1. Background

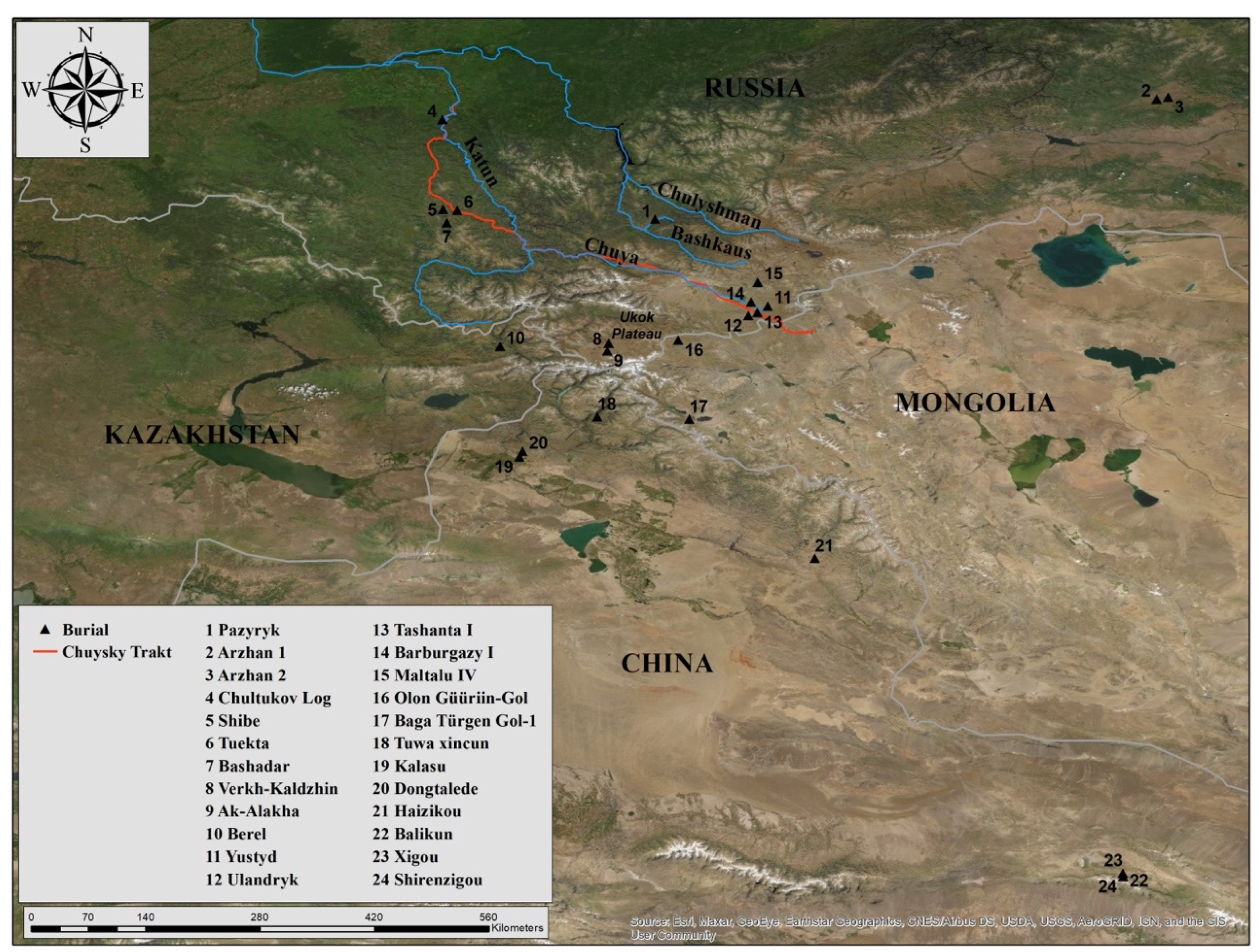

In the fourth and third centuries BCE, a group of pastoral peoples now called the Pazyryk Culture lived and buried their dead in mounded tombs in the Gorny-Altai district of Siberia in the region where modern Russia, Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan meet (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022;

Tishkin and Dashkovskii 2003, p. 144;

Hiebert 1992) (

Figure 1). Archaeological evidence indicates that horses were put to death very regularly there as part of funerary rituals. Every day, though, the Pazyryk peoples used these horses for meat, milk, hair, and skins, as well as for traction, but above all, for riding. Not only were horses the backbone of the mobile functioning and mounted defense of these communities but they also played a central role in displaying the centralizing power and authority of their trade in horses (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022, pp. 39–45).

Pazyryk funerary customs such as the ritual killing of horses were passed along to the Pazyryk area from Tuva where horses were sacrificed and buried at Arzhan I (9th century BCE) and Arzhan II (7th century. BCE) (

Griaznov 1980;

Grjaznov 1984;

Čugunov et al. 2010). In addition, horse sacrifice is known in territories to the east of Pazyryk in western Mongolia and to the south in western China in Xinjiang, in newly recovered materials both contemporary and later than the Pazyryk Culture. For instance, at a site called Kalasu, where in burial M15, 13 horses were deposited and adorned with ornaments and harnesses including metal bits, gold inlay bronzes, and lacquer pieces decorated with golden foil in the style of Pazyryk.

1 In one case, a lacquered mask for a horse, but without antlers or horns, was recovered (

Yu et al. 2020). Although the practice at Kalasu parallels that in Pazyryk and a related site in Kazakhstan at Berel (

Francfort et al. 2006;

Samashev 2006,

2011,

2012), the lacquered leather look-alikes and other ornaments found at Kalasu were clearly adapted to local Xinjiang technology and custom. These materials confirm the movement and adoption of certain practices, goods, and perhaps even people into and out of the Pazyryk zone between the ninth and second centuries BCE (

Shulga and Shulga 2017;

XJKGS 2015;

Yu et al. 2020).

Horses were clearly an important component in the funerals of these Pazyryk Culture mobile pastoralists, but beyond the funerary rituals, the presence of both actual and sculptural horses was also conspicuous in daily life. Horses were a mark of status, identity, and their ability to adapt to and succeed in the enterprise of the horse trade under local environmental and historical conditions. Why should such a valuable resource be sacrificed and taken from practical use in a place where their livelihood depended on the availability of the animal to survive? Were they perhaps costly signals and/or signs of conspicuous consumption? Moreover, why should the little images of the horse/deer appear in only select graves?

In the absence of written documents and with only the excavated context as evidence to guide interpretation, we turn to the archeological context for clues to provide preliminary insight into the sacrifice of the animals, the “dressing up” of the horses as deer and mountain goats, and the production of small-scale images of deer/horse. Particularly relevant to this discussion is the observation that all social levels of the Pazyryk Culture community sacrificed some of this valuable resource. Distribution patterns in the funerary record show the socio-political and/or symbolic spiritual value in the sacrificial action and use of heraldic imagery. Particular notice will be made of the gender of the animals and human beings with whom they were buried and of the ubiquity of horses and deer in the mortal and posthumous lives of the interred. This analysis will offer clues about the behavior of sacrifices and the figurines, as well as the ambiguity in the imagery of both actual and sculpted deer/horses. Therefore, our discussion about how and where they were used and their relationship with the lives of their wearers leads to a functional interpretation.

After discerning the complexity and inconsistency found in the deer/horse images based on visual analysis, a functionalist framework positions these emblems and goods as embellishments to both the social and economic systems. In all, the use of the objects and their imagery point to an attempt to capture and maintain that which was most important for the livelihood of the community—family and group bonds, respect for the wild animal kingdom and for their domesticated herds, protection and bodily health of the deceased, and status within, and perhaps outside of, the local group. Maintaining their social order and ritual schedule required an ordered society that included the effort of many and several levels of responsibility and authority. All the pertinent material we introduce and systematically examine here takes into account both historiographic and renewed visual analysis as evidence of the rites and values placed on the dead in burial, but our analysis has not led to direct knowledge of the religious beliefs of the Pazrykians. That does not exclude the possibility that the objects and their décor represented spiritualized ideas, but deciphering or attaching precise meanings to the images is not our goal. We leave that debate to others.

