1. Introduction

“The work of art is reflected on the surface of consciousness. It sits outside of us, and its image evaporates without trace as soon as the action ceases. (…) The hustle and bustle of the street, constantly changing in intensity and tempo, draws us into its vortex … penetrating deep into the work of art, experiencing its inner pulsation actively and with all our senses.”

For several decades, we have been witnessing a new trend: we have been taking part in the successive transformations of art; just as artists at the end of the 19th century decided to revolutionize the concept of work and creative creation, they decided to leave their stuffy and often gloomy studios and work outdoors in direct contact with nature. Everything that is painted directly on the spot, the Impressionists claimed, always has force and power, a momentum that can never be achieved in the studio (

Perruchot 1982).

Today, artists are increasingly daring to go outside, take the context of the image into public space, and realize their large-scale and multi-dimensional works. These artifacts, which become the property of all, offer the average viewer the possibility of direct contact with high art. This is a very interesting and fascinating phenomenon, undoubtedly linked to the growing awareness and perceptual visualization of societies worldwide. Murals naturally enter urban spaces, the existential environment of people of different generations, the child, the young, and the old, and often people with different views and experiences. These paintings, signs of the present, mini-stories, automatically penetrate the consciousness, the minds, and often the hearts of passersby, marking, for some, a path of reflection, inspiration, or personal development. Thanks to their visibility and accessibility, murals are becoming not only an aesthetic complement to architecture but also a tool for social dialog, a carrier of cultural identity, and a catalyst for spatial change. Examples of artists such as Banksy, whose works can instantly change the indifferent hearts of viewers, show that mural art can not only be an aesthetic manifesto but also a profound social and cultural commentary. It is in this ability to convey universal, multi-layered content that the power of murals lies, which not only resonates in the present but also sets directions for the future of sociocultural change.

We draw attention to a gap in scholarly reflection on the evolving relationship between mural painting and the architectural or spatial contexts in which it has been created from prehistoric caves to contemporary cityscapes. Despite the rich history of this phenomenon, little attention has been paid to how thematic and stylistic changes in mural art affect architecture or how architecture shapes the reception of these works. As a form of public art, contemporary murals influence not only the aesthetics of buildings and urban spaces but also the identity of a place, social interactions, and the experience of a space by its users.

To address this gap, this article situates mural painting within a broader historical and cultural continuum, emphasizing its evolving relationship with its surroundings. The aim is to analyze the historical evolution of mural painting as a medium that simultaneously reflects and shapes cultural values, society, political ideologies, and collective memory. From its ritual and symbolic origins to its contemporary role in public discourse and urban resistance, mural painting has undergone significant transformations that have revealed the shifting dynamics between image, space, and society. The central research questions that guide this investigation are as follows: How has mural painting evolved across civilizations in relation to techniques, symbolism, and social functions, and how does it reflect broader civilizational transformations over time?

To answer these questions, this article adopts an interdisciplinary and diachronic approach that traces the development of mural paintings from prehistory to the present. The structure of this article follows a chronological trajectory, with each major historical period discussed through emblematic examples. In each case, the analysis focuses on four dimensions: the technical approach employed by the creators of murals, the symbolic content of the imagery; the social and political context of its production and reception; and the civilizational values reflected in its visual language. Through these considerations, this article not only enriches the academic discourse on mural painting but also contributes to the debate on the possibilities of its use in the design of public spaces and the formation of urban cultural identities. By combining a historical perspective with an analysis of contemporary practices, the text opens new fields of reflection on the role of murals in the architectural and social contexts of contemporary cities.

2. Methodology

This research was carried out using an interdisciplinary approach, combining perspectives and classical methods from art, architecture, and urban studies. Such a diverse approach allows for the analysis of murals as artistic and social phenomena operating at the interface of different scientific disciplines. The methodological basis was a review of the literature, including historical sources and contemporary publications on murals and their techniques, materials, and social significance. The review of the literature helped place the phenomenon under study in a broader historical and civilizational context. The second key element was a visual and spatial analysis, focusing on selected murals from different periods and regions. This analysis revealed the technical and aesthetic diversity of these works and their relationship with the surrounding space, underscoring how murals both shape and are shaped by the architectural and social environments in which they are embedded.

Another important methodological element was the observation and analysis of the case studies. The case studies allowed us to capture the relationship between the mural and its sociocultural context, exploring how these works convey values, ideas, and emotions to local communities. This study considered the diversity of murals in terms of their construction techniques, functions, and locations. Attention was also paid to the relationship between murals and architecture, exploring how murals integrate into the surroundings and influence the way in which they are perceived by its users. The selection of the examples analyzed was based on their artistic significance. The methods used in this study, based on qualitative analysis, aimed to capture the complex nature of murals as a form of artistic expression and their role in shaping aesthetics and identity.

Integral to the methodology was a reflexive approach that incorporated rhetorical questions and subjective analysis in the spirit of art philosophy. In the case of art, a fully objective account is impossible, and the researcher’s reflection becomes a natural part of the analytical process. Therefore, this article deliberately avoids a certain parameterization of the phenomenon of mural painting as a metaphysical and subjective phenomenon, defying strict classification.

3. Mural—Definitions and Execution Techniques

Mural comes from the Latin word “murus” meaning wall (

Wiktionary 2025). It is any work of art, often a panoramic composition painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling, or other solid surface, flat, concave, or convex. A mural can be likened to a large canvas on which a craftsman or artist creates his vision. This analogy emphasizes the monumental nature of murals, which often cover building walls. Unlike traditional canvases, murals offer artists an extraordinary space for expression, allowing them to create works of impressive scale and impact (

Austin 2010). Creating a mural resembles painting on a canvas but requires adapting the concept to the architectural context and the wall’s shape and texture (

Liu et al. 2023).

Among the various techniques used in mural painting, the fresco occupies a prominent place because of its antiquity and technical complexity. Frescoes are one of the oldest forms of art, dating back to the second millennium BC (

Jiménez-Desmond et al. 2024). Fresco (buon fresco) or “on fresh plaster” is considered one of the most demanding painting techniques, as it does not allow for any corrections. The essence and complexity of the buon fresco lies not only on the surface of the wall but also within its structure, where a chemical process takes place during painting and drying. The binding agent of the pigment is calcium carbonate, which forms when the wet lime plaster reacts with air (carbonation). Therefore, fresco painting requires a freshly applied plaster that is usable for only a limited time, typically one working day. This daily working area is known as a giornata (Italian for “day”), and its size depends on the complexity of the composition, the painter’s speed and skill, and local environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity.

Fresco paintings must be executed without correction or retouching. The work proceeds systematically, from top to bottom and usually for practical reasons, from left to right. Before painting begins, the artist prepares a full-scale design (cartoon), which is transferred onto the wall using a square grid or a pouncing technique (spolvero). In this method, the outline of the composition is perforated with small holes, and charcoal powder is dusted through them to leave dotted contour lines on the surface of the fresh plaster.

Several preparatory stages must precede the application of the pigments. These include snapping chalk lines (tracciatura) to establish guides and geometry, applying a rough plaster underlayer known as arricio (a mixture of slaked lime, coarse sand, and water) and sketching the composition using a red earth pigment known as sinopia (

Basile 1993). Sinopia was a preparatory sketch made with red earth pigment directly on the rough plaster layer (arricio), commonly used in 15th and 16th century Italian mural painting. It served to outline the composition before applying the final image to a fresh intonaco. This stage was essential for planning proportions, figures, and narrative flow within the fresco technique (

Britannica 2025).

The final image is executed on the smoothest layer of the plaster, called the intonaco. This plaster, composed of slaked lime, fine sand, and marble dust, must be fresh each day, precisely to the portion to be painted. Pigments, which are usually earth-based and are mixed with only water, are applied directly onto the intonaco. As the plaster sets, the pigment becomes chemically bound to the surface of the wall, creating a durable and matte finish integral to the architecture. Buon fresco is considered one of the most demanding painting techniques, requiring exceptional concentration, speed, and planning, as well as deep familiarity with material behavior. Its durability and chromatic subtlety have made it one of the most respected mural techniques in history.

