Rock Varnish Dating, Surface Features and Archaeological Controversies in the North American Desert West

Abstract

1. Introduction

Rock Varnish

2. Background and Methods: Rock Varnish Dating Techniques, Sampling Procedures, and Ethnographic Analyses

2.1. VML Dating

“twelve wet event dark layers and thirteen dry event lighter layers … bracket the period from 300 yrs cal BP to 12,500 yrs cal BP. The lengths of the intervals between wet events vary from 250 to 1800 years, with an average of 970—roughly 1000 years. The resulting correlated VML ages are certainly not as precise as radiocarbon ages, but they are adequate for age assignment to the broad time periods comprising the regional cultural historical sequence”.(Whitley 2013, p. 4)

2.2. Lead-Profile Dating

2.3. CR Dating

2.4. Methods of Dating Surface Features in Desert Pavements

2.4.1. Time Lag in Desert Pavement Regeneration

2.4.2. Time Lag in the Initiation of Revarnishing

2.5. Methodological Principles of Ethnographic Analysis

Linguistic and Ethnic Group Histories: Background and Methods

“has not wiped out all Indian practices. Acculturation has consisted primarily of modifications of those patterns necessary to adjust to rural white culture … The Shoshoni retain, however, many practices and beliefs pertaining to kinship relations, child-rearing, shamanism, supernatural power and magic”.

“The rule of thumb (derived from the study of languages with hundreds of years of written documentation…) is that after about 2000 years, language changes tend to have obscured the clear sorts of correspondences [for grouping language families and detecting borrowing, while] … After 5000 years there are few [such] correspondences”.

“Glottochronology uses the percentage of shared ‘cognates’ between languages to calculate divergence times by assuming a constant rate of lexical replacement or ‘glottoclock’. Cognates are words inferred to have a common historical origin because of systematic sound correspondences and clear similarities in form and meaning. Despite some initial enthusiasm, the method has been heavily criticised and is now largely discredited. Criticisms of glottochronology, and distance-based [statistical] methods in general, tend to fall into four main categories: first, by summarizing cognate data into percentage scores, much of the information in the discrete character data is lost, greatly reducing the power of the method to reconstruct evolutionary history accurately; second, the clustering methods employed tend to produce inaccurate trees when lineages evolve at different rates, grouping together languages that evolve slowly rather than languages that share a recent common ancestor; third, substantial borrowing of lexical items between languages makes tree-based methods inappropriate; and fourth, the assumption of a strict glottoclock rarely holds, making date estimates unreliable. For these reasons historical linguists have generally abandoned efforts to estimate absolute ages”.

