Abstract

The monastery of Holy Savior has been the subject of much scholarship, but the liturgical reform requested by King Roger II of Sicily and carried out by the first archimandrite, Luke of Rossano, and the latter’s struggle to establish seemly equipment, has been largely neglected. Given its potential relevance for the material setting of the monastery’s early manuscript collection through the middle of the twelfth century, this seems an oversight. Art historians have repeatedly claimed that the monastery’s lofty status could have enabled the spread of Byzantine models to Norman Sicily, especially in relation to figurative arts and manuscript decoration. This paper discusses the same assumption from the opposite perspective. It explores the main tendencies of manuscript decoration at San Salvatore based on the extant evidence from the monastery’s early collection. Building on the paleographical and codicological observations provided in the past decades (mostly by philologists), I examine the manuscripts in terms of decorative practice and artistic culture.

1. Introduction

The former monastery of Holy Savior, which hosted Greek Christian monks and stood on the harbor arm facing Messina (Figure 1), is renowned for its manuscript collection, 177 items of which are now kept in the city’s public library, the Biblioteca Universitaria ‘Giacomo Longo’, with the label ‘Fondo San Salvatore’ (or Messanenses graeci) (Matranga 1887; Foti 1989; Rodriquez 2013). Several other codices from the monastery are scattered beyond Sicily, many in libraries across Europe. Displacement and dispersion were the outcome of the monastery’s dismantlement around 1540, when the monks were forced to abandon their house to Spaniard squads. A fortalice soon replaced the convent at the port’s mouth.1 Eventually, in 1549, the church of Holy Savior perished too, in a fire that began in the magazine which had been built nearby. The medieval monastery had been established in 1122 (tradition holds that a monastery existed there even before, though this is subject to debate), but the church itself was only completed in 1131/32. Calabrian monks were called to Messina from the monastery of the Virgin Nea Odigitria in Rossano; the founder, Father Bartholomew of Simeri, was originally appointed to Messina, but he died in 1130, and so the mission passed over to his disciple Luke. In 1133, King Roger II elevated Holy Savior to the status of Archimandritate, that is, the Mother House of a group of Greek monasteries and minor foundations on both sides of the Strait of Messina. To mark the monastery’s promotion, Roger designated Holy Savior a Royal Monastery (von Falkenhausen 1994; Tranchina 2016).

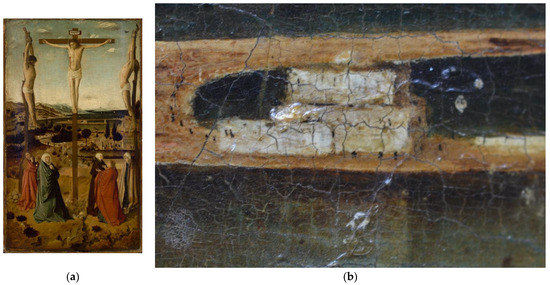

Figure 1.

(a) Antonello da Messina, Crucifixion (1450s or 1460s), Sibiu, Brukenthal Collection: the panel painting features the representation of the medieval monastery of Holy Savior de lingua in the background (b) (credit: Brukenthal Museum).

After the monks’ displacement in the sixteenth century, the large manuscript collection belonging to the venerable institution survived. Or rather, it was rescued: the books followed their fleeing owners, who temporarily took up residence at La Misericordia, where they piled and provisionally stored their manuscripts2 until a new monastery was built in the outskirts of Messina, at the mouth of the Annunziata brook (the ruins are visible today inside the Museo regionale) (Barbaro Poletti 1985–1986), with a new library, which lasted up until its requisition by the Italian State. Early modern inventories attest to the increasing loss of items from the sixteenth century—due not in small part to the longing for evidence of Greek written culture at the beginning of the Catholic Reformation, and in particular testimonies of the Fathers supporting the Catholic claim for Roman tradition (Mercati 1935). It was around this time that the fame of the monastery—Magno Monasterio remained its epithet even when the new seat (San Salvatore dei Greci) was inaugurated as the Mother House for the whole Basilian order—began to be eclipsed by the fame of its manuscripts, which suited the improvement of theological knowledge, liturgical praxis and humanistic erudition.

At the eve of modern nations, as Greek antiquity entered the bourgeois educational agenda across Europe, a new wave of interest in Greek medieval manuscripts arose, triggered this time by the consolidation of philology as an academic science. The fame of Holy Savior’s scriptorium as a hub for proto-humanists grew in modern times. This was partly because of the assumption that the ‘codices pulchros, et diversos numero trecentos’ recorded in Priest Scholarios’ 1114 testament as a donation to the Greek monastery of Bordonaro were headed to the namesake monastery at the mouth of the port (Scinà 1824, p. 17; see also Amari 1858, p. 400, note 3), but also because of Otto Hartwig’s claim that Holy Savior had played a crucial step in the early reception of Greek classics in the West (Hartwig 1886). Beyond this misunderstanding, such records were reappraised as sources for the study of the ‘resurgence of Hellenic antiquity’—a label that rhymed not by chance with both Hellenic Resurgence and with the ‘Risorgimento’ of the Italian nation (Lo Parco 1909). Even Giovanni Gentile, who became involved in the cultural program of the Fascist regime, enthusiastically reviewed the topic while teaching in Palermo, and collaborated with La Critica, the journal directed by Benedetto Croce, the most prominent Italian intellectual of the early twentieth century (Gentile 1910).

