1. Introduction

The traditional embroidery produced by the Nahua women of Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla, constitutes a means of visual communication that is full of meaning and closely linked to the social, religious, and cultural life of the native population. Through textile iconography, primarily depicted in traditional blouses, the embroiderers represent elements of their natural environment that are essential to the construction of their collective identity. These utilitarian garments transcend their everyday function to incorporate a symbolic value that allows for the intergenerational transmission of community knowledge and reinforces the sense of belonging to the Nahua group.

The embroidery technique known as pepenado allows for the creation of complex compositions using contrasting colored threads that structure highly stylized phytomorphic and zoomorphic images. These elements constitute visual cultural signs that communicate concepts related to the Nahua worldview and the collective experience of inhabiting a territory marked by fertility and the constant presence of the sacred in nature.

Among the ornamental motifs that are repeatedly incorporated into the bodices of traditional blouses, the so-called mountain vine stands out as a plant element characteristic of the Cuetzalan landscape. Its representation in embroidery acquires an identity and symbolic function by being associated with the continuity of life, the connection between natural beings, and the historical memory of the Nahua people.

Despite the research carried out on the iconological analysis of the phytomorphic elements of the embroidery from Cuetzalan, Puebla, there are still several shortcomings. Further fieldwork with the embroiderers is needed to understand the oral meanings and the transmission of techniques. There is also a lack of comparative studies with other indigenous communities and analyzes of the role of women as creators of these symbols. It is important to investigate how ecological changes and the incorporation of industrial materials affect traditional designs. Furthermore, it is necessary to systematically document and disseminate ritual patterns and contexts for their preservation and reevaluation.

There are very few works related to the phytomorphic elements of the embroidery of Cuetzalan, Puebla: an iconological analysis; However, the few works that have been found have had a significant impact on the ability to carry out this research and achieve new findings on Nahuatl textiles and the vine.

One of the works found on Otomi textiles, reported by

Vega and Medina (

1991), presents a variety of detailed collections of ethnographies from the National Museum of Anthropology that record traditional techniques, motifs, and materials. Its main contribution is to provide a consultation tool that facilitates the preservation and comparative study of Otomi textile heritage. Among the results, the identification of regional patterns and the historical and cultural contextualization of each piece stand out. Furthermore, it allows us to observe the esthetic and functional evolution of textiles over time. The work contributes to the appreciation and dissemination of the ancestral knowledge of these communities.

Martínez (

2009) analyzes the geometric patterns present in textiles, ceramics, and architecture, linking them to the cultural identity of Puebla. Its main contribution is to show how design reflects local traditions, symbolism, and craft practices. Among the results, the identification of recurring elements and the interpretation of their historical and cultural meanings stand out. Furthermore, it demonstrates the adaptation of ancestral motifs in contemporary contexts. The study contributes to the appreciation and preservation of Puebla’s artistic and visual heritage.

Garavito García et al. (

2025) presents a work that explores how Nahua textiles function as carriers of collective memory and living cultural expression. It highlights that the motifs and colors of the textiles represent the indigenous worldview, where natural elements such as flowers, branches, and vines symbolize the connection between the earthly world and the sacred. The author highlights the continuity of ancestral techniques and their generational transmission as a form of cultural resistance. Among its findings, it shows that Nahua weaving not only preserves traditions but also community identities. The text provides a contemporary perspective that links art, history, and spirituality in indigenous textiles.

Furthermore, a study on textile art among the Nahua, reported by

Fernández Barrera (

1965), has been developed. This work highlights the importance of weaving as a central artistic and social expression in Nahua culture. The author demonstrates that textiles not only fulfill utilitarian functions but also symbolic ones, reflecting hierarchies, rituals, and tributes within the Mexica empire. It offers a historical reconstruction based on colonial sources, describing techniques, materials, and uses. Among its findings, it highlights the sophistication and economic value of Nahua textiles, although it acknowledges the scarcity of surviving examples. This work lays the foundation for the study of textile iconography as a vehicle for cultural and ritual meanings.

