Thanks to advances in both photography and papermaking, the end of the nineteenth century saw the explosion of a popular new consumer good: the picture postcard. Produced relatively cheaply and in large quantities, postcards provided broad access across class divides to ownership of printed images. As a result, picture postcards became attractive to consumers not simply as an inexpensive form of communication but also as objects for collection. As consumer demand for postcards grew, manufacturers fed the collecting craze by producing cards featuring famous sites and monuments as well as luminaries on the contemporary cultural scene. As a result of this immediate connection to their time, postcards can serve as especially intriguing subjects for analysis and inquiry, because they reflect both the cultural values of the time of their production and the tastes of contemporary consumers.

One genre of picture postcards that was particularly popular in Russia at the turn of the century was the literary postcard. The emergence in nineteenth-century Russia of a truly national school of literature helped promote what

Benedict Anderson (

2006) has called an “imagined community,” fostered by the development of print technology and the use of a common language spread through print media (p. 46). As literature came to occupy a central position in the country’s cultural narrative, it helped shape the concept of Russian national identity and frame the discourse surrounding it.

Jeffrey Brooks (

1985) notes that “educated activists” and “the new intelligentsia” emerging towards the end of the nineteenth century embraced the promotion of national identity through “a cultural identification” with literature in the belief that Russian canonical writers “stood for what was best and noblest in educated Russia” (p. 333). Publishers quickly put the picture postcard into service of this cause of promoting Russian literature as a locus of shared or “imagined community”—in this case through readily recognized images of the nation’s iconic writers.

The popularity of literary postcards and, as a result, the rapid proliferation of cards featuring portraits of contemporary writers also helped feed celebrity culture (

Rowley 2013, p. 78), both in Russia and abroad, and turned those images into sought-after commodities for consumption. It is not surprising in this regard that many of the literary postcards still on the market have not gone through the post, indicating that they functioned not as practical items of stationery, but rather as objects for collection. As Alison Rowley notes in her book on postcards in popular Russian culture, many cards have traces of tape on them or holes from nails or tacks, which points to the fact that they were collected and put on display in people’s private spaces (pp. 9, 84).

