2. The Order of the Unclean and Criticism of Religion Science

“Religious entities […] are ultimately rootless, fluid, liable to become unfocussed and to flow into other experiences. It is their nature always to be in danger of losing their distinctive and necessary character. The sacred needs to be continually hedged in with prohibitions. The sacred must always be treated as contagious because relations with it are bound to be expressed by rituals of separation and demarcation and by beliefs in the danger of crossing forbidden boundaries” (

Douglas [1966] 2002, p. 67).

In recent decades, the study of religions has undergone thorough reform, involving the deconstruction of previous bodies of knowledge, the challenging of basic assumption, and the placing of quotation marks around terms such as religion and secularization, requiring a critical approach to and fundamental reexamination of each term based on the ideological and interpretive systems shaping each meaning. This process began in the late 20th century with criticisms on the main tenets of the modernist research of religion. Prominent scholars such as

Talal Asad (

1993),

J. Z. Smith (

1998) and

Bruce Lincoln (

[2003] 2006) criticized both the conclusions of their predecessors—world-famous modernist researchers such as

Rudolph Otto (

[1917] 1958),

Gerardus Van Der Leeuw (

[1933] 1986), and

Mircea Eliade (

[1956] 1987)—and their attempts to formulate generalized definitions to provide a conceptual framework for discussing all types of religions. Thus, for example, following James H. Leuba’s book from 1912 on psychological study of religion, that lists fifty different meanings for the word “religion”, Smith argued that the gaps and differences between them may not frustrate any ability to use it, but “it can be defined, with greater or lesser success, more than fifty ways” (

J. Z. Smith 1998, p. 281).

5When a term refers to both past and present, cultures both near and far, supernatural and faith-based phenomena as well as those related to economic, political, or cultural system, any agreement on its meaning becomes invalid. This conclusion undermines the claim (identified mainly with the phenomenological discussion of religion, as in Van der Leeuw and Eliada) that religion is an element essential to every human culture.

These scholars and their colleagues proposed economic, gender, post-colonialist and even post-humanist critiques of religious studies (

Boyarin 1998;

Mahmood 2004;

Masuzawa 2005;

Cornwall 2012;

Orsi 2016;

Chidester 2018). Despite the significant differences between them, they share the claim that the lack of a coherent and orderly theoretical basis undermines the validity of religious studies as a discipline in its own right, and as one capable of generalizing characterizations. Recent research presents religious studies as an area anchored disciplinarily in history, anthropology, cultural and political studies, arguing that the use of concepts and presuppositions borrowed from one culture for the analysis of other cultures in other periods is usually artificial and deceptive, and moreover, detrimental to the quality of data collection and analysis. It places “religion” in an ideological background anchored in Western thinking, particularly the intersection of colonialism, nationalism, capitalism and liberalism in 19th century Europe. This conclusion was emphasized by Talal Asad, who argued in his famous book

Genealogies of Religion that “[…] there cannot be a universal definition of religion, not only because its constituent elements and relationship are historically specific, but because that definition is itself the historical product of discursive processes” (

Asad 1993, p. 29).

6Timothy Fitzgerald (

2000), for examples, argues in “Religion, Religions, and World Religions: Religious Studies—A Critique” that the modern concept of “religion” was born together with the rise of modern Western capitalism and individualism. The basic connection isn’t new—Max Weber wrote about the Protestant roots of capitalism already in the early 20th century (

Weber [1905] 2001)—however, Fitzgerald is equipped with a subsequent viewpoint and instruments that enable a more complex understanding of the ideological aspect—the concealed aspect, as he puts it—fundamental to the development of the study of religions. He ties the development of the discipline together with the emerging separation between the public sphere and individual life and freedom in the West, and the establishment of the study of “inner religion” as the outcome of the coping with a secularizes work that pulls the rug from under ancient religious assumptions. Whereas Fitzgerald’s position that the study of religion needs to be examined purely from an institutional and systemic perspective has also been criticized (

Schilbrack 2012), the basic principle that “religion” is not an absolute and eternal concept, but an ideological construct contingent on time, place and culture, is commonly accepted in contemporary research.

A more moderate version of Fitzgerald’s position, that accepts the gist of his argument but is warier of all-embracing generalization, may be found in Brent Nongbri’s

Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept (

Nongbri 2013). Like his predecessors, Nongbri finds it difficult to define the concept. He rejects the assumption that religion and faith are extratemporal ideas that have always been present in different ways in human cultures—a hypothesis he finds both in popular discourse and, regrettably for him, in the literature—and argues that although the word “religion” recurs time and time again in ancient times, it is essentially a modern concept.