Likewise, other works have been found that impact this study; one of them is the one presented by

Martínez Cruz (

2021), which analyzes how pre-Hispanic Mexican textiles integrated art, technique, and symbolism as forms of cultural communication. The author shows that the motifs, especially the floral ones, express links with nature, ritual, and community identity. The main contribution lies in interpreting textile design as a visual language full of social and spiritual meaning. Among its findings, it provides evidence that textiles functioned as a material memory of Mesoamerican civilizations. The study thus proposes an iconological reading of textiles as bearers of history, esthetics, and worldview.

Barba de Piña Chán (

1992) offers an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the iconography of ancient Mexico, combining archeology, history, and ethnohistory. Its main contribution lies in systematizing the symbolic motifs present in objects, art, and crafts, including zoological, botanical, and ritual elements. The results show that these representations convey the cultural identity, collective memory, and political power of Mesoamerican societies. Furthermore, the relationship between art, religion, and social context in different regions was understood. This work establishes a valuable methodological framework for future studies of Mesoamerican iconography and iconology.

Sun and Liu (

2022), proposes to revitalize the artisanal tradition of rattan weaving through a contemporary transitional design approach. Explore the cultural hybridization between ancestral knowledge and modern sustainable design practices. It seeks to strengthen local identity and the transmission of community knowledge. It promotes social and environmental innovation through the responsible use of natural materials. Furthermore, it proposes collaborative strategies between artisans and designers. Taken together, it contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage and the development of a sustainable creative economy.

Likewise, studies of Nahua textile iconography from the state of Veracruz have been developed by

Bonilla Palmeros (

2018), which analyze the patterns, motifs, and techniques of the traditional textiles of these indigenous communities. Its main contribution lies in documenting and explaining the symbolic richness of the designs, highlighting elements that reflect worldview, identity, and local traditions. The results show how textiles function as carriers of cultural memory and artistic expression, preserving ancestral knowledge. Furthermore, it underlines the importance of preserving these practices to strengthen the appreciation of cultural heritage. The work thus offers a key resource for the study of Mesoamerican textile iconography and its social relevance.

Although there is very little information on the iconological analysis of the vine that is embroidered or reproduced in the Nautl textile, this article focuses on its symbolism and cultural significance.

In this sense, and considering the centrality of the vine in the textile production of Cuetzalan, the main contribution of this article consists of analyzing the symbolism of this phytomorphic motif in the embroideries created by the artisans of the Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani collective. The study considers both its formal characteristics and its cultural significance, with the purpose of approaching a symbolic interpretation of the vine from an iconological perspective, complemented by information obtained through ethnographic work.

The article is organized as follows: in the second section, a general description of the region and the location of the municipality is presented to understand the geographical and cultural context. The third section presents the theoretical framework and methodology used in the research. In the fourth section, the analysis of the phytomorphic motif of the vine is developed, which comprises three levels: first, the pre-iconographic description of the different modules embroidered on the traditional blouses; Subsequently, the iconographic analysis focused on the conventional meanings of the motif; And finally, the iconological interpretation aims to unravel the symbolic values associated with the plant symbol. Finally, in the fifth section, the general conclusions of the study are presented.

2. Geographical and Cultural Context of Cuetzalan, Puebla

The research is being conducted in the municipality of Cuetzalan del Progreso, located in the Sierra Norte of the state of Puebla, a mountainous region that borders the states of Hidalgo and Veracruz (see

Figure 1). Its rugged topography, the constant presence of fog, and the humid climate have fostered abundant vegetation that defines the landscape and local ways of life. In this environment, nature not only constitutes the material means of subsistence but also a symbolic source of inspiration that permeates the cultural and esthetic practices of the community.

