Saltatory Spectacles: (Pre)Colonialism, Travel, and Ancestral Lyric in the Middle Ages and Raymonda

Abstract

1. Introduction

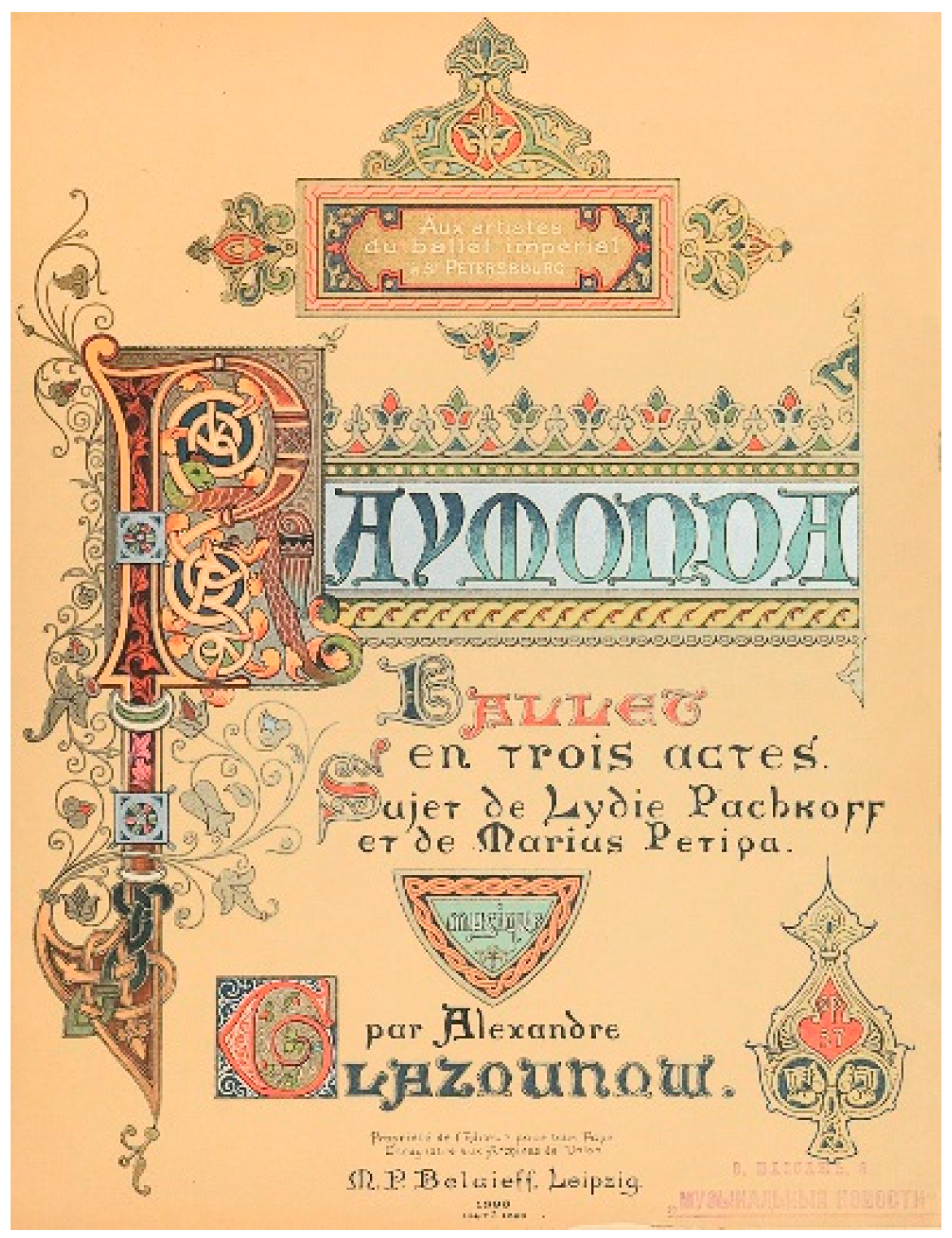

2. Raymonda (1898): Synopsis and Mis-en-Scène

3. Tracing Colonial Contours: Medieval and Modern

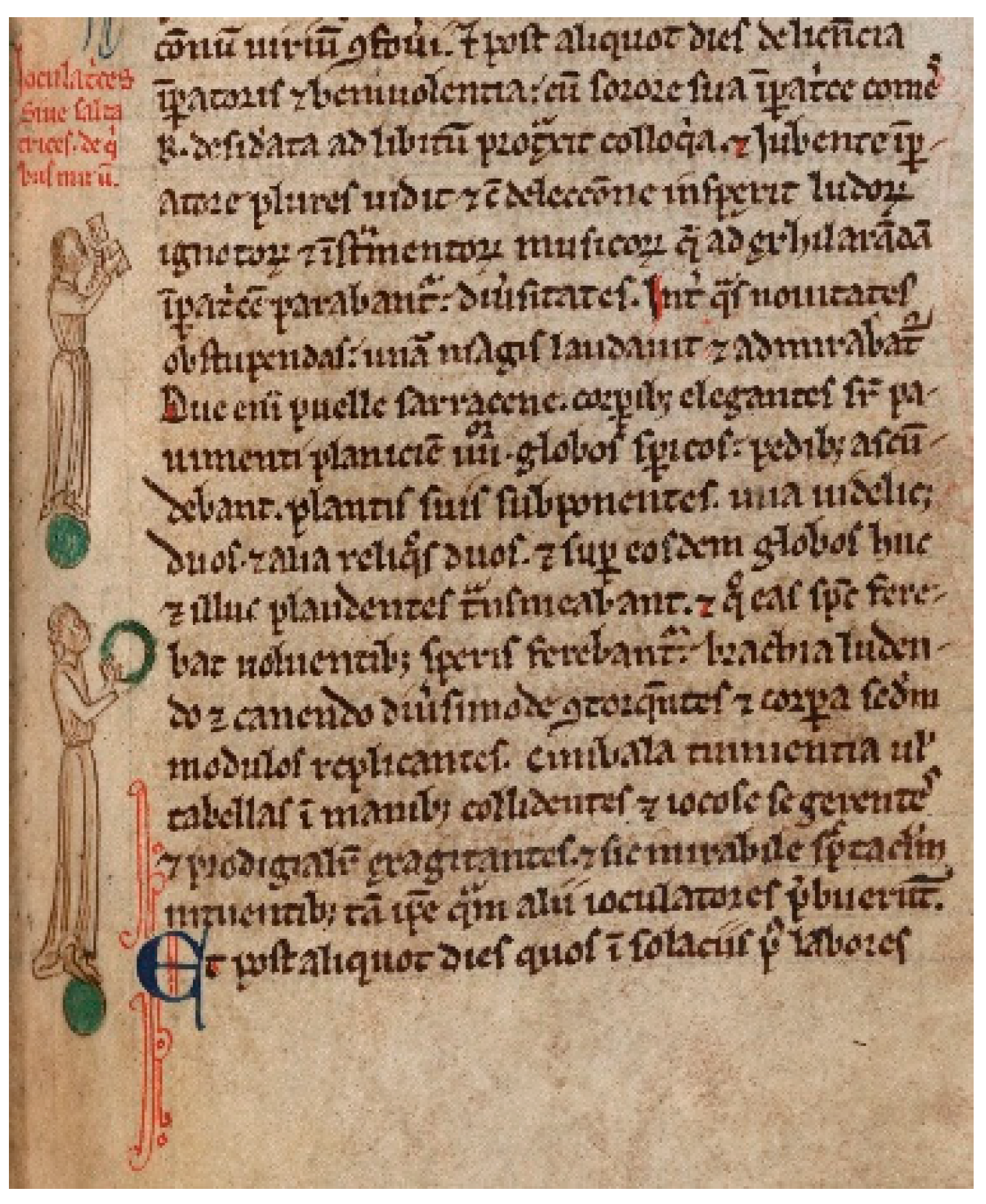

Duae enim puellae Sarracinae, corporibus elegantes, super pavimenti planiciem quatuor globos sphericos pedibus ascendebant, plantis suis subponentes, una videlicet duos, et al.ia reliquos duos, et super eosdem globos huc et illuc plaudentes transmeabant; et quo eas spiritus ferebat, volventibus spheris ferebantur, brachia ludendo et canendo diversimonde contorquentes, et corpora secundum modulos replicantes, cimbala tinnientia vel tabellas in manibus collidentes et jocose se gerentes et prodigaliter exagitantes. Et sic mirabile spectaculum ituentibus tam ipsae quam alii joculatores praebuerunt.[Two Saracen [sic] girls of fine form stood upon four spheres placed upon the floor, one on two balls and the other on the other two, and they danced across the spheres to and fro; and in a festive spirit they gesticulated with their arms, singing in various contorted ways, and twisting their bodies according to the tune, beating cymbals or castanets together with their hands, and prodigiously twirling themselves around in fun. And indeed they afforded a marvelous spectacle to those watching, as did other jongleurs].(Paris 1877, 6:147; trans. Lewis 1987, pp. 280–81)

Ballet [particularly during the reign of King Louis XIV] arose in Europe during times of colonialism and empire building by Europeans in what is now the Americas, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Africa, lands around the Persian Gulf, and more. Conquered peoples were seen (always from a European perspective) as fascinating (exotic) as well as objects of scorn—supposed encounters with them or their cultures on the stage being occasions to feel titillated, morally superior, and complacent about the enslavement and exploitation of “natives” by their governments.

