Abstract

Between 1838 and 1917, a British system of indentured servitude replaced the enslavement of African peoples with Indian labor in the Americas and the Caribbean. Almost a quarter of a million indentured Indian laborers came to British Guiana and would form the foundation of the majority of the Indian population in present-day Guyana. These men and women would spend nearly eight decades toiling on sugar plantations and rice fields before the brutal system of labor was abolished. This curatorial essay explores the work of three key contemporary artists of Guyanese heritage—Maya Mackrandilal, Michael Lam, and Suchitra Mattai—who underscore St. Vincent-born poet Derek Walcott’s seminal words “the sea is history” with an exploration of the sea as a weapon of rupture. Collectively, their artworks return us to a British past to offer a visceral reminder of the perilous kālā pānī crossing [Hindi for “black waters”], marking the sea the place where ancestral histories, trauma, and survival all share space. Grounding us in the present and pointing us to a future, I illustrate how these artworks also function as contemporary tools of remembrance and repair.

1. They Came in Ships

- They came in ships

- From far across the seas

- Britain, colonising the East in India

- Transporting her chains from Chota Nagpur and Ganges plain.

- Westwards came the Whitby

- Like the Hesperus

- Alike the island-bound Fatel Rozack.

- Some came with dreams of milk and honey riches.

- Others came, fleeting famine

- And death,

- All alike, they came—

- The dancing girls,

- Rajput soldiers—tall and proud

- Escaping the penalty of their pride.

- The stolen wives—afraid and despondent.

- All alike,

- Crossing dark waters.

- Brahmin and Chamar alike.

- They came

- At least with hope in their heart.

- On the platter of the plantocracy

- They were offered disease and death.

Mahadai Das, 1987

The holiday of Indian Arrival Day is celebrated in Guyana each year on May 5 to commemorate the arrival of the first two British ships, the S.S. Hesperus and S.S. Whitby, that brought Indian indentured laborers to the shores of then British Guiana1. In fact, of its Latin American and Caribbean colonies, the British designated British Guiana to be the first to implement Indian indentureship. From the 19th to the early 20th century, British colonialists propelled indentured servitude as a viable replacement of labor in their colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean, turning to India as their primary workforce. As a result, a mere four years after the barbaric enslavement of African peoples ended in 1834 in the region, the first group—396 Indians—were brought to British Guiana on 5 May 1838. Despite the high costs of recruiting and transporting Indian laborers, the British considered Indians “a cheaper and more controllable source of labor in the longer term than freed Africans” (Persaud 2016). From the Hesperus and Whitby’s first arrival in 1838, through the turn of the 20th century and into 1917, to sustain this brutal system of Indian indentured migrant labor, the British shipped approximately 23,900 men and women from India to the Demerara and Berbice shores of British Guiana. It was a monumental scheme, buoyed by 245 ships traversing the perilous kālā pānī of the Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and Caribbean Sea in over 500 voyages. Each voyage lasted an average of three months for the souls on board. Once they disembarked, these indentured laborers were bound to labor contracts of five to ten years and promises of return passages when the contracts expired (Vertovec 2001). These men and women—almost a quarter of a million strong—would spend the next eight decades toiling on the sugar plantations and rice fields of Guyana’s soil2.

- 80 years

- 245 ships

- 500 voyages

- 23,900 souls

In his essay, “Why I Will Never Celebrate Indian Arrival Day,” Guyanese-born author Rajiv Mohabir, whose Indian indentured ancestors arrived in British Guiana in 1885, writes about the place of art to contend with the “dispossession and terror” stemming from the kālā pānī—“the sea: that original place of trauma”:

Like my mother, I am drawn to the sea. It can hold complexity and paradox in its blue throat. As a poet, I like to believe it is because I have a deep, abiding connection with history and motion. That my own rooted place in this world is to journey. I like to believe that I inherited not only the damage of being enslaved but also the seafarer’s heart, sturdy and craving motion.(Mohabir 2016)

As he conjures a gnawing ancestral memory and a third generation’s calling, Mohabir ponders on important questions: How can art respond? How can art engage these histories? In this curatorial essay, I explore the work of three key contemporary Guyanese artists—Maya Mackrandilal, Michael Lam, and Suchitra Mattai—who engage with Derek Walcott’s seminal poem, “The Sea is History” (Walcott 2007) by engaging with the kala pani as object, material, symbol, and archive3. Collectively, their artworks return us to the past to offer a visceral reminder of the precarious indentured immigrant crossings for Indians, marking the sea the place where ancestral histories, trauma, and survival all share space. Grounding us in the present and pointing us to a future, these works also function as contemporary tools of remembrance and repair. Two centuries later, the rupture created by the initial crossing of the kālā pānī remains pervasive. It now haunts that second wave of migration out of Guyana—an exodus so pervasive that the country has been deemed “a disappearing nation.”4 In what seems like a mythical diaspora, over one million Guyanese citizens now live in global metropolises like New York City (where they are the fifth largest immigrant group) (Lobo and Salvo 2013), London, and Toronto, while the country itself has a population of around 790,000. In other words, Guyana is a country where more people live outside its borders than within it.