7 However, despite Nongbri’s skepticism, and unlike Fitzgerald, he does not entirely reject the concept and its use, but only seeks to refine the research questions, methods, scoping of the disciplines and naturally the resulting conclusions. Following

Benson Saler (

1993, p. 157), Nongbri claims that what is needed is not a better definition of the term religion, but the understanding that this is a restricted and restrictive term, hance its use as a general and comparative category must be significantly reduced. The solution he proposes is specific usage that examines which interests are at stake in formulating the definition of the concept, who are the definers and what their purpose is, as well as renounces the study of “religion” as such in favor of a narrower and more precise study of religious narratives, practices and specific perspectives. Aa a byproduct of this approach, the proposed method is self-reflection that examines with the same degree of earnestness both the objects of study and the concepts and methods used for their examination.

To a significant degree, the Order of the Unclean is aligned with the conclusions of critical religious scholars such as Nongbri and Fitzgerald, as stated explicitly in some of the Order’s writings presented below. As a work of art, the Order does not conventionally meet familiar typologies of religions, and it may be said that already in its fictional turning to the past, it fully embodies the view of religion as a modern concept, as if it were an example for a critical study in the discipline. The Order has no community of faith nor a conventional system of beliefs, laws and customs. It has no rituals, history, or official or non-official clergy, sites of gathering or pilgrimage, etc. Even when the Order exhibits images and texts reminiscent of religious phenomena—such as “scriptures” in the form of the mythical Ro’akhem, the Lexicon of Principles, which is a kind of corpus of religious laws and terms, and Epistles to the Faithful, formulated as contemporary religious homilies—and even when it creates houses of worship and sculptures of deities inspired by ancient mythologies, these are texts and images explicitly publicizes as part of contemporary artworks.

Nevertheless, the very fact that the entire project is based on an invention, and that the concept of religion on whose basis the

Order has been created is a social construct rather than an eternal and universal entity, is used by Meshullam as a point of departure rather than a conclusion. The fact that the

Order of the Unclean is not a religious text par excellence, the symbolic and “historical” representation in which is subject to a contemporary conceptual-art logic, and that the discussion within it is mainly outside the perspective of religious studies, does not mean that it does not dialogue with and is not influenced by various theological views. As I’ll show below, the

Order responds to a variety of theological and cultural views and polemics, offering interpretations and developments. I will also highlight the relation between theological and national elements in the artist’s oeuvre, arguing that the reference to theology, and to ancient religions in particular, is used by Meshullam to examine local and modernist nationalist views. Inspired by the insights of researchers such as

Jane Blocker (

2015) and

Nikos Papastergiadis (

2012), and out of a view of art and particularly visual art as a medium based on excess, somewhat liberated of any specific and harsh ideological subordination (

Soker-Schwager 2022, pp. 49–74), I discuss the

Order as a project that uses art to think of religious, social and historical frameworks, design and reconceptualize them in a way that undermines while at the same time validates them. Consistent with his statement in “The First Epistle to the Faithful” that “No truth is better founded than that of a false messiah admitting to his falsehood” (

Meshullam 2012, p. 6), instead of taking sides in the controversies between different religions, between religion and secularism, and between history and fiction, the

Order of the Unclean takes advantage of artistic license to juggle with their different conclusions, and instead of deciding among the various positions, it illustrates precisely the polemic attitude embodied in their strife, and reflects on the origins and necessity thereof.

