Abstract

Living and working for a month at the Sanskriti Foundation in Delhi, the artist’s life was watched and observed by a group of resident monkeys. This paper is based on notes begun during that studio residency and represents the critical reflections emerging alongside the hands-on sculptural practice. It is illustrated with close-up photographs of the artist’s sculpture that asks how encounters with fabled animals in densely populated 21st century urban areas can alter our understanding of the gaze as an inter-species gaze. The sculpture and paper begin to ask broader questions, including how can sculpture provide a different, and perhaps more tacit and empathetic, encounter with the other to enable a physical, mental or spiritual experience of cultural entanglement between the various onlookers? In how far is modelling the other’s gaze a form of embodiment and mimicry? Do the fast-changing camera angles and soundtracks of natural history programmes hinder an empathic inter-species encounter? Or, does the slow animation of the artist’s sculpted surface heighten a sense of being alongside equally curious, cunning and adaptable others such as crows, foxes and monkeys?

Introduction

You look at me looking at you looking at me is a reflection on a body of figurative hand-modelled sculptures of foxes, crows, and monkeys that are living and scavenging in many large urban sprawls across the world, such as the example of Delhi discussed later. The work is situated within the broader discourse of inter-species relationships and seeks to question the superiority claim of the human animal (human exceptionalism). Drawing on some seminal texts, including Why Look at Animals? (Berger 2009), The Serpent Ritual (Warburg and Mainland 1939), How to be Animal (Challenger 2022), Saving Beauty (Han 2017), L’animal que donc je suis (Derrida 2006) and The Natural Contract (Serres 1995), this paper argues that in contrast to the pin sharp image created by advanced cinematography, these hand-modelled foxes, crows, and monkeys enable real and emotional encounters with the other. Concluding that we, the upright walking animal, need to experience empathic encounters with other animals to grasp the urgency of the situation that arises from living on one shared earth, this paper states: we need to drastically change our value systems, including ethics. (please see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12).

This paper articulates the associative and non-linear thinking triggered by the making process in the studio. It is based on notes started during the studio residency in Delhi and recounts the critical reflections that emerged alongside the hands-on sculptural practice. It is illustrated with close-up photographs of the sculptures and asks how encounters with fabled animals in densely populated 21st century urban areas can alter our understanding of the gaze as an inter-species gaze.