In his studies of the inventories of San Salvatore’s former manuscript collection, Giovanni Mercati moved beyond celebrating South-Italian Greek monks as pioneers in rescuing classical texts. Crucially, he acknowledged ‘an almost completely ecclesiastical library’, characterised by a ‘poor richness’ (Mercati 1935, pp. 56, 58). This judgement, strict as it is, seems the safest introduction to the evidence that will be discussed in the following pages. It is particularly applicable to the practice of decoration at the Holy Savior’s book workshop, as seen in the choices made by the first generation of scribes/decorators who, as is argued below, may have pursued a ‘poor richness’ in their work, especially in the case of the manuscripts created only for their own community at the lingua. Despite this, the post-World-War-II scholarship developed the idea of an influence exerted by Byzantine illumination irradiating from the major Greek monasteries of Southern Italy, and therefore a line of transmission that was parallel to the decorative endeavors performed by Byzantine craftsmen at the service of the Norman kings of Sicily in Palermo.3

This article reassesses the long-lasting contention that Byzantine artists could have been ordinarily active at Holy Savior’s scriptorium, practicing figural decoration in a variety of codices and subjects from sacred imagery to historical picture narratives. Recently, this idea has led to some hypotheses about the most famous illustrated manuscript dating from the early times of the Sicilian Kingdom: the lavishly decorated copy of the Byzantine Chronicle of John Skylitzes (Matr. Vitr. 26-2) (Tsamakda 2012; Marchetti 2014; Boeck 2015). This manuscript—in which the work of Byzantine illuminators appears side by side with that of their ‘Western’ counterparts—is currently the object of a new study by the core team of the MABILUS project (https://mabilus.com/en/ accessed on 5 January 2023), which is investigating the origins of the extensive pictorial cycle depicted in the Matritensis. Working within the same framework but taking a different direction, this paper sheds light on the activity of Holy Savior’s book workshop. On the basis of material and production evidence, it puts forward arguments for the discussion of book illumination in the multifaceted historical landscape of Norman Sicily, and especially in the Greek-speaking monastic milieu of the Straits area.

2. Results and Discussion

This section details the results of an extensive analysis of a corpus of twelfth-century decorated manuscripts attributed to the Holy Savior’s book workshop, now kept in the Biblioteca Universitaria in Messina and the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, as well as in other major European libraries that I was able to visit (among them the Bibliothéque Nationale de France (BnF) and the Bodleian Library, Oxford). The attributions were made mostly by philologists and paleographers on the basis of arguments pertaining to provenance from the monastery’s library, consistency of writing, and marks on the books.

The results are divided into three sections, each of which deals with a major issue presented by the material. The first is the evidence that figural decoration was only a minor concern in the making of the monastery’s early manuscript collection. The second is the crossover between scribes and decorators, as well as some exceptions which point to the pursuit of a consistent standard of non-figural decoration (the latter being a proper trend in the monastery’s book workshop). The third is the variety of traditions that inform aniconic decoration in coeval Sicily, possibly prompted by the proximity of monumental endeavors, such as mosaic decoration implemented in Palermo as well as in Messina, and by the spreading of trends and patterns from the local multicultural landscape, encompassing the hybrid outcomes of the Palatine culture as well as the proper Islamic(ate) tradition.

2.1. Scanty Evidence for Figural Decoration

Late twentieth-century scholarship has made it clear that the remarkable figurative decoration in the ‘Fondo San Salvatore’ pertains to book items that had reached the Holy Savior de Lingua as either a donation or as part of the early equipment ‘inherited’ by the first igumen, Archimandrite Luke (d. 1149) from the book collection of the Odigitria’s Monastery in Rossano and aquired from afar. The latter seems to be the case of the Imperial Menologion, Mess. gr. 27 (February–June) (Figure 2), connected by Nancy Patterson to the Berlin gr. Fol. 17 (July–August) and possibly dating from the middle quarters of the eleventh century (Patterson Ševčenko 1984, 1990). Patterson believed that the twenty ‘hybrid styled’ miniatures were painted by a Latin artist trained with Byzantine models—his Western origin was ventured by other authors4—but in fact the script is the so-called Perlschrift, the features of which are consistent with classic Constantinopolitan examples from the late-Macedonian period (Image and Scripture 2013, p. 146 (entry by M.T. Rodriquez)). It therefore seems improbable that the decoration was carried out far away from the workshop where the manuscript was created, or even with a major lapse of time in between.

Figure 2.

Anonymous Byzantine illuminator, The Holy Three Young Men (mid-11th century, or second half), Mess. gr. 27, f. 317v, detail (credit: Biblioteca Universitaria Regionale ‘Giacomo Longo’).

The Octoechos Mess. gr. 51 can be given a later date, perhaps in the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth. More interestingly, it can also be ascribed to either a Palestinian or Cypriot milieu (Weyl Carr 1987, p. 78; 1989; Bucca 2011, pp. 43–59; Image and Scripture 2013, p. 150 (entry by M.T. Rodriquez)). It may have arrived in Messina because of the multiple connections between the Straits and the Outremer territories established over the course of the Central Middle Ages. Although in cases such as this there is little reason to object to the possibility that they could have been regarded as potential models for local painters, since their presence within the monastery (and in particular the Menologion volume) must have been very early, they certainly do not come out of Holy Savior’s book workshop.