8 3. The Genesis of Ro’akhem

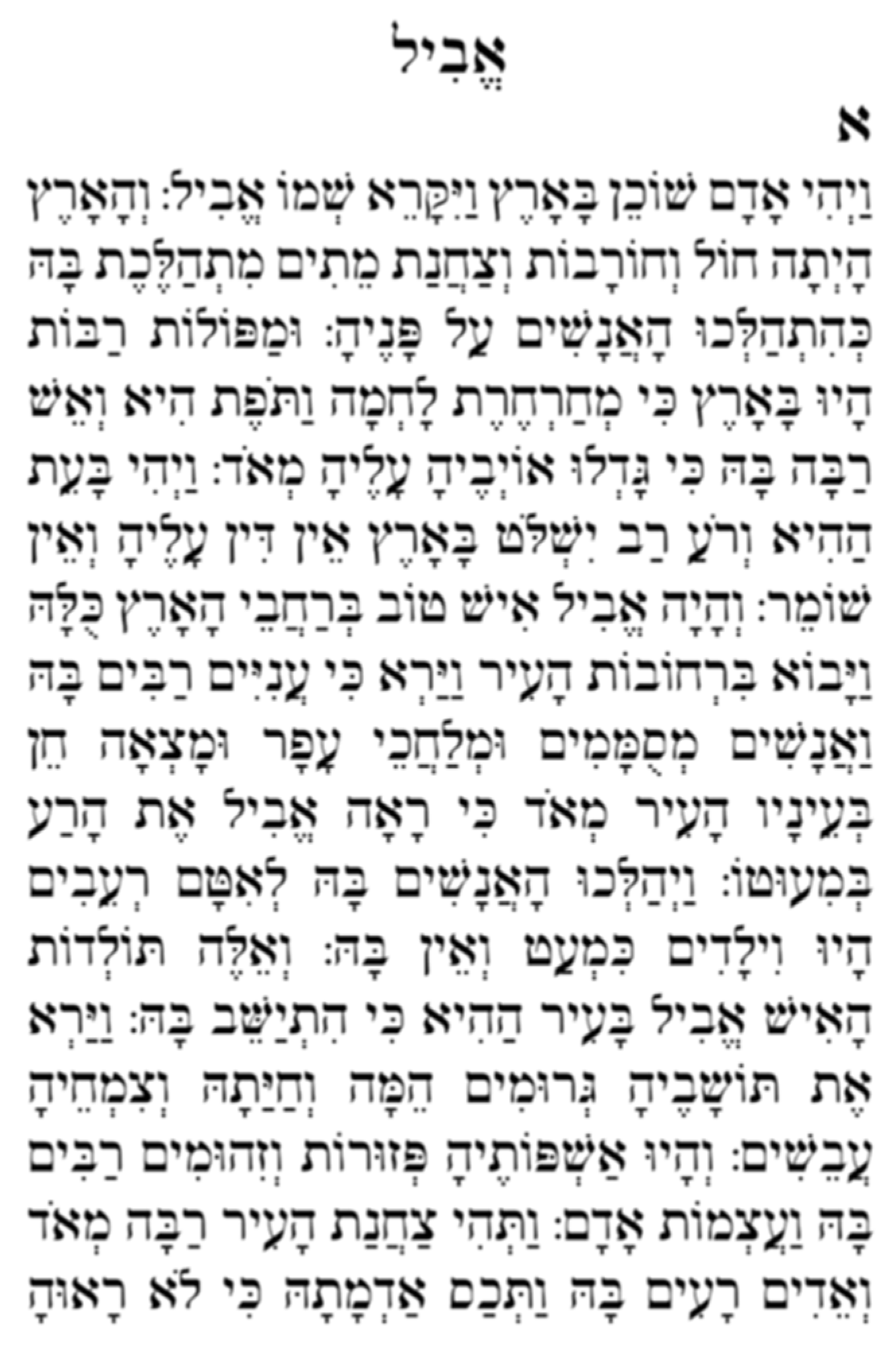

“And a man lived in the land called Ivil. And the land was sand and ruins, and the stench of the dead walked within it as people would have upon it”. (

Meshullam 2005, p. 1 (Ro’akhem: 1.

Figure 1)).

This is how the

Book of Ro’akhem begins, presenting the genealogy of the eponymous character, who first appeared in 2005. Ro’akhem’s was born to Ivil and to a she-dog he had adopted, as “in those days, intercourse with a beast was akin to intercourse with a human” (

Meshullam 2005, p. 3). Using quasi-biblical language, the book’s 146 pages unfold a dystopic, nightmarish reality of death, sickness, violence, and physical and moral degeneration, wherein Ro’akhem appears—a prophet whose name play on the Hebrew words “evil” and “shepherd” in the second person plural possessive.

Who is Ro’akhem? The manifesto of the

Order of the Unclean tells us that “Ro’akhem first made his bubbly voice heard in 2005, five years before the Uncleanliness Era, and he is the one who named himself, while dictating his complex doctrine to the founder of the Order”, no other than the artist Assi Meshullam (

Meshullam 2009a). The description paints a picture of Ro’akhem as a metaphysical entity revealed to the artist and as though speaking out of his body, but then the manifesto qualifies this mysticism by explaining that “Ro’akhem is not a deity or any independent entity. The voice of Ro’akhem is the voice emanating from deep within the belly of the cultured person. It is the voice of sincerity that combines rational thought with man’s instinctive gestures—with no hypocrisy, no need for apologies or guilt feelings” (ibid.).

