Rock Images at La Casa de las Golondrinas and the Kaqchikel Maya Context in Guatemala

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Can ethnographic and ethnohistoric information help us understand the meaning and importance of the site itself?

- Does the ethnographic and ethnohistoric information add to our understanding of the rock art images at the site?

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

- Ethnohistoric documents: The Annals of the Cakchiquels and the Popul Vuh (the latter being a documentation of the Kiche/Kaqchikel belief system and history that was created by Mayan religious leaders shortly after the conquest and kept hidden for many years).

- Documented ethnographic research on current practices of traditional Maya religion among the Kaqchikel, especially the work of Judith Maxwell of Tulane University.

- The archaeologically and ethnohistorically documented epoch of extensive pan-Mesoamerican adoption of a common set of core beliefs and shared symbol sets derived from Central Mexican models and Aztec iconography that were taken up during the Late Postclassic period (Boone and Smith 2003).

- Key informants, including celebrants of the present-day Maya religion and individuals who embrace traditional Kaqchikel knowledge and beliefs while living in modern Guatemala.

- Limited archaeological excavation and dating at the Golondrinas site itself.

4. Geography and History of Golondrinas

Kaqchikel Late Postclassic History

5. The Antigua Valley Environmental Setting

6. Ritual Landscapes and Kaqchikel Ethnography

6.1. The Quincunx and the Guardians of the Community

6.2. Historical Events Related to Sacred and Ritual Sites

“While subsequent rituals performed at these sites recall and celebrate these events, they also consecrate the space. The Xajil Chronicles (Maxwell and Hill 2006) gives four names associated with this original sacrifice: Kaqb’atz’ulu’ (the mountain), Tza’m Tzaqb’äl Tolk’om (the precipice from which his quartered and arrow riddled body was cast) and Pan Pati’, Pa Yan Ch’okol (sites next to Lake Atitlan where the waters roiled stirred by the pieces of Tolk’om’s body). Kaqb’atz’ulu remains an active ritual site. Both Pan Pati’ and Pa Yan Ch’oköl continue to serve as spaces for spiritual contact, sacrifice and ritual.”

6.3. Caves/Openings/Cracks—Portals

“At the Chwi’ K’ajol site men working the cornfields have seen a stranger, sometimes a man, sometimes a youth, climb up along the ravine only to disappear in the rock face. At an altar above Xe Na Koj spirit soldiers emerge at midnight, march in formation, and then re-enter the solid rock faces.”

6.4. Rock Shelters as Shrines and for Dances

6.5. Mountain Peaks

7. Present Day Spirituality and Ritual

“All the sacred sites share features which allow ajq’ijab’ to recognize them, even if the site is inactive. Some features are apparent without spiritual training. Physical prominences generally have one or more associated altars. Large exposed vertical rock faces, rock overhangs, caves and tunnels are propitious spots for altars. Of course, not every rock or cliff is consecrated space. Ajq’ijab’ can feel the energy of the physical environment. Once a spot has been identified as a portal for appropriate energy, then rituals may be performed there. Each rite, in successfully establishing communication with the ancestors and the spiritual realm strengthens the connection provided by that portal. Each full ritual begins with a re-creation of the cosmos, establishing the four corners of terrestrial plane, erecting the sky, crafting woman, man, the human generations and the spiritual plane. In counting the days, not in the yearly round, but in the ritual cycle (13 successive iterations of each day), time too is set in motion, yielding an Einsteinian universe, a space-time continuum”.

“The ritual invocation calls upon the celebrants’ ancestors, both close genetic kin and legendary forebears, as well as on the spiritual agents of creation. These spirits, both human and supernatural, are guests at the banquet laid out as an offering. Part of the offering is presented through the ritual fire; part is laid or poured along the altar, proportions dictated by the knowledge granted the celebrant ajq’ij. The consumption rate of the fire indicates both the hunger of the spirits and their acceptance or rejection of the offerings and the petition. At first neglected ritual sites may burn very rapidly and part of the spiritual communication may include instructions for subsequent offerings to reactivate the site and supply further spiritual sustenance.”

“Each site has at least one day of the 260-day ritual calendar, the cholq’ij (cf. cognate Yucatec Maya tzolk’in), which is associated with that site. Each altar, then, can be named by its eponymous day(s), specified by both the day-named and its numeral coefficient, such as Waqxqi’I’x “Eight Jaguar”. Just as each day of the calendar round has certain virtues, making it propitious for certain undertakings and their associated petitions, so each ritual site with its associated day lends itself to these same undertakings and petitions.”

