Abstract

This research explores the figurative culture that flourished in Sicily during the 12th and 13th centuries, focusing on the interplay between artifacts of different types, materials, techniques and uses. Paintings, sculptures and objects that share a common visual language are analyzed with the aim of highlighting recurring motifs, mutual influences and related sources. The main focus is on the decorative apparatus of the Sacramentary Ms. 52 (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España), one of the most famous illuminated manuscripts from Sicily. The date, origin and patronage of this luxurious liturgical book have been the subject of intense scholarly debate. In order to shed light on these controversial issues, this study re-examines the various hypotheses considered by scholars, taking into account the historical events that affected Sicily from the end of the Norman to the beginning of the Swabian era. This analysis also shows how the decoration of the manuscript fits into the wider dynamics of cultural exchange that characterized Sicily and the Mediterranean during this transitional period.

1. Introduction

In recent years, studies of the visual culture of Norman Sicily have emphasized the importance of a comparative approach to better understand the artistic production of the period (Winkler and Fitzgerald 2020). Looking at the interaction between different art forms more generally sheds light on the transmission of workshop practices, the role of artists, and the social interactions to which the creation of artworks was linked. As W. Tronzo argues, assessing how and why artifacts were produced, used and conceived, crossing «the boundaries of media in a performative sense», reveals much about the phenomena of artistic imagination and the dynamics of «production by a community of creators and users» (Tronzo 2020, p. 47). Following this methodological perspective, this study will examine a series of artworks of different types, materials and uses produced in Sicily between the 12th and 13th centuries, highlighting their mutual influences and related cultural sources. The interactions between stylistic patterns, iconographic themes and decorative motifs will be analyzed by comparing examples of wall paintings, icons, liturgical objects, sculptures and illuminated manuscripts, with special reference to the miniatures of the famous Ms. 52 housed in the Biblioteca Nacional de España. This luxurious manuscript is considered one of the most significant examples of medieval illuminated books from Sicily. However, scholars are still debating its dating, origin, patronage and context of production. The aim of this research is not to provide a definitive solution, but to offer some insights by exploring the relationship between the decorative apparatus of the manuscript and the artistic culture of Sicily between the 12th and 13th centuries. We will also consider the geopolitical balances that redefined the relations between Palermo, Syracuse and Messina from the late Norman to the early Swabian period, and the key figures who played a crucial role in determining these balances.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional Ms. 52 comes from the library of Juan Francisco Tellez-Giron Pacheco, IV Duke of Uceda (Pomar 1976, p. 506; De Andrés 1975, p. 28), one of the most important book collections of the time. As is known, Uceda’s library included a group of Greek and Latin manuscripts that once belonged to the Cathedral Library of Messina. They were confiscated, along with the public archives, by the viceroy Francisco Benavides, Count of Santisteban, as punishment for Messina’s rebellion against the Spanish government in 1674–78. Uceda, who succeeded Santisteban, added them to his book collection and brought them back to Spain when his mandate ended in 1696. In 1711, King Felipe V confiscated the library from the Duke because he had sided with Austria in the struggle for the succession to the throne. The Uceda collection thus became part of the Spanish Royal Collections, and was later incorporated into the Biblioteca Nacional de España1.

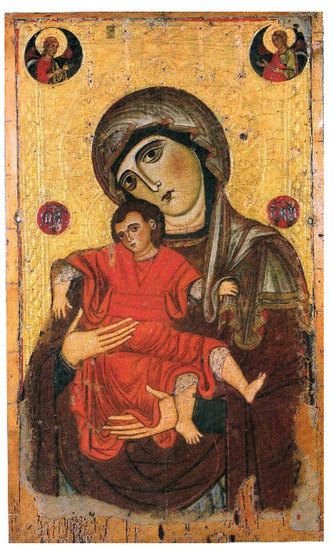

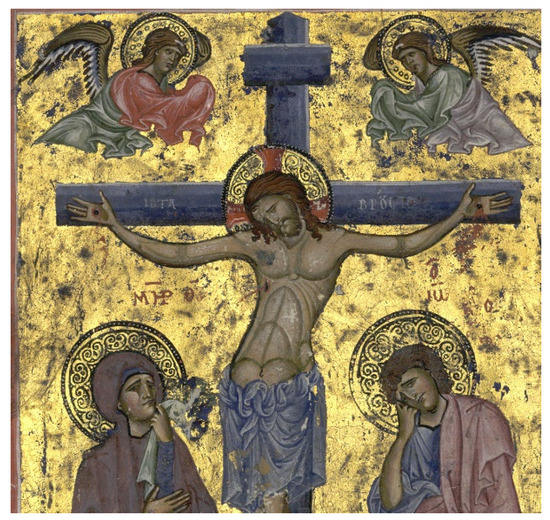

The manuscript consists of 303 folios and contains a complete Latin Sacramentary, preceded by a Calendar (4-9v) decorated with medallions, two for each month, showing the signs of the zodiac and the Labors of the Months2. The Sacramentary is followed by a Sanctorale (122v-) and the Litany (272r-). The Latin text, arranged in two columns, is decorated with 336 illuminated initials and two full-page miniatures (fol. 80 r-v) depicting the Virgin and Child and the Crucifixion, both with Greek inscriptions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52 (a) fol. 80r: the Enthroned Virgin with the Child; (b) fol. 80v: The Crucifixion. © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

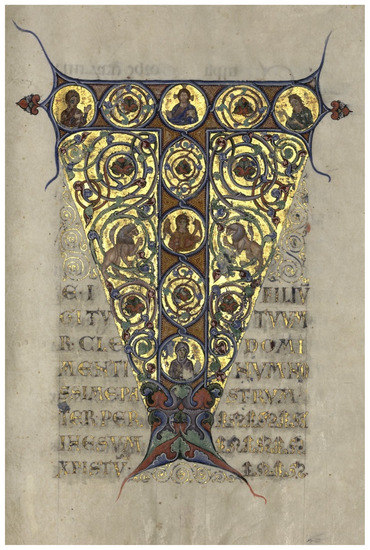

Among the illuminated initials, the initial T(e igitur) opening the Canon of the Mass (fol. 81r), contains a Deesis with Christ between the Virgin and John the Baptist in medallions, also with their Greek names (Figure 2). On the vertical shaft, aligned with the bust of Christ, an archangel is depicted in the center, and below, a female figure whose identity is still debated.

Figure 2.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52, fol. 81r, detail. Initial T(e igitur). © Biblioteca Nacional de España.

In 1955, Hugo Buchthal devoted a seminal study to this codex and other Sicilian manuscripts that he believed came from the same scriptorium (Buchthal 1955). In 1887 the manuscript was mentioned with its previous inventory record (C. 54) by Wilhelm von Hartel, who described it as probably of Messinian origin and dating from the 12th century (Hartel 1887, p. 393). A brief description can be found in Bordona’s catalog of the illuminated manuscripts of the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid (Domínguez Bordona 1933, p. 377, n. 934), as well as in the catalogs of the musical codices (Anglés and Subirá 1946, vol. I, pp. 91–92)3 and the liturgical manuscripts of the same Library (Janini and Serrano 1969, cat. no. 3, p. 2). It appears with the current entry in the Inventario General de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid (1953, pp. 47–48), which remains a useful reference for the study of the medieval manuscripts held by the Spanish Library4. Madrid 52 is also mentioned in various exhibition catalogs devoted to the Byzantine and medieval pictorial heritage in Spain (El Arte Románico 1961, cat. no. 22; Cortés Arrese in Cortés Arrese and Pérez Martín 2008, cat. no. 26, pp. 122–23), the artistic production associated with the Norman and Swabian rulers (Pace in Haussherr 1977, I, cat. no. 813, pp. 649–50; Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 100, pp. 365–67) and, more generally, the art of Byzantium and its environs (Byzantine Art 1964, cat. no. 377, pp. 352–53; Corrie in Evans 1997, cat. no. 316, pp. 479–80). However, it was Hugo Buchthal who first studied the manuscript in depth, addressing the problem of its origin, patronage and relationship to the specific historical context of medieval Sicily. Buchthal was also the first scholar to link this precious liturgical book to the patronage of the English bishop Richard Palmer, «vir licteratissimus et eloquens», as reported by the Norman chroniclers (Siragusa 1897, p. 63).

English by birth, French by education, Palmer was a friend of Pierre de Blois, the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket, and the Archdeacon of Catania Henry Aristippus, scientist, translator, and ambassador of William I to Constantinople in 1158/1160 (Mandalari 1939; Morpurgo 1997). Palmer served on the Royal Council of Palermo during the reigns of William I and William II, and was appointed Bishop of Syracuse in 1157 (Kamp 1975, p. 1014; Turner 1986). After his consecration in 1169, he commissioned a precious silver arm reliquary for the relic of Saint Marcian, the first Bishop of Syracuse (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Messina, Cathedral Treasure, Silver Arm Reliquary of Saint Marcian. (a), reprinted from Iacobini 2020 (with kind permission); (b), © Ufficio per I Beni Culturali Ecclesiastici e l’Edilizia di Culto, Arcidiocesi di Messina, Lipari, Santa Lucia del Mela (with kind permission).

According to Buchthal, there may be a connection between the Sacramentary and the silver reliquary that Palmer commissioned and brought with him to Messina after 1182, when he became Archbishop of the city. In his view, Marcian’s prominent and unusual position at the head of the list of holy confessors in the Litany (foll. 273v–274r)—where he is mentioned after Sylvester, Leo and Gregory—could indicate that the Madrid Sacramentary was written for the church where the precious reliquary containing Marcian’s arm was kept (Buchthal 1955, p. 316).

