Grounding the Landscape: Epistemic Aspects of Materiality in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Open-Air Painting

Abstract

:Nine-tenths of our backwardness has been due to the overwhelming embarrassment of picturesque material that has all along been at our very door—material which, by reason of its grandeur and sublimity, in no sort of fashion would do to make pictures of. Simplicity alone has evaded us all along.—Robert Swain Gifford, as quoted by Laffan and Strahan (1880)

Touch produces a form of confirmation of the subject-world at the interface between the materiality of that world and the hand.—Kevin Hetherington (2003), “Spatial Textures: Place, Touch, and Praesentia”

1. Introduction

2. Beyond “The Real” and “The Ideal”

[…] there is not an individual object in the picture which ever had its prototype in the natural world—not a tree, shrub or mountain form is there, which is not palpably a creation of the artist’s imaginative brain.10

What has [Bierstadt] done but twist and skew and distort and discolor and be-little and be-pretty this whole doggoned country? Why, his mountains are too high and slim; they’d blow over in one of our fall winds.

For the educated bourgeoisie, authentic experience of any sort seemed ever more elusive; life seemed increasingly confined to the airless parlor of material comfort and moral complacency. Many yearned to smash the glass and breathe freely—to experience ‘real life’ in all its intensity.(Ibid, p. 5)

The older morality embodied the ‘producer culture’ of an industrializing, entrepreneurial society; the newer nonmorality embodied the ‘consumer culture’ of a bureaucratic corporate state. Antimodernists were far more than escapists: their quests for authenticity eased their own and others’ adjustments to a streamlined culture of consumption.(Ibid, xxiii)

3. Down to Earth: Physical Engagement in the Work of Art

Canvases of large dimensions, too large to be carried to and fro, would be firmly fixed to upright stakes driven in the ground and, with the absorbent back of the canvas protected from the weather by oil cloth, would be left out of doors for weeks until the painting was completed. No other protection was necessary; the painted surface of the canvas was practically impervious to rain, and the chance faggot gatherers, the forest guards, or even errant children passing that way had, one and all, too hearty [a] respect for the arts to inflict the slightest damage on a painting in progress, thus left at their mercy. Many a picture in the museums to-day, protected by frame and glass, and the temperature of the gallery where it hangs carefully regulated, was thus born gipsy-like in the woods, where the shafts of sunlight by day and the stars by night watched curiously the progress of its growth.(Low 1908)

When [Currier] produces his impressions from nature in water-colors, it is his custom, I am informed by one who has seen him work, to put his paper on the ground, dip a brush into a convenient puddle and after well soaking the paper, pinch the desired colors directly on to it from the tubes and let them find their level; and it must be said that the “impressions” in water-colors Mr. Currier used to exhibit gave the impress of truth to this description.

4. Tiles, Hats, and Cheese

Then the club started for Sayville, […] the “Gaul” roaring loudly for a grocery store and cheese. The store was found, and while the unusual demand for cheese was being satisfied by the amazed proprietor, the “Owl” spied a pile of enormous hats of straw, with brims nearly six feet in circumference. He tried one on, gazed proudly around, and every Tiler bought one on the spot, at an outlay of twenty-five cents. Such a rushing hat trade never was done in Sayville before or since, and it is currently reported that the worthy grocer has never quite recovered from the mental shock that he sustained on the occasion.