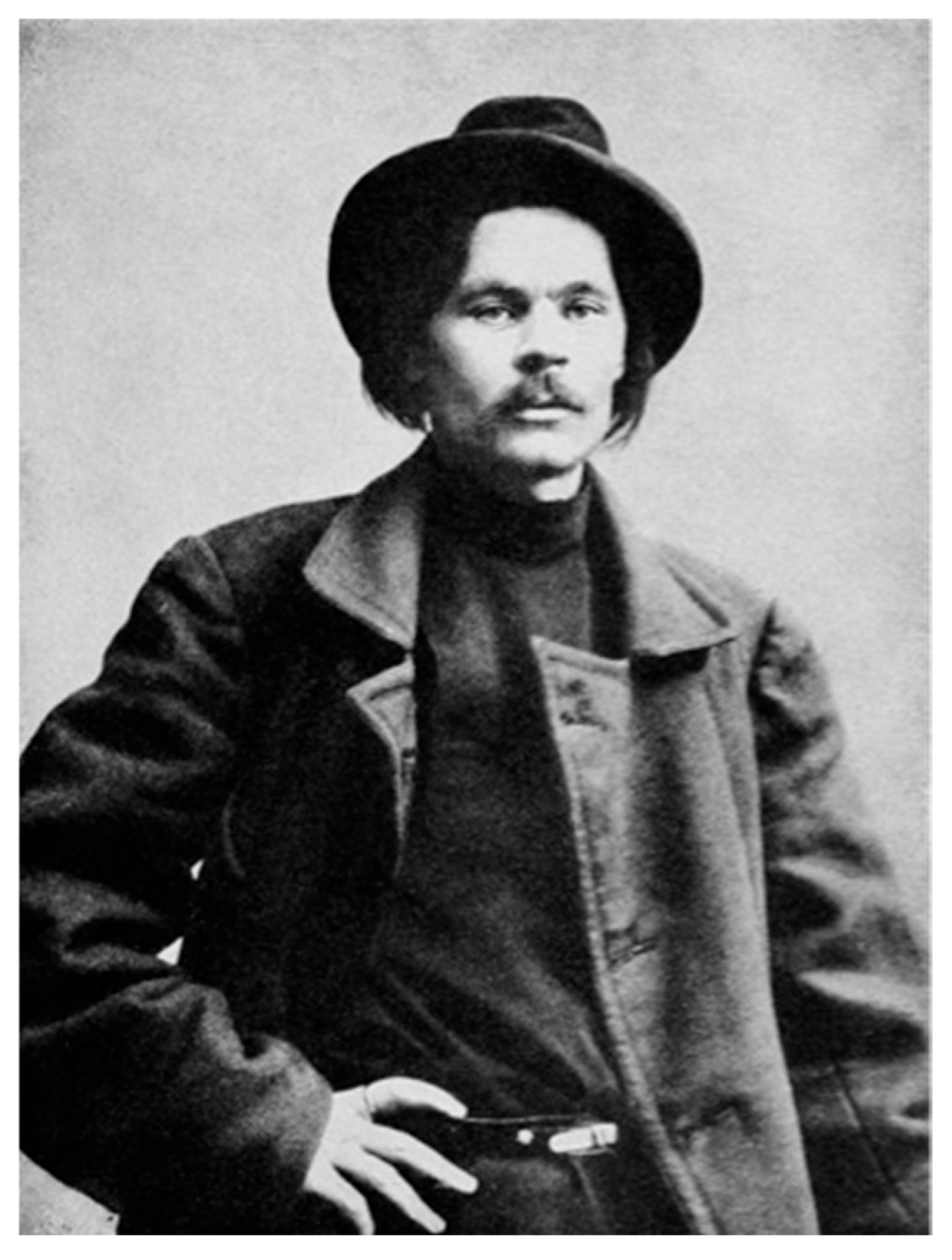

As a rising star on the literary scene at that time, Maksim Gorky (1868–1936) quickly became an icon of contemporary Russian youth culture and, consequently, a popular subject for picture postcards (

Figure 1). Gorky’s physical image itself demonstrated his difference from established traditional norms for the profession of “writer”: he wore high boots and long, belted shirts in the Russian peasant style, and his thick, combed-back hair often fell in unruly tufts at his temples or forehead. His revolutionary leanings and unconventional life similarly challenged the dominant mores of the time. At the same time, Gorky’s writings, which told of the downtrodden and oppressed, did not fit into that idea of celebrating the nation and instead exposed the injustice of the existing order. Such views on his part were especially attractive to the “educated activists” that

Brooks (

1985) refers to, a generation coming of age on the cusp of the “modern” and socially and culturally oriented towards a rejection of the traditional values of the past.

Gorky’s open support of revolutionary change resulted in periods of brief imprisonment, yet his massive popularity—both in Russia and abroad—kept tsarist authorities from being able to take harsher measures to silence him; indeed, outrage and intercessions on his behalf by influential figures helped ensure the brevity of his periods of incarceration (

Yedlin 1999, pp. 26, 31). Though Gorky was sincere in his political beliefs and often fearless in expressing them, he also clearly benefited from his celebrity; it allowed him to be outspoken while also giving him a degree of immunity from punishment. In this sense, he is not unlike the “defiant” individuals at the end of the nineteenth century who, in

Sharon Marcus’s (

2019) formulation, “became popular not despite but

because of their unruly individuality” (p. 29).

Gorky’s example points to the power of celebrity culture and the way it “is irrevocably bound up with commodity culture” (

Rojek 2001, p. 14), even in a state as repressive as tsarist Russia. Postcards featuring Gorky flooded the market at the turn of the century, and they were an especially popular collectible good among young people at the time. Though a few of those cards were published by the leading Russian postcard manufacturers, including Richard (Ришар) and Scherer, Nabholz, and Co., many more were published cheaply by smaller firms or non-Russian firms, and some of them bear no publication markings at all. Nonetheless, they found a ready market among Gorky’s fans both in Russia and abroad. Evidence of collection can be seen in the pinholes found on some cards (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), which indicate that they were hung in the owner’s private space. Individualized touches like these pinholes enrich the history of these particular cards because they offer evidence of the way celebrity postcards did indeed function, in the words of historian Louise McReynolds, as “icons of the secular age” (quoted

Rowley 2013, p. 81).

Gorky’s influence on contemporary Russian youth culture–and its connection to his physical appearance–can further be seen in an excerpt from the memoirs of children’s writer Samuil Marshak about when he first saw Gorky’s image as an adolescent at his gymnasium in Ostrogozhsk: “I was about thirteen or fourteen when I attentively examined along with my classmates a postcard that was being passed from hand to hand on which was depicted а high-cheek-boned young man with a dreamy-gloomy face, with a striking shock of straight hair falling onto his temples. He was wearing a white Russian shirt, tied with a rope. This was Gorky” (

Marshak 1971,

V nachale zhizni).

Marshak writes how he and his young friends were captivated by Gorky—his background, his appearance, and even his name, which, of course, spoke to them about “a bitter fate, akin to the fates of many in Russia. And at the same time,” he added, “it sounded like a protest, like a challenge, like a promise to speak the bitter truth.”

