Tracing Images, Shaping Narratives: Eight Decades of Rock Art Research in Chile, South America (1944–2024)

Abstract

1. From Productive Margins: Global Trajectories and Situated Challenges in Rock Art Research in Chile

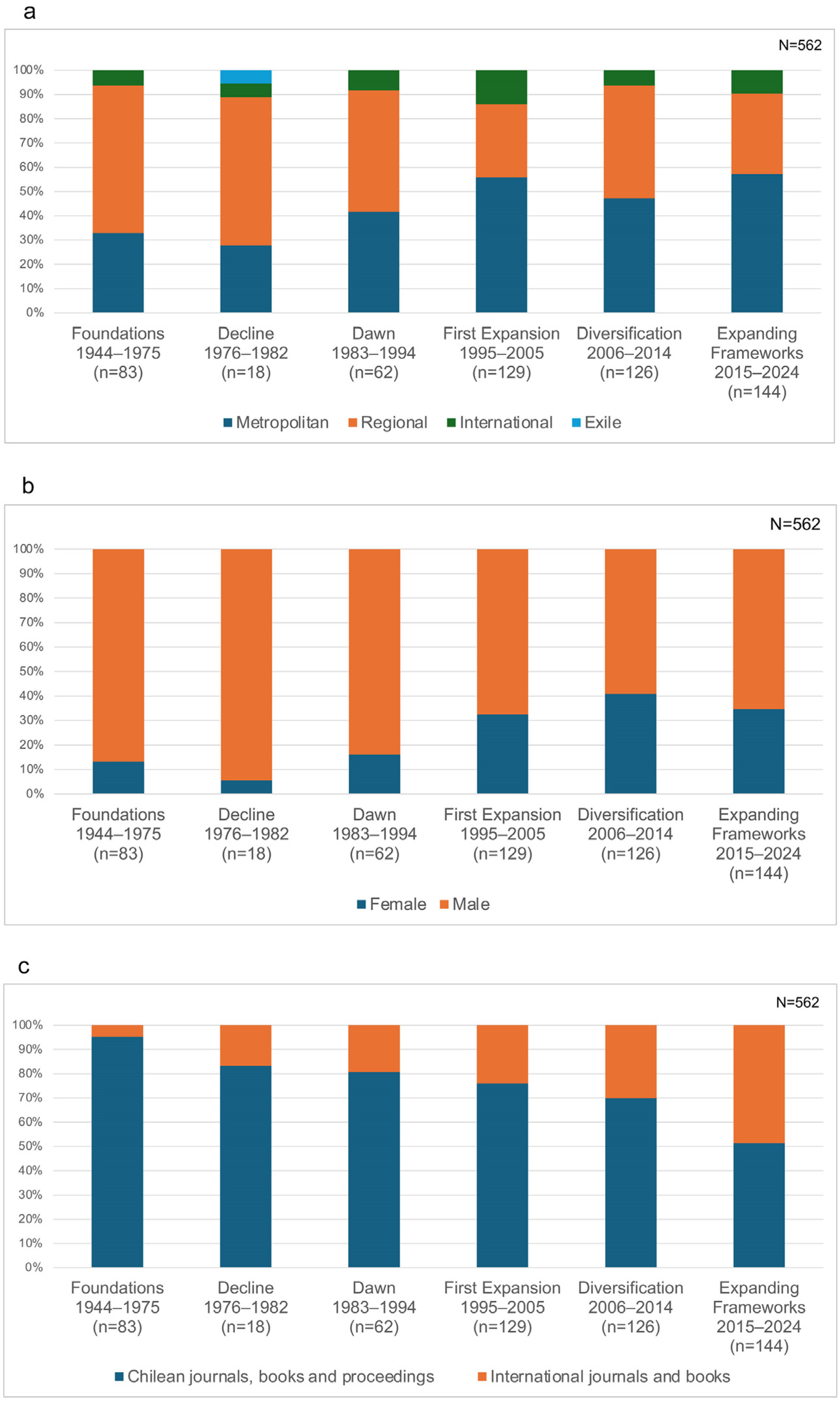

2. Material and Methods: Corpus, Criteria and Regional Divisions for Approaching the Record

3. Results: Eighty Years of Rock Art Research in Chile: Periods, Trends, and Shifts

3.1. Lead-Up to 1944

3.2. Foundations (1944–1975)

3.3. Research Decline (1976–1982)

3.4. Research Dawn (1983–1994)

3.5. First Expansion (1995–2005)

3.6. Diversification (2006–2014)

3.7. Expanding Frameworks (2015–2024): Regional and Thematic Perspectives

3.8. Role Played by FONDECYT and Specific Institutions

4. Discussion: Rethinking Margins: Global Comparisons and Situated Knowledge

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adán, Leonor, Gustavo Gabriel Politis, Marcela Sepúlveda, and Henry Tantaleán. 2017. Arqueología, productividad científica y política en Chile. Revista Chilena de Antropología 35: 218–33. [Google Scholar]

- Aldunate, Carlos, José Berenguer, and Victoria Castro. 1983. Estilos de Arte Rupestre del Alto Loa. Creces IV: 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aldunate, Carlos, José Berenguer, and Victoria Castro, eds. 1985. Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, Gonzalo. 1966. Pictografías y Petroglifos en la provincia de Coquimbo. Notas del Museo Arqueológico de La Serena 9. La Serena: Museo Arqueológico de La Serena. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, Gonzalo. 1985. El arte rupestre en el Norte Chico: Análisis y Proposiciones metodológicas. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 413–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, Gonzalo. 1992. Arte Rupestre en el Valle de El Encanto. La Serena: DIBAM, IM Ovalle, Museo del Limarí, Museo Arqueológico de La Serena. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, Gonzalo, and Mario A. Rivera. 1971. Las manifestaciones rupestres y arqueológicas del Valle El Encanto. Boletín del Museo Arqueológico de La Serena 14: 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Archila, Sonia, Mariano Bonomo, and Christine A. Hastorf. 2021. Introduction: South American Archaeology’s Contributions to World Archaeology. In South American Contributions to World Archaeology. Edited by Mariano Bonomo and Sonia Archila. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio. 2013. Significantes rupestres coloniales del Sitio Toro Muerto (Chile): Canon descriptivo y comentario preliminar. Boletín SIARB (Bolivian Rock Art Research Society) 27: 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio, and José Luis Martínez. 2007. Del Camélido al Caballo: Alteridad, Apropiación y Resignificación en el Arte Rupestre Andino Colonial. In Actas del VI Congreso Chileno de Antropología. Valdivia: Colegio de Antropólogos de Chile, pp. 2067–76. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio, and José Luis Martínez. 2009. Construyendo nuevas imágenes sobre los Otros en el arte rupestre andino colonial. Revista Chilena de Antropología Visual 13: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio, and María Carolina Odone. 2015. Cruz en la piedra: Apropiación selectiva, construcción y circulación de una imagen cristiana en el arte rupestre andino colonial. Estudios Atacameños 51: 137–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio, and María Carolina Odone. 2016. Despliegues visuales en instalaciones religiosas de los andes del sur: Una reflexión desde el arte rupestre colonial y la etnohistoria. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 21: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, Marco Antonio, Bosco González, and José Luis Martínez. 2019. Arte rupestre en los corregimientos coloniales de Tarapacá y Atacama. Problemáticas comparativas iniciales. Estudios Atacameños 61: 73–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello García, Pedro María. 2025. Arqueología del arte rupestre en Colombia. Arqueología y Patrimonio 5: 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Felipe. 2012. Engraved memory: Petroglyphs and collective memory at Los Mellizos, Illapel, Chile. Rock Art Research 29: 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Felipe, Andrés Troncoso, and Francisca Moya-Cañoles. 2018. Rock art assemblages in north-central Chile: Materials and practices through history. In Archaeologies of Rock Art: South American Perspectives. Edited by Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong and George Nash. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 241–63. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Diego. 2002. Las cabezas y los brujos: La leyenda del Chonchón en el arte rupestre del Choapa. Werkén 3: 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Diego. 2004. Dibujando el camino a la costa: Disposición del arte rupestre y uso del valle de Canelillo a través del tiempo. Werkén 5: 139–45. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Diego, and Camila Muñoz. 2015. Arte rupestre en el curso medio del río Ibáñez: Retomando el camino de la interacción de las manifestaciones artísticas al contexto regional. In Actas del XIX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Edited by Rolando Ajata, Doina Munita, Ricardo Moyano, Ivan Leibowicz, Iván Muñoz, Mauricio Uribe, Paola González, Javier Tamblay, Iván Cáceres, Lautaro Núñez and et al. Arica: Universidad de Tarapacá, pp. 507–14. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Diego, and Gloria Cabello. 2004. La Otra Fauna: Los Animales Olvidados del Arte Rupestre del Choapa. Werkén 5: 121–26. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, Diego, Rosario Cordero, and Camila Muñoz. 2016. Reinterpretando paredes: Memoria colectiva, interacción e intercambio de información en el Ibáñez medio, Patagonia central, Chile. In Actas del XIX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Argentina. Edited by Silvina Adris, Florencia Becerra, Sergio Cano, Mario Caria, Cecilia Castellanos, Lorena Cohen, Sara Maria Luisa López Campeny, Mariana Maloberti, Soledad Martínez, Nurit Oliszewski and et al. Tucuman: Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, pp. 2289–95. [Google Scholar]

