Abstract

The article focuses on two parafictional figures created by Israeli artists at about the same time in the early 2000s: Oreet Ashery’s Marcus Fisher and Roee Rosen’s Justine Frank. Through a close reading of these case studies, I examine the phenomenon of parafictional characters as extreme cases of voice appropriation. Against the background of rising international concern with cultural appropriation, and of the Israeli sociopolitical context characterized by a multiplicity of often conflicting identities, I argue that such appropriation is, in fact, a basic aesthetic procedure. Using Hannah Arendt’s reading of Immanuel Kant’s aesthetic judgment as political judgment, and her articulation of an “enlarged mentality” as necessary for both aesthetic and political thinking, the article demonstrates how the ability to imagine a position different from your own is inherent for aesthetic representation as well as reception.

1. Introduction

In the early 2000s, two Israeli artists, one in Tel Aviv and the other in London, created imaginary personas.1 Oreet Ashery (b. 1966, Jerusalem), London-based Jewish secular female artist, embodied the figure of Marcus Fisher, a perplexed young Jewish Orthodox man who, like her at the time, studied art and engaged in spontaneous performances. At about the same time, Israeli-American Jewish secular male artist Roee Rosen (b. 1963, Rehovot) laboriously constructed the life and work of Justine Frank (1900–1943), a Belgian female artist who was associated with the Surrealist movement in Paris of the late 1920s and early 1930s and who immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in 1934. The identities of these four artists are detailed not merely for the sake of biographic facticity. Rather, the discrepancy between the real artists’ identities and those of their alter egos can lead to accusing both of cultural appropriation, especially in today’s heated discussions regarding its legitimacy, legality, and possible harms, specifically when involving artistic creation.

In recent years, cultural appropriation has become a catchphrase, applied in relation to such diverse incidents as the demand to remove from the 2017 Whitney Biennial exhibition and to further destroy Dana Schutz’ painting Open Casket, after the White painter had been accused of appropriating a symbol of African-American resistance—the defaced body of Emmett Till, lynched in Mississippi in 1955; the banning of White Montreal comic Zach Poitras from a comedy club on account of his dreadlocks in 2019 (Giguere 2019); the stepping down of a celebrated musicology professor at the University of Michigan for screening the film Othello (Stuart Burge, 1965), which included blackfacing, in 2021 (Schuessler 2021); and most recently, the accusation of fashion chain Ralph Lauren of plagiarism and cultural appropriation by the wife of Mexico’s President, Beatriz Gutiérrez, for selling an item copying indigenous Mexican designs, following which the company published an official apology (FitGerald 2022).

What I consider the spiraling out of control of the use and misuse of the term cultural appropriation does not belittle the importance and complexity of this phenomenon. It is challenging to define, as both “culture” and “appropriation” are fluid, contextual, and relative terms. Broadly, cultural appropriation can be defined as the possession, adoption, or use of artifacts, symbols, styles, or identities identified with one culture by members of another. This general definition does not address the power relations evident in the direction of appropriation—a fact relevant to our subsequent discussion of the two case studies. However, the debates around the subject, mainly since the 1990s, have been primarily concerned with the cultural appropriation of marginalized and oppressed cultures by members of dominant cultures, especially of Native- and African-Americans by European-Americans; of Aboriginal members by European Australians; and of First Nations societies by Euro-Canadians.

Cultural appropriation may take many forms. James O. Young (2008), who has written extensively about cultural appropriation in the arts, offers a useful ontological typology, based on the kind of thing appropriated. He divides the phenomenon into tangible or object appropriation, and non-tangible appropriation.2 The former is mainly concerned with looted art and the possession of archeological findings from non-Western countries by Western institutions. The latter is subdivided into content, style, motif, and subject appropriation. The current article will deal exclusively with the latter—the appropriation of subject matters, also called voice appropriation, especially when members of one culture represent the lives of members of another in the first person.3

Voice appropriation is of interest to me because on one hand, it can be seen as the most extreme case of cultural appropriation—taking on external voices, representing another, or thinking as if you were someone else. On the other hand, I find it the least objectionable type of cultural appropriation, because, as argued below, the procedures mentioned above are all inherent to aesthetic creation and its experience. In turn, the artistic use of pseudonyms, the creation of alter egos, and the invention of fictive personas can be thought of as extreme cases of voice appropriation, especially when these identities belong to gender, race, or culture groups different from and politically subordinated to those of the artist.

When such fictive personas are encountered outside the framing of an artwork, as if they were real personas, their appropriation is further complicated. At this point, it is crucial to distinguish between fictional and parafictional characters. While the former remain within their confined artistic bubbles and their fictive status is well known, the latter are perceived by certain spectators, and for different periods, as real people (Lambert-Beatty 2009).4

Both Fisher and Frank initially operated as parafictions. Fisher came to life in spontaneous, performative street interventions, in which passersby were not aware of him being an artwork (I will later refer to their reactions). Ashery admits she did not initially think of Fisher as an artwork, but rather experimented with his persona as part of her queer lifestyle and cross-dressing practice.5 As for Frank, in the first group shows in which her works were included, as well as in some later solo shows, and in the various texts Rosen published about her work, she was presented as a real artist, while Rosen was presented as a curator, guest curator, or scholar who discovered her forgotten oeuvre. However, Rosen, as well as Ashery, were not interested in deluding their spectators. In her performances as Fisher, Ashery did not change her voice or mannerism, because she was not interested in acting, mocking, or masquerading (Ashery quoted in Rowe 2013, p. 249). Rosen did not “age” the pages of Frank’s drawings, and many of the texts about Frank and the publications accompanying her exhibitions included footnotes that revealed her imaginary status. Nonetheless, throughout the years, some spectators, as well as artworld insiders, perceived Frank as real.6

Both fictional and parafictional characters hold implications related to voice appropriation because, as mentioned, they distinctively take the voice of another. But parafictional characters take such an appropriation to the extreme, because they exist in the real world, their appropriative element is often concealed, and they may involve deception to various degrees, thus charging their viewing experience with feelings of shame, anger, and frustration. However, I argue that the hybrid existence of parafictional characters and the unique viewing experience they foster are exactly what charges these characters with complexity and critical impetus.

For example, in a newspaper review of a group show in which works by Frank were first exhibited,7 journalist Dana Gilerman (2000a) mentioned that the most “interesting and surprising part of the show was the discovery of the forgotten artist Justine Frank”. In an article published a few days later, titled “Who Is Justine Frank Really? …”, Gilerman publicly shared her experience of understanding that Frank was not real:

The moment the manipulation is revealed brings with it a sense of resentment. The excitement with the works and with the revelation of Frank turns to insult. But the anger, in this case, is very soon replaced by a sense that the fictive character not only did not evaporate, but, surprisingly, kept on existing—thanks to the meticulous tapestry work weaved by Rosen.(Gilerman 2000b).

The introduction of parafictional personas into real life and the shift in the spectators’ understanding of them from real to fictive intensify both the artists’ and the spectators’ ability to imagine other positions, meaning to become implicit in a positive kind of voice appropriation. More than flesh and blood representations, parafictional personas bring forth, as well as complicate, the crucial difference between representation and appropriation, which, I argue, is essential to cultural appropriation in the arts.

Relatively few philosophical discussions, specifically in the field of aesthetics, have addressed cultural appropriation (Young 2008; Hatala Matthes 2016).8 Young’s (Young 2008; Young and Brunk 2009) is the most comprehensive account. He is especially concerned with thinking about cultural appropriation in light of ethics, but also applies art-historical and aesthetic theories in his unpacking of the phenomenon’s legitimacy. I would like to deepen the aesthetic discussion of cultural appropriation in the hope of demonstrating how voice appropriation is an inherent procedure of aesthetic representation, and, as such, is not only legitimate, but also of fundamental importance to artistic creation.9 To do so, I will rely on one of the most central theories of aesthetics—Immanuel Kant’s aesthetic judgment, and Hannah Arendt’s reading of it as political judgment.

First, however, a disclaimer. I would like to stress again that my conclusions regarding the ethical implications of cultural appropriation are restricted to voice appropriation. I do not deny the possible harm of some types of cultural appropriation, and I agree this subject should be addressed with the utmost sensitivity and gravity.10 That being said, I claim that there is considerable confusion surrounding the arguments usually made against non-tangible cultural appropriation, and specifically voice appropriation. According to such arguments, an outsider may not be adequately trained in the style or aesthetic procedures they are appropriating—what Young (2008) terms the aesthetic handicap thesis—or cannot draw from the appropriated culture because they lack firsthand experience thereof—what Young terms the cultural experience argument, or experience inauthenticity. This may lead to a misrepresentation, meaning a distorted, flawed, incomplete, or inauthentic depiction of the insider’s culture.11 The opponents of cultural appropriation would argue that such depictions are not only aesthetically flawed, but also morally wrong, because they perpetuate stereotypes or false images of that culture, and may also deprive insiders of the right, ability, and agency to represent themselves (Burns Coleman 2001).

Indeed, some artworks involving non-tangible cultural appropriation may result in superficial essentializing, exoticizing, or Orientalizing representations, or simply use cultural diversity as a profitable currency. At the same time, others may offer self-aware, complex, critical, and reflective representations of the culture appropriated. Such parameters should be considered in judging these artworks, rather than viewing them strictly as the result of the use or non-use of cultural appropriation. In this sense, I concur with Young (2008, p. 28) that “there can be no blanket condemnation of cultural appropriation”.12 However, while Young objects to such condemnation mainly by explaining how an artist might be sufficiently qualified in the aesthetic procedures of another culture, or how a firsthand experience is not necessarily required for artistic creation, I stress that the possible outcomes of voice appropriation—distortion, incompleteness, or inauthenticity—are not necessarily aesthetic flaws, let alone morally wrong. On the contrary, in artistic creation, such traits or tactics may be used critically to construct complex representations of the Other, as demonstrated in our case studies below.