Buchthal also suggested that the female portrait placed within a medallion at the bottom of the initial T at the beginning of the Canon (fol. 81r) could be a second image of the Virgin (Figure 2). This repetition of the Virgin—in the Deesis decorating the horizontal bar of the letter and at the base of the shaft—would indicate, in his opinion, that the manuscript was made for a church dedicated to the Virgin, as would the miniature depicting the enthroned Theotokos occupying the place usually reserved for the Majestas Domini. Both the Cathedrals of Syracuse and Messina are dedicated to the Virgin, which is consistent with such a prominent place for the Virgin in the Sacramentary. Therefore, as Buchthal argued, it could have been written either for the Cathedral of Syracuse when Palmer held its bishopric, or for the Cathedral of Messina after Palmer’s appointment as Archbishop of Messina. At the same time, the Virgin is the special protector of Messina, and some Sicilian illuminated manuscripts, closely linked to Madrid 52 on stylistic grounds, have entries from the 15th century which testify that they belonged at that time to the Cathedral Treasure of Messina.

Based on these considerations, Buchthal concluded that the manuscript was most likely made for the Cathedral of Messina during Palmer’s archbishopric, after the transfer of the relic of Saint Marcian from Syracuse to Messina (Buchthal 1955). This hypothesis, supported by Angela Daneu Lattanzi (Daneu Lattanzi [1965] 1966, pp. 27–30), has achieved a large consensus, despite some alternative proposals that we will discuss below (Pace 1977; Pace in Haussherr 1977, I, cat. no. 813, pp. 649–50; Pace 1979).

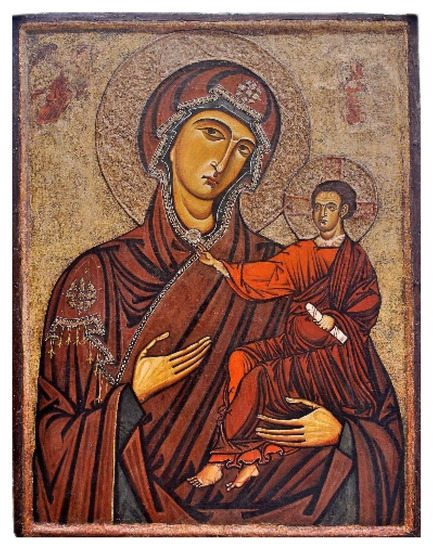

The Virgin on folio 80r (Figure 1a) appears within an architectural canopy consisting of a vaulted arch on columns surmounted by Corinthian capitals. She is seated on a throne with a double cushion. Following the typology of the Hodegetria, she holds the Child in her left arm and points to him with her right hand. The Child’s cheek is pressed against the Virgin’s cheek, in accordance with the so-called “Eleousa type”, a term commonly used to indicate the intense emotional relationship between the Virgin and her Son5. Christ wears an ochre himation over a pale tunic, held at the waist by a green horizontal sash and crossed at the shoulders by vertical bands of the same color as the sash.

The heavy purple maphorion of the Virgin falls on the blue tunic, the hem of which appears fragmented in folds with broken lines and profiled by a white outline that almost freezes its movement, as shown by the tunic’s flap hanging on the left: this is a stylistic device generally associated with the dynamic tendencies of late Comnenian painting, but which recurs in the Monreale mosaics to such an extent that it can be considered a specific mark of the Monreale workshop. Even the acanthus-based throne of the Virgin appears in the Monreale mosaics, for example, in the mosaic of the Virgin enthroned in the apse, whose affinities with the Madrid miniature are particularly evident (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Monreale Cathedral, apse, detail. © Public domain [Holger Uwe Schmitt, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 (accessed on 17 April 2023), via Wikimedia Commons].

These analogies have led scholars, starting with Buchthal himself, to interpret Madrid 52 as a product closely linked to the figurative culture of Monreale (Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 100, pp. 365–67; Corrie in Evans 1997, cat. no. 316, pp. 479–80). Comparisons with the ornamental repertoire of Ms. Vat. Lat. 42, a sumptuous Gospel book probably produced in the scriptorium of Monreale Cathedral (Pace 2017), as well as striking similarities with artifacts directly related to the Monreale mosaics, are further evidence.

The lively drapery and the sinuous movement of the folds of the garment between the Child’s legs (Figure 5) are found in Byzantine paintings of the late Comnenian period, notably in the frescoes of Lagoudera, Cyprus6. However, this stylistic solution recurs almost identically, for example, in the Hodegetria icon now in the Museo Diocesano of Palermo (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52, fol. 80r, detail. © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

Figure 6.

Palermo, Museo Diocesano, Icon of the Virgin and Child (from the Church of Santa Maria De Latinis). © Museo Diocesano di Palermo (with kind permission).

According to Maria Andaloro, this icon corresponds to the «iconam magnam» described in a document of 1171, which refers to the foundation of the monastery of Santa Maria de Latinis by Matteo d’Ajello, who, together with Palmer, headed the chancellery of William I (Andaloro in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 117, pp. 442–47). If we accept this high dating, the large icon would be placed among those works that relate so directly to the style of the Monreale mosaics as to suggest an almost contemporary execution.

A different hypothesis has been proposed by Valentino Pace (Pace 1977; Pace in Haussherr 1977, I, cat. no. 813, pp. 649–50; Pace 1979, 1998–99). According to him, the relationship between the miniatures of the Sacramentary and the Monreale mosaics can be interpreted as a consequence of the great success of the style and culture of the Monreale mosaics. Based on comparisons with English illuminated manuscripts and hagiographic considerations, Pace suggested that Madrid 52 was made for a church in Palermo in the early 13th century.

In support of the manuscript’s Palermo provenance, Pace pointed to the repeated appearance of Saint Christina, the ancient patron saint of Palermo, in the Calendar, Sanctorale and Litany. Moreover, he did not rule out the possibility that the female figure depicted in the lower part of the initial T(e igitur) on fol. 81r could be Saint Christina herself, rather than a second image of the Virgin, as suggested by Buchthal (Pace 1979, pp. 444–45). The inclusion of Saint Marcian in the Litany does not necessarily indicate, in his opinion, a direct link between the Madrid manuscript and the cult of the first Bishop of Syracuse, since the latter does not appear in the Calendar. However, the saint is also mentioned in the Sanctorale (fol. 150v)7 before Vitus, Modestus and Crescentia (Figure 7), who are listed in the Calendar on June 15 (fol. 6v). It is noteworthy that the feast of Saint Marcian is mentioned on June 14, before the feast of Vitus, Modestus and Crescentia, in some liturgical codices from Messina (Di Giovanni 1736, p. 365).

Figure 7.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52, foll. 150v-151r. © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

Subsequent studies have generally adopted Buchthal’s chronological hypothesis (Santucci 1981, pp. 143–47; Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 100, pp. 365–67; Di Natale in Andaloro 1995, pp. 357–58; Corrie in Evans 1997, cat. no. 316, pp. 479–80; Cortés Arrese in Cortés Arrese and Pérez Martín 2008, cat. no. 26, pp. 122–23; Campagna Cicala 2020, pp. 49–53), based also on aspects of paleography (Pratesi 1972; Owens 1977, pp. 17–18; Caldelli and De Fraja 2018). Recently, however, Pace has confirmed his interpretation, paying particular attention to the Child’s garment in the miniature of the enthroned Virgin (Pace 1998–99). According to him, the fact that the vertical sashes crossing the Child’s tunic are inconsistently placed on the same shoulder shows a lack of understanding of their particular sacred and priestly value. In his opinion, this misunderstanding could only be justified by allowing for a considerable delay with respect to the works in which this value was fully understood. We will now reconsider these main hypotheses, taking into account the specific historical, cultural and artistic context of Sicily.

2. Cultural Interactions: Sicily between the 12th and 13th Centuries

As Buchthal pointed out, the close relationship between the Madrid Ms. 52 and the decoration of the Cathedral of Monreale is evident both in the style of the miniatures and in the choice of saints, «which points to the northern affiliation of the Latin cult in Sicily» (Buchthal 1955, p. 315). Greek saints, French holy bishops and monks, saints from Southern Italy and Sicilian saints appear both in the mosaics of Monreale and in the Calendar of our manuscript. Among the saints venerated in Sicily, two are of particular importance: Saint Marcian, who comes fourth in the Litany when the Holy Confessors are invoked, and Saint Christina, who is mentioned in the Calendar, the Sanctorale and the Litany. It is true that the unusual position of Marcian in the Litany does not in itself provide decisive clues as to the origin of the manuscript. However, it is worth asking whether or not this peculiar choice is indicative of Richard Palmer’s patronage.

Sent to Syracuse, Palmer maintained close ties with the cultural milieu of the Norman court. Once in the episcopal see of Syracuse, he provided for the renovation and embellishment of the city’s Cathedral (Pirri [1644–47] 1733, p. 621; Russo 1991, p. 41). Only four decontextualized slabs can be attributed to this restoration work, whose technical solutions are similar to those of the floor mosaics in Palermo, Cefalù and Monreale (Agnello 1927, p. 40; Zorić 2009, pp. 122–24). From the sources, however, we know that he ordered the main apse to be decorated with frescoes, and a bishop’s throne with mosaics8.

