“We Begin in Water, and We Return to Water”: Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs of Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina

Abstract

1. Introduction

Paper Layout

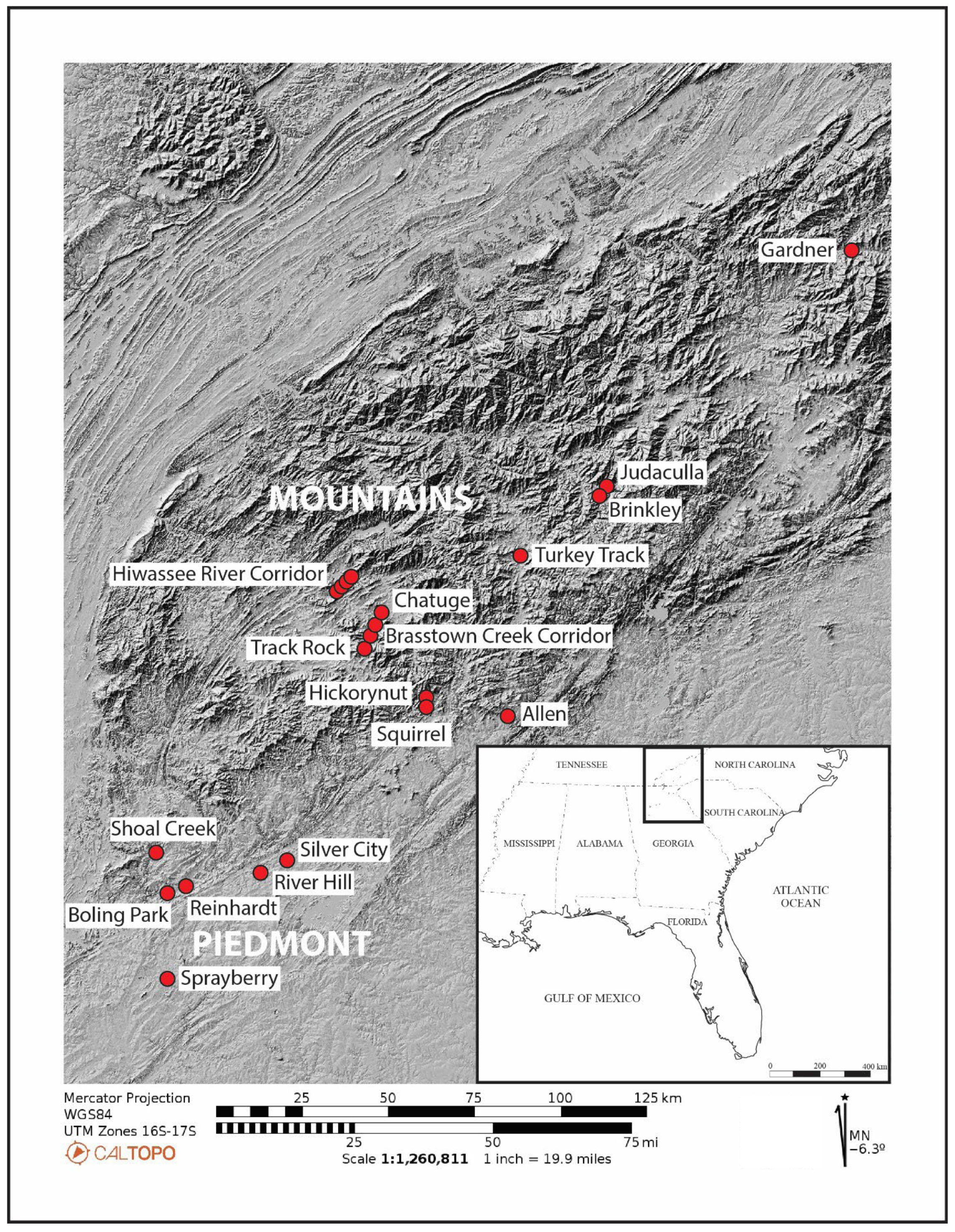

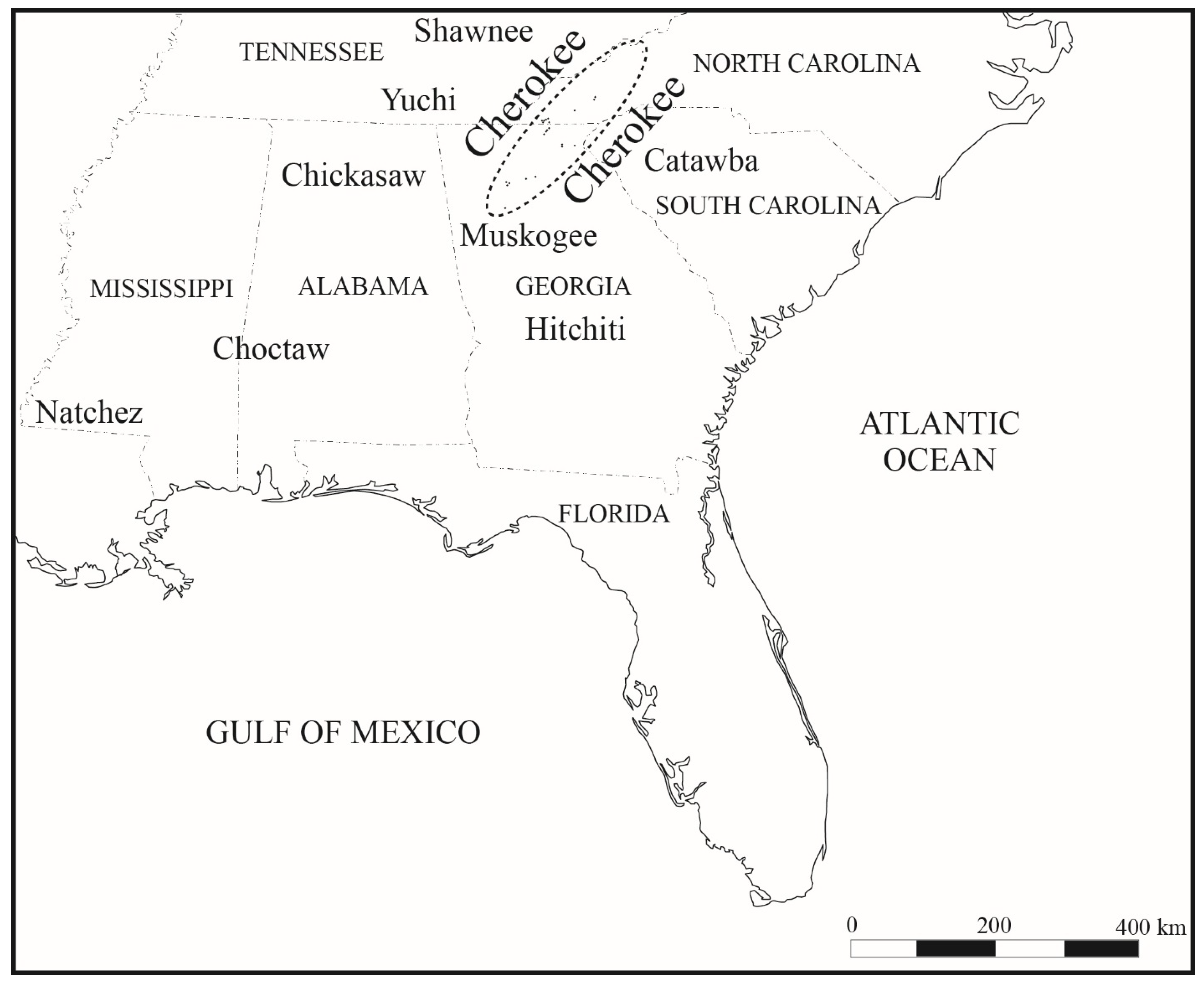

2. Formal Thesis: Archaeological and Historical Contexts

3. Formal Thesis: Recording Methods and Results

4. Formal Thesis: Recorded Petroglyph Motif Classification and Sequence

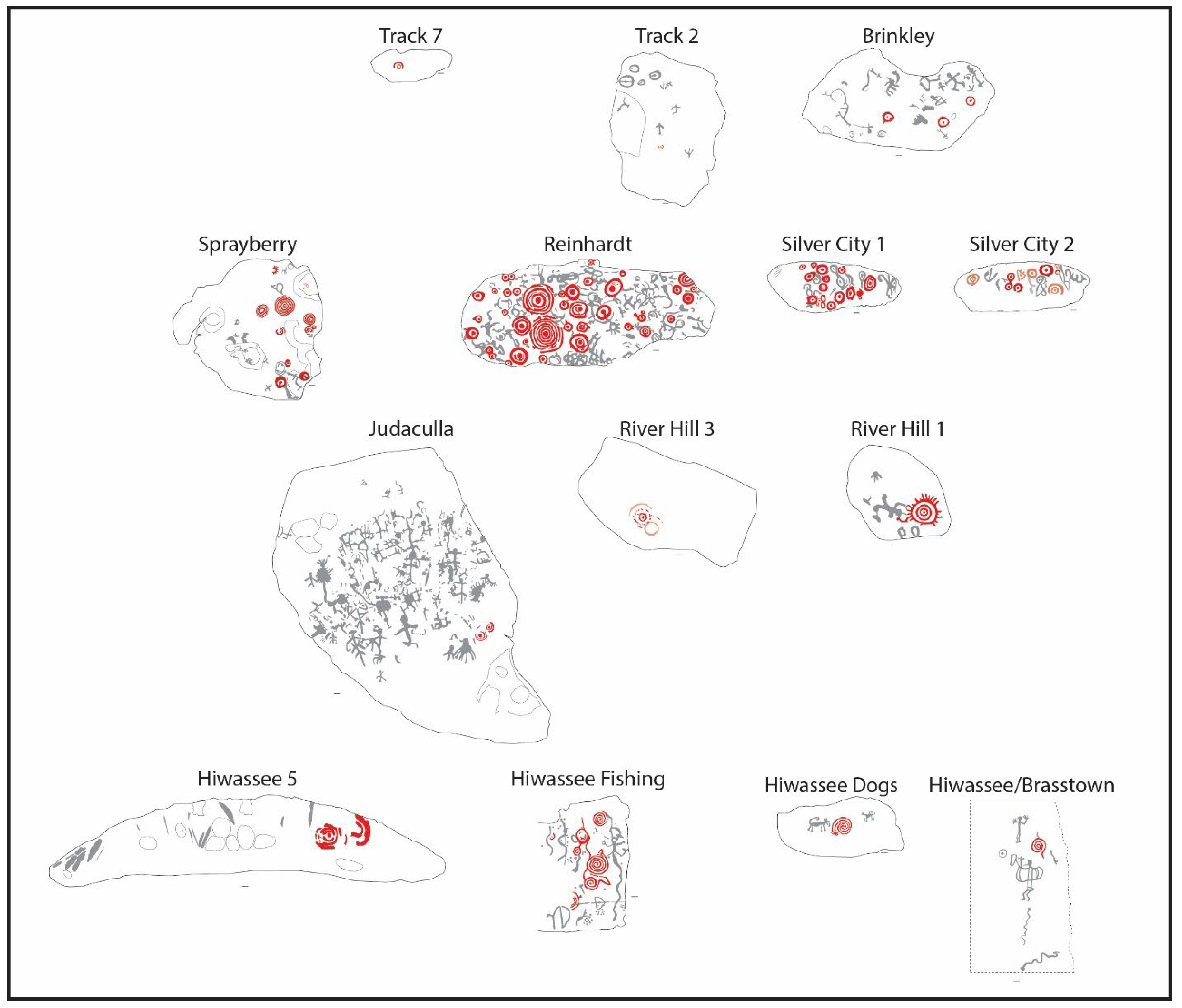

4.1. Petroglyph Motif Categories

4.2. Petroglyph Panels Sharing Motif Categories

4.3. Defining the Outer Limits of the Track Rock Tradition

4.4. Sequencing of Motif Categories

4.5. Meanders

4.6. Cupules

4.7. Soapstone Bowl Extraction Scars

4.8. Vulva-Shapes

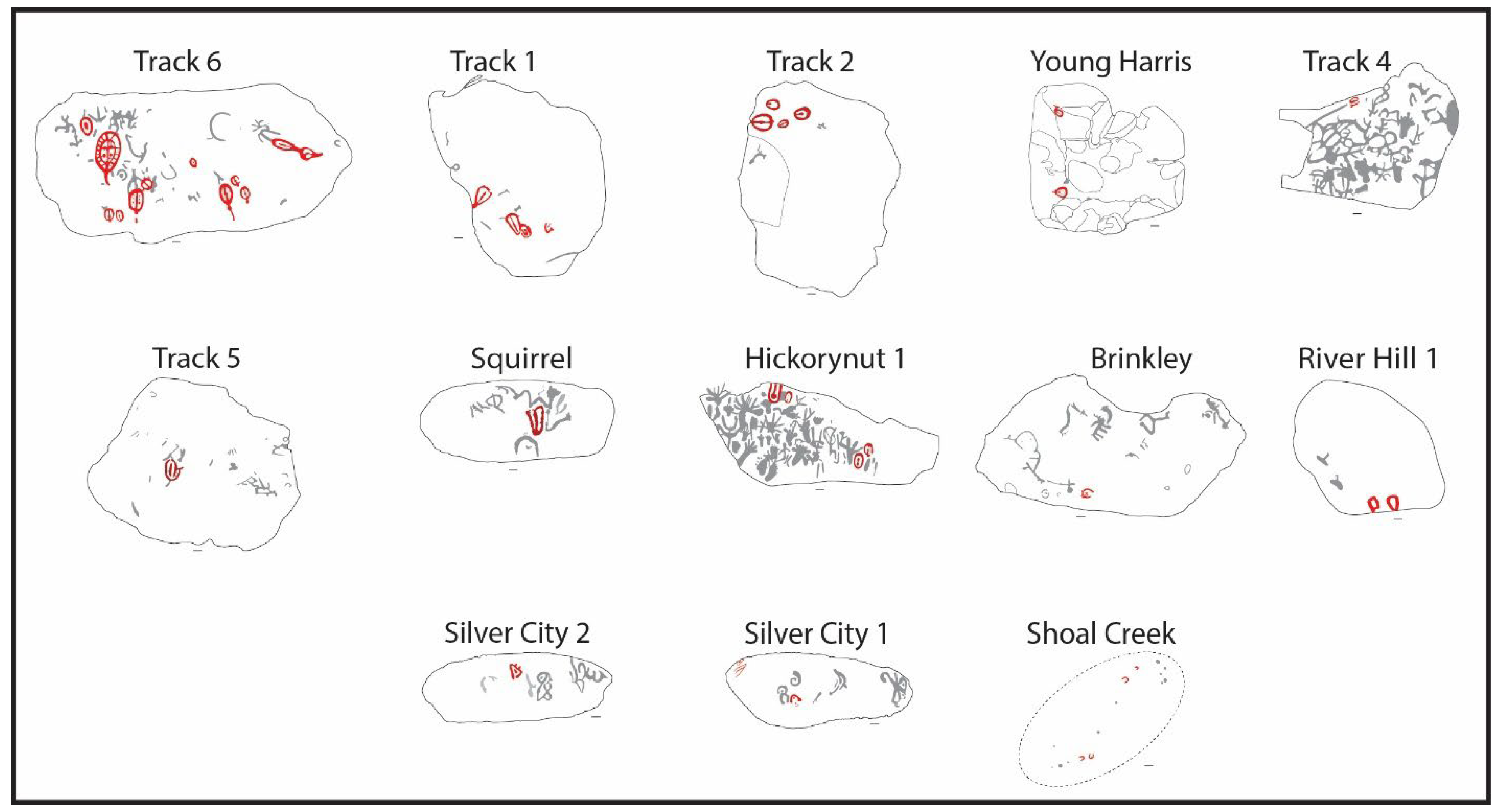

4.9. Tracks

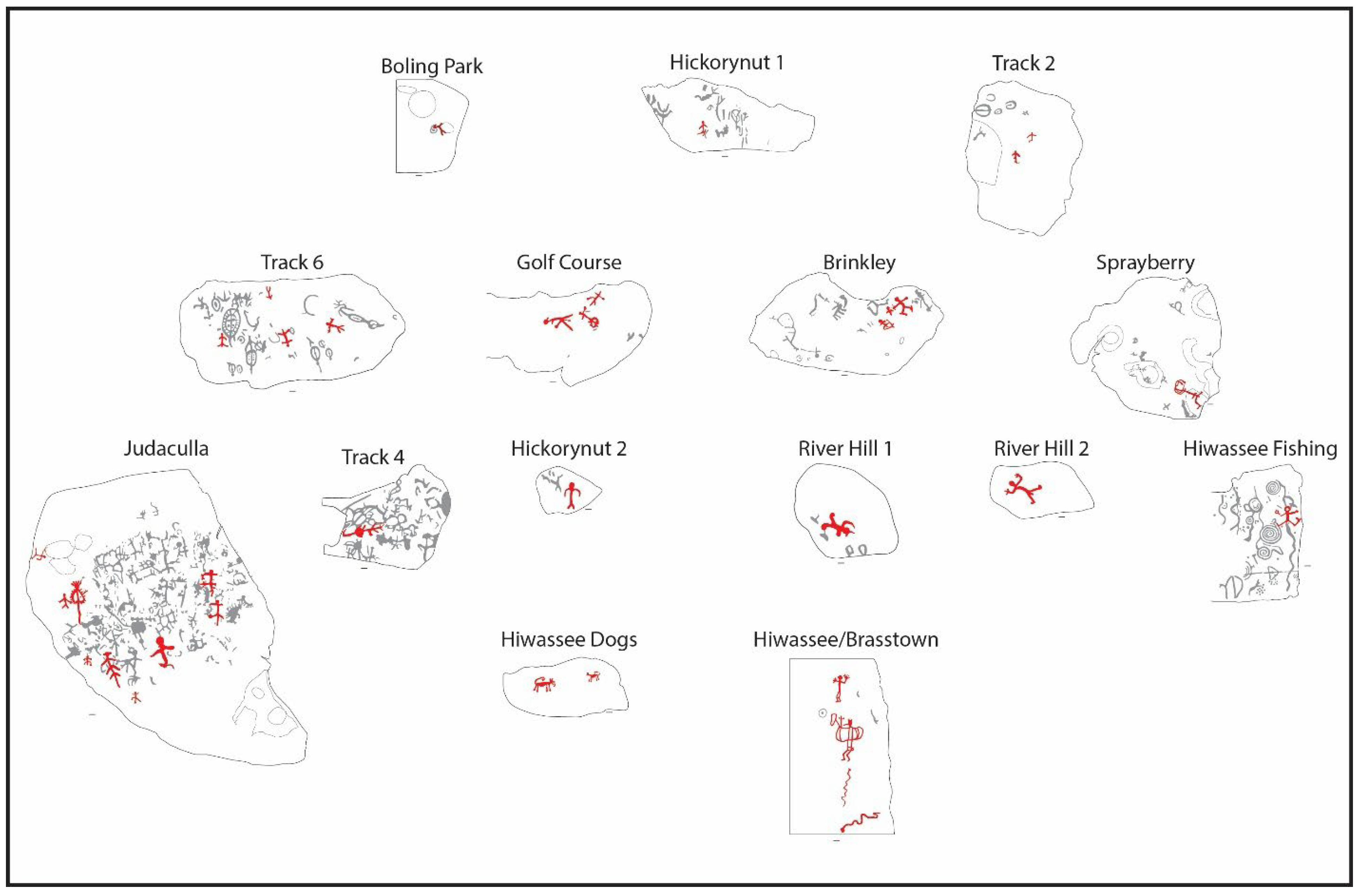

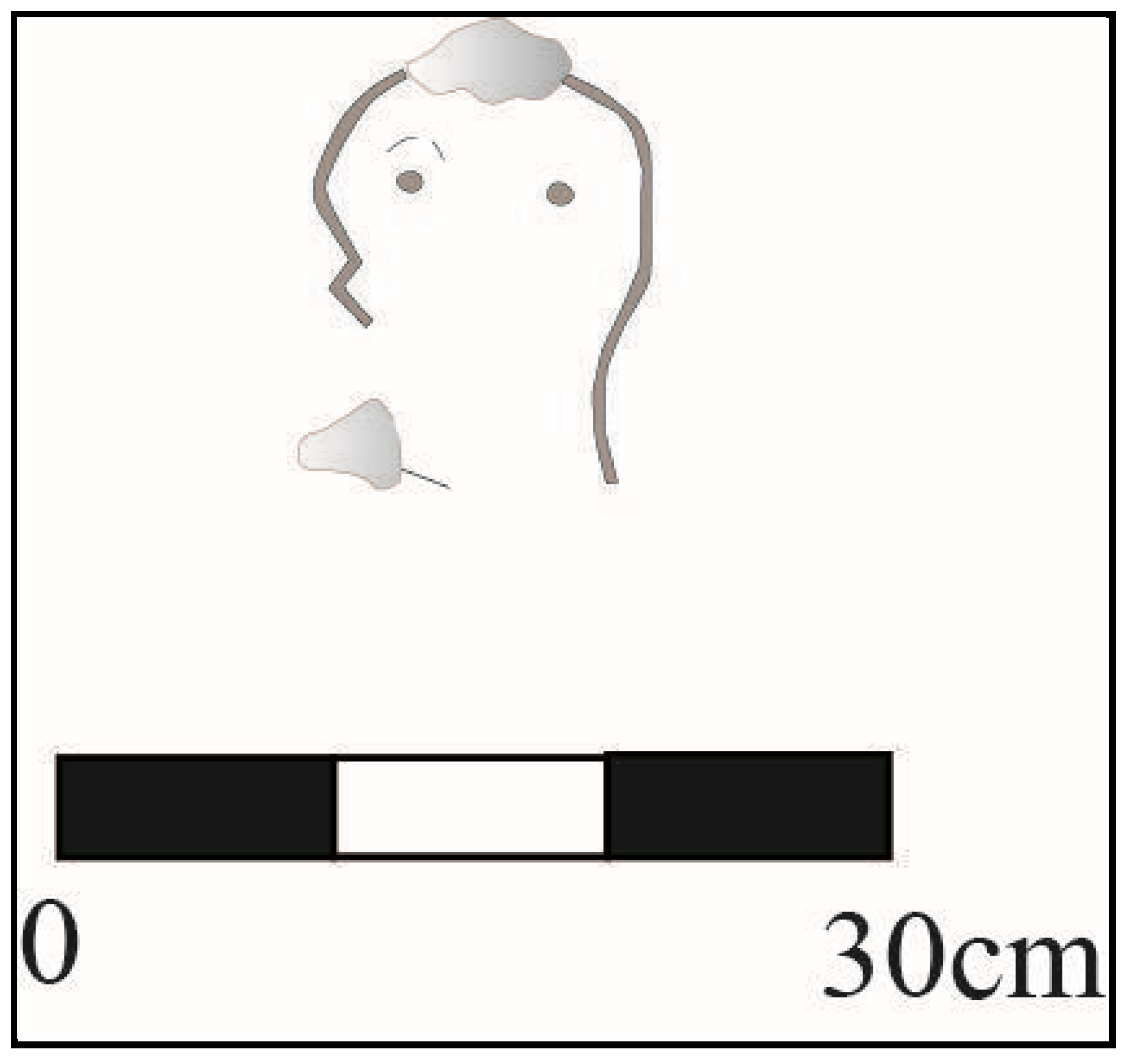

4.10. Figures

4.11. Concentric Circles

4.12. Cross-in-Circles

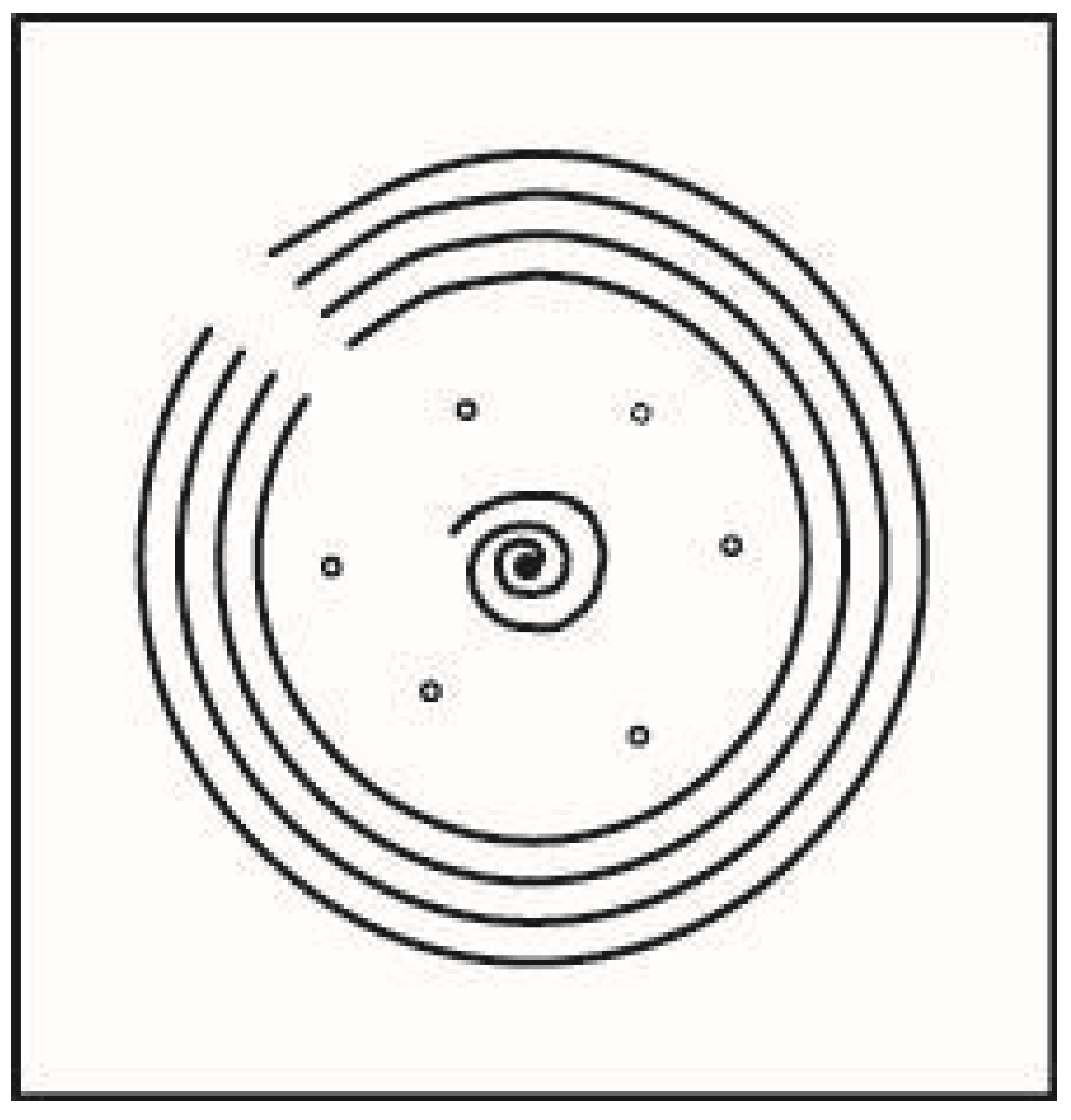

4.13. Spirals

