Colonial Carpenters: Construction, Race, and Agency in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th and 17th Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Race and Carpentry in the Viceroyalty of Peru

2. The Carpenter: A Definition

3. Agency and Race: Limits in the Practice of Carpentry

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | ‘Y es de mucho de advertir, que los maestros de acá le aventajá a los de Europa en esta genialidad […] el carpintero [español] que haze escaños, no haze puertas ni ventanas, pero acá en el Pirú son generales los maestros y universales las formas y las ideas’. |

| 2 | While the concept of race may not align precisely with the social reality of early modernity, it can serve as a useful tool for understanding the categories constructed by Western societies to individualize and generalize individuals based on physical and moral characteristics that are believed to be inherited across generations (Hering 2007; Schaub and Sebastiani 2021). This led to the development of a taxonomy that, particularly in the Ibero-American context, relied on categories such as ‘quality’, ‘caste, ‘race’, ‘blood’, ‘nation’, ‘color’, and ‘condition’ (Zuniga 1999; Fisher and O’Hara 2009; Hering 2011; França Paiva 2020). In this article, I employ it to nuance our perspective on race in the 21st century. In other words, I use it as a concept that is not linked solely to skin color but also consider it as a condition of labor coercion inherent in the practice of colonial carpentry. In this context, I align myself with Cohen-Suarez’s clarification when she adapts the concept to race for a particular analysis: race and visual codification of identity in colonial Andes (Cohen-Suarez 2015, p. 187). |

| 3 | This type of publication had been utilized previously by other historians (Gestoso y Pérez 1899–1909; Llaguno y Amírola and Ceán Bermúdez 1829). |

| 4 | The term “constructive culture” encompasses the notable prevalence of a particular material stemming from its acknowledgment, selection, and mastery. This material is utilized to generate functional, constructional, and structural solutions that address the challenges posed by the natural environment (Jorquera 2014, p. 31). |

| 5 | One of the notable differences between the Spanish guilds, especially the Castilians ones, and those in colonial Peru, is their relationship with the municipal government. In colonial Peru, the guilds experienced greater interference due to agreements aimed at safeguarding guild privileges, as seen in the case of carpenters in Lima. In Castille, however, the relationship was not always one of dependence. While the autonomy of guilds in medieval Spanish origins depended on municipal power, guild operations were primarily self-managed. This is evident in the ordinances of Seville (1527), which merely documented the established guild structure as an attempt by the Crown to exert control, but without fundamentally altering their traditional operation (Mamani-Fuentes 2023). |

