Music Festivals as Social Venues: Method Triangulation for Approaching the Impact of Self-Organised Rural Cultural Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Arts and cultural activities have payoffs beyond the strictly economic as well—in civic participation, aesthetic and entertainment pleasure, and solving community problems.”

- -

- What influence do they have on the members of the public involved?

- -

- How do they impact the region?

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Social Innovations in Arts and Culture

“Initiatives perceived as new to the local area and different by the stakeholders involved (founders, participants and supporters) and which focus on a specific social problem and are thus designed to add value to society beyond commercial and individual interests and uses: the stakeholders could be members of the public or officials. Social innovations in the field of arts and culture make use of funding for arts and culture a) to facilitate broad social participation by harnessing the integrative function of the arts and culture and b) in pursuit of the inherent value of the arts and culture. Social innovations in the arts and culture cannot be planned in their entirety as chance plays a role in bringing them about. However, structures that can be influenced by policy, such as spaces that can be used free of charge to hold events or actively involved cultural commissioners, make it more likely that social innovations will come about”

2.2. State of Research Regarding Analysis of the Effect of Social Innovations

2.3. State of Research Regarding the Effects of Music Festivals

- Research papers relating to the economics of music festivals

- Research papers relating to the impact of music festivals on the relevant region and the perceptions of local residents

- Research papers focusing on the group of attendees

“the effects of this experience, which is hedonistic more than anything, on the development of people’s personalities as individuals and on the development of a collective consciousness—more so aesthetic than social in nature—[…] should not be underestimated, but should be made the subject of research in the field of cultural studies”

