Abstract

Wild and fantastical animals climb, fly, scamper, and prance across pictorial stone carvings decorating Eastern Han tomb doors in northern Shaanxi. Alongside dragons and other mythical animals, bears felicitously dance, tigers grin opening their mouths to roar, and other wild animals frolic in swirling cloudscapes. While the same animals can be found in Eastern Han tomb reliefs and mortuary art in other regions, their frequency, emphasis on plasticity and movement, and combination with the yunqi 雲氣 motif are unique to the region. Originating in a hybrid style of art that was created during the Mid-Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE), their significance was dependent not so much on any individual creature but on their display as an assemblage of shared forms, behaviors, and habitats. This paper explores how Eastern Han patrons and artists in Shanbei reinvigorated such imagery. It argues that on tomb doors through the region, these same wild and fantastical animals have become a key element of compositions meant to pacify the potentially dangerous realms that awaited the deceased in their postmortem ascension to Heaven (tian 天).

1. Introduction

Wild and fantastical animals climb, fly, scamper, and prance across pictorial stone carvings (huaxiang shi 畫像石) decorating Eastern Han tomb doors in Shanbei (northern Shaanxi; see map Figure 1). Alongside dragons and other mythical animals, bears felicitously dance, tigers grin as they open their mouths to roar, and camels, deer, mountain goats, foxes, boar, and other wild animals appear in swirling cloudscapes. Anatomically distinct and naturally rendered, at the same time, these animals twist and turn in linear movements that are unrelated to the real action of bodies in space (Shih 1960a, p. 187). While these animals can be found in Eastern Han tomb reliefs and mortuary art in other regions, their frequency, emphasis on plasticity and movement, and combination with a swirling Han decorative motif, meant to suggest clouds and/or qi 氣 (pneuma/spirit), is unique to the region.

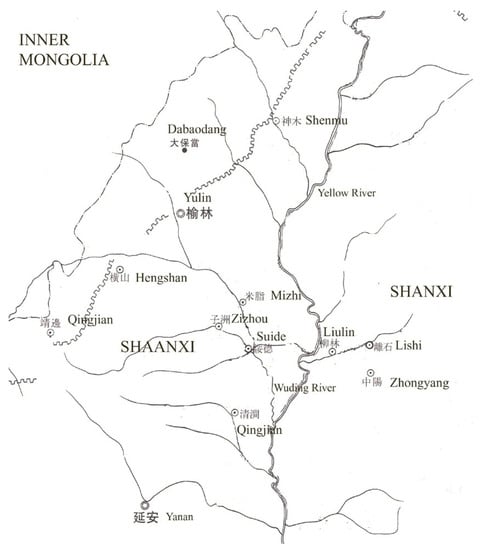

Figure 1.

Major locations where Eastern Han tombs with stone reliefs have been found in Shaanxi (After Wallace 2011b, Figure 1).

These animal forms originated in a hybrid style of art created during the Mid-Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE) that merged Central Asian, Steppe, and Warring States (ca. 475 BCE–221 BCE) traditions and whose significance was dependent not so much on any individual creature, but on their display as an assemblage of shared forms, behaviors, and habitats.1 Living in the borderlands between the Han and Xiongu Empires, Eastern Han patrons and artists in Shanbei reinvigorated such imagery in their tombs where wild and fantastical animals took pride in place. As a group, these animals served as an important component of a pictorial program designed to aid the deceased in their posthumous journey and transformation to the immortal.2 In what follows, I will first provide an overview of the characteristics of Eastern Han tombs and tomb reliefs from Shanbei and the Western Han imagery from which the depictions of wild and fantastical fauna in Shanbei are derived. Then, I will show the ways in which these animals were a key component of compositions that were meant to pacify the potentially dangerous realms that awaited the deceased on their ascent to Heaven (tian 天).

2. Eastern Han Tombs in Shanbei

In the late first and early second centuries CE, civil and military officials, wealthy merchants, and landowners living in the north of the modern province of Shaanxi commissioned tombs decorated with stone carved reliefs.3 Today this mountainous area is called Shanbei and lies at the edge of the Ordos Basin and the Loess Plateau (Figure 1). From what little is known of individual patrons, most were stationed there, or their families had at some time here, removed from the interior of the Han Empire, and were a minority among other groups living in the area that served as a buffer zone between the Han and Xiongnu Empires. Tomb relief production in Shanbei spanned from roughly the 90s until 140 when the Han government lost control of the region.

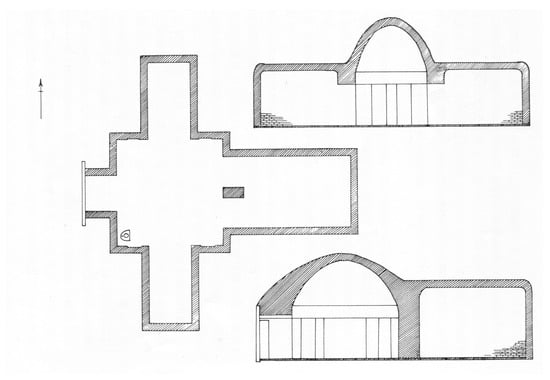

Eastern Han tombs decorated with stone reliefs in Shanbei are either single or double-chambered, with a small corridor (yongdao 甬道) between the tomb door and the adjacent tomb chamber. The simple single-chambered tombs are small with barrel-vaulted ceilings (quan ding 券頂), while double-chambered tombs have two rooms aligned on a central axis. The first room typically has a domed ceiling (qionglong ding 穹窿頂), while the rear is barrel-vaulted. The largest double-chambered tombs also have one or two barrel-vaulted side chambers attached to the left and/or right sides of the front room (Wang 2001, pp. 220–21) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Plan of a multi-chambered tomb excavated at Yanjiacha 延家岔, Suide 綏德, and Shaanxi. The central chamber has a domed ceiling while the other chambers have barrel-vaulted ceilings. Carved reliefs decorate the tomb doorway, and the areas around the entranceway to the two side and rear chambers (After Dai and Li 1983, Figure 1).