Owing to the nature of the wet plaster and the speed of the carbonation process, a fresco painter (frescante) must work quickly and efficiently to complete the planned section (giornata) before the surface begins to dry. An additional challenge lies in the behavior of pigments: some become lighter as they dry, while others darken or shift in hue. The choice of colors is strictly limited to pigments that are resistant to the alkaline environment of lime-based plasters. Mistakes in the selection or timing of pigments can result in undesirable chemical reactions. For example, an orpiment (bright yellow) can turn black when in contact with lime. Pigments must also be carefully combined, as they can chemically interact with each other. Some, such as ultramarine, derived from the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli mined in the Kokcha Valley of present-day Afghanistan, were extremely expensive and prone to fading or graying over time when applied too thinly (

Rościecha-Kanownik and Martyka 2023).

Because fresco painting does not allow corrections, details and fine elements were often added after the plaster had dried using alternative techniques, such as secco or mezzo-fresco. In the secco method, the retouching (sovradipinture) was performed on a dry plaster using pigments mixed with organic binders (e.g., egg yolk, casein, and glue). The mezzo-fresco technique involved reactivating the carbonation process by applying pigments mixed with slaked lime or limewater commonly referred to as “lime painting” (

Mora et al. 1999;

Piovesan et al. 2012).

After all the decorative elements had been completed, the painted surface was polished (politiones) to compact the pigment layers and enhance luminosity. According to Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder (

Pliny the Elder 1952;

Vitruvius 2001), walls painted with costly vermilion (cinnabar) pigments are sometimes subjected to waxing treatments to preserve and intensify color. For many years, such descriptions led scholars to theorize that ancient wall paintings may have been encaustic, though this remains debated (

Schiavi 1957–1958).

The earliest systematic accounts of mural painting, especially the fresco technique, are found in the works of Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder, whose treatises remain essential sources for the study of ancient visual culture and wall decoration. In “The Ten Books on Architecture” (Book VII) (

Vitruvius 2001), Vitruvius provides one of the first systematic descriptions of mural painting techniques, lime-based plasters, and mineral pigments, all intended to ensure the durability, smoothness, and aesthetic value of interior decoration. He outlines a multilayered plastering system, beginning with a rough base layer made of slaked lime and river sand, applied in three successive coats known as arricio. This is followed by two finer coats composed of lime mixed with powdered marble, which serve to lighten and smooth the surface of the wall. The final thin layer of intonaco is applied immediately before painting, while still wet, to allow for the execution of the true fresco (buon fresco).

Vitruvius distinguishes between these two primary mural techniques. The first is fresco, where pigments are applied to wet plaster and chemically bind during the lime carbonation process, ensuring the longevity of the image. The second is secco, in which pigments are applied to a dry surface using organic binders such as egg yolk or casein. Although it is easier to work with and modify, this technique produces less durable results. Vitruvius classifies pigments according to their origin. Natural pigments include red and yellow ochre, green malachite, and charcoal. Artificial pigments include vermilion (cinnabar), Egyptian blue, and Tyrian purple, which are prized not only for their brilliance but also for their symbolic and economic value.

In “Natural History” (Book XXXV), Pliny the Elder (

Pliny the Elder 1952) presents painting as one of the oldest and most refined arts, tracing its roots to Egypt and Greece. He discusses the evolution of figurative, landscape, architectural, and illusionistic paintings, identifying stylistic trends over centuries. Pliny describes two main tendencies in Roman wall painting: one moving from rigid realism towards decorative stylization, and the other characterized by fantastic, ornamental motifs, which he criticizes as a sign of cultural decadence. Although less focused on techniques than Vitruvius, Pliny emphasizes the importance of various binders, including egg yolk, milk, and wax, and refers to three painting methods: fresco, secco, and encaustic painting, a wax-based technique. He also distinguishes between precious pigments (pretiosa), such as cinnabar, Tyrian purple, azure, lapis lazuli, and indigo, and more common materials, such as ochre, malachite green, charcoal, and soot. Pliny’s account provides valuable information on the technical, economic, and cultural dimensions of Roman mural paintings. His observations complement Vitruvius’ architectural perspective by highlighting shifts in aesthetic taste, the symbolic use of materials, and the social hierarchy embedded in color and technique from the Republican era to the height of the empire.

The historical development of mural paintings, from ancient fresco to Renaissance wall decoration, laid the foundation for their enduring presence in architectural space. However, the modern era has seen a radical transformation of both materials and meanings associated with mural art. Contemporary murals often become an integral part of the urban landscape, entering into dialog with the surrounding space and its inhabitants (

Park and Kovacs 2020). In this way, murals not only beautify the city but can also convey important social or cultural messages (

Lewis 2003) becoming a form of public artistic expression accessible to a wide audience. In contrast to classical fresco paintings, which emphasize permanence and craftsmanship, modern muralism embraces diverse materials and ephemeral forms of expression. A key feature of murals is their visibility and accessibility, as the mural communicates with the public and becomes part of the urban fabric in direct contact with passersby. The mural often becomes a landmark in the city, creating a unique atmosphere. This shift is also visible in technical practices. Contemporary mural techniques have evolved considerably, including traditional and contemporary materials and methods. Contemporary muralists often use acrylic paint, as exemplified by Keith Haring’s Tuttomondo’s mural in Pisa from 1989. However, the materials used can vary considerably, as can be seen in another of Haring’s murals in Melbourne, which used a mixture of alkyd, vinyl, and acrylic resins (

La Nasa et al. 2021).

Although early muralists aimed at longevity, contemporary murals often use synthetic resins as binders for paint, one of the main classes of modern materials, but the durability of these materials is rarely a priority for artists. The choice of specific paints and binders is more likely to be driven by personal preferences and spontaneous creative decisions than by the intention that the work will survive for centuries. It is not uncommon for traditional painting materials to succumb or combine with building products that were originally intended for different purposes (

La Nasa et al. 2016).

The evolution of muralism naturally led to the emergence of street art, a form of public visual expression that often operates outside institutional or commercial frameworks. Street art, also known as urban art, is a form of artistic or visual expression that occurs in public urban spaces. It is a creative practice that extends beyond the walls of galleries and museums, turning streets into open-air exhibitions (

Yan et al. 2019). This form of art has moved from large canvases to building façades, sidewalks, viaducts, and post-industrial environments. Street art is typically informal and often temporary and seeks to communicate directly with a broad audience. Unlike conventional muralism, street art is often anonymous, with artists operating under pseudonyms. It encompasses a variety of techniques including graffiti, stencil art, paste-ups, installations, sculptures, and mosaics. It frequently includes a social or political message that offers critical commentary on systems of power, consumerism, or social norms. Their ephemeral nature means that these works are often painted over, damaged, or removed shortly after their creation. The technical and conceptual openness of street art reflects a broader shift in how urban spaces are used as a canvas for cultural dialog and contestation. This transformation marks a key moment in the history of muralism, when the wall no longer serves only as a medium of permanence but also as a site of negotiation, dissent, and visibility.

Graffiti is considered one of the earliest forms of street art. Etymologically, the term derives from the Greek word gráphein, which means “to write”. In antiquity, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans carved inscriptions on rocks, monuments, tombs, and statues that took various forms and messages, unlike contemporary graffiti. Some recorded personal names, petitions to deities, trade inventories, or notes from civic gatherings, while others simply marked the presence or identity of sacred or commercial structures (

Rosenmeyer 2018). Modern graffiti culture reemerged in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in New York City, where it became a form of self-expression among marginalized urban youth. Initially acting as a way to mark territory by individuals or groups, graffiti quickly spread to subway trains and public transport, transforming cars into mobile canvases. As its visibility increased, local authorities began to classify it as a vandal and criminalized its practice. Graffiti art has been actively developed in Europe since the 1980s. A notable example is the Berlin Wall, particularly its western side, which has become a site for powerful political and artistic expression. After the wall collapse, the segments were preserved and transformed into an open-air gallery by 118 international artists. With the gradual entry of professional artists into the subculture of street art, graffiti has evolved beyond territorial tagging. It has gained aesthetic sophistication, symbolic depth, and artistic legitimacy, becoming a recognized medium for urban visual culture (

Cercleux 2022).