Ashery and Rosen’s fictive personas are part of a long lineage ranging from 19th century literary use of pseudonyms, through Marcel Duchamp’s famous feminine alter ego Rrose Sélavy in the early twentieth century, to the increase in imaginary artists, curators, critics, and collectives since. Some examples of the latter category include fictive pop artist Vern Blosum, featured in Artforum and in Lucy Lippard’s 1966 anthology Pop Art, whose painting was acquired by MoMA (Lippard 1966; Boucher 2013); Safiye Behar, a Jewish-Turkish feminist activist and intellectual who maintained a close relationship with Atatürk and allegedly influenced most of his reforms in the 1920s, created by Canadian artist Michael Blum and presented in the form of a historical museum in the 9th Istanbul Biennale in 2005 (A Tribute to Safiye Behar); gallerist/artist Reena Spaulings, who took on a life of her own since her inception in 2005 as a novel by the Bernadette Corporation (2005); and Joe Scanlan’s African-American female alter ego Donelle Woolford, whose inclusion in the 2014 Whitney Biennial as “real” was harshly criticized (McDonald Soraya 2014; Wong 2014). Such figures, some creating, others functioning as post-conceptual (good or bad) artworks, and still others, merely internal artworld jokes, tap into the current obsession with identity politics and cultural appropriation in non-traditional ways, as well as into longstanding questions concerning fakery, authorship, and singularity versus collectivity.

Israeli art offers an interesting case for studying fictional and parafictional personas in light of cultural appropriation. Note that heated discussions of cultural appropriation are less common in the local art discourse than in the West. This is probably related to Israel’s political situation as an occupier that is implicit in various forms of appropriation (Zayad 2019). To this I will add the multiple, often overlapping identities characterizing the societies in Israel/Palestine: secular and religious Jews; Jews of European as opposed to Asian and African descendent; and Palestinians with nominal Israeli citizenship vs. those living under military occupation—to name a few. This conglomeration of identities should be considered in light of Israel’s self-definition as a Jewish State, thus excluding a considerable number of its citizens, let alone non-citizens, on a legal basis.

What is most important for our purposes, however, is the way “Israeli” was shaped as a national identity ex nihilo not so long ago. This was done through the Zionist top-down “melting pot” policy in the 1950s–1960s, which sought to replace what was perceived as the submissive, effeminate, and scholastic Diaspora Jew with the masculine, combative, and land-working Tzabar.13 In the process, the diverse identities of the Jewish people in the diaspora were expected to merge (Kimmerling 2004). Thus, the fictive grounds on which any national identity or culture is based become more blatantly evident in the Israeli case.14 The fictitious unification of the inherently diverse young Israeli society, the multidirectional appropriative agglomeration of its identities, and its immoral role as a powerful occupier and skillful appropriator all make the local climate a valuable context for the study of parafictional figures. However, and perhaps also as a result of that very same climate, such figures and their discussion are uncommon in the local landscape.15

I have chosen to focus on two exceptions to that local rule—Ashery’s and Rosen’s Fisher and Frank, respectively—as they share similar features relevant to our issue. Both identities transgress hegemonic Jewish and Zionist categories through cross-gender and sexually provocative practices and aesthetics, and both have functioned as parafictions for a certain period. Thinking of two artists together who engage in opposite gender appropriation—Rosen appropriating a female identity and Ashery appropriating a male one—enables us to consider the direction of power relations—a subject inherent to appropriation. Moreover, as discussed below, both artists deal with identity in general, and have created other fictive figures as well.

2. Ashery’s Fisher: Unserious Appropriation

Some people just move freely between different states and different identities, but that’s not him. He felt like he was too lost already for that. There was always some distance between him and himself, that was difficult to take.

This description of Fisher appears in Marcus Fisher’s Wake (2000), a short mocumentary in which footage of Fisher is overlaid with voiceover describing his short and troubled life.16 I suggest that the “distance between him and himself” refers to the distance between a person’s identity and the way it is mirrored back to them by others. Such distance—which holds psychological implications as well as aesthetic value—is especially embodied within Fisher. First, he is a fictive character played by his creator, that is, composed by an Other. Moreover, the spectator, who is at times unsure about Fisher’s fictiveness (especially in his early street interventions), becomes another Other, who reflects Fisher back to himself while breaking him apart. Note that Ashery has initially created Fisher as a personal attempt to relate to her religious maternal family, and more specifically to a childhood friend of hers who had disconnected from her after becoming religious (Ashery 2003). Thus, the persona’s appropriation has stemmed from a genuine need to reach the Other.

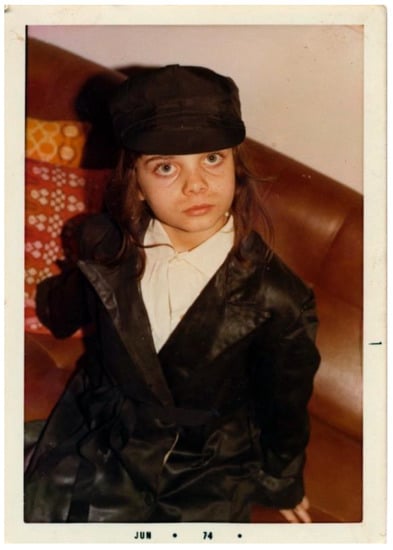

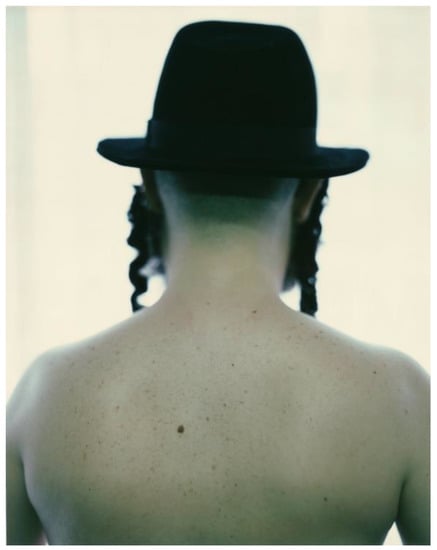

Ashery performed the Fisher identity in 2000–2003 in various street interventions, staged performances, photograph series, and video works. Her disguise was always the same, made of cheap props: fake beard and moustache, dark blue jacket and black trousers, sidelocks, and tzitzit (fringes) (Figure 1). Rachel Garfield observed that these were the “generic tropes of orthodoxy”, in fact composed of numerous denominations recognizable by different fashions. In this sense, she wrote, Fisher was an “approximation”; rather than signaling a belonging to a particular community, he constructed a generic, stereotypical male Orthodox Jew. For Garfield, this meant that Ashery’s “interest lies in addressing those who don’t know the difference—the generic art world, gentiles, and-affiliated Jews” (Garfield 2003, p. 98). Indeed, Ashery (2003) mentioned that she “simply wanted people who are not familiar with the coded dressing to recognise me instantly as an orthodox Jew, but not one in particular—rather—a signifier, an image, a simulacra”.

Figure 1.

Oreet Ashery, Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher I, 2000, original 25.4 × 20 cm; Polaroid scanned to lambda prints, 100 × 110 cm. Photograph by Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

Fisher may be instantly recognized as a Jew, but, at the same time, his generic looks also point to his representative character as “not-real”, not the thing-in-itself. He is not an individual, but an emblem. He is an inauthentic, incomplete, inexact, approximative appropriation of a religious Jewish male identity. And precisely for that reason, he demonstrates how stereotypical representations are, in fact, far from reality.

The line between parodying and stereotyping is thin, and walking it, especially through appropriation, entails risks, such as being accused of exoticizing the Other. Dorothy Rowe (2008) defends Ashery’s work in this respect:

Certainly for me in Marcus Fisher’s Wake, Ashery avoids exoticising Orthodoxy precisely through her parody of the structures of gendered and ethnic difference that the religion literally embodies. If exoticisation implies identificatory desire of the ‘Other’, Marcus Fisher’s constant re-iteration of removal and difference from that with which he is supposed to belong doubly parodies the stability of his constructed ethnicity.(p. 149).

This “re-iteration of removal and difference” manifests in different ways in Fisher’s embodied yet fragmented otherness. Marcus Fisher’s Wake was created following Fisher’s public performances, interventions, and photographs, as an unsuccessful attempt to “kill” him (he was then resurrected in another performance discussed below). Here, the wake format is used in a reversed manner to construct Fisher’s biography, in this sense giving him (after) life, thus stressing its fictive existence.

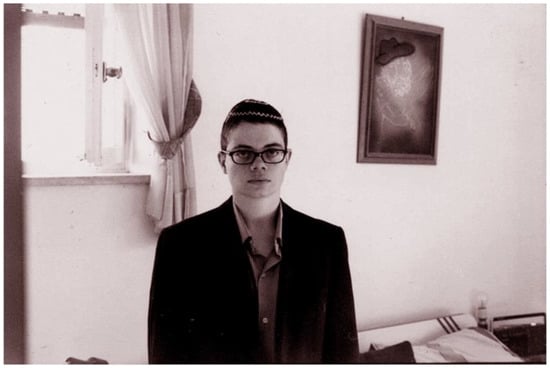

At the same time, Ashery’s real biography is appropriated, granting Fisher some of her “realness.”17 When discussing Fisher’s childhood, the video makes use of Ashery’s childhood and teenage photographs dressed as a religious Jewish man (Figure 2 and Figure 3).18 In this sense, Fisher is a direct continuation of Ashery’s cross-dressing practice,19 challenging the biblical prohibition on cross-dressing (Deuteronomy 22:5; in Hebrew, “Mar Cus” literally means “Mister Cunt”). Fisher’s fluid gender is further alluded to through the attribution of Ashery’s parents as his. The opening scenes of the video depict the view of Jerusalem from Fisher’s (Ashery’s) parents’ apartment, his father cooking fish in the kitchen, and the voiceover describing the unseen mother as “quite butch”; she makes all the money while the father cooks and cleans. Such a reversal of traditional gender roles alludes to the ultra-Orthodox “learners’ society” in Israel, where men devote themselves to studying the scriptures, while the women work and often take care of finance.

Figure 2.

Oreet Ashery, Boy Marcus, 1974/ongoing. Photo by unknown family photographer. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 3.

