Transforming Circe: Latin Influences on the Depiction of a Sorceress in Renaissance Cassone Narratives

Abstract

The raging groans of lions fill her palace –they roar at midnight, restless in their chains –and growls of bristling boars and pent-up bears,and howling from the shapes of giant wolves:all whom the savage goddess Circe changed,by overwhelming herbs, out of the likenessof men into the face and form of beasts.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See (Sowerby 1997; Wilson-Okamura 2010, esp. pp. 124–32). For Homer’s perceived value as a source of enlightenment in the Renaissance see (Poliziano 2007; Ford 2007). |

| 2 | For Pilato and the humanists see (Kircher 2014; Botley 2004;). Sowerby (1997, p. 186) notes that Pier Candido Decembrio’s partial revision (c.1440) and Lorenzo Valla’s prose translation of the Iliad (c.1444) did little to remedy Pilato’s inadequacies. |

| 3 | All Aeneid translations are from (Mandelbaum 1971). |

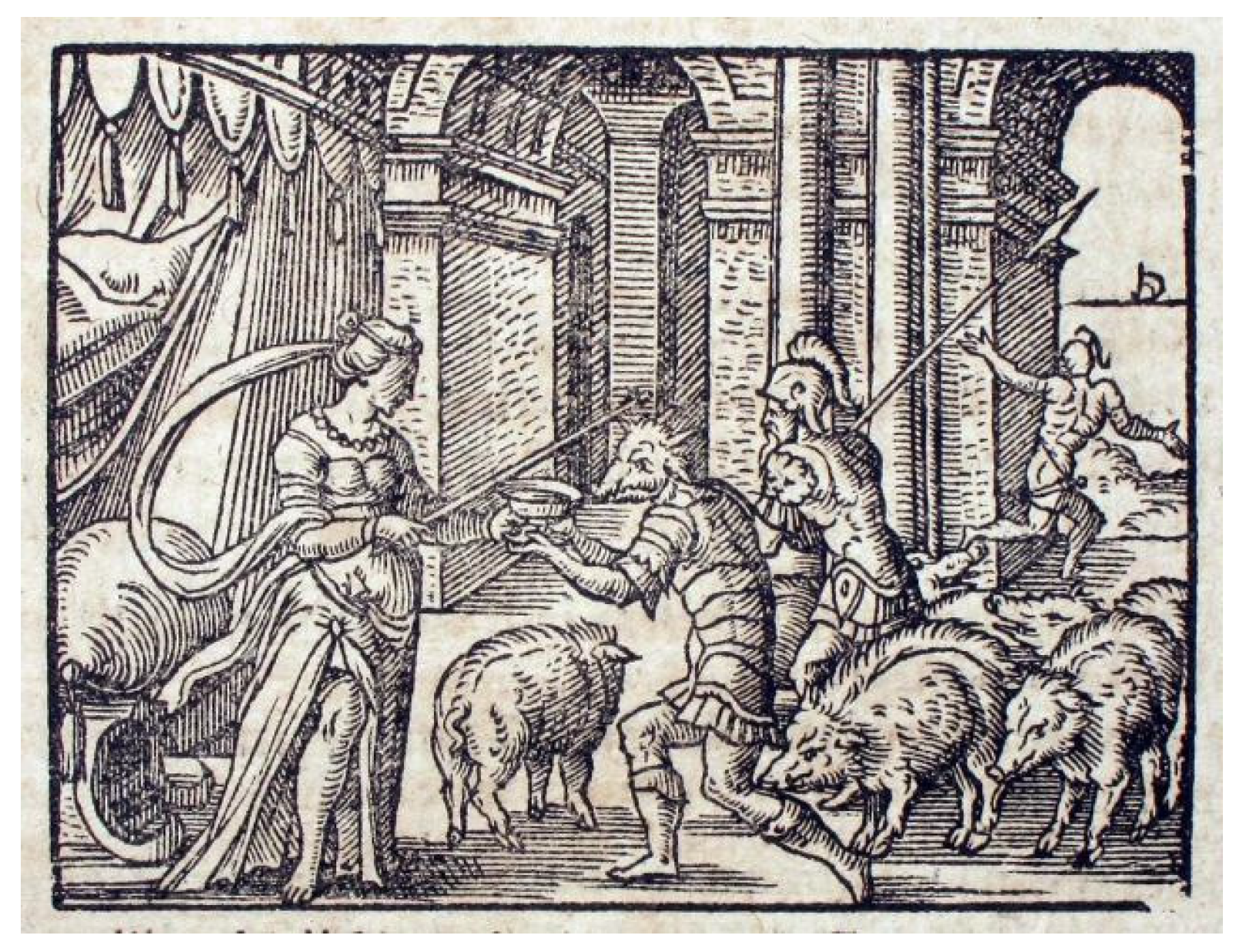

| 4 | Scholarship relevant to the treatment of Circe by Virgil and Ovid is vast; for bibliography and analysis see, for example, (Yarnall 1994, esp. pp. 79–91). For an expansive essay on Circe and transformation that addresses the work of other ancient writers (Plutarch, Pliny), see (Warner 1997). |

| 5 | For early quattrocento use of Diodorus see (Robathan 1932). |