4. The Evolution of Mural Painting

4.1. Prehistoric Mural Painting: Symbols, Rituals, and the Origins of Visual Culture

It is through prehistoric murals that we have invaluable knowledge of our history and of our predecessors and ancestors, giving us a rich picture of our diversity. The history of pictorial art opens up questions that allow us to examine art and prehistoric craftsmen and to penetrate their world of beauty, symbolism, and vision. Discovered in 1994 in the Ardèche region of southern France, Chauvet Grotto contains some of the oldest and most advanced cave paintings known to humans. Dating around 33,000 years ago, they are much older than the famous paintings of Lascaux or Altamira. This discovery has changed our understanding of the origins of art, proving that even in the distant past, humans were able to create realistic compositions using perspective and chiaroscuro. This demonstrates a high level of symbolic thinking and the existence of an artistic tradition in hunter–gatherer communities much earlier than previously thought (

Valladas et al. 2001).

The heyday of Paleolithic painting was the Magdalenian period, which lasted from 16,000 to 8000 BC. During this period, there was a significant development of caves and portable art, particularly in the Cantabrian region of northern Spain and southern France. It is interesting to note that although most of the known sites of cave art are concentrated in the Cantabrian region, many new sites have been discovered in recent years in other parts of the Iberian Peninsula, including Aragon, the Levant, Andalusia, and Portugal (

Bicho et al. 2007).

Despite limited resources, prehistoric mural artists have developed a range of techniques adapted to their natural environment. The pigments were derived from natural minerals, such as red and yellow ochre, manganese dioxide, and charcoal mixed with animal fat, saliva, or water to create rudimentary paint. Painting tools included sticks, moss, hollowed bones for blowing pigment (a precursor of the airbrush), or fingers. The surfaces of the cave walls, whether flat, concave, or textured, were carefully chosen to enhance the visual impact of the figures. These methods allow creators to render animals with remarkable vitality by utilizing shading, contouring and perspective (

Siddall 2018).

The protagonists of cave paintings are usually animals, such as mammoths, deer, buffalo, rhinoceros, lions, chamois, or horses. Unlike the animals, which are treated with great attention, suggestiveness, and plasticity, the human figures are represented synthetically with a few simple lines. These pictorial time capsules, as described by Werner Herzog, who made the documentary film “The Cave of Forgotten Dreams” (

Herzog 2010), were used for cult purposes, and images of sacred animals were always painted in places shrouded in darkness, created over millennia and only visible in the light of a campfire or torch. The placement of paintings in the deepest and most inaccessible parts of the caves suggests that they were part of initiation rites or sacred ceremonies that were accessible only to a select group.

Cave paintings probably played a crucial role in the cohesion of the community, the transmission of knowledge, and the articulation of collective identity. These works were part of the nonverbal social systems that preceded writing. The murals may have served as mnemonic devices, territorial markers, or part of the spiritual governance within hunter–gatherer groups. The act of mural creation itself may have had performative and communal dimensions, reinforcing social bonds and cosmological beliefs (

Whitley 2022).

From a civilizational perspective, prehistoric mural art reflects the emergence of symbolic thought and aesthetic intentionality, which are hallmarks of Homo sapiens’ cognitive and cultural evolution. The sophistication of Chauvet paintings, including the use of chiaroscuro, anatomical accuracy, and spatial layering, testifies to the existence of an early artistic tradition, as well as the capability for long-term planning and abstract thinking. These murals are not only artistic artifacts but also evidence of a nascent visual culture embedded in the early stages of human civilization (

Abadía 2013).

4.2. Mural Painting in Ancient Egypt: Art in the Service of Eternity and Power

Monumental painting in ancient Egypt was completely subordinated to architecture and mainly decorated the walls of temples and tombs. Wall paintings not only express cultural and religious affiliations but also serve as tools to reinforce hierarchy and power (

Lemos 2024). The murals were carriers of ideological content and subject to strict aesthetic and formal canons. The paintings were linear, the figures were outlined in black, and the surfaces of the silhouettes were covered with patches of intense color.

Egyptian wall paintings were prepared using mineral-based pigments derived from readily available natural materials. Black is typically made from charcoal or soot, white from limestone, yellow and red from different shades of ochre and arsenic sulfide (realgar), green from malachite, and blue from lapis lazuli or the synthetic pigment known as Egyptian blue, a copper and calcium silicate compound developed before 3100 BCE. Pigments were mixed with organic binders such as gum arabic, egg white, or animal glue, and reed brushes were applied to prepared plaster surfaces, sometimes even over carved reliefs. The dominant technique was al secco, which means that the paint was applied to dry plaster, allowing high-precision in-line and color applications (

Becker 2022;

Corcoran 2016).

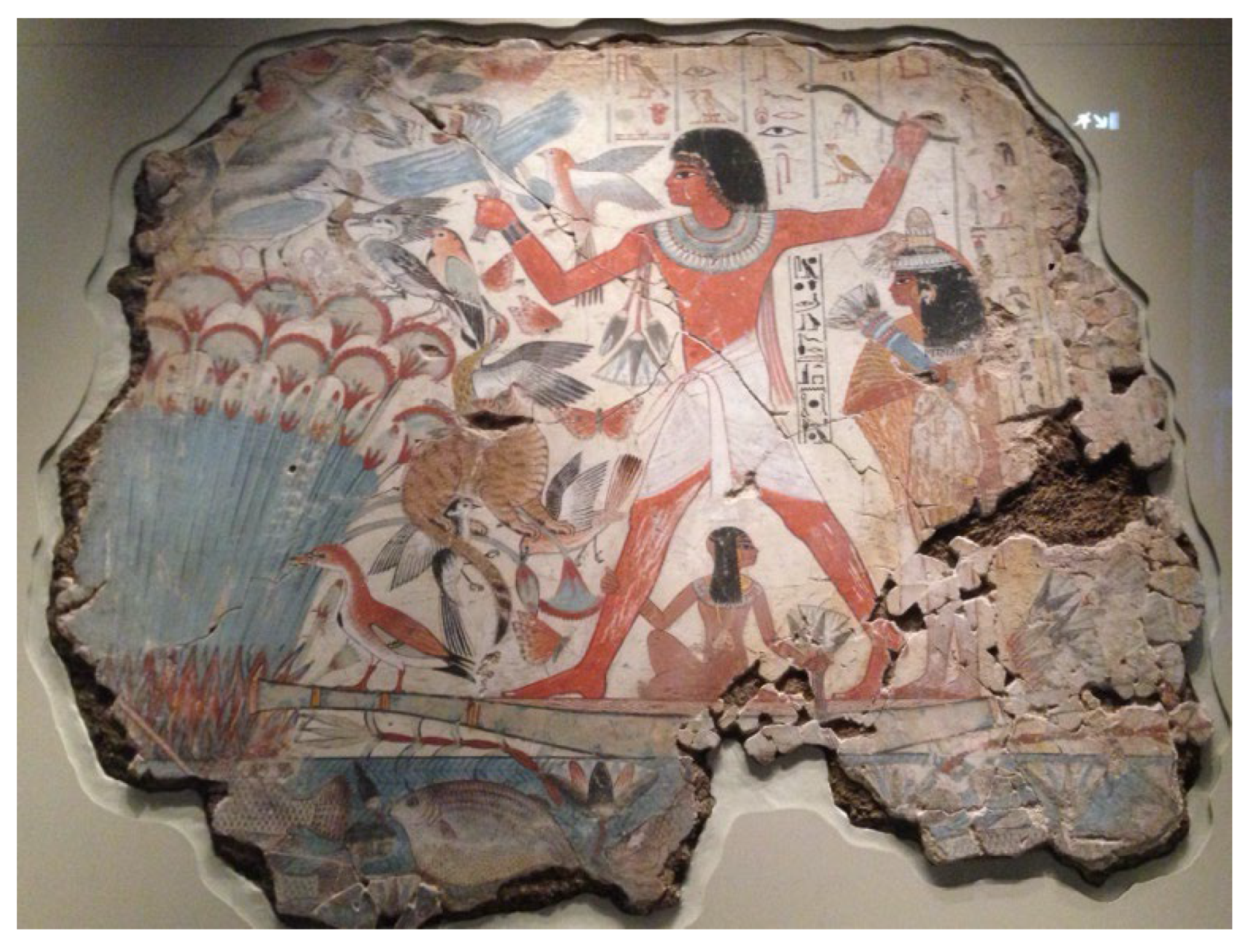

The compositions were organized in horizontal registers, following strict formal conventions aligned with religious symbolism and narrative clarity, reflecting the central function of these artworks in funerary and ritual contexts. Symbolism permeated every element of the Egyptian mural painting. Figures were rendered according to a hierarchical scale, where size denoted status and posture followed strict codifications (e.g., heads and legs in profile, frontal torso). The scenes depicted ritual activities, offerings to gods, mythological narratives, and idealized representations of daily life. These were not naturalistic records, but ideological projection murals were tools to ensure order (maat) and facilitate the deceased’s journey into the afterlife. A sense of observation and sensitivity to beauty can be observed in scenes set against the backdrop of nature. An excellent example is the fresco in the tomb of Nebamun (

Figure 1). The painting depicts a young man surrounded by family and nature in the foreground. The contours and rhythmic order are clearly visible, and the sensitivity and mood of the captured fleeting moment are truly captured, as are the expressiveness of the movement and the dynamics of the wild birds flying out of the thicket.

