2. Cultural Setting

The Klamath Basin of southern Oregon and northern California is bounded on the west by the southern end of the Cascade Range, and on the east by the northwest rim of the Great Basin. To the north lie the headwaters, which include the Wood, Williamson, Sycan, and Sprague Rivers, all of which are significant Upper Klamath Lake tributaries. To the south, the Klamath River drains Upper Klamath Lake Basin, flowing 423 km from the southern end of Lake Ewuana into the Pacific Ocean, bisecting the Cascade and Coastal Ranges (

National Marine Fisheries Service 2007, pp. 2–4). Within the southern portion of the Basin, the Lost River/Tule Lake/Clear Lake Basin water complex is now cut off from the Klamath River, although it was once connected through Lower Klamath Lake during periods of high water (

Dicken and Dicken 1985, pp. 1–4). The Basin’s elaborate system of lakes, marshes, and rivers provided a homeland for the Klamath and Modoc peoples for more than 13,000 years (

Erlandson et al. 2014, p. 778).

Figure 1 shows the Klamath Basin and respective tribal territories.

According to some ethnographic sources, the Klamath and Modoc had once been a politically-unified people. Appearing in Gatschet’s ethnographic sketch, Modoc tribal member Toby Riddle (

Nannookdoowah) reported that the Klamath had separated from the Modoc around A.D. 1800 and had not lived together since. She went on to add that the

Gumbatwas band of Modoc had separated from the Klamath sometime in the 1830s (

Gatschet 1890a, p. 13). Today, many members of both tribes deny this claim, arguing instead that they were created separately by

Kumush (Gmok’am’c) but have always been a separate but

related people. Discussing the nature of the relationship between these groups is beyond the scope of this paper. I bring it up, however, because, no matter how they were related, these two groups continue to share the same language, customs, and myths in common. For that reason, unless I distinguish them in some way, I will refer to these groups collectively as the Klamath–Modoc in this paper. More to the point, the cultural similarities they share also significantly influence the way their ethnographic literature and myths can be applied to the rock art across the Klamath Basin.

The rock art in this region consists primarily of circles, concentric circles, zigzags, a variety of geometric figures, and various abstract designs. Although a comprehensive count has not been forthcoming, hundreds of rock art sites are at present known to exist in the Klamath Basin. In his 1963 publication Klamath Basin Petroglyphs, Swartz examined 119 of these sites and created site records for each, which he added to his comprehensive (yet unpublished) data report, of which the author has managed to obtain a copy. In 2003, my first year of fieldwork for my masters’ thesis on Klamath Basin rock art, my crew and I went on to count forty-four additional sites that are not included in Swartz’s 1963 data report. I counted no less than a dozen more later in the same decade while doing my PhD fieldwork through the University of California Berkeley. And I have since encountered a handful of previously undocumented sites in my various field studies since earning my doctorate, including one discovery in the summer of 2024. Yet even with my addition to Swartz’s original 119 recorded sites, I feel we have only scratched the surface. With all of the privately owned ranches, coupled with hundreds of miles of unexplored rimrock and canyons scattered across the Basin, I suspect that discoveries will continue to be made, inadvertent or otherwise, for many decades to come.

3. History of Research

For over a century now, researchers have been attempting to understand this vast corpus of rock art from a variety of perspectives. From the late 19th to the middle 20th century, government-sponsored researchers and academics alike took systematic approaches to both classify and study the meaning behind this rock art. In these early studies, however, researchers did little to consult with Native peoples beyond eliciting their help in locating sites. Even when they did, they made no effort to accommodate their explanations for the art. It is thus not surprising that the explanations that resulted from their studies echoed the western perspectives that were inherent in their research methods and at the same time told us nothing about the rock art.

- A.

Picture Writing

In his survey of North American rock art,

Mallery (

1893) set out to prove that the pictographs among Native North American cultures rested someplace on a continuum that would ultimately culminate in a developed system of writing (and thus, denote each group’s inevitable progress toward civilization). His guiding argument was that rock art was part of a global form of picture-writing that could be deciphered if enough data could be collected. Owing to the requirements put forth by congress in their development of the Bureau of American Ethnology, his study was limited to rock art produced by Native American groups within the United States (

Mallery 1893, p. 25). Nonetheless, because of prior studies, he was also able to refer to Maya hieroglyphs in Central and South America and identify them as his case in point (

Mallery 1893, p. 26). Notwithstanding his problematic reliance upon unilineal evolution, Mallery’s consultation with Native peoples served first and foremost only to sustain his own ideas. He dismissed out of hand the explanations they offered about the rock art:

Persons of these tribes when questioned about the authorship of the rock drawings have generally attributed them to supernatural beings. Statements to this effect from many peoples of the three Americas and of other regions, together with the names of rockwriting (sic) deities are abundantly cited in the present work. This is not surprising, nor is it instructive, except as to the mere fact that the drawings are ancient. Man has always attributed to supernatural action whatever he did not understand.

Rather than follow up on these Native claims about shamans and spirits and learn how they related to rock art, Mallery dismissed them as expressions of ignorance. Unfortunately, his dismissal would be repeated in the academic literature for many decades to follow.

- B.

Culture History

Between around 1910 through 1960, a period known to archaeologists as Culture History,

Steward (

1929) and later,

Swartz (

1963) classified certain rock arts of the Klamath Basin into various stylistic categories in an effort to trace them back to their regions of origin. By categories, I am referring to rock art designs that have usually been called “curvilinear,” “rectilinear,” “angled,” “naturalistic,” “Great Basin Scratched,” and so on. Under the Culture History paradigm, stylistic traits in artifacts and rock art imagery were taken to represent the mental template of the cultures that produced them. Thus, identifying such stylistic traits was the first step in tracing their pathways from the Klamath Basin back to their cultures of origin. The general assumption was that no two cultures could ever think up the same stylistic traits. Their appearance in more than one culture was regarded as evidence that they had diffused from one culture to the other, or that they had both diffused from a common culture of origin yet to be discovered. Accordingly, the archaeologists of this period assumed that none of these stylistic categories originated in the Klamath Basin. But by comparing their local statistical occurrence with rock art from the surrounding regions, it was possible to trace a path back to their cultures of origin, which would exhibit the highest statistical occurrence of these same stylistic traits. Working under this assumption, both

Steward (

1929, pp. 58–59) and

Swartz (

1978, p. 22) mapped out a complex set of pathways in which people were thought to have brought their ideas (i.e., their stylistic traits) into the Klamath Basin.

According to this scheme, the Klamath–Modoc people only later came to occupy the Basin without having the slightest notion where the “existing” rock art imagery had come from. In this way, by laying claims of authority over local Native voices, archaeology became yet another western tool for colonizing Native communities by distorting or even erasing their history.

- C.