| 6 | For the popularity of De mulieribus claris and Boccaccio’s other scholarly work during the Renaissance see, for example, (Bec 1984, esp. pp. 27, 112–14; Bozzolo 1973, pp. 22–43; Tournoy 1977). |

| 7 | All De mulieribus claris translations are by (Brown 2001). |

| 8 | For ancient hybrid imagery in the Circe story see (Brilliant 1995; Buitron and Cohen 1992). Di Febo (2019, p. 111) interprets the hybrid imagery in this miniature as visualizing Circe’s power to ensnare men by robbing them of their reason. For this miniature see also (Desmond and Sheingorn 2001, pp. 18–19). |

| 9 | See (Callmann 1974, p. 17; Miziolek 2006, p. 66). Apollonio’s paintings are dated decades prior to the woodcut of Circe used in many editions of De mulieribus claris printed in or after 1473. Unlike earlier French manuscript paintings, the Circe in these prints is modestly clothed and, without the identifying inscription, is indistinguishable from a human woman. It is perhaps noteworthy that Odysseus himself was never celebrated as an exemplar in contemporary uomini famosi (famous men) compendia or portrait cycles. |

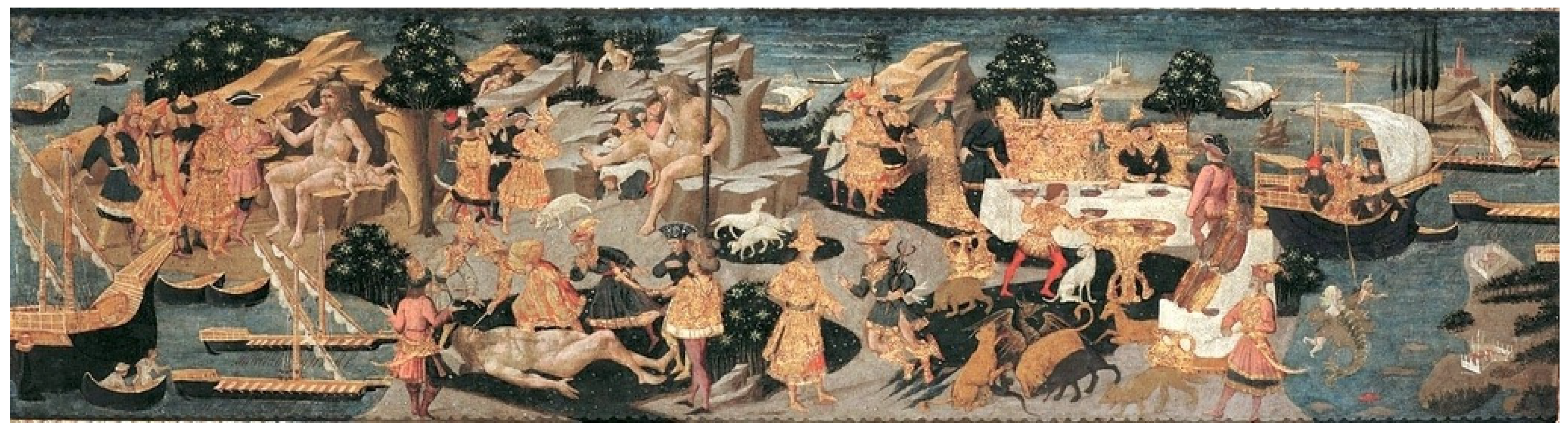

| 10 | For late medieval and early Renaissance views on occult magic see, for example, (Bailey 2017; Kieckhefer 2013). The conception of witchcraft as demonic power exercised by humans who had relinquished their souls to the devil only began to develop into a coherent theory in the middle decades of the 15th century; see, for example, (Duni 2007). |