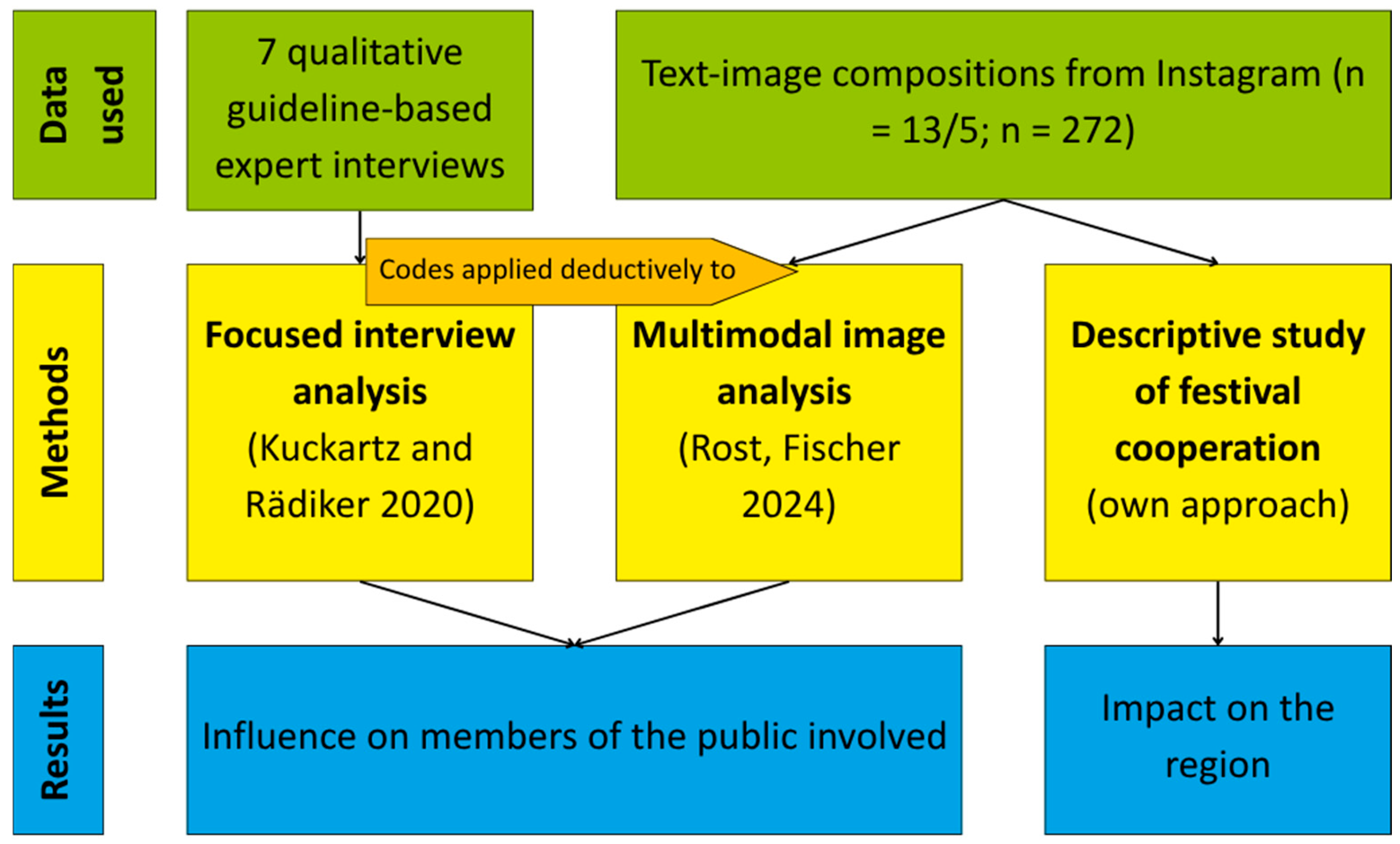

3. Materials and Methods: Triangulation of Methods

4. Results

4.1. Cross-Case Summary of Interview Themes

4.1.1. Community and Solidarity

“So for me [the Field Festival] is a big group of people, including with a wide range of different attitudes […]. And (..) the sense of community lasts all year. […] If I ever have a problem, a question about something, I know that somebody from the [Field Festival] will give me an answer (smiling). Just because the people are such a mixed bunch and at times the support is so enthusiastic too”(Carola, 144 et seq.).

“I spend the majority of the time backstage, [where] there are lots of sofas too and where the [Field Festival] members sit. I sat there watching the music. I almost never went and stood in front of the stage, which is stupid because I basically didn’t get to see bands that I’m a big fan of and who were at [the Field Festival] (laughing)”(Anna, 375 et seq.).

“I had the sense that you very much had to be sworn into the group. And this was in spite of the fact that I was always there […] Lots of people knew and trusted me, but lots had to be reminded of that every year. Who am I actually? Even though people had heard of my dad, who [is known] for being one of the co-founders and who everyone knows”(Anna, 84–90).

4.1.2. Like a Family: Welcoming Meeting Place and Multi-Generational Project

4.1.3. The Music Festival as a Subjective and Political Space of Freedom

- -

- Space for individual development

- -

- Experience in self-efficacy and learning new skills

- -

- Space of freedom to experience and embody an alternative antifascist utopia that is critical of capitalism

4.1.4. The Festival’s Connection to the Region and the Region’s Connection to the Festival

4.2. Findings of the Multimodal Image Analysis as per Rost and Fischer (2024)

4.2.1. Sample: The Field Festival’s Instagram Presence

- -

- What (self-)image on the part of the festival association is conveyed and projected to the public by these images?

- -

- What effects can the festival activities be inferred to have had on the association members?

