1. Introduction

The ataurique decoration is a type of vegetal ornamentation particularly characteristic of the Western Umayyad world. It is not limited exclusively to vegetal motifs decorating different surfaces, but is based on the creation of harmonious designs derived from the abstraction of elements found in nature. Thus, leaves, flowers, palmettes, and others are organised in unique compositions, in semantic coherence with their names.

The Spanish word “ataurique” is proposed, due to its etymology, as the term of greatest precision to designate this type of decoration, in preference to the more general “arabesque”. Ataurique comes from the Arabic

tawrīq, meaning “to create leaves” or “to grow branches”, referring to the originality of both the compositions and nature itself. This denomination is commonly used to define decorations carved in limestone, although examples exist of numerous materials decorated with such motifs, including marble, plaster, ivory, wood, and even painted walls (see

Figure 1).

Ataurique has been understood as a symbol of Umayyad Córdoba due to its wide dispersal quality, and ornamental richness, being present in some of the most emblematic monuments and objects of the period. This has led to numerous studies that have helped enrich our understanding of this type of decoration. Although a comprehensive study offering a holistic view of on the implications of ataurique has yet to be published, analyses of specific certain forms, monuments, and ensembles have established its position as a principal element in Umayyad plastic arts, granting it, a priori, a representative character.

Indeed, its presence in Umayyad (especially caliphal) architecture has led many to consider this decoration as an ornamental language

1, especially when executed in stone. While small ataurique ensembles have emerged from various excavations in Córdoba, at some sites, the volume of material found has generated studies addressing the questions of influences, meaning or the interpretation of small decorative groups.

The Umayyad Mosque of Córdoba stands as the most emblematic example, a building that has, since its construction, represented part of the city’s identity. Here, ataurique decoration in stone has formed part of the monument since the emirate, as can be seen in the Puerta de San Esteban (one of few remnants of emirate-period ataurique still to be found), studied by

Torres Balbás (

1947;

1957, pp. 356–61;

1960, pp. 36–40) and

Gómez Moreno (

1951, pp. 58–59), and more recently by

Marfil Ruiz (

2009), and recently restored. The doors leading into the prayer hall bore similar decoration. Nonetheless, the passage of time and the restorations carried out have affected the original programme and compromised possible interpretations. In the case of the oratory doors of al-Ḥakam II, included within the interior following the last extension of the Umayyad mosque, it is possible that the original programme has survived. The battlements, also decorated, were studied by

Gómez Moreno (

1951, pp. 40–41) and mentioned by

Pavón Maldonado (

1966, p. 46) as comparable with those in the mosque of Madīnat al-Zahrā.

The most outstanding part of the building, where this decorative scheme reaches unprecedented levels, is the

maqsura. Both in the first of the domes and in the

mihrab and its façade, ataurique decoration is present and has been mentioned in numerous studies (see

Terrasse 1932, pp. 146–47;

Gómez Moreno 1951, pp. 149–53;

Torres Balbás 1955, pp. 434–35;

1957;

Ewert 1991, p. 347;

1995c, pp. 69–81, 121–37). In this instance, the motifs have also been restored, and in some cases, the authenticity of the materials has been called into question.

2 Finally, there is ataurique decoration on some of the modillions (

Torres Balbás 1957, pp. 354–56;

Pavón Maldonado 1987).

Despite the importance of the Umayyad Mosque, ataurique decoration reached its peak at Madīnat al-Zahrā, where such decoration covers large surfaces in up to eight documented ensembles (

Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 423). The most illustrative examples are the mosque of al-Zahrā (

Pavón Maldonado 1966,

1967) and the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān III, unearthed after 1944 by F. Hernández Giménez, who launched a restoration project that, at the time of publication of the present article, is still ongoing. The latter ensemble was the subject of a systematic study by

Ewert (

1995a,

1996), which makes it possible to propose hypotheses about its influence and nature beyond the interpretations ventured by

Velázquez Bosco (

1912, pp. 56–57) after excavations on the upper terrace of the palatial city (

Ewert 1991,

1995a,

1995b,

1996). Other studies have also explored the decorations of Madīnat al-Zahrā and their possible implications (see

Terrasse 1932;

Gómez Moreno 1951, pp. 82–90;

Hernández Giménez 1985;

Acién Almansa 1995;

Vallejo Triano 2004;

2010, pp. 431–64, among others).

The Umayyad Alcázar was also decorated with ataurique carvings. While the continued use of the area and the historical development of the city were not conducive to the preservation of the building, the volume of archaeological material documented in the area (with more than 300 fragments) supports this hypothesis (

A. Montejo 2006;

A. J. Montejo 2015).

The next major ataurique ensemble is that unearthed by F. Hernández in the Cortijo del Alcaide, studied by

Ewert (

1998,

1999). The exceptional number of pieces recovered, together with the monumentality of the structures found, has led to the association of the remains discovered at Alcaide with Munyat al-Nā’ūra (see

Murillo Redondo 2014;

Rodríguez Aguilera 2018) and Munyat Arḥā’ Nāṣiḥ (cf.

Manzano 2018, p. 298). Nearby, in the area of Huerta Valladares, numerous further fragments of ataurique were recovered, as a result of which this place, too, has been interpreted as a

munya (

Castejón Martinez De Arizala 1949;

Anderson 2007). Further studies, however, with more up-to-date information, are needed on these sites.