Elite pharaohs, nobles, and priests commissioned murals in Egypt. The painters, though often unnamed and considered artisans rather than individual artists, formed part of the large workshops that operated within state-controlled temple economies. Mural art was thus an instrument of political theology: it visualized divine kingship, legitimized authority, and reinforced social stratification. Public access to the interior of the temple was highly restricted. Their roles were deeply interwoven with religious cosmology, funerary practices, and political continuity.

Egyptian mural paintings exemplify the integration of artistic production with the state ideology. The uniformity of the style over centuries reflects deliberate conservatism aimed at sustaining metaphysical and institutional stability. Mural art is a medium of immortality, a visual counterpart to hieroglyphic texts, capable of transcending temporal boundaries. The alignment of murals with astronomical, theological, and calendrical systems reveals a civilizational emphasis on order, permanence, and cyclical renewal (

Baines 1990).

4.3. Minoan Crete: Wall Painting as Ritual and Royal Spectacle

The Minoan civilization, flourishing on the island of Crete from approximately 3000 to 1450 BCE, developed a unique visual language of mural painting that combined aesthetic refinement with profound ritual significance. In Minoan paintings, which had an official and religious character, we found similarities with Egyptian paintings. The remains of the ruins of the magnificent residences and palaces of Knossos were discovered and reconstructed by English archaeologist Arthur Evans (1851–1941), who brought us closer to understanding the Bronze Age in the area. The remains of the wall paintings were based on observations of natural phenomena. Court scenes and religious ceremonies are among the most popular motifs.

Color refers to a statement of power and wealth. The colors were obtained from natural pigments, red and yellow ochres, carbon black, calcium carbonate for white, and, importantly, blue obtained from lapis lazuli imported from Egypt. Ancient cultures worshipped colors. Minoan murals were executed primarily using a true fresco technique (al fresco)

, in which pigments mixed with water were applied to a wet lime plaster. This method required speed and precision because corrections were difficult once the plaster was dried. The surfaces were carefully prepared with multiple layers of lime mortar, and the final paintings were often framed with decorative borders or geometric patterns. The use of dynamic lines and contrasting colors gave the murals a vivid, almost kinetic quality that reflected the natural energy of the depicted scenes (

Jiménez-Desmond et al. 2024).

Minoan murals are characterized by a strong connection to nature, rituals, and human vitality. Iconographic motifs include marine life (dolphins and octopuses), floral patterns, courtly processions, and religious ceremonies. One of the most famous frescoes, the “Toreador Fresco” from Knossos, shows figures engaged in bull-leaping, a ritualistic performance that may have had mythological or sacrificial connotations. Unlike Egyptian art, Minoan figures are often depicted in motion with flexible bodies, flowing hair, and expressive gestures.

Minoan murals were produced within the palatial context, closely tied to theocratic governance and ceremonial life. Palaces such as Knossos, Phaistos, and Akrotiri served not only as administrative centers but also as religious and cultural hubs. Wall paintings adorned ceremonial halls, staircases, and sanctuaries, suggesting that mural art functioned as a performative backdrop for elite rituals and public displays. Although the identities of the muralists remain unknown, the consistency and quality of the works indicate the existence of specialized workshops that are likely to operate under aristocratic or priestly patronage. Thus, murals were tools of visual propaganda, reinforcing the ideological authority of the palace complex and its ruling elite (

Cameron et al. 1977).

Minoan muralism stands at a crossroads between Near Eastern traditions and the later Classical Greek canon. It reflects a fluid, nature-oriented worldview in which human beings are not dominant but integrated into the rhythms of the environment and divine order. The art’s elegance, balance, and joyful spirit reveal a civilization oriented towards aesthetic harmony, international exchange, and ritualized social order. In contrast to the monumental severity of Egyptian wall painting, Minoan murals exude dynamism, theatricality, and a sensuous connection to the qualities of the living world that would later reappear in the humanism of classical Greek art (

Pollitt 2016).

Although no original examples of monumental Greek wall paintings have survived, insights into this tradition can be inferred from painted pottery and ancient literary sources. The most renowned early master of monumental painting was Polygnotus, who was active in the 5th century BCE. Although none of his works remain, detailed descriptions, especially those of murals once located in Athens and Delphi, have been preserved. These paintings reportedly depict mythological and historical scenes such as the fall of Troy, the battle with the Amazons, the battle of Marathon, and episodes from The Odyssey. Mythological themes served not only as decorative purposes but also as vehicles for expressing the ethical ideals of the classical period. According to Aristotle, Polygnotus elevated the human figure beyond mere naturalism, imbuing his compositions with moral and philosophical depths. Scholars have attempted to reconstruct these lost works based on surviving accounts, but without definitive results. Some sense of Greek wall painting’s stylistic legacy may be glimpsed in Pompeian frescoes, such as The Punishment of Amor (now in Naples), or Renaissance interpretations including The Maenad Crowning Bacchus in the Villa Farnesina in Rome, which reflect the lasting influence of Hellenistic visual culture (

Ałpatow 1968).

4.4. Roman Wall Painting: Domestic Splendor, Ideology, and the Transition to Christian Imagery

Roman mural painting represents a high point in the evolution of architectural decorations in antiquity. From the 1st century BCE through the 5th century CE, murals adorned the interiors of homes, public buildings, baths, and temples throughout the Roman Empire. Roman paintings, made famous by the discovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii, were buried and destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, but they had decorated the interiors of dining rooms, bedrooms, studies, salons, bathrooms, and baths (

Sigurdsson et al. 1982).

Roman wall painting employs both true fresco (al fresco) and dry fresco (al secco) techniques. The process began with layers of plaster: rough arricio (lime and sand) was followed by a smoother intonaco (lime and marble dust). Artists sketched compositions using incised outlines or charcoal. Pigments included natural and synthetic materials: Egyptian blue, cinnabar, red ochre, malachite, and carbon black, often mixed with water or organic binders such as eggs or casein. As described by Vitruvius (The Ten Books on Architecture) and Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia), Roman painting techniques reflected both technical mastery and concern for durability and visual impact. Recent archaeometric studies have confirmed the use of layered applications and sophisticated pigment recipes (see

García 2020;

Becker 2022). Evidence from provincial contexts, such as Palmyra, confirms the diversity of Roman wall decoration techniques, including the integration of stucco relief and painted surfaces into cohesive architectural programs (

Allag et al. 2010).

Murals followed evolving stylistic conventions that are generally categorized into four styles. This classification was developed by the German archaeologist August Mau in the late 19th century (

Mau 2010). The first was characterized by imitative painting in imitation of wood, marble, or alabaster, often complemented by stucco. The second style features landscape and architectural elements. Mythological scenes predominated, and artists aimed for realistic details, depth, and the illusion of perspective. An interesting motif was the realistic depiction of still life with fruits, vegetables, and other foodstuffs, which were mainly used to decorate dining rooms, pantries, and guest rooms. The third style was characterized by a move away from illusionism towards geometric compositions with clear vertical and horizontal lines. The compositions were surrounded by frames that contained scenes from independent genres. The fourth style brought a return to illusionism, but with new elements of fantastic architecture, characterized by ambiguous and inconsistent divisions of space (

Maguregui et al. 2010;

Vitruvius 1999). Mau’s typological approach to Pompeian wall painting emphasizes its technical and craft-based nature, particularly the limitations of fresco painting, which requires swift execution. He also highlighted the close relationship between mural painting and the architectural context, describing wall paintings as fulfilling an “architectural function”. The decorative schemes of each style were adapted by craftsmen to meet the specific expectations of the patrons. Mau’s use of the term “system” rather than “style” has since been considered more accurate because it better captures the interdependence between the artwork, the architectural setting, and the functional demands of the commissioned decoration (

Salvadori and Sbrolli 2021).

