Abstract

Since 1992, we have promoted the use of descriptions from ethnographic data, including ancient, surviving oral traditions, to aid in explaining the iconography portrayed in pictographs and petroglyphs found in Missouri, particularly those at Picture Cave. The literature to which we refer is from American Indian groups related linguistically and connected to the pre-Columbian inhabitants of Missouri. In addition, we have had on-going conversations with many elder tribal members of the Dhegiha Sioux language group (including the Osage, Quapaw, and Kansa (the Ponca and Omaha are also part of this cognate linguistic group)). With the copious collections of southern Siouan ethnographic accounts, we have been able to explain salient features in the iconography of several of the detailed rock art motifs and vignettes, and propose interpretations. This Midwest region is part of the Cahokia interaction sphere, an area that displays western Mississippian symbolism associated with that found in Missouri rock art as well as on pottery, shell, and copper.

Keywords:

rock art; ritual; Missouri; American Indian oral traditions; iconography; petroglyphs; pictographs 1. Introduction

Picture Cave is absolutely unique. Rarely does one run into rock art imagery as complex and kinetic as that found in Picture Cave, with its over 300 images. The ridge below which Picture Cave is located resembles a “sleeping woman” with her head to the northeast. The cave is secluded, layered, and it ends in a large “sink-hole.” It is analogous to the Dhegiha cosmic model (Duncan 2011, pp. 18–33). This paper will illustrate and discuss six separate ritual themes that are depicted on the walls of this remarkable cave. Picture Cave, located in east-central Missouri, is only a day’s journey by canoe from the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. Sadly, the cave was first found by collectors and looters who ransacked its archaeological deposits. This happened long before it came to the attention of professionals (Watson 2015, pp. xv–xvi). Graffiti dates on the cave walls go back to the mid-1800s.

As a very brief background, we offer the following: From 1991 to 2010, with the landowner’s permission and presence, we worked on recording the imagery on the walls at Picture Cave. Being a dark zone cave, the work was both difficult and challenging. The upper, sandstone cave has several vertical walls. These sparkling, iron-stained surfaces provided a canvas for the ancient art work depicting events in the primordial night sky, the uppermost layer of the Lower Worlds (Duncan 2015, p. 210). In 1996 we obtained a grant that enabled us to hire analytical chemists to date the black pigments in three of the major pictographs. The weighted average for all three images turned out to be A.D. 1025 (Diaz-Granados et al. 2001). In 1997, a fourth pictograph was sampled and that sample was sent to the same analytical chemists. That 4th sample resulted in a comparable date. Our research continued.

In 2004, a second grant was finally obtained to bring to the cave a group of seven archaeologists,1 a folklorist, two professional artists, a museum curator, and five members of the Osage Nation (Diaz-Granados et al. 2015; Diaz-Granados 2023, pp. 3–7). Joining this core group were cavers from the senior author’s local grotto who were assisting the invited individuals, a graduate student specializing in analytical chemistry, a professional videographer, and the landowners. This endeavor was aptly titled “The Picture Cave Interdisciplinary Project” (2005–2008). As a result of this major project, a symposium was organized by the project’s director. Papers were presented in 2006 at the Southeastern Archaeological Conference in Little Rock, Arkansas. Those papers became the basis for a major, full-color edited volume published by the University of Texas Press in 2015 and titled PICTURE CAVE: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos.

The many detailed images at Picture Cave, plus the symbols, some with obvious early Mississippian iconography, inspired the junior author, Jim Duncan, to research Siouan oral traditions that had the potential to shed light on the symbolism. Duncan began reading anything and everything he could find on ethnographic discussions and oral traditions of the American Indians known to have inhabited the region surrounding Picture Cave, primarily the Dhegiha Sioux speakers and their related nations. However, the Dhegiha, especially the Osage, are secretive about their religion. According to a young French medical doctor who lived among them in 1840, “It is shrouded in darkness” (Tixier 1940, pp. 229–30). This certainly meshes with Picture Cave and its secluded location. Being of Osage heritage, he was already quite knowledgeable with Osage culture. Then, in 1993, we were invited to attend the summer ceremonial dances on the Osage Reservation. This opened up a world of new friendships including elders who were knowledgeable regarding the old ways and oral traditions of their ancestors. This, in large part, along with a tremendous amount of reading, enabled us to tie together the iconography of a selection of the detailed pictographs with the oral traditions, ceremonies, and rituals uncovered.

2. Dancer with a Willow Branch

One of the most meaningful visual metaphors is a small, silhouette-style figure in a dance posture (Figure 1). This little kinetic figure, just 10 cm tall, is filled with meaning that defines the founding of the majestic mound groups at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers (Duncan 2015, p. 225). A clue to its significance can be found in the “willow branch” it is holding as it dances. We will explain this ritual in more detail further along.

Figure 1.

Dancer with a willow branch (photo courtesy of Alan Cressler).

During Late Woodland times, the groups surrounding the confluence region often built hamlets on prominent elevations near major streams with wetlands and rich, alluvial silt/loam soils. Many of these habitation sites became larger and more complex over time. Multiple burial mounds were added, often adjacent to an open social area similar to modern dance grounds, i.e., a plaza with a focal point—a single pole—erected in the center. Unfortunately, many of the mounds have been looted over the past two centuries. In some cases, rather than spectacular funerary offerings, the major effort expended for the honored dead seemed to be the burial mounds themselves. Nevertheless, occasional marine shell beads, elaborate chert arrow points, small cup-like ceramic vessels, and simple, elbow shaped clay or stone tobacco pipes accompanied these burials. Fortunately, formal excavations by trained teams of salvage archaeologists contributed new dimensions to some of these sites. The houses appear to have been breezy summer thatched or mat covered, as well as some sturdy semi-subterranean structures of poles and sod with multiple storage pits and central hearths for cooking and warmth. Evidence of woven mats on floors and even gardening tools have been found in many of the house structures, especially those that were burned, as thatch and mats are quite flammable. In some of the larger villages, urban planning was practiced with the presence of a stockade to protect the town and occasional larger public structures, adjacent to the unoccupied plaza. It is the isolated and centered post that we believe was so important in the Western Mississippian (and possibly earlier in the Late Woodland) iconography of Picture Cave.