| 11 | The multi-disciplinary scholarship relevant to witchcraft in the Early Modern period is vast; foundational is, for example, (Russell 1972) and (Cohn [1975] 2000); see also (Stephens 2001). Interest in, and persecution of, witches was fueled by the publication of works such as the Malleus maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) in 1486; see (Broedel 2003). For Circe in the sixteenth-century visual arts see (Zika 2007, pp. 133–55; Yarnall 1994, pp. 99–144). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Giorgio Vasari, sixteenth-century painter, biographer, and historian, describes the decoration of cassoni as including “fables taken from Ovid and other poets, or rather stories told by the Greek and Latin historians” (Vasari 1878, pp. 148–49) |

| 14 | For the later, less accomplished work, see (Callmann 1974, p. 17). |

| 15 | On the far right of the panel Odysseus’ ship leaves Circe’s island and the men have an encounter with the monstrous Scylla. |

| 16 | For the long association of Hermes and the caduceus with one or more of these qualities see, for example, (Freedman 2011; Schlam 2009, p. 15; Friedlander 1992; Shelmerdine 1986, pp. 49–63). For moly see, for example, (Clay 1972; Stannard 1962). |

| 17 | All Odyssey translations are by (Lattimore 1967). |

| 18 | There is also a stag and a white dog; it is not clear whether they are intended to be read in conjunction with the beasts or with the servant. |

| 19 | All Metamorphoses translations are by Mary M. Innes (Ovid 1955). |

| 20 | This is Mandelbaum’s translation of Virgil; Jon Solomon (Boccaccio 2011) translates this passage in the Genealogia deorum gentilium as “From here the angry roaring of lions battling their bonds and bellowing under the late night, and bristly swine and bears in their pens rage, and the bodies of great wolves howl—once human in appearance, the cruel goddess with powerful herbs, Circe, cloaked them with the faces and backs of beasts.” |

| 21 | For more evidence of Apollonio’s use of Virgil’s characterization of the Polyphemus story see (Franklin 2018; Miziolek 2006). For the inclusion of non-Homeric material in Apollonio’s Odyssey panels that was introduced to resonate specifically with Early Renaissance viewers see (Zerba 2017). |

| 22 | He should not, therefore, be mistaken for the leader of the doomed reconnaissance party, none of whom attempts to intimidate Circe. |

| 23 | It is worth noting that the loom was not used for purposes of contradistinction in antique vase paintings of Circe and Penelope, where both women were frequently depicted with this archetypal domestic object. See, for example, (Brilliant 1995, pp. 171–72). |

| 24 | Apollonio renders the appearances of both Polyphemus and Circe more human than does Homer, a change that presumably made Odysseus’ fantastic adventures, and the lessons to be derived from them, more relatable to quattrocento viewers. Homer, for example, says that the cyclops is a “monstrous wonder … not like a man … but more like a wooded peak of the high mountains” (Od. IX.190–92). |

| 25 | For this and other Camilla/Lavinia cassone narratives see (Franklin 2013; Baskins 1998, pp. 75–102). |

| 26 | Spalliere were larger than cassoni and made to set into a wall above a bed or other piece of furniture. See (Olsen 1992). |

| 27 | For Renaissance Griselda imagery see (Baskins 1991). |

| 28 | See, for example, Leon Battisti Alberti, I libri della famiglia, c.1430; and Francesco Barbaro, De re uxoria liber, 1416. |

| 29 | Scholarship addressing the nature, roles, and expectations of (most) upper-class women, especially those living in quattrocento republics (as opposed to those groomed to be the consorts of princes) is vast. See, for example, (Panizza 2000; Wiesner 1993; Klapisch-Zuber 1988). Of course, there were exceptional women who achieved measures of public success in spite of legal, political and social strictures; see, for example, (Robin 2013). |

| 30 | In addition to building and stocking a ship for Odysseus and his men, Circe instructs him on withstanding the Sirens, warns him of the dangers presented by Scylla and Charybdis; admonishes him not to harm the cattle of the sun on Thrinacia; and directs him to seek the advice of Teiresias in the underworld. |

