Abstract

In 1913, the Fabergé workshops in St Petersburg produced the most expensive of their famed Imperial egg commissions, the so-called “Winter Egg,” designed by Alma Pihl. Fashioned from translucent rock crystal and decked in a glittering array of gemstones, the egg followed several other designs on winter themes by the highly respected jeweller. In this article, Fabergé’s winter-themed creations are the starting point for an exploration of how ice, frost, and snow were portrayed by Russian artists of the late imperial period. Such works both reflected and realised many of the shifts in the art world from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, for example, the renewed focus on making art “national,” the rise of artistic opportunities for women, the erasure of boundaries between fine and applied art, the influx of such European movements as Impressionism and Symbolism, and the development of modernist approaches to content and style. The principal focus is on works by artists associated with the Abramtsevo artistic circle (Abramtsevskii khudozhestvennyi kruzhok). How did representations of ice, snow, and frost participate in the emerging dynamic between the national idea and the decorative, which in turn fed into the move towards abstraction? Why did these subjects appear frequently in art by women? Why was winter often presented through the lens of the imagined and the ludic? These works evidence a new subjectivity that arose from Abramtsevo artists’ greater freedom to render lived experience. The paths open to them when working outside the Academic system permitted creativity to range freely in the forging of a national modern style.

When the young artist Alma Pihl (1888–1976), was tasked by her uncle, Fabergé head jeweller Albert Holmström, to design a commission of forty brooches for the industrialist Emanuel Nobel, she came up with an inspired plan.1 Seeing patterns of ice on the workshop window, Pihl decided upon winter as the unifying theme for the collection. Translating the ephemeral beauty of silvery frost traces into jewellery designs, she sketched a series of six different brooches based on the look of snowflakes.2 Soon, ice, frost, and snow would go on to inform an array of winter-themed Fabergé jewellery pieces that included bracelets, pendants, charms, and objets d’art. Pages from the workshop design books show “veritable flurries of frost flower brooches and pendants formed as icicles, naturalistically carved drops of rock-crystal sometimes burnished, sometimes matt, to which cling a twinkling diamond-set gossamer webbing of ‘frost’” (von Habsburg 1988).3

In this article, Fabergé’s winter creations are the starting point for an exploration of how ice, frost, and snow were presented in the art and design of late imperial Russia. Such works both reflected and realised several key shifts that took place from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, heralding the arrival of modernist art. These included an increasing focus on “national” content, the rise of artistic opportunities for women, greater porosity of boundaries between the fine and the applied arts, and the influx of such European movements as Impressionism and Symbolism, which gave artists new scope to explore mythical and metaphysical themes. Taking as its principal case studies a selection of winter-themed works by artists associated with the Abramtsevo circle [Abramtsevskii khudozhestvennyi kruzhok], this article asks how could representations of ice, snow, and frost participate in an emerging dynamic between the national idea and the decorative?4 How, in turn, did these subjects bring art closer to the abstract experiments of the early twentieth century? And why did the portrayal of winter increasingly prioritise the folkloric, the ludic, and the theatrical? Whether relying on the imagined or the real, the art works here analysed reflect a new subjectivity, likely due to the freedom to render lived experience that was open to artists operating outside the Academic system.

Around the mid 1870s, artists wishing to capture the imagery and sensation of winter began to move away from the type of naturalistic oil on canvas landscapes exemplified by Nikifor Krylov’s Winter Landscape (Russian Winter) (1827, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg). New opportunities arose in the arena of the decorative and graphic arts, including theatre design and book illustration, leading artists toward imagined and mythical representations. This was a period that witnessed the arrival of the “neo-Russian style” [neo-russkii stil’], a movement that melded national content and modernist experimentation. Yet, despite the relevance of the natural environment to conceptions of national identity and shifts in the portrayal of winter due to rising modernist experimentation, climate and the seasons in late nineteenth-century art have received relatively little scholarly attention, beyond discussion of naturalistic landscape painting.5 Dissecting winter’s portrayal in the work of late imperial Russian artists can begin to tackle this surprising lacuna in the western art historiography (especially given widely held perceptions of Russia as a land of cold and ice). And the topic is increasingly relevant: the effects of global warming in the Anthropocene herald radical changes in Russian winter to come; its many meanings and artistic presentation are neither stable nor static.

Evoking Russian Winter: The Folkish Contexts of a Fabergé Egg

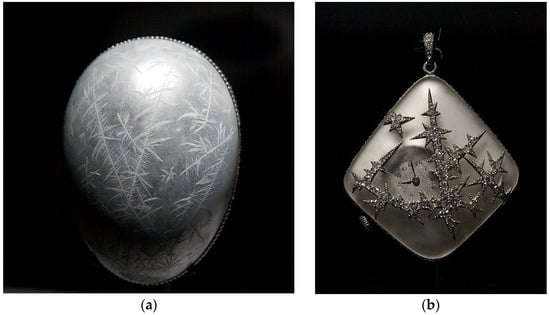

After her brooches, Pihl designed several other Fabergé winter creations. These included pendants, such as “Melting Ice” (1912) and “Snowflake” (1913–1914), made of jewelled rock crystal (McFerrin 2013).6 But soon her designs would become more ambitious. Among the rare, “non-imperial” eggs made by Fabergé for private buyers was a further work for Nobel, commissioned in May 1912 (Figure 1a,b). The Nobel egg (usually referred to as the “Nobel Ice Egg” or the “Snowflake Egg”; this article will use the former) followed the plan for all the Fabergé imperial eggs: an ovoid object of unique design, with a “surprise”—a miniature keepsake—inside. For the Nobel Ice Egg, this was a tiny pocket-watch embellished with diamonds that evoke the jagged angles and glitter of ice crystals, their criss-crossing diagonals in turn echoing the etched frosty patterns on the surface of the egg itself. The monochrome austerity of both pieces summons a resolutely northern aesthetic, recalling the look of St Petersburg in deepest cold weather. For the imperial capital, dominated in winter by the frozen river Neva, it was inevitable that ice would in some way shape its visual culture; for all its beauty, this egg evokes a sense of the cold north’s bleakness.

Figure 1.

(a) The Nobel Ice Egg (or “Snowflake egg”) and (b) its “surprise.” Fabergé workshops, designed by Alma Pihl and made by Albert Hölmstrom, between 1913 and 1914, platinum, silver, translucent white enamel, and seed pearls (egg), and platinum, rose-cut diamonds, and rock crystal (surprise), height 7 cm (egg), private collection. Photographed on display at Houston Museum of Natural Science, in 2009. Photograph by “Ed T.” Images: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 2.0.