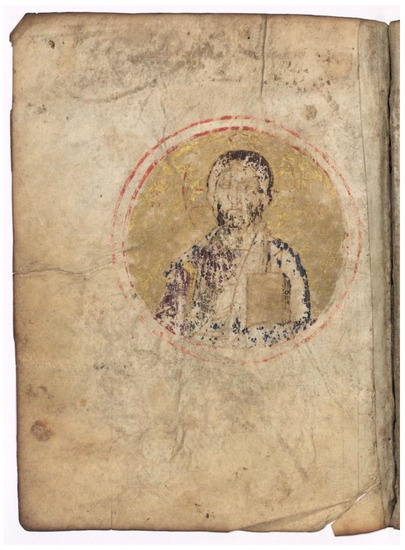

For this earliest phase of manuscript production at the lingua, the one major example of figurative decoration examined here is the medallion bearing the bust of Christ Pantokrator in a psalter ascribed to the monastery, Vat. Barb. gr. 322, f. 117v (Figure 3), and which is painted on a single leaf inserted between the second and the third quire (see Hutter 2022, pp. 755, 757). This means that it is not strictly related to the manuscript’s overall decoration in carmine (as it is not embedded in such ornaments), though the latter should be attributed to the chief decorator in the workshop, who was extremely skilled with pen (see below). The painting is almost effaced, especially in the area shaping Christ’s face and pallium, where the fall of pigments has uncovered the underlying drawing. This drawing seems to have been drafted with ease by a skilled Byzantine hand, which sketched the bust of Christ on an empty sheet and filled the background within the compass circle with gold leaf, along with the book he depicted in Christ’s hand. The miniature was then retouched with carmine so as to frame the golden medallion and to apply the nimbus and the nomen sacrum. No further requests were made of the artist. Indeed, it appears he was asked to make—or occasionally made—an image of Christ that followed the standard iconography, perhaps intended to complement the psalter at its origin: it is found between the quires containing the end of the first and the beginning of the second part of the psalter, according to the Byzantine usage, and the decorated strip at the side (psalm 77) is the only one in the entire manuscript displaying the gold leaf. Such an insertion may have been intended as a proper icon meant to receive the reader’s prayer (Parpulov 2017, p. 304), and it also matches the triumphal tone of the following psalter, which praises God’s mighty power.

Figure 3.

Anonymous painter, Byzantine (?), bust of Christ Pantokrator (around mid-12th century), Vat. Barb. gr. 322, f. 117v (Figure 109) (Tsamakda 2017, Figure 109).

Neither the early ownership of this psalter nor its provenance is known. The only thing that can be inferred is its completion in Holy Savior’s workshop: the writer has been identified with Monk George, who was one of the monastery’s copyists during the central quarters of the twelfth century. The manuscript’s decoration seems to be the result of the occasional participation of a painter rather than George himself, who would have surely provided a more elaborate ornamentation for framing Christ’s bust. The autonomy of both endeavors complicates the evaluation of their coexistence in the same codex, though a contemporaneous intervention by an independent painter cannot be excluded. This seems to suggest that there were Byzantine artists capable of miniature painting active in Palermo and Messina in the years when the Royal Palace on the Straits and Holy Savior’s church were furnished (also with the intervention of mosaicists).

2.2. Did Copyists Identify with Decorators? Sampling Rubricator

Because of the rarity of painted illumination and figurative complements, as well as the preeminence of philological criteria in the enquiry of Holy Savior’s manuscripts, there has been a lack of interest in developing art-historical tools and methods. On the one hand, compelling questions (Where does a manuscript come from? Who is the decorators?) can hardly be answered by relying on such meager evidence. On the other hand, the superabundance of writing in the mise-en-page of these manuscripts calls for paleography as the preliminary expertise applied to study objects. This has resulted in manuscript attributions being made to the Straits area—and specifically to Holy Savior—on the basis of writing style or, in some cases, of particular features that point to specific individuals who prove to be active in that area. Coming from this perspective, only very few authors have developed a specific interest in the question of ornamentation, mostly intended as an auxiliary tool to strengthen the link of scattered collection items with each other and to clarify them. In the Table 1 below, the benefits of such a focused approach can be easily grasped.

Table 1.

Manuscripts decorated by the chief decorator in Holy Savior’s workshop, the ‘Rubricator’.

The prolegomenon of any further observation is the grouping of scribes (see column 6) according to the established attribution of manuscript items—books or book sections—by paleographers. A variety of further questions soon arise—first and foremost about artistic practice and aesthetics, particularly in relation to the process of decoration and its aesthetic principles, if there were any. As previous scholarship has broadly contended that pen decoration could be easily ascribed to copyists themselves, the core task is to verify this assumption. If that is not the case, decoration shall be pursued as a complementary phenomenon of book making that has to be understood on its own. The answers provided will then lead to the question of models and patterns implemented in the monastic workshop, and whether or not the ornamental trends can be interpreted as a testimony of visual culture, enriching the assorted palette of Norman Sicily with the ‘hue’ of Greek Christians.

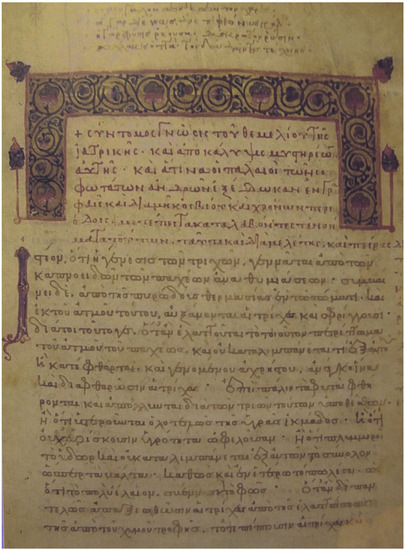

The work of a major decorator in Holy Savior’s book workshop is recognizable in a few manuscripts kept in Messina, as well as some in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. However, the list could certainly be improved in parallel with some further exploration. The masterpiece is the Mess. gr. 32, which contains the homilies of St. Gregory of Naziantius, copied by Monk Bartholomew for Igumen Paphnutius of the Holy Savior at Bordonaro (a namesake monastery to the south of Messina), in 1150/51. It is probably because of this ‘external’ destination, and possibly at the request of same Paphnutius, that five quires at the beginning of the manuscripts featured painted decoration and gold leaf; one should recall here that Bordonaro already had a prominent book collection, donated by Priest Scholarios (i.e., Monk Savas) in 1114 (see above). The quality of gilded and painted pylai is not that refined; since this is not paralleled in the monastery’s collection, there is no possibility of attributing it or associating it with further instances. From the sixth quire on, the decoration consists of very refined carmine stripes en reserve (ornaments appear to be formed by sparing empty spaces between the carmine fields), as well as of initials that resemble the Middle-Byzantine so-called Laubsägestil, yet characterized by ‘spared’ motifs, too.

