Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens

Abstract

1. Introduction

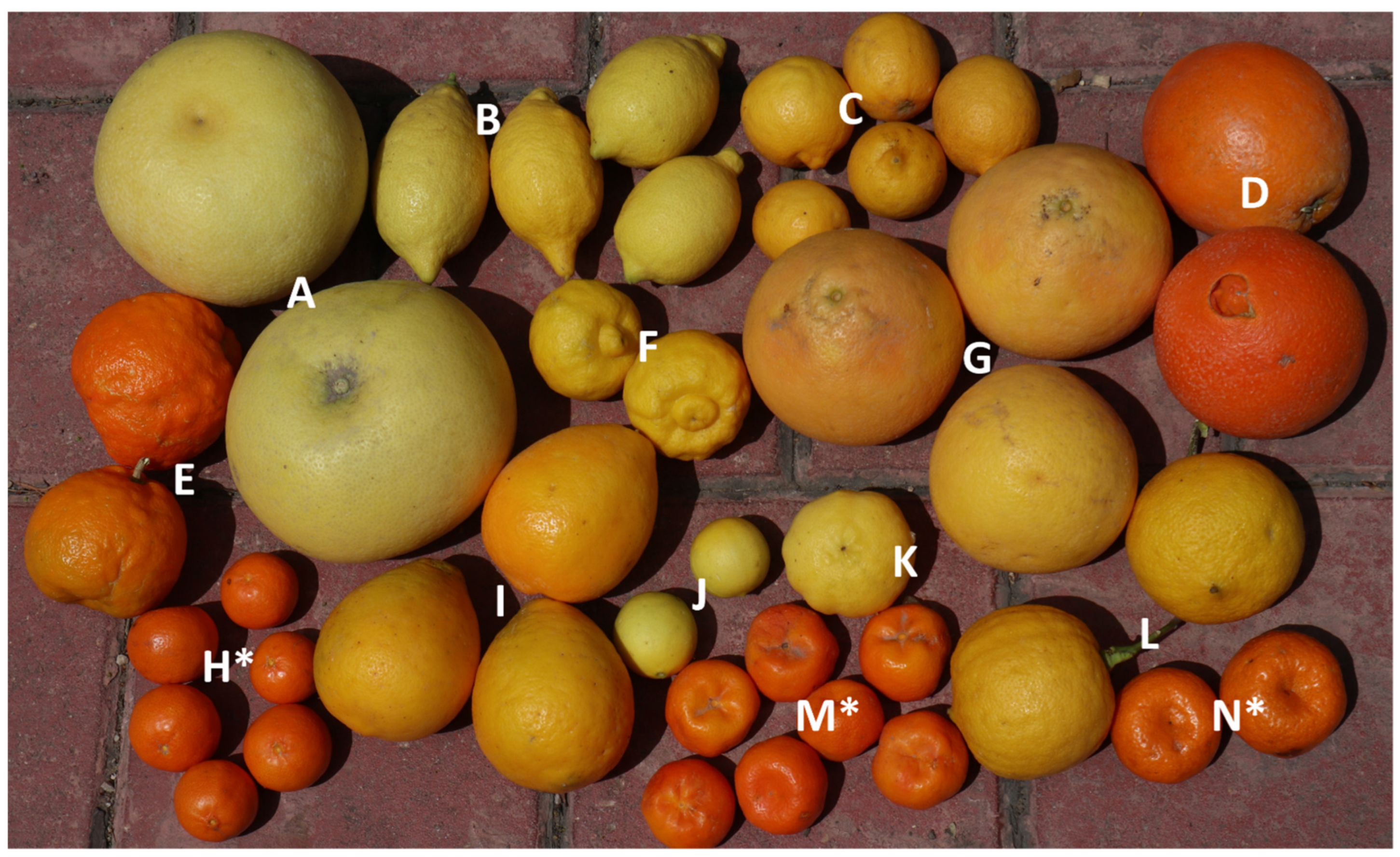

1.1. Overview of the Genus Citrus and Its Historical Significance

1.2. Introduction to the Mediterranean Origins of Citrus Cultivation

1.3. Citrus Fruits as Symbols of Luxury and Status, Aims of This Review

2. Results

2.1. Early Introduction of Citrus Fruits: The Mediterranean Origins of Citrus Cultivation

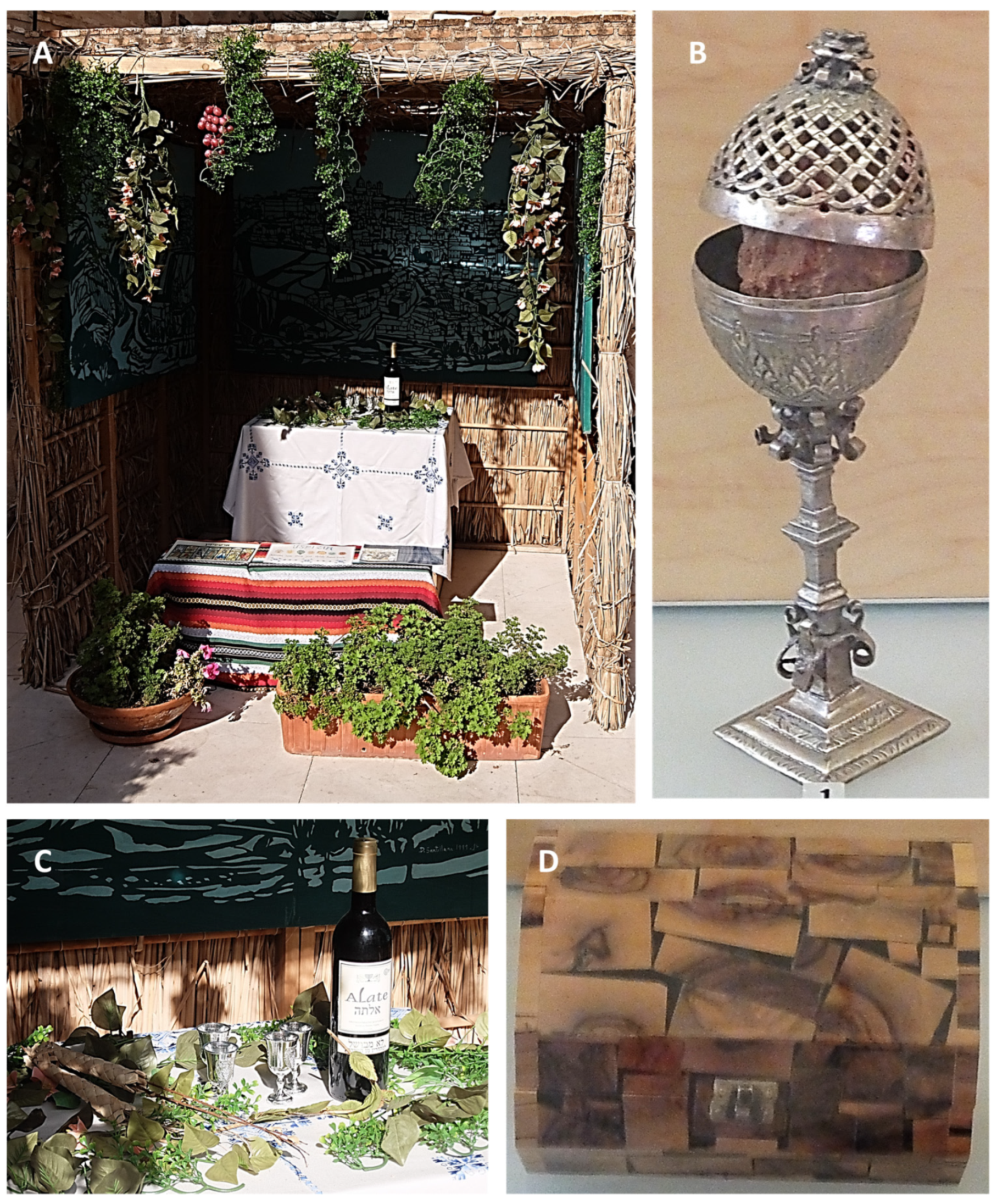

2.2. The Religious and Cultural Significance of Citrus in Jewish Tradition: A Historical Analysis from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