2. Kālā Pānī|काला पानी—Black Waters

In Hindi or Bhojpuri, kālā means black and pānī means water. Guyanese-American artist Maya Mackrandilal poignantly captures its symbolic meanings in her eponymous video work, Kal/Pani (2014), “They called the sea kala pani, black water. To cross it was a rupture, a separation from the land, from culture, from caste, to be forever outside, forever a nomad.” The concept of the ‘black waters’ and its ensnaring mythologies carried over centuries and across oceans have their origin in ancient Indian Brahmanic texts. Scholars Crispin Bates and Marina Carter note that in decrying sea crossings for Indians, the texts deemed it as “antithetical to Hindu culture, entailing a separation of the traveler from the holy Ganges, thereby breaking the reincarnation cycle and engendering a loss of caste.”5 From those ancient religious readings’ warning of the dangers of oceanic crossings, the phrase evolved into being heavily politicized and divisive. In the late 19th century and into the early 20th century, it was used as part of anti-indenture campaigns by Indian nationalists. Simultaneously, British colonials exploited Indians’ fear of the kālā pānī as equal to death by weaponizing travel and banishment to overseas locations as an official form of punishment for convicts. In other words, “innumerable evils of caste defilement associated in the minds of Indians with the crossing of the kālā pānī were more efficacious as a deterrent to crime than even the death sentence.”6

However, by the mid-20th century, after indenture had ended, a kālā pānī of the imaginary began to flourish. “The kālā pānī concept thus became increasingly associated with the emotive, imaginative scenarios depicted by literary and political figures rather than with the scant gleanings of the colonial archive. It spawned patriotic novels, plays and even movies[.]”7 As a result, the concept saw a new life, recast as a powerful creative literary and imagery device to understand and examine indenture—its trauma, psychic dislocations, and its afterlife. So, although the ways in which the phrase has been used, abused, and co-opted over centuries have shifted, what remains prescient is the creative power of the kālā pānī. Its presence can be found in Bhojpuri folk songs and in theater, invoked widely in poetry and literature by Indian intellectual luminaries, such as Rabindranath Tagore, and Khal Torabully, and, increasingly, dynamically engaged by contemporary visual artists. Furthermore, the pioneering work of Guyanese-born poets David Dabydeen, Mahadai Das, and Rajkumari Singh, among others, has honored the histories of their Indian ancestors and importantly, positioned the experiences of those who crossed the kālā pānī to Guyana’s shores of Berbice and Demerara squarely within the creative, literary, and scholarly discourses of indenture. As Bates and Carter note:

This positive re-envisioning of the black waters trope has in turn helped to foster a renaissance of diaspora writing centered on the reimagined crossing, at once traumatic and empowering. Increasingly, kala pani is used as a literary and creative device, a tool for descendants of indentured migrants, and the writers and artists who excavate their encounters, to imagine and express the experiences and feelings of their ancestors.8

As a cautionary note to this re-envisioning, however, artist and scholar Andil Gosine posits that artistic responses to the kālā pānī have often rested on the figure of indenture lacking agency:

[T]he dominant tropes employed in the illustration of Indo-Caribbean history: men on ships, workers in the canefield, pious women covered in veils, places of worship. These indentured laborers were indistinguishable from each other, none conveying any kind of specific story that might register them as having a complex human subjectivity to the audience, a consequence of the representational projects about Indo-Caribbean people.”(Gosine 2021)

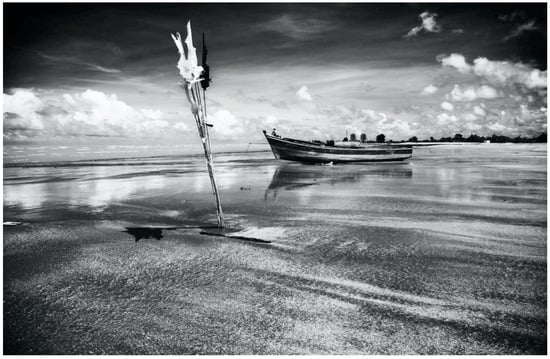

In contrast, the bodies of work by Mackrandilal, Lam, and Mattai explored below, move past these dominant tropes. Instead, they are curated here largely because they eschew the figure of indenture. Through an emphasis on the poetic, the metaphorical, and the abstract, these works encourage us to see visual artistic practices that can and do transcend “men [and women] on ships” to engage with the complicated experiences of crossing the kālā pānī and with the afterlives of British indentureship in Guyana (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Michael Lam, Seaward Bowline (Georgetown, Guyana), from the series, Oniabo, 2013–present.

3. What Water Knows

“Embrace the void, or embrace the land,” says Maya Mackrandilal, the American-born artist whose maternal lineage is Guyanese. Invoking the kālā pānī as “the void,” she narrates the eponymous video work Kal/Pani (2014) (Figure 2). We never see her physical presence, and rarely anyone else’s. Only a short glimpse of a shadow figure and the back of the artist’s aunt as she washes down tombs of family members are seen toward the end of the video’s almost nine-minute length. In other words, there are mostly hidden figures, ghostly figures, or symbolic figures in Mackrandilal’s Kal/Pani. Of these intentional absences, the artist explains, “These images, and the sometimes abstracted nature of the text itself, are expressions of the histories that have been lost to time and memory, the realities we gloss over, the names we forget, and the feelings that remain as our heritage is passed from one body to the next.” (Mackrandilal 2020). However, we do hear the artist’s voice as dominant and omnipotent throughout the video. Mackrandilal—a published poet and essayist—wrote poetic meditations for the video poem, and in doing so, created a soundtrack of poignant words that float over a series of scenes, told in Parts I through to VII, meant to conjure the crossing of the kālā pānī.

