Abstract

This article examines contemporary artists’ appropriation of the city of Brasília to critique Brazil’s continued reliance on the “unfinished” project of modernity. Exploring the construction of the scenography of Brasília and its resonance with the architecture and organization of space in the colonial plantations, the works of contemporary artists Lais Myrrha (Estudo de Caso [Case Study], Estudo para um Futuro Construído [Study for a Constructed Future]), and Talles Lopes (Construção Brasileira [Brazil Builds]) allows us to reconnect Brasília with the backdrop that gave rise to this ideal. These works invoke the reconciliation of the colonial matrix of power in Lucio Costa’s discourse about modernist architecture in Brazil, of which Brasília is the culmination. Myrrha’s and Lopes’ works show that the history and legacy of Brasília, not only as an idea but also as form, are embedded in the Brazilian imaginary and built environment in the contemporary moment.

1. Introduction

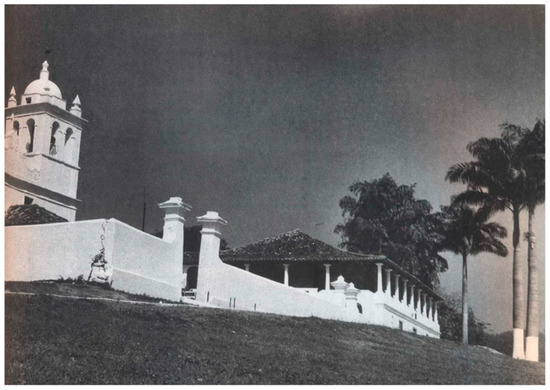

Lais Myrrha’s1 2018 installation Case Study (Figure 1) is an arrangement of life-scale plaster reproductions of the column designed by Oscar Niemeyer for the Palácio da Alvorada [Palace of the Dawn] in Brasília and one of the columns from the Colubandê plantation manor. Built in São Gonçalo, in the state of Rio de Janeiro in the 18th century, the Colubandê manor is a prototypical Brazilian colonial-style structure (Cardoso 1943; Brittan Trindade 2013). In Gilberto Freyre’s canonical study Casa Grande e Senzala [The Master and the Slave], first published in 1933, the author argued that the organization of space in the Brazilian plantation was foundational to modern society, particularly in its accommodation of circulation between the two main architectural structures: the plantation manor and the slave quarters.2 The pairing of Niemeyer’s Alvorada column with a copy of the central element of the architecture of the Colubandê casa grande (Figure 2) in Myrrha’s Case Study highlights the inextricability of Brazil’s fiction of modernity from its enduring coloniality. As Fernando Luiz Lara argues in his A Stitch in Time: the legacy of colonialism in the Americas, the stitching together of modernity and coloniality within Brazilian modernist discourse that is highlighted in the work of Myrrha, cannot be seen as a question simply relevant to architectural history; rather, looking at these through a decolonial lens promotes an analysis of contemporary capitalism, racism, exploitation, extractivism, and the built environment as results and tools of “colonialist spatiality” (Lara 2019).

Figure 1.

Lais Myrrha, Estudo de Caso [Case Study], 2018, replicas 1:1 of columns in plaster, Gwangju Biennale, courtesy of the artist.

Figure 2.

Colubandê Plantation House, photograph by Lúcio Costa, courtesy of archive IPHAN Rio de Janeiro.

This discussion is particularly poignant for works such as Myrrha’s Case Study because Brasília was—and arguably still is—a materialization of the Brazilian desire for modernity in that it is simultaneously a dreamscape of the Brazilian elite and a physical manifestation of the violence of coloniality (Vidal 2009). It is important to remember that the ideal of a capital city in the backlands far predated the actual construction of the city, and this rhetoric has served colonial, neoliberal, left-leaning, and authoritarian governments alike in the last sixty years. Ideological agendas as disparate as the military regime—that overtook the country shortly after the inauguration of Brasília in 1964—and more recently, the leftist project of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s Partido dos Trabalhadores [Worker’s Party, PT] have reconfigured nationalism in Brazil in a myriad of ways. Nevertheless, progress—and Brasília as symbolic of this rhetoric—has remained at the center of the Brazilian political imaginary (De Carvalho 2012; Bethell 2002; Buarque 2013). That is, until very recently. The rise of Jair Messias Bolsonaro in 2018 and the hate speech that distinguishes his supporters is poignantly tinted by the emptying of the centuries-long reliance on modernity as a locus of adherence for Brazilian collectivity.3 Contrary to previous regimes, the spectacle of amateurish politics that is Bolsonaro’s brand is delineated by a rhetoric of the end, which has resulted in catastrophic environmental, human rights, and labor policies that have razed decades of political activism by various underrepresented communities (Nunes 2022b). The recent invasion and depredation of the government buildings in Brasília by a pro-Bolsonaro far-right mob have further showcased the way the city’s-built space acts as a springboard for dissonant affects within the Brazilian body politics.

Brasília has occupied a particularly ambiguous position since the beginning of its construction in 1957. While it secured a place in the architectural canon and became renowned internationally, the city was already proclaimed a failure as early as 1958 (Xavier and Katinsky 2012). Furthermore, in 2022, it seems to have lost some of the aura of modernity that has been the city’s brand since its inauguration.4 Despite this most recent challenge to the narrative of modernity—or arguably in consequence of this—the imbrication of this rhetoric in the Brazilian social fabric is a question that has been avidly investigated by many contemporary artists (Rigby 2014). The increasing interest of contemporary artists in utopian narratives, and Brasília in particular, since the late 1990s cannot be disregarded as just part of contemporary art’s coming of age and challenge to modernism. More than formal and conceptual engagements with the legacy of the European avant-gardes, International Style Architecture, Cold War high modernism such as Latin American geometric abstraction, Pop, and Conceptual art, this concentrated attention on Brasília springs from a need to grapple with longstanding power structures that have shaped Brazil since the colonial encounter. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight also that the artworks discussed here are part of a larger universe of artistic practices attempting to come to grips with the utopian narratives that marked the 20th century and its legacy in our current moment.

Among the contemporary works that engage the diffuse power of the ideal of modernity over the Brazilian imaginary, there has been a significant interest in mobilizing the image and materiality of Brasília (Kim 2018; Mammí 2012). That is because, even though the city has been amply criticized since its inauguration in 1960, from architectural, urbanism, and ideological points of view, the inextricable relationship between modernity and coloniality in the discourse and everyday life of the capital continues to be disavowed. This article focuses on the work of Lais Myrrha and Talles Lopes because they show the engagement of contemporary artists with the symbolic forms of Brasília firstly, and secondly, the interdependence between the discourses of heritage and modernity/coloniality within the Brazilian national rhetoric starting in the 1930s, which their installations explore.