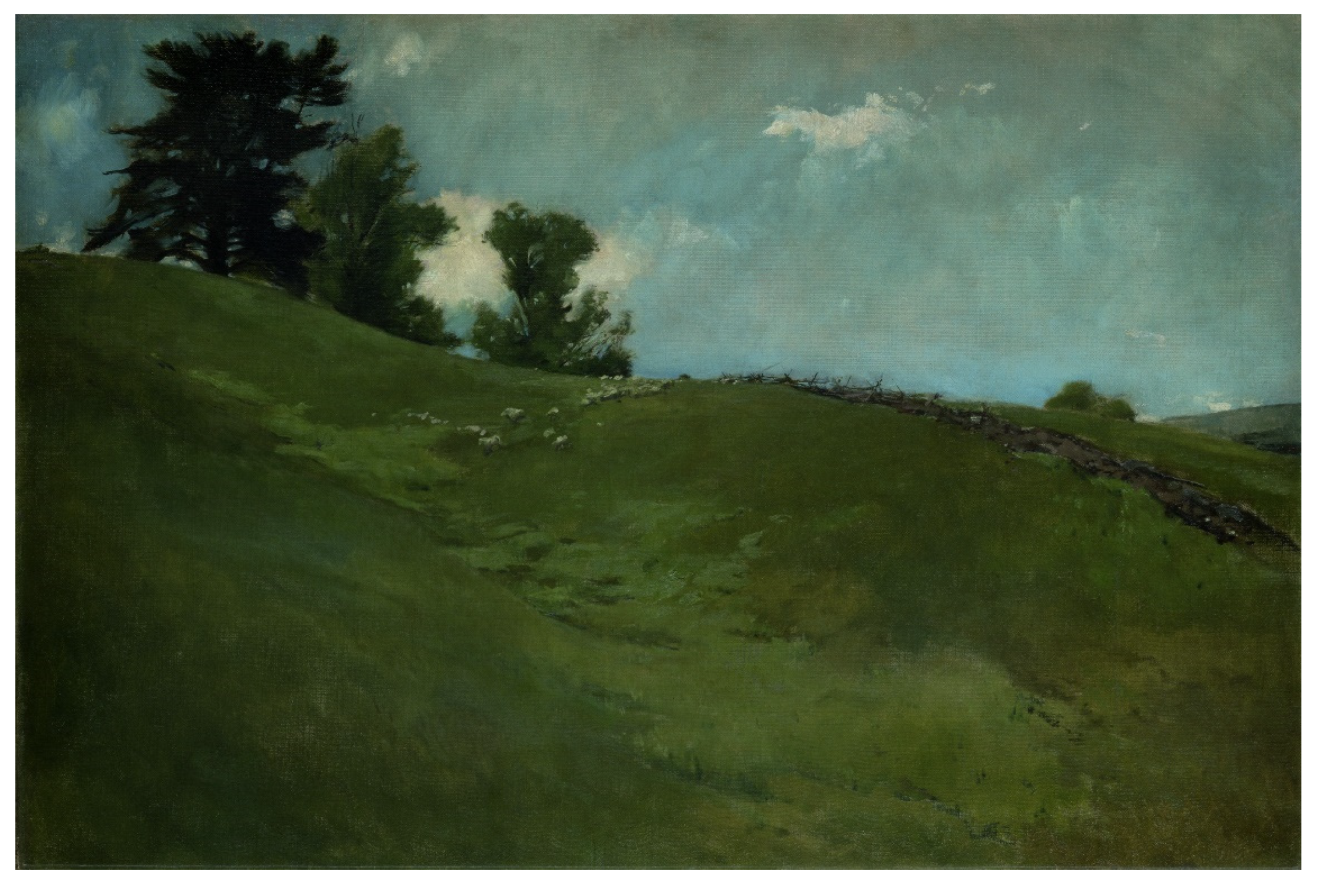

5. The Material of American Landscape

[…] our landscape art is and must be largely a matter of latitude. In its material it must be concerned with the things whereof we have the best and truest knowledge, whereof the images are implanted in our minds, and which we unconsciously love and cling to from mere association and familiarity.

The forms of our trees, the color of our vegetation, the moods of our skies, every physical manifestation of our daily life, are things understood by us and fitted to us and with which we are in full accord and sympathy.(Ibid.)

He could see. His mind was wholesome and sweet; he could discern his own natural impulses, and the ‘material of American landscape’ was not a sealed book to him. This material is what a majority of the men who study abroad seriously contemn and refuse to see, and as a consequence we have them painting bric-a-brac landscapes in their studios […].(Ibid)

American artists are withdrawing their allegiance from the Hudson River, the Falls of Niagara, the Rocky Mountains, and the big trees of Calaveras. A little introspective study, and such little humility as nearly a century of futility and arrogant ignorance has yielded to, have taught us to seek the humbler intimacy that Nature permits to us. There only may be attained such power to express her beauty and her simple truths as a natural reverence for them and a receptive and impressionable disposition render us capable of. From all this it follows easily enough that, if truth to Nature be any part of an artist’s art purpose, he can but seek it by looking where experience teaches him that his deepest sympathy and native function of expression most naturally lie.(Ibid, p. 32)

The highest art is where has been most perfectly breathed the sentiment of humanity. […] Some persons think that landscape has no power of communicating human sentiment. But this is a great mistake. The civilized landscape peculiarly can, and therefore I love it more and think it more worthy of reproduction than that which is savage and untamed. It is more significant. Every act of man, everything of labor, effort, suffering, want, anxiety, necessity, love, marks itself wherever it has been.