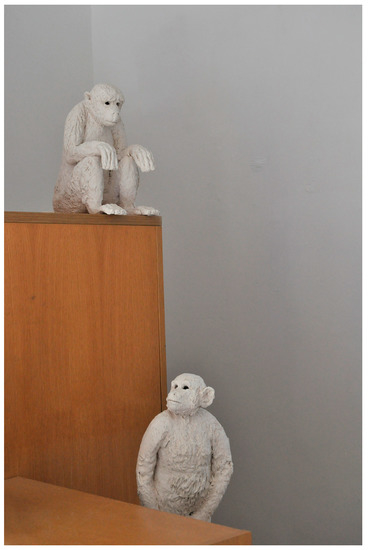

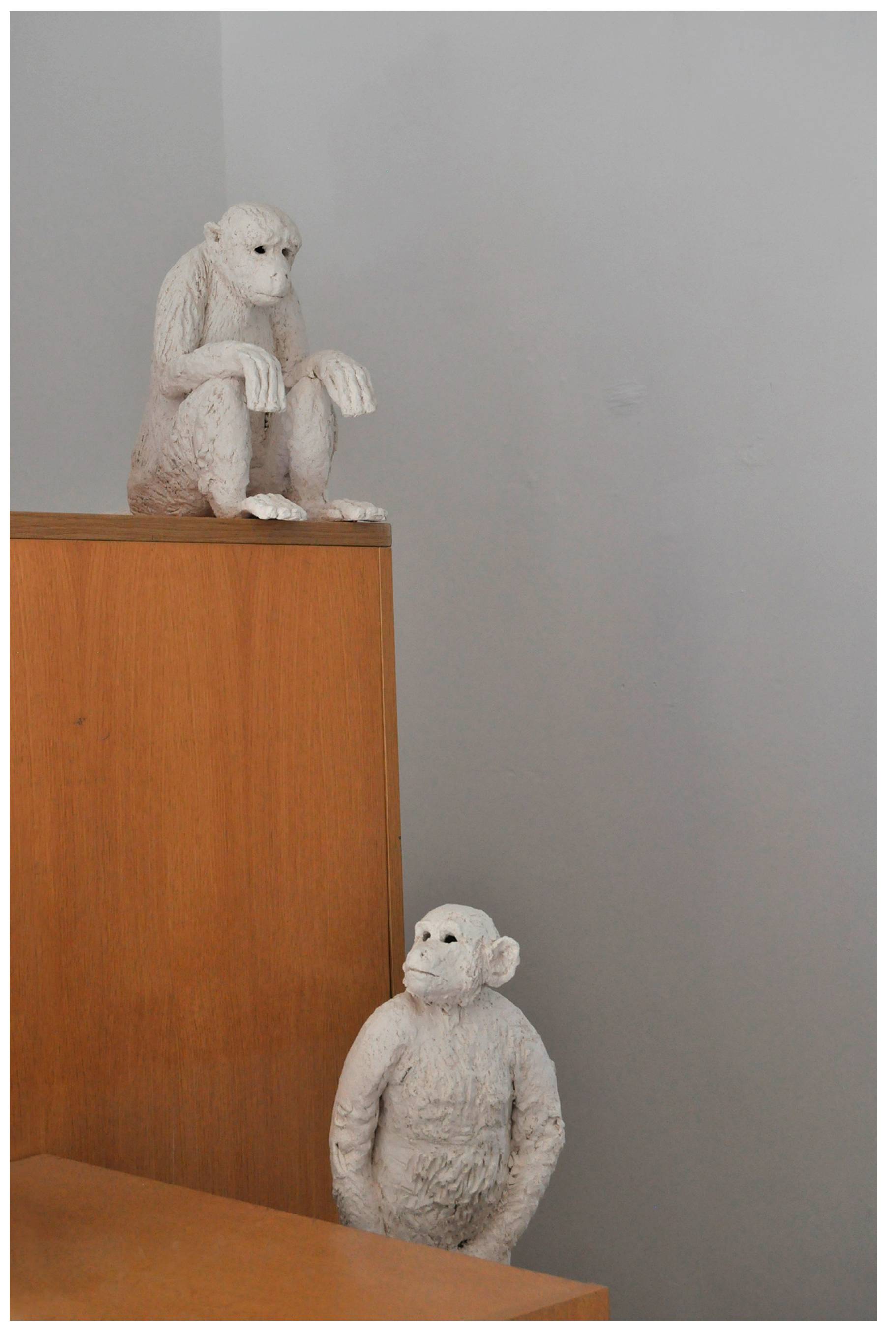

Figure 1.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm. All photos by artist unless otherwise credited.

Figure 1.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm. All photos by artist unless otherwise credited.

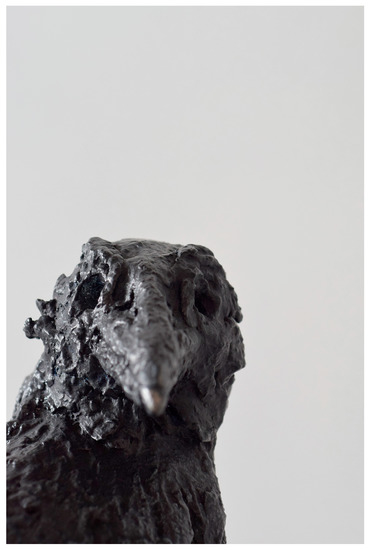

Figure 2.

Crow (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 25 × 45 × 19 cm.

Figure 2.

Crow (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 25 × 45 × 19 cm.

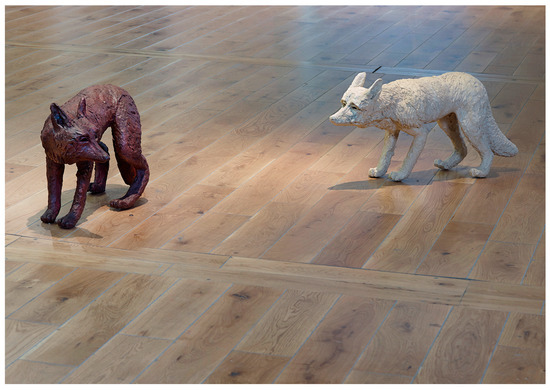

Figure 3.

Foxes and crows (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 3.

Foxes and crows (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 4.

Crow (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 25 × 45 × 19 cm.

Figure 4.

Crow (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 25 × 45 × 19 cm.