Aníbal Quíjano’s (1992) elaboration of the “colonial matrix of power” synthesizes contemporary relationships of power by bringing to the fore their racialized and extractivist dimensions. As he argues, the construction of new geocultural identities starting in the 16th, but especially in the 18th century, was grounded on the assumption, first and foremost, that Europe had the patent on modernity as a historical, cultural, and essentially racial development. This enduring rhetoric frames modernity as a result of rational evolution that ultimately is a cognitive model locating all knowledge systems and non-European peoples firmly in the past and yet-to-be-modern. As Quíjano highlights, one of the keys to this Eurocentric rhetoric of modernity is the mystified idea of progress in both its economic and racialized dimensions: understood through a “quasi-exclusive association of whiteness with wages,” placing in the same axis the colonial violence and control over specific peoples, forms of labor, and pseudo-scientific theories like eugenics. Thus, “race/labor was articulated in such a way that the two elements appeared naturally associated”; the inferiority of the non-European races reflected in their subjugation to non-waged labor—for example, slavery and serfdom, but also independent commodity production—rather than commodified labor (Quíjano and Ennis 2000, p. 537). The long-lasting impact of Quíjano’s proposition lies in his recognition of the inextricability of modernity as an ideological discourse—the idea of the new, its evolutionary narrative, and Europe’s self-becoming—from the colonial relations of power, capital, and extractive production that gave rise to it and still underline it today.5 More recently, among other scholars that have continued to unravel the endurance of the colonial matrix of power in our contemporary society (Mignolo and Walsh 2018), Ariella Aïsha Azoulay in Potential History (Azoulay 2019) has proposed a reexamination of the continued investment in fictions of progress and modernization in the global imaginary particularly as it relates to imperialism’s major mechanics in photography and material culture. Two of Azoulay’s propositions are of particular interest to us here. First, the notion of images and cultural objects as resources extracted from dominated peoples and the fallacy of their reproduction as neutral; and second, the continued traction of the Western fiction of modernity in constituting peoples as agents of progress, colonizing our global imaginary.

In the context of Brazil, the continued traction of the fiction of modernity is most clearly materialized in the ideal of the country of the future (De Carvalho 1995; Sader and Garcia 2010; Bethell 2002; Buarque 2013; Resende 2001; El-Dahdah 2010). Underlining the Brazilian ideal of futurity is the erasure of historical debt to indigenous populations, descendants of the African slave trade, and the environment that has been constantly abused, exploited, and undermined in the last five centuries. These deeply rooted structures of power are the consequence of a series of carefully crafted narratives about the nation within which architecture—and particularly modernist architecture—plays a key role.

This article focuses on the works of contemporary artists Myrrha and Lopes as they mobilize the city of Brasília—considered the acme of Brazilian modernist architecture—to forefront the dependence of Brazil’s fiction of modernity on the colonial structures of Brazilian society. For this, the article examines two installations from Myrrha’s Studies series and Lopes’ photobook and installation Construção Brasileira [Brazil Builds]. While Myrrha’s Case Study and Study for a Constructed Future point to the reconciliation of modernity and coloniality in the discourse of Brazilian modernist architecture, one that was engineered by Lucio Costa starting in the late 1930s; Lopes’ work explores the publicity surrounding this fiction of modernity and its dissemination throughout the Brazilian built environment. Especially, Lopes’ Construção Brasileira shows how Niemeyer’s Alvorada column came to symbolize both modernity at large and the possibility of possessing it within the Brazilian imaginary in the second half of the 20th century. These issues raise questions about Brasília’s position as a UNESCO heritage site and how this has stunted the growth and change of the city; especially, it opens the door for a reflection on how the city may be slowly losing its ability to stand in for an ideal of the nation and instead becoming, although ambiguously in the eyes of far-right supporters of Bolsonaro, a symbol of the collectivity they despise.

Therefore, the works in this article expose the histories of Brazilian modernity: the violence and the conflict of Brazil’s colonial legacy and modernist architecture’s deep-rooted connections with it, as well as the aging of these ideals. In Brazil’s current political context, it is ever more important to understand the role Brasília played in the country’s mid-20th century neocolonial programs, especially as the capital’s construction in the Brazilian backlands was grounded in projects that aimed at ever more aggressive extractive practices and the displacement, dispossession, and exploitation of indigenous and Afro Brazilian communities. However, these political and economic intricacies have remained—even in the scholarly discourse—hidden behind a mythical narrative of progress and national integration that has obscured the deeply ingrained colonial matrix of power within the Brazilian social structure. How do Myrrha and Lopes’ works question the ways architecture and heritage have been instrumentalized to obscure the violence of coloniality in the construction of Brasília? How is this disavowal of the colonial matrix of power in Brazilian architectural discourse materially reproduced in contemporary Brasília? How do recent events show us the continued importance of these narratives within the national imaginary? These are some of the questions this article will tackle.

2. Building Modernity

The 1950s marked a particularly optimistic period in Brazil’s political and economic history. Nicknamed Os Anos Dourados [The Golden Years], this period represented the acme of a national utopian narrative of progress and modernization that was already well established in the early decades of the Getúlio Vargas era (Williams 2001). Centered on large infrastructure projects across the country, especially highways, dams, hydroelectric plants, and increasingly aggressive resource extraction, agriculture, and cattle farming, the mid-century also saw the question of Brazilian cultural identity as central to the political debate. Modernist Architecture posed the perfect answer to these concerns, especially as the movement came to align utopian rhetoric and biopolitics (Cavalcanti 2006). This political, economic, and cultural alignment came to a tipping point in the city of Brasília. That is because the experience of Brasília, the modernist capital built in less than three years in the Brazilian backlands, has often been thought of as the experience of futurity itself, the discursive tropes of “the dawn of a new age” and “the birth of a nation” associated repeatedly with the idea of “the first modernist capital.” This wonderment about the new capital was where the rhetoric of the International Style of architecture met 20th-century neocolonialist politics in Brazil. Hidden behind this constructed history of the city are the violent war that was waged against the land and peoples of the Brazilian central plateau and the many challenges that arose from the construction of the city in an environment the federal government, architects, urbanists, and engineers knew very little about (Madaleno 1996; Tavares 2020).

Paramount to understanding the role Brasília plays in the larger history of Brazil are the ways the narratives about the city that still prevail today serve to erase the importance of the Brazilian hinterlands in the process of modernization, narratives about the nation that remain at the forefront of political discourse in the country today (Correa 2016; Tavares 2022b). Erased from the epic narrative of Brasília is the wealth of the country’s interior, especially its water and land resources, and the history of indigenous resistance to “pacification” processes in the region (Karasch 2016). Mentions of the riches of inland Brazil appear in political discourse throughout the centuries very rarely, and when they do, it has always been in the context of mining in the states of Minas Gerais and Goiás. Nevertheless, it has become increasingly clear in the last 70 years that the hydric, agricultural, and cattle farming potential of the region surrounding Brasília is massive and was only beginning to be explored during the presidency of Juscelino Kubitschek in the mid-1950s (Correa 2016). Even though that potential was already clear to economists and government alike in the mid-century, the value of the central plateau as it existed at that time—the knowledge systems and ecologies that constituted that space, especially those of the Karajás, quilombola, and the ribeirinho communities—were incompatible with the geographic, environmental, and infrastructural changes necessary for the implementation of modernization programs such as Kubitschek’s “Fifty Years in Five” plan, not to mention the interests of national and foreign capitalists backing these endeavors.

Therefore, within a wider discourse that started to be configured in the 18th century, the interior of Brazil was framed as an empty and violent no-ones-land that needed to be tamed (Karasch 2016; Vidal 2009). Following suit, Brasília continues to be described as exemplary of the modernist architecture and urban design impulse in Brazil of the mid-20th century and a feat of the national will to modernize (Holston 2009; Gisbourne 2010, for example). The city remains a monument to this 1950s optimism, working to deny the violence perpetrated against the hinterlands in the process of reconfiguring the geography of South America (Madaleno 1996; Tavares 2020).