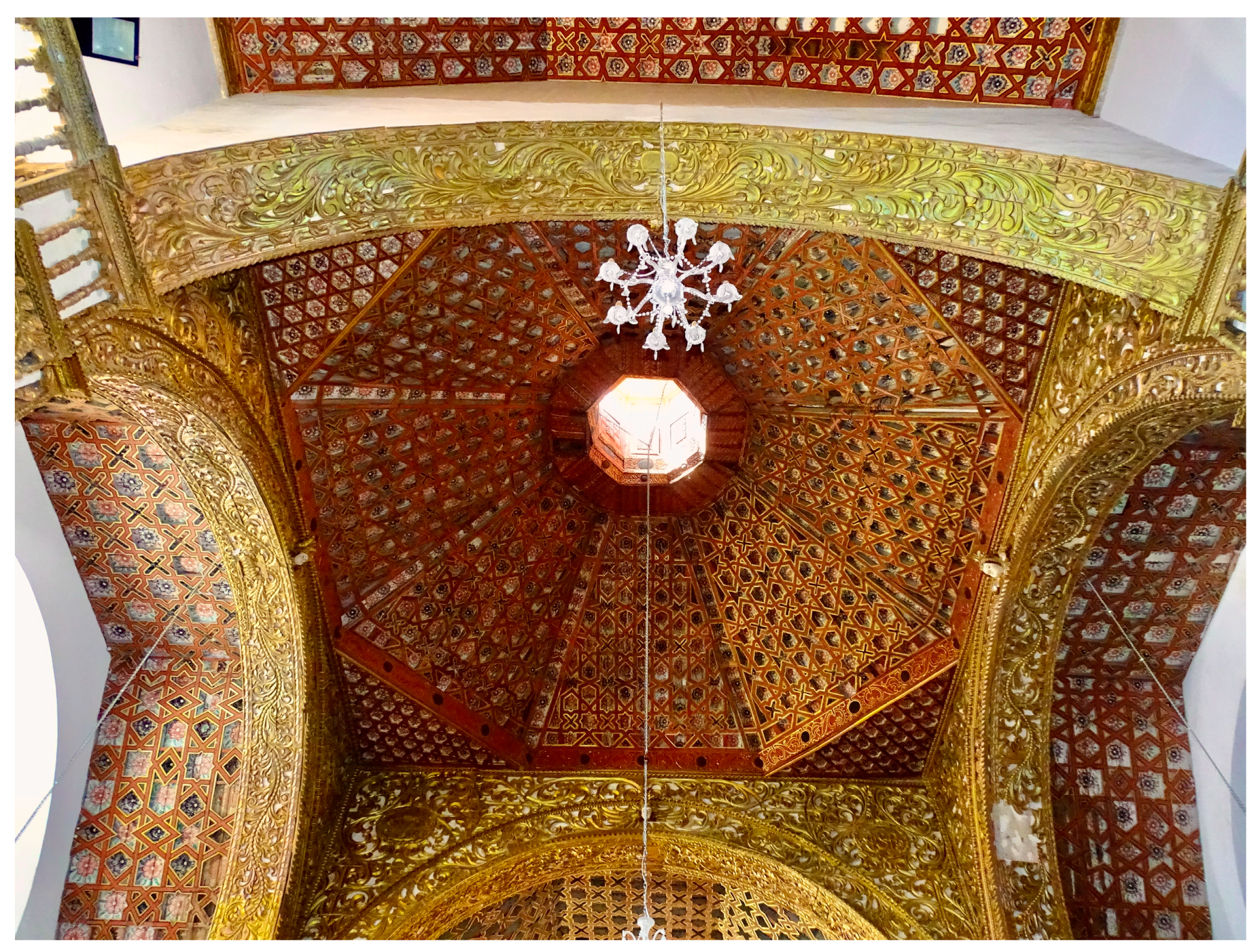

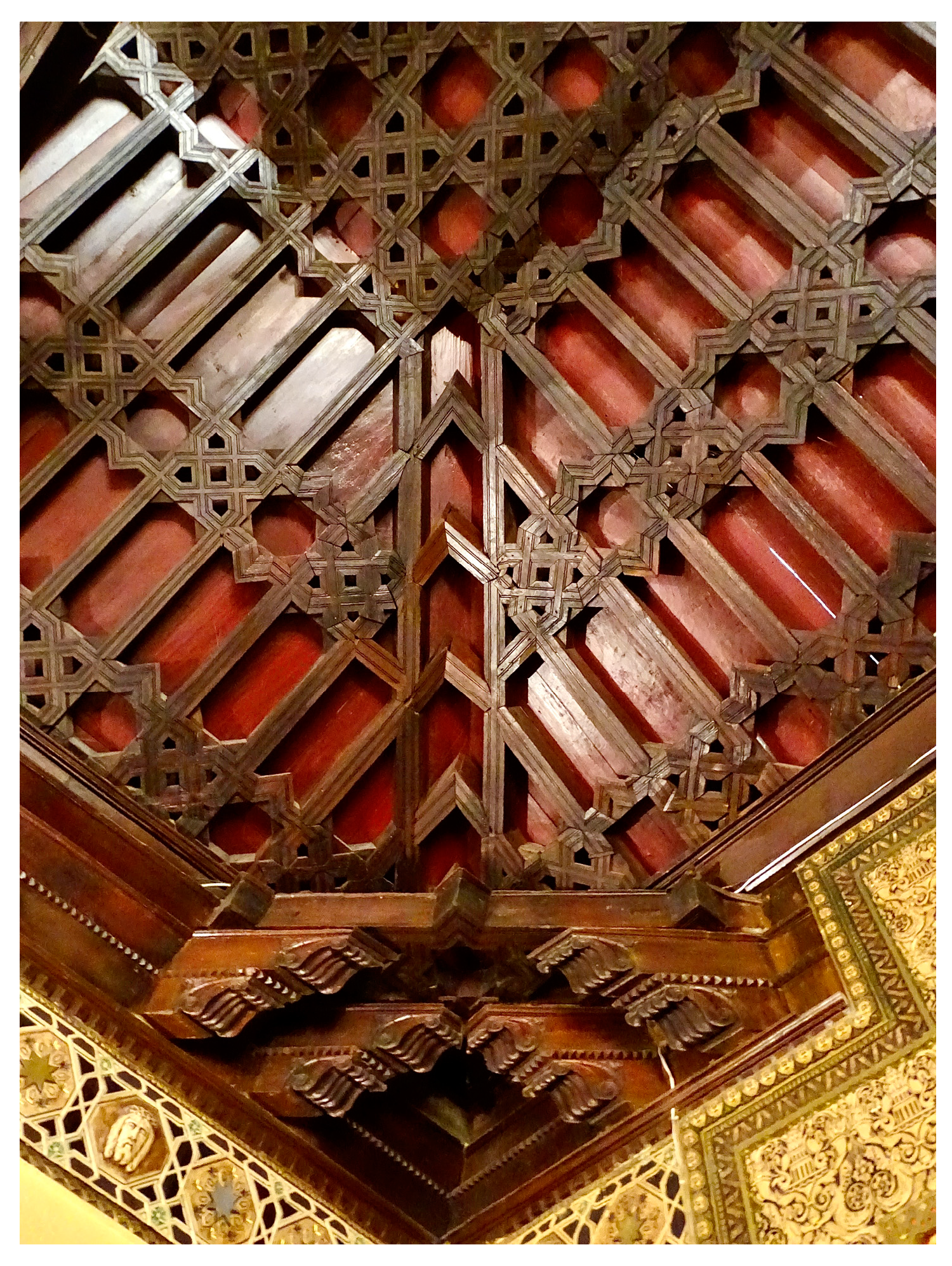

| 6 | For instance, the carpenter Alonso Velázquez, renowned for his craftsmanship in Lima during the late 16th century and the first decades of the 17th century, is known to have executed significant projects in just six documented contracts. These include the construction of the choir in the Santo Domingo church (AGN/PE, PN. 112, f.178r, 1597), the ceilings of the nave and choir in the Monasterio de la Limpia Concepción church (AGN/PE, PN.786, f.4705 r, 1602), the ceilings of the nave and choir in the Monasterio de las Carmelitas Descalzas de San José church (AGN/PE, EN.788, 3019v, 1606), the ceiling of the nave in the Novitiate church of San Antonio Abad de la Compañía de Jesús (AGN/PE, EN.1914, f.2556, 1612), the ceilings of the main chapel and nave in the San Marcelo church (AGN/PE, EN.763, f.581v, 1615; AGN/PE, EN.1864, f.709v, 1618), and the woodwork in the San Sebastian church (AGN/PE, EN.768, f.1139v, 1620). Antonio San Cristóbal suggests that Alonso Velázquez may have also been responsible for constructing the wooden dome above the main staircase of the San Francisco de Lima Convent in 1625 (San Cristóbal 2006, p. 128). |

| 7 | The number of carpenters in the cities of the viceroyalty could indeed vary. For instance, it is estimated that there were approximately 300 carpenters in Lima by 1631 (Salinas y Córdova 1631, p. 129). On the other hand, records indicate that only three carpenters were documented in Tunja by 1620 (Jiménez et al. 2018, p. 14). |

| 8 | In the 17th century, four carpentry treatises were authored in the Hispanic world. They were written by Diego Lopez de Arenas (Seville 1633), Fray Andrés de San Miguel (Mexico, ca. 1630), Fray Lorenzo de San Nicolás (Madrid, 1639 and 1665), and Rodrigo Álvarez (Salamanca 1674). |

| 9 | In recent years, researchers who have critically examined the term in the context of Spanish America have approached it from visual, material, and even decolonial perspectives, distancing themselves from the technical aspects of carpentry (Feliciano 2016; Schreffler 2022; Wolf and Martínez Nespral 2022). |

| 10 | One of the earliest proponents of this hypothesis was the Argentine scholar Martin Noel (Noel 1921, pp. 65, 127, 179). |

