“Small Is Viable”: The Arts, Ecology, and Development in Peru

Abstract

Man is small, and, therefore, small is beautiful.E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful

In Peru “small is beautiful” should be primarily understood as “small is viable.”

Gustavo Buntinx, “Communities of Sense/Communities of Sentiment”

1. Lima en un árbol (1981)

2. A Diasporic Tree

3. E. F. Schumacher Travels to Peru

The fate of Schumacher’s proposals was ultimately thwarted by Belaúnde’s simultaneous courting of aid through the US-led Alliance for Progress, a massive development program designed to counter the appeal of the Cuban Revolution among Latin American societies. The Alliance supported initiatives favorable to foreign investors, in contrast to Schumacher’s prioritization of regional self-sufficiency. Belaúnde’s intention to expand public welfare programs and infrastructural improvements throughout the country—“picos y palas para una revolución sin balas” (picks and shovels for a revolution without bullets)—foundered on his administration’s entanglement with the foreign-owned International Petroleum Company, an affiliate of the US-based Standard Oil Company (Cotler 1978, p. 344). As a condition for receiving Alliance for Progress aid, the US pressured Belaúnde to resolve disputes over oil field leases in favor of the company. Scandal erupted over the public revelation of the terms that Belaúnde had offered, and the ensuing political crisis precipitated the military coup that brought Velasco to power.17 Having lost his Peruvian laboratory, Schumacher moved on to other consultancies,18 while the military government implemented import substitution industrialization and enacted dramatic agrarian reforms aimed at rectifying social inequalities.He had had his share of ridicule from the economists in Lima, who could only see the advantages of modern economies of scale in factory production and failed to grasp that the detrimental effects the cheap goods had on the rest of the primitive economy eventually destroyed their market. He was delighted that this time the man who really mattered [Belaúnde] was taking him seriously. Unfortunately, a coup not long afterwards ended any immediate hope of intermediate technology in Peru, but Fritz [Schumacher] retained a lifelong affection for President Belaúnde.

Schumacher’s glib references to people becoming “footloose” are nothing if not ironic in light of the author’s emigration from Germany to England in 1936. His impressions elide recognition of the complex factors that impel people to migrate, while also denying migrants knowledge and agency to make decisions on their own behalf. Though the local and small are privileged categories in Schumacher’s thinking, Small Is Beautiful turns Peru into an engine of generalizable conditions. Two decades later, however, Gustavo Buntinx would return Schumacher’s titular phrase to its Peruvian context and imbue it with the texture of everyday life.As an illustration, let me take the case of Peru. The capital city, Lima, situated on the Pacific Coast, had a population of 175,000 in the early 1920s, just 50 years ago. Its population is now approaching three million. The once beautiful Spanish city is now infested by slums, surrounded by misery belts that are crawling up the Andes. But this is not all. People are arriving from the rural areas at the rate of a thousand a day–and nobody knows what to do with them. The social or psychological structure of life in the hinterland has collapsed; people have become footloose and arrive in the capital city at the rate of a thousand a day to squat on some empty land, against the police to come to beat them out, to build their mud hovels and look for a job. And nobody knows what to do about them. Nobody knows how to stop the drift.

