Haunted Monasteries: Troubling Indigenous Erasure in Early Colonial Mexican Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Haunted Monastery

3. Indigenous Insiders

4. Spectral Topographies

5. Walking with the Ghost(s)

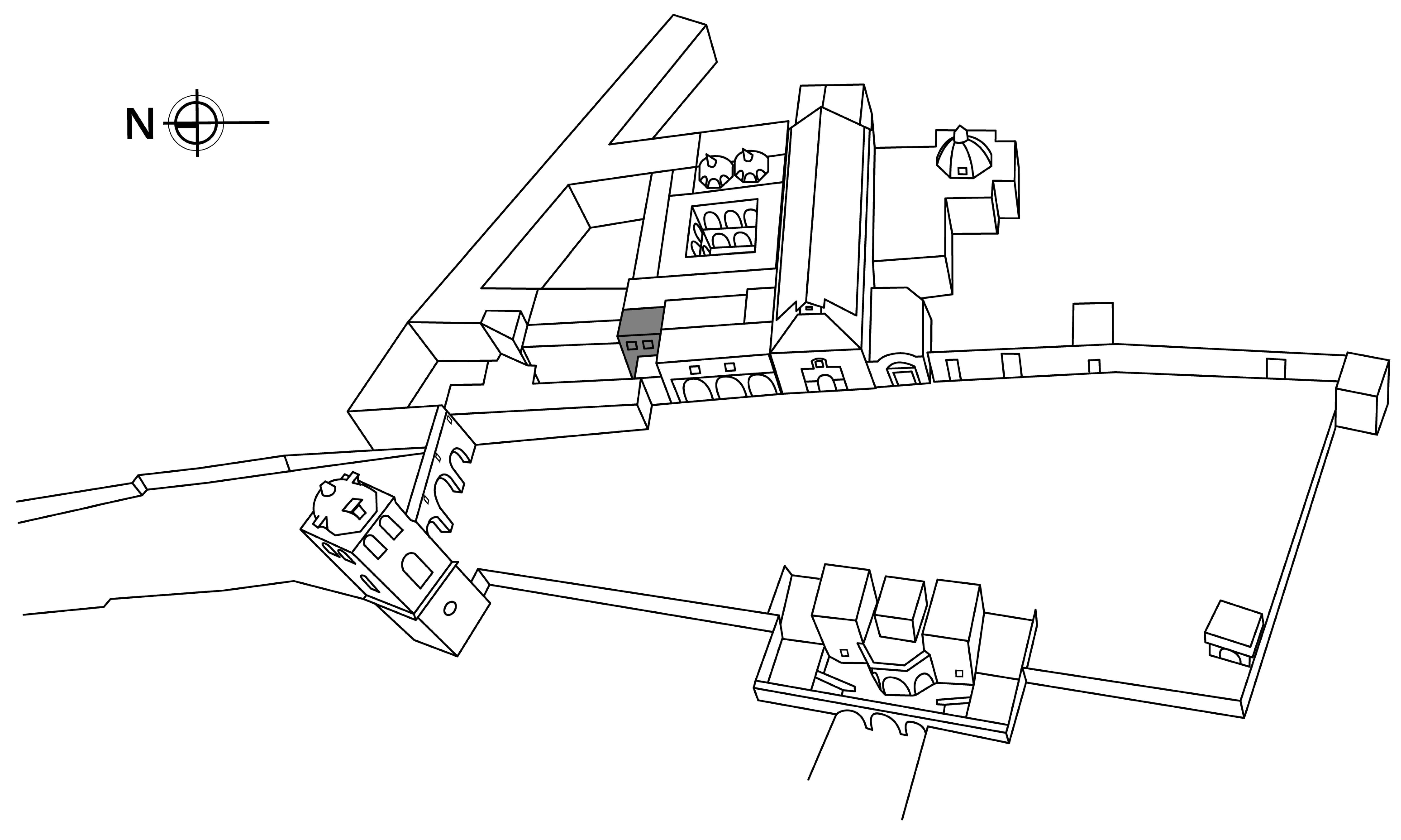

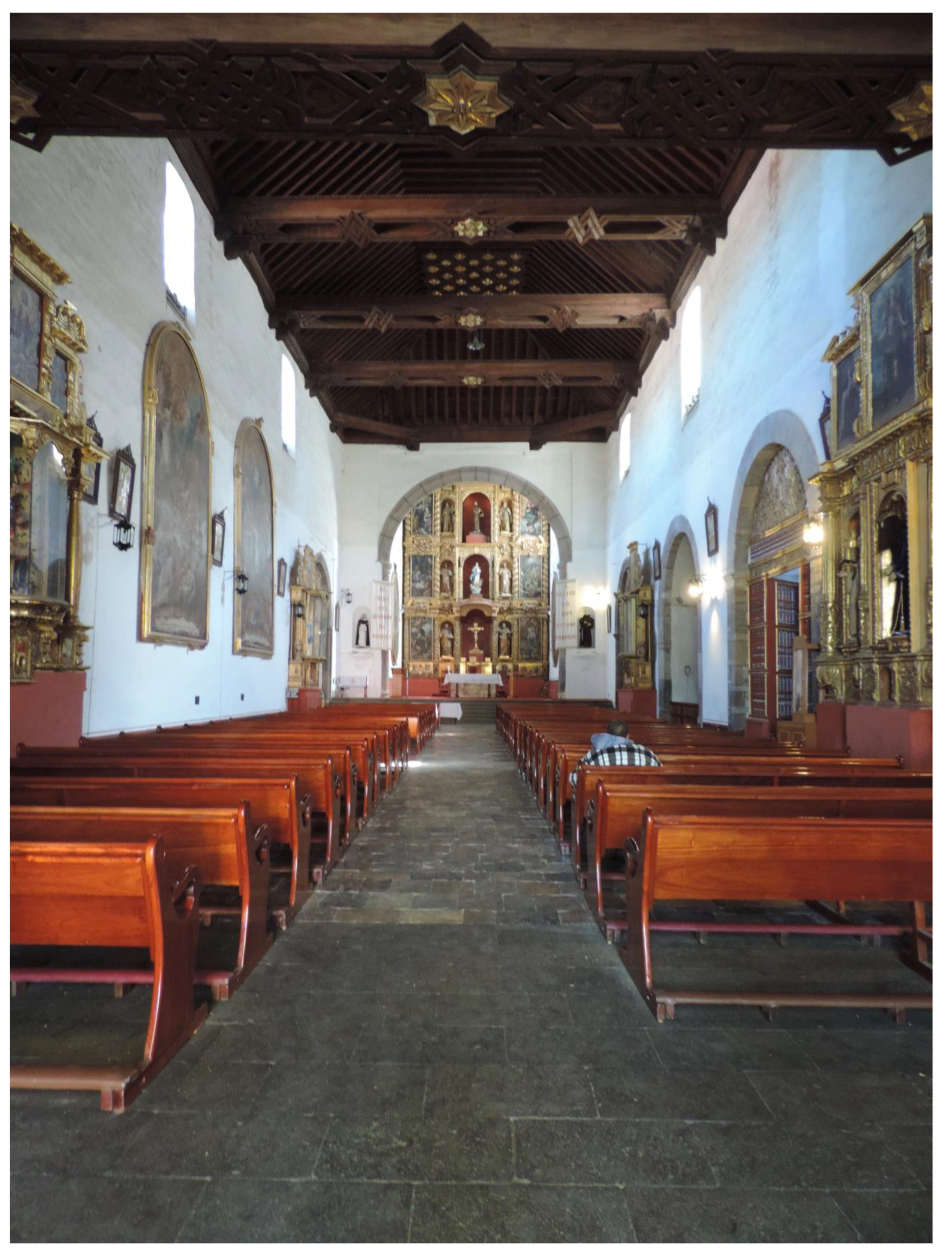

5.1. The Refectory