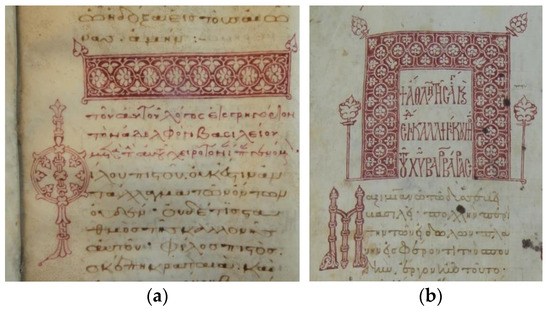

Shortly after the foundation of the monastery in the fourth decade of the twelfth century, this style became the standard in the early workshop. Its origin has been traced in great detail by Irmgard Hutter. I propose to draw attention instead to how this standard is applied at Holy Savior, starting with the most impressive figure in the team. He stands out because of the neatness of his profiles, the perspicuity of his decoration, the strength in his hand which results in the absolute firmness of traits, even in minor details, and for his use of some distinctive motifs, above all the net-like carpets (Figure 4). Because of his primacy and the remarkably vibrant hue and density of the carmine dye used, I propose to call him Rubricator, after the function of carmine initials and pylai, that is, of indexing in red the chapters or the most significant manuscript sections (rubricatio, in Latin).

Figure 4.

Examples from the Rubricator’s decorative production (a) Mess. gr. 32, f. 73; (b) Mess. gr. 37, f. 2.

His hand can be tracked across the sixteen manuscripts listed in the table above, of which six—almost half the total number—were written by George, most certainly a monk from Holy Savior de lingua, who subscribed Vat. gr. 974, a small codex with Constantine’s and Helen’s bios that was found in the monastery during the fourteenth century. There he presents himself as fulfilling the request of his ‘father’ (Foti 1989, p. 39; Hutter 2022, vol. 2, pp. 748–50), meaning the spiritual authority above him—a label that fits the Messina Archimandrite well (see Lucà 2016, pp. 252–53). Based on George’s writing style as displayed in Vat. gr. 974, a group of seven further codices has been attributed to him.5 Given the proportion in the latter group (five display the Rubricator’s decoration), as well as that in the table above, the correspondences between the Rubricator and (monk) George, the copyist, led Hutter to hypothesize that both are one and the same person.6 This is convincing, and also allows for one further assumption: George’s involvement as drawer must be acknowledged in those further manuscripts, the writing of which appears to be drafted by other hands. Those other copyists, especially Dionysios and Theodore and Monk Bartholomew, are clearly related to the production of Holy Savior’s workshop, and Dionysios ὁ χθαμαλός (i.e., ‘the low’) even appears to be the chief writer—protokallígraphos—during the fourth decade of the twelfth century (Lucà 2016, p. 261), despite his humbling predicate.

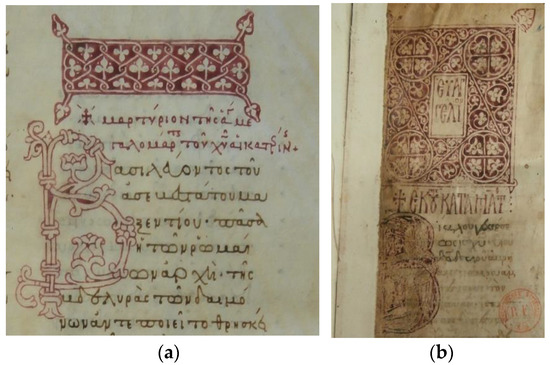

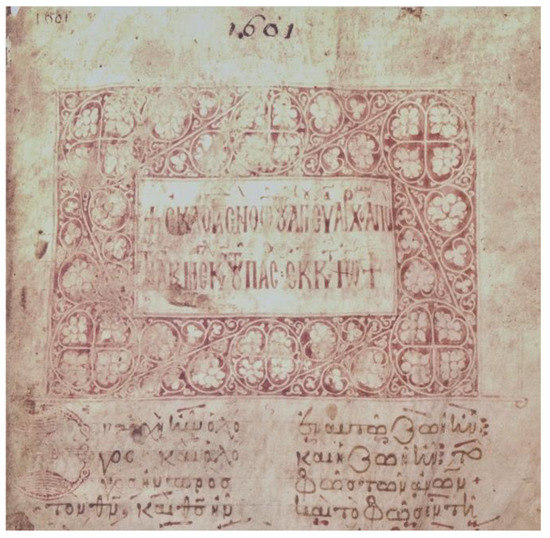

The Rubricator/George is therefore an instance of a copyist/drawer who, on the one hand, attends to the completion of the manuscripts he has written, but on the other hand is asked to manage the carmine ornamentation of books made by his fellow copyists. He enriches the texts’ beginnings and headings, produces decorated letters, large and small pylai, at times even independently from the initials nearby, as is the case in the Mess. gr. 69, where a second hand (less talented but not less creative and practiced) draws with a thinner trait (Figure 5a), or in the Vat. gr. 1349. The Rubricator was possibly training fellow monks; or he was at least flanked by skilled and ambitious companions, such as the one who illustrated a Gospel in Paris, Suppl. gr. 1266 (Figure 5b), in which the first pyle can be directly connected to George’s Lectionary Vat. gr. 1601 (Perria 1974; Hutter 2022) (Figure 6), or San Salvatore’s Euchologion in Oxford (Bodleian Library, Auct. E. 5.13), so far ascribed to Rossano, Trigona or to Messina itself (Hutter 1982, pp. 109–10).

Figure 5.

One of Rubricator’s collaborators and an epigon: (a) Mess. gr. 69, f. 82; (b) Suppl. gr. 1266, f. 1.

Figure 6.

Lectionary written by (monk) George, Vat.gr. 1601, f. 1 (Hutter 2022).

In conclusion, the evidence presented here brings into question the general assumption that, for each and every manuscript, drawers can be identified with copyists. As has been shown, copyists can provide decoration on their own, but when higher ambitions are at play (external commission, Archimandrite’s demand and/or equipment for the needs of communal liturgy), more experienced figures are selected in the group in order to carry out the task. Painting and gilding are occasional, and it is not yet clear whether or not painters were deliberately selected from outside the monastery.