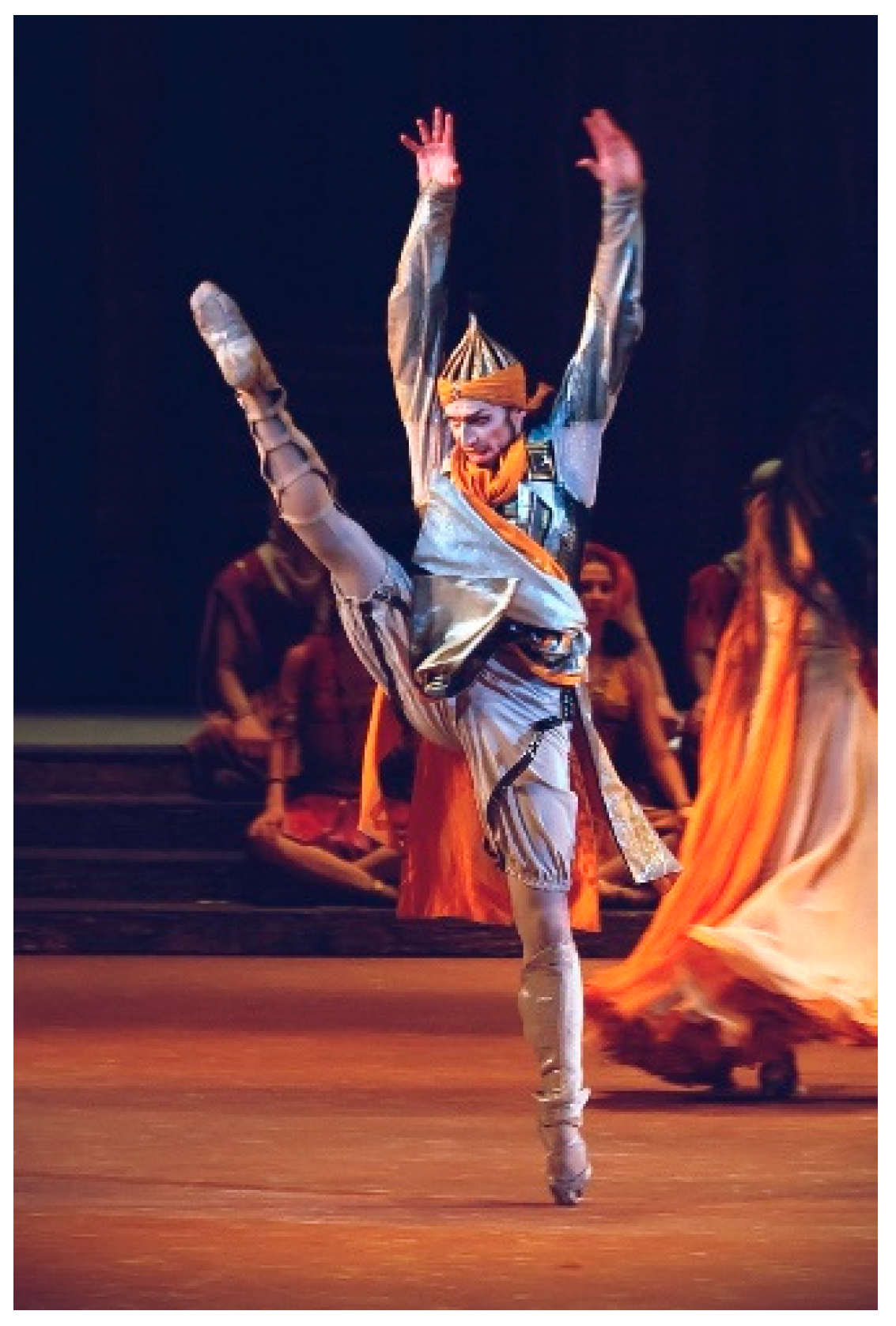

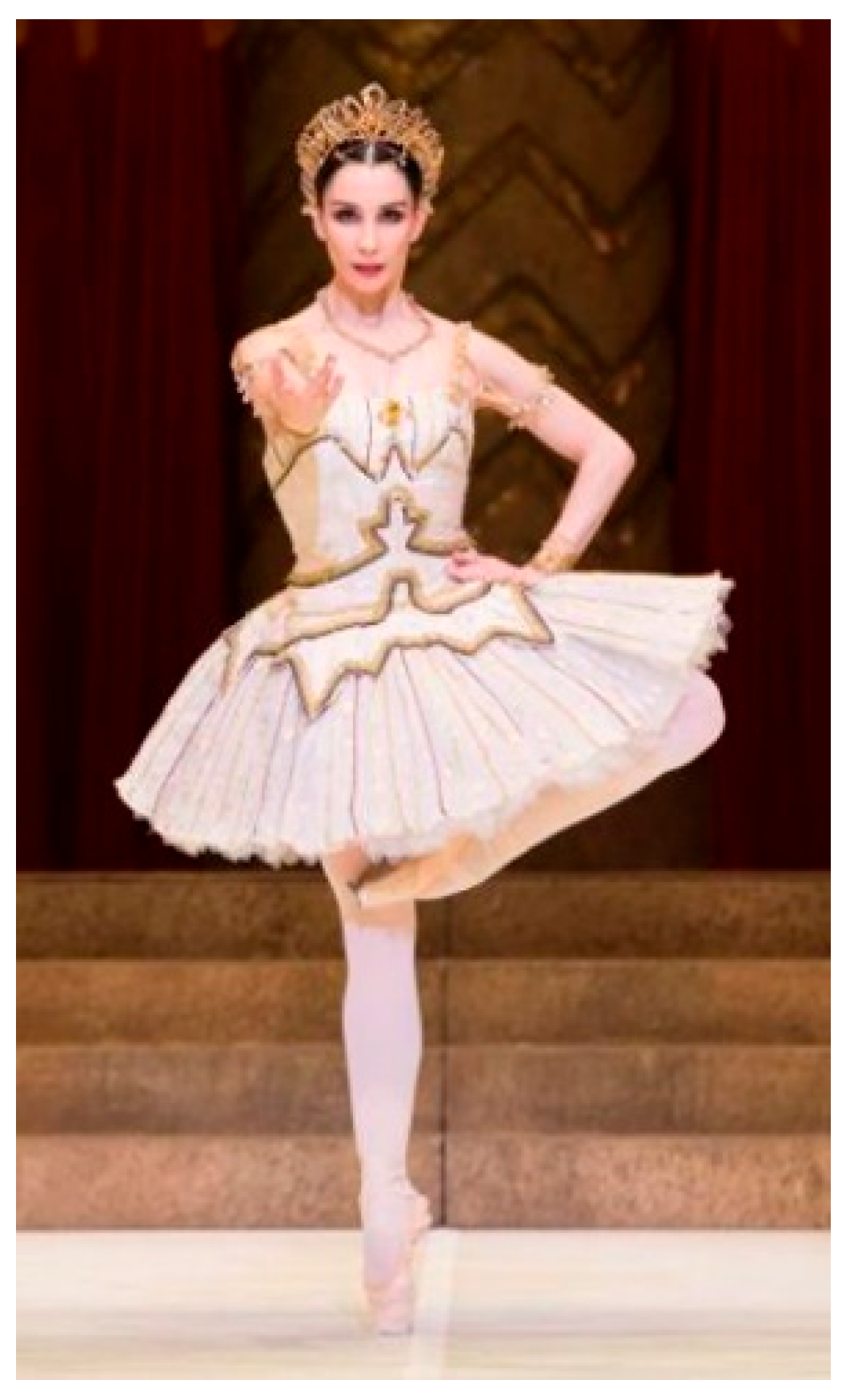

In Raymonda’s case there were political as well as sexual overtones to the [military] encounter. Where Jean de Brienne embodied Christian idealism, Abderrakhman represented the disruptive Eurasian other: rivals in love, they contended for sovereignty over Raymonda’s Western domain. In Raymonda, the last of several Mariinsky ballets of the 1890s set in a royal court, the threat of dynastic instability arises not from the presence of moral evil (as in The Sleeping Beauty) but from the aggressive action of a political and sexual outsider.

Travel writers like Polo were astonished by this empire’s wealth and enormity, though they intermittently critique Mongols’ supposed idolatry and heathenism. Travel writers’ depictions of Asian dancers suggest that European onlookers/readers enjoyed seeing these performers as servile, sexually available, and docile—not unlike colonized subjects. While these texts do not describe or record deliberate acts of colonial domination, they conjure proto-orientalist fantasies of consumption and exploitation.

4. Recreating Raymonda

I personally never liked the story [of Raymonda]; it was convoluted, it was complicated, and I didn’t quite get it. It didn’t make enough sense. And in today’s [multicultural] world, to imagine that somebody from another religion comes and is “the bad guy” [is controversial]. In 1898, people didn’t travel around [like we do today], they didn’t have internet, they didn’t know how the rest of the world is. So, if everything was portrayed in a really extreme caricature [back then, it has become unacceptable today] … So, I wanted to tell the story, but in a much more abstract [way] … We have not treated Raymonda well enough [i.e., stripping it down to variations without narrative has not done justice to this monumental work]. There are not enough of these key cornerstone classical ballets. Our repertoire is not as rich as opera repertoire. So, it is very important that we do the things that we choose to do really well … [Since our Boston Ballet dancers have mastered neoclassical and contemporary repertoire] now is the time to emphasize academic classical ballet … Because they are the generation that will take our art form and pass it onto the following generation.

5. Songs of Love and War: The Troubadours

Reys Frederics, vos etz frugz de joven,e frug de pretz, e frug de conoyssensa,e si manjatz del frug de penedensa,feniretz be lo bon comensamen.[King Frederick, you are the fruit of youth [courtly qualities], and fruit of merit, and fruit of learning, and if you eat of the fruit of penitence, you will end well the good beginning].(Guillem Figueira, cited and trans. in Paterson 2018, pp. 130–31)

A l’emperador man,pos valors renovella,qe mov’ab esfortz grancontra la gen fradellaez haia en Dieus son cor,qe Sarrazi e Morhan tengut li destrettrop lonjamenla terra on Dieus nasqete·l monumen,e taing be qe per lui cobrat sia.[I send word to the Emperor, since valor is reviving, that he should move witha great army against the race of villains and have God in his heart, for Saracens [sic] and Moors [sic] have too long held sway over the sepulcher and the land where God was born, and it is right that they should be recovered for him].(Falquet de Romans, cited and trans. in Paterson 2018, p. 140).61

These specifically lyrical articulations are crucial for understanding the crusades as a complex cultural and historical phenomenon… In a period during which the church imagined the need to recover the Holy Land as inseparable from the individual and collective moral reform of its believers, the crusader subject of vernacular literature and media sought to reconcile competing ideals of earthly love and chivalry with crusade as a penitential pilgrimage.

Aler m’estuet la u je trairai paine,En cele terre ou Diex fu travelliés;Mainte pensee i averai grevaine,Quant je serai de ma dame eslongiés;Et saciés bien ja mais ne serai liésDusc’a l’eure que l’averai prochaine.Dame, merci! Quant serai repairiés,Pour Dieu vos proi prenge vos en pitiez.Douce dame, contesse et chastelaineDe tout valoir, cui sevrance m’est griés,Si est de vos com est de la seraineQui par son chant a pluisors engigniés;N’en sevent mot, ses a si aprociésQue ses dous cans lor navie mal maine;Ne se gardent, ses a en mer plongiés;Et s’il vos plaist, ensi sui perelliés.En peril sui, se pités ne m’aïe;Mais, se ses cuers resamble ses dous oex,Donc sai de voir que n’i perirai mie:Esperance ai qu’ele l’ait mout piteus.Sovent recort, quant od li ere seus,Qu’ele disoit; “Mous seroi esjoïe,Se repariés; je vos ferai joiex;Or soiés vrais conme fins amourex.”Ha! Diex, dame, cist mos me rent la vie;Biaus sire Diex, com il est precieus!Sans cuer m’en vois el regne de Surie:Od vos remaint, c’est ses plus dous osteus.Dame vaillans, conment vivra cors seus?Se le vostre ai od moi en compaignie,Adès iere plus joians et plus preus.Del vostre cuer serai chevalereus.[I must go there where I will endure sufferingIn that land where God was tortured;I will have many heavy thoughtsbecause I will be away from my lady;And know well that I will never be happyUntil the time I will have her close to me.Lady, have mercy! When I will have returned,I beg you by God that pity takes you…Ah! God, lady, these words restore life to me;Good lord God, how they are precious!Without a heart, I go away to the kingdom of Syria:With you it remains, its sweetest refuge.Worthy lady, how will a body live without a heart?If I have your heart with me in company,I will be the most joyful and brave.By your heart, I will be valiant].(Châtelain d’Arras, cited and trans. in Galvez 2020, pp. 35–37)

6. Re-Centering Feminine Lyric Voices: La Dame Blanche and the Qiyān

were meant wholly to be enjoyed, and sung along with, even danced to, rather than just listened to and admired with detached connoisseurship … this kind of song made rhyme an encircling device, repeating rhyme patterns of sometimes dizzying complexity, with internal rhymes as well as those linking one stanza to another.