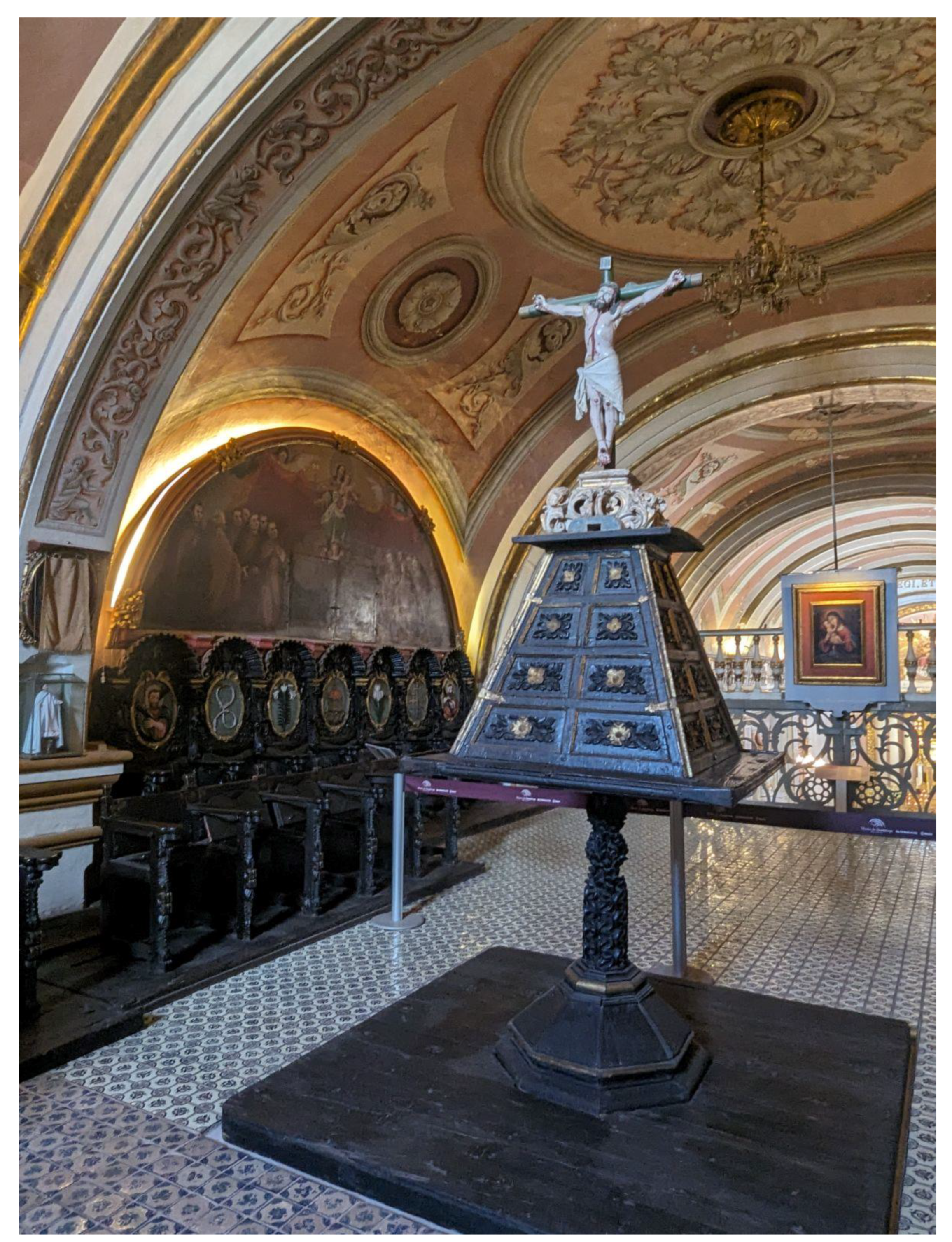

5.2. The Choir

5.3. The Cloister

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Although Mendieta’s chronicle was unpublished until 1870, the manuscript had circulated widely and was a key source for later Franciscan chroniclers (Torquemada 1975, pp. 407–9; Wauchope et al. 2014, pp. 145–46). |

