Signalling and Mobility: Understanding Stylistic Diversity in the Rock Art of a Great Basin Cultural Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

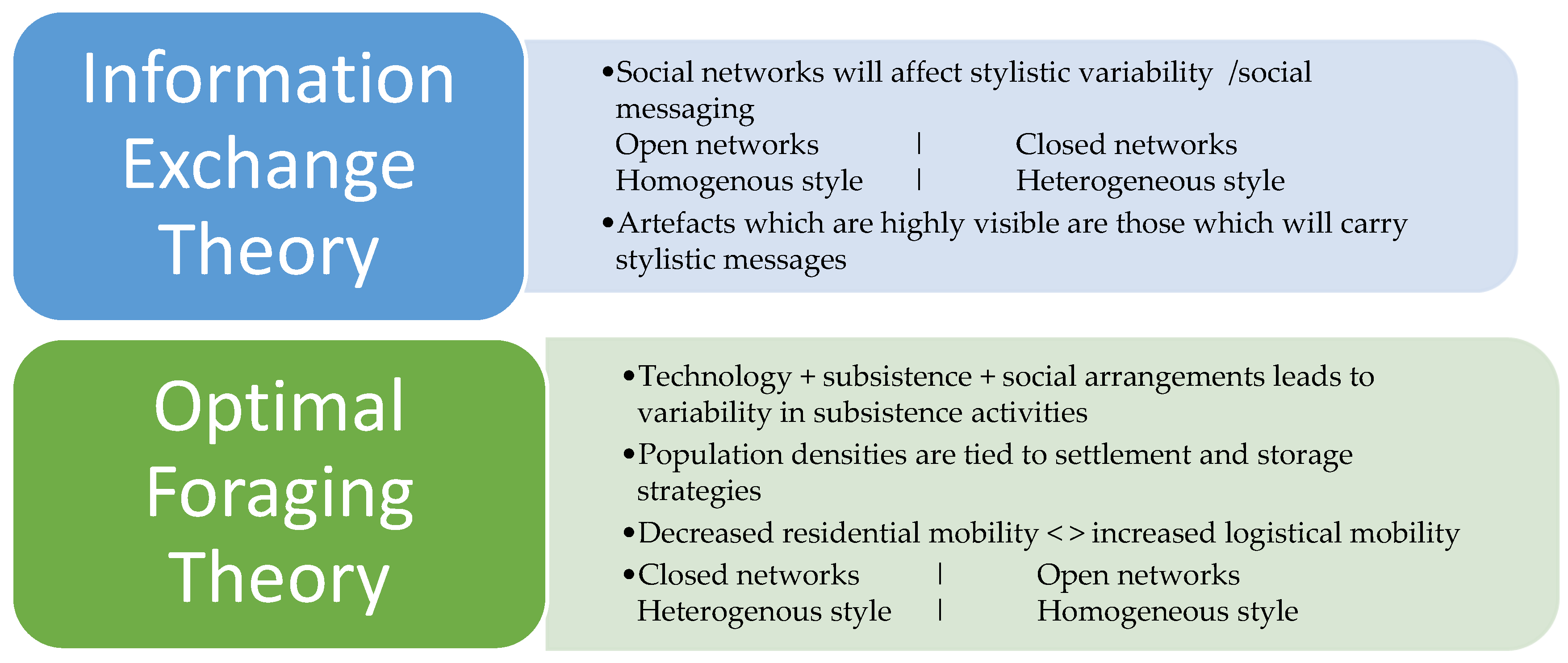

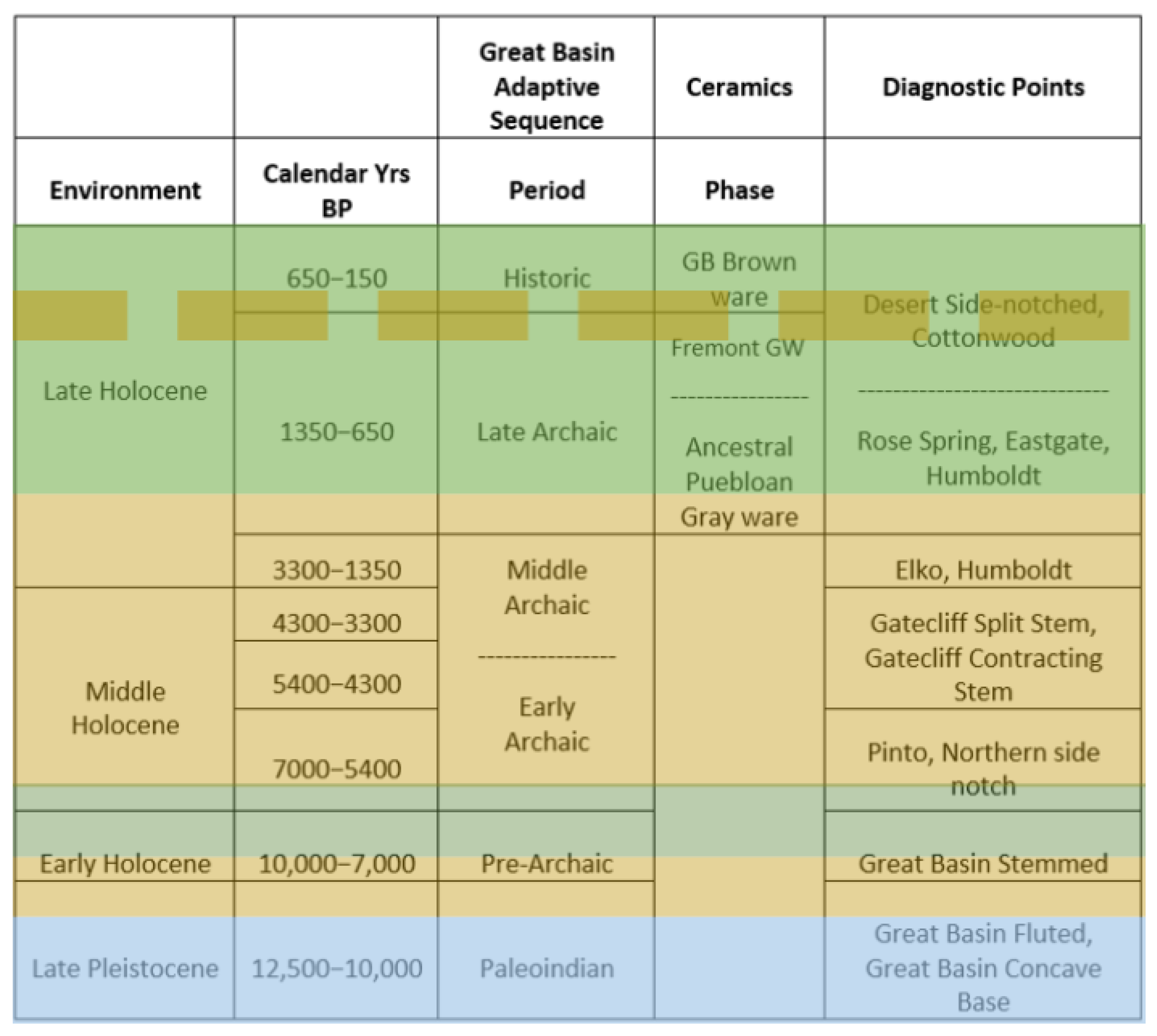

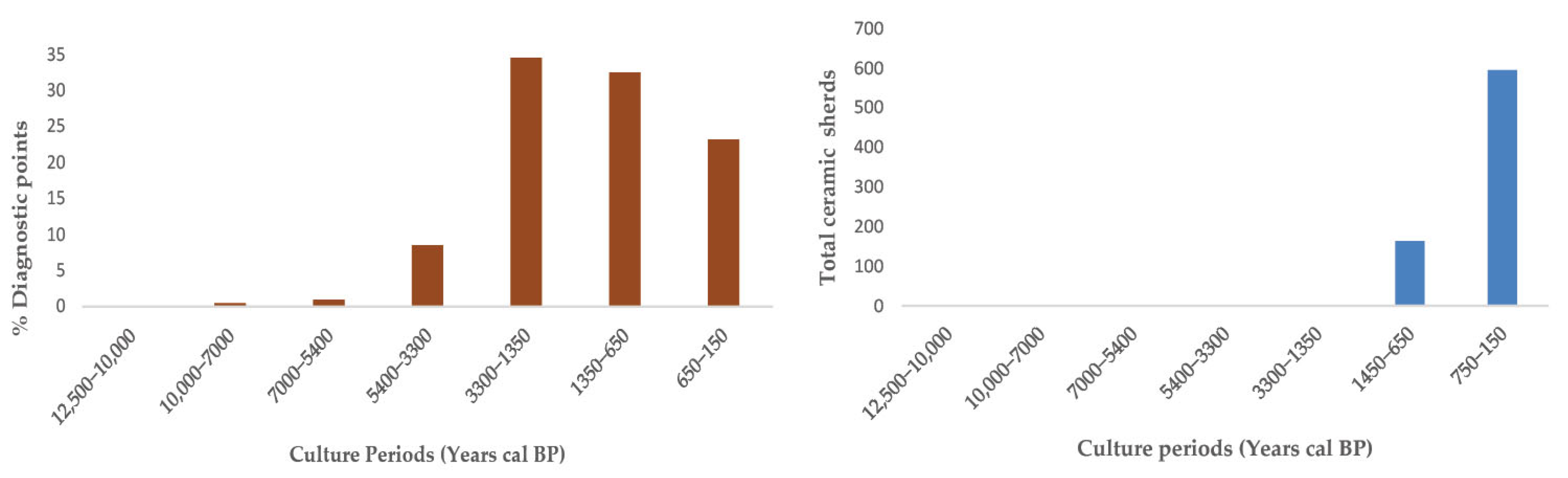

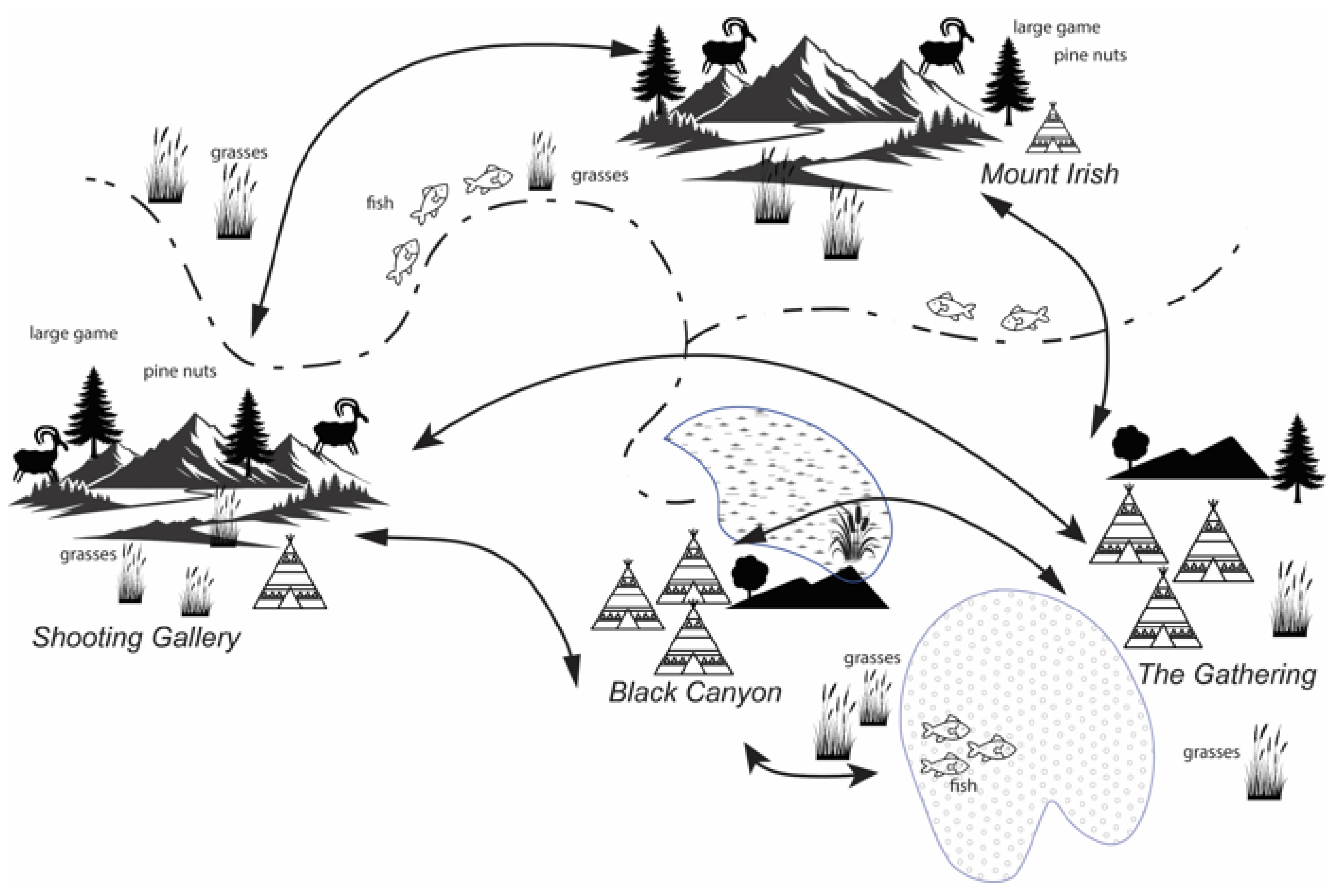

Modelling Rock Art into the Great Basin Occupation Sequence

3. Results

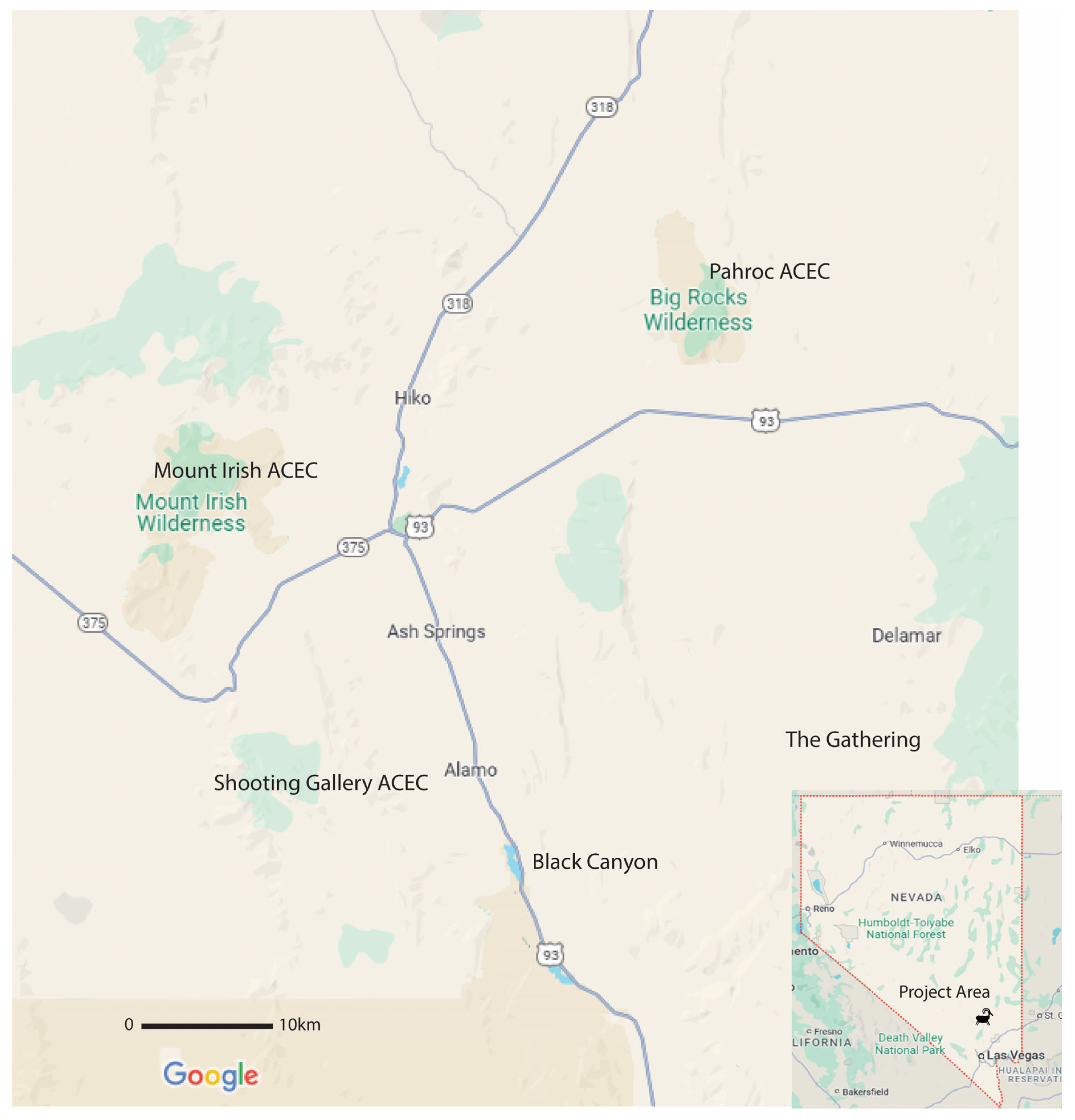

3.1. Rock Art in Pahranagat Valley (Lincoln County, Nevada)

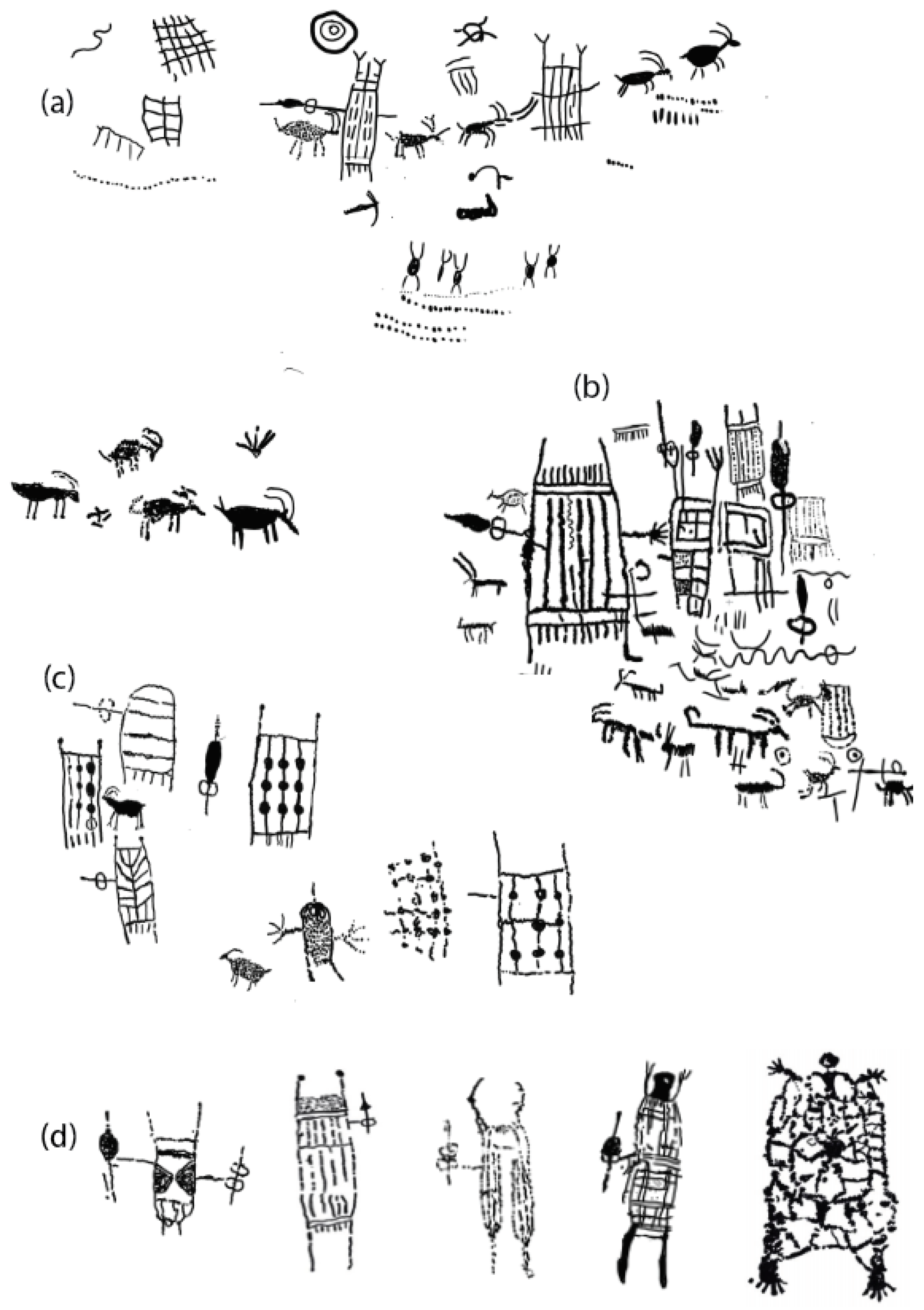

3.2. Water Babies and Atlatl-Bearing Hunters

“Headless (?) rectangular figures whose dress is indicated by lines of dots or connected solid circles. Each figure holds an atlatl. We believe these rectangular figures are, despite their stylized form, atlatl-bearing hunters.”

“…powerful spiritual beings that are associated with water and volcanic places. They live in flowing water of many kinds including rivers and artesian springs and frequently travel through natural and manmade hydrological systems. Water babies are considered to be female and are often described as around three feet high with long hair and shell-like skin. The tremendous power of water babies is complex, making them very special spiritual helpers for a shaman (Puha’gant), but also incredibly dangerous for those unable to control the power…their connection to water made them very valuable for rainmaking activities”.

- How stylistically similar are these motifs across the region and through time, and what does this tell us about regional signalling behaviour?

- How can we interpret the spatial and chronological distribution of these motifs?

- Are the solid- and patterned-bodied figures (and Bighorn sheep and atlatls) co-located?