One unique aspect of tomb construction in the region is that stones with pictorial carvings were only used to construct the doorways and entranceways between some of the inner chambers, while the rest of the tomb was made of bricks. A standard tomb doorway was composed of five stone slabs: one lintel and two side and door panels (Figure 3). Typically, a lintel and two side panels framed the entranceways in the interior of multi-chambered tombs. Reliefs were modularly constructed, with stone carvers developing a set repertoire of motifs, which through the use of stencils and other means, were replicated and recombined in different tombs (Barbieri-Low 2007, pp. 91–92; Li 2019, pp. 77–79; Ruitenbeek 2008, pp. 152–53).4

Figure 3.

Rubbing of a tomb doorway, Hejiagou 賀家溝, Qingjian 清澗, Shaanxi. Eastern Han dynasty (After Li et al. 1995, p. 216).

A range of animals populates the reliefs carved by these artisans. In scenes that depict daily life, cattle, pigs, sheep, horses, dogs, camels, elephants, and trained raptors are helpers and/or sources of food for the deceased in representations of agriculture, animal husbandry, hunting, and chariot and horse processions.5 Most of these animals fall within the general category of the six domesticated animals liu chu 六畜 (horse, ox, sheep, chicken, pig, and dog) mentioned in pre-Han and Han texts (Sterckx 2006) and are commonly depicted in Eastern Han tomb reliefs and molded bricks. Depictions of animal husbandry and representations of camels and trained falcons are more regionally specific, probably reflecting the local ecology and traditions. Even more common and distinctive to the region are an assembly of wild and fantastical animals: deer, bear, camels, foxes, mountain goats, owls, tigers, wild boar, tianma 天馬 (winged horses), dragons, qilin 麒麟 (a one-horned creature), and assorted hybrids.6 These animals appear regularly in small and large groups in multiple compositions on the side panels and lintels decorating the doorways to tombs throughout the region.

The panels decorating a tomb door from Qingjian 清澗, Shaanxi, are representative of the pictorial design on many of the entrances to Eastern Han tombs in the region. On the lintel and the outer portion of about two-thirds of the side panels, and forming a frame for the rest of the decoration, bears, cranes, qilin, foxes, and tigers frolic among and/or their bodies are merged with an undulating line with cloud-like projections: a version of the yunqi 云氣 motif, popular in Han art (Munakata 1991, pp. 20–21). These lines trail upwards on either side of the door frame and stretch across its lintel, on either side of which are round circles representing the sun and moon. These animals are also joined by avian–human hybrids called xian (immortals). In Shanbei, the undulating line in which animals climb and are entwined may have craggy mountain-like appendages or, as in this particular example, have extensions reminiscent of depictions of lingzhi 靈芝: an immortality-granting fungus that is also depicted in the region and is common in Han art (Powers 1983, pp. 287–88).

Across the lower portion of the lintel, a winged hybrid, dragon, tianma 天馬 (lit. “heavenly horse; a mythical winged horse), and qilin are framed by two mounted archers; one turns his back in his saddle to take aim at a tiger while the other faces forward toward a bird, deer, and fox. On the right-side panel, Xiwangmu 西王母 (the Queen Mother of the West), a deity who presides over an immortal paradise, sits atop a pedestal-shaped mountain. The organic lines and form of the pedestal’s support are also suggestive of lingzhi. On the left side of the panel, atop a similarly shaped mountain, two immortals sit on either side of a mounded, unidentifiable object.7 Lingzhi sprouts from the sides of the winding pedestal, and a fox and deer frolic on either side of the two smaller mountains. Below the carvings, two-door guardians/officials stand facing the door, and below them are depictions of mountain-shaped incense burners (boshanlu 博山爐), with lingzhi growing out of their basins. Finally, on the door panels themselves, two zhuque 朱雀 (vermillion birds) perch on pushou 鋪獸: a type of monster mask often depicted on real knockers, below which a winged tiger and dragon stand facing one another.8

3. Western Han Precedents: Depictions of a Harmonious Imperium

The wild and fantastical animals that appear on this door and in other tomb reliefs from Shanbei originated in a style of art that emerged during the Western Han, which was a mixture of Central Asian, Steppe, and regional Warring States period traditions (Kost 2017; Miller 2018; Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens 1994, 2008; Rawson 1989; Rawson 1983, pp. 37–45; Rawson 2006; Psarras 2019). Within this new visual idiom, real and fantastical animals are depicted in motion, often with a high degree of naturalism, while at the same time blurring the boundaries between the known and the imaginary. Concurrently animals also became symbols of human qualities, exotic places, or signs of divine approval or disapproval. Based on the idea of the power of the Han emperor and bureaucracy to order both the animal and human worlds, objects depicting wild and fantastical animals brought into three-dimensional form a utopian vision of many cultures and creatures living in harmony under the Han Empire. Through the use of seriation, distinctive popular designs echoing this general theme were created in the imperial workshops spread out across the empire, inspiring copies made by local workshops (Miller 2018).