4.14. Straight Lines

4.15. Composite Motif

4.16. Fine Line Incisions

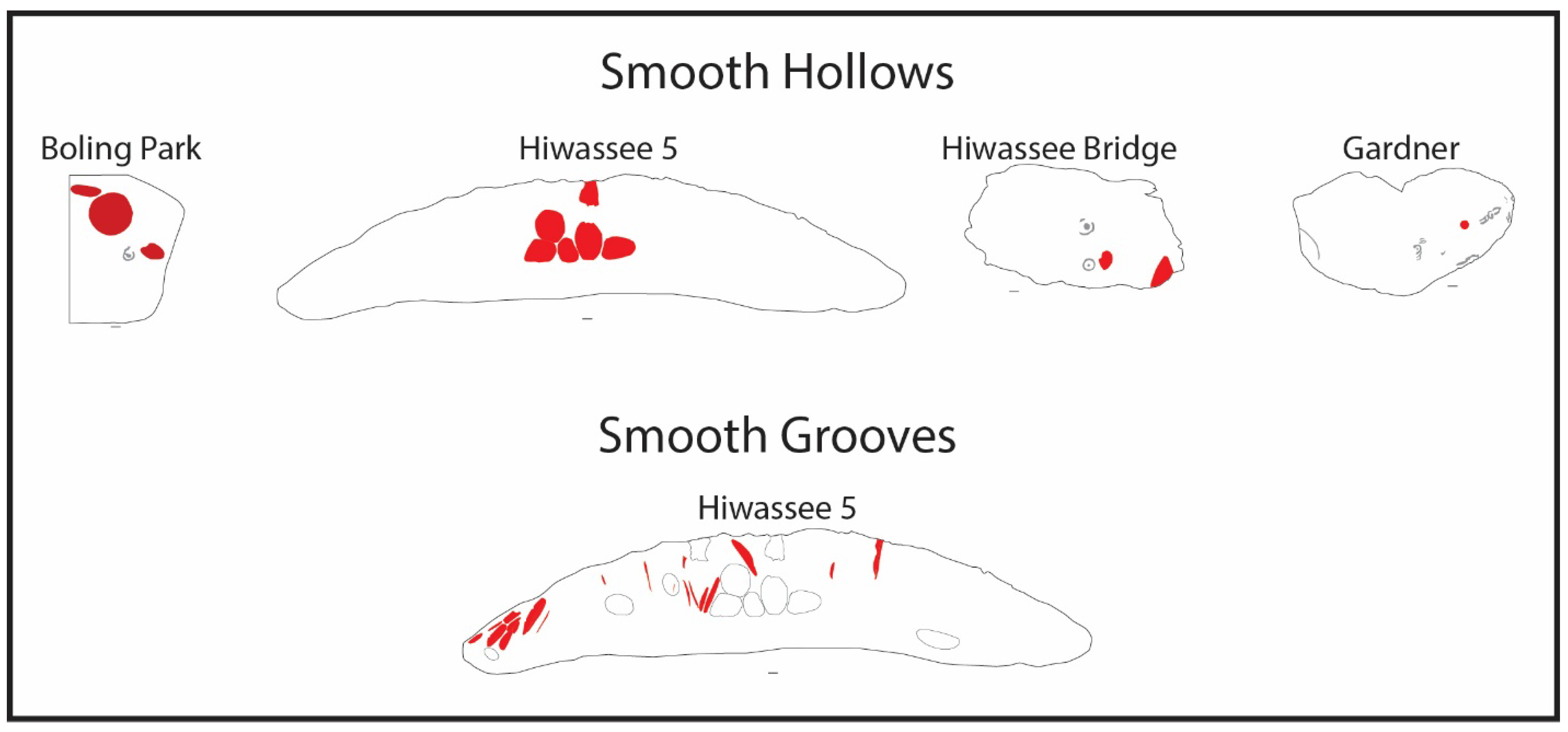

4.17. Smooth Hollows and Grooves

4.18. Summary of Motif Categories and Sequence

5. Formal Thesis: Water as a Medium to Penetrate Rock

6. Informed Antithesis: Water as a Medium to Breach the Divide Between Physical and Spiritual Realms

7. Informed Antithesis: Cherokee and Creek Beliefs and Practices

7.1. Animistic Beliefs as Informed by Altered State Experiences

7.2. Hierarchy of Ritual Practitioners Among Southeastern Native Americans

7.3. Townhouses and Rivers as Central Ritual Locales

7.4. Rituals as Re-Enactments of “Mythical” Events

7.5. Rivers as Sentient Beings

7.6. A Hierarchical Universe of Self-Similar Beings

7.7. Summary of Cherokee and Creek Beliefs and Rituals

- Self-similar relationships exist at macro and microcosmic scales, most noticeably, the mirrored behavior of Sun and Moon, Selu and Kanati, Judaculla and his Wife, and Little People and everyday physical people.