The New Archaeology

There came a time in the history of archaeological thought, however, when archaeologists themselves grew wary of the Culture History agenda, especially how it went about to explain the past. These archaeologists questioned the normative view of culture and expressed doubt about the relationship between cultural traits and human beings, which, by and large, was the essence of Culture History. With the advent of radiocarbon dating, cultural sequences in the archaeological record could for the first time produce calendric dates and contribute significantly to building amazingly accurate cultural chronologies. But, in place of compiling mountains of data for the sole purpose of building ever more cultural chronologies, these new archaeologists argued that data should be used to test hypotheses that would more thoroughly and credibly answer questions about the past. Accordingly, this new breed of archaeologists, who came to be called “Processualists,” strove to be scientific in their approach. They eschewed the default assumption of diffusion to explain cultural changes in stratigraphic sequences (and stylistic traits in rock art) and turned instead to studying environmental processes, which could now be studied with the rapidly improving scientific methods at their disposal.

The discipline, then, embraced all aspects of the archaeological record that could be radiocarbon dated or yield any information about the past using the scientific method. All other aspects of culture that could not be treated with this method were relegated to the fringes of academic inquiry. Items and features in the archaeological record that were associated with spirituality were regarded as being secondary to things associated with subsistence and ecology (i.e., projectile points, grinding materials, middens, pollens, site formation processes, etc.). How this affected Native American heritage was that sacred peaks, rivers, sacred objects, features such as rock piles in the mountains, and especially rock art, ceased to be studied. The result of this is what

Keyser (

2005, p. 218) called an “academic eclipse” in rock art research. Subsequently, the absence of academic study left a void in rock art literature that came to be filled by what Keyser went on to describe as “a few groups of loonies who envision themselves as Ogam ‘scholars,’ or discoverers of solstice markers or ancient space ports” (

Keyser 2005, p. 220). Between around 1950 through 1980, these absurd claims enjoyed the public limelight. In this time of UFO-mania, the idea of visits by ancient astronauts recorded in Native American rock art found fertile ground in the mainstream, who otherwise lacked any other information to challenge it.

- D.

Post-Colonial Critique

Whether by pure academic research that eschewed the Native voice, or by the absence of research that could have contradicted the absurd claims made by these sensationalists, Native American rock art came to be regarded and understood in completely non-Indigenous terms. Because it was something in the human past that could not be known through scientific inquiry, it came to be regarded as something that could not be legitimately known at all. In some academic circles, this sentiment still persists. Whereas Native American oral traditions and myths were not compatible with the scientific method, the new archaeologists moved the Indigenous voice yet another step further away from its rock art heritage. More simply put, in this way, archaeology continued to colonize the Native American past.

Why this obsession with archaeology’s colonizing effects on Native American heritage? When considered within the context of centuries of disastrous encounters with Whites (Indian wars, genocides, catastrophic epidemics, federal assimilation programs, and brazen Indian child removal programs (

Simmons 2014, p. 2), one cannot help but see how the systematic reification and outright disenfranchisement of Native American heritage via archaeology served only to compound and exacerbate their damaging effects. By altering or erasing Native American ideologies, past archaeological practices have been very effective in achieving what the aforementioned assimilation efforts have been pursuing for more than a century.

- E.

Decolonizing Perspectives

Fortunately, understanding these colonizing effects within the framework of this history also provides a pathway for the development of an archaeology that strives to be restorative and beneficial to Native Communities. As Professor Sonya Atalay has pointed out,

In examining this history and bringing it to the foreground, these [Indigenous and non-Indigenous] scholars are creating a counter-discourse [emphasis mine] to the Western ways and colonial and imperialist practices of the past and are working to find new paths for a decolonized archaeological practice- one that is first and foremost “with, for, and by” Indigenous people.

At its very core, this is the decolonized approach I take to studying the rock art of the Klamath Basin. And to this end, the available myths and ethnographic literature in this region continue to play a pivotal role. As an Indigenous archaeologist, my primary mission is to conduct the kind of archaeology that has the potential to return some aspects of our heritage that were thought to be “lost” through our tragic history of colonization. Our traditional religion, in particular, was specifically targeted by the Klamath Agency Superintendent who would go to great lengths to install Christianity on the reservation, and at the same time take measures to eradicate our traditional religion (shamanism)—even going so far as placing shamans in jail who continued to practice their craft, and making them return the fees they received for their services (

Stern 1966, p. 111). As shamanism gradually diminished on the reservation, so too did the practice of making rock art, which once again was the exclusive realm of shamans. In time, knowledge of the rock art faded, and today, few (if any) tribal members can recall the role it once played in our culture.

4. Methods

Among the primary tenets of decolonized archaeology is that Native methods and epistemologies are transported from the margins of academic research to its center. This is intended to ensure that any interpretation offered for the indigenous past does not carry forward the colonialist narrative. But although this is a very reasonable approach, one problem that arises from this practice stems from the unavoidable fact that many Native voices today have themselves been significantly colonized. Not only by a dark history of federal assimilation efforts and archaeological practices of the past, but also by sensationalists authors who fill knowledge gaps with their absurdities in the absence of sound research—absurdities built upon Native American peoples’ implied relationship with ancient astronauts. For this reason, uncritically moving Indigenous voices toward the center of any interpretive framework runs the risk of falling short in challenging the colonialist narrative. This, of course, is not to say that Native American communities that have experienced colonization and often draconian efforts at assimilation have not maintained some degree of traditional cultural knowledge. But it has been my experience that, for one reason or another, those who maintain certain traditional cultural knowledge within Native communities are seldom consulted during any stage of an archaeological project.

It is for these reasons that my efforts to incorporate Native American perspectives into my research program focuses not only on information provided by modern tribal community members, but also on the myths, language, ethnographic, and ethnohistoric records that were provided by Klamath–Modoc

ancestors. These records were informed and provided by members of these tribes who had lived in what Spier calls the “old” life (

Spier 1930, p. vii;

Ray 1963, p. vi). As such, their memories and first-hand experiences provide an excellent base of knowledge that can be used as checks and balances against statements made by modern tribal peoples, where they can be further interrogated and evaluated critically for their correspondence.

Although numerous (if not all) indigenous communities suffered varying degrees of cultural loss as a result of assimilation and colonization, these losses were certainly not equivalent in scale and severity. The range of variation extended from minute to moderate on one hand to total extinction on the other. With regards to rock art, the degree to which any surviving community retained cultural knowledge could fall at any point along this continuum. With such a wide range of variability, it seems only reasonable to draw from Native perspectives, both present and past, in order to create a more comprehensive and self-correcting framework in which to analyze and approach an understanding of locally-produced rock art. I discuss these sources in more detail below.

4.1. Field Methods

Although the concept of decolonized archeology will never likely gel into a cohesive, one-size-fits-all approach, more and more archaeologists who practice this kind of archaeology strive to include Native partners in every stage of the project, including the planning phase. For that reason, field methods are typically decided upon by both the archeologists and their Native partners. Given the number of Native tribes in the United States, and their abundant diversity, field methods will certainly vary from one tribe to next and from situation to situation.