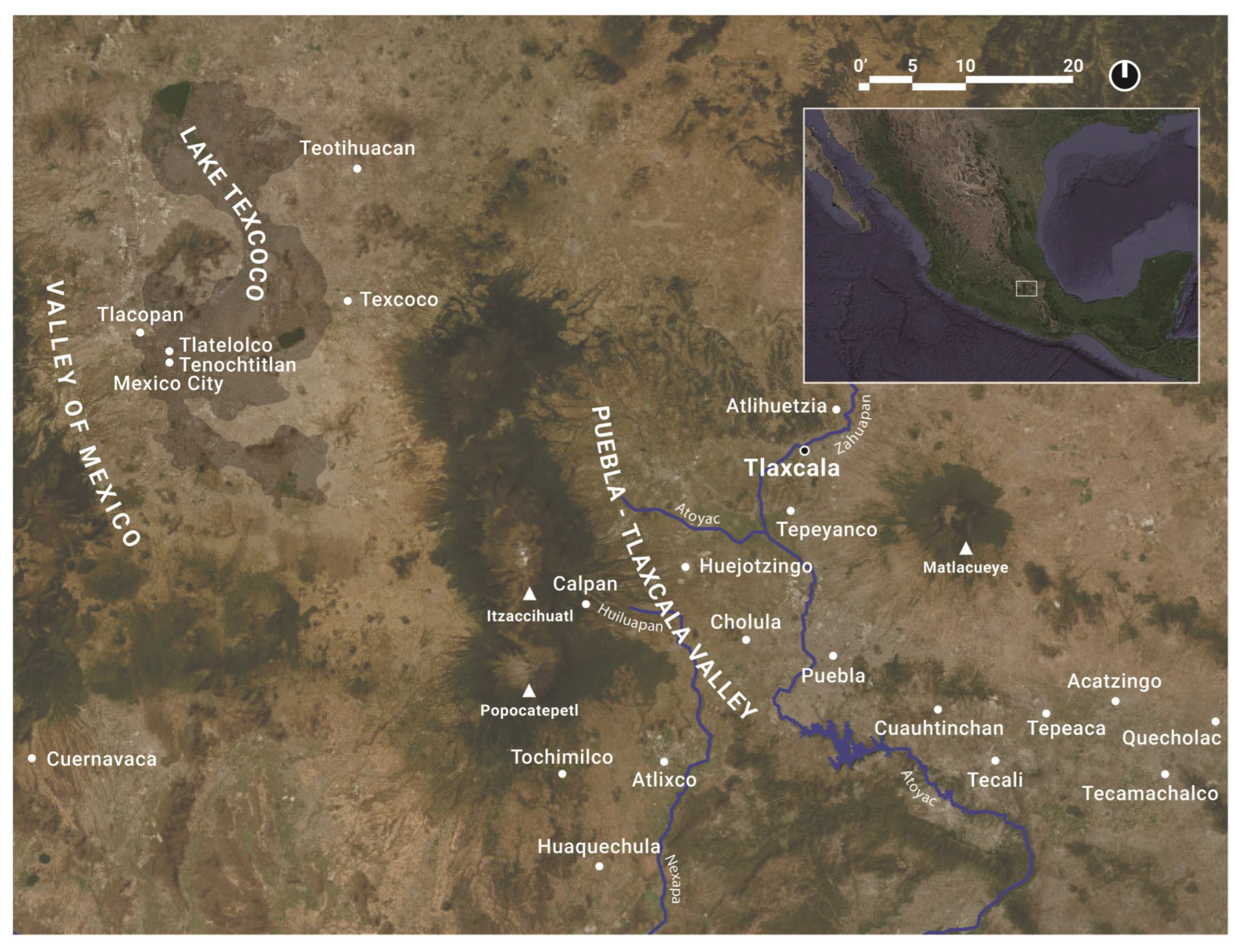

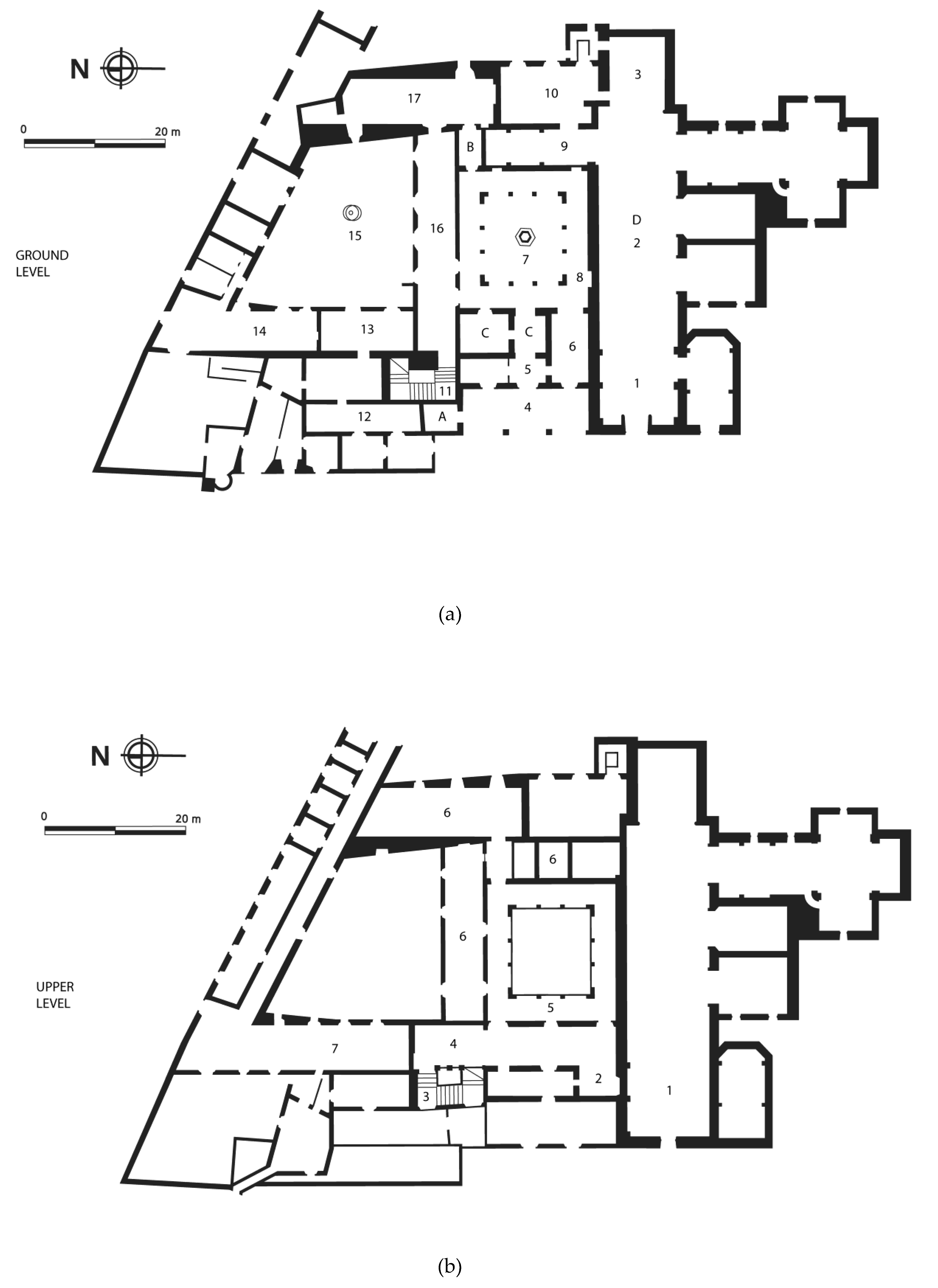

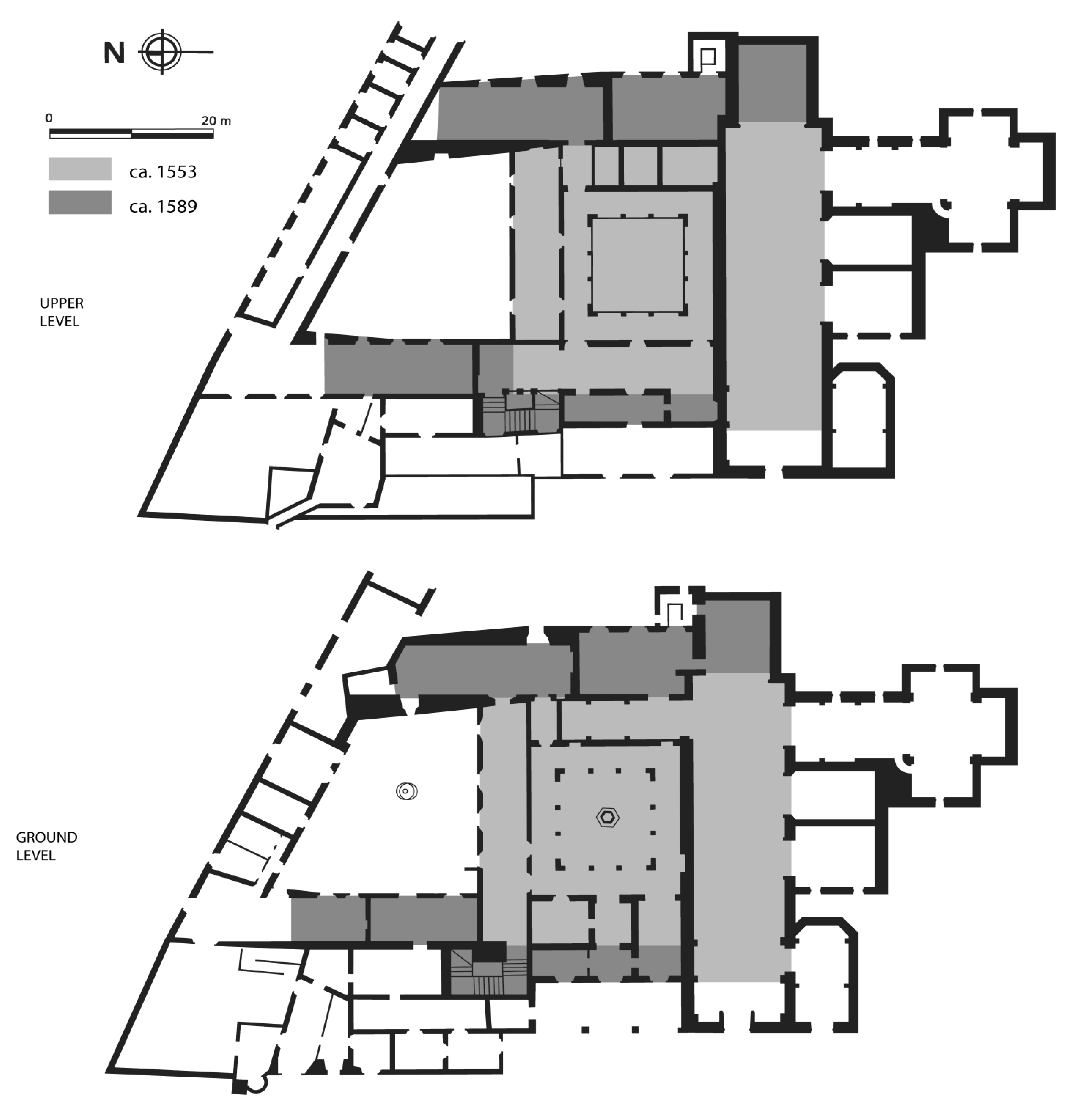

| 2 | Convent and monastery were essentially interchangeable in sixteenth century Central Mexico; I use monastery to reflect the terminology that appears in Nahuatl documents from Tlaxcala. For the early colonial history of Tlaxcala, see, especially, Gibson (1952); Martínez Baracs (2008); Cuadriello (2011). Leyva (2014) traces the stages of the monastery’s development. |

| 3 | For illusions and disbelief in purgatory discourses, see (Greenblatt 2013, pp. 76–77). |

| 4 | “rostro á rostro […] ¿No sois vos Fr. fulano, que es ya defuncto?” in (Mendieta 1997, vol. 2, pp. 140–41). Here, the author uses “so-and-so” or “fulano” to refer to the dead missionary, withholding the identity of the restless spirit to avoid heterodoxy. |

| 5 | “Sí, yo soy” (Mendieta 1997, vol. 2, p. 141). |

| 6 | On the Eucharist as a suffrage for the dead, see (Le Goff 1986, pp. 81, 93). |

| 7 | The episode in the choir also alludes to the tracts on discernment by theologian Jean Gerson, which Timothy Chesters has shown informed Catholic ideas about ghosts and apparitions in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (2011, pp. 26–35). |

| 8 | “¿Qué buscáis por acá, hermano? […] ¿Pues no veis lo que busco?” in (Mendieta 1997, vol. 2, p. 141). |