- Reciprocal exchange relationships exist between the physical and spiritual realms, expressed as “restoring the balance,” manifest in various ways, such as through Uktena, lightning, and ritual practitioners traveling back and forth between the physical and spiritual realms, or hunters leaving “offerings” of deer meat to spirit beings.

- Thundering sounds of various kinds and intensities are associated with virtually all spirit beings. They are experienced by both ritual practitioners and ordinary people who are stressed or in contact with these entities.

- Spirit beings, or ritual specialist representatives, create impressions on rocks, including lines created by Wild Boy playing chunky, tracks left by animals and birds escaping from the Kanati’s townhouse, dueling Uktenas and lightning bolt snakes carving rocks, menstrual blood impressions left by Judaculla’s wife, Judaculla’s finger drawn lines and handprints in Judaculla Rock, and the footprints left by Judaculla’s children.

- Shamans and other ritual practitioners who assumed the identity of spirit beings, such as Uktena, or individuals who became part of Judaculla’s extended family, are the ones who created the petroglyphs.

- By entering water, priests, shamans, and individuals seeking favors from spirit beings can transcend physical and mental barriers between the physical and spiritual realms, such as those represented by rocks.

- Fire, the antithesis of water, is also a gateway that allows for movement between realms.

- Locales that are widely separated from other locales on the ground, in the sky, or below the ground can share physical and metaphorical attributes.

- The movements between vastly separated locales, both horizontally and vertically, are informed by out-of-body sensations experienced by ritual specialists during dreams, visions, and near-death experiences.

- The socio-cultural acceptance of altered states of consciousness as part of reality among southeastern Native Americans nurtures the impression that rocks, plants, animals, and specific artifacts and features are sentient beings.