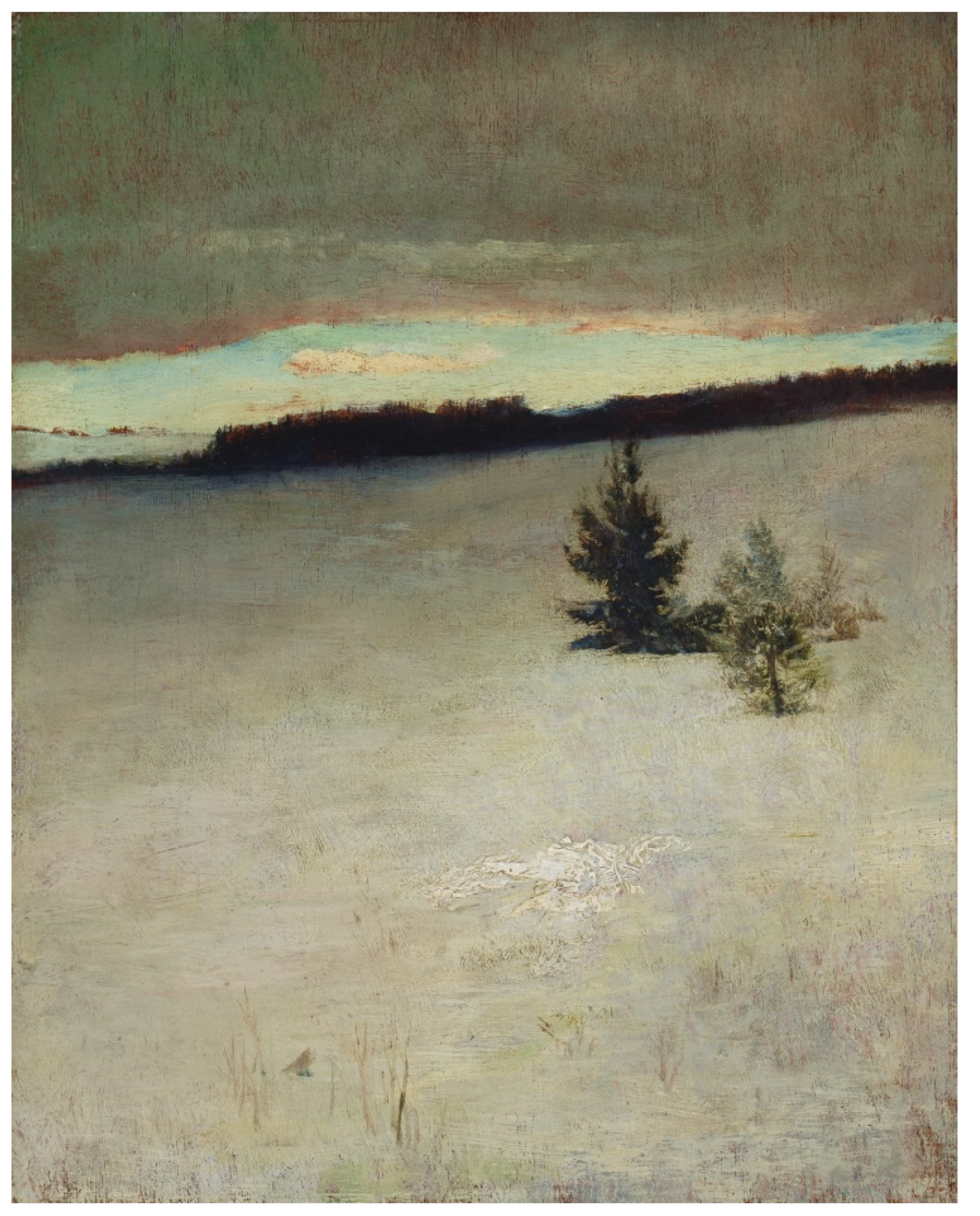

6. Building Dwelling Painting

…the forms people build, whether in the imagination or on the ground, arise within the current of their involved activity, in the specific relational contexts of their practical engagement with their surroundings.

The conceptual shift from landscape-as-image to landscape-as-dwelling correlates with a substantive shift from horizon to earth. In general, the proliferation of research on the body and embodied experience turns landscape from a distant object or spectacle to be visually surveyed to an up-close, intimate and proximate material milieu of engagement and practice. Landscape becomes the close-at-hand, that which is both touching and touched, an affective handling through which self and world emerge and entwine.(Wylie 2007, pp. 166–67, emphasis in original)

Touch produces a form of confirmation of the subject-world at the interface between the materiality of that world and the hand. Such an encounter is understood not as initially meaningful and representational to a subject who is distinct and distally knowledgeable about the world, but as constitutive […] of the subject itself.

We think of touch, at least initially, as up close, local, and specific (proximal) in its way of knowing. It is also inherently dialogical in character. We are often touched by what we touch.

Proximal knowledge is performative rather than representational. Its nonrepresentational quality is also context-specific, fragmentary, and often mundane. This contrasts with distal knowledge, which generally implies a broad, detached understanding based on knowledge at a distance or on a concern for the big picture. […] Distal ways of knowing are concerned with an ontology of being in which the ‘thing’ being known is assumed to be in a stable and finished state and thereby amenable to representation.54

7. A Matter of Surface

The problem that nearly every artist faced was to create an aesthetic product destined for the marketplace without appearing to collude too deeply with its commodification. The further from the realm of market activity an artist could position himself, the more legendary his status was likely to become.(Ibid, p. 67)

[…] have made considerable progress toward the acquisition of infallible art-recipes of their own. […] Is it that nature presents herself to these artists always under the same aspect? Or can it be that, having once succeeded in representing her under a certain form to the admiration of the crowd, they devote themselves thenceforth to the mechanical repetition of the effects by which they have won applause?(Ibid, 182)

