Abstract

This paper discusses iconographic features of the deity or “demon” Medjed (Mḏd). The specific and unusual image of this character is only found during the 21st Dynasty and is unknown in the funerary art of the New Kingdom and Late Period. Only oneYe coffin and nine papyri are known in which the image of Medjed is depicted. Eight are in the context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead. In the text of Spell 17, Medjed is described in lines 71–72 of Grapow’s Urk. V Abschnitt 24. The “invisibility” of this “demon” is evidently the reason for his unusual iconography: Medjed has a conical shaped body, with human legs. Although he does not have a true head, his eyes are indicated, and he wears a belt. Equally the deity could be depicted as a figure covered entirely in a conical cover except for the eyes and feet, which are visible. This curious treatment can be understood as an attempt by Egyptian artists to depict an invisible being.

1. Introduction

The Book of the Dead is a compendium of funerary spells that is attested over a millennium, from the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period (see Lucarelli and Stadler 2023). The evolution of the collection during this time was inextricably linked with social and cultural changes. In my opinion, these changes are best traced in the development of the pictorial tradition of the Book of the Dead, since its textual content remained relatively conservative.

For instance, the development of the pictorial tradition depicted in Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead can be cited, as it is one of the longest and most significant spells in the collection. The origins of this text can be traced back to Spell 335 of the Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts, a period during which it was not accompanied by illustrations. The first vignettes of the Book of the Dead Spell 17 were produced during the 18th Dynasty. However, these vignettes did not establish a dominant tradition, or “canon” (Munro 1988, pp. 67–68; Tarasenko 2014, pp. 241–56).

A revolutionary change occurred at the beginning of the Ramesside Period, when Spell 17 was suddenly endowed with a long frieze of vignettes, comprising approximately twenty scenes with mythological content. These vignettes served to supplement the mythological and exegetical text of the spell itself. It is hypothesised that this phenomenon may be attributed to significant ideological changes among the Theban elite, particularly the priesthood and master artists responsible for the creation of religious and funerary monuments. These shifts followed the collapse of Akhenaton’s reform and the subsequent religious “counter-reformation” (see Tarasenko 2020). The advent of this phase offered new possibilities for artistic expression in funerary art, likely facilitating the emergence of subjects within the context of the evolution of concepts pertaining to “personal piety” and the “new solar theology” (see Assmann 1995, passim; 2001, p. 189ff).

Following the relocation of the royal residence to the Nile Delta during the 21st Dynasty, the priests of Thebes and artisans specialising in funerary and religious artefacts acquired further opportunities and freedoms, as can be seen from the emergence of numerous new iconographic schemes. This phenomenon can be attributed to two factors: the political independence of Thebaid during this period and the development of theological ideas that have been termed “polymorphic monotheism” by Andrzej Niwiński (2000, p. 28)1, in contrast with the “monomorphic monotheism” that is characteristic of Amarna ideology2. This development led to a flourishing of religious art in Thebes, which in turn gave rise to a plethora of new iconographic compositions, both independent and inspired by the royal Books of the Netherworld. These are present in the decoration of coffins and funerary papyri.

This process of experimentation and artistic freedom found expression in the Book of the Dead, notably its Spell 17. In the second half of the 21st Dynasty, a number of papyri were illustrated with a distinctive frieze of Spell 17 vignettes (Tarasenko 2012, pp. 384–86). This remarkable series has also been identified in the decoration of one coffin. It is within this series of images that the image of the special “demon”3 Medjed (Mḏd) is depicted.

The main goal of this article is to study this particular figure, so my research focuses on iconographic and semantic analyses of the image of Medjed in these vignettes. To reach this goal, I present my results as follows:

- −

- Translation and commentary on a text connected with Medjed—a passage in the Book of the Dead Spell 17, together with analysis of this “deity’s” name;

- −

- Collection and analysis of existing interpretations of the iconography of Medjed;

- −

- Collect all available sources with the image of Medjded in Book of the Dead manuscripts and in coffins;

- −

- Discussion and proposed interpretation of the semantics of images of Medjed.

1.1. Medjed in Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead

In my opinion, an explanation of the unusual iconography of Medjed should be preceded by a description of his functions in the text of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead. Medjed is mentioned in lines 71–72 of Section 24 as identified by Hermann Grapow (Grapow 1917, (Urk. V), Abs. 24, pp. 71–72; cf. Cariddi 2018, p. 199), where the various judges and executioners in Osiris’s suite in the Afterworld are described (Grapow 1912, pp. 16–17; Heerma van Voss 1988, p. 6; Rößler-Köhler 1979, p. 163; Cariddi 2018, p. 199) (after pNb.sni pLondon BM EA 9990, 18th Dynasty, Memphis (Lapp 2006, pp. 236, 238)):

| |

| (71) rḫ.kwj rn n Mḏd pwy jmy⸗zn n pr Wsjr stj m jrt(⸗f) nn mꜢ.n.tw⸗f dbn (72) pt m nzrt n rꜢ⸗f smj ḥꜤpy ⟨nn⟩ mꜢ.n.tw⸗f | (71) I know the name of this Medjed who is with them in the House of Osiris, who shoots with (his) eye4 while he cannot be seen, who encircles the (72) sky with the flame of his mouth, who announces the Inundation while he <cannot> be seen. |

1.2. The Name ‘Medjed’

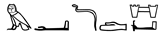

Let us proceed to the analysis of this character. The name  ;

;  Mḏd (after Leitz (2002, III, p. 476) and Table 1) derives from the verb

Mḏd (after Leitz (2002, III, p. 476) and Table 1) derives from the verb  ,

,  mḏd, which according to Rainer Hannig bore up to seven meanings in different grammar constructions in the Middle Kingdom (Hannig 1995, p. 383; 2006, II, pp. 1173–74; cf. Erman and Grapow 1955, II, p. 191)5. Five of them are:

mḏd, which according to Rainer Hannig bore up to seven meanings in different grammar constructions in the Middle Kingdom (Hannig 1995, p. 383; 2006, II, pp. 1173–74; cf. Erman and Grapow 1955, II, p. 191)5. Five of them are:

;

;  Mḏd (after Leitz (2002, III, p. 476) and Table 1) derives from the verb

Mḏd (after Leitz (2002, III, p. 476) and Table 1) derives from the verb  ,

,  mḏd, which according to Rainer Hannig bore up to seven meanings in different grammar constructions in the Middle Kingdom (Hannig 1995, p. 383; 2006, II, pp. 1173–74; cf. Erman and Grapow 1955, II, p. 191)5. Five of them are:

mḏd, which according to Rainer Hannig bore up to seven meanings in different grammar constructions in the Middle Kingdom (Hannig 1995, p. 383; 2006, II, pp. 1173–74; cf. Erman and Grapow 1955, II, p. 191)5. Five of them are:

Table 1.

Writings of the name Mḏd in the “Theban Edition” of the Book of the Dead (after Lapp 2006, pp. 236–37).

- “to press”, “to squeeze a press” (“pressen”, “drücken”);

- “to get”, “to strike” (“treffen”);

- “to impose”, “to assign” (collecting a tax, etc.) (“auferlegen”);

- “to obey”, “to execute” (“gehorchen”, “befolgen”)”;

- “to divide” (“teilen”), etc.

The meaning “to destroy” is first

attested from later (Lesko 2002, I, p. 221). This diversity of meanings and difference between periods makes it

difficult to determine the meaning of the name Mḏd. According to the Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und

Götterbezeichnungen, it designates “der Treffsichere”—“well-aimed”,

“exact”, “right” (Leitz 2002, III, p. 476)

(Similarly Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–92; Rößler-Köhler

1979, p. 227, Anm. 4 (“Der Treffsicheren”); Backes

2005, p. 79 (Mḏdw/Mḏd “Der Treffsichere”)),

while Bengt Peterson (1963, pp. 83–88) connects its meaning with “pressing” (grapes to in winemaking,

compare the determinatives  ,

,  , and

, and  ). The same

understanding is given by Stephen Quirke

(2013, p. 60): “one who presses”. T. George Allen and

Raymond Faulkner translated Mḏd as “Smiter” (Allen 1960, p. 90;

1974, pp. 30, 292; Faulkner 2001, p. 48). A quite

similar understanding “Chastiser” (“Каратeль”) was offered by Mikhail Chegodaev (2002, p. 100). Paul Barguet (1967, p. 62) gave the

translation “Broyeur” (i.e., “Breaker”/“Cruncher”), while Claude Carrier (2010, p. 18 (77))

translates “agitateur”. Erik Hornung (1979, p. 71) left the name of Mḏd untranslated: “Medjed” (see also

Cariddi 2018, pp. 203–4; Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 83–84).

). The same

understanding is given by Stephen Quirke

(2013, p. 60): “one who presses”. T. George Allen and

Raymond Faulkner translated Mḏd as “Smiter” (Allen 1960, p. 90;

1974, pp. 30, 292; Faulkner 2001, p. 48). A quite

similar understanding “Chastiser” (“Каратeль”) was offered by Mikhail Chegodaev (2002, p. 100). Paul Barguet (1967, p. 62) gave the

translation “Broyeur” (i.e., “Breaker”/“Cruncher”), while Claude Carrier (2010, p. 18 (77))

translates “agitateur”. Erik Hornung (1979, p. 71) left the name of Mḏd untranslated: “Medjed” (see also

Cariddi 2018, pp. 203–4; Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 83–84).

,

,  , and

, and  ). The same

understanding is given by Stephen Quirke

(2013, p. 60): “one who presses”. T. George Allen and

Raymond Faulkner translated Mḏd as “Smiter” (Allen 1960, p. 90;

1974, pp. 30, 292; Faulkner 2001, p. 48). A quite

similar understanding “Chastiser” (“Каратeль”) was offered by Mikhail Chegodaev (2002, p. 100). Paul Barguet (1967, p. 62) gave the

translation “Broyeur” (i.e., “Breaker”/“Cruncher”), while Claude Carrier (2010, p. 18 (77))

translates “agitateur”. Erik Hornung (1979, p. 71) left the name of Mḏd untranslated: “Medjed” (see also

Cariddi 2018, pp. 203–4; Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 83–84).