8. Informed Antithesis: Significance of the Petroglyphs in Terms of Cherokee and Creek Beliefs and Practices

Tenacious Native American Beliefs as an Information Filter

9. Informed Antithesis: The Multiple Meanings of and Various Interactions with the Petroglyph Motifs and Rocks

9.1. Introduction

9.2. Meanders

9.3. Cupules

9.4. Soapstone Bowl Extraction Scars

9.5. Vulva Shapes

9.6. Tracks

9.7. Figures

9.8. Concentric Circles

9.9. Cross-in-Circles

9.10. Spirals

9.11. Two Unique Dogs and a Spiral

9.12. Straight Lines

9.13. Fine Line Incisions

9.14. Smooth Hollows and Grooves

9.15. Continued Interaction with the Petroglyph Surfaces

9.16. Summary of the Significance of Petroglyphs and the Places Where They Occur

10. Synthesis of Formal and Informed Information: The Landscape Setting of the Petroglyphs

10.1. Introduction

10.2. The Brasstown Creek Corridor

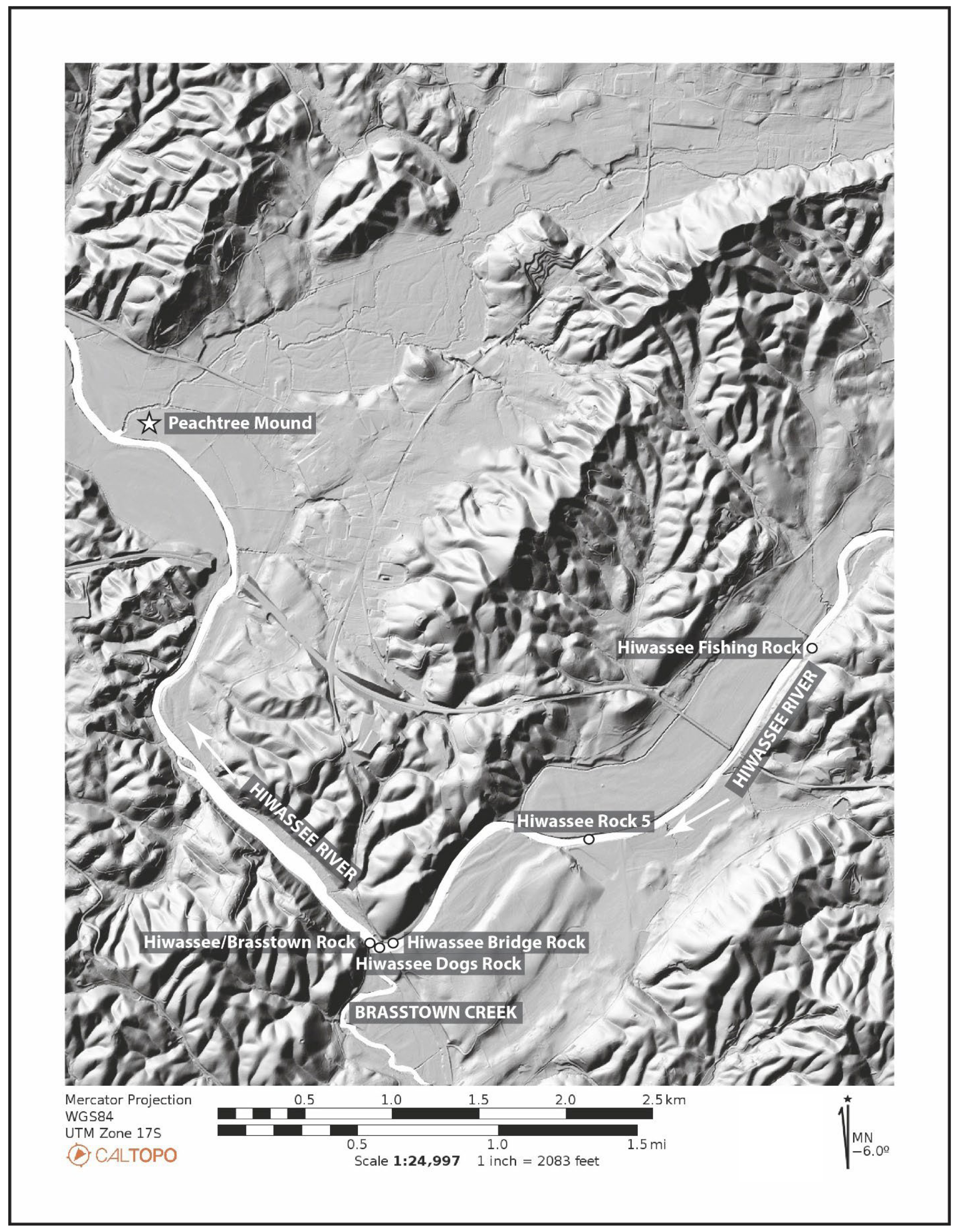

10.3. The Hiwassee River Corridor

10.4. Caney Creek and Pigeon River Corridors

10.5. The Soucee Creek Corridor

10.6. The Little Tennessee River Corridor

10.7. The Cane River Corridor

10.8. The Chickamauga Creek Corridor

10.9. The Etowah River Corridor

10.10. Summary of the River Corridors

- The first transformation involves prolonged dancing and fasting within a townhouse, with a sacred central fire at the focus, accompanied by repetitive circular movements. The overnight physical exhaustion of a supplicant is intended to enhance awareness of spirit beings, such as the two sisters who visit the young warrior in Săkwi’yi Town’s townhouse.

- The second transformation involves early morning purification in a nearby river, sometimes preceding by scratching the arms with sharp animal bones or teeth (this is also part of the Green Corn and Busk rituals that are common throughout the southeastern United States). A purified supplicant faces the rising sun and then proceeds on the journey to the townhouse of spirit beings, following a riparian trail, at times walking or canoeing (the latter if heading downstream, such as along the Hiwassee and Little Tennessee Rivers).

- The third transformation is a “rest” stop at a petroglyph site, where certain rituals are conducted and sacred formulas are recited. Failure to comply with proper ritual requirements is likely to result in bad encounters with spirit beings once a spirit townhouse is reached, such as Judaculla pursuing disrespectful hunters.

- The fourth transformation of entering the townhouse of spirit beings is a dangerous one and seems to be reserved only for a select few ritual practitioners, notably, shamans and perhaps priests (the latter before the populace ousted them). This transformation involves entering a trance-like state and communicating with spirit beings, who are, for the most part, not audible or visible in the everyday physical world. Ordinary people can join these journeys. Still, like Judaculla’s brother-in-law, they must be content to stay outside the townhouses of powerful spirit beings or risk terrifying encounters that can result in death.

11. Synthesis of Archaeological and Ethnographic Information: The Regional Setting of the Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | At first, Mooney (1900) uses the term “Thunderers,” but later in his book, he changes it to the “Thunders.” Although the reason for this change is unclear, this paper retains the different terms for the seemingly same extended family of spirit beings as they initially appear in the quoted printed pages. |

References

- Adair, James. 1930. Adair’s History of the American Indians. Edited by Samuel C. Williams. New York: Promontory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft, Scott. 2014. Cultural Resources Survey for the Proposed Courthouse Creek Project. National Forest Report Submitted to the National Forests in North Carolina. Asheville: National Forests in North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, William. 1955. Travels of William Bartram. Edited by Mark Van Doren. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, Lowell J. 1976. Power and Its Applications in Native California. In Native Californians: A Theoretical Retrospective. Edited by Lowell John Bean and Thokas C. Blackburn. Ramona: Ballena Press, pp. 407–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Lee. 2018. Sweetgum’s Amber: Animate Mound Landscapes and the Nonlinear Longue Durée in the Native South. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, John S., and Hall S. Gard. 2000. Research Design and Field Results of Archaeological Excavations in Brasstown Valley. Early Georgia 28: 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, Kevin L. 2004. Pica, Geogaphy, and Rock-Art in the Eastern United States. In The Rock-Art of Eastern North America, Capturing Images and Insights. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados and James R. Duncan. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Alex K. 2007. Place, Performance, and Social Memory in the 1890s Ghost Dance. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne, Duane. 1990. Institutional and Cultural Order in Early Cherokee Society: A Sociological Interpretation. The Journal of Cherokee Studies 15: 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Tommy. 2010. Discovering South Carolina’s Rock Art. Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, Jean, and Joyotpaul Chaudhuri. 2001. A Sacred Path: The Way of the Muskogee Creeks. Los Angeles: UCLA American Indian Studies Center. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, Frances. 1943. A Search for Songs Among Chitimacha Indians in Louisiana. Anthropological Papers 19, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnography Bulletin. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, vol. 133, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, James O., and John R. Swanton. 1912. A Dictionary of the Biloxi and Ofo Languages. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 47. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnell, Robert C. 1971. Systematics in Prehistory. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Dan T. 1986. The Live Oak Soapstone Quarry, DeKalb County, Georgia. Atlanta: Garrow and Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, Charles H., Jan F. Simek, and Alan Cressler. 2004. On the Edges of the World: Prehistoric Open-Air Rock-Art in Tennessee. In The Rock-Art of Eastern North America: Capturing Images and Insight. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados and James R. Duncan. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelson, Ray D. 1980. The Conjurer in Eastern Cherokee Society. Journal of Cherokee Studies 5: 60–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelson, Ray D. 1982. Cherokee Little People Reconsidered. Journal of Cherokee Studies 7: 92–8. [Google Scholar]