2.2.1. The Origins and Early Ritual Applications of Citrus medica L.: Archaeological and Historical Evidence from the Ancient Near East

2.2.2. The Ritual Persistence of Citrus medica L.: Cultural Continuity and Adaptation Among Diaspora Jewish Communities in Medieval Europe

2.2.3. The Image of Citrus medica L.

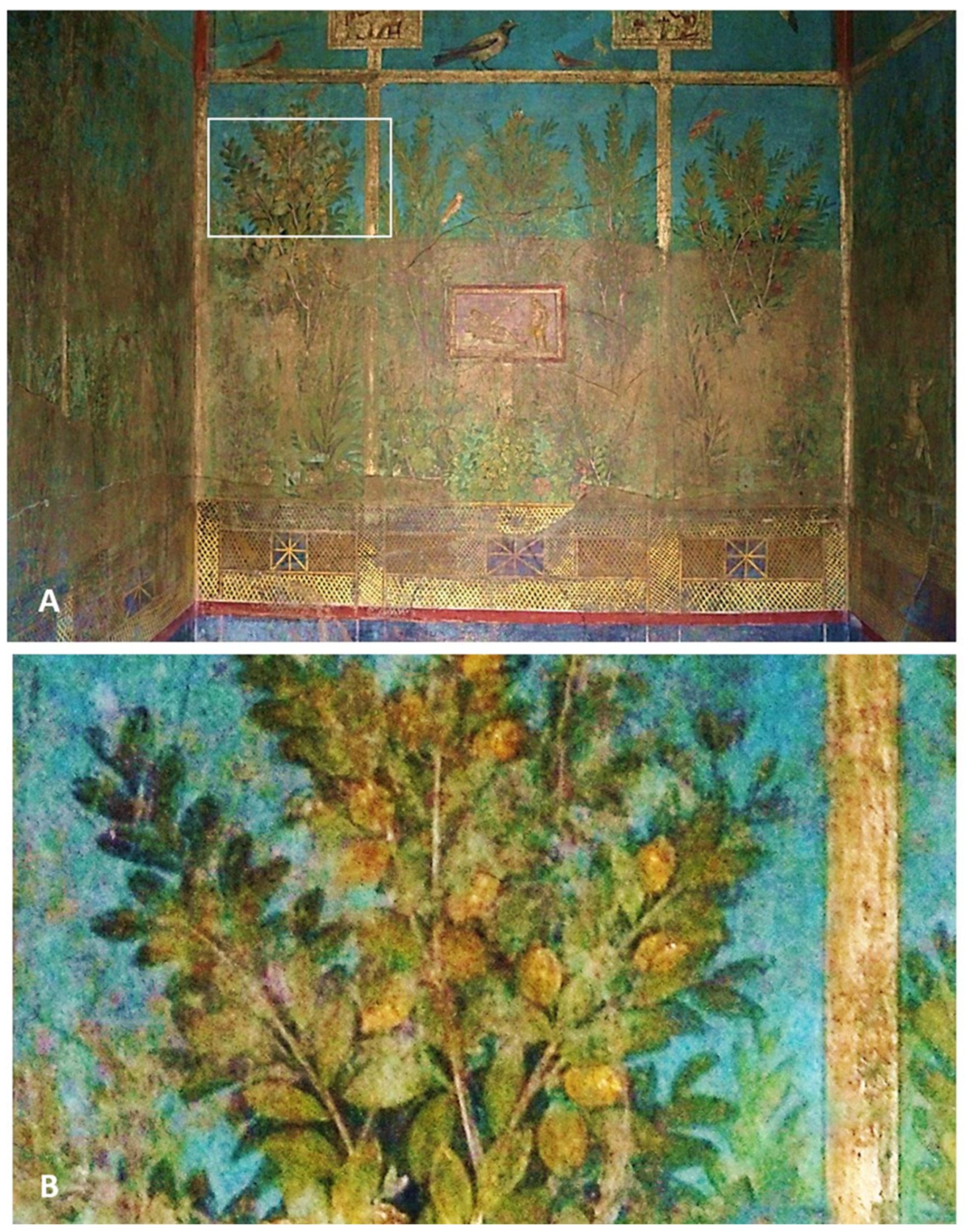

2.3. Citrus Symbolism and Representation in Roman Life and Art

2.3.1. Citrus Fruits as Exotic Commodities for the Elite

2.3.2. Analysis of Citrus Depictions in Frescoes and Mosaics

2.3.3. Ornamental Value and Symbolic Meanings Associated with Citrus Fruits

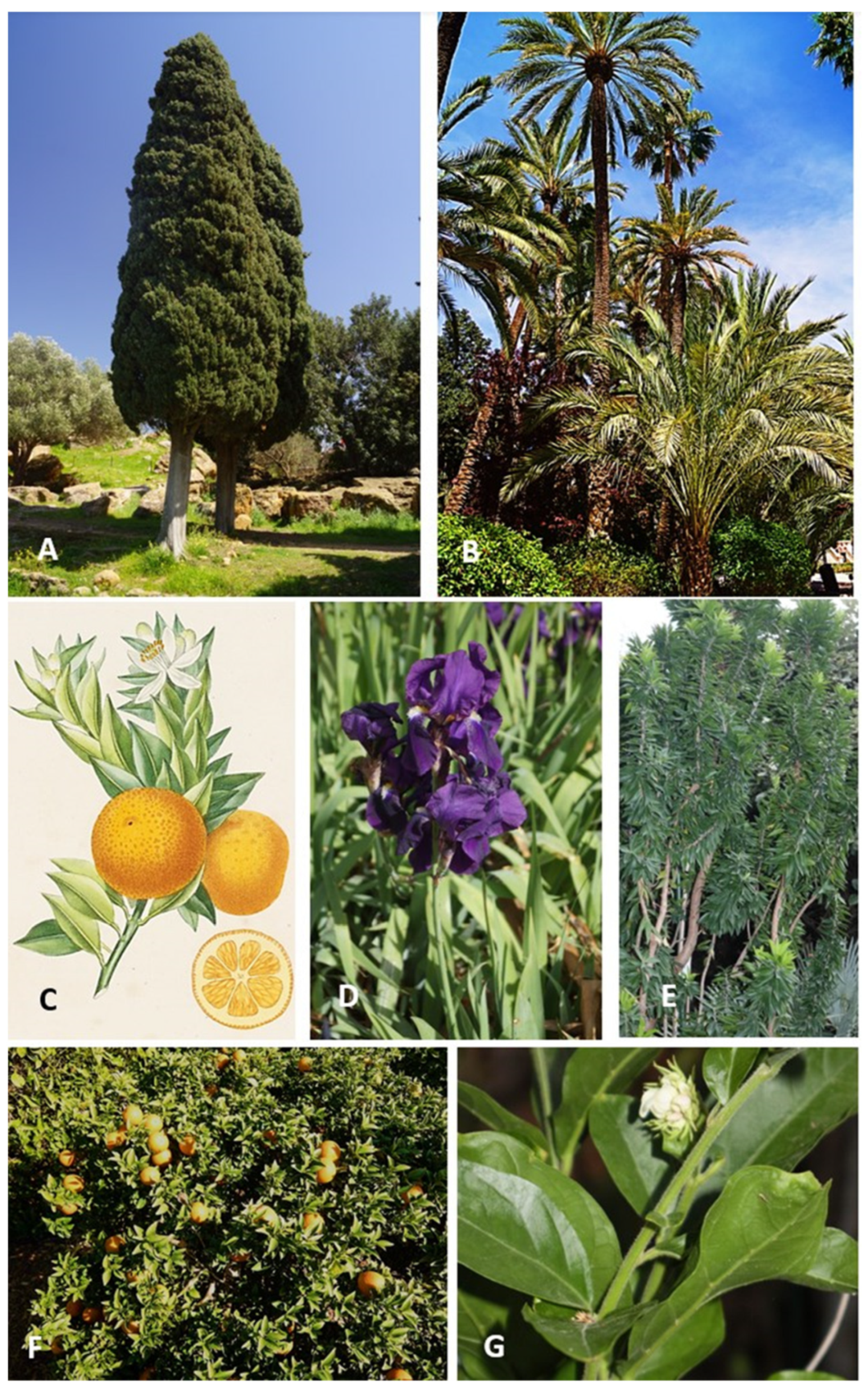

2.4. Citrus in Western Islamic bustān Gardens

2.4.1. Importance of Citrus in Western Muslim bustān Gardens

2.4.2. Symbolism and Cultural Significance of Citrus in Western Muslim Gardens

2.5. Citrus in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia: The Role in Europe of Christian Gardens

2.5.1. Citrus’ Role in the Medieval Gardens of Iberia

2.5.2. Citrus Use in the Renaissance Gardens of Iberia

2.6. Norman Gardens of Sicily: The Role of Citrus

2.6.1. Citrus Cultivation in Norman Gardens of Sicily

2.6.2. Influence of Norman Rulers on Citrus Cultivation and Symbolism

2.7. Renaissance Peri-Urban Villae: Citrus Collections and Elite Culture

2.7.1. Emergence of Peri-Urban Villae During the Renaissance

- Orange Trees and Unicorns (Figure 20B,D):

- 2.

- Orange Trees and Lions (Figure 20C,E,F):

- 3.

- Exclusion from in the Tapestry of Sight:

2.7.2. Citrus Diversity and Role in the Renaissance Gardens

2.7.3. Citrus Collections as Symbols of Prestige and Luxury for Elite Families

3. Discussion

3.1. Multidisciplinary Analysis of Citrus Symbolism: Contribution of Biological, Archaeobotanical, Iconographic, and Textual Sources

3.2. Examination of Divergent Views on Citrus Symbolism

3.3. Transformation of Citrus Varieties from Symbols of Luxury to Global Agricultural Staples

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Académie Française. 2024. Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française. Available online: https://www.dictionnaire-academie.fr/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Akef, Walid, and Iñigo Almela. 2021. Nueva lectura del capítulo 157 del tratado agrícola de Ibn Luyūn. Al-Qanṭara 42: e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bukhari, Muḥammad ibn Ismail. 