References

Primary Sources

Boccaccio, Giovanni. 2001. Famous Women. Edited and Translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge, MA and London: I Tatti Renaissance Library, Harvard University Press.Secondary Sources

- Bailey, Michael D. 2017. Fearful Spirits, Reasoned Follies. The Boundaries of Superstition in Late Medieval Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L. 1991. Griselda, or The Renaissance Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelor in Tuscan Cassone Painting. Stanford Italian Review 10: 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L. 1998. Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L., Adrian W. B. Randolph, and Jacqueline Marie Musacchio. 2008. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Boston: Isabella Steward Gardner Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Bec, Christian. 1984. Les livres des Florentins (1413–1608). Florence: Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccio, Giovanni. 1965. The Fates of Illustrious Men. Edited and Translated by Louis Brewer Hall. New York: Frederick Ungar. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccio, Giovanni. 2011. Genealogy of the Pagan Gods. Edited and Translated by Jon Solomon. Cambridge, MA and London: I Tatti Renaissance Library, Harvard University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Botley, Paul. 2004. Latin Translation in the Italian Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowra, Cecil Maurice. 1988. The Odyssey: Its Shape and Character. In Homer’s The Odyssey. Edited by Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzolo, Carla. 1973. Manuscrits des traductions françaises d’oeuvres be Boccace, XVe siècle. Padua: Antenore. [Google Scholar]

- Brilliant, Richard. 1995. Kirke’s Men: Swine and Sweethearts. In The Distaff Side. Representing the Female in Homer’s Odyssey. Edited by Beth Cohen. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–74. [Google Scholar]

- Broedel, Hans Peter. 2003. The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft, Theology and Popular Belief. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, Leonardo. 2010. Rerum suo Tempore Gestarum Commentarius. In The Classical Tradition. Edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most and Salvatore Settis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buitron, Diana, and Beth Cohen. 1992. The Odyssey and Ancient Art: An Epic in Word and Image. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Edith C. Blum Art Institute, Bard College. [Google Scholar]

- Callmann, Ellen. 1974. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clay, Jenny. 1972. The Planktai and Moly: Divine Naming and Knowing in Homer. Hermes 100: 127–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Norman. 2000. Europe’s Inner Demons: The Demonization of Christians in Medieval Christendom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, Marilynn, and Pamela Sheingorn. 2001. Queering Ovidian Myth. Bestiality and Desire in Christine de Pizan’s Epistre Othea. In Queering the Middle Ages, Medieval Cultures 27. Edited by Glenn Burger and Steven F. Kruger. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Di Febo, Martina. 2019. Circe e Medea: La divergente moralizzazione della maga nell’Ovide moralisé. In Ore legar populi”: Le “Metamorfosi” di Ovidio e la loro disseminazione letteraria e iconografica, Medioevo e Rinascimento: Testi e studi. Edited by Margherita Lecco. Genoa: University of Genoa, pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Duni, Matteo. 2007. Under the Devil’s Spell: Witches, Sorcerers and the Inquisition in Renaissance Italy. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Philip. 2007. De Troie à Ithaque: Réception des Épopées Homériques à la Renaissance. Geneva: Librairie Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2006. Boccaccio’s Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society. Burlington and Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2010. Boccaccio’s Amazons and Their Legacy in Renaissance Art: Confronting the Threat of Powerful Women. Woman’s Art Journal 31: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2013. Constructing Camilla as ‘Other’ in Renaissance Visual Narratives. Explorations in Renaissance Culture 39: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2018. Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings. Humanities 7: 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, Luba. 2011. Mercury à la David in Italian Renaissance Art. In Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia. Series 5; Vol. 3, Il futuro di una tradizione: Formazione d’eccellenza nell’Europa contemporanea. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore, pp. 135–57, 281–84. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, Walter J. 1992. The Golden Wand of Medicine: A History of the Caduceus Symbol in Medicine. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kieckhefer, Richard. 2013. The specific rationality of medieval magic. In New Perspectives on Witchcraft, Magic and Demonology: Demonology, Religion, and Witchcraft. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, vol. 1, pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Timothy. 2014. Wrestling with Ulysses: Humanist Translations of Homeric Epic around 1440. In Neo-Latin and the Humanities: Essays in Honour of Charles E. Fantazzi. Edited by Luc Deitz, Timothy Kircher and Jonathan Reid. Essays and Studies 32. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. 1988. La famiglia e le donne nel Rinascimento a Firenze. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore, Richmond. 1967. The “Odyssey” of Homer. New York and London: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum, Allen. 1971. The “Aeneid” of Virgil. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miziolek, Jerzy. 1996. Soggetti classici sui cassoni fiorentini alla vigilia del Rinascimento. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Miziolek, Jerzy. 2006. The ‘Odyssey’ Cassone Panels from the Lanckoroński Collection: On the Origins of Depicting Homer’s Epic in the Art of the Italian Renaissance. Artibus et Historiae 27: 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Jennifer Klein. 1992. Apollonio di Giovanni’s “Aeneid” Cassoni and the Virgil Commentators. Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 26–47. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40514346 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Oldfather, Charles Henry. 1933. Diodorus of Sicily. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Christina. 1992. Gross Expenditure: Botticelli’s Nastagio degli Onesti Panels. Art History 15: 146–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovid. 1955. Metamorphoses. Edited and Translated by Mary M. Innes. London and New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Panizza, Letizia, ed. 2000. Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society. Oxford: Legenda. [Google Scholar]