During the collecting of ethnographic data in the late nineteenth century by Alice Fletcher and Francis LaFlesche, the ritual center post’s definition was recorded for posterity. This all-important centering of a cottonwood, red willow or cedar pole, by the ancestral Dhegiha who referred to it as The Sacred Pole, Waxthe’xe or “The Venerable Man;” these poles were universal among all bands (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 217–60). These poles have great depth to their meaning and importance among the five cognate tribes: the Osage, Omaha, Ponca, Kansas, and Quapaw. In fact, they appear to be foundational ritual objects with these Dhegiha Sioux-speaking people.

As the many surrounding groups of Late Woodland people focused their gatherings at the confluence region, a population coalescence resulted, due in part to the protection that sheer numbers afforded the participants. Feeding these people was likely the responsibility of the women aided by a sustainable agricultural system involving seed exchanges and companion plantings that had been previously developed. The rapidly increasing populations quickly reached a density that encouraged the construction of ritual monuments of enormous size. These monuments incorporated earlier patterns and symbols, particularly the Sacred Poles. The size of these religious monuments, erected on the three sites at the confluence, make them unique. They resemble the monumental architecture of early, principal ceremonial centers in Mesoamerica, especially the western Mound City group in St. Louis, and the eastern group at Cahokia.

The Mound City and Cahokia centers not only drew many visitors in ancient times, but their immense size impacted and resonated over great distances and for many centuries. The Sacred Poles were probably the focus of a joyous ritual, the Dhegiha He’diwache, where the entire population danced around the poles bearing red willow branches in celebration of the UNITY and the dismissal of fear of attack by large foreign tribal groups. These poles had several levels of ritual significance. For example, the poles signified abundant life, large families secure from attacks, and the commonality of tribal honors and ethical behavior without oppression. The poles were painted with red and black stripes signifying the orderly passage of time. These striped poles are still used in the Osage Native American Churches. Young men dug the holes, centering the poles, and heaping the earth from the excavation into a small mound to the east of each pole. Between this mound and the pole, the sacred symbol, the uzhin’ eti (U’ze), or First Woman’s vulva, was incised on the ground. This represented the all-important portal of birth–death–rebirth of all living beings (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 254–55). As a symbolic metaphor, the little dancing figure at Picture Cave likely carries a powerful message of unity, stability, and rebirth, present at the great mound sites near the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers!

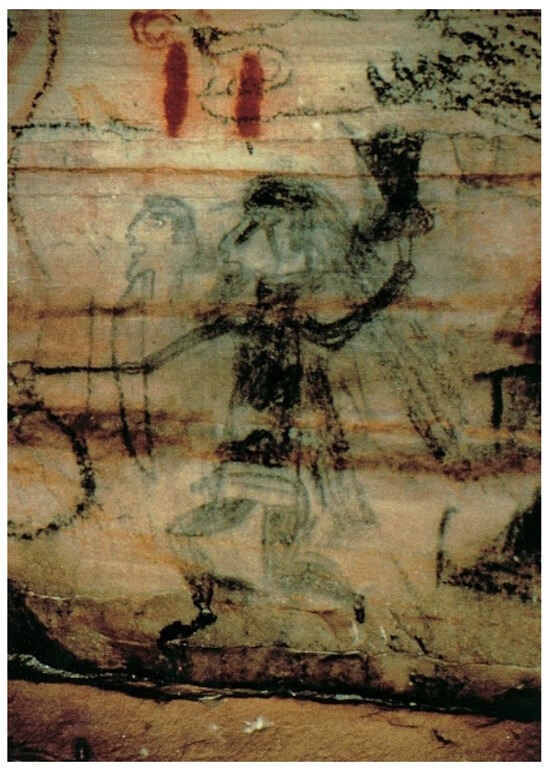

3. The Black Warrior at Picture Cave

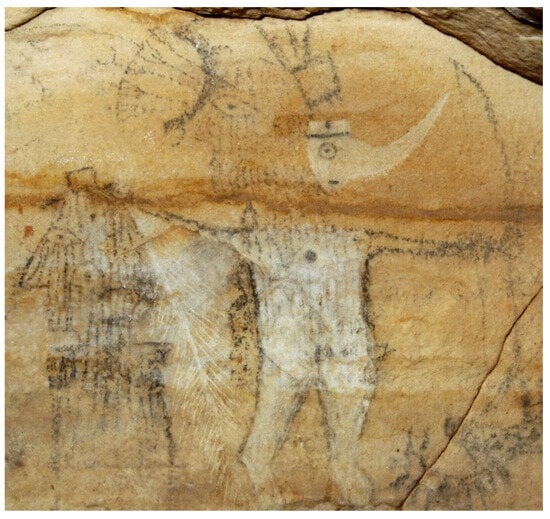

One of the most detailed images on the walls at Picture Cave is one we referred to as The Black Warrior (Duncan et al. 2015, pp. 125–31). We may continue to use this appropriate description, because the figure is almost entirely drawn in black carbon pigment (Figure 2). A primary reason for its importance is its congruence with the Rogan plates found in Mound C, at Etowah, Georgia (King 2004, p. 150). It was these two repoussé copper plates that inspired Herbert J. Spinden to write the initial paper describing a “Warrior Cult,” the earliest description of what was later described as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (1931) (Spinden 1931). This cultural complex has long been the center of an intense scholarly effort involving many of the principal archaeological researchers engaged in defining the last major Pre-Columbian cultural manifestation in the eastern United States (Lankford et al. 2011, pp. xi–xviii; King 2007, pp. 1–14, among others).

Figure 2.

The Black Warrior (photo courtesy of Jim Duncan).