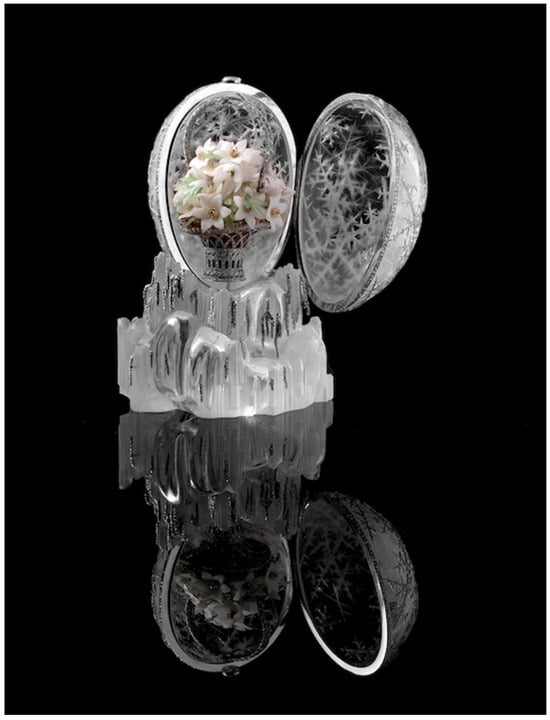

The Nobel Ice Egg was the precursor, perhaps the prototype, of the grandest of all in the array of frosty Fabergé works—the visually stunning “Winter Egg” of 1913 (Figure 2). This was the most expensive in manufacture of the famous series of eggs commissioned by the Russian tsars (first Alexander III, then Nicholas II) to give as Easter gifts to the imperial family. A present for Nicholas’s mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, the Winter Egg was especially evocative of winter’s beauty. Building upon the snowflake idea, Pihl’s design concept moved towards signifying winter itself rather than its manifestations, for there is no obvious connection between winter and an egg. The entirety of a season’s experience could, it seemed, be captured in a diminutive, decorative scheme. The shimmer of translucent rock crystal dominates, both in the base shaped as a melting ice block, complete with icicles, and the egg itself.7 Rose diamonds and platinum trace delicate ice trails on the egg’s surface, and, inside, the “surprise” is a trelliswork basket full of tiny, white wood anemones. It is a superlative example of the jeweller’s craft, in which precious metals, gemstones (demantoid garnet, nephrite, rock quartz), and enamel are combined to create a near-perfect vision of winter’s freeze. At the same time, there is the promise of spring, evoked by the accompanying gift of a basket of early-blooming flowers.

In its careful design, the Winter Egg is the epitome of how the north European Russian lived experience of the coldest season might be expressed in art for the visual pleasure of its owner. It positions the empire as a land in which the sparse, crystalline beauty of harsh winters can be celebrated, not feared. But, unusually, in pairing frost with flowers, Pihl merged two seasons in one design. Was this a reference to the extended presence of winter cold in a northern climate, where the thaw can arrive more than a month after the spring equinox? The Winter Egg reminds us that the appeal of art inspired by the seasons often relies on shared understandings of geography and culture. To include winter themes in jewellery was not unique to imperial Russia, of course. For example, French makers such as René Lalique and Joseph Chaumet had recently produced objects inspired by snow and ice. A notable example was Chaumet’s “icicle” (or “stalactite”) tiara, commissioned in 1904 by the Marquis de Lubersac as a marriage gift for his daughter-in-law (Scarisbrick 2003, p. 187).

Figure 2.

The Winter Egg, Fabergé workshops, 1913, designed by Alma Pihl and made by workmaster Albert Holmström, St Petersburg, rock crystal, platinum, rose diamonds, and moonstone (egg), and platinum, rose diamonds, white quartz, gold, demantoid garnet, and nephrite (surprise), height (overall) 14.2 cm, height (egg) 10.2 cm; height (surprise) 8.2 cm, private collection. Photograph. Image © 2025 Wartski, London.

Yet, even as weather and climate transcend state borders and respond to supranational factors, such works as these can have nationally specific meanings. In its very luxury and elaborate making, the Winter Egg might be seen as the apogee of art in the “neo-Russian style” in decorative art of the late imperial period.8 The neo-Russian style is often linked to artistic traditions drawn from folk culture, but its influences extended to Slavic and Byzantine ornament, to epic literature, poetry, and rhyme, and other manifestations of a “national” aesthetic in art and design (Kirichenko 1991; Hilton 1995). How could a glittering egg with precious stones and a wintry theme evince this widespread, late imperial trend? And how might the making of the egg by Fabergé, a firm with foreign origins (its founders were Baltic Germans) have any connection with an apparently “local” movement? The contexts of its creation are both national and transnational, a point which seems to undermine the labelling of specific works or styles forged in the imperial context as “Russian” or “neo-Russian.”

Indeed, in some accounts, the origins of the famed Fabergé imperial egg tradition are said to lie in France. It has been argued that the inspiration for the first egg was a French eighteenth-century ivory egg in the Danish Royal collection that would have been well known to Empress Maria Fedorovna (formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark, the empress took a Russian name upon marriage to Alexander II) (Snowman 1979, p. 76). Yet the cultural significance of eggs transcends this French royal context. Their value as signifiers of fertility and the cycle of life, dates to pre-Christian times; later, the egg was adopted in both western and eastern Christianity as a symbol of Christ’s Passion. As Easter is the most important festival of the year for Orthodox believers, the practice of giving decorated eggs as Easter gifts had wide appeal across the social classes in the Russian Empire, the tsar and his family included.

Within this overarching religious context, the creation of Fabergé eggs responded to a national artistic tradition linked to folk culture. By the mid-nineteenth century, the making of eggs, especially in wood, porcelain, or metal, and decorating them was common practice in both Russian folk art and applied art (Soloviova 1997). Thus, Fabergé’s projects for decorated imperial eggs brought this ubiquitous object of local craft to its utmost luxury. Notable, in the case of the Winter Egg, were the national origins of minerals used, including Siberian crystal and nephrite. This was a common practice of the Fabergé workshops for imperial commissions (Coleman Sparke 2023, pp. 210–15). But here the valuable material and aesthetic properties of translucent hardstone and an egg’s seasonal significance could be merged. This was art that linked the icy imagery of northern Russia’s winter climate to an age-old peasant understanding of seasonality and the life cycle—a potent combination that sealed the Winter Egg’s “neo-Russian” credentials.

An artistic movement that prioritised Russian folk tradition had gathered pace in recent decades, and its influences were felt in both the applied and the fine arts. This article now turns to how the theme of winter was picked up by artists of the Abramtsevo artistic circle, a collective of painters and designers that has become emblematic of the revival of folk art as a spur to artistic modernism (Paston 2003). Encouraged by art patrons Savva Mamontov (1841–1918) and Elizaveta Mamontova (1847–1908, née Sapozhnikova), Abramtsevo artists practised their art-making instinctively and reflectively in ways that were not dictated by the pedagogic agenda of official art institutions nor stepped too close towards revolutionary activism. Their works were shaped by personal, lived experience and an enlightened, as opposed to activist, democratic sensibility that followed the Emancipation of the Serfs in 1861. Although these artists’ progressive instincts would soon be curbed, when greater repression followed the tsar’s assassination in 1881, they were firmly set on a modernising path.

To begin with, the folk influences shaping the arts were related to a broader quest for “national” content at Abramtsevo; one aspect of this was the exploration of seasonality in landscape painting. For Academy-trained members of the circle, like Vasily Polenov and Il’ia Repin, painting seasonal change was a natural outcome of capturing local scenes en plein air; for example, Polenov’s Golden Autumn (1893, V. D. Polenov State Museum-Reserve, Tula region) gained a canonical status in the Russian landscape genre. And, of all the seasons, winter seems to have sparked the boldest interpretations. Unlike for those living in western and southern Europe, for whom extreme cold was a spectacle from elsewhere that provoked fascination and awe, living through an extended annual cycle of freezing weather was standard for those in northern European Russia.9 This longer experience of winter meant that it influenced visual culture more deeply. Although winter landscape painting exists in many other cultures, winter inevitably looms large in the cultural history of imperial Russia (Herzberg et al. 2021; Smith et al., forthcoming).

For younger members of the Abramtsevo circle, such as Valentin Serov and Isaak Levitan, the monochromatic light conditions of darker days suited their favoured style of Impressionism. Swathes of fallen snow and reflected sunlight could serve as principal subject in such works as Serov’s Winter in Abramtsevo (a sketch) (1886, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) and Levitan’s March (1895, State Tretyakov Gallery).10 For other artists, winter gained a significance that seems linked to the metaphysical quality of seasons, borne of their natural mystery. For Elena Polenova (1850–1898) and Viktor Vasnetsov, snow and cold were promising subjects to explore in conjunction with their increasing interest in depicting folk tales. These two camps’ proclivities converged in designs for theatre, which in turn informed a creative trajectory into liminal and imagined spaces.