1 And Gorky’s works themselves, he wrote, showed young people characters who boldly struck out on their own paths through life. For the young Marshak and his contemporaries, Gorky was “the most modern of all modern writers. His voice for my generation was the voice of the time—and not only of the present, but also of the future.” The disapproval of their elders, who called Gorky “a pretender (самозванец) who had invaded the Turgenevian gardens of Russian literature,” simply amplified why he appealed so much to contemporary Russian youth. As Marshak notes, “no skeptical comments could cool down the youth, who were already in love with him.” One should, of course, question the extent to which the Marshak who penned these words (a well-established Soviet writer) was providing the memoir of Gorky his Soviet colleagues expected. Moreover, Marshak was befriended by Gorky as a teenager and even lived with Gorky’s family in Yalta as he convalesced from tuberculosis. Nonetheless, the passage gives us valuable insight into how the writer was received by his young fans at the time, including those living in provincial cities.

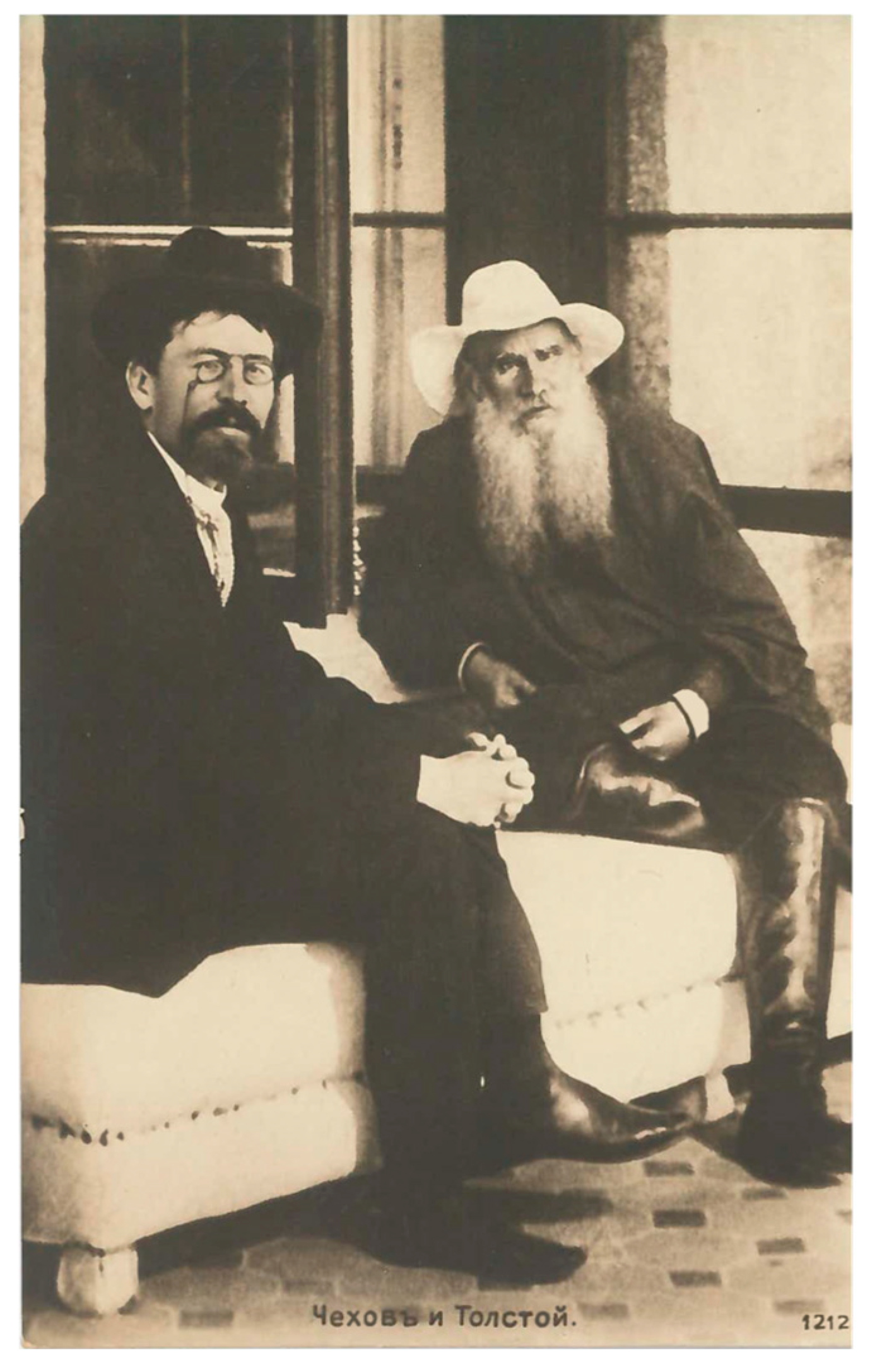

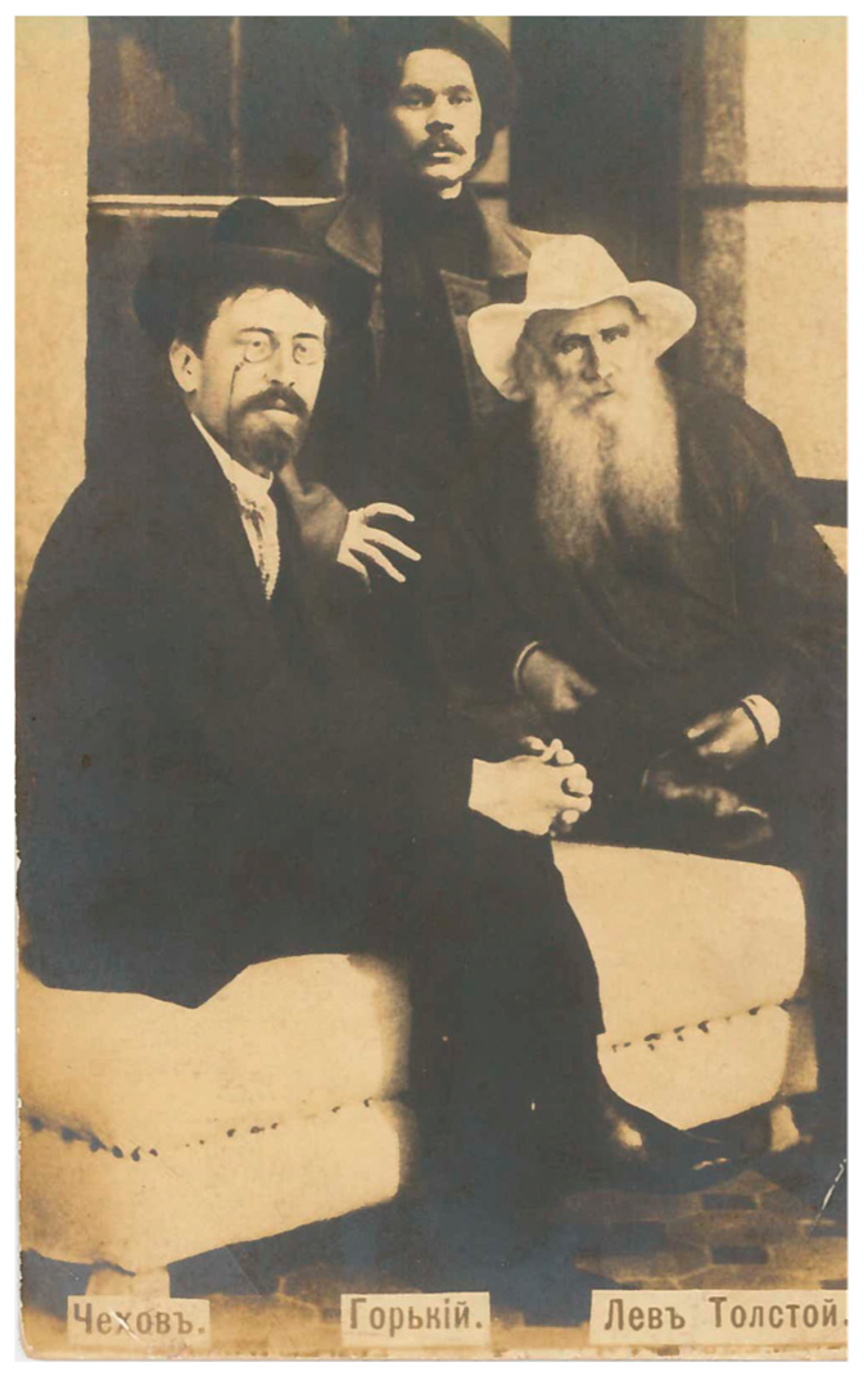

Despite this association of Gorky with the “modern,” images of the writer with mainstream figures of Russian literature were also quite popular on early postcards, and the now famous photographs of Gorky with Tolstoy and Gorky with Chekhov were widely circulated at the time. But sometimes consumers wanted more, and postcard manufacturers were not above capitalizing on literary celebrity and manipulating those images to stimulate sales. For example, P. B. Sergeenko’s famous photo of Tolstoy and Chekhov in Yalta (

Figure 6) was edited in the card shown in

Figure 7 to squeeze in the image of Gorky from a different photograph (

Figure 8). Such manipulation of photographs allowed consumers to possess the image of all three literary celebrities at once.