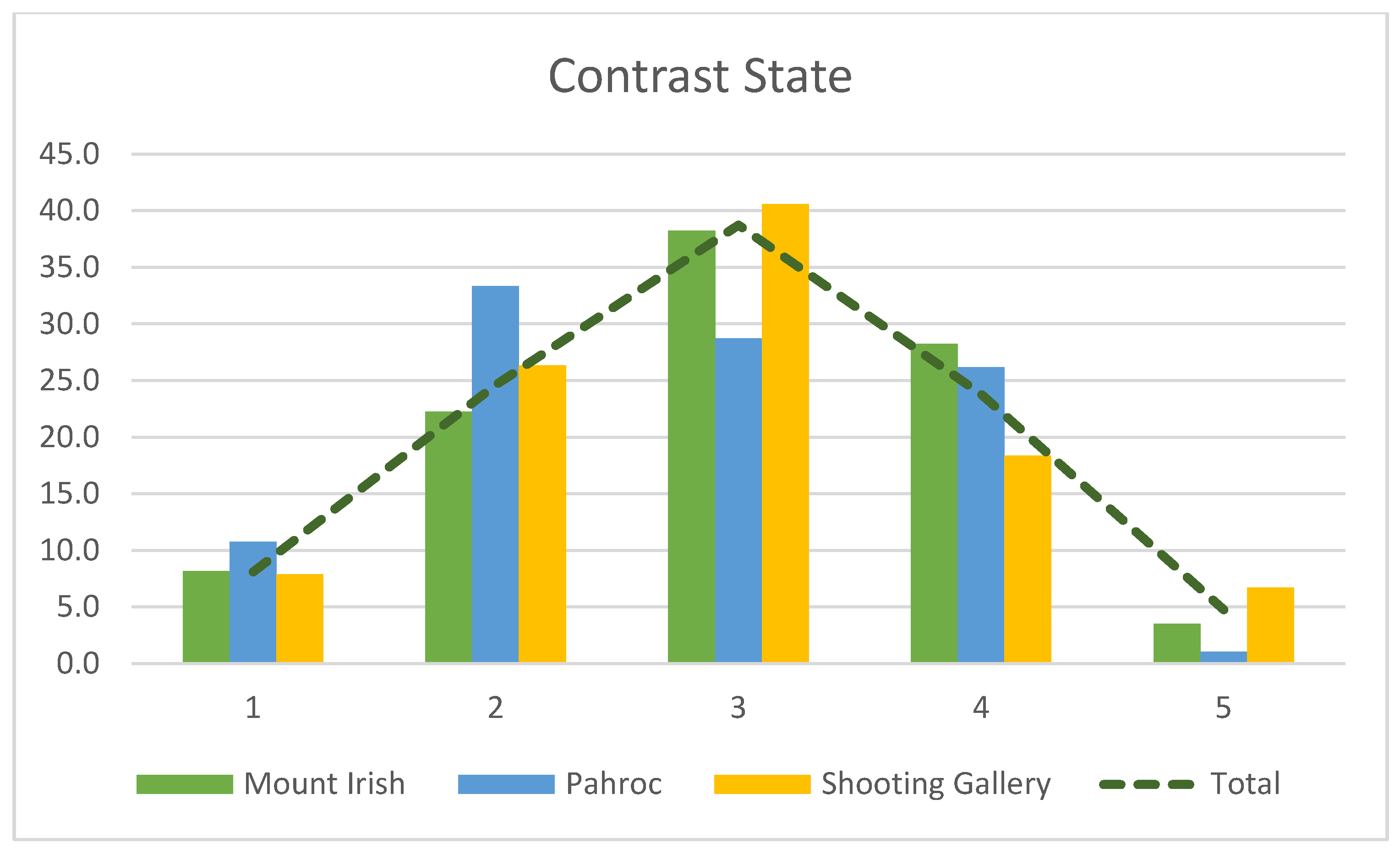

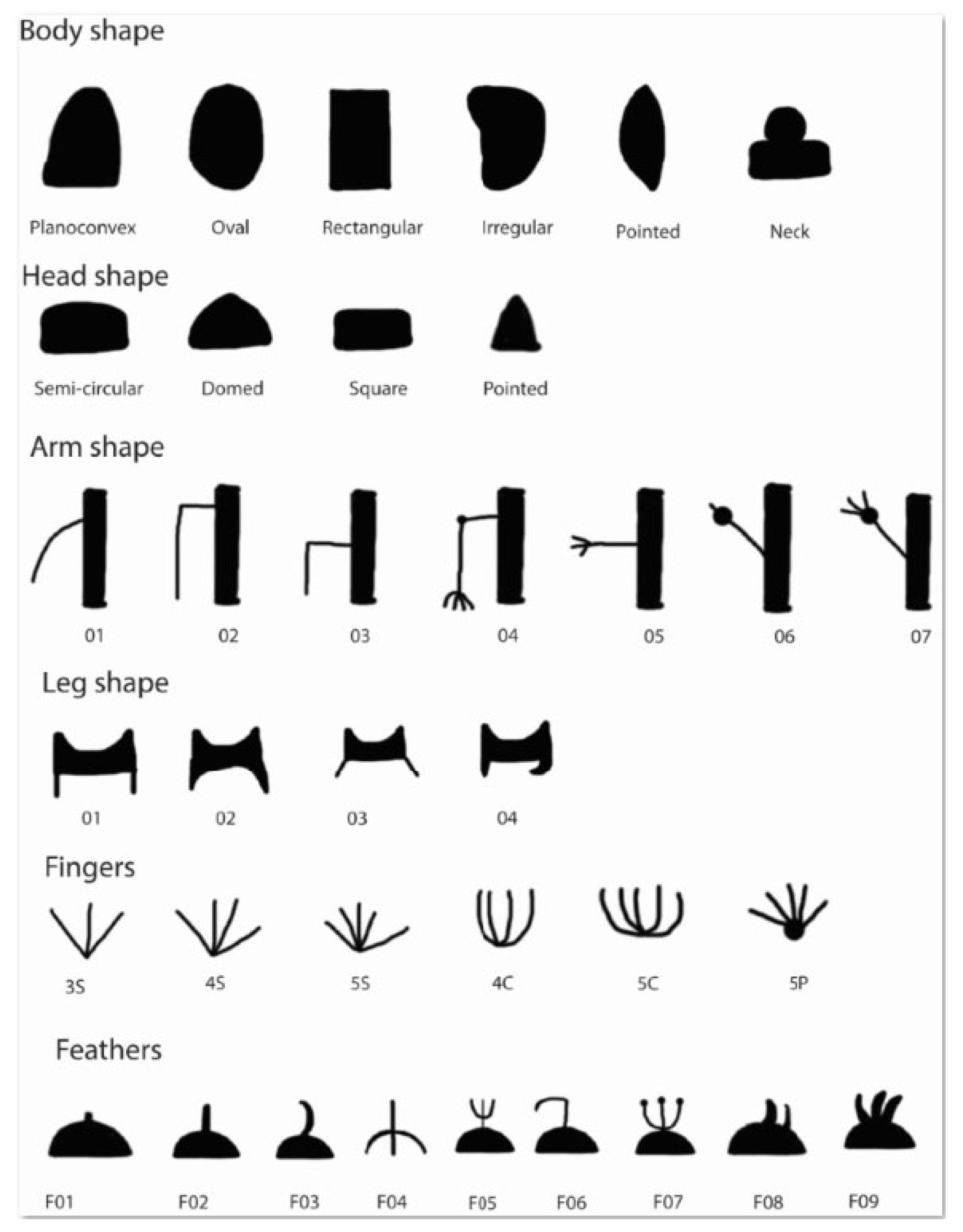

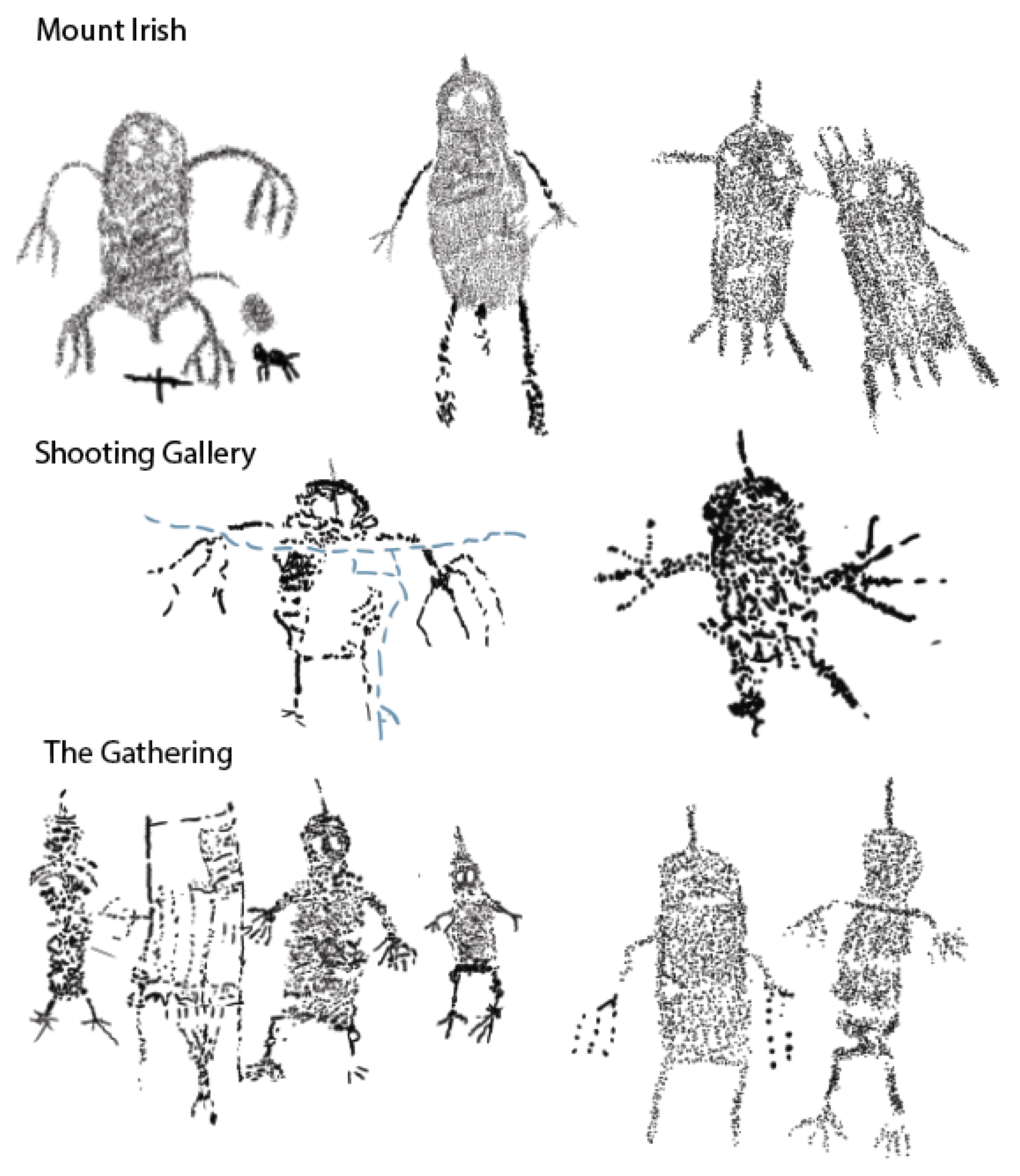

3.3. Solid-Bodied Pahranagat Anthropomorphs (Water Babies)

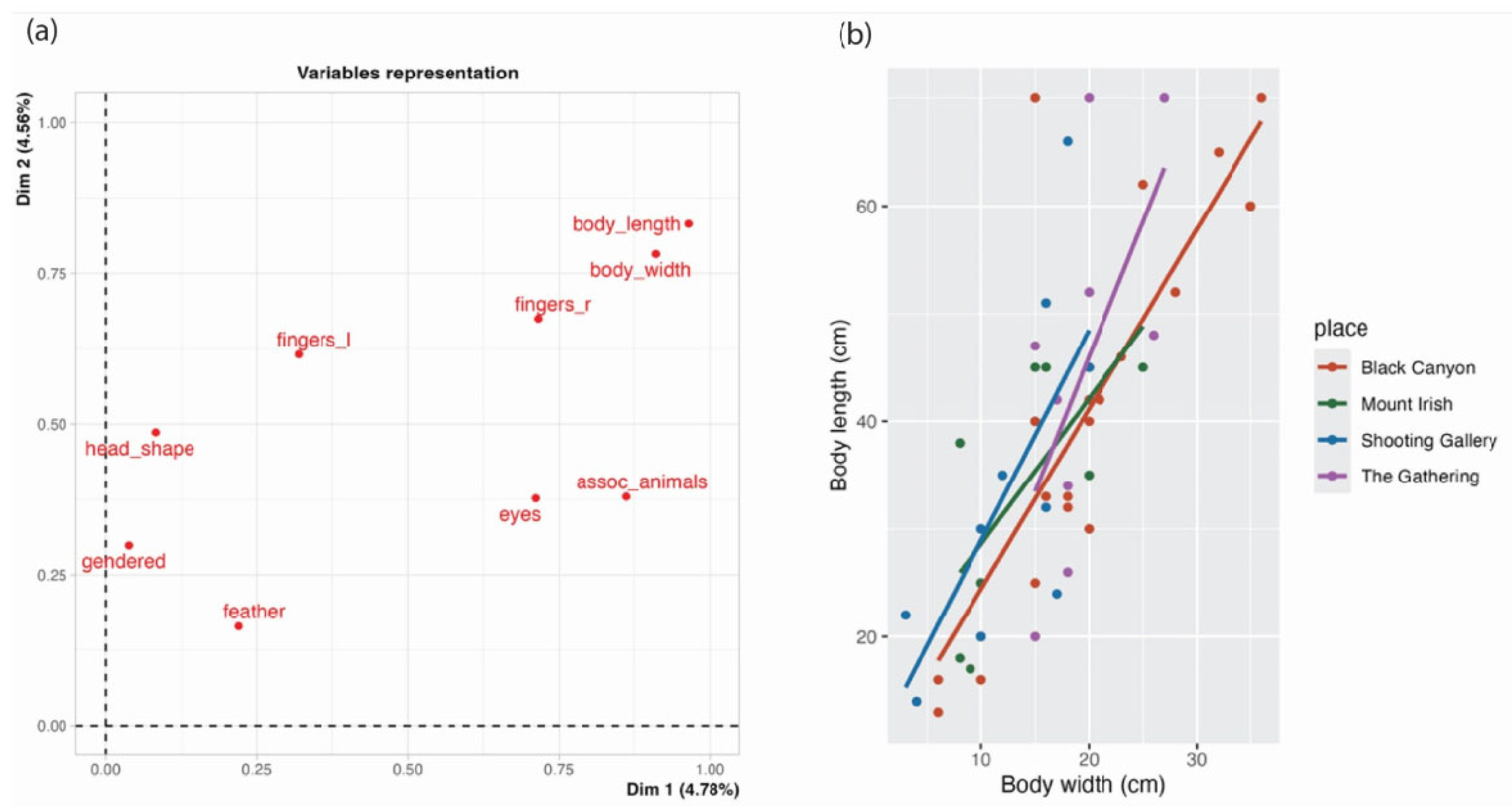

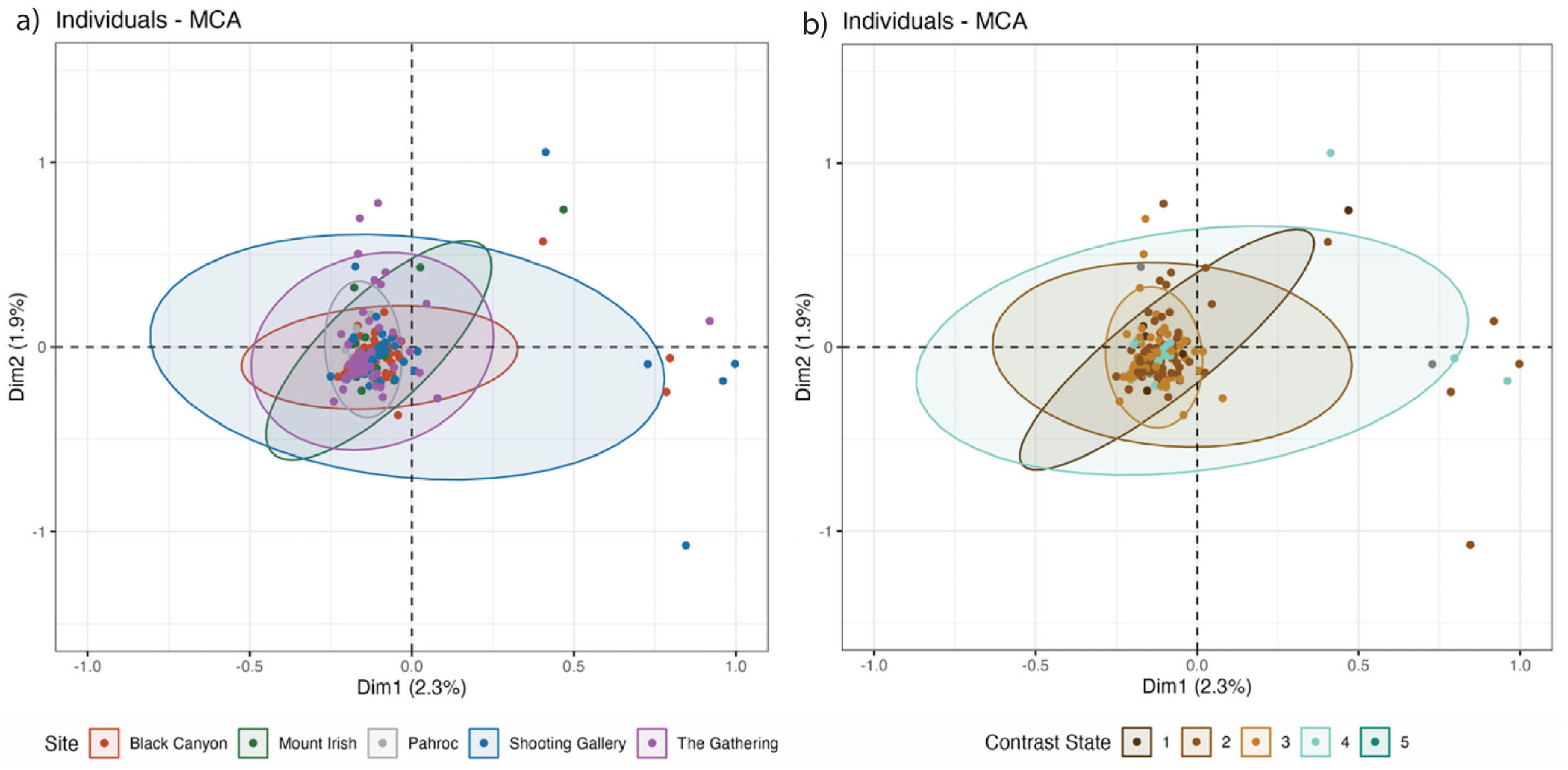

Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

- Those from Black Canyon tended to have squarer heads and rectangular shorter bodies. Three panels here revealed subsequent production events and/or refreshing of a slightly altered form and/or placement in a proximal location.

- Those from Mount Irish tended to have the most variability in body shape (distribution on Dim2), splayed legs (Type 2), and exaggerated arms with large digits, with round heads and square (planoconvex) bases. Several have been ‘refreshed’ or superimposed by newer motifs.

- Those from The Gathering formed the tightest cluster: these motifs tended to have longer, thinner bodies, three toes on each foot, and several had necks (see below).