A marble basin from the Cathedral of Syracuse (Figure 8) could be traced back to the years of Palmer’s archbishopric in Syracuse, if not to these renovations of the Cathedral. According to Gandolfo, this small font, placed on a pillar against a wall and therefore decorated on three sides, dates from the time of William I, as shown by comparisons with fragments of architectural sculpture from Palermo, dating from around the middle or third quarter of the 12th century (Gandolfo 2019, pp. 111–14, figs. 138, 139, 141). As Gandolfo observes, the lively depiction of the animals in the basin characterizes another Syracusan sculptural find, also with zoomorphic and foliate motifs, namely, the small slab reused above the niche traditionally identified with the tomb of Saint Lucy, the patron saint of Syracuse (Gandolfo 2019, p. 112, fig. 142). The lions on the Syracuse marble basin are part of a pictorial tradition known to have spread throughout the East and West in the Middle Ages. They follow a visual pattern well-represented in the artistic production of Norman Sicily, and transferred to various media (textiles, paintings, sculptures, etc.) «con il risultato di essere in ogni fase una ripresa della forma originale» (Tronzo 2011, p. 437). For example, lions with similar heads and tails can be found at the base of the porphyry sarcophagus of Frederick II in the Cathedral of Palermo, originally intended for the burial of Roger II in the Cathedral of Cefalù (Gandolfo 2019, pp. 91–98, fig. 105). Moreover, several lions, alone or in pairs, appear on the ceiling of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, in panels with tendrils between the figures and the outer frame, both in the nave and in the aisles. According to Tronzo, their peculiar iconographic type could come from Fatimid Egypt (Tronzo 2011). The two lions, surrounded by vegetal scrolls flanking the Archangel Michael in the initial T(e igitur) of the Messina manuscript (Figure 2), draw from this common repertoire of visual sources of Mediterranean origin. As Buchthal notes, these lions are «almost identical counterparts to those in the mosaic on the east wall of the Norman stanza» in Palermo (Buchthal 1955, p. 318)9, which in turn can be compared to the lions facing a palm tree that adorn a marble slab from the church of San Giovanni in Syracuse (Figure 9)10. It is likely that this slab with the lions facing each other was made after the Norman reconstruction of the church of San Giovanni and the crypt below, traditionally associated with the cult of Saint Marcian. The four capitals with the symbols of the Evangelists, reused during or after the Norman reconstruction of the crypt vault, are also closely related to the pictorial vocabulary of the Monreale mosaics (Gandolfo 2019, pp. 441–43).

Figure 8.

Syracuse, Galleria Regionale di Palazzo Bellomo, basin decorated with zoomorphic and foliage motifs, marble, 42 × 52 × 44 cm (from the Cathedral of Syracuse). © Regione Sicilia (with kind permission).

Figure 9.

Syracuse, Galleria Regionale di Palazzo Bellomo, slab with lions on the sides of a palm tree, marble with mosaic decorations, 76 × 95 cm (from Syracuse, Church of San Giovanni). © Regione Sicilia (with kind permission).

In particular, the capital with the symbol of Saint Mark (Figure 10) bears some resemblance to the lion preserved on the marble slab from the church of San Giovanni, in terms of the linear rendering of the mane and the shape of the heads. Furthermore, the leaf-shaped end of the lion’s tail on the marble slab—also a common motif in medieval representations of lions—appears on the reused slab above the so-called tomb of Saint Lucy mentioned above. If these correspondences are derived from cross-cultural medieval imagery, there seems to be a kinship between the zoomorphic and phytomorphic motifs in the manuscript miniatures and those found in Syracusan artifacts probably produced during Palmer’s bishopric, and perhaps related to his patronage.

Figure 10.

Syracuse, crypt of San Marciano, reused capital with the symbol of Mark. © Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra (with kind permission).

The debt to Norman artistic culture is evident in the miniatures of Ms. 52, which Buchthal considered «an offshoot of the work done in Palermo and Monreale» (Buchthal 1955, p. 319). The miniatures, however, have a new breath: the line not only affects the surfaces, but also generates the forms. Emotions are translated into believable gestures and movements. In the illuminated initials, Byzantine motifs coexist with Latin patterns, and this contamination is found in some manuscripts produced in Jerusalem in the third quarter of the 12th century.

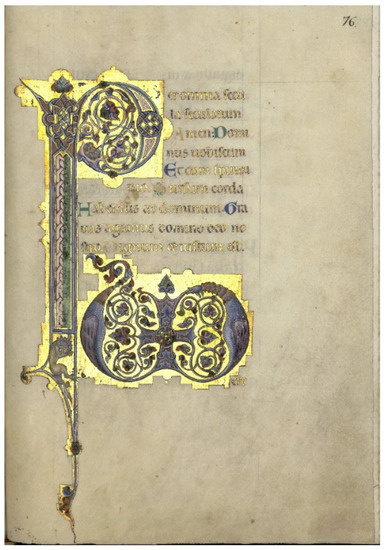

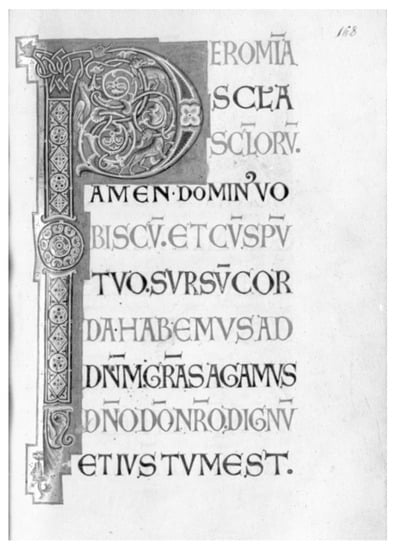

As Buchthal first noted, the initial P(er omnia) on fol. 76r (Figure 11) has strong parallels in the initial P of a Missal (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. Ms. 12056, fol. 168r) used to celebrate Mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre11 (Figure 12), whose miniatures have often been compared to the prefatory miniatures of the famous Psalter of Melisende (Buchthal 1957, pp. 14–23, 107–21; Folda 1995, pp. 159–63, pl. 6.12a; Drake Bohem in Drake Bohem and Holcomb 2016, cat. no. 77, p. 161). It is also similar to the letter P at the beginning of the Prologue of Ms. 227 in the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence (Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 104, pp. 373–74). Other Madrid manuscripts attributed by Buchthal to the same «school of miniature painting» are characterized by a more unified language, which, according to him, «acquires an identity of its own» and reflects a later phase in the development of the scriptorium’s activity: these are Mss. 6, 9, 10, 14 and the Bible cum glossa in seventeen volumes (Mss. 31–47), six of which bear 15th century entries, indicating that they belonged to the Messina Cathedral Treasure at that time (Buchthal 1955, pp. 319–25). Recent research suggests that this Bible was produced no later than 1160, even on the basis of strictly paleographic data (Caldelli and De Fraja 2018). It should therefore be excluded from the group of manuscripts which, according to Buchthal, Palmer would have commissioned from a Messinian scriptorium after 1182. Admittedly, there is currently no evidence for the existence of a scriptorium in the Cathedral of Messina in the 12th century. However, this does not mean that Ms. 52 cannot be linked to Richard Palmer’s patronage. With these factors in mind, we will now consider Buchthal’s hypothesis that the manuscript was produced in Messina in a scriptorium founded by Palmer after 1182.

Figure 11.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52, fol. 76r, Initial P(er omnia). © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

Figure 12.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Ms. Latin 12056, initial P(er omnia), fol. 168r. Source gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Palmer’s transfer from Syracuse to Messina at the turn of the year 1182–83 (Kamp 1975, p. 1017) seems to be linked to the geopolitical balances that affected the Sicilian cities at the end of the 12th century. During the Norman period, Syracuse had lost the great importance it had enjoyed during the Byzantine domination of Sicily. The ancient bishopric of Syracuse, the first in Sicily, became a suffragan of the archbishopric of Monreale in 1188 and its prestige gradually declined, except for the brief period of the archbishopric of Palmer (Kamp 1975, pp. 1013–18). On the other hand, during the reigns of William I and William II, Messina played a key role among the coastal cities, also in relation to the strategic importance of its port, an ideal starting point for the Holy Land, a pivot of the city’s economic rebirth and vehicle of an intense network of trade with the eastern Mediterranean. A series of documents dating back to the sixties and nineties of the 12th century attest to the presence of Messinian citizens in Genoa, and inform us of a continuous cultural, social and commercial exchange with one of the main players in Mediterranean politics (Pispisa 1993, p. 154). We also recall that the elevation to the archbishopric of Messina—decreed by the antipope Anacletus II in 1131 but not recognized by the legitimate popes—was officially sanctioned by pope Alexander III in 1166 (von Falkenhausen 2018, p. 21)12. The placement of a member of the Royal Council at the head of the Messina bishopric would have been part of a redefinition of the religious geography of Sicily.

Once he became Archbishop of Messina at the beginning of 1183, Palmer continued the renovation of the Cathedral founded by Roger II and originally dedicated to Saint Nicholas. The Cathedral, with its new dedication to the Virgin, was consecrated in 1197, two years after Palmer’s death (Pispisa 1999, pp. 265–84; Mellusi 2010–11). However, it is highly probable that during or shortly after the restoration of the Cathedral, Palmer may have commissioned liturgical books for use in the celebration of Mass, along with other works of art.

With regard to the figurative culture expressed in the Messina area at the end of the 12th century, the frescoes removed from the so-called church of the Quattro Santi Dottori in San Marco d’Alunzio, now in the museum of the town, are rare surviving examples of monumental decoration (Campagna Cicala 2020, pp. 63–64; Guida and Rigaglia 2021). The right apse (Figure 13) shows the Virgin in a half-length pose, with her cheek touching that of her Son, according to the “affectionate” iconographic scheme adopted for the miniature of the Virgin in the Madrid manuscript. Christ is shown upright in the arms of the Virgin, an unusual iconographic type which finds its earliest representation in the famous 11th-century (or early 12th-century) Sinai hexaptych (Figure 14) (Skhirtladze 2014). This peculiar variant of the Child’s pose spread to the West and East from the 12th century onwards: it is found, for example, in the Big Tolda Icon of the Mother of God, dating from the last quarter of the 13th century and now in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow (Kalopissi Verti 2005, p. 311), where the Virgin is depicted enthroned, as in the Madrid manuscript.

