Ancient Earth Births: Compelling Convergences of Geology, Orality, and Rock Art in California and the Great Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Current Debates

Anthropologists are by no means in agreement on the historical validity of events and locations occurring in myths. Some, like Robert Lowie, completely rejected all myths as accurate sources of any historical fact, while others, like Paul Radin, believed that historical events and past cultural patterns can be reconstructed from myths. Perhaps the majority, though, subscribe to Edward Sapir’s belief that authentic information can be found in myths when it is corroborated by other lines of evidence (e.g., archaeological, linguistic, or ethnographic).

3.2. Literature Review

- Restricted geographical scale observations;

- Reliance on mainly qualitative (rather than quantitative) information;

- Lack of a built-in drive to accumulate more and more facts;

- Slower speed in the accumulation of facts;

- More reliance on trial-and-error, rather than on systematic experimentation;

- Limited scope for the verification of predictions;

- Lack of interest in general principles or theory-building.

3.3. Previous Research

3.4. Theoretical Approaches

3.5. Geomythology

3.6. Research Gaps

3.7. Setting the Stage

Black Mountain (in the White Mountains, on the east side of the valley) (Steward 1936, p. 364), Round Valley (just north of Owens Valley) (Steward 1936, p. 365), and Long Valley (just north of Long Valley) (Steward 1936, p. 366) … “All the Indian tribes” (Steward 1936, p. 366) were thus created, but the Miwok, Shoshoni, and Modoc were mentioned by name. There is no indication of any movement of Shoshoni groups to different places.

In many versions … Coyote pursues the daughter, as in a hunt, and finally catches up to her at the edge of a large body of water. In other versions, the home of the women is on an island surrounded by water or across a body of water from Coyote (M2, M4, M7, M9, M11, M12, M13, M14, Ml5). Water in opposition to Coyote (a land animal) is also shown in some myth variants by his need to change into a water skate or water skipper in order to cross the water.

3.8. Ancient Floods on the Pacific Rim

This earthquake was probably a Mw 9, based on the size of the associated tsunami on the Japanese coast as documented in written records. An earthquake of such magnitude probably ruptured the entire ~1200 km length of the subduction zone.

~3–4 every 1000 yr. Then, starting ~2800 cal. yr. B.P., there was a 930–1260 yr. interval with no tsunamis. That gap was followed by a ~1000 yr. period with 4 tsunamis … Local tsunamis entered Bradley Lake an average of every 390 yr., whereas the portion of the Cascadia plate boundary that underlies Bradley Lake ruptured in a great earthquake less frequently, about once every 500 yr. Therefore, the entire length of the subduction zone does not rupture in every earthquake.

In central and southern California and the western Great Basin, it is less probable that the tsunamis associated with the Cascadia subduction zone would have had an appreciable impact on the environment and people. Nevertheless, there are numerous flood narratives recorded among the Northern Paiute, Western Shoshone, and Southern Paiute of these areas, as well as the Colorado Plateau.