7. Conclusions

As a method, instead of a framework, for engaging the past, the global Middle Ages sets us, and that which we study, into constant motion. More so than attempt to encompass the world, the global Middle Ages should make available the notion of spacetime in our historical analysis, which ultimately moves us beyond the global, seeking stability not in a stationary foot but in the ever-shifting relations between.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the scope of this article, I cannot provide an in-depth examination of medievalism within Raymonda’s choreography, though Chaganti offers an illuminating interpretation of Raymonda’s solo variation from Act III (Chaganti 2011, esp. 157). Fullington and Smith provide an impressive in-depth analysis of the entire ballet based on extant choreographic notation (Fullington and Smith 2024, pp. 622–63; Fullington 2022, pp. 259–342). For more on ballet medievalism, see (Richard 2007). |

| 2 | When interpreting medieval textual and visual sources, I am indebted to Cord Whitaker’s concept of “black metaphors,” which posits that blackness inheres in whiteness in paradoxical and complex ways, see (Whitaker 2019). |

| 3 | To be clear, Sergeyev’s 1948 revival for the (then) Kirov Ballet greatly altered Petipa’s contribution. The Sergeyev notations are housed in Harvard University’s Theater Collection, and many manuscripts have been digitized. For more studies on Raymonda, see (Meisner 2019, esp. 249; Grigorovich and Vanslow 1989; Fullington 1998, p. 77; Fullington 2022, ch. 3; Fullington and Smith 2024, ch. 10; Garafola 2003). |

| 4 | For translations of Pashkova’s libretto, see (Wiley [1990] 2007, pp. 393–401; Fullington and Smith 2024, pp. 797–803). For a translation of Petipa’s notes to Glazunov (based on Pashkova’s libretto), see (Petipa 1975–1976, pp. 38–44). |

| 5 | Douglas Fullington and Marian Smith note (but do not offer decisive evidence) that the ballet’s protagonist may have been inspired by an historical figure from medieval France: “Perhaps the only medieval counterpart of the character of Raymonda heretofore identified is Raymonde, daughter of Raymond VI (1194–1222), count of Toulouse, who became a nun at the monastery of Espinasse” (Fullington and Smith 2024, p. 598 n.6). |

| 6 | Both Jean de Brienne (c. 1170–1237) and King Andrew (alternatively spelled Andrey, Andree, or Andrei) II of Hungary (1177–1235) were actual figures from medieval history, but they did not collaborate in the way the ballet suggests, nor were they nephew and uncle. Theater historian Sergey Konaev believes that the presence of King Andrew facilitated Petipa’s/Glazunov’s inclusion of Hungarian-themed national/folk dances in Act III (cited in Macaulay et al. 2022). In a similar vein, historian Guy Perry believes Raymonda takes place during the Fifth Crusade precisely because Hungary had a more overt role in that particular military venture, further facilitating the national dances (Perry 2013, p. 9). |

| 7 | Douglas Fullington and Marian Smith observe that Pashkova’s White Lady comes from a supernatural guardian character in Sir Walter Scott’s 1820 novel, The Monastery (Fullington and Smith 2024, p. 598), though Alastair Macaulay suspects that the librettist found inspiration from Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 Gothic thriller, The Mysteries of Udolpho, specifically the ghostly ancestral protector character known as the Marchioness de Villeroi (Macaulay et al. 2022). In Raymonda, Countess Sybille (whom the libretto also identifies as a canoness), explains the White Lady’s identity during a pantomime sequence in Act I. Sybille communicates that the White Lady is a “revered ancestor” and protector of the House of Doris who warns them about impending danger and exerts a retributive function, “[punishing those] who do not fulfill their responsibilities” (cited in Wiley [1990] 2007, p. 397; see also Petipa 1975–1976, pp. 38–39). |

| 8 | According to Fullington, at Le Tournoi, the tournament-themed conclusion to the original Raymonda, “the scenery rises to reveal a square full of people, with knights on horses engaged in combat” (Fullington 1998, p. 82). To date, I have not witnessed a ballet performance that still includes the apotheosis. |

| 9 | A critic from The Saint Petersburg Gazette called Raymonda a “grandiose success,” after which Petipa and Glazunov each received a laurel wreath, see (Wiley [1990] 2007, p. 393). For more studies on Raymonda, see (Garafola 2003; Meisner 2019, esp. 249; Grigorovich and Vanslow 1989; Fullington 2022, esp. ch. 3; Fullington and Smith 2024, ch. 10). After Raymonda, Petipa created an additional six ballets during the early 1900s. |

| 10 | To be clear, both Balanchine/Danilova and Nureyev staged several versions of their respective Raymondas. Balanchine produced subsequent (though more streamlined) full-length versions for the Ballet Russe in later years, whereas Nureyev produced earlier versions for the Royal Ballet (for the Spoleto Festival in 1964), Australian Ballet (1965), Zurich Opera Ballet (1972), and American Ballet Theatre (1975), which featured Byzantine-styled sets by Barry Kay, see (Anderson 2016, p. 65; Balanchine 1984, esp. 172–73). In later decades, Balanchine stripped Raymonda’s overarching narrative and arranged select divertissements and pas de deux (primarily from Act III) in his Pas de Dix (1955), Raymonda Variations (1961), and Cortège Hongrois (1973). For more details on Balanchine’s Raymonda and his collaboration with Danilova, see (Garafola 2003; Danilova and Fullington 1998). Moreover, in Russia, Simon Morrison notes that Raymonda remained so popular over the years that even local Soviet hair salons were named after the ballet and its heroine (Morrison 2016, p. 351). |

| 11 | Dance historians often refer to Pashkova—who also served as the St. Petersburg correspondent for Le Figaro and produced two ballet librettos before Raymonda—as a “minor” or “society” novelist (Meisner 2019, p. 38; Fullington 1998, p. 77). In contrast, Sergey Konaev views Pashkova as a complex, yet misunderstood figure (see Macaulay et al. 2022). |

| 12 | Although Balanchine considered Glazunov’s score one of the finest of the ballet canon, he found that the story was “nonsense” and “difficult to understand;” see (Balanchine and Mason [1954] 1977, p. 468). Alexandre Benois, who designed the sets for Balanchine’s Raymonda, found the story absurd (cited in Garafola 2003, p. 9), whereas the sartorial anachronisms (e.g., armored knights next to ballerinas in tutus) irked Mikhail Fokine (cited in Beaton 1949, p. 45). Sir Frederick Ashton considered choreographing his own Raymonda, but abandoned it because he disliked the plot; see (Vaughan 1975–1976, p. 33; Macaulay et al. 2022). |

| 13 | Tim Scholl explains how, in the years following the Russian Revolution, the culture of Proletkult (proletarian culture) transformed ballet into a spectacle for the masses (Scholl 2004, pp. 69, 101). |

| 14 | For historian Guy Perry, the fall of the Brienne dynasty in the mid-fourteenth century mirrors the fall into relative obscurity of Raymonda by the mid-twentieth century (Perry 2018, p. 185). Konaev clarifiess, however, that Raymonda remains an important component of Russian repertory (cited in Macaulay et al. 2022). |

| 15 | Perry suggests that, at some point, Andrew II and Jean may have resembled rivals more than allies, given that Andrew thought himself a better contender for King of Jerusalem (Perry 2013, p. 91). Counteracting Raymonda’s image of benevolence, Andrew was an unpopular ruler who conspired against his elder brother. Interestingly, his daughter, St. Elizabeth of Hungary (d. 1231, canonized in 1235), was known for her acts of charity and Franciscan piety and abandoned dancing and games to appear less vain (Dickason 2021, pp. 149–50). |

| 16 | Notably, the House of Brienne seal depicts a militant knight riding on horseback, clad in chainmail armor, and wielding a sword, which can be viewed online via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_de_Brienne_1288.jpg (accessed on 13 July 2025). |

| 17 | For more detail regarding Jean de Brienne’s seal, see (Perry 2013, p. 54). |

| 18 | However, Jean de Brienne eventually developed hostility toward the Hohenstaufens (Perry 2018, p. 66; Perry 2013, pp. 122, 135, 137). |

| 19 | In this letter, Jean goes on to recount the Siege of Damietta and also reaffirms the crusaders’ desire to perpetuate their dominion over the Holy Land. |

| 20 | When discussing (proto)colonialism in the Middle Ages, it is noteworthy that many premodern Islamic caliphates were powerful and had amassed substantial wealth; see (Şahin et al. 2021). Therefore, premodern “colonized” or “subaltern” identities are not equivalent to those theorized vis-à-vis modern acts of colonization. |

| 21 | As Claster explains, some scholars extend the Crusades timeline until 1396, following the Battle of Nicopolis (Claster 2009, pp. xvi, 303–5). |

| 22 | For related studies on power and race-making in Frederick’s court, see (Heng 2015, pp. 25–26; Kaplan 1987, p. 32). |

| 23 | Following Shokoofeh Rajabzadeh, I acknowledge the problematic valences of this term in medieval primary sources. When necessary to invoke this terminology in my own writing, I, like Rajabzadeh, place it in quotation marks (Rajabzadeh 2019, pp. 1–8). |

| 24 | For scholarship on representations of Islamic dance in the West, see (Temple 2001, pp. 34, 66–75; Zeitler 1997, p. 36; Folda 2005, pp. 421, 471; Kapitaikin 2019, pp. 3–9; Kaplan 1987, p. 29; Wollesen 2013, pp. 345–57). |

| 25 | For a study on medievalism and Orientalism in The Nutcracker ballet, see (Dickason 2023b). For a broader study of Orientalism and medievalism in modernity, see (Ganim 2005; Matthews 2024). |

| 26 | In her study of Balanchine’s 1946 Raymonda for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (co-staged by Danilova), Garafola argues that, for Balanchine, remaking this ballet constituted an homage to Petipa and an aesthetic return to the old Russia; it thus differed from the neoclassical and modernist experiments of his youth. As Garafola writes, “it was Raymonda, and Balanchine’s intense, prolonged involvement with Petipa’s choreography, that precipitated the great ‘neo-Imperial’ ballets of 1947 [Le Palais de Cristal/Symphony in C and Theme and Variations]. Here were Petipa’s grand visions, his processionals, and variations, heavenly hierarchies, and poems of love, fully distilled and imaginatively reinvented… Thanks to Raymonda, Balanchine had finally come home to Petipa and Petersburg” (Garafola 2003, p. 15). I thank Lynn Garafola for sharing her unpublished paper with me. |

| 27 | Incidentally, Jean de Brienne became a relative of Louis IX through his third marriage to Berengaria of Léon-Castile. Reportedly, Jean’s sons were treated with courtesy and respect at the court of Louis IX back in France (Perry 2013, pp. 164–65). |

| 28 | Another interesting Crusades-related dance reference is the Maltese branle, supposedly devised by the Knights of Malta, see (Arbeau [1589] 1967, p. 153; Dickason 2023a, p. 324). |