The Sierra Norte region of Puebla is distinguished by its high density of the indigenous population and by the persistence of a community organization that articulates work, collective life, and daily cultural practices. In this context, the Nahua population—who call themselves maseualmej “Nahuas of the Sierra Norte”—maintains the use of Nahuatl as their mother tongue for communication and the transmission of knowledge, an element that constitutes an essential component of their ethnic identity. The Nahua worldview conceives of the earth as a living and sacred entity, where natural elements actively participate in the balance of the world and in the reproduction of life.

In the economic sphere, agriculture continues to be the main activity, focusing on the cultivation of corn and coffee. In addition, artisanal production, especially the making of embroidered textiles, plays a fundamental role in the domestic economy and in cultural preservation. Embroidery, beyond its productive dimension, constitutes a symbolic and pedagogical practice: its learning is transmitted from generation to generation within the family nucleus, consolidating networks of female knowledge that strengthen community cohesion.

Traditional dress is an essential part of the daily life of Nahua women in Cuetzalan (see

Figure 2). Embroidered blouses, used both in daily routines and on special occasions, function as a marker of identity and as a material expression of the link with nature. Each garment incorporates phytomorphic motifs inspired by the environment—flowers, branches, fruits, and vines—that condense knowledge transmitted through textile practice. These visual elements materialize the relationship between the body, the land, and collective memory, making embroidery a practice of cultural affirmation rather than a simple adornment.

The traditional technique of pepenado, used for making blouses, consists of the embroidery of counted stitches on a fabric base. This method requires precise technical knowledge, as the artisans mentally calculate the number of stitches needed to construct the designs. Pepenado allows for the creation of geometric and rhythmic compositions that reproduce, through continuous lines, the forms of the plant world. Thus, the mountain vine, a recurring motif in the textiles of Cuetzalan, adapts naturally to the modular and serpentine logic of the technique.

In Cuetzalan, Nahua women have transformed artisanal production into a form of economic and social organization, articulating family and community networks to guaranty the continuity of their knowledge and access to fair markets. Among these initiatives, the Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani Cooperative stands out, a name in Nahuatl that means “Indigenous women who support each other”, founded in 1992 by a group of around one hundred Nahua women. Its main objective is to strengthen women’s economic autonomy through the production, marketing, and dissemination of textile and herbal crafts while preserving traditional knowledge and native culture.

Within the cooperative, the members share and exchange ancestral knowledge about traditional techniques, such as pepenado embroidery, backstrap loom weaving, and jonote basketry, which constitute material expressions of identity and cultural continuity.

As part of its organizational strategy, the cooperative created the Hotel

Taselotzin 1 in 1997, a space managed directly by the women of the collective. This project, in addition to offering lodging services, functions as a sales and promotion point for local crafts, establishing solidarity distribution channels and ensuring fair prices for the producers. The hotel also serves as a collection and administrative coordination center, strengthening the sustainability of the collective project. Women’s participation in the social and economic spheres of Cuetzalan is a determining factor in community development. In this region, Indigenous cooperatives are consolidating themselves as spaces for training, exchange, and autonomous management aimed at guaranteeing a dignified life and preserving the cultural heritage of the Sierra Norte. The

Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani, legally constituted as a Social Solidarity Society, serves as a model of autonomy and cultural resistance, promoting job creation, the revaluation of textile knowledge, and the affirmation of Nahua identity through embroidery.

Thus, the traditional embroidery of Cuetzalan is understood not only as a cultural practice that structures the daily life of Nahua women but also as a symbolic language that expresses their relationship with nature and a worldview in which life is conceived as continuity. Both dimensions guide the analysis developed in the following sections.

3. Theoretical and Methodological Framework

The analysis of traditional embroidery from Cuetzalan is based on the theoretical and methodological framework of Erwin Panofsky, who proposed that works of art can be understood through their relationship to the sociocultural context that produces them. Although the original focus was on Western art, the analytical framework is relevant for interpreting visual expressions that transcend this sphere, including Nahua textile iconography, because it enables us to recognize how the symbols used by embroiderers are linked to specific cultural systems.