| 9 | Following Martínez, I use race as a shorthand for the complex set of discourses and practices used to classify and differentiate colonial subjects. |

| 10 | Encounters with unquiet souls were recorded, circulated, and recopied over the years, generating a corpus of documents that reflect the lived aspects of religion, as historians have shown (Le Goff 1986; Christian 1981). |

| 11 | Later renovations altered the original layout so that today, the north quadrangle has an irregular plan. |

| 12 | To reconstruct the experience of the liturgy, I draw on the following primary sources, listed in chronological order from 1523: (Carrión 1918, pp. 264–27; Gante 1981, f. 136r–161; Cargnoni 1995, pp. 224–28; García Icazbalceta 1941; Medrano 1579; Gonzaga 1585). |

| 13 | Records for the use of plainchant (canto llano) and polyphonic (canto de órgano) music books in the region’s Franciscan monasteries appear as early as 1557 and 1559 (Martínez 1984, pp. 58–59, 77). |

| 14 | https://gml.noaa.gov/grad/solcalc/sunrise.html, (accessed on 25 December 2019). |

| 15 | In Mendieta’s chronicle, “en la tarde” is after Vespers (around 2:30 p.m.) but before “prima noche” (sunset). |

| 16 | Compline marked the end of the liturgical day, and thus properly speaking, Fray Miguel met the spirit in the choir on Saturday, not Friday. |

| 17 | Friars and Nahua cantors may have sung Vespers for the Dead instead of a Requiem Mass. |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2007. A Phenomenology of Whiteness. Feminist Theory 8: 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadourian, Carlos Sempat. 1988. Memoriales de Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta. Historia Mexicana 37: 357–422. [Google Scholar]

- Baudot, Georges. 1990. La pugna franciscano por México. Mexico City: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Jill. 2001. Stigmata and Sense Memory: St. Francis and the Affective Image. Art History 24: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergland, Renée L. 2000. The National Uncanny: Indian Ghosts and American Subjects. Lebanon: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