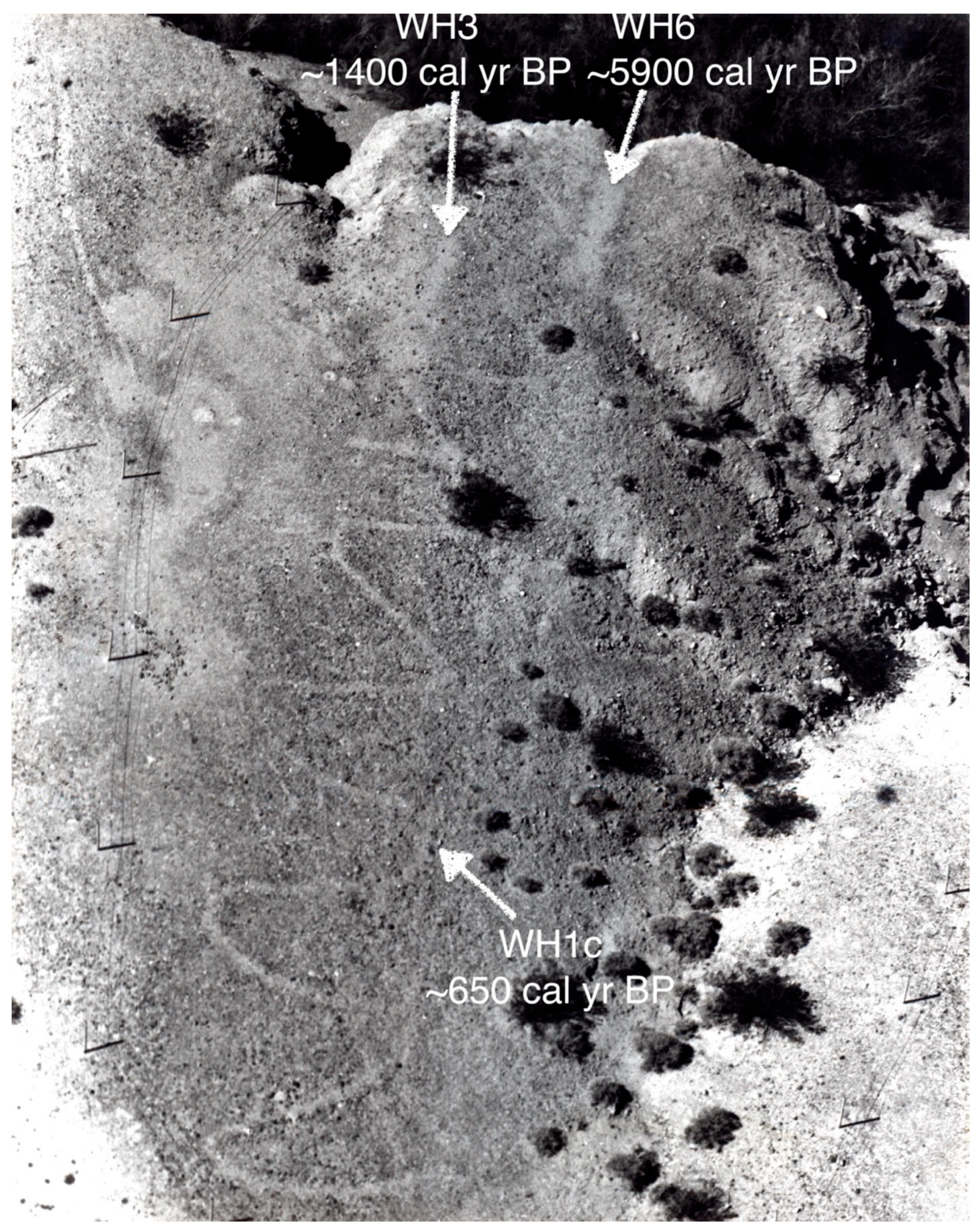

3. Age of the Colorado River Intaglios

3.1. VML and CR Ages on Intaglios

3.2. Implications of the Intaglio Ages

4. Age, Origin, and Meaning of the Topock Maze

The process of gathering [gravel] was to rake these fragments of [surface] stone into windrows and haul them by wagon to a pile where convenient to load into a car when needed … Indian labor was used very successfully for this as well as for labor about the caisson.

The Mohave Indians near-by have utilized the area so marked, in recent years, as a maze into which to lure and escape evil spirits, for it is believed that by running in and out through one of the immense labyrinths one haunted with a dread may bewilder the spirits occasioning it, and thus elude them.

Early settlers claim that when the Santa Fe R.R. [originally the Atlantic and Pacific] was built (1893) several acres of the lower end were gathered up for ballast for the RR tracks and that a large shrine at the lower [i.e., northern] end on the River Trail was at the same time destroyed. This shrine contained potsherds and artifacts. In the assemblage was [sic] stone axes and some turquoise jewelry. The informant F.M. Kelley of Needles said that near the base toward the river there was previous to this a large intaglio human figure similar to those at [another site]. Mohaves in early days disclaim having built the maze and that it had always been there but that in the old days they used it for ceremonial purposes occasionally.

4.1. VML and Lead-Profile Dating of the Topock Maze

4.2. Function, Meaning and Symbolism of the Topock Maze

“interviewees suggested that stories or songs telling of its construction were present in the Mojave culture, but these stories are only told in some family lines and are not known by everyone … Other interviews in the 20th Century suggested that the Mojave would use the Maze to purify themselves by running through the Maze or by navigating through the Maze without walking over a windrow, leaving evil spirits or ghosts in the Maze, or that the purpose of the Maze is to help the deceased atone for their life before fully passing to the afterlife”.

“The scalper, being a shaman, has power over this disease and can cure people afflicted with it. The scalps … bring beneficial power to the tribe after they have been tamed. The scalper, then, contributes to tribal welfare by his power to tame the scalps and to cure the “enemy sickness.” He also directs one of the most important Mohave ceremonies [the Mourning Ceremony]. Scalper is one of the most important religious statuses”.

“When the scalper returns with the war party he turns the scalps over to the kwaxot, or custodian of the scalps, who is the principal Mohave religious leader. The custodian of the scalps prepares a great celebration in honor of the returning warriors … After the feast the custodian of the scalps places them in large pottery ollas for safekeeping”.

The female captives are given by the custodian of the scalps to some of the old men who need wives. Young men are afraid to take these women because of the ‘enemy sickness’ but the old men are glad to have them since they have lived a long time and do not have long to live under any circumstances.

“That other sharp, high mountain, down there near the Needles, in Arizona, was also a spirit mountain; that was where the Mojaves went when they died. (It was the Mojave Elysium)”.

The entrance to the “land of the dead” (cilia’yt) is somewhere near Needles, California, almost by the Colorado River on the Arizona side. There is something that looks like a big invisible “wash” containing a big invisible shed [i.e., ritual ramada] near a place called Ahatcku-pi’lyk, which is but a few feet [sic] from the land of the dead.

“Following cremation, the soul remained near the site of the [funeral] pyre four days. At the end of this time the soul changed into a ghost which was then able to see the road to the afterworld. This started at Topock and ran south into the desert in the neighborhood of the Bill Williams River”.(Fathauer 1951b, p. 605; emphasis added)

“When rumors spread that a person has died as a result of evil practices, the members of their family send a bona fide sorcerer to visit the land of the dead to see if the deceased’s soul has arrived there. If the messenger does not encounter this soul, it is ipso facto proof that the soul is being held captive somewhere by the sorcerer”.

The ghost doctor also could take people to the spirit world, although he did not encourage this because it was dangerous. He warned the person who wished to see a dead relative: ‘Be careful. If our hands slip apart, I’ll have to look for you all night. If I don’t find you before morning we will both be stuck here.’ The shaman and the person who was to accompany him dressed in their best clothes and painted themselves. About twilight they built a small brush shelter and then lay down to sleep with their hands clasped. In less than an hour they were transported to the afterworld. The ghost doctor knew exactly where the person’s family was, so they went directly there