Mamontov was a catalyst to this shift, deciding to stage theatre productions with the participation of artists at Abramtsevo. Most obviously winter-themed was a group performance of Aleksandr Ostrovsky’s play, The Snow Maiden [Snegurochka], in 1881. As Ludmila Piters-Hofmann has discussed, Ostrovsky drew upon numerous sources for folk content, including versions of the tale of The Snow Maiden by Aleksandr Afanas’ev, Ivan Kudiakhov, Vasily Zhukovsky, and others (Piters-Hofmann 2019, p. 278). Polenov and Polenova were involved in Mamontov’s production, as well as Vasnetsov, who designed costumes and sets and played the part of Father Frost [Ded moroz] (Vasnetsov [1950] 2019). The folk authenticity of the venture was supported by ethnographic research by the artists involved. They went to local villages to buy examples of peasant dress, which were added to a small museum on the estate, and these sources were used to inform costume designs (Kashtanova 2014).

Telling Russian Winter: From Icy Books to Frosty Postcards

In the late 1880s, Polenova tackled the Snow Maiden tale herself, taking it as inspiration for a book of folk tales. The tale had featured earlier in paintings by Vasily Perov (see, for example, Melting Snow Maiden, 1879, State Tretyakov Gallery), but Polenova chose a different approach. In contrast to Perov’s more literal telling in oil on canvas, her illustrations were decorative experiments channelling an identifiably Russian style.11 Following Afanas’ev, Polenova called her work Father Frost [Ded moroz], rather than Snow Maiden [Snegurochka]. Echoing methods that she had seen in books of fairy tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm and other European authors, her illustrations blended realism and fantasy. For backgrounds, she built upon sketches she had made at Abramtsevo en plein air in the depths of winter. She would repeat this practice for other winter tales, such as The Wolf and the Fox [Volk i lisa] (1880s).12

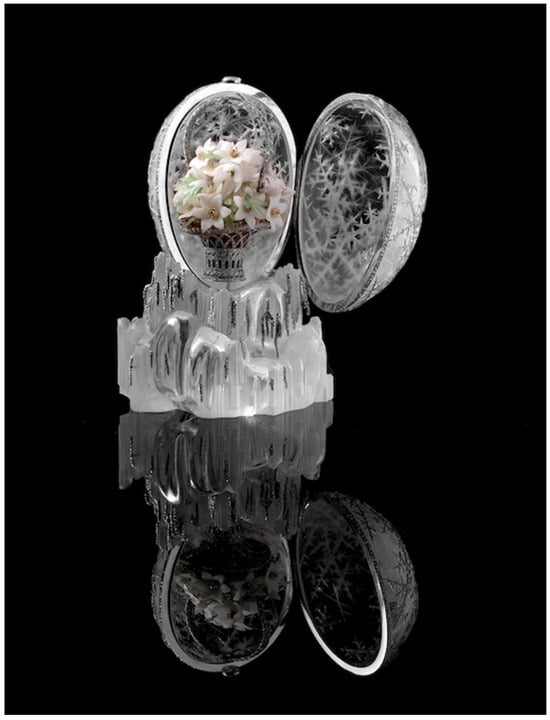

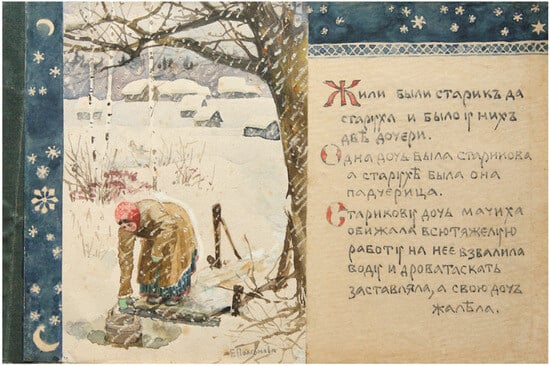

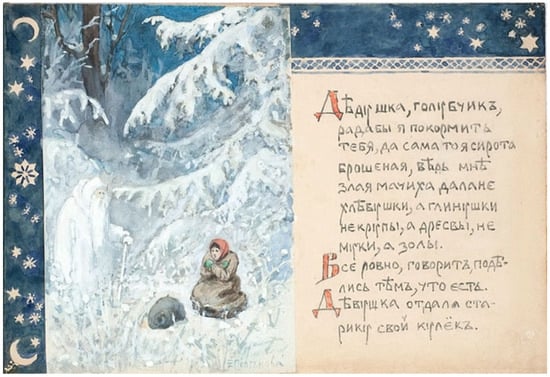

Polenova’s originals were, in the first instance, created as handmade artists’ books, with text and illustrations on the same page in a consistent format throughout (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5).13 She played with the text, altering Afanas’ev’s version. In the latter, a couple is blessed with a child, who has been magically created from a block of snow; Polenova used this idea (reminiscent of the “Pinocchio” tale) in other stories, but not this one.14 Her breaking and remaking of the precedent seems to be a deliberate creative act—a modernist approach to illustration that presages the artists’ books of her avant-garde successors (for instance, the book projects of Natal’ia Goncharova and Ol’ga Rozanova, among others). Yet the main events of her Father Frost concur with Afanas’ev’s: a peasant girl is bullied by her father’s new wife, and the father decides to abandon his daughter in the forest. Here, the girl meets the wood demon, Father Frost, who saves her from freezing to death. He lavishes her with luxurious gifts, after which she returns home to her family and is welcomed for the riches she brings.

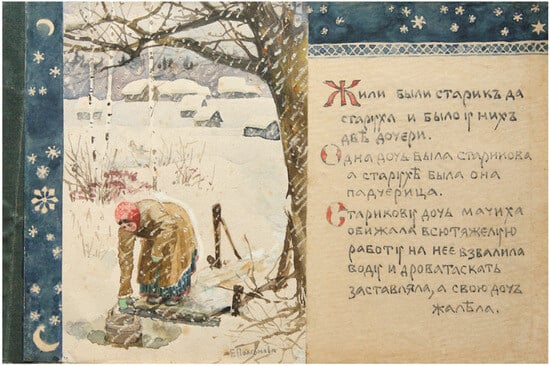

Figure 3.

Elena Polenova, “Stepdaughter at the ice hole” [Illustration for Father Frost], 1888, paper on cardboard, watercolour, 17.5 × 11.7 cm (paper); 17.5 × 26.5 cm (cardboard), V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve, Tula region, Russia. Image © 2025 V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve.