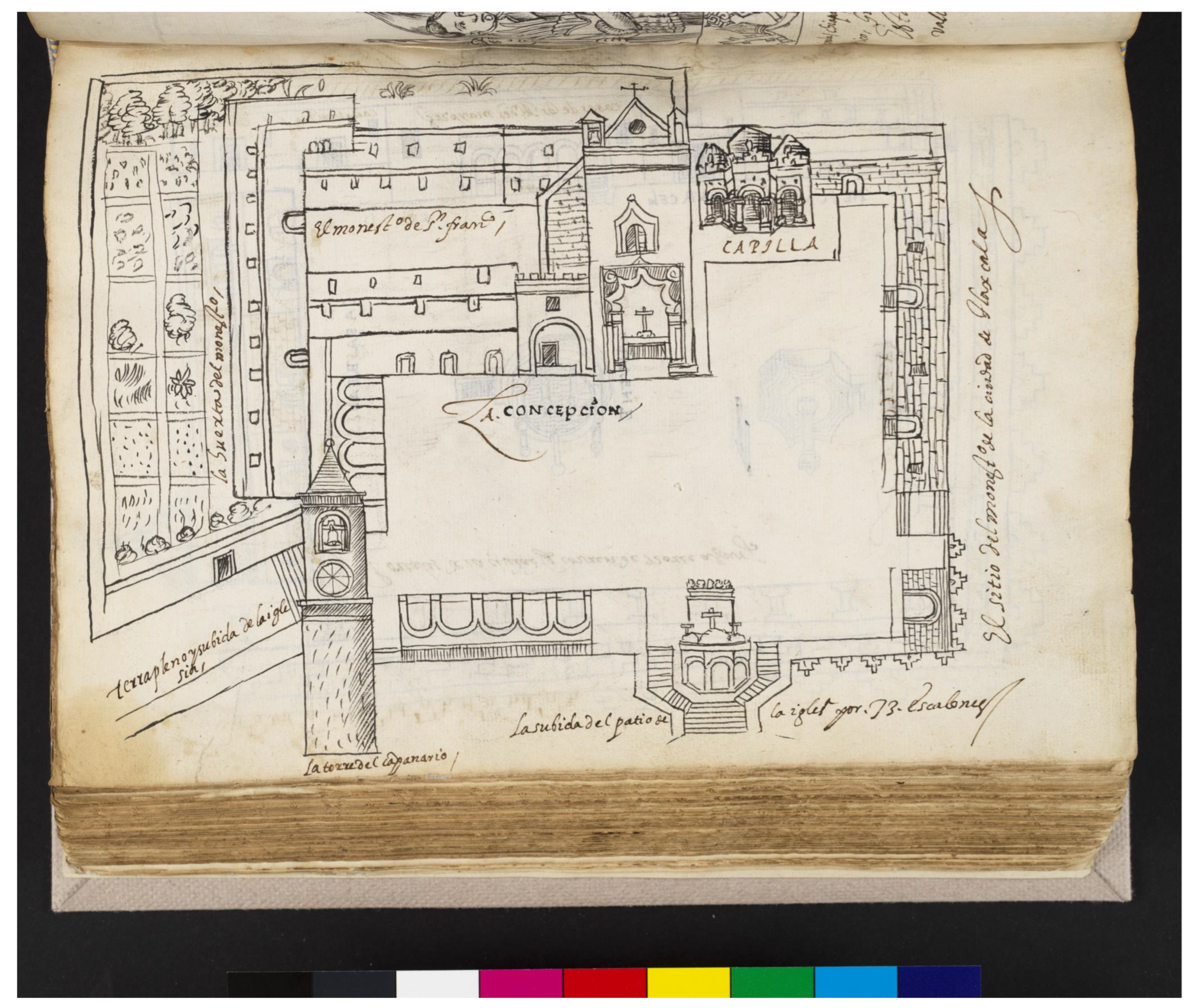

- Camargo, Diego Muñoz. 1981. Descripción de la ciudad y provincia de Tlaxcala de las Indias y del mar océano para el buen gobierno y ennoblecimiento dellas. Edited by René Acuña. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigación Filosóficas. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, Diego Muñoz. 1994. Suma y epíloga de toda la descripción de Tlaxcala. Edited by Andrea Martínez Baracs and Carlos Sempat Assadourian. Tlaxcala: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Emilie. 2008. Indigenous Spectrality and the Politics of Postcolonial Ghost Stories. Cultural Geographies 15: 383–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnoni, Costanzo. 1995. Houses of Prayer in the History of the Franciscan Order. In Franciscan Solitude. Edited by André Cirino and Josef Raischl. Translated by Nancy Celaschi. New York: The Franciscan Institute, pp. 211–64. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, Luis. 1918. Casa de Recolleción de la Provincia de la Inmaculada Concepción y estatuas por se regían. Archivo Ibero-Americano 5: 264–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda de la Paz, María. 2009. Central Mexican Indigenous Coats of Arms and the Conquest of Mesoamerica. Ethnohistory 56: 125–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, Eustaquio, Armando Valencia R., and Constantino Medina Lima. 1985. Actas de cabildo de Tlaxcala, 1547–1567. Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [Google Scholar]

- Chesters, Timothy. 2011. Ghost Stories in Late Renaissance France: Walking by Night. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, William A. 1981. Apparitions in Late Medieval and Renaissance Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad Real, Antonio de. 1993. Tratado curioso y doctor de las grandezas de Nueva España. Edited by Alonso de San Juan. Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma de México, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadriello, Jaime. 2011. Glories of the Republic of Tlaxcala. Art and Life in Viceregal Mexico. Translated by Christopher J. Follett. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Spectres of Marx. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Jesús. 2021. Architecture, Race, and Labor in the Early Modern Spanish World. Constructing Race and Architecture 1400–1800 (Part 1). Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80: 268–69. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, Savannah. 2020. Unsettling the Spiritual Conquest: The Murals of the Huaquechula Monastery in Sixteenth Century Mexico. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada de Gerlero, Elena. 2011. Muros, sargas y papeles: Imagen de lo sagrado y lo profano en el arte novohispano del siglo XVI. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández González, Laura. 2021. Architecture, the Building Trade, and Race in the Early Modern Iberian World. Constructing Race and Architecture 1400–1800 (Part 1). Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80: 388–90. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Edward. 2007. Franciscan Liturgical Prayer. In Franciscans at Prayer. Edited by Timothy J. Johnson. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 385–412. [Google Scholar]