2 2. Archaeological Context

In the early to mid-20th century, Mikhail P. Griaznov (in 1929) and Sergei I. Rudenko (in 1947–1949) explored five large, mounded kurgans preserved in permafrost, and three smaller ones, at Pazyryk in the valley of the Ulagan River in the Russian Altai. Although the tombs had been robbed, mummies and skeletal remains together with many grave goods and sacrificed horses were found preserved there. Later in the 20th century, Vladimir D. Kubarev excavated cemeteries of much smaller mounded burials of non-elites of the same period, the Yustyd, Ulandryk, and Sailiugem burial complexes (

Kubarev 1987,

1991,

1992). Nearby on the Ukok Plateau, Novosibirsk archaeologists Natalia Polosmak and Vyacheslav Molodin recovered intact mounded kurgans dating from the same period (

Polosmak 1994,

2001;

Polosmak and Molodin 2000). Other excavations have extended the known range of this culture group to mounded burials at Berel in Kazakhstan, first by Wilhelm Radloff in the 19th century (

Jettmar 1967, pp. 188–89) and more recently by the Kazakh-French team led by Zainullah Samashev and Henri-Paul Francfort (

Francfort et al. 2006;

Samashev 2006,

2011,

2012). Evidence of the Pazyryk Culture expansion comes from western Mongolia at several sites in the Baian-Ölgii aimag, including surveys and excavation by a variety of international teams (

Törbat et al. 2009;

Turbat and Tseveendorj 2016). Both horse remains and/or small-sculpted images of horses accompanied the deceased in many of these burials. Trade and diplomatic networks tied the people buried at these sites together in antiquity, while those in western Mongolia and China suggest that a diaspora of Pazyrykians migrated out of their homeland under both political and climatic distress (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022;

Stark 2012). Whether the masking of horses and its Pazyrykian meaning in burial was put down intact in China is yet to be determined, although, clearly, the horse remained central to those communities as well.

The precursors to the Pazyryk peoples such as at Arzhan I in Tuva (

Griaznov 1980;

Grjaznov 1984) demonstrate the importance of horses in burial rituals and suggest that the presentation and exchange of horses were part of establishing, ratifying, and displaying the bonds of corporate loyalty as early as the 9th century BCE (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022, pp. 1–16). By the Pazyryk period (4th-3rd centuries BCE), the mounds covering the burials were smaller in scale; the largest, Pazyryk Kurgan 1, was 47 m in diameter. The numbers of horses were similar to or less than at Arzhan 2 in Tuva (ca. 7th c. BCE), which had 14 horses (

Čugunov et al. 2010;

Bourova 2004): Pazyryk Kurgan 2 and Kurgan 4 (14 horses); Pazyryk Kurgan 1 (10 horses) (

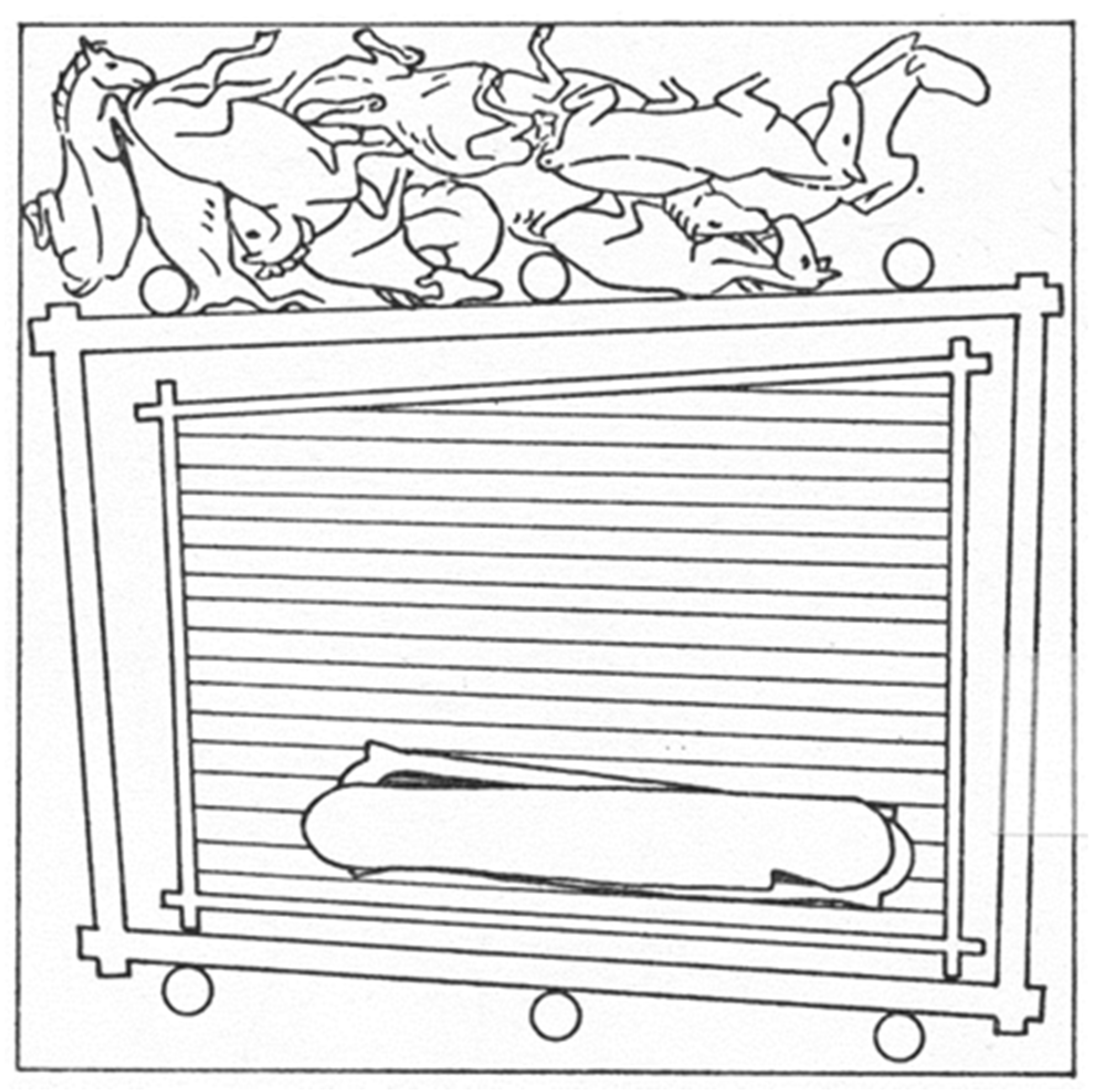

Figure 2); Pazyryk Kurgan 5 (9 horses); and Pazyryk 2 (7 horses). Among the last of the Pazyryk mounded burials, Kurgan 6, with a smaller, 14–15 diameter mound, contained 3 horses. The largest of the burials at Berel, in today’s Kazakhstan, also contained horses in numbers comparable to those at Pazyryk: Berel 1 (17 horses); Berel 10 (10 horses); and Berel 11 (13 horses). The largest burials at Pazyryk, Berel, and Ak-Alakha 1 (Burial 1, nine horses), therefore, contained approximately the same number of horses. The number of animals deposited in each tomb was, therefore, a deliberate and likely meaningful choice.

So, too, was the placement and manner of display of animals and their sculpted representational models. At both Pazyryk and Berel, the horses and their tack displayed indications of distant and different ownership. The suites of horse decoration in Berel 11 point to different geographical areas where allies of the deceased resided according to Francfort (

Francfort et al. 2006, pp. 122–23;

Francfort and Lepetz 2010). Although the distinctive genomic changes reported by Librado and the assembled team suggest that domestication of the horse in Eurasia occurred through the mixing of lineages (

Librado et al. 2016,

2017), and that mix is consistently discerned in those animals tested throughout the Pazyryk Culture sites such as at Berel, the Keyser-Tracqui team did not discern geographic affiliations for the animals themselves (

Keyser-Traqui et al. 2005, p. 203).