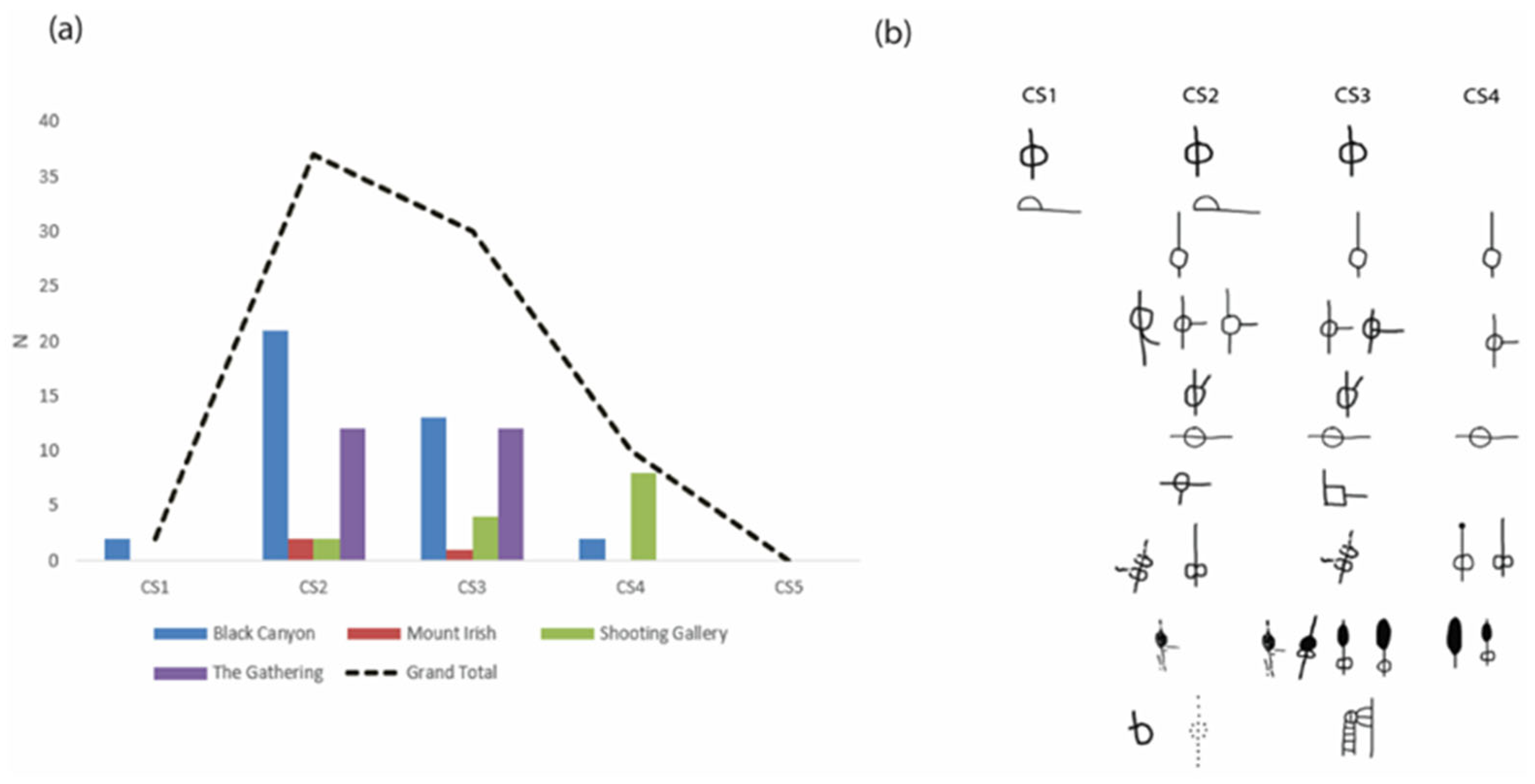

- The earliest SBs were produced at Black Canyon (n = 1) and Mount Irish (n = 2).

- Most SBs were produced in CS2 and CS3. The main production centre in CS2 appeared to be Black Canyon, at which time there was the most stylistic heterogeneity displayed in the assemblage. Production in CS3 was shared between Black Canyon and The Gathering, at which time the regional stylistic homogeneity increased.

- No SBs were created at Black Canyon and The Gathering in CS4 and CS5. Increasing stylistic homogeneity was demonstrated in this timeframe at both Shooting Gallery and Mount Irish.

- A single (visually atypical) SB occurred at Shooting Gallery in CS5: MCA placed this within the variability range of CS3. Two SBs at Mount Irish were either retouched in this phase (see Figure 11) or superimposed by other motifs.