The Black Warrior is depicted in a dance pose, with his right leg raised and his left foot on the ground projecting his body forward. His left arm is raised, holding an oversized symmetrical, crowned mace or war club. This early style of war club is strongly associated with a particular artistic style, the Braden style; this form is retained as a metaphor and is seen used as a symbolic tattoo until the mid-nineteenth century (Phillips and Brown 1978, p. 153; Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, p. 507). The Black Warrior’s face is not filled with black pigment. It is in profile with an exceptional amount of attention to profile and facial painting. His left eye is carefully rendered with a prominent iris and a painted eye surround, a raptor’s forked eye markings. The most unusual feature of his face is a prominent chin goatee. We have seen this unusual feature on the portrait of a Ponca “band leader” by Bodmer painted in the 1830s. Carefully drawn in front of the Black Warrior’s face is an unpainted face of an identical being without adornment or goatee. This probably represents his older twin brother called “Stone”, as described in “The Omaha Tribe.” During the night, The Celestial Twins trade roles, and Stone then becomes the judge of souls, being represented by the star Deneb, where the Milky Way divides (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 171–72; Charles Pratt 2008: pc).

On the Black Warrior’s head is a “bandeau” style headdress with an elaborate mass of trailers. They no doubt represent either painted hide or woven materials streaming down his back. His right hand holds what looks to be a self-bow with a nocked arrow in place at the ready. On his abdomen is a horizontal unpainted, “butterfly” design, a “War Honor” found tattooed on Osage women in the 19th century (Dye 2013, p. 224). With the exception of moccasins, an elaborate woven sash and the spectacular bandeau style headdress with trailers, the warrior is otherwise unclothed. The famous painting of the Villasur Massacre of 1721 shows Plains/Prairie warriors identically depicted, heavily painted and armed, but otherwise naked.

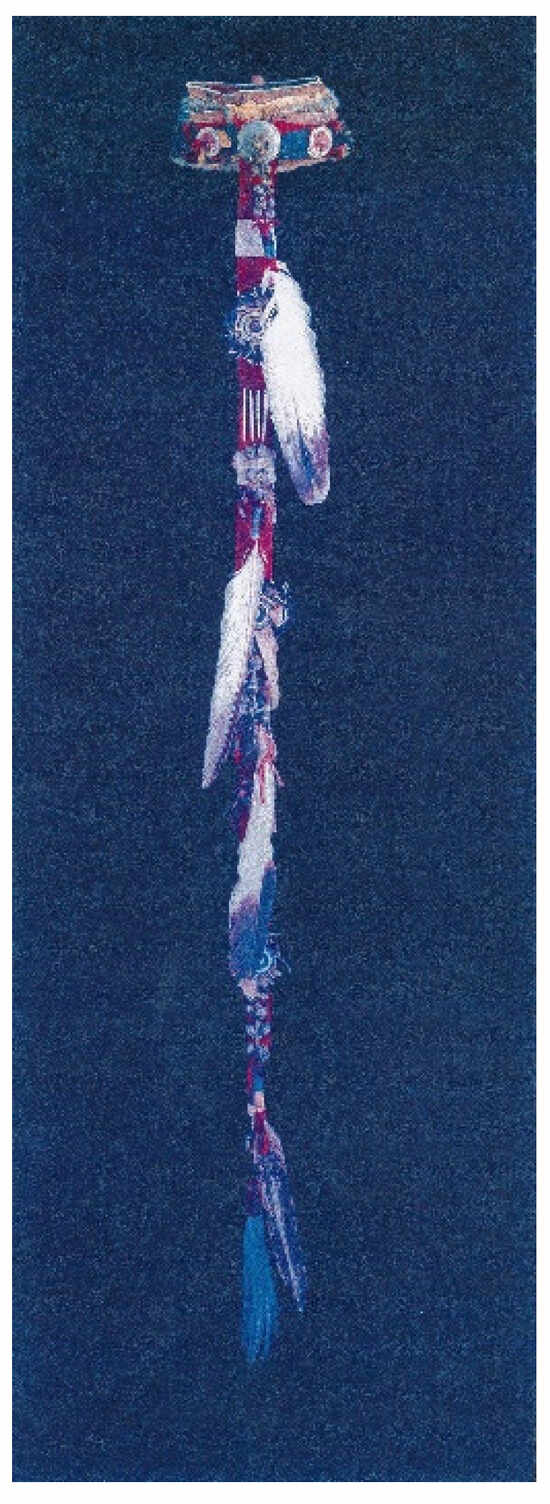

Later readings of ethnographic accounts have brought to our attention that he may likely represent a supernatural being in the realm of Dhegiha iconography: The Dark Wolf. This important image was pigment dated (Diaz-Granados et al. 2015, p. 54) with a weighted average of A.D. 1025. The “Black Warrior,” or Dark Wolf, wears a headdress with an extensive description in its museum accession file (Diaz-Granados et al. 2015, p. 127). Both William Samuel Fletcher and Charles Pratt corroborated the name and role of this figure with his distinctive headdress. They recognized the headdress as extremely similar to an example present at the Osage Nation Museum (Figure 3) that represents warrior honors in the trailers such as those worn by a priest of the “Men of Mystery” clan. A similar hat, made of an animal pelt, is depicted on a figure engraved on the famous Braden A Stovall cup from the incredible shell cup horde deposited in the Spirit Lodge and Great Mortuary found in the Craig Mound at Spiro, Oklahoma (Phillips and Brown 1978, plate 6).

Figure 3.

Osage Headdress, Osage Nation Museum.

With corroboration by Osage elder William Samuel Fletcher, his definition of his Great Grandfather’s name gave this figure the title of “The Dark Wolf,” the youngest of the Celestial Twins (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, p. 173). As the Dark Wolf, The Man-of-Mystery, this spirit being selects those warriors who are to die in battle. He is the youngest of the Celestial Twins, and his older brother is “The Stone” (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, p. 173). In the Dhegiha pantheon of powerful spirit ancestors, the Celestial Twins are the twin sons of Evening Star, Morning Star’s eldest sister. These two boys are also known as “Children of the Sun,” and they are the saviors of humankind and the world! They are described as the most powerful spirit beings in the Ho-Chunk cycles of oral traditions (Radin 1954, p. 103). One of the most thorough of the oral traditions describing the Celestial Twins was collected by J. O. Dorsey in the late nineteenth century from the Caddo (Lankford 1987, pp. 165–73). This Caddo version is probably quite similar to the Dhegiha versions, which exist only as fragments (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 171–72).