3 Such distinctions may have been made in the manner in which the animals were presented. For example, at Pazyryk, the ears of horses were clipped with distinctive marks, which have been thought to represent different owners (

Rudenko 1970, pp. 117–19). In contrast to the suggestions about horses being gifted at the time of death from multiple sources, as at Berel 11,

Rudenko (

1970, p. 119) suggested that all horses buried with the deceased were the deceased’s own. Furthermore,

Gala Argent (

2010;

2016), through an analysis of the masks and other tack on the Pazyryk horses, does concur that the horses belonged to the deceased and that the ornamentation communicated the role(s) each horse played in the life of the person in the tomb. The riders and their horses could have been partners for many years since many of the horses in these burials were not young (

Rubinson 2012: fn 60;

Lepetz et al. 2020). Whatever interpretation one holds, and from wherever the horses originated, the horses became or remained the property of the deceased ad infinitum.

The large burials at the Pazyryk uplands are assumed to be those of leaders with the greatest amount of accumulated wealth, and tombs high on the Ukok Plateau at Ak-Alakha, Verkh-Kal’dzhin, and Kuturguntas, as well as at Berel in the Bukhtarma River valley, were likely those of mid-level leaders/elites. More modestly appointed tombs of workers/herders/artisans/commoners excavated by Kubarev were also in upper steppe valleys. Although vertical patterns of migration characterize movements within sub-regions, and in lower valleys, breeding, foaling, and pasturing of animals could take place as would procurement of local products,

4 burials were located on the slopes above the surrounding valleys. The takeaway from all this evidence is that there was a concentrated and intense focus on horses and their role both in the lives and deaths of the entire population, not just the elite (

Linduff et al. forthcoming).

3. Cogency of Horses in Pazyryk Culture

The well-proportioned horses found in elite burials at the Pazyryk site were approximately 1.4 m (13.8 hands) at shoulder height, and thus slightly taller than others in the region (

Francfort and Lepetz 2010). They were gelded at Pazyryk, which would allow for their taller stature and greater tractability, but also would indicate that breeding animals were generally not sacrificed. Smaller herd horses were found in other tombs in the region (

Rudenko 1970, p. 56) suggesting that they were working animals and members of the larger herds, while the taller ones were selected and prepared for parade.

Horses from Berel tested for DNA showed different mitochondrial kin bases (

Orlando 2017;

Keyser-Traqui et al. 2005), and biogeographic partitioning showed that they were consistently local eastern Eurasian types that are not necessarily from different locations, suggesting that they were likely a locally adapted landrace population such as the one that still remains in the region today (Argent personal communication 3/19/21;

McGahern et al. 2006). Thus, local herds showed no disruption of natural regional herd structures and strongly suggest that tabun keeping was practiced as it is today in the valley. As a herd or resource-management system, tabun herding involved the least amount of human intervention, did not control breeding, and only required pastoralists to move horses to where food was at different times of the year (

Argent 2010, p. 90ff).

Excavators agree that the Pazyryk horses were pastured in the low, well-watered fields of the Ursal and Karakol Valleys in the Ongudai district in central Altai and along the Chuya River valley well within the Pazyryk Culture territory (

Argent 2010;

Rudenko 1970, p. 57), moving to higher elevations seasonally (

Samashev 2012, p. 40;

Chlachula 2018, pp. 14–15). They suggest animal rearing, with a predominance of horses, was the main component of the economic life of the inhabitants there, and that was predetermined by the specifics of the local ecosystem (

Samashev 2012, p. 40). Various communities in the Chyua and Ongudai Valleys must have supplied horses to their immediate neighbors, but also perhaps beyond where pastures were not so abundant, and the animals may not have been so elegant. This system was, therefore, a local endeavor that required no external intervention to maintain and allowed for the animals to be handled and managed locally as part of the base economy, including for trade. The location of the Pazyrykians, therefore, depended on and required the continuation of this natural breeding pattern built on trust in the local environment to provide for the self-sufficiency and well-being of the community.

At Pazyryk and Berel, the horses and their tack are thought to have displayed signs of different life roles and regional as well as local proprietors, including notched ears and fancy headgear (

Rudenko 1970, pp. 117–19;

Francfort et al. 2006;

Argent 2010;

Rubinson 2012, p. 88, fn 60). In light of the number of horses found in the richer burials, the horse totals killed likely represent higher status or were a graphic display of the power over the network of affiliations that the deceased had controlled. It is clear that horses were a sign of power, allegiance, and wealth among the leaders of these groups, but perhaps even beyond as a sign of their group alliances when coming into contact with outsiders for whatever reason including conflict.

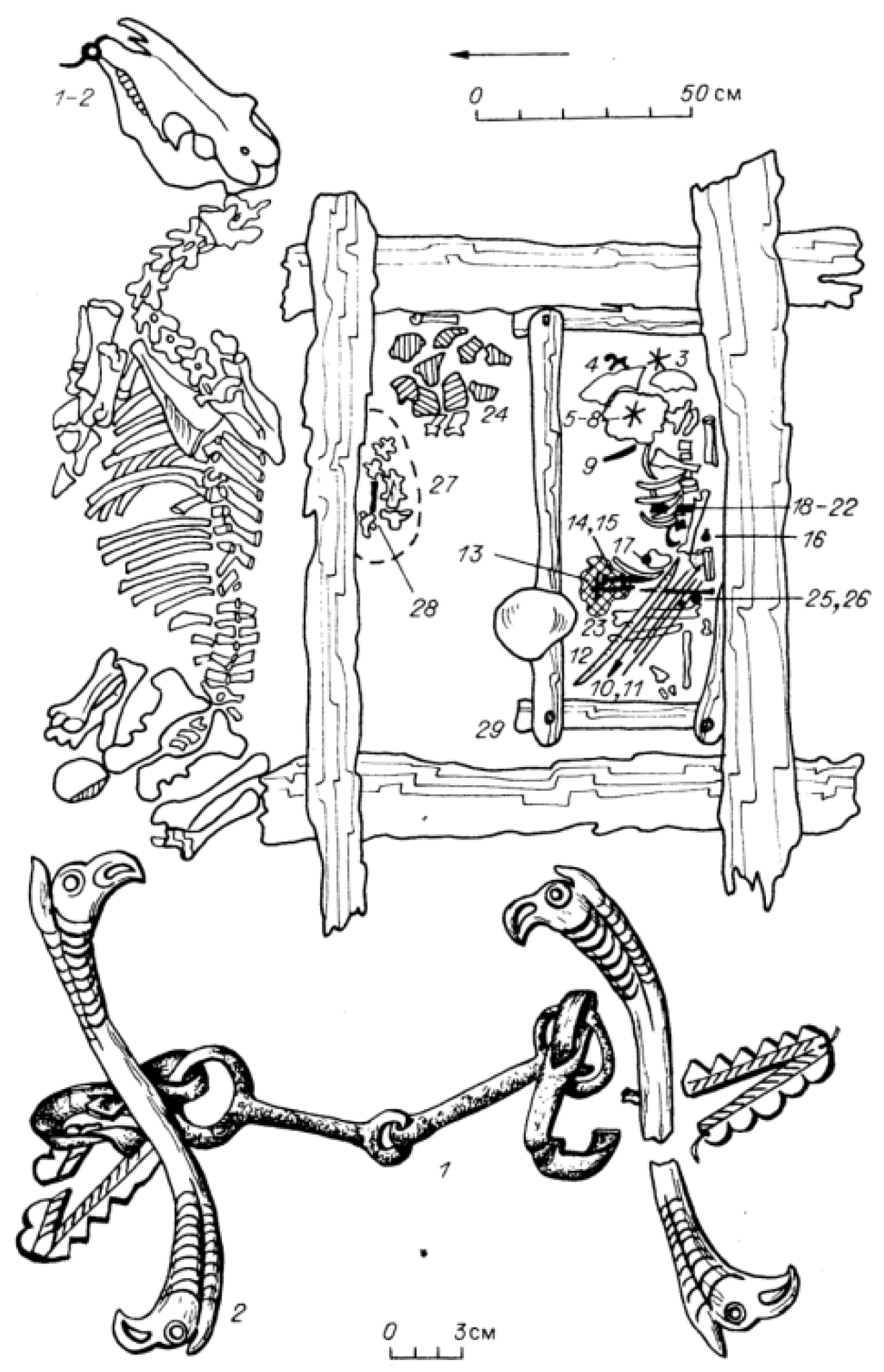

Among those less well-embellished smaller burials, horses were also found sacrificed together with decorative tack (

Figure 3, plan and 1–2). For example, among the kurgan burials at Yustyd excavated by Kubarev, 18 contained horses (43% of all excavated). A total of 32 horses were found, mostly only one or two in a grave, generally corresponding with the number of human individuals (one or two) who were buried with them. Exceptionally, there were, in one case, three horses, which Kubarev ascribes to the higher status of the individual buried with them (

Kubarev 1991, p. 25). Considering the numbers of horses found in the richer burials of Pazyryk and Berel, it is likely that the number of horses killed for burial correlated to social status, whether those horses all belonged to the deceased and were killed so no one else could ride them (

Argent 2010) or were a graphic display of the power of the network of affiliation that the deceased had controlled. It should be noted that horses were found in burials of both men and women at all social levels and with children in some burials excavated by Kubarev, as well as Pazyryk kurgan 6, where a woman and child were accompanied by three horses.