From the perspective of visual studies, the image constitutes a means of classifying, transmitting, and making comprehensible complex or hidden phenomena

Costa and Moles (

1991). Its analysis implies considering that, within any system of visual communication, content is inseparable from form. Images, understood as cultural products, require an interpretation that allows access to the deep meanings that these images convey.

Acaso (

2009). In this sense, the image is defined as a system of representation in which one element substitutes for or recreates another aspect of reality, even going so far as to symbolically construct it.

Dondis (

2000) argues that visual messages can communicate information in three ways: the direct representation of recognizable elements of the environment; abstraction, based on formal reduction to rhythm, line, or color; and symbolism, based on culturally shared visual codes. From this perspective, traditional embroidery can be understood as a coded visual language through which worldviews, esthetic values, and social meanings are expressed. Thus, embroidery is conceived as a symbolic discourse that alludes to Nahua identity and worldview.

The iconological method allows us to approach embroidery as an esthetic expression that integrates collective meanings. This work applies its three analytical levels:

Pre-iconographic description, focused on the formal aspects of artistic motifs.

Iconographic analysis is centered on the conventional meanings of symbols.

In addition, the contributions of the anthropology of art in Mesoamerica are revisited.

López Austin (

1980) argues that the plant world actively participates in the symbolic construction of Nahua thought, understood as a source of life, movement, and regeneration. Similarly,

León-Portilla, Miguel (

1992) points out that nature, especially plants linked to growth, embodies a vital force that connects the earthly and celestial planes. These elements are essential for situating the vine motif within a broader Mesoamerican iconographic tradition.

Based on these theoretical references, the analysis of the vine in the traditional blouses of Cuetzalan simultaneously addresses its visual form, shared meanings, and its role within a context in which nature is conceived as a living entity and a repository of central symbolic values in Nahua culture.

The research is conducted using a qualitative approach, employing ethnographic and visual analysis tools. Fieldwork was carried out in three stages. The first stage took place in September 2018, with an initial visit to Cuetzalan to get to know the region, delimit the topic of study, and establish contact with members of the Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani collective, in particular, with the administrator of the Taselotzin hotel, with the purpose of identifying the most representative textile motifs and embroidery techniques.

The second season took place from 23 to 30 July 2019, during the annual

Tikijkiti Tonemilis meeting, “Weaving our lives” (

Figure 3), during which embroidery practices, organizational dynamics, and the use of traditional clothing in community life were observed. During this stay, discussions were held with the embroiderers about the most characteristic motifs of the blouses, highlighting the recurring presence of flowers and animals, as well as the relevance of phytomorphic elements. This information allowed for the selection of the study motif to be defined.