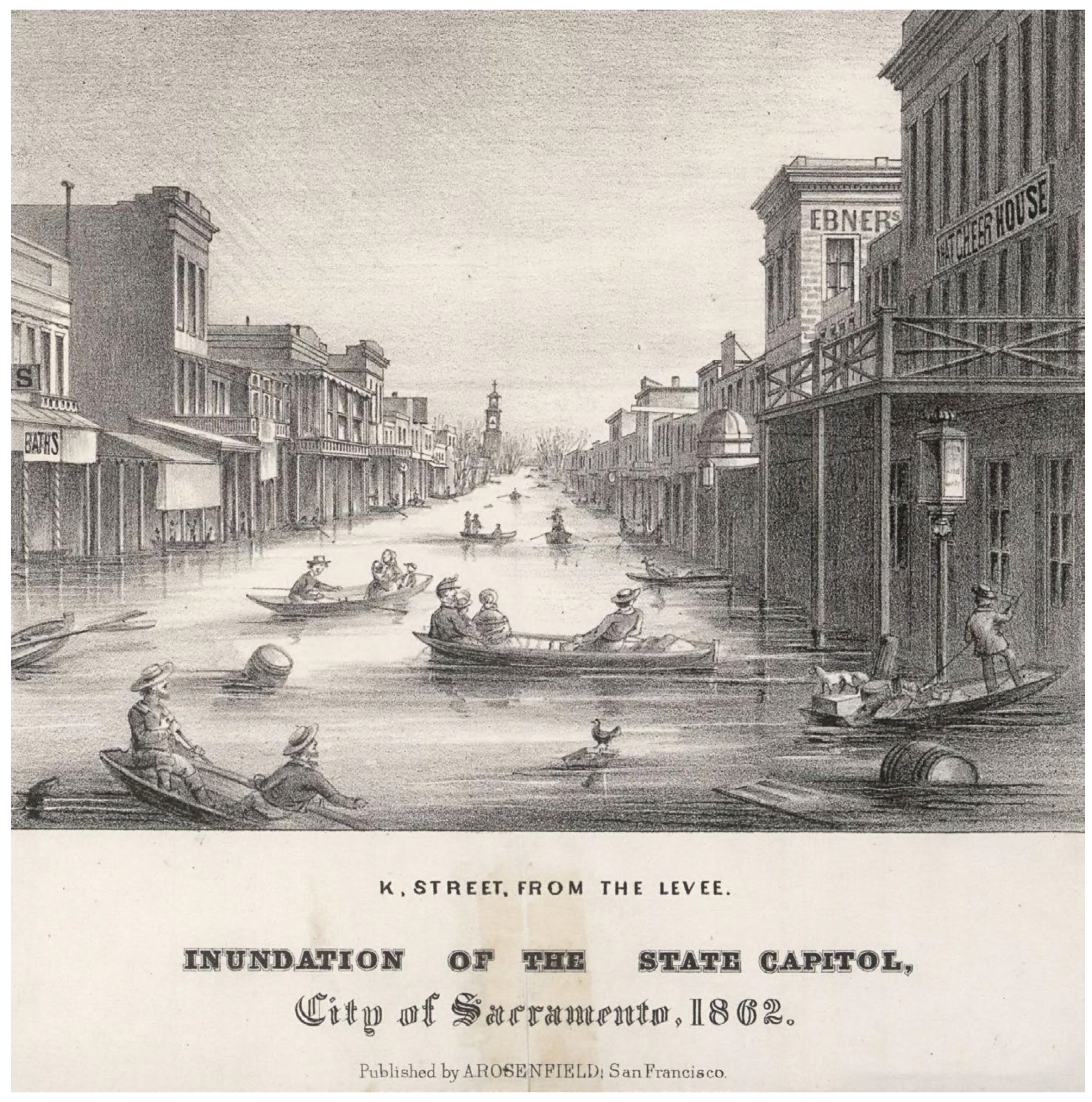

We are informed that the Indians living in the vicinity of Marysville [ghost town in Nye County, Nevada on the present-day Yomba Shoshone Reservation] left their abodes a week or more ago for the foothills predicting an unprecedented overflow. They told the whites that the water would be higher than it has been for thirty years and pointed high up on the trees and houses where it would come. The valley Indians have traditions that the water occasionally rises 15 or 20 feet higher than it has been at any time since the country was settled by whites, and as they live in the open air and watch closely all the weather indications, it is not improbable that they may have better means than the whites of anticipating a great storm.

Archaeological chronologies of cultural transitions in the southwestern USA (McBrinn and Cordell 1997) do not reflect a -200-yr periodicity, or any significant correlation with flood deposits in the SBB”.

For the past several decades, paleohydrologist Victor Baker of the University of Arizona has been using techniques similar to [Koji] Minoura’s to study the flood history of the Colorado Plateau. Like Minoura [who discovered three major earthquakes linked to tsunamis over three thousand years], he’s found that floods much larger than any in recorded history are routine occurrences.

A fluctuating, increasingly saline, terminal lake [that] survived into the late Holocene until upstream water diversions to the Los Angeles Aqueduct began in 1913. Shoreline fragments and beach stratigraphy indicate that the lake reached its highest late Pleistocene level around 23.5 ka, during the Last Glacial Maximum, when it was fed by meltwaters from Sierra Nevada glaciers and spilled southward to Searles Lake and beyond. The lake then fell to relatively low levels after 16.5 ka before experiencing terminal Pleistocene oscillations related to hydroclimatic forcing, which involved changing regional precipitation regimes rather than major inputs from Sierra Nevada glaciers. Two major transgressions occurred. The first culminated around 14.3 ka and was probably related to a cooler, wetter regional climate. The second culminated around 12.8 ka and was linked to the earlier wetter phase of the Younger Dryas cold event. However, the high late Pleistocene shoreline is deformed, and the highest beach ranges in elevation from 1140 m to 1167 m above sea level. If the terminal Pleistocene lake overflowed, as suggested here, then its outlet has also been raised since 12.8 ka.

It is a turbulent land; occasional torrential downpours send walls of water plunging down canyons scouring everything … the alluvial fans and depressions where they deposit mud and boulders; winds abrade granite boulders and outcroppings; winter winds from the north cut like obsidian blades; and oven-like summers drain the resolve from the most determined explorers, reddish cinder cones and dark malpais (rough lava) outcroppings and walls are silent testimonies to profound geologic event from the past.

4. Ethnogenesis

At first, the earth is covered with water and so the women play a dominant role. When Coyote breaks the vagina dentata, the roles shift and it is Coyote and land that are dominant.