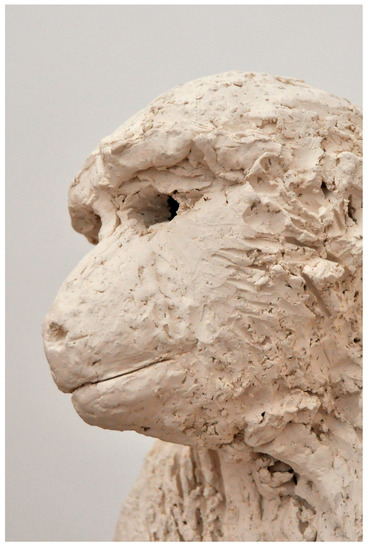

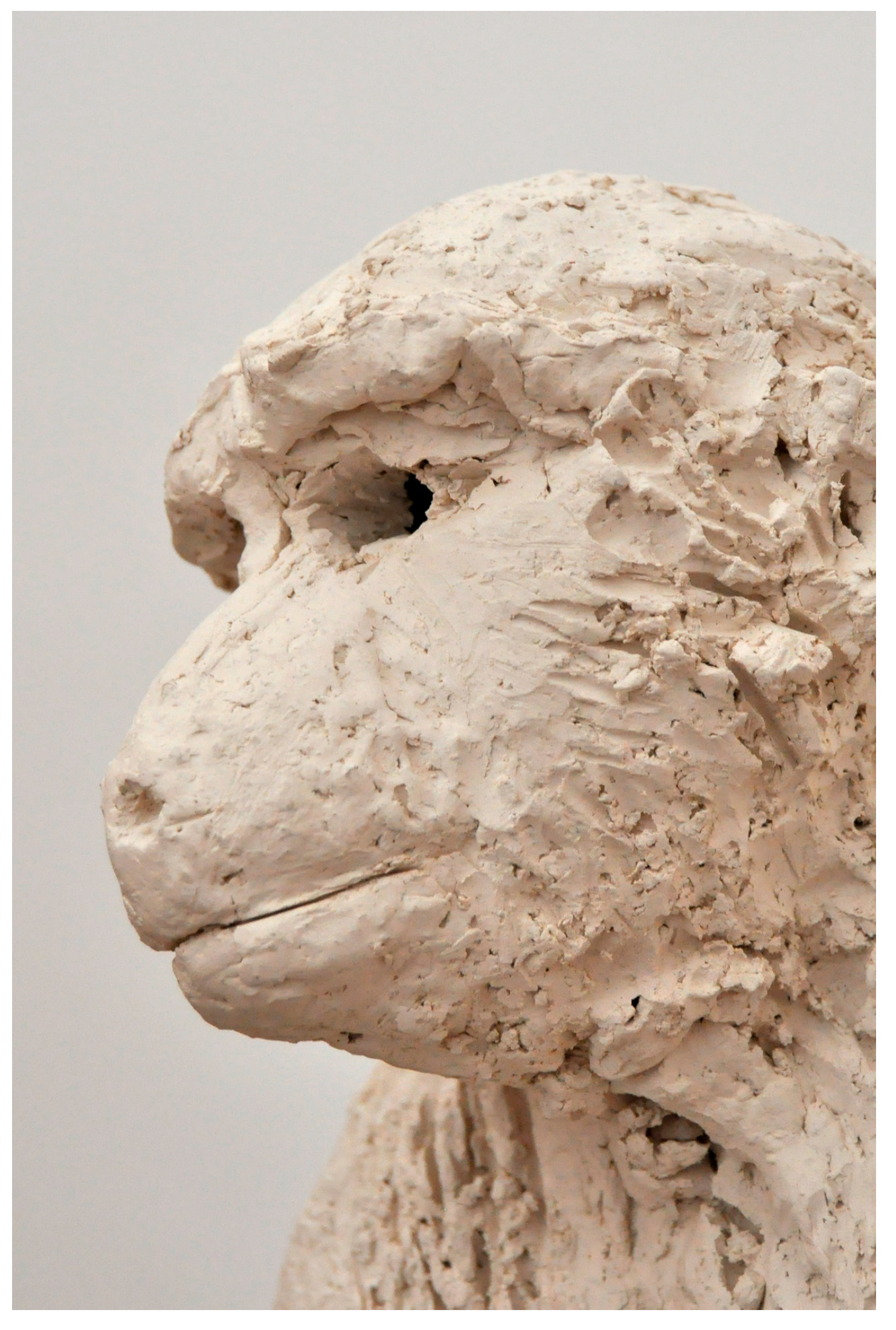

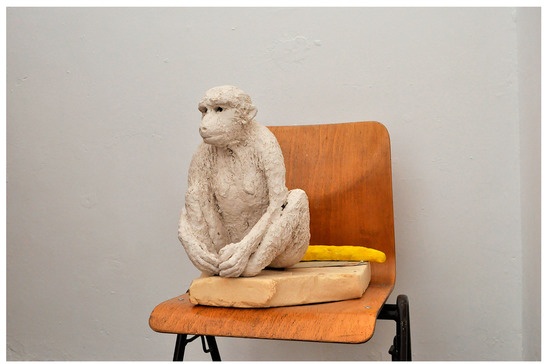

Figure 5.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

Figure 5.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

Figure 6.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

Figure 6.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

“She wonders if she can look the pig in the eye. The neighbour has a heart valve from a pig. The pig’s eye is very similar to the human eye, and so is the heart. The pig is afraid when it is killed. It feels the danger and screams.”(Jurack 2022)

Brown eyes, pale blue eyes, orange eyes, green eyes, black eyes. Can you look into the pale blue eyes of a pig? Her eyes are so like our human eyes. Look into her eyes. Who do you see? The black eyes of a cow show the reflection of your gaze. The blue eyes of a pig, framed by pale eyelashes, look at us. I do not know if I could kill a pig after I looked her in the eyes, since she returned my gaze. I do not know if we recognized each other in that moment as equal entities. In what way did we recognize each other? Did we?

I looked into your eyes, and I saw you looking at me looking at you.

At night, a fox sits on the empty station car park, uncertain, ready to run, observing every move from a middle distance. Crows and magpies have taken up clearly defined territories in most tall trees of sub/urban parks and overgrown wastelands. Murders of crows scuttle the ground, roadside grass verges, park lawns and playing fields. The fast-clapping rack rack rack sound of magpies perching on aerials of suburban houses cuts through the air like the Martins horns of emergency services. During the early hours of most winter mornings, I see a common kestrel on the nearby school playing field, feeding on worms and other larger insects.

The living places of foxes, crows, kestrels, monkeys, black kites and bats intersect and overlap with ours. Meeting them in noisy and busy megacities is akin to receiving messages from a different world, one we have lost or at least forgotten, a world where experience accumulated by cultures that worked the land and of people who worked and lived in the weather (Serres 1995).

