‘ART’: What Pollock Learned from Hayter

Abstract

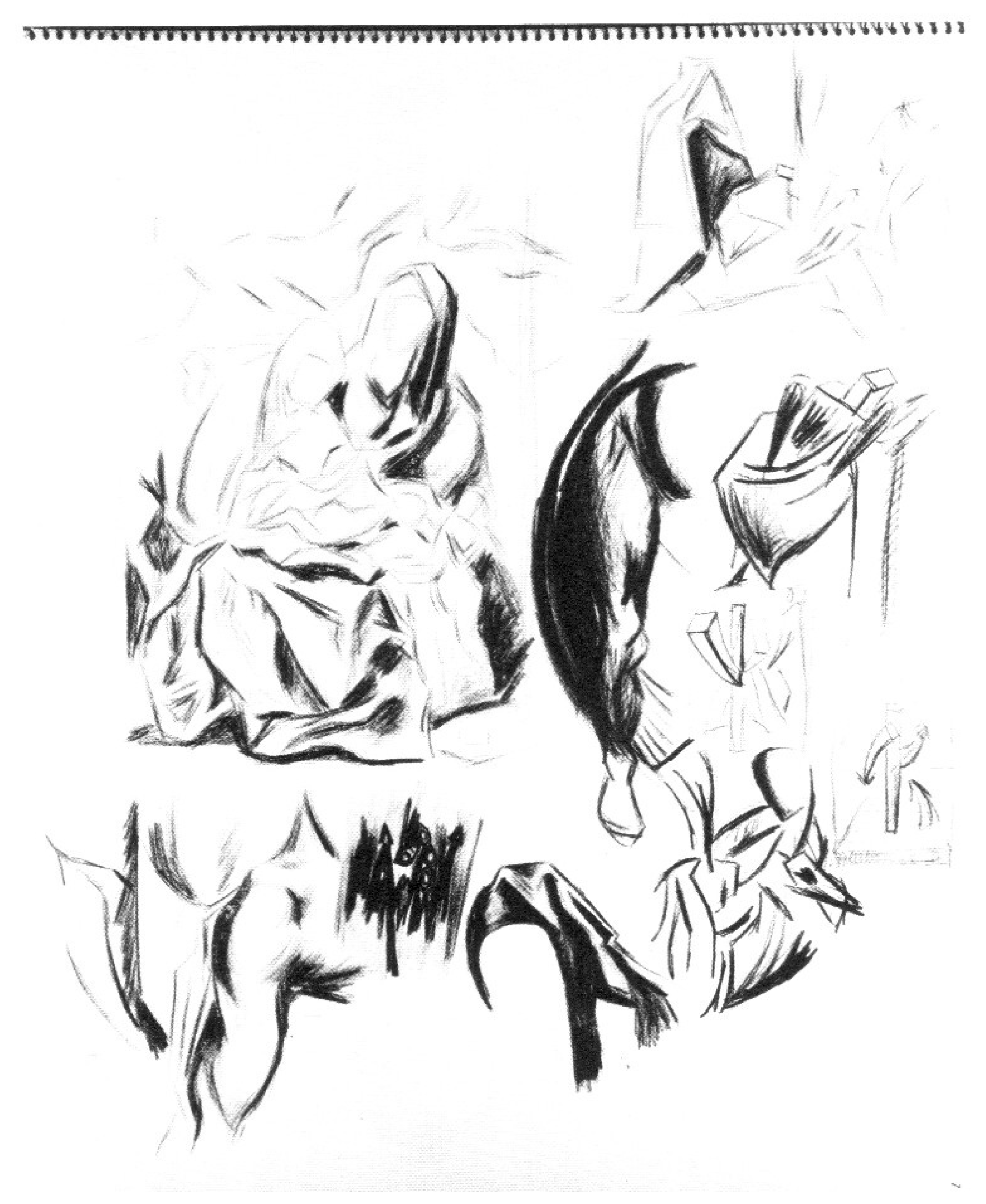