Figure 2.

Maya Mackrandilal, Kal/Pani (still from video), 2014. SD video with sound, 8:52 min.

Part 1 embeds us in a narrowed point-of-view perspective: we see what is ahead only from the viewpoint of the front of a small wooden fishing boat as it races through dark, murky waters. Mackrandilal notes:

From above, the water looks like a giant knife cut a dark winding gash through the land. On the ground, our boat rumbles to a start—everything seems soft, overripe. The creek water is almost black, so rich with particles that your hand disappears completely once the water reaches your elbow. It’s hard to speak above the air rushing past and the roar of the motor.9

The boat is multifunctional in the work—it is the literal vehicle for physical movement through the black waters, it is the plot device that moves the video’s narrative from scene to scene, shore to shore. Finally, it is the metaphorical device used to mimic the psychological journey through arduous waters—the difference between what Mackrandilal notes as “what is seen and what is felt.” Later, we shift from water to land via the point of view of a figure walking through landscapes of grasslands and rice fields. Between these acts of movement are scenes of the domestic space, of the home, in which curtains sway in a light breeze. In addition, scenes from the point of view of inside a car’s front windshield window as it drives through rocky unpaved roads in backdams and savannahs punctuate the dominant scenes of water in Kal/Pani. Attempting to mimic the physical and psychological symptoms of motion sickness, Mackrandilal ponders, “I wonder if my body’s reaction to motion is the legacy of my foremothers. The trace of their fear (encoded in flesh) as they moved across the globe like cargo.”10

In Part III, Mackrandilal directly invokes the kālā pānī in her poetic language:

They called the sea Kal Pani—black water. They said if you crossed it, you lost caste—you became forever severed from your life, from the land. I often wonder what they must have thought, emerging from the tomb-like ships, to a land with such unctuous rivers—rivers that on certain still evenings take on the quality of black glass—a river of ink—kālā pānī.(Mackrandilal 2014)

For Mackrandilal, a kālā pānī articulated in metaphors of “the void,” “black glass,” “rivers of ink” and “the silent black void” expands both the visual language and the literary lexicon of the kālā pānī. On its own, without the artist’s statement and any accompanying contextualization, Kal/Pani viewed can be read as a precarious universal crossing, “thrown outside of time.”11 Indeed, neither visual markers nor language within the video itself, even in its final part, Part VII, described below, register a specific geography marking it as a sea voyage from India to the shores of Guyana. Additionally, in doing so, the haunting power of Kal/Pani lies in its simultaneous universality and specificity—a reminder that through an assemblage of shorelines, seas, and oceans, the lands of Latin America and the archipelagoes of the Caribbean are interconnected via their histories of migration, displacement, and labor.

In Part VII, the final scenes of Kal/Pani depict ritual, rites, burial, and ceremony.

We are granted entrance into a family’s private and sacred grief. With bare hands, we see a woman washing down large white concrete, above-ground tombs with generous buckets of water. The water cleanses the tombs’ headstones marking the memories of this woman’s ancestors. Her final gesture, and in tandem the final scene of Kal/Pani, is to rest a single branch with a red flower on one of the tombs. In this moment of reverence, Mackrandilal’s voice tells us these preparations are for her grandmother: “Nanie asked that we build her tomb high above the ground, so the flooding river would not touch her body.”12 The unpainted tomb belongs to her.

In Kal/Pani, we meet Mackrandilal in the tenuous space of returning to an ancestral place in the midst of loss and death. To film Kal/Pani, the artist returned to Guyana in 2011, to Mahaicony in East Coast Demerara, Mahaica-Berbice where both her Guyanese-born grandmother and mother grew up and where her relatives still live. While there, Mackrandilal’s maternal grandmother, “Nanie,” as she lovingly calls her in Kal/Pani, unexpectedly passed away in the United States and was being returned to her family’s land for her last rites and as her final resting place. The specificity of Mackrandilal’s family land in Mahaicony as a place becomes particularly of note in this final scene. Largely a fishing and farming community of small villages, Mahaicony is located on the banks of the eponymous Mahaicony River, a body of water that runs directly into the Atlantic Ocean and is historically and economically important as a main avenue for transportation. Indeed, although defenses were built to protect the Mahaicony area, strong tides and heavy rains often deteriorate both natural defenses and man-built dams that leave the regions vulnerable to present-day climate crises, such as dangerous rising water levels, waterlogged lands, and severe flooding as a result of “the cold, black water (Papannah 2021). In tandem, the “flooding water” Nanie asks to be protected from, even in death, brings the fear of the kālā pānī in the life of a descendant of indenture full circle—from her 19th century ancestral beginnings and initial crossings to her 21st century recrossings and endings. For Nanie, then as now, the black water is trauma.

Because Mackrandilal grounds her visual practice in the poetics of indenture, her choice to center her maternal grandmother as the protagonist of Kal/Pani places the video poem in a beautiful conversation with the award-winning poem Per Ajie (1971) by Indian-Guyanese poet Rajkumari Singh (1923–1979). In the poem, Singh uses “ajie”—the loving term used by Guyanese Hindus to refer to a paternal grandmother—to visualize what indentureship might have been like for her own paternal great-grandmother. The personal seeps into the political as Singh reimagines the protagonist Ajie as the first Indian indentured woman to land on British Guiana’s shores. In the poem’s first stanza, she invokes Ajie’s crossing of the kālā pānī:

- Per Ajie

- In my dreams

- I visualise

- Thy dark eyes

- Peering to penetrate

- The misty haze

- Veiling the coast

- of Guyana.