2023. Encyclopedia of Sahih Al-Bukhari. New York: Arabic Virtual Translation Center. Available online: https://www.google.es/books/edition/Encyclopedia_of_Sahih_Al_Bukhari/coMlEAAAQBAJ?hl=es&gbpv=1 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Al-Bukhari, Muḥammad ibn Ismail [Al-Bujārī]. 2002. Ṣaḥīḥ. Damasco-Beirut: Dār Ibn Kaṯīr. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bukhari, Muḥammad ibn Ismail [El-Bokhâri]. 1992. Les Traditions Islamiques. 4 vols, Abidjan: Jean Mabille éd. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kutubī, Muḥammad ibn Šākir. 1974–1975. Fawāt al-Wafayāt. 5 vols, Edited by Iḥsān ʽAbbās. Beirut: Dar Sader. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maqqarī, Aḥmad b. Muḥammad. 1968. Nafḥ al-Ṭībb min gusn al-Andalus. 8 vols, Edited by Iḥsān ʽAbbās. Beirut: Dar Sader. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrovandi, Ulise. 1658. Vlyssis Aldrovandi Patricii Bononiensis Dendrologia Natvralis Scilicet Arborvm Historia Libri Duo. Bolonia: Baptista Ferronii. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso X. 2024. Cantigas de Santa María, Códice Rico. Available online: https://rbme.patrimonionacional.es/s/rbme/item/11337#?xywh=-5276%2C-312%2C14295%2C6239 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Alhambra Patronato. 2024. Sala de los Reyes. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/edificios-lugares/sala-de-los-reyes (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Alonso de Herrera, Gabriel. 1513. Obra de Agricultura Copilada de Diuersos Auctores por Gabriel Alonso de Herrera de Mandado del muy Illustre y Reuerendissimo Señor el Cardenal de España Arçobispo de Toledo. Alcalá de Henares: Arnao Guillén de Brocar. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Alfred C. 1961. Acclimatization of Citrus Fruits in the Mediterranean Region. Agricultural History 35: 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1822. El Repostero Famoso, Amigo de los Golosos. Madrid: Imprenta Eusebio Álvarez. [Google Scholar]

- ArchiDATA. 2024. ArchiDATA—Archivio di (retro)Datazioni Lessicali. Available online: https://www.archidata.info/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Ariosto, Ludovico. 1839. L’Orlando Furioso di Ludovico Ariosto. Paris: Lefevre, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarri, Fabrizio. 2022. A Clockwork Orange: Citrus Fruits in Early Modern Philosophy, Science, and Medicine, 1564–1668. Nuncius 37: 255–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, Enrico, and Franco Sacaramuzzi. 1982. Agrumi, Frutta e Uve Nella Firenze di Bartolomeo Bimbi Pittore Mediceo. Firenze: Edizzioni fuori Commerzio. [Google Scholar]