Figure 13.

(a) San Marco d’Alunzio (ME), Museo della Cultura e delle Arti Figurative Bizantine e Normanne, frescoes from the so-called church of the Quattro Santi Dottori (b) detail. © Comune di San Marco d’Alunzio (with kind permission).

Figure 14.

Sinai, Monastery of Saint Catherine, panel with images of the Virgin and Christological cycle, detail: Virgin “Blachernitissa”. Reprinted from Skhirtladze 2014.

Beside the Virgin is an angel carrying the censer, a theme found in 12th century Byzantine frescoes, for example, in the Enkleistra of Saint Neophytos at Paphos, Cyprus (Mango and Hawkins 1966, p. 158, fig. 45; Nicolaïdès 2012, pp. 120–21). Near the angel, the hem of a pink robe can be seen, the wavy folds of which recall the “dynamic style” of late Comnenian paintings. As mentioned earlier, this characteristic way of depicting drapery (Mouriki 1980–81, pp. 100–2) recurs extensively in the mosaics of Monreale, and is also found in the miniature of the Virgin in our manuscript, as well as in the icon of Santa Maria de Latinis, now in the Museo Diocesano of Palermo. However, the representation of the Fathers of the Greek Church, Basil and John Crysostom, officiating and converging towards the altar, reflects the emphasis on the relationship between liturgy and decoration attested in Byzantium since the 12th century. The iconographic and stylistic characteristics of the Greek patriarchs, as well as the Greek text of their unfolded scrolls, leave no doubt that the fresco of San Marco d’Alunzio belongs to a purely Byzantine cultural milieu, and suggest a direct link with Byzantine models.

The points of contact with the frescoes of San Marco d’Alunzio are further evidence of the close relationship between the miniatures of the Madrid manuscript and late Comnenian figurative sources (Corrie in Evans 1997, p. 480), particularly of Balkan and Cypriot origin. The paired Virgin and Crucifix miniatures on folios 80r-v reflect theological content variously expressed in 12th century Byzantine religious poetry (Belting [1990] 2022, pp. 385–91). The reciprocal relationship between these miniatures seems to imply a system of thought which has an illuminating visual outcome in the famous double-sided icon of Kastoria, with the mourning Hodegetria on the recto, and the Man of Sorrows on the verso (Constas 2016). Related to these rhetorical procedures, aimed at highlighting the role of the Virgin in God’s plan for the salvation of mankind, is the mural icon of the Virgin Arakiotissa (Figure 15) in the Cypriot church dedicated to her (Winfield and Winfield 2003, p. 111). The same powerful synthesis of the stages of salvation is expressed in the famous Virgin of Vladimir (Belting [1990] 2022, pp. 417–21), one of the highest examples of the widespread iconographic theme taken up by the Virgin of Madrid. In sum, the firm adherence of the Madrid miniatures to themes, stylistic features, doctrinal content and poetic tendencies of 12th century Byzantium cannot be explained solely by the influence of the Monreale mosaics. Indeed, the miniatures appear to have drawn from a broader range of Byzantine sources.

Figure 15.

Lagoudera (Cyprus), Church of the Panagia tou Arakou, Virgin and Child Arakiotissa, © Public domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arakiotissa_Lagoudera.jpg#/media/File:Arakiotissa_Lagoudera.jpg (accessed on 17 April 2023).

Another example of these converging influences can be cited. The miniature of the Virgin in the Madrid manuscript bears a remarkable resemblance to the icon of the Hodegetria from the Cathedral of Monreale, usually attributed to the 12th century (Figure 16). Travagliato has recently proposed, also on the basis of scientific analyses, to date this icon to the 13th century (Travagliato 2019). It must be said, however, that the similarities between the icon and the Madrid miniature can be traced back to common sources, and do not necessarily imply a contextual dating. In fact, it should be noted that certain iconographic details present in both works—such as the purple maphorion of the Virgin and the sandals on the feet of the Child13—are found in Cypriot icons and frescoes from the 12th century onwards. This could be further evidence of the connection between the miniatures of Madrid Ms. 52 and the Byzantine, especially Cypriot, figurative horizon to which the Monreale icon also refers. The icon of the Virgin and Child in the Cathedral of Piazza Armerina (Enna), whose iconographic type follows that of the famous Cypriot icon of Kykkos, also shows a clear link with the pictorial culture of Cyprus (Figure 17). Even in this icon, which has been variously dated by scholars to the 12th or 13th century (Andaloro in Andaloro 2006, I, cat. no. VIII.18, pp. 555–56), there are points of contact with the Virgin of Madrid, in the way the fold of the Virgin’s mantle falls on her left hand, as well as in the Child’s attire, in the patterned halos and in the highly “graphic” style14.

Figure 16.

Monreale, Cathedral (from), Hodegetria. Reprinted from Travagliato 2019.

Figure 17.

Piazza Armerina (Enna), Cathedral, Virgin and Child (Madonna “delle Vittorie”). Reprinted from Andaloro 2006 (with kind permission).

The interplay between Byzantine models, clearly recognizable in the manuscript’s full-page miniatures, and Western motifs, especially found in the initials, testifies to the manuscript’s eclectic identity. This combination of patterns may suggest that artists from different backgrounds and origins collaborated in its composition. As Buchthal pointed out, various elements borrowed from very different sources are combined to form a decorative system that is «a perfect image of the motley civilization of Sicily during the Norman period» (Buchthal 1955, p. 319).

Returning to the artistic context of Messina, I would like to mention a refined liturgical object currently kept in the city’s Cathedral Treasure: a silver processional cross (Figure 18), usually dated to the first half of the 13th century and attributed to Perrone Malamorte, a goldsmith favored by Frederick II (Ciolino, in Andaloro 1995, cat. 68, p. 271). The cross is made of a wooden structure covered with embossed silver sheet and profiled by a continuous beaded edge. The obverse shows the Crucifix, with the skull of Adam at the base of the cross, the Virgin and Saint John on the sides and an archangel at the top, where the Greek inscription ‘O BACILΛEYC THC DOΞHC is engraved. On the back, the Virgin Orans stands out among the four Evangelists, all with Greek inscriptions, on a background decorated with scrolls ending in floral elements.

Figure 18.

Messina, Cathedral Treasure, processional cross; (a) recto; (b) verso. Reprinted from Guastella 2005 (with kind permission).

It was generally assumed that this precious artifact belonged to the Treasure of the Cathedral of Messina. However, some archival documents suggest a different origin (Guastella 2005). Two silver processional crosses are mentioned in some inventories, drawn up by royal visitors at the end of the 16th century, concerning the Treasure of the Monastery of San Salvatore in Messina. One of these crosses is described in detail by the visitor Daneu, as follows: «crux argentea cum imagine Crucifixi ab una parte et ab alia cum imagine beate virginis Marie e septem aliis imaginibus sanctorum et cum diversis gemmis bullij seu cristallinis cum suo pomo ereo»15. The description corresponds exactly to the cross in the Cathedral of Messina, not only in terms of iconography and the number of images, but also in details such as the six bezels for crystal cabochons that have left their mark on the wood of the cross. The archival data do not provide clear information on the cross’s origin and context of production. However, they do confirm that in the 16th century there was a silver cross in the monastery of San Salvatore that was identical to the one in the Treasure of the Cathedral of Messina, and could probably be identified with it.

The type of flowers in the vegetal scrolls on the back of the cross are very similar to those in the scrolls of the T(e igitur) initial in the Madrid manuscript (Figure 2). There are also similarities, stemming from a common Byzantine vocabulary, in the way in which the crucified Christ is represented, with his arms slightly bent, his feet spread and placed on the suppedaneo, under which the skull of Adam appears. The Evangelists at the ends of the back of the cross bear some resemblance to the Evangelists Mark and John, who are depicted inside the initial I of their respective Gospels in Madrid Ms. 6 (foll. 151r, 175r). The latter, a Bible also from the Uceda collection (Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 101, p. 369), is stylistically related to Ms. 52, as Buchthal first pointed out. Furthermore, Christ’s halo in the initial D of Ms. 9 (fol. 6v), also housed in the Madrid Library (Menna in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 102, pp. 369–70), shows a heart-shaped decoration (Figure 19), as do the halos in the Madrid miniatures (Figure 20). This motif, evoking the pastiglia technique used in Cypriot icons from the end of the 12th century and then widespread throughout the Mediterranean (Castiñeiras 2015; Iacobini 2020, p. 49), is also present on Christ’s halo in the silver cross.

Figure 19.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 9, fol. 6v, detail © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

Figure 20.

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 52, fol. 80v, detail. © Biblioteca Nacional de España (with kind permission).

In this regard, it should be noted that the provenance of Ms. 9 from the Cathedral of Messina cannot be questioned, despite the absence of the ownership note present in other Madrid manuscripts. In fact, an oath of allegiance from Onofrio Archimandrite of the Monastery of San Salvatore of Messina to Robert, Bishop of Messina, was added to fol. 134r (Caldelli 2018). The document was added by an almost contemporary hand and can be dated between 1158 and 1165, which should provide a terminus ante quem for the production of the manuscript. Thus, the hypothesis of its origin in the Messina scriptorium allegedly founded by Palmer after his appointment as Archbishop of Messina must be reconsidered. In any case, the similarities between the decorative apparatus of Ms. 9 and that of Ms. 52 shed light on the stylistic trends circulating in Messina in the second half of the 12th century, as well as on the close relationship between the bishopric of Messina and the Archimandrite during the reign of William I.