Roman murals present a rich visual vocabulary drawn from mythology, philosophy, daily life, and landscape. The mythological tableaux of Ariadne, Dionysus, and Hercules often represent elite virtues, philosophical ideals, or cultural aspirations. Still lifes (xenia) depicted food and luxury goods, emphasizing hospitality and refinement. Garden scenes, such as those in the Villa of Livia, created illusions of eternal spring, symbolizing fertility and otium, a Roman ideal of cultivated leisure and private retreats from civic duties. Mural art could also serve funerary or apotropaic functions: marine scenes represented passage to the afterlife, and Dionysian imagery referenced spiritual transformation. From the 3rd century CE, with the rise of Christianity, murals began to include biblical and Christological themes, especially in the catacombs of Rome, reflecting the emerging visual theology of the early Church.

Murals were key elements of Roman domestic architecture, especially in the domus and villas of the wealthy. The atrium, triclinium, or tablinum serves as a stage for self-representation, where imagery projects the identity, education, and allegiance of the patron. Art was deeply tied to patronage, elite rivalry, and Romanitas, the values of Roman citizenship. In public baths, temples, and basilicas, murals have civic or ideological functions that reinforce imperial propaganda, moral codes, or collective memory. With the rise of Christianity, mural painting shifted towards religious didacticism, illustrating biblical narratives accessible to an increasingly diverse urban audience. The function of murals transitioned from aesthetic prestige to communal instruction and theological reflection, foreshadowing the visual language of medieval churches (

Cortea et al. 2024).

Roman mural art represents a fusion of Greek aesthetic ideals, Etruscan traditions, and unique Roman innovations. It reflects a society that values both visual pleasure and intellectual engagement. The shift from mythological to Christian imagery illustrates how mural painting has adapted to changing belief systems and power structures, maintaining its role as a mirror of ideological transformation.

4.5. Medieval Mural Painting: Doctrine, Power, and the Didactics of Salvation

During the medieval period, mural paintings underwent a fundamental transformation in both form and function. No longer merely decorative or mythological, wall painting became a central medium in the transmission of religious doctrine, the visualization of sacred history, and the legitimation of ecclesiastical and political authority. The Romanesque and Gothic iconography of Christianity focused on communicating the truths of faith and scripture. Romanesque art drew on themes from the Old Testament and the Apocalypse, whereas Gothic art glorified the New Testament and the image of Mary as a mother (

Myers 2017). Frescoes of this period decorated walls and vaults, as well as the capital of columns or sculptures of churches, monasteries, and chapels. In the early days, in the 12th and 13th centuries, painters applied colors in layers, using a technique described by the Benedictine monk Theophilus (1110–1140) in his treatise “Schedula de diversis artibus”. This technique is labor-intensive but is very durable and retains intense colors for many years (

Theophilus 2009).

A pivotal figure in the transformation of mural paintings during this period was Giotto di Bondone(1267–1337). Giorgio Vasari regarded Giotto di Bondone as a pivotal figure in the development of Italian wall painting and a forerunner of the Renaissance, bridging the gap between the maniera greca and a more naturalistic, modern style (

Vasari 1985). Giotto prepared detailed designs and drawings for each painted panel, often structured as pictorial windows, and delegated the execution of secondary figures, backgrounds, and decorative elements to assistants from his workshop. According to Guiral Pelegrín (

Guiral Pelegrín 2014), such large-scale commissions would not have been possible without coordinated team efforts or a meticulously planned decorative program. The frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel (Cappella dell’Arena) in Padua, completed in just three years, are considered the first fully modern work of monumental painting in Europe (

Cole 1993). Giotto reintroduced spatial depth, human emotion, and narrative clarity, bridging the gap between Byzantine abstraction and Renaissance naturalism. His work imbued Christian scenes with the psychological realism that humanized sacred stories and increased their emotional resonance with viewers.

Medieval muralists predominantly employed a combination of al fresco and al secco techniques, which are often layered. The base consisted of coarse lime plaster, followed by smoother layers for the painting. Pigments were derived from earth and mineral sources: red and yellow ochres, malachite, cinnabar, and Lapis lazuli. Egg temperature and casein were common binders used for finishing details. The use of stencils, incised outlines, and cartoons allowed the replication of complex narrative schemes. Murals were frequently framed within architectural elements such as arches, niches, and vaults to emphasize their integration into sacred spaces.

Christian mural paintings are dominated by biblical iconography, hagiography, and eschatological themes. Common subjects included the Last Judgment, the Crucifixion, scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, and episodes from the lives of saints. Visual language followed established symbolic codes: halos for sanctity, color schemes for theological meaning (e.g., blue for Mary, red for martyrdom), and hierarchical scaling to indicate divine order. Murals served as visual scriptures, often organized in didactic cycles that moved sequentially through biblical events. Their purpose was not to replicate reality but to render the invisible visible to make divine truths materially perceptible to the faithful. This aligns with the Church’s mission of instructing, guiding, and disciplining souls through visual means (

Sesar 2019).

Murals in the medieval period were commissioned by ecclesiastical authorities, monarchs, or wealthy patrons as acts of piety, penance, or political ambition. Churches are the primary spaces in which collective visual experiences occurred. In a time of widespread illiteracy, murals played a vital role in catechesis, teaching the tenets of Christianity through narrative imagery. They were also tools of social cohesion and moral discipline, defining the boundaries between sin and virtue, the sacred and the profane. Murals projected both the divine authority and earthly power. For example, depictions of kings or bishops under Christ’s judgment served to legitimize rulers while reminding them of their accountability to God. Visual narratives thus became political instruments, stabilizing hierarchies and affirming the moral order of feudal society (

Kliś 2024).

Medieval muralism reflects the fusion of visual, theological, and architectural systems, designed to shape collective consciousness through immersion in sacred imagery. The walls of the Romanesque and Gothic churches became textbooks of salvation, where doctrine, memory, and identity were inscribed in lime and pigment.

4.6. Renaissance Mural Painting: Humanism, Perspective, and the Return of the Artist

The Renaissance marked a radical redefinition of mural painting, reflecting the intellectual and cultural transformation that reoriented art from divine abstraction to human-centered naturalism. Mural art became a privileged vehicle for expressing new ideals of proportion, perspective, and individual expression, supported by patronage from the Church, princely courts, and wealthy merchant families. Artists were no longer anonymous craftsmen but recognized as intellectuals and creators of unique vision figures central to the construction of both sacred and secular meaning. More broadly, Renaissance artists have systematically studied classical treatises (for example, Vitruvius), optics, anatomy, and geometry, to develop rationalized space and human proportion. The use of a linear perspective, pioneered by Brunelleschi and Alberti, has become a defining feature of mural compositions, enabling a unified architectural and pictorial illusion.

While many artists continued to employ fresco techniques rooted in the earliest tradition, the Renaissance also saw significant experimentation with al secco and mixed media approaches. Leonardo da Vinci’s mural “The Last Supper” (1495–1498), painted in the Santa Maria delle Grazie refectory in Milan, exemplifies this technical innovation. A tireless painterly explorer and experimenter, Leonardo decided not to apply paint to fresh plaster but to paint on a dry plastered wall, first covered with a layer of powdered lime and later with a primer of white lead (

Pevsner 2002). He used tempera, made from egg yolk, water, and oil, mixed with linseed or walnut oil. Thanks to the use of tempera and oil mixtures, he had enough time to apply successive layers with delicate brushes and strokes, to apply such painterly sfumato, and to chisel the details of the painting without haste, thanks to which he achieved satisfactory shapes and shades. The work was completed at the beginning of 1498, after several years of painstaking effort, and after only 20 years, the paint on the wall of the refectory began to peel. Over the years, six major restorations have been carried out, several of which failed to improve the condition of the painting and even worsened it. The last and most extensive took place in 1978 and lasted twenty-one years (

Leonardo da Vinci 2016).