This brief summary shows the presence of ataurique carvings in sites linked to both the Umayyad dynasty, such as the mosque, the Alcázar and Madīnat al-Zahrā, and a not necessarily Umayyad elite, such as the proposed

munà at Cortijo del Alcaide and Huerta Valladares. Nonetheless, although such ensembles have made it possible to identify the remains of some complexes as

munà, not all

munà nor all their parts necessarily had such decoration. No ataurique material has yet been found at Munyat Ruṣāfa, while at Munyat al-Rummāniyya, the decorative material discovered consists of just 20 fragments, some of which belonged to private collections and were not found during the excavations (

Anderson et al. 2021, pp. 131–52).

The considerable increase in available archaeological information thanks to excavations carried out in Córdoba during the 21st century allows us to test old hypotheses and propose new ones. Urban development has made it possible to observe the increase in urban density that took place during the caliphate in the area between Córdoba proper and Madīnat al-Zahrā, known as the western suburbs, revealing the presence of complexes and buildings in some of which ataurique elements appear, such as those found in Fontanar, Electromecánicas, Fontanar de Cábanos or Block 1 of the O7 partial plan, which is the focus of the present article (

Figure 2).

This block

3 is located, as noted, in the western suburbs of Córdoba, in an area where houses, mosques, baths, streets and markets have been excavated along with other

munà. Unfortunately, the density of urbanisation and the circumstances in which urban archaeological excavations are conducted shape our perception of the structures, which are inevitably viewed from a partial perspective making difficult to identify the different elements that would have been part of the

munya.

During the excavation (between 2007 and 2008), the remains were documented through the preparation of a report, photography and the creation of detailed plans. All materials were bagged and deposited in the Archaeological Museum of Córdoba, ensuring their preservation and accessibility. Among these materials, an ensemble of ataurique carvings found in one of the excavated buildings, together with the nature of the structures unearthed, have stimulated the present research and allowed the interpretation of Building 1 as part of a munya. Today, the archaeological remains are no longer visible, as they have been reburied beneath a complex of modern buildings.

The aim of this work is to analyse the ataurique programme recovered in the excavation of Building 1 in Block 1 of the Partial Urban Plan O7 of Córdoba and collate information about its carving, motifs and archaeological context that may shed light on both the implications of this type of decoration and the building to which this particular ensemble belonged.

The following sections present the archaeological context, an analysis of the ataurique fragments and a discussion of their implications for the understanding of Umayyad elite spaces.

2. Elite Architecture and Block 1 of Partial Urban Plan O7

The western suburbs of Córdoba are extensive urban areas whose population and architectural density increased during the Umayyad caliphate. Their urban growth filled the outskirts of the city not as a progressive expansion to the West, however, but as a development of the productive spaces that already occupied the landscape.

The agricultural exploitation of the territory dates back to antiquity and continued up to the Andalusian period. The late antique agricultural estates came into the possession of the Islamic elite after 711 either because newcomers took them or because the indigenous elite converted to Islam (see

Blanco-Guzmán 2024 and

León 2018). During the Umayyad period we will call them

munà (sing.

munya).

4The classic definition of a

munya defines it as: “

a “cortijo”, a country house surrounded by gardens and farmland, which served as an occasional residence and was, at the same time, both a recreational estate and an agricultural property belonging to emirs, caliphs, and high officials” (

García Gómez 1965, p. 334 as cited in

García Sánchez 2018, p. 18, translated by the author).

These complexes had a civil

5 area or

qaṣr (pl.

quṣur) and a primarily agricultural and productive function evidenced by the presence of fields, or

faḥṣ, and the structures needed for their exploitation. These complexes also included water supply infrastructure, walls, gates and towers, which would have safeguarded the security and privacy of the crops, goods, and individuals inside.

The civil part of the

munya is generally defined by the occasional residence and leisure purpose, which is the most common picture illustrated by the written sources (see

Manzano 2019). Nevertheless, this civil area also fulfilled a representative, political and diplomatic function. Despite their impact in the landscape, the written sources exemplify these aspects when they refer to the

munà as places where to host and lavish high-ranking officials, ambassadors and emissaries (

Ibn Ḥayyān 1981, p. 67, as cited in

Anderson 2005, pp. 191–92).They also contribute to this idea when they refer to them as political spaces, like in Munyat al-Nā’ūra from where the Caliph Abd’ al-Raḥmān III administered justice and executed the one hundred prisoners from Ŷillīqiyya (

Ibn Ḥayyān 1981, pp. 322–23), or government headquarters like in the case of Munyat Ruṣāfa (which was also the regular residence of Emir Abd al- Raḥmān I) (

Murillo Redondo et al. 2018, p. 29) and the

munya of Granada that worked as the Zirid seat of government in the 11th century (

García Sánchez 2018, p. 23).