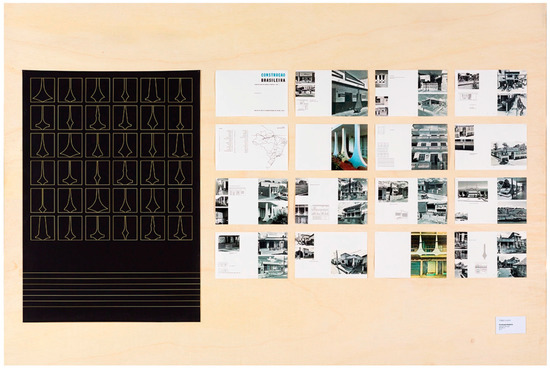

Talles Lopes’6 installation and photobook Construção Brasileira (Figure 3) pokes at precisely this narrative and the vehicles for its dissemination and propagation within the Brazilian imaginary, especially in the early twentieth century. Lopes’ project highlights the publicity strategies and the foreign interests that were foundational to the modernist architecture movement and neocolonial modernization project in Brazil in the 20th century. Construção Brasileira is a photobook—often exhibited with its pages spread across the wall in the form of a photo-essay installation—which appropriates both the format and graphic design of Phillip Goodwin’s 1943 publication Brazil Builds (Figure 4).7 In 1942, in preparation for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition, Goodwin traveled to Brazil accompanied by architectural photographer G. E. Kidder Smith to visit several regions across the country and examine architectural works built starting in the 17th century (Quezado Deckker 2001). These architectural projects were said to be an original development of European design premises with the quality of the architecture matching modernist standards of excellence in design, but the reason they called so much attention was the association established between the baroque and the modernist movement in the country (Goodwin et al. 1943; Quezado Deckker 2001). MoMA’s Brazil Builds remains a central point of reference for the historiography of Brazilian architecture, especially because of its validation of a narrative of continuity between the baroque and the modernist movement elaborated by the future planner of Brasília, Lucio Costa, and its dissemination through IPHAN [Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional; Institute of the National Historic and Artistic Patrimony] (Costa 1937; Ferreira Santos 1986; El-Dahdah 2006; Conduru 2008; Lara 2008; Tavares 2022a) starting in the 1930s.

Figure 3.

Talles Lopes, Brazil Builds: Architecture Modern and Old, 1958-, 2018, installation, courtesy of the artist.

Figure 4.

Antônio Francisco Lisboa, São Francisco de Assis Church, Ouro Preto, 1771.

As head of IPHAN and ENBA [Escola Nacional de Belas Artes; National School of Fine Arts], and a main figure of the architecture milieu in Brazil of that time, Costa was particularly well positioned to spearhead the idea that modernist architecture—what came to be known as the Brazilian Style—was a direct descendent of colonial architecture in the country. Not only did Costa propose that the two movements were connected, but he also asserted that the colonial movement was the first explicitly Brazilian form of expression. As the leader of a young group of Brazilian architects—that included Oscar Niemeyer—referencing modernist architects such as Le Corbusier and the Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne [The International Congress of Modern Architecture, CIAM], Costa headed the design team for the Ministério da Educação e Saúde building [Ministry of Education and Health, MES], which became one of the most emblematic modernist projects in the country. Even though Costa was not the most prominent designer in the MES project, he was by 1937 the modernist movement’s main narrator and built a genealogy for the movement through his memorialist and theoretical writings. It was also in 1937 that IPHAN was founded, and at its helm, Costa was able to classify as national heritage several buildings and sites constructed between the 16th and the 18th century and fortify the discourse of the colonial architecture in the country as “essentially Brazilian,” elevating it as the precursor to modernism (El-Dahdah 2006; Lara 2008).

Therefore, we can see that between 1937 and 1964, Costa simultaneously spearheaded two projects: on the one hand, the historicization of Brazil’s modernist movement, connecting it to colonial architecture, and on the other, the consolidation of the idea of the country’s baroque architecture as an original manifestation of Brazilian culture. MoMA’s Brazil Builds was part of the process of constructing this architectural history. Reproduced in what are now canonical texts of Brazilian architecture history, such as Henrique Mindlín’s Modern Architecture in Brazil (Mindlín and Giedion 1956) and Yves Bruand, Arquitetura contemporânea no Brasil (Bruand 1997), Costa’s assertion that Brazilian colonial and modernist architecture was part of the same lineage steeped through the specialized and popular discourse continuing throughout the years in the work and writings of figures such as Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade (Tavares 2022a), the next director of IPHAN. Costa further emphasized that the connection between baroque and modern architecture was a particularly original Brazilian development since, different from Europe, baroque in colonial Brazil was, as Siegfried Giedion put it: “severe, solid and unadorned” (Mindlín and Giedion 1956). In Modern architecture in Brazil (Mindlín and Giedion 1956), Mindlín adds that “this tradition [Brazilian colonial baroque], or rather, the spiritual attitude it reflected, brought to self-awareness by the ideas advanced by Le Corbusier, whose work focuses all contemporary achievements, was the one which served as the foundation for the modern architecture movement in Brazil.” As such, Brazil Builds (Goodwin et al. 1943) showcases the beginning of the dissemination of a narrative that has been consolidated in the architectural historiography in Brazil starting in the 20th century. This narrative directly tied buildings such as Antônio Francisco Lisboa’s São Francisco de Assis Church [Church of San Francis, Figure 4] in Ouro Preto and the Colubandê master house in São Gonçalo to the lightness, curves, and free-form style of Oscar Niemeyer.

3. Construção Brasileira

Lopes’ photobook Construção Brasileira closely follows the typography, color scheme, and arrangement of the catalog produced to accompany MoMA’s 1943 exhibition Brazil Builds. However, in place of the prominent examples of Brazilian baroque and modernist architecture in the museum’s publication, Lopes inserts contemporary photographs—found, gifted, taken by the artist and from Google Street View—that showcase popular appropriations of Niemeyer’s Alvorada column (Figure 5). In the pages of Construção Brasileira, these reverberations of Niemeyer’s column in park benches, porch rails, verandas, and façades of public and residential buildings found across the Brazilian territory occupy the space once reserved for consecrated works of “high” Brazilian architecture (Figure 6). Lopes’ appropriation of MoMA’s Brazil Builds points to the central role played by the book and the exhibition in the consolidation of the discourse of Brazilian modernism propelled by Costa, but also how these remain central points of reference for the historiography of Brazilian architecture because Brazil Builds validated Brazilian modernist architecture as part of an autonomous genealogy for an international audience (Quezado Deckker 2001; Costa 2009; Scottá 2018). Brazil Builds has been key in endorsing the rhetoric of continuity between the colonial and modernist architectural movement in Brazil, which most importantly configured a reconciliation between modernity and coloniality, further erasing the contradictions embodied by this colonial matrix of power.

Figure 5.

Talles Lopes, Brazilian Construction: Architecture Modern and Old, 1958-, 2018, photobook, courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6.

Talles Lopes, Brazilian Construction: Architecture Modern and Old, 1958-, 2018, photobook, courtesy of the artist.