However, “The Last Supper” represents not only the strength of the painter’s genius but also his creative allegory. There is no doubt that the work is innovative and groundbreaking in every respect—in terms of composition, perspective, form, color, and means of visual expression—and it still leaves an incredible impression and admiration. “The Last Supper” is a combination of the master’s talent and scientific knowledge of perspective with theatrical scenography, a compilation of research intellectualism with unparalleled imagination (

Rzepińska 1988). The artist’s intention was groundbreaking, while the innovative technique used failed, but there is no wonder, as Leonardo’s work is shrouded in many undiscovered riddles and mysteries.

“In the stains on the wall, there are similarities to landscapes decorated with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys, and hills of various shapes. You can also see battles and moving figures, strange faces or clothes, and an infinite number of other things to which you can give the appropriate shape and desired form. The coloured wall is like the sound of bells; you can make out any word or name that comes to your mind (…). If you look carefully at such walls, or at the ashes of a bonfire, or at the clouds in the sky, or at muddy puddles, you are bound to find great ideas in them, for the obscure and the indefinable stimulate the mind to new ideas.”

While religious themes remained central, Renaissance mural painting introduced a new emphasis on human emotions, realistic anatomy, and spatial coherence. Biblical scenes became psychologically charged narratives, as exemplified by Leonardo’s Last Supper, in which each apostle expresses a distinct emotional reaction to Christ’s words. Simultaneously, classical mythology and Neoplatonic allegory entered mural programs, particularly in civic and domestic interiors, infusing them with philosophical and humanist meanings, as seen in Raphael’s works in the Vatican Stanze.

Mural painting serves as a visual language of power and ideology used by both the church and secular patrons. In churches, it supports liturgical functions while emphasizing human beauty and emotion. Courts and city halls communicated dynastic legitimacy and civic pride. Monumental commissions by Michelangelo, Raphael, and others elevated the artist’s status by linking authorship to intellectual authority and cultural prestige. Renaissance muralism reflects a fusion of Christian humanism, classical ideals, and scientific inquiry. It visualizes a world governed by reason and proportion yet animated by personal expressions. Mural art became not only a tool of instruction or devotion but also a medium through which the values of Renaissance dignity, order, and knowledge were inscribed directly onto the architecture of public and sacred life (

Potenza et al. 2025).

4.7. Baroque and Rococo Mural Painting: Theatricality, Illusion, and Power

After the Renaissance, mural paintings became more dynamic and theatrical under the influence of Mannerism, Baroque, and later Rococo. These styles responded to the ideological needs of the Catholic counter-reformation, consolidation of absolutist monarchies, and refined tastes of the aristocracy. While public accessibility was limited during this period, the formal sophistication and sensory power of mural art reached a new height. Baroque artists, including Andrea Pozzo, Pietro da Cortona, and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, have mastered techniques such as fresco and secco, often combined with quadrature, a method of architectural illusionism that visually extends real space into painted realms. Murals on church ceilings and palace walls became staged visions, where divine or allegorical figures appeared to ascend into heaven or descend into earthly interiors. The use of di sotto in sù perspective further intensified the immersive experience, while Rococo murals introduced pastel tones, ornamental motifs, and fluid, playful compositions (

Mora et al. 1999).

Thematically, Baroque muralism focuses on religious exaltation and emotional intensity. The works portray saints in ecstasy, martyrdoms, and visions of divine triumph designed to awe the viewer and reaffirm faith. In secular contexts, murals glorify dynastic power, classical virtues, and imperial ambitions. In contrast, rococo mural painting embraced lighter themes such as mythology, courtly leisure, and pastoral fantasies, mirroring elite ideals of beauty and pleasure (

Rzepińska 1988).

These murals were rarely accessible to the public and were commissioned by popes, monarchs, and noble patrons. The Jesuit order played a key role in disseminating mural paintings across Europe and colonial Latin America, using visual language as part of its global evangelization strategy. In this period, mural art functioned as an ideological spectacle, reinforcing authority through illusion and grandeur. Although not participatory in the modern sense, Baroque and Rococo murals greatly expanded the visual and technical language of muralism. Their innovations in space, perspective, and immersive composition laid the groundwork for future developments in monumental and public art (

Rzepińska 1988).

4.8. Mexican Muralism: Revolutionary Art and the Birth of Modern Public Painting

Following the Baroque and Rococo periods, where mural painting was largely confined to religious and aristocratic interiors, modernity ushered in a fundamental transformation in both the purpose and the audience of wall art. The decline in court patronage, the advance of secularism, and the industrialization of cities have altered the social and spatial functions of visual culture. Monumental art has moved beyond ecclesiastical ceilings and palace walls, seeking new relevance in emerging public spaces. These shifting conditions laid the groundwork for the rebirth of muralism, now reimagined as a tool of mass education, political messaging, and cultural identity.

Mexico undoubtedly played a key role in the development of modern murals. In the 1920s, mural art found perfect conditions for development and visual communication (

Katzew 2004). After the Mexican Revolution, it aimed to convey socio-political messages of communal integration, unity, and the construction of a national identity, which found the ancient tradition of mural painting in Mesoamerican cultures, specifically developed in the Mayan area of influence, to support these objectives. Mural paintings by artists such as Roberto Montenegro, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco, strongly influenced by the ideological and plastic approach of artist Gerardo Murillo, the first muralist of this movement, became the most important form of engagement, often the subject of tension and antagonism, but ultimately a symbol of freedom and hope for a better future (

The Art Story 2025). It laid the foundation for contemporary urban muralism by articulating a new paradigm, public art, as a political discourse.

Diego Rivera (Diego Maria de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez) (1886–1957) became so enamored of Italian quattrocento fresco painting, particularly the works of Giotto in Assisi, Florence, and Padua, during his travels in Europe, that he decided to use this large-scale medium in his work. Rivera’s elaborate, authorial, avant-garde, and bold style, incorporating elements of Cubist space and industrial pre-Columbian forms, alluding to the language of realism, would be a recognizable feature of his paintings (

Mitter et al. 2008). He was commissioned by the Mexican government to paint the most famous murals in the public buildings of the capital. As a member and staunch activist of the Communist Party, he painted monumental scenes of the lives of poor Mexicans alluding to Indian roots and pre-Columbian traditions. On his return from Europe, his first commission in 1921 was the mural creation in the Simón Bolivar Amphitheater at the National University of Mexico. The main theme of the mural is the fusion of the indigenous and European heritage of the Mexican people, united by a representation of the Tree of Life (

Gutiérrez Alcalá 2022). In the buildings of the Ministry of Public Education and the National Palace, he created epic murals of the history and culture of his nation, extolling the origins of the ancient cultures that make it up and asserting its uniqueness, regardless of its fusion with European culture.

In the 1930s, Diego Rivera was invited to San Francisco by the architect Timothy L. Pflueger, who admired his work, where he painted frescoes for the San Francisco Stock Exchange Club and the California School of Fine Arts. This retrospective study was conducted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1931. Rivera invented a portable mural consisting of smaller panels that are easier to move and transport. In 1932, another admirer of his murals, Edsel Ford, commissioned twenty-seven panels entitled “The Detroit Industry”, depicting workers of various nationalities engaged in the construction and assembly of automobiles. After Detroit, another financial tycoon, Nelson Rockefeller, invited Rivera to paint a mural during the lobbying of the RCA building in New York. The artist completed the work, but unfortunately, the mural was destroyed by ideological conflict. In 1953, he completed his last and most important large-scale mural on the façade of the Teatro de los Insurgentes in the Mexican capital, depicting four centuries of the country’s history and focusing on the fate of society in the 1950s (

DiegoRivera.org 2025).

Mexican muralists initially revived traditional fresco painting techniques but adapted them to modern ideological content and local materials. Artists painted directly onto the plastered walls of civic buildings, universities, and cultural institutions. Diego Rivera, for example, used secco and true fresco in large-scale works using lime-based plasters, natural pigments, and often monumental compositional schemes. He was also a pioneer in portable murals, composed of transportable panels (e.g., Detroit Industry Murals), facilitating the dissemination of political messages across contexts (

Indych-López 2007).