- Avto Goguitchaichvili, Esteban, Juan Morales, Jaime Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Ana Maria Soler Arechalde, Guillermo Acosta, and José Castelleti. 2016. The use of pictorial remanent magnetization as a dating tool: State of the art and perspectives. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 8: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, G. Paul, and Andrée Rosenfeld, eds. 1991. Rock Art and Prehistory, Oxbow Monograph 10. Oxford: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn, Paul, Natalie Franklin, and Matthias Strecker, eds. 2021. Rock Art Studies: News of the World VI. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn, Paul, Natalie Franklin, Matthias Strecker, and Ekaterina Devlet, eds. 2016. Rock Art Studies: News of the World V. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Ballereau, Dominique, and Hans Niemeyer. 1996. Los sitios rupestres de la cuenca alta del río Illapel (Norte Chico, Chile). Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 28: 319–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín. 2018a. El Médano rock art style: Izcuña paintings and the marine hunter-gatherers of the Atacama Desert. Antiquity 92: 132–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, Benjamín. 2018b. La caza de cetáceos en la costa del desierto de Atacama: Relatos escritos, pinturas rupestres, artefactos y restos óseos. In Baleeiros do Sul II, Antropología e História da Indústria Baleeira nas Costas Sul-Americanas. Edited by Wellington Castellucci and Daniel Quiroz. Salvador de Bahia: Editora da Universidade do Estado da Bahia EDUNEB, pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín. 2018c. Revisita a los petroglifos de Gatico, Tocopilla. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 48: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín. 2018d. Rock art, marine hunting and harpoon devices from the Atacama Desert coast, northern Chile. In Korean Prehistoric Art II. Whale on the Rock II. Edited by Sang-mog Lee. Ulsan: Petroglyph Museum, pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín. 2020. Apuntes sobre los apuntes de Simón Urbina. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 50: 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín, and Francisco Gallardo. 2015. El Médano Rock Art: Large marine prey hunting paintings in the Atacama Desert coast (northern Chile). The Current, Newsletter of the Island and Coastal Archaeology 3: 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín, and Javier Álvarez. 2014–2015. Nadando entre alegorías tribales o la crónica del descubrimiento de las pinturas de Izcuña. Taltalia 7–8: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín, Francisco Gallardo, and Patricio Aguilera. 2015. Representaciones que navegan más allá de sus aguas: Una pintura estilo El Médano a más de 250 km de su sitio homónimo. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 45: 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín, Jorge Gibbons, Daniel Quiroz, and Javier Alvarez. 2019. Aletas, colas, arpones, líneas, balsas y cazadores: Nuevas pinturas para nuevas miradas sobre el estilo de arte rupestre de El Médano (norte de Chile). In Actas del XX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Concepción: Editorial Universidad de Concepción, pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Benjamín, Rafael Labarca, and Elisa Calas. 2018. Relaciones entre tortugas marinas y seres humanos en la costa de Atacama: Dos ejemplos arqueológicos. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 23: 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, Luis Felipe. 1970. Primeras investigaciones sobre el arte rupestre de la Patagonia Chilena. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 1: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, Luis Felipe. 1971. Primeras investigaciones sobre el arte rupestre de la Patagonia Chilena (Segundo Informe). Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 2: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, Luis Felipe. 1982. Origenes de la comunidad primitiva en Patagonia. México: Ediciones Cuicuilco. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 1994. Asentamientos caravaneros y tráfico de larga distancia en el Norte de Chile: El caso de Santa Bárbara. In De Costa a Selva. Producción e Intercambio Entre los Pueblos Agroalfareros de los Andes Centro Sur. Edited by María Ester Albeck. Buenos Aires: Instituto Interdisciplinario de Tilcara, pp. 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 1995a. El arte rupestre de Taira dentro de los problemas de la arqueología atacameña. Chungara 27: 7–44. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 1995b. Impacto del caravaneo prehispánico tardío en Santa Bárbara, Alto Loa. In Actas del XIII Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Antofagasta: Universidad de Antofagasta, pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 1996. Identificación de camélidos en el arte rupestre de Taira: ¿Animales silvestres o domésticos? Chungara 28: 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 1999. El evanescente lenguaje del arte rupestre en los Andes Atacameños. In Arte Rupestre en los Andes de Capricornio. Edited by José Berenguer and Francisco Gallardo. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 9–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2004a. Caravanas, interacción y cambio en el Desierto de Atacama. Santiago: Sirawi Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2004b. Cinco milenios de arte rupestre en los Andes atacameños: Imagenes para lo humano, imágenes para lo divino. Boletin del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 9: 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2005. Five thousand years of rock art in the Atacama Desert: Long-term environmental constraints and symbolic devices. In 23°S Archaeology and Environmental History of the Southern Deserts. Edited by Mike Smith and Paul Hesse. Canberra: National Museum of Australia Press, pp. 231–48. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2009. Caravaneros y guerreros en el arte rupestre de Santa Bárbara, Alto Loa. In Crónicas sobre la Piedra. Arte Rupestre de las Américas. Edited by Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. Arica: Ediciones Universidad de Tarapacá, pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2013. Unkus ajedrezados en el arte rupestre del sur del Tawantinsuyu: ¿La estrecha camiseta de la nueva servidumbre? In Las Tierras Altas del Área Centro Sur Andina entre el 1000 y el 1600 d.C. Edited by María Ester Albeck, Marta Ruiz and María Beatriz Cremonte. Jujuy: CREA FHyCs—UNJu, pp. 311–52. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José. 2018. Representations of whales and other cetaceans in pre-Hispanic rock art of Chile and Peru. In Korean Prehistoric Art II. Whale on the Rock II. Edited by Sang-mog Lee. Ulsan: Ulsan Petroglyph Museum, pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José, and Gloria Cabello. 2005. Late horizon rock art in the Atacama desert? A view from the Inka road. Rock Art Research 22: 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José, and Iván Cáceres. 1989. Correlaciones entre Arte Rupestre y Asentamientos de Pastores en el Alto Loa, norte de Chile: Nota preliminar. Boletín SIARB Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia 3: 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José, and Iván Cáceres. 1995. Datación por C-14 de los comienzos de la ocupación del alero de Taira (Sba-43). Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 21: 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José, and José Luis Martínez. 1986. El río Loa, el Arte Rupestre de Taira y el mito de Yakana. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 1: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, José, Victoria Castro, Carlos Aldunate, Carole Sinclaire, and Luis Cornejo. 1985. Secuencia del arte rupestre en el Alto Loa: Una hipótesis de trabajo. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bittmann, Bente. 1985. Reflection on Geoglyphs of Northern Chile, Latin American Studies. Rickmansworth: H.B.C. Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, José Francisco, Magdalena de la Maza, and María Ángela Peñaloza. 2015. Memoria inscrita: Arte rupestre de contacto, integración y dominación en el centro-sur de Chile. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 20: 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleek, Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel, and Lucy Lloyd. 1911. Specimens of Bushman Folklore. London: George Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Bollaert, William. 1860. Antiquarian, Etnological and Other Researchs in New Granada, Ecuador, Perú and Chile, with Observations of the Pre-Incaria, Incarial, and Other Monuments of Peruvian Nation. London: Trüber & C.º. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Isaiah. 1924. Desert Trails of Atacama. Edited by Gladys Mary Wrigley. American Geographical Society Special Publication. New York: American Geographical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis. 1984. Fundamentos para una metodología aplicada al relevamiento de los geoglifos del norte de Chile. Chungara 12: 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis. 1985. Arte rupestre. In Culturas de Arica. Edited by Calogero M. Santoro and Liliana Ulloa. Santiago de Chile: Departamento de Extensión Cultural del Ministerio de Educación, pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis. 2006. The geoglyphs of the north Chilean desert: An archaeological and artistic perspective. Antiquity 80: 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, Luis, and Carlos Mondaca. 2004. Conocimiento del medio ambiente, rutas de tráfico y representaciones rupestres de la Quebrada de Suca: Una interacción geocultural andina milenaria. Diálogo Andino 24: 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Claudio Castellón. 1997. Un reciente hallazgo de geoglifos en el norte de Chile. El sitio Chug-Chug, Segunda Región. In Congreso Internacional de Arte Rupestre, Cochabamba, Documentos. Edited by Matthias Strecker. La Paz: Sociedad de Investigación de Arte Rupestre de Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Claudio Castellón. 2005. Catastro de geoglifos. Provincia de Tocopilla, Región de Antofagasta, Chile. Tocopilla: Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes, FONDART. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Gustavo Espinosa. 1991. Investigación y rescate de un sitio con arte rupestre. Cerro Colorado, I Región, norte de Chile. Boletín SIARB 5: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Juan Chacama. 1987. Arte rupestre de Ariquilda: Análisis descriptivo de un sitio con geoglifos y su vinculación con la prehistoria regional. Chungara 18: 15–66. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Liliana Ulloa. 2001. Arte en el desierto: Arte rupestre y arte textil. In Pueblos del desierto. Entre el Pacífico y los Andes. Arica: Ediciones Universidad de Tarapacá, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, and Luis Álvarez. 1984. Presentación y valoración de los geoglifos del norte de Chile. Estudios Atacameños 7: 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, Luis, and María Paz Casanova. 2011. Conservación y Restauración de Geoglifos en el Norte de Chile. Arica: Centro de Investigaciones del Hombre en el Desierto/Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, Daniela Valenzuela, and Calogero M. Santoro. 2007. Los geoglifos del valle de Lluta: Una reevaluación desde el estilo (Arica, norte de Chile, períodos Intermedio Tardío e Inka). In Arte Rupestre del Perú y Países Vecinos: Avances en Investigación, Preservación y Educación. Actas del Primer Simposio Nacional de Arte Rupestre. Edited by Rainer Hostnig, Matthias Strecker and Jean Guffroy. Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, pp. 377–90. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, Luis, Lautaro Núñez, and Vivien G. Standen. 2005. Geoglifos y tráfico prehispánico de caravanas de llamas en el Desierto de Atacama (norte de Chile). Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 37: 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, Luis, Persis B. Clarkson, Alberto Díaz, and Carlos Mondaca. 1999. Huasquiña, las chacras y los geoglifos del desierto: Una aproximación al arte rupestre andino. Diálogo Andino 18: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos, Alejandro, and Roberto Lehnert. 1999. Arte rupestre atacameño. Antofagasta: Universidad de Antofagasta. [Google Scholar]