4. The Afterlives of Intermediate Technology

5. The Micromuseo: “Small Is Viable”

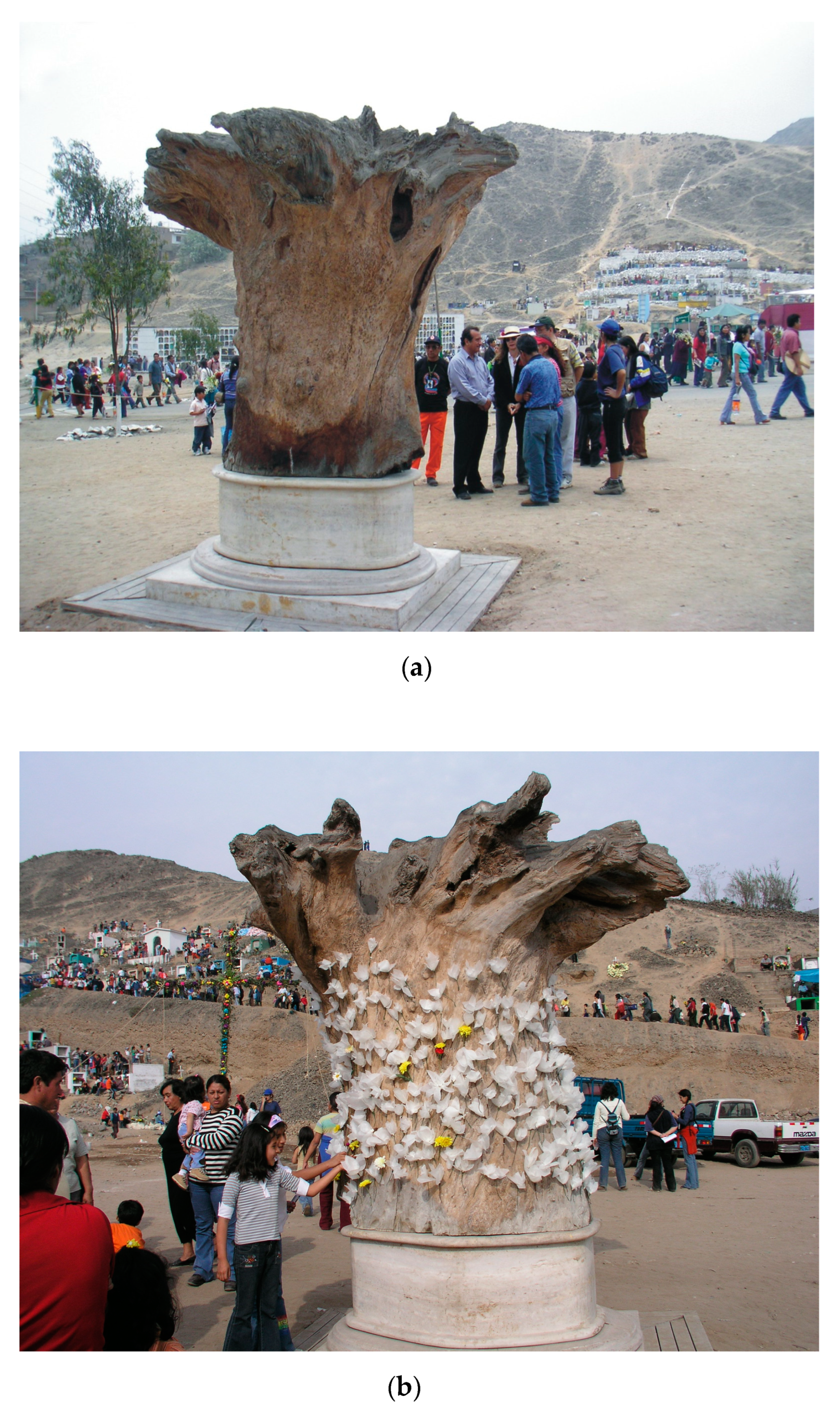

6. Carmen Reátegui, Árbol (2002–2008)

Each of these transformation-oriented sentences builds a bridge across distinct social domains. Reátegui’s final sentence affirms that the tree’s polysemic qualities have the potential to generate new ways of conceptualizing the relationship between life and death, as well as that between human and nature. As “citizens” interact ritually with Árbol de la vida, they engage in a collective act of world-making and, together, form “a living sculpture” that includes themselves, the tree, and their surroundings. In a critical essay about this work, Víctor Vich explores the idea that Reátegui’s incorporation of popular religiosity in her installation facilitates understanding the tree’s death as an act of sacrificial violence resulting from human barbarism. By exhibiting the mutilated stump in settings where rituals around death and remembrance are already being enacted, the tree enters the image repertoire of vernacular Catholicism and enlists spirituality in condemning the human instrumentalization of nature. Vich summarizes the broader implications of this positioning as a call for the protection of other vulnerable trees: “[P]odemos decir que este árbol no parece ser solo un árbol; es también un signo de toda una maquinaria extractiva que en el Perú continúa desarrollándose sin marcos normativos adecuados” (We can say that this tree does not appear to be only a tree; it is also a sign of an entire extractive machinery that is developing in Peru without adequate normative frameworks) (Vich 2022, p. 47). Today, this connection is all the more urgent, as unregulated harvesting of timber from Peruvian forests by foreign-owned corporations has become a significant economic sector. The comparatively small scale of Árbol contrasts with the immense loss perpetuated by extractivist economies. At the same time, Árbol’s exhibitionary affordances--its elevation and theatre of the round presentation--inspire awe, reverence, and respect on the part of people in proximity to the installation.El árbol se carga de significado al momento en que el ciudadano impone su mano. Se comienzan a llenar espacios simbólicos en el sentir popular. La acción se convierte en un ritual, en el que van tomando parte los ciudadanos. El muñón del árbol, el pueblo quebrantado, se va transformando en una escultura viva. (The tree is charged with meaning the moment that the citizen places their hand on it. Symbolic spaces begin to fill within popular sentiment. The action becomes a ritual, in which citizens take part. The tree stump, the broken people, are transformed into a living sculpture.)