- García Gómez, Lidia E., and Gustavo Mauleón Rodríguez. 2017. La magnificencia del culto litúrgico y devocional en los pueblos de indios del obispado de Tlaxcala, siglos XVI y XVII: Las capillas de música. In Miradas al patrimonio musical universitario. Solfas, letras, figuras y artilugios. Puebla: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- García Gutiérrez, Óscar Armando. 2014. Un convento franciscano en una ciudad de indios. Fundaciones previas y primeros procesos de edificacíon (1527–1538). In Tlaxcala: La invención de un convento. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- García Icazbalceta, Joaquín. 1892. Nueva colección de documentos para la historia de México. Mexico City: Francisco Díaz de León, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- García Icazbalceta, Joaquín. 1941. Nueva colección de documentos para la historia de México. Mexico City: Editorial Salvador Chávez Hayhoe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gante, Pedro de. 1555. Doctrina Christiana en lengua Mexicana. Mexico City: Pedro Balli. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Charles. 1952. Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godet-Calogeras, Jean François. 2007. Illi qui volunt religiose stare in eremis. Eremitical Practice in the Life of the Early Franciscans. In Franciscans at Prayer. Edited by Timothy J. Johnson. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 307–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, Francisco. 1585. Estatutos generles [sic] S. Francisco. Mexico City: Pedro Ocharte. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Avery. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 2013. Hamlet in Purgatory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, William F. 2010. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, John. 1991. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century. Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, Bill, and Julienne Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, Otto. 1993. The Responsories and Versicles of the Latin Office of the Dead. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koslofsky, Craig. 2011. Evening’s Empire: A History of Night in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kubler, George. 1948. Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrin, Asunción. 2014a. Dying for Christ: Martyrdom in New Spain. In Religious Transformations in the Early Modern Americas. Edited by Stephanie Kirk and Sarah Rivett. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrin, Asunción. 2014b. Los espacios de muerte. In Espacios en la historia. Invención y transformación de los espacios sociales. Edited by Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru. Mexico City: Colegio de México, pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 1986. The Birth of Purgatory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva, Alejandra González. 2014. De la arquitectura de la evangelización a la secularización y primera reconstrucción del templo. In Tlaxcala: La invención de un convento. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart, James. 1992. The Nahuas after the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart, James, Frances Berdan, and Arthur J. O. Anderson. 1986. The Tlaxcalan Actas: A Compendium of the Records of the Cabildo of Tlaxcala (1545–1627). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacCormack, Sabine. 1991. Religion in the Andes: Vision and Imagination in Early Colonial Peru. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Reinhold. 2020. Drawing the Color Line: Silence and Civilization from Jefferson to Mumford. In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis and Mabel Wilson. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Baracs, Andrea. 2008. Un gobierno de indios: Tlaxcala, 1519–1750. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Hildeberto. 1984. Tepeaca en el siglo xvi tenencia de la tierra y organización de su senorío. Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, María Elena. 2008. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, Laura E., and Michael R. Oudijk, eds. 2007. Indian Conquistadors: Indigenous Allies in the Conquest of Mesoamerica. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, John, ed. 1965. The Open-Air Churches of Sixteenth-Century Mexico: Atrios, Posas, Open Chapels, and Other Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medrano, Alonso de. 1579. Instrucción y arte [sic] del breviario. Mexico City: Pedro Balli. [Google Scholar]

- Mendieta, Gerónimo de. 1997. Historia eclesiástica indiana; obra escrita a fines del siglo XVI. Edited by Joaquín García Icazbalceta. Mexico City: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy, Barbara E. 2014. Extirpation of Idolatry and Sensory Experience in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. In Sensational Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 515–36. [Google Scholar]

- Olko, Justyna, and Agnieszka Brylak. 2018. Defending Local Autonomy and Facing Cultural Trauma: A Nahua Order Against Idolatry, Tlaxcala, 1543. Hispanic American Historical Review 4: 572–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roest, Bert. 2004. Franciscan Literature and Religious Instruction before the Council of Trent. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rubial García, Antonio. 1996. La hermana pobreza: El franciscanismo en la Edad Media a la evangelización novohispana. Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Nacional de México. [Google Scholar]

- Torquemada, Juan de. 1975. Monarquía indiana. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Camilla. 2016. The Annals of Native America: How the Colonial Nahuas Kept Their Histories Alive. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Truitt, Jonathan. 2018. Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenochtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1523–1700. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, Steven E. 2016. Franciscan Spirituality and Mission in New Spain, 1524–1599: Conflict Beneath the Sycamore Tree (Luke 19:1-10). Farnham: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, Dell. 1984. White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia. Places 2: 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Valadés, Diego de. 2013. Retórica cristiana. Translated by Tarsicio Herrera Zapién. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Vetancurt, Agustín de. 1982. Teatro Mexicano: Descripción breve de los sucesos ejemplares, históricos, políticos, militares y religiosos del nuevo mundo occidental de las Indias, 1698. Mexico City: Porrúa, vols. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Vicchio, Stephen J. 2006. The Image of the Biblical Job Volume Two: Job in the Medieval World. Eugene: Wipf & Stock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Villella, Peter B. 2016. Indigenous Elites and Creole Identity in Colonial Mexico, 1500–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff, Grayson. 2004. Morales’s Officium, Chant Traditions, and Performing 16th-Century Music. Early Music 32: 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, Eleanor. 2002. Codex Tlaxcala: New Insights and New Questions. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 33: 91–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wauchope, Robert, Howard F. Cline, and John Glass, eds. 2014. Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 13: Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources: Part 1 and 2. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Mabel O. 2020. Notes on the Virginia Capital: Nation, Race, and Slavery in Jefferson’s America. In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis and Mabel Wilson. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata y Mendoza, Juan Buenaventura. 1997. Historia cronológica de la noble ciudad de Tlaxcala [1662–1692]. Edited and translated by Luis Reyes García and Andrea Martínez Baracs. Tlaxcala: UAT CIESAS. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esquivel, S. Haunted Monasteries: Troubling Indigenous Erasure in Early Colonial Mexican Architecture. Arts 2024, 13, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020061

Esquivel S. Haunted Monasteries: Troubling Indigenous Erasure in Early Colonial Mexican Architecture. Arts. 2024; 13(2):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020061

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsquivel, Savannah. 2024. "Haunted Monasteries: Troubling Indigenous Erasure in Early Colonial Mexican Architecture" Arts 13, no. 2: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020061

APA StyleEsquivel, S. (2024). Haunted Monasteries: Troubling Indigenous Erasure in Early Colonial Mexican Architecture. Arts, 13(2), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020061