Designed Segregation: Racial Space and Social Reform in San Juan’s Casa de Beneficencia

Abstract

1. Introduction

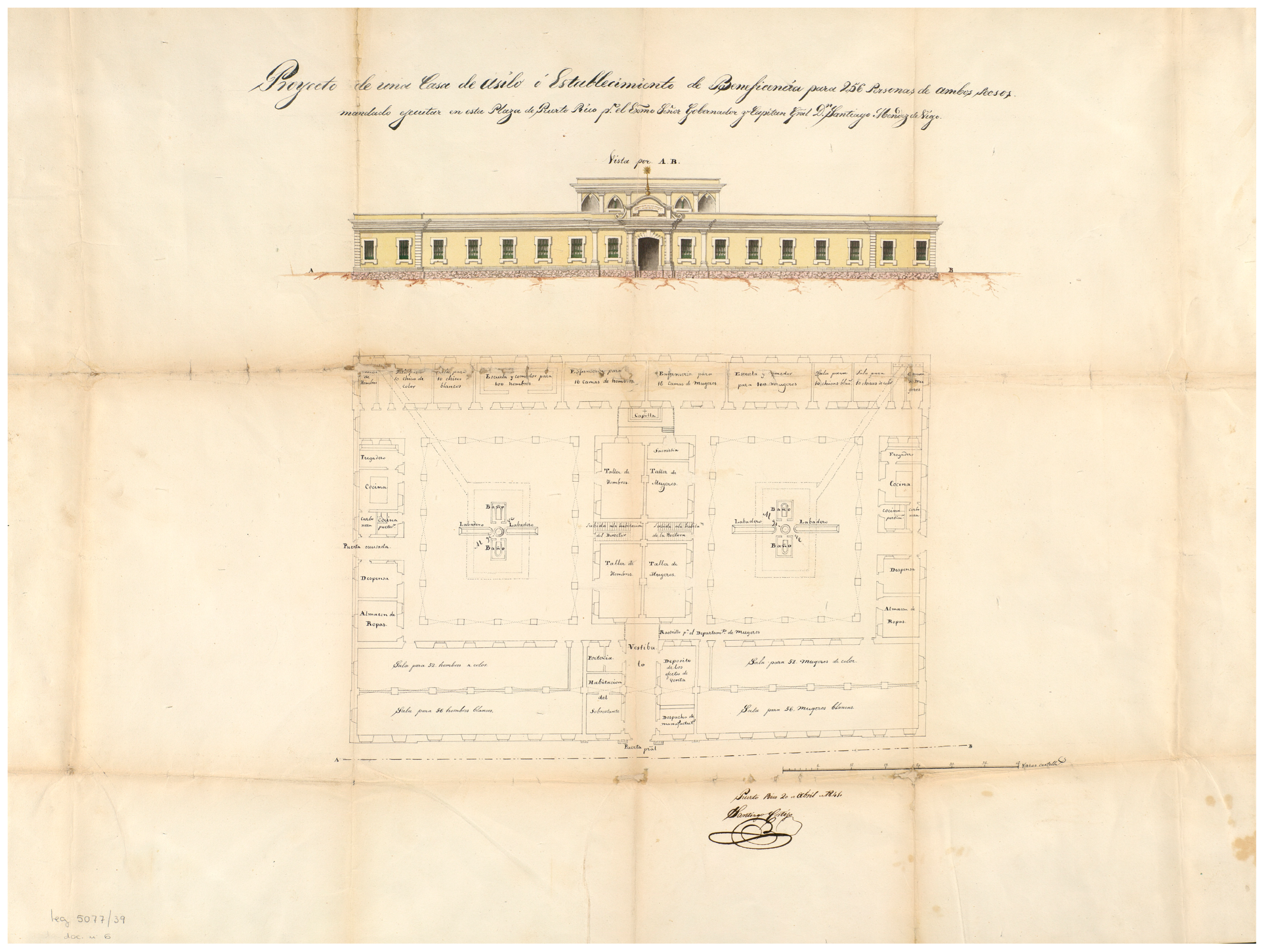

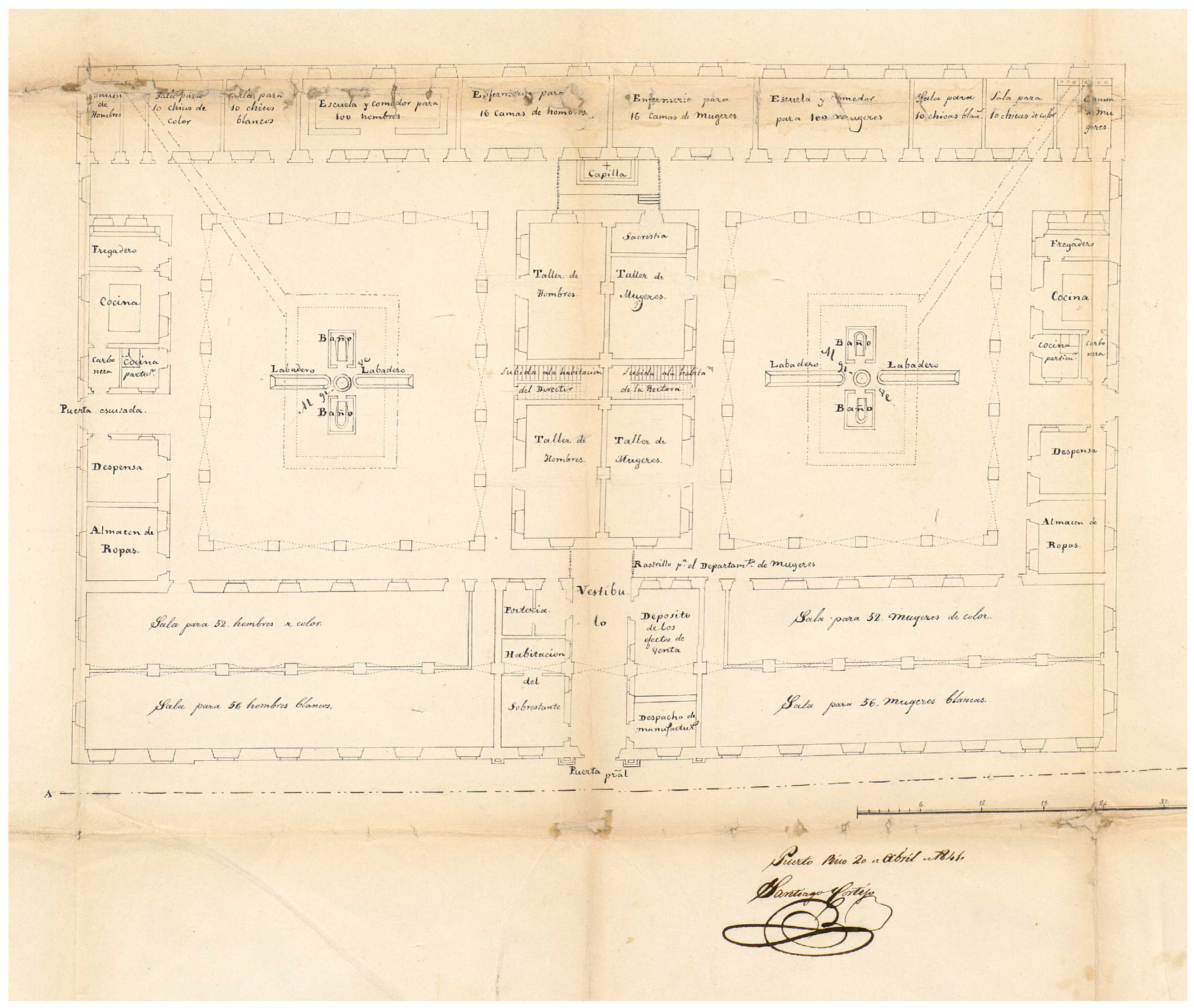

2. Santiago Cortijo and the Work of Planning

3. San Juan and the Urban Settings of Social Identity

4. Race, Space, and Social Control

The Casa de Beneficencia is being established in the most satisfactory way, being the result of the paternal views of…[the current governor’s]…predecessor…Don Santiago Méndez de Vigo. That careful cleanliness, good morality, policía (civility and social order)13, healthy and abundant food, and a regularized and laborious life insensibly improve those included in it…that there are in the house 27 locos (mentally ill people) from both sexes and 16 women…in a separate room of the building, isolated from the establishment.14

the solemn poor can collect themselves there…[while the institution also offers] the necessary asylum to the elderly who cannot earn their livelihood and to the disabled who are in the same house; which at the same time serves as a correction to the women which justice sentences to imprisonment, but that can instead be collected in it, those whose relaxed conduct obliges the authorities to separate them from the vices with which they scandalize morality and good customs.22