Rajkumari Singh, 1971

For Mackrandilal to insert her poetic voice as a dominant presence throughout Kal/Pani speaks to what scholar Anita Baksh argues for Singh, and I would add that Mackrandilal exemplifies: “Recognizing oral narratives as sites of indenture history and of women’s stories, Singh legitimates her own poetic voice.” (Baksh 2016).

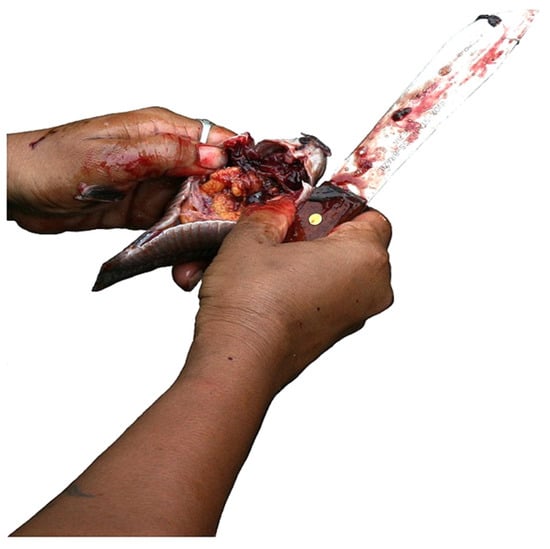

Mackrandilal often accompanies Kal/Pani with Mudra Erasure (2015) (Figure 3) a series of photographic portraits of mudrās—symbolic hand gestures used in Hindu ceremonies and in classical Indian dance forms such as Kathak, Bharatanatyam, and Odissi. The Mudra Erasure portraits feature the hands of women in Mackrandilal’s family symbolically gesturing to the yoni, alapadma, kangula, kapittha, and padmoksha mudras referenced in the artworks’ eponymous titles. To invoke mudras is a subversive artistic gesture on the part of Mackrandilal. It serves as a reminder of the 1947 Act in British-ruled India banning women and girls from dancing in Hindu temples as part of any religious rituals as the “British saw these women, because of their ritualized connection to the Hindu gods, as proof of an inferior religion and a culture of loose morality.” (Puri 2015). In addition, the hands hold objects of foods native to Guyana: a gutted hassa fish (Figure 3), a pierced green coconut, pacay fruit (known as whitie in Guyana), a halved sapodilla, and a river water crab. Most of these objects have been violently ruptured, pierced, gutted, or torn apart. In combining Kal/Pani with Mudra Erasure, Mackrandilal connects the first rupturing that scarred generations of those who ventured into the kala pani two centuries ago to the second rupturing that marks those who embark on crossings of their own twenty-first century dark waters. Like the majority of the Indian indentured laborers to British Guiana who never returned to their ancestral land of India but made their borrowed land their new home, so too did the artist, her mother (who migrated to the United States in 1976) and grandmother—three generations of Mackrandilal women—leave Guyana to lay claim to the United States. “Acres of rice farm in a country we rarely visit… What are we, the generation that exists in the … wake of estrangement, to make of the pieces?” asks Mackrandilal in Kal/Pani. As she contemplates the past, pondering what was lost as the majority of the indentured laborers never returned to India, and what will be lost as her family now rarely returns to Guyana; Mackrandilal identifies that distance and absence now lay claim to dual homelands.

Figure 3.

Maya Mackrandilal, Yoni Mudra, from the series, Mudra Erasure, 2015. Digital image/pigment print, 20 × 26 inches.

4. Our Waters Hold Our Stories

While Mackrandilal’s Kal/Pani requires us to meditate on water as history, Michael Lam encourages us to think deeply about its duality—the stories that are held in these waters and our present-day relationship to it. Guyana is a site of water. The original name, “Guiana” is an Amerindian word that translates to “Land of Many Waters.” The country’s indigenous naming is also reflective of the ubiquity and precariousness of water. Three mighty rivers, Corentyne, Berbice, Demerara and Essequibo, the majestic Kaieteur waterfall, and countless creeks, canals, streams, and backwaters crisscross the country. These waters continue to both shape and haunt the day-to-day lives of Guyanese people as “widespread flooding has inundated Guyana, swamping roads, homes and farmland.” (Papannah 2021). In his ongoing black and white photography series, Oniabo (2013–present), Georgetown-based photographer Michael Lam engages with the many coastlines, shorelines and waterways of Guyana to gesture to histories hidden in plain sight. Lam thinks of these waterways as a metaphor to surface stories. Of the series, the photographer states, “The Oniabo series is centered around the sea and its effect on the land and the people, how we see it and how we use it.” The artist is intentional in his naming of the series, compounding the “land of many waters” original meaning of “Guiana” with “oniabo,” which comes from the language of the indigenous Arawak people and translates to “water.” Here, the visual image and the literary naming both become symbolic.

The scenes of placid waters in Oniabo are meant to be deceiving. In Devotion Point (Figure 4) and Annandale (Figure 5), Lam captures tranquil scenes. In Seaward Bowline (Figure 1), in an otherwise usually vibrant entrepreneurial culture of fishing, we see a fisherman’s boat battened down and solitary. These stark black and white seascapes, and the sense of timelessness they embody, implore the viewer to meditate on the nation’s historical and pivotal relationship with water: a sacred natural resource for the country’s first Amerindian people, the means by which European colonizers first arrived, and the traumatic Trans-Atlantic Middle Passage that brought enslaved Africans to toil its soil. Notably, however, it is the presence of jhaṇḍī flags staked in these shorelines that disrupt their tranquility.