Early postcards of Gorky also on occasion used pieces of text from his works to complement his image, as on the card in

Figure 9, which was issued in 1903 by the Moscow firm Scherer, Nabholz, & Co. The passage—“A man is valued according to his resistance to the force of life” (“Человек ценен по своему сопротивлению силе жизни”) —comes from Gorky’s 1899 novel,

Foma Gordeyev, and it speaks to the need to fight back against fate and to shape life according to one’s own desires. Inspirational quotes such as this, ostensibly in Gorky’s own handwriting, invite the reader to associate words spoken by one of Gorky’s characters with the writer himself, linking the writer’s celebrity not only to his image but also to the literary text he produced. At the same time, they also add another layer to the postcard as an object and lend it a greater sense of authenticity and personal connection. Now the viewer not only sees Gorky’s image but also hears his voice; an even deeper communion between the writer and his readers is the result.

Gorky’s literary reputation was furthered by the Moscow Art Theater’s 1902 production of his play

The Lower Depths (

На дне), which depicted the lowly and downtrodden elements of tsarist society. Postcards from that production quickly appeared, as did several cards from different manufacturers featuring the popular song from the play, “The Sun Rises and Sets” (“Солнце всходит и заходит”) (

Figure 10). The lyrics for this song—which is sung by Volga tramps—convey a longing for freedom from prison chains and an incapacity to achieve it, a theme that surely spoke to the socially minded youth of the time. These cards—and even some contemporary sources—inaccurately identify Gorky as the author of the lyrics, when in fact the song predates Gorky’s play by at least a decade and was known as a prison folk song. Such facts were clearly unimportant to postcard manufacturers, who freely mixed genres and blurred authorship in the name of capitalizing on Gorky’s celebrity. At the same time, this comingling of the writer’s image and his implied text from the play he authored offers evidence of how such postcards helped shape shared cultural knowledge; the song’s true provenance is lost as it becomes instead an extension of the writer’s identity and his message.

Yet another version forgoes Gorky’s image entirely in favor of N. A. Yaroshenko’s well-known painting “The Prisoner” (Заключённый) from 1878 (

Figure 11). One could argue that this card, which was posted in 1911 to Shavli in Lithuania, foregrounds even more poignantly the song’s message and ties it here not simply to Gorky, but to the nation’s long history of oppression and harsh punishments.

Neither of these two cards identifies the publisher. Nonetheless, the manufacturers’ determination to combine visual images with both literary and musical text raises interesting questions about the intended audience. Though there appears to be an assumption of both literary sensibility and musical knowledge on the part of their consumer, the graphics and design of both cards (especially the second) are crude and crowded, and it is doubtful that any reader could meaningfully engage with either text.

Around the same time, photographs of Gorky with his contemporaries from the literary group

Moskovskaia literaturnaia sreda also became popular subjects for postcards, and we can assume that at least part of the appeal lay in their youthful appearance and clear link to the “modern,” as Marshak described it. There are several versions of these group photos featuring Gorky, Shaliapin, Andreyev, Bunin, Skitalets, and others. Yet even here we see differences within the group itself through their clothing: Gorky, Andreyev, Skitalets, and Shaliapin are wearing long, belted Russian shirts, the “uniform” the young Gorky was known for. This nonconformism is not seen—at least in their dress—in the other members of the group, who are wearing more traditional collared shirts with ties and suit coats (

Figure 12).

As

Sharon Marcus (

2019) notes in

The Drama of Celebrity, many celebrities “play a key role in crafting their personae” (p. 220). Gorky’s careful posing in both his individual and group portraits indicates that he well understood the power of his image and willingly played into its capture and proliferation. The head thrown back, the folded arms, the tilted hat, the chin resting on the fist all point to performance, to the fact that Gorky was crafting his image and, in doing so, inviting the adoration of his fans. His literary

celebrity—as opposed simply to being a famous writer—was certainly fed by cultivating and commodifying that physical image in response to consumer demand.

Postcards featuring photos of Gorky with individual members of the

Sreda group, such as the opera singer Fyodor Shaliapin and the writer Stepan Skitalets, were also popular with the market (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). As with most of these images, several postcard versions exist for each, and manufacturers continued to produce cards for years after the original images were captured. The card in

Figure 14 featuring Gorky with Skitalets playing a gusli was sent at the end of 1914, when Gorky was well into his forties. Though it is unclear why the sender selected this card, it does suggest that more than a decade after its issuance, this image retains its appeal for those still captivated by the youthful ideal.

A card featuring Gorky and Shaliapin sent in August 1902 to a girl named “Revekushka” in Riga is especially revealing, given the inscription (

Figure 15). The author, a student, is writing to tell her about his classes, but he begins his note with a topic that is clearly more important to them: “Write me, please, if you have Figner or Tolstoy with Gorky. If not, then I’ll send them to you.” (Напиши мне, пожалуйста, есть ли у тебя Фигнер и Толстой с Горьким. Если нет, то я тебе пришлю.) This card—as much as those with pinholes—shows how postcard collecting of favorite celebrities, including Gorky, was indeed a popular pastime among Russian youth. Similarly to what we see with Marshak, the diaries and memoirs of his contemporaries Ilya Ehrenburg and Sergei Prokofiev also mention the popularity of postcard consumption and collecting (

Rowley 2013, pp. 15, 31, 37).