Nothing could be more devoid of true sentiment than [these paintings], and they are now being very properly relegated to the ignominy of the makers of cheap chromos, whom Providence seems to have selected as the agents whereby to do full and poetic justice to everything of the kind.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | While American painters of the 1830s and 1840s formulated American landscape painting as a leading genre in American painting, aesthetically they were resting on established Neoclassical and Romantic conventions from England, France, and Germany (most notably the Düsseldorf School), and on the work of Claude Gelée (1604/5?–1682). See Novak (1980, 2007); O’Neill (1987). |

| 3 | By the time Haberle painted Torn in Transit, this perception was not new, as photographs and engravings of tourist attractions in the United States had become stock-in-trade since the mid-century. See Mackintosh (2019); Sears (1998). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Notice the half-torn signature of the artist, which suggests another layer of meaning: Playing on the theme of postal delivery, it is inscribed as “from… Haberle”, with the artist’s first name torn, therefore omitted. This implies the commodified attribution of the object (the work) to its maker, and is a play on the concept of “originality”, placing both object and authorship in an allegedly questionable or precarious state. Moreover, the artist’s signature—his affirmative mark of authenticity—is represented rather than a presented. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | On the Civil War as a national crisis and its reflection in the representation of the American landscape, see Harvey (2012). On the crisis of late nineteenth-century landscape painting, see Cao (2018). A fascinating study that challenges the binarity of “avant-garde painting” versus “academic painting” in European art is Rosen and Zerner (1984). |

| 9 | In American art literature, there is a tendency to define two major movements—Tonalism and Impressionism—through which late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists were consolidating themselves stylistically. However, the distinction is not always as clear and constructive as one would like it to be, and there are many liminal cases. In this paper I largely ignore such stylistic categorization, addressing instead the issue of materiality in open-air painting, while noting that both Tonalists and Impressionists employed open-air painting methods to various degrees. |

| 10 | The National Academy of Design (The National Academy of Design 1855). This attitude represented part of the public’s opinion, whereas for many, Cole was still exemplary of genius as founder of the national school of landscape painting. Karen Georgi wonderfully showed the controversy that raged in the New York art world concerning these subtle issues, the opposing opinion being that the excessive naturalism employed by painters such as Asher Durand reflected art having become a technical craft, lacking artistic imagination, and represented materialism. Georgi (2006). |

| 11 | The core group of these younger artists seceded from the National Academy of Design in 1877, claiming that the Academy was too conservative and stringent, and established the Society of American Artists, thus lending an institutional manifestation to these contradictory conceptions. This is yet another interesting aspect that unfortunately could not be developed here. |

| 12 | While late nineteenth-century painters sometimes considered open-air paintings to be accomplished paintings in their own right, for previous generations, outdoor painting functioned as a (sometimes essential) sketching phase. Nonetheless, the appreciation of outdoor sketches as works of art to be exhibited at shows began mid-century, as was shown by Harvey (1998). |

| 13 | Such influences were most notably French—whether the School of Barbizon, and later, French Impressionism, or individual teachers such as Thomas Couture (1815–1879) and Carolus-Duran (1837–1917)—but also influences from England, Germany (especially Munich), The Hague school, and the Old Dutch Masters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. |

| 14 | Some painters were known to even own a wagon or a boat to enable more accessible and convenient outdoor sessions. The more famous were the “floating studios” of artists such as Charles-Francois Daubigny (1817–1878) and Claude Monet (1840–1926), yet there are some interesting American precedents from the 1840s such as William Sidney Mount’s (1807–1868) “portable studio” furnished in a wagon (Novak 2007, p. 120). |

| 15 | This wonderful image was taken from the exhibition catalogue by Luijten et al. (2020). I am grateful to Juliette Parmentier-Courreau from the Fondation Custodia, Paris, for providing a high-resolution image. Unfortunate accidents while painting outdoors were the subject of some biographic anecdotes, often told in first person. One of the more famous was Monet’s description of himself painting at the Porte d’Aval, when a big wave dashed him into the water: “My immediate thought was, I’m a goner […] but I finally got on all fours, in such a state, Lord! […] the palette, still in my hand, hit me in the face, so my beard was covered in blue, yellow, etc. […] I lost my picture, which was quickly broken, along with my bag, my easel, etc.” Quoted in Wildenstein (2016), p. 265. This account and others reveal the miseries of the unfortunate open-air painter, at the same time as it shows the artist’s determination and willpower. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | On women American landscape painters, see Siegel (2011, pp. 149–84). Late nineteenth-century examples of open-air painting might be found in the works of prominent women painters such as Lilla Cabot Perry (1848–1933), Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942), and Evelyn McCormick (1862–1948), among others. |

| 18 | See, e.g., Brownell (1880, p. 10). However, this ultimate individualism, wherein an artist can invent his own techniques, was ambivalently received. American paint firms warned painters that “deterioration in hue” in contemporary paintings should be “attributed to the ignorance of the modern artist as regards the actual nature of the materials he employs.” Standage (1886). Quoted in Katlan (1999, p. 22). |

| 19 | Some painters overtly resisted varnishing, and aspired to simpler, less eye-catching frames. See Mayer and Myers (2013), esp. Chapter 2, “Eclectic Materials and Methods, 1860–1910.” On hastened or hastened-looking painting in French art, strongly influencing American art in this era, see Brettell (2000). |