Prior to beginning my research on the rock art of the Klamath Basin, I met with the Klamath Tribes Culture and Heritage Committee in order to discuss my proposal so that we could collaborate on the research plan, including the field methods. For the most part, I was left to my own devices on how I would document the rock art sites and collect my data. Tribal stipulations, however, stated that the rock art would not be directly touched, photographs would not be taken of rock art associated with cremations and burials, and the locations of rock art sites that had not been developed for public viewing, such as Lava Beds National Monument, would be kept confidential. While the tribe had no mandate that tribal members participate in the fieldwork, three tribal members actually did work with me for the duration for my thesis project starting in 2003, including one Modoc elder. Others sporadically worked with me during my dissertation fieldwork a few years later. A final stipulation was that the Klamath Tribes were to receive copies of all of the Site Forms and a copy of my (then) Master’s Thesis (

David 2005), and later my dissertation (

David 2012), for the tribal archives. Even today, some 22 years since beginning my fieldwork, this is the protocol I continue to follow.

With regards to my fieldwork, my typical method begins with a survey of the site so that I can learn the extent of the rock art panels, followed by a pedestrian survey around the site in all directions so that I can be sure to contextualize the rock art within the localized archaeological signature. Using this information, I make a rough site sketch that includes the general shape and size of the rock formations that contains the rock art. I then proceed to give each of the known panels an alpha-numeric designation. Using blue painter’s tape and a black Sharpie felt pen, I create labels for each panel and carefully place them on the rock face in a way that avoids the images. Following this, we take a minimum of two photographs of each panel—one with a 10-cm scale and label in frame and another without. When necessary, we used homemade reflectors to eliminate shadows. We also photograph associated site features and include one image of the prevailing site aspect and one perspective photo for each panel as well. The accompanying photo journal incudes the panel/image designations we created at the beginning of the process, along with a photograph number, which is automatically designated by my Nikon D-40 digital camera. This method provided ample photos of the imagery for both the site report and for my analysis as well.

Depending on the condition of the rock art, I often have to enhance the imagery with Photoshop or something as simple as Microsoft Picture Manager once back in the lab, depending on its availability. Enhanced images are “saved as” with new designations, while the originals are saved unchanged. Later, we stipple-trace each of the enhanced images onto mylar transparency film using black, fine-point Sharpie pens, making sure also to trace the 10-cm scale in order to maintain their correct proportions. We chose to do it this way so that we would not bring the mylar into direct contact with the rock art, per the Culture and Heritage Committee’s stipulations. The site designation, the project name, panel and image nomenclature, date traced, and the name of the recorder are placed in the upper right-hand corner of each tracing. Finally, the tracings are scanned into an electronic file and subsequently photo-reduced for use in site reports and in future documents and public presentations. The original tracings are placed in a large manila envelope labeled with all of the site information and saved as a part of the site’s permanent record. This record would accompany the updated site report sent to the appropriate government agency and to the Klamath Tribes Culture and Heritage Department. As for the enhanced photographs and the stipple-tracings, they would ultimately be used in the resulting monograph as well as in presentations to the Klamath Tribes and to the general public when appropriate. Notably, only later in my rock art career did the Klamath Tribes specifically request PowerPoint presentations for the tribal membership as part of my dissemination efforts.

As I hope is apparent, I have planned my research as much in partnership with the Klamath Tribes as I was able, and I continue to make every effort to use this research for the benefit of the Klamath and Modoc tribal communities.

4.2. Interpretive Methods

Understanding Klamath Basin rock art requires a robust familiarity with the local ethnographic literature, mythology, and artistic conventions used to depict the imagery—the complex interrelationships they share as well as their limitations. To foreground our discussion, it is important to note that both the Klamath and Modoc ethnographic records are equally useful for understanding the rock art imagery of this whole region. As previously indicated, the reason for this is that even though they are separate (but related) groups (

Stern 1966, p. 2), the Klamath and Modoc continued to share the same language, customs, and myths in common. The result is that the worldview that led to the production of Klamath rock art is the same that led to the production of Modoc rock art. Accordingly, it is appropriate to use the combined ethnographic literature and mythic tales from

both groups to obtain a holistic understanding of their worldview and thus enable a better understanding of the region’s entire corpus of rock art.

4.2.1. Ethnography

To begin this section, I find it necessary to acknowledge the challenges involved with relying on the ethnographic record for either direct interpretations for local rock art or even for useful insights. As has been widely pointed out, ethnographic studies provide a very limited snapshot of a culture at a particular point in is history. As a result, when we as researchers rely on ethnographic studies to understand rock art that frequently dates back centuries before the creation of the ethnographic record, we face the risk of essentializing the ethnographic population. At the same time, we risk inappropriately imprinting information from the ethnographic present onto the distant archaeological past. The methods I use for consulting the ethnographic literature and bringing it to bear on Klamath Basin rock art are intended to mitigate these concerns and are presented in the paragraphs to follow.

By and large, Klamath Basin ethnographic materials offer little discussion on rock art. Direct statements made about rock art by Klamath–Modoc people in these texts are few, and those that exist are often cryptic and shrouded in cultural metaphors. Misunderstood by ethnographers, these statements were dismissed out of hand. Fortunately, one thing the ethnographic literature

does provide is certain knowledge of the rock art’s origins. Without fail, Klamath Basin ethnographic literature attributes these markings to the work of shamans (

Gatschet 1890a, p. 179;

1890b, p. 149;

Dennison 1879;

Spier 1930, p. 142). This, at the very least, prompts us to make vigorous inquiries into the topic of shamanism itself, with the goal of discovering how and where rock art fits into this spiritual complex.

Referred to as

Kiuks by the Klamath–Modoc, shamans were the ritual practitioners of the community who performed a variety of services with the aid of spirit-helpers. Foremost among their services include diagnosing and curing sickness, controlling the weather, finding lost objects, and foretelling the future (

Spier 1930, p. 118). If rock art played any role in these services, we should expect to see the spirits who specialized in these powers depicted in the art.

The three primary ethnographic works consulted for this chapter are those provided by

Gatschet (

1890a),

Spier (

1930), and

Ray (

1963). Each of these works discusses different aspects of aboriginal shamanism in the Klamath Basin and together provide enough information to form a framework for understanding the practice, its underlying philosophy, and a working knowledge of the conditions under which shamans created rock art.

Although

Gatschet’s (

1890a,

1890b) work focused extensively on the Klamath language, it also deals to some degree with their legends, traditions, and beliefs. Two points in his materials that are of particular significance to my ongoing research include his discussions on the supernatural beings that feature in the mythic tales and his list of shamans’ incantations. As Spier later noted, mythological beings are often the same beings that shamans used as spirit-helpers in their ritual practices (

Spier 1930, p. 103). Accordingly, Gatschet’s descriptions of these beings offer insight into their supernatural powers, and thus insight into their actual use within the shamanic practice. Augmenting these descriptions is his collection of shamans’ incantations (

Gatschet 1890a, pp. 153–59, 162–63, 164–71, 173–75). These are the sacred songs that shamans used to invoke their medicine spirits in preparation for performing tasks that required supernatural power (i.e., medicine). The fact that many of the incantation subjects are the same mythological beings Gatschet described elsewhere in his text allows us to effectively link the shamanistic practice itself to Klamath Basin mythology. Given the one-to-one association between shamans’ spirit-helpers and these mythological beings, Klamath Basin mythology has proven to offer tremendous insight into their supernatural powers, essentially explaining

why shamans would have used these beings in their ritual enterprise. From here, if it can be shown that these same mythological characters regularly appear in Klamath Basin rock art; it is not hard to imagine the tremendous interpretive potential myth can provide for rock art researchers in this region.