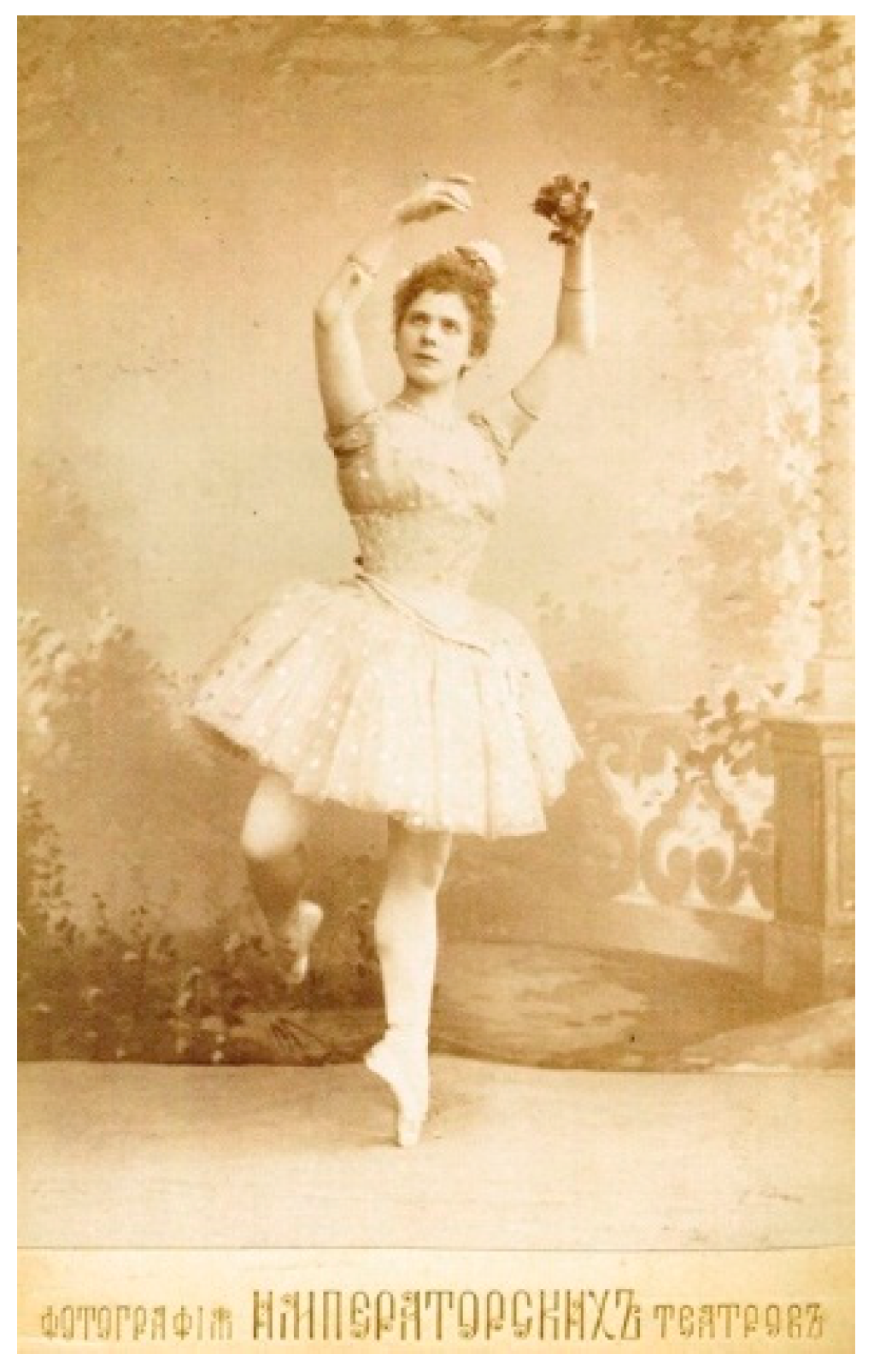

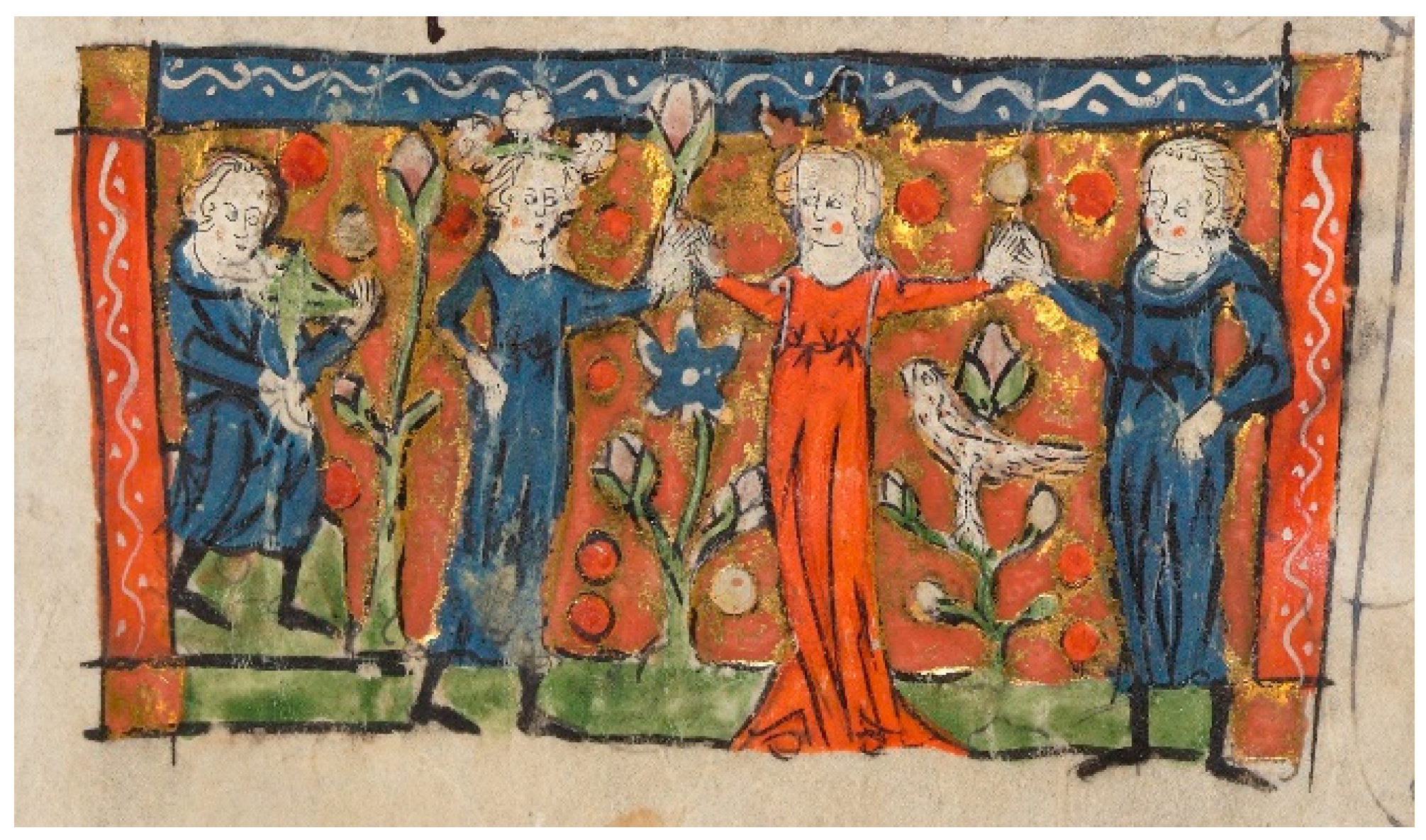

| 29 | For additional dance imagery from the Morgan Crusader Bible, see Morgan Library and Museum, MS. M 638, fols. 13v, 17r, 29r, and 39v (Anon. Circa 1240). |

| 30 | Belle da Costa Greene was recently the subject of a landmark exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum, “Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy.” As a Black woman who passed as White among New York’s elite circles in the early twentieth century, Greene was a complicated figure, see (Ardizzone 2007; Als 2024). Sierra Lomuto cautions against reducing Greene’s legacy to a DEI-inflected initiative that champions a global medieval studies approach. Moreover, Lomuto explains that, although Greene curated African and Asian premodern manuscripts as well as European ones, Greene still inhabited an American culture rife with imperialist and colonial roots, see (Lomuto 2023, pp. 15, 17). For more on Greene’s contributions to medieval studies in the United States, see (Eze 2024). |

| 31 | The Fifth Crusade was ultimately unsuccessful, and Latin crusaders could not recapture Jerusalem. |

| 32 | The image in question is from the Morgan Crusader Bible, Morgan Library and Museum MS. M 638, fol. 29r, which can be viewed online via the Morgan’s Corsair visual database: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/57, accessed 16 February 2025. Critical biographies of King David underscore his lust for power and proclivity for violence, see (McKenzie 2000; Baden 2013). |

| 33 | The illustration can be viewed online via the Morgan Library and Museum’s Corsair database: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/78 (accessed on 10 July 2025). |

| 34 | According to Heng, “[religion] could function both socioculturally and biopolitically: subjecting peoples of a detested faith, for instance, to a political theology that could biologize and define, and essentialize an entire community as fundamentally and absolutely different in an interknotted cluster of ways,” (Heng 2018, p. 3). |

| 35 | According to Polo, the ritual of these castle dwellers is related to the Three Magi. |