Mexican muralism has emerged as a state-sponsored movement promoted by post-revolutionary governments seeking to build a new national identity through public art. Murals appeared in schools, palaces, and government buildings, making art accessible to all, especially workers and indigenous communities. Many artists, often aligned with leftist ideologies, saw muralism as a tool for political education and awakening. Mexico’s walls became ideological battlegrounds where indigenous identity, socialist ideals, Catholic tradition, and modern industrialism intersected. However, muralism also faced opposition and censorship, most famously in Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads, which was destroyed after a conflict with its capitalist patron. This tension between state sponsorship and subversive intent remains central to the history of public art (

Carter 2019).

Mexican muralism has created a powerful synthesis of indigenous heritage, European techniques, and revolutionary ideals. It redefined wall painting as a medium of mass communication and cultural resistance, breaking away from elite traditions and empowering artists as public historians. Its influence extended far beyond Mexico, inspiring movements in the United States, Latin America, and Europe. By giving voice to oppressed identities and political dissent, Mexican muralism laid the foundation for both protest art of the 1960s and street art of the 21st century.

4.9. Muralism Beyond Mexico: Global Echoes and Adaptations

The impact of Mexican muralism, rooted in pre-Hispanic traditions and the revolutionary politics of post-revolutionary Mexico, extended beyond Latin America, influencing various European artistic movements, particularly Socialist Realism and Surrealism. This exchange was not one-directional; rather, it created a dialog in which European avant-garde artists began to explore muralism as a means of integrating art, politics, and public space. In countries such as France and Spain, artists experimented with murals from diverse ideological and aesthetic perspectives. For example, Diego Rivera’s work served as a key precedent for politically engaged public art and influenced figures, such as the Spanish painter José Royo, who adapted muralism to new social contexts in Europe (

Mink 2022).

The greatest exponent of the development of the mural, with a significant influence on both European and Latin American contexts, would be Joan Miró. From the outset, this artist showed a natural preference for large-scale formats, and his fascination with the wall was the starting point of his painterly practice, both as an object to be depicted and as inspiration for the textural quality of his works (

Figure 2) (

Gomez Lobon et al. 2024).

Miró distanced himself from the simple reproduction of reality and equated the picture plane with the wall. He explored the structure of its surface and sought to dissolve the boundaries of pictorial space. Miró’s work encompasses all the phases described in this text, from the incorporation of primitivism, which he documented in the Gran Cuaderno de Palma (1940–1941), where he noted that he should think about the maximum synthesis of prehistoric paintings and their integration into the artistic culture of his time, to his exploration of Renaissance muralism, Mexican influences, and his incorporation into the Surrealist movement. However, the social and revolutionary themes of his work took a back seat in the development of his plastic art, which soon blurred the boundaries between mural painting, sculpture, and architecture through his constant collaboration with modernist architects such as Josep Lluís Sert and prominent ceramists such as Josep Llorens Artigues. These collaborations allowed him to develop new approaches, not only in terms of format but also in terms of technique, sometimes bridging the gap between the tradition of pictorial currents and urban art, which, from the middle of the 20th century, was to undergo significant development and recognition as an artistic discipline.

The symbolism of murals, as with other forms of public art, has continuously evolved, shaped not only by professional artists but also by local communities engaged in creating bold and socially conscious imagery. One significant example is Mujeres Muralistas, the first all-female muralist collective in San Francisco, which combines the rich tradition of Mexican muralism with contemporary social narratives in vibrant large-scale compositions. Another landmark project is The Great Wall of Los Angeles, initiated in 1976 by Judy Baca (b. 1946) in Los Angeles. This ongoing work was considered the longest mural in the world, with the participation of more than 450 young people from diverse cultural backgrounds, 40 scholars, and a large team of assistants. Along the San Fernando Valley flood control channel, it narrates the history of the region from its prehistoric roots to the present day. Images include scenes such as the founding of Los Angeles in 1781, railroad construction, forced deportation of Mexican and Japanese Americans, and the 1984 Olympic Games (

Chadwick 2015).

Artists working outside of Mexico adopted diverse techniques that blended traditional fresco and secco with modern materials such as acrylics, enamels, ceramics, and even industrial coatings. Joan Miró developed site-specific works in close collaboration with architects and craftsmen, integrating texture, surface irregularities, and scale into the artistic concept. Meanwhile, in the United States, collectives such as Mujeres Muralistas and projects such as The Great Wall of Los Angeles often relied on accessible, weather-resistant materials such as exterior acrylics and masonry paint, suitable for community participation and urban exposure.

The symbolic language of these murals was heterogeneous, but consistently community-oriented and socially reflective. European artists experimented with surrealism, abstraction, and primitivism to evoke universal or existential themes, while US-based artists focused on cultural heritage, social justice, and identity politics. The murals created by Mujeres Muralistas celebrated Chicana identity and women’s experiences, while Baca’s Great Wall constructed a multi-ethnic narrative of Los Angeles, challenging dominant historical accounts. Murals beyond Mexico have become tools for grassroots expression, historical recovery, and public empowerment. Whether funded by the state or initiated by the community, they provide visual platforms for political dialog, educational storytelling, and symbolic healing. The dual character of muralism as both institutionally supported and subversively critical remained present, echoing the tensions established by Mexican predecessors (

Anreus et al. 2012;

Wang and Wu 2023).

This transnational expansion of muralism reflects a broader 20th-century cultural shift: the democratization of visual culture. Wall painting was not just a decorative or elite form but a collective medium embedded in civic architecture and social life. It bridged fine art and activism, memory, and space and laid the conceptual and visual groundwork for contemporary urban art and participatory aesthetics in the 21st century.

5. Street Art as Contemporary Muralism: Space, Protest, and the Aesthetics of Urban Resistance

“It is not a matter of observing the street through a pane of glass, which is very fragile, yet hard, and impenetrable, but of entering the street ourselves. An open ear and an open eye transform our trivial emotions into powerful experiences. Sounds come from all sides; the whole world is reverberating. We make discoveries in the everyday—like an explorer venturing into unknown territory—and the hitherto silent surroundings begin to speak to us in increasingly intelligible voices.”

Street art, also known as urban art, is a form of artistic expression in a public urban space. It is a form of artistic or visual expression that transcends the interiors of art galleries and museums to become a real street gallery and exhibition in larger and smaller urban areas (

Yan et al. 2019). Street art has been transferred from large canvases to the walls of buildings, apartment blocks, flyovers, or post-industrial spaces.

To better understand the nature and significance of street art, we must highlight the events and works that developed in the 1960s in Paris, where street art began to play an important role in the global artistic scene. Polish Jewish artist Gérard Złotykamień, known as Zloty, born in Paris on 19 April 1940, played a prominent role in this movement. He started his artistic career in 1963 (

Martinović 2017) and was inspired by the spray technique used by Yves Klein, with whom he was friends (

Rościecha-Kanownik and Martyka 2023). His spray-paintings expressed a profound ethical protest against human suffering, reflecting on the Holocaust, war, and violence through stark confrontational imagery. The artist’s actions on Parisian thoroughfares were a factor in activating artists to recognize the street as a creative studio. This trend has become popular in the United States. A subsequent artist who developed contemporary street art techniques was Blek Le Rat, who was the first to use ready-made stencils in the 1970s. Blek Le Rat, or Xavier Pruo, was born in Paris on 15 November 1951, and began painting iconic rats from stencils, which he claimed were the only free animals in the city and spread plague, just like street art. Hence, his artistic pseudonym is derived from the comic strip Blek le Roc, in which the word ‘rat’ is an anagram of the word ‘art’: RAT—ART (

Blek le Rat 2025).