Along the same lines, another element of the ethnographic record that is seldom consulted in rock art studies is the role of ritual singing. This is surprising when one considers that, among the Klamath–Modoc, singing was a critical component of spirit-seeking activities such as the traditional power quest. The acquisition of songs in dreams was believed to denote the manifestation of spirit power that resulted from these rituals (

Spier 1930, pp. 94, 112;

Ray 1963, pp. 34–35). We are thus very fortunate that Gatschet included various incantations of both the Klamath and Modoc shamans in his ethnographic sketch. These incantations provide not only the identities of powerful spirits, but they also contain volumes of information that often describes in considerable detail the nature of their supernatural power. The potential for interpretive power arising from both myth and these sacred incantations is unprecedented in the study of Klamath Basin rock art.

Missing from Gatschet’s ethnographic report, however, is a comprehensive discussion on shamanism. As

Spier (

1930) later noted, this makes it difficult to understand the meaning of the shamans’ incantations and allied topics he included in his two-part volume. For this reason, Spier thought it appropriate to devote considerable space in his own ethnographic study entirely to shamanism. From his study, we get a good working knowledge of its underlying principles, familiarity with certain rituals and ceremonies, and the identities of some of the shamans’ primary spirit-helpers.

Finally,

Ray’s (

1963) ethnography on the Modoc was actually begun by Spier in 1934. But Spier subsequently turned his notes over to Ray, who had been a member of the original field crew and directed him to finish the monograph. As with Spier’s ethnography on the Klamath, Ray’s work offers a general survey of Modoc lifeways with ample space devoted to shamanism, including useful descriptions on shamanistic performances and what he calls a ritual curing séance (

Ray 1963, pp. 55–59). This once again provides us with materials that both supplement Spier’s discussion on Klamath shamanism and adds to the list of mythological beings that shamans used as spirit-helpers that may have been depicted in rock art.

His detailed description of the shaman’s curing procedure identifies a number of the spirit-helpers needed for each phase. This would later provide me with a useful model for predicting which spirits we should expect to see in rock art if such art had been created and used as a part of ritual curing (

David and Morgan 2024). Notably, the mythic tales often describe important spirits and the ritual behaviors associated with them in their purest form. That is, while information presented in the ethnographic literature is a direct result of prompting by ethnographers’ questions, their appearance in

myth comes directly from the memories and worldviews of the tellers. It is not shaped or prioritized by ethnographers’ questions, and the tellers are under no pressure to either remember or to make sense out of potentially misguided inquiries.

4.2.2. Mythology

There are few words more frequently misused than “myth.” In both academic and non-academic circles, the mere mention of the term implies a negative connotation that equates these traditional stories with what many would regard as fairytales. To set the record straight, myth, as an anthropological term, refers to a collection of often sacred narratives that contain and exemplify a culture’s worldview. Gatschet, in fact, likens them to a culture’s “national literature” (

Gatschet 1890a, p. 1). Among the Klamath–Modoc peoples, these stories are regarded as being sacred in that they depict a more complete picture of the world than is apparent to mortal eyes. They achieve this by illustrating both the natural, physical world and the invisible

spiritual world around them that is operating simultaneously. The mythical characters, often personified as animals, frequently exhibit tremendous supernatural powers which can only be harnessed and controlled in the physical world by shamans. Thus, many of the animals in these tales are the same spirit-animals that provide shamans with “medicine.” In this way, myth makes real the spirit world and justifies the supernatural powers claimed by shamans. With this in mind, my use of the term “myth” here should be equated with the term, “sacred narrative.” And to be clear, I do not avoid using the term and thereby validating its gross

misuse by others.

As a culturally-informing literature, myth has no equal. We are fortunate that the Klamath and Modoc tribes have an extensive collection of these sacred narratives and that many of them have been codified in writing (see

Curtin and Curtin 1884;

Gatschet 1890a;

Barker 1963). The most comprehensive collection of these have been housed at the Smithsonian Institution for more than a century and they consist of materials contributed by Jeremiah and Alma Curtin (

Curtin and Curtin 1884) and

Gatschet (

1890a). But starting in the late 1980s, tribal members Gordon Bettles and Mary Gentry transcribed these materials and placed them on a 5 ¼ inch compact disk. In 1991, they distributed copies to the head of each family within the Klamath Tribes. I received a copy in 2002.

Collectively known as the Modoc Myths, these are the primary materials I have drawn from in the preparation of this paper. Once again, my bridging argument is that many of the powerful beings from these stories feature prominently in Klamath Basin rock art and are discernible if one understands the underlying philosophy of the Klamath–Modoc spirit world and how it was expressed in the shamanistic practice. As previously noted, this information is abundantly available in the local ethnographic texts.

4.3. Local Artistic Conventions

Another avenue leading toward an understanding of Klamath Basin rock art involves acquiring a familiarity with local artistic conventions and the spiritual philosophy that inspired them. As elsewhere, these conventions symbolize important religious concepts. In the Klamath Basin, some of the artistic conventions used in the rock art find their justification in the ethnographic record and myth. I provide examples below.

4.3.1. Skeletons, Stick Figures, and Associated Paraphernalia

Spirits, by their very nature, are invisible. This poses a challenge for any ritual practitioner needing to depict their spirit-helpers (i.e., medicines) on mediums such as rock faces. In the Klamath Basin (and elsewhere), artistic conventions appear to have been developed to overcome this very problem. Two of the most common ways ancient artists used to convey the concept of “spirits” was to depict skeletal figures and stick figures. Both of these conventions depict figures that pointedly lack flesh but simultaneously denote the presence of the intended spirit beings. Skeletal figures are unequivocally associated with death, and thus they convey the concept of “spirit”, while stick figures symbolize animals or humans reduced to their barest essence, absent body mass, and thus conveying something akin to the idea of the “soul”.

Another way early artists denoted the presence of a particular spirit was by depicting the spirit’s associated medicine tool in place of the spirit itself. In Klamath–Modoc myth, for example, the creator spirit

Kumush had for his medicine the sun disk. All throughout these tales, the sun disk was credited with maintaining his immortality (

Curtin and Curtin 1884, p. 223) and sometimes used to bring people back to life in his sweat lodge (

Curtin and Curtin 1884, p. 216). Accordingly, when we see the sun disk depicted in the rock art (

Figure 2), the spirit

Kumush is present by implication.

4.3.2. Synecdoche

Another convention widely used in rock art is synecdoche, where the depiction of a part represents the whole. Local ethnographic materials provide some justification for the use of this convention in Klamath Basin rock art. According to

Spier (

1930, pp. 132–33), supernatural power could not only be obtained from an animal spirit as a whole, but also from its individual parts. While in the rock art we sometimes encounter somewhat complete depictions of spirit beings, more often we see only the head, eyes, hands, digits, or even footprints. Sometimes, we are also presented only with an outline of the being’s face like the owl’s face shown in (

Figure 3).