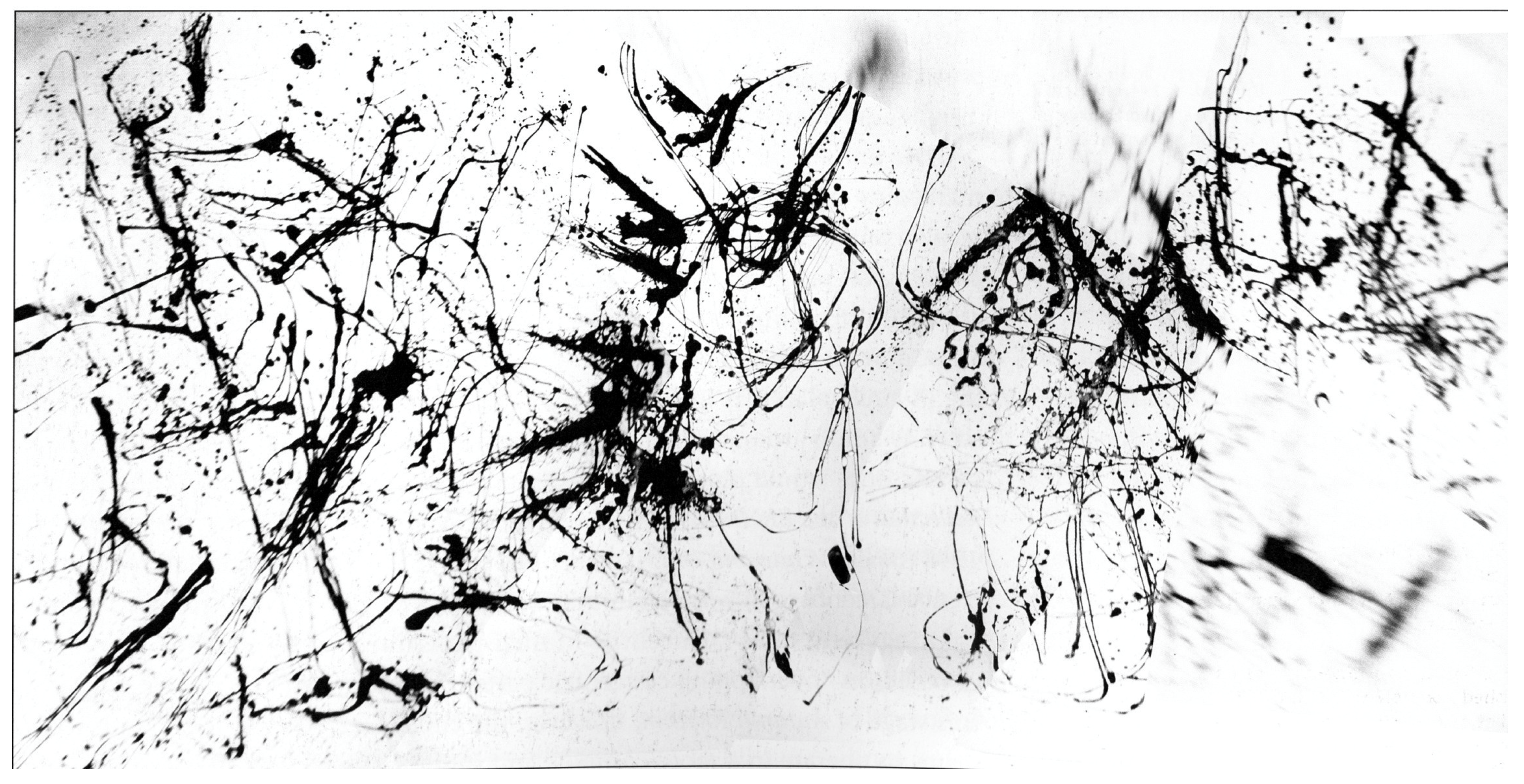

1. The Three-Dimensionality of Pollock’s Poured Lines