Its agricultural role would have been fundamental to the economy, enabling the supply of a city whose population grew following the proclamation of the caliphate, placing the control of the means of the production in the hands of the elite (See

González Gutiérrez 2023). The productive nature is also reported by the written sources. Ibn Luyūn’s agricultural treatise includes a description of the different sections of a

munya and their ideal distribution (

Akef and Almela 2021), mentioning the presence of water supply systems, towers and walls that would have reassured the protection and maintenance of the goods but also of the elite that hold the ownership of the

munà.Similar complexes existed in the East during the early Islamic period under the name

quṣur (sing.

qasr). These

quṣur were also peri-urban walled complexes with productive spaces for crops and gardens, as well as civil areas with residences and leisure spaces, as seen at Khirbat al-Mafjar (

Hamilton 1959), Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Sharqī (

Genequand 2008,

2020) or Ruṣāfat Hisham (

Sack 1996;

Key Fowden 2004), just to mention a few. Even though the nature of the buildings and the historical development of the complexes as territorial control points have strong common roots; however, the word

munya is not documented with reference to these complexes in the East even once (

Manzano 2018, p. 313).

Both in the East and in the West, nonetheless, these complexes became centres that attracted large numbers of people, around which small neighbourhoods developed, with houses, mosques, baths, streets, cemeteries and other spaces. In the East, this can be seen clearly at Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Sharqī (

Genequand 2008), and in Córdoba, at Ruṣāfa (

Murillo Redondo et al. 2018). In the case of the western suburbs of Córdoba, these peri-urban complexes acted as focal points around which the urban fabric gradually organised itself (See

León 2018;

Manzano 2018;

López-Cuevas 2014;

Murillo Redondo 2014).

While those

munà that were further from the madīnat probably maintained their perimeters, as we might hypothesise in the case of al-Rummāniyya or the remains excavated at Cortijo del Alcaide, identified with Munyat al-Nā’ūra and Munyat Arḥā’ Nāṣiḥ (

Cfr. Rodríguez Aguilera 2018;

Manzano 2019, p. 298;

Arnold et al. 2021), those established nearer to the city’s western walls were absorbed by the urban fabric, a fact that blurs their limits and complicates their interpretation.

In 2014, J. Murillo collected information on 43 “unique buildings” that could potentially be interpreted as

munà, noting that while several of these structures may have been such complexes, not all of them should necessarily be interpreted as such (

Murillo Redondo 2014, pp. 86, 103–6). The textual sources also provide some insights on this point. Al-Jušanī, writing in the 10th century, describes how the judge Aslam Ibn Abd al-‘Azīz went to another judge’s

munya so that he could tear apart the wall himself, expanding the road–an action that implied the loss of two rows of trees (

Al-Jušanī 1914, p. 234 as cited in

Manzano 2018, pp. 420–21, n. 49). As this suggests, when the suburbs (and their houses, mosques, markets, cemeteries and baths) occupied the available space, they erased the boundaries of elite estates, creating a new, urban dynamic.

Under these circumstances, identifying

munya architecture within the urban pattern and distinguishing residences from

munà, relies on the identification of their characteristics at a smaller scale. In the case of Block 1 of the Partial Urban Plan O7 in Córdoba, numerous structures were unearthed, representing different phases and buildings. However, the presence of three large open spaces or gardens, water supply systems, substantial residential structures, and an ataurique decorative programme led its archaeologists to interpret the site as a

munya (

Costa Palacios 2009).

2.1. The Archaeological Evidence from Block 1

The structures excavated in Block 1 (

Figure 3) illustrate an interesting stratigraphic sequence that runs from late antiquity to the late Islamic period

6 (

Table 1).

The oldest remains excavated in the block have been interpreted as belonging to a phase preceding the proclamation of the Umayyad Caliphate (year 929). They consisted of a productive space, with several rooms around a central courtyard. The complete disposition of the building remains unknown due to repurposing in the following phases and the boundaries of the excavated lot.

With the beginning of the Umayyad caliphate, the plot underwent a major transformation. The architecture developed and the number of buildings increased. In the first caliphal phase, chronology consistent with the ceramic record (

Costa Palacios 2009, pp. 88–89), we can distinguish four open spaces with pools, wells and noria wells for water supply, maintaining the complex’s productive nature. The productive role of the

munà would have shaped the suburban landscape prior to the area’s urbanisation and would have acted as a focal point for the increase in urban density.

In phase 3, a second phase under the Umayyad caliphate, these productive buildings were indeed integrated into the urban fabric, disposed around two streets. In this phase, Building 1 was created along with a bath complex and other buildings whose functions may have been productive, residential or something else. The arrival of many people in the Umayyad capital, attracted by its growth and stability, forced a change in this area. The previous architecture was repurposed, and many additional structures were built in the same space. In the absence of a perimeter wall, determining which of these were part of the development of the munya architecture and which were constructed to accommodate the new inhabitants remains a difficult task.

Between this moment and the abandonment of the plot (in the 11th to 12th centuries), some buildings were further repurposed or underwent minor transformations. Finally, there was a residual occupation of the plot that persisted until the 12th century, when the structures began to be looted and a few lime kilns were established for the reuse of materials (

Costa Palacios 2009, p. 93).

Within this intricate pattern of development, identifying the civil area of the munya remains key to its identification as such a complex.