- Pepin, Ronald E. 2008. The Vatican Mythographers. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poliziano, Andrea. 2007. Oratio in Expositione Homeri. Edited by Paola Megna. Edizione Nazionale dei testi umanistici 7. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura. [Google Scholar]

- Robathan, Dorothy M. 1932. Diodorus Siculus in the Italian Renaissance. Classical Philology 27: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, Diana. 2013. Women on the Move: Trends in Anglophone Studies of Women in the Italian Renaissance. I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 16: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. 1972. Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schlam, Carl C. 2009. The Metamorphoses of Apuleius: On Making an Ass of Oneself. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schubring, Paul. 1923. Cassoni, Truhen und Truhenbilder der Italienischen Frühhrenaissance. Leipzig: Hiersemann. [Google Scholar]

- Shelmerdine, Susan C. 1986. Odyssean Allusions in the Fourth Homeric Hymn. Transactions of the American Philological Association 116: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowerby, Robin. 1997. Early Humanist Failure with Homer. International Journal of the Classical Tradition 4: 37–63, 165–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannard, Jerry. 1962. The Plant Called Moly. Osiris 14: 254–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Walter. 2001. Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tournoy, Gilbert, ed. 1977. Boccaccio in Europe. Louvain: Louvain University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1878. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori. Edited by Gaetano Milanesi. Florence: Sansoni, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Marina. 1997. The Enchantments of Circe. Raritan 17: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, Merry E. 1993. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Okamura, David Scott. 2010. Virgil in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall, Judith. 1994. Transformations of Circe. The History of an Enchantress. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zerba, Michelle. 2017. Renaissance Homer and Wedding Chests: The Odyssey at the Crossroads of Humanist Learning, the Visual Vernacular, and the Socialization of Bodies. Renaissance Quarterly 70: 831–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zika, Charles. 2007. The Appearance of Witchcraft. Print and Visual Culture in Sixteenth-Century Europe. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franklin, M. Transforming Circe: Latin Influences on the Depiction of a Sorceress in Renaissance Cassone Narratives. Arts 2023, 12, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030105

Franklin M. Transforming Circe: Latin Influences on the Depiction of a Sorceress in Renaissance Cassone Narratives. Arts. 2023; 12(3):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030105

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranklin, Margaret. 2023. "Transforming Circe: Latin Influences on the Depiction of a Sorceress in Renaissance Cassone Narratives" Arts 12, no. 3: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030105

APA StyleFranklin, M. (2023). Transforming Circe: Latin Influences on the Depiction of a Sorceress in Renaissance Cassone Narratives. Arts, 12(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030105