Oreet Ashery, Young Marcus Watching, 1998/ongoing. Photo by Chaya Ashery, artist’s mother. Courtesy of the artist.

According to Garfield (2002, p. 11), “the Jewish man is not really a man, and the woman is invisible.” She explains how the “feminization of the Jewish male in Europe, possibly deriving originally from the symbol of circumcision as castration but really invented and fueled by anti-Semitism”, was later adopted by Zionism, which opposed the masculine and rough Tzabar man to the scholarly, victimized Diaspora Jew. Thus, “Oreet’s alter ego of Marcus Fisher could … be seen as a rejection of the ‘Macho’ Israeli image of masculinity in favour of a more gentle and sensitive manhood” (p. 12).

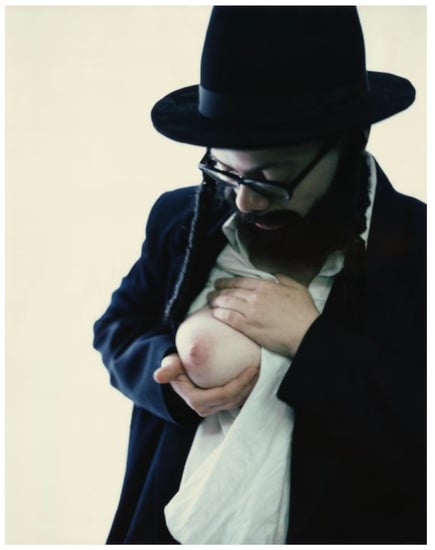

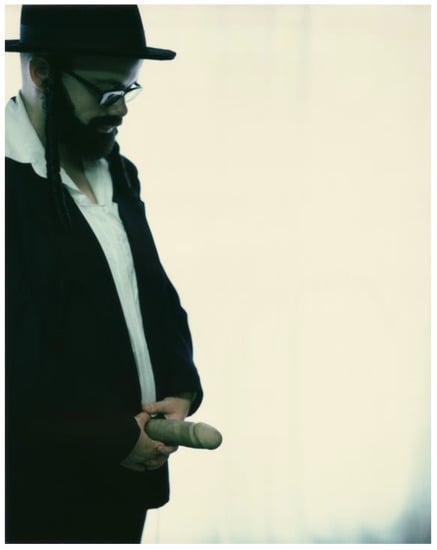

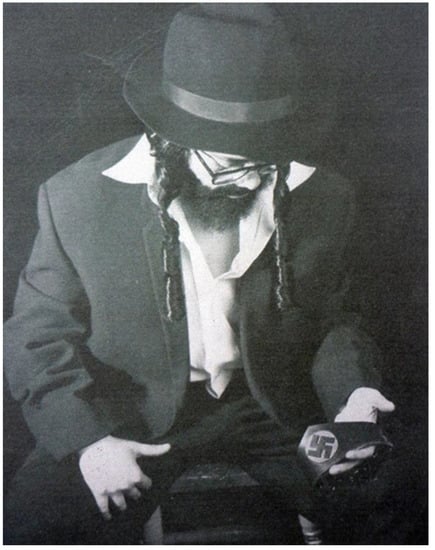

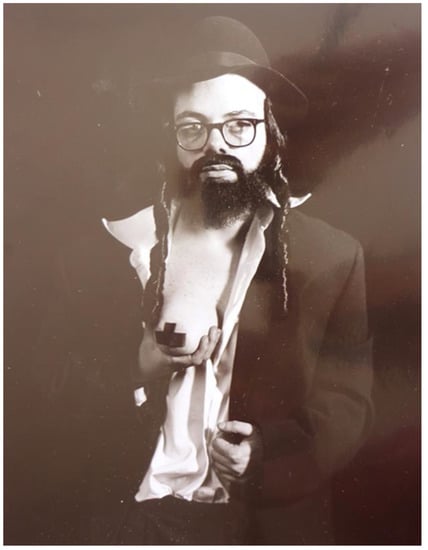

However, I would argue that Ashery’s performance avoids such binarism, through a practice she refers to as “gender terrorism” (Ashery, quoted in Wolf 2004). Embodying Fisher, Ashery knowingly enters the Jewish-Zionist-Israeli cobweb of national-religious-gender relations with no intent to untwine it. This can be seen in the juxtaposition of Fisher’s various photographs, some included in the film. In a color studio photograph shot against a solid background, Fisher takes out one of his breasts and looks down at it as if it were a prosthesis (Figure 4). In another, he is seen holding out his erect penis—this time, a real kind of prosthesis: a giant dildo (Figure 5). In yet another, his torso is seen from behind, revealing a non-gendered, naked back (Figure 6). The real, the artificial, and the grotesque, as well as femininity and masculinity, collide in these images.

Figure 4.

Oreet Ashery, Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher II, 2000, original 25.4 × 20 cm; Polaroid scanned to lambda prints, 100 × 110 cm. Photograph by Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 5.

Oreet Ashery, Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher III, 2000, original 25.4 × 20 cm; Polaroid scanned to lambda prints, 100 × 110 cm. Photograph by Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6.

Oreet Ashery, Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher IV, 2000, original 25.4 × 20 cm; Polaroid scanned to lambda prints, 100 × 110 cm. Photograph by Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

Fisher challenges binarism, and thus blurs the distance between him and himself, not only in terms of gender, but also in religious and political terms. Another pair of black-and-white, intentionally old-looking images throw in the mix the theme of the self-hating Jew—a clichéd, anti-Semitic portrayal drawing from psychological formulations of self-alienation. In one photograph, Fisher sits, holding and looking down at what seems like a Nazi armband, adorned with a swastika (Figure 7). In the other, he again holds out one of his breasts, his nipple “censored” with black masking tape, reminiscent of the same swastika (Figure 8).20 In one of the scenes of Marcus Fisher’s Wake documenting one of Fisher’s performances, he is seen strip-teasing and dropping his pants to reveal thighs covered with black-and-white makeup stripes, forming the negative image of a Star of David.21 The symbol embodies the contradictory existence of the diasporic Jew as Israel’s Other: it proudly represents Judaism and Zionism, but is stained with derogatory anti-Semitic connotations from when it was used to identify Jews in the Holocaust (Yellow Badge), which are further stressed in Fisher’s performance by the use of prisoner-like underpants.

Figure 7.

Oreet Ashery, Marcus Fisher III, circa 1998. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 8.

Oreet Ashery, Marcus Fisher I, circa 1998. Courtesy of the artist.

Ashery’s genealogy is also ascribed to Fisher’s. The narration explains that Fisher’s mother was originally Orthodox, but adopted a secular lifestyle at a young age, as did Ashery’s mother. Considering such a family relation, and Ashery’s cross-dressing, one can argue that Ashery has some kind of “ownership” over a religious and male identity, and hence a kind of moral legitimacy and authentic validity in appropriating it. In other works, Ashery appropriates the persona of an Arab man, also perhaps justifiable by the fact that her father comes from a family of indigenous Jews who have lived in Palestine long before Israeli statehood, hence Ashery’s self-definition as a “Palestinian Jew”.

I would rather avoid such arguments, however, not only because I find this kind of morally justified and genealogy-based legitimization, often used in the discourse of cultural appropriation, irrelevant to reading an artwork.22 More importantly, I believe that Ashery’s appropriation of the masculine Orthodox Jewish and Arab identities derives from difference and estrangement, and therefore desire, rather than from ancestral affiliation. She writes:

I was brought up in Jerusalem, somewhere between the Palestinian Arab neighborhood Shoafat and the orthodox Jewish neighborhoods beginning with Bar Ilan Boulevard. I was all too aware that as I was trespassing both geographical boundaries on separate occasions, these two alien territories equally exclude me, whilst at the same time sexualise me. As a girl, I felt not only excluded by both territories, the Arab and the Jewish, I felt excluded from the conflict itself.(Ashery 2003; the quote was slightly changed by request of the artist).

Is Fisher Ashery’s attempt to become included? Perhaps this has been the artist’s initial, emotional incentive. But as she herself acknowledges, her “desire to explore Israeli masculinity or better still to become part of it had kind of by-passed Marcus, who is truly an anti hero, de-politicised and de-territorialised” (Ashery 2003). Herself an immigrant in a foreign context, Ashery has knowingly chosen a character whose otherness is highly visible and who is excluded from numerous cultural spheres.

However, inclusion and exclusion are always relative. Fisher himself changes with his performing context, and Ashery, who refers to her works as “context-responsive” (Ashery, quoted in Johnson 2009, p. 94), asks whether Fisher might be “mobilizing the territory” (Ashery 1998). Marcus Fisher’s Wake includes documentation of Fisher’s early public interventions. He is seen in Soho, then still a multicultural heart of the gay scene in London. Nonetheless, when Fisher sat at a café he was ignored and almost unserved, revealing Soho’s “fairly guarded” diversity (Ashery 2003). Ashery also tells us that when she tried to order a drink at a gay club in London, a man who understood by her voice that she was actually a woman tossed it in her face (Ashery 2003). In Berlin, Fisher attended a venue similar in its strictly same-gender guest policy, but contradictory in its cultural function—a man-only Turkish café (Figure 9). There, according to the voiceover, he felt he belonged because he identified with the concept of “men being men”, of “real men”. This identification was of course imaginary, but Fisher’s additional identification with the men’s foreignness was consistent with his identity as a Diaspora Jew, as well as with Ashery’s real foreignness as an Israeli living abroad and as a woman in a man-only café—the Turkish café where Fisher found belonging through not belonging.

Figure 9.

Oreet Ashery, Marcus Fisher’s Wake, 2000, 16:15. Video still, 10:58 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Following Ashery’s (2003) description of Fisher as “the space where I question with others what is it to be or to relate to a Jew, here, now”, Laura Levin interprets “Ashery’s drag in spatial terms. Her orthodox alter-ego is dragged or pulled from one location to another, slipping in and out of spatial skins” (Levin 2014, p. 158). Like all of us, Fisher is composed of a changing assemblage of his representations as reflected back to him from his hostile, indifferent, or amused spectators. But because of his parafictional status, his artificial-stereotypical look and uncategorizable behaviors, he also “frames the framer” (p. 157). Meaning, he reflects back and dismantles the representations his spectators throw at him in an unsettling manner, allowing both himself and his spectators to accommodate multiple and contradictory positions. The passersby who are unaware of his artwork status, as well as those watching the video and witnessing the same interactions while aware of his fictiveness, both frame him and are framed, albeit on different levels of self-awareness.