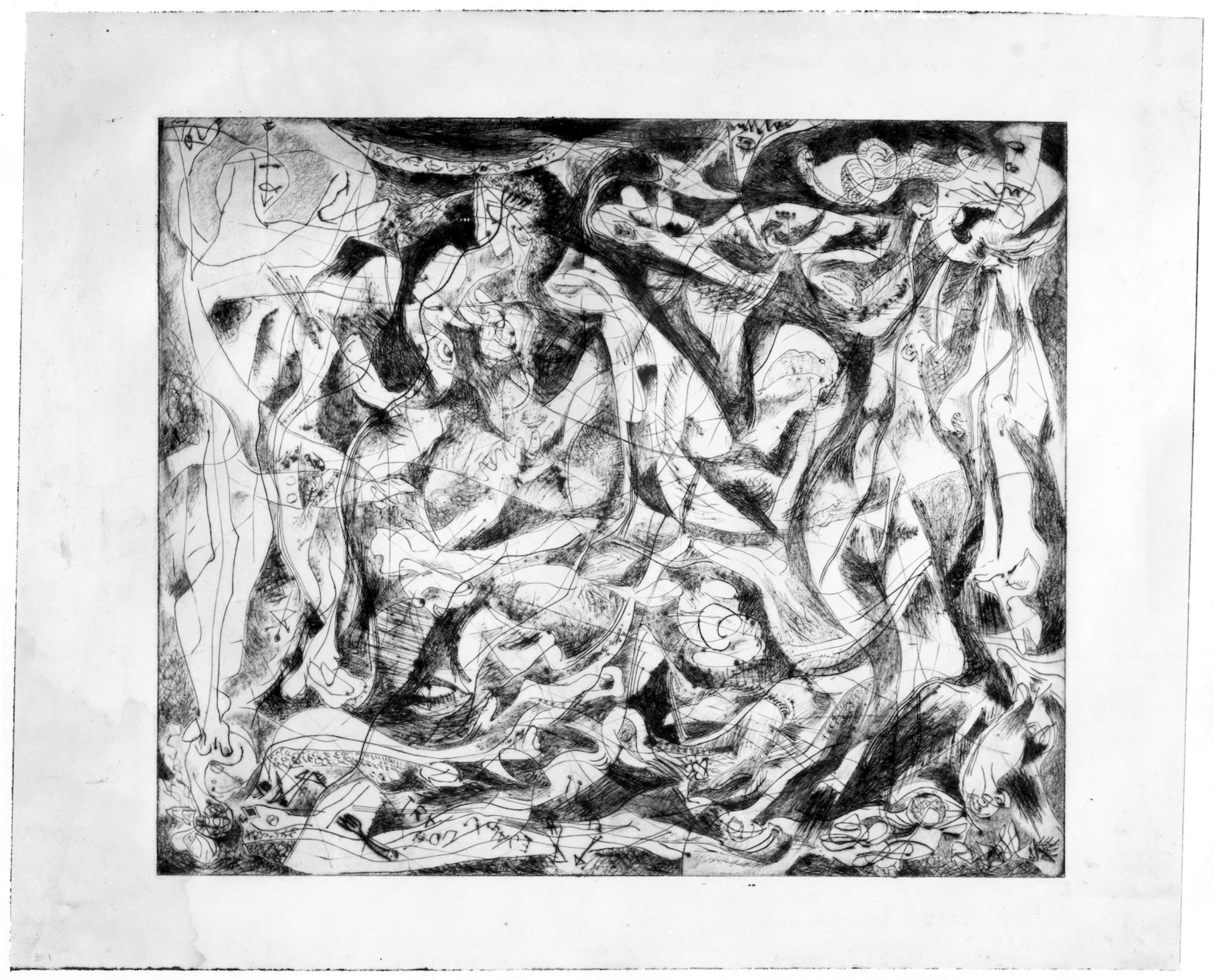

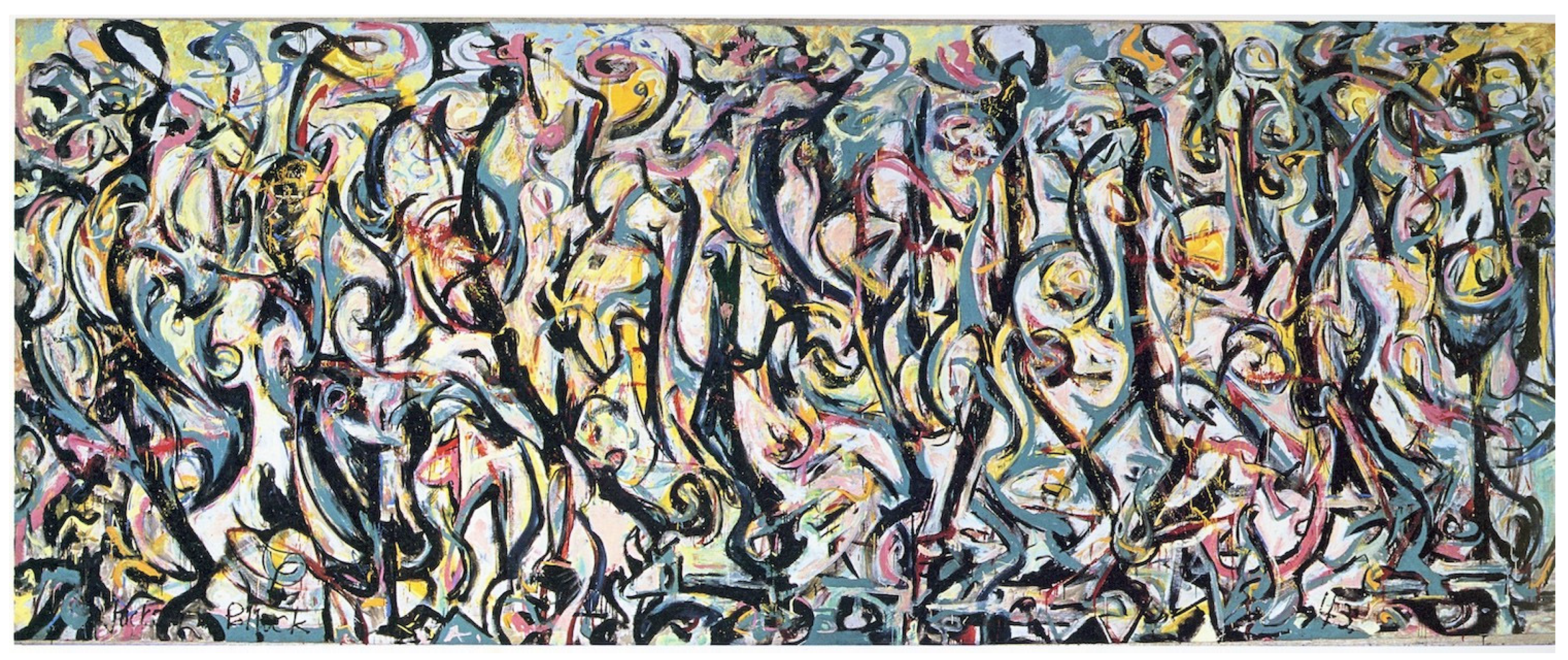

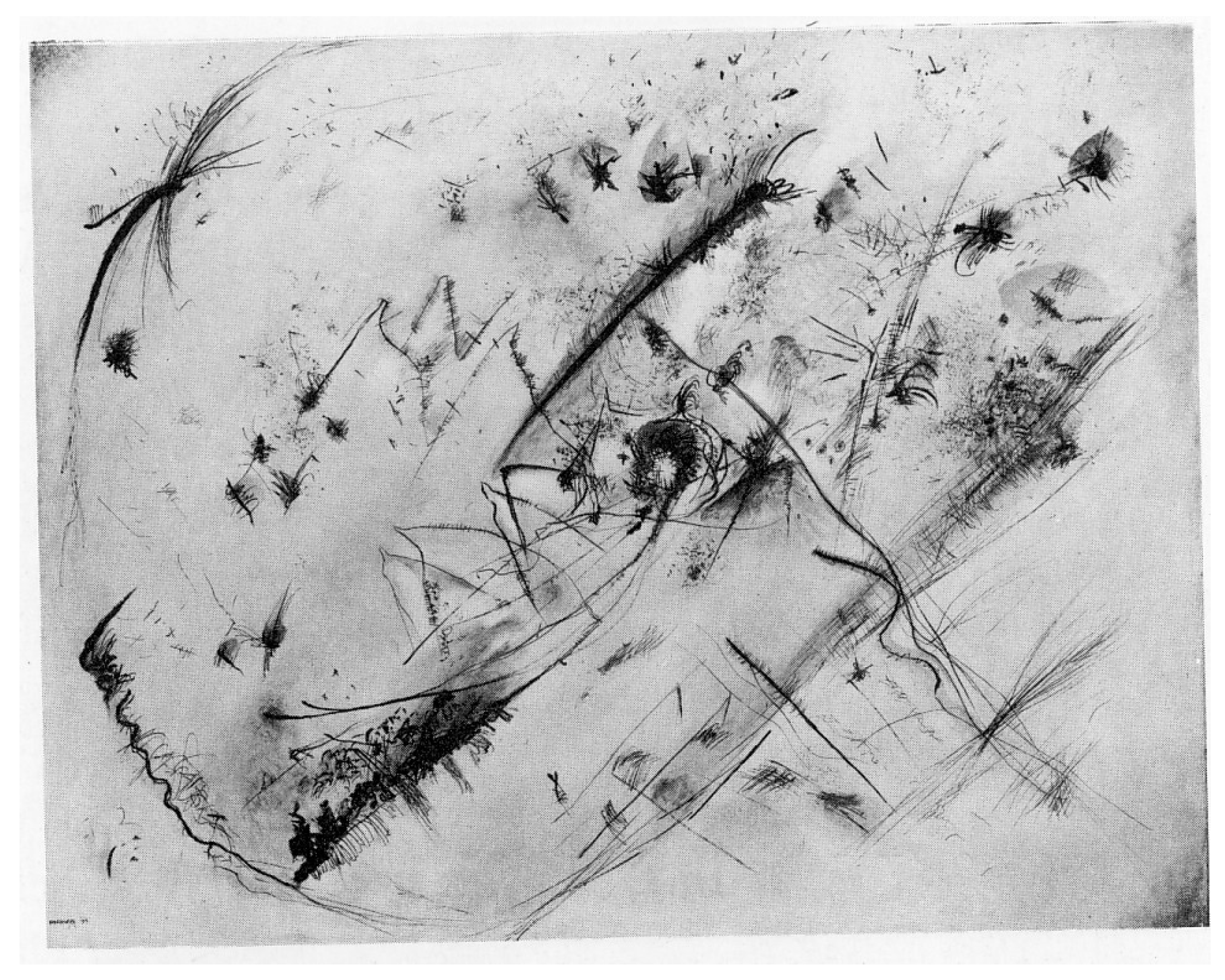