Gorky’s non-conformism was also evident in his personal life. Though Gorky never officially divorced his wife Yekaterina, by whom he had two children, he parted with her in 1904 to pursue a relationship with Marya Fyodorovna Andreyeva, an actress with the Moscow Art Theater who became his common-law wife. In 1905 Gorky and fellow

Sreda member Leonid Andreyev were photographed with their wives in the studio of the painter Ilya Repin. The photos were widely circulated at the time and quickly made their way to postcards, which were numbered consecutively (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17).

2 Yet the fact that Andreyeva shared the same last name as Gorky’s friend apparently confused the postcard publisher—in this case, a German firm—resulted in a mislabeling of the cards. The label for the card in

Figure 16 says “Gorky with Andreyev’s wife,” and the one in

Figure 17 says “Andreyev with Gorky’s wife.” Gorky, however, was indeed posing with Marya Andreyeva, while Andreyev was depicted with his own wife. Though unintentional, the “wife-swapping” implied by this mislabeling helped reinforce impressions of these young writers as challenging the dominant mores of the time.

Given his interests in and support of Marxist social-democrat causes, there is certainly some irony in the use and proliferation of Gorky’s celebrity and image for the capitalist cause of profit. Yet some manufacturers used postcards to serve polemical purposes to challenge the worthiness of that celebrity. A rare postcard from 1903 pokes fun at Gorky and his crowd by punning on his name and depicting the young writers as stoppers on bottles of “Fashionable vodkas,” with tastes ranging from bitter (горькая) to semi-bitter (полугорькая) to little-bitter (малогорькая) to sweet (сладкая). The producer of this postcard—presumably someone of more conservative tastes—further mocks the popularity of Gorky and his contemporaries by adding a parenthetical statement under the title, a phrase playing on Tolstoy’s essay, “Why do people stupefy themselves?” (Для чего люди одурманиваются?), changing it to чем люди одурманиваются—“how [or by what means] people stupefy themselves” (meaning by reading such writers, of course) (

Figure 18).

The “photographic record” of Gorky’s life wanes significantly in the years following his self-imposed exile to Capri in 1906, where he sought respite from continual state surveillance and a milder climate for his failing health. While there he continued to work for the revolutionary cause, but it is important to note that Gorky was never an entirely orthodox revolutionary, a fact that frustrated Lenin. He did not affiliate with any single party and in fact gave support to different organizations within the movement, “even those mutually hostile” (

Kaun 1930, p. 440). Gorky’s views of the revolutionary cause were more “romantic and idealist,” seeing it “as a vast struggle of the human spirit for freedom, brotherhood and spiritual improvement” (

Figes 1996, pp. 16–17). Such a view, of course, did not sit well with the dogmatic Lenin, and though their relationship was initially friendly, it became increasingly fraught during these years due to regular disagreements between the two men.

When Gorky returned to Russia in 1914, he resumed writing and publishing, voicing his opposition to the war and promoting culture as humanity’s saving force. In the months after the revolutions, Gorky published his “Untimely Thoughts,” pieces critical of the revolution and condemning the destructive violence it brought with it. Such writings angered Lenin, who more than once expressed frustration with Gorky’s forays into political expression. In one of his March 1917 “Letters from Afar,” Lenin expressed bitterness upon reading Gorky’s latest call for peace: “There is no doubt that Gor’kii is a great literary talent who has brought much that is useful to the world proletarian movement. And will bring even more. But, why is Gor’kii meddling in politics?” (

Yedlin 1999, p. 115)

3When the revolution came, Gorky’s response was hostile: “He accused the Bolsheviks of betraying the idea of the socialist proletariat and relying on a pack of drunken soldiers for the sake of seizing power.” (

Clark et al. 2007, p. 76) He actively fought to defend writers and other members of the intelligentsia against Bolshevik excesses and voiced his opposition openly, writing “harsh personal letters to Lenin and sharp political statements to the Politburo” (p. 77). In the new Soviet context, Gorky’s celebrity brought a power similar to what it did in the tsarist period—his fame and authority made him untouchable, and party leaders quickly had to adjust to the “Gorky factor” (p. 76).

Postcards from this period are, understandably, rare—the “postcard craze” of the so-called Golden Age from the earlier part of the century had died out, and the war, followed by the revolution, naturally took center stage. Nonetheless, when appealing for aid for famine victims in 1921, the RSFSR took advantage of Gorky’s celebrity and used an image of the writer on a postcard to raise money for the cause. (

Figure 19 and

Figure 20).

Gorky left Soviet Russia that same year—ostensibly for health reasons, but clearly also in opposition to many of the prevailing directions of the Soviet regime. He spent the next ten years living with his extended family in Sorrento.