- Banqueri, Joseph Antonio. 1802. Libro de Agricultura. Su Autor el Doctor Excelente Abu Zacaria Iahia Aben Mohamed ben Ahmed En El Awam Sevillano. Madrid: Imprenta Real. Available online: https://archive.org/details/b30457282_0001/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Barbera, Giuseppe. 2007. Parchi, frutteti, giardini e orti nella Conca d’oro di Palermo araba e normanna. Italus Hortus 14: 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, Giuseppe. 2023. Agrumi, Una Storia del Mondo. Milano: Il Saggiatore. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, Giuseppe, and Manlio Speciale. 2015. Meraviglie Botaniche Giardini e Parchi di Palermo. Palermo. Soprintendenza per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali di Palermo, Assessorato dei Beni Cultural e dell’Identità Siciliana. Available online: https://www2.regione.sicilia.it/beniculturali/dirbenicult/info/pubblicazioni/lemappedeltesoro/le_mappe_del_tesoro/volume%2015%20ITA%20low.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Barbera, Giuseppe, Patrizia Boschiero, and Luigi Latini. 2015. Maredolce-La Favara. Premio Internazionale Carlo Scarpa per il Giardino 2015 XXVI. Treviso: Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche-Antiga Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Bellanca, Lina. 2015. Monumenti Normanni. Sollazzi e Giardini. Palermo: Soprintendenza per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali di PalermoAssessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, Rivka. 2012. Botanics and iconography images of the lulav and the etrog. Ars Judaica 8: 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, Rivka. 2023. The Etrog Citron in Art. In The Citron Compendium, The Citron (Etrog) Citrus medica L.: Science and Tradition. Edited by Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and Moshe Bar-Joseph. Cham: Springer, pp. 413–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscotti, Nino. 2016. Storie di Agrumi e Paesaggi I pomi Citrini dello Sperone d’Italia. Foggia: Edizioni del Rosone F. Marasca. [Google Scholar]

- Borgongino, Michele. 2006. Archeobotanica, Reperti Vegetali da Pompei e dal Territorio Vesuviano. Rome: Sopraintendenza Archeologica de Pompeii—“L’Erma” di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Perales, Angel. 2018. La compra de la Casa de la Huerta, sus jardines, búcaros, porcelanas y vidrios de San Juan de Ribera por el duque de Lerma. In Ecos culturales, artísticos y arquitectónicos entre Valencia y el Mediterráneo en Época Moderna. Edited by Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer Lozano and Yolanda Gil. Valencia: Universitat de València, pp. 309–27. [Google Scholar]

- Casares, Manuel, José Tito, and María de los Reyes González-Tejero. 2010. The Moorish Myrtle, History, and Recovery of Alhambra Garden Lost Species (Myrtus communis L. subspecies baetica Casares et Tito). Paper presented at XXVIII International Horticultural Congress on Science and Horticulture for People (IHC2010): International Symposium on Advances in Ornamentals, Landscape and Urban Horticulture, Lisbon, Portugal, August 22; pp. 1237–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cascales, Francisco. 1874. Discursos Históricos de la muy Noble y muy leal Ciudad de Murcia y su Reino por Francisco Cascales. Murcia. Librería de Miguel Tornel y Olmos. Available online: https://bvpb.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=162410 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Cátedra de Patrimonio y Arte Navarro. 2024. El Palacio de Olite. Available online: https://www.unav.edu/web/catedra-patrimonio/itinerarios-visitas/el-palacio-de-olite (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Cavanilles, Antonio Josef. 1795–1797. Observaciones Sobre la Historia Natural, Geografía, Agricultura, Poblaciones y Frutos del Reyno de Valencia. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Charton, Edourd. 1857. Le Grand Bourbon. Magasin Pittoresque 25: 217–18. [Google Scholar]

- ChatGPT. 2024. ChatGPT—Get Instant Answers, Find Creative Inspiration, Learn Something New. Available online: https://openai.com/chatgpt (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Claude. 2024. Claude 3.5 Sonnnet (New). Available online: https://claude.ai/new (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Clément-Mullet, Jean. 1864. Le Livre d’Agriculture d’Ibn al Awam. Paris: Albert L. Hérold. [Google Scholar]

- Commelin, Johannes. 1676. Nederlantze Hesperides. Dat is Oeffening en Gebruik Van de Limoen-en Oranje Boomen Gestelt na den Aardt en Climaat der Nederlanden. Amsterdam: Marcus Doornik. [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba. 2024. Patio de los Naranjos, Mezquita de Córdoba. Available online: https://www.mezquitadecordoba.org/patio-naranjos.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Courboulex, Michel. 1997. Les Agrumes. Paris: Rustica Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Curk, Franck, François Luro, Giovanni Minuto, and Gianni Nieddu. 2022. Les Agrumes du Nord de la Méditerranée. Ajaccio. Éditions Alain Piazzola. Available online: https://www.static.inrae.fr/sites/default/files/agrumesnordmediterranee.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- D’Ottone, Arianna. 2010. Il manoscritto Vaticano Arabo 368 Hadith Bayad wa Riyad. Il codice, il testo, le immagini. Rivista di Storia della Miniatura 14: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ottone, Arianna. 2013. La Storia di Bayad e Riyad (Vat. Ar. 368). Una nuova Edizione e Traduzione. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Daranatz, Jean B. 1922. Un oranger navarrais dit le Grand Connétable. Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos 13: 456–57. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos, Gregorio. 1592. Agricultura de Jardines que Trata de la Manera que se han de Criar, y Conservar las Plantas. Madrid: P. Madrigal. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos, Gregorio. 1620. Agricultura de Jardines que trata de la manera que se han de criar, y conservar las plantas. In Agricultura General. Edited by Alonso De Herrera. Madrid: Viuda de Alonso Martín, pp. 243–71. [Google Scholar]