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An additional experimental technique, AMS-Weathering Rind Organics dating (Dorn et al. 1986), was developed and applied archaeologically in the 1990s (e.g., Whitley and Dorn 1993). This was predicated on the assumption that rock varnish coatings were closed systems that were not subject to contamination by older or younger organic material, as was repeatedly emphasized in publications where it was employed. This assumption proved invalid, and the technique was withdrawn (Dorn 1996, 1997). Despite this notification, a subsequent, widely promoted controversy resulted, including accusations of scientific misconduct (Beck et al. 1998). The scientific basis of this controversy, the three separate investigations concluding that no misconduct occurred on the part of the accused, and the legal defamation case that resulted are covered in detail in Whitley (2009, 2013). Here it is adequate to emphasize that the AMS-WRO controversy had no implications for the efficacy or utility of the dating techniques discussed in this paper. |

| 2 | The three dating methods used here focus on microdepressions where varnish first formed, as revealed by the oldest VML sequence. Recent papers have instead attempted to use pXRF to date revarnished petroglyph grooves (Macholdt et al. 2019; Andreae et al. 2020, 2023; Andreae and Andreae 2022; Pingitore and Lytle 2003; Lytle et al. 2008, 2011; A. K. Rogers 2010; J. A. Johnson 2018; Guagnin et al. 2025). In contrast with VML, which provides the closest minimum age, pXRF indescriminately measures some varnish, but mostly non-varnish chemical materials in its analysis of an 8 mm spot size without regard to time lags, with the goal of measuring Mn accumulation, but not knowing if the Mn being analyzed is from varnish or other surface materials. We note that Bard (1979) demonstrated decades ago that the accumulation of Mn in rock varnish is not systematically related to sample age, a conclusion that has not been addressed let alone resolved by proponents of the pXRF approach. Dorn and Whitley (Forthcoming) present a more detailed analysis of these methodological issues. |

| 3 | The focus of von Werlhof et al. (1995) was to present the experimental AMS-WRO results. The authors at that time cautioned that “These [AMS-WRO] results must, however, be placed under the cloud of uncertainty that hangs over the entire field of AMS dating of rock art: the untested assumption surrounding contemporaneity of organics in a surface context” (von Werlhof et al. 1995, p. 257). Since von Werlhof et al. (1995) also published uncalibrated (K + Ca)/Ti ratios for comparison, these were calibrated for this study to provide additional minimum-limiting chronometric ages, but the AMS-WRO ages were not used in the calibration. See Bamforth and Dorn (1988) for details on the calibration employed for these CR ages. |

References

- Adelsberger, Katherine A., and Jennifer R. Smith. 2009. Desert pavement development and landscape stability on the Eastern Libyan Plateau, Egypt. Geomorphology 107: 178–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelsberger, Katherine A., Jennifer R. Smith, Shannon P. McPherron, Harold L. Dibble, Deborah I. Olszewski, Utsav A. Schurmans, and Laurent Chiotti. 2013. Desert pavement disturbance and artifact taphonomy: A case study from the eastern Libyan plateau, Egypt. Geoarchaeology 28: 112–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AECOM. 2010. Draft Environmental Impact Report for the Topock Compressor Station Groundwater Remediation Project. Sacramento: California Department of Toxic Substance Control. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, Richard V. N., and Heidi Roberts. 2001. Desert pavement and buried archaeological features in the Arid West: A case study from southern Arizona. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 23: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Andreae, Meinrat O., Abdullah Al-Amri, Tracey W. Andreae, Alan Garfinkel, Gerald Haug, Klaus Peter Jochum, Brigitte Stoll, and Ulrike Weis. 2020. Geochemical studies on rock varnish and petroglyphs in the Owens and Rose Valleys, California. PLoS ONE 15: e0235421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, Meinrat O., and Tracey W. Andreae. 2022. Archaeometric studies on rock art at four sites in the northeastern Great Basin of North America. PLoS ONE 17: e0263189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, Meinrat O., Tracey W. Andreae, Julie E. Francis, and Lawrence L. Loendorf. 2023. Age estimates for the rock art at the Rocky Ridge site (Utah) based on archaeological and archaeometric evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 48: 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Quentin D., Andrew Meade, Chris Venditti, Simon J. Greenhill, and Mark Pagel. 2008. Languages evolve in punctuational bursts. Science 319: 588–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, Molly, Andrew Garrett, Michael J. Houser, and Maziar Toosarvandani. 2013. Descent and diffusion in language diversification: A study of Western Numic dialectology. International Journal of American Linguistics 79: 445–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baied, Carlos A., and Carolina Somonte. 2013. Mid-Holocene geochronology, palaeoenvironments, and occupational dynamics at Quebrada de Amaicha, Tucuman, Argentina. Quaternary International 299: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, J. T., and Troy L. Pewe. 1979. Origin and rate of desert pavement formation—A progress report. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy Science 14: 84. [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth, Douglas B. 1997. Cation-ratio dating and archaeological research design: Response to Harry. American Antiquity 62: 121–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamforth, Douglas B., and Ronald I. Dorn. 1988. On the nature and antiquity of the Manix Lake Lithic Industry. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 10: 209–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, James C. 1979. The Development of a Patination Dating Technique for Great Basin Petroglyphs Utilizing Neutron Activation and X-Ray Fluorescence Analyses. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Warren, Douglas J. Donahue, A. Timothy Jull, G. Burr, W. S. Broecker, G. Bonani, I. Hajdas, and E. Malotki. 1998. Ambiguities in direct dating of rock surfaces using radiocarbon measurements. Science 280: 2132–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, Robert L., and Martin A. Baumhoff. 1982. The Numic spread: Great Basin cultures in competition. American Antiquity 47: 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billo, Evelyn, Robert Mark, and Donald E. Weaver. 2013. Sears Point Rock Art Recording Project, Arizona, USA. American Indian Rock Art 40: 1283–302. [Google Scholar]