“Ajq’ijab’ select specific days for ritual according to the needs of their clients. They likewise select the appropriate altars. If, for some reason, the ritual can not be done on the most propitious day, a series of accommodations can be made, establishing spiritual connections through the host day and invoking complexes of associate day-bearers. Likewise, the altar chosen need not always be that associated with the day of the ritual celebration. One of the tasks of the ajq’ij is to negotiate the spiritual interrelations of the calendar day, the day-spirit of the altar, the day-spirit of the client, and that of the celebrant himself.”

8. Golondrinas as a Sacred Site

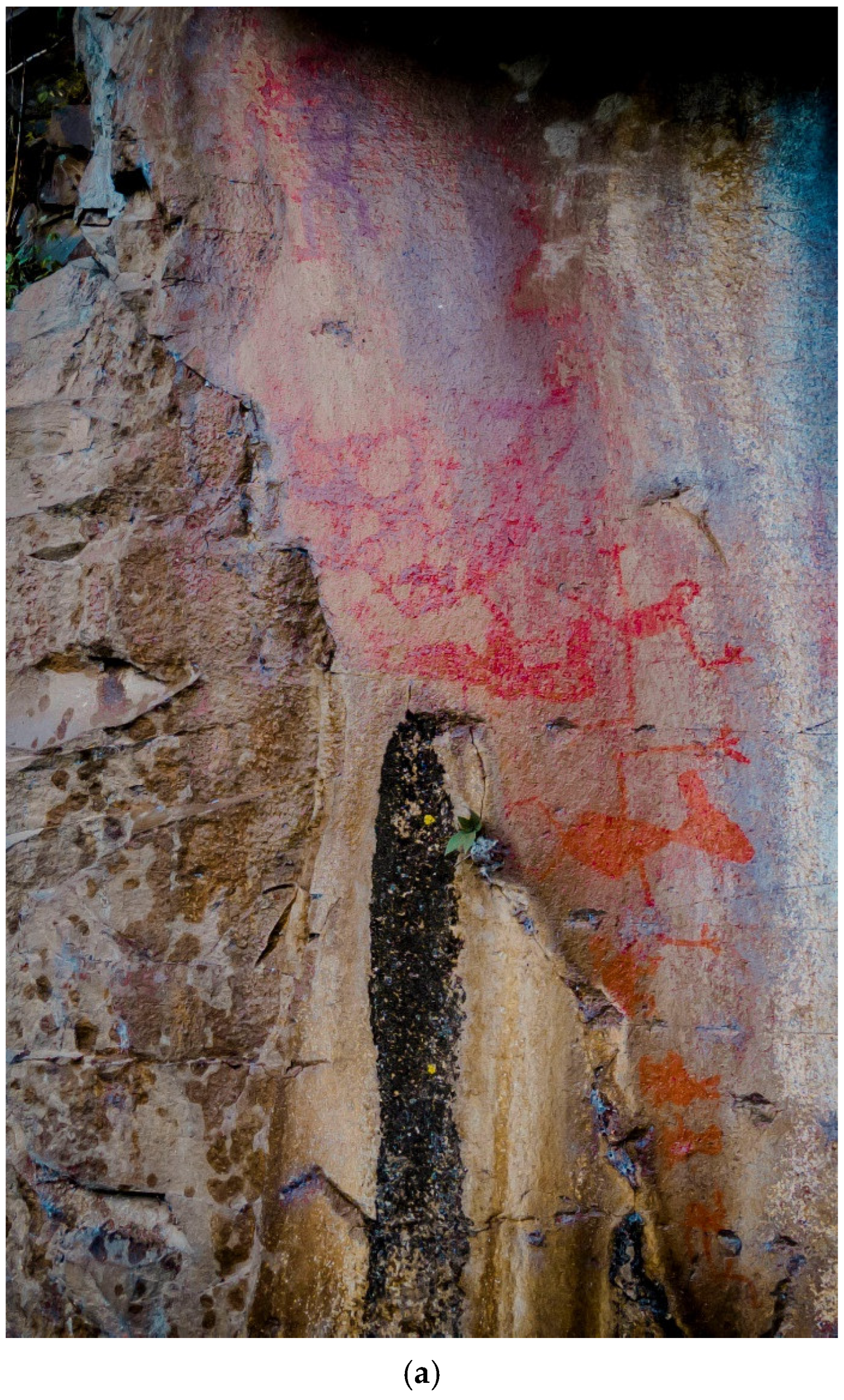

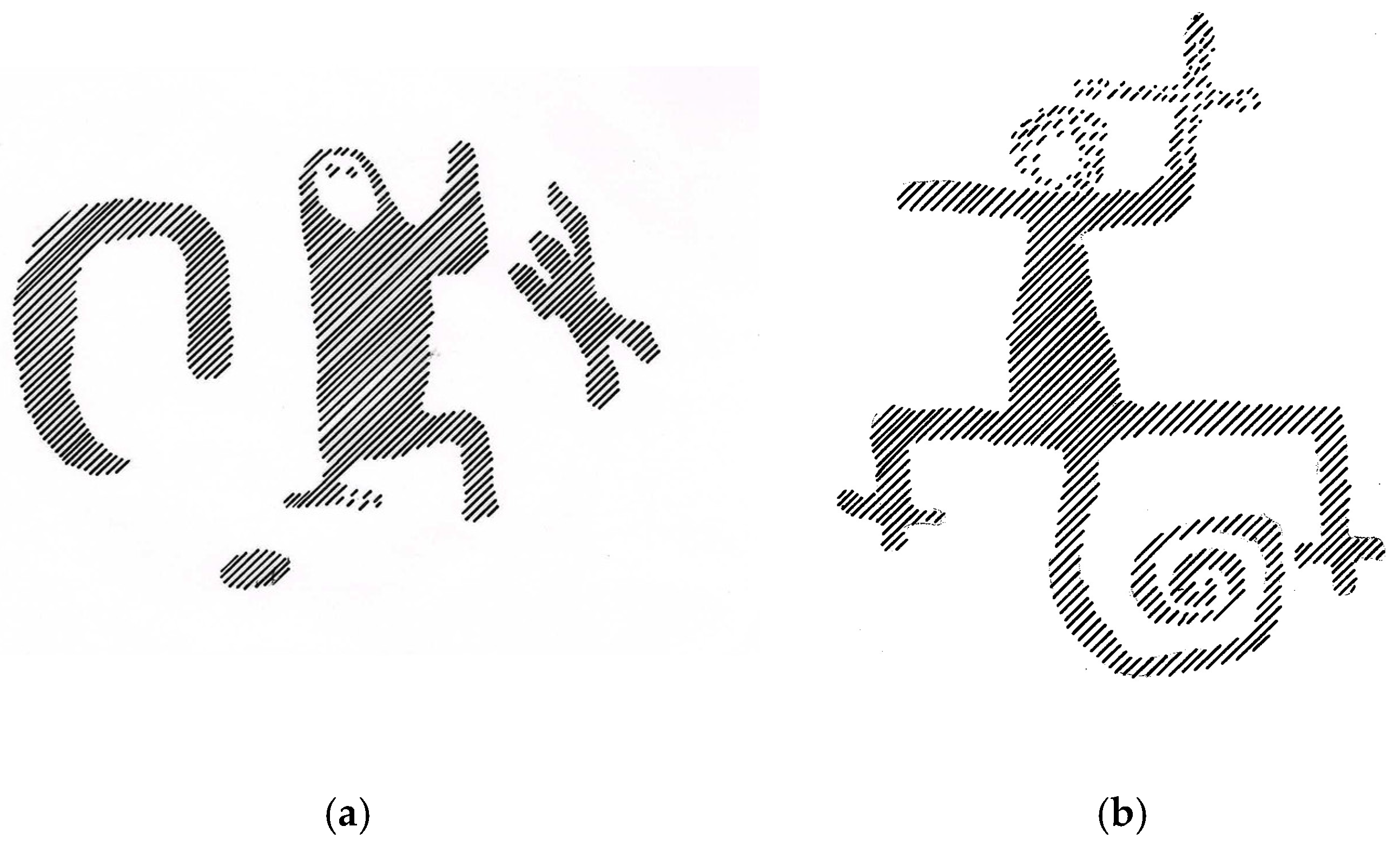

9. Sacred Content of Selected Rock Paintings

9.1. Interpretations of Historical Events and Mythological Deities

9.1.1. The Fire-Serpent

9.1.2. Plumed Serpent

9.1.3. Serpent–Person Interaction

9.1.4. Portals

10. A Solar Calendar at Golondrinas

10.1. A Sun Calendar in the Highlands

“Haremos un análisis de las pinturas rupestres de la Casa de las Golondrinas, en donde se encuentran plasmadas distintas escenas relacionadas al movimiento del sol desde la visión del pueblo maya Kaqchikel.”