| 11 | ‘We have received information that some Berber slaves, slaves, and other free individuals, who have recently converted from the Moorish faith, along with their children, have migrated to those regions. We have taken measures to prevent their migration, as it has become evident from past experiences that many inconveniences have arisen as a result. Furthermore, we must be cautious about the potential harm caused by those who have already migrated or may migrate in the future. In a newly settled land, such as this, where the Faith is being established, it is necessary to eliminate any opportunities for the propagation of the Mohammedan sect or any other sect that may undermine God Our Lord and the integrity of our Holy Catholic Faith. This matter has been thoroughly considered and discussed in our Council of the Indies, leading to the agreement that all Berber slaves, slaves, and individuals who have recently converted from the Moorish faith, along with their children, should be expelled from the island and province in which they currently reside and sent to these Kingdoms’ (AGI. INDIFERENTE, 427, L.30, f.2v, 1543). |

| 12 | ‘[…] of pure Christianos lineage’ (Ordenanzas de Sevilla 1527, ff. 147v–148r). |

| 13 | AAL (Archbishopric of Lima Archives, Peru), 1541–1927, no. 49, COF-27, 1512–1613, ff. 210r–217r, 1595 [1575]. These ordinances have been transcribed with an introductory study (Alruiz and Fahrenkrog 2020, pp. 169–80). |

| 14 | In the Viceroyalty of New Spain, carpentry ordinances have been found for the city of Mexico (1568) and for Puebla de los Angeles (1570). Both ordinances are regulatory documents that, while having some similarities with the Seville ordinances, are shaped by the local development of carpentry practices in these territories (Barrio Lorenzot 1920, pp. 80–85; Díaz Cayeros 2002, pp. 91–117). |

| 15 | In fact, some decades after the promulgation of the Ordinances, it was not truly respected in Lima. On 18 October 1609, a group of carpenters gathered to discuss certain measures of the guild concerning the brotherhood of San José and the adherence to the ordinances. It was brought to attention that the rules were not being followed, and there was a need to re-examine all the carpenters in the city. They also emphasized the utmost importance of prohibiting blacks and mixed-race individuals (mestizos, mulatos, y negros) from being examined or even working as carpenters (AGN/PE, PN, 786, ff. 4703r–4712r). |

| 16 | The ordinances exclude carpinteros de ribera, i.e., those involved in the construction of wooden ships. |

| 17 | Limas Moamares: It is a constructive solution used to resolve the joint between two roof gables, where each gable provides a hip rafter that facilitates prefabrication. The cross-section of the hip rafter resembles a right-angled trapezoid. |

| 18 | The treatrise is entitled Breve compendio de la carpintería de lo blanco: y tratado de alarifes, con la conclusión de la regla de Nicolas Tartaglia, y otras cosas tocantes a la iometría, y puntas del compás. |

| 19 | The current definition provided by the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) narrowly defines the meaning of Carpinteria de lo blanco as a carpenter who works in the workshop and makes tables, benches, etc. |

| 20 | These carpenters were also known as ensambladores, that is, altarpieces builders or retablo makers. |

| 21 | The manuscript remained in the San Angel Convent in Mexico until 1860, when it fell into private hands due to exclaustration. In 1902, Genaro García, one of its last owners, presented a paper on the manuscript at the Congress of Americanistas in Mexico. Years later, in 1921, Genaro Garcia’s heirs sold the manuscript to the University of Texas, where it is preserved today. The manuscript was finally published in 1965 by Eduardo Baez in Mexico. |

| 22 | Indigenous carpenters practiced their trade in colonial Santiago during the 16th century through a type of contract in which the encomendero rented the labor force of a skilled indigenous individual (Contreras 2023, p. 41). |

| 23 | ANE (National Archives of Ecuador), Fondo especial, caja 3, vol. 7, 1661–1674, f 80r, 1665 (Webster 2012, p. 13). |

| 24 | ANE, Fondo especial, caja 3, vol. 7, 1661–1674, f.85r, 1665 (Webster 2012, p. 13). |

| 25 | The circulation of Indigenous carpenters also extended in the direction of the city of Cusco (Wightman 1990, pp. 118–20). |