| 36 | The fourteenth-century (Pseudo) John Mandeville, in his largely fictitious The Book of John Mandeville or The Book of Marvels, similarly decries the “cruel Jews” (chiens juifs) and “miscreant Muslims” (mescreans) he allegedly encountered in his travels (Mandeville 2011, pp. xx, 3–4; Mandeville 2023, pp. 168, 170). When traveling through the Holy Land, the author reminds readers of how Jews tortured and killed Christ and he expresses disgust for Muslims’ polygamy and their supposed literal interpretations of sacred texts (Mandeville 2011, pp. 50, 58, 69, 85–86). |

| 37 | Specifically, Lomuto analyzes a female literary figure (“the Mongol Princess”) from the fourteenth-century romance The King of Tars (Lomuto 2019). |

| 38 | The Marius Petipa Society website contains photographs of Pavel Gerdt in costume, as well as numerous other original Raymonda cast members: https://petipasociety.com/raymonda/, accessed 16 February 2025. |

| 39 | See also the Bolshoi Ballet’s 2024 production (choreography by Yuri Grigorovich after Marius Petipa and Alexander Gorsky) with Pavel Dmitrichenko as Abderrakhman. |

| 40 | For American critiques on the persistent use of blackface in Russian ballet, see (Marshall 2019; Nichols 2019). The racialization of Muslims originated in the Middle Ages, as Muslims were often Black in the European imaginary, see Le Chanson de Roland, in (Anon 1978, esp. 2; Heng 2003, pp. 70–71; Kinoshita 2001; Alfonso X 2000, esp. 99, p. 401; Akbari 2009, pp. 156, 175, 200, 236; Cohen 2001, p. 114; Sturges 2015, p. 15; Armstrong 2006, p. 177; De Weever 1994; De Weever 1998, ch. 1). |

| 41 | Incidentally, George Balanchine danced the role of one of the “Arab boys” in a Mariinsky production during his childhood in St. Petersburg (Balanchine and Mason [1954] 1977, p. 500; Garafola 2003, p. 3). For more on exoticized musical motifs in Glazunov’s score, see (Edgecombe 2008). |

| 42 | Zoë Anderson describes Tharp’s work as simultaneously “modern and Russian” (Anderson 2016, p. 66; see also Greskovic 1998, p. 555). |

| 43 | The production can be viewed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEfkK4UsMNc, accessed 15 February 2025. Interestingly, theater historian Sergey Konaev mentions a (now retired) 1938 Soviet version that may be the first “decolonial” Raymonda. As he recounts, “In that production, Raymonda was finally disappointed with a mean cold crusader [Jean de Brienne] and married Abderrakhman, who was shown as kind, trusty and good” (cited in Macaulay et al. 2022). Lynn Garafola refers to this same production as a “Socialist Realist version” (Garafola 2003, pp. 2–3). |

| 44 | To be fair, Yuri Grigorovich’s 1984 Bolshoi Ballet restaging also attempted to render Raymonda into a stronger and more autonomous character. As he wrote, “Raymonda is about flourishing femininity, about a woman’s love seeking for harmony [sic], about a mysterious soul [that] preserves its whole heartedness in spite of its inconsistencies.” Grigorovich continues by extolling the great Soviet ballerina Natalia Bessmertnova’s peerless portrayal of the heroine: “Her Raymonda is a whole philosophy of woman’s nature in which fidelity and self-will, tenderness and obstinacy, fearlessness and unprotectedness, steadfastness and fragility fascinatingly coexist” (Grigorovich and Vanslow 1989, p. 38). Along these lines, Willa Cather’s 1918 novel My Antonia derived inspiration from Raymonda, which, according to Wendy Perriman, gave Cather a blueprint for strong, matriarchal female characters who value cultural heritage (Perriman 2009, esp. 108–11). |

| 45 | Now the Artistic Director of San Francisco Ballet, Tamara Rojo brought her Raymonda production to the West Coast in March 2025. |

| 46 | Perdziola explains his approach and previews select costumes here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OMDrKhkIc_o, accessed 15 February 2025. |

| 47 | Although Nissinen’s production is very much a recalibrated classic, the monumental versions of Petipa, Grigorovich, and Nureyev deeply inspired him. Nissinen also admires a 2022 Dutch National Ballet production that was choreographed by Rachel Beaujean (after Petipa). According to the company website, “Beaujean decided to overhaul the libretto and, partly inspired by series like Game of Thrones and Bridgerton, to adapt the storyline so that today’s audiences can relate to it. In her production, therefore, the young Hungarian grand duchess Raymonda does not simply do as she’s told and marry the vain crusader Jean de Brienne. Instead, she is a young, independent woman who, attracted to the mysterious Abd al-Rahman, makes her own decisions on the path of love.” See: https://www.operaballet.nl/en/dutch-national-ballet/2023-2024/raymonda, accessed 15 February 2025. |

| 48 | However, I will add that Jean de Brienne’s identity as a crusader in the Boston Ballet’s production does not eliminate the specters of colonialism and Islamophobia that undergird the original Raymonda. Moreover, Jennifer Heimlich notes that Nissinen did not consult diversity experts when reconceiving the new production (Heimlich 2024). |

| 49 | Several balletomanes seem to be confused about the setting for the ballet, stating that it takes place in Hungary (Balanchine and Mason [1954] 1977, p. 468; Greskovic 1998, p. 47). |

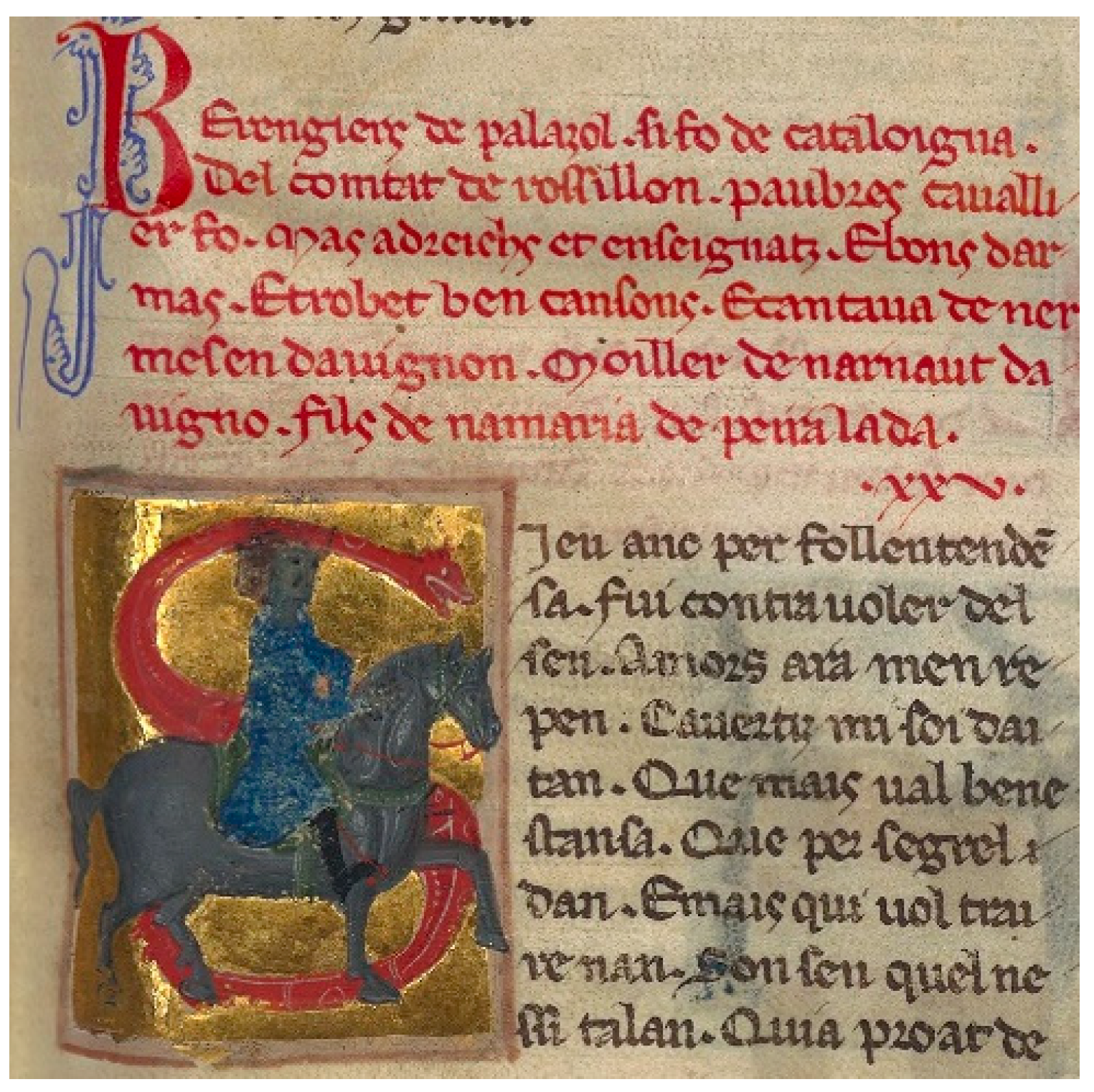

| 50 | The original Raymonda program notes identify Béranger as a troubadour of Aquitaine (Wiley [1990] 2007, p. 394), but I found no such record of a Provençal troubadour with this name. It is possible that the character is entirely fictional. |

| 51 | For example, see the first two stanzas of Bernard’s canso “Tant ai mo cor ple de joya,/tot me desnatura./Flor blancha, vermeilh’e groya/me par la frejura,/c’ab lo ven et ab la ploya/me creis l’aventura,/per que mos chans mont’ e poya/e mos pretz melhura./Tan ai al cor d’amor,/de joi e de doussor,/per qu’el gels me sembla flor/e la neus verdura./Anar posc ses vestidura,/nutz en ma chamiza,/car fin’amors m’asegura/de la freja biza./Mas es fols qui.s desmezura,/e no.s te de guiza,/Per qu’eu ai pres de me cura,/deis c’agui enquiza/la plus bela d’amor,/don aten tan d’onor,/car en loc de sa ricor/non volh aver Piza [My heart is so full of joy,/all is changed for me./Flowering red, white, and yellow,/the winter seems to be,/for, with the wind and rain, so/my fortune’s bright I see,/my songs they rise, and grow/my worth proportionately./Such love in my heart I find,/such joy and sweetness mine,/ice turns to flowers fine/and snow to greenery./I go without my clothes now,/one thin shirt for me,/for noble love protects now/from the chilly breeze./But he’s mad who’ll not follow/custom and harmony,/so I’ve taken care I vow/since I sought to be/lover of loveliest,/to be with honor blest: /of her riches I’d not divest/for Pisa, for Italy.]” (de Ventadorn n.d., cited and trans. in Goldin 1973, pp. 131–32). |