“Los solsticios y equinocios, representan un cambio y comienzo, para los pueblos originarios, por lo que son recibidos con celebraciones por medio de ofrendas y ceremonias”.

“Estos acontecimientos también están vinculados a la conexión con nuestros ancestros, nuestras cosechas y la forma en que nos conectamos con la tierra. Este conocimiento que permanece en el imaginario colectivo Maya Kaqchikel, se da por medio de la tradición oral y la observación, este es un legado ancestral que se transmite y practica de generación en generación.”

“Una de las prácticas y conocimientos, relacionadas a la observación del sol, se da cuando el sol sale del lado este, que es para nosotros en donde nace el sol, por lo que nuestros abuelos con mucha reverencia y respeto lo saludan con la frase en idioma Kaqchikel “Loq’olej q’il, “El Gran Senor Sol”’ y que en el calendario actual se da el 21 de marzo. Lo que representa un día y una noche larga.”

“We will analyze the rock art of La Casa de las Golondrinas, from the Kaqchikel perspective where different scenes related to the movement of the sun are depicted.”

“The solstices and equinoxes represent a change and a beginning for indigenous people and are welcomed with celebrations of offerings and ceremonies.”

“These events are linked to the connection with our ancestors, our harvests and is the form in which we connect with the earth. This knowledge which remains in the Kaqchikel Maya collective imagination, is passed down through oral tradition and observation, it is an ancient legacy that is transmitted and practiced from generation to generation.”

“One of the practices and knowledge related to the observation of the sun is that when the sun rises in the east, which for us is where the sun is born, because our grandfathers with much respect and reverence greet it with the phrase in the Kaqchikel language “Loq’olej q’ij”, the great sun”, and that in the actual calendar it is the 21st of March, that represents an equal day and night.”(Puc Rucal and Robinson 2024) (English translation by E. Robinson 19 May 2025)

“De acuerdo a las enseñanzas de nuestros ancestors los mayas, de nuestros tatarabuelos, bisabuelos y abuelos es que a finales del mes de marzo y a mediados del mes de abril, cuando pasan las aves llamados Azacuanes en el cielo formando una cruz, esto para los mayas kaqchikeles es de mucho respecto. Por esa razón se nos ha inculcado tener respeto a estas aves, porque se consideran sagradas. Estas aves anuncian la llegada del invierno. Se enseña desde la niñez, que ellos vienen del lado este donde nace nuestro astro rey, en idioma maya kaqchikel Ri Rokoley Kij—nuestro gran sol—y podemos decir es cuando nace el invierno, y es un signo o código que nos indica la llegada o inicio del invierno y nace la lluvia.”

“Y cuando las aves llamadas Azacunes vienen del lado oeste, donde muere nuestro rey, en idioma maya kaqchikel Ri Rokóley Kij—nuestro gran sol—, es un signo o código que nos indica la muerte del invierno, es el anuncio que la lluvia está terminando y anuncia la llegada del verano.”

“According to the teaching of our ancestors the Mayas, from our great-great grandfathers, great grandfathers, and grandfathers is that at the end of the month of March and until the middle of the month of April, when the birds called the Azacuanes pass in the sky forming a cross, this for the Mayas Kaqchikeles is greatly respected. For this reason we are taught to have respect for these birds, because they are considered sacred. These birds announce the arrival of the rainy season. By training since a child, when they come from the east side where our sun lord is born, in the Maya Kaqchikel idiom Ri Rokoley Kij—our great sun—we can say that is when the winter is born, and it is a sign or message that indicates to us the arrival or beginning of the winter and the rain is born.”

“And when the birds called the Azacunes come the from the west side, where our king dies in the Kaqchikel idioma Ri Rokoley Kij—our great sun—it is a sign or a message that shows us the death of the rainy season, it is the announcement that the rain is stopping and announces the arrival of summer.”(Translation by Robinson 27 May 2025)

10.2. Ceremonies of Hunting/Sacrifice and Seasonal Animals

11. Paintings with Connections to the Popul Vuh

11.1. The Hero Twins

11.2. Junajpu, the Principal God Ajpu’

11.3. Creation According to the Popul Vuh

“There is not yet one person, one animal, bird, fish, crab, tree, rock, hollow, canyon, meadow, or forest. All alone the sky exists. The face of the earth has not yet appeared. Alone lies the expanse of the sea, along with the womb of all the sky. There is not yet anything gathered together. All is at rest. Nothing stirs. All is languid, at rest in the sky. There is not yet anything standing erect. Only the expanse of the water, only the tranquil sea lies alone. There is not yet anything that might exist. All lies placid and silent in the darkness, in the night.”