This quality was enhanced in Say Cheese, performed in various locations from 2001 to 2003.23 It invited the spectators to enter, one by one, into bedrooms belonging to the show’s curators or hotel rooms rented especially for the show. There, for three minutes, they could share a bed with Fisher, and ask him to do anything they liked, except inflicting or receiving physical pain (Figure 10). As Ashery (2003) explains,

‘Say cheese’ was conceived as an experimental chamber to try out one’s potential relationship to the ‘Jew’. In this way the interaction can be used as a mirror, which participants can use to see themselves as they are relating to the other. However the Other is complicated in that it is a simulation and a hybrid. Participants firstly have to identify for themselves who is the Other; the artist, the orthodox Jew, or the combination of both and more?

Figure 10.

Oreet Ashery, Say Cheese, 2002, performance documentation, City of Women Festival, Kapelica Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

In this case, the spectators were aware of Fisher’s fictiveness. Nonetheless, they became implicit in his representation, because they were invited to hold a shutter-release cable and press it whenever they wanted to document the situation—a kind of invisible mirror. The photographs were later mailed to them. The participants became directors controlling not only the situation, but also its documentation, while being aware of their becoming a representation, which added to the twisted power relations driving this performance-cum-psychological experiment.

In a 2003 intervention called Dancing with Men, Fisher joined Orthodox Jewish men in the annual Lag Ba’Omer celebration on Mount Meron in northern Israel. The celebration commemorates the death of 2nd century Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, who decreed that he be mourned with celebratory dancing. Roberta Mock suggests that Ashery has chosen to join that celebration among other things because of its “mystical meanings”. Rabbi Bar Yochai is considered the author of the Zohar, a foundational text of the Kabbalah, a Jewish mystical school according to which harmony will be found when the Shekhinah—the female element of God—will be united with its male principle. “By dancing in this place, on this day, Ashery emphasizes the many boundary positions that may be blurred in complex ways, even as the one between real male and female bodies is reinforced” (Mock 2009, p. 36). Indeed, only men are allowed at the event, while the women remain at the bottom of the site, mourning.

Ashery (quoted in Mock 2009, p. 34) describes her experience of sharing the male ecstatic dancing as follows:

The feeling was tremendous, the high I felt whilst dancing and being accepted by those men was indescribable, a true connection, belonging and a sense of history and home. It seems one could only feel truly connected by being a ‘cheat’, an impostor, by not belonging at all. Following my ‘outsider status’ throughout my youth in Israel, and as an immigrant through my adulthood in England, it seems that I can only feel belonging through the experience of not belonging. It is the only true feeling I know of home.

Ashery describes a feeling common in today’s global yet increasingly xenophobic and nationalistic world—living outside your group, non-belonging, which has become today’s new belonging. Ashery’s and Fisher’s biographies further refer to the theme of the Wandering Jew, who is bound never to belong.

But more interesting for our purpose is the fact that the belonging-through-not-belonging felt by Ashery-Fisher in Dancing with Men is partly an outcome of the uniqueness of this performance. On Mount Meron, Fisher had to perfectly pass as an Orthodox man.24 Ashery even removed her fake sidelocks and moustache, so they would not accidentally fall (Ashery 2003). It was Ashery-as-Fisher’s first public appearance in which Fisher was not an approximation, but fully the real thing, at least for his dancing fellow men. In this situation, the knowing spectators of the performance’s documentation were the ones responsible of changing the context, and Fisher himself along with it.

Most of the film focuses on the dancing men. Only towards the end is Fisher seen, slim and delicate, a tender boy joining the celebration hesitantly (Figure 11). He is documented by a shaking handheld camera, giving the film a DIY aesthetic. Such an aesthetic cannot be treated solely as the unintentional outcome of the need for secrecy, because it is characteristic of other videos featuring Fisher, as well as of most of Ashery’s other works. For example, in Marcus Fisher’s Wake, our protagonist is also seen only one third into the film, through rough, poor footage, as if captured by an amateur hidden camera. The still photographs included are filmed so that they jitter unprofessionally on the screen. Rowe (2008, pp. 147–48) writes that:

Visual production strategies of disruption, subversion, fragmentation, fiction, pastiche and critique are all knowingly employed by Ashery at every level of the work’s content, format and medium imbuing the work with qualities of an amateur home-video—a production device employed in order to question the authenticity of the medium and thereby also cast doubt on the authenticity of its ‘biographical’ content.

Figure 11.

Oreet Ashery, Dancing with Men, 2003, 05:26. Video still, 04:09 min.

Other than challenging the reliability of the content, and hence Fisher’s realness, I would add that these strategies convey a kind of tabloid, voyeuristic aesthetic. They emphasize the fact that Fisher is looked, even peeped at; his image is out of his control and appropriated by others—the passerby and the film viewer. Ashery (quoted in Rowe 2013) explains how the process-based, experimental, and organic nature of Fisher’s early performances revolved around a sense of “feedback”. The spontaneous, haphazard aesthetic emphasizes Fisher’s quality as constructed, fleetingly and repeatedly, by the Other’s gaze, as well as the discrepancy inherent to such construction. These qualities are also (in)audible—in Marcus Fisher’s Wake, Fisher is not only completely silent, but also reported on (and criticized) by the narration of Del LaGrace Volcano, themselves gender queer performers who use a fake, non-binary American voice. According to the narration, when Fisher moved to London to study art, in a kind of reversal of the Zionist course and a return to the original state of the diasporic Orthodox Jew, he constantly created “self-portraits, endlessly trying to get in touch with himself”. As we shall see, the theme of self-portraiture is also at the heart of Frank’s practice. Considering the imaginary nature of both characters, this obsession with one’s face further implies procedures of alienation, splitting, and framing by the Other’s gaze. The same goes for Fisher’s performative practice, where he was “looking for himself and making a performance of it”.

After recounting Fisher’s drug abuse that brought about his tragic demise, the film literally fulfills its function as a wake by alluding to his fictiveness. This is done through reference to Fisher’s hero, Duchamp, and specifically to his feminine alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. Against the backdrop of Man Ray’s famous 1920 photograph Rrose Sélavy (Marcel Duchamp), the voiceover reminds us that Duchamp first considered taking on a Jewish identity, but because he “couldn’t find any enticing Jewish names to adopt… he opted for gender bending. He said it was simpler”. However, Fisher’s favorite was another piece by Duchamp—Tansure, his act of shaving his head in the shape of a five-pointed star in reference to “the ritualistic shaving of head of those entering a cult”, as explained by the voiceover. This performative act preceded the creation of Rrose Sélavy, and its “allusion to the putatively desexualized masculinity of the priest” raised questions regarding “the masculine role of the artist” (Zapperi 2007, p. 293). This might explain Fisher’s deepest desire as a child to get his head shaved, which is described in the beginning of the video as a “sign that he is going to be just a little bit different.”

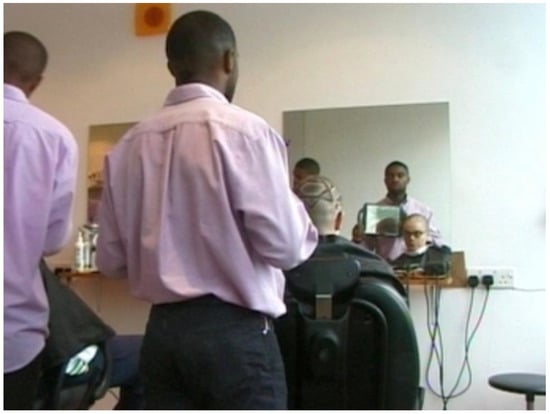

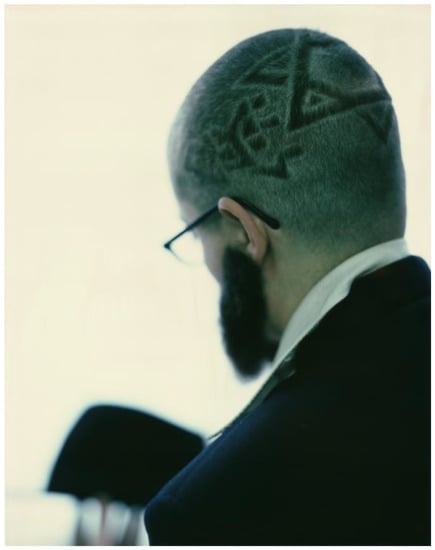

Hair, and especially its lack, as well as the various performances of the skinheads and their affiliation with Nazism, asceticism, and social humiliation, represent a central theme in Ashery’s early work.25 This is unsurprising, as hair, specifically body hair, has been culturally constructed as a fundamental visual signifier distinguishing male and female, and more generally as central in affecting one’s appearance and recognition by others. Fisher’s getting a head shave in reference to Duchamp’s is the focus of the second video work featuring him, titled What Is It Like for You? (04:06, 2000). Together with Faisal Abdu’Allah, the owner of a hair salon in North London attended mostly by Black Muslim men, Ashery designs a hair shave shaped like a Star of David combined with a pattern commonly used by the salon’s young male customers (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Oreet Ashery, What Is It Like for You?, 2000, 04:06. Video still, 03:09 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 13.

Oreet Ashery, Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher V, 2000, original 25.4 × 20 cm; Polaroid scanned to lambda prints, 100 × 110 cm. Photograph by Manuel Vason. Courtesy of the artist.