Combining these versions of the two oral traditions makes sense simply because these cultural groups were neighbors and not all interaction was warlike; they also cooperated, especially uniting against threats common to both. Using one story to support or corroborate a less complete version is logical. Viewing the Dhegiha–Caddoan traditions, the twin celestial Thunder Beings are the most powerful spirit beings, and they alone defeat the Water Spirits by rescuing and healing First Man and Morning Star, as well as all of humankind. Lankford states that the oral traditions embracing the Celestial Twins are the most widespread among American Indian groups (Lankford 1987, p. 170). The Dhegiha especially seek the Celestial Twins during rites of vigil. The twins impart ethical information that is vital in advancing the vision seeker’s station in Dhegiha society.

The Genesis family, First Man, First Woman, and their six supernatural children, their descendant clans, indicate a stratified society, a hierarchy. However, young men who display bravery, empathy, generosity, and familiarity with ritual and lore are supported by the women who are the corporate (clan) production engineers (Bowers 2004, p. 94). These men, especially those with leadership abilities who fit the paradigm set forth by Picture Cave’s narration, attain stature and honor to this day.

4. The Three Musicians at Picture Cave

One of the most interesting silhouette styles of anthropomorphic figures at Picture Cave is the trio of three figures engaged in chanting or singing (Townsend 2015, p. 155). From the morphology, especially the occipital hair buns on each of the three, we are looking at males (Figure 4). The figure on the right appears to be shaking a raised gourd rattle. The center figure and the figure on the left are possibly singing or chanting probably in a ritual or ritual accompaniment. While curiously detailed for silhouettes, this little group is only 10 cm. tall and 12 cm. wide. The figures are skillfully rendered, in their obvious squatting positions.

Figure 4.

The Three Musicians (courtesy of Jim Duncan).

The Osage Native American Church (ONAC) has only four remaining family- or clan-related churches at the time of writing this chapter. The second author on this paper is a member of the ONAC. He recounts that the meetings begin with a meal and end with a meal. The service lasts 15 h and the only musical instruments used are gourd rattles and a small water drum. These rituals are quite ancient, possibly going back to Middle Woodland times. Evidence of gourd rattles, sets of ceramic vessels or marine shell cups, for drinking complex botanical teas along with ceramic water drum paraphernalia have been found in Middle Woodland mortuary context (Lepper 2018, pp. 1–5).

If the trio is not engaged in a ritual celebrating the rebirth of Hawk or Morning Star, what might they be doing? Several persons using gourd rattles and chanting are also found during another important and ancient social rite called the “Hand Game.” So, we venture to offer that the trio, if not depicting a resurrection ritual, may be engaged in a hand game. The hand game involves the hiding of a large bead in either of the hands. This game involves singing, complicated hand movements where one person tries to keep another from correctly guessing which hand, right or left, conceals a large bead. The opposing team indicates the suspected hand by pointing with a small, decorated wand. Points are awarded by correctly guessing or clever manipulation and incorrect guesses. Points are kept by small willow counting sticks until a limit has been reached. The participants gamble apparel, footwear, robes, blankets, jewelry, anything of value including oneself. Fragmentary stories where clever heroes trick powerful but slow-witted spirit adversaries are not uncommon in the lore of plains/prairie nations.

We suspect that after his adoption and a feast provided by First Woman, her two grandsons engage the Great Serpent in a friendly hand game or two, winning some of his valuable possessions. Also, the Great Serpent engages in the all-important ritual of “Walking with the Buffalo” where he has sexual intercourse with First Woman. After coitus she gifts him for his life -giving power that she now possesses, as a sacred vessel. Since First Woman is the spirit of the earth, her vulva becomes the great portal, the portal of birth, death and rebirth.

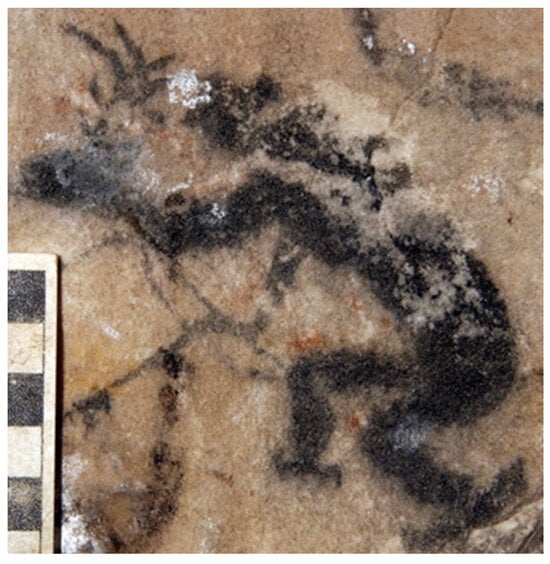

5. Morning Star or Hawk

This vignette, a well-known celestial ritual, was placed on a carefully selected, small sheltered panel with horizontal fissures and bright, strong reddish iron-oxide staining. The figure, its face in profile, is cleverly placed above the iron-oxide-stained fissure that resembles the earth’s horizon at sunrise. The artist, with great control, first engraved the composition into the sandstone. The figure’s limbs and body below the chin were then abraded exposing the glistening white sandstone matrix beneath the reddish iron-oxide-stained surface. This was a clever move on the part of the artist and one that gives the viewer the false impression that they are seeing “white pigment” in various places of the composition.

Not only is this image the most important, it is probably the oldest, dating back to the terminal Late Woodland period (Figure 5). The style in which it is rendered is much different than any of the other images. A section of Picture Cave’s vertical sandstone wall, with horizontal fissures and varying degrees of red, iron-oxide staining was carefully selected. The outline of the figure was engraved into the sandstone with a sharp, possibly chert or quartz, burin. The entire body below the neck, and the significant ear adornment were carefully abraded, exposing the glistening white sandstone matrix. Using a fine brush and black paint, myriad anatomical details, tattoos, and apparel were painted on the gleaming white sandstone areas.