At dawn or dusk, the gaze of the urban fox becomes a messenger, a reminder and representative of other living species in our neat human-centered and commodified lives. Who is adapting to whom and where? How deep is our entanglement with other animals? Can we shift our value system in such a way that we empathetically recognize that all creatures, big and small, have a voice and a right to be on this Earth, with its finite resources of soil, fields, forests, water, weather, shade, wind, sunshine and darkness? How and when do we recognize (again) that the Earth existed without our unimaginable ancestors, could well exist today without us, will exist without any of our descendants, whereas we cannot exist without it (Serres 1995)?

Carved and modelled forms that resemble animals can be found across all cultures and at all times. Small ceramic monkeys, carved hares, seals, whales, doves, snakes, frogs, lions and domesticated and non-domesticated animals were created by fishermen, hunters, peasants, unnamed artisans and known artists. Whilst acknowledging that Warburg belongs to a generation of scholars whose anthropological plundering was conducted from a completely Euro-centric perspective, his late work observes that it was the scarcity of water that led people to the art of prayer. In ceremonies, worship, and ritual, animal representations on everyday objects such as water vessels are understood as hieroglyphs, not just a picture/object to look at but something to be read—an intermediary stage between image and sign, between realistic representation and script (Warburg and Mainland 1939). Warburg observes that the carved, modelled or drawn animal’s effectiveness as intermediary is not depending on a particularly realistic rendering, an observation shared also by Berger (2009) and Han (2017).

The stand-in role of the crafted animal as a kind of soul, spirit, totem or sign can also be seen in the carved and modelled sculptures of Ewald Mataré (1887–1965), Stefan Balkenhol (1957), Laura Ford (1961) and Yannis Kastritsis (1960). These artists use free-hand carving and modelling based on observations of real animals, similar to my experience in Delhi and in the UK. With my hands, I made eighteen Macaque monkeys, twenty crows, and twelve foxes to question the representation of otherness through the medium of wet clay, petrified to stoneware. My monkeys, crows, and foxes observe, gaze, daze, sit, walk, run, stand still, perch, sniff, bicker and watch. These animals exist within wider cultural contexts and current debates around environmental injustices.

Snake, monkey, crow, fox, cow, elephant, dove, lamb, lion, tortoise, hare and many other animals have been or are still living representations of some sort of ‘divine’ power. The animals themselves or images of them are stand-ins and intermediators between ‘divine’ and ‘eternal’ entities (weather, water, cosmos) and the corporeal human. The animal and its stand-in has a special status which is revered or celebrated through rituals, song, oral history and literature, imbued with meaning, attributed with ‘human traits’ such as cunningness, wit, grace, intelligence, strength, power and prophetic abilities; they are ‘carriers’ and signifiers of meaning.

I use fat earth (clay) to make sculpture. I am thinking about permeable layers of sedimentation and meaning, tilting in various directions, overlapping, snapping and blurring. My hand-modelled animals are more like schematically drawn illustrations of geological strata and less like the smooth surface of Lidar-informed 3D visualizations.

On an ur-layer, their message is loud and clear: we are not alone. There are other animals, different but also like us, who live on the earth, swim in the water, and fly overhead. I imagine the relief of prehistoric men and women, realizing they were not alone. They observed others who gave birth, had suckling offspring needing care and protection or were infirm, injured, old and dying. We have scientific evidence that the big round eyes of a baby monkey or a puppy trigger chemical protection signals in our brains and “what we have in common with all mammals are what is called C tactile afferents. These are neurons found in hairy skin and the spinal cord” (Challenger 2022). These transmit touching, stroking, licking from mother to baby and radically effect the physiology of the babies (Challenger 2022). At the start of life is empathy: feed, protect, nurture and keep warm.

On the next layer is hunger and the need to eat. Keeping alive means eating and feeding and the organization of food. At this point, animals go off in different directions: herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores share the same places. Could it be, that under stress-free conditions, an equilibrium of sorts was possible, that smaller predators were kept in check by bigger predators? A kestrel eats a mouse, a lion the weakest antelopes, and ice bears the plentiful herring as crows clean up the left-over of the kills. A member of one species is attacked and killed by a bigger, faster, smarter species but never in excess, never more than the essential within relatively stress-free conditions. Then, we humans turn up and kill the largest mammals towards extinction or eliminate them from vast areas of land.

If we were still hunting with bow and arrow and had no fridge freezers or giant global food producing conglomerates, would we be occasional rather than habitual and excessive carnivores?

Could I kill the pig after her pale blue eyes meet mine, looking at me and looking at her? How hungry would I need to be to kill?

Within large industrialized livestock farming, animals are not given names, but numbers and barcodes on digital registers that chart computerized efficiency of time, calories or cull co-ordinates; 21st century corporate capitalism has completely ruptured what previously mediated between humans and nature (Berger 2009). Whilst animals were with humans at the centre of the world, they are now treated as raw material and those “required for food are processed like manufacturing commodities” (Berger 2009). Serres argues that the greatest event in the 20th century is the disappearance of agricultural activity at the helm of human life in general and of individual cultures (Serres 1995).

Do we keep switching the empathy lever off so we can unflinchingly pretend and ascertain an understanding of ourselves as superior species? Have we not noticed that the switched-off position prevents us from connecting to the next layer of interdependence, namely the layer of meaning making?