- Byambasuren, Tseren. 2022. Historical overview of Mongolian rock art studies. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 155–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, Gloria. 2003. Rostros que Hablan: Máscaras del valle de Chalinga. In Actas del 4º Congreso Chileno de Antropología. Santiago: LOM Editores, pp. 1363–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, Gloria. 2011. De rostros a espacios compositivos. Una propuesta estilística para el valle de Chalinga, Chile. Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 43: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, Gloria. 2022. Personajes “emplumados” y la incorporación de lo inca en las pinturas rupestres del desierto de Atacama, Chile. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 53: 41–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, Gloria, and Francisco Gallardo. 2014. Iconos claves del Formativo en Tarapacá (Chile): El arte rupestre de Tamentica y su distribución regional. Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 46: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, Gloria, Daniela Valenzuela, and Francisca Moya. 2021. Rock Art in Chile (2015–2019). In Rock Art Studies: News of the World VI. Edited by Paul Bahn, Natalie Franklin and Matthias Strecker. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 340–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, Gloria, Francisco Gallardo, and Carolina Odone. 2013. Las pinturas costeras de Chomache y su contexto económico-social (región de Tarapacá, norte de Chile). Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 18: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, Gloria, Marcela Sepulveda, and Bernardita Brancoli. 2022. Embodiment and fashionable colours in rock paintings of the Atacama Desert, northern Chile. Rock Art Research: The Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA) 39: 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, Gloria, María Belén Vásquez, María Carolina Odone, Francisco Espinoza, Federico González, Benajmín Ballester, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2020. Petroglifos, geoglifos, rutas y otras marcas entre Mamiña, Quipisca e Iquiuca (región de Tarapacá, Chile): Usos y desusos a través del tiempo. Antropologías del Sur 7: 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Roberto, Francisca Moya-Cañoles, and Renata Gutiérrez. 2020. Quien busca, encuentra. Arte rupestre en el sur de Chile: Evaluación, perspectivas y preguntas. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 25: 247–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cané, Ralph E. 1985. La adoración de montañas y la interpretación de algunos geoglifos y petroglifos de quebrada Aroma, Chile y pampa de Nazca, Perú. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 233–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cartajena, Isabel, and Lautaro Núñez. 2006. Purilacti: Arte rupestre y tráfico de caravanas en la cuenca del Salar de Atacama (Norte de Chile). In Tramas en la Piedra. Producción y Usos del Arte Rupestre. Edited by Dánae Fiore and María Mercedes Podestá. Buenos Aires: Asociación Amigos del Instituto Nacional de Antropología, World Archaeological Congress, Sociedad Argentina de Antropología, Altuna Impresores, pp. 221–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cases, Bárbara, and Indira Montt. 2013. Las túnicas rupestres pintadas de la cuenca media y alta del Loa vistas desde Quillagua (norte de Chile). Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 45: 249–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelleti, José. 2007. El arte rupestre en la zona boscosa y lacustre cordillerana del sur de Chile y sus relaciones con regiones vecinas. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 40: 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Castelleti, José. 2019. ¿Hubo realmente caza de ballenas durante la prehistoria de Taltal? In Actas del XX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Concepción: Editorial Universidad de Concepción, pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, Camila, Marcela Sepúlveda, Eugenia M Gayo, Elise Dufour, Nicolas Goepfert, and Daniela Osorio. 2022. Camélidos de contextos cazadores recolectores de la Puna Seca del Desierto de Atacama (extremo norte de Chile): Hacia una comprensión de las interacciones humano-animal. Estudios Atacameños 68: e5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Gastón. 1985. Revisión del arte rupestre Molle. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Victoria, and Francisco Gallardo. 1995–1996. El poder de los gentiles. Arte rupestre en el río Salado. Revista Chilena de Antropología 13: 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Victoria, Francisco Gallardo, and Pablo Miranda. 1989. Un estudio de arte rupestre en la subregión del río Salado: Notas de una investigación en curso. Boletín SIARB Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia 3: 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, Iván, and José Berenguer. 1993. Problemas con la distribución y cronología del arte rupestre de Taira. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 16: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, Iván, and José Berenguer. 1996a. Arte Rupestre mobiliar de estilo Kalina en el Alto Loa. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 23: 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, Iván, and José Berenguer. 1996b. El caserío de Santa Bárbara 41, su relación con la W’aka de Taira. Alto Loa. Chungara 28: 381–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda, Pablo, Sixto Fernández, and Jaime Estay. 1985. Prospección de geoglifos de la Provincia de Iquique, Primera Región Tarapacá, norte de Chile: Informe preliminar. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 311–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrillo-Cuenca, Enrique, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2015. An assessment of methods for the digital enhancement of rock paintings: The rock art from the precordillera of Arica (Chile) as a case study. Journal of Archaeological Science 55: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo-Cuenca, Enrique, Marcela Sepúlveda, and Zaray Guerrero-Bueno. 2021. Independent component analysis (ICA): A statistical approach to the analysis of superimposed rock paintings. Journal of Archaeological Science 125: 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo-Cuenca, Enrique, Marcela Sepúlveda, Gloria Cabello, and Fernando Bastías. 2024. Color-based discrimination of color hues in rock paintings through Gaussian mixture models: A case study from Chomache site (Chile). Heritage Science 12: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellino, Miguel. 1985. Evaluación del arte rupestre en la III Región—Atacama. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 355–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellino, Miguel, and Nelson Silis. 2001. El arte rupestre de los sitios Finca de Chañaral y Quebrada de las Pintiras, Región de Atacama. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Luis Cornejo, Francisco Gallardo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 134–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan. 2004. Hombres, Pájaros y Hombres-Pájaros. Análisis iconográfico de figuras humanas y aves grabadas sobre roca. Quebrada de Aroma, sitio Ariquilda 1, extremo norte de Chile. In Simbolismo y Ritual en los Andes Septentrionales. Edited by Mercedes Guinea. Quito: Editorial Abya-Yala y Editorial Complutense, pp. 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, and Gustavo Espinosa. 2000. La ruta de Tarapacá. Análisis de un mito y una imagen rupestre en el norte de Chile. In Actas del XIV Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Copiapó: Museo Regional de Atacama, pp. 769–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, and Ivan Muñoz. 1991. La cueva de La Capilla: Manifestaciones de arte y símbolos de los pescadores arcaicos de Arica. In Actas del XI Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Santiago: Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, and Luis Briones. 1993. Arte andino, reflejo de una cultura. In El Altiplano. Ciencia y Conciencia en los Andes. Actas del II Simposio Internacional de Estudios Altiplánicos 19 al 21 de Octubre de 1993, Arica. Santiago: Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, and Luis Briones. 1997. Arte rupestre tarapaqueño, norte de Chile. Boletín SIARB Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia 10: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, and Luis Briones. 2003. El juego de la falcónida. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 35/36: 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chacama, Juan, Luis Briones, and Calogero M. Santoro. 1992. Arte rupestre post-hispano: Una aproximación al problema en el norte de Chile. In Arte Rupestre Colonial y Republicano de Bolivia y Países Vecinos. La Paz: Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia, pp. 168–71. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2022. History debunked: Endeavours in rewriting the San past from the Indigenous rock art archive. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chippindale, Christopher. 2001. Studying ancient pictures as pictures. In Handbook of Rock Art Research. Edited by David S. Whitley. California: Altamira Press, pp. 247–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chippindale, Christopher, and Paul S. C. Taçon, eds. 1998. The Archaeology of Rock Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B. 1996. Técnicas en la determinación de las edades cronológicas de los geoglifos. Chungara 28: 419–60. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B. 1998. Archaeological Imaginings. Contextualization of Images. In Reader in Archaeological Theory. Post-Processual and Cognitive Approaches. Edited by David S. Withley. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 119–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B. 1999a. Considérations historiques et contextualisation de la recherche sur les géoglyphes au Chili. Anthropologie et Sociétés 23: 125–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Persis B. 1999b. Designs on the Desert. Huge Images created across the rocky Landscape of Chile. Discovering Archaeology 1: 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B. 2019. Las aves de Guatacondo: Los mitos, la historia y la realidad. In Actas del XX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Concepción: Editorial Universidad de Concepción, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B., and Luis Briones. 2001. Geoglifos, senderos y etnoarqueología de caravanas en el desierto chileno. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 8: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B., and Luis Briones. 2014. Astronomía cultural de los geoglifos andinos: Un ensayo sobre los antiguos tarapaqueños, norte de Chile. Diálogo Andino 44: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Persis B., and Luis Briones. 2015. Representaciones ideológicas y artísticas de sol en el contexto de las antiguas culturas tarapaqueñas. In Actas del XIX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Arica: Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, Universidad de Tarapacá. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B., Gerald Johnson, William Johnson, Luis Briones, and Evan Johnson. 1999a. Photographie aérienne à coüt réduit et à haute renabilité en archéologie. International Newsletter on Rock Art 24: 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B., Luis Briones, Gerald Johnson, and Evan Johnson. 1999b. La percepción de los geoglifos por visión aérea. Boletín SIARB, Sociedad de Investigación del arte Rupestre de Bolivia 13: 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Persis B., Mario A. Rivera, and Ronald I. Dorn. 2001. Manifestaciones culturales en la región de Guatacondo: Los primeros fechados numéricos de geoglifos. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Luis Cornejo, Francisco Gallardo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 109–14. [Google Scholar]