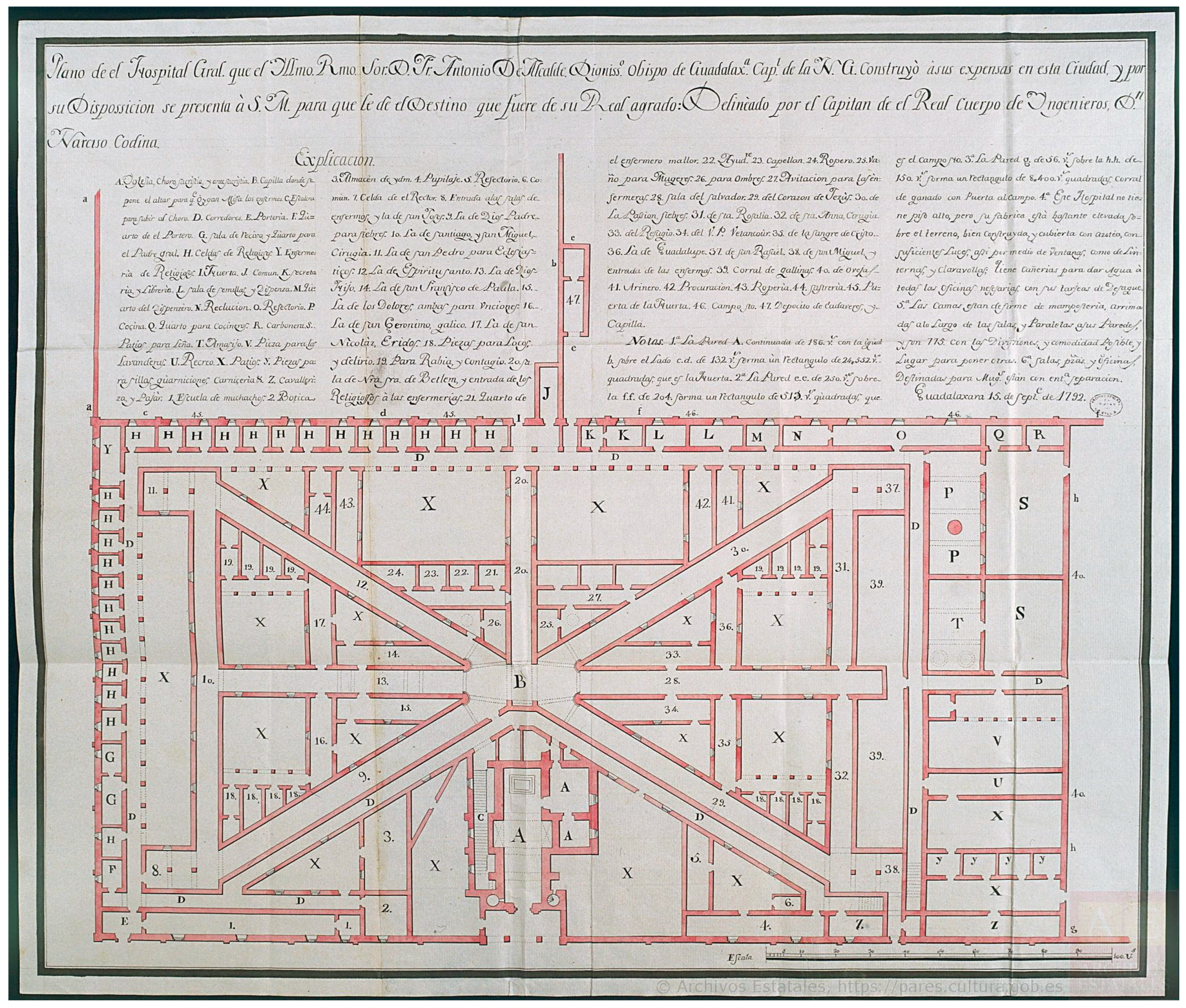

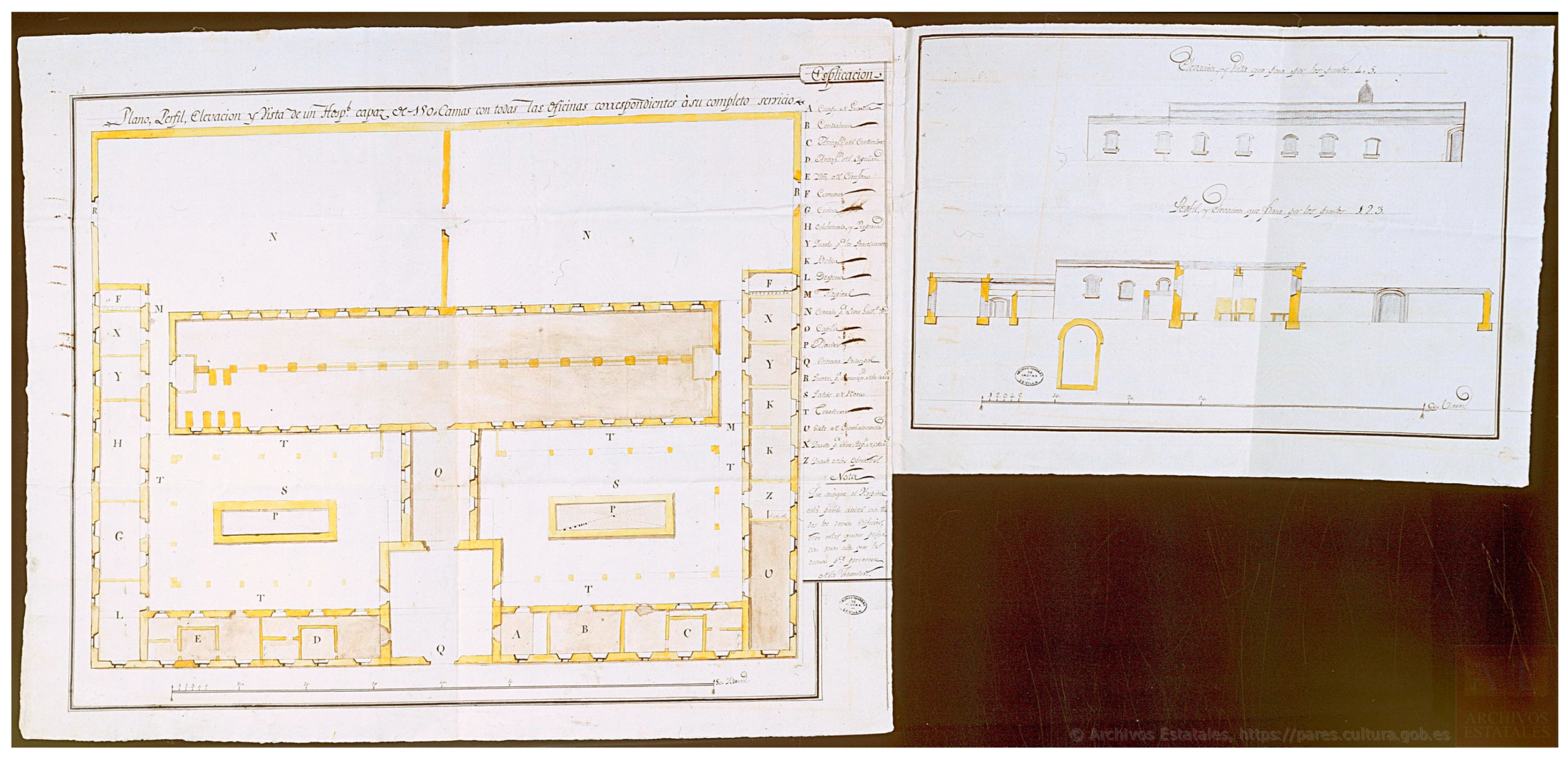

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For an architectural history that covers the Casa de Beneficencia in San Juan, see (Castro 1980; Pabón-Charneco 2010; Pabón-Charneco 2016). For this area of the barracks, the Cuartel de Ballajá, and its development, see (Ballajá: Arqueología Histórica de un Barrio de San Juan 2004; Barnes 1995). |