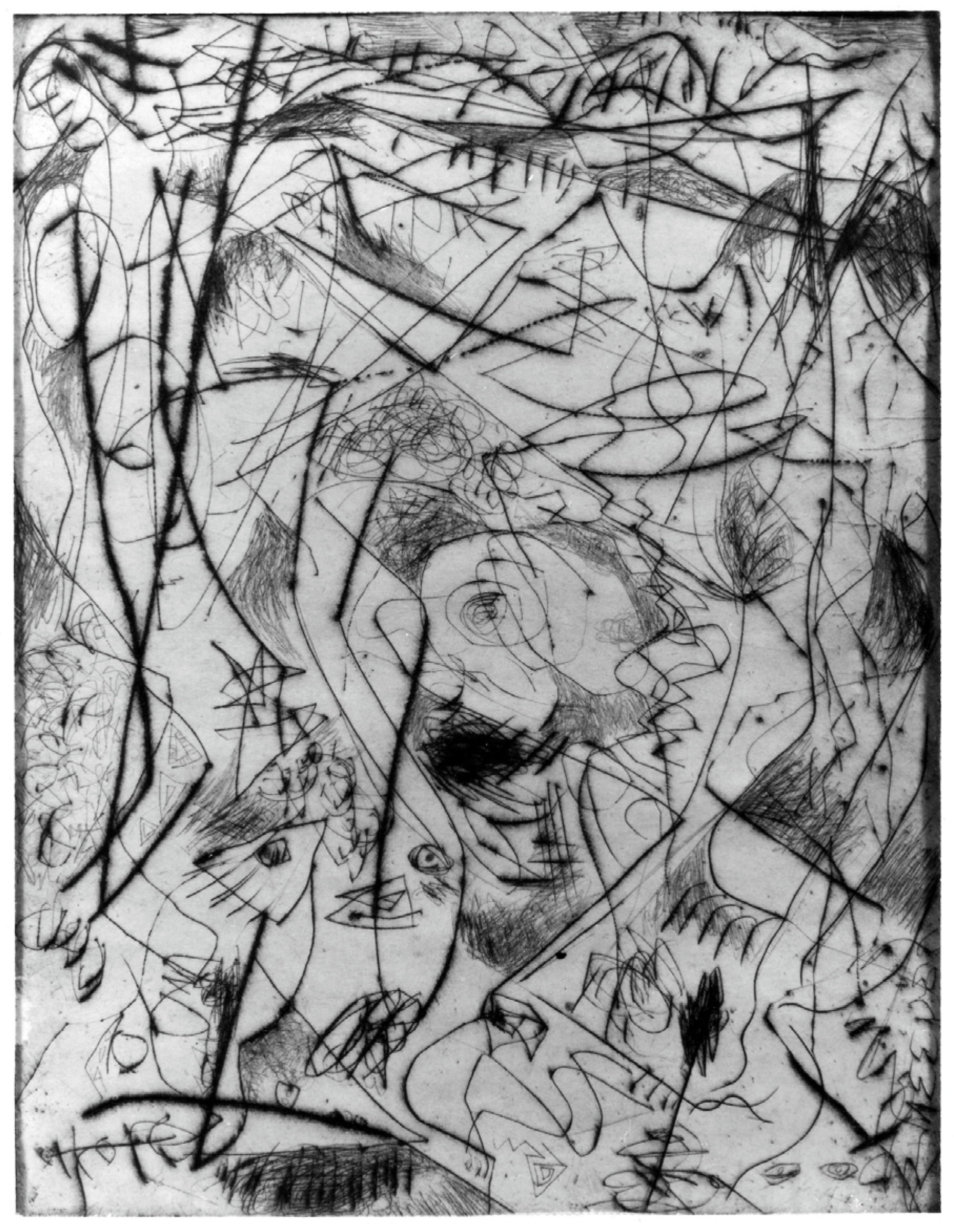

2. Atelier 17 and Pollock’s ‘ART’

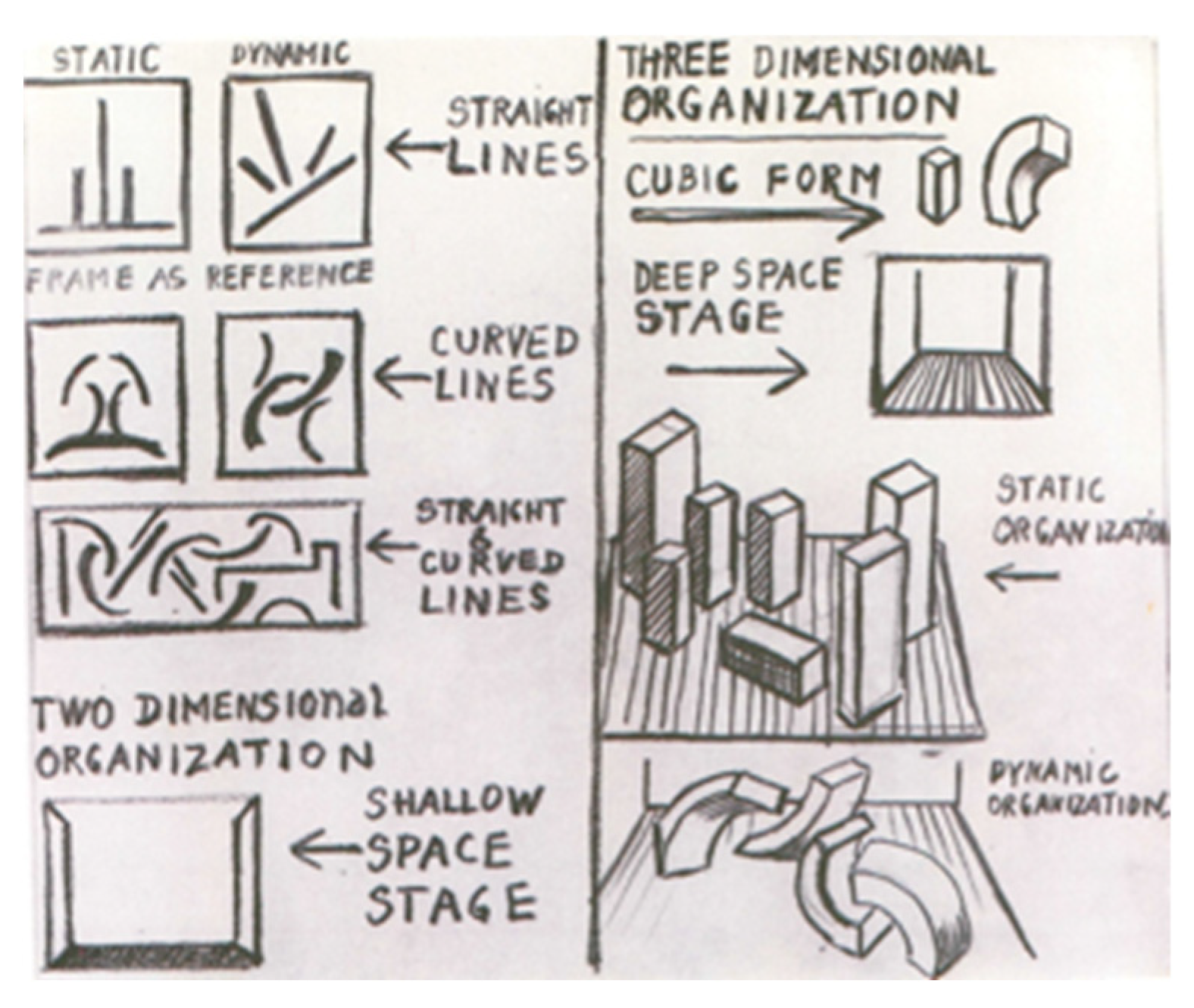