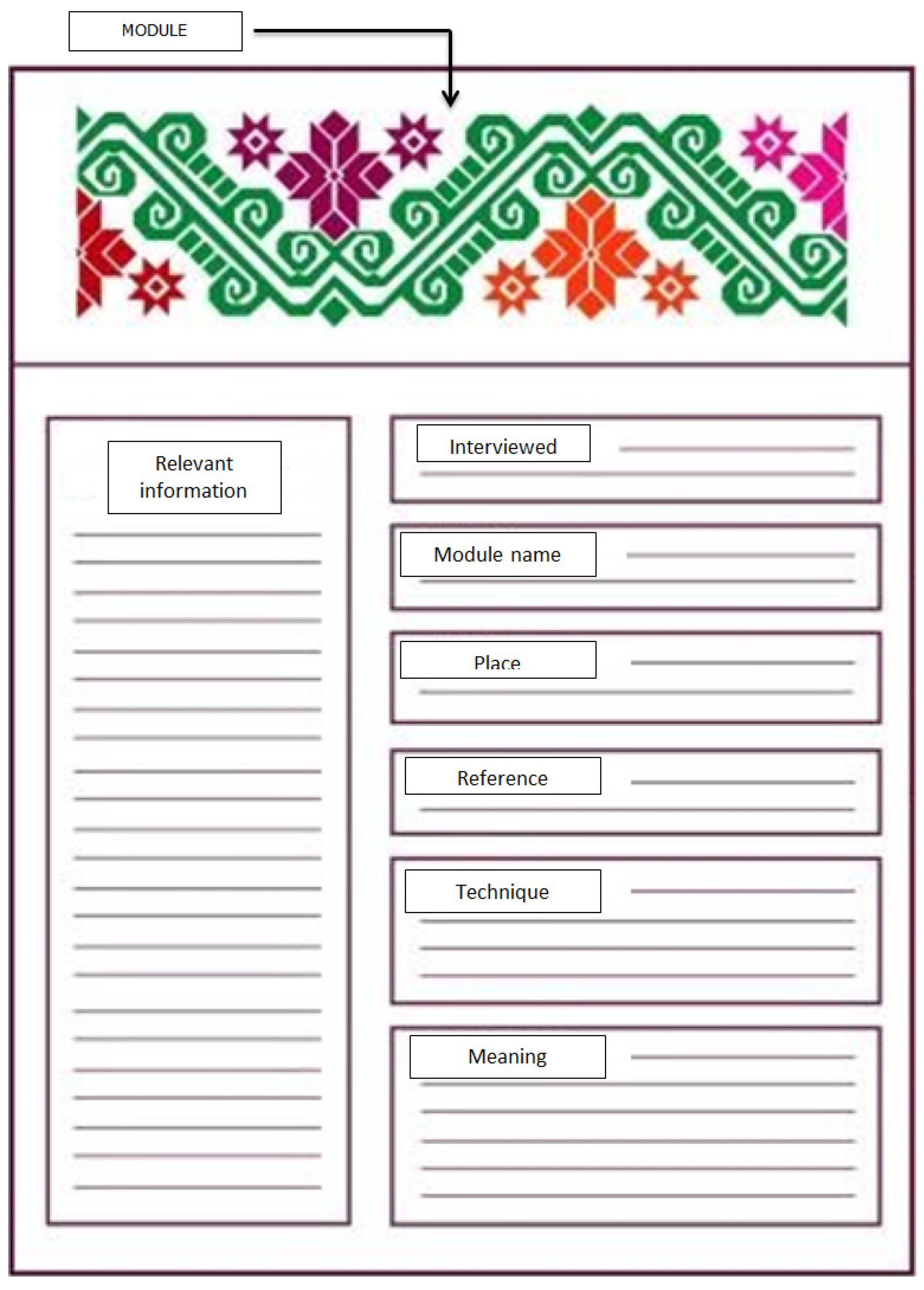

During that same season, the borders or modules (see

Figure 4) present on the bodices of traditional blouses were recorded by means of photographs Subsequently, descriptive sheets were prepared (see

Figure 5) with formal, technical, and ethnographic information.

The third field season took place in October 2019 and focused on interviews with visual material. These cards were presented to the embroiderers for their recognition and interpretation, which allowed for the identification of the vine as one of the motifs with the greatest antiquity, permanence, and symbolic weight in traditional embroidery.

The iconological analysis of the vine was complemented by interviews conducted with members of the collective. The artisans explained the symbolic relevance of the phytomorphic motif and narrated its relationship with the agricultural and spiritual lives of the community. Through these testimonies, it was confirmed that the vine symbolizes the continuity of life, the union of the natural planes, and the persistence of ancestral textile knowledge in the present.

4. Analysis of the Three Levels

This section develops the analysis of the phytomorphic motif of the mountain vine, based on the three levels proposed by Erwin Panofsky (iconological method): pre-iconographic description, iconographic analysis, and iconological interpretation.

4.1. Pre-Iconographic Description

The modules with phytomorphic motifs recorded on the traditional blouses of Cuetzalan are described below. Each composition is made using the pepenado technique on cotton fabric and features the vine of the mountain as the central structural element. This motif is usually embroidered in green, which is associated with the vegetation of the region. The figures that accompany the vine—such as flowers, branches, and fruits—form a visual repertoire that expresses the close relationship between nature and textile practice in the region.