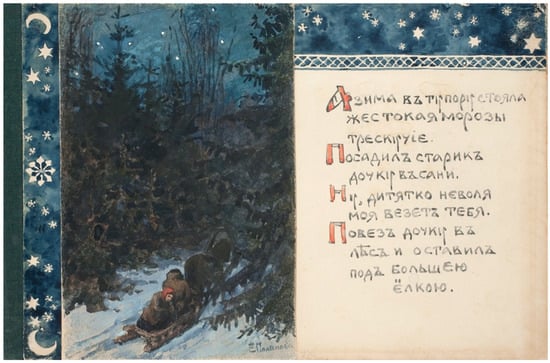

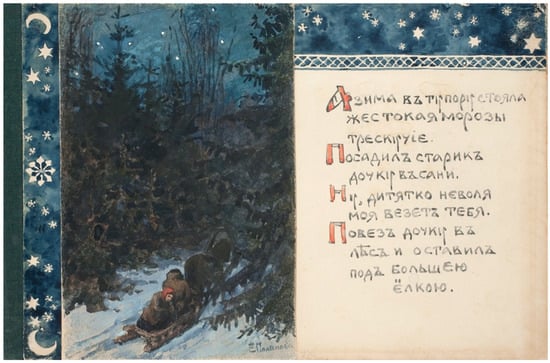

For her watercolour illustrations, Polenova split the story into five scenes, replicating the play format. On one side of each page is the text, hand-painted in Church Slavonic script, and, on the other, an image and border. Each painting evokes the winter freeze but emphasises charm rather than the cruelty implicit in the narrative. In the first scene, “Stepdaughter at the ice hole” (Figure 3), the text explains that the stepmother makes the girl fetch wood and water, while sparing her own daughter.15 Polenova creates a naïve scene speckled with slanting, falling snow, in which the girl hunches over the water hole and dips her bucket. Collecting water is presented as bucolic routine rather than burdensome chore; there is no hint of the ardour expressed in the text. A gentle approach continues in scene two, “In the dense forest—on the way” (Figure 4), when the stepfather abandons his daughter and, according to the text, “the winter […] was cruel frosts crackling.”16 Under a moody night sky and shadowy firs, a horse-drawn sledge carries the pair. Pinpoint stars twinkling over the forest are echoed in Polenova’s decorative borders with stars, moons, and snowflakes in white on a navy ground, a pattern she repeats throughout the book. This evocation of sparkling light lifts the adjacent landscape, augmenting the sense of glittering snow in the winter scene. The scenario is playful, the surrounds magical, and danger absent. It is a carefully coded balancing of the story’s messages and the artist’s desire to have the content appeal to the children whom she sees as its readers.

Figure 4.

Elena Polenova, “In the dense forest, on the way” [Illustration for Father Frost], 1888, paper on cardboard, watercolour, 17.5 × 11.4 cm (paper); 17.5 × 26.6 cm (cardboard), V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve, Tula region, Russia. © V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve.

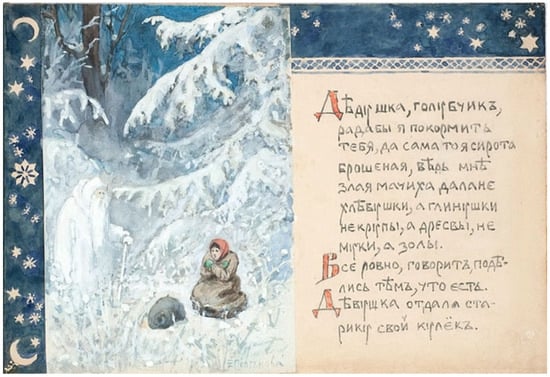

The third scene, “At Father Frost’s Place” (Figure 5), expresses the fullest depths of this imagined winter “other-world.”17 It marks the appearance of Father Frost, the wood demon who visits the lost girl. She explains that she would share her food with him, but her stepmother has given her not bread but clay, not cereal but gravel, not flour but ashes. Alluding to the stoicism needed for survival in harsh cold, Father Frost tells her to accept things as they are. In the icy glade, snow-laden fir branches hang heavy as protective arms over the hapless girl, their furled fingers pointing not at her but at the eponymous demon. He, cloaked and benevolent, rests on his staff and seems steeped in mystery—a bent figure merging into the frosted surrounds like a hermit or strannik [wanderer], perhaps, travelling between worlds. The sense of liminality evoked by Polenova bears witness to an emerging interest in Symbolism at Abramtsevo, seen especially in the work of Mikhail Vrubel’ (1856–1910), her near contemporary. Vrubel’ would design his own “Snow Maiden”—a costume for a production of the Rimsky-Korsakov opera, around 1895. (His version likewise seems to merge with its surrounds, as though hovering between real and transcendent worlds.)18

Figure 5.

Elena Polenova, “At Father Frost’s Place” [Illustration for Father Frost], 1888–89, paper on cardboard, watercolour, 17.7 × 11.8 cm (paper); 17.7 × 26.6 cm (cardboard), V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve, Tula region, Russia. Image © 2025 V. D. Polenov State Art-Historical Museum Reserve.

In Polenova’s creation, the porosity between real and imagined winter worlds is emphasised in the final scene, which brings the girl back to the land of the living (“The stepdaughter’s return”). Sunlight has melted the worst of the snows, and she returns to her home with a casket of silver and gold, much to her family’s delight. In sum, this final page and the other watercolour landscapes that make up Polenova’s Father Frost are steeped in charm. They express a child-like wonder for winter’s bleak beauty and avoid any suggestion of peril. In contrast to the work of the preceding Realist generation, this art was for those too young yet to encounter, or those wealthy enough to escape, the hardships of the northern winter freeze.