- BLM. 2012. Cultural and Historic Properties Management Plan (CHPMP), Topock Remediation Project. Lake Havasu: BLM, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Maurice. 1986. From Blessing to Violence: History and Ideology in the Circumcision Ritual of the Merina of Madagascar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Maurice. 1992. Prey into Hunter: The Politics of Religious Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, John G. 1889. Notes on the cosmogony and theogony of the Mojave Indians of the Rio Colorado, Arizona. The Journal of American Folklore 2: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broecker, Wallace S., and Tanzhou Liu. 2001. Rock varnish: Recorder of desert wetness? GSA TODAY 11: 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, Thomas., Jamie Trammell, Scott Bassett, Todd Caldwell, D. Sabol, R. Schumer, S. Bacon, S. Baker, G. Dalldorf, and M. Dennis. 2012. LanDPro: Landscape Dynamics Program. Reno: Desert Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Burford, Euen P., Marena Fomina, and Geoffrey M. Gadd. 2003. Fungal involvement in bioweathering and biotransformation of rocks and minerals. Mineralogical Magazine 67: 1127–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, Todd, Eric McDonald, Steven Bacon, Rina Schumer, and Thomas Bullard. 2011. Cleared Circles: Anthropogenic or Biogenic? Use of Non-invasive Geophysical Techniques to Determine Origin. In Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems. Houston: Society of Exploration Geophysicists, p. 581. [Google Scholar]

- Candelone, Jean-Pierre, Sungmin Hong, Christian Pellone, and Claude F. Boutron. 1995. Post-Industrial Revolution changes in large-scale atmospheric pollution of the northern hemisphere by heavy metals as documented in central Greenland snow and ice. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 100: 16605–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonelli, Juan Pablo, and Mirian M. Collantes. 2019. Early Human Occupations in the Valleys of Northwestern Argentina: Contributions to Dating by the Varnish Micro-Laminations Technique. In Advances in Geomorphology and Quaternary Studies in Argentina. Edited by Pablo Bouza, Jorge Rabassa and Andrés Bilmes. Amsterdam: Springer, pp. 262–82. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Harry. 1992. Earthen Art: Geoglyphs and Rock Alignments—The Mysterious Prehistoric Ground Drawings Found in the Deserts of Southwestern United States. Privately printed. [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny, Niccole V., Russell Kaldenberg, Judith Reed, David S. Whitley, Joseph M. Simon, and Ronald I. Dorn. 2006. A new strategy for analyzing the chronometry of constructed rock features in deserts. Geoarchaeology 21: 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddha, Amritpal Singh, Anupam Sharma, Narendra Kumar Singh, Amreen Shamsad, and Monisha Banerjee. 2024. Biotic-abiotic mingle in rock varnish formation: A new perspective. Chemical Geology 648: 121961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Edward. 1908. The North American Indian. Norwood: Plimpton Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, George. 1935. Sexual Life of the Mohave Indians: An Interpretation in Terms of Social Psychology. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, George. 1937a. L’envoûtement chez les Indiens Mohave. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 29: 405–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, George. 1937b. Mohave Soul Concepts. American Anthropologist 39: 417–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, George. 1961. Mohave Ethnopsychiatry and Suicide: The Psychiatric Knowledge and the Psychic Disturbances of an Indian Tribe. Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Jared M., and Peter Bellwood. 2003. Farmers and their languages: The first expansions. Science 300: 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietze, Michael, and Arno Kleber. 2012. Contribution of lateral processes to stone pavement formation in deserts inferred from clast orientation patterns. Geomorphology 139: 172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 1983. Cation-ratio dating: A new rock varnish age-determination technique. Quaternary Research 20: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 1994. Dating petroglyphs with a 3-tier rock varnish approach. In New Light on Old Art: Advances in Hunterer-Gatherer Rock Art Research. Edited by D. S. Whitley and L. Loendorf. UCLA Institute for Archaeology Monograph Series, no. 36. Los Angeles: University of California, pp. 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 1996. Uncertainties in the radiocarbon dating of organics associated with rock varnish: A plea for caution. Physical Geography 17: 585–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 1997. Constraining the age of the Coa Valley (Portugal) engravings with 14C. Antiquity 71: 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 1998. Rock Coatings. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2001. Chronometric Techniques—Rock Engravings. In Handbook of Rock Art Research. Edited by David S. Whitley. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 167–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2010. Debris flows from small catchments of the Ma Ha Tuak Range, Metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona. Geomorphology 120: 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2014. Chronology of rock falls and slides in a desert mountain range: Case study from the Sonoran Desert in south-central Arizona. Geomorphology 223: 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2016. Identification of debris-flow hazards in warm deserts through analyzing past occurrences: Case study in South Mountain, Sonoran Desert, USA. Geomorphology 273: 269–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2019. Anthropogenic interactions with rock varnish. In Biogeochemical Cycles: Anthropogenic and Ecological Drivers. Edited by Katerina Dontsova, Zsuzsanna Balogh-Brunstad and Gaël Le Roux. Washington: American Geophysical Union, Geophysical Monograph, vol. 251, pp. 267–83. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2024. Rock varnish revisited. Progress in Physical Geography 4: 389–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I. 2025. Revisiting the importance of clay minerals in rock varnish. American Mineralogist 110: 1341–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., and David H. Krinsley. 1991. Cation-leaching sites in rock varnish. Geology 19: 1077–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., and David S. Whitley. 1983. Cation-ratio dating of petroglyphs from the Western United States, North America. Nature 302: 816–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., and David S. Whitley. 1984. Chronometric and relative age-determination of petroglyphs in the Western United States. Annals, Association of American Geographers 74: 308–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., and David S. Whitley. Forthcoming. Why pXRF Petroglyph Dating Does Not Work. Paper in Preparation.