Salt Creek and the Amargosa River discharged all the way to Badwater Basin. About 80 square miles of the salt pan was flooded; in the lowest part, between Badwater and Eagle Borax, the water was 2 to 3 feet deep. If the average depth over the 80 square miles was 1 foot, the volume of water was about 50,000-acre feet … [By contrast], the Holocene lake was ten times as deep as the 1969 lake and covered at least four times as much surface; the volume of water therefore must have been about forty times as large.(ibid.)

Once placed on the land, two native women instructed the coyote to carry a large, pitched water-basket with him on his journey into the Basin area. Coyote was specifically told not to open the lid. Moved by irrepressible curiosity, he periodically opened the basket during his trip. The beings concealed inside jumped out here and there. The Newe believed this explains why they live over a large area. Today, family groups can be found in Death Valley, the Reese River Valley, Ruby Valley, the South Fork Valley, and numerous other places, primarily in Nevada.

The Saline Valley cable tramway was constructed between 1910 and 1913 by the Saline Valley Salt Works to transport pure salt deposits from the salt lake in Saline Valley across the Inyo Mountains to Owens Valley. There it was milled and shipped via the Carson & Colorado narrow gauge railroad north to Nevada. Gondola cars carrying 800 pounds of salt, traversed the 13.5 [mile] series of tramways at a rate of 20 tons per hour over the Inyo Mountains. A total of 30,000 tons of high grade salt was carried over the tramway on and off through the early 1930s.