4.2.2. Systematic Selection of Images

- 4 posts about bands

- 1 post about other events on the programme

- 1 programme overview post

- 4 posts about the festival itself

- 2 posts about events other than the festival itself

- 1 post about ticket sales

4.2.3. Multimodal Image Analysis in Three Steps

4.2.4. Summary of Themes Identified in the Image Analysis

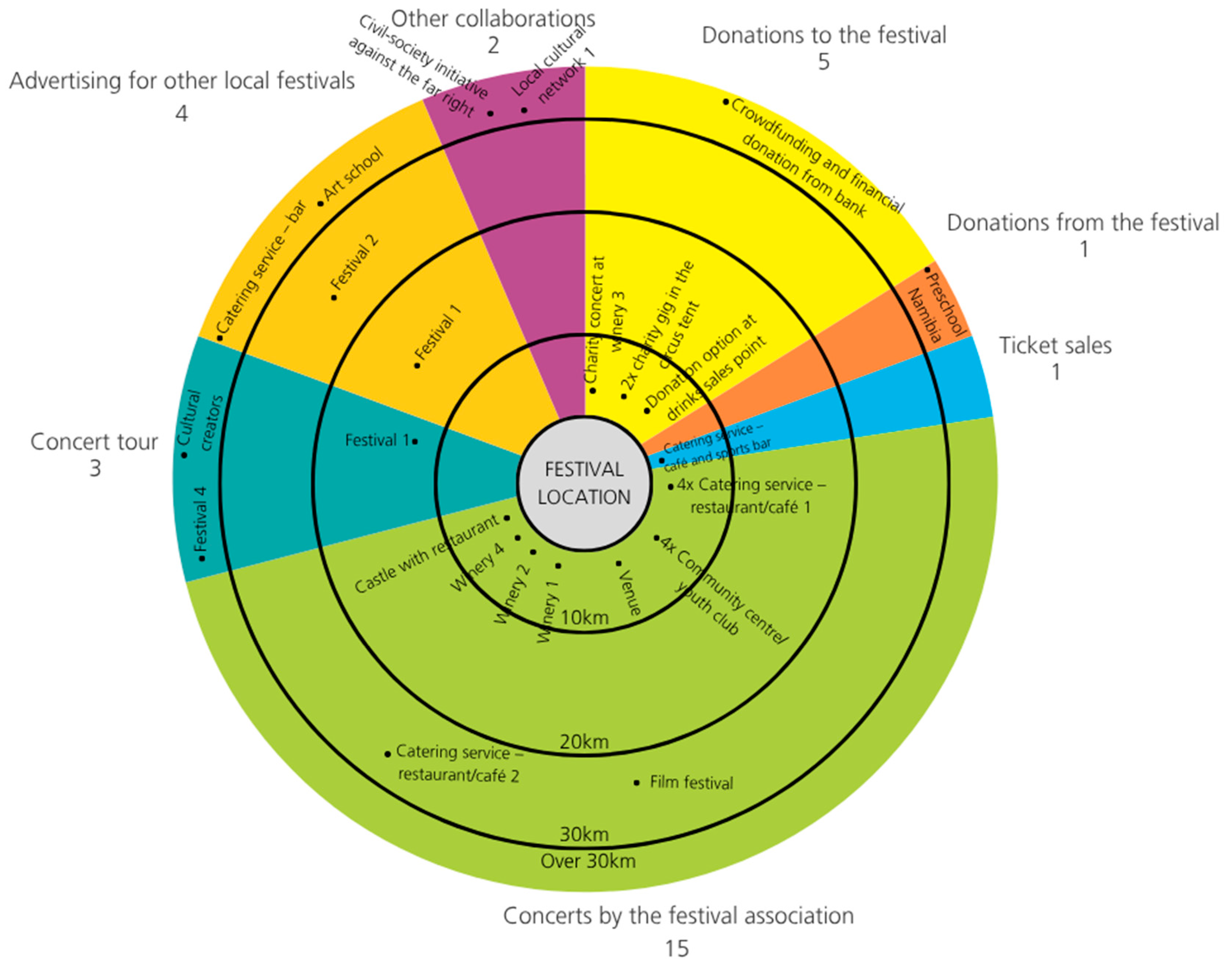

4.3. Descriptive Study of the Festival’s Cooperations Within the Region

5. Aggregation of the Three Analytical Approaches and Discussion of Findings

- -

- What influence do they have on the members of the public involved?

- -

- How Do They Impact the Region?

5.1. Influence on the Members of the Public Involved

“that cohesion, or bonding, within groups of people who are already known to each other is promoted by festival attendance, but bridging between those who were previously unknown to each other was not generally a feature”

“These worlds that revolve around the staging of particular locations, often loaded with histories, are about certain spaces of freedom, experiences and encounters; these extend beyond the acts and music and constitute the values of pop festivals, which are growing ever more important: they facilitate a certain individual and social form of belonging. To achieve this, the pop festivals studied create multifaceted events that create an escape from everyday life and provide the attendees with more than ‘just’ a series of music concerts. They are about short holidays, opportunities to participate in organising the festival, and political and/or subculture-specific programmes (Fusion”)

“Social spaces are [also] public spaces of encounters and communication, of togetherness, of contacts that have been maintained, where communal activities take place and people reinforce their sense of what they stand for. However, social spaces extend far beyond mere meetings and encounters. They are spaces of inclusive participation, cooperation and even of conflict and refuge. Fulfilment of these roles does not necessarily mean that it is possible to set foot in the spaces physically: regional networks and local initiatives where people from civil society, local government and industry come together, get involved and network also constitute social spaces.”