2.3. Assembling the Collection: A Note on Contents

As will be shown in this section, the Prophetologion (Lectionary of Prophets’ pericopes) Vat. Barb. gr. 446 almost certainly comes from the early liturgical dotation of San Salvatore’s church. The Euchologion (Book of Prayers, that is, texts for the celebration of sacraments and the Divine Liturgy) Oxon. Auct. E. 5. 13 comes from the Lingua in Messina, too, and reveals the rites performed in the monastic major church, dedicated to Christ the Savior (Jacob 1980; Hutter 1982, pp. 109–10). The lectionary Vat. gr. 1601 and the Gospels in Paris share some features and seem to be intended as paired volumes, though there is a lack of definite evidence for this. In any case, the Rubricator appears to be at work on a presentational manuscript set intended to foster celebration of a solemn liturgy through the handling of dignified books.

The other manuscripts listed, as well as some further items reviewed for the sake of this research are ascetic books, homiliaries, menologia and menaei (books containing the saints’ lives divided into months and corresponding to the respective feasts of the liturgical calendar). My argument is that this means most of these books were created for serving the liturgical agenda of the new monastic community.7 Indeed, the outcome of such a production appears to be preconized in the Preface to the Holy Savior’s typicon (Book of liturgical rules) that the monastery’s first hegumen, Archimandrite Luke, wrote as a sort of memorandum of the great endeavor he was pursuing in setting up the new monastery, intended from the beginning as Mother-House for a great number of Sicilian and Calabrian monks.

Luke evokes his deeds, the former involvement of his mentor, Bartholomew of Simeri, and the primary concern of a liturgical reform (‘correction’), which was mainly directed toward establishing melurgy (i.e., liturgical chant) according to the cathedral usage of Constantinople. He also carefully describes how San Salvatore’s book collection was shaped:

‘We collected many beautiful books pertaining to our own sacred writings, totally familiar to us, as well as [other books] not pertaining to our sacred writings. We collected the composition of [St. John] Chrysostom, of the great father Basil, of Gregory the very great Theologian, and of his namesake [Gregory] of Nyssa, and of the other fathers and teachers inspired by God. We collected other compositions and works of ascetic writers, both the simple ones and also the more advanced, as well as historical works and other treatises from the outer and alien courtyard, works such as strive after the sacred knowledge. Other books [we obtained] which teach us about the lives of the fathers and contain the paraphrases which that most wise Symeon [Metaphrast] the Logothete composed while moved by the most sacred Spirit’.(Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents 2000, p. 645)

Codicological data confirm the analogy between an early menological collection from the Patir monastery—items of which are now in the Vatican Library—and the volumes of Messina menologion (Mess.gr. 69, 37 and 5: all copied by Monk George and one of his pupils, and all decorated by the Rubricator). This would suggest that the origin of the standard metaphrastic menologion implemented at the Lingua was in Rossano.8 Its implementation at Messina by Luke and his disciples dates from the moment that Holy Savior’s book workshop was established, in the second quarter of the century. It is not by chance that the manuscripts from Rossano reveal the origin of carmine decoration; it appears to have been executed in the Straits, and thus in the acquaintance of the Patir monks, who had learned from Byzantine Blütenblattstil exemplars (see Weitzmann 1935, pp. 22–32), and possibly from the group of manuscripts decorated by John Tzoutzounas (Hutter 1980, p. 344).

There is also a homiliary cycle of which just one item remains (Mess.gr. 3 B). Its codicological and decorative characteristics are matched by the first volume of a homiliary per annum (Mess.gr. 63) as well as another section (Mess.gr. 2, ff. 216–292v). Two volumes also survive from the hymnological maeneum (September–October), one of them decorated by the Rubricator (Mess.gr. 137) and written by the Metaphrast’s scribe; the other decorated by one of the Rubricator’s fellows, who also appears in said Metaphrast of November. Here it seems possible that the writer was also responsible for the decoration.9 It is therefore not implausible that an early core set of manuscripts auxiliary to ritual practice was commissioned by Luke at the earliest phase, and then implemented or even replicated at his death in 1149, to fulfil not only ‘home needs’, but also those of some of the other major monasteries within the group led by the Mother House.

In addition, Luke’s commentary on the Patristic collection is mirrored both by a copy by Gregory of Naziantius (Mess.gr. 64) and one by Basil the Great, the latter being decorated by the Rubricator and a second hand, with which a Vatican Climacus (Vat.gr. 1635) can be associated too. The note on medical writings in another passage of the Preface fits well the fact that there was a hospital (nosokomion) in San Salvatore’s outer precinct, and two medical manuscripts appear to be related to the scriptorium: Urb.gr. 64 and Marc.gr. 288, both of which are very close to the Rubricator.10 Speaking of medical manuscripts, Vat. Gr. 300 is one of the most interesting instances of book decoration within the Straits area, not just because of its content—medical texts from a recent Arabic tradition11—or because its patron is a well-known physician of the Straits’ ellenophone milieu12, but mostly because the second among its four scribes (ff. 211v–230v) copied two quires of the Madrid Skylitzes, namely, the ones without illustrations. The link of this manuscript to Holy Savior is really quite close. It is provided by the writer copying in a very similar manner Mess.gr. 3, more specifically one of its sections (ff. 216–292)—possibly dating from around 1141 (Foti 1989, pp. 59–61)—and another hand (Vat.gr. 300, ff. 262–273), who is responsible for Mess.gr. 69 and Mess.gr. 137, and by one further scribe (ff. 231–261) who worked on a manuscript kept at the Escorial (Scor. T.III.7) that was made by the writer of Mess.gr. 138 (Lucà 1993, pp. 39–41). The Vatican manuscript is decorated with the insertion of a gold-ground pyle at the beginning of the first section (Figure 7)—extremely rare in the Greek-Italian milieu and unique in its quality.

Figure 7.

Vat.gr. 300, f. 11 (Canart and Lucà 2000, p. 86).