- De Toledo, Pedro. 1995. Guia de los Perplejos de Maimónides. BNM ms. 10289, 1419–1432. Edited by Moshé Lazar. Madison: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- DeepL. 2024. DeepL Translator. Available online: https://www.deepl.com/translator (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Del Moral, Celia. 2009. Jardines y fuentes en al-Andalus a través de la poesía. Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos, Sección Árabe-Islam 58: 223–49. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, Giovan Battista. 1650a. Phytognomonica Io. Baptiste Portae Neapolitani, Octo Libris Contenta. Rouen: Oiannes Bertelin. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, Giovan Battista. 1650b. Magiae Naturalis. Libri Viginti. Rouen: Oiannes Bertelin. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Donne, Fulvio. 2024. Petrus de Ebulo. De Rebus Siculis Carmen, Edizione Critica. Basilicata University Press. Available online: https://web.unibas.it/bup/evt2/pde/index.html#/imgTxt?d=text_Carmen&p=frontespizio&s=intro&e=interpretative&ce=critical (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Eusko Ikaskuntza. 2014. Palacio Real de Olite. Available online: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/palacio-real-de-olite/ar-154576/# (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- FAO. 2022. The Food and Agriculture Organization. FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Fernández, Joaquín, and Ignacio González. 1991. A propósito de la Agricultura de Jardines de Gregorio de los Ríos. Madrid: Real Jardín Botánico and Ayuntamiento de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, Giovanni Battista. 1646. Hesperides sive de Malorum Aureorum cultura et usu. Libri Quatuor. Rome: Sumptibus Hermanni Scheus. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Donald. 2024. Hesiod in Anthology of Classical Myth. Available online: https://users.pfw.edu/flemingd/Hesiod%20Theogony.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Freedberg, David A. 1992. Ferrari on the Classification of Oranges and Lemons. In Documentary Culture: Florence and Rome from Grand-Duke Ferdinand I to Pope Alexander VII; Papers from a Colloquium Held at the Villa Spelman, Florence, 1990 (Villa Spelman Colloquia 3). Edited by Elizabeth Cropper, Giovanna Perini and Francesco Solinas. Bologna: Nuova Alfa Editoriale, pp. 287–306. Available online: https://arthistory.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/faculty/pdfs/freedberg/Ferrari-on-the-Classification.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Freedberg, David A. 1996. Ferrari and the pregnant lemons of Pietrasanta. In Il Giardino delle Esperidi: Gli agrumi nella storia, nella letteratura e nell’arte. Edited by Alessandro Tagliolini and Margherita Azzi Visentini. Florence: Edifir, pp. 41–58. Available online: https://arthistory.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/faculty/pdfs/freedberg/Ferrari-Pregnant-Lemons.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Freedberg, David A. 2008. Gli agrumi di Giovanni Battista Ferrari. In Miti, Arte e Scienza nella Pomologia Italiana. Edited by Enrico Baldini. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale di Ricerca, pp. 125–56. Available online: https://arthistory.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/faculty/pdfs/freedberg/Ferrari-on-the-Classification.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Frère, Dominique, Elisabeth Dodinet, and Nicolas Garnier. 2012. L’étude interdisciplinaire des parfums anciens au prisme de l’archéologie, la chimie et la botanique: L’exemple de contenus de vases en verre sur noyau d’argile (Sardaigne, VIe-IVe siècle av. J.-C.). ArcheoSciences 36: 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallesio, Georges. 1840. Traité des Citrus. Paris: Louis Pantin. [Google Scholar]

- García-Gómez, Emilio. 1978. El libro de las Banderas de los Campeones de Ibn Saʽīd al-Magribī. Barcelona: Seix Barral. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, Expiración. 1995. Cultivos y espacios agrícolas irrigados en Al-Andalus. In Cara-Barrionuevo, Lorenzo, Malpica-Cuello, Antonio. In Agricultura y Regadío en Al-Andalus, síntesis y Problemas: Actas del Coloquio, Almería, 9 y 10 de junio de 1995. Almería: Instituto de Estudios Almerienses, pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, Expiración, Julia Maria Carabaza, and Jacinto Esteban Hernández-Bermejo. 2021. Flora Agrícola y Forestal de al-Andalus, Vol. 2. Especies leñosas; Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación.

- Gaztelu, Rafael. 1883. Historia de un naranjo. Revista Euskara (Pamplona) 6: 362–71. [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Aliño, Bernardo. 1893. Tratado Completo del Naranjo. Valencia: Librería de Pascual Aguilar. [Google Scholar]

- Glosbe. 2024. Glosbe Diccionario (Árabe Egipcio). Available online: https://glosbe.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Goldschmidt, Eliezer E. 2023. ‘Fruit of the Goodly Trees’: The Talmudic Discourse on the Etrog Citron. In The Citron Compendium, The Citron (Etrog) Citrus medica L.: Science and Tradition. Edited by Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and Moshe Bar-Joseph. Cham: Springer, pp. 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gual-Camarena, Miguel. 2024. Naranjas. Available online: https://www.um.es/lexico-comercio-medieval/index.php/v/lexico/23939/naranjas (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Guerra, Francisco, and María del Carmen Sánchez-Téllez. 1984. El libro de Medicinas Caseras de Fr. Blas de la Madre de Dios: Manila, 1611. Madrid: Comisión Nacional del V Centenario. Ediciones Cultura Hispánica. Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Hallamish, Moshe. 2023. The Etrog Citron in Rabbinic and Kabbalistic Literature. In The Citron Compendium, The Citron (Etrog) Citrus medica L.: Science and Tradition. Edited by Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and Moshe Bar-Joseph. Cham: Springer, pp. 441–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamarneh, Sami Khalaf. 1978. Medicinal plants, therapy and ecology in Al-Ghazzi’s book on agriculture. Studies in the History of Medicine 2: 223–63. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard. 2024. Department of the Classics: Ancient Texts Resources. Available online: https://classics.fas.harvard.edu/ancient-text-resources (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Hernández-Bermejo, J. Esteban, and Expiración García-Sánchez. 1988. Ibn al-ʽAwwām, Kitāb al-Filāḥa. Libro de Agricultura; Edited by Josef Antonio Banqueri. 2 vols, Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, pp. 314–24.

- Hort, Arthur F. 1916a. Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants: Books 1–5. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hort, Arthur F. 1916b. Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants: Books 6–9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Khafāja, Abu Ishaq Ibrahim. 1986. Dīwān. Beirut: Al-Bustāni. [Google Scholar]

- IPGRI (International Plant Genetic Resources Institute). 1999. Descriptors for Citrus (Citrus spp.). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7c4ace4d-ee3a-4e4a-b7d1-b1218898ebf4/content (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Isaac, Erich. 1959a. Influence of Religion on the Spread of Citrus. Science, New Series 129: 179–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac, Erich. 1959b. The Citron in the Mediterranean: A Study in Religious Influences. Economic Geography 35: 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Edith G. 1951. The Gardens in the Decameron Cornice. Proceedings Modern Language Association 66: 505–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Joshua D., Yonit Raz Shalev, Shlomo Cohen, and Elazar Fallik. 2016. Postharvest handling of “etrog” citron (Citrus medica, L.) fruit. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 63: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laca, Luis R. 2003. The Introduction of Cultivated Citrus to Europe via northern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. Economic Botany 57: 502–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langgut, Dafna. 2015. Prestigious fruit trees in ancient Israel: First palynological evidence for growing Juglans regia and Citrus medica. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 62: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langgut, Dafna. 2017. The history of Citrus medica (citron) in the Near East: Botanical remains and ancient art and texts. In AGRUMED: Archaeology and History of Citrus Fruit in the Mediterranean: Acclimatization, Diversifications, Uses [Online]. Edited by Veronique Zech-Mattern and Girolamo Fiorentino. Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gómez, Antonio. 1957. Evolución agraria de la Plana de Castellón. Estudios Geográficos 18: 309–60. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, Carmen. 2024. Jardines Históricos de Madrid. Madrid: Artelibro Editorial. Available online: https://jardineshistoricos.es/jardines-historicos-de-madrid/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Luro, François, Franck Curk, Yann Froelicher, and Patrick Ollitrault. 2017. Recent Insights on Citrus Diversity and Phylogeny. In AGRUMED: Archaeology and History of Citrus Fruit in the Mediterranean: Acclimatization, Diversifications, Uses [Online]. Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775. [Google Scholar]

- Masseti, Marco. 2009. In the gardens of Norman Palermo, Sicily (twelfth century A.D.). Anthropozoologica 44: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monardes, Nicolás. 1551. De secanda vena in pleuritide inter Graecos et Arabes concordia Item eiusdem De rosa et partibus eius, De succi rosarum temperatura, nec non de rosis Persicis, quas Alexandrinas vocant. Antwerp: Ioannem Richardum in Sole Aureo. [Google Scholar]