5.2. Impact in the Region

“that local actors develop ties with specific places and, because of these existing connections, tend to participate in region-specific, cultural programmes. Through cultural participation, cultural actors establish new social contacts. In this way, new cooperation can potentially emerge, and thus social networks can be expanded”

“While participating in cultural and arts education, participants find themselves in a space to work on regionally specific issues, which can reinforce a sense of place. Consequently, an iterative process commences, which is why we consider sense of place an important resource for promoting social networks, cooperation, and cultural participation”(Le et al. 2022, ibid).

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Practical Implications

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Implications: What Do the Findings Mean in Practice?

6.2.1. Implications for Rural Cultural Development Plans and Policy

- -

- Volunteer-organised, civil society-led culture can have a long-term positive influence on the sense of regional belonging of cultural stakeholders

- -

- A long-standing cultural offering can be emotionally significant for the residents of a region—even if they do not attend themselves

- -

- Cultural offerings can act as regional markers for a region, with potential positive effects on the attractiveness of a region for the residents

- -

- Volunteer-organised cultural offerings have the potential to exert a positive influence on a region’s cultural landscape, including beyond just the events themselves: by establishing networks with other offerings from the creative and cultural economy and seeking out cooperations with local businesses

6.2.2. Implications for Rural Cultural Stakeholders

- -

- Rural cultural stakeholders who run volunteer-organised cultural offerings should examine their external communications strategy to determine whether it has an exclusive effect or whether it also addresses new attendees—insofar as this is desired

- -

- Cultural stakeholders whose offering has already been in place for a long time should be aware internally of mechanisms that may exclude new/younger members and choose organisational forms that facilitate the inclusion of a greater number of people.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammaturo, Federica, and Suntje Schmidt. 2024. Valuation in Rural Social Innovation Processes—Analysing Micro-Impact of a Collaborative Community in Southern Italy. Societies 14: 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásvanyi, Katalin, and Melinda Jászberényi. 2017. The Role of Rural Cities’ Festivals in the Development of Regions. Deturope—The Central European Journal of Regional Development and Tourism 9: 177–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkert, Karin. 2022. Kultur als rurbane Ressource. Ethnografische Perspektiven auf Steuerungsprozesse from “Kunst und Kultur in ländlichen Räumen”. Zeitschrift für Empirische Kulturwissenschaft 2022: 104–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiciudean, Daniel Ioan, Rezhen Harun, Iulia Cristina Muresan, Felix Horatiu Arion, and Gabriela Ofelia Chiciudean. 2021. Rural Community-Perceived Benefits of a Music Festival. Societies 11: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, Ros. 2007. Regional Festivals: Nourishing Community Resilience: The Nature and Role of Cultural Festivals in Northern Rivers NSW Communities. Doctoral dissertation, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2017. Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations: The Role of Research. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. 2023. National Strategy for Social Innovations and Social Enterprises; Berlin: Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.

- Flick, Uwe. 2011. Triangulation: Eine Einführung, 3rd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, Benoît. 2012. Social Innovation: Utopias of Innovation from c.1830 to the Present. Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation. Working Paper No. 11. Quebec: INRS–Centre Urbanisation Culture Société. [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald-Schukalla, Lorenz, Bastian Schulz, and Carsten Winter. 2019. Der subjektive Wert der Pop-Festivals. In Musik und Stadt. Edited by Lorenz Grünewald-Schukalla, Martin Lücke, Matthias Rauch and Carsten Winter. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 169–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemnezhad, Hashem, Ali Akbar Heidari, and Parisa Mohammed Hoseini. 2013. “Sense of Place” and “Place Attachment”: (A comparative study). International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development 3: 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinčić, Daniela Angelina. 2017. Innovations in Culture and Development. The Culturinno Effect in Public Policy. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Rural Studies. 2023. Special Section: Dynamics of Social Innovations in Rural Communities. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-rural-studies/vol/99/suppl/C#article-18 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Kahle, Ina. 2022. Populärkultur und sozialökologische Transformation. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar]