- Conkey, Margaret W. 2012. Foreword: Redefining the mainstream with rock art. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. xxix–xxxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Conkey, Margaret W. 2019. Interpretative Frameworks and the Study of the Rock Arts. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by Bruno David and Ian J. McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, Rosario, Camila Muñoz, and Diego Artigas. 2019. Reinterpretando paredes: Interacción e intercambio de información en el Ibáñez medio, Patagonia central, Chile. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 24: 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, Luis E. 1997. Buscadores del pasado: Una breve historia de la arqueología chilena. In Chile antes de Chile. Edited by José Berenguer. Santiago de Chile: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, Luis E. 2017. Productividad e impacto de la arqueología chilena: Una perspectiva cienciométrica. Revista Chilena de Antropologia 35: 164–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, Luis E. 2020. Comentario a Urbina: Del ordenado mundo taxonómicos a las calles de Blade Runner. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 50: 93–93. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, Amalia. 2001. La estrategia de lo site-especific: El arte rupestre como modelo. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Luis Cornejo, Francisco Gallardo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 341–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dauelsberg, Percy. 1959. Contribución a la arqueología del valle de Azapa. Boletín del Museo Regional de Arica 3: 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dauelsberg, Percy, Luis Briones, Sergio Chacón, Erie Vásquez, and Luis Álvarez. 1975. Los grandes geoglifos del valle del Lluta. Revista Universidad de Chile Sede Arica 3: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- David, Bruno, and Ian J. McNiven. 2018. Introduction: Towards an Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by Bruno David and Ian J. McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- David, Bruno, and Ian J. McNiven, eds. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Iain, and April Nowell, eds. 2021. Making Scenes. Global Perspectives on Scenes in Rock Art. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dettwiler, Axel. 1986. Análisis del arte rupestre, entre la miopía funcionalista y el imperialismo de la semiótica. Chungara 16–17: 451–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dillehay, Tom D. 2021. A Singular Perspective on the Influence of Andean Theory in Archaeology. In South American Contributions to World Archaeology. Edited by Mariano Bonomo and Sonia Archila. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 319–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dillehay, Tom D., and Carlos Ocampo. 2016. El paso” Vuriloche” Chile-Argentina: Ruta de los Jesuitas. Puerto Montt: Universidad Austral de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Dinerstein, Eric, David Olson, Anup Joshi, Carly Vynne, Neil D. Burgess, Eric Wikramanayake, Nathan Hahn, Suzanne Palminteri, Prashant Hedao, Reed Noss, and et al. 2017. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 67: 534–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita. 2022. History of the study of schematic rock art in Spain. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo-Sanz, Inés. 2012. A Theoretical Approach to Style in Levantine Rock Art. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 306–21. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo-Sanz, Inés, and Marina Gallinaro. 2021. Impacts of scientific approaches on rock art research: Global perspectives. Quaternary International 572: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudognon, Carole, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2015. Scenes, camelids and anthropomorphics style variations in the north Chile’s rock art during Archaic and Formative transition. In Proceedings of XIX International Rock Art Conference IFRAO 2015. Edited by Hipólito Collado and José Julio García. Cáceres: Arkeos, pp. 217–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dudognon, Carole, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2018. Rock art of the upper Lluta valley, northernmost of Chile (South Central Andes): A visual approach to socio-economic changes between Archaic and Formative periods (6000–1500 years BP). Quaternary International 491: 136–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, Sebastian. 1988. La Tierra de Hotu Matu’a. Historia y Etnología de la Isla de Pascua. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, Gustavo. 1996. Lari y Jamp’atu. Ritual de lluvia y simbolismo andino en una escena de arte rupestre de Ariquilda 1. Norte de Chile. Chungara 28: 133–58. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, Luis. 2017. Hualqui: El misterio de los petroglifos del Cerro de la Costilla, un patrimonio en peligro. Concepción: Ícaro. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, Dánae, and María Isabel Hernández Llosas. 2007. Miradas rupestres. Tendencias en la investigación del arte parietal en Argentina. Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología XXXII: 217–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fontecilla, Arturo. 1936. Contribución al estudio de los petroglifos cordilleranos. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural XL: 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Natalie R., Paul Bahn, and Matthias Strecker, eds. 2008. Rock Art Studies: News of the World III. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gajardo-Tobar, Roberto. 1938. Petroglifos de Elqui. Revista Chilena de Historia y Geografía LXXXIV: 264–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 1992. Conceptos básicos de arte rupestre. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 15: 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 1996. Acerca de la lógica en la interpretación del arte rupestre. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 23: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 1998. Arte, arqueología social y marxismo: Comentarios y perspectivas (Parte I). Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 26: 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 1999. Arte, arqueología social y marxismo: Comentarios y perspectivas (Parte II). Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 27: 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 2001. Arte rupestre y emplazamiento durante el Formativo Temprano en la cuenca del río Salado (desierto de Atacama, norte de Chile). Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 8: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 2004. El Arte Rupestre como Ideología: Un Ensayo Acerca de Pinturas y Grabados en la Localidad del Río Salado (Desierto de Atacama, Norte de Chile). Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 36: 427–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 2005. Apuntes sobre el movimiento y su expresión en el arte rupestre del norte de Chile. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 37: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco. 2009. Sobre la composición y la disposición en el arte rupestre de Chile: Consideraciones metodológicas e interpretativas. Magallania 37: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Flora Vilches. 1995. Notas acerca de los estilos de arte rupestre en el pukara de Turi (Norte de Chile). Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 20: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Flora Vilches. 1996. An original rock art style in the Atacama desert (Northern Chile). International Newsletter on Rock Art 15: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Gloria Cabello. 2015. Emblems, Leadership, Social Interaction and Early Social Complexity: The Ancient Formative Period (1500 bc–ad 100) in the Desert of Northern Chile. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25: 615–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Hugo D. Yacobaccio. 2005. Wild or Domesticated? Camelids in Early Formative Rock Art of the Atacama Desert (Northern Chile). Latin American Antiquity 16: 115–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Hugo D. Yacobaccio. 2007. ¿Silvestres o domesticados? Camélidos en el arte rupestre del formativo temprano en el desierto de Atacama (norte de Chile). Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 12: 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, and Victoria Castro. 1992. El Poder de las Imágenes: Etnografía en el Río Salado (Desierto de Atacama). Creces 13: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Carole Sinclaire, and Claudia Silva. 1999a. Arte rupestre, emplazamiento y paisaje en la cordillera del Desierto de Atacama. In Arte Rupestre en los Andes de Capricornio. Edited by José Berenguer and Francisco Gallardo. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 57–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Flora Vilches, Luis Cornejo, and Charles Rees. 1996. Sobre un estilo de arte rupestre en la cuenca del Río Salado (Norte de Chile): Un estudio preliminar. Chungara 28: 353–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Gloria Cabello, and Gonzalo Pimentel. 2018. Signs in the desert: Geoglyphs as cultural system and ideology (northern Chile). In Archaeologies of Rock Art: South American Perspectives. Edited by Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong and George Nash. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 130–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Gloria Cabello, Marcela Sepúlveda, Benajmín Ballester, Dánae Fiore, and Alfredo Prieto. 2023. Yendegaia Rockshelter, the First Rock Art Site on Tierra del Fuego Island and Social Interaction in Southern Patagonia (South America). Latin American Antiquity 34: 532–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Indira Montt, Marcela Sepúlveda, and Gonzalo Pimentel. 2006. Nuevas perspectivas en el estudio de arte rupestre en Chile. Boletín SIARB (Bolivian Rock Art Research Society) 20: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Victoria Castro, and Pablo Miranda. 1990. Jinetes Sagrados en el Desierto de Atacama: Un estudio del arte rupestre andino. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 4: 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, Francisco, Victoria Castro, and Pablo Miranda. 1999b. Riders on the Storm: Rock Art in the Atacama Desert (Northern Chile). World Archaeology 31: 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Christian, and Francisco Mena. 2016. ¿La frontera del oeste?: Prospecciones arqueológicas en el bosque montano del extremo occidental del valle medio del río Ibáñez (Andes patagónicos, Chile). Intersecciones en Antropología 17: 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gili, María Laura. 2001. La problemática del arte rupestre con perspectiva histórico-metodológica. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Luis Cornejo, Francisco Gallardo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 170–79. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhahn, Joakim. 2022. To alleviate the night-black darkness that conceals our most ancient times:’ Carl Georg Brunius’ trailblazing rock art thesis from 1818. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhahn, Joakim, Jamie Hampson, and Sam Challis. 2022. Why the history of rock art research matters. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- González, Bosco. 2014. Discursos en el paisaje andino colonial: Reflexiones en torno a la distribución de sitios con arte rupestre colonial en Tarapacá. Diálogo Andino 44: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Josefina. 2002. Etología de camélidos y arte rupestre de la Subregión río Salado (norte de Chile, II Región). Estudios Atacameños 23: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Paola. 2005. Códigos visuales de las pinturas rupestres Cueva Blanca: Formas, simetría y contexto. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 10: 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- González, Paola. 2011. Universo representacional del arte rupestre del sitio Los Mellizos (Provincia del Choapa): Convenciones visuales y relaciones culturales. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 16: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Paola. 2020. Shipibo Conibo and Chilean Diaguita Visual Art: Cognitive Technologies, Shamanism and Long-Distance Cultural Linkages. In Ecosystem and Biodiversity of Amazonia. Edited by Heimo Juhani Mikkola. London: IntechOpen, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ramírez, Andrea Andrea. 2020. Otras compañeras que no continuaron… Más que olvido, el ojo caníbal. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 50: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, Alejandra. 2004. Plan de manejo para la puesta en valor y preservación del arte rupestre frente al turismo: El caso de la Comuna de Canela (Provincia del Choapa, IV Región, Chile). Werkén 5: 147–52. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, Zaray, and Marcela Sepúlveda. 2018. Arte rupestre pintado en el alero Pampa el Muerto 11 de la precordillera de Arica: Propuesta estilística y secuencia cronológica. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 23: 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, Zaray, Marcela Sepúlveda, and Enrique Cerrillo-Cuenca. 2015. Aproximación mediante técnicas digitales de documentación al estudio del arte rupestre pictórico en el sector Pampa El Muerto (extremo norte de Chile). In Proceedings of XIX International Rock Art Conference IFRAO 2015. Edited by Hipólito Collado and José Julio García. Cáceres: Arkeos, pp. 523–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gurruchaga, Andone, and Michelle Salgado. 2017. Publicación científica bajo criterios hegemónicos: Explorando la realidad arqueológica chilena. Revista Chilena de Antropología 35: 148–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2022. The history of rock art research in west Texas, North America, and beyond. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie, Joakim Goldhahn, and Sam Challis, eds. 2022. Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Hays-Gilpin, Kelley, and Dennis Gilpin. 2022. Reclaiming connections: Ethnography, archaeology, and images on stone in the southwestern United States. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hornkohl, Herbert. 1951. Los petroglifos de la finca de Chañaral, Provincia de Atacama, Chile. Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural XXV: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornkohl, Herbert. 1954. Los petroglifos de Gático en la provincia de Antofagasta, Chile. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural LIV: 152–54. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, Helena. 1996. Taira: Definición estilística e implicancias iconográficas de su arte rupestre. Chungara 28: 395–417. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, Helena. 1999. Ubicación cronológica del estilo Vizcachuno en el arte rupestre del Loa Superior, II Región. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 27: 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, Helena. 2000. El arte rupestre de Taira: Definición estilística e iconográfica. Revista de Teoría del Arte 2: 83–160. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, Helena. 2001. Sectorización de estilos en el arte rupestre del Loa, norte de Chile. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Francisco Gallardo, Luis Cornejo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, Helena, and José Berenguer. 1995. Un icono formativo en el arte rupestre del Alto Loa. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 20: 23. [Google Scholar]

