Housing the King’s Enslaved Workers in the Spanish Caribbean

Abstract

:1. Introduction

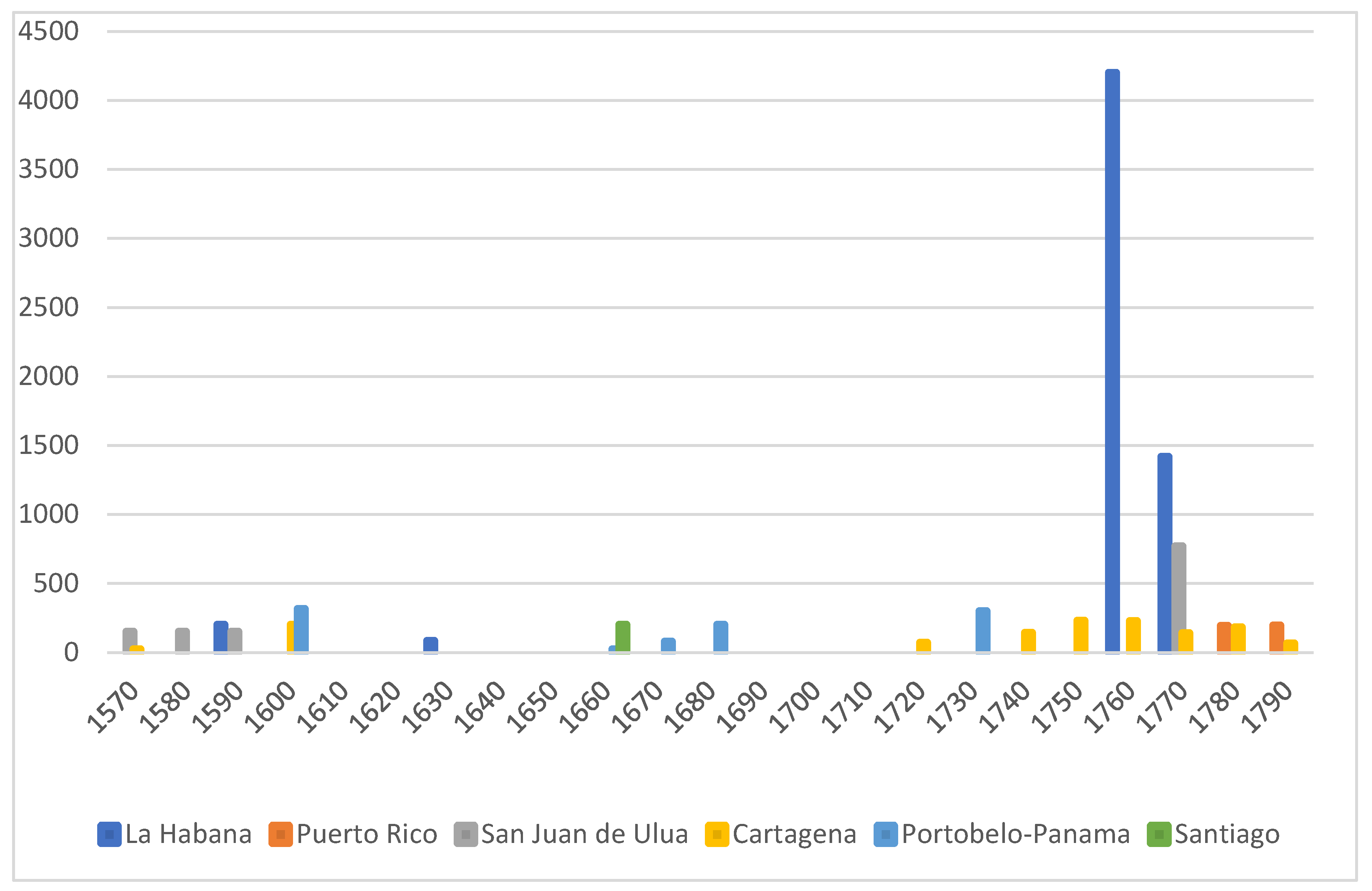

2. Workers in Numbers

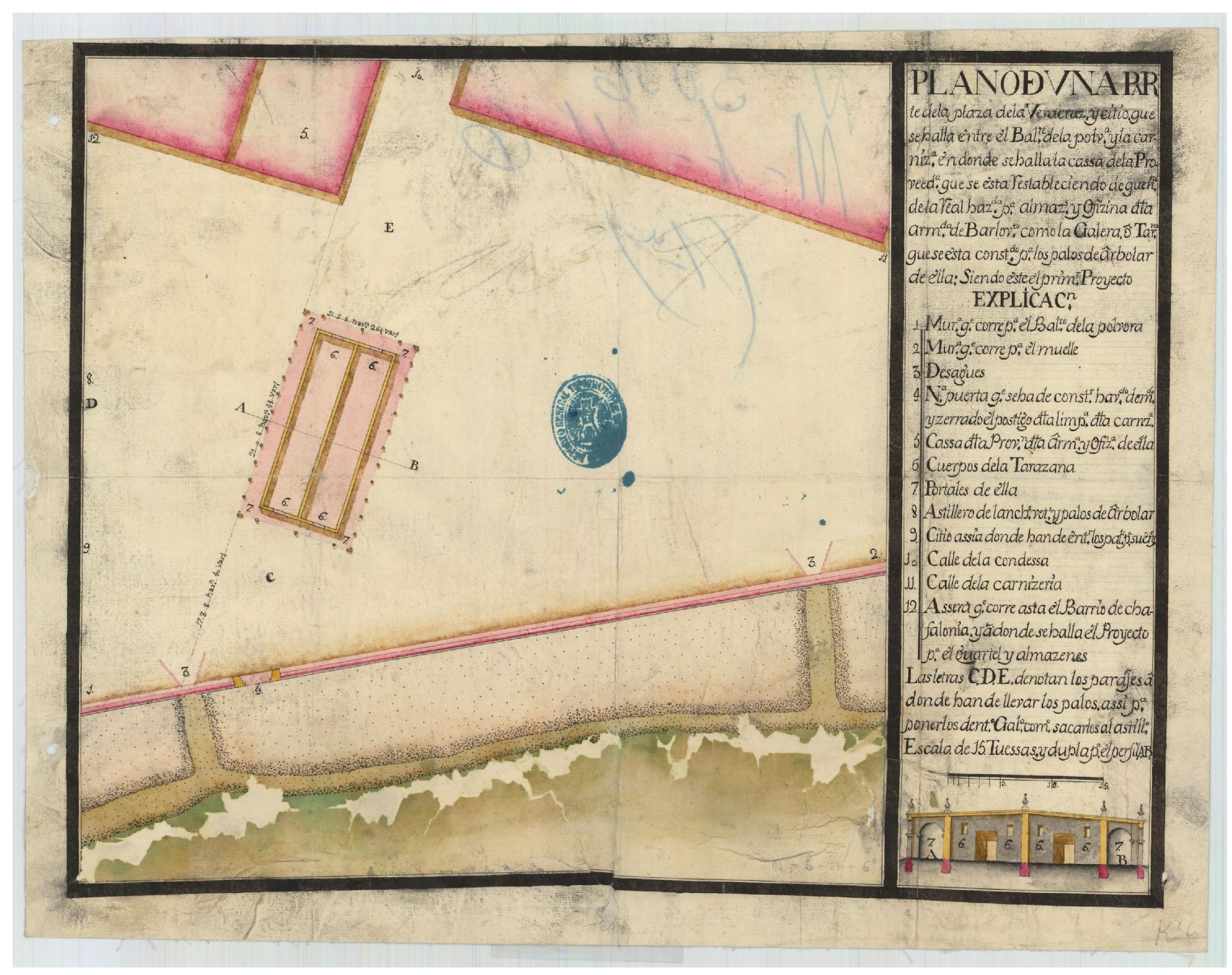

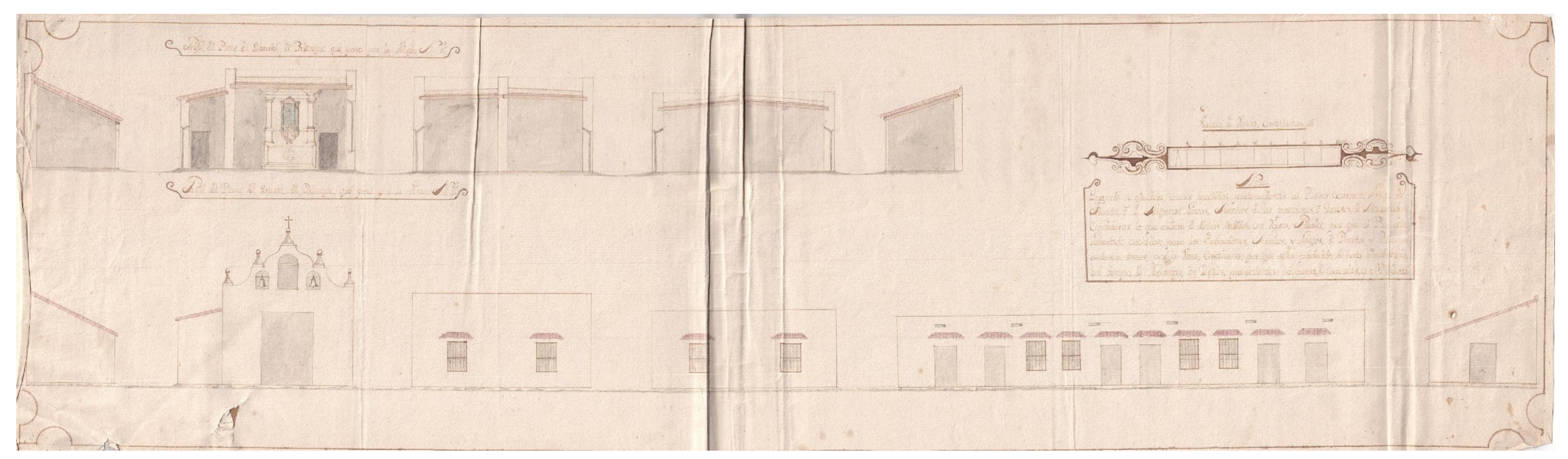

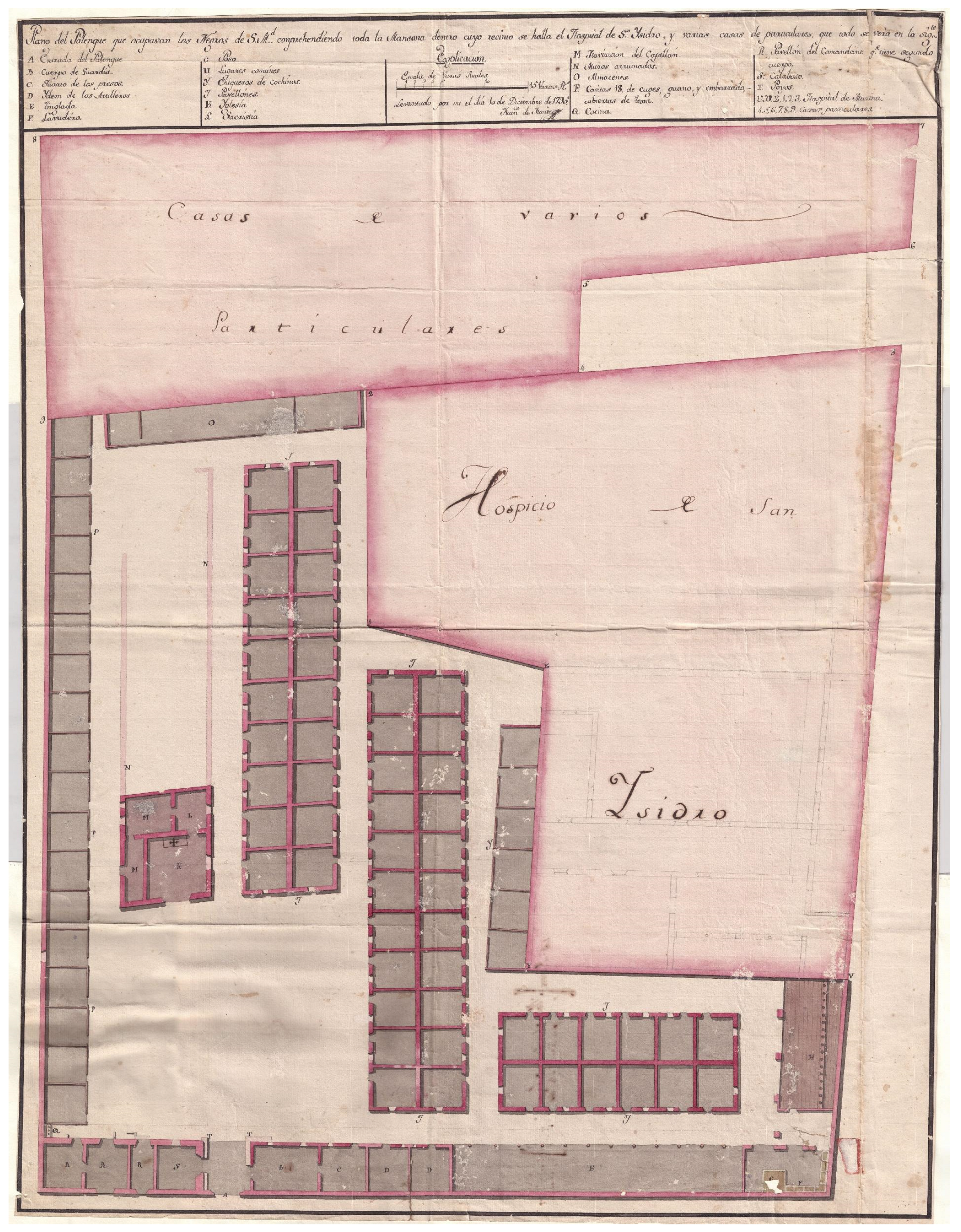

3. Housing Workers

4. A Black Overseer-Architect

5. Discussion

6. Materials and Methods

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this article the term “enslaved” will be used to denote those workers that are being acquired as slaves. In contrast, a forced laborer is one who committed a serious crime and was sentenced to forced labor. |