- Kersten, Jens, Claudia Neu, and Berthold Vogel. 2022. Das Soziale-Orte-Konzept: Zusammenhalt in einer vulnerablen Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Kianicka, Susanne, Matthias Buchecker, Marcel Hunziker, and Ulrike Müller-Böker. 2006. Locals’ and Tourists’ Sense of Place: A Case Study of a Swiss Alpine Village. Mountain Research and Development 26: 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, Babette. 2011. Eventgemeinschaften: Das Fusion Festival und seine Besucher. Wiesbaden: VS Verl. für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Knaps, Falco, and Sylvia Herrmann. 2018. Analyzing Cultural Markers to Characterize Regional Identity for Rural Planning. Rural Landscapes: Society, Environment, History 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Christian. 2019. Kooperation. Available online: https://www.socialnet.de/lexikon/662 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Kriegsmann-Rabe, Milena, and Cathleen Müller. 2025. Soziale Innovationen in Kunst und Kultur als Faktor für kulturelle Teilhabe in ländlichen Räumen. Diskurse und Impulse aus dem Forschungsprojekt SIKUL. Kulturelle Bildung Online. Available online: https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/soziale-innovationen-kunst-kultur-faktor-kulturelle-teilhabe-laendlichen-raeumen-diskurse (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Kuckartz, Udo, and Stefan Rädiker. 2020. Fokussierte Interviewanalyse mit MAXQDA: Schritt für Schritt. Wiesbaden and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Trang, Thi Huyen, and Nina Kolleck. 2022. The Power of Places in Building Cultural and Arts Education Networks and Cooperation in Rural Areas. Social Inclusion 10: 284–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebl, Franz, and Claudia Nicolai. 2009. Posttraditionale Gemeinschaften in ländlichen Gebieten. In Posttraditionale Gemeinschaften: Theoretische und ethnografische Erkundungen. Edited by Ronald Hitzler, Anne Honer and Michaela Pfadenhauer. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Markusen, Ann. 2007. An Arts-Based State Rural Development Policy: Special Issue on Rural Development Policy. Regional Analysis & Policy 37: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenitsch, Katharina, Michaela Neumayr, and Martin Schenk, eds. 2016. Neu! Besser! Billiger! Soziale Innovation als leeres Versprechen? Wien: Mandelbaum Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Pavluković, Vanja, Uglješa Stankov, and Daniela Arsenović. 2020. Social impacts of music festivals: A comparative study of Sziget (Hungary) and Exit (Serbia). Acta Geographica Slovenica 60: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, Jürgen. 2001. Regional identity. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 12917–22. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, Christian, and Marina Fischer. 2024. Eine multimodale Medienanalyse im Projekt KulturLandBilder. Visuelle Geographien—Ansätze, Methoden, Fragen, Leipzig, 28 November 2024. Available online: https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Veranstaltungen/Textdokumente/20241126_VisGeo-Tagungsprogramm_v4.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Teissl, Verena. 2013. Kulturveranstaltung Festival: Formate, Entstehung und Potenziale. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Thünen Institute. 2025. Thünen-Institut für Lebensverhältnisse in ländlichen Räumen und Thünen-Institut für Innovation und Wertschöpfung in ländlichen Räumen. Thünen-Landatlas: Stand 06/2025. Available online: www.landatlas.de (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Verbi Software. 2022. Version Analytics Pro 2022. Berlin: MaxQDA. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Matthias, Susanne Giesecke, Attila Havas, Doris Schartinger, Andreas Albiez, Sophia Horak, Knut Blind, Miriam Bodenheimer, Stephanie Daimer, Liu Shi, and et al. 2024. Social Innovation—(Accompanying) Instrument for Addressing Societal Challenges? In Studien zum deutschen Innovationssystem, 10-2024, ed. Expertenkommission Forschung und Innovation (EFI). Available online: https://www.e-fi.de/fileadmin/Assets/Studien/2024/StuDIS_10_2024.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Wilks, Linda. 2011. Bridging and bonding: Social capital at music festivals. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 3: 281–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willnauer, Franz. 2013. Musikfestivals und Festspiele in Deutschland. Bonn: Deutsches Musikinformationszentrum in der Kulturstadt Bonn. [Google Scholar]