This amalgamation of the modernity/coloniality structure within Brazilian modernist architecture is further relevant if we examine the context within which it came to be elaborated by Costa. By 1939, Brazil was at the center of modernist architectural debates worldwide.8 In the span of a few years, the interest in modern Brazilian architecture had skyrocketed: drawings, plans, and photographs of modern constructions in the country—like the MES building—had appeared in specialized journals such as Casabella and Architectural Record and the inauguration of the Brazilian Pavilion at the New York World Fair was a resounding success (Le Blanc 2009; López-Durán 2018). Nevertheless, the reasons behind MoMA’s enthusiasm for Brazilian modernist architecture were twofold: on the one hand, the Brazilian style was an important development of the International Style, which the museum had championed since 1932 (Hitchcock and Johnson 1996), while on the other, culture was a key point of access for soft power as promoted by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy and advanced by Nelson Rockefeller’s Center for Inter-American Relations (Quezado Deckker 2001). As World War II raged and the US grew concerned about German and Italian influence in Brazil, it became increasingly important to establish connections there, but Brazilian modernism also provided a particularly interesting case of whitewashing and rebranding of problematic and highly racialized architectural discourses that were becoming increasingly unpopular during that time (Hochman 1979; De Jarcy 2015). Le Corbusier and Costa shared strong views about the relationship between the country’s architecture and its “racial question.” As Paulo Tavares and Fabíola López Durán have discussed in recent publications on this theme, these architects partook in a biopolitical discourse that was widespread in architectural circles across the world in the 1930s and has been disavowed in the history of architecture since (Lopéz-Durán 2018; Tavares 2022a).

Costa, in particular, was among a series of Brazilian intellectuals that openly endorsed the ideology of whitening and eugenics in the first part of the 20th century. In an interview in 1928 entitled Toda arquitetura é uma questão de raça [All architecture is a question of race], Costa asserts:

While our people are this exotic thing that we see along the streets, our architecture will forcibly be an exotic thing. It is not this half dozen that travels and dresses in the rue de la Paix, but the anonymous mass […] that embarrass us everywhere. What can we expect of the architecture of such a people? Everything is a function of race. If the race is good, then the government will be good, and the architecture will be good.(Costa apud Tavares 2022a, translation mine)

While the racism in his rhetoric waned—or was disavowed—towards the end of the 1930s, Costa’s racialized views and commitment to biopolitical ideals did not. What becomes central to the reconciled coloniality/modernity narrative elaborated by Costa starting in 1937 is the incorporation of the rhetoric of racial democracy of Freyre. The organization of space is foundational to Freyre’s argument in his Casa Grande e Senzala where he proposes Brazilian culture is the result of “um amolecimento” [a softening] of European culture through the influence of the tropics and its indigenous and African elements (Freyre and Putnam [1933] 1956; Tavares 2022a). Missing from Freyre’s narrative is the sexual and colonial violence that resulted in the miscegenation of the Brazilian population and the flux between the master house and the slave quarters, which he argued was emblematic of Brazil’s colonial structure and foundational to the country’s modern society (De Souza 2008; Munanga 2004; Schwarcz 1999).

Goodwin’s portrayal of Brazilian architecture in Brazil Builds (Goodwin et al. 1943) was largely curated by Costa and reflected the racialized views that are at the root of the modernist movement. Lopes’ appropriation of the design of MoMA’s book opens the door for him to hack this narrative, and in many ways, Construção Brasileira showcases both the power of the ideological apparatus that was Costa’s reconciliation of the coloniality/modernity chasm in Brazil, but also its reconfigurations in a country that has enshrined the ideal of modernity as its own predestined future. The photo essay in Construção Brasileira is about the desire to own modernity and the place of Niemeyer’s Alvorada column (and Brasília) within this imaginary. Raising popular architecture to the level of “high architecture” in the pages of Lopes’ book simultaneously reflects and challenges the discourse of Costa and Niemeyer about architecture in general and Brasília in particular. However, by appropriating the visuality of Brazil Builds to showcase the popular reconfigurations of Niemeyer’s high art vocabulary, Lopes also brings deep anxieties that shape contemporary Brazilian society to the fore.

Lara has argued that modernist forms and building modes have become the main technical vocabulary in Brazil’s built environment (Lara 2018), an assertion Lopes’ work empathically exposes. Across the continental-size country and among all social strata, modernist architecture has—since the 1950s—become widespread in Brazil because it is the construction vocabulary that workers that built structures like Brasília absorbed and reproduced in their own residences, even if disengaged from the formal premises of that vocabulary and international ideals of modernist architecture. The discussion around what Lara calls the exceptionalism of Brazilian modernism—that is, its ability to bridge high and low, elite and popular—is the result of deep anxieties about the disruption of colonial structures and asymmetry of power in contemporary Brazil, but also a consequence of the reconciliation of colonial and modern in Costa’s architectural narrative. If the stripped baroque architecture of which the Colubandê plantation house is exemplary should be accepted as a manifestation of Brazil’s original culture and the root of its modern impulse, the promise of the inversion of power central to the neocolonial discourse of the 1950s and Brasília in specific—the idea of the Brazilian coastal elites as conquerors of the backlands, its natural wealth, peoples and ways of life—gives way to the conquest of modernity by a lower-class mixed-race population through the medium of architecture. This population’s use of modernist architectural vocabulary that Lopes explores in Construção Brasileira is as deeply rooted in an ideal of futurity as Niemeyer’s work in Brasília. However, while this appears to be a logical continuation of Costa’s reconciliation of coloniality and modernity within Brazilian architecture and society, it is antithetical to the racial and biopolitical discourse that, in fact, underlines modernist architecture in Brazil and the project of Brasília.

4. Studies on Coloniality

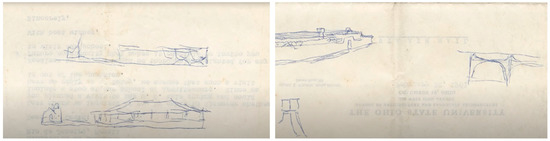

In Myrrha’s Case Study, the imposing and iconic form of Niemeyer’s Alvorada column stands precariously on its side as it balances atop a reproduction of the Colubandê plantation column (Figure 7). Intrigued by the idea that the capital’s Palácio da Alvorada was influenced by the design of the master house at Colubandê—which Myrrha points out is established by a sketch comparing the two made by Costa (Figure 8)—the artist decided to put the two in conversation in her work for the 2018 Gwanju Bienal.9 Case Study speaks to the development of Costa’s modernist architectural vocabulary but presses the modern and the colonial even closer together. Myrrha remediates Costa’s historicization of the architectural program of Brasília (and Brazilian modernist architecture) by placing the two columns on the same axis, highlighting the established alignment between modernist and colonial architecture in the country by placing them in a fragile equilibrium. In particular, the artist posits: “for the survival of these two columns, the traditional and the modernist, it is necessary for the work to remain static because the loss of this delicate balance would mean mutual damage” (Myrrha 2018). The dependence of the modern project in Brazil on the structures of its colonial past is to be studied by the viewers of Myrrha’s work as it points to this essential condition of Brazilian society.

Figure 7.

Lais Myrrha, Case Study, 2018, replicas 1:1 of columns in plaster, installation at Gwangju Biennale, courtesy of the artist.

Figure 8.