Another example of synecdoche has to do with supernatural vision. For example, how does one denote

supernatural vision? How does one depict their ability to see into the spirit world? Given that the spirit world is understood to exist inside the earth (in rocks, underground, under water, etc.) (for example, see

Barker 1963, p. 73;

Curtin and Curtin 1884, pp. 74, 130, 176, 254, 357, 669, 687), one very common Klamath Basin motif depicts the “almond” outline of an eye, and quite often directly associated with a crack or fissure in the rock face. In

Figure 4, the eye figure has been rotated so that it sits vertically on a natural fissure in the rockface, thereby presenting an eye that has a unique perspective and a direct connection to the spirit world (

David and Morgan 2024, pp. 98–99). As elsewhere, only the parts of the animal or entity that are spiritually useful to the shaman-artist are depicted.

4.3.3. Symbolic Inversion

Another aspect of Klamath–Modoc spirituality that carries over into rock art is what Whitley calls “symbolic inversion” (

Whitley et al. 2004, pp. 4–5). As with other Native communities in far western North America, the spirit land is perceived as an inversion from the natural, physical world (

Spier 1930, p. 102). Although they rarely show up in the Klamath Basin, some rock art images symbolize this relationship, often by being situated on top of and below a fissure or crack in the rock’s surface (see

Figure 5). The crack itself, in fact, played an added role in conveying the idea of “spirit land” upon the arrangement. This is because cracks and fissures were believed to be portals through which shamans or their spirits traveled back and forth from the supernatural world (

Whitley 1998, p. 16;

Keyser and Poetschat 2004, pp. 120–212;

David 2012, p. 29). Images directly associated with these features, then, may be thought of as the figure’s simultaneous presence in both the physical and supernatural worlds.

4.3.4. Therianthropes

A final aspect of shamanism that translates over to the rock art is the depiction of therianthropes. These are images that feature a blend of human and animal characteristics. Therianthropes are a worldwide occurrence in rock art, from the “Sorcerer” painting from Trois-Freres in Ariege (

Figure 6) to the Great Basin “Rattlesnake Shaman” shown in

Figure 7 (see

Whitley 1998, p. 17, Figure 2.5). Local ethnographic literature provides a cultural reason for the presence of these types of images in Klamath Basin rock art. According to Spier,

The shaman is possessed during his performances. He is the vehicle of the spirit; the spirit sings with his voice, sucks with his lips, and sees with his eyes. It is not in him at other times, but in its home in the mountains or under the water and must be called on to enter his body [1930:109].

A shaman “possessed” by an animal spirit is exactly the condition in which the characteristics of two or more entities might be combined to form a single rock art motif. The implication is that therianthropes are depictions of shamans as they appear in their spirit form, “possessed,” as it were, by their animal spirits.

When taken in conjunction with the ethnographic record and mythology, a good working knowledge of local artistic conventions helps to make visible spirit-helpers where others in the past have only seen “human figures in costumes, wearing animal masks,” or “anthropomorphic motifs with angular or curvilinear elements.” All of these resources combined constitute the ancestral Klamath–Modoc perspective that is central to my rock art research program in this region. In the following section, I provide two case studies that demonstrate my methods in action.

5. Case Studies

- A.

Deusowas

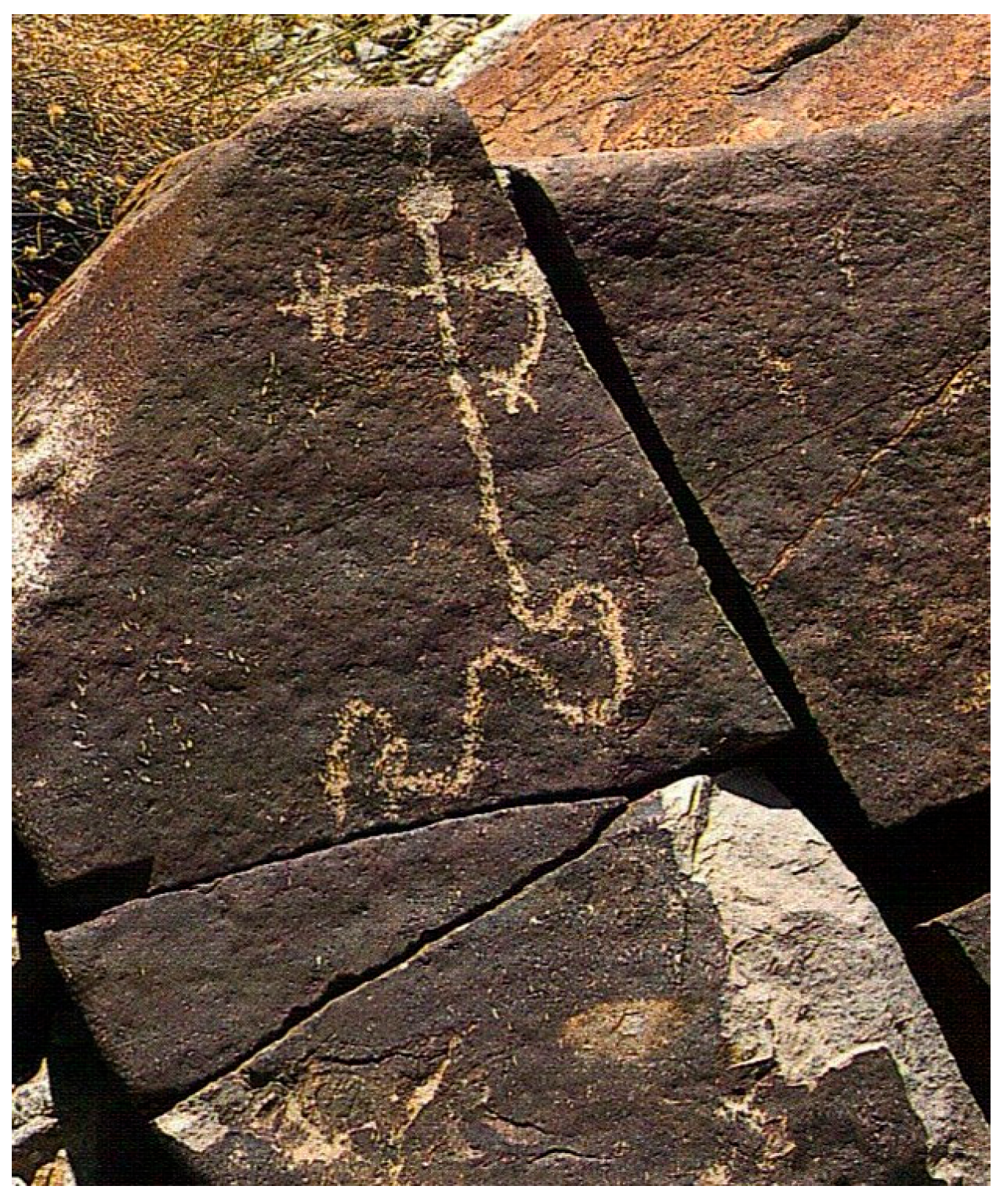

The first example is an image from Petroglyph Point, a site on a prominent rock outcrop in the Lava Beds National Monument in northern California (see

Figure 8).