“All alone are the Framer and the Shaper, Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent, They Who Have Borne Children and They Who Have Begotten Sons. Luminous they are in the water, wrapped in quetzal feathers and cotinga feathers. Thus they are called Quetzal Serpent. In their essence, they are great sages, great possessors of knowledge. Thus surely there is the sky. There is also Heart of Sky, which is said to be the name of the God”.

“Then they called forth the mountains from the water. Straightaway the great mountains came to be. It was merely their spirit essence, their miraculous power, that brought about the conception of the mountains and the valleys. Straightaway were created cypress groves and pine forests to cover the face of the earth.”.

“Then they conceived the animals of the mountains, the guardians of the forest, and all that populate the mountains—the deer and the birds, the puma and the jaguar, the serpent and the rattlesnake, the pit viper and the guardian of the bushes.”.

“You deer, will sleep along the courses of rivers and the canyons, Here you will be in the meadows and in the orchards. In the forests you shall multiply. You will walk on all fours, and thus you will be able to stand, they were told…. You, birds, you will make your homes and your houses in the tops of trees in the tops of bushes. There you will multiply and increase in numbers in the branches of the trees and the bushes…. Thus all was completed for the deer and the birds.”.

12. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Abigail, and James Brady. 1994. Etnografía Q’eqchi’ de los Ritos En Cuevas: Implicaciones para la Interpretación Arquológica. In VII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueologicas en Guatemala, 1993. Edited by Juan Pedro Laporte and Héctor L. Escobedo. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologia y Etnologia, pp. 205–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Abigail, and James Brady. 2005. Ethnographic Notes on Maya Q’eqchi Cave Rites: Implications for Archaeological Interpretation. In In the Maw of the Earth Monster. Edited by James Brady and Keith Brufer. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 301–27. [Google Scholar]

- Anschuetz, Kurt E., Richard H. Wilshusen, and Cherie L. Scheick. 2001. An Archaeology of Landscapes: Perspectives and Directions. Journal of Archaeological Research 9: 157–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, Elizabeth H., and Michael E. Smith. 2003. Postclassic International Styles and Symbol Sets. In The Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Edited by Michael E. Smith and Francis F. Berdan. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, pp. 186–93. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Carolyn. 2016. The White Shaman Mural. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, James, and Wendy Ashmore. 1999. Mountains, Caves and Water: Ideational Landscapes of the Ancient Maya. In Archaeologies of Landscape Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Wendy Ashmore, Ann Knapp and Arthur Bernard. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 124–45. [Google Scholar]

- Braswell, Geoffrey, and Eugenia Robinson. 2014. The Other Preclassic Maya: Interaction, Growth and Depopulation in the Eastern Kaqchikel Highlands. In The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors. Edited by Geoffrey E. Braswell. New York: Routledge, pp. 115–49. [Google Scholar]

- Broda, Johanna, and Alejandra Gámez, eds. 2009. Cosmovisión Mesoamericana y Ritualidad Agrícola. Estudios Interdisciplinarios y Regionales (Mesoamerican Worldview and Agricultural Ritualism. Interdisciplinary and Regional Studies). Mexico City: BUAP. [Google Scholar]

- Broda, Johanna, Stanislaw Iwaniszewski, and Arturo Montero, eds. 2001. La Montaña en el Paisaje Ritual (Mountain in the Ritual Landscape). Mexico City: CONACULTA, INAH. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Linda. 2006. Planting the Bones: An Ethnoarchaeological Exploration of Hunting Shrines and Deposits Around Lake Atitlán, Guatemala. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/05012 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Campbell, Lyle. 1999. Historical Linguistics. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Sorayya, and Eugenia Robinson. 2004. Fauna and Ritual at La Casa de las Golondrinas. Paper presented at a General Mesoamerican Session, Montreal, QC, Canada, April; Montreal: Society for American Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Caso, Alfonso. 1971. Calendrical Systems of Central Mexico. In The Handbook of Middle American Indians 10. Edited by Robert Wauchope. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 333–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla, Oswaldo Mazariegos. 2017. Art and Myth of the Ancient Maya. New Haven: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, Allen J. 2007. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, John E., and Mary E. Pye, eds. 2000. The Pacific Coast and the Olmec Question. In Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 217–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cojti, Ren, and Iyaxel Ixkan. 2020. The Emergence of the Ancient Kaqchikel Polity: A Case of Ethnogenesis in the Guatemalan Highlands. Ph.D. dissertation, Vanderbilt Institutional Repository, Nashville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonson, Munro S. 1971. The Book of Counsel: The Popol Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publication 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Eschova, Galina, Patricia Rivera Castillo, and Vladimir Krivochurov. 2023. La Casa de las Golondrinas en Guatemala: El Mapa Astronómico Exacto Más Antigua del Mundo. Wiltshire: CEMYK. [Google Scholar]