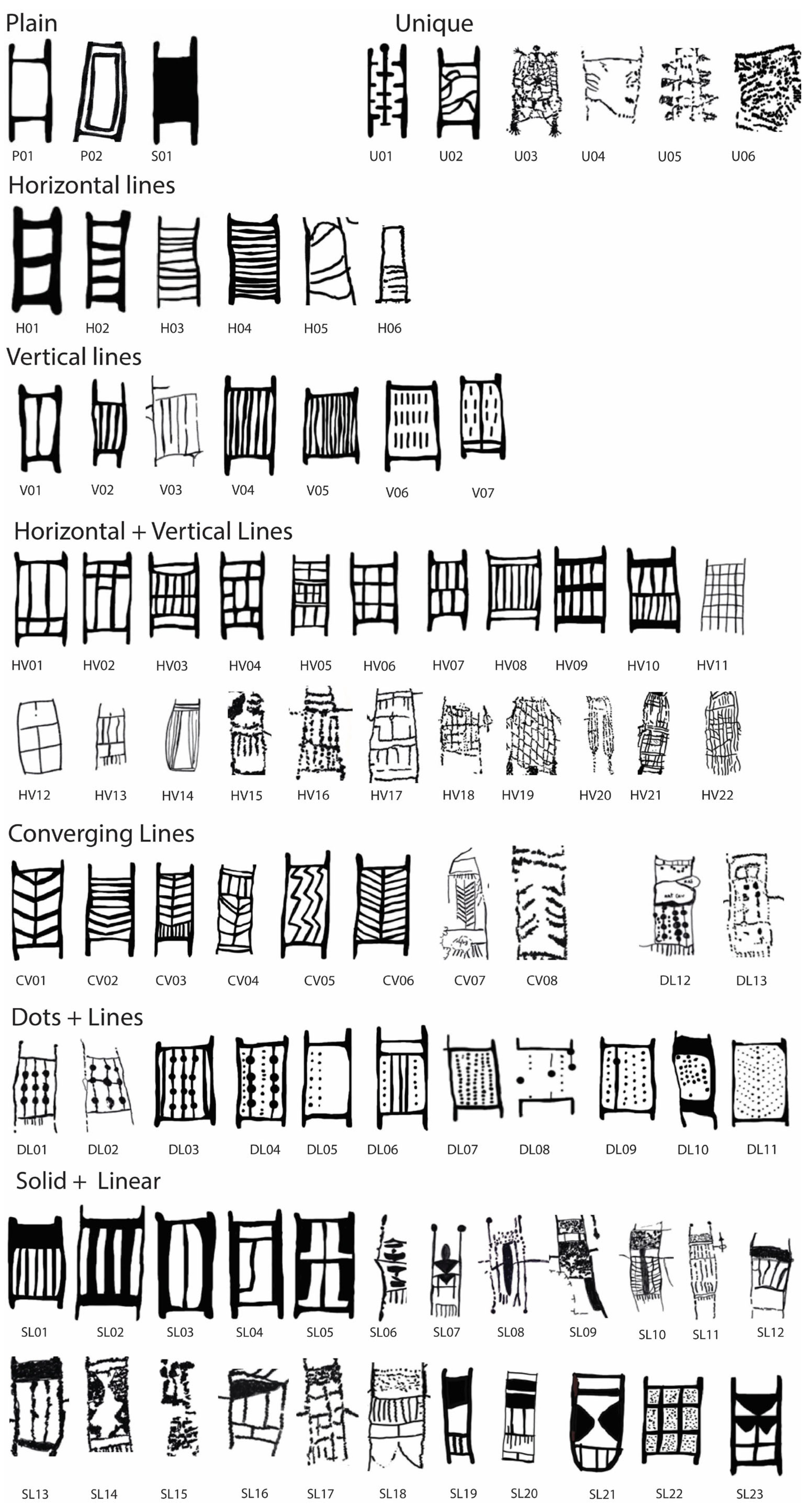

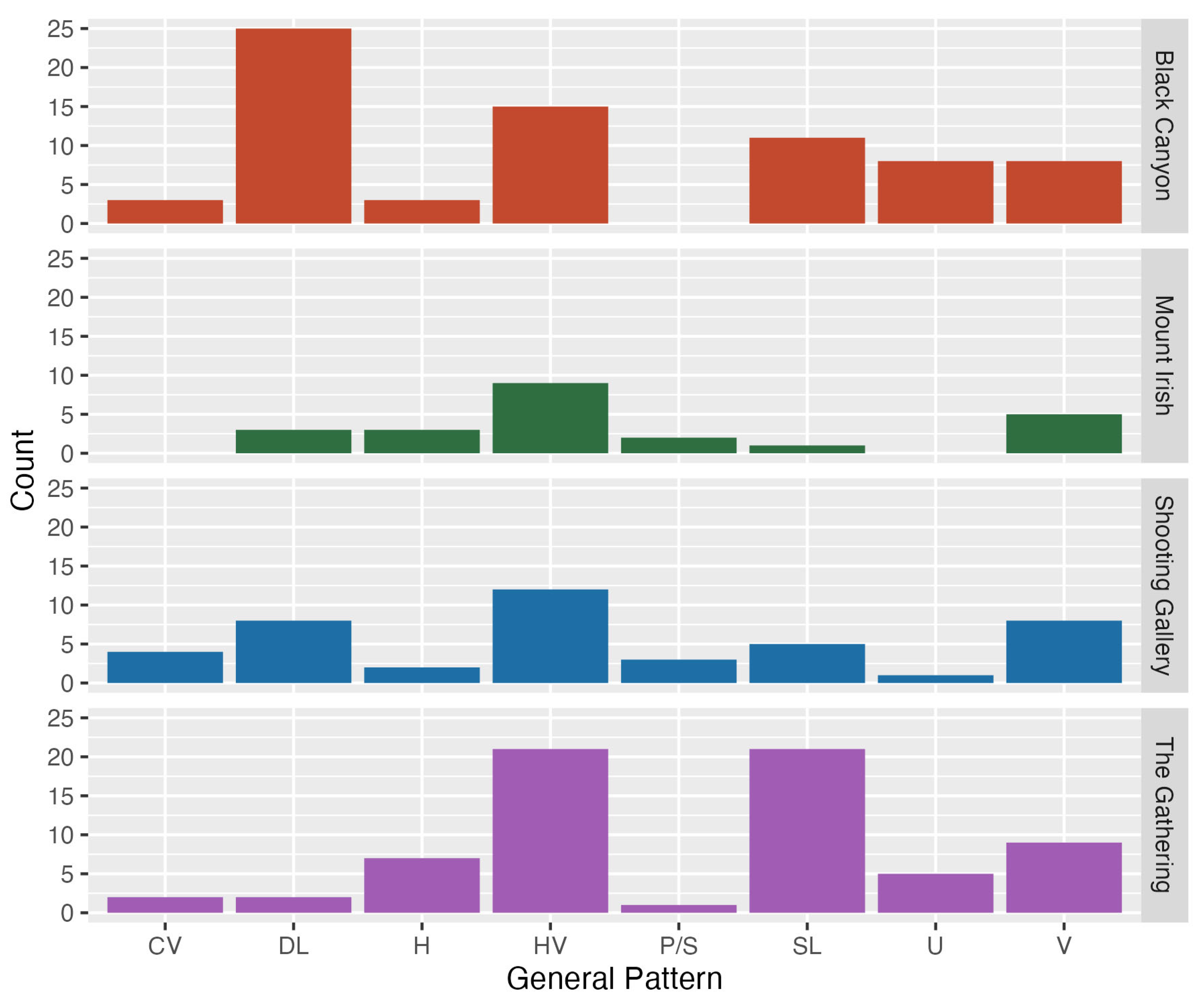

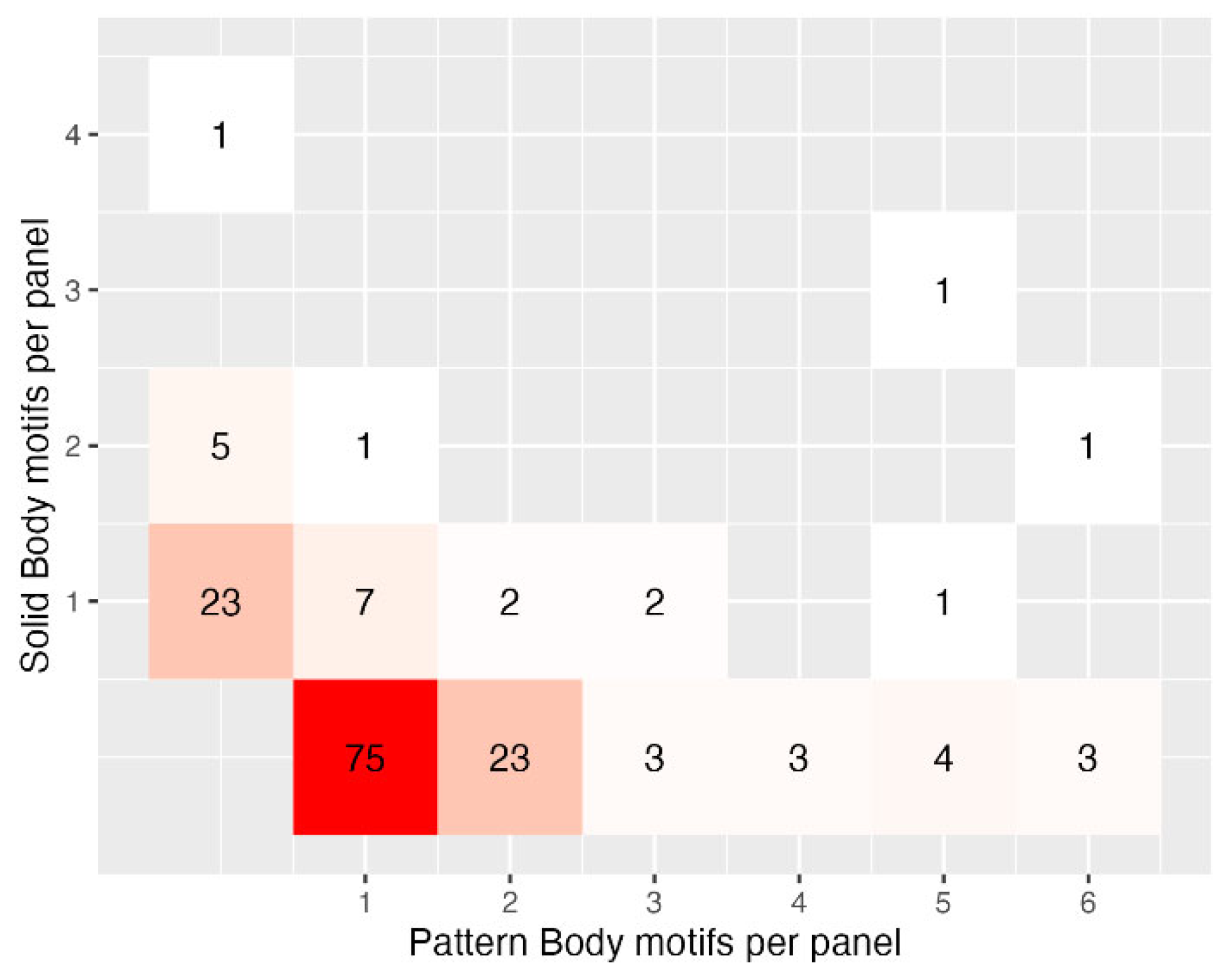

3.4. Pahranagat Patterned-Bodied Anthropomorphs (PBAs)

3.4.1. PBA—Change Through Time

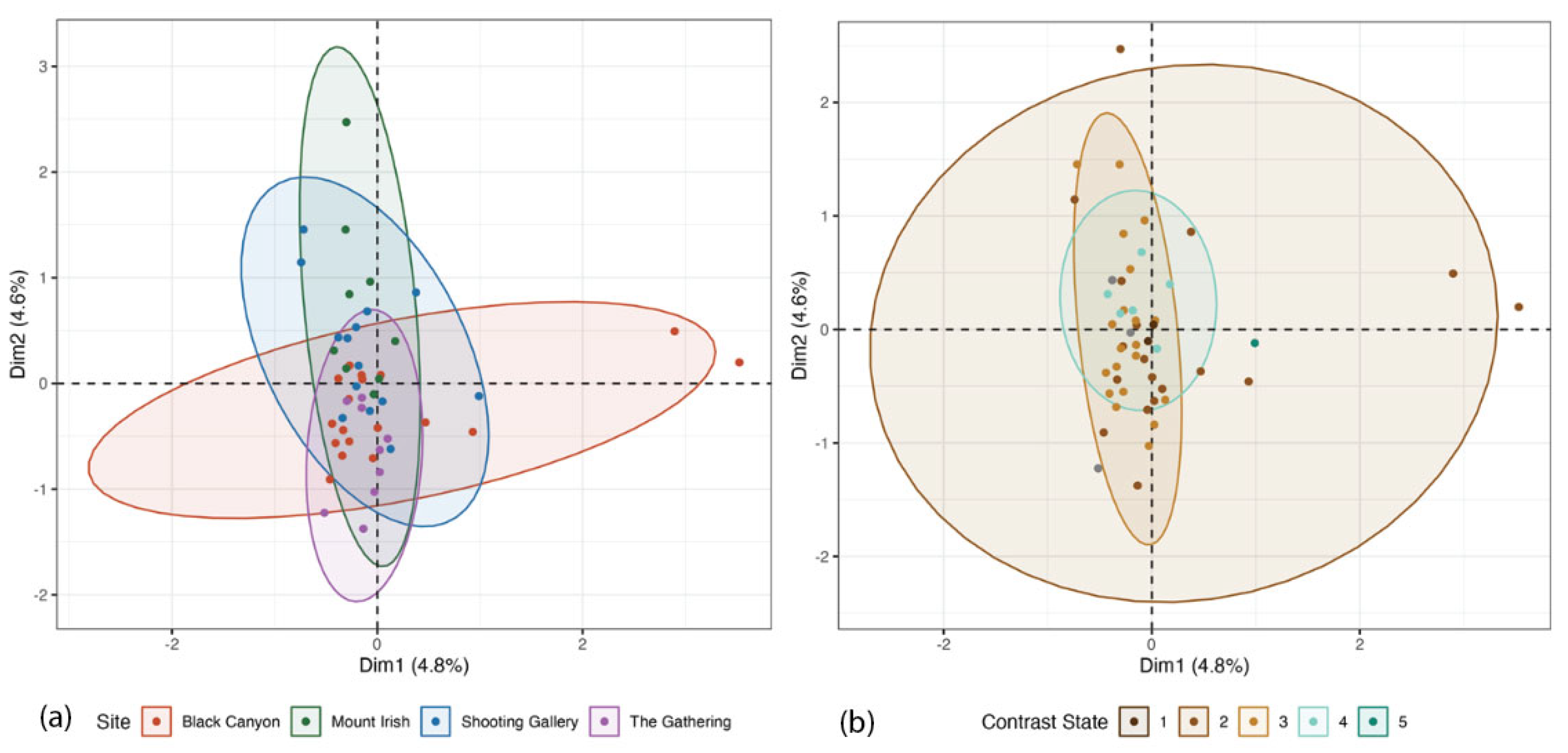

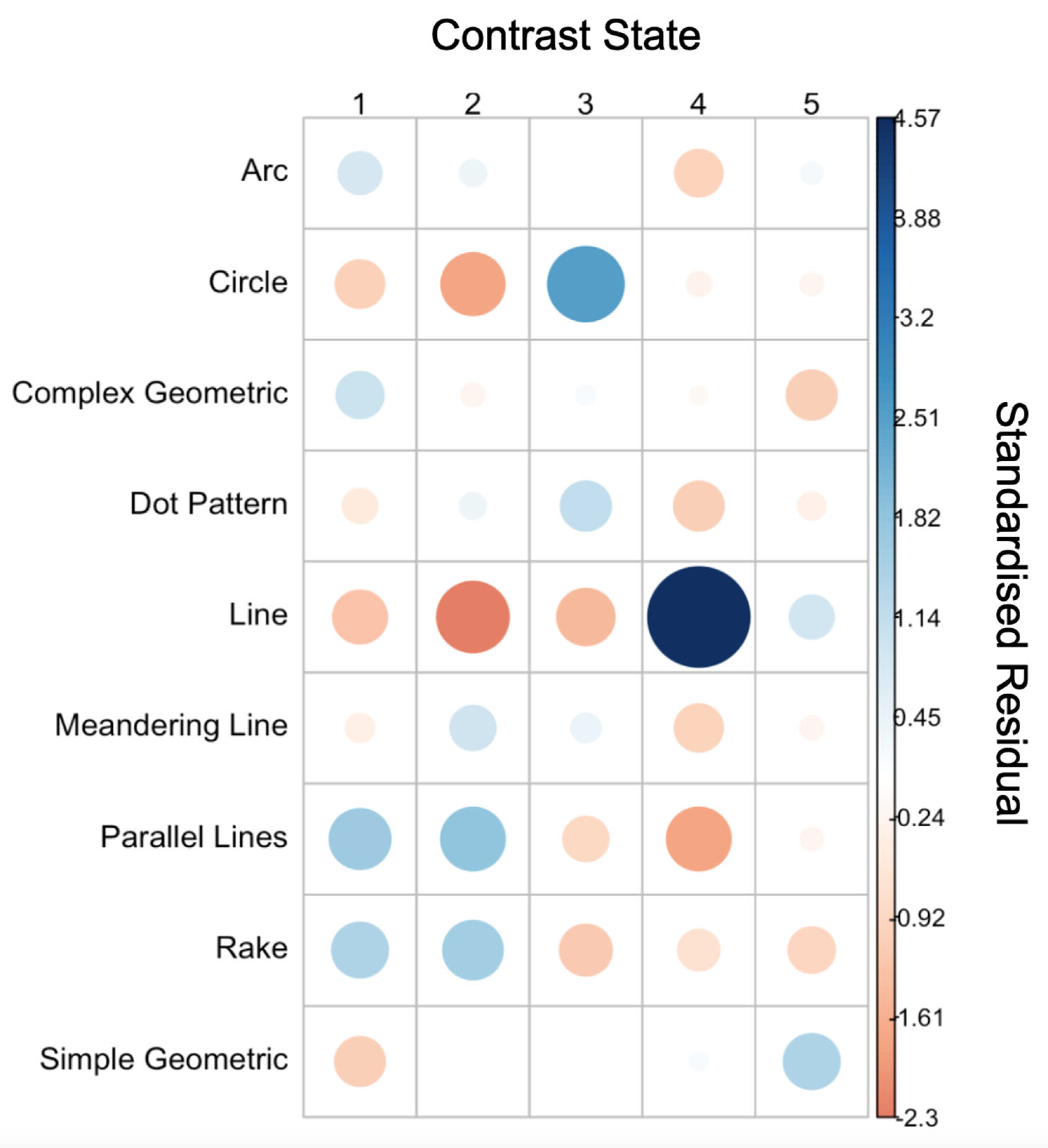

3.4.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

- The PBAs from all four places demonstrated stylistic homogeneity by a strong clustering around the origin (0,0).

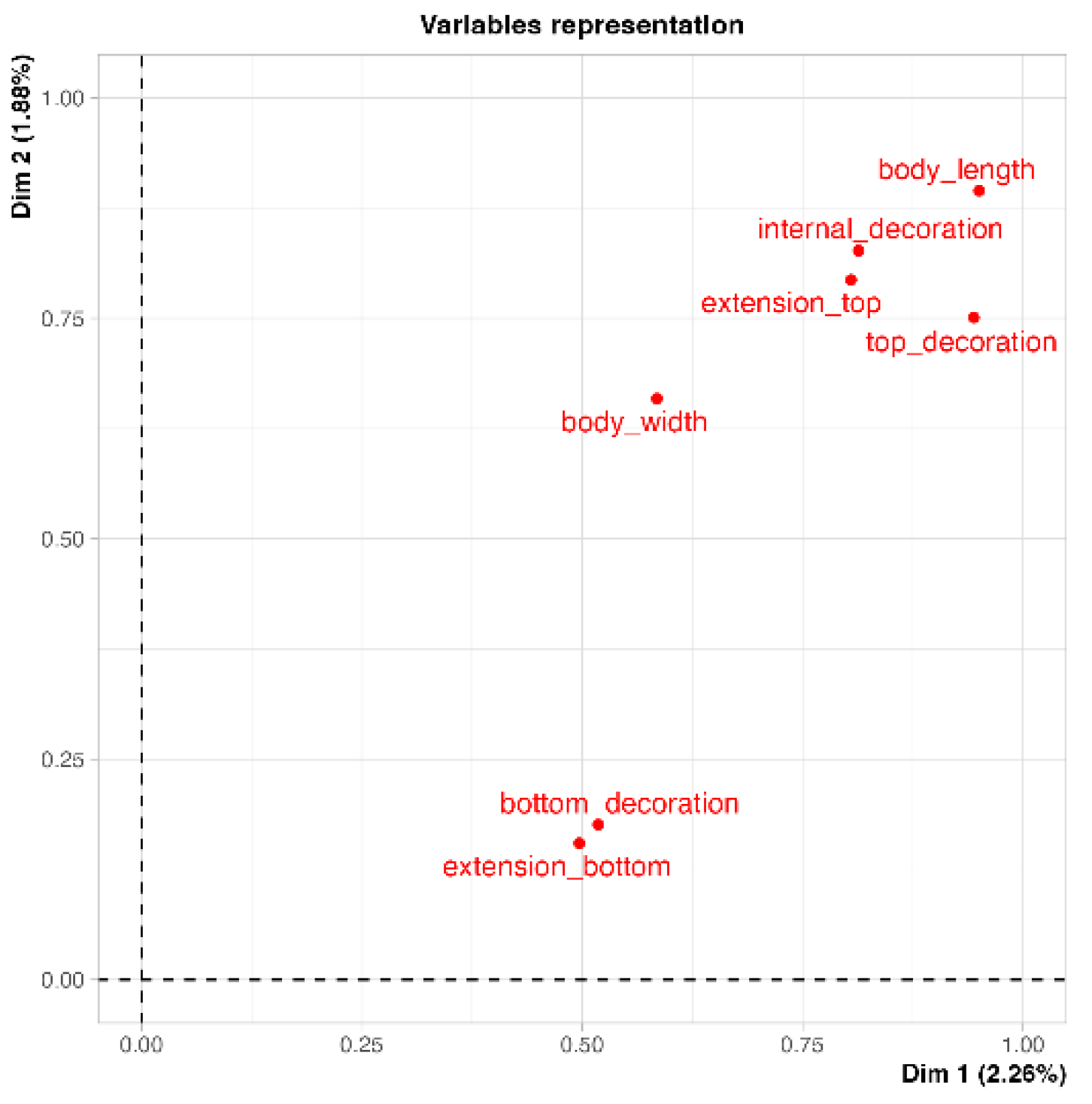

- The attributes that contributed most to variability in these motifs were internal decoration, the top and bottom extensions, and the body length (Figure 20).

- All areas had notable outliers (see Figure 21a), i.e., motifs that were stylistically diverse. The tightest cluster around the origin, signifying greatest homogeneity, was the small Pahroc sample, followed by the Black Canyon assemblage. The Shooting Gallery PBAs were the most stylistically diverse.

- The greatest PBA homogeneity was demonstrated in CS3 (see Figure 21b), while CS4 examples displayed the most heterogeneity.

3.5. Atlatls

| Types | CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | CS4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 14 | |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | |

| A3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| A4 | 13 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| A5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| A6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A8 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A9 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| A10 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| A11 | 2 | 1 | |||

| A13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| A14 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A15 | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||

| A16 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A17 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A18 | 1 | 1 | |||

| A19 | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||

| A20 | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||

| A21 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 2 | 36 | 33 | 10 | 82 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Changing Proportions of Geometric and Representational Classes

4.2. A Partnered Relationship?

4.3. Placement in the Landscape

4.4. The Pahranagat Art Sequence

4.5. Negotiating Multiple Narratives

“In many cases, living cultures are likely to accommodate representations from the past within their present day cosmological and mythological schema”.