- Woodstock. 1970. Woodstock—3 Days of Peace & Music. Burbank: Warner Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, Filip, Maria Rabadjieva, Judith Terstriep, and Georg Mildenberger. 2023. Wirkung Sozialer Innovationen: Eine theoretische Annäherung. Gelsenkirchen: Forschung Aktuell. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Number of Posts | Proportions of Types of Content, Chronologically by Posts per Year |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2 | 2 posts about the festival |

| 2019 | 4 | 4 posts about the festival |

| 2020 | 6 | 2 posts about the festival 3 posts about events other than the festival itself 1 miscellaneous post |

| 2021 | 9 | 4 posts about the festival 1 post about events other than the festival itself 4 miscellaneous posts |

| 2022 | 46 | Announcements about the programme (32/46 = approx. 69.6%): 27 posts about bands 3 posts relating to other events on the programme 2 programme overview posts 10 posts about the festival (10/46 = approx. 21.7%) 4 posts about events other than the festival itself (4/46 = approx. 8.7%) |

| 2023 | 92 | Announcements about the programme (34/92 = approx. 37%): 30 posts about bands 4 posts relating to other events on the programme 29 posts about the festival (29/92 = approx. 31.5%) 23 posts about events other than the festival itself (23/92 = 25%) 6 posts about ticket sales (6/92 = approx. 6.5%) |

| 2024 | 113 | Announcements about the programme (47/113 = approx. 41.6%): 30 posts about bands 6 posts relating to other events on the programme 11 programme overview posts 48 posts about the festival (48/113 = approx. 42.5%) 5 posts about events other than the festival itself (5/113 = approx. 4.4%) 13 posts about ticket sales (13/113 = approx. 11.5%) |

| Total | 272 | 272 |

| Topic of Post | Absolute Number | Proportion Across All Years as a Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Programme | 113 (87 images of bands; 13 programme overviews; 13 posts with information about other events on the programme such as readings) | 42 per cent |

| Posts about the festival (weather, practical information) | 99 | 36 per cent |

| Events other than the festival itself | 36 | 13 per cent |

| Ticket sales | 19 | 7 per cent |

| Miscellaneous | 5 | 2 per cent |

| Location | Number of Cooperation Partners | Number of Cooperations | Distance from Festival Location as the Crow Flies (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Festival location (Location 1) | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Location 2 | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| Location 3 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Location 4 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Location 5 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| Location 6 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Location 7 | 1 | 1 | 22 |

| Location 8 | 1 | 1 | 27 |

| Location 9 | 1 | 1 | 29 |

| Location 10 | 3 | 2 | 48 |

| Location 11 | 1 | 1 | 50 |

| Location 12 | 1 | 1 | 88 |

| Namibia (Location 13) | 1 | 1 | 7647 |

| 2 unknown locations | 2 | 2 | - |

| Year | Number of Cooperations |

| 2018 | 0 |

| 2019 | 1 |

| 2020 | 4 |

| 2021 | 2 |

| 2022 | 4 |

| 2023 | 14 |

| 2024 | 6 |

| Total | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kriegsmann-Rabe, M.; Müller, C.; Junger, E. Music Festivals as Social Venues: Method Triangulation for Approaching the Impact of Self-Organised Rural Cultural Events. Arts 2025, 14, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060164

Kriegsmann-Rabe M, Müller C, Junger E. Music Festivals as Social Venues: Method Triangulation for Approaching the Impact of Self-Organised Rural Cultural Events. Arts. 2025; 14(6):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060164

Chicago/Turabian StyleKriegsmann-Rabe, Milena, Cathleen Müller, and Ellen Junger. 2025. "Music Festivals as Social Venues: Method Triangulation for Approaching the Impact of Self-Organised Rural Cultural Events" Arts 14, no. 6: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060164

APA StyleKriegsmann-Rabe, M., Müller, C., & Junger, E. (2025). Music Festivals as Social Venues: Method Triangulation for Approaching the Impact of Self-Organised Rural Cultural Events. Arts, 14(6), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060164