It is clear that the Sasanian palmette is a popular decorative motif in Byzantine art, and that it is used extensively in artworks not only of Byzantine origin and not only from the 12th century. However, the association of the Virgin with the Crucifix on the recto and verso of both the manuscript and the silver cross, along with the common solid and naturalistic rendering of the foliage motifs, may not be coincidental correspondences. Moreover, stylized palmettes are frequently found in the book production of the Greek monastery of San Salvatore in Messina (Rodriquez 2013)16. The relationship between Ms. 52 and the illuminated manuscripts produced or kept at the Monastery of San Salvatore cannot be discussed here. Suffice it to say that the monastery’s collection also included manuscripts from other artistic centers of the Mediterranean world, such as the precious Octoechos Messan. gr. 51, a liturgical-musical codex of probable Palestinian–Cypriot origin (Fobelli in Andaloro 1995; D’Aiuto and Bucca 2011, p. 89).

Finally, another piece of evidence for the importation of figurative models from Byzantium to Messina could be an icon of the Madonna and Child, which follows the iconographic type of the Madrid Madonna (Campagna Cicala 2020, p. 54, fig. 46). According to the 17th century historian of Messina, Placido Samperi (Samperi 1644, pp. 423–25), this icon, now dispersed, was originally kept in the monastery of Santa Maria di Malfinò, one of the most famous monasteries in medieval Messina.

It is worth noting that the contamination of Latin and Greek elements that characterizes our manuscript can also be seen in the arm reliquary of Saint Marcian (Figure 3). The anthropomorphic typology of the reliquary comes from Western models, while the lozenge-shaped motif with a three-petalled flower inside, and the scrolls displayed on the vertical chevron are from the Byzantine repertoire (Ciolino in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 67, p. 269; Musolino in Macchi and Heilmeyer 2008, cat. no. 168, pp. 306–7). This cultural exchange, encouraged by the patronage of Palmer himself, could also justify the points of contact between the decoration of the manuscript and the miniatures of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, highlighted by Buchthal. Similarities—both in layout and decorative devices—can be found, as mentioned, in the Missal Ms. Lat. 12056 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France and in a Sacramentary, also from the Holy Sepulchre (Rome, Biblioteca Angelica, Ms. D. 73 and Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, Ms. McCLean 49), whose initials are «taken directly from southern Italian with some English sources» (Folda 1995, p. 162; Buchthal 1957, pp. 14–23, 140–41). According to Pace, however, the affinities with the Crusader miniatures are superficial. More important for defining the cultural background of Ms. 52, he argues (Pace 1977), is the presence of similar decorative motifs, including the small heads emerging from the leaves, in the initials of 12th century English illuminated manuscripts, such as the Winchester Bible or the Bury Bible (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms. 002I)17. The dragons forming the V of the Vere Dignum in the Madrid Preface (Figure 11) do indeed appear in works associated with the Winchester School, such as the frescoes of Santa Maria de Sigena, Spain (Oakeshott 1972, figs. 37, 208). However, these frescoes may be more closely related to the famous Psalter of Queen Melisende, as has recently been suggested (Naya and Castiñeiras 2021). More generally, decorative motifs that recur in English miniatures are also found in book illuminations from the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, as Pace himself noted. For example, dragons occur in the initial D(eus) (fol. 92r) in the Sacramentary of the Holy Sepulchre cited above (Folda 1995, pl. 5.18a). As Rebecca Corrie observes (Corrie 2013, p. 71), these Western motifs, accompanied by Byzantine floral forms, constitute a decorative repertoire that some early 14th-century manuscripts, such as the Morgan Bible (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, Ms. G 60), later drew upon18. In any case, the relationship of the Madrid Sacramentary to English miniatures is consistent with the possible patronage of the English bishop Richard Palmer, who had received his theological training in France and may have asked for some of his books to be copied.

It should also be remembered that Messina assumed a dominant role, especially after the death of William II and the crisis of central power in Palermo. As a Greek enclave and a cosmopolitan city, Messina was an ideal place for the exchange of customs, arts and ideas of Western and Eastern origin. The Knights of the Holy Land may have played an important role in the circulation of Mediterranean culture and artifacts in Sicily. In particular, the Hospitallers had their mother house in Messina, the Hospital of San Giovanni (Petracca 2006, pp. 61–69). Especially from 1196 onwards, Messina can be considered as the main center of the Hospitallers in Sicily (Toomaspoeg 2003, p. 55). In this context, the relationship noted by Buchthal with an Evangeliary in the Cathedral Museum of Mdina (Malta) is noteworthy (Buchthal 1955, p. 320; Buchthal 1956, p. 83; Pace 1979, p. 433, and nn. 14–16).

3. Mediterranean Exchanges: Crossing Borders, Lasting Influences

Recent studies (Toomaspoeg 2001; Toomaspoeg 2003, pp. 49–68, 101–10, 260) have shown that Hospitaller establishments were present in Sicily from the late 12th century, especially along the roads connecting Messina, Catania and Syracuse.

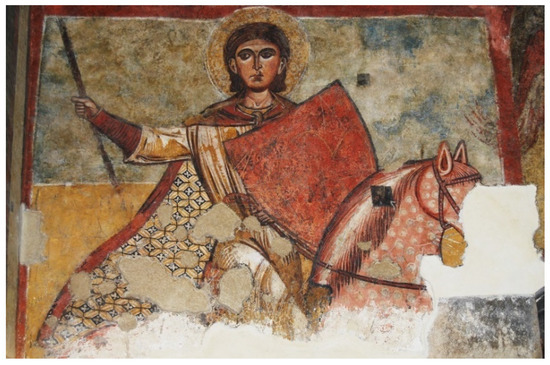

In the chapel of the castle of Paternò, near Catania, a series of equestrian saints were painted around the 1220s (Iacobini 2020), and this iconographic choice could be linked to the presence of Hospitaller establishments in the area (Figure 21). The saints depicted on the side walls of the chapel originally had raised gesso halos, a recurring feature of Mediterranean icons (Iacobini 2020, pp. 49–52, figs. 35 and nn. 94–96). This technique, widespread in 13th century Cypriot icons (Weyl Carr 2012), is also present in Sicilian artifacts with an explicit Mediterranean connotation. It can be seen, for example, in the painted cross from the church of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro in Syracuse (Andaloro in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 123, pp. 474–80), dating from the early 13th century (Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Paternò (Catania), Chapel of the Castle, Saint Nestor. © Parco archeologico e paesaggistico di Catania e della Valle dell’Aci (with kind permission).

Figure 22.

(a) Syracuse, Church of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro, painted cross; (b) detail. © Fondo Edifici di Culto (with kind permission).

The fall of the gesso relief in the halo of Christ and under the right arm of the Cross shows a heart-shaped motif very similar to that of the halos in the miniatures of the Madrid manuscript. One of the Holy Knights portrayed in the Paternò Chapel, probably Saint Mercury (Iacobini 2020, p. 62, n. 94, fig. 30), also shows traces of the preparatory sketch for a raised gesso halo. In this light, the similarities noted by Iacobini between the arm of Saint George painted on the southern wall of the Paternò Chapel and the reliquary arm of Saint Marcian are particularly significant (Iacobini 2020, p. 47).

Several works of art from 13th century Sicily reflect this circulation of “Mediterranean” artistic ideas. For example, the frescoes in the apse of the Paternò Chapel are closely related to the remains of the 13th-century apsidal frescoes in the cave church of Santa Margherita at Lentini (Syracuse), and to the later frescoes in the church of San Nicola at Castiglione di Sicilia, near Catania (end 13th–early 14th century). These similarities may be due to the presence of Hospitaller houses along the routes connecting these cities (Arcidiacono 2019). A relationship with the Hospitallers can also be postulated for the 13th-century decoration of an oratory inside the catacomb of Santa Lucia in Syracuse, where a mural icon depicting Saint Hippolytus on horseback holding a banner appears (Figure 23) (Arcidiacono 2020, pp. 47–51).

Figure 23.

Syracuse, Catacomb of Santa Lucia, oratory of the region C, Saint Hippolytus. © Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra (with kind permission).

Although the representation of saints on horseback with banners does not necessarily imply a reference to a specific military order (Pace 2021), the documented presence of the Hospitallers in the area could give historical significance to this peculiar way of representing Saint Hippolytus. The same saint on horseback is depicted in the Paternò chapel, along with other equestrian saints (Iacobini 2020). In this respect, it is worth mentioning that in 1177 Roger of Aquila granted the church of San Giovanni in Adrano, not far from Paternò, to the Hospitallers of Messina (Toomaspoeg 2001, p. 320; Petracca 2006, p. 136). Furthermore, in 1211 the Genoese Alamanno Costa donated to the Hospitallers an estate adjacent to the church of Santa Lucia in Syracuse. It is from this church that the aforementioned painted cross with patterned gesso halos and background comes. Beneath the same church, in the catacomb of Santa Lucia, is the oratory with the fresco of Saint Hippolytus as a Holy Knight.