Among those of lesser status in the Pazyryk community were the herders, likely craftworkers and traders, as well as the ready corps of mounted warriors should the need arise (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022, pp. 26–101). Although weapons and occasional evidence of shields are found in these tombs (

Hanks 2012, p. 101), little physical trauma is recorded.

5 In their tombs, prominence was given to the horse through sacrifice and the inclusion of small figurines of horses that were very likely mountings for headdresses. At the very least, those images also acted as a marker of lifestyle, reverence and respect for the animal, and a group emblem of belonging (

Figure 3, [4–8]).

The burials of those of lesser status that Kubarev excavated contained men, women, and children. For example, of the 60 people buried in 40 kurgans at Ulandryk, 65% were women and children and only 35% were male. Their ratio in each burial and cemetery differed, as can be seen in the data from Ulandryk II, where of the 11 kurgans, only one contained a male; the others were women and children. In contrast, at the cemetery Ulandryk III, 86% of the deceased were male (six individuals) and the rest were women; there were no children (

Kubarev 1987, p. 23). Among the elite and mid-level Pazyryk burials in the Chuya valley, only Kurgan 6 at Pazyryk contained a child, and there were more deceased males than females buried. In the Ulandryk cemeteries, 55% of the total kurgans excavated, that is, 23 kurgans, contained a total of 40 horses. Moreover, 83% of the kurgans containing horses contained either one or two animals, which generally corresponded to the number of people in the burial. Four kurgans (17%) contained three horses, which reflected the higher status of the individuals (

Kubarev 1987, p. 16). The horses that have been studied in Pazyryk Culture burials are all males and mostly, if not all, gelded. The majority of the horses were older. Even in Mongolia where some killed were young, most were older than 16 years; of the 101 horses studied by Lepetz and his team from Mongolia and Berel, two-thirds were over 16 years old. The horses at Pazyryk itself and Berel were larger than the horses found in the Mongolian Pazyryk burials, which we might assume is also the case for Ulandryk and the other burials excavated by Kubarev (

Lepetz et al. 2020;

Kubarev 1987, p. 108).

4. Animal Imagery as Markers of Social Order

Certain aspects of the Pazyrykians’ lives were emphasized in burial: The value of strength envisioned in wild animals; the power of force as repeatedly embodied in weapons; and the influential role of knowledge of the outside world marked in graves with items of exotic manufacture or design among the elites. Wild animals, not the domesticated sheep that were present as food offerings in tombs (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 184), ornamented and animated the humans and horses and likely documented a mystified role in the lives and deaths of these folk. Evidently, the animal kingdom was part of their livelihood and economy, and although the circumstances varied according to the settled or mobile portions of their lives, animals were essential.

Shared artifact types and emblems were apparent in most tombs

6, as was the choice of subjects for representation on ordinary and funerary materials. They consistently included single naturalistic images of recognizable wild animals and/or of interactions between two or more animals

7, and most of the recognizable fauna represented on the artifacts roamed this area long before human beings either hunted or tamed them. The animals represented are ones that could be hunted locally: Doe, kulan or wild asses, gazelle, stags, rams, mountain goats, argali (wild) sheep, and occasionally an impressively large fish, a freshwater sturgeon, such as the one tattooed on the right calf of the man in kurgan 2 at Pazyryk (

Rudenko 1970: Figure 121) and depicted on felt saddle pendants in kurgan 1 (

Rudenko 1970: Figure 121, Pl. 167, D). They also included animal predators: Bears, wolves, tigers, panthers, leopards, boar, and lynxes. There are no representations of kindly songbirds in this repertoire; rather, vultures and ferocious fowl including raptors used for falconry were favored as they are on the steppe today. Domesticates include horses and oxen, familiar working animals, although there are no representations of domestic sheep. When fantastic or composite beasts such as the dragon or griffin were depicted, they most often were borrowed from the settled peoples to their east and/or west (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022, pp. 76–82) (

Figure 4).

5. Horses or Deer or Both?

The query here is stimulated by the presence of small wooden animals that adorned the headgear of men, women, and children buried at sites in the Russian Altai that belonged to the more ordinary individuals of the Pazyryk Culture (e.g.,

Figure 5, [4–8]). These wooden images, in the case of the horses, ranged in height from miniatures at 2.5–4 cm to larger ones at 7–8 cm, with the larger ones found on the headgear of adult males and females and the smaller ones associated with children (

Kubarev 1987, p. 106). Although such images were found at all of the sites reported by

Kubarev (

1987,

1991,

1992), our discussion here will focus on the sites of Ulandryk, Tashanta, and Yustyd (e.g.,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6b) as reported in the 1987 and 1991 volumes, although supplemented by data from other sites; the wooden images, as well as the other ornaments, decorations, tools, and weapons in all the burials reported by Kubarev, are similar and consistent from one site to another (

Figure 6).

It is likely that the ancestors of the creatures adorning the headgear of these more common folk lie in the type of decoration of the headgear of the elite individuals buried in Arzhan II, grave 5, a man and a woman whose burial was the impetus for the massive burial complex that dates to the 7th century BCE.

8 As reconstructed in detail from the undisturbed burial remains, the male wore a head covering of leather with hanging earflaps. It was topped with gold ornaments, including four flat images of horses with their legs tucked underneath, and ear, eye, mouth, and nostril, and a crescent shape at the neck in enamel together with a standing stag, also flat, although with a pair of antlers flowing from the head and with eyes, nostrils, mouth, and crescent at the neck in enamel on both sides, at the top of the headdress (

Čugunov et al. 2010, p. 212, Figure 225, Pl. 1, Pl. 2 [1–3], Pl. 33 [1,5]). In the hypothetical reconstruction of the woman’s headdress, a tall conical hat of red-colored leather (?) was decorated with gold ornaments that include two flat horses with tucked-under legs, with eyes, nostrils, and mouth engraved on both sides and a very tall pin with various animals engraved on the shaft topped by a standing three-dimensional stag with engraved decoration and a pair of flowing antlers (

Čugunov et al. 2010, pp. 213–14, Figure 226, Pl. 54 [1–2], Pl. 56, Pl. 73 [1–3], Pl. 74 [2]). In both cases, the stags and horses are clearly recognizable as such

9. In the case of the elements of the male headdress, although the horses and stag share similar enameled cells for the eye, mouth, nostril, and crescent at the neck, as well as the treatment of legs and body shape, they are easily distinguished by the antlers on the stag and the manes on the horses, as well as the lengths of the tails, namely, short on the stag and long on the horses. Additionally, the stag’s head is raised while the horse’s snout is lowered. The variation of head position is also apparent on the pins of the female headdress, where the horses face down while the stags, and most other animals, have heads parallel to the ground or raised (

Čugunov et al. 2010: Pls. 55–56).

At the site of Pazyryk itself, there is a variety of headgear on the deceased. In kurgan 2, among the finds, Rudenko cites “part of a man’s pointed felt cap” and a woman’s headdress of colt’s fur decorated with leather cut-outs of rhombs and cocks (

Rudenko 1970, p. 317). Additionally found in that burial were wooden stags with leather antlers standing on fluted balls (

Rudenko 1970: Pl. 137, G, H) and carved wood and leather compositions of griffins and deer (

Rudenko 1970: Pl. 141, Pl. 142, D). The former is now recognized as hairpins, two of which are covered with gold foil, and the other pair, which might have been covered with tin foil (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 117–18, Figure 102, Pl. 42). These stags, similar to those from Arzhan II, have heads parallel to the ground. As Simpson and Pankova note, following Kubarev, these Pazyryk pins recall those that are found in the “commoner graves” at Ulandryk and in the Sailiungem region.