- Garden State Soapstone. 2016. Soapstone and the Mohs Scale. Available online: https://www.gardenstatesoapstone.com/blog/2016/06/soapstone-and-the-mohs-scale/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Garrett, J. T., and Michael T. Garrett. 1996. Medicine of the Cherokee: The Way of Right Relationship. Rochester: Bear and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham, Bill. 2002. Creation Myths and Legends of the Creek Indians. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Lorie. 2009. Rock Art in North Carolina. Asheville: North Carolina Rock Art Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Edward C., Marley R. Brown III, and Gregory J. Brown. 1993. Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Tom. 1993. The Dividing Paths: Cherokees and South Carolinians Through the Revolutionary Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hays-Gilpin, Kelley. 2004. Ambiguous Images: Gender and Rock Art. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, John. 1823. The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, up to the First Settlements Therein by the White People, in the Year 1768. Nashville: George Wilson. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, Janey B. 1983. Redbird Smith and the Nighthawk Keetoowahs. Journal of Cherokee Studies 8: 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, Bart, and John Martz. 1979. Alabama’s Aboriginal Rock Art. Montgomery: Alabama Historical Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, John N. B. 1939. Notes on the Creek Indians. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Anthropological Papers No. 10. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, John. 1826. Traditions and History of the Cherokee Indians to 1776. Letters in the Handwriting of John H. Payne to John Ross. In the Ayer Collection. Chicago: Newberry Library. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Eric, and Brett Riggs. 1993. Digital Library of Georgia. Knoxville: Frank H. McClung Museum, The University of Tennessee. Available online: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_zlna_mm081?canvas=0&x=369&y=435&w=1674 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Hudson, Charles. 1997. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, Thomas N. 1980. Ceramics, Classification, and Iron Age Entities. African Studies 39: 123–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Charles C. 1873. Antiquities of the Southern Indians, Particularly of the Georgia Tribes. New York: D. Appleton and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, Scot J. 2010. Archaeological Data Recovery at the Leake Site, Bartow County, Georgia. Southern Research Report Submitted to the Georgia Department of Transportation. Atlanta: Georgia Department of Transportation. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, Jack F., and Anna G. Kilpatrick. 1967. Run Toward the Nightland: Magic of the Oklahoma Cherokees. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Laura H. 1977. The Cherokee Story-Teller: The Raven Mocker. Journal of Cherokee Studies 2: 190–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, Deborah L. 2013. Visualizing the Cherokee Homeland Through Indigenous Historical GIS: An Interactive Map of James Mooney’s Ethnographic Fieldwork and Cherokee Collective Memory. Master’s thesis, Department of Geography, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, Jim B. 2002. Nacoochee Mound. The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/nacoochee-mound/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Lanham, Charles. 1849. Letters from the Alleghany Mountains. New York: Geo. P. Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter, R. Jerald, K. B. Burns, Thomas G. Gresham, Scott Jones, David S. Leigh, William G. Moffat, and Lisa D. O’Steen. 2006. Archaeological and Historical Investigations of the Georgia Pacific and Hardin Tracts, Greene County, Georgia (with Addendum). Southeastern Archaeological Services Report Submitted to Reynolds Plantation. Greensboro: Reynolds Plantation. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, David, and Ann T. Jordan. 2002. Creek Indian Medicine Ways: The Enduring Power of Mvskoke Religion. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1992. Vision, Power and Dance: The Genesis of a Southern African Rock Art Panel. Fourteenth Kroon Lecture. Amsterdam: Stichting Nederlands Museum voor Anthropologie en Praehistorie. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1997. Harnessing the Brain: Vision and Shamanism in the Upper Paleolithic Western Europe. In Beyond Art: Pleistocene Image and Symbol. Edited by M. W. Conkey, O. Soffer, D. Stratmann and N. G. Jablonski. San Francisco: Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, Number 23. pp. 321–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and David G. Pearce. 2004. San Spirituality: Roots, Expression, and Social Consequences. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and David G. Pearce. 2005. Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos, and the Realm of the Gods. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and Johannes H. N. Loubser. 2014. Bridging Realms: Towards Ethnographically Informed Methods to Identify Religious and Artistic Practices in Different Settings. Time and Mind 7: 109–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and Thomas A. Dowson. 1988. The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art. Current Anthropology 29: 210–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 1997. The Use of Harris diagrams in recording, Conserving, and Interpreting Rock Paintings. International Newsletter on Rock Art 18: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 2005. In Small Cupules Forgotten: Rock Markings, Archaeology, and Ethnography in the Deep South. In Discovering North American Rock Art. Edited by Lawrence L. Loendorf, Christopher Chippendale and David S. Whitley. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp. 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 2009. From Boulder to Mountain and Back Again: Self-Similarity between Landscape and Mindscape in Cherokee Thought, Speech, and Action as expressed by the Judaculla Rock Petroglyphs. Time and Mind 2: 287–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 2010. The Recording and Interpretation of Two Petroglyph Locales, Track Rock Gap and Hickorynut Mountain, Blue Ridge and Chattooga River Ranger Districts, Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forests, Union and White Counties, Georgia. Statum Report Submitted to the USDA Forest Service. Gainesville: USDA Forest Service. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 2011. Heritage Resources Evaluation of the Allen Petroglyph Boulder, 9HM299, Habersham County, Chattooga Ranger District, Georgia. Stratum Report Submitted to the USDA Forest Service. Gainesville: Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N. 2024. LCAI Round 13—Graffiti Mitigation and Rock Art Recording at Site 26LN211 PO# 140L3923P0002. Stratum Report Submitted to BLM-NV Caliente Field Office. Caliente: BLM-NV Caliente Field Office. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N., and Douglas Frink. 2007. Heritage Resource Conservation Plan for Judaculla Rock, State Archaeological Site 31JK3, Jackson County, North Carolina. Statum Report Submitted to Jackson County. Sylva: Jackson County. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N., and Douglas Frink. 2010. An Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Appraisal of a Piled Stone Feature Complex in the Mountains of North Georgia. Early Georgia 38: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N., and Scott Ashcraft. 2019. Gates between Worlds: Ethnographically Informed Management and Conservation of Petroglyph Boulders in the Blue Ridge Mountains. In Mind, Ethnography, and the Past in South Africa and Beyond. Edited by David S. Whitley, Johannes Loubser and Gavin Whitelaw. New York: Routledge, pp. 247–69. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N., Scott Ashcraft, and James Wettstaed. 2018. Betwixt and Between: The Occurrence of Petroglyphs between Townhouses of the Living and Townhouses of Spirit Beings in Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina. In Transforming the Landscape: Rock Art and the Mississippian Cosmos. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados, Jan Simek, George Sabo III and Mark Wagner. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 200–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, William, and Laura Kozuch. 2015. The Practical and Spiritual Significance of the Lightning Whelk. Paper presented at the 80th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, San Francisco, CA, USA, April 16. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, C. Hart. 1955. Studies of California Indians. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Wick R. 1983. Numic Languages. In Great Basin, Handbook of North American Indians. Edited by Warren L. D’Azevedo. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, Volume 11, pp. 9–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, James. 1891. The Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees. In Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1885–1886. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, James. 1900. Myths of the Cherokee. In Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1897–1898. Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, James. 1982a. Cherokee Theory and Practice of Medicine. The Journal of Cherokee Studies 17: 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, James. 1982b. The Cherokee Ball Play. The Journal of Cherokee Studies 17: 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, James. 1982c. The Cherokee River Cult. The Journal of Cherokee Studies 17: 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, John H. 1994. Ethnoarchaeology of the Lamar People. In Perspectives on the Southeast: Linguistics, Archaeology, and Ethnohistory. Edited by Patricia B. Kwachka. Athens: University of Georgia Press, pp. 126–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, Edward. 1733. A New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina (Moseley Map). MC0017. East Carolina University Digital Collections. Available online: https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/62315 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Murie, Olaus J., and Mark Elbroch. 2005. The Field Guide to Animal Tracks. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Nabokov, Peter. 1982. Two Leggings: The Making of a Crow Warrior. Lincoln: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Museum of History. 2011. Health and Healing in North Carolina: An Interactive Timeline. Available online: http://ncmuseumofhistory.org/exhibits/healthandhealing/topic/9 (accessed on 2 August 2013).

- Orton, Clive. 1982. Mathematics in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parkman, E. Breck. 1995. California Dreamin’: Cupule Petroglyph Occurrences in the American West. In Rock Art Studies in the Americas: Papers from the Darwin Rock Art Congress. Edited by Jack Steinbring. Oxford: Oxford Monograph, No. 45, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, John. 1950a. Mythical Jutaculla—The Paul Bunyan of His Race. Durham Evening Herald, May 29. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, John. 1950b. The Cherokee Story. Asheville: The Stephens Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pauketat, Timothy R., and Thomas E. Emerson. 1991. The Ideology of Authority and the Power of the Pot. American Anthropologist 93: 919–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, Margaret. 1968. Sculptured Monoliths of Georgia, Part 2. Tennessee Archaeologist 24: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rajnovich, Grace. 1994. Reading Rock Art: Interpreting the Indian Rock Paintings of the Canadian Shield. Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1978a. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1978b. Drug-induced Optical Sensations and their Relationship to Applied Art Among some Colombian Indians. In Art in Society. Edited by Michael Greenhalgh and Vincent Megaw. London: Duckworth, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ripinsky-Naxon, Michael. 1993. The Nature of Shamanism: Substance and Function of a Religious Metaphor. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, William S. 1951. A Method for Chronologically Ordering Archaeological Deposits. American Antiquity 16: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodning, Christopher B. 2008. Temporal Variation in Qualla Pottery at Coweeta Creek. North Carolina Archaeology 57: 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rodning, Christopher B. 2012. Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Shell Gorgets from Southwestern North Carolina. Southeastern Archaeology 31: 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, Peter G. 1991. Cross-Media Isomorphism in Taíno Ceramics and Petroglyphs from Puerto Rico. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Congress of the International Association for Caribbean Archaeology. Barbados: IACA, Volume 14, pp. 637–71. [Google Scholar]

- Royce, Charles C. 1887. Old Cherokee Towns from the Cherokee Nation of Indians. In Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1883–1884. Nashville: Tennessee Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Rozwadowski, Andrzej, and Janusz Z. Woloszyn. 2024. Dances with Zigzags in Toro Muerto, Peru: Geometric Petroglyphs as (Possible) Embodiments of Songs. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 34: 671–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassaman, Kenneth E. 2006. Dating and Explaining Soapstone Vessels: A Comment on Truncer. American Antiquity 71: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroedl, Gerald F. 1998. Mississippian Towns in the Eastern Tennessee Valley. In Mississippian Towns and Sacred Spaces: Searching for Architectural Grammar. Edited by R. Barry Lewis and Charles Stout. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, Ashley. 2017. The Pisgah View from the Appalachian Summit: Recent Findings from the Cane River Site (31YC91), Yancey County, North Carolina. Paper Presented at the Cherokee Archaeological Symposium, Cherokee, NC, USA, September 7. [Google Scholar]