Figure 5.

Morning Star or Hawk (courtesy of Jim Duncan).

The figure’s hair braid is tightly wound into a bun on the back of the head and held with three pins. Worn on the back is either a cape or possibly a long lock of his own hair. There can be no doubt, this is a powerful and widespread spirit being, called Morning Star, Hawk, or the Symbolic Man (LaFlesche in Bailey 1995, p. 78)! Morning Star’s face and torso are covered by fine parallel lines, thirteen of them, representing the primal rays of a rising Sun. These thirteen rays also represent the war honors that can be accomplished by a Dhegiha warrior (Bailey 1995, pp. 80–81). Morning Star holds in his right hand the head of his father, the Sun, raising him up from the horizon exposing his face, neck, and upper torso. The Sun is painted with the same thirteen parallel lines as the son (Morning Star); the Sun also has an “eye” on his cheek and on his chest, a metaphor for him being an asterism in the sky (Krutak 2013, p. 133). In Morning Star’s left hand is a recurved bow and two arrows. Morning Star’s spectacular ear adornment, a gleaming white shell Long-nosed maskette, not only reminds one that he has thunder power, it also ensures the presence of his nephews, the Celestial Twins, who sustain him. On his chest he is marked with an “eye,” his locative, identifying him as a sky spirit; this symbol is polysemous having the same meaning as a dot-in-diamond or a four-pointed star.

Morning Star’s most enigmatic adornment is the forehead plaque he wears. This plaque is shown in a side view, and it is pierced by five arrows signifying that he has passed, as a holy arrow or lightening, through the portals of the four beneath worlds. Finally, the Earth’s or First Woman’s vulva, often called the “ogee,” the great portal of rebirth, is depicted in the center of this forehead plaque (Phillips and Brown 1978, p. 154; Brown 2007, pp. 99, 106). This passage by The Symbolic Man through the five portals is still celebrated in the remaining Osage Native American Churches, during their night ritual.

This portal, First Woman’s vulva, is displayed on the forehead plaque of a Red Missouri Flint Clay pipe that was found in the Spirit Lodge at the Craig Mound in Spiro, Oklahoma (Reilly 2004, p. 132; Reilly and Garber 2007, pp. 99, 106). This incredible sculpture was called the Big Boy Pipe, but it is now referred to as the Resting Warrior; it represents Morning Star, the eldest son of First Man and First Woman (Ponziglione 1897, pp. 11–17). Two of the figure’s defining attributes are his short-nosed maskette ear ornament and his woven, attached side braid. The very masterful Picture Cave artist brought into play, with a fine brush and black paint, all of the remaining details. Morning Star holds the Sun, his father, whose body is emerging from its birthplace, the Earth’s U’ze (vulva); this scene is a metaphor for the genesis story’s first sunrise.

This “ritual of genesis” portrayed in this vignette, is very possibly the earliest depiction in the cave. It might also be connected to a special solar phenomenon, a total solar eclipse at sunrise. This happened in A.D. 941, just at the transition period from Terminal Late Woodland to Early Western Mississippian (Duncan 2015, p. 227). The ancient Dhegiha priests leading the morning prayers would have seen the fiery “hole in the sky”, with a dazzling bright Morning Star above it, slowly rise up on the horizon, with the Sun gradually being born again! One is also reminded of the polished freshwater naiad shell gorgets worn by most Osage male dancers, and the meaning of these gorgets: “As the Sun is reborn every morning, so shall our spirits be reborn,” (Charles Pratt, 2005, pc).