| 2 | This paper does not attempt to address other issues concerning the treatment of Africans, Americans, Europeans, and enslaved individuals in the Caribbean, including the physical transfers of peoples from community to community. |

| 3 | In 1573, 24 enslaved Africans were sent to Cartagena and Santa Marta. Cabildos seculares: Audiencia de Santa Fe. Esclavos para la fortificación. AGI, Santa Fe, 62, N. 35. 1585. |

| 4 | “Porque habiéndose de proseguir/las fortificaciones que están comenzadas en aque/lla tierra y llevado como lleváis oficiales can/teros, albañiles y carpinteros serán menester/peones os mando que de los negros que envían a Cartagena/o a cualquiera de los puertos de las dichas provincias/de tierra firme Pedro Gómez …. toméis los que precisamente fueren menester” (Because having to continue the fortifications that are begun in that land and carried out, as you are bringing officers, stonemasons, masons and carpenters, it will be necessary to have laborers, I command you, Pedro Gómez, to take what is precisely necessary of any of the Blacks that they send to Cartagena or to any of the ports of the said provinces from the mainland …). Esclavos para las fortificaciones. 1597. AGI, Panama, 237, L. 12, ff. 275v–276r. |

| 5 | Cédula al gobernador de Cuba para que informe si los esclavos que se encargan de la fortificación serían útiles para minería. 1573. AGI, Santo_Domingo, 1122, L. 5, ff. 8v–9r. Something similar is found in Sobre aplicación de los seis negros de la barca real a las fortificaciones. 1620. AGI, Santa Fe, 52, N. 155. |

| 6 | Testimonio sobre la fuga de once esclavos negros de las obras de fortificación. 1602. AGI, Panama, 15, R. 3, N. 31. |