4.1. Petroglyphs as Embodied Geological Memory: Visual Narratives of Earth Changes

4.2. Visual Encoding of Ethnogenesis Narratives

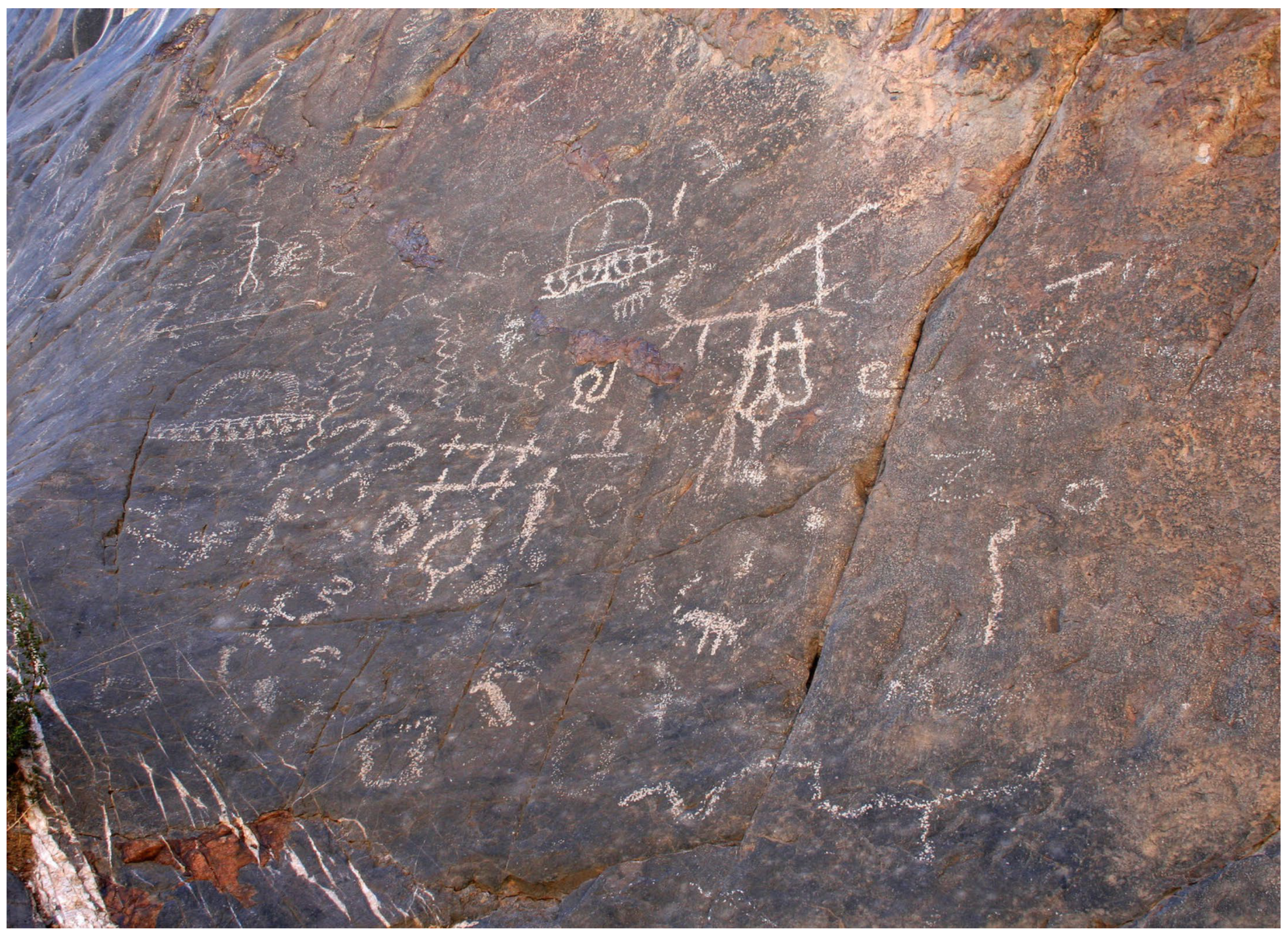

- Bighorn Sheep with Exaggerated Anatomy: The depicted sheep (Ovis canadensis), with a “long swollen neck”, encodes both biological knowledge (rutting behavior) and mythological function (the instrument of transformation), linking natural animal behavior to cosmological change (Myers 1997, p. 37; Whitley 1982, p. 263).

- Coyote as Water Carrier: Coyote’s (Canis latrans) presence connects the visual narrative to the flooding and water dispersal elements of multiple ethnogenesis accounts (Lowie 1924a; Sapir 1931; Steward 1936, 1943; Kelly 1938; Fowler and Fowler 1971), marking him both protagonist and geological agent. Both snake and zigzag motifs are alternately correlated to seismic activity and moving water (Hough 2007).

- Vagina Dentata: Semi-circles with a zigzag foundation, Ocean Woman and her daughter, Louse, the target of coyote’s advances (Whitley 1982, p. 263). (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

- Geological Integration: The positioning of key imagery relative to the natural crack in the panel surface suggests the artists understood these locations as places where mythological events literally occurred, making the petroglyphs site-specific commemorations rather than generic illustrations (Figure 8).

4.3. Citational Rock Art

- The location where catastrophic floodwaters receded into the earth (Coyote’s Hole?);

- The metaphorical “opening” of the earth following the removal of the vagina dentata;

- A geological “scar” marking the transformation from the water-dominated previous world to the current terrestrial landscape.

4.4. Spatial Relationships and Cultural Geography

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Documentation

5.2. Evidence of Ancient Flooding

The origins of the Early Archaic in the western Great Basin are obscure since sites are rare and dates scarce. The Early Archaic apparently begins somewhat later in the west than in the north and east, sometime between 5000 and 4000 B.C. It does not become visible in the archaeological record until about 2500 B.C., and it terminates between 2000 and 1500 B.C. Considering emergent paleohydrological data of paleoflooding in central California and the Colorado Plateau, it appears that scholars must once again revisit the question of the peopling of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. Great Basin archaeologists have conducted extensive research on the “Numic Problem” and more recently, “A Shoshonean Prayerstone Hypothesis” (Thomas 2019). Not coincidentally, a dearth of Paleo and Early Archaic sites in the western Great Basin appears to mirror the region exposed to the paleoflooding of Owens Lake during the late Pleistocene, suggesting the very real possibility of the destruction of archaeological sites in Ocean Woman’s and Coyote’s path. By extension, areas just beyond the pale of these events may reflect the typical archaeological signature of this modified landscape.