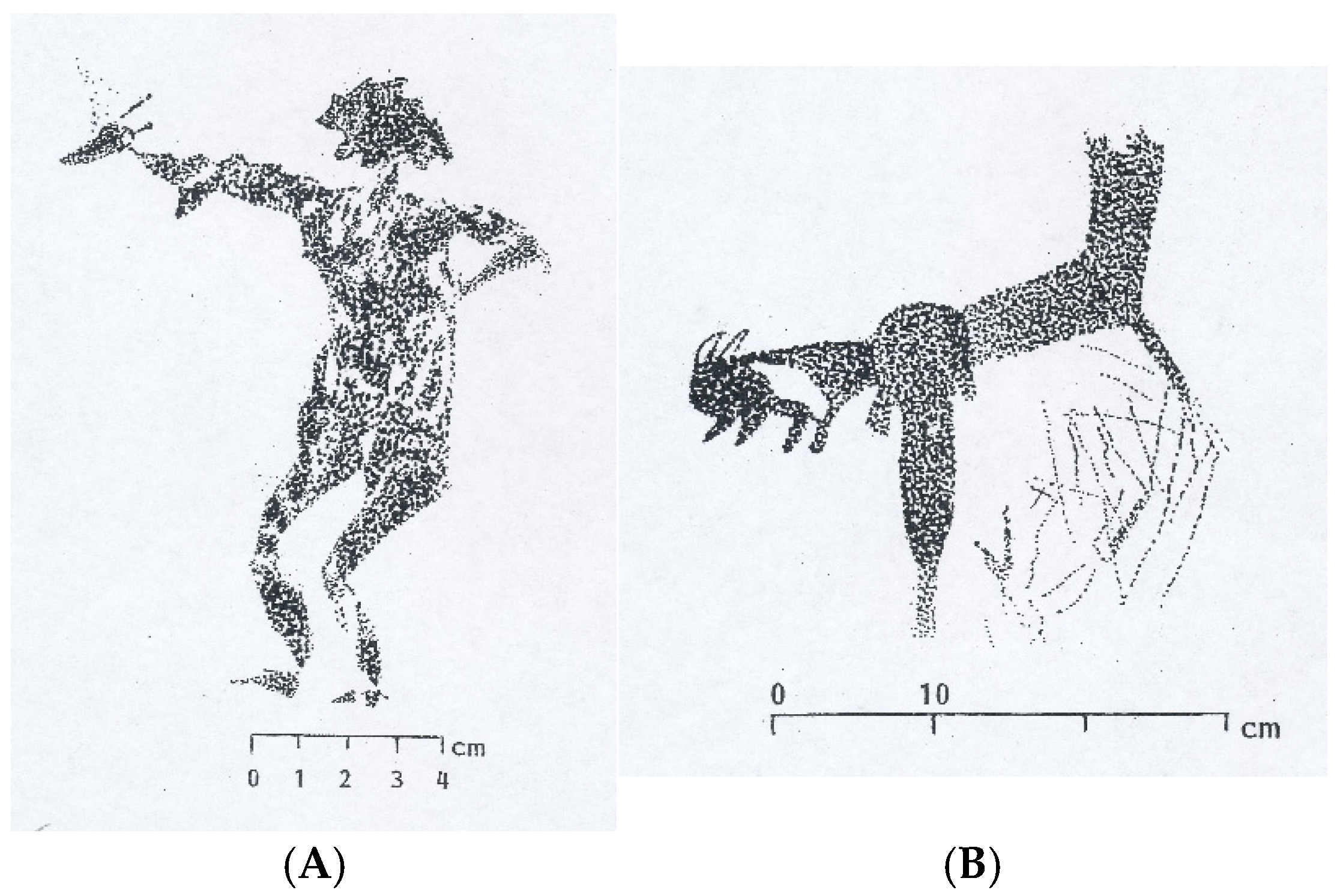

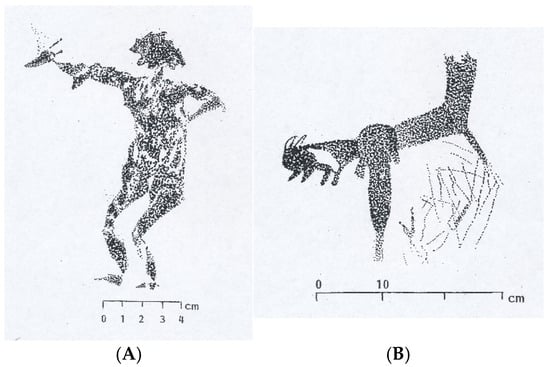

6. A. and B. Figures with a Hand Turning into an Animal

Perhaps the most enigmatic imagery at Picture Cave is found in two figures. In each, a hand appears to be turning into an animal. The first is a small silhouette-style figure with an unusual bent-knee stance. The figure is not dancing or running; it is standing with bent knees, facing forward, or facing west, with what looks to be a horned animal head where the right hand should be (Figure 6A). The identity of this figure is rather enigmatic. After a lot of thought, giving attention to the location, in the west of the night sky, we believe this figure is a rare image of First Woman or Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies. The animal head may be a young male deer, the first to come down from the sky, a symbol of life and sustenance for the Osage (Bailey 1995, pp. 235–37). Thus, First Woman introduces a ritual of transformation, the first animal life, onto her newly created Earth.

Figure 6.

(A) Figure with hand turning into an animal (drawing by Jim Duncan). (B) Arm and hand emerging from cave wall (drawing by Jim Duncan).

It became evident from the Osage Genesis oral tradition recorded in the mid-nineteenth century that the very first member of the six children of First Woman was the youngest daughter, Ci-ge, who found the cave on the seventh day of her vision quest (Ponziglione 1897, p. 13). This primacy, an honor, cemented the proper place of women in the dichotomous Osage society. Her quest was answered and she gained great knowledge about bringing forth life, both in her gardens and from her body. This great gift echoed throughout the Western Mississippian world.

The second depiction of a hand turning into an animal occurs in panel 5. Here we find the disembodied arm (and leg) of a large figure. The arm is totally in black (and the leg is drawn in black), and it appears that this figure from “the other world” is crawling out of a large fissure between the ceiling and the wall (Figure 6B). The arm is not a human arm; it belongs to a powerful spirit being called Sharp Elbow, or Double Face. Sharp Elbow, also known as Long Arm among the Hidatsa, belongs to a retinue of night beings who assail the Celestial Family. It is Sharp Elbow who kills Evening Star in the oral traditions. When Evening Star was pregnant with the Celestial Twins, Stone and Dark Wolf, Sharp Elbow and his ilk visit her lodge while her brother Morning Star is out hunting. Evening Star feeds Sharp Elbow, who then kills her for an imagined insult. Sharp Elbow also catches Dark Wolf and attempts to torture him but loses his arm when the Celestial Twins turn the tables, cutting it off (Bowers 1992, pp. 312–20)!

Picture Cave’s Sharp Elbow makes amends as a captive of the two Celestial Twins when they overcome the Water Spirits and return their father’s head, the Sun, to their Grandmother to be resurrected. There is a carefully painted animal (otter?) skin medicine bag on Sharp Elbow’s arm. As part of a ritual, this medicine bag could contain the powerful medicines that have the power to resurrect Evening Star. This scenario is replicated by the Dhegiha Shell Society. Members of this society are healers; they carry otter hide medicine bags, and the practice of “shooting and resurrection” ritually occurs among the members. Both men and women can belong to this society (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 509–65).

Picture Cave was so important to the Dhegiha, especially the Osage, that they spoke of its existence and the Genesis story to the Jesuit Priest Fr. Ponziglione in the 1850s, while still living on their Kansas Reservation (Ponziglione 1897, pp. 19–24). It is from his voluminous, carefully written notes that we know of the “ancestral” Celestial Family and their connection to astral bodies (Duncan and Diaz-Granados 2004, p. 202). Most importantly, because this well-educated Jesuit so admired and respected the Osage people, he learned their language and left a partial dictionary that preserves a portion of the Dhegiha language as it existed prior to the Osage removal to Oklahoma. This removal hastened the deterioration and almost caused the loss of their rich, ancient heritage. What we have gleaned from this Jesuit’s records is that the Osage recognized that their ancestry was rooted in the Celestial Family, and that these ancestral spirits could manifest themselves as spirit beings. The seminal Braden style imagery, depicting these same spirit beings makes up the majority of the Picture Cave’s kinetic vignettes illustrating the “Mon-thin-ka Gaxe,” the Making of the Earth ritual (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, p. 171).