| 7 | AGI, México, 257. Something similar was already studied for other contexts such as haciendas (Pineda Alillo 2014). |

| 8 | Envío de esclavos de las obras de La Habana a Cartagena. 1607. AGI, Santo_Domingo, 869, L. 5, ff. 149v–150r. |

| 9 | Envío de Cristóbal de Roda y los negros necesarios para las obras de fortificación de Cartagena. 1608. AGI, Santo_Domingo, 869, L. 5, ff. 196r–197v. |

| 10 | Cuenta de los esclavos y forzados del Rey. AGI, Contaduría, 1117. |

| 11 | Cuenta de los esclavos y forzados del Rey. 1636–1639. La Habana. AGI, Contaduría, 1118, ff. 89–109. |

| 12 | “Ordeno por auto de sin embargo que se comprasen veinte y cuatro piezas de esclavos de unos navíos de arribada que llegaron a Portobelo y que solo fueron veinte y dos que se hallaron a propósito cuyo precio se ajustó en nueve mil novecientos y cincuenta y dos pesos” (However, he ordered that twenty-four pieces [sic] of slaves be purchased from some arrival ships that arrived in Portobelo and that there were only twenty-two that were found for that purpose, whose price was adjusted to nine thousand nine hundred and fifty-two pesos). Compra de esclavos para las obras públicas. AGI, Panama, 230, L. 5, ff. 227v–228v. 1661. This governmental purchase seems to continue without significant additional information for this investigation here: Reintegro a la caja real del importe de ciertos esclavos para las fortificaciones de Portobelo. AGI, Panama, 230, L. 5, ff. 206r–207r. 1661. |

| 13 | Solicitud de doce mil pesos para comprar esclavos negros para la fortificación de Chagres. AGI, Panama, 231, L.8, ff. 171r–171v. |

| 14 | “Formándolos un pueblo en que tenían mucha conveniencia y puniendoles capellán que los doctrinase les sirvió esto de ocasión para que entrando en alhuez y en un modo de servicio soberbio que introduciéndose poco a poco por espacio de cinco años se reconoció imposible de corregir por cuya causa y por el gasto de más de siete mil pesos que hacían todos los años a mi real hacienda en su sustento y vestuario y que con esta cantidad rebajadas las quiebras de los enfermos y de los dias de fiesta en que no se trabaja podían alquilarse casi otros tantos negros jornaleros se tuvo por conveniente en juntas de hacienda el venderlos referidos con sus familias esclavas y puesto en ejecución por el justificado camino que manifiestan los papeles de estas materias“ (Creating a town for them in which they were very convenient and providing them chaplains who indoctrinate them served as an opportunity for them to enter into “alhuez” and into a superb mode of service that, introducing them little by little for a period of five years, was recognized as impossible to correct for whose cause and for the expense of more than seven thousand pesos that they made every year to my royal estate in their sustenance and clothing and that with this amount reduced bankruptcies of the sick and of the holidays in which they do not work they could rent almost as many Black day laborers it was considered convenient among the boards of finance to sell them referred to their slave families and put into execution by the just manner that the papers of these matters manifest). Motivos para vender esclavos negros de la Real Hacienda trabajando para la fortificación de Panamá. AGI, Panama, 231, L. 8, ff. 222r–223r. |

| 15 | Project about the reconstruction of the fortress of San Felipe at Portobello and San Lorenzo el Real at Chagre (Panama). 1741. Archivo General Militar de Madrid (AGMM) 5-2-5-2. |

| 16 | Ibid. |

| 17 | Something similar was found by Vila Villar (1985). |

| 18 | Project about the reconstruction of the fortress of San Felipe at Portobello and San Lorenzo el Real at Chagre (Panama). 1741. Archivo General Militar de Madrid (AGMM) 5-2-5-2. |

| 19 | Correspondencia del Capitán General de Cuba. AGI, Cuba, 1151, f. 650r. |

| 20 | Correspondencia del Capitán General de Cuba. AGI, Cuba, 1152, f. 212. |

| 21 | March: AGI, Cuba, 1152, f. 219; April: AGI, Cuba, 1152, f. 242; May: AGI, Cuba, 1152, f. 262, etc. |

| 22 | Relación de negros forzados que trabajan en la fortificación. 1775–1777. AGI, Cuba, 1155. |

| 23 | Relación de los esclavos remitidos a las obras de fortificación de esta plaza. AGI, Estado, 1, N. 23. |