| 20 | One can easily trace French philosophy, in particularly Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712–1778) ideas on the innocence of nature, echoing in Low’s description. |

| 21 | Apparently, none of Bunker’s paintings from his stay in England with Sargent survived, so it is impossible to know what was actually painted on his canvas. There is even an interesting possibility that Bunker painted Sargent on this occasion. See (Terra Foundation n.d.). |

| 22 | Munich had become the preferred location for studying in the early 1870s, when France’s painful defeat in the Franco-Prussian war and subsequent political instability rendered Paris a problematic place to study. Munich Royal Academy, with its less classical heritage, became for many Americans the forefront of modern painting, fusing the Courbet-influenced teachings of Wilhelm Leibl (1844–1900) with a great appreciation for the Old Dutch and Spanish Masters, such as Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666) and Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). However, in the 1880s, Paris regained its status as a European capital for the arts. |

| 23 | See Johnson et al. (2006, p. 68). Now a nearly forgotten painter, Joseph F. Currier was a well-known figure in the late nineteenth-century American art world. In fact, his artistic influence was so strong that the critic William Brownell claimed that Currier’s watercolors “became the subject of endless discussion and may almost be said to have divided ‘art circles’ into two hostile parties”. See W. C. Brownell, “The Younger Painters of America”, Scribner’s Monthly, 10. Surprisingly, the main scholarly resource about this fascinating artist remains Nelson White’s book from White (1936). Since then, an inclusive, updated monograph on Currier’s work has not been published to my knowledge. |

| 24 | The Art Amateur, Volume II, No. 8 (January 1883). Quoted in Rosenberg (1992), p. 144. Responding to this critical comment, Rosenberg remarks that “The medium transcends the barrier between artifice and reality, painted and real ground are wed and landscape is made from itself.” See Ibid, p. 145. Somewhat similarly, Twachtman’s habit of deliberately exposing his canvases to the sun and rain as a way to render representation a part of the physical landscape, was discussed in Gonnen, “Performing Openness”, pp. 44–45. |

| 25 | It is reasonable to assume that the practice of working on the ground was compatible with small formats and watercolor, and that while working outdoors with oil paints, especially on large canvases, Currier set his canvases vertically. |

| 26 | On the issue of staging spontaneity and its cultivation in French painting, see Brettell (2000, pp. 28–35). |

| 27 | On the American community in Polling, see Peters (2000, pp. 56–91). |

| 28 | Chase was also an avid collector of Currier’s works. See White (1936, p. 71). |

| 29 | The Realist tradition, intensely cultivated by painters such as Courbet and Millet, viewed the artist as a worker, proletarian, a comrade of the farmers and laborers who were the subjects of so many paintings during the era. See Callen (2015, pp. 105–58). Another worker’s identity was that of the artisan, notably constructed by the Arts and Craft movement that gained considerable influence in the United States. See Lears, No Place of Grace, Chapter 2: “The Figure of the Artisan: Arts and Crafts Ideology”, pp. 59–96. |

| 30 | In the first Scribner’s Monthly article on the Tile Club that appeared on January 1879, “The Tile Club at Work”, the reasons for the establishment of the Tile Club were explicitly explained: “’This is a decorative age,’ said an artist. ‘We should do something decorative, if we would not be behind the times.’” See Laffan (1879a, p. 401). |

| 31 | Note that some of those mentioned became famous only a decade or two later, and at least some of their public visibility can be credited to the Tile Club’s activity. For more information on the Tile Club, see Ronald G. Pisano, “Decorative Age? Or Decorative Craze? The Art and Antics of the Tile Club (1877–1887)” in Pisano (1999, pp. 11–69). |

| 32 | Using nicknames in the magazine’s article might have also served as mildly obscuring, separating between the amusing character of the published account and these artists’ more “serious”, respectable public personae in intellectual circles, connecting them with collectors and dealers. Although it was not hermetic, as there were some hints as to the real identities of the article’s subjects, such a separation served to preserve “appropriate” public appearance. |

| 33 | Laffan had a successful career as a journalist, later becoming editor of the New York Sun. Shinn, besides writing for several magazines on art issues, published several books on art and had a special interest in private art collections. |

| 34 | Art critic William Brownell stressed, “Nature is to [the new generation of artists] a material rather than a model.” Brownell (1880, p. 8). |

| 35 | Although this approach suggests a certain shift from the “exotic” travel of the Tile Club to rural Long Island, it is more likely that Laffan considered such relatively “near” locales (for New Yorkers or New Englanders) to be places of familiarity, versus the far West, the South, or Europe. Overall it is to be noted that Laffan wrote for the Bostonian American Art Review, thus aiming to awaken, first and foremost, Northeasterners’ sentiment. This aim correlated with late-nineteenth-century regionalism. On this subject in the context of American painting, see Rosenbaum (2006). |