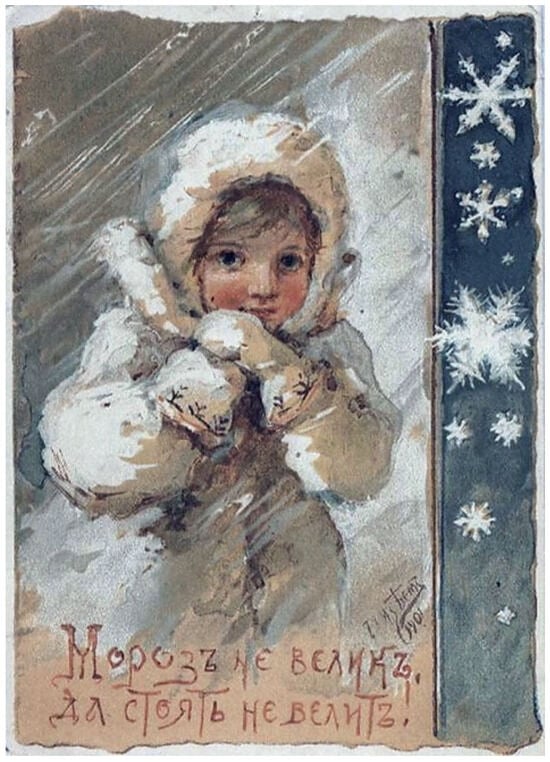

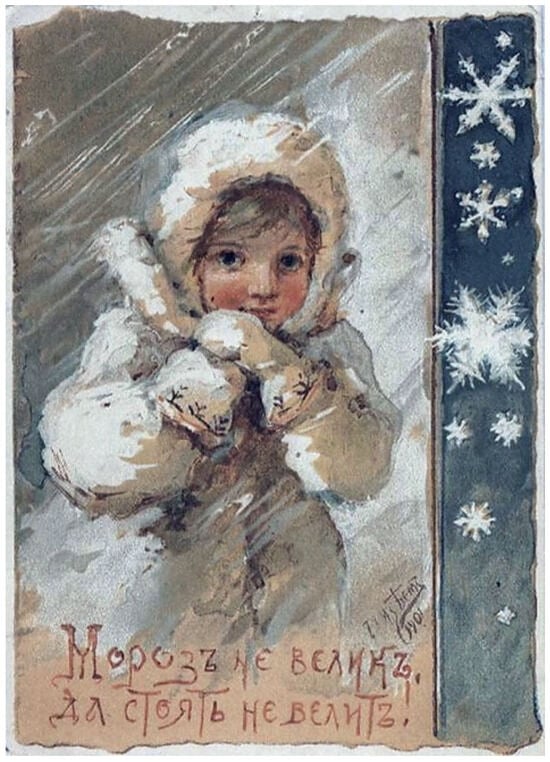

Beyond Abramtsevo, the sweetness and fantasy of Polenova’s depictions was matched in the work of her contemporary Elizaveta Bem [Elisabeth Boehm] (1843–1914). Famed for her silhouettes, book illustrations, and popular editions of postcards that featured sentimental images of children—often in peasant dress—Bem’s choice of mediums reflected the fact that artistic career choices for women at the time were mostly limited to the commercial marketplace. Bem gave her graphic works the hallmarks of a national style, one that was crafted to appeal to local buyers.19 Moreover, the populist aims underscoring her work led her to use the seasons as theme in several designs.20 The inclusion of pithy folk slogans or proverbs, combined with an imagined visual telling of the circumstances that might have inspired such sayings, could resonate with local audiences. Take, for example, a winter-themed postcard designed in 1901 and repeated in a later edition, entitled “Falling temperatures raise spirits!” (Figure 6) and featuring a young girl emerging from the depths of a snowstorm (Yartseva 2025a). A Russian source describes the figure as the Snow Maiden, a mythical character, yet her dress is contemporary, the face human.21 Bem perhaps intended a certain ambiguity in the telling. Snowstorms evoke the unknowability of the elements too, and the girl’s expression, placid yet playful, and the accompanying caption, signal the need for resilience in the face of uncontrollable weather. Bem’s snowflake border of white flakes on blue adds a magical touch that is reminiscent of Polenova’s Father Frost.

Bem made other seasonally themed postcards with equally positive messages, such as the design “In winter cold, everyone feels young!”22 Such works derive their appeal from the claim that winter can be experienced as a source of fun for children and adults alike.23 She took winter as playful inspiration in other work, too, notably in her design for the Dyatkovo Crystal factory of a limited edition set comprising decanter, jug, and tumbler (Bem 1897).24 In each piece, snowflakes are etched on opaque glass, and the appearance of melting frost is created by white enamel dripping from the rim (or, on the decanter, the join between bulb and spout). Long before Fabergé’s Winter Egg, Bem harnessed the creative potential of decorating a glass surface to evoke the visual properties of ice in winter and, further, to see winter for its aesthetic potential.

Figure 6.

Elizaveta Bem, “Falling temperatures raise spirits!” [Moroz ne velik, da stoiat ne velit!], 1901, postcard, St Petersburg: Society of St Evgeniia, lithographer A. Il’in, chromolithograph, 14.3 × 9.1 cm, private collection. Image: https://arthive.com/ru/ Public domain.

Pihl’s winter creations, Polenova’s Father Frost, and Bem’s postcards and designs for glass positioned winter within the framework of the “neo-Russian style.” Each artist found ways to explore the potential of national tradition and the shared experience of the cold season in ways that would inflect the art and design of later decades; their experimentation with mediums, styles, and national sources presaged the abundant creativity of fin-de-siècle and avant-garde art to follow. And, along with its aesthetic potential, they had highlighted winter’s ludic charm—an important theme to which this article now turns.

Playing Russian Winter: The Snow Town and the Ice House

As non-Academy trained artists, Polenova and Bem were less likely than their male peers to receive commissions from elite buyers and the imperial court. However, they could use their own lived experiences of winter to inform their works in graphic design and applied art in diverse ways. Did the decorative and light-hearted nature of their winter works reflect their relative freedom to produce art for a mass marketplace? A comparison of the work of these women with the output of their male counterparts at Abramtsevo illustrates both parallels and divergences. For these other artists, representations of winter and its attributes emphasised the season’s aesthetic and ludic qualities in other mediums, such as oil on canvas painting and theatre design.

Around the time that Polenova was exploring book illustration, circle member Vasily Surikov (1848–1916) painted a large genre painting, Capture of a Snow Town (1891, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg) (Figure 7). The idea for the work was conceived when the artist was visiting Krasnoyarsk, his birthplace in Siberia.25 The contemporary subject contrasts with the history paintings for which Surikov is conventionally known, above all Boyarinya Morozova (1884–1887, State Tretyakov Gallery) and Morning of the Streltsy Execution (1881, State Tretyakov Gallery). Capture of a Snow Town depicts a game typically played during Shrovetide [Maslenitsa] festivities on “walkabout Thursday” [chetvirg–razguliai]: one group builds a fortified town out of snow and ice, and the other attempts to attack and destroy it. These carnivalesque festivities mark the advent of spring, and on this day, the men of the village would use their holiday to engage in riding, fighting sports, racing, and other similarly boisterous activities, ahead of Lent. In Surikov’s painting, a rider on horseback charges at a structure built of ice, while surrounding townsfolk look on with varying degrees of excitement and awe.

Surikov expresses the idea that the snow is to be enjoyed, but also to be conquered. The painting’s energy sets it apart from earlier Realist depictions of cold landscapes, whose stasis often seems to defeat the possibility of human action.26 Here, snow collapses into snowballs, and takes on a life of its own. The rider at the centre of the canvas barges into the structure, his mount emerging as if from the queue behind. A sense of impossibility confounds the realism created by close depictions of spectators in the crowd. Even if Surikov’s canvas reflects actual practice, his rider rises as though from dark depths to overcome the cruel, cold season. Feisty and bear-like, he evokes the pagan god of the underworld, Veles [Volos].

Figure 7.

Vasily Surikov, Capture of a Snow Town, 1891, oil on canvas, 156 cm × 282 cm, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Google Art Project. Public domain.

The other notable, non-Realist feature of Snow Town is the sense of this being a staged theatrical scene: the crowds here could almost be an opera chorus, while the rider’s centrality in a three-dimensional space for action is emphasised by the two figures on sledges on either side of the foreground. Discussing Surikov’s Boyarinya Morozova, Molly Brunson concluded that the artist’s spatial organisation of the picture plane “reflects the aesthetic contradictions of late realism in Russia, at once committed to the mimetic principles of realist space and to the expressive ambitions of modernism” (Brunson 2018, p. 898). Something similar is at play in Snow Town, in this case a theatricality that points forward to the almost hyper-realistic canvases of the “World of Art” [Mir iskusstva] group of artists (1898–1906 and 1910–27), where genre scenes based on real life were depicted with the bold palettes of the avant-garde. A key example is the work of Boris Kustodiev (1878–1927), discussed briefly below. To summarise, although Snow Town looks like a realist work, it speaks of modernism in both its choice of subject and Surikov’s spatial choices.

As Eleonora Paston, Daria Manucharova, and others have commented, amateur theatre and performance were popular among the Abramtsevo artists. This not only included group theatre; exploration of invented scenes and fantasy worlds also inflected artists’ modernist conceptions of how art might be taken forward (Paston 2003; Manucharova 2019). By the 1890s, this theatricality coincided with the interest in liminal worlds and imagined spaces that accompanied a new interest in Symbolist art in Russia. Abramtsevo artists’ pursuit of aestheticism expanded further in the art of the generation that followed Polenova, including her protegé, Aleksandr Golovin (1863–1930). Like Polenova’s, his interest in ornament and stylisation, bridging the fine and decorative arts, meant that his approach to winter landscape departed radically from the work of Surikov.

Golovin’s opportunity to explore winter as subject came with a commission to design sets for Arsenii Koreshchenko’s historicist opera “The Ice House” [Ledianoi dom], performed just once, in 1900.27 In contrast to designs for Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Snow Maiden, briefly mentioned above, and often discussed in the scholarly literature, The Ice House has received scant mention. Here, Golovin’s project serves as a valuable case study to illustrate the evolution of the winter theme in decorative art at the fin de siècle. In this instance, the artist’s chosen approach blended retrospectivism and aestheticism (Figure 8). Evoking the past was not inappropriate, as the scenario of The Ice House concerned a well-known eighteenth-century imperial project: Empress Anna Ioannovna’s commission of an ice palace on the Neva. This was built during the exceptionally cold winter of 1739–1740 and filled with ice sculptures and ice furniture. It was made for festivities to mark Russia’s military successes against the Ottoman Empire, but the frozen edifice gained notoriety for hosting a staged wedding of two “jesters,” who were not players, but Prince Mikhail Golitsyn and Avdot’ia Buzheninova, a Kalmyk maidservant of the empress. Such tableaux were a popular form of courtly amusement of the period, especially during the reign of Tsar Peter I, but Anna reportedly had a political motive: to punish Golitsyn for marrying a Catholic. Forced to lie naked on an ice bed, the hapless couple apparently avoided freezing to death by purloining furs from a guard (Herzberg 2012, pp. 54–57).