2.2. Building 1

Building 1 (

Figure 4) is located in the eastern half of the block and it is important to note it was not fully excavated due to the constraints of the construction programme. It is defined by a street to the west and by other buildings to the north, east and south (

Figure 5). It consists of three main bays of multiple rooms, organised around a sunken central courtyard that would have contained vegetation and had a water supply system. It was built in the second caliphal phase (in the mid-10th century) partially over the remains of earlier structures, which featured two courtyards complete with irrigation pools, wells and a water supply system, leading to their interpretation as productive spaces.

The central courtyard was around 0.5 m lower than the occupation level and included a pool, attached to the south side, and a well.

The three bays that opened onto the central courtyard (to the south, east and west) were connected by a perimetral walkway, perhaps porticoed on the south side (see below). The three bays followed the same main scheme: a central hall flanked by two lateral alcoves and further rooms on the long sides. The sizes of the rooms varied (

Table 2). Two construction techniques coexisted in the building. The first, present in the east and west wings and the north wall, was based on masonry using various types of stone, including reinforcing ashlar blocks placed at short intervals. The south bay, however, was built with calcarenite ashlar masonry laid in a triple stretcher and header bond. The roofs would have been covered with ceramic tiles, and the entire structure would have been coated with lime mortar, with the plinths painted in red almagra.

This distribution of spaces was not an innovation. Many identified

munà had a similar axial scheme of alcove–hall–alcove connected by a perimeter platform which opened onto a central courtyard with a pool located (in the majority of cases) in the northern part of the courtyard (

López-Cuevas 2014, pp. 169–70). In the case of Building 1, we indeed find three bays that follow the same axial scheme. The main space, however, like the pool, was located to the south and oriented towards the north. This orientation would have resulted in almost no exposure to sunlight, an effect further reinforced by the presence of a porticoed space between the hall and the courtyard rather than just a perimeter platform. No similar northward-oriented spaces have been found.

The halls in the south and east bays had a floor coated with red almagra, while the west bay had earthenware tiles measuring 20 by 20 cm. Of the alcoves, only those in the south bay have largely preserved their pavement (and even these not entirely), which is also coated with red almagra. One of the alcoves of the west bay, however, is partially preserved, and a tiled pavement (as in the hall) can be seen. The pavements and their material have been used to interpret the function of these spaces as in, for example, the use of almagra only in halls and alcoves (See

Camacho Cruz 2008, p. 223;

López-Cuevas 2014, p. 176) which could indicate a greater importance of the southern wing.

The archaeological record of Building 1 includes the discovery of decorative metal furniture fittings, worked bone and ataurique elements inside the pool. These ataurique elements have been a decisive element in the building’s interpretation, as their study and analysis has provided substantial information about its elevation and, moreover, about the financial means and intentions of its owner.

3. The Role of Ataurique Decoration

3.1. Ataurique Findings in Building 1 and Archaeological Analysis

In Building 1, 132 fragments of ataurique have been identified in various locations, with the highest concentration located inside the pool, although pieces have also appeared scattered throughout the courtyard and other rooms (

Figure 5). All of the relevant strata belong to the point at which the building was looted and abandoned. Thus, we can conclude that the ataurique programme was discarded in the pool and around the central garden area since it was an obstacle for accessing the construction materials.

Morphological analysis and the distribution of the fragments have made it possible to identify at least two decorated entrances, probably three (one in each bay).

The main programme was located in the south bay and was probably preceded by a large porticoed space (E-2). The opening in this façade, associated with 114 ataurique fragments made exclusively of limestone, led into hall E-4.

For this location, we estimate the presence of a 6-m-wide opening with a central arch framed within a decorative programme measuring 3 m across and 3 to 3.5 m in height (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The height can be estimated thanks to the preserved foundation of the calcarenite ashlar wall that delimited the northern edge of the hall, which is 0.5 m thick, making a higher elevation unlikely. Additionally, a door pivot stone has been preserved in stratigraphic position, aligned with the edge of the pool and 1.9 m from the western edge of the hall. If we trace a line from the opposite edge of the pool to the hall and note the point at which it intersects the wall, we find ourselves 1.88 m from the eastern edge of the hall, an almost identical distance. This demarcates a 6-m opening, coinciding with the maximum length of the pool. Within these 6 m, between two pivot stones, the decorative programme would have been located, framed in a 3 by 3/3.5-m space, with the access arch at its centre.

Based on the metal remains (sheets and nails) found in the pool, the presence of two metal-clad wooden doors can be proposed, which, when opened, would have revealed the decorated entrance.

Study of the ataurique remains and their identification with the architectural elements they covered allows for the hypothesis of a single central decorated arch, approximately 3 m wide and between 3 and 3.5 m high, as previously mentioned, featuring ataurique decoration on the baseboards, voussoirs, spandrels, alfizes and friezes.

The proposed dimensions of the arch and entrance opening are based on the analysis of significant fragments, with the presence of a spandrel fragment large enough to trace the outer circumference of the arch (

Figure 8) and voussoirs with their upper ends intact making these calculations possible.

In the east bay, the presence of material beside the perimeter walkway and two pivot stones in stratigraphic position make it possible to identify a 6.78-m opening with a decorated arch, from which 21 ataurique fragments have been preserved (4 in limestone and 17 in plaster), associated with a frieze and a panel. The mixture of materials and the fragments’ likely positioning suggest that the eastern opening had less decorative significance than its southern counterpart. Furthermore, in contrast to the southern portico, this space only featured a slight widening of the perimeter walkway as its antechamber (E-9).