- Navaggero, Andrés. 1983. Viaje por España: (1524–1526). Translated by Antonio María Fabie. Madrid: Turner. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, and Fidel Garrido. 2018. Peri-urban landscape in Marrakesh: The Menara and other recreational estates (12th-20th centuries). In Almunias. Las fincas de las élites en el Occidente Islámico: Poder, solaz y Producción; Edited by Julio Navarro-Palazón and Carmen Trillo. Granada: CSIC, pp. 195–284. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, and José Miguel Puerta. 2018. The orchards of Marrakesh in written sources: Bustān, buḥayra, ŷanna, rawḍ and agdāl (12th–20th centuries). In Almunias. Las fincas de las élites en el Occidente Islámico: Poder, solaz y Producción; Edited by Julio Navarro-Palazón and Carmen Trillo. Granada: CSIC, pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, Fidel Garrido-Carretero, and José Manuel Torres-Carbonell. 2014. El Agdal de Marrakech. Hidráulica y Producción de Una Finca Real (ss. XII-XX). In Phicaria: Uso y Gestión de Recursos Naturales en Medios Semiáridos del Ámbito Mediterráneo. Mazarrón: Universidad Popular de Mazarrón, pp. 54–115. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, Fidel Garrido, and Íñigo Almel. 2017. The Agdal of Marrakesh (Twelfth to Twentieth Centuries): An Agricultural Space for Caliphs and Sultans. Part I: History. In Muqarnas, An Annual on the Visual Cultures, of the Islamic World. Edited by Gólru Necipoğlu and Maria J. Metzler. Leiden and Boston: J. Brill, vol. 34, pp. 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, Fidel Garrido, and Íñigo Almel. 2018. The Agdal of Marrakesh (Twelfth to Twentieth Centuries): An Agricultural Space for Caliphs and Sultans. Part II: Hydraulics, Architecture and Agriculture. In Muqarnas, An Annual on the Visual Cultures, of the Islamic World. Edited by Gulru Necipoğlu and Maria J. Metzler. Leiden and Boston: J. Brill, vol. 35, pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Palazón, Julio, Fidel Garrido, José Manuel Torres, and Hamid Triki. 2013. Agua, arquitectura y poder en una capital del islam: La finca real del Agdal de Marrakech (ss. XII-XX)—Water, architecture and power in an Islamic capital: The royal country state of the Agdal of Marrakech (12th–20th Centuries). Arqueología de la Arquitectura 10: e007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, José Miguel. 2001. El Casón de Jumilla Líneas de Estudio para un Proyecto Integral de Investigación Histórico-Arqueológica de un Mausoleo Tardorromano. Available online: https://www.um.es/antiguedadycristianismo/martyrium/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/20CASON.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Observatory of Economic Complexity. 2022. The Latest Trade Data of Citrus. Available online: https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/citrus (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Ollitrault, Patrick, Frank Curk, and Robert Krueger. 2020. Citrus taxonomy in Manuel Talon. In The Genus Citrus. Edited by Marco Caruso and Fred Gmitter. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Cordero, Rafael, and Rafael Enrique Hidalgo-Fernández. 2017. 3D Photogrammetry, capacity, filling time and water flow simulation of Cordoba’s Mosque-Cathedral Islamic cistern. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 4: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnoux, Clémence, Alessandra Celant, Sylvie Coubray, Girolamo Fiorentino, and Véronique Zech-Matterne. 2013. The introduction of Citrus to Italy, with reference to the identification problems of seed remains. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 22: 421–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Bazán, Emilia. 1881. Un Viaje de Novios. Madrid: Editorial Pueyo. [Google Scholar]

- PARES. 2024. Albaranorum et Curie. Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, ACA, CANCILLERÍA, Registros, NÚM.71. Available online: https://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/show/4327978 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Pasquarella, Carmelo, and Michele Borgongino. 2005. I dipinti della Sala Pompeiana nella Reggia di Portici. In Cibi e Sapori a Pompei e Dintorni. Edited by Stefani Grete. Pompei: Edizioni Flavius, pp. 156–74. [Google Scholar]

- Patrimonio. 2024. Cantigas de Santa María, Códice Rico. Alfonso X, Rey de Castilla. Available online: https://www.patrimonionacional.es/colecciones-reales/cantigas-de-santa-maria-codice-rico (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Pavesi, Francesco. 2023. Gli Agrumi dei Medici. Vignate: Rotomail. [Google Scholar]