5.3. Discussion and Interpretation

5.4. Cultural Significance

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, John. 1990. Paleoseismicity of the Cascadia subduction zone, Evidence from turbidites off the Oregon-Washington margin. Tectonics 9: 569–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Kenneth D., and Steven G. Wesnousky. 1999. The Lake Lahontan highstand: Age, surficial characteristics, soil development, and regional shoreline correlation. Geomorphology 30: 357–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, C. Melvin, and Younger T. Witherspoon. 1986. Great Basin Numic Prehistory: Linguistics, Archaeology, and Environment. In Anthropology of the Desert West: Essays in Honor of Jesse D. Jennings. Edited by Carol J. Condie and Don Fowler. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anyon, Roger, T. J. Ferguson, Loretta Jackson, and Lillie Lane. 2000. Working Together: Native Americans and Archaeologists. Edited by Kurt E. Dongoske, Mark Aldenderfer and Karen Doehner. Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology, pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Victor R. 2006. Paleoflood hydrology in a global context. Catena 66: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, Lowell J. 1992. California Indian Shamanism. Anthropological Papers, No. 39. Menlo Park: Ballena Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Lyle V., Eugene Mitsuru Hattori, John Southon, and Ben Aleck. 2013. North America’s Oldest Petroglyphs, Winnemucca Lake, Nevada. Journal of Archaeological Science 40: 4466–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, Fikret. 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, Fikret, Carl Folke, and Madhav Gadgil. 1995. Traditional ecological knowledge, biodiversity, resilience and sustainability. In Biodiversity Conservation. New York: Springer, pp. 281–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone, Jamie Rae. 2010. Why the Earth Shakes: Pre-Modern Understandings and Modern Earthquake Science. Minneapolis: University Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, William. 1998. 1500 California Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning, a Revised Version of 1000 California Place Names by Erwin G. Gudd, Third Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchac, Margaret. 2005. Earthshapers and Placemakers: Algonkian Indian Stories and the Landscape. In Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonizing Theory and Practice. Oxford: Routledge, New York: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory. 2000. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Alex K., Richard W. Stoffle, Kathleen Van Vlack, Richard W. Arnold, Rebecca S. Toupal, Heather Fauland, and Erin C. Haverland. 2006. Black Mountain: Traditional Use of a Volcanic Landscape. Report prepared for Nellis Airforce Base-Air Command Nevada Test and Training Range Native American Interaction Program. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Edward S. 2009. Remembering: A Phenomenological Study. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. First published 1987, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, Katharine V., and Shane J. Cronin. 2008. Welcoming a monster to the world: Myths, oral tradition, and modern societal response to volcanic disaster. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 176: 407–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressman, Luther Sheeleigh, and Frank Collins Baker. 1942. Archaeological Researches in the Northern Great Basin. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank, Julie. 1991. Reading Voices- Dan Dha Ts’ Edenintth’e: Oral and Written Interpretations of Yukon’s Past. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Crum, Steven J. 1994. Po’i Pentun Tammen Kimmappeh: The Road on Which We Came, a History of the Western Shoshone. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Edward S. 1922. The North American Indian: Being a Series of Volumes Picturing and Describing the Indians of the United States, and Alaska. Edited by Frederick W. Hodge. 20 vols. (1907–1930). Norwood: Plimpton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, Charlotte. 2005. Archaeology, Ethnohistory and Oral Traditions: Approaches to the Indigenous Past. Norwegian Archaeological Review 38: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangberg, Grace. 1957. Letters to Jack Wilson, the Paiute Prophet. Anthropological Papers, N.55 Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 164: 279–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dayley, Jon Philip. 1989. Tumpisa (Panamint) Shoshone Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, Charles S., and Harald Drewes. 1965. Geology of the Ash Meadows Quadrangle Nevada-California. In Geological Survey Bulletin. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Dorson, Richard M. 1963. Current Folklore Theories. Current Anthropology 4: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorson, Richard Mercer. 1968. Introduction. Journal of Folklore Research 5: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, Harold E. 1937. Cultural Element Distributions, VI: Southern Sierra Nevada. University of California Anthropological Records 1: 53–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dundes, Alan. 1968. Oral Literature. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Echo-Hawk, Roger C. 2000. Ancient History in the New World: Integrating Oral Traditions and the Archaeological Record in Deep Time. American Antiquity 65: 267–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, Robert G. 1986. Prehistory of the Western Area. In Handbook of North American Indians, Great Basin. Edited by Warren Leonard D’Azevedo. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, vol. 11, pp. 135–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eyles, Nick, and Louise Daurio. 2015. Little Ice Age Debris Lobes and Nivation Hollows inside Ubehebe Crater, Death Valley, California: Analog for Mars Craters? Geomorphology 245: 231–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T. J. 2007. Zuni Traditional History and Cultural Geography. In Zuni Origins: Toward a Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona, p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T. J., J. Dongoske, Michael Yeatts, and Leigh Kuwanwisiwma. 2000. Hopi Oral History and Archaeology. In Working Together: Native Americans and Archaeologists. Edited by Kurt E. Dongoske, Mark Aldenderfer and Karen Doehner. Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fewkes, Walter J. 1900. Tusayan Migration Traditions. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. [Google Scholar]