). The same

understanding is given by Stephen Quirke

(2013, p. 60): “one who presses”. T. George Allen and

Raymond Faulkner translated Mḏd as “Smiter” (Allen 1960, p. 90;

1974, pp. 30, 292; Faulkner 2001, p. 48). A quite

similar understanding “Chastiser” (“Каратeль”) was offered by Mikhail Chegodaev (2002, p. 100). Paul Barguet (1967, p. 62) gave the

translation “Broyeur” (i.e., “Breaker”/“Cruncher”), while Claude Carrier (2010, p. 18 (77))

translates “agitateur”. Erik Hornung (1979, p. 71) left the name of Mḏd untranslated: “Medjed” (see also

Cariddi 2018, pp. 203–4; Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 83–84).The earliest known mention of the “deity” Mḏd is from the Middle Kingdom (Leitz 2002, III, p. 476). On the astronomical “tables” on a number of Theban coffins Mḏd designates one of the Decans ( ); that name later changed to Šsmw (Neugebauer and Parker 1960, pl. 27 (12. “crew” (?)); Leitz 2002, III, p. 476). It is noteworthy that both Medjed and Shesemu appear together in the same semantic context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead and are associated with the sky, light, and the inundation (Grapow 1917, (=Urk. V), Abs. 24, pp. 71–72 (61–62)). Bengt Peterson observed that this co-occurrence could confirm their connection (Peterson 1963; cf. Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 79–83).

); that name later changed to Šsmw (Neugebauer and Parker 1960, pl. 27 (12. “crew” (?)); Leitz 2002, III, p. 476). It is noteworthy that both Medjed and Shesemu appear together in the same semantic context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead and are associated with the sky, light, and the inundation (Grapow 1917, (=Urk. V), Abs. 24, pp. 71–72 (61–62)). Bengt Peterson observed that this co-occurrence could confirm their connection (Peterson 1963; cf. Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 79–83).

); that name later changed to Šsmw (Neugebauer and Parker 1960, pl. 27 (12. “crew” (?)); Leitz 2002, III, p. 476). It is noteworthy that both Medjed and Shesemu appear together in the same semantic context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead and are associated with the sky, light, and the inundation (Grapow 1917, (=Urk. V), Abs. 24, pp. 71–72 (61–62)). Bengt Peterson observed that this co-occurrence could confirm their connection (Peterson 1963; cf. Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 79–83).

); that name later changed to Šsmw (Neugebauer and Parker 1960, pl. 27 (12. “crew” (?)); Leitz 2002, III, p. 476). It is noteworthy that both Medjed and Shesemu appear together in the same semantic context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead and are associated with the sky, light, and the inundation (Grapow 1917, (=Urk. V), Abs. 24, pp. 71–72 (61–62)). Bengt Peterson observed that this co-occurrence could confirm their connection (Peterson 1963; cf. Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 79–83).2. Sources with Medjed Images: Catalogue

As noted above, the image of Medjed is depicted in nine papyri of the Book of the Dead and on one coffin of the 21st Dynasty. In eight cases, it appears in the vignettes of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead. I start this catalogue with a short description of the sources (see also the Appendix A):

- 1.

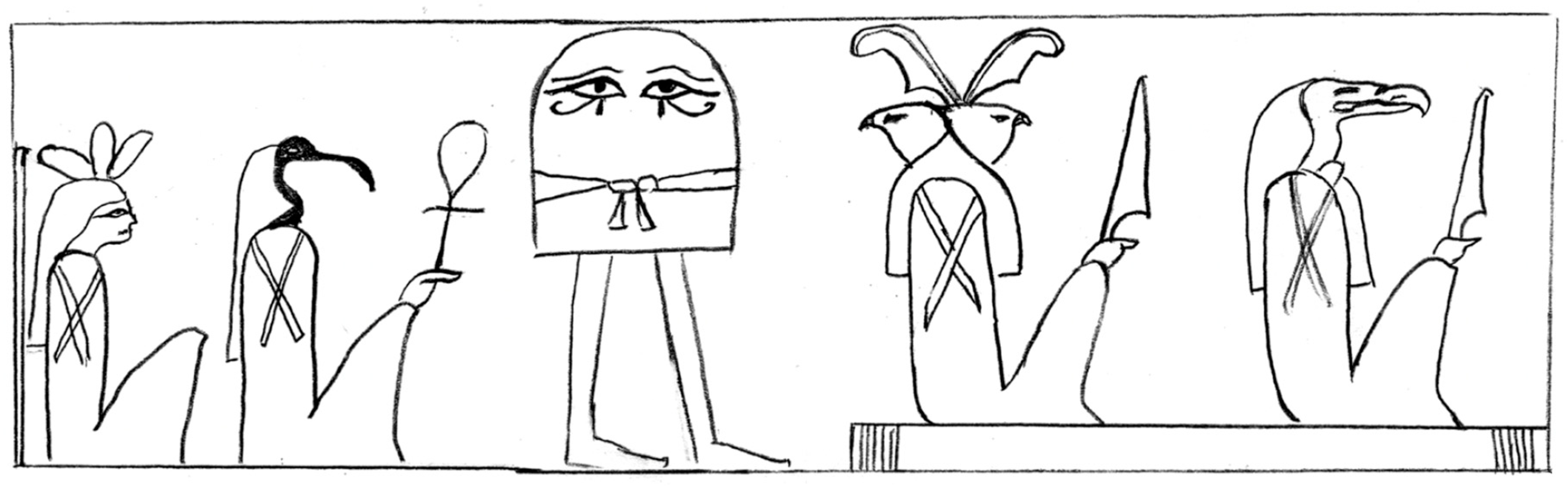

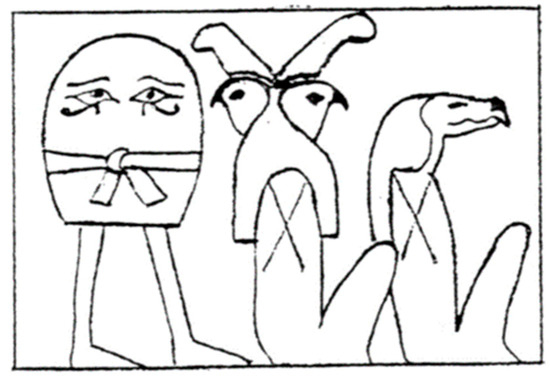

- Papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗s-n-Mwt pCairo J.E. 95637/S.R. IV. 528 (unpublished)6 (Figure 1). This document represents a combination of the Book of the Dead and the content Amduat papyri (Books of the Netherworld). It contains the text of Spells 125A/125B and pictures originating from the vignettes of Spells 125B, 150, 83, 110, as well as four scenes (from left to right) from the central register of the vignettes in Spell 17: the image of a bnw-bird, goose, and falcon on a pedestal, and the three “demons”, the first with the head of a kite and the second with two opposite-facing falcon heads with mꜢꜤt-feathers. These demons hold knives. The last character is Medjed himself.

Figure 1. Papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗s-n-Mwt pCairo J.E. 95637/S.R. IV. 528. (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 4b).

Figure 1. Papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗s-n-Mwt pCairo J.E. 95637/S.R. IV. 528. (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 4b).

- 2.