“Ro’akhem”, the manifesto continues, “represents the healthy doubt nesting in the thinking person’s body and mind. It is the natural and undeniable instinct of the member of modern culture, it is the voice of the original, fundamental self, made up of the intuitive combination of a thinking brain and a creative body, of thought and strength, of spirituality and passion” (ibid.).

The manifest then proceeds to define its own title: “Uncleanliness is not a constant condition. It shifts and shivers, clings and releases, examines and wonders”. In an interview with him, Meshullam explained that he chose the “path of uncleanliness” because “we are conditioned into classifications of yes and no, good and bad, black and white, holy and profane, but these are mythical concepts rather than something that truly exists. For me, that is part of the power structure of religion that I seek to dismantle” (

Amir 2012).

The artist also explained the name of the project as follows: “Order connotes order and Uncleanliness lies outside the order, so that on the one hand I focus on resistance and transgression, while on the other I approve of and assume it” (ibid.).

In 2009, four years after the

Book of Ro’akhem was published and in parallel with the establishment of the

Order of the Unclean, Meshullam published a second book called

Lexicon of Principles (

Figure 2). This book is decidedly different from the first. While the

Book of Ro’akhem unfolds a mythical narrative replete with violence and dystopic description of transgressions between humans and beasts and between humans and other humans, the Lexicon is a kind of manual—a collection of rules and terms that determine the principles of the

Order and their “unclean” interpretation. Divided into 22 volumes according to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, each of its definitions is accompanied by explanations and references. Sometimes, the explanations are technical, brief and informative, and sometimes they are elaborate, providing details on the history of the term in question, as well as Meshullam’s interpretation. This, for example, is the article “Sanctity”:

“Sanctity is a quality attributed to certain objects or creatures (see “Creature”), by the various religions (see “Religion”). A holy thing is ascribed as an essence that is dependent not on the thing itself, but rather on God (see “God”) or other transcendent beings (see “Being”). By virtue of its declaring of all things as unclean (see “Unclean”), by virtue of its disavowal of their real (see “Real”) existence of transcendent beings, and by virtue of its belief in basic class equality (see “Equality”), the Order of the Unclean avoids sanctifying things. Sometimes, the Order grants a symbolic (see “Symbolism”) status to certain objects or creatures (including plants, animals and humans), but this status is limited strictly to ritual or creative (see “Creativity”) purposes, and has nothing to do with sanctity or essence (see “Essence”) that does not emanate from the object or creature itself” (

Meshullam 2009b).

Note the lexical character of the brief definition, formulated mainly in the negative. It provides a very short and partial explanation of the common term—a quality the text ascribes to objects or creatures, derived from transcendent beings—and reminds the reader that the Order denies the existence of such beings, and therefore the very essence of sanctification.

A slightly different type of definition is provided for Judaism:

“Judaism is the most ancient religion of all three great monotheistic religions (see “Religion”). Christianity (see “Christianity”) was an outgrowth thereof, and it played a significant role in the emergence of Islam. Judaism provided the platform for the establishment of the Order of the Unclean, and many ideas included in the Doctrine of Uncleanliness are inspired thereby (sometimes out of agreement and identification, sometimes out of opposition and the search for an alternative—always out of skepticism). Certain structures (see “Structure”) organizing Jewish conceptions are used by the Order, which casts its own contents (see “Parasitism”) therein (see also “Bible”)” (

Meshullam 2009b).

This article also presents a very basic description, but unlike the negative definition of sanctity, it highlights a distinct and fundamental link, as well as an ongoing dialectic relation between Judaism and the Order. The former is the source of the latter, and Jewish concepts and ideas shape the contents of the Order—whether out of agreement or controversy and criticism—hence the reference to it as parasitical, i.e., using Judaism not only as a starting point but as a host through which the Order develops and acts.

This idea also appears in the Epistles to the Faithful—a collection of nine epistles written by Meshullam (aka Baal HaLoa). The epistles are written in a style reminiscent of religious preaching, and address, in the second person plural, “my brothers and friends” the “believers”, using a homiletic rhetoric characterized by pathos, manipulative logic, and pseudo-theological formulas. In these epistles, Meshullam seeks to deconstruct concepts such as divinity, faith, freedom, impurity, and various religious processes. They are imbued with the anarchist and apparently antireligious spirit characterizing large parts of the project, and seems to relinquish any familiar religious dogma.