- Fierstein, Judy, and Wes Hildreth. 2016. Eruptive History of the Ubehebe Crater Cluster, Death Valley, California. Menlo Park: U. Sc. Geological Survey, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Catherine S. 2008. Historical Perspectives on Timbisha Shoshone Land Management Practices, Death Valley, California. In Case Studies in Environmental Archaeology. New York: Springer, pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Don D. 1986. History of Research. In Handbook of North American Indians. Edited by Warren Leonard D’Azevedo. vol. 11, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Don D., and Catherine Fowler, eds. 1971. Anthropology of the Numa: John Wesley Powell’s Manuscript on the Numic Peoples of Western North America, 1868–1880. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Don D., Catherine S. Fowler, and Stephen Powers. 1970. The Life and Culture of the Washo and Paiutes. Ethnohistory 17: 117–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, James George. 1990. The Golden Bough. New York: Springer, pp. 701–11. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger, Chris, C. Hans Nelson, and Joel E. Johnson. 2003. Holocene Earthquake Records for the Cascadia Subduction Zone and Northern San Andreas Fault Based on Precise Dating of Offshore turbidites. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 31: 555–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, Donald K. 1993. The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamacher, Duane, Patrick Nunn, Michelle Gantevoort, Rebe Taylor, Greg Lehman, Ka Hei Andrew Law, and Mel Miles. 2023. The archaeology of orality: Dating Tasmanian Aboriginal oral traditions to the Late Pleistocene. Journal of Archaeological Science 159: 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, Henry G. 1883. Report on the Borax Deposits of California and Nevada. Third Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, Part 2. Sacramento: California State Mining Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer, Robert F., and Thomas R. Hester, eds. 1972. Notes on Northern Paiute Ethnography. Kroeber and Marsden Records. Berkeley: Archaeological Research Facility, Department of Anthropology, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Hittman, Michael. 1999. Wovoka and the Ghost Dance: A Celebration Honoring the Life and Teachings of Wovoka “The Ghost Dance Prophet”, Reno, Nevada, USA, October 9. Reno: University of Nevada Reno Campus. [Google Scholar]

- Holmer, Richard N. 1990. Prehistory of the Northern Shoshone. Rendezvous 36: 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Holmer, Richard N. 1994. In Search of the Ancestral Northern Shoshone. In Across the West: Human Population Movement and the Expansion of the Numa. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 179–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Sarah Winnemucca. 1883. Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. Boston: Cupples, Upham & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hough, Susan E. 2007. Writings on the Wall: Geological Context and Early American Spiritual Beliefs. London: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, vol. 273, pp. 107–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hugmeyer, Kaitlyn. 2014. Geomythology: Volcanic Myths and their Geological Significance. Paper presented at the Academic Excellence Showcase Schedule, Monmouth, OR, USA, May 29; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Alice. 1960. Archaeology of the Death Valley Salt Pan, California. University of Utah Anthropological Papers 47. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Anthropological. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Charles B. 1975. Death Valley: Geology, Ecology, Archaeology. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 157–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, Lynn. 2013. California Megaflood: Lessons from a Forgotten Catastrophe. Scientific American, January 1. [Google Scholar]

- Intertribal Council of Nevada. 1976. Newe: A Western Shoshone History. Reno: Intertribal Council of Nevada. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Charles N., ed. 1980. The Shoshoni Indians of Inyo County, California. The Kerr Manuscript. Independence: Eastern California Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Jesse D. 1957. Danger Cave. University of Utah Anthropological Papers, Number 27. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Andrew. 2007. Memory and Material Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer, J. C. 1990. Largest Rivers in the United States. Revised May 1990. USGS Publications. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1987/ofr87-242/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Kelly, Isabel T. 1938. Northern Paiute Tales. Journal of American Folklore 51: 364–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, Harvey M., Alan R. Nelson, Eileen Hemphill-Haley, and Robert C. Witter. 2005. Tsunami History of an Oregon Coastal Lake Reveals a 4600 yr. Record of Great Earthquakes on the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Geological Society of America Bulletin 117: 1009–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, Jeffrey R., Shannon A. Mahan, Jordon Bright, Lindsey Langer, Adam Ramirez, Kyle McCarty, and Anna L. Garcia. 2023. Pliocene–Pleistocene hydrology and pluvial lake during Marine Isotope Stages 5a and 4, Deep Springs Valley, western Great Basin, Inyo County, California. Quaternary Research 115: 160–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, Carobeth. 1976. The Chemehuevis. Banning: Malki Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, Krista. 2017. Have We Underestimated the West’s Super Floods? High Country News, February 28. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Forward by Bruno Latour. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Laylander, Don. 2004. Remembering Lake Cahuilla. The Human Journey & Ancient Life in California’s Deserts: Proceedings from the 2001 Millennium Conference, 2004. Ridgecrest: Maturango Museum, pp. 167–71. [Google Scholar]

- Leeming, David Adams, and Jake Page. 2000. The Mythology of Native North America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past is A Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, Robert Harry. 1909. The Northern Shoshone. American Museum of Natural History Anthropological Papers 2: 165–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, Robert Harry. 1924a. Notes on Shoshonean Ethnography. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 20: 185–314. [Google Scholar]

- Lowie, Robert Harry. 1924b. Shoshonean Tales. Journal of American Folk Lore 37: 1–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallery, Garrick. 1893. Picture Writing of the American Indians. Tenth Annual Report. Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology. [Google Scholar]