The module corresponding to the mountain vine and the pine tree (see

Figure 6). It is characterized by a symmetrical composition of great formal complexity. The tree, constructed using rhomboidal shapes, occupies the central axis and serves as the element with the greatest visual weight. At the bottom, geometric figures extend laterally, repeating the motif in a rhythmic pattern of rotation. The combination of the curvilinear lines of the vine and the angular elements of the pine creates a sense of upward movement and continuity, reinforced by the balanced arrangement of the spoon flower at the ends of the design.

In this module (see

Figure 7), a horizontal composition is observed in which two phytomorphic elements are repeated in the same position and direction from left to right. Each flower is composed of a circular center and eight rhomboid petals arranged radially. The vine, represented as a plant guide with organic lines, unifies the figures through a continuous stroke that brings rhythm and fluidity to the whole.

The central design of the module (see

Figure 8) features a main flower structured around a central oval, surrounded by secondary geometric motifs. On either side, composite flowers with rhomboid shapes are reflected in rotation, creating a balanced and dynamic composition. The vine serves as the unifying element, represented by lines of varying thickness that convey a sense of fluidity and plant growth. This motif stands out for its formal harmony and the visual continuity provided by the vine’s serpentine lines.

The module (see

Figure 9) of the pumpkin flower is distinguished by its ordered geometric structure. The main flower, composed of mirrored rhomboid shapes, is repeated throughout the design, generating a sense of order, symmetry, and movement. The vine, with its green pattern and modulated lines, provides compositional unity and suggests the idea of continuous growth. The embroiderers explain that, although creative variations have been incorporated into the plant, the serpentine direction of the vine, from top to bottom, remains an essential feature of the motif.

This module (see

Figure 10) presents a composition in which a central flower stands out due to its greater visual weight. The geometric petals of a rhomboidal type surround a small rhombus that represents the center of the flower. On the sides are two joined triangular figures, similar to stars, which provide lateral balance. The vine, represented with lines of varying thickness, gives rhythm and continuity to the whole.

The alternation between floral and stellar elements reinforces the symbolic relationship between earth and sky in textile design.

In this composition (see

Figure 11), the spoon flower, used by the Nahua people to adorn ritual altars, is repeated sequentially. Each flower is constructed from simple geometric shapes and is wrapped by the trail of the vine, which is repeated continuously. The plant acts as a protective frame for the floral motif, maintaining a constant visual balance throughout the composition. This design demonstrates the connection between embroidery and the ceremonial sphere, as the spoon flower is associated with permanence and the sacred nature of life.

The module (see

Figure 12) of the wild grape is made up of seven oval shapes that represent the fruits, arranged in rotation around the plant guide. The vine maintains a fluid line of continuity, linking the elements through a formal balancing operation.

In this module (see

Figure 13), cotton occupies the central axis and is represented by five small squares around a larger figure, alluding to the open fruit of the plant. Symmetrical rhomboids are placed on either side, while the vine, by surrounding the whole, provides a feeling of harmony and stability. This motif stands out for its closed and balanced composition, where the continuity of the vine links the different elements in the same visual rhythm.

4.2. Iconographic Analysis

At the iconographic level, the motif of the mountain vine is identified as a plant symbol deeply linked to the worldview and daily life of the artisans of the collective. In the artisans’ discourse, the flowers that accompany this element are considered symbols of truth, an expression that refers to the relationship between beauty, knowledge, and spirituality. The design of these motifs does not respond to a merely decorative intention but rather operates as vehicles of symbolic communication, through which emotions, knowledge, and shared values within the community are manifested.

Embroidery is a practice of affirming identity and a means of conveying joy and harmony, qualities that are part of the festive and ritual character of the Nahua culture of Cuetzalan. In the collected testimonies, the vine is described as a plant that grows in orchards and in the mountains, considered a sacred element for its ability to intertwine and bloom around trees, a natural gesture that symbolizes the continuous movement of life. This concept is visually materialized in the sinuous and intertwined lines of the embroidered design, which evoke rhythm, continuity, and vitality.