2.4. Manuscript Decoration in an Open Cultural Scene: Inspired by Mosaics?

The scroll in the frontispiece of Vat.gr. 300 is characterized by a double, concentric rotation, with diverting tendrils that give the impression of a helix movement. The spiral-like scrolls also characterize Latin manuscripts such as Maio of Bari’s Expositio in Orationem dominicam at the BnF in Paris (Nouv.Acq. 1772), made in Sicily—possibly in Palermo—in 1154–1160. Buchthal attributed the latter’s initials to the Crusader repertoire, though he did acknowledge the influence of textiles and mosaics in the shaping of the decorative formulas implemented across such manuscripts (Buchthal 1956). Indeed, the double twirl with outshooting tendrils can be seen in the scrolls that fill the triumphal arch at the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, themselves a slight development of shoots in the apse of Cefalù (up to 1148), though the curling leaves seem to me to be closer to the Islamicate decorative painting performed in local workshops.

I contend that aside from the proliferation of the so-called Sasanid palmettes in the coeval goldsmith workshop—and here it is worth remembering that the later silver stational cross of Messina Cathedral Treasury has been clarified by Claudia Guastella as being part of San Salvatore’s medieval treasury (Guastella 2005)—the earliest model for such a turning point in the shaping of vegetal shoots could be the lost mosaics of Holy Savior’s church, which later sources tell us covered at least the inner surface of the central dome (Tranchina 2015). As has recently been noted, mosaic decoration across the royal monuments of the early Sicilian Kingdom, and especially decorative fields filling the space between figurative subjects, had in fact become a major area for the hybridization of decorative traditions from both the Byzantine and the Islamic(ate) domains (see Longo 2014). In this respect, there is no doubt that Messina is a lost tessera in the variegated pattern of mural decoration across Northern Sicily—and unfortunately a major one.

3. Addendum

The obvious inclination to attend to the primacy of writing blurs the perception of the actual decorative endeavor, and even to misattributions and misdating. On this topic, it is worth raising the case of San Salvatore’s Prophetologion, Barb. gr. 446, whose provenance from the monastery in Messina is attested by two early hemerological notes: one in the text and the other a later marginale, both of which leave little doubt about the manuscripts’ origin. The first note is found within the title of a pericope to be read on the feast of the Dormition and the Madylion’s translation (15 August), when the manuscript’s users should commemorate a specific event: the consecration of the ‘renowned’ temple of the Savior. The later note, in the margin of f. 202v, reads: 10 March, the thronismos (consecration) of the Savior’s Mandra, and 21 March, that of the Mother-of-God of Kalò.

In the recently published Corpus der italogriechischen dekorierten Handschriften der Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Irmgard Hutter labelled the script in this codex ‘Pre-Reggio style’ (Hutter 2022, p. 746). Sticking to paleographic data, she concluded that the first date, which is embedded in the text’s script, is the only surviving piece of evidence of an alleged monastery pre-history, i.e., of events occurring before 1131/32. According to her the marginale in which the later date appears should be interpreted as evidence of a second—but still early—consecration of the church, corresponding to the well-known date 1132.

Having reviewed some of the evidence surrounding the issues of San Salvatore’s consecration, I would propose that these dates can be interpreted quite differently. Within the typicon manuscript, namely, in the Sinaxary section (ff. 115v–116), a marginale adjoining the date of March 10 declares that the ‘enkainia of our holy temple’ occurred on that date. Our conclusion would be much the same as Hutter’s were it not for the survival of evidence which gives an additional and crucial piece of information: William II and Queen Mother Margaret’s 1168 diploma granting the ‘dowry’ to Archimandrite Onuphrios and to Holy Savior’s church, tempore quo ipsa est nobis presentibus dedicate (http://www.hist-hh.uni-bamberg.de/WilhelmII/pdf/D.W.II.093.pdf (last consultation: 18 January 2023)). Indeed, in 1168, March 10 happened to be a Sunday, i.e., a festive day, which is mandatory for church consecrations. There is therefore little doubt that the marginale in the Barberini prophetologion actually refers to this late consecration, which I argue was prompted by Messina the Latin Archbishopric, after the elevation of the See to the Metropolitan dignity (1166) and during the stay of Margaret and young William in Messina. This is, then, some years before Archimandrite Onuphrios had been compelled to seal his obedience to the Archbishop Robert (m. ante 1166) as it appears in Matr. 9 (f. 134) (Buchthal 1955, p. 338; Enzensberger 1973, p. 1141 n. 1).

There is no need to predate the manuscript. It should instead be listed among the early liturgical books issued by San Salvatore’s scriptorium and made in the context of its ritual use, as the memoirs of the greatest liturgical events at the very beginning of its history still attest.

Funding

This research has been conducted during my PhD course in Art History (27th cycle) at La Sapienza Università di Roma, funded with a public PhD grant.

Acknowledgments

This research is partly related to the project Manuscritos bizantinos iluminados en España: obra, contexto y materialidad-MABILUS (MICINN-PID2020-120067GB-I00) (https://mabilus.com accessed on 5 January 2023), of whose working team I am a member.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Emperor Charles V issued a privilege in 1538, granting the monastery of Bordonaro to the monks in response to their loss; the enforcement letter dates from 1539, as stated in the Regiae visitationes: Palermo, Archivio di Stato (AdS), Regia Conservatoria di Registro, 1310, f. 38v. Monks are said to be already moved to a temporarily domicile in 1542 (see note 2). |

| 2 | Palermo, AdS, Regia Conservatoria di Registro, 1305, f. 28v. |

| 3 | (Buchthal 1955; see Daneu Lattanzi 1965b, pp. 17–20 (with bibliography)). In his 1955 essay on the codices matritenses from Messina, Hugo Buchthal’s drew parallels between this strand of figurative production and the mosaics in Palermo and Monreale, noting that evidence for ‘byzantinizing’ book production is actually few and far between. On San Salvatore in particular he states that “the position is much better […]. A large part dates from the twelfth century, and these include a fair proportion of illuminated volumes of which some at least were certainly written at St. Saviour’s”. |

| 4 | (Pottino 1930, nr. 27; Samek Lodovici 1940–1941, pp. 404–5; Daneu Lattanzi 1965a, pp. 87–89; Daneu Lattanzi 1965b, p. 18), the latter with a dating to the twelfth century. |