Finally, a 13th-century pictorial intervention in the crypt of San Marciano in Syracuse, possibly linked to a renewed promotion of the cult of the city’s first bishop, Marcian, could fit into the same historical framework (Arcidiacono 2020, pp. 37–40). This phase included a series of panels depicting saints in architectural canopies which bear some resemblance to the Virgin’s canopy in the Madrid manuscript (Figure 24).

Figure 24.

Syracuse, Crypt of San Marciano, Evangelist. © Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra (with kind permission).

Themes and motifs that spread throughout the East and West during the 13th century may have reached Sicily as early as the last quarter of the 12th century, with the support of high-ranking members of the Norman administration or the ecclesiastical hierarchy linked to the royal court.

4. Conclusions

The cross-cultural nature of Madrid Ms. 52 has raised, and continues to raise, many questions which this brief study does not claim to answer. Further research is needed, including a re-examination of the paleographic and codicological aspects in relation to other medieval Sicilian manuscripts, not only from Messina. However, some working hypotheses can be formulated on the basis of the comparative data obtained by placing the manuscript in the artistic context of Sicily at the end of the 12th century.

Although it is not yet possible to prove that the manuscripts analyzed by Buchthal in 1955 originated from the same scriptorium, it is probable that at least Madrid Ms. 52 was made between 1169 and 1195, during the period when Palmer served as Bishop of Syracuse and then as Archbishop of Messina.

The affinities between Ms. 52 and other 12th century Sicilian manuscripts—both in terms of decorative elements and textual characteristics—point in this direction, as does the close relationship between the Madrid miniatures and the art and culture of late Comnenian Byzantium. This dating is fully consistent with the historical dynamics of Sicily between the reigns of William I and William II. During this period, a well-defined book production is documented in Sicily, reflecting the speculative orientations of the studies carried out in the cathedrals of northern Europe. This could help to explain the mixture of Western elements and Byzantine motifs that characterizes our manuscript. On the other hand, the origin and destination of the codex remain controversial. Both of Buchthal’s proposals seem viable. The first, which was recently reproposed by Caldelli and De Fraja (Caldelli and De Fraja 2018, p. 269), is that the manuscript was made for the Cathedral of Syracuse before 1182. The second hypothesis, which Buchthal ultimately reached, is that it was made for the Cathedral of Messina after Palmer became Archbishop of the city, in connection with the transfer of the precious arm reliquary of Saint Marcian from Syracuse to Messina. At the present state of research, several factors lead us to consider the latter option as the most likely.

It is true that the well-recognized links between the full-page miniatures and the Monreale mosaics are not sufficient to define the origin and date of the manuscript, since the Norman mosaics gave rise to a codified “Byzantine” language that had a pervasive and long-lasting influence in Sicily. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that certain figurative motifs and patterns that were prevalent in the visual culture of Norman Sicily, and appear in the manuscript’s decoration, recur in some Syracuse artifacts, probably dating from the period when Palmer was Bishop of Syracuse: the basin with zoomorphic and foliate motifs from the Cathedral of Syracuse, the marble slab with mosaic lions from the church of San Giovanni and the reused capitals in the crypt of San Marciano. Furthermore, the relationship between the manuscript and the mosaics of the Cathedral of Monreale is evident not only in the style of the miniatures, but also in the choice of saints.

The presence of Nordic saints, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in the iconographic program of the Cathedral of Monreale suggests a possible influence of Richard Palmer and reflects the tendencies of William II’s foreign policy, which culminated in 1177 with his marriage to Joan of England, daughter of King Henry II (Brodbeck 2010, pp. 102–5, fiche n.167, pp. 738–43). It should be recalled that Richard Palmer accompanied Princess Joan of England from Saint-Gilles to Sicily, together with Robert of Caserta and the Archbishop of Capua, Alfano (Jamison 1943, p. 29). The consolidation of political relations between the Altavilla and the English dynasty thus involved Palmer and Alfano as protagonists. The English components found in the initials of Madrid 52 and their association with illuminations in pure Byzantine language could well be justified in this context. We also recall that the precious cover of the Evangeliary of Archbishop Alfano, produced in the Norman royal ergasterion probably after 1176, has an enameled image of Thomas Becket on the back and a corresponding image of Saint Agatha on the front, as if to suggest «un legame spirituale tra l’Inghilterra e la Sicilia» (D’Onofrio 1993, p. 279). One might wonder if it is a coincidence that the crucified Christ on the front cover bears a certain resemblance to the illuminated Crucifixion of Madrid 52 (Guida in Andaloro 2006, I, cat. no. IV.5, pp. 261–63).

The prominence of Saint Marcian in the Cathedral of Monreale, but also in the Madrid manuscript, could underlie a network of ideological meanings to which the transfer of the arm reliquary of Saint Marcian from Syracuse to Messina would be linked (Brodbeck 2010, pp. 72–73).

By taking the relic, Palmer would have promoted himself as the heir of Saint Marcian, the first Bishop of Syracuse. The transfer of Marcian’s relic would have meant the transfer of the authority of the bishopric of Syracuse, traditionally considered to be of apostolic foundation, to that of Messina, also with the aim of compensating for Palmer’s failed election as Archbishop of Palermo (Kamp 1975, p. 1015). With this gesture, Palmer may have intended to enhance his role, his person and the bishopric he governed after 1182.

The cultural synthesis resulting from the juxtaposition of Byzantine and Western elements seems consistent with these historical events and with Palmer’s patronage. The same could be said of the comparisons with miniatures from the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, first highlighted by Buchthal. These contacts with the Crusader ateliers may have found fertile ground in Messina, defined as a megalopolis in two documents of 1172 (Pispisa 1993, p. 150). The production of the manuscript in Messina, where the scriptorium of the Monastery of San Salvatore flourished and where the famous illustrated Chronicle of Ioannes Skylitzes (Madrid, Vitr. 26-2) may have been realized19, fits into the complex network of relationships that this study has sought to focus on.

Messina, with its port «famous all over the world», as the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi remarks (Amari 1880, p. 68), could have been an ideal place for cultural exchanges at the end of the 12th century. During the 13th century, this multicultural language spread throughout eastern Sicily, also with the contribution of military orders. The recurrence of similar decorative motifs and technical procedures in different types of artifacts with a strong Mediterranean connotation is evidence of these cultural interactions, which were particularly encouraged after the Fourth Crusade.

Palmer died in Messina in 1195. A Latin inscription on the surviving slab of his tomb, now kept in the city’s Cathedral, refers directly to Bishop Palmer and his English origins: ANGLIA ME GENUIT, INSTRUXLT GALLIA FOVIT/TRINACRIS, HUIC TANDEM CORPUS ET OSSA DEDI/ANN[O] MCLXXXXV. OBIIT MENSE AUGUSTI DIE VII IND. XIII/ANGLICUS ANGELICU[S] GENERI[S] MERITI RATIONE, TRANSIT/A[D] ANGELICOS ASSOCIATUS EIS (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Messina, Cathedral, Slab of Richard Palmer’s tomb. © Messina, Museo Regionale Interdisciplinare, Archivio fotografico, Cattedrale, Monumenti funebri, n. 5 (with permission of Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e della Identità Siciliana—Museo regionale interdisciplinare di Messina(further reproduction prohibited without permission).

The tomb slab, damaged during World War II and partially reassembled in the 1950s, shows Christ enthroned between the Virgin and the Archbishop Palmer in medallions, with their names engraved (Di Giacomo in Andaloro 1995, cat. no. 83, pp. 309–11; Gandolfo 2011; Gandolfo 2019, pp. 444–50). We are therefore dealing with a Byzantine Deesis in which the Archbishop replaces the Baptist, a figurative choice that attributes to Palmer the exceptional role of saint and special intercessor. In fact, it cannot be considered as a private prayer for salvation, also because the engraved inscription states that the Archbishop has already been received into heaven (Gandolfo 2019, p. 445). As for the stylistic aspects, the relief finds «la sua logica collocazione all’interno degli esperimenti di trasferimento in scultura delle novità compositive, proposte dai mosaicisti bizantini, svolti all’interno del cantiere del chiostro della cattedrale di Monreale» (Gandolfo 2019, p. 449).

The relationship with the Deesis of the initial T(e igitur) in the Madrid manuscript, the throne of Christ, similar to that of the Virgin in our manuscript, and the V-shaped graphic rendering of the drapery, once again reveal the interactions between artworks of different medium, use and technique.