Figure 4.

Michael Lam, Devotion Point (Bushy Park, Parika, Essequibo), from the series, Oniabo, 2013.

Figure 5.

Michael Lam, Annandale (Demerara, Mahaica) from the series, Oniabo, 2017.

As objects of ritual and ceremony, Lam legibly references the religious iconology of the jhaṇḍī flags in his seascapes. They serve as an important symbolic object, a visceral reminder, of the precarious indentured crossings of the kālā pānī. Across Guyana, clusters of colorful jhaṇḍī flags—ceremonial Hindu prayer flags mounted on tall bamboo poles planted in the ground—are a common sight in private home shrines, front yards, temples, public spaces, and near bodies of water to indicate a puja, a Hindu prayer ceremony, has been performed13. In their ubiquity, these multi-colored triangular flags register Hinduism as the nation’s second most common religion, as well as signal how it first arrived and came to evolve as a dominant religious practice. During the nearly eighty years that indenture lasted in British Guiana, as Hindu Indians labored on sugar plantations and rice fields, the rituals and ceremonies they practiced and creatively reinvented served as sacred gestures to protect them from the violence and trauma that came with new identities as migrants and laborers on foreign soil. Historian Brinsaroo Samaroo writes, “In these recreated settlements Indians recalled and reinvented artifacts which had sustained them in their birthplace” as a way to build a new world for themselves and create “new physical and cultural spaces.” (Samaroo 2021). Under these precarious conditions, jhaṇḍī flags were planted to represent Hindu deities, their victories of good triumphing over evil, and often honored the Hindu god Hanuman as a symbol of strength and energy. Religion scholar Prea Persaud expands on the origins of the jhaṇḍī flag as a representation of the divine:

[D]uring indentureship, jhaṇḍī flags were used as a type of the murti, statues that embody various forms of the Divine, because laborers had few murtis of their own… Perhaps the notion of flags was appealing to indentured laborers, then, because they viewed their new homes in the Caribbean as a type of battlefield[.].(Persaud 2016)

After indenture ended and into present day Guyana, the presence of jhaṇḍī flags expanded beyond symbols of protection. They were increasingly used to mark the fields and homes of Indian landowners and to celebrate Hindu heritage and pride. While some scholars trace the ceremonial jhaṇḍī as a transfer specifically from the Bihar and Uttar Pradesh states in India, (Samaroo 2021) others note that it is uncommon to find jhaṇḍī flags throughout larger India. These flags may be unique to the Caribbean as they “came to be widely adopted in the [Indian] diaspora because Hindus found in them a convenient way of asserting their social identity in a new situation.” (Manuel 2009). Indeed, the jhaṇḍī flag can be found increasingly throughout major Guyanese and Caribbean diasporic communities such as Toronto and Queens, New York.

Subversively, the presence of the jhaṇḍī flags in these photographic works point to the colonial desire for the cheap labor of Indian bodies and to the dark history of the kālā pānī. The village of Kingston (Figure 1. Seaward Bowline) in Georgetown and the community of Annandale in Demerara-Mahaica (Figure 5. Annandale) were all former coffee, cotton, and sugar plantation sites whose lands were toiled by African, Indian, and Chinese hands. Further, water continues to traumatize these places, such as the port village of Parika (Figure 4. Devotion Point) located in the Essequibo Islands—West Demerara region, as they are prone to frequent flooding given their proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. Lam’s Oniabo series and his documentation of the present day jhaṇḍī flags planted on particular bodies of water along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean return us to the colonial past of these sites. His artistic choice to include the presence of jhaṇḍī flags planted on the shores of these vast bodies of water is to conjure the kālā pānī, to mark them as sites where the ancestral histories of the descendants of Indian indentured laborers, their collective traumas, modes of survival, and spiritual desires all share space. Notably, in Seaward Bowline and Devotion Point, some of the jhaṇḍī flags are faded, tattered and torn by their exposure to the heat, wind, and rain. Therein lies the punctum of Lam’s Oniabo series. Elusive and barely visible as their deteriorating physical condition might be, there is an unmistakable violence that has been done to them. Yet, they are material witnesses to rupture, remembrance, and repair.

5. Water as Archive

Embedded throughout Suchitra Mattai’s voluminous oeuvre are the histories, memories, and visual codes of the artist’s Indian-Guyanese heritage. In particular, Mattai’s extraordinary and towering sari works have come to characterize a dynamic practice that responds to the system of Indian indentured servitude and the kālā pānī crossing that brought Indians to British Guiana. Beyond revisiting the past, however, Mattai’s sari works importantly engage with how these histories have shaped the Indian diaspora in the West and the continued modern-day exploitations of migrant labor. Like Mackrandilal and Lam’s distinctive bodies of work, the figures of indentureship are absent in Mattai’s sari works. Instead, as an object, a sculpture, or a tool of abstraction, the sari affords Mattai the creative liberty to think about the kālā pānī in expanded, poetic, and metaphorical ways (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Suchitra Mattai, Exodus, 2019, vintage saris from India, Sharjah, artist’s Guyanese family, and rope net, 15 × 40 feet (Collection of the Momentary, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art).