| 5 | By Maria Bianca Foti, Santo Lucà, Mario Re and Irmgard Hutter herself; for a synopsis, see (Hutter 2022, vol. 2, p. 749). |

| 6 | (Hutter 2022, vol. 2, p. 750). Hutter also claims (rightly, in my view) that Monk George must be regarded as one of the most prominent figures in the passage from Rossano to Messina. See also (Re 2001, p. 110). |

| 7 | See (Re 2000), who pioneeringly explored San Salvatore’s typicon (Mess. gr. 115) as a source for the early library of the monastery. |

| 8 | Thence comes the Vatican series of Byzantine origin: Vaticani graeci 1005, 2037, 2038, 2039, 2040, 2043, 2044—an almost-complete series missing just two volumes; see (Canart 1978, p. 128; and now Hutter 2022, passim). A provenance from Constantinople has been proposed, dating either to the beginning of the twelfth century (when Bartholomew is supposed to return from a journey to the Capital and Mount Athos) or to the twenties or even thirties: see (Lucà 1983, pp. 143–44; Hutter 2000, pp. 550–51, respectively). |

| 9 | There is also a third volume (Mess.gr. 138), but unfortunately it lacks its beginning and therefore the pyle. |

| 10 | See (Lucà 1993, pp. 84–85; Hutter 2022, pp. 725–27; Furlan 1980, p. 41; Canart and Lucà 2000, pp. 91–92). In fact, the Venice manuscript was copied by the same scribe attending to ff. 1–95 in the Vatican Urbinas. |

| 11 | Abu Jafar ibn-al Gazar’s text, translated as the Ephodia by Constantine of Reggio, excerpts from John’s of Alexandria comment to the sixth book of Hypocratese’s Epidemiai, as well as from Theophylus’s de urinis, the pseudo-galinian Peri Krisimon, recipies by Oribasius, Andromacus the Elder and Archigenis. In the text’s margins many comments by the manuscript’s patron, Philip Xeros, are also present. See (Canart and Lucà 2000, pp. 85–86; Hutter 2022). |

| 12 | Philip Xeros, who handed over the manuscript to his son, Nikolaos. |

References

- Amari, Michele. 1858. Storia dei Musulmani in Sicilia. Firenze: Felice Le Monnier, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro Poletti, Emanuela. 1985–1986. La chiesa ed il monastero del SS. Salvatore dei Greci in Messina (la storia ed un documento inedito). Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia dell’Università di Messina 9–10: 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Boeck, Elena N. 2015. Imagining the Byzantine Past: The Perception of History in the Illustrated Manuscripts of Skylitzes and Manasses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucca, Donatella. 2011. Catalogo dei manoscritti musicali greci del SS. Salvatore di Messina (Biblioteca Regionale Universitaria di Messina). Roma: Comitato nazionale per le celebrazioni del millenario della fondazione dell’Abbazia di S. Nilo a Grottaferrata. [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal, Hugo. 1955. A School of Miniature Painting in Norman Sicily. In Late Classical and Medieval Studies in Honor of Albert Mathias Friend Jr. Edited by Kurt Weitzmann and Serapie Der Neressian. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal, Hugo. 1956. The Beginning of Manuscript Illumination in Norman Sicily. Papers of the British School at Rome 24: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents. 2000. A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments. Edited by John Thomas and Angela Constantinides Hero. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Canart, Paul, and Santo Lucà, eds. 2000. Codici Greci dell’Italia Meridionale. Roma: Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali. [Google Scholar]

- Canart, Paul. 1978. Le livre grec en Italie méridionale sous les régnes normand et souabe: Aspects matériels et sociaux. Scrittura e Civiltà 2: 103–62. [Google Scholar]

- Daneu Lattanzi, Angela. 1965a. I Manoscritti ed Incunaboli Miniati Della Sicilia. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Daneu Lattanzi, Angela. 1965b. Lineamenti di Storia della Miniatura in Sicilia. Firenze: Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Enzensberger, Horst. 1973. Der Ordo Sancti Basilii: Eine monastische gliederung der Römischen Kirche (12.–16. Jahrhundert). In La Chiesa Greca in Italia dall’VIII al XVI Secolo, Atti del Convegno Storico Interecclesiale (Bari, 30 Aprile–4 Maggio 1969). Padova: Edizione Antenore, vol. 3, pp. 1139–51. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, Maria Bianca. 1989. Il Monastero del S.mo Salvatore in Lingua Phari. Proposte Scrittorie e Coscienza Culturale. Messina. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, Italo. 1980. Codici Greci Illustrati Della Biblioteca Marciana. Catalogo Della Mostra Tenuta a Grottaferrata Nel 2000. Milano: Edizioni Stendhal. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, Giovanni. 1910. Recensione a (Lo Parco 1909). Scolario-Saba Bibliofilo, La Critica 8: 304–7. [Google Scholar]

- Guastella, Claudia. 2005. Aspetti della cultura artistica nel Valdemone in età normanna e sveva: Note e riflessioni. In La Valle d’Agrò. Un Territorio una Storia un Destino. Edited by Clara Biondi. Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali, pp. 225–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Otto. 1886. Die Übersetzungsliteratur Unteritaliens in der normannisch-staufischen Epoche. Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen 3: 161–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, Irmgard. 1980. Oxford marginalien. Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 29: 331–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, Irmgard. 1982. Corpus der Byzantinischen Miniaturenhandschriften, 3.1. Oxford. Bodleian Library III. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, Irmgard. 2000. Le copiste du Métaphraste. On a center for manuscript production in eleventh-century Constantinople. In I Manoscritti Greci tra Riflessione e Dibattito, atti del V Colloquio Internazionale di Paleografia Greca (Cremona, 4–10 Ottobre 1998). Edited by Giancarlo Prato. Firenze: Edizione Gonnelli, pp. 535–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, Irmgard. 2022. Corpus der Italogriechischen Dekorierten Handschriften der Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Corpus der byzantinischen Miniaturenhandschriften, 6. Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Image and Scripture. Greek Presence in Messina from the Middle Ages to Modernity. 2013. Palermo: Fondazione Federico II.