- Manly, William Lewis. 1928. Death Valley in ‘49. New York and Santa Barbara: Wallace Hebberd. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andrew M. 2013. Archaeology Beyond Postmodernity: A Science of the Social. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau, LaVan. 1992. The Southern Paiutes: Legends, Lore, Language, and Lineage. Las Vegas: KC Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Ronald J. 2006. Inconstant Companions: Archaeology, and North American Indian Oral Traditions. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masse, William Bruce, Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Luigi Piccardi, and Paul Barber. 2007. Exploring the nature of myth and its role in science. In Myth and Geology. Edited by Luigi Piccardi and William Bruce Masse. London: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, vol. 273, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, Adrienne. 2007. Place Names Describing Fossils in Oral Traditions. London: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, vol. 273, pp. 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- McBrinn, Maxine E., and Linda S. Cordell. 1997. Archaeology of the Southwest. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- McGhee, Robert. 2008. Aboriginalism and the problems of Indigenous archaeology. American Antiquity 73: 579–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, Alan D., and Ian Hutchinson. 2002. When the mountain dwarfs danced: Aboriginal traditions of Paleoseismic events along the Cascadia subduction zone of Western North America. Ethnohistory 49: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, Beatrice, and Sue-Ellen Jacobs. 2001. Learning to Be an Anthropologist and Remaining “Native”. Select writings. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mehringer, Peter, Jr. 1986. Prehistoric Environments. In Handbook of North American Indians. Edited by Warren L. D’Azevedo. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, vol. 11, pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, George. 1919. A Trip to Death Valley. Historical Society of Southern California Annual Publications 9: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Barbara, and William Walker, eds. 2008. Memory Work: Archaeologies of Material Practices. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mindeleff, Cosmos. 1891. Traditional History of Tusayan. In 8th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology for the Years 1886–1887. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, James. 1896. The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. In Fourteenth Annual Report (Part 2) of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Smithsonian Institution 1892–1893. Edited by John Wesley Powell. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, L. Daniel. 1997. Animal Symbolism Among the Numa: Symbolic Analysis of Numic Origin Myths. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 19: 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service (NPS). 2019. “Devil’s Hole: Death Valley National Park”. US Department of Interior. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/devils-hole.htm (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Orme, Anthony R., and Amalie Jo Orme. 2008. Late Pleistocene Shorelines of Owens Lake, California, and Their Hydroclimatic and Tectonic Implications. Geological Society of America Special Papers 439: 207–25. [Google Scholar]