Mattai, like so many Guyanese, is a migrant body. After leaving her birthplace of Guyana at three years old, she spent several years shifting from Nova Scotia, Canada; Udaipur, India; and in the United States, from Philadelphia to New York to Minneapolis, and finally, to Denver, where she is now settled. The artist’s migratory paths through Guyana, Canada, and the United States—places where she has attempted to make a home—as well as her transitory journeys throughout India, the Caribbean, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe—geographic points she has spent considerable time by passing through—chart a dynamic artistic practice. As a result, she invokes her own contemporary migrations in her work, as well as her ancestral migration origin story, started long before she left Guyana in 1977:

My family, who first came as Indian indentured servants to British Guiana, is part of a history of ocean voyages to foreign lands by means of contracts of bondage. And so, as an artist, much of my practice is driven by this idea of an invented, idealized “homeland.” My artwork is characterized by disconnected “landscapes” that are unreal but offer a lingering familiarity.(Mattai 2020)

These multiple migrations have informed an oeuvre teeming with laborious detail, texture, and materiality—symbolic of all the things we carry, tangible and intangible, across oceans, lands, and borders. Of those things we carry, Mattai is adept at selecting and weaving together a bounty of objects suggestive of the violent colonial history of British indentured servitude in Guyana and its ensuing turbulent and disruptive traumas. The sari, a Sanskrit word meaning “strip of cloth,” has emerged as one of those compelling objects. Returning to their original meaning and form, Mattai cuts the saris into strips. Then, with the artist’s capable hands, the multi-colored vintage worn saris are stitched, woven, layered, braided, tucked, and folded luxuriously into each other.

They are enticing, soft and delicate to the touch. They are also a study of the power of fabric to seduce, transform, and build worlds. Via Mattai’s unrestrained imagination, she fashions and shapes worlds, old and new, via her sari works.

One of the first beginnings of this body of work, and a most notable example, is Mattai’s commission for the 2019 Sharjah Biennial. Responding thoughtfully and with great care to the Biennial’s urgent curatorial charge, Look for Me All Around You, Mattai joined participating artists who created “an open platform of migrant images” in a fraught moment when “borders and beliefs are under constant renegotiation” and “in response to [unprecedented] human and material displacement” (Tancons n.d.) Mattai collected all kinds of silk, cotton, and polyester saris, worn by Indian women in the United Arab Emirates, as well as India and the Caribbean, including those of her own intimate and extended family members and friends throughout the Indian diaspora, to weave the large-scale tapestry Imperfect Isometry (Figure 7). Mattai observes, “I am reimagining colonial histories and including the voices of the slaves and laborers who were omitted in those narratives.”14 The omissions she speaks of—the absences in the archives documenting the experiences of indentured laborers in British Guiana—are known all too well. In response, Mattai offers up the personal and the familial to mind those gaps: “I tell my family’s stories because these are the stories of people you wouldn’t hear otherwise…. I bring [their] longing for [the] past into that story. A past that was ruptured by indentured labor.” (Gomez-Upegui 2022).

Figure 7.

Suchitra Mattai, Imperfect Isometry, 2019, vintage sari tapestry (Sharjah Biennial).

With the sari tapestry An Alien Spirit with a Breathtaking View (Figure 8), Mattai follows through with a commitment to use her family’s stories as a narrative device to draw attention to histories that are either untold, under-told, mis-told, or misrepresented. For example, metallic ghungroo bells, the musical instrument and ornament worn on the ankles of Indian classical dancers, are woven into the sari tapestry. They are both an important cultural reference to a revered Indian art form, as well as a sweet nod to Mattai’s sister who is a student of the Indian classical dance Bharatanatyam.

Figure 8.

Suchitra Mattai, An Alien Spirit with a Breathtaking View, 2022, vintage saris, fabric, cord, ghungroo bells, and garland, 76 × 80 inches.

Similar to Mackrandilal’s Mudra Erasure, they also serve as a reminder of the law that banned these very artforms in British-ruled India.

The colonial archives often fail us. So our waters and our lands become our archives. As a repository of history, the sari holds multiple stories of geography, of place, of people, of memory. In tandem, in the times and spaces where the voices of the indentured, of those that crossed the kālā pānī, have been silenced or omitted altogether from the archives, Mattai transforms the sari itself into a living, breathing archive. Of these acts of stitching and weaving together, Indian-Fijian artist, whose body of work also compellingly engages the kala pani, writes:

To remember, to stitch together and piece fragments of history for both collective and individual remembrance. To recenter knowledge, to account for colonial and personal histories. To connect the dots between that which has past and the realities of those lived experiences. To allow something invisible to become visible. To hold space for ancestors—past, present and future.(Lal 2019)

With this artistic gesture, a subversive one at that, Mattai wields the tools of what cultural historian Sadiya Hartman defines as critical fabulation. Speaking to the Museum of Modern Art on how artists specifically might see the necessity of critical fabulation as a response to the “silences, the obliteration of lives, all the things that we could not know,” Hartman reinforces the acts of world-building and archive-building Mattai attempts via the sari:

What’s really enabling about artistic practice is the way poets and filmmakers and visual artists use materials, the way beauty as both a practice and a method might enable some kind of redress, right? That might be a possible antidote to the violence that is a part of the everyday… I think that artistic practice becomes the exercise of imagining beauty and what it might make possible in the world.(Hartman 2021)