- Folan, William J., David D. Bolles, and Jerald D. Ek. 2016. On the Trail of Quetzlcoatl/Kukulcan. Ancient Mesoamerica, No 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Freidel, Dorothy E., John G. Jones, and Eugenia Robinson. 2011. Volcanic Eruptions, Earthquakes, and Drought: Environmental Challenges for the Ancient Maya People of the Antigua Valley, Guatemala. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 73: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Edgar Vinicio. 1992. Reconocimiento Arqueologico de las Tierras Altas Centrales de Chimaltenango. Thesis de Licenciado en Arqueologia, Escuela de Historia, San Carlos University, Guatemala City, Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- Garnica, Marlen. 2025. Breve Recorrido por El Arte Rupuestre de Guatemala, un Enfoque Particular Hacia la Region este del Pais, in Pronteras Repuestres en Mexico. Edited by Carlos Viramontes Anzures and Aline Lara Galica. Rome: RomaTre Press, Seville: Enredars-UPO, pp. 266–91. Available online: https://rio.upo.es/rest/api/core/bitstreams/f4cb48c6-6abb-4730-aca0-fa7917c956ef/content (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Girard, Rafael. 1962. Los Mayas Eternos. Mexico City: Libro Mes Editories. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, David. 1999. Public Monuments and Sacred Mountains: Observations on Three Formative Period Sacred Landscapes. In Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica. Edited by David Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Thomas. 2008. The Ancient Spirituality of the Modern Maya. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, Gerald H., Detlef Gunther, Larry C. Petterson, Daniel M. Sigman, Konrad A. Hughen, and Beat Aeschlimann. 2003. Climate and Collapse of Maya Civilization. Science 299: 1731–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, Soc, and Alba Patricia. 2022. Para Santa Elena de las Cruz, la Danza de la Serpiente (Santa Cruz del Quiché, Guatemala. In Los Animales del Agua en la Cosmovisión Indigena/Una Perspectiva Historica y Anthropologica. Ciudad de Mexico: CIESAS. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Robert. 1996. Eastern Chajoma (Cakchiquel) Political Geography. Ancient Mesoamerica 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hlúšek, Radoslav. 2020. Ritual Landscape and Sacred Mountains in Past and Present Mesoamericapp. Reviews in Anthropology 49: 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Terrence. 1969. Some Recent Hypotheses on Mayan Diversication. Language Behavior Research Laboratory, Working Paper 26. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Layton, Robert. 2001. Ethnographic Study and Symbolic Analysis. In Handbook of Rock Art Research. Edited by David Whitley. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 311–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and David C. Pearce. 2015. San Rock Art: Evidence and Argument. Antiquity 89: 732–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looper, Matthew. 2019. The Beast Between: Deer in Maya Art and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, Christopher. 1984. Historia Sociodemográfica de Santiago de Guatemala 1541–1773. South Woodstock and Guatemala City: CIRMA. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Judith M., and Ajpub’ Pablo Garcia Ixmatá. 2008. Power in Places: Investigating the Sacred Landscape of Iximche. Available online: https://www.famsi.org/reports/06104/index.html (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Maxwell, Judith M., and Robert M. Hill, II. 2006. Kaqchikel Chronicles: The Definitive Edition. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milbrath, Susan. 1999. Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy in Art, Folklore, and Calendars. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube. 1993. The Gods and Symbols of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, Hector, Deborah M. Pearsall, John G. Jones, Barbara Arroyo, Shawn K. Collins, and Dorothy E. Freidel. 2006. Early Maya Adaptive Patterns: Mid-Late Holocene Paleoenvironmental Evidence from Pacific Guatemala. Latin American Antiquity 17: 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palka, Joel. 2014. Maya Pilgrimage to Ritual Landscapes. Tucson: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peniche, Chávez y, Margarita Loera, and Ricardo Cabrera Aguirre, eds. 2011. Moradas de Tláloc. Arqueología, Historia y Etnografía Sobre la Montaña (Dwellings of Tlaloc. Archaeology, History, and Ethnography about the Mountain). Mexico City: ENAH, INAH, CONACULTA, DEH, DEA. [Google Scholar]