References

Archival and Unpublished Sources

General Archive of the Indies (Seville, Spain)AGI. INDIFERENTE, 427, L.30, f.2v, 1543.AGI, QUITO, 211, L.1. f. 140, 1567General Archive of the Nation (Lima, Peru)AGN/PE, PN. 32, 1r–1v, 1557AGN/PE, PN, 144, ff. 217–217v, 1593.AGN/PE, PN, 112, f.178r, 1597.AGN/PE, PN, 786, ff.4703r–4712r, 1602.AGN/PE, PN, 788, 3019v, 1606.AGN/PE, PN, 786, ff. 4703r–4712r, 1609.AGN/PE, PN, 1914, f.2556, 1612.AGN/PE, PN, 763, f.581v, 1615.AGN/PE, PN, 1864, f.709v, 1618.AGN/PE, PN, 800, f.22r, 1619.AGN/PE, PN, 768, f.1139v, 1620.AGN/PE, PN, 183, f.62r, 1626.AGN/PE, PN, 1723, ff. 2393r–2394v, 1627.AGN/PE, PN, 1256, ff. 245r–246v, 1648.AGN/PE, PN, 1289, f.372v, 1652.Archbishopric of Lima Archives (Lima, Peru)AAL, 1541–1927, no. 49, COF-27, 1512–1613, ff. 210r–217r, 1595 [1575].National Archive and Library of Bolivia (Sucre, Bolivia)BO ABNB, EP. 136, 58r–63r, 1618.Potosi HistoricalArchive—Casa Nacional de Moneda (Potosí, Bolivia)AH-POT, EN.47, ff. 2220–2220v, 1614.General Archive of the Nation (Bogotá, Colombia)AGN/COL, Colonia, Fabrica-Iglesias, SC.26.2.D.1, ff.356r–369v, 1567.AGN/COL, Colonia, Visitas-C/Marca, SC.62.5.D.43, ff.815r–819r, 1600.AGN/COL, Colonia, Visitas-C/Marca: SC. 62,13, D.5, f. 866v, 1601.AGN/COL, Colonia, Fábrica-Iglesias: SC.26,5, D.25, f.741r, 1606.AGN/COL, Colonia, Fabrica-Iglesias, SC.26.4.D.8, f.769r, 1630.AGN/COL, Colonia, Fabrica-Iglesias, SC.26.2.D.6, f.669v, 1644.San Miguel, Fray Andrés. (ca. 1630). Tratado de Andrés de San Miguel. Mexico: Benson Latin American Collection (University of Texas at Austin), Ms.65,G73.Published Sources

- Alruiz, Constanza, and Laura Fahrenkrog. 2020. Las Ordenanzas Del Oficio de Carpinteros de La Ciudad de Los Reyes (Perú, Siglo XVI). Resonancias: Revista de Investigación Musical 24: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, Eduardo. 1969. Obras de fray Andrés de San Miguel. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. [Google Scholar]

- Barrio Lorenzot, Francisco del. 1920. El Trabajo En México Durante La Época Colonial. México: Secretaria de Gobernación, Dirección de Talleres Gráficos. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, Frederick. 1974. The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524–1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Irene, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson. 2020. Race and Modern Architecture. A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chica, Angélica. 2015. Aspectos histórico-tecnológicos de las iglesias de los pueblos de indios del siglo XVII en el Altiplano Cundiboyacense como herramienta para su valoración y conservación. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/76233 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Ciriza-Mendívil, Carlos. 2019. Tributo y mita urbana. Movilización y migración indígena hacia Quito en el siglo XVII. Anuario de Estudios Americanos 76: 443–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Suarez, Ananda. 2015. Making Race Visible in the Colonial Andes. In Envisioning Others: Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America. Edited by Pamela Patton. Leiden: Brill, pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, Hugo. 2023. Migración indígena y trabajo artesanal urbano en una capital provincial. Santiago de Chile, fines del siglo XVI y primero mitad del siglo XVII. Anuario del Centro de Estudios Históricos Profesor Carlos S. A. Segreti 1: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Noble David, ed. 1968. Padrón de Los Indios de Lima En 1613. Lima: Seminario de Historia Rural Andina. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Karoline P. 2016. Forbidden Passages: Muslims and Moriscos in Colonial Spanish America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo Bouroncle, Jorge. 1960. Derroteros de arte cuzqueño. Datos para una historia del arte del Perú. Cusco: Editorial Garcilaso. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos, José Amador. 1859. Discurso de D. José Amador de los Ríos leído en la Real Academia de Nobles Artes de San Fernando en su recepción pública. Granada: Imprenta de José María Zamora. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/17749 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Díaz Cayeros, Patricia. 2002. Las Ordenanzas de Los Carpinteros y Alarifes de Puebla. In El Mundo de Las Catedrales Novohispanas. Edited by Montserrat Galí i Boadella. Puebla: Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, pp. 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Diccionario de la lengua castellana compuesto por la Real Academia Española, reducido a un tomo para su más fácil uso. 1780. Madrid: Por Don Joaquín Ibarra, impresor de Cámara de Su Majestad, y de la Real Academia.