| 2 | The inscription reads, in full, “Comenzaron las obras de este asilo en 1841 siendo Gobernador y Capitan General el Excmo. Sr. Don Santiago Mendez Vigo se terminaron en 1847 bajo el Gobierno del Teniente General Excmo Sr. Conde de Mirasol. En 1897 y con la Direccion del Vice-Presidente de la Comision Provincial Excmo. Sr. Don Manuel Egozcue se construyo la planta alta del edificio apadrinando la bendicion del local hecha por el Ultmo. Sr. Fray Toribio Minguella los Excmos. Srs. Don Sabas Marin Gobernador Gral. de este provincial y su distinguida esposa Da. Matilde de Leon de Marin”. |

| 3 | Such studies of Puerto Rican architecture include Maria de los Angeles Castro (Castro 1980; Pabón-Charneco 2010; Pabón-Charneco 2016). |

| 4 | Reglamento General de Beneficencia Publica decretado por las Cortes Extraordinarias en 27 de Diciembre de 1821 y sancionado por S. M. Reimpreso en Puerto Rico. En la imprenta del Gobierno, a cargo de D. Valeriano de Sanmillar. Añosas de 1822, p. 12. Archivo General de Puerto Rico, Fondo Municipios de San Juan, Legajo 26, Exp. 2, 1822. |

| 5 | “las mugeres que habiendo concebido ilegítimamente se hallen en la precision de reclamar este socorro”. Ibid. |

| 6 | There are several reglamentos for these Casas de Beneficencias, as listed among the printed primary sources in the references of this article. For the architecture of asylums, see (Johnson 2001; Yanni 2007; Casella 2007; Fennelly 2019; Ziff 2012). |

| 7 | (Godsden 2004, p. 135) Gosden draws from (Deleuze and Guattari 1987). |

| 8 | (Niell 2014) The architecture of Havana’s Casa de Beneficencia is discussed on p. 259. |

| 9 | “Artículo de Oficio. Circulares expedidas por el Excmo. Sr. Presidente, Gobernador, Capitan General y Gefe Político Superior a las Autoridades de la Isla”. Circular no. 38, 2 March 1841. Gazeta de Puerto Rico, 13 March 1841. |

| 10 | For this process of eviction of bohíos to construct the Ballajá barracks and the neighborhood’s previous inhabitants, see (Ballajá: Arqueología Histórica de un Barrio de San Juan 2004; Barnes 1995). |

| 11 | For the concept of coloniality, see (Quijano and Ennis 2000). |

| 12 | (Kinsbruner 1996, p. 50). For other sources on nineteenth-century society in San Juan, see (Matos Rodríguez 2001). |

| 13 | For an in-depth discussions of policía, see (Escobar 2003, pp. 202–205). |

| 14 | “…la Casa de Beneficencia se va estableciendo del modo mas satisfactorio, siendo el resultado de las paternales miras de su antecesor el Ten. General D. Santiago Mendez de Vigo. Que el aseo esmerado, buena moralidad, policía, alimentos sanos y abundantes, y una vida regularizada y laboriosa ván mejorando insensiblemente a los recogidos en ella…Que hay en la casa 27 locos de ambos secsos y 16 mugeres… en una sala del edificio separada i incomunicada con el establecimiento”. Archivo Histórico Nacional, Ultramar, 5077, Exp. 38, (1841–1858), “Expediente general de la Casa de Beneficencia de Puerto Rico”. |

| 15 | “la educación primaria de los niños acojidos aumentándola con la música…los enfermos son asistidos sin ir al hospital, a no ser en caso de mal contagioso; y por ultimo, que la moral ha mejorado muhco en las reclusas por estar todas bien inpuestas de los deberes de la Religion”. Ibid. |

| 16 | “muy satisfecha al saber que aquella casa de Beneficencia llena el objeto de su instituto, y que esta admiración de cuantos concurren a visitarla; prometiéndose del celo de su director que procurará llevar a efecto cuantos adelantos y mejoras sean posibles, y que se esmerará en inculcar el amor al trabajo y máximas de moralidad en los densalidos y desgraciados, que se hallan regugiados en aquel ante tan piadoso y filantrópico”. Ibid. |