This making sense is based on observation of behavior of living phenomena, such as tides, volcanos, mountains, rocks, animals, weather, droughts, floods, illness, disaster and death. Describing (language, image, ritual) these observations in relation to one’s surrounding, interpreting, and sharing is meaning-making. The world of the living, including compressed crustations in rocks, microbes, and viruses, is wondrous and filled with the essential otherness of beings. Seeing in the empathetic sense means seeing differently, namely, experiencing (Han 2017), and this kind of seeing requires vulnerability or humbleness, a stepping down from the superiority angle.

Modelling wet clay into shapes is a becoming or seeing of the other and is a form of exposure to letting it (the experience) happen. As mentioned, foxes, crows, and monkeys are three of the most ubiquitous and adaptable non-domesticated animals. They are modelled, described, and expressed in relationship and proximity to me (the upright standing one) and to each other. Metaphors of cunning foxes, cheeky monkeys, and intelligent crows explicitly connect to thinking in the round, acknowledging that animals are born, sentient, and mortal, both like and unlike us (Berger 2009). The representations are stand-ins, monuments to these cunning, cheeky, and intelligent animals, their surfaces inviting and triggering empathetic encounters.

From the 19th century onwards, attributing figurative narratives or ‘magic power’ to observable phenomena and animals was dismissed as ‘anthropomorphic’, scientifically incorrect, and relegated into the realm of children’s literature, pagan cosmologies, mythologies and remote populations, the domain of art historians, ethnographers, anthropologists and writers such as Roald Dahl, Edgar Allan Poe, and Ted Hughes.

Current micro-biological research (Sheldrake 2021) into communication networks of living microbes, lichen, fungi and trees confirms the aliveness passed down from generations to generation in metaphors, tales, rituals, beliefs and mythologies. From the perspective of the 21st century and supported by evidence-based natural science, we have a second chance to overcome our internalized outdated exceptionalism, as well as an invitation to drastically shift our perception of the living world again and with it our value systems and ethics: “All forms of life are exceptional” (Challenger 2022). The structure of justice ought to build on generosity, dignity, and compassion in recognition that all life (living creatures big and small) is precious and worthy of respect—living with fellow creatures rather than above and beyond them.

Carl Ewald’s almost forgotten Mother Nature Tells (Mutter Natur erzählt) (Ewald 1922) reads today as an attempt to combine natural science with ideas of personhood. In his nature tales, trees, tides, fish, cosmos, and bacteria talk about their suffering, mischief, and perspective on being, sharing and interacting with humans and other living creatures. Indeed, Ewald’s wider work reminds us that we cannot separate fighting climate change from fighting social injustices. The value of protecting and feeding one’s offspring is shared amongst nearly all living creatures. Our stories of and with animals in mythologies, fables, children’s books and animations talk about the abilities of shifting our perspectives and recognising the feelings of other living beings, thus making generosity a new category of behaviour (Challenger 2022) shared with our closest relatives, the apes.

Animal science has caught up with the tacit knowledge of the early hunters and gatherers. Thanks to wired-up monitors, micro/macro lenses, and audio recording advancements, we now scientifically know that animals, including fish and octopus, are sentient beings after all, communicating within their species. We also know from the molecular biology perspective that our human-animal DNAs are more similar than not. However, do we know in which unlicensed laboratories DNA from human and pig stem cells is being swapped and changed?

During a studio residency in Delhi, I lived very close to Macaque monkeys. Bored, curious, cheeky, hungry and playfully sociable, they eyed up my studio, dinner table, rubbish bins and both the indoor and outdoor kitchens. I could not stop watching them watching me. I never felt as observed as under their gaze. Ape Theater (Berger 2009) describes this uneasy relationship between resemblance and closeness experienced by those visiting an ape enclosure in any European zoo. This uneasy relationship is triggered by my sculptures.

Within Hinduism, the Macaque monkey is regarded as the living representation of the god Hanuman and taboos are in place making it a criminal offence to kill or harm one of the estimated 40,000+ co-habitants of Delhi. In the Hindu language film Eeb Allay Ooo! (Vats 2019) the relationship between Macaque monkeys and workers in the government district of Delhi moves from comedy to tragedy when the migrant monkey guard is lynched by his colleagues for harming a monkey. As living representation of Hanuman, interdependence, empathy, and the rights of the animal are culturally defined and whilst the expansion of the Delhi conurbation is relentless, encroaching on all sites on the natural habitat of many living creatures, the special statues of the monkey is protected by religious taboos.

A lengthy court case between 2015–2018 decided the fate of Robby, one of the last ‘retired’ circus apes in Germany. The initial court order to send the 45/47-year-old Robby into an ape rehabilitation centre was overruled on the grounds that at the advanced age of the ape, and the 40-year attachment to his human owner, remaining with the human he knew was deemed more appropriate for Robby’s wellbeing. Just as Kafka fictionalized 100 years prior in A Report to an Academy (Kafka 1917), a return to nature, or the almost-nature of a rehabilitation center in the company of other apes, was impossible.

Robby, the retired circus ape, and the monkeys in Delhi are just two examples, highlighting the close link between empathy and rights, an empathy that is entangled with close interdependence linked to the layer of meaning making, rather than consumption. It is easy to imagine that the German judge looked into Robby’s old eyes and saw himself as an old man. After all, molecular biology confirms that we share 99% of DNA with the apes. Anybody who has looked at an ape returning their gaze can sense that the ape’s functional gestures are familiar, but their expressive ones also resonate—gestures which denote surprise, amusement, tenderness, irritation, pleasure, indifference, desire and fear (Berger 2009).