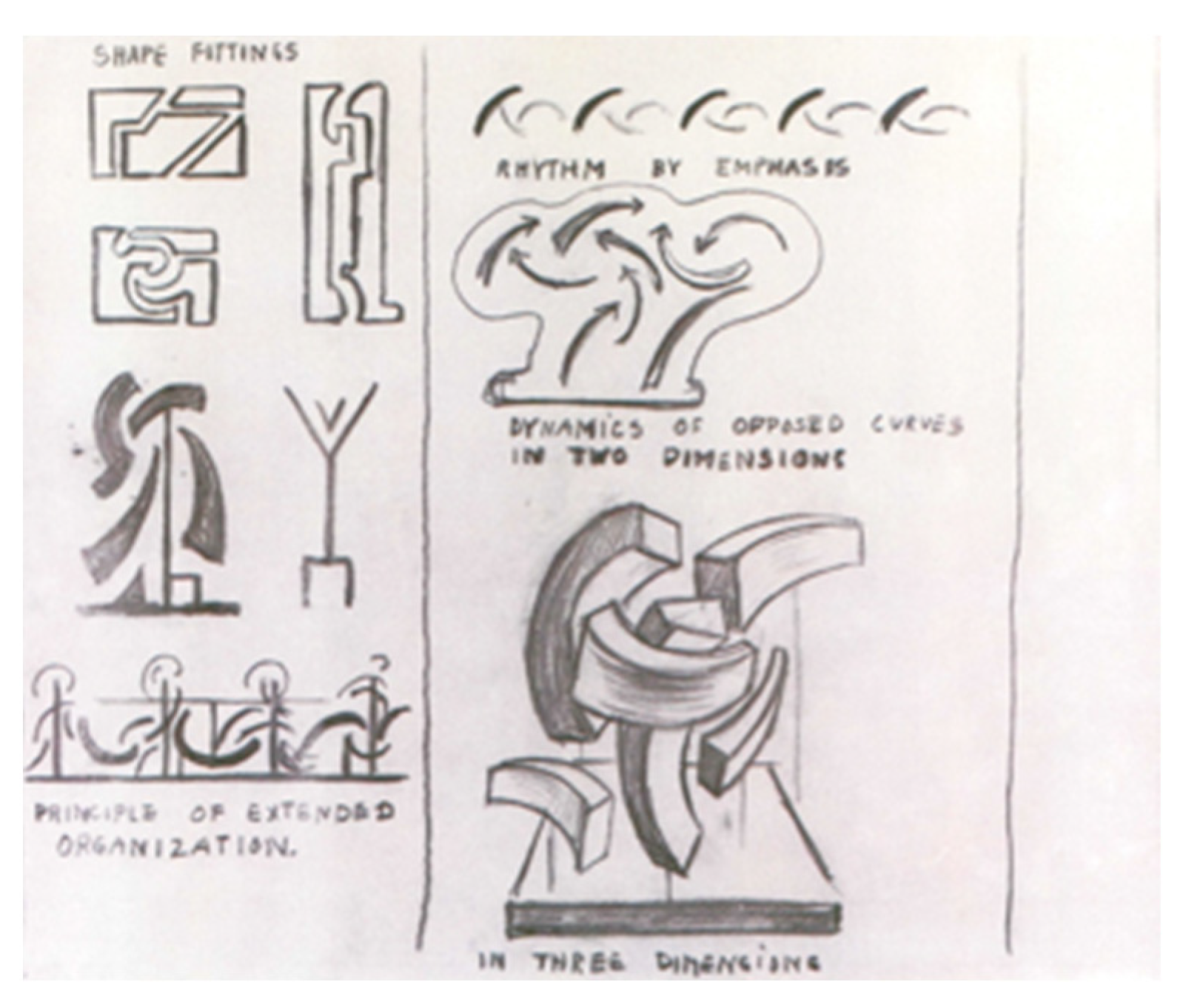

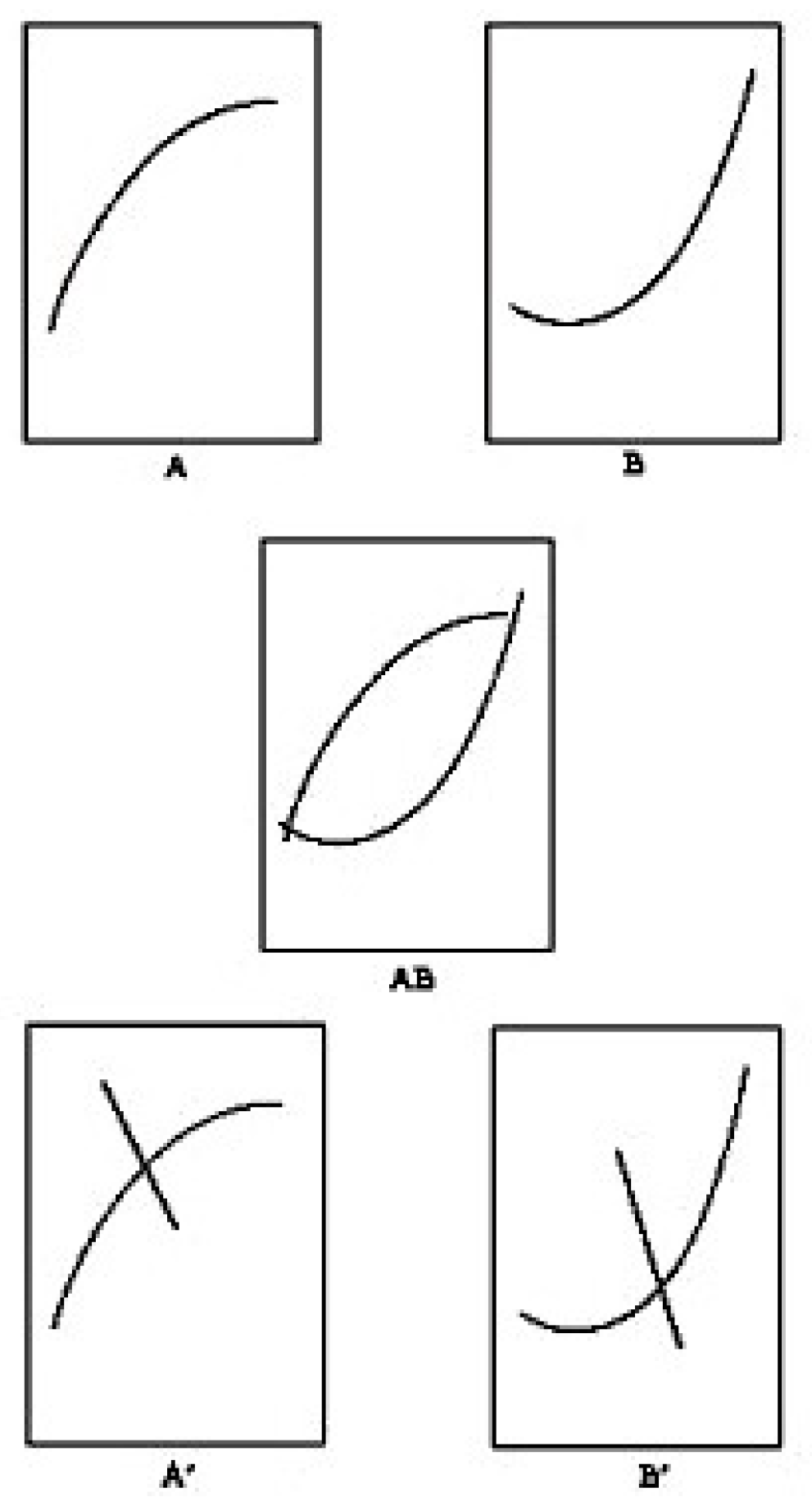

3. Benton’s Space Stage vs. Hayter’s “Space of the Imagination”

4. “The Concrete Construction of Space”