| 17 | Drawing on the concept developed by Julienne Hanson and Bill Hillier that all space is inherently social and vice versa, many elements of Puerto Rico’s built environment during this period emerged from reformist ideologies (Hillier and Hanson 1984). |

| 18 | Captains-general was one of the titles held by the Spanish governors of Puerto Rico and Cuba. Martínez-Vergne, (Martínez-Vergne 1999, pp. 4–5). |

| 19 | The full passage reads as follows, “el establecimiento a que se trata es muy consonante con el estado actual de la Isla y con las luces del siglo, pues no hay Pueblo alguno de regular cultura que no lo tenga…..ninguna cosa mas conveniente que reparar del trato comun aquellos mugeres que no habiendo tenido fuerras bastantes para doblegar sus pasiones y venceslas, se defaron arrastrar de ellas, como que su conducta es un contagio cuyo fomes puede dañar a muchas incautas y viesar a muchos forenes”. Archivo General de Puerto Rico, Fondo Municipios de San Juan, Legajo 26, Exp. 8, 1838, “Expediente sobre establecimiento de una Casa de Reclucion y Correccion”. |

| 20 | For scholarship on the casta paintings, see (Carrera 2003; Katzew 2004). |

| 21 | For the relationship between race and modern architecture, see (López-Durán 2018). |

| 22 | “los pobres de solemnidad ofresiendo el asilo necesario a los ancianos que no pueden ganar su sustento y a los imposibilitados que se hayan en el mismo casa; que al mismo tiempo sirva de correcion a los mugeres que la justicia condene a reclusion que puedan recogerse igualmente en el, aquellos cuya conducta relajada obliguen a las Autoridadas a separarlas de los vicios con que escandalisan la moral y buenas costumbres”. “Expediente sobre creación e instalación de una Junta de Beneficencia para en tender en todo lo concerniente a la casa del mismo nombre”, Fondo Municipios de San Juan, Legajo 26, Exp. 10, 1841. Archivo General de Puerto Rico. |

| 23 | See (Santiago-Valles 2006, pp. 33–57). For perspective on the ideological construction of race in space and time, see (Fields and Fields 2014). For the role of modern buildings in power relations, see (Markus 2013). For the role of racism in modern architectural theory, see (Cheng 2020). |

| 24 | “en lugar de individuos de color de las islas vecinas porque éstos inculcan a los demás su ideas de emancipación”. Archivo Histórico Nacional, Madrid. Ultramar, 1071, Exp. 37, 1842–1845. |

| 25 | “Importació de jornaleros canarios para la construcción”. Ibid. |

| 26 | While certain aspects of Michael Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power, emerging in eighteenth-century Europe, might be applicable to San Juan, the city’s unique colonial setting suggests a more complex relationship to his model than a simple derivative (Foucault [1977] 1995). Architectural historian Dell Upton’s analysis of the grid’s implementation, negotiation, and lived experience in the reformist context of the early United States republic challenges and extends conventional theories of eighteenth-century discipline, suggesting the formative role of American political and social contexts. See (Upton 2008). |

| 27 | The image also underscores the perceived connection between the physical city (“urbs”) and its human community (“civitas”), a Roman concept that Richard L. Kagan noted to be at work in the cities of the early modern Spanish world (Kagan and Marías 2000). |

| 28 | For a comparative case of Cuban elites projecting idealizations onto the city that distort its actual social makeup, see (Sepúlveda 2021). |

References

Primary Source

- Archivo Histórico Nacional, Madrid

- Expediente general de la Casa de Beneficencia de Puerto Rico, Ultramar, 5077, Exp. 38, 1841–1858.

- Denegado permiso de rifa de una estancia, Ultramar, 1077, Exp. 58, 1841.

- Plano y perfiles de la obra que se construye en Puerto Rico para establecimiento de Beneficencia, Ultramar, MPD, 1192, 1841.

- Importación de jornaleros canarios para la construcción, Ultramar, 1071, Exp. 37, 1842–1845.

- Proyecto de una Casa de Asilo o Establecimiento de Beneficencia para 256 personas de ambos secsos mandado ejecutar en esta Plaza de Puerto Rico pr. El Exmo. Señor Gobernador y Capitán Gral. Dn. Santiago Méndez de Vigo, Ultramar, MPD, 1191, 1843.