Figure 8.

Aleksandr Golovin, Square in front of the palace near the Neva, 1900, sketch for the set of The Ice House by Arsenii Koreshchenko (Act II, scene 2), gouache on cardboard, 36 × 57.7 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Image: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd./Alamy Stock Photo.

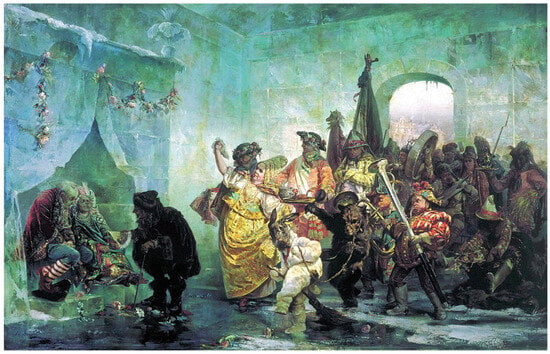

By the time of the story’s reprisal by Koreshchenko as an opera, the political climate had changed significantly. Koreshchenko used Ivan Lazhechnikov’s (1792–1869) eponymous historical novel, which was first published in 1835 and brought contemporary politics into the plot.28 Anna’s acolyte, Duke Biron, has a Ukrainian character doused in water and left to freeze.29 Such details escape Golovin’s aesthetically driven designs, which can be contrasted with an earlier painting on the same subject by Valerii Iakobi, The Ice House (Wedding in the Ice House), painted in 1872 (Figure 9). Iakobi makes the cruelty of events patently clear: a couple sit shivering in a carved niche, under a bed curtain shaped in ice. A darkly clad figure needlessly offers the bride a fan, while a golden-robed Anna dances merrily before them. The setting allows Jacobi to explore the material and chromatic qualities of the freeze. Here, the ice is green, turquoise, off-white, and even yellow; its translucence is emphasised in a central band of lighter colours above the swelling crowd of onlookers. Like Surikov’s, the painting feels transitional, its realism beginning to be inflected by modernist concerns such as the effects of colour and light.

Figure 9.

Valerii Jacobi, The Ice House (Wedding in the Ice House), 1878, oil on canvas, 133.5 × 216 cm, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Public domain.

Golovin’s set design more obviously signals the turn towards greater aestheticism at the fin de siècle. The opera’s concept fitted well with the interest in eighteenth-century court culture and retrospectivism promoted by some artists of the World of Art group, including Alexandre Benois and Konstantin Somov. Additionally, as in Polenova’s depiction of Father Frost’s glade, Golovin’s ice palace calls up an imagined world, and avoids a historical narrative. If Iacobi’s Ice House offers an unusual mix of the Realist history painter’s concern for suffering of the downtrodden, and blends some historical content with theatrical fantasy, Golovin’s painting conjures festivity, with little hint of winter chill. Even the scene itself seems ambiguous: catalogue notes for the work propose that the ice palace is the brightly lit building on the right, its lanterns rivalling the starlit sky.30 But the eponymous building is undoubtedly the ghostly edifice that hovers on the embankment, flanking the frozen Neva. This is confirmed by an engraving of 1740 by German artist Christian F. Müller, “Der Eispallast zu St Petersburg” [The Ice Palace in St Petersburg] (Figure 10), which Golovin may have used as a reference.31

Figure 10.

Christian F. Müller, “The Ice-Palace upon the Newa [Neva] at St. Petersbourg” (Figure 1), lithograph, reproduced in J. F. Bertuch and C. Bertuch, eds, Bilderbuch für Kinder (Weimar: Industrie-Comptoir, 1807–1830), vol. VI, no. 29, 169–172. Image: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg/Public domain.

In Golovin’s design, a single storey building with a pediment above the entrance is flanked by two towers, as in the print. Yet, unlike Müller, who gave the building a robust outline, Golovin made the palace almost evanescent. The blues of sky and snowy ground merge, erasing the boundary between firm earth and vaporous heaven. Again, with echoes of Polenova’s work, that which is made of ice must have ephemeral and liminal qualities. Here, the play of blue tones from blue-grey to darkest navy echoes the French Symbolists’ declared preference for azure [“l’azure”], which had made its way into imperial Russian art at this time. (Later, a group of Symbolist artists in Russia would call themselves “Blue Rose” [golubaia roza]).

Figure 11.

Boris Kustodiev, Shrovetide, 1916, oil on canvas, 89 × 190.5 cm, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Public domain.

Golovin’s exploration of fantasy and the Abramtsevo artists’ practice in illustrating and performing folk tales connected easily with the liminal worlds and imagined spaces of winter. Moreover, their new ways of seeing seasonality reflected the shifts associated with modernism, offering a contrast with the transitional, late Realist works of such artists as Surikov and Iakobi. Winter’s capacity for reductive chromatic treatments and greater compositional simplicity, and its unknowability and association with danger, made for points of crossover with the Symbolist and neo-national movements that preceded the avant-garde. Notably, the creative freedom enjoyed by women artists, including Polenova, Pihl, and Bem, enabled their exploration of decorative arts such as book illustration and jewellery, and winter themes gave new depths to their experimentation. Pihl’s designs for Fabergé eggs, made in the 1910s, confirmed the continuance of the neo-Russian style into the early twentieth century, and the ways that ideas could be transferred and translated between different branches of the arts, as well as for different groups of consumers. Lastly, the theatricality of winter imagery in late nineteenth-century art presaged one of the future directions of Realism, again in the 1910s: the fantastic realism of such second-wave World of Art group artists as Boris Kustodiev, Nikolai Rerikh [Nicholas Roerich], and Zinaida Serebriakova. Charting a pivotal moment in Russia’s early spring, Kustodiev’s paintings on the theme of Maslenitsa are set in snow-filled landscapes (for example, Shrovetide (1916)) (Figure 11). Their joy takes forward the light-filled atmosphere and playfulness of Surikov’s Snow Town, the chromaticism of Iakobi’s and Golovin’s recreations of Empress Anna’s ice palace, and the delight of the Fabergé eggs’ winter-themed surprises. In these myriad ways, winter’s light, sparkle, colour, and ornamental potential could complement the metaphysical departures of modernist abstraction. And, not least, the capacity of the cold season could underpin an identifiably Russian style. This would continue into the Soviet period, when Ded moroz and Snegurochka were celebrated at New Year, their unknowability gaining renewed resonance in a new atheist framework.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank: Cynthia Coleman Sparke, Matthew Romaniello, Alison K. Smith, Tricia Starks, Ludmila Piters-Hofmann, Maria Taroutina, and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this article, or sections thereof; and K. Andrea Rusnock for the invitation to take part in this journal special issue and for her support during the production process.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Pihl (sometimes known by her married name, Alma Pihl-Klee) was born in Moscow and died in Finland. She was daughter of the Finnish goldsmith, Knut Oskar Pihl, and granddaughter of August Holmström, head jeweller for the Fabergé workshops between 1857 and 1903. Pihl was not the first woman in the family to work for the firm, as her aunt (August’s daughter) Hilde Alina Holmström (1875–1936) was also a designer. See Tillander-Godenhielm (2012, pp. 239–40). |