5. Erotic Meaning of Engravings

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See formal analysis in (Carmean 1978, p. 140). |

| 2 | See (Darwent 2023, ch. 5) “Pollock Makes a Print”, pp. 132–59. For an overview of Pollock’s printmaking throughout his career, see (Williams and Williams 1988). |

| 3 | I refer to the prints by their Catalogue Raisonné [abbreviated as CR] numbers, as given in (O’Connor and Thaw 1978, vols. 1–4). For the history of the eighteen prints reproduced in the Catalogue Raisonné see p. 142. |

| 4 | See (Fitzgerald 1999). Moser writes that Pollock knew about Hayter since the late 1930’s, first through his work, and through reports from their mutual friend John Graham; (Moser 1978, p. 6). |

| 5 | Quoted in (Solomon 1987, pp. 149–50). |

| 6 | (Fichner-Rathus 1982, p. 165) also points to CR 1077 as “the most ambitious and accomplished print in the series.” Appreciating CR 1077 as a breakthrough work, Bernice Rose provides a thorough formal analysis of it in terms of cubism expanded by an awareness of Masson, Miro and Kandinsky; (Rose 1980, pp. 13, 15). |

| 7 | (Meier 1984, p. 137) also notes the presence of the word “art” in this print. For another instance of a significant play with letters, see Pollock’s signature in CR 1024, c. 1943. |

| 8 | Following the Getty Museum’s intensive conservation of Mural, Y. Szafran, L. Rivers, A. Phenix, and T. Learner observe: “The dark brown Bentonian structure of Mural—the tall, thin, stick figures that process across the work from right to left become more calligraphic as they proceed—can be readily sensed in normal viewing of the painting.” See Y. Szafran, L. Rivers, A. Phenix, and T. Learner, Jackson Pollock’s Mural: Myth and Substance, in (Szafran et al. 2014, p. 49). Both Ellen Landau and David Anfam recognize Benton’s influence on Mural, while Landau additionally proposes that of Hayter. Both emphasize the important influence of motion photography, and Anfam that of aerial photography; (Landau 2014, pp. 19–20, 22, 29 n.30); (Anfam 2015, pp. 37, 58ff, 97–98). |

| 9 | Thomas Hart Benton presented his theory of pictorial composition in a series of articles: (Benton 1926, 1927). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | (Darwent 2023, p. 148). On a growing interest in Jungian psychology in Surrealist circles in New York in the early 1940s, see (Darwent 2023, pp. 67, 71–72, 117). For the impact of Jungian thought on Pollock’s art, see (Langhorne 2023). |

| 12 | See (Greenberg 1961a, p. 111). Also see (Hayter 1945b). Kandinsky’s Light Picture, illustrated here, was since 1939 in the collection of the Museum of Non-Objective Art, where Pollock worked in 1943. |

| 13 | Quoted in (Potter 1985, pp. 76, 80). |

| 14 | On Pollock as the rising star in modern art, see (Greenberg 1945, p. 16). On advancing a post-cubist art, see (Greenberg 1947, pp. 124–25). For Pollock’s position in his history of modernism, see (Greenberg 1955, pp. 225–26). |

| 15 | Note that Darwent illustrates CR 1081 (P18) only as it was printed posthumously in 1967. He titles it Untitled (6), c.1944–5, appreciating it as a moment in Pollock’s oeuvre when figuration gives way to an all-over linear mark making. See (Darwent 2023, pp. 156, 190). |

| 16 | In the spring of 1944 Kadish remembers the discord in the relationship between Pollock and Krasner. See Naifeh and Smith, Interview with Kadish, quoted in (Naifeh and Smith 1989, pp. 483–84). |

| 17 | (Darwent 2023, pp. 156, 188, 190). With Untitled (4) Darwent refers to the first state of ‘ART’ which was printed by Pollock and Hayter at Atelier 17; see (O’Connor and Thaw 1978, vol. 4, p. 146). In this article I discuss the second and more developed state of ‘ART’, CR 1077 (P16), which was printed by Pollock and Hayter at Atelier 17. |

| 18 | On earlier manifestations of the female beast in She-Wolf, see (Langhorne 2013, pp. 155–56). |

| 19 | Lee Krasner, quoted in (Rubin 1979, p. 86). |

| 20 | Interview with Barbara Kadish, (Potter 1985, p. 81). |

| 21 | Interview with May Tabak, (Potter 1985, p. 190). For date of Development of the Foetus, see (O’Connor and Thaw 1978, vol. 1, p. 138). See also (Naifeh and Smith 1989, p. 531). |

| 22 | For a more extensive discussion of Pollock’s relationship to nature, especially in late 1944, see (Langhorne 2012, pp. 118–34) and and especially in 1949, see (Langhorne 2011, pp. 227–38). |

| 23 | For further discussion of experimental poured paintings in 1943, see (Langhorne 2023). |