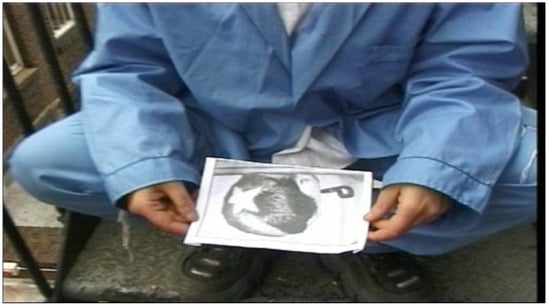

The video begins with a short closeup of the camerawoman staring through the camera lens—and then cuts straight to Ashery herself, sitting on a backdoor metal staircase, smoking and holding a print of Man Ray’s Marcel Duchamp (tonsure en étoile par Zayas) from 1919, in which Duchamp’s shaved head is seen from behind (Figure 14 and Figure 15).26 Ashery’s light-blue pajamas, combined with her shaved head, make her seem like a mental patient. The video ends with Fisher sitting in the same spot holding the same print, removing his fake mustache, beard, and hat as he is revealed to be Ashery, this time with the pattern shaved on her head. Another quick shot of the camerawoman, and Fisher is turned back to (crazy) Ashery, wearing the same pajamas while crawling and crouching on the metal staircase. The video ends with the same footage of the camerawomen, thus stressing how the switch from Ashery to Fisher and back again, as well as the entire performative intervention, are created for the camera, and framed by an observing, scrutinizing (female) Other.

Figure 14.

Oreet Ashery, What Is It Like for You?, 2000, 04:06. Screen shot, 00:08 min.

Figure 15.

Oreet Ashery, What Is Like for You?, 2000, 04:06. Screen shot, 00:14 min.

The short video was created during Ashery’s MA studies at Central Saint Martin’s College of Art and Design. Other than the hairdressing scene, Fisher is seen running up the stairs of the art school’s building with a large portfolio, hanging self-portraits, drawings, and photographs of Jewish religious men and leaders in the studio, dancing on the roof, sniffing a hard-boiled egg in the men’s toilets as it if was cocaine, scribbling “MF waz ere” on the wall, and masturbating in one of the darkrooms (Figure 16). These actions present Fisher as a trickster, a nihilist, a raging teenager—all traits that contradict his Jewish Orthodox appearance. He adopts Ashery’s persona as an art student, but he is a misfit, even in the tolerant art school context. The very title, What Is It Like for You?, which repeats in the pop-techno soundtrack accompanying the video, describes a wish to know someone else’s experience, to overcome the built-in barrier between two subjects, who can never enter each other’s consciousness. Indeed, the question remains unanswered, but the possibility and importance of asking it are present in the gaps between Ashery and Fisher, between Fisher and his audience.

Figure 16.

Oreet Ashery, What Is Like for You?, 2000, 04:06. Video still, 00:57 min. Courtesy of the artist.

In the first decade of the 2000s, alongside Fisher, Ashery took upon herself several other fictive personas, all male, among them The Fat Farmer, The Greasy Instructor, Masturbating Rabbit, and Norwegian Postman. Particularly relevant here is her appropriation of Sabbatai Zvi, a (real) 17th century false messiah. Sabbatai was involved in acts of transgressive Jewishness verging on blasphemy and based, in part, on the Kabbalah, and was suspected of homosexuality. Eventually, he converted to Islam (Ashery 2009). Like Fisher’s performances, Ashery’s appearances as Sabbatai, in which she reenacted some of his strange acts, provocatively transgressed gender and religious identities, while adding Islamic conversation to the mix. Ashery/Sabbatai’s most elaborate performance was The Saint/s of Whitstable, commissioned by the 2008 Whitstable Biennale, for which she resided in the coastal English town for two weeks, turning an old fisherman hut into her residence and performance space (Figure 17).27

Figure 17.

Oreet Ashery, The Saints of Whitstable, 2008, two-week performance, Whitstable Biennale. In the image: Oreet Ashery, Terence McCormack, Magdalena Suranayi, and Laura Hensser sitting outside the hut before performing the play reading. Photo credit unknown.

I would like to draw attention to the way the DIY aesthetic and the spontaneous nature of the Ashery-as-Fisher performances are enhanced in her as-Sabbatai performances, forming a “squat aesthetic” and “strategic amateurism” (Johnson 2009, pp. 94–95). In the Sabbatai project, this aesthetic specifically draws from Sabbatai’s original actions, in which Ashery is interested because of their performative quality of religious make-believe (Ashery 2009). When writing on Ashery’s performances, specifically those performed as Sabbatai, Gavin Butt emphasizes their improvised happenings, amateur execution, and overall unserious approach, and praises them as transgressing the deadpan seriousness in which performance in general is often created and discussed, while reminding us that seriousness often has to do more with power than with content. Similar seriousness characterizes the thinking of cultural appropriation itself, which often neglects the content and specificity of its object of criticism.

Fisher’s character itself is “unserious”. According to the voiceover in Marcus Fisher’s Wake, he “had a sense for performance. Maybe that was partly the problem, that he never believed in anything enough. He always thought of life as a bit of a performance, a game … he couldn’t take anything seriously, a deep sense of disbelief.” Not only Fisher but also his spectators did not fully believe, clearing the way to other, unexpected interpretations and judgments of their experience of Fisher. In Butt’s words, the unserious nature of Ashery’s appropriation, or her “deliberately compromised performances” are a “risky strategy” because “they derive their power precisely from a flirtation with the negative judgements that threaten to defeat them” (Butt 2009, p. 85). This brings me back to the argument with which I opened my discussion of Ashery’s appropriation of Fisher: Marcus Fisher’s unserious parafictiveness, which is nonetheless embedded in reality and attached to a real body, is exactly what gives its parodying procedures their transgressive power.

2.1. Cultural Appropriation as Enlarged Mentality

At this point, I would like to offer a theoretical perspective for thinking about voice appropriation through parafictional characters as allowing to imagine the Other. In her reading of Kant’s aesthetic judgment as political judgment, Arendt (1982) stresses the importance of the imaginative representation of the Other. Kant ([1790] 2000) famously described aesthetic judgment as a reflexive judgment, meaning that it does not follow a priori concepts, as well as a disinterested judgment. This results in a “subjective universal” judgment that cannot be justified according to objective parameters, but nonetheless, due to its disinterestedness, holds a kind of universal validity or communicability. Arendt (1968) explains this as being “endowed with a certain specific validity but is never universally valid” (p. 221). Such universal communicability depends on what Kant calls “common sense” (sensus communis). For Arendt (1968, p. 220), this common sense derives from an “enlarged mentality”, which “needs the presence of others ‘in whose place’ it must think, whose perspectives it must take into consideration, and without whom it never has the opportunity to operate at all”.

Such other perspectives are manifested in aesthetic and political judgments through representation. Kant ([1790] 2000) stresses the dual function of representation in aesthetic judgment: the imagination represents the judged object to the understanding, as well as other possible judgments of that object. Or in Arendt’s (1965) words, “The point of the matter, is that my judgment of a particular instance does not merely depend upon my perception, but upon my representing to myself something which I do not perceive” (quoted in Beiner 1982, p. 108). Elsewhere, she writes:

Political thought is representative. I form an opinion by considering a given issue from different viewpoints, by making present to my mind the standpoints of those who are absent; that is, I represent them. This process of representation does not blindly adopt the actual views of those who stand somewhere else, and hence look upon the world from a different perspective; this is a question neither of empathy, as though I tried to be or to feel like somebody else, nor of counting noses and joining a majority but of being and thinking in my own identity where actually I am not.(Arendt 2000, p. 556).

Arendt (1982) explains that for Kant, imagination is of utmost importance for this kind of thinking: “to think with an enlarged mentality means that one trains one’s imagination to go visiting” (pp. 42–43). Imagination liberates us from our private conditions, and allows us “to attain that relative impartiality that is the specific virtue of judgment” (p. 73). Kant ([1790] 2000) stresses that these procedures of imagination and representation are crucial not only for aesthetic judgment, but also for aesthetic creation.

When Ashery situates herself as Fisher, she uses her ability to imagine others through representation. Her alter egos are for her “a way of accessing different characters’ consciousness” (Ashery, quoted in Moyer 2007). Most importantly, her spectators become implicit in this act. The failing of their expectations of Fisher—regarding his stable male and religious identities, as well as his overall “realness”—are intertwined. The spectators’ understanding of Fisher as a work of art, i.e., their aesthetic judgment of the work as art, necessarily involves political judgment as well, because the revelation of the fiction, of the aesthetic representation, brings forth the representational nature of judgment itself. The understanding that the thing is a representation, that “I only see this as such”, but it is not such, implies the understanding that others may see it differently. Fisher enables Arendt’s enlarged mentality, meaning not only the ability of each spectator to see him as something else, but also the spectators’ understanding that this is so. Ashery’s “theatre of strategic inadequacy” (Johnson 2009, p. 97), meaning her inauthentic, unserious appropriation of Fisher’s voice, is exactly what allows her spectators the full range of representations of such an Other, and many more.

2.2. A Final Note on Appropriation and Collaboration

I would like to conclude my discussion of Ashery’s Fisher by thinking of her practice at large. Alongside her individual appropriation of parafictional personas, she often collaborates with other artists. I argue that these two practices are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. Ashery uses collaboration as another aesthetic form of thinking with and from the Other: “simply the idea of having two perspectives put together creates a certain overview and a third perspective that would not otherwise emerge” (quoted in Rowe 2013, p. 247). The affinity between appropriating an Other and collaborating with one should be highlighted specifically in relation to Ashery’s appropriation of Oriental Jewish figures or her mixing of Jewish and Arab alter egos, and her collaboration with Palestinian artists to create works addressing the Israeli occupation of Palestine.28 In recent years, Israeli–Palestinian artistic collaboration has been harshly criticized as normalizing the occupation. The dogmatic exclusion that often characterizes such critique is reminiscent of the sweeping condemnation of cultural appropriation, which often neglects to consider the context, content, and specificity of its criticized subject, and leads to counterproductive results.