Lúcio Costa, Sketches on the back of a letter sent from Ohio State University, courtesy of archive of IPHAN, Rio de Janeiro.

Similarly, Brasília depends on a delicate and static balance. In 1987 the city was proclaimed a world heritage site by UNESCO, and within that framework, resistance to any alteration or adaptation of the city’s plan—its Plano Piloto—has meant that while its form has retained the condition of possibility for the iconic images of the city in photographs by Marcel Gautherot, Lucien Clergue, René Burri, and others; the incongruities in the project have become ever more glaring (Lara and Nair 2007). Nevertheless, the contradictions within the narrative of Brasília have been interpreted very differently by the main figures responsible for the shape of the city. While in an interview in 1964, Niemeyer hoped that “Brasília one day will be a city in line with how it was projected, without social discrimination or discrimination of any class,” since “[a]t this moment, those who built Brasília, the workers, live fifty kilometers from the city, […] one day they will arrive inside the city to place themselves next to the others, just like we hoped they would” (Esther 1964, translation mine). Costa, contrastingly said in 1984 of the workers that swarm the city every day, arriving from the far-fetched peripheries into the central bus terminal, whom are responsible for the labor that maintains the manicured image of Brasília:

I was struck by reality, and one of the realities that surprised me was the Bus Station, early at night. I always repeated that this Bus Platform was the mark of the union of the metropolis, of the capital, with its satellite cities that were improvised in the peripheries. It is a forced point in which all the population that lives outside encounters the city […] They are right, I was the one that was wrong. They took over that which was not conceived for them.(Canez and Segawa 2010, translation mine)

The workers that Costa watch and celebrates here converge on the city through its central bus station reproducing daily the violence that has denied them a right to the city of Brasília. Just like the workers that built this modernist feat were pushed to the unplanned and impoverished peripheries in the late 1950s, their descendants repeat every day this process of exclusion as they enter the promised modernity that is Brasília’s pilot plan, clean it, tame the hinterlands’ relentless red earth and overwhelming sun, and then leave, returning to the homes that just like many across the nation—as Lopes’ Construção Brasileira highlights—share in the same desire to own modernity and the future it promises.

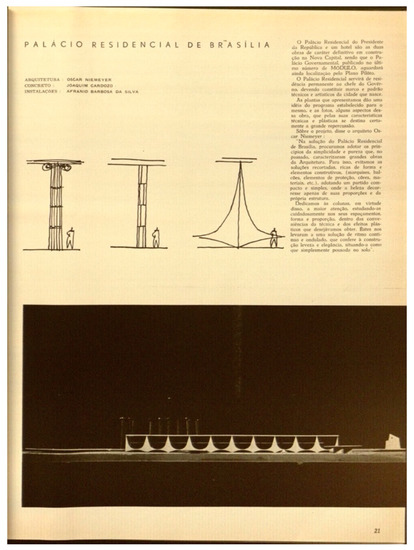

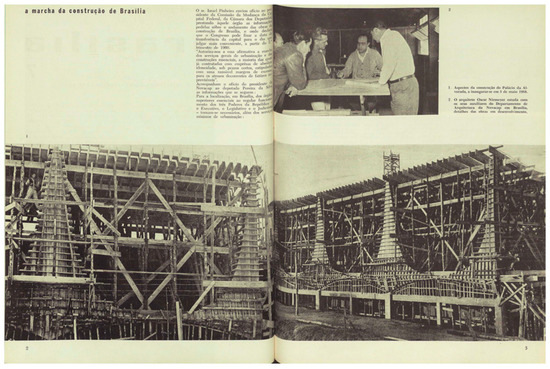

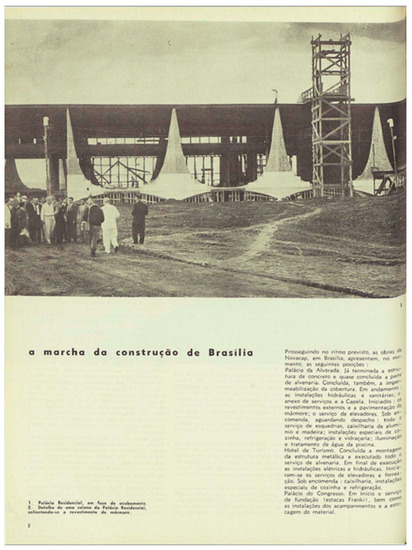

What Lopes and Myrrha’s works make starkly clear is that the parabolic columns of Brasília are undeniably the city’s most iconic form, but also that their symbolic capital has been mined repeatedly throughout the years. During the construction of the city, they were observed closely as these columns were imagined (Figure 9), molded (Figure 10), and lined with marble (Figure 11). The protagonism of the column in the visuality of Brasília was exposed especially as they went through the process of construction—from idea to tectonics—because while the promenade of columns of the governmental palaces quickly became fully formed, the buildings behind them remained only skeletons. The complexity of the Alvorada column’s materiality—its geometry, the engineering and design innovations it represented, as well as the subtle luminosity of the white Italian marble that dressed it—were amply publicized throughout the 1950s. Images of the columns were recurrent especially in magazines like Módulo—which having Niemeyer as its founder and director was often a mouthpiece of the architect—and NOVACAP’s Revista Brasília that focused on widely disseminating the image of the city. The Palácio da Alvorada was the first governmental building to be erected in Brasília—aside from the temporary presidential house, known as Catetinho—and was the first permanent building to be inaugurated in the city (Fraser 2000). Thus, as made evident by the proliferation of images of the columns, as drawings, models, and photographs, Niemeyer saw the parabolic columns as the guiding force behind Brasília’s architectural program. However, he had a very clear vision of it, which the much less manicured Revista Brasília and the NOVACAP archive of photographs cannot help but challenge.

Figure 9.

Article published in Módulo, vol. 3, n. 8, February 1957, p. 21 with drawing by Oscar Niemeyer and architectural model of the Palácio da Alvorada, courtesy of Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal.

Figure 10.

Column “A Marcha da Construção de Brasília,” Revista Brasília, ano 1, n. 7, 1957, courtesy of Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal.

Figure 11.

Column “A Marcha da Construção de Brasília, Revista Brasília, Ano 1, n. 10, 1957, courtesy of Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal.

In buildings like the Palácio da Alvorada, the columns were objects for the circulation of Brasília’s symbolic capital, but they did not need material depth to do that, only surface. The Alvorada colonnade worked as a screen that, rather than covering, brought the forms forward, orienting the way the buildings registered in an audience’s mind’s eye. Against this backdrop, the association of the Palácio da Alvorada and the Colubandê Plantation house in Myrrha’s work is further strengthened, not by a relation of causality or direct influence, but by the continuity of its power structures. The veranda of the master house in the São Gonçalo plantation, like Brasília’s promenade of columns, hid relations of power, the barred windows at the basement level of Colubandê showing where captive enslaved peoples were once kept, while the Alvorada colonnades efface the bodies of the workers that meld with the architecture in representations of the city. Works such as Myrrha’s Case Study formally call attention to these power relations by making the physical support of Niemeyer’s column dependent on the Colubandê column—exemplary of the role played by the organization of space in the plantations (Fonseca 2019).