7. Conclusions: “Will Someone Try and Visualize Peru in A.D. 2000?”

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | (Agois et al. 1981a, 1981b) Lima en un árbol (11:45) is accessible on YouTube in two parts: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNeJghO6PCE (part 1); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHUPqv4Ks1c&t=6s (part 2) (accessed on 20 September 2022). The video was edited by El Centro de Teleducación de la Universidad Católica del Perú (CETUC) and included in the Propuestas II exhibition organized by the Museo de Arte Italiano de Lima in 1981. In addition to the four participants who appear in the video, Carmen Rosa Martínez also assisted with the action. In 2002, the video was recovered and restored by Alta Tecnología Andina (ATA) and the Micromuseo for a public discussion held on Earth Day at the Centro Cultural de San Marcos. Two decades later, Gustavo Buntinx included Lima en un árbol in his documentary history of the Lima-based arts collective E.P.S. Huayco, which was also established in 1980; the artists’ dates come from this source. Among the participants in Lima en un árbol, Armando Williams also participated in Huayco’s public events and projects involving urban visual culture (Buntinx 2005, p. 44; Buntinx 2013; Lerner Rizo-Patrón and Villacorta Chávez 2008, p. 152; Ludeña 1982; Salazar 1983). All translations in this article are the author’s unless otherwise noted. |

| 2 | See Salazar regarding the use of mass media and technology in Peruvian non-objective art movements (Salazar 1983, p. 115). |

| 3 | The intertitles read as follows: LIMA ES UNA CIUDAD ESPECULATIVA DE 5 MILLIONES DE HABITANTES/LAS DEMANDAS DEL CAPITAL GOBIERNAN Y SIGNAN NUESTRA CIUDAD/LIMA ACUSA DESAPARICIÓN DE AREAS VERDES/COMPORTAMIENTOS COLECTIVOS SOCIALMENTE PROGRAMADOS Y ALIENANTES/ESTA ACCIÓN PROPONE CONFRONTAR LA RELACIÓN NATURALEZA-ARTIFICIO/TRANSGREDIR LA RUTINA DE LA PROGRAMACION URBANA, FELIZ DEMOCRATICA E INMANENTE (Lima is a speculative city of five million inhabitants/The demands of capital govern and shape our city/Lima accuses the disappearance of green space/Alienating and socially programmed collective behaviors/This action proposes confronting the nature–artifice relation/Transgressing the routine of happy, democratic, and immanent urban programming). |

| 4 | In the second iteration, the image quality of this scene appears to be deliberately degraded. |