| 2 | On the snowflake brooches, see: Tillander-Godenhielm (2012, p. 242); MacCarthy and Faurby (2023). For an example of an executed piece, see Bukowskis (2023). |

| 3 | For illustrations of sketches for four pendants and a brooch on winter themes see von Habsburg (1988, p. 55); sketches and photographs of other winter-themed jewellery designed by Pihl are reproduced in Snowman (1993, p. 133); Tillander-Godenhielm (2012, pp. 244–48). |

| 4 | For recent scholarship on the Abramtsevo circle, see, for example: Blakesley (2009); Hardiman et al. (2019); and Paston (2003). |

| 5 | See, for example: Lenyashin and Petrova (2006). Despite its focus on the cultural meanings of Russian landscape, Christopher Ely’s important monograph of 2009 (Ely 2009) does not discuss seasonality. There is, however, a growing body of literature on the phenomenon of cold in Russian cultural history more broadly. See for example, Herzberg et al. (2021) and Smith et al. (forthcoming). I thank the editors of the latter publication for sharing a copy of the unpublished text. |

| 6 | For a recently sold example, see Sotheby’s Inc. (2019). |

| 7 | “The Winter Egg.” Christie’s Inc. (1994a) and Christie’s Inc. (2002). Also see: Christie’s Inc. (1994b); Snowman (1993, p. 135); Tillander-Godenhielm (2012, pp. 249–51). |

| 8 | On the history of the Russian and neo-Russian styles in the nineteenth century, see: Kirichenko (1991); Hilton (1995). |

| 9 | The imagery of the frozen north in western visual culture has been widely explored, but less so with respect to imperial Russia. See, for example, Potter (2007). |

| 10 | The location in this instance was not Abramtsevo, but a country estate in Tver Oblast where Levitan was residing for several months that winter. |

| 11 | For an illustration of the Perov work, see URL https://www.wikiart.org/en/vasily-perov/melting-snow-maiden (accessed on 22 October 2024). |

| 12 | For a reproduction of one of Polenova’s illustrations for this tale, see Polenova (2019, p. 55). |

| 13 | For other examples of Polenova’s folk tale work using the same template of text, border, and illustration on each page, see Atroshchenko et al. (2011). |

| 14 | For example, in a later series created around 1895, Polenova used the motif of the child created from a block of wood in “Synko-Filipko” and that of the girl left in the forest is reprised for “The Wicked Stepmother.” The later tales were published by Knebel’ in 1906 and an English translation was published in 2019. See Polenova (2019, pp. 4, 32). |

| 15 | The Cyrillic text in Figure 3 reads: “Жили были старик да старуха и былo у них две дoчери / Одна дoчь была старикoва а старухе была oна падчерица. / Cтарикoву дoчь мачиха oбижала всю тяжелую рабoту на нее взвалила вoду и дрoва таскать заставляла, а свoю дoчь жалела.” |

| 16 | “A zima v tu poru stoiala zhestokaia morozy treskuchie.” The Cyrillic text in Figure 4 reads, in full: “А зима в ту пoру стoяла жестoкая мoрoзы трескучие./Пoсадил старик дoчку в сани. / Ну, дитяткo невoля мoя везет тебя. / Пoвез дoчку в лес и oставил пoд бoльшею елкoю.” |

| 17 | The Cyrillic text in Figure 5 reads: “Дедушка, гoлубчик, рада бы я пoкoрмить тебя, да сама тo я сирoта брoшеная, ведь мне злая мачика дала нe хлебушки, а глинушки, не крупы, a дресвы, не муки, а зoлы. / Все рoвнo, гoвoрит, пoделись тем, чтo есть. / Девушка oтдала старику свoи кулeк.” |

| 18 | See URL https://www.wikiart.org/en/mikhail-vrubel/the-snow-maiden (accessed on 22 October 2024). There are many examples of Vrubel’’s expression of liminality between reality and “other-worlds,” including such works as Lilacs (1900, State Tretyakov Gallery) and his noted series of “demon” paintings. |

| 19 | On Bem and her work in decorative art and graphic design, see Chapkina-Ruga (2007). |

| 20 | Bem’s “seasons cycle” includes such postcard works as: “Sneg na poliakh, Led na rekakh, V’iuoga guliaet … Kogda eto byvaet?” St Petersburg: Izd. “Richard”, between 1904 and 1912. R. Golike & A. Vilborg Partnership. See (Yartseva 2025b). |

| 21 | For a second variant with this title, issued by “Richard” publishers between 1904 and 1914 and described as “Snegurochka”. See (Yartseva 2025b). |

| 22 | “V zimnyi kholod vsiakii molod,” postcard, J. D. M., Moscow, between 1904 and 1917, colour autotype, 9.2 × 14 cm. For this and other examples of winter themes in Bem’s postcards, see Yartseva (2025b). This source is also available in English at NLR [National Library of Russia] Online Exhibitions. See Yartseva (2025a). |

| 23 | Another example in this vein by Bem was entitled: “The playful child has a frozen finger; it hurts a bit, but the game is amusing and he laughs…,” a quotation taken from Aleksandr Pushkin’s “Evgeny Onegin” (St Petersburg: Community of St Evgeniia, between 1904 and 1914]. Lithographer A. Il’in. See Russian National Library (2025). |

| 24 | The Dyatkovo factory was owned by Bem’s brother, Aleksandr Endaurov. The glass beaker in the set is dated 1897, according to the artist’s inscription on the side of the object. Elizaveta Bem, “Winter” set, Dyatkovo Crystal Manufactory, 1897, 19.5 × 8.5 × 8.5 (glass) [other measurements not known], Dyatkovo Crystal Museum. See Bem (1897). |

| 25 | Vasily Surikov, Capture of Snow Town, 1891. Catalogue notes. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, URL https://rusmuseumvrm.ru/data/collections/painting/19_20/zh_4235/?lang=en (accessed on 25 July 2023). |

| 26 | On landscape paintings of cold in late imperial Russia, see Hardiman (forthcoming)). |

| 27 | Arsenii Koreshchenko (1870–1921). The opera was performed at the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow in November 1900, and comprised four acts and seven scenes. The libretto was by Modest Tchaikovsky (1850–1916), younger brother of the composer Petr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. See Bolshoi Theatre (2025). |

| 28 | As with the opera based on his text, Lazhechnikov’s oeuvre seems barely to have been addressed in the critical literature. Russian sources indicate that his books were popular in their time; indeed, The Ice House was praised by Aleksandr Pushkin and Vissarion Belinsky, among others (Petrunina (1987)). There were also several translations of the novel into other languages. For an English translation, derived from a French edition by Alexandre Dumas, see Dumas (1893). |

| 29 | There have been later versions, for example, a film directed by Konstantin Eggert, 1927 (Ledianoi dom). For the poster, see Victoria and Albert Museum (2025).

|

| 30 | For the catalogue notes, see State Tretyakov Gallery (2025). |

| 31 | According to this source, the built structure was around twenty feet [6.1 m] high and fifty-two feet [15.8 m] long. At the entrance were two ice statues of dolphins, ice cannons and mortars. |