3. Roee Rosen’s Justine Frank: Self-Critiquing Appropriation

While the transgressive nature of Ashery’s Fisher is achieved through the spontaneous and unserious nature of their performances, the opposite may be said of Rosen’s Frank. The latter is a painstaking scholarly work of academic scope and depth, where self-criticism and self-reflexiveness are mastered through an elaborate system of self- and cross-referenced personas, texts, and images. But although snugly fit within a carefully designed conceptual infrastructure, and perhaps precisely because of this, Rosen’s appropriation of Frank, much like Fisher’s by Ashery, is an inauthentic, incomplete, and, at times, stereotypical representation, whose construction by the Other’s gaze is continuously emphasized. Because Frank, unlike Fisher, is bodyless, it is the discourse around her that enables the game of mirrors, enabled in Fisher’s case by his real-life performances.29

Frank’s first public appearance was mostly textual, in an essay by Rosen about Sweet Sweat, the pornographic novel Frank allegedly wrote in 1931 (Rosen 1999). For this purpose, Rosen wrote only those parts of the novel that suited his interpretation and were quoted in the essay.30 Only later did he write the (almost) entire novel and published it as if he had rediscovered it (Rosen 2001, 2009b).31 The interpretative essay’s original Hebrew publication in an academic journal was the first public appearance of works attributed to Frank, all created by Rosen. In this sense, the interpretation and criticism came before, or were concurrent with, the discussed creation. The research meant to bring life to Frank by situating her within her historical and cultural context became part of the artwork itself; in fact, its first manifestation.

Frank was a mentally unstable Belgian-Jewish painter, who associated with the surrealist movement in Paris during the late 1920s and early 1930s, and even had a brief relationship with Georges Bataille. The overwhelming mélange of religious Jewish iconography and radical pornography that dominated her artwork and the fact that it was created by a female artist with seemingly unresolved sexual desires repelled even the surrealists, and they soon denounced her. In 1934, Frank’s personal and professional difficulties, as well as the increasing anti-Semitism in Europe, led her to immigrate to Tel Aviv, a tragic decision that seemed “so unsuitable that it raises the possibility she was driven by self-destruction” (Rosen 2009b, p. 6). There, she was outcasted yet again—this time by the Jewish male and national chauvinist art circle, who similarly found her coupling of Jewish, scatological, and sexual imagery indigestible. Her rejection of Zionist ideology and the local landscape, combined with her odd appearance, represented the Diasporic Jew the Zionist society was trying desperately to leave behind. Frank disappeared one afternoon in 1943, and was written off the pages of history.

The appropriation of identities different from those of the artist is present in Rosen’s complex project on three levels. The first two are fictional: Frank’s work, in which she herself appropriates various masculine, Jewish religious and anti-Semitic personas and tropes; and the art-historical or socio-theoretical appropriation of Frank’s work by Rosen himself and two other fictional personas as presented in the equally fictive research and commentary on Frank’s oeuvre (Rosen 2003, 2009a, 2009b; Führer-Ha’sfari 2003). The third, real, meta-appropriation level is Rosen’s creation of Frank as a work of art. The complexity and self-conscious criticism present in the first two levels not only legitimize the third, but also testify to how appropriation is at the heart of aesthetic creation and its thinking of the Other. In this sense, the entire project can be thought of as rippling outwards, with one wavelet appropriating the next. On both ends, this dynamic results in appropriation—Frank’s creation is Rosen’s, and Frank’s appropriation is Rosen’s as well.

3.1. Rosen as Frank’s First Level of Appropriation

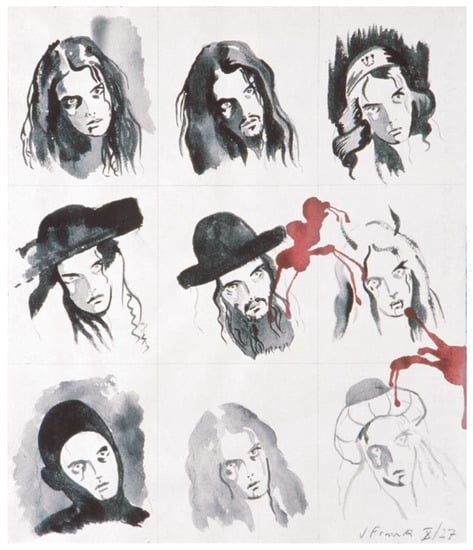

Let us begin with the first level. Frank’s work, supposedly created by a mentally unstable artist, demonstrates a self-perception steeped in multiplicity.32 Similarly to Fisher, Frank is first and foremost a self-portraiture artist. Her use of the genre challenges the cohesive normalcy of the face as representing a unified subject or an “interior identity” (Rosen 2003, p. 88). For example, several drawings from “The Stained Portfolio” (1927–1928) depict her multiple portraits in grid format, through which she slowly transforms into or becomes33 different types of Haredi Jewish men, or sprouts phallic organs and menacing pubic hair-like vegetation that gradually covers her profiled silhouette (Figure 18 and Figure 19).34 It is an “orgiastic masquerade in which she is simultaneously a great crowd and a single soul” (Rosen 2009b, p. 32).

Figure 18.

Justine Frank, from “The Stained Portfolio”, 1927–1928, gouache on paper, 33 × 38 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 19.

Justine Frank, from “The Stained Portfolio”, 1927–1928, gouache on paper, 33 × 38 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

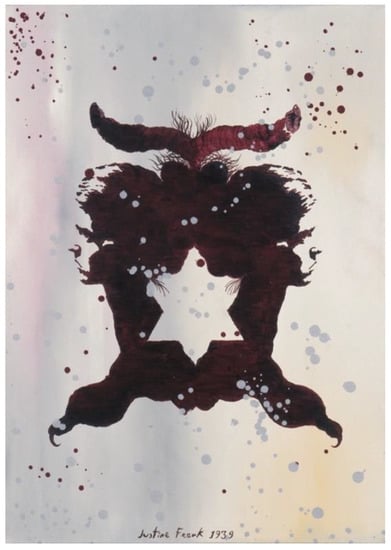

In other drawings and paintings, Frank uses a Rorschach-like procedure to double her profile, allowing a pair of phalluses to grow out of the meeting point of her two heads as if they were horns, while the negative space between her two napes forms a Star of David (Figure 20). Much like Fisher’s use of this symbol, in Frank’s work its two contradictory meanings—an emblem of religious-national pride stained with racism and humiliation—are used. Note that more than she appropriates Jewish imagery, Frank appropriates Jewish stereotypes as seen in anti-Sematic caricatures, such as large nose and horns, in itself a racist (mis)appropriation. One of these paintings’ titles, Frank Coat of Arms, suggests that the individual that is Frank is, in itself, a prestigious dynasty.

Figure 20.

Justine Frank, Frank Coat of Arms, 1939, oil on canvas, 70 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

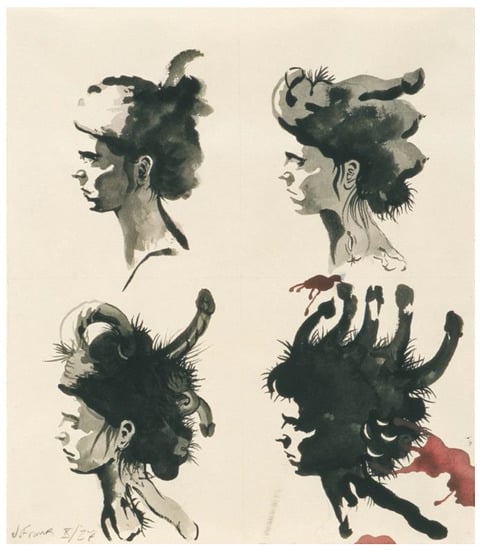

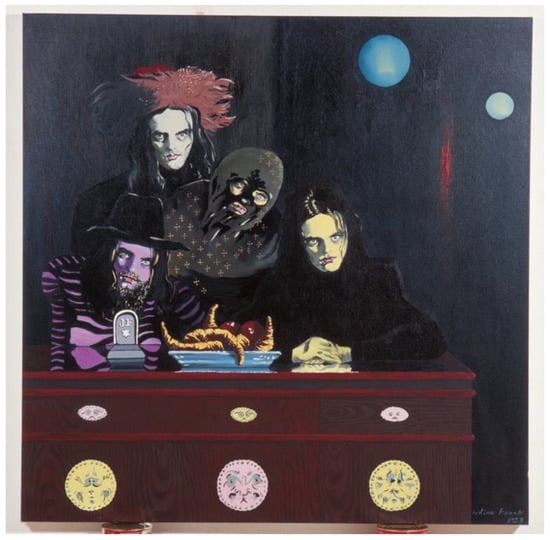

The theme of individual-as-multiple can also be seen in one of the most famous works of the project, a group self-portrait called Frank’s Guild (1936). Frank is seen as four different personas, each a variation on the theme of Jewish head covering (Figure 21). Frank composes a stereotypical, inauthentic portrayal of the Jewish man similar to that of Fisher, but instead of a generic Jewish look, it is a pastiche of Jewish Orthodox specific attributes. The conglomeration of head and face coverings echoes Ashery’s fascination with hair and its absence, and indicates an obsession to obscure identity, to dress up rather than to transform into a single specific Other.

Figure 21.

Justine Frank, Frank’s Guild, 1933, oil on canvas, 100 × 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

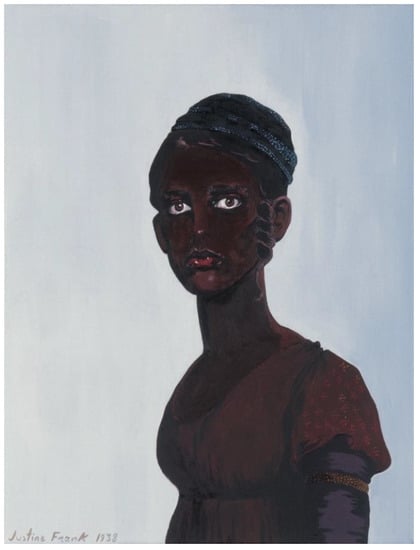

In Untitled (Self Portrait as a Black Woman) (1938; Figure 22), Frank committed what today would count as an outrageous cultural appropriation, when she depicted herself as a Black woman.35 However, here as well, the appropriation is not unidirectional. Black Frank also wears sidelocks like Orthodox Jewish men, and her dress and skullcap are reminiscent of those of Oriental (Mizrahi) religious Jews. In Mandate Palestine, Mizrahi Jews were identified with the indigenous Palestinian-Arabs, and in the Zionist art created at the time, their figures were used to symbolize the Biblical Jewish attachment to the land. In the short explanatory text included in Frank’s retrospective catalogue, this portrait is used to uncover her imaginary nature: “this portrait, revealed as a multitude of super imposed masks, is, in the end, the most realistic of Frank’s self-portraits, given that she is a fictive persona…” (Rosen 2003, p. 118). Frank’s fictiveness is channeled through that of the “indigenous” Jewish figure.