| 5 | Agois, Ludeña, and Salazar had backgrounds in architecture, while Williams was an artist (Castrillón Vizcarra 1985, p. 28; Buntinx 2005, p. 42). On the intersection of ecology and systems theory in US- and Latin America-based conceptualisms, I draw on studies by (Benezra 2020), (Nisbet 2014), and (Shtromberg 2016). Nisbet offers a useful definition of ecology that is relevant for the present discussion: “By ‘ecology,’ I refer not only to concerns about pollution, resource management, and earthcare in general, but also to how information travels and coheres into historical explanation” (Nisbet 2014, p. 2). |

| 6 | See note 3. |

| 7 | (Luzar 2007, pp. 86, 89). A huayno is a popular form of Andean music and dance; for examples of the eucalyptus theme in Quechua and Spanish, see the cusqueño standard “Eucaliptucha” and “Viejo eucalipto” by the Lima-based musician Walter Humala Lema. |

| 8 | Luzar’s informants observe, for example, that eucalyptus outcompetes other species, consumes water that might be used to support food cultivation, and releases resins into watersheds (Luzar 2007, p. 86). |

| 9 | According to Ponce de León, “plants tend to be narrated in neutral collective terms such as forests, landscapes, crops, or agriculture, signalling how their existence matters culturally in relation to human use and consumption” (Ponce de León 2022, p. 130). For more on “plant-blindness” see (Gagliano et al. 2017); on colonialism and the instrumentalization of nature, see (Ghosh 2021). |

| 10 | (Lerner Rizo-Patrón and Villacorta Chávez 2008, p. 160). The potential of the tree to disrupt both the colonial city and the modernist grid are suggested in this action (Rama 1984). |

| 11 | The first quote is from (DeLoughrey 2019, p. 4), and the second from (Hoyos 2019, p. 3). I am grateful to Gisela Heffes (Heffes 2022) for her valuable exploration of these two critics’ work from a Latin American studies perspective. |

| 12 | The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development, created in 1983, is known as the Brundtland Commission after its first chairperson, Norwegian politician Gro Harlem Brundtland. In 1987, the Commission released an influential report titled Our Common Future, which defined “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Throsby 2001, p. 53; World Commission on Environment and Development 1987, p. 43). |

| 13 | “What the map cuts up, the story cuts across” (de Certeau 1984, p. 129). |

| 14 | E. F. (Ernst Friedrich) “Fritz” Schumacher was born in Germany and attended Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. He relocated permanently to the UK in 1936. The last seven years of Schumacher’s life gave rise to the publications and international lectures for which he is perhaps best known, including the book Small Is Beautiful (Roszak [1973] 2010) and its companion volumes, A Guide for the Perplexed (Schumacher 1977) and the posthumously published Small Is Possible (McRobie 1981). Today, Schumacher’s ideas are recognized in the mission statements of many organizations (Practical Action n.d.). |

| 15 | In Small Is Beautiful, Schumacher remarks in an aside that when he presented a paper on intermediate technology at the Conference on the Application of Science and Technology to the Development of Latin America, organized by UNESCO in Santiago de Chile, he was “treated with ridicule” (Schumacher 2010, p. 180) for his rejection of state-of-the-art methods. The paper in question, adapted as chapter III.2 of Small Is Beautiful, outlines the bases of the Intermediate Technology Development Group. |

| 16 | (Schumacher 1967). The typescript is dated 3.11.1967; based on Schumacher’s archival records, I believe that this refers to 3 November 1967. |

| 17 | (Cotler 1978, pp. 335–83). For more on Peruvian arts in relation to this political crisis, see (Fox 2018). |

| 18 | (Schumacher 1968) and (Schumacher and Porter 1969) develop recommendations about Tanzania and Zambia, respectively, that are similar to ones Schumacher made regarding Peru. |

| 19 | This key chapter is based on a lecture given in London in August 1968 that was later published in the journal Resurgence (Schumacher 2010, p. 320). |