- Expediente general de la Casa de Beneficencia de Puerto Rico, Ultramar, 5077, Exp. 39, 1843–1846.

- Expediente general de la Casa de Beneficencia de Puerto Rico, Ultramar, 5077, Exp. 40, 1846–1851.

- Desestimada adjudicación de solares a Casa de Beneficencia, Ultramar, 1071, Exp. 45, 1848–1849.

- Se solicita la dirección de la Casa de Beneficencia, Ultramar, 5073, Exp. 11, 1848.

- Archivo General de Puerto Rico, San Juan

- Fondo Municipios de San Juan, Legajo 26

- Expediente sobre nombramiento de la Junta de Beneficencia, Exp. 2, 1822.

- Expediente formado por la Junta Municipal de Beneficencia en reclamación del Hospital de Caridad de Nuestra Señora de la Concepcion, Exp. 3, 1822.

- Expediente que contiene la copia impresa del expediente formado por la Junta Municipal de Beneficencia, en reclamación del Hospital de la Concepción, Exp. 4, 1822.

- Expediente sobre proyecto de Loteria presenta de por la Junta Municipal de Beneficencia, Exp. 7, 1823.

- Expediente sobre establecimiento de una Casa de Reclucion y Correccion, Exp. 8, 1838.

- Expediente instruido para el establecimiento en esta Capital, de una Casa de Reclusion y Beneficencia, Exp. 9, 1840.

- Expediente sobre creación e instalación de una Junta de Beneficencia para en tender en todo lo concerniente a la casa del mismo nombre, Exp. 10, 1841.

- Expediente que contiene las cartas de pago de los 4,000 que facilitó de Tesorería para emprender, la obra de la casa de Beneficencia, Exp. 11, 1841.

- Expediente que contiene el Decreto del Gobernador General haciendo extensión a toda la isla el arbitrio de un maravedí en libra de carne para la obra de la casa de Beneficencia, Exp. 12, 1844.

- Expediente que contiene el Estado general de los fondos de Beneficencia desde su creación hasta el 31 de Diciembre de 1844, Exp. 13, 1844.

- Expediente que contiene el arancel de los honorarios que deben cobrar los médicos, cirujanos y comadronas por su asistencia, Exp. 14, 1852.

- Fondo Obras Publicas, Serie Edificios Publicos, Legajo 106, caja 685.

- Contiene lo obrado acerca de la construcción de la Casa de Beneficencia, Exp. 2, 1840.

- Expediente formado a consecuencia de varias incidencias sobre la obra de la Casa de Beneficencia, Exp. 3, 1840.

- Recursos para la Casa de reclusion y beneficencia é incidents relativos, Exp. 4, 1841–1847.

- Printed Primary Sources

- Actas del Cabildo de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico, 1812–1814. Publicacion Oficial del Municipio de San Juan, Puerto Rico. Barce lona: M. Pareja, 1968.

- Actas del Cabildo de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico, 1815–1817. Publicacion Oficial del Municipio de San Juan, Puerto Rico. Barce lona: M. Pareja, 1968.

- De Goenaga, Francisco R. Desarrollo Histórico del Asilo de Beneficencia y Manicomio de Puerto Rico desde su creacion hasta 31 Julio 1929 y circulares relativas a hospitals (San Juan: Cantero Fernandez, 1929).

- Establecimiento, progresos y actual estado de la Casa de Beneficencia, extramuros de la Habana, en fin de Marzo de 1813. Habana Oficina de Arozoza y Soler, 1813.

- Gazeta de Puerto Rico. University of Florida Libraries.

Secondary Sources

- Baerga, María del Carmen. 2015. Negociaciones de Sangre: Dinamicas Racializantes en el Puerto Rico Decimononico. Madrid: Iberoamer cana Editorial Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Ballajá: Arqueología Histórica de un Barrio de San Juan. 2004. San Juan: Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras.