In the west bay, which has not been fully excavated, the space is laid out symmetrically to the opposite bay, including the slight widening of the perimeter walkway (E-18). The discovery of fragments in room E-15 and in the courtyard suggests the existence of a similar decorated opening. The building could thus have had three decorated openings with ataurique programmes, with the south bay serving as the main area of the building and all bays opening onto the central courtyard, which would have contained vegetation. The entrances were preceded by open spaces, most notably the large porticoed area of the south bay (E-2), which would also have featured other decorative elements, such as hanging pieces attached to the ceiling, designed to be viewed from below (see below). The east and west bays would have presented a smaller-scale decorative programme, which, together with the garden, contributed to an environment of ostentatious display and leisure.

The abstraction of nature found in ataurique motifs created an ornamental language whose interpretation could improve our understanding of Umayyad Córdoba. The motifs themselves, as well as the carving techniques used, have been the subject of multiple analyses. Although the true significance of this decoration remains hypothetical, we can confidently establish that the quantity of material and its prominent location within Building 1 are linked to elite status and have a local identity.

3.2. Techniques and Tools

The ataurique constitutes the decorative cladding of the various architectural elements that make up Building 1’s elevation. The carvings cover various architectural elements, acting as a sort of skin. In some cases, however, the motifs have been carved directly into the element in question. Regarding their characteristics, there is no homogeneity among the pieces: unlike other ensembles, such as the mihrab of the Umayyad mosque, where some panels were executed as single pieces, in this case, it is common for panels to be composed of several fragments, as seen at Cortijo del Alcaide or Madīnat al-Zahrā. In a way, this is reminiscent of a mosaic, with smaller fragments forming a larger decorative element that adapts to the surface to be covered.

Although the decorative scheme fits together perfectly, the pieces display heterogeneity in their workmanship, pointing to precise planning and perhaps the involvement of multiple hands. Differences between artisans’ hands can be observed in the preference for working with thicker or thinner pieces, as well as in the treatment of the reverse side. As shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, fragments belonging to the same programme present diverse finishes on their reverse: some have been smoothed with a stone cutter’s hammer, others display what appear to be flat chisel or toothed stone axe marks and others still exhibit various patterns of chisel work that would have improved their adhesion to the lime mortar used to attach the pieces to their architectural supports.

These traces not only allow us to identify some of the tools used in the production of the ataurique (chisel, drill, broad chisel, flat chisel, toothed stone axe, stone cutter’s hammer, pointing tools, compass) but could even be distinctive of the patron or the workshop that executed the work.

The volume of ataurique associated with Umayyad Córdoba–with major groups including those from Cortijo del Alcaide, the mosque, Huerta Valladares and Madīnat al-Zahrā–suggests the existence of one or more organised local workshops, in which the various tasks would have been carried out by different members in successive phases through layout, carving and finishing. The study of these workshops is an ongoing line of research.

Once the carving was completed, polychrome decoration may have been applied. In the case of Building 1, however, polychromy has only been documented on the fragments that formed the star (analysed below). Finally, the pieces were affixed in their positions with lime mortar, which, in the case of friezes and panels, also served to fully integrate them into the architecture.

3.3. Motifs and Stylistic Analysis

The preserved fragments of ataurique have reached us in the form of debris, which prevents us from appreciating the decorative programme as a whole. Nevertheless, the presence of certain motifs allows us to establish parallels and connections with other sites, which could enable us to take the first steps towards a chronotypology or the interpretation of ataurique as a decorative language. Some of the most relevant motifs are discussed below. The aim of this work is not to provide a symbolic reading of ataurique decoration, whose representative character we estimate based on the investment the owner made and the location chosen for its display. Nevertheless, the use of certain motifs and the way they were executed can serve as a basis for establishing connections between different places.

3.3.1. Complex Palmettes

A key motif that stands out is the so-called complex palmette, composed of three small trifoliate leaves surrounded by a stem that generates scrolls. This motif is also documented in the mosque of Córdoba (

Figure 11B), on the exterior entrances and on the

maqsura and the gates of al-Ḥakam II (enclosed within the building after the latest expansion) and the mosque of Madīnat al-Zahrā (

Figure 11C). The geographical dispersion of this motif and the locations where it appears are indicative of the relative value or significance it may have held, as has been noted in previous publications (see

Vallejo Triano 2004). These palmettes were not, however, included by C. Ewert in his catalogues of the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān and the Cortijo del Alcaide (

Ewert 1996,

1998). From this form, more complex variants emerged, which became omnipresent in Córdoba’s ataurique, both at Madīnat al-Zahrā and elsewhere.