In one of the testimonies, the vine is associated with Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, a deity related to wind, knowledge, and renewal. This individual interpretation suggests a symbolic reading of the motif as a metaphor for movement and regeneration, since the curvilinear and serpentine stroke of the embroidered vine visually represents the upward and downward flow of energy, evoking the idea that life unfolds amid constant transformations.

Overall, the iconographic analysis allows us to recognize the vine as a symbol of union, fertility, and permanence, in which the observation of the natural environment and the spiritual conceptions present in traditional Nahua embroidery converge. Its recurrence in the textiles of Cuetzalan confirms its role as an emblematic motif and bearer of cultural memory within the regional iconographic repertoire.

4.3. Iconological Interpretation

At the iconological level, the motif of the vine transcends its formal representation and ornamental value to become a visual metaphor for the continuity of life and the balance between the natural and spiritual planes. Its constant presence in the traditional embroidery of Cuetzalan reflects a worldview in which nature, life, and the sacred are intimately intertwined. The sinuous shape of the vine, which ascends, descends, and intertwines, expresses the principle of movement that, according to the Nahua worldview, sustains existence and connects the realms of the sky, the earth, and the underworld

Maffie (

2014).

In this interpretation, the act of embroidering acquires a ritual and symbolic value: each stitch materializes a relationship with the earth, with the plants, and with the agricultural cycles that organize community life. In this way, embroidery not only produces an esthetic garment but also visually reproduces a vision of the world in which natural elements are bearers of meaning and memory.

One particular testimony associates the vine with Quetzalcoatl, a Mesoamerican deity linked to wind, knowledge, and cyclical regeneration. This correspondence reinforces the interpretation of the motif as a symbol of rebirth and the flow of vital energy, where the undulating line and the intertwining of the design evoke the dynamics of the cosmos and the reciprocity between beings.

From an iconological perspective, the vine can be understood as a structuring symbol of Nahua cultural identity, in which the sensory experience of the environment, symbolic thought, and textile practices as forms of knowledge converge. Thus, the embroidered motif not only refers to a plant from the local environment but also condenses a way of thinking and representing the world, transmitted through generations by means of artisanal practices.

In summary, the iconological analysis allows us to understand the vine as an emblem of the continuity of life, collective memory, and the sacred relationship with nature, reaffirming the value of embroidery as a visual language that communicates the fundamental principles of the Nahua worldview.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of traditional embroidery from Cuetzalan made it possible to understand that the motif of the mountain vine constitutes a central element within the visual language of the Nahua artisans. Based on Erwin Panofsky’s iconological method, it was possible to identify the three levels of meaning that structure this symbol: the formal dimension of the design, the symbolic reading linked to the flowers, the serpent, and life, and the deep interpretation that relates it to the Mesoamerican worldview.

The results of the fieldwork show that the vine is not only a decorative motif but also an expression of continuity and vital movement, associated with plant growth, agricultural cycles, and the idea of regeneration. Its repeated presence in traditional textiles confirms its function as a bearer of cultural memory and as a symbol of collective identity within the visual repertoire of Cuetzalan.

From an iconological interpretation, the vine can be understood as an emblem of the relationship between the natural and spiritual planes, where nature is conceived as a living and sacred entity. This textile motif embodies the Nahua vision of the universe as a dynamic system in equilibrium, sustained by intertwined forces—just like the vine itself, which ascends, descends, and embraces other forms of life.

Furthermore, the study reaffirms the value of embroidery as a form of visual thinking and symbolic knowledge, in which the women of the Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani collective express an esthetic and philosophical understanding of the world. Through their designs, these creators not only preserve a traditional technique but also keep alive a way of conceiving life and the sacredness of nature.

Finally, the analysis of the vine reveals the capacity of Nahua textiles to articulate esthetics, worldview, and memory, consolidating themselves as living testimonies of the identity and cultural continuity of the municipality of Cuetzalan.