| 20 | (Buntinx 2006, pp. 237, 224). For more about the institution’s name, see (Buntinx 2006, pp. 236–38). |

| 21 | Belaúnde himself was an architect prior to becoming president. |

| 22 | (Primer Encuentro 1986, pp. 8–9). A revised version of Buntinx’s contribution dated 1985–1986 appears in (Micromuseo 2001, pp. 3–7). |

| 23 | The first published source that I have been able to identify in which Buntinx utilizes the phrase “small is beautiful” (in English) is the premier issue of Micromuseo “Al fondo hay sitio” dedicated to the topic of “Museotopías”; the issue includes a previously unpublished text from 1998 titled “‘Al fondo hay sitio’: Rutas para un Micromuseo” (Micromuseo 2001, pp. 11–13). The phrase also appears in (Buntinx 2006) and (Buntinx 2007); see also the Micromuseo website (Micromuseo n.d.). |

| 24 | (Buntinx 2006; Buntinx 2007). Buntinx renders the phrase in English in his Spanish-language writings. It is interesting that the translation of Schumacher’s book title in Spanish uses “hermoso” (beautiful), but Buntinx favors “bello” in his glosses, perhaps emphasizing the latter’s resonance as a marker of elite taste. |

| 25 | I am improvising on Bertolt Brecht’s aphorism. |

| 26 | Schumacher appears to revise these lines from the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven … /Blessed are they who thirst after justice, for they shall have their fill…/Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the Sons of God” (Catholic Encyclopedia n.d.). And here is Schumacher’s version: “--We are poor, not demigods./--We have plenty to be sorrowful about, and are not emerging into a golden age./--We need a gentle approach, a non-violent spirit, and small is beautiful./--We must concern ourselves with justice and see right prevail./--And all this, only this, can enable us to become peacemakers” (Schumacher 2010, p. 166). |

| 27 | (Schumacher 2010, p. 15). For more on Fuller’s influence on contemporary art, see (Nisbet 2014, pp. 67–128). |

| 28 | Schumacher goes so far as to recommend that urbanizations ideally be capped at 500,000 inhabitants (Schumacher 2010, p. 71). |

| 29 | McKibben’s foreword to the 2010 edition offers a useful historical contextualization of the book’s initial reception in the US. In contrast to Roszak’s 1973 “Introduction,” McKibben does not characterize Small Is Beautiful as an underground or cult classic, but rather as an epiphenomenon marking the mainstreaming of grassroots environmental movements which culminated in environmental legislation passed under the Nixon administration (McKibben 2010, pp. xi–xvi). |

| 30 | |

| 31 | (Buntinx 2006; Buntinx 2022). Buntinx’s elaboration of this term seems to evolve out of his earlier formulations about “popular modernity” (see, e.g., Buntinx 1987). |

| 32 | (Buntinx 2006). The Micromuseo website is an important aspect of its commitment to image circulation. |

| 33 | On recent critical interventions problematizing the long-standing hierarchies of aesthetic value between studio and gallery art and artisanry or “arte popular,” see (Borea 2021); (Dorotinsky 2020); and (Smith 2019). |

| 34 | For references to these intellectuals, see (Buntinx 1987). |

| 35 | Reátegui was aware of Lima en un árbol; however, she describes her work as the “producto de una pulsión ante la insania del agravio” (product of an impulse in the face of the insanity of an [injurious] grievance) (Reátegui 2022). |

| 36 | Gutiérrez was an ally of Fujimori, whose second term in office was marked by an intensification in autocratic neoliberalism. |

| 37 | As I explain below, Reátegui produced two videos about her work: Detente (Reátegui 2002a, 2002b) and Árbol (2002–2008) (Reátegui 2008). I refer to the latter production in this article. Both videos are accessible on YouTube. Detente: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2_o02jPAsLw (part 1) and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JV0H3mKrVGI (part 2). Árbol (2002–2008): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IpToRZuIjoE (accessed on 20 September 2022). |