- Dorn, Ronald I., and Theodore M. Oberlander. 1981. Rock varnish origin, characteristics, and usage. Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie 25: 420–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., Douglas B. Bamforth, Thomas A. Cahill, J. C. Dohrenwend, B. D. Turrin, A. J. T. Jull, A. Long, M. E. Macko, E. B. Weil, D. S. Whitley, and et al. 1986. Cation-ratio and accelerator-radiocarbon dating of rock varnish on archaeological artifacts and landforms in the Mojave Desert, eastern California. Science 223: 730–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Ronald I., Gordon Moore, Eduardo O. Pagán, Todd W. Bostwick, Max King, and Paul Ostapuk. 2012. Assessing early Spanish explorer routes through authentication of rock inscriptions. Professional Geographer 64: 415–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Ronald I., Thomas A. Cahill, Robert A. Eldred, Thomas E. Gill, Bruce H. Kusko, Andrew J. Bach, and Deborah L. Elliott-Fisk. 1990. Dating rock varnishes by the cation ratio method with PIXE, ICP, and the electron microprobe. International Journal of PIXE 1: 157–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, Phillip. 1941. Culture Element Distributions: XVII: Yuman-Piman. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, Eric. 1994. “How” and “Thus” in UA Cupan and Yuman: A case of areal influence. In Report 8 Survey of California and Other Indian Languages. Proceedings of the Meeting of the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas and the Hokan Penutian Workshop. Edited by Margaret Langdon and Leane Hinton. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 149–69. [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman, Jason A., Ripan S. Malhi, John R. Johnson, Frederika A. Kaestle, Joseph Lorenz, and David G. Smith. 2004. Mitochondrial DNA and prehistoric settlements: Native migrations on the western edge of North America. Human Biology 76: 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathauer, George H. 1951a. Religion in Mohave social structure. Ohio Journal of Science 51: 273–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fathauer, George H. 1951b. The Mohave “Ghost Doctor”. American Anthropologist 53: 605–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero-Longo, Sergio E., and Heather A. Viles. 2020. A review of the nature, role and control of lithobionts on stone cultural heritage: Weighing-up and managing biodeterioration and bioprotection. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 36: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero-Longo, Sergio Enrico, Claudia Gazzano, Mariangela Girlanda, Dl Castelli, Mauro Tretiach, Claudio Baiocchi, and Rosanna Piervittori. 2011. Physical and chemical deterioration of silicate and carbonate rocks by meristematic microcolonial fungi and endolithic lichens (Chaetothryiomycetidae). Geomicrobiology Journal 28: 732–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Margaret. 2018. Sacred water and water-dwelling serpents: What can Yuman oral tradition tell us about Yuman prehistory? Journal of the Southwest 60: 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, Martin, Tanzhuo Liu, Wallace S. Broecker, and Willard Moore. 1999. A clue regarding the origin of rock varnish. Geophysical Research Letters 26: 103–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Catherine S. 1983. Some lexical clues to Uto-Aztecan prehistory. International Journal of American Linguistics 49: 224–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, John J., and Charles E. Lyman. 2006. Tutorial review: X-ray mapping in electron-beam instruments. Microscopy and Microanalysis 12: 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golla, Victor. 2007. Linguistic Prehistory. In California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Edited by Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar. Lanham: AltaMira Press, pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Russell D., and Quentin D. Atkinson. 2003. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426: 435–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhill, Simon J., Hannah J. Haynie, Robert M. Ross, Angela M. Chira, Johann-Mattis List, Lyle Campbell, Carlos A. Botero, and Russell D. Gray. 2023. A recent northern origin for the Uto-Aztecan family. Language 99: 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnin, Maria, Guillaume Charloux, and Abdullah M. AlSharekh. 2025. The Rock Art of Saudi Arabia Life-Sized Reliefs of Camels and Equids: The Camel Site in Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/middle_east/saudi_arabia_camel_site/life_sized_reliefs_camels_equids_camel_site_saudi_arabia/index.php (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Haenszel, Arda M. 1978. The Topock Maze: Commercial or Aboriginal? San Bernardino County Museum Association Quarterly No. 26(1). San Bernardino: San Bernardino County. [Google Scholar]