Figure 22.

Justine Frank, Untitled (Self Portrait as a Black Woman), 1938, oil on canvas, 65 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

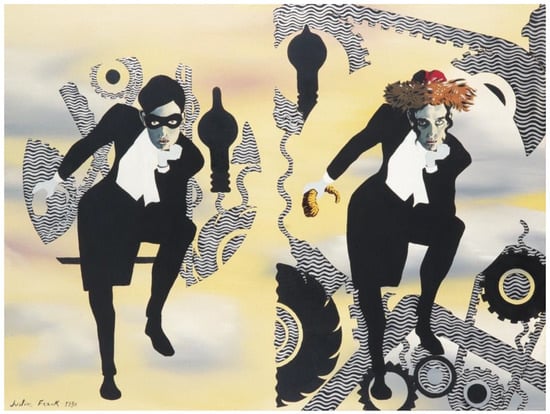

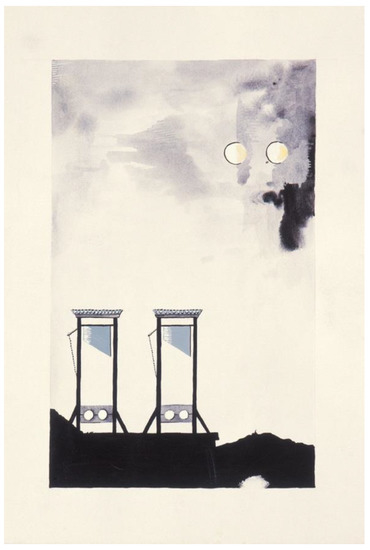

Moreover, Frank created her own alter ego, Frankomas, a gender-fluid religious Jew, itself an appropriation of Fantomas, a fictional character created in 1911 by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre that starred in a series of crime novels and movies and was adopted by the surrealists as their hero. Frankomas was subsequently multiplied as seen in the diptych The Sisters Frankomas (1931; Figure 23). Another recurring motif by Frank is the double guillotine, designed to decapitate two bodies at once, or rather, as suggested by Ekaterina Degot (2016), “implies the presence of a two-headed body”, and in doing so “deconstructs and defies the singular subject at the core of the Western philosophical tradition, as well as the artistic practices identified with it” (p. 307; Figure 24). Note that in a twisted loop, the project of Justine Frank as a whole challenges modernist and masculine concepts such as authorship, the genius artist, and artistic signature, as well as their subsequent post-modern deconstruction—precisely because it is eventually framed by a male artist.

Figure 23.

Justine Frank, The Frankomas Sisters, 1930, oil on canvas, 90 × 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 24.

Justine Frank, Double Double Guillotine, 1936, gouache on paper, 50 × 35 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

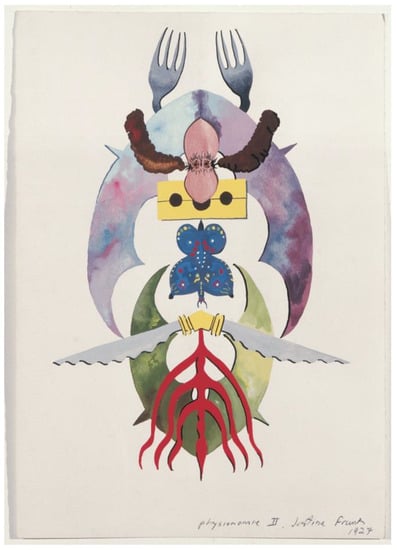

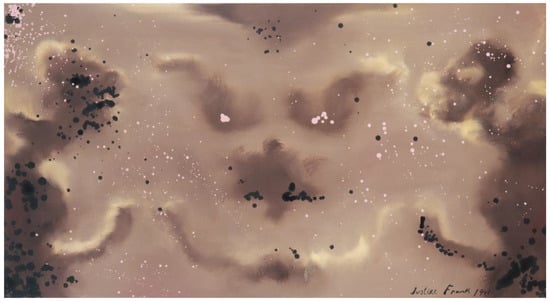

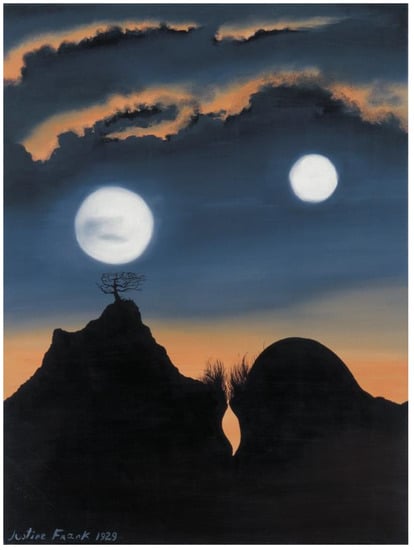

Frank’s concern with the face’s potential to multiply, dissolve, and morph extends beyond self-portraiture. In many of her drawings and paintings, and especially in the gouache series Physiognomies (1928)—whose title is suggestive of the racist pseudoscientific classification methods of the time—natural elements, Jewish symbols, and scatological forms are joined in mirror symmetry to create inherently split and animated faces (Figure 25). In her later sky paintings, symmetrical cloud arrangements create grotesque faces (Figure 26). In other landscape drawings, vulva-like crevices in the ground are coupled with double moons to form a sexualized face (Figure 27). In associating the face—described by Emmanuel Levinas (1991) as the primary arena of otherness—with reproduction organs, Frank hints to the potential of the individual to produce others. However, this is no parthenogenesis—the self, especially in self-portraiture, needs the Other’s gaze in order to reproduce—the artist’s gaze as well as the spectator’s.

Figure 25.

Justine Frank, Physionomie II, 1927, gouache on paper, 50 × 35 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 26.

Justine Frank, Heaven Manure, 1941, oil on canvas, 60 × 110 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 27.

Justine Frank, Lunar Eye Disease, 1929, oil on canvas, 80 × 60 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

In a fascinating text included in the catalogue accompanying a recent solo exhibition dedicated to Rosen’s overall theme of self-portraiture,36 Herzog and Wolkstein (2022, p. 178) explain how “mimetic truth”, mediated through seeing, has been traditionally central to portraiture as a measure of “similarity between the object and its creative portrayal”. However, in wishing to immortalize a subject, portraiture, in fact, stresses its changeability and temporary nature. Moreover, “in the act of portraiture there is no face” (p. 177), because portraiture disassembles the face into its components. Such traits become even more poignant in self-portraiture, where the subjects and their representations create a certain blindness. In this situation, the viewer holds tremendous importance, because he

frees the reflexive portrait from its blindness and re-immerses himself in the object: no longer a self-portrait, but a portrait of (self as) the other. … the observer… seem to correct the mistake on which the portrait is founded; he reveals to the portrait the alienation of himself—as an object that is not reflected over and over in the reflexive game. The viewer short circuits the reflexive circle: destroys the self-portrait and gives birth to the real portrait in his image; a portrait of the observing self as an other, or of another.(Herzog and Wolkstein 2022, p. 175).

That Other, the viewer of Rosen-as-Frank-as-many-others’ self-portraits, functions much like the passerby in Fisher’s performances, reflecting the portrait back to itself, to its subject, while revealing the otherness already embedded within the self. This otherness is further intensified by Frank’s Jewish identity and her exclusionary grounding in anti-Semitic, surrealist, and Zionist contexts: “The Jew in Rosen’s work is emblematic of the outsider, forever shunned and vilified by the gentiles. In a sense, the Jew is the foreigner par excellence, the quintessential misunderstood and persecuted outsider” (Tamir 2022, p. 183). Frank is the ultimate Other Jew, who—due to her appropriation of Jewish tropes over which she, as a woman, holds no authority—has been rejected by her “own” people, whether surrealists or Zionists. At the same time, it is her Jewish identity that relates her to Rosen, bringing me to the project’s second level of appropriation.

3.2. Rosen as Frank’s Second Level of Appropriation

As mentioned, the second level of appropriation consists of Frank’s art-historical parafictional appropriation by Rosen, as well as by two other parafictional art historians: Joanna Führer-Ha’sfari and Anne Kastorp. This appropriation is channeled by various elements. First, the “republication” of Sweet Sweat, which includes, alongside Rosen’s previously published interpretative essay, a lengthy biographical essay about Frank, also authored by Rosen. Both texts include numerous references to Kastorp’s work. While acknowledging her contribution to Frank’s legacy, Rosen nonetheless objects to some of the historian’s claims, specifically her late denunciation of Frank. According to Rosen, in an unpublished essay Kastrop argues that Frank’s blasphemous use of Jewish imagery proves her familial relation to and religious identification with Jacob Frank, an 18th century Polish-Jewish false messiah who eventually converted to Christianity, and founder of a heretical Jewish sect involving Christian elements and practices of “redemption through sin.” In Sweet Sweat, Kastrop further finds references to his relative Jacob Dobruschka, a spiritualist who also converted to Christianity. The art historian thus ultimately condemns Frank “as a veritable moral hazard” (Rosen 2009b, p. 17).