Figure 7.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

Figure 7.

Monkey Business (2018), FILET, London. Ceramic, 50 × 36 × 25 cm.

Figure 8.

Foxes and crows (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 8.

Foxes and crows (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

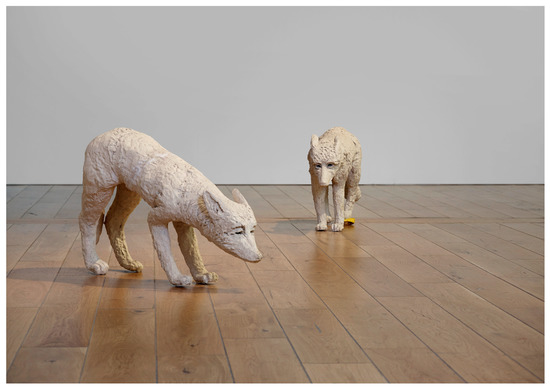

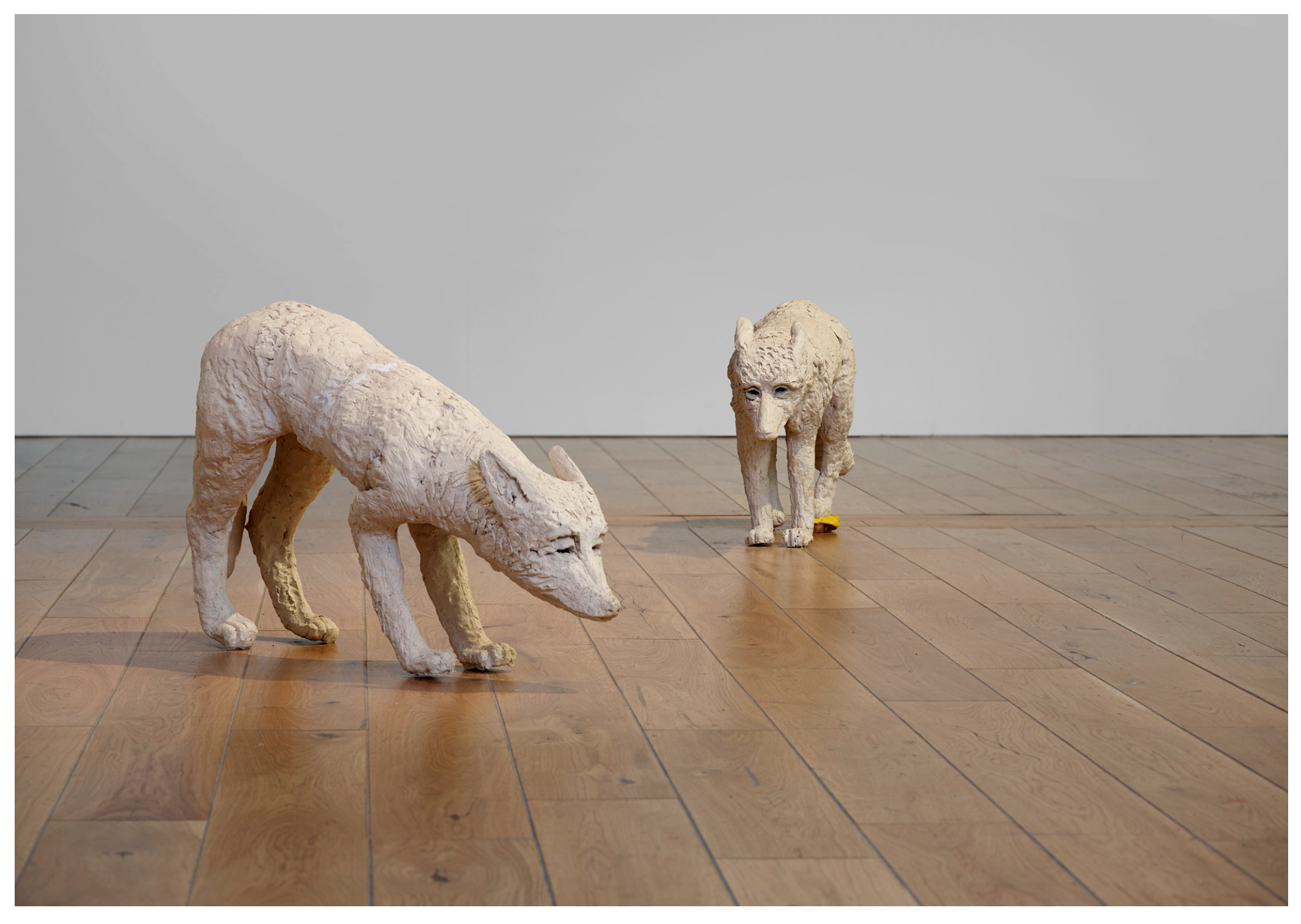

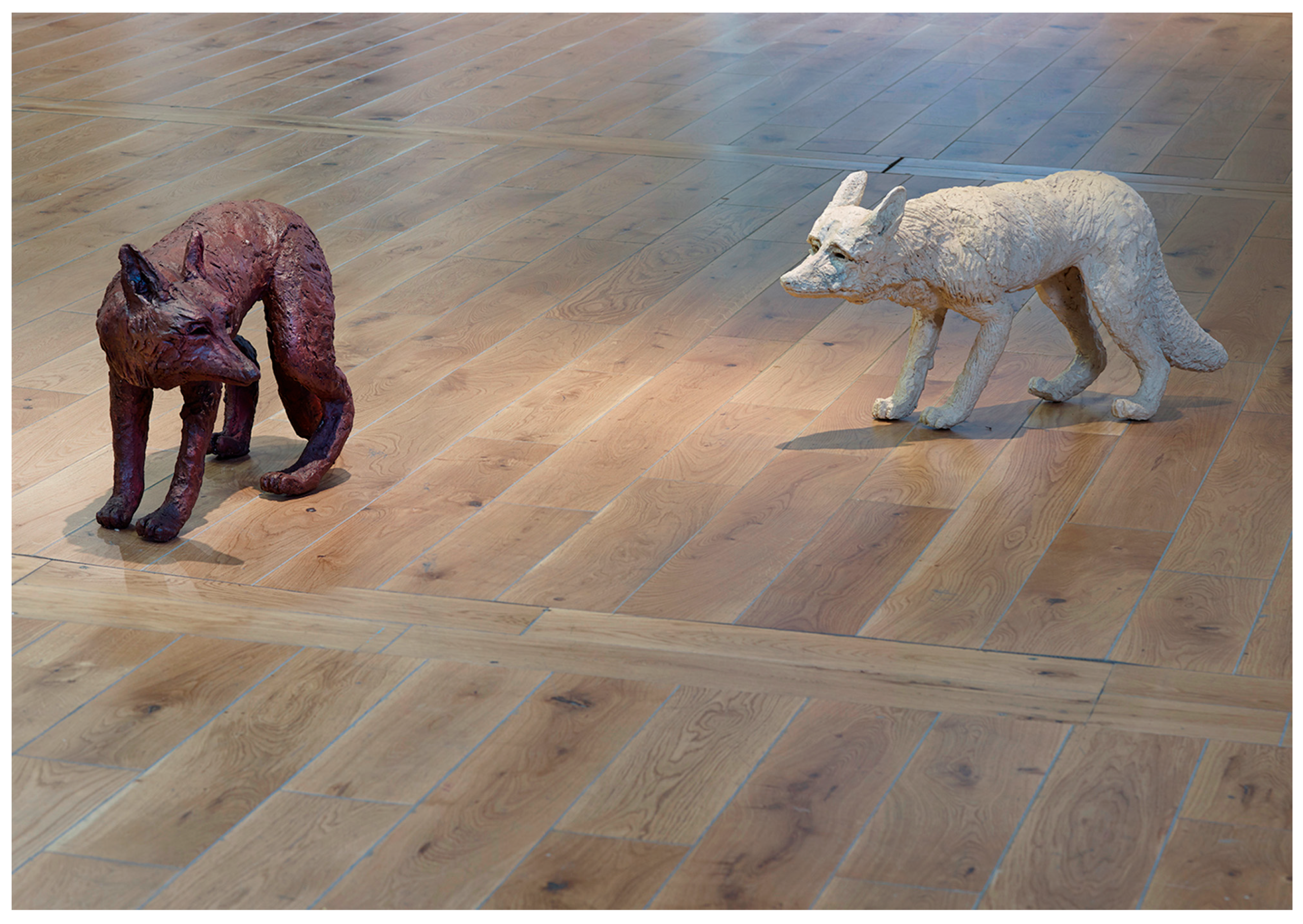

Figure 9.

Foxes (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 9.

Foxes (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 10.

Vixen (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 48 × 60 × 25 cm.

Figure 10.

Vixen (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 48 × 60 × 25 cm.

Figure 11.

Foxes (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 11.

Foxes (2022), Fieldnotes, HOME, Manchester. Ceramic, various sizes. Photograph by Michael Pollard.

Figure 12.

Sitting Cub (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 40 × 23 × 38 cm.

Figure 12.

Sitting Cub (2020), Alternator Studio. Ceramic, 40 × 23 × 38 cm.

Sensual encounters such as the return of a gaze, the looking into the eye of the pig, and the slow observational looking enabled by the sculptural rendering of the monkeys, foxes, and crows are triggers for empathetic encounters and the starting point for changing notions of superiority. These very encounters shake you up (or perhaps bring you to tears) and momentarily force you to see the disarming truth that the other has the same right to be here, to have space to live and to be living a fulfilling life.

What is crucial in the tactile encounter is the vis-à-vis. The encounter is a sensual bodily tactile one, not a video link, super HDI or in VR/AR form voiced over with infotainment material combined with melodic or dramatic soundtracks. These admittedly seductive digital images form a smooth space of the same, not permitting anything alien, any alterity to enter (Han 2017). You have to be standing at the pig pen, look over the barrier, see and touch the wet snout, the pale blue eyes and the blonde eyelashes, smell her scent, stay, listen to her breathing, watching her diaphragm move up and down in her sleep, watch her tend to her offspring or wallow in the mud and then ask yourself why we do not debate the ethics of transplanting pig heart valves into humans, drafting her skin onto burns victims and now also meddling with her DNA, to make her more human-like, to allow for the skin drafts and organ transplants to become successful?