“We talk about the little people, the De-ju-gu-oos that are responsible for making [the] original drawings. They were for the powerful people who knew how to read [the markings] and use those and they could grow from there”.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The author recognises that Paiute and Western Shoshone descendent communities of the Great Basin prefer the term “rock writings” to “rock art”. Because this paper refers to human rock markings more broadly, and in a global context where the term is more broadly accepted, I use the terms “rock writings”, “rock art”, petroglyphs, and pictographs interchangeably, and advisedly. |

References

- Balme, Jane, Iain Davidson, Jo McDonald, Nicola Stern, and Peter Veth. 2009. Symbolic behaviour and the peopling of the southern arc route to Australia. Quaternary International 202: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Pat. 2019. What we knew then and what we know now: Thirty years of CRM Archaeology in the Great Basin. In Cultural Resource Management in the Great Basin, 1986–2016. Edited by Alice Baldrica, Patricia A. deBunch and Donald D. Fowler. University of Utah Anthropological Papers # 131. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Larry V., Eugene M. Hattori, John Southon, and Ben Aleck. 2013. Dating North America’s oldest petroglyphs, Winnemucca Lake subbasin, Nevada. Journal of Archaeological Science 40: 4466–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, Robert L. 2015. Orderly Anarchy: Sociopolitical Evolution in Aboriginal California. Oakland: University of California Press, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger, Robert L., Raven Garvey, and Shannon Tushingham. 2015. Hunter-gatherers as optimal foragers. In Hunter-Gatherers: Archaeological and Evolutionary Theory. Edited by Robert L. Bettinger, Raven Garvey and Shannon Tushingham. New York: Springer, pp. 91–138. [Google Scholar]

- Billo, Evelyn, Robert Mark, and Donald E. Weaver. 2013. Sears Point rock art recording Project, Arizona, USA. In IFRAO 2013 Proceedings, American Indian Rock Art. Edited by Mavis Greer and Peggy Whitehead. Orem: American Rock Art Research Association, vol. 40, pp. 1283–302. Available online: http://www.rupestrian.com/Sears_Point_IFRAO2013.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Cannon, William, and Alannah Woody. 2007. Toward a Gender-Inclusive View of Rock Art in the Northern Great Basin. In Great Basin Rock Art: Archaeological Perspectives. Edited by Angus Quinlan. Reno: University of Nevada Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, William J., and Mary F. Ricks. 2007. Contexts in the analysis of rock art: Settlement and rock art in the Warner Valley area, Oregon. In Great Basin Rock Art: Archaeological Perspectives. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press, pp. 107–25. [Google Scholar]

- Clabaugh, P. B., and R. A Clabaugh. 2009. Pahranagat Man: Unusual Anthropomophic Figures Along the Pahranagat Trail, Lincoln County, Nevada.

- Clayton, Lucia. 2021. Contextualising Great Basin Rock Art. A Spatial and Stylistic Analysis of Volcanic Tableland Rock Art. Unpublished. Ph.D. thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Conkey, Margaret. 1980. The Identification of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherer Aggregation Sites: The Case of Altamira. Current Anthropology 21: 609–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Thomas J., Pat Barker, Catherine S. Fowler, Eugene M. Hattori, Dennis L. Jenkins, and William J. Cannon. 2016. Getting Beyond the Point: Textiles of the Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene in the Northwestern Great Basin. American Antiquity 81: 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutouly, Yan Axel Gómez, and Charles. E. Holmes. 2018. The microblade industry from Swan Point Cultural Zone 4b: Technological and cultural implications from the earliest human occupation in Alaska. American Antiquity 83: 735–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, Jerry. 1994. The Piute Creek Petroglyph Inventory: A Rock Art Survey in the East Mojave Desert of California. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 39: 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dillehay, Tom D., Carlos Ocampo, José Saavedra, Andre Oliveira Sawakuchi, Rodrigo M. Vega, Mario Pino, Michael B. Collins, Linda Scott Cummings, Ivan Arregui, Ximema S. Villagran, and et al. 2015. New archaeological evidence for an early human presence at Monte Verde, Chile. PLoS ONE 10: e0141923. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita, and Tommaso Mattioli. 2015. Archaeoacoustics of rock art: Quantitative approaches to the acoustics and soundscape of rock art. In CAA2015. Keep The Revolution Going: Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 1049–58. [Google Scholar]

- Elston, Robert G., David W. Zeanah, and Brian F. Codding. 2014. Living Outside the Box: An Updated Perspective on Diet Breadth and Sexual Division of Labor in the Prearchaic Great Basin. Quaternary International 352: 200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedel, Stuart J. 2025. Petroglyphs Depicting Spearthrowers (atlatls) at Grapevine Canyon, Nevada: Chronological, Culture Historical, and Symbolic Implications. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390630285_PETROGLYPHS_DEPICTING_SPEARTHROWERS_ATLATLS_AT_GRAPEVINE_CANYON_NEVADA_CHRONOLOGICAL_CULTURE_HISTORICAL_AND_SYMBOLIC_IMPLICATIONS?channel=doi&linkId=67f6c6159b1c6c4877856961&showFulltext=true (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Finch, Damien, Andrew Gleadow, Janet Hergt, Pauline Heaney, Helen Green, Cecilia Myers, Peter Veth, Sam Harper, Sven Ouzman, and Vladimir Levchenko. 2021. Ages for Australia’s oldest rock paintings. Nature Human Behaviour 5: 310–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Catherine S. 1995. Some Notes on Ethnographic Subsistence Systems in Mojavean Environments in the Great Basin. Journal of Ethnobiology 15: 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Julie E., and Larry L. Loendorf. 2002. Ancient Visions: Petroglyphs and Pictographs from the Wind River and Bighorn Country, Wyoming and Montana. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Alan P., David A. Young, and Robert M. Yohe, II. 2010. Bighorn hunting, resource depression, and rock art in the Coso Range, eastern California: A computer simulation model. Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, David S., and Harold A. Cahn. 1950. The Petroglyphs of Dinwoody, Wyoming. American Antiquity 15: 219–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambastiani, Mark A., Clint Cole, Leslie Fryman, Angus Quinlan, Penny Rucks, Jo McDonald, and David S. Whitley. 2015. A Cultural Resources Inventory of 33,095 Acres and Rock Art Analysis in the Pahroc Rock Art, Mt. Irish, and Shooting Gallery Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, Lincoln County, Nevada. BLM Report No: 8111 CRR NV 040-12-2015, prepared by ASM Affiliates, Reno, Nevada. Caliente: Bureau of Land Management, Caliente Field Office. [Google Scholar]

- Gilreath, Amy, Ginny Bengston, and Brandon Patterson. 2011. Ethnographic and Archaeological Inventory and Evaluation of Black Canyon, Lincoln County, Nevada Volume 1: Report and Appendices A –F. San Antonio: Henderson. Available online: https://nvarch.org/amcs/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2013-Volume-26-Nevada-Archaeologist.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Gilreath, Amy J., and William R. Hildebrandt. 2008. Coso Rock Art Within Its Archaeological Context. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 28: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gilreath, Amy J., and William R. Hildebrandt. 2012. Current Perspectives on the production and conveyance of Coso Obsidian. In Perspectives on Prehistoric Trade and Exchange in California and the Great Basin. Edited by Richard E. Hughes. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel, Ted, Bryan Hockett, Kenneth D. Adams, David Rhode, and Kelly Graf. 2011. Climate, environment, and humans in North America’s Great Basin during the Younger Dryas, 12,900–11,600 calendar years ago. Quaternary International 242: 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, Ted, Michael R. Waters, and Dennis H. O’Rourke. 2008. The Late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science 319: 1497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Campbell. 1967. Rock Art of the American Indians. New York: Thomas Y Crowell. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Campbell. 1968. Rock Drawings of the Coso Range: Inyo County California. China Lake: Maturango Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Campbell, James Baird, and J. Kenneth Pringle. 1968. Rock Drawings of the Coso Range, China Lake, California. Maturango Museum Publication No. 4. China Lake: Maturango. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer, Robert F., and Martin Baumhoff. 1962. Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer, Robert F., and Thomas R. Hester. 1974. Two Petroglyph Sites in Lincoln County, Nevada. University of California Archaeological Research Facility Contributions 20: 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Elaine, and Anne Carter. 2009. The Dynamic Duo: Superheroes of Pahranagat Rock Art. Utah Rock Art XXVIII: 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, Thomas N., and Frank Lee Earley. 2017. Apishapa rock art and Great Basin shamanism: Power, souls, and pilgrims. Time and Mind 10: 119–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Dennis L., Loren G. Davis, Thomas W. Stafford, Jr., Paula F. Campos, Bryan Hockett, George T. Jones, Linda Scott Cummings, Chad Yost, Thomas J. Connolly, Robert M. Yohe, and et al. 2012. Clovis age Western Stemmed projectile points and human coprolites at the Paisley Caves. Science 337: 223–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, George T., Charlotte Beck, Eric E. Jones, and Richard E. Hughes. 2003. Lithic Source Use and Paleoarchaic Foraging Territories in the Great Basin. American Antiquity 68: 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, George T., Lisa M. Fontes, Rachel A. Horowitz, Charlotte Beck, and David G. Bailey. 2012. Reconsidering Paleoarchaic mobility in the central Great Basin. American Antiquity 77: 351–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, James D., and David S. Whitley. 2006. Sympathetic Magic in Western North American Rock Art. American Antiquity 71: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, James D., and Michelle Klassen. 2001. Plains Indian Rock Art. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis. 1907. The religion of the Indians of California. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 4: 319–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, David M. 2004. Documentation of the Shooting Gallery Game Drive District, Lincoln County, Nevada. Prepared under Ely Field Office Requisition Number NV-043-RQ03-041. Ely: Bureau of Land Management, Ely District. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, David M. 2016. Rock Art East of the Range of Light. Bishop: Learning to Listen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, David. 2012. Rock Art and Shamanism. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Loubser, Jannie. 2024. LCAI Round 13-Graffiti Mitigation and Rock Art Recording at Site 26LN211; Stratum Unlimited Report to BLM, Caliente Office. Unpublished Report Number: 8111 CRR NV 040-23-2330; Caliente: BLM-NV Caliente Field Office.

- Lytle, Farrel, Mannetta Lytle, and Keith Stever. 2010. Dating Black Canyon Petroglyphs by XRF Chemical Analysis, Appendix A. In Ethnographic and Archaeological Inventory and Evaluation of Black Canyon, Lincoln County, Nevada. Edited by Amy Gilreath, Ginny Bengston and Brandon Patterson. Volume 1: Report and Appendices. Unpublished Far Western Anthropological Research Group Report to US Fish and Wildlife Services. [Google Scholar]

- Maddock, Caroline. S. 2015. A Study of the Coso Patterned Body Anthropomorphs. Matuarango Museum Publication No 26. Ridgecrest: Matuarango Press. ISBN 978-0-943041-31-6. [Google Scholar]

- Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo, Michael C. Westaway, Craig Muller, Vitor C. Sousa, Oscar Lao, Isabel Alves, Anders Bergström, Georgios Athanasiadis, Jade Y. Cheng, Jacob E. Crawford, and et al. 2016. A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia. Nature 538: 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Jo. 2008. Dreamtime Superhighway: Sydney Basin Rock Art and Prehistoric Information Exchange. Canberra: ANU E-Press. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo. 2017. Discontinuities in arid zone rock art: Graphic indicators for changing social complexity across space and through time. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 46: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Jo. 2021. Desert rock art: Social geography at the local scale. In Perspectives on Differences in Rock Art. Edited by Jan Magne Gjerde and Marne Arntzen. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing Ltd., pp. 338–59. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, and Ken Mulvaney, eds. 2023. Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming—A Long and Short History of this Cultural Landscape with Reference to Rock Art, Stone Features, Excavations and Historical Sites Recorded Across the Dampier Archipelago Between 2014 and 2018. CRAR+M Monograph Series # 2. Perth: UWAPublishing. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, and Peter Veth. 2013. The archaeology of memory: The recursive relationship of Martu rock art and place. In Anthropological Forum. Abingdon: Routledge, vol. 23, pp. 367–86. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, and Peter Veth, eds. 2012. The social dynamics of aggregation and dispersal in the Western Desert. In A Companion to Rock Art. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Jo, Andrea Catacora, Sarah de Koning, and Emily Middleton. 2016. Digital technologies and quantitative approaches to recording rock art in the Great Basin, USA. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 10: 917–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, Emily S. 2013. Paleoindian Rock Art: An Evaluation of the Antiquity of Great Basin Carved Abstract Rock Art in the Northern Great Basin. Master’s thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, Emily S., Geoffrey M. Smith, William J. Cannon, and Mary F. Ricks. 2014. Paleoindian rock art: Establishing the antiquity of Great Basin Carved Abstract petroglyphs in the northern Great Basin. Journal of Archaeological Science 43: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphy, Howard. 2012. Recursive and Iterative Processes in Australian Rock Art: An Anthropological Perspective. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney, Ken. 2009. Dating the Dreaming: Extinct Fauna in the Petroglyphs of the Pilbara Region, Western Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 44: 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevada Rock Art Foundation. 2018. Rock Art: Ancient Cultural Landscapes of Lincoln County; Reno: Nevada Rock Art Foundation.