The artistic language of both artifacts is characterized by strong linear value effects, which show similarities with the stylistic trends of the Monreale mosaics. However, the relationships that the Madrid miniatures establish with the art and thought of Byzantium in the Comnenian period, as well as with artworks from Messina and its environs, trace a less direct system of exchange. What is certain is that the Deesis variant in the Messina tomb slab reflects the interests, ambitions and role of the powerful Archbishop Palmer, as well as the importance of the Bishopric of Messina and the city itself at the end of the 12th century.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Spain, within a project entitled, Manuscritos bizantinos iluminados en España: obra, contexto y materialidad-MABILUS (MICINN-PID2020-120067GB-I00). This research project, in which I am participating as a member of the working team, is located at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain). (https://mabilus.com, accessed on 17 April 2023).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | On the Duke of Uceda’s book collection and its vicissitudes, see (Torres and Longás 1935, p. VIII; Ruiz García and García-Monge Carretero 2001; Todesco 2007; Velasco 2009). |

| 2 | This study does not deal with the miniatures of the Calendar. On this subject, see the article by Carles Sanchez (2023) in this special issue of Arts. |

| 3 | Music notation appears on foll. 282, 283v, 284, 285v-294v, 296v, 297, 298v, 301. |

| 4 | It should be noted that the Inventario general de la Biblioteca nacional de Madrid does not indicate that the manuscript once belonged to the Duke of Uceda, and dates it to the 13th century, following Domínguez Bordona (1933, p. 377, n. 934) and Anglés and Subirá (1946, vol. I, pp. 91–92). On the other hand, the online catalog of the BNE records Ms. 52 as coming from the Uceda Library and dates it to the late 12th century. See: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000040682 (accessed on 17 April 2023), where a complete digital reproduction of the manuscript is also available. |

| 5 | Although the term was applied to various Byzantine images of Mary, not to a specific iconographic type. See on this subject (Pentcheva [2006] 2021, pp. 100–7). |

| 6 | For the Lagoudera frescoes, see (Winfield and Winfield 2003). |

| 7 | «Deus qui beatum Martianum pontificem tuum praesularis splendoris gloria sublimasti concede propitius ut qui eius sollemnia reverenter colimus ipsius beneficia iugiter sentiamus». This prayer is found with the variant “Marcianum” in the Missale secundum consuetudinem Gallicorum et Messanensis Ecclesiae, impressum Venetiis, per Ioannem Emericum alemanum Spirensis diocesis, 1499. See (Sorci and Zito 2009, Orationes Collectae, v. 2556, p. 373). |

| 8 | See (Pirri [1644–47] 1733, I, p. 623): «[…] vir liberalis, nobilissimi et ingenui animi fuit Richardus […] fecit exedram majoris Ecclesiae pingere, et chorum, et Cathedram Episcopalem in choro cum musio […]». |

| 9 | On the mosaics of the Norman Stanza, cf. (Knipp 2017, pp. 14–52). See also (Tronzo 2020). |

| 10 | The provenance of the slab from the church of San Giovanni is recorded in the Museum’s inventory. See also G. Barbera, scheda OA 19/00106291, 10.01.1982, Syracuse, Galleria Regionale di Palazzo Bellomo, archive. |

| 11 | https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90667252/f171.item.r=12056manuscript%20manuscript.zoom# (accessed on 17 April 2023). |

| 12 | The Bull of Pope Anacletus II appears in one of the Madrid manuscripts from the library of the Duke of Uceda (Ms. 198, fol. 3r). As the ownership note on fol. 1r indicates, it is one of the manuscripts that were certainly confiscated from the Cathedral of Messina. See (Caldelli 2018). |

| 13 | For example, the Child wears sandals in the well-known 13th-century icon from the templon of the church of Panagia at Moutoullas, Cyprus (Mouriki [1985–86] 1995, pp. 362–66, fig. 27; Weyl Carr 2012, p. 67), and in the Madonna della Madia icon from Monopoli attributed to Cipro by Valentino Pace (Pace 1985). |

| 14 | The Child’s dress, with vertical sashes crossing the tunic and tied to a waist sash, is a typical feature of Cypriot icons of the Virgin and Child, following the so-called Kykkotissa type (Mouriki [1985–86] 1995, pp. 362–63). This specific attire of the Child appears in the miniature of the Virgin in the Madrid manuscript, as well as in the Virgin and Child depicted in the lunette of the counter-facade of the Cathedral of Monreale. However, as mentioned above, Pace finds in the Madrid image a misunderstanding of the model, widespread since the 12th century, and considers it an indication of a later date. |

| 15 | Archivio di Stato di Palermo, Conservatoria di Registri, vol. 1309, f. 51r e ff. 29r-53v. |

| 16 | Cf. Antonino Tranchina (2023)’s article and bibliography in this special issue of Arts. |

| 17 | See for example in the Bury Bible the initial D on fol. 5v. [https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/catalog/nm203xw8381 (accessed on 17 April 2023)]. |

| 18 | Cathleen Fleck, for her part, suggests some parallels with the Riccardiana Psalter, now in the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence (Ms. 323). According to her, this luxurious prayerbook, characterized by a «special Holy Land nature», was made in Sicily by a Sicilian artist around 1225–35. The Psalter also features dragons decorated with white dots (fol. 14v), similar to the dragons in the Vere Dignum initial (fol. 76r) in Ms. 52 (Figure 11). Cf. (Fleck 2015). |

| 19 | Cf. Manuel Castiñeiras (2023)’s article in this special issue of Arts. |

References

- Agnello, Giuseppe. 1927. Il duomo di Siracusa e i suoi restauri. Per l’arte Sacra IV: 2–40. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, Michele. 1880. Biblioteca Arabo-Sicula. Roma/Torino: Loescher, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Andaloro, Maria, ed. 1995. Federico e la Sicilia. Dalla terra alla corona. (Palermo, Real Albergo dei Poveri, 16 dicembre 1994—30 maggio 1995). vol. II: Arti figurative e arti suntuarie. Siracusa: Ediprint. [Google Scholar]

- Andaloro, Maria, ed. 2006. Nobiles Officinae: Perle, filigrane e trame di seta dal Palazzo Reale di Palermo (Palermo, Palazzo dei Normanni, 17 dicembre 2003–10 marzo 2004). 2 vols. Catania: Maimone. [Google Scholar]

- Anglés, Higinio, and José Subirá. 1946. Catálogo musical de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid. I. Manuscritos. Barcelona: Consejo Superior De Investigaciones Cientificas. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, Giulia. 2019. Mémoire byzantine en Sicile orientale: La décoration picturale de l’église rupestre de Sainte-Marguerite à Lentini (Syracuse) et la culture artistique «méditerranéenne». Cahiers de Civilsation Médiévale 62: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, Giulia. 2020. Pittura medievale rupestre in Sicilia. Il territorio di Siracusa tra Oriente e Occidente. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 2022. Immagine e culto. Una storia dell’immagine prima dell’età dell’arte. Roma: Carocci. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck, Sulamith. 2010. Les saints de la cathédrale de Monreale en Sicile: Iconographie, hagiographie et pouvoir royal à la fin du XIIe siècle. Rome: École française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal, Hugo. 1955. A School of Miniature Painting in Norman Sicily. In Late Classical and Mediaeval Studies in Honor of Albert Mathias Friend, jr. Edited by Kurt Weitzmann. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 312–39. [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal, Hugo. 1956. The Beginnings of Manuscript Illumination in Norman Sicily. Papers of the British School at Rome 24: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchthal, Hugo. 1957. Miniature Painting in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byzantine Art. 1964. An European Art. Ninth Exhibition Held under the Auspices of the Council of Europe (Athens, Zappeion Exhibition Hall, April 1st-June 15th, 1964), 2nd ed. Athens: Department of Antiquities and Archaeological Restoration. [Google Scholar]

- Caldelli, Elisabetta, and Valeria De Fraja. 2018. “Iste liber est ecclesie maioris Messanensis”. Prime indagini su una biblioteca dispersa e sulla Bibbia cum glossa di Messina. In Civiltà del Mediterraneo: Interazioni grafiche e culturali attraverso libri, documenti, epigrafi. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studio dell’Associazione italiana dei Paleografi e Diplomatisti (Cagliari, 28–30 settembre 2015). Edited by Luisa D’Arienzo and Santo Lucà. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, pp. 217–82. [Google Scholar]

- Caldelli, Elisabetta. 2018. Bibbie atlantiche e non solo nella biblioteca della cattedrale di Messina in epoca normanna. Scrineum 15: 75–124. Available online: https://oajournals.fupress.net/index.php/scrineum/article/view/8837 (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Campagna Cicala, Francesca. 2020. Pittura Medievale in Sicilia. Messina: Magika. [Google Scholar]

- Castiñeiras, Manuel. 2015. Catalan Panel Painting around 1200, the Eastern Mediterranean and Byzantium. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean. Points of Contact across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c. 1000 to c. 1250. Result of the Second in the British Archaeological Association’s Series of Biennial International Romanesque Conferences (Palermo, Italy, 16–18 April 2012). Edited by Rosa Maria Bacile and John McNeill. Leeds: Manley, pp. 297–326. [Google Scholar]

- Castiñeiras, Manuel. 2023. Divination and Nekyia: Hypertexts in the Illumination of the Skylitzes matritensis. Arts 12. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Constas, Maximos. 2016. Poetry and Painting in the Middle-Byzantine Period: A Bilateral Icon from Kastoria and the Stavrotheokoia of Joseph the Hymnographer. In Viewing Greece: Cultural and Political Agency in the Medieval and Early Modern Mediterranean. Edited by Sharon E. J. Gerstel. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Corrie, Rebecca W. 2013. Sicilian Ambitions Renewed: Illuminated Manuscripts and Crusading Iconography. Studies in Iconography 34: 59–81. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23924247.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Cortés Arrese, Miguel, and Inmaculada Pérez Martín, eds. 2008. Lecturas de Bizancio: El legado escrito de Grecia en España (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional 15 de septiembre-a 16 de noviembre de 2008). Madrid: Bibioteca Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aiuto, Francesco, and Donatella Bucca. 2011. Per lo studio delle origini della Paracletica: Alcuni testimoni antiquiores d’ambito orientale e italiota. In Bisanzio e le periferie dell’Impero, Atti del I Convegno Internazionale nell’ambito delle celebrazioni del millenario della fondazione dell’Abbazia di San Nilo a Grottaferrata (Catania, Italy, 26–28 ottobre 2007). Edited by Renata Gentile. Acireale: Bonanno, pp. 73–102. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio, Mario. 1993. Capua. In Itinerari e centri urbani nel Mezzogiorno normanno-svevo. Atti delle decime giornate normanno-sveve (Bari, 21–24 ottobre 1991). Edited by Giosuè Musca. Bari: Dedalo, pp. 269–92. [Google Scholar]