- Haff, Peter K. 2014. Biolevitation of pebbles on desert surfaces. Granular Matter 16: 275–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, Peter K., and B. T. Werner. 1996. Dynamical processes on desert pavements and the healing of surficial disturbances. Quaternary Research 45: 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, John P. 1910. Review of The Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians by T.T. Waterman. American Anthropologist 12: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, John P. n.d. Papers: Southern California and Great Basin—Mojave. National Anthropological Archives. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Harris, Jack S. 1940. The White Knife Shoshoni of Nevada. In Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes. Edited by Ralph Linton. New York: D. Appleton-Century, pp. 39–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jane H. 2001. Proto-Uto-Aztecan: A community of cultivators in central Mexico? American Anthropologist 103: 913–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, Leanne. 1991. Takic and Yuman: A Study in Phonological Convergence. International Journal of American Linguistics 57: 133–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoar, Kenneth, Piotr Nowinski, Vernon Hodge, and James Cizdzie. 2011. Rock varnish: A passive forensic tool for monitoring recent air pollution and source identification. Nuclear Technology 175: 351–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, Vernon F., Dennis E. Farmer, Tammy Diaz, and Richard L. Orndorff. 2005. Prompt detection of alpha particles from Po-210: Another clue to the origin of rock varnish? Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 78: 331–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Boma. 1985. Earth Figures of the Lower Colorado and Gila River Deserts: A Functional Analysis. Phoenix: Arizona Archaeologist No. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Jack A. 2018. Case Studies in Geoarchaeometry. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, Joseph G. 1980. Western Indians: Comparative Environments, Languages, and Cultures of 172 Western American Indian Tribes. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, Joseph G. 1986. Ghost Dance, Bear Dance, and Sun Dance. In Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute, vol. 11, pp. 660–72. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2003. Self-interpretation, agency, and the objects of anthropology: Reflections on a genealogy. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45: 222–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Brian M., Angélica González-Oliver, Ripan S. Malhi, Cara Monroe, Kari Britt Schroeder, John McDonough, Gillian Rhett, Aandrew Resendéz, Rosenda I. Peñaloza-Espinosa, Leonor Buentello-Malo, and et al. 2010. Evaluating the farming/language dispersal hypothesis with genetic variation exhibited by populations in the Southwest and Mesoamerica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 107: 6759–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowta, Mark. 1984. The ‘layer cake’ model of Baja California prehistory revised: An hypothesis. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 20: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1902. Preliminary sketch of the Mohave Indians. American Anthropologist 4: 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1906. Two myths of the mission Indians of California. The Journal of American Folklore 19: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington: Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 78. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred L. 1948. Seven Mohave Myths. Anthropological Papers. Berkeley: University of California Berkeley, vol. 11, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, Carobeth. 1976. The Chemehuevis. Banning: Malki Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, Sydney. 1958. Linguistic Prehistory in the Great Basin. International Journal of American Linguistics 24: 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Howard W. 1961. A Reconstructed Proto-Culture Derived from Some Yuman Vocabularies. Anthropological Linguistics 3: 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Laylander, Donald. 2001. The question of Baja California’s prehistoric isolation: Evidence from traditional narratives. Memorias Balances y Perspectivas de la Antropología e Historia de Baja California 2: 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Laylander, Donald. 2010. Linguistic prehistory and the archaic-late transition in the Colorado Desert. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 30: 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Laylander, Donald. 2015. Three hypotheses to explain Pai origins. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 50: 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Tanzhuo. 2003. Blind testing of rock varnish microstratigraphy as a chronometric indicator: Results on late Quaternary lava flows in the Mojave Desert, California. Geomorphology 53: 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, and Wallace S. Broecker. 2007. Holocene rock varnish microstratigraphy and its chronometric application in drylands of western USA. Geomorphology 84: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, and Wallace S. Broecker. 2008a. Rock varnish evidence for latest Pleistocene millennial-scale wet events in the drylands of western United States. Geology 36: 403–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, and Wallace S. Broecker. 2008b. Rock varnish microlamination dating of late Quaternary geomorphic features in the drylands of the western USA. Geomorphology 93: 501–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, and Wallace S. Broecker. 2013. Millennial-scale varnish microlamination dating of late Pleistocene geomorphic features in the drylands of western USA. Geomorphology 187: 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, Christopher J. Lepre, and Sidney R. Hemming. 2021. Rock varnish record of the African Humid Period in the Lake Turkana basin of East Africa. The Holocene 31: 1239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, Wallace S. Broecker, John W. Bell, and Charles W. Mandeville. 2000. Terminal Pleistocene wet event recorded in rock varnish from the Las Vegas Valley, southern Nevada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 161: 423–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Tanzhuo, Wallace S. Broecker, Sidney R. Hemming, Helena Roth, Zachary C. Dunseth, Guy D. Stiebel, and Mordechai Stein. 2025. Holocene rock varnish microstratigraphy in the Dead Sea basin and Negev Desert: Chronometric application and climatic implication. Quaternary Science Reviews 352: 109146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loendorf, Lawrence L. 1991. Cation-ratio varnish dating and petroglyph chronology in southeastern Colorado. Antiquity 65: 246–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, Farrel, Manneta K. Lytle, and Keith Stever. 2011. Dating Black Canyon Petroglyphs by XRF Chemical Analysis, Appendix A. In Ethnographic and Archaeological Inventory and Evaluation of Black Canyon, Lincoln County, Nevada. Volume 1: Report and Appendices. Edited by A Gilreath, G. Bengston and B. Patterson. Washington, DC: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Report to US Fish and Wildlife Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, Farrel, Manetta Lytle, Alexander K. Rogers, Alan P. Garfinkel, Caroline Maddock, William Wight, and Clint Cole. 2008. An Experimental Technique for Measuring Age of Petroglyph Production: Results on Coso Petroglyphs. Paper presented at the 31st Great Basin Anthropological Conference, Portland, OR, USA, October 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Macholdt, Dorothea S., Klaus Peter Jochum, Abdullah Al-Amri, and Meinrat O. Andreae. 2019. Rock varnish on petroglyphs from the Hima region, southwestern Saudi Arabia: Chemical composition, growth rates, and tentative ages. The Holocene 29: 1377–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, Richard A. 2003. Editorial note. Geomorphology 53: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, William C. 1961. The cultural distinction of aboriginal Baja California. In Homenaje a Pablo Martínez del Río en el Vigésimo Quinto Aniversario del la Primera Edición de Los Orígenes Americanos. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, pp. 411–22. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, William C. 1966. Archaeology and ethnohistory of Lower California. In Archaeological Frontiers and External Connections. Handbook of Middle American Indians. Austin: University of Texas Press, vol. 4, pp. 38–58. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, Joseph R., and Eric V. McDonald. 2006. Holocene environmental change and vegetation contraction in the Sonoran Desert. Quaternary Research 65: 204–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloy, Ellen. 2003. The Anthropology of Turquoise: Reflections on Desert, Sea, Stone and Sky. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, William L. 2012. The historical linguistics of Uto-Aztecan agriculture. Anthropological Linguistics 54: 203–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, William L., Robert J. Hard, Jonathan B. Mabry, Gayle J. Fritz, Karen R. Adams, John R. Roney, and Art C. MacWilliams. 2009. The diffusion of maize to the southwestern United States and its impact. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106: 21019–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixco, Mauricio J. 2006. The indigenous languages. In The prehistory of Baja California: Advances in the Archaeology of the Forgotten Peninsula. Edited by Don Laylander. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, Cara, Brian M. Kemp, and David Glenn Smith. 2013. Exploring prehistory in the North American Southwest with mitochondrial DNA diversity exhibited by Yumans and Athapaskans. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 150: 618–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, Pamela, Nellie Brown, and Judith G. Crawford. 1992. A Mojave Dictionary. UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10. Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Musser-Lopez, Ruth A. 2011. “Mystic Maze” or “Mystic Maize”: The Amazing Archaeological Evidence. SCA Proceedings 25: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Musser-Lopez, Ruth A. 2013. Rock and Gravel Row Mounds/Aggregate Harvesting Near Historic Railroads in the Desert and Basin Regions of California and Nevada. Nevada Archaeologist 26: 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nowinski, Piotr, Vernon F. Hodge, Shawn Gerstenberger, and James V. Cizdzie. 2013. Analysis of mercury in rock varnish samples in areas impacted by coal-fired power plants. Environmental Pollution 179: 132–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntokos, Demitrios. 2021. Age estimation of tectonically exposed surfaces using cation-ratio dating of rock varnish. Catena 200: 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opler, Marvin K. 1940. The southern Ute of Colorado. In Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes. Edited by Ralph Linton. New York: D. Appleton-Century, pp. 119–203. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Randall Stewart, and John B. Adams. 1978. Desert varnish: Evidence for cyclic deposition of manganese. Nature 276: 489–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péwé, Troy L. 1978. Guidebook to the Geology of Central Arizona. Arizona Bureau of Geology and Mineral Technology Special Paper 2. Tucson: Arizona Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Carlos A., Max Peisach, Leon Jacobson, and C. Garth Sampson. 1990. Cation-Ratio Differences in Rock Patina on Hornfels and Chalcedony Using Thick Target PIXE. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B49: 332–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore, Nicholas E., and Farrel W. Lytle. 2003. Desert Varnish: Relative and Absolute Dating Using Portable X-Ray Fluorescence. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts 2003: B21C-0719. [Google Scholar]