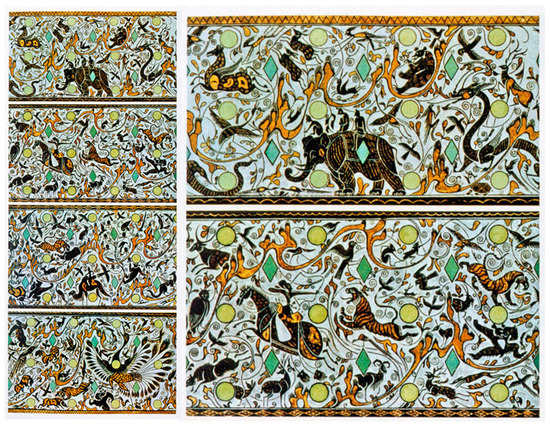

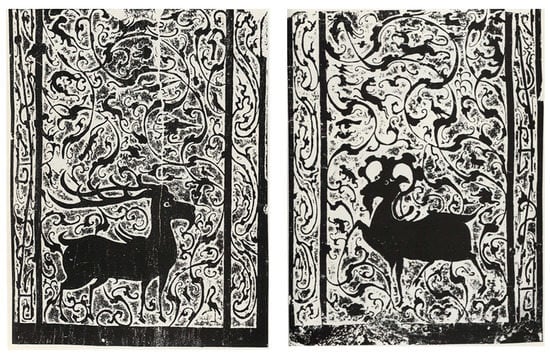

The depiction of animals on two surviving types of objects created during this period—bini 俾倪chariot fittings and mountain-shaped censers—provide strong visual precedents for the animals depicted in Eastern Han tombs from Shanbei. Bini were large decorative fittings that reinforced permanent joints on ceremonial chariots, which were buried with members of the imperial family or others of high rank. On a bini excavated in Sanpanshan 三盤山, Hebei, from the tomb of a king of the Zhongshan state (ca. 90 BCE), real and fantastical animals playfully tumble in a fabulous landscape of swirling clouds: a motif which developed out of patterns on lacquers and textiles from the state of Chu 楚 (704–223 BCE). They are joined by foreign people, including figures riding on an elephant, a mounted archer, and a man riding a camel (Figure 4). In the four registers, deer, rabbits, foxes, and mountain goats climb, perch on, or leap from an undulating line, or the line’s craggy mountain-like extensions bears rest or strike various poses, and tigers appear singularly in scenes of combat, or as the mounted archer’s prey. Fantastical creatures include a large dragon and phoenix, a tianma, a bixie 辟邪 (a winged hybrid), and early depictions of xian. The motif of the mounted archer, the profusion of tigers, and the figures on the camel and elephant all reference and/or are adapted from visual cultures to the north, south, and west of the Han Empire (Wu 1984; Rawson 1983; Benningson 2005, p. 347). By the time this chariot ornament was cast, the decorative pattern of wild and fantastical animals and the yunqi cloud motif was quickly becoming ubiquitous across media (for lacquer objects, see Powers 1983, pp. 286–88).9

Figure 4.

Artist’s rendering of a panel from an inlaid bronze chariot ornament from Sanpanshan, Hebei. Western Han dynasty, ca. 90 BCE (After Zhonghua renmin gonghe guo chutu wenwu zhanlan zhanpin xuanji 1973, p. 85).

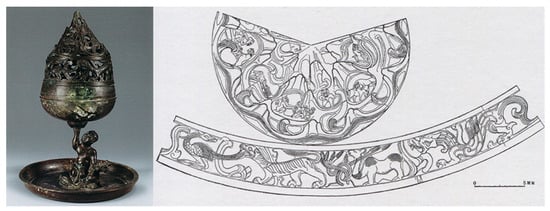

Additionally, appearing in the mid-Western Han are mountain-shaped censers (boshanlu), which transform the yunqi and animal motif into three-dimensional forms (Munakata 1991, p. 29) (Figure 5).10 These bowl-shaped vessels have conical tops with holes that allow for the release of smoke. Typically, the peaks that make up the top of the censer have several clearly demarcated secondary hills with “space cells” in which humans and animals are depicted. A mountain censer that provides a good sense of animal imagery emerging from the imperial workshops comes from the tomb of Lady Dou Wan 竇綰 (ca. 113 BCE), who was a consort of Prince Liu Sheng 劉勝 and a member of the Han imperial family. Sitting in the midst of a round basin, a smiling, half-clad figure sits on a hybrid animal while holding the censer aloft. Four large animals prance across the belly of the censer: a dragon, camel, bird, and tiger; their bodies are intertwined in swirling lines.11 Within the space cells above are scenes of animal combat, animal–human combat, and a man leading a cart; a lone tiger and bear can be found in the craggy folds of the mountain.12 As in the case of the decoration on the bini, the style of the depiction, as well as the motifs of the camel, animal combat, and the man leading a cart, are derived from the visual culture of groups living along the northwestern frontier of the Han Empire (Rawson 2006, pp. 80–81).13

Figure 5.

Bronze boshanlu from the tomb of Lady Dou Wan (ca. 113 BCE) (After Zhongguo shehui kexue kaogu yanjiusuo 1978, Figure 17).