Commonly referred to in myth as “the island” or “the mountain,” this landmass is believed by the Klamath–Modoc to be the world’s creation point and is regarded as the most sacred place in the Modoc homeland (

Whitley et al. 2004, p. 231). The image in

Figure 9 is but one of over 5000 images that have been engraved into the soft volcanic tufa that comprises this mountain (

Lee et al. 1988, p. 19).

First and foremost, this figure’s depiction of a being with both human and non-human characteristics identifies it as a therianthrope, and probably represents a depiction of the shaman-artist himself in the act of channeling his animal spirit-helper. Judging from the figure’s elongated limbs, neck, and three-digit extremities, the animal characteristics suggest that the spirit is a kind of wading bird such as a crane, egret, or the great blue heron, all of which are common to the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge, just a few miles west of Petroglyph Point.

The first thing to consider for analysis is the place’s traditional name. Modoc Myth 107 identifies this mountain (i.e., Petroglyph Point) as

Deusowas, or the place of the “stork’s” bill (

Curtin and Curtin 1884, p. 217). The reference to the stork’s

bill is important here because it highlights the part of the bird that is used to kill its prey. More to the point, it highlights the part of the bird that turns its prey into a

spirit! From this we may surmise that

Deusowas is a place where spirits are available, or where one may become a spirit, as shamans are commonly reputed to do. In that regard, the spirit “Stork” that dwells in this mountain facilitated such a transition.

Before proceeding it is worth clarifying a point regarding the stork. The stork is a wading bird that actually inhabits

tropical and

subtropical regions around the world and has

never been present in the Klamath Basin—at least not during the long millennia that the Klamath and Modoc have occupied this region. How the stork entered into the Modoc vocabulary (let alone mythology) is beyond the scope of this paper. But a deeper look into the Modoc Myths reveal that the bird in question goes by the Modoc term, “gah-gash” (

Curtin and Curtin 1884, p. 422). In the Modoc language, “gah-gash” is the term used to identify the great blue heron (see

Gatschet 1890b, p. 163). For this reason, I will use the word “heron” in place of “stork,” but with the acknowledgment that the term “stork” persists in the Curtin set of Modoc myths (1884).

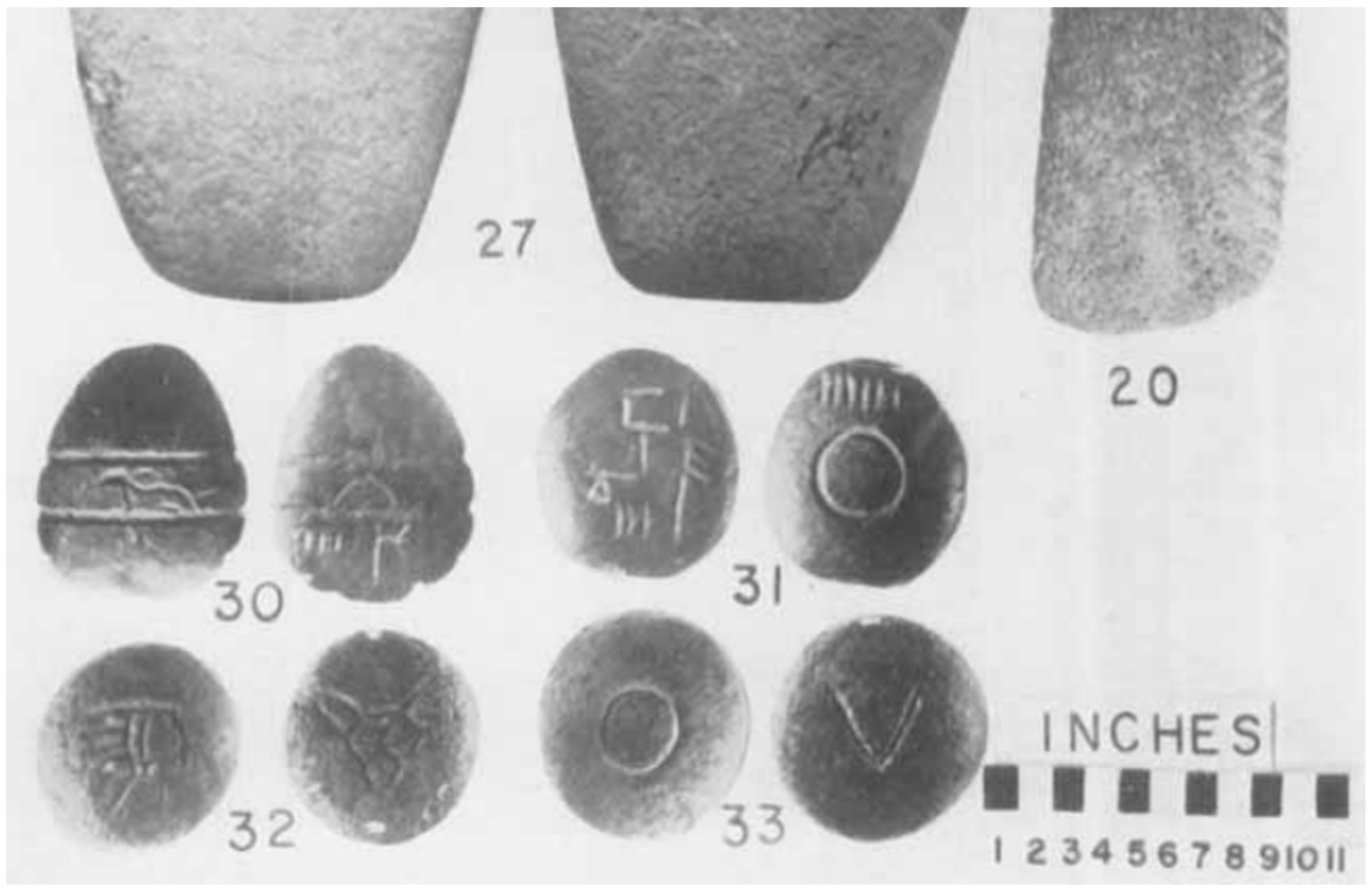

A final observation regarding this image is the way the inverted “V” replaces the figure’s head. The “V” symbol (inverted or otherwise) is very common in Klamath Basin rock art and features very prominently on Petroglyph Point. Insights into the meaning of this symbol can be obtained from a study published in 1959 by Ron Carlson. Carlson had been the curator of Klamath County Museum when he was presented with a curious stone statuette found by a local fisherman. His inquiry into the statuette inspired a more thorough study of a small collection of other stone objects that either bore incised markings or were culturally shaped in some way. Carlson noted that four of these stones bore markings that were similar or identical to markings found on Petroglyph Point (

Carlson 1959, p. 92). As shown in

Figure 10, one of these marked stones featured an incised “V”. Klamath tribal member Elizabeth “Lizzy” Kirk, who eventually sold the collection to Carlson, told him that the four inscribed stones were medicinal heating stones she had obtained from a man named Reinhold, who himself received them from a shaman and was meant to help him with his rheumatism (

Carlson 1959, p. 92).