| 38 | Detentes were traditionally made by Catholic nuns and featured embroidered images of the Sacred Heart and other icons relating to the Passion of Christ. They were carried or worn by the faithful in a manner similar to scapulars. Reátegui recalls detentes being utilized through the 1950s to reinforce the petitions of the devout. She came across some detentes in an antique store and saved them without knowing how she would eventually use them (Reátegui 2022). It is interesting that the detentes which Reátegui supplied for her installation are scaled to the tree’s “body”; that is, they are larger than typical scapulars and used in a manner similar to ex votos. In the video, one can also see some metal milagros affixed to the tree. The fact that Reátegui refers to these objects as “ropaje” (garments) not only suggests the tree’s personhood, but also the resonance of Reátegui’s work with Catholic devotional rituals associated with the exhibition of relics and statuary (Reátegui 2005). |

| 39 | Vich relates that the videographer was a religious fundamentalist who destroyed most of the recording because he objected to the “idolatry” of the project (Vich 2022, p. 44). |

| 40 | According to Reátegui, she was present at the recording, and there were no interview prompts (Reátegui 2022). |

| 41 | For a parallel discussion of Árbol de la vida’s auratic qualities, see (Vich 2022, p. 47). |

| 42 | There are four shots in all. In the first, the tree is “unclothed,” and in each of the subsequent shots, the tree is decorated with the detentes and flowers affixed at each of its exhibitions. |

| 43 | For more information about the cemetery, see (Pérez 2016). Relevant to Reátegui’s exhibition in this location is the work of artist Jaime Miranda Bambarén, who has also created public art using reclaimed trees. Miranda Bambarén’s Monumento en Honor a la Verdad para la Reconciliación y la Esperanza (Monument in Honor of Truth for Reconciliation and Hope), also known as Árbol desarraigado (Uprooted Tree), was inaugurated in Villa María del Triunfo in 2007 and surreptitiously destroyed in 2010 (Miranda Bambarén n.d.; Quijano 2013). |

| 44 | In “La Gesta del Árbol,” a brief narrative about her work, Réategui recalls her reception at the cemetery: “¿Turista? No, artista. ¿A qué [h]a venido? Trayendo un árbol, muy grande, tirado en la calle, sucio, desarraigado” (Tourist? No, artist. Why have you come? Bringing a tree, very big, cast out on the street, dirty, uprooted) (Reátegui 2005). |

| 45 | The scholarship on the expansion of cultural and heritage sites in Peru is extensive. See, for example, (Borea 2021); (Gómez-Barris 2017); (Ramón Joffré 2014); (Rice 2018); and (Silverman 2015). |

References

- Agois, Rossana, Wiley Ludeña, Hugo Salazar del Alcázar, and Armando Williams. 1981a. Lima en un árbol. Video, 11:45 minutes. Part 1. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNeJghO6PCE (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Agois, Rossana, Wiley Ludeña, Hugo Salazar del Alcázar, and Armando Williams. 1981b. Lima en un árbol. Video, 11:45 minutes. Part 2. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHUPqv4Ks1c&t=6s (part 2) (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Benezra, Karen. 2020. Dematerialization: Art and Design in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, Lisa. 2022. Cultivating Ongoingness Through Site-Specific Arts Research and Public Engagement. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 31: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2021. Configuring the New Lima Art Scene: An Anthropological Analysis of Contemporary Art in Latin America. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, Mary Pat. 2017. Territoriality. In Keywords for Latina/o Studies. Edited by Deborah R. Vargas, Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes and Nancy Raquel Mirabal. New York: New York University Press, pp. 224–27. [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 1987. La utopía perdida: Imágenes bajo el segundo belaundismo. Márgenes 1: 52–98. [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 2006. Communities of Sense/Communities of Sentiment: Globalization and the Museum Void in an Extreme Periphery. In Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations. Edited by Ivan Karp, Corinne A. Kratz, Lynn Szwaja and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 219–46. [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 2007. Lo impuro y lo contamindado: Pulsiones (neo)barrocas en las rutas del Micromuseo. Lima: Micromuseo. [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 2013. Interrumpir el Tráfico. Micromuseo Website. Available online: https://micromuseo.org.pe/pieza-del-mes/lima-en-un-arbol/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Buntinx, Gustavo. 2022. Interview with the author, Bar Café La Habana, Lima. [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx, Gustavo, ed. 2005. E.P.S. Huayco: Documentos. Lima: Centro Cultural de España en Lima, IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, Museo de Arte de Lima. [Google Scholar]