| 52 | Here is the stanza in full: “Bona dona, cuy ricx pretz fai valer/sobre las plus valens al mieu vejaire,/avetz razo per quem dejatz estraire/lo belh solatz nil amoros parer,/si non quar vos auziey anc far saber/qu’ieus amava mil aitans mais que me ?/En aquest tort me trobaretz jasse,/quar non est tortz que jaus pogues desfaire. [My fine lady, whom in my opinion noble merit lifts high above the most worthy, have you any reason for daring to withdraw your charming company and your loving appearance from me, unless it be because I have heard you make it known that I loved you a thousand times more than myself? You will always find me at fault in this respect for it is not an error that I could ever correct for you.”] (In Berenger [Berenguier] de Palazol 1971, pp. 75, 77). |

| 53 | For a psychoanalytic reading of troubadours’ desire, see (Lacan [1986] 1992). |

| 54 | Petipa’s notes to Glazunov indicate the importance of this moment: “You must pay special attention to this entrance. It is for the prima ballerina” (Petipa 1975–1976, p. 39). According to a critic writing for The Saint Petersburg Gazette in 1898, Legnani danced the role of Raymonda “superbly—with incomparable grace, plastique, and strength of movements” (cited in Wiley [1990] 2007, p. 393). |

| 55 | Photographs showing the medievalesque circular formations and garlands appear on the Mariinsky Ballet’s website: https://www.mariinsky.ru/en/playbill/repertoire/ballet/raimonda/, accessed 14 February 2025. |

| 56 | Scholar Robert Mullally claims that the lower classes also danced the carole (Mullally 2011, pp. xv, 14). However, in my examination of medieval literature, I have come across very few references to peasants performing this dance, one example being the thirteenth-century Le Roman de Manekine by Philippe de Rémi. Relevant to medieval round dances, Petipa’s choreographic notes for Act I of Raymonda specify a “circle dance (khovorod)” (Petipa 1975–1976, pp. 39), whereas Byzantinist Nicoletta Isar has traced the ancient and medieval roots of the khovorod that reappear in Vaslav Nijinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (Isar 2023). |

| 57 | Petipa’s choreographic notes for the Traditore specify that “feet cross and recross in a gliding pas,” and, during the Romanesque section, Raymonda plays the lute while her friends (the troubadours and their female companions) dance (Petipa 1975–1976, pp. 38, 40). For a study on the theological significance of crossed legs/feet in medieval European art, see (Pentcheva 2023). |

| 58 | Moreover, a dance motif appears in a tenso (debate song) featuring trobairitz Domna Duran and her husband Peire Duran, cited in (Bruckner et al. [1995] 2000, pp. 64–65). |

| 59 | Scholars surmise that the vernacular tresca may have been a stamping dance (like the Occitan estampida or Old French estampie), but the term is also philologically linked to the word for weave/weaving. Scholar Mark Taylor suggests that Marcabru could have employed this dance metaphor to indicate trobar as a weaving of words, see (Taylor 2000, pp. 353–54). |

| 60 | Some scholars surmise that Jean de Brienne may have composed trouvère-style songs as well, and a spurious account of his life by a certain Minstrel of Reims presents him as a courtly and chivalric hero at tournaments (Perry 2013, pp. 7, 17–18, 26–29). |

| 61 | It is also noteworthy that Provençal troubadours, who were essentially victims of genocide via the Albigensian Crusade, nevertheless peppered their songs with ethnic slurs when referring to the Muslim enemies abroad, e.g., Giraut Riquier’s “Be m degra de chanter tener” and Peire Cardenal’s “Clergue si fan pastor.” |

| 62 | Of all the modern re-stagings of Raymonda, Yuri Grigorovich’s 1984 production for the Bolshoi Ballet best captures the White Lady’s medieval, lyrical, and ancestral elements. As he and Vanslow wrote, “As an image of the knight’s poetry, a symbol of fate, the White Lady is preserved [in Grigorovich’s version] … In her white glimmering dress, majestically dominating on the tips of her toes, she is the center of all this mysteriously-shadowed stage. She is a symbol of the heroine’s soul, a support for her activity, purity in the vortex of confused feelings, luring expectations, frightening forebodings” (Grigorovich and Vanslow 1989, p. 35). However, the Bolshoi seemed to have excised the White Lady from its Raymonda circa 2003. |

| 63 | The Royal Danish production, with Femke Mølbach Slotcan as the White Lady, can be viewed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEfkK4UsMNc&t=1774s; as well as a 1989 filmed Bolshoi Ballet production with Irina Dmitrieva as the White Lady: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dKFykYtR5YQ, both accessed 14 February 2025. |

| 64 | Interestingly, the pyrotechnic special effects of the ballet’s first staging were troubadouresque. Fullington and Smith describe how the original White Lady descended from a pedestal during her first entrance (Fullington and Smith 2024, p. 631; Fullington 2022, p. 276). As Grigorovich notes, “Glazunov easily transferred his imagination to the romantic epoch of the Middle Ages to which he had been attracted since childhood. He read many books about those times, knew the historic events very well … Glazunov spoke with enthusiasm about knighthood and knights, about poet-singers (troubadours), trouvères, and minstrels, about performances on the squares of medieval towns and about life in castles.” Not long before Glazunov started working on Raymonda, Grigorovich adds, he traveled through Germany, where he witnessed many medieval monuments, including Cologne Cathedral (Grigorovich and Vanslow 1989, pp. 20–21). On a similar note, Konaev avers that Petipa “always did his homework well,” which entailed historical and iconographic research on French monarchs (cited in Macaulay et al. 2022). |

| 65 | Reflecting upon Raymonda decades after she danced it, Danilova remembers that the White Lady danced to “big music” (Danilova and Fullington 1998, p. 73). Petipa’s notes to Glazunov indicate that the White Lady’s entrance should be: “Music in a style somewhat pathétique [a musical term for an emotional and sentimental style], ideal. All of this passage will show your inspiration to advantage” (Petipa 1975–1976, p. 41). |

| 66 | Balanchine-Danilova eventually dropped the White Lady character from subsequent Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo performances (Fullington 2022, p. 342). Later choreographers and scholars echo Danilova’s dismissal of her: for example, Alastair Macaulay recounts that “in 1984, I asked Frederick Ashton if he had ever considered choreographing a complete Raymonda around the bits of Petipa choreography that were then known to him. He replied, ‘When I looked at the story, it involved a White Lady. The only White Lady I knew was a cocktail’” (Macaulay et al. 2022). Moreover, Nadine Meisner refers to the White Lady as a “feeble version of the Lilac Fairy [from Petipa’s 1890 Sleeping Beauty ballet]” (Meisner 2019, p. 249; see also Wiley [1990] 2007, p. 392; Danilova and Fullington 1998, p. 75). |

| 67 | Nissinen explains the Dame Blanche’s role in his new Raymonda production: “The dream scene has the White Lady. She is basically a sculpture in a house who is a spiritual protector of the family and of family history in one sculpture. This sculpture has seen every baby born in the long history of this family, and every death and every fight. In the original version, the White Lady becomes a live person. I have used the White Lady very shortly, about three minutes. When Raymonda is sleeping on her divan, she [the White Lady] comes alive and wakens Raymonda and brings Jean de Brienne and circulates them until their hands touch. And that’s the beginning of the dream pas de deux” (Nissinen and Stinchcomb 2024). Among all the Raymonda readaptations I have studied, a 2022 production by the Astrakhan State Theater of Opera and Ballet gives the most choreographic and narrative prominence to Dame Blanche; see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V557ySdBN7s, accessed 18 February 2025. |

| 68 | In Nureyev’s psychologically dense Raymonda, the titular heroine has erotic fantasies about both men, but Abderrakhman turns out to be an illusion (Vaughan 1975–1976, p. 33). |

| 69 | For more on the social status of qiyān, see (Richardson 2009; Gordon 2009; Nielson 2021, p. 64). Qiyān are sometimes compared to the hetaerae of ancient Greece, the geishas of Japan, or the courtesans of Renaissance Italy. |

| 70 | According to Al-Jāhiz, they could memorize between 4000 and 10,000 songs (Al-Jāhiz 1980, p. 35). |

| 71 | Shay notes that, although the Qur’an does not prohibit dance, dancing was often connected to sex and prostitution in Islamic culture (Shay 2014, pp. 111–12). For possible illustrations of the qiyān, see Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana ms. Arab 368, fol. 9r: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.ar.368; and the (reconstructed) Samarra fresco: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Painting-reconstructing-the-image-of-unveiled-female-dancers-depicted-in-a-fresco-from_fig3_269279292, both accessed 16 February 2025. I thank Lev Arie Kapitaikin for informing me about these works of art. |

| 72 | Incidentally, Jean de Brienne gives Raymonda a scarf before he leaves for the Crusades. In a famous solo variation from Act I, Raymonda dances with the scarf (pas de châle). In a 2022 production by the Astrakhan State Theater of Opera and Ballet, Dame Blanche covers Raymonda with this scarf at the end of the dream vision. Moreover, her diaphanous wimple and bell sleeves recall Raymonda’s scarf, as well as medieval fashion. |

| 73 | For a study on Iberian dance during Late Antiquity, during which Church Fathers associated dancing with heresy, see (Tronca 2021). |

| 74 | Interestingly, Jean de Brienne’s third marriage to Berengaria of Léon-Castile (d. 1237, daughter of King Alfonso IX of Léon and Queen Berengaria of Castile) formed an alliance between France and Iberia (Perry 2018, p. 188). For scholarship tracing the profound influence of Middle Eastern dance and music (via the Crusades) on Western European dance, see (Temple 2001, pp. 34, 66–75; Kapitaikin 2019, pp. 3–9; Valls 2019, esp. 25, 37). For a study tracing the medieval Islamicate origins of flamenco, see (Goldberg 2023). |

| 75 | In a comparable vein, Konaev reappraises Pashkova’s libretto, revealing her authorial deftness. He considers Pashkova an “ideal person for herstory,” given her extensive travels, rich social encounters, and novels with strong female characters. In fact, Konaev believes that Raymonda is a reworking of a semi-autobiographical novel, Hannah Pacha (1880), that Pashkova wrote. Moreover, Konaev explains that Pashkova was often drawn to Islamic themes in a sympathetic (rather than intolerant) way. |

| 76 | See also Akram Khan’s and Phil Chan’s comments on the productive potential of vulnerability, curiosity, and subversion when performing controversial works (Chan and Chase 2023, pp. 231, 244). |

| 77 | In a forthcoming essay, I provide evidence for the medieval origins of ballet more broadly. This research differs from traditional narratives, which locate the beginnings of ballet in the Renaissance or Baroque periods (Homans 2010, esp. 3–11). However, Jennifer Homans’ recent biography of Balanchine reveals the importance of medieval concepts (e.g., chivalry, courtly love, and religious icons) for twentieth-century ballet (Homans 2022). |

| 78 | For additional critiques of the underlying Eurocentrism of certain global medieval studies implementations (especially within English departments), see (Orlemanski 2024; De Souza 2024; Lomuto 2020; Lomuto 2023). |