- Puc Rucal, Luis Paulino. 2017. El Maiz Criollo de las Kaqchikeles Municipio de Sumpango, Sacatepéquez. In Maiz: Patrimonio Cultural de la Nacion. Compiled by Olga Lidia Xicará Méndez. Guatemala City: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Puc Rucal, Luis Paulino, and Eugenia Robinson. 2024. Astronomia y Calendario Agricola, en las Pinturas Rupestres de la Casa de las Golondrinas, y su Reclación con los Documentos Ethnohistoricos del Popol Vuh y El Memorial de Sololá, un Legado de Conocimientos Ancestrales Mayas de las Tierras Altas de Guatemala. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Recinos, Adrián. 1950. Popul Vuh. Translated by la Delia Goetz, and Sylvanus G. Morley. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rezzio Carpio, Edgar H. 2019. Diablo Rojo: Antecedents de Investigacion, Interpretaciones y Estado Actual de una Pinture Rupestre de Estilo Olmeca en el Municipio de Amatitlán, Guatemala. Available online: http://www.revistasguatemala.usac.edu.gt/index.php/reeh/article/view/1217 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Ringle, William M., Tomás Gallareta Negrón, and George J. Bey, III. 1998. The Return of Quetzalcoatl: Evidence for the Spread of a World Religion during the Epiclassic Period. Ancient Mesoamerica 9: 183–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Eugenia. 1998. Organizacion del Estado Kaqchikel: El Centro Regional de Chitak Tzak. In Estudios Kaqchikeles: En Memorium William R. Swezey. Edited by Eugenia J. Robinson and Robert M. Hill. Antigua: CIRMA, pp. 217–28. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Eugenia. 2008. Memoried Sacredness and International Elite Identities: The Late Postclassic at La Casa de las Golondrinas, Guatemala. In Archaeologies of Art: Time, Place, and Identity. Edited by Ines Domingo Sanz, Danae Fiore and Sally K. May. California: Left Coast Press, pp. 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Eugenia. 2014. The Other Late Classic Maya: Regionalization, Defense, and Boundaries in the Central Guatemalan Highlands. In The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors. Edited by Geoffrey E. Braswell. New York: Routledge, pp. 150–74. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Eugenia, and Gene A. Ware. 2002. Multi-Spectral Imaging of La Casa de las Golondrinas Rock Paintings. Available online: http://www.famsi.org/reports/99052/index (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Robinson, Eugenia, Geoffrey Braswell, and Francisco Estrada-Belli. 2023. Least-Cost Routes and the Kaqchikel Maya Region: Intercommunity Trade, Movement and Communication. In Routes, Interaction and Exchange in the Southern Maya Area. Edited by Eugenia Robinson and Gavin Davies. London and New York: Routeledge, pp. 200–28. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Eugenia, Marlen Garnica, Ruth Ann Armitage, and Marvin W. Rowe. 2007. Los Fechamientos del arte rupestre y la arqueologia en la Casa de las Golondrinas, San Miguel Duenas, Sacatépequez. In XX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala. Edited by Juan Pedro Laporte, Bárbara Arroyo and Héctor Mejía. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueología e Etnología, pp. 959–72. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Eugenia, Patricia Farrell, Kitty Emery, and Geoffrey Braswell. 2002. Preclassic Settlements and Geomorphology in the Highlands of Guatemala: Excavations at Urias, Valley of Antigua. In Incidents of Archaeology in Central America and Yucatan. Edited by Michael Love, Marion Hatch and Hector Escobedo. Lanham: University Press of America, pp. 251–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schele, Linda, and Julia Guernsey Kappelman. 2003. What the Heck’s Coatepec? The Formative Roots of an Enduring Mythology. In Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica. Edited by Annabeth Headrick, Kathryn Reese-Taylor and Rex Koontz. Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 279–316. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Michael. 2003. Information Networks in Postclassic Mesoamerica. In The Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Edited by Michael Smith and Francis Berdan. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 181–85. [Google Scholar]