- Castrillón Vizcarra, Alfonso. 1985. Reflexiones sobre el arte conceptual en el Perú y sus proyecciones. Letras 48: 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catholic Encyclopedia. n.d. Available online: https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Cotler, Julio. 1978. Clases, Estado y Nación en el Perú. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Stephen Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- de la Cadena, Marisol. 2015. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2019. Allegories of the Anthropocene. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson, Joshua C., III. 1969. The Eucalypt in the Sierra of Southern Peru. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 59: 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorotinsky, Deborah. 2020. Handcraft as Cultural Diplomacy: The 1968 Mexico Cultural Olympics and U.S. Participation in the International Exhibition of Popular Arts. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 29: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Claire F. 2018. The Documentary Films of José Gómez Sicre and the Pan American Union Visual Arts Department. ARTMargins 7: 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, Monica, John C. Ryan, and Patrıcia Vieira, eds. 2017. The Language of Plants: Science, Philosophy, Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Canclini, Néstor. 1990. Culturas Híbridas: Estrategias para Entrar y salir de la Modernidad. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Germana, Gabriela, and Amy Bowman-McElhone. 2016. Vacío museal: Medio Siglo de Museotopías Peruanas (1966–2016), curated by Gustavo Buntinx, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (exhibition review). Journal of Curatorial Studies 5: 411–14. [Google Scholar]

- Germana, Gabriela, and Amy Bowman-McElhone. 2020. Asserting the Vernacular: Contested Musealities and Contemporary Art in Lima, Peru. Arts 9: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Amitav. 2021. The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Barris, Macarena. 2017. The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heffes, Gisela. 2022. Submerged Strata and the Condition of Knowledge in Latin America. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 31: 115–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, Héctor. 2019. Things with a History: Transcultural Materialism and the Literatures of Extraction in Contemporary Latin America. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner Rizo-Patrón, Sharon, and Jorge Villacorta Chávez. 2008. Fragmented Corpus: Actions in Lima 1966–2000. In Arte [No Es] Vida: Actions by Artists of the Americas, 1960–2000. Edited by Deborah Cullen. New York: El Museo del Barrio, pp. 152–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ludeña, Wiley. 1982. Proyectos: Lima en un árbol. U-Tópicos 1: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Luzar, Jeffrey C. 2007. The Political Economy of a ‘Forest Transition’: Eucalyptus Forestry in the Southern Peruvian Andes. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 5: 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibben, Bill. 2010. Foreword to the 2010 Harper Perennial Edition. In Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered. Edited by E. F. (Ernst Friedrich) Schumacher. New York: Harper Perennial, pp. xi–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- McRobie, George. 1981. Small Is Possible. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Micromuseo. 2001. Micromuseo “Al Fondo Hay Sitio,” Special Issue on Museotopías, 1.0 (abril). Available online: https://vadb.org/institutions/micromuseo-al-fondo-hay-sitio (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Micromuseo. n.d. Available online: micromuseo.org.pe (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Miranda Bambarén, Jaime. n.d. Available online: jaimemiranda.com (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Nisbet, James. 2014. Ecologies, Environments, and Energy Systems in Art of the 1960s and 1970s. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Luis. 2016. Villa María del Triunfo: El cementerio de todas las sangres. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161112101126/http://larepublica.pe/turismo/cultural/817501-villa-maria-del-triunfo-el-cementerio-de-todas-las-sangres (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Ponce de León, Alejandro. 2022. Latin America and the Botanical Turn. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 31: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practical Action. n.d. Available online: practicalaction.org (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Primer Encuentro, de Museos Peruanos. 1986. Mimeographed Pamphlet. 39 pp. Biblioteca Manuel Solari Swayne, Museo de Arte de Lima. Available online: https://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla70/papers/127s-Bishofshausen.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Quijano, Rodrigo. 2013. Espacios de Memoria/Espacios de Conflicto. Available online: http://www.jaimemiranda.com/works/monumento-en-honor-a-la-verdad-para-la-reconciliacion-y-la-esperanza (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Rama, Ángel. 1984. La Ciudad Letrada. Hanover: Ediciones del Norte. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón Joffré, Gabriel. 2014. El Neoperuano: Arqueología, Estilo Nacional y Paisaje Urbano en Lima, 1910–1940. Lima: Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima and Sequilao Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Reátegui, Carmen. 2002a. Detente. Video, 12:27 minutes. Part 1. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2_o02jPAsLw (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Reátegui, Carmen. 2002b. Detente. Video, 12:27 minutes. Part 2. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JV0H3mKrVGI (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Reátegui, Carmen. 2005. La Gesta del Árbol. Unpublished text. [Google Scholar]