A comparison of the imagery on the Sanpanshan bini to an Eastern Han tomb lintel from Mizhi 米脂, Shaanxi, demonstrates how wild and fantastical the animals in Eastern Han tomb reliefs are from Shanbei, possessing analogous animal forms, behaviors, and environments. On the lintel, a tiger, dragon, deer, foxes, owl, crane, and other birds and animals inhabit a swirling cloudscape. They are joined by a xian and a rabbit pounding the elixir of immortality: an addition to the earlier repertoire of animals on the bini connected to the Han immortality cult. The tops of the two side panels depict a raven and a frog in circles, animals that were said to live in the sun and moon, respectively, and imply that the action is taking place in Heaven. The form of the animals on the lintel, similar to those on the bini, suggests plasticity and movement, with the animals intertwining or mimicking the yunqi motif. In addition, many have the same friendly demeanor that Miller (2018, p. 92) has noted regarding Western Han bear mat weight sculptures, which she describes as “soft, almost smiling, even as they growl at their audiences.” In Shanbei, tigers possess a similar quality and are depicted wagging their tails and smiling as they roar (Figure 3 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Top: Immortal frolicking with animals in an undulating landscape/cloudscape. Mizhi, Shaanxi. Eastern Han dynasty (After Zhonguo huaxiang shi quanji vol. 5, Figure 63). Bottom: Line drawing of the top two registers on the Sanpanshan bini.

Based on reliefs with some surviving pigments, stone carvings from Shanbei also demonstrate a shared interest in polychromatic surface decoration and ornamental patterns with their Western Han predecessors (Miller 2018, 2022).14 Some of this is suggested by the stripes on the body of the tiger on the lintel from Mizhi: details which were further accentuated with paint in other reliefs in the region. This interest in surface decoration and ornament is also seen in reliefs that depict the yunqi and animal motif as the background for larger figures—as can be seen on the west wall in the Yanjiacha tomb (Figure 7; this is the same tomb whose plan appears in Figure 2).

Figure 7.

Side panels on the west wall of the Yanjiacha tomb (After Dai and Li 1983, Figure 2.3).

4. Harmonious Postmortem Realms

As Dramer (2002) has demonstrated in a study of tombs from Henan and Shandong, Eastern Han carved doorways functioned as key elements for organizing and regulating mortuary rituals and social initiations between the living and the dead. While this is most likely also the case in Shanbei, the imagery on the doorways on which these wild and fantastical animals appear suggests a strong emphasis on the journey and postmortem transformation of the deceased. The truncated nature of the pictorial program of tombs in Shanbei blurs our understanding of the deceased’s final destination but suggests that the tomb could have been viewed as a place of transcendence, a way station, or Heaven itself, with the tomb door functioning as a passageway through which the deceased could freely enter/exit (Tseng 2011, pp. 225–32; Hu 2006, pp. 102–3).

In this understanding, the motif of wild and fantastical animals, with or without yunqi, performs two basic functions depending on their placement around the door or passageway. The overall composition on the outer portion of the side panels suggests ascendance as if the deceased is floating upward on currents of swirling qi. Here, wild and fantastical animals could potentially serve as guides, or they may indicate the harmonious nature and secure safe passage during the deceased’s journey (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 6). The lingzhi-shape of the yunqi motif in some tombs further suggests the deceased’s ascension and transformation in the paradise of Xiwangmu or Heaven.15

In the inner portion of the panels framing the door, wild and fantastical animals are also key components in representations of the world of immortals/and or Xiwangmu and her consort Dongwanggong 東王公 (King Father of the East), who is depicted sitting on top of pedestal-like mountains (see the side panels in Figure 3).16 Here, we find birds, bears, deer, foxes, owls, qilin, tianma, and tigers cavorting on or hovering around their central peaks. On some door panels, a dragon also emerges from below, encircling the central pedestal/mountain peak, which similar to the vertical composition of yunqi on the same side panels, also suggests ascension. Rather than snarling and threatening predators and hybrid monsters, wild and fantastical animals in both compositions are symbolic of the transformation of the unknown, and of potentially hazardous postmortem worlds, into harmonious spaces free of danger.17

At the same time, the animal and yunqi patterns continue on many lintels, which include images of the sun and moon, transferring this felicitous imagery into the heavens (Figure 3 and Figure 6).18 On some tomb doors in the lower portion of the lintel, wild and fantastical animals also appear either parading/prancing with xian or as part of hunting scenes. For example, the lower part of the lintel of the tomb of Wang Deyuan 王得元 (d. 101), excavated in Suide, depicts a winged dragon/tiger hybrid, bixie, qilin, phoenix, and various birds parading left with a xian holding lingzhi at the front of the procession. Stalks of lingzhi separate the animals, and the scene ends with a rabbit pounding on the elixir of immortality (see Zhongguo huaxiang shi quanji 2000, vol. 5: Figure 74). Although elements of this imagery, such as the way lingzhi is depicted, are unique to the region, the basic motif of auspicious animals and immortals is common in other Eastern Han tomb reliefs as well.