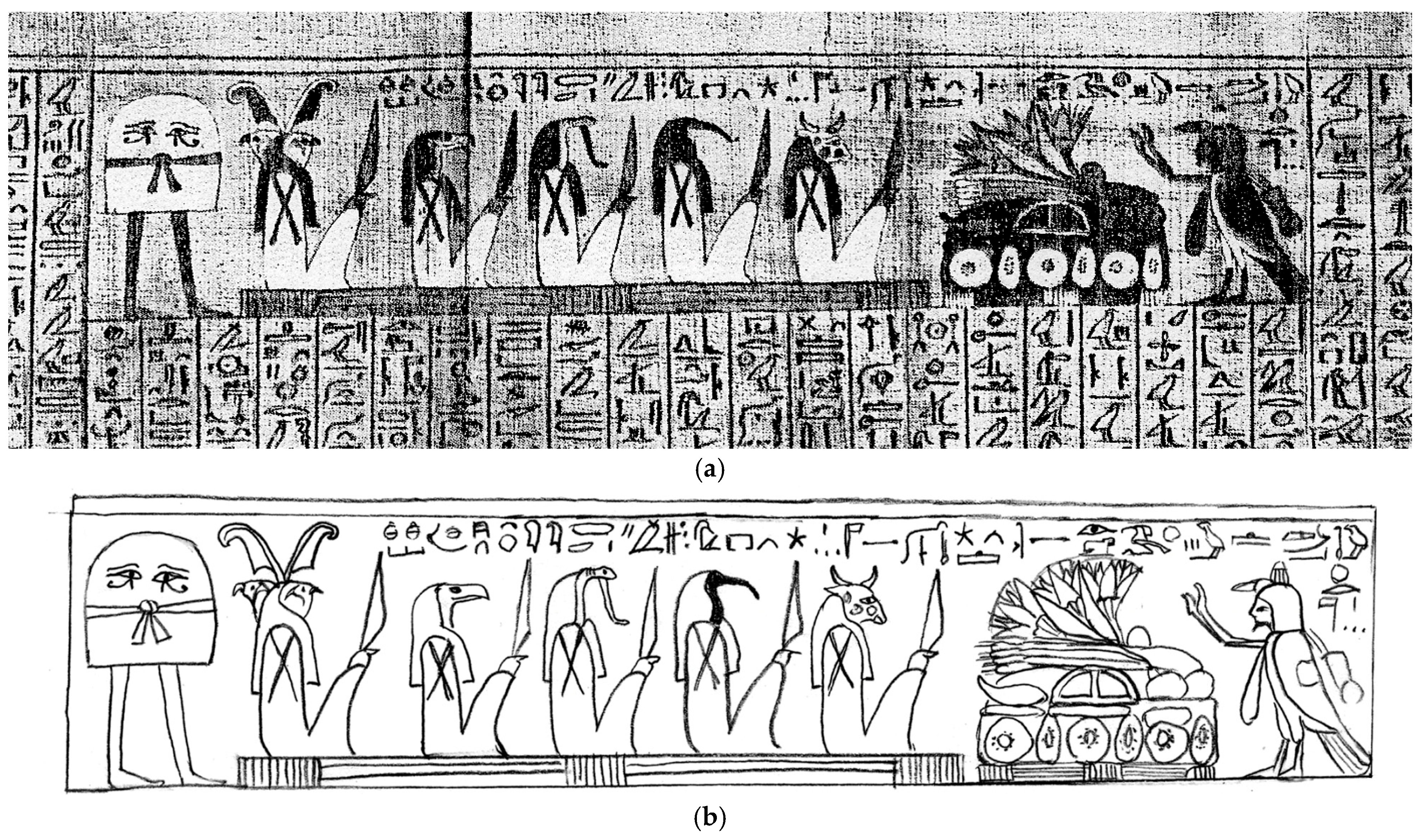

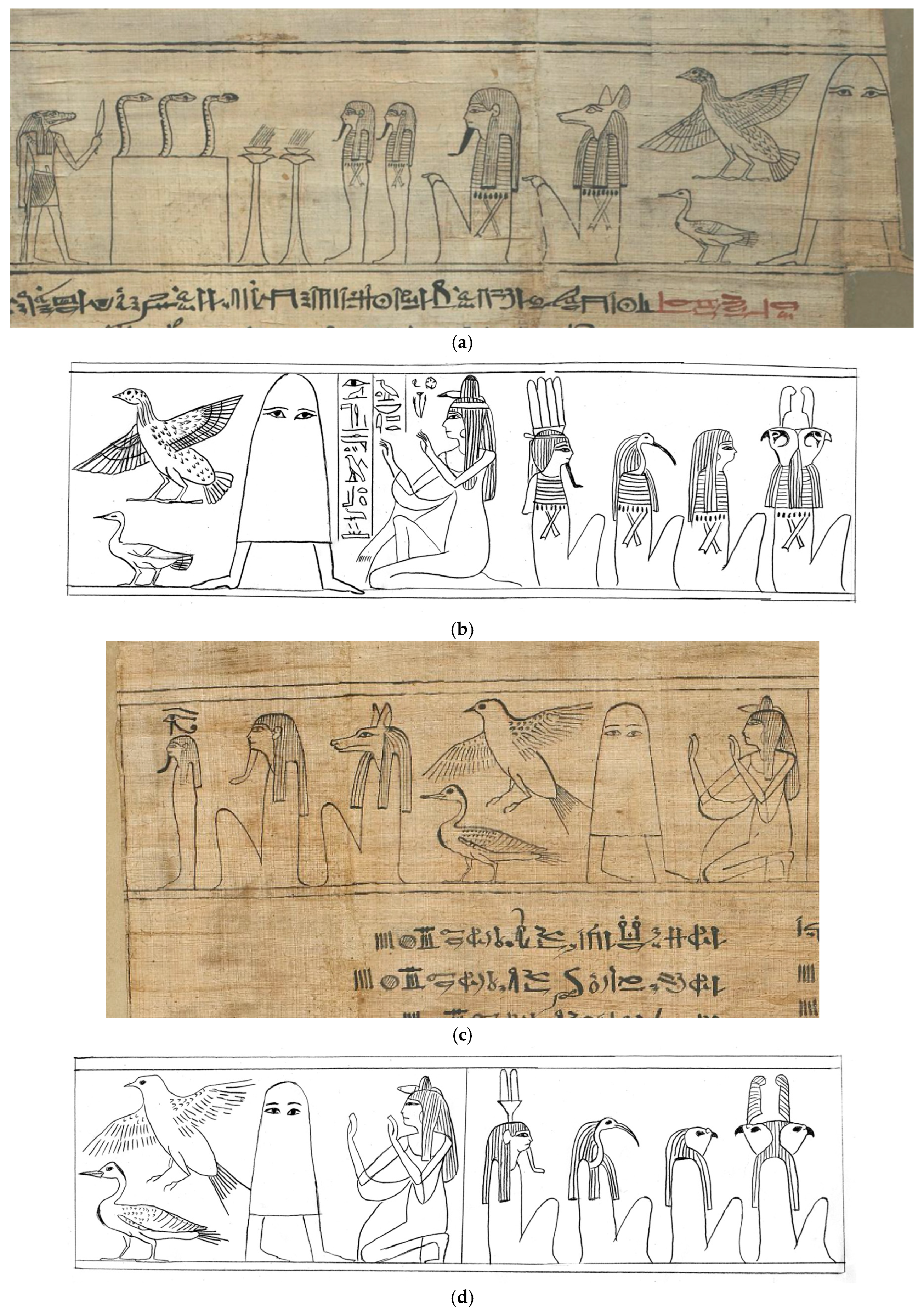

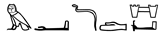

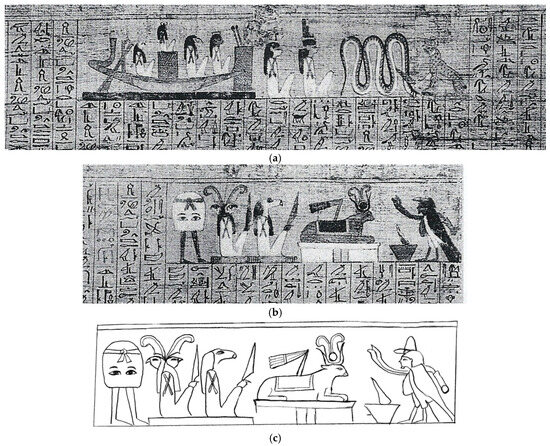

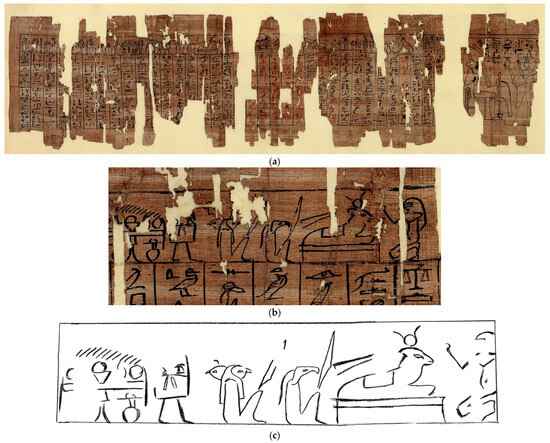

- Papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCairo J.E. 95658; S.R. IV. 5567 (Figure 2a,b). Six spells of the Book of the Dead are written in this roll: 1, 57, 89, 148, 56, and 9. Three spells (1, 148, and 9) are illustrated with coloured vignettes. Medjed is illustrated in Spell 148. The vignette shows the bꜢ-soul of the deceased before an offering table, behind which are six deities. The first three gods (from left to right) appear in the so-called Scene XIII of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead (Milde 1991, pp. 36–37), while the last three figures represent “demons”, similar to those in the previous roll (no 1 above). Medjed is the last in this group.

Figure 2. (a,b) The image of Medjed in the papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCairo J.E. 95658; S.R. IV. 556. (after Bruyère 1939, p. 184, fig. 78; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 4a).

Figure 2. (a,b) The image of Medjed in the papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCairo J.E. 95658; S.R. IV. 556. (after Bruyère 1939, p. 184, fig. 78; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 4a).

- 3.

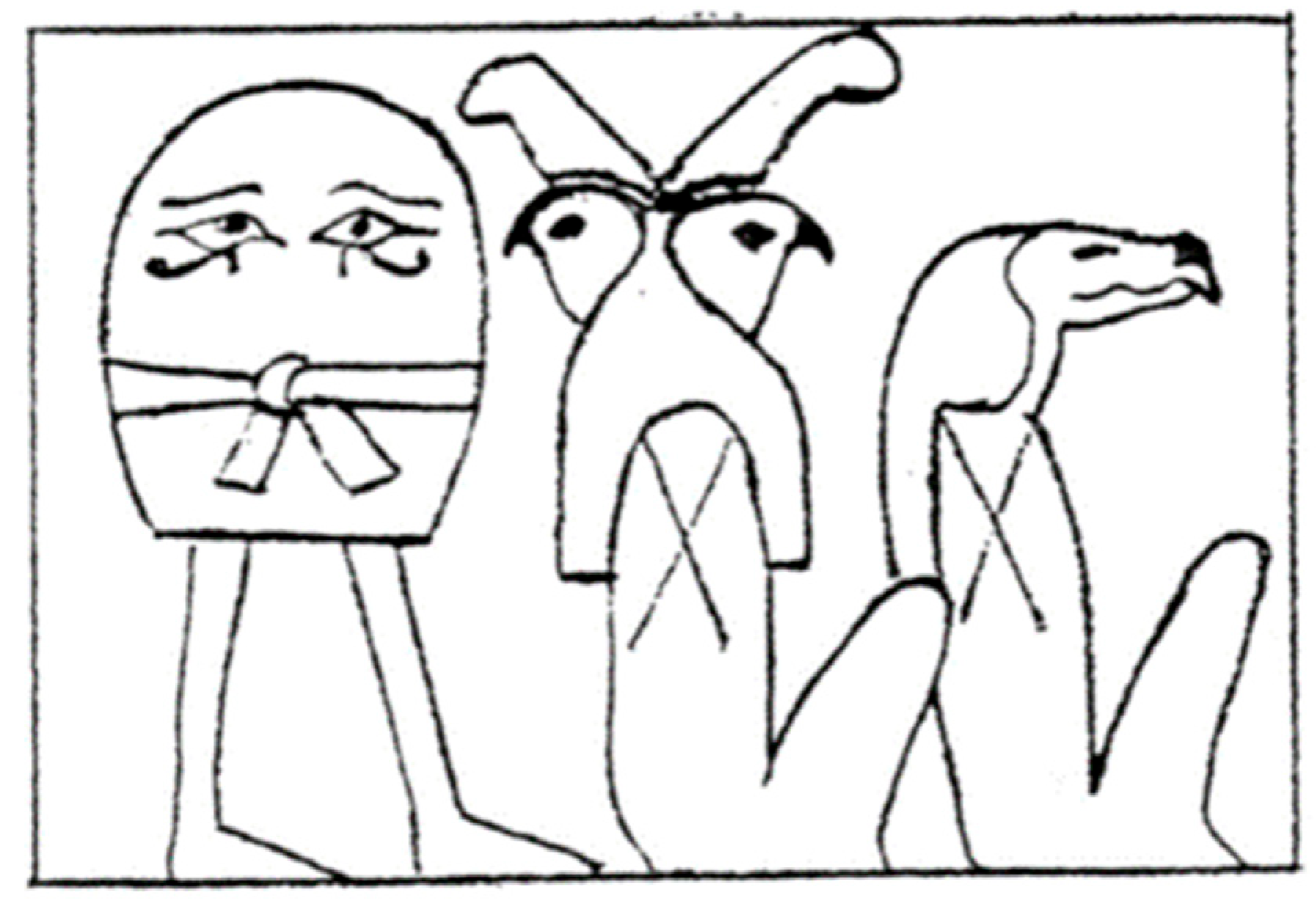

- Papyrus of TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw pCairo S.R. VII. 10222 (unpublished)8. The papyrus does not include any text of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead, only its vignettes. The manuscript begins with a vignette of Spell 110 and is followed by Spells 149, 77, 89, 138, 148, 81A, and 1 with colour pictures. As was noted by Matthieu Heerma van Voss, the two spells in this roll are illustrated by vignettes of Spell 17—77 and 81A (Heerma van Voss 1977, pp. 87, 88). Spell 81A is accompanied by images of Isis and Nephthys in the form of kites near the mummy of Osiris, as well as figures of the god Heh and a falcon. All these images derive from the vignettes in Spell 17. The drawing of three “demons” together with Medjed (again in the final position), is presented as a vignette of Spell 77 of the Book of the Dead (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw pCairo S.R. VII. 10222 (after Milde 1991, p. 44, fig. 15).

Figure 3. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw pCairo S.R. VII. 10222 (after Milde 1991, p. 44, fig. 15).

- 4.