3.3.2. The Star

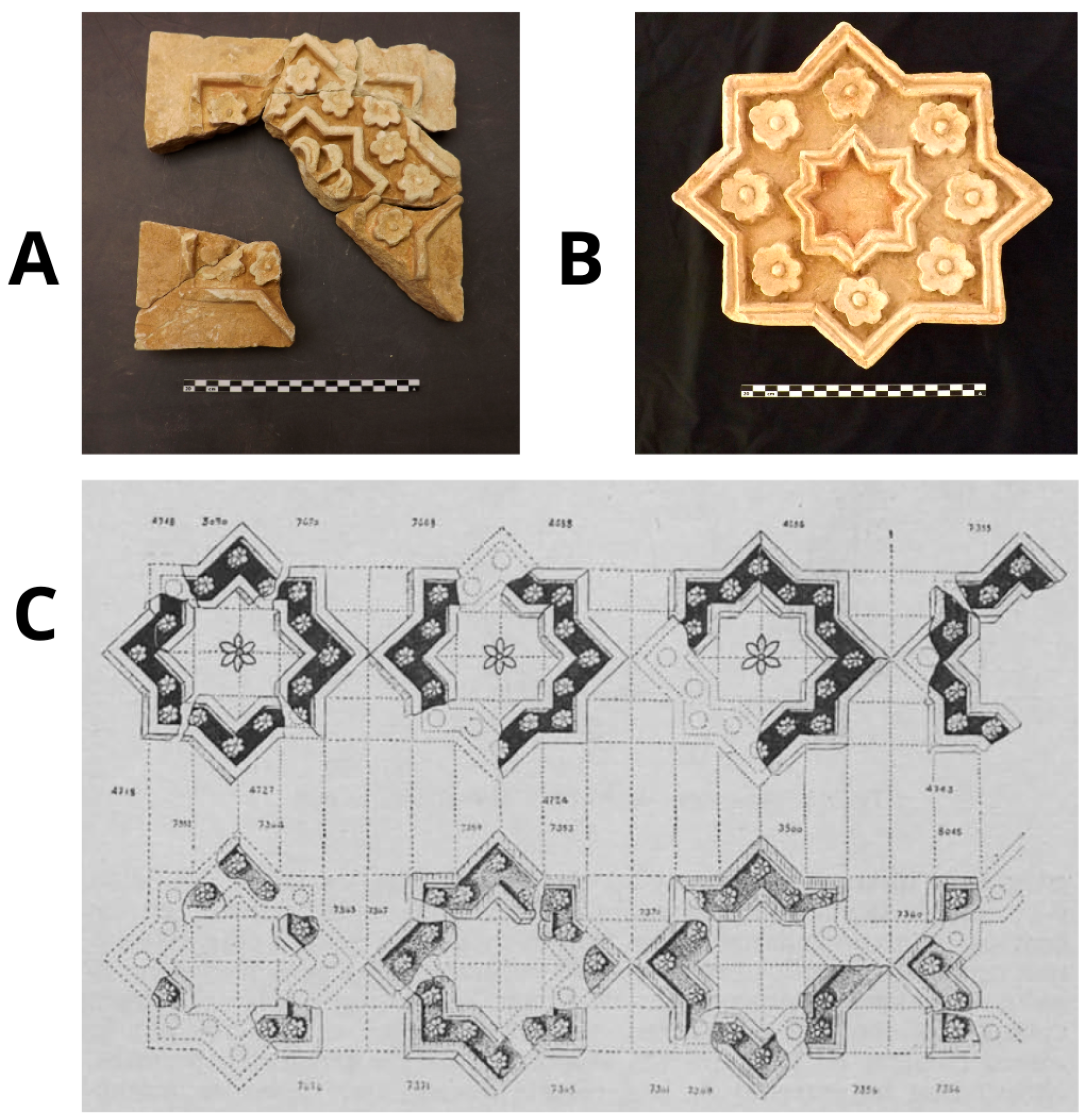

The star found in Building 1 (

Figure 12A) is particularly interesting: it is an eight-pointed design decorated with six-petalled flowers between an inner and outer outline and an abstract vegetal motif in the centre. It preserves red polychromy on behind the flowers but not on them. The element lacks detail, marks or motifs on its back, which was, instead, completely smoothed using a stone cutter’s hammer, suggesting that it may have been a movable element rather than an architectural facing. Another, similar piece has been found in Córdoba in the Ronda Oeste (

Figure 12B), also featuring eight points, though not inscribed in a square, with another eight-pointed star in the centre and six-petalled flowers in its design. This example preserves polychromy on the inner star and similarly shows no work on the reverse. Similar examples come from the excavation of the mosque of Madīnat al-Zahrā (

Figure 12C), with several eight-pointed stars documented there, lacking polychromy and featuring a hollow centre and inscribed six-petalled flowers. Some have their backs smoothed, while others, according to

Pavón Maldonado (

1966, p. 90), have “a circle to fit the piece into the wall cavity”, a feature absent from the first two stars mentioned above. All of them were found in exterior areas. Furthermore, in the friezes of the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān, eight-pointed stars with inscribed six-petalled flowers also appear, although these are not freestanding. Although there is currently insufficient evidence to propose a specific function for these elements, the scarcity of examples (only two in the western suburbs: one in the Ronda Oeste and another in Building 1) and the dispersion of the few that do exist could indicate a link with the Umayyad dynasty.