In Exodus (Figure 6), Mattai continues building worlds and creating archives in another monumental sari tapestry whose size, one that dominates the full length and height of a 15 × 40-foot wall, speaks to the unspeakable scale of dispersion for those who crossed the kala pani. The title of the work itself, “exodus,” conjures the mass departure of people, from the first 396 Indians who crossed the kālā pānī for British Guiana at the beginning of indenture to the almost quarter million by its end. In tandem, Mattai reunites more than 200 saris gathered from across the Indian diaspora for its construction. In many ways, Exodus visually renders as a sea of saris. Like the punctum—the weathered and faded jhaṇḍī flags—in Lam’s photographs, Mattai weaved into Exodus the sun-bleached and faded saris from Imperfect Isometry after the work had been taken down from its outdoor installation in Sharjah and returned to her in Denver. Although the heat and sun had lightened and diminished the materials’ vibrancy and the starkness of their colors, for Mattai, these faded saris and the stories they hold of the women who wore them, are not disposable. They too become material witnesses to rupture, remembrance, and repair. The journey of these saris as objects of migration symbolize the stories of Indian indentured laborers and their descendants, who first crossed the kālā pānī from India and over time, oceans, and borders, built a new diasporic world. In the artist’s careful hands, these stories like these saris, are made, unmade, and remade again.

While Imperfect Isometry and Exodus rely on a sea of saris to conjure an imaginary kālā pānī, in the sari sculpture and installation Life-Line (Figure 9), Mattai engages with the kālā pānī literally by including a boat in the sari work. Suspended ominously in mid-air and tilting on its axis, almost falling over, the wooden boat directly signals the perilous ocean voyage. In this work, the “life-line” that hangs from the boat is made of saris tightly twisted and braided into one long continuous long rope, which eventually forms concentric circles on the ground. The perilous ocean voyage in Life-Line is not merely an allusion, however. As Mattai explains, her paternal great-grandparents were among the small number of indentured laborers who embarked on a return passage to India in the early 1900s after their five year contracts were complete:

[A]fter they took the boat back, they realized that there were certain freedoms that they could have if they stayed in Guyana but not in India. They later made the voyage all the way back to Guyana. The passage from India to the West was on small, cramped boats. It’s quite fascinating that they would go back home [India] and then return to Guyana at that level of peril.(Hart 2020)

Figure 9.

Suchitra Mattai, Life-Line, 2020, vintage saris, found boat, 12 × 10 feet (K Contemporary).

Beyond the artist’s own family voyage of return to India and back, Mattai’s Life-Line also calls to mind David Dabydeen’s notable poem Coolie Odyssey in which the Guyanese-British poet imagines the moment of disembarkment for that first Indian 5 May 1838 arrival in British Guiana.

Coolie Odyssey

- The first boat chugged to the muddy port

- Of King George’s Town.

- Coolies come to rest

- In El Dorado,

- Their faces and best saries black with soot.

- The men smelt of saltwater mixed with rum.

- The odyssey was plank between river and land,

- Mere yards but of plotting

- In the packed bowel of a white man’s boat

- The years of promise, years of expanse.

David Dabydeen, 1988

The poem’s imagery of newly indentured laborers walking down the planks of “the packed bowel of a white man’s boat” in “sarees black with soot” underscores its equally precarious tone. Its poetic precarity is in stark dialogue with the dangerously looming boat and twisted sari rope in Life-Line and the pathos of stifling bondage they conjure.

Mattai’s sari works form a prolific body of work that significantly underscores the artist’s concern for the movements of peoples, starting with her own family’s crossings of the kālā pānī and, expansively, those of the indentured. In the absence of architectural monuments for those lost, physically and metaphorically, to the kala pani, Mattai’s large-scale sari works stand in as monuments to honor all that has been lost. “Making a very large tapestry was an ode, a monumental ode, to those people,” she offers15. Beyond her personal-political response to the kālā pānī, Mattai simultaneously engages with the potential of art to speak to who and what gets left behind, and what survives and what is mourned, when we leave one place for another whether by choice or by force. In doing so, Mattai is in a constant and important conversation, in both subtle and overt ways, about how we navigate through and out of migration and displacement.

6. Conclusions

While the representations of water—as symbolic of history, healing, death, trauma, and spirituality—figure prominently in Latin American and Caribbean art, the artworks explored here are notable as they implicate how little attention the kālā pānī crossings of Indian indentured laborers to Latin America and the Caribbean—including Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Grenada, St. Vincent, St. Kitts, Guadeloupe, and Suriname—have received. In his seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, Franz Franon wrote:

Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures, and destroys it.(Fanon 1963)