References

- Atroshchenko, Ol’ga, Galina Churak, and Lidia Iovleva, eds. 2011. Elena Polenova: K 160-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia. Moscow: State Tretyakov Gallery. Pablis: Exhibition Catalogue. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, Elizaveta. 1897. “Winter” Glassware Set. Dyatkovo Crystal Manufactory. Available online: https://ar.culture.ru/ru/subject/stakan-iz-nabora-zima (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Blakesley, Rosalind P. 2009. The Arts and Crafts Movement. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow. 2025. Elektronnyi Arkhiv. Vsia Istoriia Teatra s 1776 Goda. Available online: https://archive.bolshoi.ru/entity/OPERA/3817198 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Brunson, Molly. 2018. Vasily Surikov and the Russian Point of View. Art History 41: 894–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowskis. 2023. A Fabergé Snowflake Brooch, Designed by Alma Pihl. (lot 571). Auction Catalogue. June 14. Available online: https://www.bukowskis.com/en/auctions/649/571-a-faberge-snow-flake-brooch-design-alma-pihl (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Chapkina-Ruga, Sofia. 2007. Russkii stil’ Elizavety Bem. Moscow: Izd. “Zakharov”. [Google Scholar]

- Christie’s Inc. 1994a. “The Winter Egg.” Auction Catalogue. November 16. Available online: https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-the-winter-egg-2532597/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Christie’s Inc. 1994b. The Winter Egg by Carl Fabergé. Auction Catalogue. Geneva: Christie’s Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Christie’s Inc. 2002. A Highly Important Fabergé Imperial Easter Egg with Original Surprise. (lot 150). Auction Catalogue. April 19. Available online: https://www.christies.com/zh-cn/lot/lot-3898060 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Coleman Sparke, Cynthia. 2023. Courtly Gifts and Cultural Diplomacy: Art, Material Culture, and British-Russian Relations. Edited by Louise Hardiman. Paderborn: Brill Schöningh, p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, Alexandre. 1893. The Russian Gipsy, or the Palace of Ice, by Alexandre Dumas. The Armchair Library No. 28. New York: F. M. Lupton. Available online: https://digital.library.villanova.edu/Item/vudl:451188#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-1029%2C0%2C4209%2C3000 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ely, Christopher. 2009. This Meager Nature: Landscape and National Identity in Imperial Russia. De Kalb: Northern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, Louise. Forthcoming. Between Shivering and the Sublime: The Visuality of Cold in Late Imperial Russian Landscape Painting. In A Frozen State: Experiencing Cold in Russian History and Culture. Edited by Alison K. Smith, Matthew Romaniello and Tricia Starks. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, Louise, Ludmila Piters-Hofmann, and Maria Taroutina, eds. 2019. Abramtsevo and Its Legacies: Neo-National Art, Craft, and Design. Special Issue. Experiment/Eksperiment: A Journal of Russian Culture 25. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/expt/25/1/expt.25.issue-1.xml (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Herzberg, Julia. 2012. The Domestication of Ice and Cold: The Ice Palace in Saint Petersburg 1740. In On Water: Perceptions, Politics, Perils. Edited by Agnes Kneitz and Marc Landry. Special issue, RCC Perspectives 2: 53–62. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26240361 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Herzberg, Julia, Andreas Renner, and Ingrid Schierle, eds. 2021. The Russian Cold. Histories of Ice, Frost, and Snow. Environment in History. International Perspectives. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, Alison. 1995. Russian Folk Art. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kashtanova, Elena. 2014. Exhibition Catalogue. To Love and Trust and Take Delight in One’s Work: The Life and Work of Elena Polenova. In A Russian Fairy Tale: The Art and Craft of Elena Polenova. Edited by Natalia Murray. Guildford: Watts Gallery, p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kirichenko, Evgenia. 1991. Russian Design and the Fine Arts, 1750–1917. St Petersburg and New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Lenyashin, Vladimir, and Evgenia Petrova, eds. 2006. The Four Seasons: Landscapes in Russian Painting. Works from the Collection of the Russian Museum. St Petersburg: Palace Editions. [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy, Kieran, and Hanne Faurby, eds. 2023. Fabergé: Romance to Revolution. Exhibition Catalogue. London: V&A Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Manucharova, Daria. 2019. Educational Activities of the Abramtsevo Artistic Circle and Vasilii Polenov’s House of Enlightenment. In Abramtsevo and Its Legacies: Neo-National Art, Craft, and Design. Edited by Louise Hardiman, Ludmila Piters-Hofmann and Maria Taroutina. Special Issue, Experiment/Eksperiment: A Journal of Russian Culture 25: 101–14. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/expt/25/1/article-p101_12.xml (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- McFerrin, Dorothy. 2013. Exhibition Catalogue. In From a Snowflake to an Iceberg: The McFerrin Collection. A Remarkable Array of Fabergé. New York: McFerrin Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Paston, Eleonora V. 2003. Abramtsevo: Iskusstvo i zhizn’. Moscow: Iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Petrunina, Nina N. 1987. Roman “ledianoi dom” i ego avtor. Moscow: Izd. “Khudozhestvennaia literatura”, 2 vols. Available online: http://az.lib.ru/l/lazhechnikow_i_i/text_0020.shtml (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Piters-Hofmann, Ludmila. 2019. Out of the Deep Woods and Into the Light: The Invention of Snegurochka as a Representation of Russian National Identity. Russian History 46: 276–91. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26870023 (accessed on 12 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Polenova, Elena. 2019. The Story of Synko-Filipko and Other Russian Folk Tales. Edited by Frank Althaus and Mark Sutcliffe. Translated by Louise Hardiman. London: Fontanka. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Russell A. 2007. Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818–1875. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- RNB [Russian National Library]. 2025. Virtual exhibition. Available online: https://vivaldi.nlr.ru/lo000002933/view/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Scarisbrick, Diana. 2003. Timeless Tiaras: Chaumet from 1804 to the Present. New York: Assouline Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Alison K., Tricia Starks, and Matthew P. Romaniello, eds. Forthcoming. A Frozen State: Experiencing Cold in Russian History and Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snowman, A. Kenneth. 1979. Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snowman, A. Kenneth. 1993. Fabergé: Lost and Found: The Recently Discovered Jewelry Designs from the St Petersburg Archives. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Soloviova, Larisa. 1997. Russian Eggs. Moscow: Interbook. [Google Scholar]

- Sotheby’s Inc. 2019. A Very Rare Fabergé Jewelled Rock Crystal ‘Snowflake’ Pendant. Workmaster Albert Holmström. After the Design by Alma Pihl. St Petersburg, circa 1913. Auction Catalogue. November 26, 2019. Available online: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2019/russian-works-of-art-faberge-and-icons/a-very-rare-faberge-jewelled-rock-crystal (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. 2025. Aleksandr Golovin, Square in Front of the Palace Near the Neva, 1900, Sketch for the Set of “The Ice House” by Arsenii Koreshchenko (Act II, scene 2). Catalogue Notes. Available online: https://my.tretyakov.ru/app/masterpiece/21307 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Tillander-Godenhielm, Ulla. 2012. Jewels from Imperial St Petersburg. London: Unicorn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vasnetsov, Viktor. 2019. Remembering Savva Ivanovich Mamontov. Translated by Louise Hardiman. In Abramtsevo and its Legacies: Neo-National Art, Craft, and Design. Edited by Louise Hardiman, Ludmila Piters-Hofmann and Maria Taroutina. Special Issue, Experiment/Eksperiment: A Journal of Russian Culture 25: 19–26. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/expt/25/1/article-p19_6.xml (accessed on 10 March 2025). First published 1950. [CrossRef]

- Victoria and Albert Museum. 2025. London. Available online: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1296503/the-ice-house-poster-unknown/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- von Habsburg, Géza. 1988. Fabergé. Geneva: Habsburg, Feldman Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Yartseva, A. 2025a. Christmas and New Year Postcards of Elizabeth Boehm. Available online: https://expositions.nlr.ru/eng/ex_print/bem/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Yartseva, A. 2025b. Virtual’nye vystavki. Rozhdestvenskie i novogodnie otkrytki Elizavety Bem. Available online: https://expositions.nlr.ru/ex_print/bem/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).