- Igualt, Fernando. 1964. Investigaciones de Petroglifos en Chincolco. In Arqueología de Chile Central y Areas Vecinas. Actas del Tercer Congreso Internacional de Arqueología Chilena, Viña del Mar. Santiago: Sociedad de Arqueología e Historia Dr. Francisco Fonck, pp. 125–29. [Google Scholar]

- Igualt, Fernando. 1969. Investigación de petroglifos en Chincolco N° 2. In Actas del IV Congreso Nacional de Arqueología. Concepción: Universidad de Concepción, pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Igualt, Fernando. 1970. Investigación de petroglifos en Jahuel. Anales del Museo de Historia Natural de Valparaíso 3: 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1947. Los petroglifos del valle del río Hurtado. Publicaciones de la Sociedad Arqueológica de La Serena 3: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1953. Revisión de los petroglifos del valle del río Hurtado. Revista Universitaria, Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales XXXVIII: 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1957. Revisión de los petroglifos del valle del río Hurtado IV. Sector hacienda El Bosque. Revista Universitaria, Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales XLII: 113–17. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1963. VI Revisión de los petroglifos del valle del río Hurtado. Distrito de Hurtado y siguientes. Revista Universitaria, Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales XLVII–XLV: 117–25. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1968. Dispersión de las figuras rupestres en el norte de Chile (petroglifos, pictografías y geoglifos). In Actas y Memorias del XXXVII Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, Vol. II. México: Universidad Autónoma de México, pp. 391–418. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1973. Geoglifos, pictografias y petroglifos de Chile. Boletín del Museo Arqueológico de La Serena 15: 133–59. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Jorge. 1976. Arte rupestre en la quebradada de las Pinturas (III Región). In Homenaje al Dr. Gustavo Le Paige, S.J. Antofagasta: Universidad del Norte, pp. 115–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Donald G., Diego Artigas, and Gloria Cabello. 2001. Nuevas manifestaciones de petroglifos en la precodillera del Choapa: Técnicas, motivos y significados. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 32: 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Donald G., Diego Artigas, and Gloria Cabello. 2002. Trazos del Choapa. Arte Rupestre en la Cuenca del río Choapa. Una Perspectiva Macroespacial. Santiago: Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffuel, Félix. 1930. Las piedras pintadas del Cajón de los Cirpreses (Hoya del Cachapoal). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural XXXIV: 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- Labarca, Rafael, Elisa Calás, Javiera Letelier, Brent Alloway, and Karen Holmberg. 2021. Arqueología en el Morro Vilcún (Comuna de Chaitén, Región de Los Lagos, Chile): Síntesis y Perspectivas. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología special issue: 499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Labarca, Rafael, Francisco Mena, Alfredo Prieto, Thierry Dupradou, and Eduardo Silva. 2016. Investigaciones arqueológicas en torno a los primeros registros de arte rupestre en Morro Vilcún. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 21: 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latcham, Ricardo E. 1927. Breve bibliografía de los petroglifos sudamericanos. Vol. Tomo 1, Revista de Bibliografía Chilena y Extranjera. Santiago: Editorial Nascimento. [Google Scholar]