- Epstein, Stephan R. 1998. Craft Guilds, Apprenticeship, and Technological Change in Preindustrial Europe. The Journal of Economic History 58: 684–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Jesus. 2021. Architecture, Race, and Labor in the Early Modern Spanish World. In Constructing Race and Architecture 1400–1800 (Part 1). Edited by David Karmon. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80: 268–69. [Google Scholar]

- Escobari, Laura. 2001. Caciques, yanaconas y extravagantes: La sociedad colonial en Charcas s. XVI-XVIII. La Paz: Embajada de España en Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, María Judit. 2016. The Invention of Mudejar Art and the Viceregal Aesthetic Paradox: Notes on the Reception of Iberian Ornament in New Spain. In Histories of Ornament: From Global to Local. Edited by Gülru Necipoğlu and Alina Alexandra Payne. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González, Laura. 2021. Architecture, the Building Trade, and Race in the Early Modern Iberian World. In Constructing Race and Architecture 1400–1800 (Part 1). Edited by David Karmon. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80: 388–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Andrew B., and Matthew F. O’Hara. 2009. Imperial Subjects. Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- França Paiva, Eduardo. 2020. Nombrar lo nuevo. Una historia léxica de Iberoamericana entre los siglos XVI y XVII (las dinámicas de mestizaje y el mundo del trabajo). Santiago: Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- García Morales, María Victoria. 1991. La figura del arquitecto en el siglo XVII. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. [Google Scholar]

- García Nistal, Joaquín. 2021. Pragmatismo y Ostentación. Soluciones de La Carpintería de Lo Blanco En Monasterios Femeninos En Tiempos de Transición. In Desde El Clamoroso Silencio. Estudios Del Monacato Femenino En América, Portugal y España de Los Orígenes a La Actualidad. Edited by Daniele Arciello, Jesús Paniagua and Nuria Salazar. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 603–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestoso y Pérez, José. 1899–1909. Ensayo de un diccionario de los artífices que florecieron en Sevilla: Desde el siglo XIII al XVIII inclusive. 3 vols. Sevilla: [s.n], Available online: http://www.bibliotecavirtualdeandalucia.es/catalogo/es/consulta/registro.do?id=1014480 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Gutiérrez, Ramón. 1979. Notas sobre organización artesanal en el Cusco durante la colonia. Histórica 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth-Terré, Emilio. 1945. Artífices en el Virreinato del Perú. Lima: Imprenta Torres Aguirre. [Google Scholar]

- Harth-Terré, Emilio. 1960. El indígena peruano en las bellas artes virreinales. Lima: Editorial Garcilaso. [Google Scholar]

- Harth-Terré, Emilio. 1973. Negros e indios: Un estamento social ignorado del Perú colonial. Lima: Librería-Editorial Juan Mejía Baca. [Google Scholar]

- Harth-Terré, Emilio, and Alberto Márquez Abanto. 1962a. El artesano negro en la arquitectura virreinal limeña. Lima: Librería e Imprenta Gil. [Google Scholar]

- Harth-Terré, Emilio, and Alberto Márquez Abanto. 1962b. Perspectiva social y económica del artesano virreinal en Lima. Lima: Librería e Imprenta Gil. [Google Scholar]

- Hering, Max. 2007. ‘Raza’: Variables históricas. Revista de Estudios Sociales 26: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, Max. 2011. Color, pureza, raza: La calidad de los sujetos coloniales. In La cuestión colonial. Edited by Heraclio Bonilla. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, pp. 451–69. [Google Scholar]