- Piepmeier, Mary. 2018. The Appeal of Lemons: Appearance and Meaning in Mid Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paintings. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pinon, Dominique. 2018. Château-Gaillard (Amboise) et les Orangers de Pacello da Mercogliano: Un Document Inédit. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/44478293/Ch%C3%A2teau_Gaillard_Amboise_et_les_orangers_de_Pacello_da_Mercogliano_un_document_in%C3%A9dit (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Pontano, Giovanni Gioviano. 2024a. Pontano De Hortis Hesperidium (1). Available online: https://mizar.unive.it/poetiditalia/public/testo/testo?codice=PONTANO%7Chesp%7C001 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Pontano, Giovanni Gioviano. 2024b. Pontano De Hortis Hesperidium (2). Available online: https://mizar.unive.it/poetiditalia/public/testo/testo?codice=PONTANO%7Chesp%7C002 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- POWO. 2024. Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Racioppi, Pier Paolo. 2024a. “Zisa” in Discover Islamic Art, Museum with No Frontiers, 2024. Available online: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;it;Mon01;1;es (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Racioppi, Pier Paolo. 2024b. Mosaici Della Sala di Ruggero nel Palazzo Reale (o dei Normanni). Available online: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;it;Mon01;17;it&cp (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Rackham, Harris. 1945. Pliny, Natural History, Volume IV: Books 12–16. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- RAE. 2024. Banco de Datos CORDE. Available online: https://www.rae.es/banco-de-datos/corde (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Raimondo, Francesco Maria, Luigi Cornara, Pietro Mazzola, and Antonio Smeriglio. 2015. Le lumie di Sicilia: Note Storiche e botaniche. Quaderni di Botanica Ambientale e Applicata 26: 43–50. Available online: https://www.centroplantapalermo.org/quaderni/26_043-050.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Reina, Manuel-Francisco. 2007. Antología de la Poesía Andalusí. Madrid: Edaf. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, John M. 1930. The Decameron of Giovanni Bocaccio. Translated by John M. Rigg. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, vol. 1, Available online: http://dbooks.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/books/PDFs/502235914.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Ríos, Segundo, Vanessa Martínez-Francés, Pedro Moya, and Roberto Poyatos. 2024. La colección de lirios (Iris L. Iridaceae) de la Estación Biológica de Torretes—Jardín Botánico de la Universidad de Alicante: Iridario “Christine Lomer”. Bouteloua 37: 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Risso, Antoine, and Pierre Antoine Poiteau. 1818–1822. Histoire Naturelle des Orangers. Paris: Impr. de Mme Hérissant Le Doux. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1512210b# (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Rivera, Diego, Antonio Bermudez, Concepción Obón, Francisco Alcaraz, Segundo Ríos, Jorge Sánchez-Balibrea, P. Pablo Ferrer-Gallego, and Robert Krueger. 2022. Analysis of ‘Marrakesh limetta’ (Citrus × limon var. limetta (Risso) Ollitrault, Curk & R. Krueger) horticultural history and relationships with limes and lemons. Scientia Horticulturae 293: 110688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Diego, Concepción Obón, Francisco Alcaraz, Emilio Laguna, and Dennis Johnson. 2019. Date-palm (Phoenix, Arecaceae) iconography in coins from the Mediterranean and West Asia (485 BC–1189 AD). Journal of Cultural Heritage 37: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Diego, Concepción Obón, Segundo Ríos, Caridad Selma, Francisco Méndez, Alonso Verde, and Francisco Cano. 1998. Las Variedades Tradicionales de Frutales de la Cuenca del Río Segura. Catálogo Etnobotánico. Cítricos, Frutos Carnosos y Vides. Murcia: Diego Marín. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, Diego, Javier Abellán, Diego-José Rivera-Obón, José Antonio Palazón, Manuel Martínez-Rico, Francisco Alcaraz, Dennis Johnson, Concepción Obón, and Pedro A. Sosa. 2023. Expanding dendrochronology to palms: A Bayesian approach to the visual estimate of a palm tree age in urban and natural spaces. Current Plant Biology 35: 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Ana Margarida Duarte. 2017. The Role of Portuguese Gardens in the Development of Horticultural and Botanical Expertise on Oranges. Journal of Early Modern Studies 6: 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Ana Margarida Duarte. 2023. Early modern water-saving strategies for citrus growing in Greater Spain: Theory versus Practice. In Pragmatismo e Ilusión: El Agua y la Gestión del Espacio y Territorio en Aranjuez y otros Sitios Cortesanos (Siglos XVI-XIX). Edited by Félix Labrador Arroyo and Magdalena Merlos Romero. Madrid: Sílex Universidad/Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ruas, Marie-Pierre, Perrine Mane, Carole Puig, Charlotte Hallavant, Bénédicte Pradat, Mohamed Ouerfelli, Jérôme Ros, Danièle Alexandre-Bidon, and Aline Durand. 2015. Regard pluriel sur les plantes de l’héritage arabo-islamique en France médiévale. In Héritages Arabo-Islamiques dans l’Europe Méditerranéenne. Edited by Richarte Catherine, Gayraud Roland-Pierre et Poisson and Jean-Michel. Paris: La Découverte-INRAP, pp. 347–76. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01570480/document (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ruas, Marie-Pierre, Perrine Mane, Charlotte Hallavant, and Michel Lemoine. 2017. Citrus Fruits in historical France: Written sources, iconographic and plant remains. In AGRUMED: Archaeology and History of Citrus Fruit in the Mediterranean: Acclimatization, Diversifications, Uses [Online]. Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775. Available online: https://books.openedition.org/pcjb/2243 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Sánchez, Miguel. 1881. Historia Primitiva y Exacta del Monasterio del Escorial la más rica en Detalles de Cuantas se han Publicado/Escrita el siglo XVI por el Padre Fray José de Sigüenza. Sevilla. Manuel Tello y García. Available online: https://bibliotecafloridablanca.um.es/bibliotecafloridablanca/handle/11169/7078 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Saunt, James. 1990. Citrus Varieties of the World. Norwich: Sinclair International Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Savastano, Luigi Salvatore. 1883. Le Varietà degli Agrumi del Napoletano. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uga1.32108005555506&seq=39 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Simón, Elisa. 2020. Pinturas de la sala de los Reyes—La Alhambra, Granada. Available online: https://andalfarad.com/pinturas-de-la-sala-de-los-reyes-la-alhambra-granada/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Soriano, Jerónimo. 1598. Libro de Experimentos Médicos, Fáciles y Verdaderos Recopilados de Grauissimos Autores por el Doctor Hieronymo Soriano. Zaragoza: Juan Perez de Valdivielso. [Google Scholar]

- Sottile, Francesco, Maria Beatrice Del Signore, and Ettore Barone. 2019. Ornacitrus: Citrus plants (Citrus spp.) as ornamentals. Folia Horticulturae 31: 239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampella, Pablo C., Gustavo Delucchi, Héctor A. Keller, and Julio A. Hurrell. 2014. Etnobotánica de Citrus reticulata (Rutaceae, Aurantioideae) naturalizada en la Argentina. Bonplandia 23: 151–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taburet-Delahaye, Élisabeth, and Béatrice de Chancel-Bardelot. 2018. The Lady and the Unicorn. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux—Grand Palais. [Google Scholar]

- Tasso, Torquato. 1822. Gerusaleme Liberata di Torquato Tasso. London: C. Corral. Available online: https://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000106004 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Tilly, Georges. 2020. Un Manifeste Posthume de l’humanisme Aragonais: Le De hortis Hesperidum de Giovanni Pontano. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Rouen Normandie, Rouen, France. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-03197923 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Tintori, Giorgio, and Sergio Tintori. 2000. Gli Agrumi Ornamentali Consigli Dalla Tradizione dei Contadini Giardinieri. Bologna: Calderini Edagricole—Oscar Tintori. [Google Scholar]

- Tintori, Oscar. 2024. Oscar Tintori, Gli Agrumi in Toscana. Available online: https://www.oscartintori.it/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Tito-Rojo, José, and Manuel Casares-Porcel. 2011. El Jardín Hispanomusulmán: Los Jardines de al-Andalus y su Herencia. Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- TLFi. 2024. Trésor de la Langue Française Informatisé. Nancy: ATILF—CNRS & Université de Lorraine. Available online: http://atilf.atilf.fr/tlf.htm (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Tolkowsky, S. 1938. Hesperides a History of the Culture and Use of Citrus Fruits. London: John Bale Sons & Cpurnou. [Google Scholar]

- Trisciuzzi, Nicola. 2009. Scelta del materiale di propagazione. In Quaderno Agrumicoltura. Edited by Carmelo Memmone. Locorotondo: Centro di Ricerca e Sperimentazione in Agricoltura “Basile Caramia”, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. 2024a. William Saunders: A Monumental Figure in USDA. Available online: https://agresearchmag.ars.usda.gov/2013/sep/saunders/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- USDA. 2024b. Citrus: World Markets and Trade. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/citrus.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Valor, Magdalena. 2020. La Almunia de La Buhayra de Sevilla a través de la Crónica de Al-Salat. Available online: https://2020_Almunias._Tuetano20200402-27303-ein6k3-libre.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Vaticana. 2024. Manuscript—Vat.ar.368. Available online: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.ar.368 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Vega-Carpio, Lope de. 1602. Arcadia, Prosas y Versos. Barcelona. Sebastián de Comellas. Available online: https://cervantes.bne.es/es/su-biblioteca/arcadia-prosas-y-versos (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Venuto, Antonino. 1516. Notensis de Agricoltura opusculum. Neaples: Sigismondo Mayer Alemanno. [Google Scholar]

- VoDIM. 2024. Stazione Lessicografica VoDIM. Available online: https://www.stazionelessicografica.it/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Volkamer, Johan C. 1708. Nürnbergische Hesperides. Nüremberg: Johan Andreas Endters. [Google Scholar]