- Jacob, André. 1980. Un euchologe du Saint-Sauveur «in Lingua Phari» de Messine. Le Bodleianus Auct. E. 5. 13. Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 50: 283–364. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Parco, Francesco. 1909. Scolario-Saba bibliofilo italiota vissuto tra l’XI e il XII secolo e la biblioteca del Monastero basiliano del SS. Salvatore di Bordonaro, presso Messina. Nuovo contributo alla storia civile e religiosa dell’epoca normanna e alla conoscenza dei primordii del Risorgimento dell’antichità ellenica. Napoli: Tipografia della Regia Università. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, Ruggero. 2014. Opus sectile a Palerno nel secolo XII. Sinergie e mutuazioni nei cantieri di Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio e della Cappella Palatina. In La Sicilia e Bisanzio nei Secoli XI e XII, Atti Delle X Giornate di Studio della Associazione Italiana di Studi Bizantini (Palermo, 27–28 Maggio 2011). Byzantino-sicula, 6. Edited by Renata Lavagnini and Cristina Rognoni. Palermo: Istituto siciliano di studi bizantini e neoellenici, pp. 299–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lucà, Santo. 1983. Osservazioni codicologiche e paleografiche sul Vaticano Ottoboniano greco 86. Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottaferrata 37: 102–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lucà, Santo. 1993. I Normanni e la rinascita del secolo XII. Archivio storico per la Calabria e la lucania 60: 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lucà, Santo. 2016. Sul Teodoro Studita Crypt. Gr. 850. In Studi bizantini in onore di Maria Dora Spadaro. Edited by Tiziana Creazzo. Acireale and Roma: Bonanno editore, pp. 245–76. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Francesca. 2014. Note sull’ornamentazione iniziale dello Scilitze di Madrid. Nea Rhome 11: 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Matranga, Filippo. 1887. Il monastero del SS. Salvatore dei Greci dell’Acroterio di Messina e San Luca primo Archimandrita Autore del Cartofilacio, o sia della raccolta dei Codici greci di quell Monastero. Messina: Regia Accademia Peloritana—Tipografia D’Amico. [Google Scholar]

- Mercati, Giovanni. 1935. Per la storia dei manoscritti greci di Genova, di varie badie basiliane d’Italia e di Patmo. Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Parpulov, Georgi R. 2017. Psalters and Books of Hours (Horologia). In A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts. Edited by Vasiliki Tsamakda. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 300–9. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson Ševčenko, Nancy. 1984. A Menologium in Messina. In Tenth Annual Byzantine Studies Conference. Abstract of Papers (The University of Cincinnati, 1–4 November 1984). Cincinnati: vol. 10, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson Ševčenko, Nancy. 1990. Illustrated Manuscripts of the Metaphrastian Menologion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Perria, Lidia. 1974. Alcuni lezionari greci della «Scuola di Reggio nella Biblioteca Vaticana». Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottaferrata 28: 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pottino, Filippo. 1930. Codici Miniate Siculo-Bizantini in Messina. Palermo: Scuola tip. “Boccone del povero”. [Google Scholar]

- Re, Mario. 2000. Il typikon del S. Salvatore de Lingua Phari come fonte per la storia della biblioteca del monastero. In Miscellanea di Scritti in Memoria di Bruno Lavagnini. Byzantino-Sicula, 3. Palermo: Istituto di Studi bizantini e neoellenici, pp. 249–78. [Google Scholar]

- Re, Mario. 2001. I manoscritti in Stile di Reggio vent’anni dopo. In O Ιταλιώτης Ελληνισμός από τον Ζ στον ΙΒ αιώνα. Μνήμη Νίκου Παναγιοτάκη. L’Ellenismo italiota dal VII al XII secolo, alla memoria di Nikos Panagiotis. Edited by Nikolaos Oikonomides. Athens: Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερενών. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriquez, Maria Teresa. 2013. Greek culture, books and libraries. In Image and Scripture. Greek Presence in Messina from the Middle Ages to Modernity. Palermo: Fondazione Federico II, pp. 217–50. [Google Scholar]

- Samek Lodovici, Sergio. 1940–1941. Codici miniati bizantini nella R. Biblioteca Universitaria di Messina. Accademie e Biblioteche d’Italia 15: 403–8. [Google Scholar]

- Scinà, Domenico. 1824. Prospetto della storia letteraria di Sicilia nel secolo decimottavo. Palermo: Officio Tipografico Lo Bianco. [Google Scholar]

- Tranchina, Antonino. 2015. “Et era una delle segnalate memorie di Sicilia”: Ipotesi sull’antico monastero del Salvatore presso Messina. In In corso d’opera. Ricerche dei dottorandi in Storia dell’Arte della Sapienza. Edited by Michele Nicolaci, Matteo Piccioni and Lorenzo Riccardi. Roma: Campisano, pp. 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tranchina, Antonino. 2016. The Depiction of the Lingua Phari and the Church of Holy Savior in the Brukenthal collection’s ‘Crucifixion’ by Antonello da Messina. Brvkenthal Acta Mvsei 11: 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Tsamakda, Vasiliki, ed. 2017. A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Tsamakda, Vasiliki. 2012. The Illustrated Chronicles of Ioannes Skylitzes in Madrid. Leiden: Alexandros Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Falkenhausen, Vera. 1994. L’Archimandritato del S. Salvatore in lingua phari di Messina e il monachesimo italo-greco nel regno normanno-svevo (secoli XI–XIII). In Messina. Il Ritorno Della Memoria. Catalogo Della Mostra (Messina, Palazzo Zanca, 1 Marzo–28 Aprile 1994). Palermo: Novecento, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1935. Die byzantinische Buchmalerei des 9. und 10. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl Carr, Annemarie. 1987. Byzantine Illumination 1150–1250: The Study of a Provincial Tradition. Chicago: The University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl Carr, Annemarie. 1989. Illuminated Manuscripts in Byzantium: A Note on the Late Twelfth Century. Gesta 28: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).