| 36 | Ibid. The phrasing of this sentence is obviously very “Whistlerian”. James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) was a most influential figure on many American artists, and also embodied the link between the much-sought-after European training and American identity. His painting, notably his Nocturnes of the Thames, and his theoretical ideas—which were fundamental to Aestheticism—of “musical” color harmonies, were a model for landscape painting adopted by Americans. Yet despite having worked with Gustave Courbet in his early artistic career and befriending Manet, Monet, and other Impressionists, Whistler eventually had little significance to open-air painting, and his Nocturns were mostly reflective representations of visual memories and orchestrated, aestheticized compositions. |

| 37 | Although the identity of the painter remains anonymous, it was suggested that it was Twachtman, as besides being friends with Laffan, some biographical details in the description correlate with that of Twachtman. Moreover, the painting described matches some of Twachtman’s works. See Lisa N. Peters, “Twachtman’s Realist Art and the Aesthetic Liberation of Modern life, 1878–1883” in Peters, ed., John Twachtman: A “Painter’s Painter”, pp. 40–42. |

| 38 | Twachtman did adopt Laffan’s ideas by making the natural setting of his private property in Greenwich, Connecticut the almost sole subject of his work during the 1890s. See the recent exhibition and catalog, Peters (2021), Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman. The use of the terms “impression”, “impressionable”, and even “impressionist” in American journalism in the 1870s and the early 1880s rarely refers directly to the French movement or its influences; rather, the use of such terms is generic and descriptive, usually in the context of a looser handling of paint and a sketch-like appearance. |

| 39 | See, for instance, Henry James’ (1843–1916) criticism of paintings of rocks in Utah by Thomas Moran (1837–1926), for depicting remote locales: James (1875, pp. 95–96). |

| 40 | Inness was a prominent painter and intellectual who had a strong and lasting influence on the late-nineteenth-century art world. His conceptions regarding art also derived from Swedenborgian thought, which views the physical and spiritual worlds of existence as parallel one to another. Born in 1825, while Inness was of the same generation as the so-called “second-generation” Hudson River School painters (such as Frederic E. Church and Sanford R. Gifford), he radically changed his approach to landscape painting in the 1870s, therefore it spoke more to the ‘new generation’, affecting a great many of them. |

| 41 | This quotation originally appeared in an interview with Inness, published in Harper’s Magazine on February 1878. See Trumble (1895, p. 40). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | I do not contend, obviously, that these nineteenth-century figures shared the same worldview as late twentieth-and twenty-first century thinkers. I rather suggest that approaching the late nineteenth-century mindset and ideas about the landscape with the terms and tools of landscape phenomenology, might help us to clarify some points. The common criticism of phenomenological approaches is that they tend to overlook socio-political issues, gender, class, and race issues, etc. Nonetheless, phenomenology provides a valuable lens that helps to re-envision entities such as landscape, experience, and humanity; scrutinizing cultural epistemes, and addressing issues of embodiment, non-representation, and subject < > object relationship, all of which are consistent with this article’s main thesis. |

| 44 | Heidegger, “Building Dwelling Thinking,” quoted in Ingold, “Building, Dwelling, Living” in The Perception of the Environment, p. 186. |

| 45 | Ingold, “Building, Dwelling, Living: How Animals and People Make Themselves at Home in the World,” in The Perception of the Environment, p. 186. According to Paul Cloke and Owain Jones, who adopted Ingold’s “dwelling perspective”, dwelling is “about the rich intimate ongoing togetherness of beings and things which make up landscapes and places, and which bind together nature and culture over time.” Cloke and Jones (2001, p. 651). |

| 46 | Ingold, “The Temporality of the Landscape”, p. 207. |

| 47 | Merleau-Ponty himself, in order to demonstrate his ideas about perception, used late-nineteenth-century painter Paul Cezanne. Therefore, the link between twentieth-century phenomenological thinking and late-nineteenth-century painting has a previous basis. See Merleau-Ponty (1992). |

| 48 | The grounded boat in the painting, quite far from the water, provides another interesting perspective, especially with reference to the citation above. |

| 49 | See the description of this illustration in Laffan and Strahan (1879, p. 461). |

| 50 | The original work from which the engraving was made consisted of charcoal and body-color wash—the latter probably used to convey the earth’s texture. See Ibid. |

| 51 | See, for instance, Tilley and Bennett (2008), a study that takes a kinaesthetic approach—one that uses the full body and all the senses—rather than an iconographic approach to carvings and other forms of prehistorian rock art. |

| 52 | The high horizon line and flattened space in late-nineteenth-century landscape painting (both American and European) is regularly attributed to Far Eastern influences—most commonly Japanese prints—a notion that has become nearly axiomatic. While not dismissing this firmly established idea, I suggest here another perspective on this tendency in American art. |

| 53 | Hetherington studied visually impaired people’s experience of place. Notably, part of his research focuses on these people’s way of experiencing art at the museum. |

| 54 | Hetherington (2003, pp. 1934–36). Hetherington relies on the work of Cooper and Law, and Josipovici. Undermining the sense of vision and visual perception in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is explored in Jay (1993). It is interesting how the French word touche, “touch”, played a significant role in avant-garde jargon, standing for a daub of color and emphasizing the painter’s action. |