- Plakht, Josef, Natalia Patyk-Kara, and Nina Gorelikova. 2000. Terrace Pediments in Makhtesh Ramon, Central Negev, Israel. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms: The Journal of the British Geomorphological Research Group 25: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Alexander K. 2010. A chronology of six rock art motifs in the Coso Range, Eastern California. American Indian Rock Art 36: 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Malcolm. n.d. Unpublished 1939 Report No. M-78 on the Mystic Maze, on File at the San Diego Museum of Man.

- Rowe, Samuel M., S. W. Robinson, and Henry H. Quimby. 1891. Red Rock Cantilever Bridge. Transactions American Society of Civil Engineers 25: 662–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 1985. Islands of History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmast, Masoomeh, Mohammad Hady Farpoor, and Isa Esfandiarpour Boroujeni. 2017. Soil and desert varnish development as indicators of landform evolution in central Iranian deserts. Catena 149: 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, Albert H. 1979. Prehistory: Hakataya. In Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 9, Southwest. Edited by Alfonso Ortiz and William C. Sturtevant. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 100–7. [Google Scholar]

- Seong, Yeong B., Ronald I. Dorn, and Byung U. Yu. 2016. Evaluating the life expectancy of a desert pavement. Earth Sciences Reviews 162: 129–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, David L. 2014. A Prehistory of Western North America: The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaul, David L. 2020. Baja California Languages: Description and Linguistic Prehistory. UC Berkeley Publications of the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3w42j7x8 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Shaul, David L., and Jane H. Hill. 1998. Tepimans, Yumans, and Other Hohokam. American Antiquity 63: 375–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, Douglas B., Amanda C. Hudson, John E. Keller, Michael Strange, Andressa Cristhy Buch, David Ferrari, Giavanna M. Fernandez, Juan Garcia-Hernandez, Bailey D. Kesl, and Sean Torres. 2022. Trace elements migrating from tailings to rock varnish laminated sediments in an old mining region from Nelson, Nevada, USA. International Journal of Sediment Research 37: 202–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskin, Edgar E. 1983. Washo Shamans and Peyotists: Religious Conflict in an American Indian Tribe. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spilde, Michael N., Leslie A. Melim, Diana E. Northup, and Penelope J. Boston. 2013. Anthropogenic lead as a tracer for rock varnish growth: Implications for rates of formation. Geology 41: 263–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, M. E. 1958. Desert pavement and vesicular layer of some soils of the desert of the Lahontan Basin, Nevada. Proceedings Soil Science Society America 22: 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, Karen L., Carolyn E. Boyd, and J. Phillip Dering. 2025. Mapping the chronology of an ancient cosmovision: 4000 years of continuity in Pecos River style mural painting and symbolism. Science Advances 11: eadx7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, Julian. 1955. Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Kenneth M. 1973. Witchcraft among the Mohave Indians. Ethnology 12: 315–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, Linea. 1996. Mirrors of Heaven: Cross-Cultural Transference of the Sacred Geography of the Black Hills. World Archaeology 28: 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Mark Q. 2009. People and Language: Defining the Takic Expansion into Southern California. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 41: 31–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ugalde, Paula C., Jay Quade, Calogero M. Santoro, and Vance T. Holliday. 2020. Processes of Paleoindian site and desert pavement formation in the Atacama Desert, Chile. Quaternary Research 98: 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Werlhof, Jay. 1995. Geoglyphs in Time and Space. Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology 8: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Werlhof, Jay. 2004. That They May Know and Remember, Volume 2: Spirits of the Earth. Ocotillo: Imperial Valley College Desert Museum Society. [Google Scholar]