- Latcham, Ricardo E. 1938. Arqueología de la Región Atacameña. Santiago: Prensas de la Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Laue, Ghilraen. 2022. A history of research into regional difference in southern African rock paintings. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 116–25. [Google Scholar]

- Le Paige, Gustavo. 1958. Antiguas Culturas Atacameñas de la cordillera Chilena. Anales de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso 4–5: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma, Félix Alejandro. 2022. On the history of rock art research in Mexico and Central America. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 2001. Brainstorming images: Neuropsychology and rock art research. In Handbook of Rock Art Research. Edited by David S. Whitley. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press, pp. 332–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 2006. The Evolution of Theory, Method and Technique in Southern African Rock Art Research. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 13: 343–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 2010. Conceiving God: The Cognitive Origin and Evolution of Religion. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, Ingeborg. 1969. Conchi Viejo: Una capilla y ocho casas. In Actas del V Congreso Nacional de Arqueología. La Serena: Museo Arqueológico de La Serena. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, Ingeborg, Eliana Pineda, and Lautaro Núñez. 1960. Algunos aspectos de la vida material y espiritual de los Araucanos del Lago Brudi. Finis Terrae 28: 58–89. [Google Scholar]

- Llamazares, Ana María. 1993. Arte rupestre de las quebradas de Guatacondo y Quisma, norte de Chile. Boletín SIARB Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia 7: 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Looser, Gualterio. 1929. Algunos petroglifos de la provincia de Coquimbo. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 33: 142–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lorblanchet, Michel, and Paul G. Bahn, eds. 1993. Rock Art Studies: The Post-Stylistic Era or Where Do We Go from Here?, Papers Presented in Symposium A of the 2nd AURA Congress, Cairns 1992. Oxford: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Gavin. 2012. Understanding the Archaeological Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Gavin. 2017. The paradigm concept in archaeology. World Archaeology 49: 260–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Gavin. 2018. Writing the Past: Knowledge and Literary Production in Archaeology, 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, Jacqueline. 1969. Petroglifos del cerro Los Ratones, Cajón del Maipo, Prov. de Santiago. In Actas del V Congreso Nacional de Arqueología. La Serena: Museo Arqueológico de La Serena, pp. 277–94. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, José Luis. 2006. ¿Arte rupestre o sistemas de comunicación visual? In Actas del 5º Congreso Chileno de Antropología: Antropología en Chile. Balance y Perspectivas. Santiago: Colegio de Antropólogos, pp. 339–47. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, José Luis. 2009. Registros andinos al margen de la escritura: El arte rupestre colonial. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 14: 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, José Luis. 2022. Rock Art and Memories in the Southern Andes: “This Was Left to Us by the Incas”. In Rock Art and Memory in the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge. Edited by Leslie F. Zubieta. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 221–43. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, José Luis, and Marco Antonio Arenas. 2009. Problematizaciones en torno al arte rupestre colonial en las áreas centro sur y meridional andina. In Crónicas sobre la Piedra. Arte Rupestre de las Américas. Edited by Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. Arica: Universidad de Tarapacá, pp. 129–40. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, José Luis, and Marco Antonio Arenas. 2011. Los petroglifos del sitio Tarapacá-47 y su contribución a la comprensión del arte rupestre colonial andino. In Temporalidad, interacción y dinamismo cultural. La búsqueda del hombre. Homenaje al profesor Dr. Lautaro Núñez Atencio. Edited by Andrés Hubert, José Antonio Gonzalez and Mario Pereira. Antofagasta: Universidad Católica del Norte Ediciones Universitarias, pp. 152–62. [Google Scholar]

- Massone, Mauricio. 1982. Nuevas investigaciones sobre el arte rupestre de Patagonia Meridional Chilena. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 13: 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, and Peter Veth, eds. 2012a. A Companion to Rock Art. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, and Peter Veth. 2012b. Research Issues and New Directions: One Decade into the New Millennium. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, Francisco. 1983. Excavaciones arqueológicas en Cueva Las Guanacas (RI–16) XIª Región de Aisén. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia 14: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, Francisco, Camila Muñoz, Diego Artigas, Rosario Cordero, and Nibaldo Calderón. 2018. Primer registro de grabados en Aisén (Patagonia Central, Chile). Boletín de la Sociedad de Investigación del Arte rupestre de Bolivia 32: 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, César, Amalia Nuevo-Delaunay, Paulo Moreno-Meynard, Francisca Moya-Cañoles, Rosario Cordero-Fernández, Camila Muñoz, Diego Artigas, Macarena Barrera, María Luisa Gómez, and Javiera Gajardo-Araos. 2023. El arte rupestre de la región de Aisén (Chile): Una sistematización de la información espacial y temporal. Magallania 51: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, César, Omar Reyes, Amalia Nuevo Delaunay, Héctor Velásquez, Valentina Trejo, Natalie Hormazábal, Marcelo Solari, and Charles R Stern. 2016. Las Quemas Rockshelter: Understanding Human Occupations of Andean Forests of Central Patagonia (Aisén, Chile), Southern South America. Latin American Antiquity 27: 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, César A. 2008. Cadenas operativas en la manufactura de arte rupestre: Un estudio de caso en El Mauro, valle cordillerano del Norte Semiárido de Chile. Intersecciones en Antropología 9: 145–55. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, César A., and Omar Reyes. 2006. Nuevos datos de la ocupación humana en la transición bosque estepa en Patagonia: Alero Las Quemas (comuna de Lago Verde, XI Región de Aisén). Magallania 34: 161–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, Pablo, and Miguel Saavedra. 1997. Arte rupestre en el río Colorado, Cajón del Maipo. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 24: 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, Ignacio, César Borie, Andrés Troncoso, Ximena Power, Sonia Parra, Patricio Galarce, and Mariela Pino. 2016. Navegantes del desierto. Un nuevo sitio con arte rupestre estilo El Médano en la depresión intermedia de Taltal. Taltalia 9: 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Montané, Julio. 1965–1966. Pictografías y petroglifos de Villucura (Provincia de Bío-Bío, Chile). Revista Universitaria, Anales de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Naturales 50: 377–81. [Google Scholar]

- Montt, Indira. 2002. Faldellines del Período Formativo en el Norte Grande: Un ensayo acerca de la historia de su construcción visual. Estudios Atacameños 23: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montt, Indira. 2004. Elementos de Atuendo e Imagen Rupestre en la Subregión de Río Salado, Norte Grande de Chile. Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 36: 651–61. [Google Scholar]

- Montt, Indira. 2010. Las representaciones de Ghatchi-02VI90 en el contexto rupestre local y regional (cuenca del Río Vilama, San Pedro de Atacama). In Actas del XVII Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena (2006). Valdivia: Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, Universidad Austral de Chile, pp. 133–44. [Google Scholar]

- Montt, Indira, and Gonzalo Pimentel. 2009. Grabados antropomorfos tardíos. El caso de las personificaciones de hachas en San Pedro de Atacama. In Crónicas sobre la Piedra. Arte Rupestre de las Américas. Edited by Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. Arica: Ediciones Universidad de Tarapacá. [Google Scholar]