- Nye, William. 1886. A winter among the Piutes. Overland Monthly. Second Series 7: 293–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, Evan J., Eugene M. Hattori, Larry V. Benson, John Southon, Hojung Song, and Derek A. Woller. 2022. A 14,100 cal BP rocky mountain locust cache from Winnemucca Lake, Pershing County, Nevada. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 46: 103704. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, Barbara A., Kevin S. Jones, John J. Mecholsky, Gerald Bourne, Richard C. Hulbert, Jr., Bruce J. MacFadden, Krista L. Church, Michael W. Warren, Thomas F. Jorstad, Dennis J. Stanford, and et al. 2011. Earliest art in the Americas: Incised image of a proboscidean on a mineralized extinct animal bone from Vero Beach, Florida. Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 2908–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, Angus. 2012. Rock art. In A Prehistoric Context for Southern Nevada. Edited by Heidi Roberts and Richard Ahlstrom. HRA Archaeological Report No. 11-05. Las Vegas: HRA Conservation Archaeology, pp. 209–36. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, Angus R., and Alannah Woody. 2003. Marks of distinction: Rock art and ethnic identification in the Great Basin. American Antiquity 68: 372–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Eric W., Alannah Woody, and Alan Watchman. 2007. Petroglyph dating on the Massacre Bench. In Great Basin Rock Art: Archaeological Perspectives. Edited by Angus R. Quinlan. Reno: University of Nevada Press, pp. 126–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, Andree. 2002. Rock art as an indicator of changing social geographies in central Australia. In Inscribed Landscapes: Marking and Making Places. Edited by Bruno David and Meredith Wilson. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Timothy B., Thomas W. Stafford, Jr., Daniel C. Fisher, Jan J. Enghild, J. Michael Quigg, Richard A. Ketcham, J. Chris Sagebiel, Romy Hanna, and Matthew W. Colbert. 2022. Human occupation of the North American Colorado Plateau∼ 37,000 years ago. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10: 903795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, James R. 1990. Style and ethnicity in archaeology: The case for isochrestism. In The Uses Of style in Archaeology. Edited by Margaret Conkey and Christine Hastorf. New Directions in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly. 1980. Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. Santa Fe: School of America. [Google Scholar]

- Simms, Steven. 2010. Traces of Fremont: Society and rock art of Ancient Utah. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Geoffrey M. 2010. Footprints Across the Black Rock: Temporal Variability in Prehistoric Foraging Territories and Toolstone Procurement Strategies in the Western Great Basin. American Antiquity 75: 865–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Geoffrey M., and Pat Barker. 2017. The Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene Record in the Northwestern Great Basin: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and How We May Be Wrong. PaleoAmerica 3: 13–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, W. Geoffrey. 1991. Pluvial climatic episodes in North America and North Africa: Types and correlation with global climate. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 84: 217–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, Julian H. 1929. Petroglyphs of California and Adjoining States, Vol. 24. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, and Maria Nieves Zedeño. 2001. Historical memory and ethnographic perspectives on the Southern Paiute homeland. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 23: 229–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Alannah Bell, and Bianca Eguino Uribe. 2024. Storied Rocks: Portals to Other Dimensions. Arts 13: 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Hannah Z. Johnson, Phillip T. Dukes, Stephanie C. De Sola, and Kristen L. Simmons. 2011a. Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Delamar Valley Solar Energy Zone. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Hannah Z. Johnson, Phillip T. Dukes, Stephanie C. De Sola, and Kirsten L. Simmons. 2011b. Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed East Mormon Mountain Valley Solar Energy Zone. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Richard Arnold, and Kathleen Van Vlack. 2022. Landscape Is Alive: Nuwuvi Pilgrimage and Power Places in Nevada. Land 11: 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, David Hurst. 2019. A shoshonean prayerstone hypothesis: Ritual cartographies of Great Basin incised stones. American Antiquity 84: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, David Hurst, and Constance I. Millar. 2024. Pinyon pine and people progressing simultaneously across the Great Basin: Coincidence? Causality? Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 44: 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, David Hurst, Donna Cossette, Misty Benner, Anna Camp, and Erick Robinson. 2025. Spirit Cave Resilience: How Do We Explain a 10,000-Year Continuity? American Antiquity, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschanz, C. M., and E. H. Pampeyan. 1970. Geology and mineral deposits of Lincoln County, Nevada: Nevada Bur. Mines Bulletin 73: 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Christy G. 1963. Petroglyphs of the Glen Canyon Region: Style, chronology, distribution, and relationships from Basketmaker to Navajo. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 38. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- U.S Fish and Wildlife Services. 2009. Desert National Wildlife Refuge Complex Ash Meadows, Desert, Moapa Valley, and Pahranagat National Wildlife Refuges: Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement. Volume 1; Report held by U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Southwest Region. Washington, DC: U.S Fish and Wildlife Services.

- Veth, Peter, Nicola Stern, Jo McDonald, Jane Balme, and Iain Davidson. 2011. The role of information exchange in the colonisation of Sahul. In Information and Its Role in Hunter-Gatherer Bands. Edited by Robert Whallen, William. A. Lovis and Robert. K. Hitchcock. Los Angelas: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, pp. 203–20. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Deward. 1991. Protection of American Indian Sacred Geography. In Handbook of American Indian Religious Freedom. Edited by C. Vecsey. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, pp. 100–15. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, Stephen J. 2010. Voices Carry: Whisper Galleries and X-rated Echo Myths of Utah. Utah Rock Art 29: 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, Michael R. 2019. Late Pleistocene exploration and settlement of the Americas by modern humans. Science 365: eaat5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernecke, D. Clark, and Michael B. Collins. 2012. Patterns and Process: Some Thoughts on the Incised Stones from the Gault Site, Central Texas, United States. In L’Art Pléistocène dans le Monde: Actes du Congres IFRAO 2010. Edited by Jean Clottes. Tarascon sur Ariège: Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés: Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées, LXV–LXVI, 2010–2011. pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, William G. 2013. Pahranagat Representational Style: A unique rock art tradition in and surrounding the Pahranagat Valley, Lincoln County, Nevada. Nevada Archaeologist 26: 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- White, William G., and Rebecca L. Orndorff. 1999. A Cultural Resource and Geological Study Pertaining to Four Selected Petroglyph/Pictograph sites on Nellis Air Force Range and Adjacent Overflight Lands, Lincoln and NYE Counties, Nevada. Report to US Army Corps of Engineers Fort Worth District. Las Vegas: Harry Reid Centre of Environmental Studies, Marjorie Barrack Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 1992. Shamanism and Rock Art in Far Western North America. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 1994. By the Hunter, for the Gatherer: Art, Social Relations and Subsistence Change in the Prehistoric Great Basin. World Archaeology 25: 356–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2000. The Art of the Shaman: Rock Art of California. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2012. In Suspect Terrain: Dating rock art. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. Malden: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 605–24. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2013. Rock Art Dating and the Peopling of the Americas. Journal of Archaeology 2013: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2015. North American Rock Art Perspective. In A Cultural Resources Inventory of 33,095 Acres and Rock Art Analysis in the Pahroc Rock Art, Mt. Irish, and Shooting Gallery Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, Lincoln County, Nevada. Edited by Mark A. Giambastiani. BLM Report No: 8111 CRR NV 040-12-2015, prepared by ASM Affiliates, Reno, Nevada. Caliente: Bureau of Land Management, Caliente Field Office, pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2019. Early Northern Plains Rock Art in Context. In Dinwoody Dissected: Looking at the Interrelationships Between Central Wyoming Petroglyphs. Edited by Danny Walker. Laramie: Wyoming Archaeological Society, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2021. Rock art, shamanism, and the ontological turn. In Ontologies of Rock Art. Edited by Oscar Moro Abadia and Martin Porr. New York: Routledge, pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S., and Ronald I. Dorn. 2010. The Coso Petroglyph Chronology. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 43: 135–57. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S., J. D. Lancaster, and Andrea Catacora. 2025. Beyond Correlation to Causation in Hunter–Gatherer Ritual Landscapes: Testing an Ontological Model of Site Locations in the Mojave Desert, California. Arts 14: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S., Ronald I. Dorn, Joseph M. Simon, Robert Rechtman, and Tamara K. Whitley. 1999. Sally’s Rockshelter and the Archaeology of the Vision Quest. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9: 221–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiessner, Polly. 1983. Style and social information in Kalahari San projectile points. American Antiquity 48: 253–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiessner, Polly. 1984. Reconsidering the behavioral basis for style: A case study among the Kalahari San. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 3: 190–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigand, Peter E. 2002. Middle to late Holocene Climate and Vegetation Dynamics in the Northwestern Mohave Desert as Revealed in Pollen and Macro fossils from Ancient Woodrat Middens. Unpublished Technical Report. Reno: Great Basin & Mojave Palaeoenvironmental Research & Consulting, vol. 48, Academia.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Wigand, Peter E., and David Rhode. 2002. Great Basin vegetation history and aquatic systems: The last 150,000 years. Great Basin Aquatic Systems History. Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences 33: 309–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wobst, H. Martin. 1977. Stylistic behaviour and information exchange. In For the Director: Research Essays in Honour of JB Griffen. Edited by Charles E. Cleland. No 61. Ann Arbor: Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, pp. 317–42. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, Alanah J. 1997. Layer by Layer: A Multigenerational Analysis of the Massacre Lake Rock Art Site (Nevada). Mater’s thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Class | Mount Irish | Shooting Gallery | Pahroc | Total | %f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropomorphic | 212 | 292 | 28 | 532 | 7.8 |

| Geometric | 1800 | 1908 | 158 | 3866 | 57.0 |

| Material Culture | 13 | 29 | 1 | 43 | 0.6 |

| Other | 254 | 173 | 18 | 445 | 6.6 |

| Tracks | 22 | 57 | 4 | 83 | 1.2 |

| Zoomorphic | 722 | 1053 | 39 | 1814 | 26.7 |

| Total | 3023 | 3512 | 248 | 6783 | 100 |

| Design | Black Canyon | Mount Irish | Shooting Gallery | The Gathering | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HV—Horizontal + Vertical | 15 | 9 | 12 | 21 | 57 |

| SL—Solid + Linear | 12 | 1 | 5 | 21 | 39 |

| DL—Dots + Linear | 25 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 38 |

| V—Vertical lines | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 30 |

| H—Horizontal lines | 3 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 15 |

| U—Unusual/irregular | 8 | 1 | 5 | 14 | |

| CV—Converging lines | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | |

| S—Plain (solid) | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||

| P—Plain (empty) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 74 | 23 | 43 | 68 | 208 |

| PBA Associations | Total | % | SB Associations | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 179 | 84.4 | N | 31 | 54.4 |

| 1BHS | 19 | 9.0 | 1BHS | 14 | 24.6 |

| 2BHS | 3 | 1.4 | 2BHS | 1 | 1.8 |

| 3BHS | 4 | 1.9 | SB, 3BHS | 2 | 3.5 |

| 4BHS | 3 | 1.4 | |||

| Total | 208 | 100.0 | Total | 57 | 84.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McDonald, J. Signalling and Mobility: Understanding Stylistic Diversity in the Rock Art of a Great Basin Cultural Landscape. Arts 2025, 14, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030064

McDonald J. Signalling and Mobility: Understanding Stylistic Diversity in the Rock Art of a Great Basin Cultural Landscape. Arts. 2025; 14(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcDonald, Jo. 2025. "Signalling and Mobility: Understanding Stylistic Diversity in the Rock Art of a Great Basin Cultural Landscape" Arts 14, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030064

APA StyleMcDonald, J. (2025). Signalling and Mobility: Understanding Stylistic Diversity in the Rock Art of a Great Basin Cultural Landscape. Arts, 14(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030064