- James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. 2022. Black Lives Matter: An Architectural Historian’s View from Europe. Architectural Histories 10: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, Orián, Sonia Pérez, and Kris Lane. 2018. Artistas y artesanos en las sociedades preindustriales de Hispanoamérica, siglos XVI–XVIII. Historia y sociedad 35: 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Lyman. 1986. Artisans. In Cities & Society in Colonial Latin America. Edited by Louisa Schell Hoberman and Susan Migden Socolow. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 227–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jorquera, Natalia. 2014. Culturas constructivas que conforman el patrimonio chileno construido en tierra. Revista AUS 16: 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konetzke, Ricardo. 1947. Las ordenanzas de gremios como documentos para la historia social de Hispanoamérica durante la época colonial. Revista Internacional de Sociología 5: 421–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Bertram T. 1935a. Libro de Cabildos de Lima. Libro Quinto (1553–1557). Lima: Impresores Sanmartí-Torres Aguirre. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Bertram T. 1935b. Libro de Cabildos de Lima. Libro Sexto (1557–1561), Primera Parte. Lima: Impresores Sanmartí-Torres Aguirre. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Bertram T. 1937. Libro de Cabildos de Lima. Libro Octavo (1575–1578). Lima: Sanmartí-Torres Aguirre. [Google Scholar]

- Llaguno y Amírola, Eugenio, and Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez. 1829. Noticias de los Arquitectos y Arquitectura en España desde su restauración. 4 vols. Madrid: Imprenta real, Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000013547 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Lockhart, James. 1994. Spanish Peru. 1532–1560. A Social History, 2nd ed. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. First Published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- López de Arenas, Diego. 1633. Breve compendio de la carpintería de lo blanco: y tratado de alarifes, con la conclusión de la regla de Nicolas Tartaglia, y otras cosas tocantes a la iometría, y puntas del compás. Sevilla: Impreso por Luis Estupiñan. Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000054505 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- López Guzmán, Rafael. 2012. Carpintería mudéjar en América. In La carpintería de armar: Técnica y fundamentos histórico-artísticos. Edited by Carmen González Román and Estrella Arcos von Haartman. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani-Fuentes, Francisco. 2022a. ‘Enlazada con grande artificio’. La charpenterie de lo blanco dans l’architecture religieuse de la vice-royauté du Pérou aux XVIe et XVIIe siècle. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres-École Normale Supérieure, Universidad de Granada, Paris, France, Granada, Spain. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10481/77678 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Mamani-Fuentes, Francisco. 2022b. Historiografías entrecruzadas. La construcción del término ‘Arquitectura Mudéjar’ en América. In La construcción de imaginarios. Historia y Cultura visual En Iberoamérica (1521–2021). Edited by Ester Prieto Ustio. Santiago: Ariadna Ediciones, pp. 111–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mamani-Fuentes, Francisco. 2023. Sous le regard de Saint-Joseph. Les ordennances des charpentiers: Séville (1527) et Lima (1575). In Les inscriptions spatiales de la réglementation des métiers (Moyen Âge et Époque Moderne). Edited by Robert Carvais, Mathieu Marraud, Arnaldo Sousa Melo, Catherine Rideau-Kikuchi and François Rivière. Palermo: New Digital Frontiers, (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, Germán. 2017. La Difusión Del Modelo Español de Cofradías y Gremios En La América Colonial (Siglos XV-XVI). In Cofradías En El Perú y Otros Ámbitos Del Mundo Hispánico: Siglos XVI–XIX. Edited by David Fernández, Diego Lévano and Kelly Montoya. Lima: Conferencia Episcopal Peruana, Comisión Episcopal de Liturgia del Perú, pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, José Antolín. 2018. Gremios artesanos, castas y migraciones en cuatro ciudades coloniales de Latinoamérica. Historia y Sociedad 35: 171–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, Martin. 1921. Contribución a la Historia de la Arquitectura Hispanoamericana. Buenos Aires: Talleres S.A. Casa Jacobo Peuser. [Google Scholar]

- Noli, Estela S. 2001. Indios ladinos del Tucumán colonial: Los carpinteros de Marapa. Andes 12: 1–31. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12701207 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Nuere, Enrique. 2012. La carpintería de lo blanco a través de la imagen. In La carpintería de armar: Técnica y fundamentos histórico-artísticos. Edited by Carmen González Román and Estrella Arcos von Haartman. Málaga: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Málaga, pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ordenanzas para el Buen Régimen y Gobierno de la muy noble, muy leal e imperial ciudad de Toledo. 1858. Toledo: Imprenta de José de Cea, pp. 73–79. First Published 1551.