- Setzler, Frank M., and Jesse D. Jennings. 1941. Peachtree Mound and Village Site, Cherokee County, North Carolina. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 131. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Simek, Jan F., Alan Cressler, and Bart B. Henson. 2018. Prehistoric Rock Art, Social Boundaries, and Cultural Landscapes on the Cumberland Plateau of Southeastern North America. In Transforming the Landscape: Rock Art and the Mississippian Cosmos. Edited by Carol Diaz-Granados, Jan Simek, George Sabo, III and Mark Wagner. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 156–97. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Benjamin W., and Geoffrey Blundell. 2004. Dangerous Ground: A Critique of Landscape in Rock-Art Studies. In Pictures in Place: The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art. Edited by Christopher Chippindale and George Nash. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 239–62. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Marvin T., and Julie B. Smith. 1989. Engraved Shell Masks in North America. Southeastern Archaeology 8: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Steere, Benjamin A. 2015. Revisiting Platform Mounds and Townhouses in the Cherokee Heartland: A Collaborative Approach. Southeastern Archaeology 34: 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, Matthew F. 1871. Geology and Mineralogy of Georgia. Atlanta: Globe Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Kathleen A. Van Vlack, Alannah Bell, and Bianca E. Uribe. 2024. Storied Rocks: Portals to Other Dimensions. Arts 13: 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Kathleen A. Van Vlack, and Heather Lim. 2025. Celestial Light Marker: An Engineered Calendar in a Topographically Spectacular Geoscape. Arts 14: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Kathleen A. Van Vlack, Hannah Z. Johnson, Philip T. Dukes, Stephanie C. De Sola, and Kristen L. Simmons. 2011. Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Delamar Valley Solar Energy Zone. Report Prepared by Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology. Tucson: School of Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Maria Nieves Zedeño, Jaime K. Eyrich, and Patrick Barabe. 2000. The Wellington Canyon Ethnographic Study at Pintwater Range, Nevada. Report Submitted by the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona in Tucson to US Air Force, Nellis Air Force Base and Range Complex, Native American Interaction Program, and Science Applications International Corporation. Las Vegas: US Air Force. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Rebecca S. Toupal, and Maria Nieves Zedeño. 2002. East of Nellis, Cultural Landscapes of the Sheep and Pahranagat Mountain Ranges: An Ethnographic Assessment of American Indian Places and Resources in the Desert National Wildlife Range and the Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuge of Nevada. Report Submitted by the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona in Tucson to US Air Force, Nellis Air Force Base and Range Complex, Native American Interaction Program, and Science Applications International Corporation. Las Vegas: US Air Force. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, William C. 1978. Louis-Philippe on Cherokee Architecture and Clothing in 1797. Journal of Cherokee Studies 3: 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom, Lea. 1996. Mirrors of Heaven: Cross-Cultural Transference of the Sacred Geography of the Black Hills. World Archaeology 28: 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, Lea. 2002. Steel Awls for Stone Age Plainswomen: Rock Art, Religion, and the Hide Trade on the Northern Plains. Plains Anthropologist 47: 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanton, John R. 1928. Social Organization and Social Usages of the Indians of the Creek Confederacy. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, vol. 42, pp. 23–472. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton, John R. 1987. The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton, John R. 2000. Creek Religion and Medicine. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taçon, Paul S. C., and Christopher Chippindale. 1998. An Archaeology of Rock-Art Through Informed Methods and Formal Methods. In The Archaeology of Rock-Art. Edited by Christopher Chippindale and Paul S. Taçon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- The Franklin Press and Highlands Maconian. 1961. On Angel Farm—Indians Come Here to Study Markings, vol. 20, p. 1.

- The Reinhardt Alumni Powwow. 1948. Prehistoric Indian “Monument” Given College by Mrs. Cline, vol. 3, p. 5.

- Thompson, Victor D., Jacob Holland-Lulewicz, RaeLynn Butler, Turner W. Hunt, LeAnn Wendt, James Wettstaed, Mark Williams, Richard Jefferies, and Susan K. Fish. 2022. The Early Materialization of Democratic Institutions among the Ancestral Muskogean of the American Southeast. American Antiquity 87: 704–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, John. 1832. District Plats of Survey, Survey Records, Surveyor General, RG 3-3-24. Atlanta: Georgia Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Tylor, Edward B. 1871. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schalkwyk, Johnny. 2020. A Cognitive Approach to the Ordering of the World: Some Case Studies from the Sotho- and Tswana-Speaking People of South Africa. In Mind, Ethnography, and the Past in South Africa and Beyond. Edited by David S. Whitley, Johannes Loubser and Gavin Whitelaw. New York: Routledge, pp. 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Trawick H., and R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. 1998. Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waselkov, Gregory A., and Kathryn E. Holland Braund. 1995. William Bartram and the Southeastern Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Vanessa. 2013. Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency amongst Humans and Non-Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go on a European World Tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2: 2034. [Google Scholar]

- Wauchope, Robert. 1966. An Archaeological Survey of Northern Georgia, With a Test of Some Cultural Hypotheses. Washington, DC: Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Edward W. 2006. Soapstone Vessel Chronology and Function in the Southern Appalachians of Eastern Tennessee. Master’s thesis, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wetmore, Ruth Y. 1983. The Green Corn Ceremony of the Eastern Cherokees. Journal of Cherokee Studies 8: 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- White, George. 1854. Historical Collections of Georgia. New York: Pudney and Russell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 1994. Shamanism, Natural Modeling and the Rock Art of Far Western North America. In Shamanism and Rock Art in North America. Edited by Solveig Turpin. San Antonio: Rock Art Foundation, Inc., Special Publication 1. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2005. Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, Thomas G., and Lacey M. Hicks. 2003. A Geographic Information Systems Approach to Understanding Potential Prehistoric and Historic Travel Corridors. Southeastern Archaeology 22: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, T. 1974. Frank H. McClung Museum, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Presented in the Digital Library of Georgia. Available online: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_zlna_mm024?canvas=0&x=400&y=400&w=1506 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wilburn, Hiram C. 1952a. Judaculla Place Names and the Judaculla Tales. Southern Indian Studies IV: 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilburn, Hiram C. 1952b. Judaculla Rock. Southern Indian Studies IV: 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Lovett E. 1981. The Book of the Wild Turkey. Tulsa: Winchester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Mark. 1999. Archaeological Testing at the Kenimer Site, 9WH68. Athens: LAMAR Institute Publications, No. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Mark, and Gary Shapiro. 1990. Introduction. In Lamar Archaeology: Mississippian Chiefdoms in the Deep South. Edited by Mark Williams and Gary Shapiro. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Walter L. 1979. Southeastern Indians: Since the Removal Era. Athens: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Witelson, David M. 2023. Theaters of Imagery: A Performance Theory Approach to Rock Art Research. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Witthoft, John. 1983. Cherokee Beliefs Concerning Death. Journal of Cherokee Studies 8: 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, Jack T. 1990. Mississippi Period Archaeology of the Georgia Blue Ridge Mountains. Athens: University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology, Report Number 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zedeño, M. Nieves. 2000. The Archaeology of Territory and Territoriality. In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology. Edited by Bruno David and Julian Thomas. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, pp. 210–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, Wilbur G., and Ben S. Grosscup. 1883. The Heart of the Alleghanies, or Western Carolina. Raleigh: Alfred Williams. [Google Scholar]

| Reinhardt | Brinkley | River Hill 1 | Track 4 | Silver 2 | Hickory 1 | Silver 1 | Track 2 | Sprayberry | Gardner | Judaculla | Track 5 | Track 6 | Boling | Track 3 | Chatuge | Young Harris | Squirrel | Golf | Hiwassee Fishing | Hiwassee Bridge | Allen | Hickory 2 | Track 1 | Hiwassee Brasst | Hiwassee 5 | Turkey Track A | Turkey Track B | Track 7 | Hiwassee Dogs | Quarry | River Hill 2 | River Hill 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinhardt | 67 | 73 | 55 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 83 | 91 | 67 | 77 | 67 | 67 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 67 | 73 | 67 | 55 | 50 | 50 | 67 | 50 | 67 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 57 | 25 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Brinkley | 67 | 92 | 92 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 86 | 77 | 73 | 80 | 73 | 86 | 73 | 55 | 55 | 73 | 77 | 73 | 77 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 60 | 55 | 60 | 40 | 40 | 44 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| River Hill 1 | 73 | 92 | 83 | 73 | 91 | 91 | 92 | 83 | 60 | 71 | 80 | 77 | 80 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 67 | 60 | 67 | 44 | 44 | 60 | 67 | 60 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 50 | 22 | 29 | 29 | 29 | |

| Track 4 | 55 | 92 | 83 | 73 | 91 | 73 | 77 | 67 | 80 | 71 | 80 | 92 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 83 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 60 | 67 | 60 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 25 | 22 | 29 | 29 | 0 | |

| Silver 2 | 80 | 83 | 73 | 73 | 60 | 80 | 67 | 73 | 89 | 77 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 67 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 44 | 50 | 44 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 57 | 25 | 33 | 0 | 33 | |

| Hickory 1 | 80 | 83 | 91 | 91 | 60 | 80 | 83 | 73 | 67 | 62 | 89 | 83 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 89 | 73 | 67 | 55 | 50 | 50 | 67 | 75 | 67 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 29 | 25 | 33 | 33 | 0 | |

| Silver 1 | 80 | 83 | 91 | 73 | 80 | 80 | 83 | 73 | 67 | 62 | 89 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 89 | 73 | 44 | 55 | 50 | 50 | 44 | 75 | 44 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 57 | 25 | 33 | 0 | 33 | |

| Track 2 | 83 | 86 | 92 | 77 | 67 | 83 | 83 | 92 | 55 | 80 | 73 | 86 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 77 | 55 | 62 | 40 | 40 | 55 | 60 | 55 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 44 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Sprayberry | 91 | 77 | 83 | 67 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 92 | 60 | 86 | 60 | 77 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 60 | 67 | 60 | 67 | 44 | 44 | 60 | 44 | 60 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 50 | 22 | 29 | 29 | 29 | |

| Gardner | 67 | 73 | 60 | 80 | 89 | 67 | 67 | 55 | 60 | 67 | 75 | 73 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 50 | 80 | 75 | 60 | 86 | 86 | 50 | 57 | 50 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Judaculla | 77 | 80 | 71 | 71 | 77 | 62 | 62 | 80 | 86 | 67 | 50 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 50 | 71 | 67 | 71 | 55 | 55 | 67 | 36 | 50 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 40 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 22 | |