10 They suggest that the total of four pins might have been worn all at once by the woman buried in Pazyryk Kurgan 2 since she was a member of the high elite, while those in the more everyday burials had single pins (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 118). It is a proposal worth considering in light of the headdress ornaments of the woman in burial 5 from Arzhan II. She had two long gold pins on her headdress, although only one of them was topped by a standing stag.

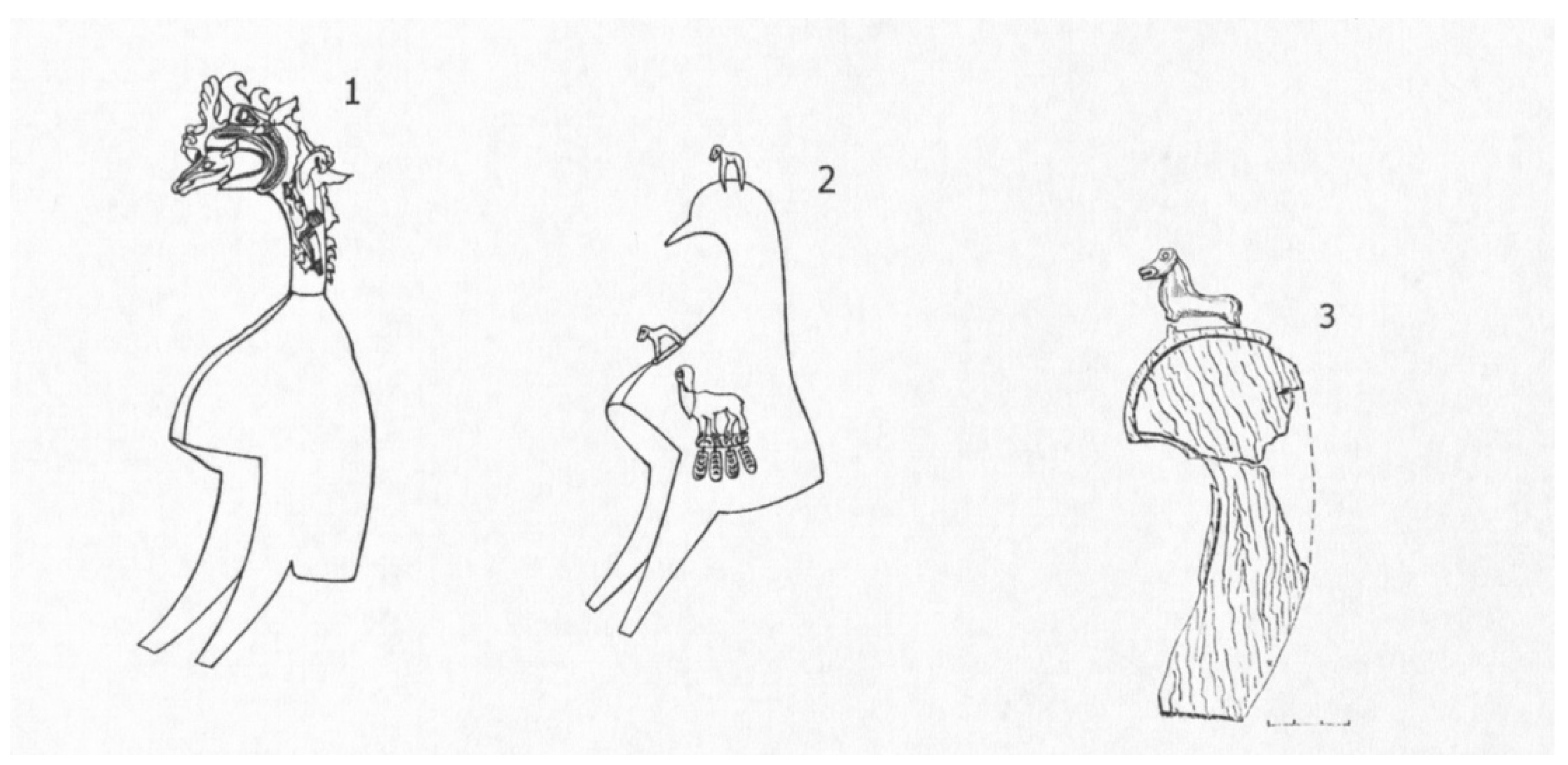

The headdress of the male from Pazyryk kurgan 2 has recently been reconstructed and is composed of the three elaborate carved wood and leather pieces excavated by Rudenko, although he did not identify them as elements of a headdress (

Rudenko 1970: Pl. 136 [G, J]; Pl. 139 [L]; Pl. 141). As reconstructed, the cap was crowned with a tall image of a griffin or eagle holding a stag head in its beak. Attached to the sides of the cap were images of a bird of prey attacking a stag with elaborate antlers (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 112–13) (

Figure 7, #1).

Stepanova noted that on the Ukok Plateau and in Mongolia, excavations of lesser elite males exposed headdresses with related ornaments including eagles and fantastic hoofed animals, found at the sites of Ak-Alakha-1, kurgan 1, Verkh-Kal’dzhin 2, kurgan 3 (

Figure 7 [2]), and Olon-Kurin-Gol 10, kurgan 1 (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 112 and see

Polosmak 2001, pp. 155–60, 180 and

Molodin et al. 2016: Figure 12 and

Turbat and Tseveendorj 2016: Figures 9 and 10). What is notable in the Ukok Plateau cases is that all of the hooved creatures are shown reconstructed with ibex horns, a point to be addressed below. In contrast to the reconstructions of the male headdresses, the headdress reconstruction of the female from Kurgan 1, Ak-Alakha-3, also on the Ukok plateau, shows a deer figure with stag antlers

11 standing on a ball while the deer lower down on the headdress has its legs folded underneath its body and ibex horns (Stepanova in

Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 118;

Polosmak 2001, pp. 143–51, especially reconstruction III).

Kubarev (

1987, p. 111) states that what distinguishes the wooden headgear ornaments, both horse and deer, of the ordinary Pazyrykians from those of the top and mid-level elites is that they have the quality of folk art. It is indeed true that they are not modeled in as realistic a way as the stag pins from Pazyryk Kurgan 2 or with the kind of detail of the elements of the headdress of the male in that burial, and they are less detailed than the few more elaborate carved wooden pieces in these simpler burials, such as the ends of what might be a neck ornament in the form of snow leopards from Ulandryk I Kurgan 12 (

Kubarev 1987, p. 164, Pl. XXVIII,10) and the diadem from Kurgan 1, Ulandryk IV that features a symmetrical composition of stags with flowing antlers followed by felines adorned with raptor heads (

Kubarev 1987, p. 185, Pl. LXIX, 9). In fact, we might consider these and the few other elaborate pieces as gifts to the non-elites from those to whom they owed allegiance. Of course what we see preserved are the wooden pieces, with only occasionally one of the leather inserts, such as the tail of a horse, retrieved (

Kubarev 1991: Pl. LI, 4) (

Figure 5, [4]), as well as an ibex horn made of leather covered with gold foil from Ulandryk IV, kurgan 2 (

Kubarev 1987: Pl. LXXIV [26]), where it is associated with the figure of a goat with what

Kubarev (

1987, p. 113) called “syncretic” characteristics of a horse. Another ibex horn, of gold foil, was found associated with a horse figurine from Yustyd XII, kurgan 23 (

Kubarev 1991: Pl. LII [13,19]) and also one of leather (?) from Yustyd XII, kurgan 19 (Pl. XLV [12]), associated with a wooden horse head (

Figure 6b [12]). Kubarev mentions holes for inserted horns, ears, tails, and phalluses and suggests that the fact that the hole for the tail and phallus was a single channel that allowed for a single leather insert had a spiritual significance. He notes that, in rare cases, the horse figurines had slots for wings on their backs.