- Moragas, Cora. 1993. Antecedentes sobre un pukara y estructuras de cumbre asociadas a un campo de geoglifos en la Quebrada de Tarapacá, área de Mocha, I Región. In Actas del XII Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Temuco: Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, Museo Regional de la Araucanía, pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moragas, Cora. 1996. Manifestaciones rupestres en el tramo bajo de la quebrada de Tambillo, Provincia de Iquique, I Región. Chungara 28: 241–52. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, AlejAndro, Clemente Mella, and Pablo González. 2017. Arte rupestre de la región del Maule: Huellas de un pasado desconocido, Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes. Talca: Impresora Gutenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Moro-Abadía, Oscar, Margaret W. Conkey, and Josephine McDonald. 2024a. Deep-Time Images and the Challenges of Globalization. In Deep-Time Images in the Age of Globalization: Rock Art in the 21st Century. Edited by Oscar Moro-Abadía, Margaret W. Conkey and Josephine McDonald. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moro-Abadía, Oscar, Margaret W. Conkey, and Josephine McDonald, eds. 2024b. Deep-Time Images in the Age of Globalization: Rock Art in the 21st Century. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Morwood, Mike J., and Claire E. Smith. 1994. Rock art research in Australia 1974–94. Australian Archaeology 39: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostny, Grete. 1961. Ideas religiosas de los atacameños. In Encuentro Arqueológico Internacional de Arica y Cuadro Cronológico del Área Andina Meridional. Arica: Universidad de Chile sede Arica/Museo Regional de Arica. [Google Scholar]

- Mostny, Grete. 1985. Función y significado del arte rupestre en Chile. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. [Google Scholar]

- Mostny, Grete, and Hans Niemeyer. 1983. Arte Rupestre Chileno. Serie Patrimonio Cultural Chileno. Santiago: Ministerio de Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Ana Paula, and Guadalupe Romero Villanueva. 2020. South American Art. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by Claire Smith. Cham: Springer, pp. 9965–77. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, Francisca, Simón Sierralta, and Renata Gutiérrez. 2019. Nuevo registro de arte rupestre en pasos cordilleranos: Paredón Luisa (Cochamó, Región de Los Lagos, Chile). Magallania 47: 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Cañoles, Francisca. 2021. Archaeological analyses of pigmenting materials, a case study on Initial Late Holocene hunter-gatherers from North-Central Chile. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 36: 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Cañoles, Francisca, Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong, and Catalina Venegas. 2021a. Pinturas rupestres, arqueometría e historias en el Centro Norte de Chile (29-30 Lat. S). Anuario TAREA 8: 14–46. [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Cañoles, Francisca, Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong, Catalina Venegas, José Cárcamo, and Diego Artigas. 2021b. Rock paintings, soot, and the practice of marking places. A case study in north-central Chile. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 36: 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Cañoles, Francisca, Andrés Troncoso, Marcela Sepúlveda, José Cárcamo, and Sebastián Gutiérrez. 2016. Pinturas rupestres en el norte semiárido de Chile: Una primera aproximación físico-química desde la Cuenca del Río Limarí (30° Lat. S). Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 21: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Cañoles, Francisca, Felipe Armstrong, Mara Basile, George Nash, Andrés Troncoso, and Francisco Vergara. 2014. On-site and post-site analysis of pictographs within the San Pedro Viejo de Pichasca rock shelter, Limarí valley, north-central Chile. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelaeological Society 26: 171–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano, Ricardo, Rodolfo Angeloni, Amelia Ramírez, Leidy Arango, Juan Pablo Uchima-Tamayo, and Jacqueline Brosky. 2024. Astronomical Representations and Shamanism in the Rock Art of the Semi-Arid North of Chile. Journal of Skyscape Archaeology 10: 47–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Adriana. 2022. Una coraza de cuero de Chiuchiu: Cartas, colecciones y dataciones desde Gotemburgo, Suecia. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 53: 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Camila. 2020. Nuevas aproximaciones al arte rupestre de Fuego-Patagonia, Chile: Caracterización y comparación de los sitios del continente y de los canales del extremo sur. Magallania 48: 161–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Camila, and Diego Artigas. 2016. Dar la mano y tomarse el todo: Los sitios rupestres del Ibáñez medio como ventanas de un mundo abierto a los sistemas culturales amplios. In Arqueología de la Patagonia: De mar a mar. Edited by Francisco Mena. Coyhaique: Ediciones CIEP/Ñire Negro Ediciones, pp. 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Camila, Rosario Cordero, and Diego Artigas. 2016. El sitio Alero Picton 1: Nuevo registro de arte rupestre para los canales fueguinos. Magallania 44: 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Iván. 1983. Hallazgo de un Alouatta seniculus en el Valle de Azapa. Estudio preliminar de la iconografía de simios en Arica. Chungara 10: 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Iván, and Luis Briones. 1996. Poblados, rutas y arte rupestre precolombinos de Arica: Descripción y análisis de sistema de organización. Chungara 28: 47–84. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Iván, Juan Chacama, and Gustavo Espinosa. 1987. El poblamiento prehispánico tardío en el valle de Codpa. Una aproximación a la historia regional. Chungara 19: 7–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, George, and Andrés Troncoso. 2017. The socio-ritual organisation of the upper Limarí Valley: Two rock art traditions, one landscape. Journal of Arid Environments 143: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1958. Petroglifos y piedras tacitas en el Río Grande (Departamento de Ovalle). Notas del Museo Arqueológico de La Serena 6: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1964. Petroglifos en el curso superior del Río Aconcagua. In Arqueología de Chile Central y Áreas Vecinas. Actas del Tercer Congreso Internacional de Arqueología Chilena, Viña del Mar. Santiago: Imprenta Los Andes, pp. 133–49. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1967. Un nuevo sitio de arte rupestre en Taira (río Loa superior, Prov. de Antofagasta, Chile). Revista Universitaria LII, 143–57. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1972. Las Pinturas Rupestres de la Sierra de Arica. Santiago: Editorial Jerónimo de Vivar. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1976. La cueva con pinturas indígenas del río Pedregoso. In Actas y Memorias del Cuarto Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Argentina. San Rafael: Mendoza, pp. 339–53. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1979. Variaciones de los estilos de arte rupestre en el norte de Chile. In Actas del VII Congreso de Arqueología de Chile. Santiago: Editorial Kultrún, pp. 649–60. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans. 1985. El yacimiento de petroglifos Las Lizas (región de Atacama, provincia de Copiapó, Chile). In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 131–71. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Dominique Ballereau. 1996. Los petroglifos del Cerro La Silla, Región de Coquimbo. Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 28: 277–317. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Julio Montané. 1968. El arte rupestre indígena en la zona centro sur de Chile. In Actas y Memorias del XXXVII Congreso Internacional de Americanistas. México: Universidad Autónoma de México, pp. 419–52. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Lotte Weisner. 1972–1973. Los petroglifos de la cordillera andina de Linares (Provincias de Talca y Linares, Chile). In Actas del VI Congreso de Arqueología Chilena. Santiago: Universidad de Chile, pp. 405–70. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Lotte Weisner. 1991. El arte rupestre de la cuenca formativa del río Petorca I. Cerro Tongorito. In Actas del XI Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena. Santiago: Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología, pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Luis Arrau. 1983. Rehabilitación de las casas derruidas de Orongo en Isla de Pascua. Santiago de Chile: Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos/International Found for Monuments Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Virgilio Schiappacasse. 1963. Investigaciones arqueológicas en las terrazas de Conanoxa, valle de Camarones (Provincia de Tarapacá). Revista Universitaria 26: 101–53. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, Hans, and Virgilio Schiappacasse. 1981. Aportes al conocimiento del Período Tardío del extremo norte de Chile: Análisis del sector de Huancarane del valle de Camarones. Chungara 7: 3–103. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro. 1964. El Sacrificador. Un elemento co-tradicional andino. Noticiario Mensual del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural año VIII: 7. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro. 1965. Estudio comparativo sobre petroglifos del norte de Chile. Annals of the Náprstek Museum 4: 37–153. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro. 1967. En torno al culto de la reproducción humana en el norte de Chile. Revista Universitaria 50–51: 367–75. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro. 1976. Geoglifos y tráfico de caravanas en el desierto chileno. In Homenaje al Dr. Gustavo Le Paige, S.J. Edited by Hans Niemeyer. Antofagasta: Universidad del Norte, pp. 147–201. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro. 1985. Petroglifos y tráfico en el desierto chileno. In Estudios en Arte Rupestre. Primeras Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by Carlos Aldunate, José Berenguer and Victoria Castro. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 243–78. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro, and Luis Briones. 1967–1968. Petroglifos del sitio Tarapacá-47. Estudios Arqueológicos 3–4: 43–84. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro, and Luis Briones. 2017. Tráfico e interacción entre el oasis de Pica y la costa arreica en el desierto tarapaqueño (norte de Chile). Estudios Atacameños 56: 133–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Lautaro, and Victoria Castro. 2011. ¡Caiatunar, caiatunar!: Pervivencia de ritos de fertilidad prehispánica en la clandestinidad del Loa (norte de Chile). Estudios Atacameños 42: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Lautaro, Isabel Cartajena, Carlos Carrasco, and Patricio De Souza. 2006a. El Templete Tulán de la Puna de Atacama: Emergencia de Complejidad Ritual Durante el Formativo Temprano (norte de Chile). Latin American Antiquity 17: 445–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Lautaro, Isabel Cartajena, Carlos Carrasco, Patricio De Souza, and Martín Grosjean. 2006b. Patrones, cronología y distribución del arte rupestre arcaico tardío y formativo temprano en la cuenca de Atacama. In Tramas en la Piedra. Producción y Usos del Arte Rupestre. Edited by Dánae Fiore and María Mercedes Podestá. Buenos Aires: World Archaeological Congress, Asociación Amigos del INA y Sociedad Argentina de Antropología, pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro, Isabel Cartajena, Juan Pablo Loo, Santiago Ramos, Timoteo Cruz, Tomás Cruz, and Héctor Ramírez. 1997. Registro e investigación del arte rupestre de la cuenca de Atacama (Informe Preliminar). Estudios Atacameños 14: 307–25. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro, Isabel Cartajena, Patricio De Souza, and Carlos Carrasco. 2009. Los estilos Confluencia y Taira Tulán: Ritos rupestres del Formativo Temprano en el sureste del Salar de Atacama. In Crónicas sobre la Piedra. Arte Rupestre de las Américas. Edited by Marcela Sepúlveda, Luis Briones and Juan Chacama. Arica: Ediciones Universidad de Tarapacá, pp. 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Lautaro, Luis Briones, and Persis B. Clarkson. 2022. Geoglifos hispanicos del desierto de Atacama (norte de Chile). Diálogo Andino 69: 122–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, Patricio, and Rodolfo Contreras. 2003. Pinturas prehispánicas de Taltal. Antofagasta: Ilustre Municipalidad de Taltal y Universidad de Antofagasta. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Patricio, and Rodolfo Contreras. 2005. Las pinturas prehispanas del área de Taltal. Análisis descriptivo e interpretativo. Pacarina V: 113–22. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Patricio, and Rodolfo Contreras. 2006. El arte rupestre de Taltal. In Actas del 5º Congreso Chileno de Antropología: Antropología en Chile. Balance y Perspectivas. Santiago: Colegio de Antropólogos de Chile, pp. 348–57. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, Patricio, and Rodolfo Contreras. 2011. Arte abstracto y religiosidad en el arcaico costero; Punta Negra-1c, Paposo Taltal, Norte de Chile. Taltalia 4: 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, Mario. 1996. Historia de la Arqueología en Chile (1842–1990). Santiago de Chile: Colección de Ciencias Sociales, Bravo y Allende Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio, Mauricio, Víctor Lucero, and Francisco Mena. 2006. Puesta en valor del arte rupestre del valle del Río Ibáñez. XI Región de Aysén. In Actas del 5º Congreso Chileno de Antropología: Antropología en Chile. Balance y Perspectivas. Santiago: Colegio de Antropólogos, pp. 330–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzún, Aureliano. 1910. Los petroglifos del Llaima. Boletín del Museo Nacional de Chile II: 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Edithe. 2006. Historia de la investigación sobre el arte rupestre en la Amazonia brasileña. Revista de Arqueología Americana 24: 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Philippi, Raimundo A. 1860. Viaje al desierto de Atacama hecho de orden del Gobierno de Chile en verano 1853–1854. Halle: Librería Eduardo Anton. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, Sujitha. 2022. Rock art research in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 147–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo. 2003. Identidades, caravaneros y geoglifos en el Norte Grande de Chile. Una aproximación teórico-metodológica. Boletín de la Sociedad Chilena de Arqueología 35/36: 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo, and Indira Montt. 2008. Tarapacá en Atacama. Arte rupestre y relaciones intersocietales entre el 900 y 1450 d.C. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 13: 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo, Charles Rees, Patricio de Souza, and Lorena Arancibia. 2011. Viajeros costeros y caravaneros. Dos estrategias de movilidad en el Período Formativo del Desierto de Atacama, Chile. In En ruta. Arqueología, historia y etnografía del tráfico sur andino. Edited by Lautaro Núñez and Axel E. Nielsen. Córdoba: Encuentro Grupo Editor, pp. 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo, Indira Montt, José Blanco, and Alvaro Reyes. 2007. Infraestructura y prácticas de movilidad en una ruta que conectó el Altiplano Boliviano con San Pedro de Atacama. In Producción y circulación prehispánicas de bienes en el Sur Andino. Edited by Axel E. Nielsen, M. Clara Rivolta, Verónica Seldes, María M. Vázquez and Pablo Mercolli. Córdoba: Editorial Brujas, pp. 351–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo, Mariana Ugarte, Francisco Gallardo, José F. Blanco, and Claudia Montero. 2017a. Chug-Chug en el contexto de la movilidad internodal prehispánica en el Desierto de Atacama, Chile. Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena 49: 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, Gonzalo, Mariana Ugarte, José Blanco, Christina Torres-Rouff, and William J. Pestle. 2017b. Calate. De lugar desnudo a laboratorio arqueológico de la movilidad y el tráfico intercultural prehispánico en el desierto de Atacama (ca. 700 AP–550 AP). Estudios Atacameños. Arqueología y Antropología Surandinas 56: 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plagemann, Albert. 1906. Über die chilenischen ‘Pintados’. Beitrag zur Katalogisierung und vergleichenden Untersuchun der südamerikanischen Piktographien. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Podestá, María Mercedes, and Matthias Strecker. 2020. South American Rock Art. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Podestá, María Mercedes, Cristina Bellelli, Rafael Labarca, Ana M Albornoz, Anabella Vasini, and Elena Tropea. 2008. Arte rupestre en pasos cordilleranos del bosque andino patagónico (El Manso, Región de los Lagos y Provincia de Río Negro, Chile-Argentina). Magallania 36: 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, Irina. 2022. A history of rock art research in Russia. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 160–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rainsbury, Michael P. 2022. Explorers and researchers: Kimberley rock art discoveries 1838–1938. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Joakim Goldhahn and Sam Challis. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 126–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, José Miguel. 1988. Rapa Nui, un milagro en el Pacífico Sur. In Los Primeros Americanos y sus Descendientes. Santiago de Chile: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino/Editorial Antártica, pp. 369–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, Mario A., and Branko Marinov. 2001. Arte rupestre y arqueología del sitio Laguna-Este, Alto río Loa, norte de Chile. In Segundas Jornadas de Arte y Arqueología. Edited by José Berenguer, Francisco Gallardo, Luis Cornejo and Carole Sinclaire. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, pp. 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Álvaro. 1996. Enfrentamientos rituales en la Cultura Arica: Interpretación de un ícono rupestre. Chungara 28: 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Álvaro, Gustavo Espinosa, Luis Briones, and Rolando Ajata. 2004a. Educación de patrimonio y puesta en valor de un sitio con petroglifos, valle de Codpa, Norte de Chile. In Actas del VI Simposio Internacional de Arte Rupestre, Jujuy, Argentina. Fomato CD-ROM. San Salvador de Jujuy: Universidad Nacional de Jujuy. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Álvaro, Rolando Ajata, Gustavo Espinosa, and Luis Briones. 2004b. Arqueología pública y comunidades rurales, un proceso de puesta en valor en el valle de Codpa, Región de Tarapacá. Boletín del Museo Gabriela Mistral de Vicuña 6: 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rydén, Stig. 1944. Contributions to the Archaeology of the Río Loa Region. Goteborg: Elanders Boletryckeri Aktiebolag. [Google Scholar]

- Sade, Kémel. 2016. Pinturas rupestres de guanacos (L. guanicoe) en Aysén (Patagonia, Chile). Aysenología 2: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sade, Kémel. 2018. El sitio arqueológico Alero Sin Nombre (Noroeste del Lago General Carrera, Región de Aysén, Chile). Aysenología 5: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sade, Kémel, and Fernando Castañeda. 2017. Sitios arqueológicos del Noroeste del Lago General Carrera Cuenca del Río Baker, Aysén, Chile. Aysenología 3: 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sade, Kémel, Fernando Castañeda, and Leonardo Pérez-Barría. 2019. Poblamiento y registro arqueológico de la costa sur del lago General Carrera (Río Baker, Región de Aysén, Chile). Aysenología 6: 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Diego, Donald Jackson, and Andrés Troncoso. 2006. Introducción: Hacia una teoría de la teoría arqueológica. In Puentes hacia el pasado: Reflexiones teóricas en arqueología. Edited by Donald Jackson, Diego Salazar and Andrés Troncoso. Santiago: GTAT Grupo de Trabajo en Arqueología Teórica, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]