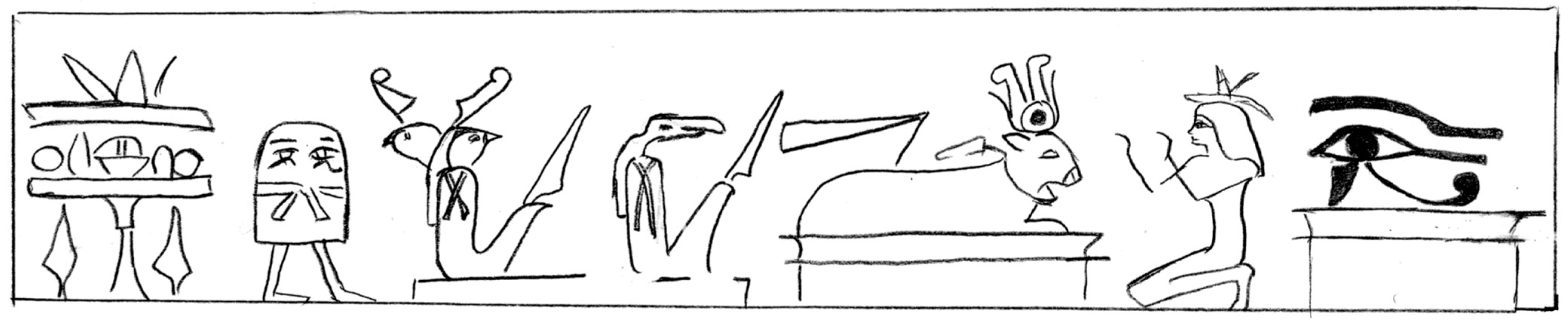

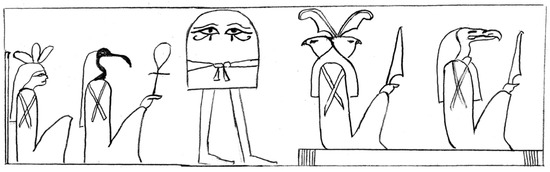

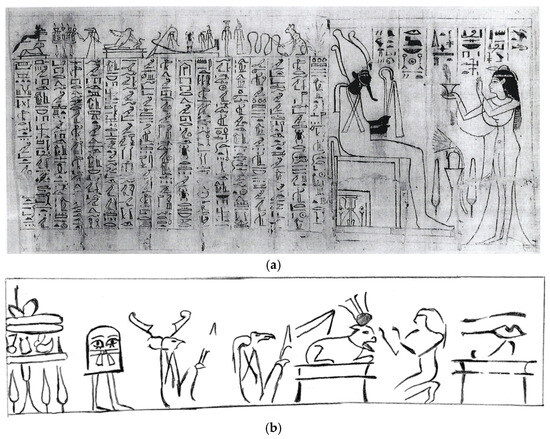

- Papyrus of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt pCologny-Geneva C (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, pBodmer 100)9 (von Bissing 1928, Taf. I; Sallé 1990, pp. 28–35; Bickel 2001, pp. 117–34, figs. 32, 39; Heerma van Voss 2008, pp. 163–66). In this document, as well as in all subsequent sources, Medjed appears in the context of the Spell 17 vignettes and text. This rather small papyrus (3.78 m) contains ten spells of the Book of the Dead, two of which are followed by coloured vignettes—Spells 17 and 125B. The scenes in Spell 17 are divided in five blocks, separated by the text columns. Only two of them (II and III) are published (von Bissing 1928, Taf. I; Bickel 2001, pp. 128–29, fig. 39; Tarasenko 2012, p. 383, fig. 4a–b; Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 2b) (Figure 4a–c). In general, the sequence of scenes in the papyrus of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt has similarities with the Spell 17 vignettes in pBerlin P. 3157.

Figure 4. (a–c) Vignettes of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead in the papyrus of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt, pCologny-Geneva C (after von Bissing 1928, Taf. I; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 2b).

Figure 4. (a–c) Vignettes of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead in the papyrus of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt, pCologny-Geneva C (after von Bissing 1928, Taf. I; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 2b).

Medjed is shown in block II (Figure 4b,c). Here the bꜢ-soul of the deceased adores the Mekhet-Weret cow who is set on a plinth; three “demons” are shown behind her, the last one being Medjed. Matthieu Heerma van Voss already observed the similarity of the iconography of these three “demons” in the papyri of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt and TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw, noting that in the latter the text of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead is absent, and in both rolls the sequence of scenes on vignettes is opposite to the direction in which the text is read (Heerma van Voss 1988, p. 6).

- 5.