5. Studies on a Fiction of Modernity

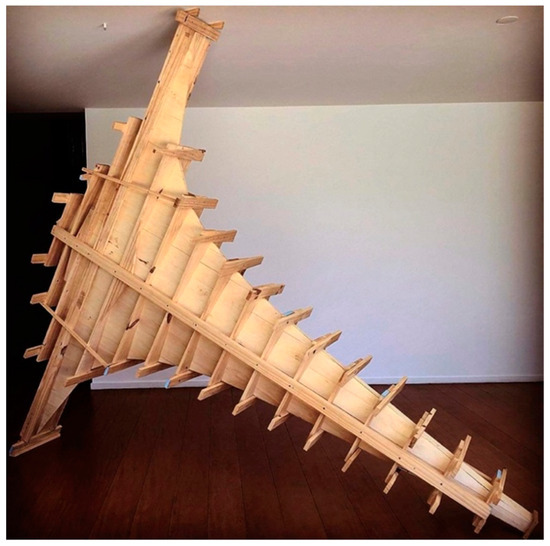

While in Case Study, Myrrha uses gesso reproductions of the Alvorada and the Colubandê columns to frame the sculptures in the installations as studies in the manner traditional of 19th-century art schools, arguing that this precarious balance relates to the fragility of Brazil’s project of modernity in that it is built on extremely conservative pillars. Study for a Constructed Future (Figure 12) further points to the interconnected process of effacement that took place during the construction of Brasília: the one of labor. The artist’s installation was designed through a type of reverse engineering, where archival photographs of the construction of Brasília results in a life-size wood reproduction of the exoskeleton of Niemeyer’s parabolic columns (Myrrha 2018). Myrrha argues that the work is simultaneously a mold, the project of a mold, and a model:

Figure 12.

Lais Myrrha, Estudo para um Futuro Construído [Study for a Constructed Future], 2018, installation at Galeria Auroras.

… the maquette that is the model, is something that is projecting to the future, and because of that the form already exists, it is present in the future. It is a project and a mold of something that already exists, but it does not exist, because it is in this strange scale [it is either consumed by the poured concrete or destroyed after the process], so it is as if all these timeframes—the past, present, and future—were jumbled up.(Myrrha 2018, translation mine)

The Alvorada column in Myrrha’s Study for a Constructed Future is a mold that angles the understanding of Brasília and its history, as well as one that silenced the ecologies of the central plateau, an entire world that does not exist anymore: a permanently lost mode of being in that place.

Myrrha also proposes that a parallel process takes place during the drawing and planning of the column by Niemeyer and the labor of the workers who modeled, planned to mold, and designed the mold that forms each of the columns that populate the city of Brasília. By establishing this connection, the artist points—knowingly or not—to another process of forming: in this case, how the design of the parabolic columns of Brasília populated the national imagery to become models—and molds—for modernity. Thus, the desire to possess and conquer modernity—and the future attached to it—became embedded in this form, giving it currency. The parabolic column as symbolic form, and the repetition of this form throughout the process of constructing the city and after—still holding substantial iconic currency today—exposes how much traction the fiction of modernity still has within Brazilian society today. As such, the parabolic column of Brasília—in its circulation, repetition, and dissemination—gave form (material and iconic form) to modernity within the Brazilian imaginary.

Myrrha’s tipped-over columns and her choices of a gesso sculpture balanced on the reproduction of the Colubandê column in Case Study and the wooden mold—a model and projected future column—in Study for a Constructed Future, therefore, posit a few questions about this form. Niemeyer’s Alvorada column is one of the elements in modern Brazilian architecture that most clearly engenders the naturalization of modernity by erasing the exploitation of labor needed to build them: they are, in most ways, perfect commodities and thus give the reassurance of a dominated landscape. This erasure—the abstraction—of labor from forms such as the Alvorada column is not a discursive mechanism or even a visual one; instead, it is one embedded in the process of construction, which condenses at the surface of the built wall. In the photographs of the Palácio da Alvorada, the white parabolas become the only form defining the structure, its essence determined by the luminosity of its surface and the way it pushes forward, obscuring its backdrop. In most images of the governmental buildings in Brasília, whatever lies behind the colonnade surface, namely the bodies of the workers that migrated from all over Brazil and physically built the new city—as well as those that manicure it today—are effaced. They are firstly dwarfed by the gigantic proportions of the column as framed by photography, and secondly, they are further atomized by the way the construction engulfs them (Figure 13). Thus, most of the images of Brasília erase the fact that the weightlessness and purity of form of Niemeyer’s architecture is the result of the intensive labor of lower-class mixed-race workers, who migrated to the central plateau in the late 1950s and were violently exploited during the miraculous feat of building a city in three and a half years. Embodied by the workers that built Brasília and their descendants, the present-day brasilienses, who traverse the city every day while remaining alienated from it, is the continuing colonial legacy that underlines Brazil as a nation.

Figure 13.

Photograph from the construction of Brasília, NOVACAP archive at Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal, c. 1957–8.

6. Closing Remarks

The daily rituals that take place in Brasília: the constant cleaning of the white marble surfaces, the large windowpanes, and the walls of Niemeyer’s buildings, the repainting of the city’s façades, and the careful tending of the lawns and landscapes in order to preserve the original plan of the city are nevertheless completely erased from the imagery of the city. This contemporary erasure is a continuation of the violent process of razing the central plateau, displacing the population that lived there, and constructing a city to be the “doorway to modernity.” The building and enduring manicuring of Brasília into the dreamscape of Brazilian modernity is, in the end, ultimately about labor and power. The daily convergence of a labor force that works to maintain this ideal city in a constant reproduction of the structures of power that are foundational to the ideals of modernist architecture and Brazil as a nation is a synecdoche of the larger relations of coloniality that underline Brazilian society.

Today, Brasília is at once frozen as a mirage of the desires of a Brazilian elite that has grown angry and hateful of the very utopian ideals the city represents; and decaying before one’s eyes, as the coloniality that figures like Costa and Freyre sought to reconcile with the fiction of modernity is what the mob that invaded the capital’s Praça dos Três Poderes [Three Powers Square] on January 8 fights vigorously to maintain. Perhaps unsurprising are the images that have emerged from the invasion of the governmental buildings in Brasília: as people forced their way into the structures, ransacking the interiors, breaking furniture, installations, and artworks, Niemeyer’s columns stood unscathed; while mottos were spraypainted across the shattered windows and the chaos spilled out from the Palácio do Planalto [The Palace of the Plateau, seat of the executive branch of the Brazilian government] and the Supremo Tribunal da Justiça [Supreme Justice building], the white marble columns that line these buildings remained imposing and untouched. That and the fact that the assault was planned for a Sunday, the day Brasília sees the least influx of workers from across its satellite cities, says more about the roots of the current crisis of the Brazilian collective than most descriptions of the events of January 8 could. The aestheticizing of Brasília’s image as modern, originally Brazilian, and representative of the country’s path to progress make the city an unavoidable symbol of the desire for modernity, while its organization of space, effacement of violence, and suppression of those that built and maintain this dreamscape are reminders of the coloniality that is incised into the very substrate of the city and into the earth of the Brazilian backlands. Lopes and Myrrha’s works highlight that these foundations—Brazil’s colonial matrix of power—are at once fragile and resilient, desired and repulsive, spread around the entire country’s built landscape and delicately balanced atop one another.