- Wearn, James A., and David J. Mabberley. 2016. Citrus and Orangeries in Northern Europe. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 33: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Edgard. 1994. Jardins et Palais dans Le Coran et les Mille et Une Nuits. Sharq Al-Andalus 10–11: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zytaruk, Maria. 2011. Cabinets of Curiosities and the Organization of Knowledge. University of Toronto Quarterly 80: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citrus Taxa | English | Arabic | Spanish | French | Italian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent species | |||||

| Citrus medica L. | Citron 14 | Utruj 3 c. 1150, Utrujj 15, Utruj 16, Walaitiraj, Energ, Tufāḥ al-yamānī 3 c. 1150 | Cidros 10, Cidras 21 since early 15th century | Cédratier, Citronnier 13 early 19th century | Cedro 11,12,13 11nd cent |

| Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. | Pummelo 14, Shaddock 20 | Zanbū῾, Zambua 15, Bastanbūa, Zambūʽ, Raybūʽ 3 c. 1150 | Zimboas 21, Toronja, 6,14,21 late 16th century | Pamplemousse, Pompoleon 13,14 early 17th century | Pompelone, Pompelmo 12,22 early 19th century |

| Citrus hystrix DC. | Makrut lime, Combava 14 | none | none | Combava 13 early 19th century | Papeda 12 early 19th century |

| Citrus reticulata Blanco | Wild mandarin | none | Mandarino 23 early 21st cent | none | Mandarino vero 12 early 21st cent |

| Hybrids C. medica × C. máxima | |||||

| Citrus × lumia Risso | Lumia | Astunbūtī 15, Bastanūa 3 c. 1150 (for “Pompia” hybrids) | Poncil | Lumie rhegine, Limettier Pomme d’Adam 13 early 19th century | Pomo d’Adamo 12 16th cent |

| Hybrids C. medica × C. hystrix | |||||

| Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Merr. | Lime 14 | Līm 15, Allaymun 3,4 c. 1100, Banzahir, Luumi 16 | Limas, Limones 6,21 late 16th century | Limettier 13 20th century | Limoncello, Limetta acida 11,12,22 16th cent |

| Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Merr. | Adam’s Apple Lime | Līm 15 3 c. 1150 | Limonier à fruit rond 13 early 19th century | Spongino, Pomo d’Adamo 12,12 16th century | |

| Hybrids C. medica × C. reticulata × C. máxima | |||||

| Citrus × limon (L.) Osbeck var. limon | Lemon 14,20 | Laymūn 3,15, Lāmūn 3 c. 1150 | Limones, 6,10,21 since early 15th century | Citronnier, Limonier 13 early 19th century | Limone11,12 16th century |

| Citrus × limon (L.) Osbeck var. limetta (Risso) Ollitrault, Curk and R.Krueger | Limetta | Laymus 3 c. 1150, Līm 15 c. 1300 | Lima agria, Lima dulce 16th 19th century | Limettier 13 early 19th century | Lima, Limetta, Limetta dolce, Limetta acida 11,12,22 17th century |

| Citrus × limettioides Tanaka | Palestine lime 12 | Līm, 15,16,18 c. 1300, Limun helu 16 late 20th century | Lima dulce, Limetero árabe 16,18 late 19th century | Lime douce de Palestine early 21st century | Limetta palestina, Limetta dolce Indiana 12 20th century |

| Citrus × limonimedica Lush. | Citron lemon | Laymūn 15 c. 1300 | Ponciles 1,6 late 16th century | Limonier ponzin 13 early 19th century | Ponzino, Cedrato, Limone cedrato 12, 22 late 16th cent |

| Citrus × mellarosa Risso | Mellarosa lemon 12 | Astunbūtī 15 c. 1300 | Melarrosa 16 late 19th century | Bergamote, Melarose 13 early 19th century | Mela rosa, Melarosa 11, 12,22 17th century |

| Citrus × bergamia (Risso) Risso and Poit. | Bergamot 14 | Astunbūtī 3,15 c. 1150 | Bergamota 7,16 early 19th century | Bergamotier 13 early 19th century | Bergamotto 11,12,13,22 17th century |

| Hybrids C. reticulata × C. máxima | |||||

| Citrus × aurantium L. (sweet grafted on bitter) | Nāranj 3 c. 1150 15 c. 1300, Safāriya 3 c. 1150? | Cajeles, Naranjos zajaries, 2,10 early 17th century | - | Melangolo dolce 22 19th century | |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. sinensis L. | Sweet orange 14 | Walnaarnj 3 c. 1150 | Naranjos, Naranxos, 6 late 13th century | Oranger à fruits doux 13 early 19th century | Portogallo di Spagna, Arancio dolce 11,12,22 16th cent |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. aurantium | Seville orange 14 | Nāranj 3,15. Walnaarnj 3 c. 1150 | Naranjo amargo 16 | Bigaradier 13 early 19th century | Arancio forte, Melarancio, Melangolo 11,12,22 11th century |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. clementina 5 | Clementine 14 | Kalamintina 17 early 20th century | Clementina 9 early 20th century | Clémentinier 13 early 20th century | Clementine 12 late 19th century |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. deliciosa 5 | Mediterranean mandarin 14 | Burtuqal almandri, Safandaa 17 early 20th century | Mandarina 8 late 19th century | Mandarinier 13 early 20th century | Mandarino, Mandarino commune 12,22 early 19th century |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. paradisi 5 | Grapefruit 14 | Zanbū῾ 15 c. 1300? | Pomelo 14 late 19th century | Pamplemousse, Pomelo 13,14 early 20th cent | Pompelmo 12 early 19th century 20 17th century |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. myrtifolia | Chinotto 14 | Nāranj 15 c. 1300 | Petit chinois 13 early 19th century | Chinotto, Melangolo a foglia di myrto 11,12,13,22 16th century | |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. balearica Risso and Poit. | Acidless orange 14 | Burtuqal min ghayr himd 17 early 21st century | Naranja imperial, Naranja sucreña 14 early 20th century | Orange de Nice, Oranger de Majorque 13,14 early 19th century | Vaniglia, Arancio de Maiorca 13 early 19th century |

| Citrus × aurantium L. var. hierochuntium | Blood orange 14 | Nāranja 19 12th century Alburtuqal almaltyu 17 early 21st century | Naranja sanguina 14 early 20th century | Oranger de Malte 13 early 19th century | Arancio sanguigno 13 early 17th century |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera, D.; Navarro, J.; Camarero, I.; Valera, J.; Rivera-Obón, D.-J.; Obón, C. Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens. Arts 2024, 13, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13060176

Rivera D, Navarro J, Camarero I, Valera J, Rivera-Obón D-J, Obón C. Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens. Arts. 2024; 13(6):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13060176

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera, Diego, Julio Navarro, Inmaculada Camarero, Javier Valera, Diego-José Rivera-Obón, and Concepción Obón. 2024. "Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens" Arts 13, no. 6: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13060176

APA StyleRivera, D., Navarro, J., Camarero, I., Valera, J., Rivera-Obón, D.-J., & Obón, C. (2024). Citrus: From Symbolism to Sensuality—Exploring Luxury and Extravagance in Western Muslim Bustān and European Renaissance Gardens. Arts, 13(6), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13060176