References

- Anfam, David. 2015. Jackson Pollock’s Mural: Energy Made Visible. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, Thomas Hart. 1926. The Mechanics of Form Organization in Painting, Parts I–II. The Arts 10: 285–89, 340–42. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, Thomas Hart. 1927. The Mechanics of Form Organization in Painting, Parts III–V. The Arts 11: 43–44, 95–96, 145–48. [Google Scholar]

- Carmean, E. A. 1978. Jackson Pollock: Classic Paintings of 1950. In American Art at Mid-Century: The Subjects of the Artist. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 127–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. J. 1999. Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, James. 1999. No Chaos Damn It. In Jackson Pollock: New Approaches. Edited by Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel. New York: Harry N. Abrams, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Darwent, Charles. 2023. Surrealists in New York: Atelier 17 and the Birth of Abstract Expressionism. New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Fichner-Rathus, Lois. 1982. Pollock at Atelier 17. The Print Collector’s Newsletter 13: 162–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J. 1999. ‘Biographical Note’, A Finding Aid to the Reuben Kadish Papers, 1851–1995. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Archives of American Art. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1945. Review of Exhibitions of Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Pollock. The Nation, 7 April 1945. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 2, pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1947. Review of Exhibitions of Jean Dubuffet and Jackson Pollock. The Nation, 1 February 1947. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 2, pp. 122–25. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1955. American-Type Painting, Partisan Review, Spring 1955. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 3, pp. 217–36. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1961a. Kandinsky (1948/1957). In Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, pp. 111–14. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1961b. American Type Painting (1955/1958). In Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon Press, pp. 208–229. [Google Scholar]

- Halasz, P. 1984. Stanley William Hayter: Pollock’s Other Master. Arts Magazine 59: 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1944a. Techniques of Gravure. Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 12: 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1944b. Line and Space of the Imagination. View 4: 126–28, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1945a. The Convention of Line. American Magazine of Art 38: 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1945b. The Language of Kandinsky. American Magazine of Art 38: 176–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1945c. Paul Klee: Apostle of Empathy. American Magazine of Art 39: 127–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, Stanley William. 1965. Orientation, Direction, Cheirality, Velocity and Rhythm. In The Nature and Art of Motion. Edited by Gyorgy Kepes. New York: G. Braziller, pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Karmel, Pepe. 1998. Pollock at Work: The Films and Photographs of Hans Namuth. In Jackson Pollock. Exhibition. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 87–137. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Ellen. 2014. Still Learning from Pollock. In Jackson Pollock’s Mural: The Transitional Moment. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne, Elizabeth L. 2011. Pollock’s Dream of a Biocentric Art: The Challenge of His and Peter Blake’s Ideal Museum. In Biocentrism and Modernism. Edited by O. A. I. Botar and I. Wünsche. Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 227–38. [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne, Elizabeth L. 2012. Jackson Pollock: The Sin of Images. In Meanings of Abstract Art: Between Nature and Theory. Edited by P. Crowther and I. Wünsche. New York: Rutledge, pp. 118–34. [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne, Elizabeth L. 2013. Jackson Pollock- Kunst als Sinnsuche: Abstraktion, All-Over, Action Painting. Wallerstein: Havel Verlag. English Manuscript Online. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/108515122/Jackson_Pollock_Art_as_a_Search_for_Meaning (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Langhorne, Elizabeth L. 2023. Self-Betrayal or Self-Deception? The Case of Jackson Pollock. Arts 12: 54. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076–0752/12/2/54 (accessed on 18 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meier, A. P. 1984. Jackson Pollock’s Prints, 1944–45. Arts Magazine 58: 136–37. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, J. 1978. The Impact of Stanley William Hayter on Post-War American Art. Archives of American Art Journal 18: 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naifeh, Steven, and Gregory White Smith. 1989. Jackson Pollock: An American Saga. New York: Clarkson N. Potter. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Francis V., and Eugene V. Thaw, eds. 1978. Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Drawings, and Other Works. 4 vols, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, A number following CR refers to the number designated to each of Pollock’s works in this Catalogue Raisonné. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, Frank. 1959. Jackson Pollock. New York: George Braziller. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, C. 1978. Printmaking Pioneer: Stanley William Hayter. Art News 77: 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Jeffrey. 1985. To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock. New York: G.P. Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Brenda. 1999. Brice Marden. In Abstraction, Gesture, Écriture: Paintings from the Daros Collection. New York: Scalo, p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Bernice. 1980. Jackson Pollock: Drawing into Painting. New York: Museum of Modern Art and Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, William. 1979. Pollock as Jungian Illustrator: The Limits of Psychological Criticism, Part II. Art in America 67: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solomon, Deborah. 1987. Jackson Pollock: A Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, James Johnson. 1944. New Directions in Gravure. The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 12: 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran, Yvonne, L. Rivers, A. Phenix, and T. Learner. 2014. Jackson Pollock’s Mural: Myth and Substance. In Jackson Pollock’s Mural: The Transitional Moment. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 31–89. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, Christina. 2016. Innovation and Abstraction: Women Artists and Atelier 17. Exhibition Catalogue. East Hampton: Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, Christina. 2019. The Women of Atelier 17: Modernist Printmaking in Midcentury New York. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Reba, and Dave Williams. 1988. The Prints of Jackson Pollock. Print Quarterly 5: 347–73. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Langhorne, E.L. ‘ART’: What Pollock Learned from Hayter. Arts 2026, 15, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010012

Langhorne EL. ‘ART’: What Pollock Learned from Hayter. Arts. 2026; 15(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanghorne, Elizabeth L. 2026. "‘ART’: What Pollock Learned from Hayter" Arts 15, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010012

APA StyleLanghorne, E. L. (2026). ‘ART’: What Pollock Learned from Hayter. Arts, 15(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010012