Funding

This research was funded by the Alessandra Comini International Fellowship for Art History Studies from the Department of Art History at Southern Methodist University.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data is available due to copyright restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Lais Myrrha was born in Belo Horizonte and now lives and works in São Paulo. She earned her MA and PhD in Visual Arts at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. She has participated in important international group shows such as 13th Bienal de La Habana: La construcción de lo possible (Havana, Cuba, 2019); 12th Bienal de Gwangju: Bordas Imaginadas (Gwangju, South Korea, 2018); 32º Bienal Internacional de São Paulo (São Paulo, Brazil, 2016), among others. Her recent solo exhibitions include: Cálculo das diferenças (Galeria Athena—Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017); Reparation of Damages (Broadway 1602—New York, U.S.A., 2017); Corpo de Prova (Sesc Bom Retiro—São Paulo, Brazil, 2017); O instante interminável (Galeria Jaqueline Martins—São Paulo, Brazil, 2016); and Projeto Gameleira 1971 (Pivô—São Paulo, Brazil, 2014). See: https://galeriaathena.com/en/artists/39-lais-myrrha/, accessed on 12 January 2023. |

| 2 | Despite the importance of Freyre’s argument for the study of modern Brazilian society in which colonial relations come forth as the foundation of the nation, many scholars have since noted the many blind spots of the study that forwards the ideal of racial democracy while obscuring the racial and sexual violence it is predicated on. See: (Skidmore 1974; Prado 1977; Schwarcz 1999). |

| 3 | A handful of scholars have commented recently on the impact of Bolsonaro’s election on a wider national discourse. For examples, see: (Viveiro de Castro 2019; Mollard 2019). Nevertheless, Franco Berardi (2019) argues in his study that the end of futurity as a utopian narrative is a wider phenomenon. It particularly affects Brazil because of how embedded it is in its national narrative. |

| 4 | Brasília was always a space of contention within Brazil, whether politically or culturally, and it was critiqued as much as it was celebrated. Early writings by figures such as Mário Pedrosa, J. Claúdio Gomes, and Gilberto Freyre speak to this ambiguity. See the anthology by Xavier and Katinsky (2012). |

| 5 | For more on the impact of the thought of Aníbal Quíjano on a generation of thinkers and the contemporary decolonial propositions that are grounded in his formulations about Eurocentrism, capitalism, racism, and sexism, see: (Mignolo and Walsh 2018). |

| 6 | Talles Lopes was born in São Paulo and lives in Anápolis in the inland state of Goiás near the Distrito Federal and the city of Brasília. He graduated from the Universidade Estadual de Goiás. Lopes has participated in shows such as the 12th International Biennale of Architecture of São Paulo at CCSP—Centro Cultural São Paulo (2019), the exhibition “Brazilian Histories” (2022) at MASP—Museu de Arte de São Paulo, as well as the show “Concretos” (2022) at TEA—Tenerife Espacio de las Artes (Spain). More recently, she was the resident artist at the studio El Despacho in Tenerife (2021) and the Delfina Foundation in London (2022). See: https://talleslopes.cargo.site/, accessed on 31 January 2023. |

| 7 | Talles Lopes Construção Brasileira installation was shown at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás (2018), the 12th São Paulo Bienal de Arquitetura in 2019, and more recently (2022) part of the group show Contar o Tempo at Centro Cultural Mari Antonia (São Paulo, Brazil). Especially in Contar o Tempo, Lopes engages an array of vehicles for the dissemination of Brazil’s ideal of futurity and fiction of modernity, including Brasília, MoMA’s Brazil Builds, but also the Brazilian Pavillion at the 1958 Brussels international exhibition that engaged the notion of the tropical modernity coming into being in the country in the mid-century (Cabral 2022). For more on the exhibitions, see: (Fonseca 2018; Lopes 2019; Nunes 2022a; Cabral 2022; Vallé Vílchez 2022). |

| 8 | Referring to the International Style of architecture, which was associated with prominent architects of the period, such as Le Corbusier and Mies Van der Rohe. For more on these debates, see: (Quezado Deckker 2001). |

| 9 | Estudo de Caso was commissioned by Clara Kim for the “ Modern Utopias” section of the 12th Gwanju Biennale in 2018, together with the work of 26 other artists, photographers, and filmmakers. For more on the 12th Gwanju Biennale, see: (Moldan 2018; Chung 2018; Kim and Chung 2018; Zion 2018). |

References

- Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. 2019. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, Franco. 2019. Depois Do Futuro. Translated by Regina Silva. São Paulo: Editora Ubu. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, Leslie. 2002. Brasil, Fardo Do Passado, Promessa Do Futuro: Dez Ensaios Sobre Política E Sociedade Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. [Google Scholar]

- Brittan Trindade, Jaelson. 2013. Luís Saia, Arquiteto (1911–1975): A Descoberta, Estudo e Restauro das ‘Moradas Paulistas. Risco: Revista de Pesquisa em Arquitetura e Urbanismo 18–19: 123–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bruand, Yves. 1997. Arquitetura Contemporânea No Brasil, 3rd ed. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. [Google Scholar]

- Buarque, Daniel. 2013. Brazil Um País Do Presente: A Imagem Internacional Do “País Do Futuro”. São Paulo: Alameda. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, Charlene. 2022. Contar o Tempo. São Paulo: Museu da Universidade de São Paulo. [Google Scholar]

- Canez, Anna Paula, and Hugo Segawa. 2010. Brasília: Utopia Que Lúcio Costa Inventou. Arquitextos. 11, n. 125.00, Vitruvius, October. Available online: https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/10.125/3629 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Cardoso, Joaquim. 1943. Um tipo de casa rural do Distrito Federal e Estado do Rio. Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, Lauro. 2006. Moderno E Brasileiro: A História De Uma Nova Linguagem Na Arquitectura (1930–1960). Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Hayoung. 2018. Curators Strive to Transcend National Borders at the Gwangju Biennale. Hyperallergic, October 12. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/464235/imagined-borders-gwangju-biennale-2018/(accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Conduru, Roberto. 2008. Araras Gregas. 19&20 III. Available online: http://www.dezenovevinte.net/arte%20decorativa/ad_conduru.htm (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Correa, Felipe. 2016. Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Eduardo Augusto. 2009. ‘Brazil Builds’ e a construção de um modern, na arquitetura Brasileira. Master Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Lúcio. 1937. Documentação Necessária. Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional 1: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, José Murilo. 1995. Brasil: Nações Imaginadas. Antropolítica 1: 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, José Murilo. 2012. The Formation of Souls: Imagery of the Republic in Brazil. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Jarcy, Xavier. 2015. Le Corbusier, un fascisme français. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, Ricardo Luiz. 2008. Identidade Nacional, Raça E Autoritarismo: A Revolução De 1930eE a Interpretação Do Brasil. São Paulo: LCTE Editora. [Google Scholar]