- Soustelle, Jacques. 1970. The Four Suns: Recollections and Reflections of an Ethnologist in Mexico. New York: Grossman. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Andrea. 1999. Postclassic Mesoamerican Rock Art in Historical Context. Paper presented at the International Rock Art Conference, Ripon, WI, USA, May 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Andrea, and Sergio Ericastilla Godoy. 1998. Registro de Arte Rupestre en Las Tierras Altas de Guatemala: Resultados del Reconocimiento de 1997. In XII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueologicas en Guatemala, 1997. Edited by Juan Laporte, Hector Escobedo and Ana Monzon de Suasnavar. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologia y Ethnologia, pp. 775–883. [Google Scholar]

- Taçon, Paul S. C. 2022. The Histories of Arnhem Land Rock Art Research: A Multicultural, Multilingual, and Multidisciplinary Pursuit. In Histories of Australian Rock Art Research, 1st ed. Edited by Paul S. C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick and Jo McDonald. Canberra: ANU Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2xc67sp (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Taube, Karl. 2000. The Turquoise Hearth: Fire, Self-Sacrifice, and the Central Mexican Cult of War. In Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: From Teotihucan to the Aztecs. Edited by David Carrasco, Lindsay Jones and Scott Sessions. Boulder: University Press of Cororado. [Google Scholar]

- Taube, Karl. 2018. The Temple of Quetzalcoatl. In Studies in Ancient Mesoamerican Art and Architecture. Selected Works by Karl Andreas Taube. San Francisco: Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, pp. 204–25. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tedlock, Barbara. 1982. Time and the Highland Maya. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tedlock, Dennis. 1985. Popul Vuh. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Tedlock, Dennis, trans. 1996. Popul Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Tokovinine, Alexandre, and Vilma Fialko. 2019. El Cerro de los Colibris: El Patrón Divino y el Pasiaje Sagrado de la Ciudad de Naranjo. In XXXII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2018. Edited by Bárbara Arroyo, Luis Méndez Salinas and Gloria Ajú Álvarez. Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueologia y Ethnologia, pp. 825–38. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Richard. 1982. Richard Townsend Pyramid and Sacred Mountain. In Ethnoastronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the American Tropics. Edited by Anthony Aveni and Gary Urton. New York: Academy of Sciences, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vail, Gabrielle, and Christine Halpern. 2018. The Maya Hieroglyphic Codices Database, Version 5.0. A Website and Database. Available online: http://www.mayacodices.org/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Vail, Gabrielle, and Matthew G. Looper. 2015. World Renewal Rituals Among the Postclassic Yucatec Maya. Estudios de Cultura Maya 45: 121–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Evon Z. 1969. Zinacantan. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2021. Rock Art, Shamanism, and the Ontological Turn. In The Ontologies of Rock Art. Edited by Oscar Moro Abadía and Martin Porr. London: Routledge, pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zapil Chivir, Juan. 2007. Aproximación Lingüistica y Cultural a los 20 Nawales del Calendario Maya Practicado en Momostenango, Totonicapán. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Rafael Landivar, Guatemala City, Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

| Time Period (Antigua Valley) | Name of Phase (Antigua Valley) | Date of Phase | Phases Represented at Golondrinas by Radiocarbon Dates or Diagnostic Ceramics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic | Unnamed | 4000 B.C. | |

| Early Preclassic | Urias | 1700–1000 B.C. | x |

| Middle Preclassic | Agua | 800–350 B.C. | x |

| Late Preclassico | Sacatepequez | 350–100 B.C. | x |

| Terminal Preclassic | Xaraxong | 100 B.C.–A.D. 200 | |

| Early Classic | Terrenos | 200–600 A.D. | x |

| Late Classic | Pompeya | 600–800 A.D. | x |

| Early Postclassic | Primavera | 800–1200 A.D. | x |

| Late Postclassic | Medina | 1200–1524 A.D. | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robinson, E.J.; Rucal, L.P.P. Rock Images at La Casa de las Golondrinas and the Kaqchikel Maya Context in Guatemala. Arts 2025, 14, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060154

Robinson EJ, Rucal LPP. Rock Images at La Casa de las Golondrinas and the Kaqchikel Maya Context in Guatemala. Arts. 2025; 14(6):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060154

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobinson, Eugenia Jane, and Luis Paulino Puc Rucal. 2025. "Rock Images at La Casa de las Golondrinas and the Kaqchikel Maya Context in Guatemala" Arts 14, no. 6: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060154

APA StyleRobinson, E. J., & Rucal, L. P. P. (2025). Rock Images at La Casa de las Golondrinas and the Kaqchikel Maya Context in Guatemala. Arts, 14(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060154