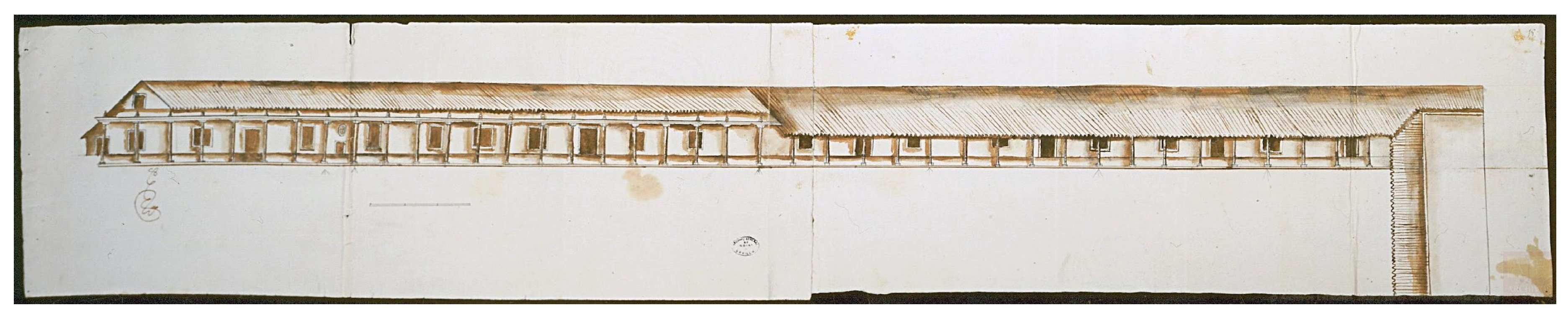

| 24 | “Testimonio del expediente promovido sobre composición de la casa de vivienda del sobrestante mayor de Casa Blanca y galera de forzados negros de su majestad, año 1804”. AGI, Santo_Domingo,1685, N. 500. |

| 25 | “Y sus colgadizos hasta poner dicha fábrica con la mayor solidez por hallarse en el día desplomados sus techos y apuntalados para contener la ruina que amenaza y se ha empezado a experimentar” (And its hangings until putting said factory with the greatest solidity because its roofs were collapsed during the day and propped up to contain the ruin that threatens and has begun to be experimented with). Ibid., f. 1r. |

| 26 | Budget of November 8th, 1801. Ibid., f. 15v. |

| 27 | Ibid., ff. 29v-30r. |

| 28 | Ibid., f. 31r-32r. |

| 29 | “conseguirse la claridad y ventilación de la galera que es tan necesaria para su beneficio y duración y para la salud de sus habitantes por ser un paraje de bastante humedad” (to achieve the clarity and ventilation of the galley that is so necessary for its benefit and duration and for the health of its inhabitants because it is a place with a lot of humidity). Ibid., f. 33r |