- Barnes, Mark. 1995. Ballajá: Arqueología de un Barrio Sanjuanero. San Juan: Oficina Estatal de Preservación Histórica. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline on a Theory of Practice. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Magali. 2003. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casella, Eleanor Conlin. 2007. The Archaeology of Institutional Confinement. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Maria de los Angeles. 1980. Arquitectura en San Juan de Puerto Rico, Siglo XIX. San Juan: Editorial Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Irene. 2020. Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory. In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II and Mabel O. Wilson. Pittsburgh: Univesity of Pittsburg Press, pp. 134–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Irene, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson, eds. 2020. Introduction. In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Jesús. 2003. The Plaza Mayor and the Shaping of Baroque Madrid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly, Katherine. 2019. An Archaeology of Lunacy: Managing Madness in Early Nineteenth-Century Asylums. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Karen E., and Barbara J. Fields. 2014. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, Eileen. 1999. Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870–1920. Durham and London: Duke Unversity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1978. Incorporación del hospital en la tecnología moderna. Educación Médica y Salud 12: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Godsden, Chris. 2004. Archaeology and Colonialism: Cultural Contact from 5000 BC to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfogel, Ramón. 2006. World-Systems Analysis in the Context of Transmodernity, Border Thinking, and Global Colonialty. Review 29: 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, Bill, and Julienne Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Heidi. 2001. Angels in the Architecture: A Photographic Elegy to an American Asylum. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, Jennifer. 2023. José María Morelos, Brownness, and the Visibility of Race in Nineteenth-Century Mexico. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 39: 302–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, Richard, and Fernando Marías. 2000. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. 2004. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbruner, Jay. 1996. Not of Pure Blood: The Free People of Color and Racial Prejudice in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1992. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- López-Durán, Fabiola. 2018. Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luque Azcona, José Emilio. 2020. Management and Transformation of Urban Spaces in San Juan de Puerto Rico during the Government of Miguel de la Torre (1823–1837). Culture & History 9: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Thomas A. 2013. Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vergne, Teresita. 1999. Shaping the Discourse on Space: Charity and its Wards in Nineteenth-Century San Juan, Puerto Rico. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matos Rodríguez, Felix V. 2001. Women in San Juan, 1820–1868. Princeton: Markus Wiener. [Google Scholar]

- Niell, Paul. 2014. Neoclassical Architecture in Spanish Colonial America: A Negotiated Modernity. History Compass 12: 252–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niell, Paul. 2023. No Taste for Thatching: Value, Aesthetics, and Urban Reform in the Bohíos of Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. In O Gusto Neoclássico: A Dimensão Americana. Edited by Ana Pessoa and Margareth da Silva Pereira. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa, pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pabón-Charneco, Arleen. 2010. La Arquitectura Patrimonial Puertorriqueña y sus Estilos. San Juan: Oficina Estatal de Conservación His tórica. [Google Scholar]

- Pabón-Charneco, Arleen. 2016. The Architecture of San Juan de Puerto Rico. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, Gabrielle, ed. 2009. Enlightened Reform in Southern Europe and its Atlantic Colonies, c. 1750–1830. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Anibal, and Michael Ennis. 2000. Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1: 533–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Valles, Kelvin. 2006. Bloody Legislations, ‘Entombment’, and Race Making in the Spanish Atlantic: Differentiated Spaces of General(ized) Confinement in Spain and Puerto Rico, 1750–1840. Radical History Review 96: 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, Asiel. 2021. Havana Impressions: Print Culture and Global Modernity in Plantation Cuba (1790–1860). Ph.D. dissertation, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shubert, Adrian. 1991. ‘Charity Properly Understood’: Changing Ideas about Poor Relief in Liberal Spain. Comparative Studies in Society and History 33: 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twinam, Ann. 2015. Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, Dell. 2008. Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yanni, Carla. 2007. The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. Minneapolis and London: University of Minne sota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziff, Katherine. 2012. Asylum on the Hill: History of a Healing Landscape. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niell, P.B. Designed Segregation: Racial Space and Social Reform in San Juan’s Casa de Beneficencia. Arts 2024, 13, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13050147

Niell PB. Designed Segregation: Racial Space and Social Reform in San Juan’s Casa de Beneficencia. Arts. 2024; 13(5):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13050147

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiell, Paul Barrett. 2024. "Designed Segregation: Racial Space and Social Reform in San Juan’s Casa de Beneficencia" Arts 13, no. 5: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13050147

APA StyleNiell, P. B. (2024). Designed Segregation: Racial Space and Social Reform in San Juan’s Casa de Beneficencia. Arts, 13(5), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13050147