3.3.3. The Double Palmette with Central Drop

The double palmette with central drop decorates the arch ring of the entrance of E-4 in Building 1 (

Figure 13A) and also appears in the mosque of Madīnat al-Zahrā (

Figure 13B) and the mosque of Córdoba in the same architectural position, as well as in the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān, where it forms part of other elements (

Pavón Maldonado 1966, Figure 87;

Ewert 1996, p. 16, ill. 3). This motif is particularly interesting because of its spread. Derived from classical iconography, it appears around the Mediterranean during antiquity, late antiquity and after the rise of Islam. Its position in architecture, however, is notable, since the examples belonging to Umayyad Córdoba happen to appear specifically in arch rings, such as in the church of Yoldat Āloho at Ḥāḥ, in the church of Mor-Yuḥannon à Qēleth and at Rusafat Hisham (

Ulbert 1993, p. 221;

2004, p. 390;

Keser-Kayaalp 2013, p. 291;

2019, p. 279). Further studies and analysis are nonetheless needed before interpretations and conclusions can be drawn about workshops or influences.

3.3.4. Hanging Independent Pieces

Another notable stylistic element in Building 1 is the hanging independent pieces, which are richly decorated with palmettes and pinecones (

Figure 14). These elements are carefully carved on all sides except for one, which appears intentionally left unfinished or flat, presumably to facilitate their attachment to another architectural component. The comprehensive treatment of their other surfaces, along with the intricate elaboration of the pinecone motif, suggests that these pieces were specifically designed to be viewed from below, maximising their visual impact on people standing in the space beneath them.

When we examine the architectural features of the south bay of Building 1, it becomes evident that the dimensions and spatial organisation lend themselves to the space’s interpretation as a porticoed area. Such a configuration would have served not only an aesthetic function but also a practical one, shielding decorative elements positioned on the façade of the hall’s northern wall from direct sunlight, rainfall and other potentially damaging weather conditions. With this taken into account, along with the presence of three distinct hanging elements found in this context, it is plausible to hypothesise that these ornaments were intended to decorate the ceiling of this portico, enhancing both its visual richness and its protective qualities.

However, the precise height and exact positioning of these pieces remain uncertain. It is possible that they adorned an eave positioned slightly below the main roofline, serving as a prominent decorative feature when viewed from the courtyard or entrance to E-4 (

Figure 4). Alternatively, they may have been fixed directly to the roof structure itself, contributing to the overall artistic composition and highlighting the importance of the space they embellished. In any case, the distinctive workmanship and strategic placement of these pieces underscore their significance in the decorative programme of Building 1, and they offer valuable insights into both the artistic choices and the functional considerations of the period’s architecture.

Finally, it should be noted that not only does the presence of certain motifs allow us to establish hypotheses regarding their survival, importation, message and chronology, but the absence of other specific motifs can be equally revealing and significant to an iconographic analysis. None of the ataurique pieces studied in Building 1 of Block 1 can be interpreted as acanthus or as part of the hom or tree of life, motifs that, by contrast, are prominent in emblematic spaces such as the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān III at Madīnat al-Zahrā and the Umayyad Mosque. The acanthus, in particular, is a fundamental element of the decorative programmes featuring ataurique executed in limestone in the Umayyad Mosque, highlighting its important symbolic and aesthetic role in such settings. Likewise, hom or tree of life motifs occupy prominent positions in both the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān III and the Umayyad Mosque, where they are found adjacent to the mihrab, underscoring their spiritual and symbolic significance. The absence of these motifs from Building 1’s decorative scheme should not be seen merely as a decorative void or a simple oversight but rather as a potential reflection of specific cultural, symbolic or artistic intentions that influenced the selection and reproduction of certain decorative motifs while excluding others. In other words, the non-appearance of certain symbols can also provide information about regional differences, local traditions, stylistic influences or even shifts in world views and aesthetic values. The absence of a motif in a given context is thus equally interesting and useful for gaining a deeper understanding of the historical and cultural context of the art and architecture under study.

4. Final Considerations and New Perspectives

The study of the ataurique programme in Building 1 of Block 1 has allowed for different readings of it, from the hypothetical reconstruction of the south bay façade to the interpretation of the architectural setting as a place of display and self-representation. Ataurique and its study can also provide information about the contexts in which it is found and contribute to our knowledge of Andalusian society, culture and architecture.

From a formal point of view, the cataloguing and analysis of decorative programmes can provide information about the function and nature of different structures, as well as their architecture. Ataurique decoration, on account of its having covered architectural elements such as jambs, friezes, voussoirs and spandrels, allows us to reconstruct, at least partially, the original façades to which it belonged, even after a process of plundering. In the case of Building 1, we find a programme that was designed for a structure built in the 10th century, during the Umayyad caliphate, and that was discarded in the pool and garden once the building was abandoned prior to the looting of its materials in the 12th century.

Meanwhile, the morphological characteristics of the pieces, their techniques and their carving allow us to hypothesise the existence of specialised workshops which, judging by the amount of recovered material, its geographical distribution and its historical context, must have developed in Córdoba during the caliphate.

The deployment of resources involved is indicative of a significant economic investment and the high status of the work’s commissioner. The decorative programme is far from having a utilitarian nature or being a necessity, unlike the central open space occupied by a garden with a pool, which may have an agricultural purpose. The discovery of the ataurique fragments can be directly related to the owner’s intentions of self-representation and of adding value to a series of rooms meant to be seen (we might also consider the absence of documented kitchens or latrines within the building).