- Owens Valley History. 2025. The Saline Valley Salt Works. Available online: http://www.owensvalleyhistory.com/stories/saline_valley_salt_works.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Palmer, William R. 1946. Pahute Indian Legends. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Park, William Z. 1938. Shamanism in Western North America: A Study in Cultural Relationships. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, Douglas R. 1985. Interpreting Pawnee Star Lore: Science or Myth. American Indian Cultural Research Journal 9: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardi, Luigi, and W. Bruce Masse, eds. 2007. Myth and Geology Special Publication. London: Geological Society, vol. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardi, Luigi, Caassandra Monti, Orlando Vaselli, Franco Tassi, Kalliopi Gaki Papanastassiou, and Dimitris Papanastassiou. 2008. Scent of a myth: Tectonics, geochemistry and geomythology at Delphi (Greece). Journal of the Geological Society 165: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, Darrell A. 1999. Local Knowledge in Global Context-Safeguarding Traditional Resource Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In Ethnoecology: Situated Knowledge/Local Lives. Edited by Virginia D. Nazarea. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, John W. 1873. Ute and Paiute Legends: 46 Stories. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute, Bureau of American Ethnology. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, John W. 1881. On the Evolution of Language [Annual Address of the President of the Anthropological Society of Washington, Delivered 2 March 1880]. Washington, DC: Anthropological Society of Washington, Abstract of Transactions for the First and Second Years, pp. 25–54. Reprinted in First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1879–1880, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, John W., and George Washington Ingalls. 1957. Exploring the Colorado River. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Stephen. 1976. Tribes of California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, Neil Douglas. 2005. Life in the Land: The Story of the Kaibab Deer. Master’s thesis, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, David Gilman, and Mary E. Voyatzis. 2021. Sanctuaries of Zeus: Mt. Lykaion and Olympia in the Early Iron Age. Hesperia 90: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuska, Alex K. 2023. When the Earth Was New: Memory, Materiality and the Numic Ritual Life Cycle (Preprint Version). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuska, Alex K. in press. When the Earth Was New: Memory, Materiality, and Numic Ritual. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. Available online: https://uofupress.com/books/when-the-earth-was-new/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Sadler, Barry, and Peter Boothroyd. 1994. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Environmental Impact Assessment. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Centre for Human Settlements. Canadian Environmental Assessment Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir, Edward. 1910. Song Recitative in Paiute Mythology. Journal of American Folklore 23: 455–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, Edward. 1931. The Southern Paiute Dictionary. Proceedings of the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences 65: 537–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelmann, Amdt, Carina B. Lange, and Betty J. Meggers. 2003. Paleoclimatic and Archaeological Evidence for a 200-yr. Recurrence of Floods and Droughts Linking California, Mesoamerica and South America over the Past 2000 Years. The Holocene 13: 763–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Robert P., and Allen F. Glazner. 1997. Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anne M. 1940. An Analysis of Basin Mythology. 2 vols. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anne M., and Alden C. Hayes. 1993. Shoshone Tales. Salt Lake City: University of Utah, vol. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, George I. 1979. Subsurface Stratigraphy and Geochemistry of Late Quaternary Evaporites, Searles Lake, California. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey Professional, vol. 1043. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, George I., and F. Alayne Street-Perrott. 1983. Pluvial Lakes of the Western United States. In Lake Quaternary Environments of the United States. Vol.1: The Late Pleistocene. Edited by Herbert E. Wright, Jr. and Stephen C. Porter. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Snead, James Elliot. 2008. Ancestral Landscapes of the Pueblo World. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- St. Clair, Harry H. H., and Robert H. Lowie. 1909. Shoshone and Comanche Tales. The Journal of American Folklore 22: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, Julian. 1933. Archaeological Problems on the Northern Periphery of the Southwest. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 5. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian. 1936. Myths of the Owens Valley Paiute. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 34: 355–440. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian. 1938. Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Anthropology Bulletin 120. Washington, DC: United States Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian. 1941. Cultural Element Distributions, XIII: Nevada Shoshone. University of California Anthropological Records 4: 209–360. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian. 1943. Some Western Shoshoni Myths. In Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 136. Anthropological Paper 31. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Stilltoe, Paul. 1998. The Development of Indigenous Knowledge: A New Applied Anthropology. Current Anthropology 39: 223–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Richard Arnold, and Kathleen Van Vlack Larry Eddy. 2009. Nuvagantu, “Where Snow Sits”: Origin Mountains of the Southern Paiutes. In Landscapes of Origin in the Americas. Tuscaaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Mark Q. 1993. The Numic expansion in Great Basin oral tradition. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 15: 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, David Hurst. 1994. Chronology and Numic Expansion. In Across the West: Human Population Movement and the Expansion of the Numa. Edited by David B. Madsen and Dave Rhode. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, David Hurst. 2019. A Shoshonean Prayerstone Hypothesis: Ritual Cartographies of Great Basin Incised Stone. American Antiquity 84: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, David Hurst, Lorann S. Pendelton, and Stephen C. Cappannari. 1986. Western Shoshone. In Handbook of North American Indians, Great Basin. Edited by Warren L. D’Azevedo. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 262–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin, Elizabeth. 1995. Narrating Our Pasts: The Social Construction of Oral History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, Ruth M. 2016. Memory, Place, and the Memorialization of Landscape. In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology. Edited by Bruno David. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 277–84. First published 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, Ruth M. 2019. Archaeology and Social Memory. Annual Review of Anthropology 48: 207–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, Ruth M., and Susan E. Alcock. 2003. Archaeologies of Memory. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Vansina, Jan. 1985. Oral Tradition as History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 186–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano, Dorthy B. 1973. Legends of the Earth: Their Geological Origins. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano, Dorthy B. 2007. Geomythology: Geological Origins of Myths and Legends. London: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, vol. 273, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, William J. 1958. Archaeological Investigations in Death Valley National Monument 1952–1957. Berkeley: University of California Archaeological Survey, vol. 42, pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, William J. 1977. A Half Century of Death Valley Archaeology. The Journal of California Anthropology 4: 249–58. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 1982. Notes on the Coso Petroglyphs, the Etiological Mythology of the Western Shoshone and the Interpretation of Rock Art. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 4: 262–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Philip J. 1978. Late Prehistoric Human Ecology at Lake Cahuilla, Coachella Valley. California: University of California, Department of Anthropology. [Google Scholar]

- Zedeño, Maria N., Evelyn Pickering, and François Lanoe. 2021. Oral Tradition as Emplacement: Ancestral Blackfoot Memories of the Rocky Mountain Front. Journal of Social Archaeology 21: 306–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruuska, A.K. Ancient Earth Births: Compelling Convergences of Geology, Orality, and Rock Art in California and the Great Basin. Arts 2025, 14, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040082

Ruuska AK. Ancient Earth Births: Compelling Convergences of Geology, Orality, and Rock Art in California and the Great Basin. Arts. 2025; 14(4):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuuska, Alex K. 2025. "Ancient Earth Births: Compelling Convergences of Geology, Orality, and Rock Art in California and the Great Basin" Arts 14, no. 4: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040082

APA StyleRuuska, A. K. (2025). Ancient Earth Births: Compelling Convergences of Geology, Orality, and Rock Art in California and the Great Basin. Arts, 14(4), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040082