- Daneu Lattanzi, Angela. 1966. Lineamenti di storia della miniatura in Sicilia. Firenze: Olschki. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrés, Gregorio. 1975. Catálogo de los manuscritos de la biblioteca del Duque de Uceda. Revista de Archivos Bibliotecas y Museos 78: 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni, Giovanni. 1736. De Divinis Siculorum Officiis. Panormi: Officina Regii Collegii Borbonici Nobilum RR. PP. Teatinorum. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Bordona, Jesús. 1933. Manuscritos con pinturas. Notas para un inventario de los conservados en colecciones públicas y particulares de España. Àvila-Madrid: Centro de Estudios Historicos. [Google Scholar]

- Drake Bohem, Barbara, and Melanie Holcomb, eds. 2016. Jerusalem, 1000–400. Every People Under Heaven (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, September 26, 2016–January 8, 2017). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Jerusalem_1000_1400_Every_People_Under_Heaven (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- El Arte Románico. 1961. Exposición organizada por el gobierno espagnol bajo los auspicios del Consejo de Europa (Barcelona y Santiago de Compostela, Palacio Nacional de Montjuich, 10 de julio a 10 de octubre de 1961. Barcelona: Grafica Bachs. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Helen C., ed. 1997. The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843–1261 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 11–July 6 1997). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Glory_of_Byzantium_Art_and_Culture_of_the_Middle_Byzantine_Era_AD_843_1261 (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Fleck, Cathleen A. 2015. The Luxury Riccardiana Psalter in The Thirteenth Century: A Nun’s Prayerbook? Viator 46: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folda, Jaroslav. 1995. The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1098–187. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfo, Francesco. 2011. La lastra tombale dell’arcivescovo Riccardo Palmer nella cattedrale di Messina. Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte XXXIV 66: 191–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfo, Francesco. 2019. La scultura nella Sicilia normanna. Tivoli: Tored. [Google Scholar]

- Guastella, Claudia. 2005. Aspetti della cultura artistica nel Valdemone in età normanna e sveva: Note e riflessioni. In La Valle d’Agrò: Un territorio, una storia, un destino. Atti del Convegno internazionale di Studi (Marina d’Agrò, 20–22 febbraio 2004), I. L’età antica e medievale. Edited by Clara Biondi. Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali, pp. 225–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guida, Maria Katja, and Davide Rigaglia. 2021. Gli affreschi della chiesa dei Quattro Santi Dottori a San Marco d’Alunzio. Cultura artistica e restauro. Messina: Di Nicolò edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel, Wilhelm August Ritter von. 1887. Bibliotheca Patrum latinorum Hispaniensis. vol. I. Wien: Carl Gerold’s Sohn. Available online: https://archive.org/details/bibliothecapatru01loew/page/2/mode/2up (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Haussherr, Reiner, ed. 1977. Die Zeit der Staufer, Geschichte–Kunst–Kultur (Stuttgart, 26.03.1977–05.06.1977). Bd. I. Stuttgart: Württemberg Landesmuseum. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobini, Antonio. 2020. Tra Sicilia e Terra Santa: Le pitture murali della Cappella del Castello di Paternò. Arte Medievale X: 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Inventario General de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, I. 1953. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Dirección General de Archivos y Bibliotecas.

- Jamison, Evelyn. 1943. Alliance of England and Sicily in the second half of the Twelfth Century. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 6: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janini, José, and José Serrano. 1969. Manuscritos litúrgicos de la Biblioteca Nacional—Catálogo. Madrid: Dirección general de archivos y bibliotecas. [Google Scholar]

- Kalopissi Verti, Sophia. 2005. Representations of the Virgin in Lusignan Cyprus. In Images of the Mother of God, Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium. Edited by Maria Vassilaki. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 305–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Norbert. 1975. Kirche und Monarchie im staufischen Königreich Sizilien, I, Prosopographische Grundlegung: Bistümer und Bischöfe des Königreichs 1194–266, 3, Sizilien. München: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Knipp, David. 2017. The Mosaics of the Norman Stanza in Palermo. A Study of Byzantine and Medieval Islamic Palace Decoration. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi, Giulio, and Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer, eds. 2008. Sicilia. Arte e archeologia dalla preistoria all’Unità d’Italia (Bonn, 25 gennaio-8 maggio 2008). Milano: Silvana editoriale. [Google Scholar]

- Mandalari, Maria Teresa. 1939. Enrico Aristippo arcidiacono di Catania nella vita politica e culturale del sec. XII. Bollettino Storico Catanese IV: 87–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril, and Ernest J. W. Hawkins. 1966. The Hermitage of St. Neophytos and its Wall Paintings. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 20: 119–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellusi, Giovan Giuseppe. 2010–11. “Pulchre sane ut modo erectam exornatamque”. La chiesa di San Nicola all’arcivescovado di Messina. Note storico-giuridiche. Archivio storico messinese 91–92: 137–58. [Google Scholar]

- Morpurgo, Piero. 1997. I centri di cultura scientifica. In Centri di produzione della cultura nel Mezzogiorno normanno-svevo. Atti delle dodicesime giornate nomanno-sveve (Bari 17–20 ottobre 1995). Edited by Giosuè Musca. Bari: Edizioni Dedalo, pp. 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mouriki, Doula. 1980–81. Stylistic Trends in Monumental Painting of Greece during the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 34–35: 77–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouriki, Doula. 1995. Thirteenth-Century Icon Painting in Cyprus. In Studies in Late Byzantine Painting. London: Pindar Press, pp. 341–410. First published 1985–86. [Google Scholar]

- Naya, Juan, and Manuel Castiñeiras. 2021. Like a Psalter for a Queen. Sancha, Melisende and the New Testament Cycle in the Chapter-House at Sijena. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 174: 55–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaïdès, Andréas. 2012. La peinture monumentale byzantine en Chypre du Xe au XIIIe siècle. In Chypre: Entre Byzance et l’Occident: IVe-XVIe siècle (Paris, Musée du Louvre, 28 octobre 2012–28 janvier 2013). Edited by Jannic Durand and Dorota Giovannoni. Paris: Louvre Éditions, pp. 112–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oakeshott, Walter. 1972. Sigena. Romanesque Paintings in Spain and the Artists of the Winchester School. London: Harvey Miller and Medcalf. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Jean Dorothy. 1977. The Madrid Bible and the Latin Manuscripts of Norman Sicily. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 1977. Le componenti inglesi nell’architettura e nella miniatura siciliana tra XI e XII secolo. In Ruggero il Gran Conte e l’inizio dello stato normanno: Relazioni e comunicazioni nelle seconde giornate normanno-sveve (Bari 19–21 maggio 1975). Roma: Il Centro di Ricerca, pp. 175–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 1979. Untersuchungen zur sizilianischen Malerei, in Die Zeit der Staufer, Geschichte—Kunst—Kultur (Stuttgart, 26.03.1977–05.06.1977), Bd. V Supplement. Edited by Reiner Haussherr and Christian Väterlein. Stuttgart: Württemberg Landesmuseum, pp. 431–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 1985. Presenze e influenze cipriote nella pittura duecentesca italiana. Corso di Cultura sull’Arte Ravennate e Bizantina XXXII: 259–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 1998–99. Da Bisanzio alla Sicilia: La “Madonna col Bambino” del “sacramentario di Madrid” (ms. 52 della Biblioteca Nazionale). Zograf 27: 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 2017. Due vangeli fra Terrasanta e Sicilia. In Bibbia. Immagini e scrittura nella Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Edited by Ambrogio M. Piazzoni and Francesca Manzari. Milano: Jaca Book, pp. 190–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Valentino. 2021. Arte dei crociati e ordini militari. Realtà storica e mito storiografico nell’Oltremare mediterraneo e in Puglia. In Gli ordini di Terrasanta. Questioni aperte, nuove acquisizioni (secoli XII-XVI). Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi (Perugia, 14–15 novembre 2019). Edited by Arnaud Baudin, Sonia Merli and Mirko Santanicchia. Perugia: Fabrizio Fabbri Editore, pp. 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2021. Icone e Potere. La Madre di Dio a Bisanzio. Milano: Jaca Book. First published 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Petracca, Luciana. 2006. Giovanniti e Templari in Sicilia. Galatina: Congedo. [Google Scholar]

- Pirri, Rocco. 1733. Sicilia Sacra disquisitionibus, et notitiis illustrata. Editio tertia emendata. Panormi: Apud Haeredes Petri Coppulae. First published 1644–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pispisa, Enrico. 1993. Messina, Catania. In Itinerari e centri urbani nel Mezzogiorno normanno-svevo, Atti delle decime giornate normanno-sveve (Bari, 21–24 ottobre1991). Edited by Giosuè Musca. Bari: Dedalo, pp. 148–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pispisa, Enrico. 1999. Medioevo fridericiano e altri scritti. Messina: Intilla. [Google Scholar]

- Pomar, J. Fernández José. 1976. La colección de Uceda de la Biblioteca Nacional. Nueva edición del catálogo de manuscritos. Helmántica 84: 475–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratesi, Alessandro. 1972. La scrittura latina nell’Italia meridionale nell’età di Federico II. Archivio Storico Pugliese 25: 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriquez, Maria Teresa. 2013. Cultura greca, libri e biblioteche in Messina. In Immagine e scrittura. Presenza greca a Messina dal Medioevo all’età Moderna (Messina, Museo Interdisciplinare Regionale”Maria Accascina”, 24 marzo–26 maggio 2013; Palermo, Palazzo Reale, 8 giugno–25 agosto 2013). Palermo: Fondazione Federico II, pp. 217–50. [Google Scholar]