12 The figures of horses and deer were apparently finished with coverings of gold leaf and touches of cinnabar coloring (

Kubarev 1987, pp. 107–8).

13 Crafting Horses and Deer

The little wooden horses (or deer) crafted for placement on the crest and sides of headgear found at the head of the deceased in many tombs, especially in the eastern Chuya Valley sites of Yustyd, the Sailiungem area, and Ulandryk (

Kubarev 1991,

1992, and

1987, respectively), deserve special notice. There is some question about their attribution as horses or deer. For Kubarev, the primary distinction between horses and deer is that deer are distinguished by having open mouths surrounded by a convex rim and the convex eye is teardrop-shaped while the horses have round eyes (

Kubarev 1987, p. 104 and see

Kubarev 1991: Figure 24 [5,6]). In some cases, deer are also distinguished by what he terms an under-cervical mane, which can be depicted in two different ways (

Kubarev 1987: Figure 41; Pls. XXVII [9]; LVIII [4]; LXXVII [7], XCII [11]), a treatment that sits at the neck, which differs from the beard on the chin, on animals he identifies as sheep/goat (see

Kubarev 1987: Figure 44).

14 Further, he describes all animals that are carved in bas-relief, often with heads carved separately and inserted at approximately right angles, as deer, while identifying animals carved in the round as horses (

Kubarev 1991, p. 117) (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6b). He also suggests that some deer at Ulandryk have narrow, elongated bodies that are derived from the deer images that appear on deer stones, while the horses have short bodies with short stature since they are of a local “Mongolian” breed (

Kubarev 1987, pp. 104, 108–9)

15.

In his attributions, Kubarev does not discuss the profiles of the snouts of the animals. In nature, deer have more narrow muzzles than horses, although animals with such narrow muzzles are often called horses in his calculations. For example, in Kurgan 19 at Yustyd XII, Kubarev identified two such wooden creatures with four holes in their heads as deer (

Kubarev 1991: Pls. XLIV and XLV:10, 11), while he identified two others with narrow muzzles as horses, one with “plug-in horns” (

Kubarev 1991: Pls. XLIV and XLV: 9, 12) (

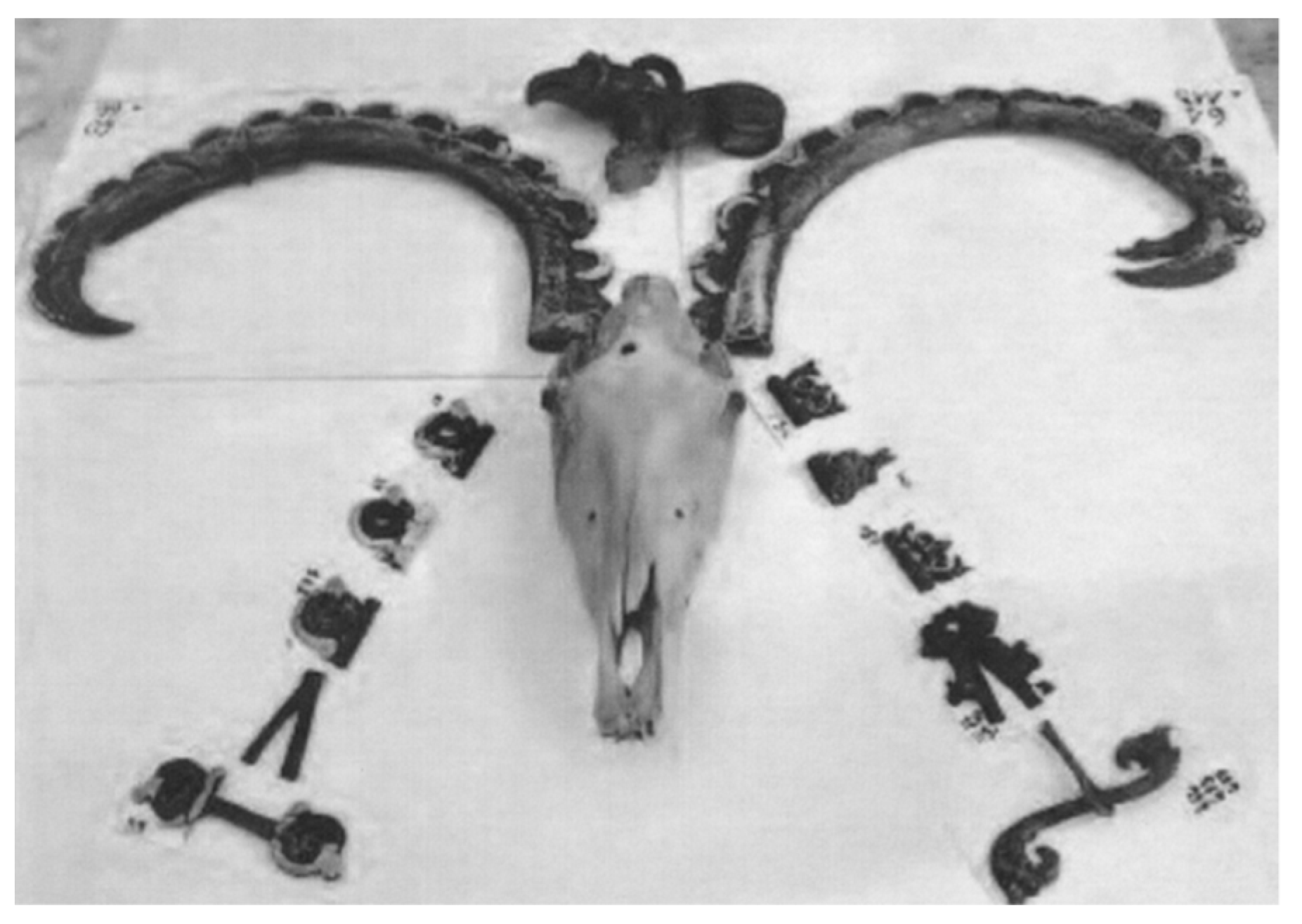

Figure 6). A few actual sacrificed horses in the larger tombs at Pazyryk were transformed from equine to cervid by masks (

Figure 8).

16 That transformation suggests that the small wooden animals depicted were also transformed from equine to cervid, although Kubarev’s choice of the word “horn” implies transformation from equine to

Capra, both of which are implied by the archaeological evidence.

17 According to Esther Jacobson, these smaller examples would be meant to capture a conversion or a metamorphic process (

Jacobson 1993;

2015, p. 301). In the cases at Yustyd, Ulandryk (

Kubarev 1987, pp. 106–12; and, for example, Ulandryk II, Kurgan 5, Pls. XLI-XLII), and the Sailiungem area (for example Kurgan 18, Barburgazy I,

Kubarev 1992: Pl. XXIII), a transformation may simply be indicated by attaching horns to figures that are horses or horse-like, as the example preserved from Yustyd exhibits (

Figure 6).

Most human headgear found in burials in the region had attached images of animals including some that are not antlered such as the deer-like representation reconstructed with the horns of a mountain goat/ibex on the headdress of the woman in kurgan 1 at Ak-Alakha 3 (

Polosmak 1998, p. 148;

Polosmak 2001, p. 143).

18 Such representations of animals on top of the head of the deceased signal to Jacobson the creation of a vertical axis that was coextensive with the head or body of a human being and/or the head or body of a horse (

Jacobson 1993, p. 57;

Jacobson 2015, p. 290). This creates, for her, a spatial hierarchy that stands for and confirms the role of the horse as central to thinking among the Pazyrykians about the transition from death to an afterlife.

19The little deer/horse images are, of course, not ferocious animals that might have bestowed the aspect of brute power to the wearer, but could they have triggered the notion of transformation as Jacobson suggests? As domesticates, horses were found nearly ubiquitously in those graves, and at the very least must have recalled both their essential function to their this-worldly role for the mounted warrior and herder and to the base economy as a trade animal. Apparently, though, they were also emblematic for community members who worked directly with the animals as the images are less frequently found in the elite and mid-elite tombs at Pazyryk, Berel, and Ak-Alakha where less direct involvement with the rearing and management of the horses took place and where they likely knew horses primarily as mounts. The prevalence of animal combat, on the other hand, represented on all sorts of items including clothing, saw imagery playing a different role—that of protection embodied in raw animal power displayed (

Figure 4).