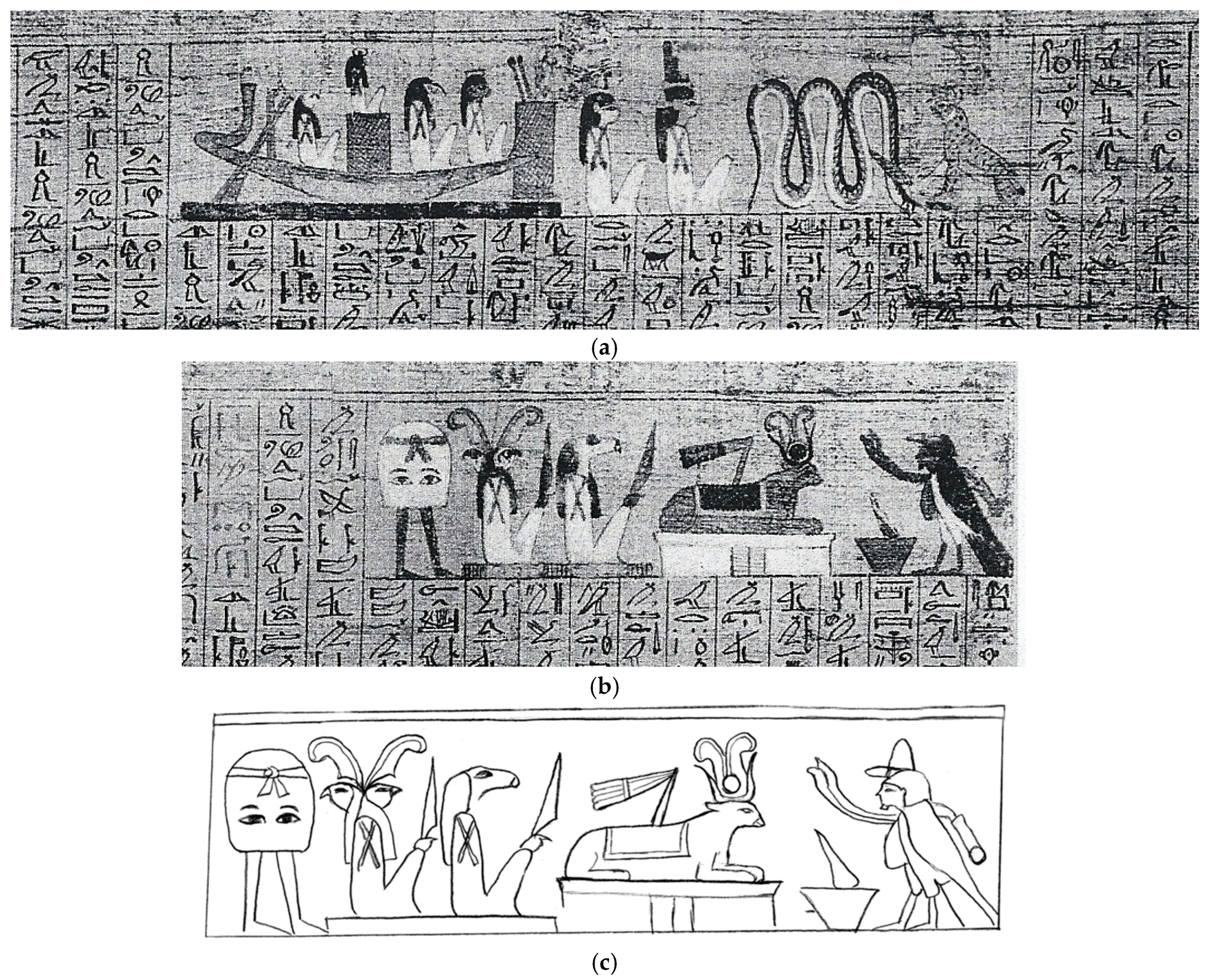

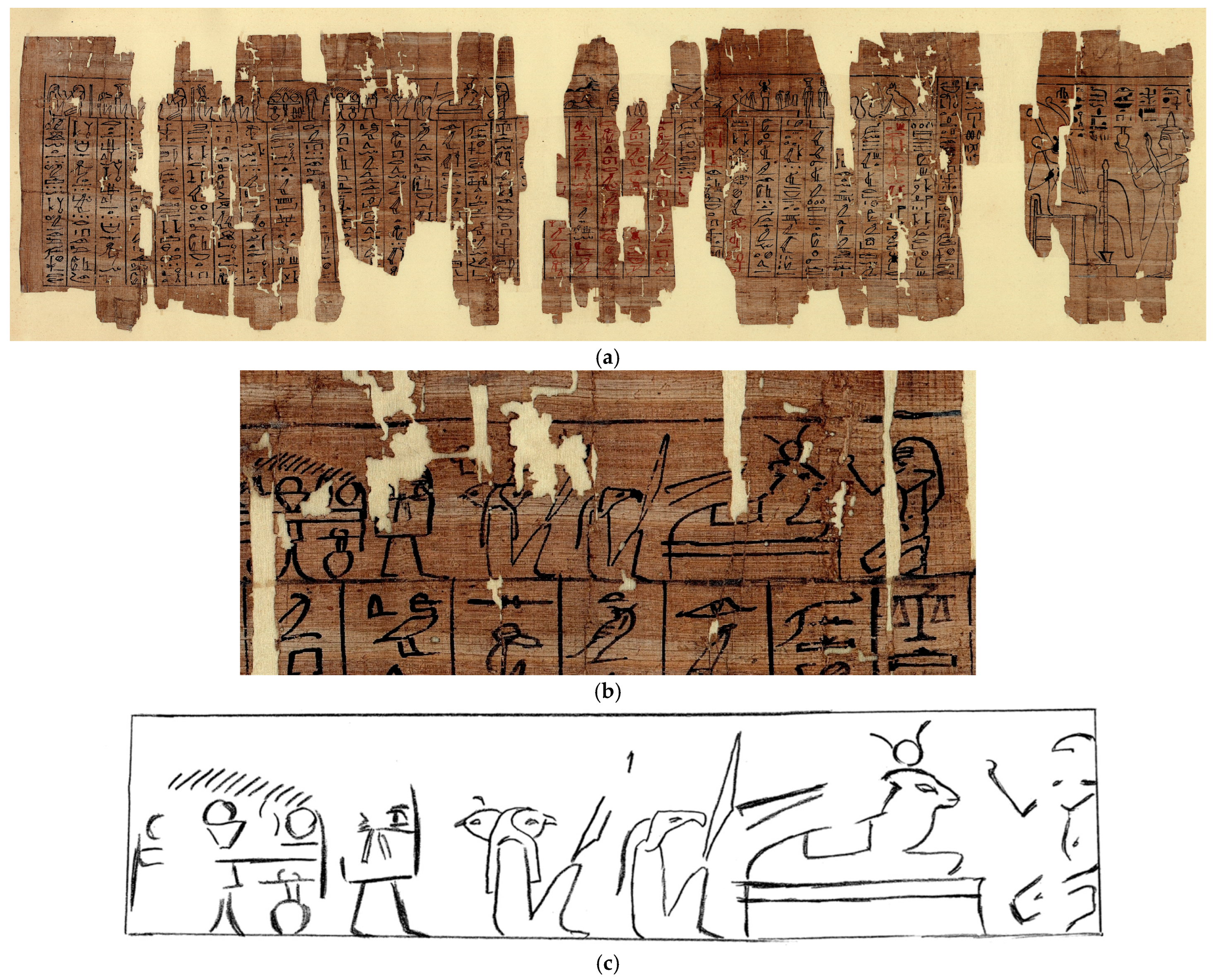

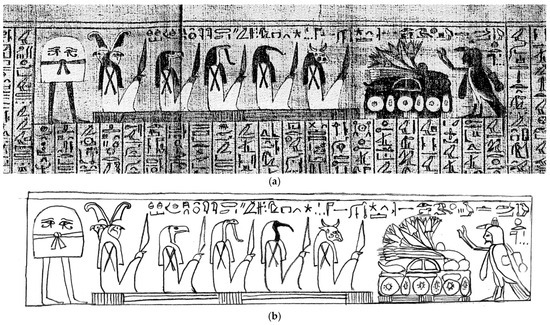

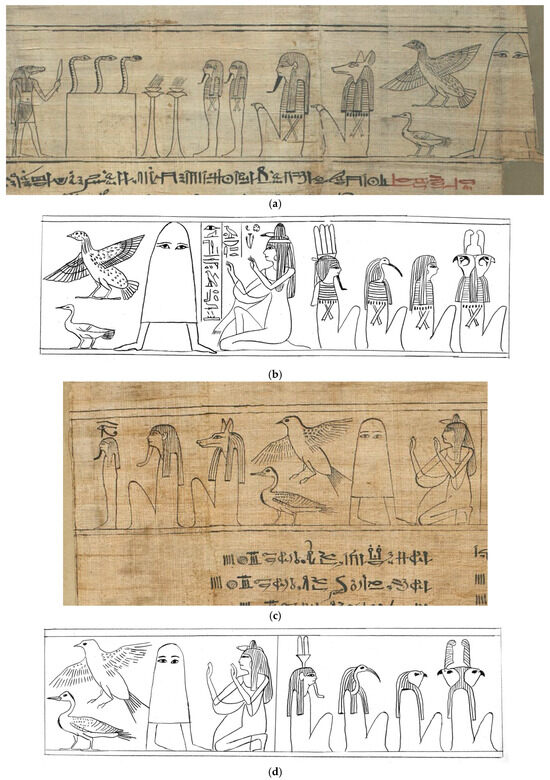

- Papyrus of Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw pLondon BM EA 10554 (pGreenfield)10 (Budge 1912; Lenzo 2023). This roll belonged to the notable Theban priestess, the younger daughter of the High Priest of Amun Pinudjem II and his second wife Nsj-Ḫnsw (Niwiński 1988, pp. 226–30). This manuscript is probably the latest copy of the Third Intermediate Period Book of the Dead with the illustrations for Spell 17. In terms of chronology, it could therefore be the latest document with an image of Medjed11. This impressive roll of 40.53 metres is written in hieratic, as became common for the Book of the Dead during the late 21st Dynasty; the only spell written in hieroglyphs is 125B. The image of Medjed occurs twice in duplicated vignettes of Spell 17 accompanying other spells. In the first case, it illustrates Spells 23–26 (Budge 1912, pl. XV; Lenzo 2023, Sheet 12) (Figure 5a,b); the second example is with the part of the Hymn to Re and Osiris where a list of various “entities” or “forms” of Re is given (Budge 1912, pl. LXXXVIII; Lenzo 2023, Sheet 76) (Figure 5c,d).

Figure 5. (a–d) The images of Medjed in the papyrus of Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw pLondon BM EA 10554 (pGreenfield) (after Lenzo 2023, Sheet 12, 76; drawings after Cariddi 2018, p. 200, fig. 5). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Figure 5. (a–d) The images of Medjed in the papyrus of Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw pLondon BM EA 10554 (pGreenfield) (after Lenzo 2023, Sheet 12, 76; drawings after Cariddi 2018, p. 200, fig. 5). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

In both cases, Medjed appears together with the figures of a goose and a bird with open wings above it12, and two deities, one of whom is shown with the head of a jackal. Medjed’s feet in the first pGreenfield example are splayed in opposite directions; this might fit with his ‘face’, which is frontal, but it could also indicate that he relates to the other figures on both sides of him13; that detail is not present in any of the other examples. However, in the second scene (Figure 5c), Medjed is probably represented as an independent character with his legs turned away the other figures and the image of the deceased kneeling in front of him. Curiously, E. A. Wallis Budge saw in the first drawing of this being the figure of Medjed (Budge 1912, p. 13; pl. XV, fn.1), while he understood the second as “The Devourer of Millions” (Ꜥm ḥḥw), a deity who is also mentioned in Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead (Budge 1912, p. 70; pl. LXXXVIII, fn. 2).

- 6.

- Papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCologny-Geneva CI (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, pBodmer 101, unpublished)14. This is the first in a series of five almost identically “replicated” rolls that attest to a specific tradition of illustration that was confined to the 21st Dynasty (Tarasenko 2012, pp. 384–87). So far, only one roll of this group (pLondon BM EA 9948) has been partially published; the other four examples are practically unknown to scholars (cf. Niwiński 1989). These documents are of the greatest importance for reconstructing the stages of graphic development in papyri during this period, and they may constitute a special type (similar to the BD.II.1 type in the classification of Niwiński (1989, pp. 118–28)) playing an important role in this evolution (See in detail Tarasenko 2012, pp. 384–87). All these rolls have an identical order of spells and illustrations. They consist of an introductory vignette (individual in each document), the text of Spells 17 and 1 of the Book of the Dead, followed by a series of selected vignettes of Spell 17 (the top frieze). In total, a series of twelve scenes, starting with pictures of a cat, a serpent, and an jšd-tree,15 followed by the figures of Isis and Nephthys, and finishing with the adoration scene, are represented on these papyri. The images of three “demons”, with Medjed as the last of them, are in the eighth scene (‘h’) (Tarasenko 2012, p. 385). This scene is preserved in four rolls of this group. In the fifth document, the papyrus of Ḏd-Ḫnsw pSaint-Petersburg Hermitage 18587, it is destroyed16. Before these characters comes scene ‘g’, showing the adoration of Mekhet-Weret—similar to the papyrus of Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt pCologny-Geneva C (Figure 4b)—and it is followed by the image of a deity in front of an offering table (scene ‘i’) (Tarasenko 2012, pp. 385–86) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCologny-Geneva CI (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 198, fig. 1a).

Figure 6. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCologny-Geneva CI (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 198, fig. 1a).

- 7.

- Papyrus of TꜢ-nt-Jmntt-hrt-jb pCologny-Geneva CII (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, pBodmer 102) (unpublished)17 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of TꜢ-nt-Jmntt-hrt-jb pCologny-Geneva CII. (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 198, fig. 1b).

Figure 7. The image of Medjed in the papyrus of TꜢ-nt-Jmntt-hrt-jb pCologny-Geneva CII. (drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 198, fig. 1b). - 8.

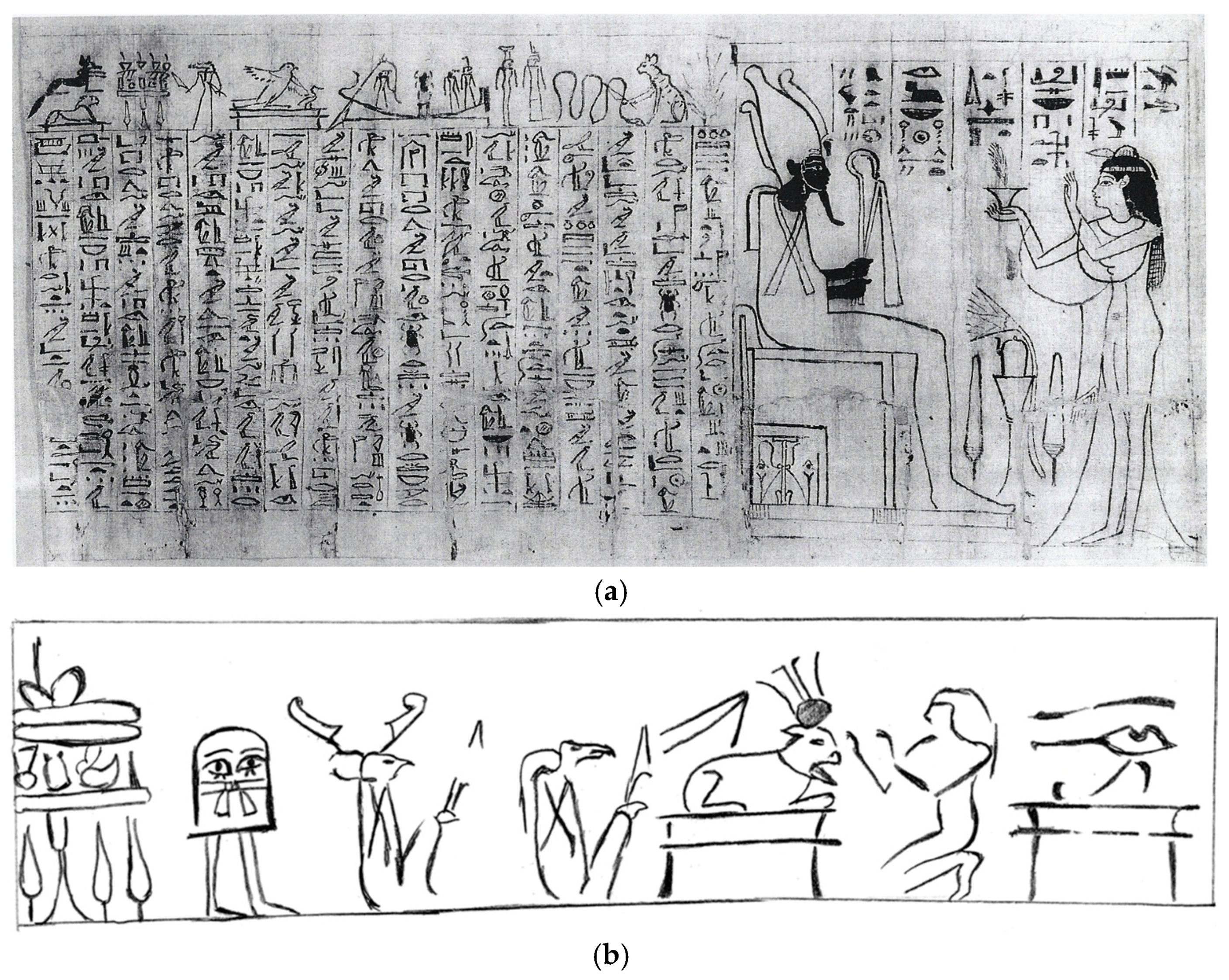

Figure 8. (a–c) Papyrus of Nsy-Ḫnsw pTurin 1818 (a) and its image of Medjed (b,c) (pTurin Cat. 1818: © Photo Museo Egizio Turin Egyptian Museum (https://papyri.museoegizio.it/d/258 (accessed on 29 June 2025)); drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 2a).