| 30 | Letter about the Royal Decree appointing Jose Maria Ceben as overseer. 1804. AGI, Santo_Domingo, 1685, N. 405. El intendente de ejército interino de La Habana. Contestando la Real orden de 17 de julio último sobre la colocación de José María Ceben en plaza de sobrestante, dice que este individuo es mulato, que los que sirven iguales destinos son personas blancas y de calidad, y pide que su Majestad se sirva suspender los efectos de su citada real orden. Excelentísimo señor. José María Ceben a quien su Majestad se sirvió mandar por real orden de 17 de julio último se le confiriera la primera vacante de sobrestante con el sueldo de doce reales diarios siendo ciertos sus servicios, y teniendo las demás cualidades que previenen las leyes, no existe en esta ciudad, pero es constante que en 12 de julio de 1778 se alistó en el batallón de pardos libres de esta plaza, y en la revista de inspección parada en diciembre de 1791 se // le dio la respectiva licencia por enfermo. Los empleos de sobrestantes de obras de fortificación, y de intervención de Real hacienda son de reglamento, y en la actualidad no hay vacante. Son servidos por personas blancas y de calidad en razón de ser destinos de suma confianza y la clase de mulato de José María Ceben me parece lo inhabilita para confiarle encargos de intereses de la Real Hacienda y de la alternativa que necesariamente tendría que guardar con los demás compañeros a la inmediación de jefes de // distinguido carácter. Enterado Vuestra Excelencia de las circunstancias de Ceben, le suplico se digne hacerlas presentes a Su Majestad y prevenirme lo que fuera de su soberano agrado en orden a la colocación de este individuo en el caso de que parezca y se me presente. Dios guarde a Vuestra excelencia muchos años. Habana, 20 de enero de 1804. Excelentísimo señor, Juan José de la Hoz (rúbrica). The interim army quartermaster of Havana. Responding to the Royal order of July 17th regarding the placement of José María Ceben in the position of foreman, he says that this individual is a mulatto, that those who serve the same destinations are white people of quality, and asks that His Majesty please suspend the effects of his aforementioned royal order. Your Excellency sir. José María Ceben, to whom His Majesty was pleased to order by royal order of last July 17th, that he be granted the first vacancy for overseer with the salary of twelve reales per day, his services being specific, and having the other qualities that the laws provide, does not exist in this city, but it is constant that on July 12, 1778, he enlisted in the free pardo battalion of this place, and at the inspection parade in December 1791 // he was given the respective sick leave. The jobs of overseers of fortification works, and intervention of the Royal Treasury are by regulation, and currently there are no vacancies. They are served by white and quality people because they are highly trusted destinations and José María Ceben’s class of mulatto seems to me to disqualify him from being entrusted with assignments of note from the Royal Treasury and the alternative that he would necessarily have to stay with the others‘ companions in the vicinity of bosses of // distinguished characters. When Your Excellency is aware of the circumstances of Ceben, I beg you to deign to present them to His Majesty and advise me of whatever is to your sovereign’s liking to place this individual in the event that he appears and presents himself to me. God keep Your Excellency many years. Havana, January 20, 1804. His Excellency, Juan José de la Hoz (signature). |

| 31 | Expediente de José María Seben. 1809. AGI, Ultramar, 327, N. 27. |

References

- Adán Castaños, Yeni Yeisi, ed. 2021. Construcciones palafíticas en Cuba. In Contrapunteo: El camino del Patrimonio Cultural en la Mayor de las Antillas. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide, pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Castillero Calvo, Alfredo. 2016. Portobelo y el San Lorenzo del Chagres. Perspectivas Imperiales. Siglos XVI-XIX. Panamá: Editora Novo Art. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Freire, Pedro. 2013. El gobernador Esteban Olóriz y el proyecto de reforma para el castillo del Morro de Santiago de Cuba (1767–1771). Revista de la CECEL 13: 139–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Freire, Pedro. 2018. Silvestre Abarca. Un ingeniero Militar al Servicio de la Monarquía Hispana. Sevilla: Athenaica. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Freire, Pedro, Manuel Gámez Casado, Ignacio J. López Hernández, Pedro Luengo, and Alfredo J. Morales. 2020. Estrategia y Propaganda. Arquitectura militar en el Caribe (1689–1748). Roma: L’Erma di Breitschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza Pérez, Alina, and Raquel Carreras Rivery. 2014. Maderas de La Habana colonial. Anales del Museo de América 22: 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Natalie Zemon. 2011. Decentering History: Local Stories and Cultural Crossings in a Global World. History and Theory 50: 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez Casado, Manuel. 2021. Ingeniería militar y en el Nuevo Reino de Granada. Defensa, poder y Sociedad en el Caribe sur (1739–1811). Madrid: Silex. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 1990. Resonance and Wonder. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 43: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinarejos Martín, Nuria. 2020. El Sistema de defensas de Puerto Rico (1493–1898). Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Evelyn P. 2020. Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762–1835. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes dos Santos, Ynaê. 2017. La Habana Bourbônica. Reforma ilustrada e escravidão em Havana (1763–1790). Revista de Indias 77: 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Hernández, Ignacio J. 2019. Ingeniería e ingenieros en Matanzas. Defensa y obras públicas entre 1693 y 1868. Seville: Athenaica. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, Pedro, ed. 2022. Ulúa. El Fuerte que Circunda el Mar. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Paolo Solano, Sergio, Muriel Vanegas Beltrán, and Dianis Hernández Lugo. 2021. Labores y vida urbana de los esclavos particulares y del rey en Cartagena de Indias, 1750–1810. El Taller de La Historia 13: 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Guzmán, Francisco. 1990. Modo de vida de esclavos y forzados en las fortificaciones de Cuba: Siglo XVIII. Anuario de Estudios Americanos 47: 241–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Guzmán, Francisco. 1992. Las fuentes que financiaron las fortificaciones de Cuba. Tebeto: Anuario Histórico Insular de Fuerteventura 5: 363–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda Alillo, J. 2014. Esclavos de Origen Africano en las Haciendas Jesuitas del Colegio de Tepotzotlán y de la Hacienda de Xochimancas del Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, siglo XVII. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Facultad de Estudios Superiores Acatlán. [Google Scholar]