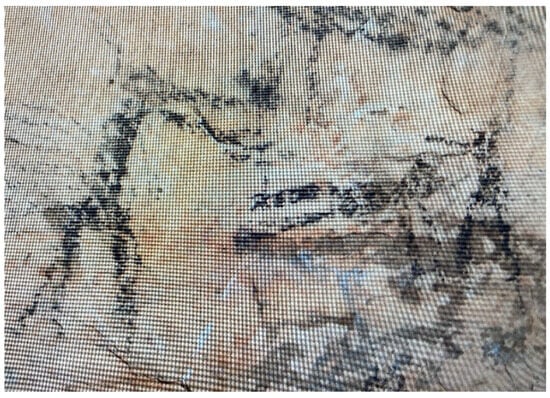

7. Healing and Resurrection

The drawings on the walls at Picture Cave are among the most detailed found in the Midwest and Eastern Woodlands. Five such images have been discussed above. The last two images we wish to discuss are anything but detailed. They are crudely drawn—one is rendered in dark charcoal (Figure 7), while the second is extremely faded and very light gray in appearance (Diaz-Granados et al. 2015, pp. 184–85, Figures 14.3 and 14.4). In spite of their crude renderings, we believe these images to be very significant and telling of an important ritual. At its most basic, it portrays the ritual of healing, and beyond that, possibly an image attempting and portraying resurrection and reincarnation! Although some may call these two, similar, images “enigmatic,” we think we can understand what is taking place in both vignettes, or at least understand the intent in the imagery.

Figure 7.

Scene of healing or resurrection or rebirth (photo courtesy of Alan Cressler).

The Dhegiha had many medical personnel among the bands. Over the years we have heard of doctoring procedures using massage, bathing, poultices, herbal teas, and the actual demonstration of the use of medicinal plants by elders. Healing is also practiced in the Osage Native American Church, during meetings and especially just before sunrise. However, what is depicted at Picture Cave is beyond the roles of herbalists and church meetings.

In both depictions, there is an obvious figure lying flat on a horizontal surface. Positioned at either end are figures, or a figure, with arms stretched out over the prone figure, as if conjuring either wellness or their spirit. Within the darker image (Figure 7), the standing figures at either end with their arms outstretched over the prone figure, possibly indicate a ritual of healing or resurrection. Granted, this may, as in most other cases in Picture Cave, refer to an other-worldly ritual event taking place. On the other hand, it could also serve as the depiction of an actual earthly ritual in progress. In the lighter image, only one figure is present and to the right. That figure is in a partial squatting position with arms over the prone figure. Later additions of charcoal markings to this lighter image may obscure a figure to the left. This is one of many examples of layering or palimpsest within the Picture Cave corpus of imagery.

The founding oral tradition of the Shell Society involves the death of four children who are painted by a mysterious visitor, a “Giant Animal” in human form, the chief of the Water Spirits (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, pp. 509–15). Through a complex ritual of painting and singing, the dead children are readied for their journey. After some time, the grieving parents are shown the children, happy and beautiful, cognizant and waving, looking through a misty portal in the Lower or Beneath World. The Dhegiha do not believe in a multiplicity of souls, human beings have only one soul (Fletcher and LaFlesche [1911] 1992, p. 589; Bailey 1995, p. 282). The souls of the dead travel the path of the Milky Way, to a seven-layered spirit world where relatives are united.

These images hold great power and importance, they are ideographic and they are connected to the major theme of Picture Cave—genesis. To see the use of the term “gods” rather than spirits or spirit beings by many early ethnographers recognizes an early bias. However, some early records do use Wa-kon-da, Old Man Immortal, First Creator, and other titles including the common, “Great Spirit.” What needs to be recognized here is simply this: the Dhegiha, and other related groups, believed in a logically arranged system of universes created by a single mysterious creative entity governed by ethical, logical universalism. The imagery in Picture Cave seems to bridge or convey, through its unique, seminal realistic depictions, stylistically referred to as Braden (Phillips and Brown 1978; Brown 2011, pp. 65–72; Diaz-Granados 2011; Duncan 2011, p. 31; Reilly 2007; and many others), a conceptual ideology, from the careful oral descriptives to a visual experience. Multiple images of the same spirit or ritual only serve to reinforce this ideology. Who could argue with the West Moon Osage Church Road Man and Elder, Charles Pratt, when he said, “Picture Cave is the Womb of the Universe?”

We want to emphasize the importance of the great and complex imagery on the walls of Picture Cave and the significance of its presence in this dark zone sanctuary. This dark zone cave emulates the night sky! The stars of the night sky represent ancestral spirit beings, as do most of the supernatural beings depicted on the walls of the cave. This sacred cave and its 300+ images were evidently created to be seen by chosen candidates for priestly rites.

8. Concluding Remarks

There was a time, not all that long ago, when archaeologists would not give petroglyphs and pictographs (also known as Rock Art) a second thought. Although we “won’t go there” in this discussion at this time, all rock art researchers know of what we speak. Then, with the advent of dating pigments in pictographs containing charred botanical materials, and a few methods to date petroglyphs, including stylistic analysis, rock art started coming into its own. About 30 years ago, and more recently in the last 10 years, a few rock art researchers have endeavored to interpret rock art imagery that is sufficiently detailed and with diagnostic motifs to allow interpretation (Watson et al. 1984, p. 274). Through the time-consuming activity of reading American Indian oral traditions, studying the ethnographic resources, and in discussions with American Indian elders, we strongly believe that an understanding of the meaning within some of the rock art panels has come within reach.