Figure 8. (a–c) Papyrus of Nsy-Ḫnsw pTurin 1818 (a) and its image of Medjed (b,c) (pTurin Cat. 1818: © Photo Museo Egizio Turin Egyptian Museum (https://papyri.museoegizio.it/d/258 (accessed on 29 June 2025)); drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 2a).- 9.

Figure 9. (a,b) First sheet of the papyrus of Djw-sw-n-Mwt pLondon BM EA 9948 (a) and its image of Medjed (b) (after Shorter 1938, pl. X = Tarasenko 2012, 385, fig. 5; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 3a).

Figure 9. (a,b) First sheet of the papyrus of Djw-sw-n-Mwt pLondon BM EA 9948 (a) and its image of Medjed (b) (after Shorter 1938, pl. X = Tarasenko 2012, 385, fig. 5; drawing after Cariddi 2018, p. 199, fig. 3a).- 10.

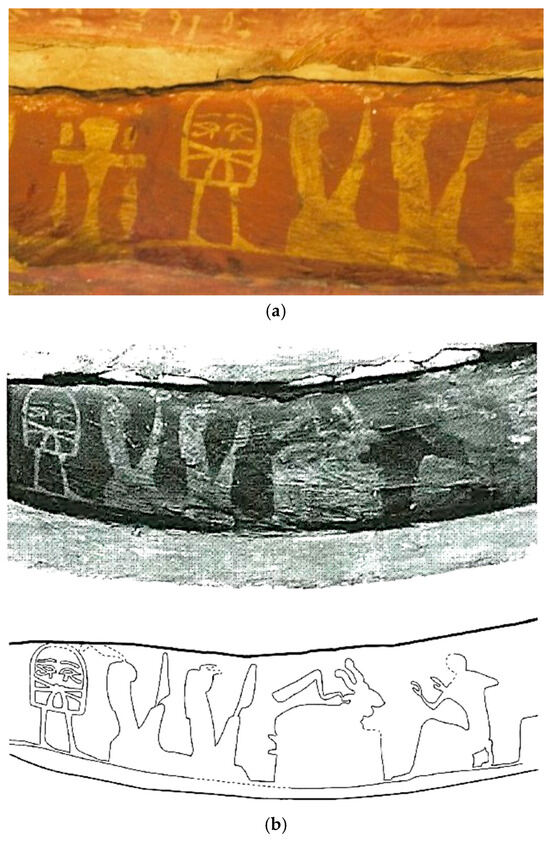

- The decoration of the interior walls of the lid of the inner coffin of PꜢ-dj-Ḫnsw Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2320–2321 (Jamen 2015, pp. 102–4) (Figure 10a,b).

Figure 10. (a,b) The image of Medjed on the coffin of PꜢ-dj-Ḫnsw Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2320–2321 ((a) © photo by F. Jamen = Tarasenko (2016, p. 19, fig. 27a); (b) after Jamen (2015, p. 102, fig. 39)).

Figure 10. (a,b) The image of Medjed on the coffin of PꜢ-dj-Ḫnsw Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2320–2321 ((a) © photo by F. Jamen = Tarasenko (2016, p. 19, fig. 27a); (b) after Jamen (2015, p. 102, fig. 39)).

3. Iconography of Medjed

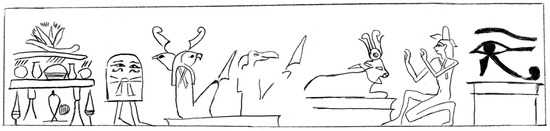

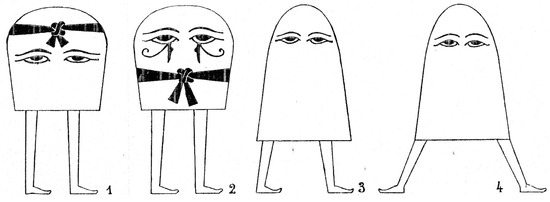

This “deity” or “demon” has a conical body with human legs (pGreenfield), or perhaps with a conical-shaped cover hiding his body (Milde 1991, p. 44). In other sources Medjed looks like rectangle with a round top, close in shape to a round-topped stela (in some cases with wedjat-eyes, creating a fitting composition). The two eyes face the viewer. In all cases except the two latest examples in pGreenfield, Medjed’s trunk is surrounded with a characteristic sling that is tied at the front and placed above20 or below the eyes. The fact that on all papyri except pCologny-Geneva C this attribute is shown below the eyes suggests that it might be a belt21.

The first iconographic typology of the image of Medjed was proposed by Bernard Bruyère (1939, p. 183, fig. 77). He distinguished four types: 1—a god with a sling/headband over the eyes; 2—a god with a sling (belt?) below the eyes; 3—a god without a sling/headband; 4—a god without a headband and with legs splayed apart (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The iconography of Medjed after Bernard Bruyère (1939, p. 183, fig. 77): 1—no. 4; 2—nos 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; 3, 4—no. 5.

Ilaria Cariddi proposes a rather similar typology of Medjed’s iconography (Cariddi 2018, pp. 201–2; Cariddi and Iannarilli 2020, pp. 86–87), which I present here in Table 2.

Table 2.

The iconographic typology of the image of Medjed after Ilaria Cariddi (2018, p. 201).

While the iconographic typology of the image of the Medjed does not raise significant issues for discussion, its explanation remains problematic. Some scholars confine themselves to pointing out the strangeness of this image (Niwiński 1989, p. 122 (“a strange figure of Medjed”); Lenzo 2023, pp. 68, 69 (“a strange conical figure with two eyes and two legs”)). According to Milde (1991, p. 44), “it has the appearance of a conical cover, tightened by legs in a straddle. Maybe it is not a cover at all but the very body of the demon, for it is provided with two staring eyes”. I briefly proposed that the covered body of Medjed could be explained by his invisibility, which is mentioned in the text of Spell 17 (see above; Tarasenko 2012, p. 285). Bernard Bruyère and Terence DuQuesne saw in Medjed the image of an upended oil vessel (nw-vase, Gardiner’s sign W24:  ) (Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–85; DuQuesne 2008, p. 19 (“a personification of a vessel for sacred oils”)). At the same time, DuQuesne (2008, p. 20) saw a possible connection between Medjed and the local shrine of Hathor at Asyut (See also DuQuesne 2002, pp. 39–60; Warkentin 2018, pp. 200–9). Cariddi (2018, pp. 203–4) suggests that the iconography may be based on a vessel with a sealed lid. She also cautiously observes a possible connection with the images of a fetish/symbol of the Thinite nome (TꜢ-wr, Gardiner’s sign R17:

) (Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–85; DuQuesne 2008, p. 19 (“a personification of a vessel for sacred oils”)). At the same time, DuQuesne (2008, p. 20) saw a possible connection between Medjed and the local shrine of Hathor at Asyut (See also DuQuesne 2002, pp. 39–60; Warkentin 2018, pp. 200–9). Cariddi (2018, pp. 203–4) suggests that the iconography may be based on a vessel with a sealed lid. She also cautiously observes a possible connection with the images of a fetish/symbol of the Thinite nome (TꜢ-wr, Gardiner’s sign R17:  (Gardiner 1957, p. 503)) or a mace-head.

(Gardiner 1957, p. 503)) or a mace-head.

) (Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–85; DuQuesne 2008, p. 19 (“a personification of a vessel for sacred oils”)). At the same time, DuQuesne (2008, p. 20) saw a possible connection between Medjed and the local shrine of Hathor at Asyut (See also DuQuesne 2002, pp. 39–60; Warkentin 2018, pp. 200–9). Cariddi (2018, pp. 203–4) suggests that the iconography may be based on a vessel with a sealed lid. She also cautiously observes a possible connection with the images of a fetish/symbol of the Thinite nome (TꜢ-wr, Gardiner’s sign R17:

) (Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–85; DuQuesne 2008, p. 19 (“a personification of a vessel for sacred oils”)). At the same time, DuQuesne (2008, p. 20) saw a possible connection between Medjed and the local shrine of Hathor at Asyut (See also DuQuesne 2002, pp. 39–60; Warkentin 2018, pp. 200–9). Cariddi (2018, pp. 203–4) suggests that the iconography may be based on a vessel with a sealed lid. She also cautiously observes a possible connection with the images of a fetish/symbol of the Thinite nome (TꜢ-wr, Gardiner’s sign R17:  (Gardiner 1957, p. 503)) or a mace-head.

(Gardiner 1957, p. 503)) or a mace-head.4. Discussion

The group under discussion representing three “demons”, one of whom is Medjed, is characteristic only of the 21st Dynasty, and indeed can serve as a dating criterion. Andrzej Niwiński describes it as “innovative”, noting first of all a specific image of Medjed, who is always shown as the last “demon” of the group of three, and is unknown in the iconography of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead of the New Kingdom and Saite-Ptolemaic periods (Niwiński 1989, p. 122). Niwiński has also assembled the group (“family”) of seven rolls, on several of which he has noted that these three demons are shown (Niwiński 1989, p. 122). However, the first scholar to identify this corpus was Bernard Bruyère, who dated all the sources to the 18th Dynasty, on the basis of supposed stylistic similarities in the drawings with earlier examples (Bruyère 1939, pp. 182–84). Henk Milde states that in the papyri of Mwt-m-wjꜢ (pBerlin P. 3157) and Ꜥnḫ⸗s-n-Mwt (pCairo S.R. VII. 10255), mentioned by Niwiński (pBerlin 27 and pCairo 90), there are no images of Medjed, but he confirms their presence in the papyri of TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw (pCairo S.R. VII. 10222 (pCairo 59)) and Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw (pCairo J.E. 95658 (pCairo 19)), where they are included in vignettes to Spells 77 and 148 (Milde 1991, p. 45, fn. 39).