- Pinillo León, Lisset. 2017. Proyecto Balcón. Revitalización del patrimonio histórico-cultural en la comunidad de Casa Blanca, en La Habana. Fuentes 11: 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schiebinger, Londa. 1998. Lost Knowledge, Bodies of Ignorance, and the Poverty of Taxonomy as Illustrated by the Curious Fate of Eios Pavonis, an Abortifacient. In Picturing Science and Producing Art. Edited by Caroline Jones and Peter Galison. London: Routledge, pp. 125–44. [Google Scholar]

- Solana, Sergio Paolo. 2020. Sistemas defensivos y trabajadores en Cartagena de Indias, 1750–1810. In Inmigración, Trabajo, Movilización y Sociabilidad Laboral. México y América Latina. Siglos XVI al XX. Edited by Sonia Pérez Toledo. Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, pp. 99–172. [Google Scholar]

- Soraluce Blond, J. R. 2003. El bohío cubano: Arquitecturas de cubierta vegetal en el Caribe. El Pajar. Cuaderno de Etnografía Canaria 14: 144–47. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas Delgado, Hernán Maximiliano. 2015. Esclavos indios del Norte novohispano hacia La Habana, Cuba (fines del siglo XVIII a inicios del siglo XIX). Antecedentes y resultados. Meyibó 9: 7–52. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas, H. M., J. J. Casas, and J. D. Martínez. 2016. Fortificaciones de La Habana y esclavos indios novohispanos (1763 a 1821). In La región, una y múltiple: Teoría y praxis historiográfica. El noreste de México, T.I. Edited by H. M. Venegas, A. Correa, A. Acosta, C. M. Valdés and J. J. Hernández. Teresina: Edufpi, pp. 167–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal Prades, Emma Dunia. 2010. Urbanismo de Guerra: Fortificaciones, reglamentación y embellecimiento de La Habana (1786–1799). Millars 33: 213–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vila Villar, Enriqueta. 1985. Posibilidades y perspectivas para el estudio de la esclavitud en los Fondos del Archivo General de Indias. Archivo Hispalense 68: 255–72. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luengo, P. Housing the King’s Enslaved Workers in the Spanish Caribbean. Arts 2023, 12, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060245

Luengo P. Housing the King’s Enslaved Workers in the Spanish Caribbean. Arts. 2023; 12(6):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060245

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuengo, Pedro. 2023. "Housing the King’s Enslaved Workers in the Spanish Caribbean" Arts 12, no. 6: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060245

APA StyleLuengo, P. (2023). Housing the King’s Enslaved Workers in the Spanish Caribbean. Arts, 12(6), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060245