What is more unique to the region is the popularity of hunting scenes on the lower portion of lintels and the frequency with which they include or are combined with fantastical animals, suggesting a potential conflation of the significance of hunting imagery and depictions of these animals in otherworldly scenes in Shanbei. We can see this in the doorway in Figure 3, where two mounted archers take aim at a tiger, fox, and bird, flanking several mythical animals, including a tianma, dragon, and qilin. On this relief, the wild and fantastical animals could be read as two separate categories—prey and auspicious imagery—but other reliefs in Shanbei blur such a simple dichotomy. For example, on a lintel from a tomb in Mizhi, the deceased couple appears in a pavilion in the center of the composition. Their wings, the turtle and raven on either side of the pavilion (symbolizing the sun and moon), and two immortality motifs—a fox and a hare pounding the elixir of immortality—are signs of the deceased’s transcendence in Heaven. On either side of the pavilion, two hunters turn backward in their saddle and take aim at a deer and a horned, long-tailed ungulate; a third archer appears on foot on the lower left shooting up toward the ungulate. Both of the mounted archers have bear-like ears and do not appear to be human; the one on the right rides a two-horned dragon–tiger hybrid (Figure 8). While more ubiquitous scenes may be included to represent a pastime that the deceased can enjoy in the afterlife, compositions such as this one suggest that hunting scenes take on additional meanings and functions in the ascension of the deceased and may have been included as a supplementary safeguard against the dangers that awaited the deceased in the afterlife (Wallace 2010).

Figure 8.

Tomb door lintel from Dangjiagou 黨家溝 Mizhi, Shaanxi (After Wallace 2011b, Figure 8a).

5. Conclusions

Wild and fantastical animals populate the carved lintels and side panels of Eastern Han tomb doors in Shanbei as important transition zones between the world of the living and the dead and potential portals through which the deceased could pass to and from the tomb. Often climbing and/or merging with the yunqi motif, the treatment of the animals’ bodies, interest in their movement, and the felicitous world in which they are important components are based on a hybrid artform that emerged in the mid-Western Han as an expression of an expanding and harmonious empire. Although elements of their depiction were originally derived from Central Asian and Steppe art, by this time, these animal forms would have been “domesticated” and played an important role in the ascension and transformation of the deceased, insuring their safe passage into the beyond. The preference for such imagery in these tombs may roughly be based on two circumstances: a nostalgia for the Han imperial past (Wallace 2018) and a familiarity with non-Chinese visual traditions due to their geographical location. At times these “Others”—the various groups of unfamiliar peoples amidst which the Han colonists lived—may have been conflated with the dangers awaiting the deceased (Wallace 2011b). The choice to adopt earlier animal forms and compositions insured that even these potentially dangerous challengers were subsumed into the harmonious worlds awaiting the deceased.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | That is not to say that the animals that were part of this group did not have specific associations during the Han dynasty. For studies of individual animals see Bush (2016) (qilin, bixie, and other hybrids), Furniss (2005) (owls), Hayashi (1992) (deer), Kinoshita (2005) (bear), Hu (2018) (elephants), Olsen (1988) (camels), Till (1980) (winged hybirds), Xie (2011) (qilin), and Wang (2020) (camels and elephants). For a study of images of the mounted archer and xian, which appear alongside these animals and provide further meaning to the group, see Wallace (2011a, 2018). |

| 2 | For a review of a number of motifs on these doors and their relationship to the ascensions of the deceased see Hu (2006). |

| 3 | For more on the regional characteristics of these tombs, the history of the region, and previous scholarship see Wallace (2010). For a study of Eastern Han tomb reliefs around Lishi 離石, Shanxi, where the government moved after the loss of control of the Shanbei region see Ruitenbeek (2008). |

| 4 | Another unique regional characteristic of these reliefs is that many of the details were added later using colored pigments, which means that many of them have been lost to time. (Xin and Jiang 2000, pp. 13–14; Barbieri-Low 2007, p. 88). In addition, rubbings, the most common way in which Eastern Han tomb reliefs are reproduced in modern publications, fail to translate the intricacies of the designs. For examples of stone reliefs with that still have some of the pigments preserved (see Shanxi sheng kaogu yanjiu suo and Yulin shi wenwu guanli weiyuan hui bangong shi 2001 and Yulin shi wenwu baohu yanjiusuo and Yulin shi wenwu kaogu kantan gongzuo dui 2009). |

| 5 | Some animals are more helpful than others. For depictions of several spunky domesticated animals, including a horse kicking a man in the stomach, see Zhongguo Han huaxiang shi quanji 5: Figure 120. Some animals in reliefs from Shanbei also appear in both categories we would label wild and domesticated. These include camels, raptors, and rabbits. The last appear as prey in hunting scenes, but also frequently as animal helpers in the court of Xiwangmu and sometimes pulling immortal chariots through the sky; see Zhongguo Han huaxiang shi quanji 5: fig, 203. For a discussion of elephants in Eastern Han tomb reliefs see Hu (2018). For a discussion of falconry see Wallace (2012). |

| 6 | Many hybrids in Han mortuary art have horns, perhaps because horns implied the capacity to drive away demons (Rawson 2000, p. 159). |

| 7 | For regional variations on the depiction of Xiwangmu during the Han dynasty see Lullo (2005); for a discussion of the characteristics of the depiction of Xiwangmu in tombs in Eastern Han tombs in Shanbei and Shanxi see Ruitenbeek (2008, pp. 153–55). |