Milde, however, came to the conclusion that the “three demons do not belong together”, on the basis of the scenes in the papyrus of Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw (pGreenfield) (No. 5), and he proposes that in all sources Medjed acts as an independent character (Milde 1991, p. 44, fn. 36). I cannot agree with him, because the hieratic pGreenfield is established as being as the latest copy of the illustrated Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead from the Third Intermediate Period and could have been unique in its time, so that it cannot offer a basis for reconstructing the primary form of the iconography and its semantics.

In five earlier rolls (Nos. 4, 6, 7, 8, 9), all the three “demons” are represented together in the context of Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead. One of the other “demons” has the head of a vulture, while the second has two falcon heads with maat-feathers. In many sources, they are depicted with knives (Nos. 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Identifying these “demons” is difficult. The one with two falcon heads may be associated with the following passage in Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead: Ḥr pw wnn⸗f m tpwy wnn wꜤ ẖr mꜢꜤt ky ẖr jsft dd⸗f jsft n jr zy mꜢꜤt n jy ẖr⸗z “It is Horus with two heads, one bearing what is Truth (maat) and the other what is Evil (isefet), giving evil to the one who does it, and Truth to the one who comes bearing it” (after pNb.sni pLondon BM EA 9900, col. 64; Lapp 2006, pp. 218, 220; Quirke 2013, p. 60). As Milde (1991, p. 43) noted according to the image of this “demon”, “it may come as a surprise that both heads carry mꜢꜤt-feather. But it seems that Horus’s wrong-doing is an act of justice, too. For it is bestowed on those who are themselves guilty of wrong doing”. So the punishment of Evil in this case is a part of Justice. It is more difficult to identify the “demon” with a vulture head (might it be Shesemu as a figure close to Medjed?). There is no doubt that this entire triad relates to Sections 23–24 of Spell 17B of the Book of the Dead (Quirke 2013, p. 60), which are connected with ideas of posthumous reward.

5. Conclusions

To sum up, it is obvious that a principal value for creators of the visual image of Medjed was his invisibility (nn mꜢꜢ.n.tw⸗f), twice underlined in the text of Spell 17. Evidently, the very invisibility of this deity caused his unusual iconography, like Lewis Carroll’s hero Humpty Dumpty.22 Medjed has a conical body (as in pGreenfield) or looks like a rectangle with a round top. Medjed is depicted with human legs and without a true head—or with a cover hiding his face—but with eyes indicated and wearing a belt. All these details foreground his peculiar “covered”, “concealed” image. Medjed is the deity who had corporeal form but nevertheless essence, inaccessible to sight, as is emphasized by the characteristic cape that hides his shape. Thus, the iconography of Medjed presents a curious example of an attempt by Egyptian artists to depict an unimaginable being. It is an example of the creative endeavours of Egyptian artists during the 21st Dynasty.

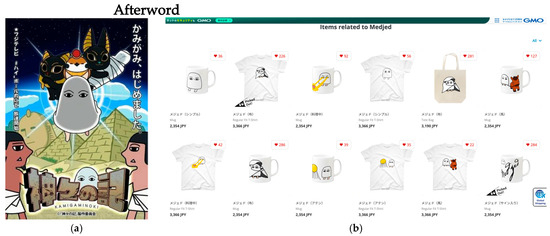

It is a matter of some surprise that the ancient image of Medjed has gained considerable popularity in modern popular culture in Japan (anime, computer games, etc.), both visually and in its essential form—invisibility (Cromwell 2022, pp. 23–25) (Figure 12) In ancient Egyptian art this image did not survive beyond the Third Intermediate period and seems to have been forgotten. It is therefore most unexpected that it should receive a “second life” three millennia later; but that is a topic for a different study of modern culture and its ancient antecedents.

Figure 12.

(a,b) The image of Medjed as an element in modern Japanese popular culture ((a) the cute gods of the animation series Kamigami no Ki (“Chronicles of the Gods”). Source: MyAnimeList (after Salvador 2017, p. 19, fig. 12); (b) various products with Medjed images on the Suzuri online shop (https://suzuri.jp/, accessed on 29 June 2025)).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

The author is deeply grateful to John Baines (Oxford), Glenn Janes (Manchester), Henk Milde (Leiden) and the anonymous reviewers for their kind help in reading the article and their useful remarks and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sources with an image of Medjed (Third Intermediate Period).

Table A1.

Sources with an image of Medjed (Third Intermediate Period).

| No. | Document | BD 17 Vignette/Type by Cariddi (2018) | Type by Niwiński (1989) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ꜥnḫ⸗s-n-Mwt pCairo J.E. 95637; S.R. IV. 528 Cursive Hieroglyphic Late 21st Dynasty Thebes Unpublished Bibliography: Niwiński (1989, p. 255 (pCairo 4)); Tarasenko (2012, p. 382 (5)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, pp. 198, 200 (8)). | Polychrome Figure 2 M.3 | BD.III.1b + A.II.3 |

| 2 | Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCairo J.E. 95658/S.R. IV. 556 Cursive Hieroglyphic Late 21st Dynasty Thebes Unpublished Bibliography: Bruyère (1939, p. 184, fig. 78); Niwiński (1989, p. 260 (pCairo 19)); Tarasenko (2012, p. 382 (6)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (7)). | Polychrome Figure 3 M.2 | BD.II.1 |

| 3 | TꜢ-bꜢk-n-Ḫnsw pCairo S.R. VII. 10222 Cursive Hieroglyphic Middle—late 21st Dynasty Thebes Unpublished Bibliography: Bruyère (1939, p. 183, fig. 77, 2); Niwiński (1989, p. 274 (pCairo 59)); Tarasenko (2012, p. 383 (2)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (6)). | Polychrome Figure 4 M.3 | BD.II.1 |

| 4 | Jnj-pḥ⸗f-nḫt pCologny-Geneva C (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana) Cursive Hieroglyphic Middle 21st Dynasty Thebes Bibliography: von Bissing (1928), Taf. I; Niwiński (1989, p. 308 (pGeneva)); Sallé (1990, pp. 28–35); Bickel (2001, pp. 117–34, fig. 32, 39); Heerma van Voss (2008, pp. 163–66); Tarasenko (2012, pp. 383–84 (8)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (4)). | Polychrome Figure 5b,c M.1 | BD.II.1 |

| 5 | Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw (Naville: Ec) pLondon BM EA 10554 (pGreenfield) Hieratic and Cursive Hieroglyphic Late 21st Dynasty—early 22nd Dynasty Thebes Bibliography: Budge (1912); Lenzo (2023); Niwiński (1989, p. 338 (pLondon 61)); Quirke (1993, pp. 50 (Nr. 145), 79 (fn. 145)); Rößler-Köhler (1999, pp. 95–98); Tarasenko (2012, pp. 381–82 (2)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 200 (9)). | Monochrome Figure 6 M.4 | BD.III.2 |

| 6 | Ꜥnḫ⸗f-n-Ḫnsw pCologny-Geneva CI (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana) Cursive Hieroglyphic 21st Dynasty Thebes Unpublished Bibliography: Valloggia (2001, p. 141); Tarasenko (2012, p. 384 (9)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 84); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (1)). | Monochrome Figure 7 M.2 | − |

| 7 | TꜢ-nt-jmntt-hrt-jb pCologny-Geneva CII (Bibliotheca Bodmeriana) Cursive Hieroglyphic 21st Dynasty Thebes Unpublished Bibliography: Valloggia (2001, p. 142); Tarasenko (2012, p. 384 (10)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (2)). | Monochrome Figure 8 M.2 | − |

| 8 | Nsy-Ḫnsw pTurin 1818 Cursive Hieroglyphic 21st Dynasty Unpublished Thebes Bibliography: Rößler-Köhler (1999, pp. 124–25); Tarasenko (2012, p. 384 (11)); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (3)). | Monochrome Figure 9b,c M.2 | − |

| 9 | Djw-sw-n-Mwt (var. Dmy-n-Mwt) pLondon BM EA 9948 Cursive Hieroglyphic Middle—late 21st Dynasty Thebes Bibliography: Shorter (1938); Niwiński (1989, p. 322 (pLondon 8)); Quirke (1993, pp. 35 (Nr. 45), 73 (fn. 45)); Rößler-Köhler (1999, pp. 123–24); Tarasenko (2012, pp. 384 (13); 385, fig. 5); Cariddi and Iannarilli (2020, p. 85); Cariddi (2018, p. 198 (5)). | Monochrome Figure 10b M.2 | BD.II.1 |

| 10 | PꜢ-dj-Ḫnsw Coffin Lyon Musée des Beaux-Arts H 2320–2321 (interior wall of the lid of the inner coffin) Cursive Hieroglyphic 21st Dynasty Thebes Bibliography: Jamen (2015); Tarasenko (2016, pp. 18–19, fig. 27a). | Monochrome Figure 11 M.2 | − |

Notes

| 1 | “Since the God is in everything and everything is in the God ‘who made millions of himself,’ there are practically no limits of the ways, in which He can be imagined, named or represented” (Niwiński 2000, p. 28). |

| 2 | “Only one imaginable or imaginary shape of God officially accepted by theologians” (Niwiński 2000, p. 28). |

| 3 | The database of Egyptian “demons” from the Middle and New Kingdoms was created by the Ancient Egyptian Demonology Project (https://voices.uchicago.edu/demonthings/demonbase/) (accessed on 29 June 2025), founded by Kasia Szpakowska (https://www.swansea.ac.uk/arts-and-humanities/arts-and-humanities-research/our-recent-research-projects/ancient-egyptian-demonology/) (accessed on 29 June 2025). |

| 4 | Chegodaev translates “who throws with his eyes” (“мечет глазами”) (Chegodaev 2002, p. 100), but in all New Kingdom examples of the spell the form “his eye” (jrt⸗f) is given in the singular (Lapp 2006, pp. 236–237). See Grapow (1917 (Urk. V) (Überschrift), pp. 26–27); Allen (1960, p. 90); Allen (1974, p. 30); Barguet (1967, p. 62); Hornung (1979, p. 71); Faulkner (2001, p. 48; LGG III, p. 476) (“der mit seinem Auge strahlt”); Quirke (2013, p. 60). |

| 5 | For etymology of the root mḏd see Takács (2008, p. 869–83). |

| 6 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134467, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134467>. |

| 7 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134446, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134446>. |

| 8 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134491, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134491>. |

| 9 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134423, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134423>. |

| 10 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134519, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134519>. |

| 11 | Most likely, Nsy-tꜢ-nbt-jšrw died before the beginning of the Twenty-second Dynasty. |

| 12 | The image returns to a scene XVIII in Spell 17 of the Ramesside Book of the Dead (Milde 1991, p. 39), which shows a goose and a falcon flying above it. |

| 13 | I am thankful to John Baines for this observation. |

| 14 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134678, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134678>. |