- El-Dahdah, Farès. 2006. Lucio Costa Preservationist. Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 3: 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- El-Dahdah, Farès. 2010. Brasília, Um Objetivo Certa Vez Adiado. Arquitextos 10. Available online: https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/10.119/3363 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Esther, Carmen. 1964. Entrevista a Oscar Niemeyer y Juscelino Kubitschek en el cuarto aniversario de Brasília. Radio Barcelona, recording from the Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira Santos, Paulo. 1986. Interação de passado e presente no processo histórico da Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Arquitetura Revista 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, Raphael. 2018. Um Corpo no Ar Pronto para Fazer Barulho. Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Goiás and Fundação Oscar Niemeyer, exhibition catalogue. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, Raphael. 2019. Vaivém [to-and-Fro]. Edited by Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. São Paulo: Conceito. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Valerie. 2000. Building the New World—Studies in the Modern Architecture of Latin America 1930–1960. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Freyre, Gilberto, and Samuel Putnam. 1956. The Masters and the Slaves (Casa-Grande & Senzala): A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization. New York: Knopf. First published 1933. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Gisbourne, Mark. 2010. Fotografia e Brasília-Pós-Reticência e Remorso. In Arquivo Brasília. Edited by Michael Wesely and Lina Kim. São Paulo: Cosac Naify. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Philip Lippincott, G. E. Kidder Smith, and Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.). 1943. Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old, 1652–1942. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, Henry Russell, and Philip Johnson. 1996. The International Style. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Hochman, Elaine. 1979. Confrontation: 1933 Mies van der Rohe and the Third Reich. Oppositions 18: 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Holston, James. 2009. The Spirit of Brasília: Modernity as Experiment and Risk. In City/Art: The Urban Scene in Latin America. Edited by Rebecca E. Biron. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karasch, Mary C. 2016. Before Brasília: Frontier Life in Central Brazil. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Clara, and Yeon Shim Chung. 2018. Preview of 2018 Biennales:Conversation 3 Gwangju Biennale Curators. The Artro: Platform for Contemproary Korean Art, August 14. Available online: https://www.theartro.kr/eng/features/features_view.asp?idx=1734&b_code=10(accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Kim, Clara. 2018. Condemned to Be Modern. Edited by Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles: Deparment of Cultural Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, Fernando Luiz, and Stella Nair. 2007. Brazilianization or the First Fifty Years. The Journal of the International Institute 14. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.4750978.0014.214 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Lara, Fernando Luiz. 2008. The Rise of Popular Modernist Architecture in Brazil. Florida: University Press of Florida Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, Fernando Luiz. 2018. Excepcionalidade Do Modernismo Brasileiro. São Paulo: Romano Guerra. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, Fernando Luiz. 2019. A stitch in time: The legacy of colonialism in the Americas. Architectural Review, October 18. Available online: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/a-stitch-in-time-the-legacy-of-colonialism-in-the-americas(accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Le Blanc, Aleca. 2009. Building the Tropical World of Tomorrow: The Construction of Brasilidade at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Hemisphere: Visual Cultures of the Americas 2: 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, Talles. 2019. Talles Lopes: 12th International Architecture Biennale of São Paulo. Todo Dia/Everyday, Dia a Dia 5. March 11, exhibition catalogue. [Google Scholar]

- Lopéz-Durán, Fabíola. 2018. Eugenics in the Garden: Transatlantic Architecture and the Crafting of Modernity. Lateral Exchanges: Architecture, Urban Development, and Transnational Practices. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madaleno, Isabel Maria. 1996. Brasília: The Frontier Capital. Cities 13: 273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammí, Lorenzo. 2012. O Que Resta: Arte E Crítica De Arte, 161–70. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter, and Catherine E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mindlín, Henrique E., and Sigfried Giedion. 1956. Modern Architecture in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Colibris. [Google Scholar]

- Moldan, Tessa. 2018. Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders. Ocula Magazine, September 20. Available online: https://ocula.com/magazine/features/imagined-borders-at-the-12th-gwangju-biennale/(accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Mollard, Manon. 2019. Troubles in Paradise. The Architectural Review, Special issue on Brazil, No. 1465. October 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Munanga, Kabengele. 2004. Rediscutindo a mestiçagem no Brasil: Identidade nacional versus identidade Negra. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica. [Google Scholar]

- Myrrha, Lais. 2018. Interview on the Occasion of an Exhibition Featuring Myrrha’s Installation Entitled Estudo Para Um Futuro Construído. By Ilêz Sartuzi. Auroras Gallery, December 22. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFw1YLJfKu8(accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Nunes, Matheus. 2022a. Brazil Builds and the Possibility of a Tropical Modernism. Originally Published in Select Magazine, July 12. Available online: https://talleslopes.cargo.site/Mateus-Nunes(accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Nunes, Rodrigo. 2022b. Do Transe À Vertigem—Ensaios Sobre Bolsonarismo E Um Mundo Em Transição. São Paulo: Editora Ubu. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, Caio, Jr. 1977. Formação Do Brasil Contemporâneo. São Paulo: Brasiliense. [Google Scholar]

- Quezado Deckker, Zilah. 2001. Brazil Built: The Architecture of the Modern Movement in Brazil. London: Spon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quíjano, Aníbal. 1992. Colonialidad y modernidad/racionalidad. Perú Indígena 13: 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Quíjano, Aníbal, and Michael Ennis. 2000. Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1: 533–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, Enio. 2001. Chega De Ser O “País Do Futuro”: Novos Paradigmas Para Resolver O Brasil. São Paulo: Mescla Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Claire. 2014. Art, Urbanism, Modernism, Power… How the Successes and Failure, Myths and Realities of Brazilian Urbanism Have Come to Shape. The Discourse of So Much of Its Contemporary Art. ArtReview, 98–103. Available online: https://artreview.com/september-2014-art-urbanism-modernism/ (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Sader, Emir, and Marco Aurélio Garcia. 2010. Brasil, Entre O Passado E O Futuro. São Paulo: Editora Fundação Perseu Abramo, Boitempo Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. 1999. The Spectacle of the Races: Scientists, Institutions, and the Race Question in Brazil, 1870–1930. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Scottá, Luciane. 2018. Brazil Builds: Releitura Crítica. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore, Thomas E. 1974. Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Paulo. 2020. Brasília: Colonial Capital. E-Flux Architecture. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/the-settler-colonial-present/351834/braslia-colonial-capital/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Tavares, Paulo. 2022a. Lúcio Costa Era Racista: Notas Sobre Raça e Colonialismo e a Arquiteura Moderna Brasileira. São Paulo: Editora Ubu. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Paulo. 2022b. The Colonial-Modern Politics of Desertification. In Deserts Are Not Empty. Edited by Samia Henni. New York: Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Vallé Vílchez, Laura. 2022. Regimes of Representation: Interrogation and Subversion. London: Delfina Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, Laurent. 2009. De Nova Lisboa a Brasília: A Invenção De Uma Capital (Séculos XIX–XX). Translated by Florence Marie Dravet. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiro de Castro, Eduardo. 2019. Brasil, País Do Futuro Do Pretérito. Aula Inaugural do CTCH, PUC-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, March 14. Available online: https://laboratoriodesensibilidades.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/brasil_pais_do_futuro_do_preterito.pdf(accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Williams, Daryle. 2001. Culture Wars in Brazil: The First Vargas Regime, 1930–1945. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, Alberto, and Júlio Roberto Katinsky. 2012. Brasília: Antologia Crítica. Coleção Face Norte. São Paulo: Cosac Naify. [Google Scholar]

- Zion, Amy. 2018. 12th Gwangju Biennale, “Imagined Borders.”. E-Flux Criticism, October 19. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/242061/12th-gwangju-biennale-imagined-borders(accessed on 20 March 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).