This premise allows for hypotheses regarding the representational aspect of this decoration and a possible new direction for future research, examining whether this form of decoration was exclusive to the Umayyad dynasty. The level of development achieved by this decoration at sites such as Madīnat al-Zahrā and the Umayyad Mosque, as well as the finding of over 300 fragments in the Alcázar and its surroundings (see above), may lead to our reading ataurique as an ornamental language of the Umayyad dynasty. The presence of ataurique at sites interpreted as munà does not detract from this interpretation.

As was stated at the beginning of this paper, not every munya has ataurique. This may be due to multiple reasons: either the specific location of the decoration has not been excavated, the process of plundering eliminated it or other events led to the deterioration and loss of the ornamental programme. For example, the building interpreted as a munya in the Ronda Oeste of Córdoba has not yielded a decorative programme with ataurique, although fragments have appeared there (as well as lime kilns).

It is interesting, however, to consider that the presence of this decoration may have depended on the ownership of the estate. Written sources list dozens of

munà, some of which belonged to members of the Umayyad family, others to members of the court and others directly to the elite. For example: Ibn Ḥayyān mentions how every male son of caliph Abd’ al-Rahman III would receive either a house in the city and a

munya in a good location (

Ibn Ḥayyān 1981, p. 21). Such a premise would hold in the case of the Cortijo del Alcaide in its interpretation as Munyat al-Nā’ūra and could be justified in the case of Munyat al-Rummāniyya. In the latter, built by al-Durri and later given to al-Ḥakam II, a decorative programme with ataurique similar to that seen at other sites has not been found, but ataurique does appear in movable elements such as basins and a decorated panel which is associated with the site but does not belong to a known archaeological context, instead being a museum acquisition (

Anderson et al. 2021, pp. 131–52). This could suggest that, at the time of construction, no decorative programme with ataurique was planned, but that some additions were made at a later stage, perhaps when the ownership of the property changed. Likewise, the absence of ataurique carvings at Munyat Ruṣāfa could be explained by the partial nature of excavations or the early date of the complex’s construction without this example’s being considered a counterargument to the above premise.

A further topic for consideration is that of isolated finds. There are cases, in the western suburbs, where pieces have appeared in domestic, religious or commercial structures whose stratigraphic context places them in a period prior to the collapse of the structures. Further studies are necessary before hypotheses can be established about the utility of this decoration or whether pieces were found in their original locations.

Although these lines of research stem from an archaeological perspective, the study of the motifs that compose the ataurique schemes has also attracted the attention of various authors hoping to identify certain influences and/or contributions that could be interpreted as evidence of the exchange of ideas or individuals between East and West or of the survival of a tradition that originated in Roman Hispania and evolved during late antiquity.

The case of Building 1, however, is illustrative in this respect. In this complex appear motifs found at other sites in Córdoba, allowing hypotheses about local workshops that may have been dedicated to producing this decoration. Nevertheless, these motifs are also present in the East, North Africa, and late antique Hispania. Beyond these identified similarities, the lack of a sufficiently large, contextualised sample (in both East and West) to establish interpretations makes it necessary, again, to look to further studies in this regard, since the formal similarity of the motifs does not necessarily imply the direct transmission of knowledge or the exclusive influence of a single place.

On a local basis, the study and cataloguing of the different motifs, together with their archaeological contextualisation, could shed light on a potential chronotypology that would allow us to appreciate any identifiable evolution of the motifs. At the end of the 20th century,

Ewert (

1998) published an article that referred to the panels of the Cortijo del Alcaide as the artistic expression of the final moments of the caliphate, with his main argument being the presence of numerous motifs both there and in the Hall of Abd’ al-Raḥmān III at Madīnat al-Zahrā. The amount of material discovered in the 21st century, however, makes necessary a review of the available material and its contexts, since not only can the presence of some motifs be considered indicative of a chronotypology, but their absence can also be interpreted in this way. For example, the absence of the

hom or tree of life in the decorative programme of Building 1 can be read as indicating this motif’s exclusivity of use by that same caliph or as dating the programme to before the insertion of this motif into caliphal plastic arts.

In conclusion, in the case of Building 1 of Block 1, the ataurique programme allows us to suggest that the building was designed as a space of self-representation; at the moment the building ceased to be useful, it was abandoned and later plundered, which has allowed it to be interpreted as part of a munya. However, unresolved questions remain, such as who the owner might have been, whether the decoration can be interpreted as showing Eastern or North African influence or purely peninsular heritage, whether it can be used to extract greater information about the chronology of the complex and what possible message it sought to convey.

Broadly speaking, decoration with ataurique motifs, which reached its peak and widest dispersion in caliphal Córdoba (in the 10th to 11th centuries), can be considered a representative element of the place and period. This decoration appears in locations that can be regarded as spaces of self-representation for certain figures who, as members of the elite, sought to demonstrate that membership or rank through such display. Consequently, the presence of ataurique in this kind of contexts could be interpreted as a distinctive element of elite architecture and specifically of the presence of a munya, although, given the productive nature of such complexes, not all of their buildings would have had this decoration.

Despite these conclusions, however, only the continuation of studies on ataurique in Umayyad Córdoba will allow us to develop a better understanding of these spaces of self-representation inside the munà, the semiotics of decoration and the role of the elite in the organisation of urban territory.