6. A Further Excursion into the Identification of Horns and Antlers

As noted above, the four hairpins from Pazyryk kurgan 2 are topped with wooden deer figures with flamboyant leather antlers. One pair is covered with gold foil and the others possibly with tin foil (

Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 117–18). There are two horses buried with masks that have stag antlers at Pazyryk, one from Kurgan 1, dating toward the beginning of the sequence, and the other from Kurgan 5, at the end of the late Pazyryk phase. In the earlier example, the antlers are fitted directly on the covering of the horse head (

Figure 8, right); in the other, the horse head is topped with a wooden sculpture of a stag neck and head with leather antlers (

Ochir-Goryaeva 2020: Figure 2).

20 Esther Jacobson notes that the horse mask on horse 10 from Pazyryk Kurgan 1 is the only surviving example of a true transformation of the horse to stag, while it also conveys an attack by a feline on a stag also suggested by Gala Argent (

Jacobson 2015, pp. 293–94;

Argent 2010, pp. 157–74).

In the excavations at Ak-Alakha-3, Kurgan 1 was the burial of a woman whose remains were well preserved. Part of her headdress was a pin topped with a sculpture of a deer. The horns/antlers that adorned the head of the animal were apparently not preserved. In the initial publication, the animal is shown with the horns of a mountain goat/ibex (

Polosmak 1998, p. 149, Figure 11), the same horns as on the recumbent deer below at the bottom of the headdress. In a subsequent publication, the pin was reconstructed with the antlers of a stag (

Polosmak 2001: Reconstruction III, p. 143, Figure 98), while the recumbent deer retains the ibex horns.

21The general preference in reconstructions for ibex-type horns on the figures identified as both deer and horses can be seen in the headdresses of males preserved in excavations both on the Ukok plateau and in Pazyryk Culture burials in Mongolia (

Figure 7). Although the wooden pieces and the felt caps were preserved from the males buried in Kurgan 1, Ak-Alakha-1 and Verkh-Kal’dzhin-2, kurgan 3 on the Ukok plateau and at Kurgan 1, Olon-Kuriin-Gol 10 in Mongolia, none of the elements that adorned the heads of the animals were preserved (

Polosmak 2001, pp. 155–59, Pl. XIX, v, g;

Molodin et al. 2016, pp. 79–87). All of the animal figures, whether identified as horses or deer, are reconstructed with the same ibex horns (

Polosmak 2001: Reconstruction IV, p. 157;

Molodin et al. 2016, p. 50, reconstruction by Dimitri Pozdniakov). This reconstruction choice was possibly driven by the ibex horns on the winged horses that adorned the headdress of the individual buried at Issyk Kurgan in Kazakhstan that Kubarev had cited as a parallel (

Kubarev 1987, p. 109;

Chang 2006, p. 54, Pl. 55). Not only was that example well known and prestigious, but Kubarev had noted that in rare cases, the horse figures at Ulandryk had slots in their backs for the insertion of wings, also seen on the Issyk example (

Kubarev 1987, p. 108). Nevertheless, some remnants of antlers of gold have been retrieved from these commoner burials, for example, Kurgan 12, Ulandryk I, where a deer figure was found with golden antlers (

Kubarev 1987, pls. XXVI and XXVII, 9) and Kurgan 23, Yustyd XII (

Kubarev 1991, Pl. LII) in which kurgan fragments of golden antlers were found associated with a headdress (no. 21) in addition to a golden ibex horn associated with a horse figurine (nos. 19 and 13).

The ambiguity of distinction between the ibex horn and the antler existed within the Pazyryk culture before the burials that we have focused on here. Tuekta Kurgan 1 contained eight buried horses. It had been disturbed, and the elements of the horses’ masks were not found on the horses. Nevertheless, it seems that all eight horses had ibex horns on their masks, six of which closely mirrored in wood the appearance of curved horns with bumps on the horns semi-circular inserts, similar to the horns on some horses buried at Berel (

Figure 9). Two sets at Tuekta were distinctive. One set of inserts had small wooden standing lion figures on the bumps. The other set had inserts on the bumps made of deer skin that appear to be antlers together with an ear (

Ochir-Goryaeva 2020;

Busova 2015;

Rudenko 1960, Pls LXVIII-LXXII). So here, approximately a century before the appearance of the more easterly kurgan cemeteries of both the elites and commoners, stag antlers are placed on a horse mask, although in a more tangential situation than on the masks on the Pazyryk horses and are associated with the horse burials and not the headdress ornament of the deceased individual. It is tantalizing to consider the possibility that reflected in this horse headdress is early contact between the elites of the earlier phase of the Pazyryk Culture and the inhabitants of the eastern regions where good pastures may have begun to appear, which brought the Pazyrykians to choose their new territory, knowing that the horses would be well-fed and the Chinese market was within reach.

7. Spiritual Life and the Role of Horses/Deer

Since burial rites are ceremonial and most often solemn, we consider all the material as well as their placement in tombs as evidence of highly charged rites and values bestowed upon the dead. In most cases within the Pazyryk Culture, for instance, the heads of the deceased were laid toward the east and the feet to the west where the sun sets. We also know that the burials at Pazyryk took place from late spring to autumn when the ground was not frozen and that the bodies of the high elites were embalmed and their skulls were trepanned. Mummification also took place at Berel. Preparation of the body was carefully conducted and the body was preserved since death was not seasonal as burials were, but beyond the practical aspect, the process must have been part of thinking about sending off the dead to the next life. This practice and the accumulated grave goods transmitted messages about preserving the external forms of life (the skeleton and flesh) surrounded by what seemingly were highly valued embodiments of the life lived. These burials marked a lifetime grounded in the Altai, but do they also document musing over how to recognize and reach the hereafter?

The presence of metal vessels filled with rocks that were placed near clusters of six rods bound with strips of birch bark, and in at least two incidences, covered with large hangings of felt or leather (

Rudenko 1970, p. 78), tell of a practice related by Herodotus (Herodotus, A, bk. iv, 73–75). In Kurgan 2, each vessel contained a small number of seeds of hemp (

Cannibus sativa L of the variety

C. rideralus Janisch) of a sort that was also found in leather flasks attached to one of the rods. Although this practice of heating stones in a cauldron also containing hemp seeds under a covering was viewed by Herodotus as a practice of ablution since, according to him, the Black Sea Scythians never bathed, Rudenko proposed that these smoking sets provided for purification rituals as well as for enjoyment in ordinary life. The hallucinogens were likely inhaled by both men and women since two sets of apparatus for smoking were found in Pazyryk Kurgan 2 of a man and a woman along with seeds of hemp and hart’s clover (

donnic) and at least the stems were found in the other burials (

Rudenko 1970, p. 285, Pl. 62). This apparatus appears only at Pazyryk so was likely a practice restricted to the upper elite, at least as associated with death. Actions and materials that presented individuals, or in the case of Pazyryk animals such as the elaborately adorned horses, as different from ordinary mortals, were performed to impress onlookers, but largely to suggest the otherworldliness of the actor (often a priest). This was most often achieved through dress, behavior, and secret ritual and is frequently associated with shamanistic practice (

Yatsenko 2017, pp. 233–42;

Hasanov 2017, pp. 228–42;

Gheorghiu et al. 2017;

Cunliffe 2019, pp. 273–74).

22 The practice of breathing the vapors of hallucinogenic hemp, the playing of stringed musical instruments such as the harp found in Kurgan 2, and one-sided drums known from Kurgans 2, 3, and 5 document a relatively high level of music making at Pazyryk (

Rudenko 1970, pp. 277–78;

Cunliffe 2019, pp. 227, 273) and are also reminiscent of shamanistic practices (

Rubinson 2002, p. 71). At the very least, the imagery and spectacle can be seen as apotropaic and having powers to ward off evil (

Rubinson 2012, p. 88).