| 8 | Door panels are the most formulaic aspect of the pictorial program decorating tomb doorways in Shanbei, and aspects of their imagery is also similar to door panels in other regions. One of the regional characteristics of the door panels from Shanbei is that the winged tiger or dragon seen on the doors from Qingjian is replaced by a one-horned rhinoceros-like creature, which was most likely a regional variation of zhenmushou 镇墓兽 or tomb-guardian creature (Fong 1991, pp. 88–89). On some doorways, additional auspicious birds, animals, and xian fill the empty spaces between the larger motifs (for an example, see Shih 1960b, Figure 20). The repeated formulation of the phoenix, tiger, and dragon, which are associated with the south, east, and west, respectively, probably was meant to properly orient the tomb within the cosmos. However, the dark warrior, which by this time was usually represented as a turtle intertwined with a snake and associated with the north, does not appear on door panels in the region and only sometimes is included in the decoration on the side panels (for examples see Zhongguo Handai huaxiang shi quanji, vol. 5, pp. 1, 10). For more on pushou see Hu (2006, pp. 95–96). |

| 9 | The animals, people, and magical creatures that populate this chariot fitting have been interpreted as auspicious omens of Heaven’s favor (Wu 1984), representations of hunting parks eulogized in Han poetry (Rawson 1983, pp. 40–42), and auspicious imagery meant to drive away evil spirits (Munakata 1991, pp. 22–24). Benningson (2005) has interpreted the chariot fitting itself as an axis-mundi connecting a round heaven (the chariot parasol) to a square earth (chariot box) meant to facilitate the journey of the deceased. |

| 10 | The term boshanlu does not appear in texts until the Six Dynasties period (220–589). For a comprehensive study of mountains censers see Erickson (1992); see also Kirkova (2018) for a review and critique of scholarship on boshanlu. Rather than having a religious significance as many scholars have claimed, she demonstrates in late Han and early Six Dynasties poetry, boshanlu are connected to feasting, erotic love, abandoned women, and the thwarted ambitions of virtuous officials. Rawson (2006) has argued that the shape of hill censors was adopted and adapted from Achaemenid prototypes. |

| 11 | These animals may represent the four cardinal directions, with the camel indicating the north, which in later imagery is represented as the Dark Warrior: a tortoise intertwined with a snake (Tseng 2017). |

| 12 | Ceramic imitations of vessels like Lady Dou Wan’s soon appeared in tombs throughout the Han Empire as mingqi 名器 (spirit articles; See Wu (2011, pp. 87–99) for an extended discussion) specifically produced for burial, some of which were functional and others not, At the same time, analogous imagery also spread to other types of mingqi, including hu 壺vessels and hill jars (zun 尊) (Sun-Bailey 1988). |

| 13 | Boshanlu are often discussed in connection with the development of Han immortality cults: their form is linked to ideas of mountains as axis mundi, and more specifically, to the visualization of the mountain-islands of the immortals in the East China Sea and/or Mount Kunlun, the dwelling place of Xiwangmu. The smoke emitted through the holes of the top of the censer is seen as life-giving qi氣 (spirit/pneuma), and the burning of incense as a way to entice immortals to descend and/or an aid in Daoist ecstatic practices. Kirkova (2018) has called these associations, pointing out the earliest mention of boshanlu connects them to the imperial family, not immortal worlds, and that boshanlu were imbued with multiple meanings in the context of elite life. |

| 14 | For examples of reliefs with surviving pigments from Shenmu see Shanxi sheng kaogu yanjiu suo and Yulin shi wenwu guanli weiyuan hui bangong shi (2001) and from Mizhi, see Yulin shi wenwu baohu yanjiusuo and Yulin shi wenwu kaogu kantan gongzuo dui (2009). |

| 15 | This depiction is heavily indebted to Western Han pictorial conventions where movement across time and space is indicated by swirling clouds and figures that move through the composition, for example on Lady Dai’s black lacquer coffin in Mawangdui 馬王堆 Tomb 3 (ca. 168 BCE) or in the bini discussed above (Powers 2005, 2006, pp. 233–41; Wang 2009). |

| 16 | These representations are based on the Han belief that immortals inhabited mountainous realms, which included floating immortal islands in the East China Sea, or Mount Kunlun, the abode of Xiwangmu. |

| 17 | The most evocative literary source that suggests the dangers that the deceased may encounter in the afterlife is the third century BCE poem, “Zhao hun 招魂 (Summoning the Soul)” For a full translation see Hawkes (1985). An inscription from an Eastern Han tomb in Shanbei voices similar sentiments: Ah, the enlightened does not follow, oh, the refined has died an early death, he has left the white sun and descended, his honorable name was cut short and not extended. His spirit floats among animals, roaming to the east and west. I am fearful his soul will be confused, I sing for him to return and be restored. Do not go about recklessly, still something poisonous may befall his spirit, and he may encounter misfortune…(trans. Based on the text provided in Zhang 2005, pp. 62–63; for an additional discussion see Hu 2006, pp. 102–3). |

| 18 | For depictions of the sun and moon in Han art see Tseng (2011, pp. 277–97). |