Despite his absence, Gorky retained his popularity in his homeland throughout this period. Stalin, rising to power after the death of Lenin, saw and well understood the force of Gorky’s celebrity, and he also recognized the power of writers, in general, to sway people’s sympathies and promote a sense of shared national identity. In the Soviet context, however, the concept of celebrity becomes more complicated. Once the state assumed the role of media producer, it also gained control of whose works were published and who received official recognition. In this respect, the symbiotic relationship that Sharon Marcus describes among “media producers, members of the public, and celebrities themselves” (p. 3) no longer functioned so neatly. As a result, the pre-revolutionary cult of the writer persisted in the new Soviet regime, but it was now explicitly tied to “the political context” (

Harrington 2016, p. 511), as the state took over the role of creating celebrities.

Kevin Morgan (

2017), in his book on the cult of the individual in the early Soviet Union, notes how “the claim was made that it was precisely in Russia that the writer had retained a sense of mission largely relinquished further west,” and Stalin’s description of writers as “engineers of human souls” cast the writer in the role of educator and moral force (p. 204). Gorky’s fame as a writer was always situated in the context of his subject matter—exposing the underside of tsarist Russian society, its injustices and backwardness. He was thus well suited to assume the mantle of a genuine “Soviet” writer due to his repudiation of the previous regime. The fact that he had challenged the moral underpinnings of the new regime in his writings was an inconvenience, but not an impediment.

Stalin made his move toward bringing Gorky back into the fold in May 1928, inviting him to return home to the Soviet Union to celebrate his 60th birthday and 35th anniversary of his literary career. Gorky was overwhelmed with accolades and adoration as he was proclaimed to be “the first proletarian writer” and the Gorky myth was born (

Yedlin 1999, p. xi). After that visit, Gorky gradually began to split his time between Moscow and Sorrento until 1933, when he returned to Moscow for good. Stalin cultivated a close relationship with Gorky and flattered his ego by elevating his stature as “the father of Soviet literature.” Though Gorky continued on occasion to intercede for writers and other members of the intelligentsia against the regime’s control, he essentially succumbed to the role imposed upon him by Stalin, one that seemingly accorded him great acclaim and authority but in reality locked him into the narrative of friend of Lenin, tribune of the Soviet project, architect of Socialist Realism, and implicit supporter of Stalin and his policies.

With Gorky’s return to the Soviet Union came the return of the photo-documentation of his life. Images of Gorky from 1928 to 1936 are abundant, yet few postcards of Gorky actually published during that period can be found on the current market; a search of online collections is similarly unproductive. A card depicting Gorky among workers at the Baltic Shipbuilding factory appears to be one of those rarities, and it comes from a series from the early 1930s called “Industrial Leningrad,” with photographs by N.N. Shtertser. (

Figure 21) Though there are many postcards on the market featuring photographs from Gorky’s final years, the manufacture date of those cards is in fact much later.

Gorky’s death in 1936 did prompt the issuance of a series of cards both commemorating his later years and documenting the funeral itself. Though some mystery remains about the causes and circumstances of Gorky’s death, the state response was unambiguous and absolute in its elevation of the writer to national hero and one worthy of a massive state funeral. That event was, of course, recorded on film and by photographs, and the latter were, in turn, disseminated through picture postcards. Series of postcards issued in 1936 by Soyuzfoto and copyrighted for distribution in Amsterdam and New York included photographs of the mature Gorky in his final years as well as images from the funeral itself—street scenes of the mass outpouring of grief that accompanied his passing, the obligatory coffin shot, and a photo of Stalin and Molotov in the honor guard next to the coffin. (

Figure 22 and

Figure 23) By participating in this capacity and standing by Gorky’s coffin, Stalin and Molotov both affirm the stature of the deceased writer and ensure their own legitimacy as his colleagues in the cause.

Gorky’s death, in fact, allowed the state to capitalize more fully on the power of his celebrity and implement a reinscribed Gorky myth, one in which he served as a paragon of Soviet virtues, unwavering in his support of the nation and its leaders. To make that myth more real, his life was censored under Stalin with inconvenient truths removed from his published works and correspondence (

Yedlin 1999, p. xi). In this role, his name became ubiquitous, as his hometown of Nizhny Novgorod was renamed Gorky in his honor, and streets, theaters, museums, and parks followed suit.

This myth-building around Gorky is also reflected in postcards issued after the war and in the subsequent decades, both before and after the death of Stalin. Yet the creation of this myth required the creation of new images; as a result, many postcards of Gorky from this period render his image through paintings instead of photographs. These paintings offered scenes from Gorky’s life—many of them imagined—and helped reinscribe a revised biographical narrative.