References

- Akbari, Suzanne. 2000. From Due East to True North: Orientalism and Orientation. In The Postcolonial Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey Cohen. New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, Suzanne. 2009. Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso X. 2000. Songs of Holy Mary by Alfonso X, The Wise: A Translation of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. Edited and Translated by Kathleen Kulp-Hill. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jāhiz [Abu Uthman Amr ibn Bahr al-Kinani al-Basri]. 1980. The Epistle on Singing-Girls of Jāhiz. Edited and Translated by Alfred Felix Landon Beeston. Wilst: Aris and Phillips Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Allworth, Edward. 1994. Central Asia: 130 Years of Russian Dominance. Durham, NC and London: Duke Univeristy Press. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Als, Hilton. 2024. The Hidden Story of J.P. Morgan’s Librarian. The New Yorker. December 16. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/12/23/belle-da-costa-greene-art-review-morgan-library (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Anderson, Zoë. 2016. The Ballet Lover’s Companion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. 1978. The Song of Roland: An Analytical Edition. Edited and Translated by Gerald Brault. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. 2024. Raymonda’s Wedding. Available online: https://trockadero.org/company/repertory/ballets/raymondas-wedding-2/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Anon. Circa. 1240. Morgan Crusader Bible. French, Morgan Library and Museum, MS. M 638. Available online: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/6 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Arbeau, Thoinot. 1967. Orchesography. Translated by Mary Stewart Evans. Edited by Julia Sutton. New York: Dover. First published 1589. [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzone, Heidi. 2007. An Illuminated Life: Belle da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege. New York: W. W. Norton and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Dorsey. 2006. Postcolonial Palomides: Malory’s Saracen Knight and the Unmaking of the Arthurian Community. Exemplaria 18: 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, Elizabeth. 2000. The Music of the Troubadours. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, Joel. 2013. The Historical David: The Real Life of an Invented Hero. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Balanchine, George. 1984. Choreography by Balanchine: A Catalogue of Works. New York: Viking and Eakins Press Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Balanchine, George, and Francis Mason. 1977. Balanchine’s Complete Stories of the Great Ballets. New York: Doubleday. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Robert. 1994. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, Cecil. 1949. Ballet. New York: Wingate and Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, Cyril. 1941. Complete Book of Ballets: A Guide to the Principal Ballets of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Garden City and New York: Garden City Publishing. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Bogin, Meg. 1976. The Women Troubadours. New York: W. W. Norton and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner, Matilda, Laurie Shepard, and Sarah White, eds. 2000. Songs of the Women Troubadours. New York: Garland. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Burack, Cristina. 2024. Marco Polo: The Travel Writer Who Shocked Medieval Europe. DW. March 18. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/marco-polo-the-travel-writer-who-shocked-medieval-europe/a-68540522 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1995. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Karen. 2024. Can ‘Raymonda’ Be Redeemed in Full? Boston Ballet Premieres Mikko Nissinen’s Remake. The Boston Globe. February 15. Available online: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/02/15/arts/boston-ballet-to-premiere-mikko-nissinens-remake-of-raymonda/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Caswell, Fuad Matthew. 2011. The Slave Girls of Baghdad: The Qiyān in the Early Abbasid Era. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Cawsey, Kathy. 2009. Disorienting Orientalism: Finding Saracens in Strange Places in Late Medieval English Manuscripts. Exemplaria 21: 380–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaganti, Seeta. 2011. Under the Angle: Memory, History, and Dance in Nineteenth-Century Medievalism. Austrian Literary Studies 26: 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Phil, and Michele Chase. 2023. Banishing Orientalism: Dancing Between Exotic and Familiar. Brooklyn: Yellow Peril Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Mary, and Clement Crisp. 1981. The Ballet Goer’s Guide. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Claster, Jill. 2009. Sacred Violence: The European Crusades to the Middle East, 1095–1396. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jeffrey. 2001. On Saracen Enjoyment: Some Fantasies of Race in Late Medieval France and England. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31: 113–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, Giles. 2008. Crusaders and Crusading in the Twelfth Century. Surrey: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Cruse, Mark. 2020. ‘Pleasure in Foreign Things’: Global Entanglements in the Livre des merveilles du monde (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 2810). Mediaevalia 41: 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilova, Alexandra, and Doug Fullington. 1998. Alexandra Danilova on Raymonda. Ballet Review 26: 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- de Joinville, Jean. 1874. Histoire de Saint Louis; Credo; et Lettre à Louis X. Edited by Natalis de Wailly. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot. [Google Scholar]

- de Joinville, Jean. 1963. Chronicles of the Crusades. Translated by Margaret Shaw. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- de Palazol, Berenger [Berenguier]. 1971. The Troubadour Berenger de Palazol: A Critical Edition of His Poems. Edited and Translated by Terence Newcombe. Nottingham Medieval Studies 15: 54–95. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, Rebecca. 2024. Are There Limits to Globalising the Medieval? postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 15: 257–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ventadorn, Bernart. n.d. Accessed 2025. Twelfth Century. “Tant ai mo cor ple de joya.”. Available online: http://trobar.org/troubadours/bernart_de_ventadorn/beven4.php (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- De Weever, Jacqueline. 1994. Nicolette’s Blackness: Lost in Translation. Romance Notes 34: 317–25. [Google Scholar]

- De Weever, Jacqueline. 1998. Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Dickason, Kathryn. 2020. King David in the Medieval Archives: Toward an Archaic Future for Dance Studies. In Futures of Dance Studies. Edited by Susan Manning, Janice Ross and Rebecca Schneider. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 36–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dickason, Kathryn. 2021. Ringleaders of Redemption: How Medieval Dance Became Sacred. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dickason, Kathryn. 2023a. The Colonization of Medieval Dance. Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies 54: 313–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickason, Kathryn. 2023b. Toying with Dance: A Medievalist Interprets The Nutcracker Ballet. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 14: 457–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgecombe, Rodney Stenning. 2008. Internationalism, Regionalism, and Glazunov’s Raymonda. The Musical Times 149: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, Marcel. 2025. Unsettling Orientalism: Toward a New History of European Representations of Muslims and Islam, c. 1200–1450. Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies 100: 466–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, Anne-Marie. 2024. The Ballad of Belle da Costa Greene: Librarian as Medievalist. In Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy. Edited by Erica Ciallela and Philip Palmer. New York: Morgan Library and Museum and DelMonico Books, pp. 133–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, Françoise. 1986. Le Jeu de Robin et Marion: Robin danse devant Marion, sens du passage et sens de l’œuvre. Revue des Langues Romanes 90: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Folda, Jaroslav. 2005. Crusader Art in the Holy Land: From the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre, 1187–1291. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fullington, Doug, and Marian Smith. 2024. Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg: Giselle, Paquita, Le Corsaire, La Bayadère, Raymonda. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fullington, Douglas. 1998. Raymonda at 100. Ballet Review 26: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fullington, Douglas. 2022. A Source Study of Two Ballets and a Divertissement by Marius Petipa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, Marisa. 2012. Songbook: How Lyrics Became Poetry in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, Marisa. 2020. The Subject of Crusade: Lyric, Romance, and Materials, 1150–1500. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ganim, John. 2005. Medievalism and Orientalism: Three Essays on Literature, Architecture, and Cultural Identity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Garafola, Lynn. 2003. Balanchine and Raymonda: The Americanization of a Classic. In Symposium Paper for from the Mariinsky to Manhattan: George Balanchine and the Transformation of American Dance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, October 31. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt, Simon. 1995. Gender and Genre in Medieval French Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, K. Meira. 2023. Singing of and with the Other: Flamenco and the Politics of Pastoralism in Medieval Iberia. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 14: 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, Frederick. 1973. Lyrics of the Troubadours and Trouvères: An Anthology and a History. Garden City: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Matthew. 2009. Yearning and Disquiet: Al-Jāhiz and the Risālat al-qiyān. In Al-Jāhiz: A Muslim Humanist for Our Time. Edited by Arnim Heinemann, John Meloy, Tarif Khalidi and Manfred Kropp. Beirut: Ergon Verlag, pp. 253–68. [Google Scholar]

- Greskovic, Robert. 1998. Ballet 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving the Ballet. New York: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorovich, Yuri, and Victor V. Vanslow. 1989. The Authorized Bolshoi Ballet Book of Raymonda. Translated by Alexander Kroll. NeptuneJ: T. F. H. Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Heimlich, Jennifer. 2024. Boston Ballet Lets Classicism Shine in Its Reimagined Raymonda. Pointe Magazine. February 19. Available online: https://pointemagazine.com/boston-ballet-raymonda-reimagined/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Heng, Geraldine. 2015. An African Saint in Medieval Europe: The Black Saint Maurice and the Enigma of Racial Sanctity. In Sainthood and Race: Marked Flesh, Holy Flesh. Edited by Molly Bassett and Vincent Lloyd. New York: Routledge, pp. 18–44. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, Geraldine. 2018. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, Geraldine. 2023. Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, Jennifer. 2010. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, Jennifer. 2022. Mr. B.: George Balanchine’s 20th Century. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Huot, Sylvia. 2016. Outsiders: The Humanity and Inhumanity of Giants in Medieval French Prose Romance. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Patricia, and Michelle Warren. 2003. Introduction: Postcolonial Modernity and the Rest of History. In Postcolonial Moves: Medieval through Modern. Edited by Patricia Ingham and Michelle Warren. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Isar, Nicoletta. 2023. Pathei mathos and skandalon in Le Sacre du Printemps. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 14: 419–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jays, David. 2022. The Most Powerful Woman in Ballet is Breaking All the Rules. The Times. January 9. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/article/the-most-powerful-woman-in-ballet-is-breaking-all-the-rules-jb2n02k5j (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Jennings, Willie James. 2010. The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kantorowicz, Ernst. 1957. Frederick the Second, 1194–1250. Translated by E. O. Lorimer. New York: Frederick Ungar. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitaikin, Lev Arie. 2019. David’s Dancers in Palermo: Islamic Dance Imagery and Its Christian Recontextualization in the Ceilings of the Cappella Palatina. Early Music 47: 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Paul. 1987. Black Africans in Hohenstaufen Iconography. Gesta 26: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehew, Robert, ed. 2005. Lark in the Morning: The Verses of the Troubadours. Robert Kehew, Ezra Pound, and William De Witt Snodgrass, trans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Shoshana. 2020. Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Convergence. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita. 2024. Marco Polo in Trans-regional Perspective. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 15: 229–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Sharon. 2001. ‘Pagans are wrong and Christians are right’: Alterity, Gender, and Nation in the Chanson de Roland. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31: 79–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1992. Courtly Love as Anamorphosis. In The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, 1959–1960. Edited and Translated by Dennis Porter, and Jacques-Alain Miller. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 139–54. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, Moshe. 1995. Fin’ amor. In A Handbook of the Troubadours. Edited by F. R. P. Akehurst and Judith Davis. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 61–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Suzanne. 1987. The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomuto, Sierra. 2019. The Mongol Princess of Tars: Global Relations and Racial Formation in The King of Tars (c. 1330). Exemplaria: Medieval, Early Modern, Theory 31: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomuto, Sierra. 2020. Becoming Postmedieval: The Stakes of the Global Middle Ages. postmedieval: Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 11: 503–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomuto, Sierra. 2023. Belle da Costa Greene and the Undoing of ‘Medieval’ Studies. Boundary 2: An International Journal of Literature and Culture 50: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomuto, Sierra. 2024. Afterword: Motions of Global Periodization. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 15: 285–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrich, Naomi. 2015. The Wandering Hat: Iterations of the Medieval Jewish Pointed Cap. Jewish History 29: 204–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, Alastair. 2019. Petipa: Precursor to Modern Ballet or Hierarchical Elitist? The New York Times. July 23. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/23/arts/dance/petipa-biography-nadine-meisner.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Macaulay, Alastair, Douglas Fullington, and Sergey Konaev. 2022. ‘Raymonda’ and Ballet Herstory: Historians Doug Fullington and Sergey Konaev on Lydia Pashkova, Ivan Vzevolozhsky, Marius Petipa, and the Russian Imperial Theatres. Alastair Macaulay Personal Website. January 21. Available online: https://www.alastairmacaulay.com/all-essays/byq3y6560y798jcrlmiwp4s4su9ii6 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Mahiet, Damien. 2016. The First ‘Nutcracker,’ the Enchantment of International Relations, and the Franco-Russian Alliance. Dance Research: Journal for the Society of Dance Research 34: 119–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeville, Jean attrib. 2023. Le Livre de Jean de Mandeville. Edited and Translated by Michèle Guéret-Laferté, and Laurence Harf-Lancner. Paris: Champion Classiques. [Google Scholar]