- von Werlhof, Jay, Harry Casey, Ronald I. Dorn, and Glenn A. Jones. 1995. AMS 14C age constraints on geoglyphs in the lower Colorado River region, Arizona and California. Geoarchaeology 10: 257–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, William J. 1947. The Dream in Mohave Life. The Journal of American Folklore 60: 252–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Thomas T. 1909. Analysis of the Mission Indian creation story. American Anthropologist 11: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 1992. Prehistory and Post-Positivist Science: A Prolegomenon to Cognitive Archaeology. Archaeological Method and Theory 4: 57–100. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2005. Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2007. Indigenous Knowledge and 21st Century Archaeological Practice: An Introduction. SAA Archaeological Record 7: 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2009. Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origin of Creativity and Belief. New York: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2011. Rock Art, Religion and Ritual. In Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Edited by Tim Insoll. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 307–26. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2013. Rock art dating and the peopling of the Americas. Journal of Archaeology 2013: 713159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2014. Jay von Werlhof’s Trail of Dreams. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 50: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2019. Early Northern Plains Rock Art in Context. In Dinwoody Dissected: Looking at the Interrelationships Between Central Wyoming Petroglyphs. Edited by Danny N. Walker. Laramie: Wyoming Archaeological Society, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2020. Cognitive Archaeology Revisited: Agency, Structure and the Interpreted Past. In Cognitive Archaeology: Mind, Ethnography and the Past in South Africa and Beyond. Edited by David S. Whitley, Johannes H. N. Loubser and Gavin Whitelaw. London: Routledge, pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2021. Rock Art, Shamanism and the Ontological Turn. In Ontologies of Rock Art: Images, Relational Approaches and Indigenous Knowledge. Edited by Oscar Moro Abadia and Masrtin Porr. London: Routledge, pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2023. Ethnography, Shamanism, and Far Western North American Rock Art. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolumbino 28: 275–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2024. Thinking, for Example in and About the Past: Approaches to Ideational Cognitive Archaeology. In Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Archaeology. Edited by Thomas Wynn, Karenleigh A. Overmann and Frederick L. Coolidge. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 339–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S., and Ronald I. Dorn. 1993. New Perspectives on the Clovis vs. Pre-Clovis Controversy. American Antiquity 58: 626–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S., Calogero Santoro, and Daniela Valenzuela. 2017. Climate Change, Rock Coatings and the Archaeological Record. Elements 13: 183–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S., Ronald I. Dorn, Joseph M. Simon, Robert Rechtman, and Tamara K. Whitley. 1999. Sally’s Rockshelter and the Archaeology of the Vision Quest. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9: 221–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Aaron M., Lorey Cachora, and Nathalie O. Brusgaard. 2024. An Ecology of the Yuman-Patayan Dreamland. In Sacred Southwestern Landscapes: Archaeologies of Religious Ecology. Edited by Aaron M. Wright. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yu-Ming, Tanzhuo Liu, and Shu-wei Li. 1990. Establishment of a Cation-Leaching Curve of Rock Varnish and its Application to the Boundary Region of Gansu and Xinjiang, Western China. Seismology and Geology 12: 251–61. [Google Scholar]

| Intaglio, Site | VML Age cal yr BP | CR Age cal yr BP | Lead Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zigzag/Snake, Quien Sabe | 650 | 500 ± 300 | Pre-20th century |

| Stick Figure, Winterhaven | n/a * | 750 ± 300 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph, Pilot Knob | n/a | 850 ± 350 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph 1, Blythe Giant | n/a | 1000 ± 350 | n/a |

| Quadruped, Blythe Giant | n/a | 1100 ± 400 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph 2, Blythe Giant | n/a | 1100 ± 400 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph, Ripley Complex | between 1100–1400 | 1200 ± 450 | Pre-20th century |

| Cross, Ripley Complex | between 1100–1400 | 1250 ± 450 | Pre-20th century |

| Largest Anthropomorph, Quartszite | n/a | 1350 ± 350 | n/a |

| Amorphous Form, Quartszite Airport | n/a | 1400 ± 400 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph, Quien Sabe | 1400 | 1500 ± 450 | n/a |

| Lizard Figure, Ripley | n/a | 1600 ± 500 | n/a |

| ‘Snake’ Head, Singer Complex | n/a | 1900 ± 550 | n/a |

| ‘Snake’, Museum complex near Ocotillo | n/a | 2900 ± 750 | n/a |

| Schneider Dance Circle, Yuha Mesa | n/a | 3200 ± 750 | n/a |

| Anthropomorph, Quien Sabe | 5900 | 6100 ± 1200 | n/a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Whitley, D.S.; Dorn, R.I. Rock Varnish Dating, Surface Features and Archaeological Controversies in the North American Desert West. Arts 2026, 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010006

Whitley DS, Dorn RI. Rock Varnish Dating, Surface Features and Archaeological Controversies in the North American Desert West. Arts. 2026; 15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhitley, David S., and Ronald I. Dorn. 2026. "Rock Varnish Dating, Surface Features and Archaeological Controversies in the North American Desert West" Arts 15, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010006

APA StyleWhitley, D. S., & Dorn, R. I. (2026). Rock Varnish Dating, Surface Features and Archaeological Controversies in the North American Desert West. Arts, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010006