| 55 | This method of painting was termed by Joyce Hill Stoner “weavism”, and was often employed by artists related to the Tonalist movement. On the issue of painting’s materiality in the context of American Tonalism, see Stoner (2008, pp. 91–109). |

| 56 | For more research on the sense of touch and embodied experience in landscape painting of the Gilded Age, see Bell (2012, pp. 287–352). |

| 57 | Sartain’s words are worth qouting in this context, as his notions on simplicity and viewer’s vantage point relate to other aspects hitherto discussed: “[…] take two people with a camera—one who simply understands the working of the machine, and an artist who knows nothing about photographing, but who does know a picturesque spot that will make a picture when he sees it. The first man always wants to get up on a high place, where there is a fine view covering miles of scenery. […] He wants what he calls a ‘view.’ But the artist knows this will be uninteresting as a picture. There is too much in it. The eye becomes confused in trying to take in so many objects. […] One of the virtues of a landscape painting is that it suggests itself at once to the observer as a whole. […] [T]he painter […] is satisfied with interpretations on a smaller scale. He looks for ‘bits’ which he can handle successfully[…]. Some of the most successful and pleasing landscapes are often very simple in subject.” See interview in Ives (1891), pp. 81–82. |

| 58 | “The New Loan Exhibition,” New York World, 1880. Quoted in David Schuyler, “Jervis McEntee: The Trials of a Landscape Painter” in Nancy Siegel, ed., The Cultured Canvas, p. 203. |

| 59 | For more on the complexity of being between the marketplace and “ideal” art, see Chapter 2, “The Artist in the Age of Surfaces”, pp. 46–76. |

| 60 | Most of La Farge’s open-air oil paintings of landscapes were made during the 1860s and early 1870s, as in the mid-1870s and 1880s he was absorbed in his decorative and interior design projects. His later landscapes where mostly aquarelles. |

| 61 | Ingold, “Building, Dwelling, Living”, p. 186. |

References

- Baudrillard, Jean. 2006. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Adrienne Baxter. 2012. Body-Nature-Paint: Embodying Experience in Gilded Age American Landscape Painting. In The Cultured Canvas: New Perspectives on American Landscape Painting. Edited by Nancy Siegel. Hannover: University of New Hampshire Press, pp. 287–352. [Google Scholar]

- Boime, Albert. 1991. The Magisterial Gaze: Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting, c. 1830–1865. Washington: The Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, Doreen. 1990. American Artists and the Japanese Print: J. Alden Weir, Theodore Robinson, and John H. Twachtman. Studies in the History of Art 37: 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger Burke, Doreen, and Catherine Hoover Voorsanger. 1987. The Hudson River School in Eclipse. In American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School. Edited by John P. O’Neill. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brettell, Richard R. 2000. Impression: Painting Quickly in France, 1860–1890. Exh. Cat. The National Gallery, London; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Williamstown, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, William C. 1880. The Younger Painters of America. Scribner’s Monthly 20: 1–15, 321–35. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Sarah. 1996. Inventing the Modern Artist: Art and Culture in Gilded Age America. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Callen, Anthea. 2015. The Work of Art: Plein-Air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Maggie M. 2018. The End of Landscape in Nineteenth-Century America. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, Paul, and Owain Jones. 2001. Dwelling, Place, and Landscape: An Orchard in Somerset. Environment and Planning A 33: 649–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, Johanna. 1992. Harnett, Haberle, and Peto: Visuality and Artifice among the Proto-Modern Americans. The Art Bulletin 74: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esten, John. 2000. Sargent Painting Out-of-Doors. New York: Universe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, Karen L. 2006. Defining Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century American Critical Discourse. Or: Should Art ‘Deal in Wares the Age Has Need of’? Oxford Art Journal 29: 227–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonnen, Noam. 2022. Performing Openness: Open-air Painting and Conceptions of Openness in the Late Nineteenth-Century United States. Rutgers Art Review 38: 24–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Eleanor Jones. 1998. The Painted Sketch: American Impressions from Nature, 1830–1880. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Eleanor Jones. 2003. Tastes in Transition: Gifford’s Patrons. In Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford. Edited by Kevin J. Avery and Franklin Kelly. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Eleanor Jones. 2012. The Civil War and American Art. Exh. Cat., Smithsonian American Art Museum. Washington, DC and New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, Kevin. 2003. Spatial Textures: Place, Touch, and Praesentia. Environment and Planning A 35: 1933–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, A. R. 1891. Suburban Sketching Grounds. 1. Talks with Mr. William M. Chase, Mr. Edward Moran, Mr. William Sartain and Mr. Leonard Ochtman. Art Amateur 25: 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- James, Henry, Jr. 1875. On Some Pictures Lately Exhibited. Galaxy 20: 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Martin. 1993. Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark M., Margaret Lynne Ausfeld, and Charles C. Eldredge. 2006. American Paintings: From the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. Montgomery: Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Katlan, Alexander. 1999. The American Artist’s Tools and Materials for On-Site Oil Sketching. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 38: 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Clarence. 1935. Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. First published 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, W. McKay. 1879a. The Tile Club at Work. Scribner’s Monthly 17: 401–9. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, W. McKay. 1879b. The Material of American Landscape. The American Art Review 1: 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffan, W. McKay, and Edward Strahan (Earl Shinn). 1879. The Tile Club at Play. Scribner’s Monthly 17: 457–78. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, W. McKay, and Edward Strahan (Earl Shinn). 1880. The Tile Club Afloat. Scribner’s Monthly 19: 641–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. 2021. No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Leja, Michael. 2004. Looking Askance: Skepticism and American Art from Eakins to Duchamp. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Low, Will H. 1908. A Chronicle of Friendships, 1873–1900. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Luijten, Ger, Mary Morton, and Jane Munro. 2020. True to Nature: Open-Air Painting in Europe 1780–1870. Exh. Cat. National Gallery of Art, Washington; Fondation Custodia, Paris; The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. London: Paul Holberton Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh, Will B. 2019. Selling the Sights: The Invention of the Tourist in American Culture. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers. 2013. American Painters on Technique 1860–1945. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1992. Cezanne’s Doubt. In Sense and Non-Sense. Translated by Patricia Allen Dreyfus. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2004. Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Basic Writings. Edited by Thomas Baldwin. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Angela. 1993. Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation in American Cultural Politics 1825–1875. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mr. LaFarge’s Pictures. 1878. The American Architect and Building News 4: 182–83.