One of the most rewarding efforts that we have experienced is to assemble a “team,” of not just iconographers, but also other interested and involved specialists. The key members should include indigenous individuals, especially those whose ancestors inhabited the study area (Kehoe 2007, pp. 246–47; Diaz-Granados 2023, pp. 3–4). We have found that the indigenous members of such a multi-disciplinary effort are the most valuable in the reconstruction of past oral traditions. Over the last 200 years, industrialization as well as the re-education and assimilation of generations has been the primary agent in eradicating native ideology. We believe that helping and encouraging native peoples in reconstructing their lost lore enriches our own. Detailed rock art imagery can help in this endeavor.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, C.D.-G. and J.R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The original Picture Cave Interdisciplinary Project was funded by the Lannan Foundation through Texas State University’s Center for the Arts and Symbolism of the Ancient Americas, San Marcos, Texas.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I wish to especially thank David Whitley for inviting me to contribute a paper to the Arts Magazine’s focus volume on American Indian rock art I also wish to acknowledge my co-author, James Duncan, for his substantial contributions to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | The archaeologists invited to participate were, all but one, members of the Texas State University’s Spring Iconography Workshop, organized by Professor F. Kent Reilly III. |

References

- Bailey, Garrick A., ed. 1995. The Osage and the Invisible World: From the Works of Francis LaFlesche. Norman: University of Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Alfred W. 1992. Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organization. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Alfred W. 2004. Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, James A. 2007. On the Identity of the Birdman within Mississippian Period Art. In Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. Edited by F. Kent Reilly, III and James F. Garber. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 56–106. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, James A. 2011. The Regional Culture Signature of the Braden Art Style. In Visualizing the Sacred: Cosmic Visions, Regionalism, and the Art of the Mississippian World. Edited by George E. Lankford, F. K. Reilly, III and James F. Garber. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Granados, Carol. 2011. Early Manifestations of Mississippian Iconography in Middle Mississippian Rock Art. In Visualizing the Sacred: Cosmic Visions, Regionalism, and the Art of the Mississippian World. Edited by George E. Lankford, F. K. Reilly, III and James F. Garber. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 64–98. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Granados, Carol, ed. 2023. Explanations in Iconography: Ancient American Indian, Art, Symbol, and Meaning. London: Oxbow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Granados, Carol, James R. Duncan, and F. Kent Reilly, III, eds. 2015. PICTURE CAVE: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Granados, Carol, Marvin Rowe, Marian Hyman, and John R. Southon. 2001. AMS Radiocarbon Dates for Charcoal from Three Missouri Pictographs and their Associated Iconography: A Report. American Antiquity 66: 481–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, James R. 2011. The Cosmology of the Osage. In Visualizing the Sacred. Edited by George E. Lankford, F. K. Reilly, III and James Garber. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, James R. 2015. Identifying the Characters on the Walls of Picture Cave. In PICTURE CAVE: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados, James R. Duncan and F. Kent Reilly, III. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 209–37. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, James R., and Carol Diaz-Granados. 2004. Empowering the SECC: The Old Woman and Oral Traditions. In The Rock Art of Eastern North America: Capturing Images and Insight. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 190–215. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, James R., Marvin W. Rowe, Carol Diaz-Granados, Karen L. Steelman, and Tom Guilderson. 2015. The Black Warrior Pictograph: Dating and Interpretation. In Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados, James R. Duncan and F. Kent Reilly, III. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 125–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, David H. 2013. Snaring Life from the Stars and the Sun: Mississippian Tattooing and the Enduring Cycle of Life and Death. In Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Edited by Aaron Deter-Wolf and Carol Diaz-Granados. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 215–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, Alice, and Francis LaFlesche. 1992. The Omaha Tribe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, vols. I and II. First published 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe, Alice B. 2007. Cahokia Text and Cahokia Data. In Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 246–62. [Google Scholar]

- King, Adam. 2004. Power and the Sacred. In Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South. Edited by Richard F. Townsend and Robert V. Sharp. New Haven: Art Institute of Chicago, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 150–65. [Google Scholar]

- King, Adam. 2007. The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex: From Cult to Complex. In Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Krutak, Lars. 2013. The Art of Enchantment: Corporeal Marking and Tattooing Bundles of the Great Plains. In Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 131–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, George E. 1987. Native American Legends. American Folklore Series. Little Rock: August House Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, George E., F. Kent Reilly, III, and James F. Garber, eds. 2011. Introduction. In Visualizing the Sacred: Cosmic Visions, Regionalism, and the Art of the Mississippian World. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. xi–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Lepper, Bradley T. 2018. Insights into Hopewell Material Culture Derived from the Contemporary Ceremonial Practices of the Shawnee Tribe: A Case Study Supporting the Value of Collaborative Research with Native American Tribes in Ohio. Ohio Archaeology.org 2018: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Philip, and James A. Brown. 1978. Pre-Columbian Shell Engravings from the Craig Mound at Spiro, OK. Part I. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Ponziglione, P. M. S.J. 1897. The Osages and Father John Schoenmakers, S.J., Interesting Memoirs Collected from Legends, Traditions, and Historical Documents. Handwritten manuscript, file at Midwest Jesuit Archives. St. Louis, MO, pp. 1–561. [Google Scholar]

- Radin, Paul. 1954. The Evolution of an American Indian Prose Epic. Washington: Special Publications of Bollingen Foundation, No. 3. Basel: Ethnographical Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, F. Kent, III. 2004. People of Earth, People of Sky: Visualizing the Sacred in Native American Art of the Mississippian Period. In Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South. Edited by Richard F. Townsend and R. V. Sharp. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, pp. 125–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, F. Kent, III. 2007. The Petaloid Motif: A Celestial Symbolic Locative in the Shell Art of Spiro. In Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. Edited by F. Kent Reilly, III and James F. Garber. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, F. Kent, III, and James F. Garber, eds. 2007. Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spinden, Herbert J. 1931. Indian Symbolism. In Introduction to American Indian Art to Accompany the First Exhibition of American Indian Art Selected Entirely with Consideration of Esthetic Value. Edited by Oliver Lafarge, Herbert J. Spinden and Frederick Hodge. New York: Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, Inc., pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tixier, C. M. 1940. Tixier’s Travels on the Osage Prairies. Edited by J. F. McDermott. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Richard F. 2015. The Cave, Cahokia, and the Omaha Tribe. In Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados, James R. Duncan and F. Kent Reilly, III. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 145–65. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Patty Jo. 2015. Foreword. In PICTURE CAVE: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. xv–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Patty Jo, Steven A. LeBlanc, and Charles L. Redman. 1984. Archaeological Explanation: The Scientific Method in Archaeology. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).