Why do we not talk about the ethics of such undertakings in prime-time politics or evening TV debate shows, rather than in literature, art or often obscure and hidden ethics committees? Would you donate your heart valve to a pig in need? Would you allow meddling with your DNA, so you become more pig-like (genetically speaking), making the valve from your heart more compatible to hers?

Cameron Joshua Kelsey, the fictional boy in Pig-Heart Boy (Blackman 1997) asks himself and the scientists and medics in white coats these questions. He insists on seeing the pig, which ‘provides’ him with her heart. He is in fact the ‘guinea pig’ in this story of trans-genetics and visits the unlicensed bio-medical laboratories in which interspecies pig-human transplantations are trialled. Here, between the covers of a novel for young readers, the fictional expert lets his guard down and reveals that the only reasons they use pigs is that they are not seen as endangered and are already bred for food. The expert adds that no funding organization would support the use of other species such as monkeys or baboons that are closely related to humans. Cameron succumbs and receives not one but two pig hearts. On borrowed time, like the non-fictional American patient David Bennett, both die weeks after the xenotransplantation.

It seems as if shamanism, the hybrid creatures of ancient mythology, pantheisms, and animal-human hybrid gods and goddesses have left the realm of imagination and have become micro-biological and nano-technology engineering reality. We are technologically at a point where we do not anthropomorphize the living world with poetic language, vivid imaginations, and shamanism but where we quite literally insert human genetic material into pig’s DNA, creating for real animal-human hybrids.

Does the pig have rights of her own? I do not only mean rights in relation to minimum amount of space, fresh air or access to roaming but in terms of her right to be treated like a person? What would this mean for her integrity, ancestry, and long history of cultural interdependence to ‘humans’ that include at least 80 years of mass abuse in industrialized ‘farming’ practices? If the pig had legal personhood, then violence against her would be a prosecutable crime. Mass-imprisonment would be made illegal and perhaps you could only eat her when she had died of old age. She would most certainly gain the right to dig in the mud with her snout and eat the roots and rhizomes of brambles and bracken, like her wilder relatives do. She would be protected for her own worth and our actions would be guided by newly defined cultural taboos.

Instead, the mystical, spiritual, and sensual relationship we may have once had with her and other living beings has been replaced by a relationship that is either guided by consumption or an engineering mindset. It is a mindset that takes the whole apart, modifies and re-assembles it, supported by powerful technology and infrastructure in sealed buildings. How do we switch the empathy lever back on and allow ourselves to become the sentient beings capable of creating a cultural shift towards a more equal and more tender sharing of the one living earth and her living beings?

In 2017 the Whanganui River in New Zealand became the first river in the world to be granted legal personhood status. In Maori culture, tupuna or ancestors live on in the natural world and it is the community’s duty to protect both the landscape they inherited and those who came before them. Humans and water are especially believed to be intertwined—a traditional saying is, “I am the river, the river is me.” Having the river recognized as a legal person means harming it is the same as harming the tribe. If there is any kind of abuse or threat to its waters, such as pollution or unauthorized activities, the river can sue. It also means it can own property, enter contracts, and be sued itself (Evans 2020).

Environmental personhood could be one way forward in the 21st century, combining the language of law with our tacit knowledge (if we still retrieve it) to protect nature and her living creatures, as American law professor Christopher D. Stone argues in Should Trees Have Standing? (Stone 1972).

As I shape the wet clay into the legs, tail, body, head, ears and eyes of a fox, I create an artefact that endeavours to come alive in the eye of the beholder. The physicality of the sculpture is paramount in this process since it allows for slow sentient encounters with the other as equal. The sculptures of crows, foxes, and monkeys are modelled as if viewed from a distance that mimics a kind of respectful, tolerable, and safe distance between species. I would argue that these sculptural representations enable the respectful distance that Warburg and Mainland (1939) and Berger (2009) write about. An awe that expands the longer we remain in the same space and time with the other. Looking at being looked at. Recognized? Perhaps. Who knows?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Further documentation available at: www.brigittejurack.de (accessed on 22 January 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berger, John. 2009. Why Look at Animals. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, Malorie. 1997. Pig-Heart Boy. London: Corgi. [Google Scholar]

- Challenger, Melanie. 2022. How to Be Animal: A New History of What It Means to Be Human. Edinburgh: Canongate. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 2006. L’animal que donc je suis. Éditions Galilée. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Kate. 2020. The New Zealand River that Became a Legal Person. BBC [online]. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20200319-the-new-zealand-river-that-became-a-legal-person# (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Ewald, Carl. 1922. Mother Nature Tells (Mutter Natur erzählt). Paderborn: Salzwasser Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2017. Saving Beauty. Oxford and Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Jurack, Brigitte. 2022. Die Vermesserin. Limited Edition 20 Artist’s Publication. Grisons: Alps Art Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka, Franz. 1917. A Report for an Academy. Edited by Nathan Glatzer. The Complete Stories (1983). New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Serres, Michel. 1995. The Natural Contract (Studies in Literature and Science). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake, Merlin. 2021. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures. London: Bodley Head. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Christopher. 1972. Should Trees Have Standing?: Law, Morality, and the Environment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vats, Prateek. 2019. Eeb Allay Ooo! Delhi: NAMA Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby, and W. F. Mainland. 1939. A Lecture on Serpent Ritual. Journal of the Warburg Institute 2: 277–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).