Jacob Frank claimed to be the reincarnation of Sabbatai Zvi—one of Ashery’s above-mentioned alter egos. Like Sabbatai, Jacob Frank and Jacob Dobruschka, Justine Frank and Marcus Fisher are manifestations of condemned Jewish otherness. It is not only the eccentric difference which attracted Ashery and Rosen to these historical figures, but also their involvement in deception, multiple identities, conversion, and make-believe. Quoting Gershom Scholem (1982, p. 182), Rosen (2009a, p. 192) writes:

Scholem asserts that such astonishing transformations are characteristic of Jacob Frank’s school: “We are faced with a person who wears several costumes at once and disavows them all, according to circumstances, and whose intent one can never fully comprehend—the complete person of the Frankist” … The “complete” Frankist, in other words, is a person who embodies the negation of himself as complete, cohesive, truthful (italics added).

According to Kastrop, Frank’s connection to Frankism reveals that her entire life and work as “a secular avant-garde artist” were “nothing but a coverup” (Rosen 2009a, p. 195). Such (a parafictional) interpretation does not only relate to the idea of the self as always-already constructed out of a mix of fictive identities, which is also present in Frank’s work (the project’s first level of appropriation), but also adds to the variety of interpretations present in the project’s second level of appropriation, all offering different art-historical “versions” of Frank. Moreover, Kastrop’s reading hints to Frank’s own imaginary nature, and Rosen’s rejection of it can be read as the artist’s attempt to defend his creation’s “truthfulness.”

Nonetheless, these many versions of Frank are further stressed in the other elements composing the project’s second level of appropriation, specifically those involving Führer-Ha’sfari.37 One such element is the short video Two Women and A Man (16:00), completed in 2005, two years following Frank’s first retrospective, and whose mere title implies the invention of the two (in fact three) women involved in the project by the male artist.38 The video presents segments from a shelved televised interview with Führer-Ha’sfari, which were, in fact, Rosen’s contribution to a real program.39 Rosen later edited the segments and added footage of Frank’s works accompanied by voiceover to create a disturbing interview with Führer-Ha’sfari.40 In the video, the art historian’s interpretation of Frank’s work follows the multiple characters of the artist’s imagery. Foregrounding a sequence which gradually overlays Frank’s self-portraits so that her profiled silhouette literally morphs before our eyes, Führer-Ha’sfari asks:

In this sense, a single reading of Frank’s work can be itself doubled, or split.Is this a case of demonic mysticism, or an ironic artist tackling the genealogy of Western anti-Semitism? … Is her scatological erotica a feminist parody of masculine desire, or is it a pathetic, naïve claim to feminine pleasure, or is it simply obscenity? Paradoxically, it seems that every question Frank evokes has at least two contradictory answers, and both are an outrage in their historical context.

In an essay that Führer-Ha’sfari allegedly contributed to the catalogue of Frank’s first retrospective (“Justine Frank, A Retrospective”, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003), this double quality was related to the way Frank’s work was interpreted by different researchers:

This complex echoing of the multiplied and split elements in the interpretation of Frank’s work is invaluable in terms of cultural appropriation. In the video, Führer-Ha’sfari’s criticism of Frank’s appropriation by Rosen the scholar (fictional criticism on his fictional work) not only implies and anticipates criticism of Frank’s appropriation by Rosen the artist (fictional criticism on his real work), but also allows the male artist to incorporate criticism of his previous exhibitions (real criticism on his real work).It is therefore likely that Frank’s ambivalence, which I earlier described as her “second nature”, is indeed psychologically quite dramatic. However, the protagonist of this psychodrama is not Frank but rather Anne Kastorp, who first forged the figure of the forgotten Frank as a liberated and liberating artist, courageously pulling skeletons out of the encumbered closet of European culture, and then traded the resulting nightmare for another! Kastorp’s two different Franks merged, somewhat later on, in Rosen’s mind, and became a schizoid Frank, split from within. […]When I emphasize that when we attempt to see Frank we actually look at Kastorp’s pair of Franks and Rosen’s double Frank, do I make a familiar postmodern claim by which there is no real Justine Frank beyond her mediated manifestations?… Quite the opposite: I believe Justine Frank is as real as I am. This is of tremendous importance to the retrospective viewing of Frank’s paintings—it is the very glance that can return to Frank some of the realness robbed by the good intentions of her interpreters.(Führer-Ha’sfari 2003, n.p.).

Regarding the first, fictional–fictional criticism, Führer-Ha’sfari acknowledges the importance of Rosen’s work on Frank’s biography, but admits she is ambivalent towards the overbearing association between the two artists’ works, hinting to plagiarism. She notes their shared interest in self-representation, and specifically the way Rosen has been inspired by Frank in creating feminized self-portraits of himself, including as female martyrs. As works by Rosen and Frank are shown side-by-side to highlight their similarities, she continues:

There is something quite manipulative about the way Rosen has appropriated Frank’s creation. It is sad to see Frank’s work reduced and consumed as yet another transitory, fashionable diversion. It’s ironic that such a strong female voice, that has been silenced and suppressed for so many years, is yet again subjugated to the pleasure economy of a male artist.

But Rosen does not stop here. The titles at the beginning of the video explain how the interviews with Führer-Ha’sfari were used to accompany a television program on Rosen despite Führer-Ha’sfari’s objection, and how they were reedited posthumously and presented in full in the present format. Through the abovementioned ripple structure, Rosen appropriates Führer-Ha’sfari’s words, just as he has appropriated Frank’s (second kind, fictional–real criticism).

The third kind of criticism (real–real) is represented in the video through the outrage brought about by Rosen’s previous solo exhibition, Live and Die as Eva Brown (Israel Museum, 1997–1998), in which he invites the spectators to engage in voice appropriation by becoming Hitler’s lover. The video incorporates interviews with contemporary politicians who declared the show an abomination and called for its closure. This real-life criticism is used to strengthen the fictional criticism, which, in turn, implies another potential real criticism, as Führer-Ha’sfari notes:

There is no comparing of the tremendous provocation… of Justine Frank with Rosen’s somewhat spoiled polemical stance. Justine Frank was a real outcast, and for that she paid a heavy personal price. Roee Rosen, on the other hand, might infuriate a member of the conservative religious party, but always with in “progressive” left-wing circles and the culture community, he will find support.

3.3. Rosen as Frank’s Third Level of Appropriation

Finally, I would like to address the third, meta-appropriation level of the overall project. Following Führer-Ha’sfari’s observation, one may ask whether Rosen merely used Frank’s persona to produce truly provocative work under disguise. I argue that it is exactly the similarity between Rosen’s and Frank’s work, which, as Führer-Ha’sfari argue, could have been suspicious had Frank been a real figure, that negates such a claim. Through Frank, Rosen merely elaborated his own creation and self-exploration using his distinctive style.41 According to Vered Hadad (2022, p. 187),

In this sense, Rosen’s appropriation of Frank, like Ashery’s of Fisher, is not a total, hermetic masquerading, but rather indicates the inherently split nature of artistic creation, situated in the gap between self and Other.Rosen is fully present in the deep structures of his works; The Rosenseque presence is the skeleton, the pictorial and artistic space, upon which the artist builds the whole work, even if he did not want to. The intrusion of the self into fiction, and the unconscious leakage of one’s actual character, are the vibration of art, of the unexpected.

Towards the end of the interview, when Führer-Ha’sfari is asked about her relationship with Rosen, she answers, “I think it is improper to ask such a question in this context”, while uneasily touching her hair (a wig) as the camera zooms in on her face to the sound of dramatic music. Hers is, of course, Rosen’s face. A viewer acquainted with the artist’s distinctive facial features would easily see the resemblance; but anyone would feel something is wrong. Like Ashery, Rosen does not go to great lengths in order to become Führer-Ha’sfari. He does not become the Other or others he inhabits. Rather, his multilevel appropriation lies bare to the Other’s critical gaze.

In a sense, Rosen’s triple, fictional act of self-critique becomes itself a representation of Arendt’s (1982) enlarged mentality and its multiple nature: “critical thinking, while still a solitary business, does not cut itself off from ‘all others’. To be sure, it still goes on in isolation, but by the force of imagination it makes the others present and thus moves in a space that is potentially public, open to all sides” (pp. 42–43). Rosen imagines, and further represents, the various possible judgments of his work. Furthermore, precisely by posing critique itself as a fictional representation, he opens up another circle of judgment and criticism—which, this time, belongs to his spectators. Rosen-as-Frank’s spectators are invited to shatter the façade of Frank’s elaborated project of self-portraiture. Its fictional crevices destabilize the spectators’ judgments, while opening up their thinking of the Other. Frank, her creation, her biography, the elaborate system of fictional characters and research around her, and the fact that all is imaginary, all point to the quality of aesthetic creation, representation, and judgment as situated between the self and the Other.

4. Conclusions

The current article focused on the appropriation of Jewish characters by Israeli artists. The differences and power relations between these artists and their fictive personas are multiple and contradictory, as are those characterizing the various Jewish and Israeli identities. Although the two case studies share many similarities, their aesthetic approaches and tactics vary greatly. Nonetheless, both prove how the appropriation of another voice may allow for the imagination, representation, and thinking of the Other, and, in turn, how these are inherent aspects of aesthetic creation and reception. Specifically, the use of parafiction, which emphasizes the political qualities of aesthetic judgment through the use of representation in real life, allows both artist and spectators to imagine a position different from theirs. In the case of parafictional identities, blurring the lines between the appropriated identity and its appropriator, as well as many other identities (Fisher as having both breasts, penis, and swastika arm band; Frank’s becoming self-portraits), is exactly what allows the spectator to understand the personas’ fictiveness, and thus the act of appropriation. Being fictions in real life, both Fisher and Frank stress how aesthetic representation embodies proximity precisely through its distance from what is represented, or in Young’s (2008) words, “the best biography is not always autobiography” (p. 61).

The aesthetic encounter takes place in the meeting between the private and public, since, in its essence, it involves our ability to sense what is around us, what is outside us, which always-already includes an Other. Moreover, the experience of what is around us entails the need and desire to validate, doubt, and differentiate such an experience by sharing it with others. Art, created by a private individual, but with the public in mind, and experienced by an individual, but with the Others in mind, inherently deals with the (im)possibility of crossing the boundaries between self and Other. In this sense, works of art are located in the blind spot between ontology and epistemology.42