References

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. 2007. Artisans in Imperial China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benningson, Susan L. 2005. Chariot Canopy Shaft Fitting: Potent Images and Spatial Configurations from Han Tombs to Buddhist Caves. In Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shines”. Edited by Cary Liu, Michael Nylan, Anthony Barbieri-Low and Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 347–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Susan. 2016. Labeling the Creatures: Some Problems in Han and Six Dynasties Iconography. In The Zoomorphic Imagination in Chinese Art and Culture. Edited by Jerome Silbergeld and Eugene Y. Wang. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Yingxin 戴應新, and Zhongxuan Li 李仲煊. 1983. Shaanxi Suide xian Yanjiacha Dong Han huaxiang shi mu 陝西綏德縣延家岔東漢畫像石墓 (An Eastern Han Tomb with Pictorial Carvings in Yanjiacha, Suide, Shaanxi). Kaogu 考古 3: 233–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dramer, Kim Irene Nedra. 2002. Between the Living and the Dead: Han Dynasty Stone Carved Tomb Doors. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York City, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, Susan N. 1992. Boshanlu Mountain Censers of the Western Han Period: A Typological and Iconological Analysis. Archives of Asian Art 45: 6–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Mary H. 1991. Tomb Guardian Figurines: Their Evolution and Iconography. In Ancient Mortuary Traditions of China: Papers on Chinese Funerary Sculptures. Edited by George Kuwayama. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- Furniss, Ingrid. 2005. Two Owls. In Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shines”. Edited by Cary Liu, Michael Nylan, Anthony Barbieri-Low and Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, David. 1985. The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Minao 林巳奈夫. 1992. Monban to mon wo mamoru kami 門番と門を守る神 (Gatekeepers and Sprit Guardians of the Door). In Ishi ni kizamareta sekai: Gazseki ga kataru kodai Chūgoku no seikatsu to shisi 石に刻まれた界: 画像石が語る古代 中国の生活と思想 (A World Engraved in Stone: Pictorial Carvings and Ancient Chinese Life and Thought). Tōkyō: Tōyō Shoten, pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Jie 胡傑. 2006. Shanbei Dong Han huaxiang shi mu mumen quyu shen yi tuxiang hanyi zhi kaobian—yigai diqu huaxiang shi mu mumen buwei shang chuxian de ruo gan zhongyao zhenyi ticai zuowei lunshu de zhongxin 陝北東漢畫像石墓墓門區域神異圖像涵義之考辨——以該地區畫像石墓門部位上出現的若干重要神異題材作為論述的中心 (Connotation Discrimination of Gods Portrayed in Stone Tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty—Taking Important Subjects about Gods and Spirits in Tomb Door of Northern Shaanxi as a Narrative Centre). Zhejiang yishu zhiye xueyuan xuebao 浙江藝術職業學院學報 4: 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Zhu. 2018. Forms of the Elephant: A Pendulous and Sinuous Trunk-A Study of Images of the Elephant from the Perspective of Sino-Foreign Exchanges in the Han Dynasty. Chinese Studies in History 51: 229–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Hiromi. 2005. The Bear Motif during the Han Dynasty. In Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shines”. Edited by Cary Liu, Michael Nylan, Anthony Barbieri-Low and Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 414–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkova, Zornica. 2018. Sacred Mountains, Abandoned Women, and Upright Officials: Facets of the Incense Burner in Early Medieval Chinese Poetry. Early Medieval China 24: 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, Catrin. 2017. Heightened Receptivity: Steppe Objects and Steppe Influences in Royal Tombs of the Western Han Dynasty. Journal of the American Oriental Society 137: 349–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chen. 2019. Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220) Stone Carved Tombs in Central and Eastern China. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lin 李林, Kang Lanying 康籣英, and Zhao Liguang 趙力光. 1995. Shanbei Handai huaxiang shi 陝北漢代畫像石 (Han Dynasty Pictorial Carvings from Shanbei). Xi’an: Shaanxi Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lullo, Sheri A. 2005. Regional Iconographies in Images of the Queen Mother of the West. In Recarving China’s Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the “Wu Family Shines”. Edited by Cary Liu, Michael Nylan, Anthony Barbieri-Low and Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 391–95. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Allison. 2018. The Han Hybrid Style: Sculpting an Imperial Utopia. In Dialogue with the Ancients: 100 Bronzes of the Shang, Zhou, and Han Dynasties: The Shen Zhai Collection. Edited by Patrick K. M. Kwok. Singapore: Select Books, pp. 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Allison. 2022. Painting Bronzes in Early China: Uncovering Polychromy in China’s Classical Sculptural Tradition. Archives of Asian Art 72: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munakata, Kiyohiko. 1991. Sacred Mountains in Chinese Art. Chicago: Krannert Art Museum and Urbana-Champaign. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Stanley J. 1988. The Camel in Ancient China and an Osteology of the Camel. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 140: 18–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, Michėle. 1994. Pour une archéologie des échanges. Apports étrangers en Chine-transmission, réception, assimilation (Toward an Archeology of Exchanges: Foreign Contributions and China-Transmission, Reception, Assimilation). Arts Asiatiques 49: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, Michėle. 2008. Inner Asia and Han China: Borrowings and Representations. In New Frontiers in Global Archaeology: Defining China’s Ancient Traditions. Edited by Thomas Lawton. Beijing: AMS Foundation for the Arts, Sciences and Humanities, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Martin Joseph. 1983. A Late Western Han Tomb Near Yangzhou and Related Problems. Oriental Art 29: 275–90. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Martin Joseph. 2005. Zaoqi Zhongguo yishu zhong de jingling yu zaiti 早期中國藝術中的精靈與戴體 (Spirits and Motion in Early Chinese Art). In Gui mei shen mo: Zhongguo tongsu wenhua cexie 鬼魅神魔: 中國通俗文化側寫 (Ghosts and Demons: A Profile of Chinese Popular Culture). Edited by Pu Muzhou 蒲慕州. Taipei: Maitian chuban, pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, Martin Joseph. 