| Track 5 | 67 | 73 | 80 | 80 | 67 | 89 | 89 | 73 | 60 | 75 | 50 | 73 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 57 | 57 | 50 | 57 | 50 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Track 6 | 67 | 86 | 77 | 92 | 67 | 83 | 67 | 86 | 77 | 73 | 80 | 73 | 55 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 77 | 73 | 62 | 60 | 60 | 55 | 60 | 55 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 0 | |

| Boling | 89 | 73 | 80 | 60 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 80 | 50 | 67 | 50 | 55 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 75 | 80 | 57 | 57 | 75 | 57 | 75 | 57 | 29 | 29 | 67 | 29 | 0 | 40 | 40 | |

| Track 3 | 89 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 80 | 75 | 67 | 75 | 73 | 50 | 100 | 75 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 57 | 57 | 50 | 57 | 50 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chatuge | 89 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 80 | 75 | 67 | 75 | 73 | 50 | 100 | 75 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 57 | 57 | 50 | 57 | 50 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Young Harris | 67 | 73 | 80 | 80 | 67 | 89 | 89 | 73 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 73 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 57 | 57 | 50 | 86 | 50 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Squirrel | 73 | 77 | 67 | 83 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 77 | 67 | 80 | 71 | 80 | 77 | 40 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 60 | 50 | 67 | 67 | 40 | 67 | 40 | 44 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Golf | 67 | 73 | 60 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 44 | 55 | 60 | 75 | 67 | 50 | 73 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 80 | 86 | 86 | 75 | 57 | 75 | 57 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 0 | 40 | 0 | |

| Hiwassee Fishing | 55 | 77 | 67 | 67 | 73 | 55 | 55 | 62 | 67 | 60 | 71 | 40 | 62 | 80 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 60 | 44 | 80 | 67 | 22 | 22 | 50 | 44 | 0 | 29 | 29 | |

| Hiwassee Bridge | 50 | 60 | 44 | 67 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 86 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 67 | 86 | 67 | 100 | 57 | 67 | 57 | 67 | 33 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Allen | 50 | 60 | 44 | 67 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 86 | 55 | 57 | 60 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 67 | 86 | 67 | 100 | 57 | 67 | 57 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hickory 2 | 67 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 44 | 67 | 44 | 55 | 60 | 50 | 67 | 50 | 55 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 75 | 60 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 75 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 0 | 40 | 0 | |

| Track 1 | 50 | 60 | 67 | 67 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 60 | 44 | 57 | 36 | 57 | 60 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 86 | 67 | 57 | 44 | 67 | 67 | 57 | 57 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hiwassee/Brass | 67 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 44 | 67 | 44 | 55 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 75 | 80 | 57 | 57 | 75 | 57 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 57 | 0 | 40 | 0 | |

| Hiwassee 5 | 50 | 60 | 44 | 44 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 57 | 55 | 29 | 20 | 57 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 44 | 57 | 67 | 67 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 33 | 80 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 50 | |

| Turkey Track A | 50 | 40 | 44 | 44 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 57 | 55 | 57 | 20 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 29 | 22 | 29 | 22 | 33 | 33 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 100 | 40 | 33 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| Turkey Track B | 50 | 40 | 44 | 44 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 40 | 44 | 57 | 55 | 57 | 20 | 29 | 57 | 57 | 29 | 22 | 29 | 22 | 33 | 33 | 57 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 100 | 40 | 33 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| Track 7 | 57 | 44 | 50 | 25 | 57 | 29 | 57 | 44 | 50 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 22 | 67 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 25 | 33 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 80 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 67 | |

| Hiwassee Dogs | 25 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 22 | 29 | 18 | 29 | 20 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 44 | 29 | 44 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 57 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Quarry | 33 | 25 | 29 | 29 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 25 | 29 | 40 | 22 | 40 | 25 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| River Hill 2 | 33 | 25 | 29 | 29 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 25 | 29 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 25 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| River Hill 3 | 33 | 25 | 29 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 33 | 25 | 29 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Motif Category | Likely Physical Correlates | Likely Metaphorical Allusions | Associated Spirit Beings | Interactions with Glyphs | Likely Physiological Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meanders | Trails and lightning bolts connecting different motifs | Spirit energy | Kanati, Thunder Brothers, Judaculla, Uktena, and Little People | Pouring water over a mnemonic map of terrain * | Thunder and lightning, when interacting with spirit beings |

| Cupules | Heads of figures; central fires in concentric circle depictions of townhouses | Points of connection with the world of spirit beings | Little People | Creating rock dust for ingestion, receptacles for medicines, and water * | Physical well-being |

| Vulva shapes | Menstruation and giving birth | Fecundity in the reversed spirit world | Judaculla’s wife | Unknown | Unknown |

| Tracks | Deer and turkey tracks; human and bear footprints | Fecundity connected with the Masters of the Game and their families | Kanati, Thunder Brothers, Judaculla and his family, and Little People | Pouring water over a mnemonic map of terrain * | Unknown |

| Figures | Humans, birds, skeletons, and plants | Transformation, death, and flight | Judaculla and other spirit beings and shamans | Pouring water over a mnemonic map of terrain * | Altered states of consciousness |

| Concentric circles | Townhouses, posts, coiled snake, dance directions, and whirlpools | Community, rituals, and overall renewal | The entire range of spirit beings | Pouring water over a mnemonic map of terrain * | Dancing, fasting, and physical preparation to enter the spiritual realm |

| Cross-in-circles | Central fire within the townhouse | Sun’s life-giving energy and renewal powers | Sun and Selu | Pouring water over a mnemonic map of terrain * | Direct access to Sun and Selu; physical preparation to enter the spiritual realm |

| Spirals | Central fire within the townhouse, Uktena, dance directions, and whirlpools | Movement between life and death | Uktena | Unknown | Dancing and fasting; terror and comfort of encountering spirit beings |

| Straight lines | Boundaries and rivers; Turtle carapace | Places of transformation between the physical and spiritual worlds | Judaculla and Turtle | Unknown | Terror of encountering spirit beings |

| Fine line incisions | Turkey tracks and animal scratches | Success in conflict | Immortals? | Creating fine rock powder for ingestion and purifying rock | Assistance from spirit beings |

| Petroglyph Rock | Cherokee Towns | Corridor | Spirit Beings and Personages | Origin Town | Destination Feature | Ethno-Historic Reference | Trail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track, Young Harris, Soapstone. Golf Course, Chatuge | Valley Towns | Brasstown Creek | Judaculla, Wife, and Twin Children, Animals | Brasstown | Brasstown Bald? | Haywood (1823, p. 280) | Brasstown Creek, Choestoe |

| Fishing, Hiwassee 5 Bridge, Dogs, Brasstown | Valley Towns | Hiwassee River | Uktena, Dogs, Spirals | Aquonatuste? | Peachtree Mound? | Riggs and Ashcraft (personal comm.) | Hiwassee River |

| Judaculla, Brinkley | Out Towns | Caney Creek | Judaculla? | Cullowhee | Tanasee Bald | Parris (1950b, p. 37) | Caney Creek |

| Track | Pigeon River Towns | Pigeon River | Judaculla, Wife, and Twin Children | Kanuga | Tanasee Bald | Mooney (1900, p. 338) | Pigeon River |

| Allen | Lower Towns | Soucee Creek | Thunder Sisters, Turtle, Young Warrior | Săkwi’yi | Tallulah Falls | Mooney (1900, p. 346) | Soucee Creek |

| Gardner | Cane River Towns | Cane River | Kana’tĭ, Twin Sons, Animals | Cane Creek? | Black Mountain | Mooney (1900, p. 243) | Cane River |

| Turkey Track | Middle Towns | Little Tennessee River | Immortals, Turkeys | Coweeta? | Nikwasi Mound | The Franklin Press and Highlands Maconian (1961) | Little Tennessee River |

| Petroglyph Rock | Cherokee Towns | Corridor | Trail | Origin Town | Destination Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hickorynut, Squirrel | Lower Towns | Chickamauga Creek | Chickamauga Creek | Nacoochee Mound? Kenimer Mounds? | Tray Mountain? |

| Reinhardt, Boling Park, Silver City, River Hill | Etowah Towns: Sixes, Red Banks, Hickory Log, Long Swamp | Etowah River Catchment | Etowah River, Tugaloo Trail | Woodland and Mississippian Mound Sites? | Sawnee Mountain? Amicalola Falls? Black Mountain? |

| Shoal Creek, Sprayberry | Etowah Towns: Sixes, Red Banks, Hickory Log, Long Swamp | Etowah River Catchment | Etowah River, Shoal Creek, Little River | Woodland and Mississippian Mound Sites? | Sweat Mountain? Blackjack Mountain? Kennesaw Mountain? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loubser, J.H. “We Begin in Water, and We Return to Water”: Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs of Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina. Arts 2025, 14, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040089

Loubser JH. “We Begin in Water, and We Return to Water”: Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs of Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina. Arts. 2025; 14(4):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040089

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoubser, Johannes H. 2025. "“We Begin in Water, and We Return to Water”: Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs of Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina" Arts 14, no. 4: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040089

APA StyleLoubser, J. H. (2025). “We Begin in Water, and We Return to Water”: Track Rock Tradition Petroglyphs of Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina. Arts, 14(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14040089