- Novak, Barbara. 1980. Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting 1825–1875. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, Barbara. 2007. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism, and the American Experience. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, John P., ed. 1987. American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Lisa N., ed. 2000. “Youthful Enthusiasm under a Hospitable Sky”: American Artists in Polling, Germany, 1870s–1880s. The American Art Journal 31: 56–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Lisa N., ed. 2006. John Twachtman (1853–1902): A “Painter’s Painter”. New York: Spanierman Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Lisa N., ed. 2021. Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman. Cos Cob: Greenwich Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, Ronald G. 1999. Decorative Age? Or Decorative Craze? The Art and Antics of the Tile Club (1877–1887). In The Tile Club and the Aesthetic Movement in America. Exh. Cat. The Museums at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY; Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, CT; The Frick Art Museum, Pittsburgh, PA. New York: Harry N. Abrams, pp. 11–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, Kathleen. 1996. Art and the Higher Life: Painting and Evolutionary Thought in Late Nineteenth-Century America. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jennifer L. 2014. Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jennifer L. 2017. Things: Material Turn, Transnational Turn. American Art 31: 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Charles, and Henri Zerner. 1984. Romanticism and Realism: The Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art. New York: The Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, Julia B. 2006. Visions of Belonging: New England Art and the Making of American Identity. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Eric Mark. 1992. Intricate Channels of Resemblance: Albert Pinkham Ryder and the Politics of Colorism. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, John F. 1998. Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Nancy. 2011. We the Petticoated Ones: Women of the Hudson River School. In The Cultured Canvas: New Perspectives on American Landscape Painting. Edited by Nancy Siegel. Durham: University of New Hampshire Press, pp. 149–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sill, Gertrude Grace. 2010. John Haberle: American Master of Illusion. New Britain: New Britain Museum of American Art. [Google Scholar]

- Standage, H. C. 1886. The Artist’s Manual of Pigments. Philadelphia: Janentzky & Webber. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, Joyce Hill. 2008. Materials for Immateriality. In Like Breath on Glass: Whistler, Inness, and the Art of Painting Softly. Edited by Marc Simpson. Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Terra Foundation. n.d. Available online: https://collection.terraamericanart.org/objects/553?_ga=2.65278189.2139239572.1670763142-553045844.1670763142 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- The National Academy of Design. 1855. Putnam’s Monthly 5: 506.

- Tilley, Christopher, and Wayne Bennett. 2008. Body and Image: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology 2. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Trumble, Alfred. 1895. George Inness, N. A.: A Memorial of the Student, the Artist, and the Man. New York: The Collector. [Google Scholar]

- White, Nelson. 1936. The Life and Art of J. Frank Currier. Cambridge: The Riverside Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wildenstein, Daniel. 2016. Monet: The Triumph of Impressionism. Koln: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, John. 2007. Landscape. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonnen, N. Grounding the Landscape: Epistemic Aspects of Materiality in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Open-Air Painting. Arts 2023, 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010036

Gonnen N. Grounding the Landscape: Epistemic Aspects of Materiality in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Open-Air Painting. Arts. 2023; 12(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonnen, Noam. 2023. "Grounding the Landscape: Epistemic Aspects of Materiality in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Open-Air Painting" Arts 12, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010036

APA StyleGonnen, N. (2023). Grounding the Landscape: Epistemic Aspects of Materiality in Late-Nineteenth-Century American Open-Air Painting. Arts, 12(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010036