23The deliberate prominence given to the preservation of hair and nails in the tombs in Pazyryk Kurgan 2, and in the tomb of the Ice Princess at Ak-Alakha 3 (Kurgan 1, burial 2), for instance, is evidence of animism according to

Rudenko (

1970, p. 287). Since both hair and nails, he states, continue to grow after death and do not decompose or diminish, they must be attributed to a display of the powerful life element

24. Along with the sacrifice of horses, mirrors, torques, and earrings, headgear and elaborate wigs and hair dressings with zoomorphic golden appliques as afforded females at Khankarinsky Dol in the northwestern Altai contemporary with Pazyryk (

Dashkovskij and Usova 2011, p. 83) and at Ak-Alakha 3, Kurgan 1, burial 2 (

Polosmak 2001;

Polosmak and Barkova 2005) were indicators of a person’s status and were added for the afterlife. The collection and specialized treatment of hair in death rituals must, at the very least, be imagined to follow a belief in the mystery and continuity of life into the next world.

All such amenities surrounded the body of the “Ice Princess.” Polosmak believes that the suffering of the princess, from cancer and ostomyletus and finally a fall from her horse, would have required treatment with herbs such as hemp. She imagines that the altered consciousness that such treatment provided would have allowed the Princess to have been perceived as in contact with the spirits, and therefore, a spirit leader (

Liesowska 2014). Ritual leaders must have existed if even to manage ceremonial activity. If that were the role of the leadership buried at Pazyryk, it is difficult to determine with the present evidence.

The possibility that the objects and their décor represented spiritualized ideas is suggested by many who are interested in the “Animal Style” (

Jettmar 1967, pp. 89–120; 131–2; 137;

Bunker et al. 1970, pp. 61–63;

Jacobson 1993,

2015;

Stümpel 2021;

Andreeva 2021, among many others). For example, Jettmar argued that burial displays such as vessels, scoops, knives, and vases and including the remains of food found at Pazyryk Kurgan 2 suggested that feasting was part of the religious celebration (

Jettmar 1967, p. 95). He goes on to conclude that funerals commended accomplishment among the elite and that tombs represented gradated symbols of prestige such as the deposition of varying numbers of horses sacrificed with the dead as we have suggested above with the benefit of excavated material from commoner tombs not known to Jettmar. He thought of them as symbols of rank attained through acts of courage in battle (

Jettmar 1967, p. 131) and argued that, overall, the burial displays, including hemp-burning apparatus found in Kurgan 2 at Pazyryk, were indicators of religious ceremonies where communication with the beyond was encouraged and accomplished. Such displays made clear to him that life both before and after death was governed by rank and perhaps privileged access to another level of consciousness (

Jettmar 1967, p. 137).

With regard to the animal representations per se, Jettmar thought of them as representing lower-ranking supernatural powers believed to confer blessings as seen in the “lavish tattooing of the man in Kurgan II at Pazyryk” (

Jettmar 1967, p. 138) and acknowledges that even though the burials were ritualized, deciphering meanings of the images beyond their functioning as markers is nearly impossible. He does suggest that the analysis of change in the visual form of animals to a more stylized (“unimaginative”) representation, however, can be read as an indicator of change in ritual use and a later date (

Jettmar 1967, p. 139). This sort of reasoning about the form and meaning of visual features has continued, especially in the research of Esther Jacobson, which largely focused on stag and horse imagery (1995; 2015).

8. Finally, the Stag, the Mountain Goat, and the Horse

Perhaps the most speculated-on issue in relation to a possible belief system associated with the Pazyryk group and other pastoral peoples is their preference for “animal style” décor. Prevalent is the notion that animals in the art of the pastoralists represent a kind of totemism or mythological representation of bearers of qualities such as ferocity or sensitivity, although Rudenko argued strenuously that that was not the case (

Rudenko 1970, p. 287ff). Instead, he suggests that these animals, both wild and domesticates, were intimates of the societies who bore them and had a decorative and/or protective function and thus they appear as tattoos.

Central to Esther Jacobson’s interpretation is the formal visual analysis of the image of the deer as it appeared in the iconography of the earlier occupants of South Siberia (1995). By examining these formal features as indicative of symbolic structures, she has developed interpretative theories regarding early “nomadic” cosmology. The reconstruction of meanings embedded in the deer image, she argues, carried her investigation back to rock carvings, paintings, and monolithic stelae of South Siberia and northern Central Asia, from the Neolithic period through the early Iron Age. The succession of images dominating that artistic tradition is considered against the background of cultures that evolved from hunting and fishing to a dependency on livestock (2015) and that would include the Pazyryk peoples. She traces the path from the images on earlier rock art in Mongolia through a close comparison of stag imagery on the male and female headdresses from Arzhan II, burial 5 to the ornamentation of horses and humans in death at all levels of the Pazyryk Culture (

Jacobson 2015, pp. 270–302). This trajectory underscores the cultural roots in Siberia of at least some of the participants of this easterly expression of the Pazyryk Culture.

Bryan Hanks (

2010, pp. 180–81). underscores the development of this imagery with the growth of mounted warfare in the first millennium BCE.

Jacobson goes on to suggest that there was a symbolizing order among the burial practices and visual imagery dedicated to animals that foregrounded predation, transformation, and axial order (

Jacobson 1993, p. 57ff). She cites the mask-wearing of the horses and the creation of composite animal imagery as evidence of belief in the transformation or metamorphosis from this world to the spirit world and axial placement of horses and trappings and symmetrical or mirror-image spatial order as confirmation of the centrality of animals, especially the horse, in their lives. She notes that the predation is not complete since the animals do not die, and that suggests to her that transformation or continuity is sought after, and not finality. She claims that the role of axiality, and at the center of that, the Deer Goddess, could be thought of in a similar fashion—that is, balance, stability, and continuity were paramount and behind this symbolism. In this sense, her thinking includes the little wooden horse/deer finials at the apex of caps found in graves of all sub-groups and locations across the region discussed above.

In all, however, the objects, imagery, and treatments of the body point to an attempt to capture and maintain that which was most important for the livelihood of the community—family and group bonds, respect for the wild animal kingdom and their herds, protection and bodily health of the deceased, and status within and perhaps outside of the local group. Displaying those notions must have guided the selection of images and signaled their worth in order to maintain, validate, and project their bonds in the present and into the future. In that sense, the other world was clearly invoked throughout the burial displays and preparation of the necessary accouterments for funerary and burial rituals that occupied a huge amount of the effort and focus of attention of the residents of the Chuya Valley. Maintaining their social order and ritual schedule required an ordered society that included the efforts of many and several levels of responsibility and authority, including men, women, and children (

Linduff and Rubinson 2022, pp. 98–100).

The fact that the animals decorating the headdresses of the commoners and some mid-level individuals of the Pazyryk Culture, in contrast to those preserved on the elites of burial 5 at Arzhan II, are often ambiguous in interpretation, sometimes expressly deer, sometimes horses, sometimes neither, and sometimes with horns of mountain goats or antlers of stags, even if formally a horse shape. This raises the question of the roles of both wild and domestic creatures in the lives of the Pazyrykians. We know that the raising and trading of horses formed the basis of their economic livelihood and distinguished them from their distant neighbors and/or trade partners, and that wild animals such as deer and mountain goats were hunted and their by-products were incorporated into clothing and other material creations that enhanced and were maintained during their daily lives. Is it possible that since both the wild and domestic animals were so critical to their existence that in the conceptual minds of the artists who created the images, they were interchangeable? Or that combining the mountain goat (ibex) horns, which were also found on horses at Berel at the western extent of the Pazyryk Culture, and the antlers of the stag that has roots in Siberia and are unique to the imagery in the eastern expression of the Pazyryk Culture (with the one exception at Tuekta) with the animal that they raised, lived with, traded, and took with them to the grave expressed an encyclopedic world view of a culture that thrived for a short time but left a vivid impression for the afterlife and to this day through their rich material remains?

We have endeavored to understand this ambiguity in presentation despite the challenges of working within a non-literature culture exclusively through available mortuary remains. This project thus required extracting our suggested conclusions from the fragmentary materials preserved. We used the visual evidence together with what can be determined about the economy and lifeways of the Pazyryk peoples to suggest that the visual ambiguity of the small wooden animals that decorated the headdresses of some of the common folk was more meaningful directly to their lives than the earlier more realistic representations. This ambiguity was expressed in a more literal way through the headdresses of the buried horses and the representations of the same on some bodies of the deceased elites, making it clear that these co-joined creatures were real to the Pazyryk Culture peoples.