of this technique are the convents of San Juan Bautista of Coyoacán (Mexico City) (Figure 3), Santos Apóstoles Felipe y Santiago of Azcapotzalco (Mexico City) or the convent galleries of Tzintzuntzan (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Cloister chapel’s ceiling of San Juan Bautista de Coyoacán convent. Mexico City. Photo took by author.

Figure 4.

Cloister chapel’s ceiling of Santa Ana convent. Tzintzuntzan. Photo took by author.

There are few examples of civil architecture of this era that remain intact, although it is known that alfarjes and studs were common in the forest territories of New Spain. We know that Hernán Cortés felled the forests around Mexico for building his household in the Plaza Mayor, which lead us to think about the widespread use of galleries and alfarjes using this material. An example of this can be seen in the transformed, but still interesting, palace of the conquistador in Cuernavaca (State of Morelos) where the alfarjes appear in galleries and halls (Olmos 1975). It should be noted that for building Casas Nuevas de Cortés in Plaza de México, in which native workers from Coyoacán were involved, 600 cedar beams and 15,200 planks were used (Kubler 1982).

The construction system that we can see today, although modified, in the City of Tlaxcala (Toussaint 1983), represents the generalization of the alfarjes in civil spaces that, unfortunately, have disappeared due to deterioration or taste changes throughout history.

Funding

This research was funded by Andalucía y América: Patrimonio Cultural y Relaciones Artísticas (HUM-806).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aranda, Antonio Garrido. 1979. Organización de la iglesia en el reino de granada y su proyección en Indias. Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos, ISBN 978-8400045999. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Juan Benito. 1983. Capillas abiertas aisladas de México. Mexico City: UNAM, p. 23. ISBN 968580401X. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, José Antonio Terán. 1998. Los gremios de albañiles y Nueva España. Imafronte 12: 341–56. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, María del Carmen Olvera. 2011. Los sistemas constructivos en las “Ordenanzas de albañiles de la ciudad de México de 1599”. Un acercamiento. Boletín de monumentos históricos 22: 16. [Google Scholar]

- Enero, 6. Examen de carpintero de Agustín de Prado. Expediente sobre artesanos. 1641. Tomo 220 (1721–1821). Mexico City: Archivo del Ayuntamiento de la Ciudad de Puebla.

- Guzmán, Rafael J. López. 1992. Arquitectura y carpintería mudéjar en nueva España. Mexico City: Azabache, pp. 148–52. ISBN 9686084541. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, Rafael López. 2005. Arquitectura mudéjar. del sincretismo medieval a las alternativas hispanoamericanas. Madrid: Cátedra, p. 75. ISBN 9788437618012. [Google Scholar]

- Henares Cuéllar, Ignacio, and Rafael López Guzmán. 1989. Arquitectura mudéjar granadina. Granada: Caja de Ahorros, ISBN 845059006X. [Google Scholar]

- Instrucciones que los virreyes de Nueva España dejaron a sus sucesores. 1987. Mexico City: Imprenta Imperial, pp. 225–41.

- Kubler, George. 1982. Arquitectura mexicana del siglo XVI. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, pp. 197, 342–43. ISBN 6071642647. [Google Scholar]

- Maquívar, María del Consuelo. 1999. El imaginero novohispano y su obra. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, pp. 138–39, 142. ISBN 9789682951763. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos, Carlos Chanfón. 1975. El Castillo-Palacio de don hernando cortés. Mexico City: Ed. Churubusco. [Google Scholar]

- Ordenanzas de Sevilla. 1975. Sevilla: OTAISA.

- Solis, Eustaquio Celestino, Valencia Armando, and Medina Constantino. 1984. Actas de cabildo de Tiaxcala1547–1567. Mexico City: Archivo General de la Nación, Instituto Tlaxcalteca de la cultura y CIESAS, p. 32. ISBN 9688052256. [Google Scholar]

- Spínola, Gloria Espinosa. 1999. Arquitectura de la conversión y evangelización en la España Nueva España durante el siglo XVI. Almeria: Universidad, p. 173. ISBN 8482401874. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, Manuel. 1983. Arte colonial en México. Mexico City: UNAM, p. 63. ISBN 9688370363. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Hearths built to provide warmth, not for cooking purposes. |

| 2 | Every two years the guild elected four new Christian members and four Moriscos members. From these eight new members the municipal council elected two new Christians and two Moriscos members to hold public office. |

| 3 | In this sense, the process is similar to the one that took place in Granada after its conquest in 1492. |

| 4 | Since we could not find a proper English translation for this technique, we have opted for the Spanish term. It could be defined as a hipped roof which corners are joined together by one or two beams. The diagonal beam is called “lima”. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).