- Mandeville, John attrib. 2011. The Book of John Mandeville with Related Texts. Edited and Translated by Iain Macleod Higgins. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Marcabru. n.d. Twelfth Century. “Contra L’ivern que S’enansa. In Trobar.org. Available online: http://trobar.org/troubadours/marcabru/mcbr14.php (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Marshall, Alex. 2019. Blackface at the Ballet Highlights a Global Divide on Race. The New York Times. December 23. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/arts/dance/blackface-ballet-bolshoi-misty-copeland.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Matthews, David. 2024. In Search of Lost Elsewheres: Medievalism Today. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 15: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Timothy. 1995. Dance. Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. Edited by William Kibler and Grover Zim. London: Routledge, pp. 547–52. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Steven. 2000. David: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meisner, Nadine. 2019. Marius Petipa: The Emperor’s Ballet Master. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menocal, María Rosa. 1990. The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History: A Forgotten Heritage. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menocal, María Rosa. 2002. The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Boston: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Simon. 2016. Bolshoi Confidential: From the Rule of the Tsars to Today. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Mullally, Robert. 2011. The Carole: A Study of a Medieval Dance. Surrey: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Dana. 2019. I Am a Black Dancer Who Was Dressed Up in Blackface to Perform La Bayadère. Dance Magazine. December 11. Available online: https://www.dancemagazine.com/black-face-in-ballet/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Nielson, Lisa. 2021. Music and Musicians in the Medieval Islamicate World: A Social History. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Nissinen, Mikko, and Dale Stinchcomb. 2024. Curating the Classics for Today: Mikko Nissinen on Raymonda. Donors’ Presentation. January 23. Available online: https://www.bostonballet.org/stories/curating-the-classics-for-today-mikko-nissinen-on-raymonda/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Orlemanski, Julie. 2024. Significant Geographies of the Middle Ages: Cluster Introduction. postmedieval: Journal of Medieval Studies 15: 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paden, William. 2024. Reflections on Origins: How Troubadour Poetry Began. In Troubadour Texts and Contexts: Essays in Honor of Wendy Pfeffer. Edited by Courtney Joseph Wells, Lisa Shugert Bevevino and Sarah-Grace Heller. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, Gaston. 1883. Étude sur la Table Ronde: Lancelot du Lac, Le Conte de la Charrette. Romania 12: 459–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, Matthew. 1877. Chronica Majora. In Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores. Edited by Henry Richards Luard. London: Longman and Co., vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, Linda. 2018. Singing the Crusades: French and Occitan Lyric Responses to the Crusading Movements, 1137–1336. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera. 2023. Chiasm in Choros: The Dance of Inspirited Bodies. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 14: 315–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perriman, Wendy. 2009. Willa Cather and the Dance: “A Most Satisfying Elegance.”. Madison and Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Guy. 2013. John of Brienne King of Jerusalem, Emperor of Constantinople, c. 1175–1237. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Guy. 2018. The Briennes: The Rise and Fall of a Champenois Dynasty in the Age of the Crusades, c. 950–1356. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petipa, Marius. 1975–1976. Raymonda: Scenario by Marius Petipa. Translated by Debra Goldman. Ballet Review 5: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, Marco, and Rustichello of Pisa. 2016. The Description of the World. Edited and Translated by Sharon Kinoshita. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, Marco, and Rustichello of Pisa. 2019. Le Devisement du monde: Version franco-italienne. Edited and Translated by Joël Blanchard, Michel Quereuil, and Thomas Tanase. Geneva: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, V. K. 2017. Baroque Relations: Performing Gold and Silver in Daniel Rabel’s Ballets of the Americas. In The Oxford Handbook of Reenactment. Edited by Mark Franko. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabzadeh, Shokoofeh. 2019. The Depoliticized Saracen and Muslim Erasure. Literature Compass 16: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, Nancy. 2006. Picturing the Story of Chivalry in Jacques Bretel’s Tournoi de Chauvency (Oxford, Bodleian MS Douce 308). In Tributes to Jonathan J.G. Alexander: The Making and Meaning of Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts. Edited by Susan L’Engle and Gerald B. Guest. London: Harvey Miller, pp. 341–52. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Dwight. 2017. The Qiyān of Al-Andalus. In Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History. Edited by Matthew Gordon and Kathryn Hain. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 100–23. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Adeline. 2007. Raymonda: Le Moyen Âge dans le ballet académique. In Images du Moyen Âge. Edited by Isabelle Durand-le-Guern. Rennes: Presses universitaire de Rennes, pp. 277–86. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Kristina. 2009. Singing Slave Girls (Qiyan) of the Abbasid Court in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. In Children in Slavery through the Ages. Edited by Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers and Joseph Miller. Athens: Ohio University Press, pp. 105–18. [Google Scholar]

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. 2011. Crusades: Christianity and Islam. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Sanjoy. 2022. English National Ballet: Raymonda Review—A Bold, Lavish Refit of the Petipa Classic. The Guardian. January 19. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/jan/19/english-national-ballet-raymonda-review-a-bold-lavish-refit-of-the-petipa-classic (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Runciman, Steven. 1989. A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David. 2010. Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration. New Haven: Yale Univerity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scholl, Tim. 2004. Sleeping Beauty: A Legend in Progress. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, Anthony. 2014. The Dangerous Lives of Public Performers: Dancing, Sex, and Entertainment in the Islamic World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sturges, Robert. 2015. Race, Sex, Slavery: Reading Fanon with Aucassin et Nicolette. postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 6: 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, Kaya, Julia Schleck, and Justin Stearns. 2021. Orientalism Revisited: A Conversation Across the Disciplines. Exemplaria: Medieval, Early Modern, Theory 33: 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Mark. 2000. The Cansos of the Troubadour Marcabru: Critical Texts and a Commentary. Romania 118: 336–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, Michele. 2001. The Middle Eastern Influence on Late Medieval Italian Dances: Origins of the 29987 Istampittas. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan, John. 2002. Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tronca, Donatella. 2021. Spumansque ore Lymphatico Bacchandus: Dancing in the Christian Iberian Peninsula in Late Antiquity. Hispania Sacra 73: 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, Maria del Mar. 2019. The Painted Ceiling of Santa Maria de Llíria and its Dancing Images. Early Music 47: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van D’Elden, Stephanie Cain. 1995. The Minnesingers. In A Handbook of the Troubadours. Edited by F. R. P. Akehurst and Judith Davis. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 262–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, David. 1975–1976. Nureyev’s Raymonda. Ballet Review 5: 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Voekle, William, and Susan L’Engle. 1998. Illuminated Manuscripts: Treasures of the Pierpont Morgan Library. New York: Abbeville Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wacks, David. 2013. María Rosa Menocal’s Ornament of the World, Courtly Poetry, and Modern Nationalism. Guest Lecture at New York University. October 28. Available online: https://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/2013/10/28/menocal/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Weiss, Daniel. 1998a. Art and Crusade in the Age of Saint Louis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Daniel. 1998b. Kreuzritterbible = The Morgan Crusader Bible = La Bible des croisades. Lucerne: Facsimile Verlag Luzern. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein, Jacques. 1974. Mezura: L’Idéal des Troubadours, Son Essence et ses Aspects. Geneva: Slatkine Reprints. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, Cord. 2019. Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-Thinking. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Roland. 2007. A Century of Russian Ballet: Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, 1810–1910. Alton: Dance Books. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wollesen, Jens. 2013. East Meets West and the Problem with Those Pictures. In East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: Transcultural Experiences in the Premodern World. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 341–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitler, Barbara. 1997. ‘Sinful Sons, Falsifiers of the Christian Faith’: The Depiction of Muslims in a Crusader Manuscript. Mediterranean Historical Review 12: 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, François. 1989. Toward a Delimitation of the Trobairitz Corpus. In The Voice of the Trobairitz: Perspectives on the Women Troubadours. Edited by William Paden. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dickason, K.E. Saltatory Spectacles: (Pre)Colonialism, Travel, and Ancestral Lyric in the Middle Ages and Raymonda. Arts 2025, 14, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050101

Dickason KE. Saltatory Spectacles: (Pre)Colonialism, Travel, and Ancestral Lyric in the Middle Ages and Raymonda. Arts. 2025; 14(5):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050101

Chicago/Turabian StyleDickason, Kathryn Emily. 2025. "Saltatory Spectacles: (Pre)Colonialism, Travel, and Ancestral Lyric in the Middle Ages and Raymonda" Arts 14, no. 5: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050101

APA StyleDickason, K. E. (2025). Saltatory Spectacles: (Pre)Colonialism, Travel, and Ancestral Lyric in the Middle Ages and Raymonda. Arts, 14(5), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050101