The card in

Figure 24, for example, features V. P. Efanov’s 1944 painting depicting Stalin, Voroshilov, and Molotov by the bedside of the mortally ill Gorky. Though Stalin apparently did visit the dying Gorky, it seems unlikely that the scene played out in this way, especially given the fact that Stalin had grown increasingly unhappy with Gorky in his final years. But the myth of Gorky (and, at this point, of Stalin) required such revisions to history. As in the funeral photo, the linking of Gorky with Stalin (as well as with Voroshilov and Molotov, in this case) provides a mutual affirmation of stature and a symbolic nod to a shared purpose.

Similarly, the cards in

Figure 25 and

Figure 26, issued in 1957, feature works by the artist P.V. Vasiliev, and they reunite Gorky with his “friend” Lenin. In the first, entitled “V.I. Lenin and A.M. Gorky listen to a pianist,” we see them as men of fine tastes. The second card depicts them playing chess under the watchful eye of Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife.

4 Such scenes must be based at least in part on fantasy, given Gorky’s bitterness toward the role Lenin played in orchestrating the October revolution and his own departure to Sorrento in 1921, in some accounts at the forceful urging of Lenin. These paintings—and their dissemination through postcards—illustrate the mythmaking around both men, especially in the post-Stalin period.

The publishing house Sovetskii Khudozhnik also issued cards depicting scenes from Gorky’s works, like the one from 1953 in

Figure 27, which depicts the disabled boy Lenka from Gorky’s 1913 story “Strasti-Mordosti,” commonly translated as “Hobgoblins.” The child of a prostitute, living in terrible poverty, with withered legs, Lenka gains deep sympathy from the story’s first-person narrator, who, not surprisingly, in this rendering looks an awful lot like the young Gorky. Here again we see a deliberate blending of the writer’s literary output and his own biography.

Paintings of the young Gorky at various stages of his life were also part and parcel of Socialist Realist art in the post-war period, and they too served to inscribe the biographical narrative. Though produced by different painters and in different years, the image of the young Gorky remains static, wearing that “white Russian shirt tied with a rope” that Marshak had described from the postcard he had seen in his youth. Those youthful photographs of Gorky posing with his friend Shaliapin are now replaced with P.D. Buchkin’s painting of the two by a river, with the young Gorky—in his usual attire—reading one of his works to a thoughtful Shaliapin. (

Figure 28) M. A. Suzdal’tsev’s 1954 painting “Off to Meet Life” (На встречу жизни) depicting a young Gorky heading off from home, with the Nizhny Novgorod cityscape behind him, contributes to the romantic mythology surrounding Gorky’s youthful wanderings and what he learned about life through his travels. (

Figure 29) Similar cards feature G. S. Melikhov’s painting of Gorky (in his white shirt) reading to peasants in Ukraine or A. I. Kirillov’s depiction of Gorky (again in his shirt) rehearsing

The Lower Depths with actors from the Moscow Art Theater. The effect of such images is to cement the myth, to lock the young Gorky in the role of pedant, robbed of the independence that originally characterized him. Instead, he is a tool for the state, carrying out the writer’s prescribed mission as “engineer of human souls.”

The cult of the writer, such a crucial element of nineteenth-century Russian intellectual and cultural history, is compellingly reflected in the rich abundance of literary postcards produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As one of the most popular subjects for such cards, Maksim Gorky functioned as a symbol of independence and iconoclasm, attracting the attention and adoration of Russian youth through both his writings and his unconventional appearance. His deliberate style of dress, his unruly hair, and his careful posing were all captured by the camera and transferred to the picture postcard. Widely reproduced, disseminated, and collected, Gorky’s photographic image played a key role in advancing his celebrity both in Russia and abroad.

In

The Drama of Celebrity,

Sharon Marcus (

2019) posits that “[a]gency is everywhere in celebrity culture, and always up for grabs” (p. 20). Yet in some ways the example of Gorky challenges this assertion. Though the cult of the writer persisted in the Soviet context, it was now promoted not by socially conscious activists but by the state itself; the elevated role of the writer became part of the political project, with the state functioning as the uncontested agent of celebrity. In such a context, the individual agency of the celebrity is lost. The state’s manipulation of Gorky’s image and biographical narrative on Soviet postcards, especially those issued after his death, stands in sharp contrast to the willful self-fashioning Gorky indulged in when he first became famous. He remained a celebrity, but no longer one of his own making. Whether reissues of earlier photographs or photographs after his return to the Soviet Union or Socialist Realist paintings depicting imagined scenes from his life, those posthumous cards play a political role, depriving Gorky of his dynamism and creating instead a static, state-imposed narrative of a different sort of celebrity. The early image of Gorky, which spoke so powerfully to Russian youth and others sympathetic to radical change was co-opted by the Soviet regime and molded to serve instead, ironically, as a symbol of political orthodoxy and conformity.