What then does it mean for the past of the kālā pānī to have agency? To wrestle with this question is essentially what these and other contemporary artists navigate in their artistic responses to the kālā pānī. In doing so, they endeavor to push back against the distortions, silences, and violences of this history through art in ways that create unbounded space for the poetic, the metaphoric, the abstract.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Indian Arrival Day is also commemorated in former British colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean such as: Jamaica, 10 May; Trinidad, 30 May; and Suriname, 5 June. |

| 2 | In the larger Caribbean, approximately half a million Indian indentured laborers were brought from India to other British colonies such as Trinidad and Jamaica. See (Lai 2004). |

| 3 | The exhibition The Sea is History is an example of how global contemporary artists use Derek Walcott’s seminal poem to address issues of displacement. See (Wendt 2019). |

| 4 | “A Disappearing Nation,” Neither There Nor Here, BBC Radio 4, 28 February 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08gmtx1, accessed on 1 January 2023. |

| 5 | Bates and Carter (2021). In this paper, Bates and Carter trace the reconstruction and deconstruction of kālā pānī, from its origin as a Brahmanic text warning about the dangers of oceanic voyages, through its anti-emigration uses by India, its abuse as a British colonial construction, and its recasting as a historical trope and a literary device. |

| 6 | Ibid, 41. |

| 7 | Ibid, 52. |

| 8 | Ibid, 54. |

| 9 | Ibid. |

| 10 | Ibid. |

| 11 | Ibid. |

| 12 | Ibid. |

| 13 | According to Prea Persaud, “The term “jhandi” refers to the combination of the flag and the bamboo, but Indo-Caribbeans will also say “jhandi flags” which emphasizes the importance of the flag. Indo-Guyanese will also use the term “jhandi” to refer to religious prayers held at a person’s home.” See (Persaud 2016). |

| 14 | “10 Questions with Suchitra Mattai,” Les Iles, 31 August 2020, https://www.lesiles.com/blogs/blog/10-questions-with-suchitra-mattai, accessed on 1 January 2023. |

| 15 | Ibid. |

References

- Baksh, Anita. 2016. Indentureship, Land, and Indo-Caribbean Feminist Thought in the Literature of Rajkumari Singh and Mahadai Das. In Indo-Caribbean Feminist Thought: Genealogies, Theories, Enactments. Edited by Gabriel Hosein and Lisa Outar. New York: Palgrave, pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Crispin, and Marina Carter. 2021. Kala Pani Revisited: Indian Labour Migrants and the Sea Crossing. Journal of Indentureship and its Legacies 1: 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. Greenwich Village: Grove Press, pp. 210–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Upegui, Salome. 2022. Suchitra Mattai’s Soulful Works Convey Unspeakable Truths. Artsy. February 4. Available online: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-suchitra-mattais-soulful-works-convey-unspeakable-truths (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Gosine, Andil. 2021. Nature’s Wild: Love, Sex, and Law in the Caribbean. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 128–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Rebecca. 2020. Suchitra Mattai: Interview by Rebecca Hart. Foundwork. June 24. Available online: https://foundwork.art/dialogues/suchitra-mattai (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Hartman, Sadiya. 2021. Gallery 214: Critical Fabulations. New York: Museum of Modern Art. Available online: https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/298/4088 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Lai, Walton Look. 2004. Indentured Labor, Caribbean Sugar: Chinese and Indian Migrants to the British West Indies: 1838–1918. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, Shivanjani. 2019. Artist Statement: Yaad Karo. April 3. Available online: https://shivanjani-lal.tumblr.com/post/183908708957/yaad-karo-to-remember-to-stitch-together-and (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Lobo, Arun Peter, and Joseph J. Salvo. 2013. The Newest New Yorker, 2013 Edition: Characteristics of the City’s Foreign-Born Population. New York: New York City Department of City Planning, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mackrandilal, Maya. 2014. Kal/Pani. SD Video with Sound, 8:52 min. Available online: https://mayamackrandilal.com/artwork/3789258-Kal-Pani.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Mackrandilal, Maya. 2020. Keeping Wake. In Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. Edited by Grace Aneiza Ali. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. Available online: https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0218/ch12.xhtml#_idTextAnchor230 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Manuel, Peter. 2009. Transnational Chowtal: Bhojpuri Folk Song from North India to the Caribbean, Fiji, and Beyond. Asian Music 40: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattai, Suchitra. 2020. Revisionist. In Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. Edited by Grace Aneiza Ali. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. Available online: https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0218/ch12.xhtml#_idTextAnchor230 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Mohabir, Rajiv. 2016. Why I Will Never Celebrate Indian Arrival Day. The Margins. June 6. Available online: https://aaww.org/indian-arrival-day/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Papannah, David. 2021. Mahaicony River Remains in Deep Flood, Some Residents Insist Conservancy Water Pouring. Stabroek News. June 7. Available online: https://www.stabroeknews.com/2021/06/07/news/guyana/mahaicony-river-remains-in-deep-flood-some-residents-insist-conservancy-water-pouring-in/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Persaud, Prea. 2016. Cultural Battlefields: Jhandi Flags and the Indo-Caribbean Fight for Recognition. Quotidian. November 27. Available online: https://www.quotidian.pub/cultural-battlefields-jhandi-flags-and-the-indo-caribbean-fight-for-recognition/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Puri, Stine Simonsen. 2015. Dancing Through Laws: A History of Legal and Moral Regulation of Temple Dance in India. Navei Reet: Nordic Journal of Law and Social Research 6: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaroo, Brinsley. 2021. Changing Caribbean Geographies: Connections in Flora, Fauna and Patterns of Settlement from Indian Inheritances. Journal of Indentureship and its Legacies 1: 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancons, Claire. n.d. Look for Me All Around You. In Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber. Sharjah: Sharjah Art Foundation, p. 19.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2001. The Hindu Diaspora: Comparative Patterns. New York: Routledge, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Walcott, Derek. 2007. The Sea is History. In Selected Poems by Derek Walcott. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Available online: https://poets.org/poem/sea-history (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Wendt, Selene, ed. 2019. The Sea Is History. Milano: Skira editore S.p.A. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).