In the 1980s, graffiti became a popular form of artistic expression in Bristol, practiced mainly by young artists, presumably including Banksy. Painted at night, these activities were risky, as they were illegal. Although the artist remains anonymous, he is believed to have been born in London or Bristol. His first significant work, The Mild Mild West, was created in 1997 by Stokes Croft in Bristol. The mural depicts a teddy bear throwing a Molotov cocktail from three police officers. Even in his early work, Banksy addressed themes that remain relevant in his work today: pacifism, anticapitalism, antiestablishment, and anticonformism. In 2002, Banksy abandoned classic spray graffiti in favor of stenciling, which gave his work a dynamic and cinematic feel—the figures seem full of life, as if they were about to come off the walls. The artist categorically denies being inspired by Blek Le Rat’s work, claiming that he came up with the idea of using stencils independently (

Bansky 2024). Banksy’s work has gained international acclaim and has appeared in many cities around the world. In 2002, they were on display in Los Angeles; in 2005, he created nine murals on the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem; in 2008, he was in New Orleans; in 2010 in San Francisco; and in 2013 in New York. In 2018, he left ten works in Paris, from the Centre Pompidou to Montmartre and the boulevards of the Seine (

Potter 2018). In 2022, his murals appeared in the ruins of buildings in Kyiv (seven works). These murals were part of the dramatic landscape of the ruined city, highlighting both the brutality of aggression and the hopes of survival and rebirth (

Figure 3).

Another notable example is the artist Andrea Coppo, known as Kenny Random, born in 1971, who lives and works in Padua. He also uses stencils and sprays to create his sentimental, recognizable style of illustrating the world. The main aim of this street artist is to bring a gallery of his own art to the streets of this beautiful, historic university city, where Nicolaus Copernicus, Jan Kochanowski, and Jan Zamojski studied. In Padua, the Scrovegni Chapel houses priceless frescoes by Giotto, dating back to 1305 (

Rościecha-Kanownik and Martyka 2023). In such a cityscape, Kenny’s work can be found on the walls of old architecture (

Figure 4). His art is a mixture of folklore, lyrical reverie, and sensuality. In his world, everything is possible; the figures are hypnotic, and the reality resembles a dream. In his own way, Kenny Random can be unbearable in his imagery; we are stimulated by his obtrusive theatricality, his vivid and contrasting colors, and his intricate puzzles of symbols. He combines the past with the present tradition. For years, he has aroused strong emotions and left no one indifferent. His immense imagination has created an extraordinarily expressive world full of sentimental emotions and positivity.

Murals in Padua combined contemporary art with the precious historical heritage of the city. The artistic works on the walls of buildings, created by local and international artists, enliven the streets and squares and add color and narrative. The murals have become an integral part of the urban landscape, underlining Padua’s openness to new forms of artistic expression. The murals created a unique atmosphere in the city by combining history with today’s creative energy.

A step forward in the evolution of mural street art in recent decades has been taken by the Portuguese artist Artur Bordalo (b. 1987), who works under the pseudonym Bordalo II. His art focuses on the material realm, animal studies, materiality studies, and multispecies ethnography. He creates technical murals, that is, not just with a brush, but with anti-materials and scrap metal. The spirit of the Dadaism of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) or Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948) is expressed in them. Bordalo II’s wall collages have very specific characteristics: first, they invade the public space of Lisbon and various other Portuguese cities; second, they are large in size, so that the artist wants to invite the viewer to approach them from a distance; and third, they are created on the walls entirely from pieces of sheet metal. Despite their apparent spontaneity, Bordalo II’s works are carefully composed, with the shapes and colors of the waste materials used being carefully chosen. The use of a layered structure allows the creation of a three-dimensional composition, where the wall on which the material is pasted or incorporated is enhanced by additional graphic or painted motifs. The artist adds color intensity to his works by using colored sprays, emphasizing their dynamic and expressive character. Bordalo II’s works, in which waste, including plastic, is the main material, are an excellent example of how rubbish can become an artistic medium. By creating colorful animals from waste, the artist forces us to reflect on the problem of the overproduction of waste, especially plastic, and its impact on the environment. His spectacular sculptures are both a commentary on contemporary consumption and a call to ecological responsibility (

Figure 5).

The complexity of Bordalo II’s work reveals a sublime expression in Lisboa Factory LX, an old industrial complex that has been transformed into a modern cultural center filled with shops, restaurants, music venues, and other attractions, a good example of contemporary urban regeneration in which street art plays an important role. The mural of a bee created by Bordalo II on one of the walls of the building perfectly fits into the post-industrial aesthetic of this place. The use of a collage of materials in the artist’s work and techniques that combine elements of realism and abstraction are integral parts of the Factory LX space. The mural, painted in royal colors, not only blends in with the architectural surroundings but is also an important element in attracting young people and artists. As part of a wider revitalization process, the artwork contributes to the regeneration of the space, adding aesthetic and cultural value while reinforcing the identity of the place (

Figure 6).

Street art employs a wide range of techniques, including spray paint, stenciling, paste-ups, installations, and more recently, 3D collages, found object assemblages, and augmented surfaces. Artists such as Blek Le Rat pioneered stencil techniques in the 1970s, and Banksy popularized this approach globally with cinematic compositions. Others, such as Kenny Random, combine traditional street media with poetic and symbolic figures. A notable expansion of material practices comes with Bordalo II, whose mixed-media murals are composed entirely of urban waste, scrap metal, plastic, and wood, creating dramatic 3D animal portraits on city walls. His work bridges the gap between muralism, sculpture, and environmental activism.

The iconography of street art is intentionally direct, often critical, poetic, or provocative. Early street artists, such as Zloty, tackled the themes of war and memory; Blek Le Rat used rats as metaphors for subversion and uncontrollable resistance. Banksy infused political satire with simplicity and irony, addressing anti-capitalism, pacifism, and media manipulations. Kenny Random’s work transforms the street into a dreamscape where folklore and intimacy dominate the narrative. Bordalo II’s animals function as ecological warnings, turning urban waste into symbolic reminders of the costs of consumerism. Street art democratizes visual culture: created without permission, often anonymously, it challenges institutional hierarchies and reclaims public spaces for marginalized voices. Whether through poetic expression or explicit protest, street art reflects contemporary concerns about urban gentrification, identity, the environment, and resistance. Works such as The Great Wall of Los Angeles by Judy Baca or collectives such as Mujeres Muralistas exemplify street-based practices rooted in community collaboration and historical narrative.

Although many street artists operate outside of institutional structures, street art is increasingly intersecting with urban policies, cultural festivals, and commercial branding. Projects such as street art cities and the urban national museum in Berlin illustrate a shift from illegality to cultural legitimization. This institutionalization presents both opportunities and risks: While it offers funding and visibility, it can also neutralize the political potency of street art. Murals are sometimes used for gentrifying neighborhoods, contributing to cultural displacement, even as they claim to empower communities. This paradox raises critical questions about spatial ownership, artistic agency, and ethical representation. Artists such as Banksy have responded by rejecting authorship, resisting commodification, and even sabotaging the art market (e.g., partially destroying artworks at auctions). Others embrace social practice models and collaborate with local communities, activists, and institutions to co-create meaning and preserve authenticity. Street art is inherently democratic and subversive. Often produced without permission, it challenges the dominant narratives about who shapes the public space. It has become a vehicle for political criticism, urban resistance, and collective memory. Participatory projects such as Mujeres Muralistas and Judy Baca’s Great Wall of Los Angeles are powerful examples of historically engaged public art. These initiatives return the visual space to underrepresented voices and promote intergenerational dialog.

In recent years, street art has been adopted as a tool for urban regeneration, social activism, and cultural tourism. However, growing institutional interests have intensified tensions around commodification, heritage status, and gentrification. Once seen as ephemeral and rebellious, murals are now preserved, curated, and monetized. La Nasa et al. (

La Nasa et al. 2021) noted that murals have come to be viewed as an endangered cultural heritage, introducing new challenges for artists and conservators regarding durability, authorship, and integrity. Projects such as Quinta do Mocho in Lisbon exemplify these contradictions, while murals help build local identity and resist neoliberal urban planning (

Castellano and Raposo 2024).

They also attract external capital and transform local economies. Thus, street art operates in a complex tension between resistance and co-optation, simultaneously critiquing urban change and participating in it. This dual character of grassroots, institutional, spontaneous, and curated art underscores the evolving role of street art in contemporary cities. As Flusser (

Flusser 2015) observed, images are not just documents but projections of meaning shaped by imagination. In this sense, murals function as collective and individual manifestos, expressing contemporary anxieties about war, ecology, identity, and the right to the city.