| 15 | For this scene see in detail Tarasenko (2016). |

| 16 | Nine fragments (one without a text) representing two parts of a introductory monochrome vignette were preserved (deceased in an adoration pose in front of the offering table, the figure of a deity did not remains); one fragment of a scene with a cat, a serpent, and jšd-tree, and Isis with Nephthys; one fragment of a scene with Khepry’s boat (only the vessel’s prow and one column of the text), and four fragments of the worshipping scenes. Besides, in the reconstruction of the roll in which the fragments were placed under glass, the introductory vignette was incorrectly located at the end of the roll, not at its beginning (on the right). |

| 17 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134677, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134677>. |

| 18 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134600, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134600>. |

| 19 | Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 134536, <totenbuch.awk.nrw.de/objekt/tm134536>. |

| 20 | As Glenn Janes (Manchester) kindly noted to me, the sling above the eyes recalls seshed-headbands found on the Third Intermediate Period shabtis. |

| 21 | For symbolic and magical value of a belt see e.g., Baines (1975, pp. 1–24). |

| 22 | I am grateful to Dr Henk Milde (Leiden) for this comparison. |

References

- Allen, T. George. 1960. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Documents in the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago. Oriental Institute Publications 82. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. George. 1974. The Book of the Dead or Going Forth by Day. Ideas of the Ancient Egyptians Concerning the Hereafter as Expressed in Their Own Terms. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 37. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 1995. Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism, 2nd rev. ed. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2001. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Backes, Burkhard. 2005. Wortindex zum späten Totenbuch (pTurin 1791). Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch 9. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 1975. ‘Ankh-sign, belt and penis sheath. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 3: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barguet, Paul. 1967. Le Livre des Morts des anciens Égyptiens. Paris: Éditeur. Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, Sussane. 2001. Entre angoisse et espoir: Le Livre des Morts. In “Sortir au jour”. Art égyptien de la Fondation Martin Bodmer. Catalogue. Edited by Jean-Luc Chappaz and Sandrine Vuilleumier. Cahiers de la Société d’Égyptologie 7. Genève: K. G. Saur, pp. 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyère, Bernard. 1939. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el Médineh (1934–1935). Fouilles de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 16. Le Caire: L’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. 1912. The Greenfield Papyrus in the British Museum. The Funerary Papyrus of Princess Nesitanebtashru, Daughter of Painetchem II and Nesi-Khensu, and Priestess of Amen-Râ at Thebes, about B.C. 970. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Cariddi, Ilaria. 2018. Reinventing the afterlife: The curious figure of Medjed in the Book of the Dead. In Tradition and Transformation in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress for Young Egyptologists, Vienna, Austria, 15–19 September 2015. Edited by Andrea Kahlbacher and Elisa Priglinger. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cariddi, Ilaria, and Francesca Iannarilli. 2020. Di sangue e di vino: Analisi della correlazione tra le figure oltremondane Shezmu e Medjed. In Atti del XVIII Convegno di Egittologia e Papirologia: Siracusa, 20–23 Settembre 2018. Edited by Anna Di Natale and Corrado Basile. Siracusa: Istituto Internazionale del Papiro—Museo del Papiro “Corrado Basile”, pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, Claude. 2010. Série des Papyrus du Livre des Morts de l’Égypte ancienne. Volume I: Le Papyrus de Nouou (BM EA 10477). Melchat 3. Paris: Cybele. [Google Scholar]

- Chegodaev, Мikhail А. 2002. Izrecheniya “Knigi mertvych” (Spells of the “Book of the Dead”). In Istoriya Drevnego Vostoka: Teksty i documenty (The History of the Ancient Orient: Texts and Documents). Edited by Vasilyi I. Kuzischin. Moscow: “Vyshaya shkola”, pp. 95–110. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell, Jennifer. 2022. From Pyramids to Obscure Gods: The Creation of an Egyptian World in Persona 5. Thersites 14: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuQuesne, Terence. 2002. Hathor of Medjed. Discussions in Egyptology 54: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- DuQuesne, Terence. 2008. The Great Goddess and her companions in Middle Egypt: New findings on Hathor of Medjed and the local deities of Asyut. In Mythos und Ritual: Festschrift für Jan Assmann zum 70. Geburtstag. Edited by Benedikt Rothöhler and Alexander Manisali. Berlin: LIT-Verlag, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Erman, Adolf, and Hermann Grapow. 1955. Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, 2nd ed. 5 vols. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, Raymond O. 2001. The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, 3rd ed. Edited by Carol Andrews. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Alan. 1957. Egyptian Grammar Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, 3rd rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grapow, Hermann. 1912. Das 17. Kapitel des Ägyptischen Totenbuches und Seine Religionsgeschichtliche Bedeutung. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde, Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Grapow, Hermann. 1917. Religiöse Urkunden Nebst Deutschen Vebersetzung. Ausgewählte Texte des Totenbuches. 2 vols. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. [Google Scholar]

- Hannig, Rainer. 1995. Die Sprache der Pharaonen. Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptische-Deutsch. Hannig–Lexica 1. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Hannig, Rainer. 2006. Ägyptisches Wörterbuch II. Mittleres Reich und Zweite Zwischenzeit. 2 vols. Hannig Lexica 5. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Heerma van Voss, Matthieu. 1977. Over het dateren van doadenboeken. Phoenix 23: 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Heerma van Voss, Matthieu. 1988. Een Man en Zijn Boekrol: College Gegeven aan het Einde van zijn Ambtsperiode als Gewoon Hoogleraar aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op Vrijdag 9 December 1988. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Heerma van Voss, Matthieu. 2008. Beginning and End in the Book of the Dead of the 21st Dynasty. In Egypt and Beyond. Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko upon his Retirement from the Wilbour Chair of Egyptology at Brown University June 2005. Edited by Stephen E. Thompson and Peter Der Manuelian. Providence: Brown University, pp. 163–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1979. Das Totenbuch der Ägypter. Zürich: Artemis. [Google Scholar]

- Jamen, France. 2015. Le cercueil de Padikhonsou au musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon (XXIe dynastie). Studien zum Altägyptischen Totentexten 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lapp, Günther. 2006. Totenbuch Spruch 17. Synoptische Textausgabe nach Quellen des Neuen Reiches. Totenbuchtexte 1. Basel: Orientverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Leitz, Christian, ed. 2002. Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. 8 vols. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 111–116, 129. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzo, Giuseppina. 2023. The Greenfield Papyrus: Funerary Papyrus of a Priestess at Karnak Temple (c. 950 BCE). British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 15. Leuven, Paris and Bristol: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Lesko, Leonard H. 2002. A Dictionary of Late Egyptian. 2 vols. Providence: BC Scribe Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, Rita, and Martin Andreas Stadler, eds. 2023. The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Oxford Handbooks. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milde, Henk. 1991. The Vignettes in the Book of the Dead of Neferrenpet. Egyptologische Uitgaven 7. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Irmtraut. 1988. Untersuchungen zu den Totenbuch-Papyri der 18. Dynastie. Kriterien ihren Datierung. London and New York: Kegan Paul Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer, Otto, and Richard A. Parker. 1960. Egyptian Astronomical Texts I: The Early Decans. Brown Egyptological Studies 3. Providence: Brown University Press. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Niwiński, Andrzej. 1988. The Wifes of Pinudjem II—A Topic for Discussion. The Journal of Egyptian Archeology 74: 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwiński, Andrzej. 1989. Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries B.C. Orbis Biblicus et Orientales 86. Frieburg and Göttingen: Universitätsverlag. Frieburg and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprech. [Google Scholar]

- Niwiński, Andrzej. 2000. Iconography of the 21st dynasty: Its main features, levels of attestation, the media and their diffusion. In Images as Media: Sources for the Cultural History of the Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (1st Millennium BCE). Edited by Christoph Uehlinger. Orbis Biblicus et Orientales, 175. Frieburg and Göttingen: Universitätsverlag, Frieburg and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprech, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Bengt Julius. 1963. Der Gott Schesemu und das Wort Mḏd. Orientalia Suecana 12: 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen. 1993. Owners of Funerary Papyri in the British Museum. British Museum Occasional Paper 92. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen. 2013. Going out in Daylight, prt m hrw, the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. Translation, Sources, Meanings. GHP Egyptology 20. London: Golden House. [Google Scholar]

- Rößler-Köhler, Ursula. 1979. Kapitel 17 des Ägyptischen Totenbuches. Untersuchungen zur Textgeschichte und Funktionen eines Textes der Altägyptischen Totenliteratur. Göttinger Orientforschung IV, 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rößler-Köhler, Ursula. 1999. Zur Tradierungsgeschichte des Totenbuches der 17. und 22. Dynastie (Tb.17). Studien zum altägyptischen Totenbuch 3. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Sallé, Alix. 1990. Le livre des Morts de l’Égypte ancienne. Archeologia 255: 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, Rodrigo B. 2017. Medjed: From Ancient Egypt to Japanese Pop Culture. Journal of Geek Studies 4: 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shorter, Alan W. 1938. Catalogue of Egyptian Religious Papyri in British Museum. Copies of the Book PR(T)-M-HRW from the XVIIIth to the XXIInd Dynasty I: Representation of Papyri with Text. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, Gábor. 2008. Etymological Dictionary of Egyptian. Volume Three: m–. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko, Mykola. 2012. The vignettes of the Book of the Dead Chapter 17 during the Third Intermediate Period (21st–22nd Dynasties). Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 41: 379–94, Taf. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko, Mykola. 2014. The illustrations of the Book of the Dead Chapter 17 during the 18th Dynasty. In Doislams’kyy Blyz’kyy Skhid: Istoriya, Relihiya, Kul’tura [Pre-Islamic Near East: History, Religion, Culture]. Edited by Mykola Tarasenko. Kyiv: IS NANU, pp. 241–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko, Mykola. 2016. Studies on the Vignettes from Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead I: The Image of mc.w BdSt in Ancient Egyptian Mythology. Archaeopress Egyptology 16. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasenko, Mykola. 2020. The vignettes of Chapter 17 from the Book of the Dead as found in the Papyrus of Nakht (London BM EA 10471): At the beginning of the Ramesside Iconographic Tradition. Journal of the Hellenic Institute of Egyptology 3: 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Valloggia, Michel. 2001. Les manuscripts hiératiques et hiéroglyphiques de la Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. In “Sortir au jour”. Art égyptien de la Fondation Martin Bodmer. Catalogue. Edited by Jean-Luc Chappaz and Vuilleumier Sandrine. Cahiers de la Société d’Égyptologie 7. Genève: K. G. Saur, pp. 135–45. [Google Scholar]

- von Bissing, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1928. Totenpapyros eines Gottesvaters des Amon. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 63: 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warkentin, Elizabeth Rose. 2018. Looking Beyond the Image: An Exploration of the Relationship between Political Power and the Cult Places of Hathor in New Kingdom Egypt. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).