- Reátegui, Carmen. 2008. Árbol (2002–2008). Video, 7:04 minutes. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IpToRZuIjoE (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Reátegui, Carmen. 2022. Personal email correspondence with the author. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Mark. 2018. Making Machu Picchu: The Politics of Tourism in Twentieth-Century Peru. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ulloa, Olga. 2020. Debris and Poetry: A Critique of Violence and Race in the Peruvian Eighties. Latin American Literary Review 47: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, Theodore. 2010. Introduction. In Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered. Edited by E. F. (Ernst Friedrich) Schumacher. New York: Harper Perennial, pp. 1–10. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar [del Alcázar], Hugo. 1983. Veleidad y demografía en el no-objetualismo peruano. Hueso Húmero (julio-septiembre): 112–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. 1967. “Uninhibited Musings,” Carbon Typescript, 6 pp., Box EFS 1974/1977 US Tours/Manuscripts/Interviews, Folder 2, Schumacher Archives. Great Barrington: Schumacher Center for a New Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. 1968. “Economic Development in Tanzania: A Report,” Box 2, Folder 15: Industry in Rural Areas, Schumacher Archives. Great Barrington: Schumacher Center for a New Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. 1977. A Guide for the Perplexed. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. 2010. Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich, and Julia Porter. 1969. “Rural Development in Zambia,” Box 2, Folder 15: Industry in Rural Areas, Schumacher Archives. Great Barrington: Schumacher Center for a New Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Shtromberg, Elena. 2016. Art Systems: Brazil and the 1970s. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Helaine. 2015. Branding Peru: Cultural Heritage and Popular Culture in the Marketing of PromPeru. In Encounters with Popular Pasts: Cultural Heritage and Popular Culture. Edited by Mike Robinson and Helaine Silverman. Cham: Springer International, pp. 131–48. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Terry. 2019. Art to Come: Histories of Contemporary Art. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David. 2001. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Culture and Sustainable Development. n.d. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/culture-development (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Vich, Víctor. 2022. Secularizar el aura: El árbol de la vida de Carmen Reátegui. Cuadernos de Antropología Social 56: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Barbara. 1984. Alias Papa: A Life of Fritz Schumacher. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fox, C.F. “Small Is Viable”: The Arts, Ecology, and Development in Peru. Arts 2023, 12, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12020061

Fox CF. “Small Is Viable”: The Arts, Ecology, and Development in Peru. Arts. 2023; 12(2):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12020061

Chicago/Turabian StyleFox, Claire F. 2023. "“Small Is Viable”: The Arts, Ecology, and Development in Peru" Arts 12, no. 2: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12020061

APA StyleFox, C. F. (2023). “Small Is Viable”: The Arts, Ecology, and Development in Peru. Arts, 12(2), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12020061