What we are to take away from Mrs. Kirk’s explanation for the inverted “V” design on her heating stone is that it is ethnographically associated with shamanic medicine (

Carlson 1959, p. 92). This makes it reasonable to apply this interpretation to the same “V” symbol depicted on the therianthrope in

Figure 8 from Petroglyph Point. When taken together with Spier’s information regarding how shamans channeled their medicine spirits in the performance of their rituals (

Spier 1930, p. 109), it becomes apparent that the transmogrified human figure in this image is channeling the spirit of a wading bird that is most likely

gah-gash, the Great Blue Heron for whom the site is named, and is thus empowered with its medicine.

- B.

Latkakawas

The second example comes from site located at place called

Uxotuash—or the Wood Knot. Identified by Swartz as MPt-13 (

Swartz 1978, p. 31), this pictograph site consists of four distinct panels containing red and red and white polychrome figures. The main panel, shown in

Figure 11, features thirteen white and red and white circles and constitutes our main focus in this paper. The red arrow near the top of the photo points to a curious, faded figure that resembles a fish. Some tribal members regard it as a depiction of a salmon. Based on this identification, a few have concluded that the whole site constitutes an ancient “fishing calendar,” which unfortunately can no longer be read.

Before proceeding, it is worth noting that neither Klamath–Modoc ethnography nor mythology reports that these tribes ever relied upon an artificial calendar to inform them about when was the right time of the year to harvest fish. According to

Spier (

1930, p. 146), their subsistence cycle depended on the availability of resources, such as the blossoming of certain plants and the first signs of the fish runs. In other words, these tribes scheduled their movements around the natural growth cycles of their resources—from the first signs of spring to the return of winter. To date, no other tribal explanation for the site has been forthcoming. Unfortunately, the information about this site provided by the ethnographic literature is equally opaque. While both

Gatschet (

1890a) and

Spier (

1930, pp. 20, 143) mention

Uxotuash in their ethnographic texts, only Spier notes the presence of rock art. But since he did not personally visit the site, he could provide no insights into the imagery.

Fortunately, Modoc Myth M-107, the story of Latkakawas, describes the activities of all of the supernatural beings that are relevant to this site. In the process, it also suggests a very detailed interpretation for the imagery. Given the length of the tale, I have paraphrased it below:

Latkakawas was a beautiful blue woman who lived on the south side of Klamath Lake. Young men from all over the region wanted her. But whenever they attempted to approach her, she would turn herself into an old hunchbacked woman digging roots before they could see her in her true, beautiful form. Latkakawas could always tell when they were coming to see her.

But there was one young man living on the west side of the lake who was blue just like her, and he wanted to see Latkakawas. One day, assisted by his father, he dressed in all his finery and wore a bright beautiful disk as a sort of crown, and then set off to see Latkakawas, traveling under the ground. True to her nature, Latkakawas knew he was coming. But because she knew he would not laugh at her as the others had done, she allowed him to see her in her true, beautiful form.

The next day, the young man set out to see Latkakawas again, intending to marry her. This time, he traveled under the water still wearing the bright disk. In the meantime, Latkakawas’ brothers had returned from fishing and were preparing to move to their spring camping place, located at Uxotuash. They set out in their canoe, but Latkakawas’ blue lover had caught up to them by then and was holding the canoe in place from under the water, not allowing them to break away from shore. This went on until around mid-afternoon. When he finally did let go, the brothers proceeded to paddle toward Uxotuash, while the blue young man followed them from under the water, keeping pace with the canoe so that he could continue to gaze upon Latkakawas. But at some point, the youngest of Latkakawas’ brothers saw a bright, shiny spot in the water following them and thought it was a salmon. Without thinking, he speared and killed Latkakawas’ lover.

Once they realized the mistake, Latkakawas’ brothers took her lover’s body to shore and cremated him along with all of their wealth. Eventually, the only thing that remained in his ashes was his brilliant sun disk. Her brothers told Latkakawas to take the disk to Kumush, who could use it to bring her lover back to life in his sweat lodge at Nihlaksi village. Latkakawas took up the disk and departed right away.

About half way to Nihlaksi, Latkakawas stopped to camp for the night. While there, much to her great surprise, she gave birth to a boy, which had been fathered by her blue lover only the day before. The next day, when she reached Kumush’s sweat lodge at Niklalshi, Kumush did, in fact, succeed in returning her blue lover to life using the sun disk. But Kumush, envious of the sun disk’s power of resurrection and of its brilliance, wanted to keep it for himself and so he immediately willed the blue young man dead again.

Grief stricken, Latkakawas strapped her child to her back and rushed to jump into her lover’s cremation flames. At the last minute, however, Kumush attempted to stop her from jumping in, but missed her and managed only to rescue the baby. Latkakawas was consumed by the flames with her lover. When the flames died, Kumush took the disk and placed it in the center of his back, where it became a permanent part of him. Then he took the baby to live with him on the southern side of Tule Lake.

The three main points from the story that are relevant to the rock art imagery include the following: the confusion experienced by Latkakawas’ younger brother, which lead him to mistake her lover for a salmon and kill him; Kumush’s association with ritual curing, which essentially identifies him as a shaman; and, Kumush’s use of the sun disk to successfully return Latkakawas’ lover to life, which essentially identifies the sun disk as a supernatural medicine tool—one capable of returning a person to life.