- Ordenanzas de Sevilla. 1527. Recopilación de las ordenanzas de la muy noble y muy leal ciudad de Sevilla, de todas las leyes y ordenamientos antiguos y moderno. Sevilla: Juan Varela de Salamanca. Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, SM 394. Available online: http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.gob.cl/bnd/632/w3-article-331866.html (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Paniagua, Jesús. 2010. Trabajar en Indias. León: Lobo Sapiens. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, Jesús, and Deborah L. Truhan. 2003. Oficios y actividad paragremial en la Real Audiencia de Quito (1557–1730): El corregimiento de Cuenca. León: Universidad, Secretariado de Publicaciones y Medios Audiovisuales. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10612/9975 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Quiroz, Francisco. 1995. Gremios, razas y libertad de industria. Lima colonial. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz, Francisco. 2008. Artesanos y manufactures en Lima colonial. Lima: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Souza, Juan Carlos. 2009. Le ‘style mudéjar’ en architecture cent cinquante ans après. Perspective. Actualité en histoire de l’art 2: 277–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas y Córdova, Buenaventura de. 1631. Memorial de Las Historias Del Nuevo Mundo Perú: Méritos y Excelencias de La Ciudad de Los Reyes, Lima. Lima: Imprenta de Jerónimo de Contreras. Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000092550 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- San Cristóbal, Antonio. 1993. Los alarifes de la ciudad de Lima durante el siglo XVII. Laboratorio de Arte 6: 129–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Cristóbal, Antonio. 1997. El carpintero mudéjar Alonso Velázquez. Revista del Archivo General de la Nación 15: 155–97. [Google Scholar]

- San Cristóbal, Antonio. 2006. Nueva visión de San Francisco de Lima. Lima: Institut français d’études andines. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, Jean-Frédéric, and Silvia Sebastiani. 2021. Race et histoire dans les sociétés occidentales (XVe-XVIIIe siècle). Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Schreffler, Michael J. 2022. Geographies of the Mudéjar in the Spanish Colonial Americas: Realms of Comparison and Competition, circa 1550–1950. Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 4: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Stuart B. 2020. Blood and Boundaries: The Limits of Religious and Racial Exclusion in Early Modern Latin America. Waltham: Brandeis University Press [EPUB]. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Pamela. 2018. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, Francisco de, ed. 1996. Normas y Leyes de La Ciudad Hispanoamericana 1492–1600. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Centro de Estudios Históricos. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, Manuel. 1946. Arte Mudéjar en América. México: Porrúa. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Ugarte, Rubén. 1947. Ensayo de Un Diccionario de Artífices Coloniales de La América Meridional. Lima: A. Baiocco y Cía. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Ugarte, Rubén. 1955. Ensayo de un Diccionario de artífices coloniales de la América meridional. Apéndice. Lima: A. Baiocco y Cía. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Susan V. 2009. Masters of the Trade: Native Artisans, Guilds, and the Construction of Colonial Quito. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68: 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, Susan V. 2012. Quito, Ciudad de Maestros: Arquitectos, Edificios y Urbanismo En El Largo Siglo XVII. Quito: Universidad Central del Ecuador, Comisión Fullbright. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, Ann M. 1990. Indigenous Migration and Social Change: The Forasteros of Cuzco, 1570–1720. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Caroline “Olivia” M., and Fernando Martínez Nespral. 2022. Introduction to the Dialogues on Rethinking Interpretations of the Mudéjar and Its Revivals in Modern Latin America. Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 4: 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, Jean-Paul. 1999. La voix du sang. Du ‘métis’ à l’idée de ‘métissage’ en Amérique espagnole. Annales HSS 2: 425–52. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27585886 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamani Fuentes, F. Colonial Carpenters: Construction, Race, and Agency in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th and 17th Centuries. Arts 2023, 12, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050218

Mamani Fuentes F. Colonial Carpenters: Construction, Race, and Agency in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th and 17th Centuries. Arts. 2023; 12(5):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050218

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamani Fuentes, Francisco. 2023. "Colonial Carpenters: Construction, Race, and Agency in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th and 17th Centuries" Arts 12, no. 5: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050218

APA StyleMamani Fuentes, F. (2023). Colonial Carpenters: Construction, Race, and Agency in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th and 17th Centuries. Arts, 12(5), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050218