2006. Pattern and Person: Ornament, Society, and Self in Classical China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin. 2019. Sources of Han Décor: Foreign Influence on the Han Dynasty Chinese Iconography of Paradise (206 BC-AD 220). Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, Jessica. 1983. Commanding the Spirits: Control through Bronze and Jade. Orientations 29: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, Jessica. 1989. Chu Influences on the Development of Han Bronze Vessels. Arts Asiatiques 54: 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, Jessica. 2000. Cosmological Systems as Sources of Art, Ornament, and Design. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 72: 133–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, Jessica. 2006. The Chinese Hill Censer boshan lu: A Note on Origins, Influences, and Meanings. Arts Asiatiques 61: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenbeek, Klaas. 2008. The Northwestern Style of Eastern Han Pictorial Carving: The Tomb of Zuo Biao and Other Eastern Han Tombs Near Lishi, Shanxi Province. In Rethinking Recarving: Ideals, Practices, and Problems of the “Wu Family Shrines” and Han China. Edited by Cary Y. Liu and Naomi Noble Richard. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 132–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shanxi sheng kaogu yanjiu suo 陝西省考古硏究所, and Yulin shi wenwu guanli weiyuan hui bangong shi 榆林市文物管理委員會辦公室. 2001. Shenmu Dabaodang: Han dai cheng zhi yu mu zang kaogu bao gao 神木大保噹: 漢代城址與墓葬考古報告 (Shenmu Dabaodang: An Archaeological Report of the Remains of a Han Dynasty City and Tombs). Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Hsio-Yen. 1960a. Early Chinese Pictorial Style. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr University, Bryn Mawr, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Hsio-Yen. 1960b. Han Stone Reliefs from Shensi Province. Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America 14: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sterckx, Roel. 2006. The Bestiary of the Han. In A Bronze Menagerie: Mat Weights of Early China. Edited by Michelle C. Wang. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Bailey, Suning. 1988. What is the Hill Jar? Oriental Art 34: 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Till, Barry. 1980. Some Observations on Stone Winged Chimeras at Ancient Chinese Tomb Sites. Artibus Asiae 42: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Lillian Lan-ying. 2011. Picturing Heaven in Early China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Lillian Lan-ying. 2017. Incense Burner (Boshan lu). In Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties. Edited by Zhixin Jason Xu. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 152–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Leslie. 2010. Chasing the Beyond: Depictions of Hunting in Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs (25–220 CE) from Shaanxi and Shanxi. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Leslie. 2011a. Betwixt and Between: Depictions of Immortals (Xian) in Eastern Han Tomb Reliefs. Ars Orientalis 4: 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Leslie. 2011b. The Ends of the Earth: The Xiongnu Empire and Eastern Han (25–220 CE) Representations of the Afterlife from Shaanxi and Shanxi. International Journal of Eurasian Studies 1: 232–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Leslie. 2012. Representations of Falconry in Eastern Han China (A.D. 25–220). Journal of Sports History 39: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Leslie. 2018. A Biographical Approach to the Study of the Mounted Archer Motif during the Han Dynasty. In Memory and Agency in Ancient China. Edited by Francis Allard, Katheryn M. Linduff and Sun Yan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene Y. 2009. Why Pictures in Tombs? Mawangdui Once More. Orientations 40: 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jianzhong 王建中. 2001. Handai huaxiang shi tonglun漢代畫像石通論 (A Discussion of Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs). Beijing: Zijin Cheng Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yu 王煜. 2020. Handai daxian yu luotuo huaxiang yanjiu漢代大象與駱駝畫像研究 (Research on Images of Elephants and Camels during the Han Dynasty). Kaogu 考古 3: 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 1984. Sanpan shan Chariot Ornament and the Xiangrui Design in Western Han Art. Archives of Asian Art 36: 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2011. The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Chen 謝辰. 2011. Lüè lùn hàndài de qílín xíngxiàng 略論漢代的麒麟形象 (A Brief Discussion on Depictions of Qilin during the Han Dynasty). Zhongyuan wenbo 中原文博 10: 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Lixiang 信立祥, and Yingju Jiang 蒋英炬. 2000. Shaanxi, Shanxi Han huaxiang shi zongshu 陝西, 山西 漢畫像石綜述 (A Summary of Han Dynasty Pictorial Carvings from Shaanxi and Shanxi). In Zhongguo huaxiang shi quanji 中國畫像石全集 (Collected Works of Chinese Pictorial Carvings). Jinan: Shandong Meishu Chubanshe, vol. 5, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yulin shi wenwu baohu yanjiusuo 榆林市文物保護研究所, and Yulin shi wenwu kaogu kantan gongzuo dui 榆林市文物考古勘探工作隊. 2009. Mizhi Guanzhuang hua xiang shi mu 米脂官莊畫像石墓 (A Tomb with Pictorial Stones from Guanzhuang, Mizhi). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Li 張俐. 2005. Shanbei Handai huaxiang shi yu Chu wenhua 陝北漢畫像石與楚文化 (Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs from Shanbei and Chu Culture). Wenbo 文博 3: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo huaxiang shi quanji. 2000. 中國畫像石全集 (Collected Works of Chinese Pictorial Carvings). Jinan: Shandong Meishu Chubanshe, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo shehui kexue kaogu yanjiusuo 中國社會科學院考古研究所. 1978. Mancheng Han mu 滿城漢墓 (Mancheng Han Tombs). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonghua renmin gonghe guo chutu wenwu zhanlan zhanpin xuanji. 1973. Zhonghua renmin gonghe guo chutu wenwu zhanlan zhanpin xuanji 中華人民共和國出土文物展覽展品選集 (A Selection of Items from the Exhibition of Excavated Cultural Relics from the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).