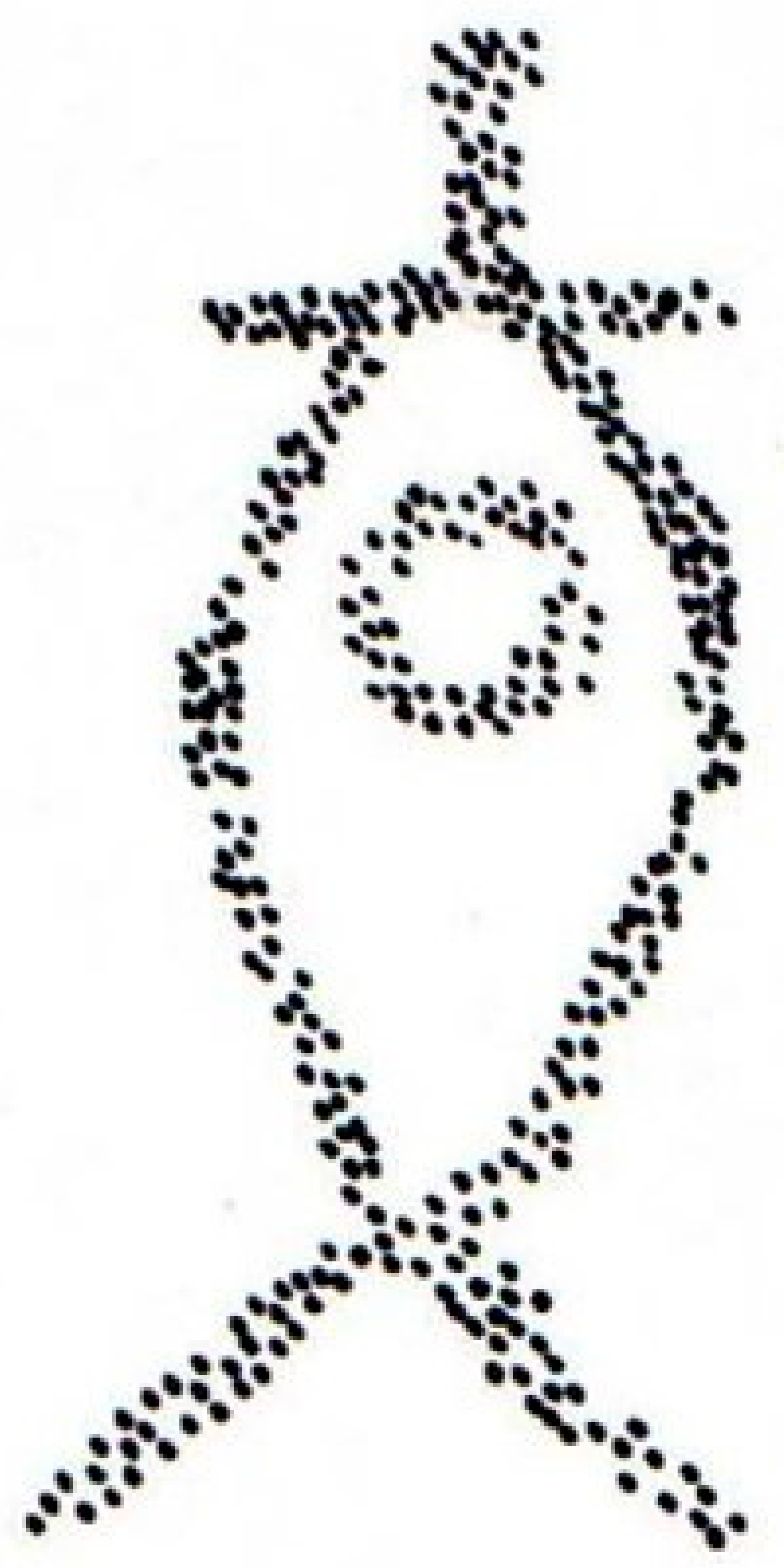

What we’re seeing in

Figure 12 is a painting of a human that was intentionally created to be confused with a salmon wearing the sun disk of

Kumush on his torso. The stipple-tracing in

Figure 13 more clearly defines this image. But while the parallel with the story is apparent, this depiction is not simply a reference to the story of

Latkakawas: what we’re seeing, in fact, is a depiction of the part of the story where the curing power of the sun disk

worked! This is an image of

Latkakawas’ blue lover, whom

Kumush had

returned to life in his sweat lodge using the sun disk. It is

not a picture of a salmon. Neither is it part of some mysterious fishing calendar. In actuality, this image is a picture of curing magic in action. Thus, it provides the site with a strong, metaphoric connection to

Kumush’s power to cure with the use of the sun disk.

In a larger sense, this whole site is a

medicine site, whose function is underscored by the presence of

Latkakawas’ resurrected lover. It is significant to note that an act of shamanic curing took place at this site in mythological times—shamanic curing that pointedly included the use of the sun disk. For this reason, we do not see

just Latkakawas’ blue lover depicted at this site: as shown in

Figure 10, we see

all sorts of

painted disks right along with it, indicating that this place was laden with spiritual potency. And it is because we know the myth that we have the ideological tools to make this connection.

For anyone studying the spiritual systems of the Klamath and Modoc peoples, it is imperative that the local ethnographic record and myth are regarded and used as mutually-complementing sources of literature. When taken together, these two sources have the potential to provide tremendous interpretive potential for Klamath Basin rock art.

6. Conclusions

Since becoming an archeologist, my research agenda has been one of cultural revitalization. More specifically, it has been to research and publish on all aspects of my tribal heritage that has been adversely impacted by colonization. In that respect, rock art has been at the forefront of my research efforts.

The reason that knowledge of our rock art heritage has diminished in our communal memory can be traced back to our early life on the old Klamath Indian Reservation. One of the first things government-appointed religious leaders tried to eradicate as a part of President Grant’s Peace Policy was our traditional religion which, of course, was shamanism (

Stern 1966, pp. 111–13, 116, 118). Rock art, as we have already seen, falls entirely under the province of shamans (

Dennison 1879;

Gatschet 1890a, p. 179;

Spier 1930, p. 142). Accordingly, when shamanism was outlawed and eventually faded from prominence in our culture, so too did our understanding of rock art.

Given all of the years of the federal government’s appalling efforts to assimilate the Klamath Basin’s First Peoples into the American mainstream, it is not only ethical that we as archaeologists eschew western ideologies in our research of Native heritage, but we also move Native voices to the very center of our interpretations, where they rightfully become the tellers of their own history. This is the only way that this kind of research can empower Native communities to tell their own histories free of western colonial influence.

Sadly, however, even a “Western-free” approach in our research methods and interpretations is not always free from this influence. When we center Native perspectives in our research, we are prioritizing voices that have been the sole targets of religious and governmental assimilation programs for more than a century. While it is certainly true that some members of ours and other tribal communities have struggled nobly to maintain traditional cultural knowledge, there is no guarantee that these are the people who occupy official, tribal positions as cultural specialists. Anthropologists, however, tend to consult with those who have been placed in these important cultural positions under the reasonable assumption that these “cultural specialists” have been appointed to these positions because of their cultural expertise. But, as an Indigenous Archaeologist, it has been my misfortune to realize that those who hold these important cultural positions tend to be no more culturally competent than anyone else in the community. The criteria under which they have been hired usually falls under the umbrella of “Indian preference,” without requiring any further demonstration of competence. Perhaps it is inevitable that, under pressure from the expectations demanded by their positions, these “cultural experts,” go on to make the boldest proclamations about our tribal heritage that turn out to have no cultural foundations whatsoever.

My point here is not to denigrate tribal hiring practices, nor the good intentions of hiring tribal members to fill these important cultural roles. Rather, my purpose is to raise awareness among my colleagues who are devoted to using their archaeological expertise as a tool for decolonization. As an indigenous archaeologist devoted to cultural revitalization, it is my responsibility to those whom I serve to assume the burden of qualifying the statements and testimonies given about our traditional cultural history by comparing them with every scrap of literature (written or oral) that represents the voice of our ancestors and to use this comparison as a basis for further evaluation.

This is the essence of my methodology. And while it has, for the most part, lead to friendships and alliances within my tribal community, it has also led to some contention. But I would be doing my tribal community a colossal disservice by uncritically incorporating potentially ill-founded interpretations into our tribal historical narrative.