In the Second Epistle, however, the author explains his choice to interpret and dispute Maimonides by associating his belated liberation with previous background: “My choice of a Jewish thinker may be related to my origins […] related even to my early years, before we were granted free access to the Tree of Knowledge” (

Meshullam 2012, p. 14). According to Baal HaLoa, Maimonides is a rationalist who “does not hang on to innocent and ridiculous beliefs like a blind person, but studies sublime knowledge with power and reason rare in the realm of faith”, which makes him a worthier rival in the eyes of the author. “Why should I waste my time on so many low-lying bushes when I can chew the branches of one mighty tree”, he concludes (

Meshullam 2012, ibid.).

The

Order of the Unclean offers a broad range of ideas, practices, images and religious and theological concepts,

9 taking advantage of the artistic license of not being bound by a certain historical narrative or a given religious worldview. Theoretical vagueness affects many parts of the project, whose structure is somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, the story of Ro’akhem is that of a prophet and charismatic preacher who leads a community. On the other, his voice does not emanate from another’s mouth, but from the reader’s belly, “issues from the bowels rather than the heavens” (

Meshullam 2009a). The

Order is described as a “godless religion” and a “heretic religion”, opposed to believing in transcendent being and based on total skepticism. The

Order’s texts, particularly the Lexicon, refer to conventional expressions of sanctity as political moves designed to accumulate power and control. As the mirror image of the “saint” the

Order posits that of the “unsaint”—a believer who has mastered the Doctrine of the Uncleanliness and taken practical part in developing and disseminating the contents of the

Order. The term “unsaint” is the negation of “saint”, as stated in Chapter 55 in the

Book of Ro’akhem: “Sacred am I in my uncleanliness, and unclean in my sanctity, I am the generator and I have desecrated”.

On the face of it, under the guise of religious language and style, Meshullam offers a parody of religion, anchored in a secular worldview. Ridicule seems to resonate loudly from the text: God is not God, saint is unsaint, sanctity is profanity, the myth undermines itself, commandments are personal and flexible, redemption is an institutional manipulation and uncleanliness is an article of faith. These statements illustrate both the spirit of the project and some of its limitations. Meshullam is not a theologian, and some of the claims in his writings and works rely on weak theoretical foundation. The very exclusion of uncleanliness as something that exists “outside order”, for example, attests to a partial and even incorrect understanding of the concept in various religions and cultures.

10Nevertheless, the conceptual vagueness is due less to an incoherent or poorly formulated theological viewpoint, and more to an artistic attempt of using religion—with all the residues and practices it connotes—as an agent of disorder. Here also lies the camp value of the

Order of the Unclean, which turns the religious system into a carnival of multiple sources of inspiration. Let us examine the project according to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s definition of camp as “a collection of the startling, juicy displays of excess erudition, for example; the passionate, often hilarious antiquarianism, the prodigal production of alternative historiographies; the “over” attachment to fragmentary, marginal, waste or leftover products; the rich, highly interruptive affective variety; the irrepressible fascination with ventriloquistic experimentation; the disorienting juxtapositions of present with past, and popular with high culture. […] a glue of surplus beauty, surplus stylistic investment, unexplained upwellings of threat, contempt and longing […]” (

Kosofsky Sedgwick 2003, p. 150).

Clearly, the Order of the Unclean meets almost every camp characteristic on this list. It fuses various religious elements, remote histories and geographies, medieval illustrations, Judaism, Christianity and an array of ancient religion, together with fantasy stories and sleeves of metal albums, all using excess visual and textual language, rich in contexts and contradiction.

Such an understanding may suggest a reading of this project as a parody, but in this article, I would like to adopt not only Kosofsky Sedgwick’s definition of camp, but also her proposal that we discuss it under the framework of “reparative reading”. Kosofsky Sedgwick refers to this in her above-quoted article “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading”. This article rails against critical interpretation based on what the author calls “paranoid reading”.

11 In particular, she criticizes Butler for viewing camp as an ironic and critical practice, claiming that “To view camp as, among other things, the communal, historically dense exploration of a variety of reparative practices is to do better justice to many of the defining elements of classic camp performance” (

Kosofsky Sedgwick 2003, pp. 149–50). In this spirit, and as opposed to interpretations of the project by curators and critics over the years that will be discussed later, according to which the

Order of the Unclean uses religious terms and images to express secular criticism,

12 the following sections propose a post-secular analysis, to the effect that together with challenging conventional value systems and religious beliefs, the project validates and enriches them, and that more than a critique of religions, it offers to view them as a complementary element for comparative religious and secular thought.

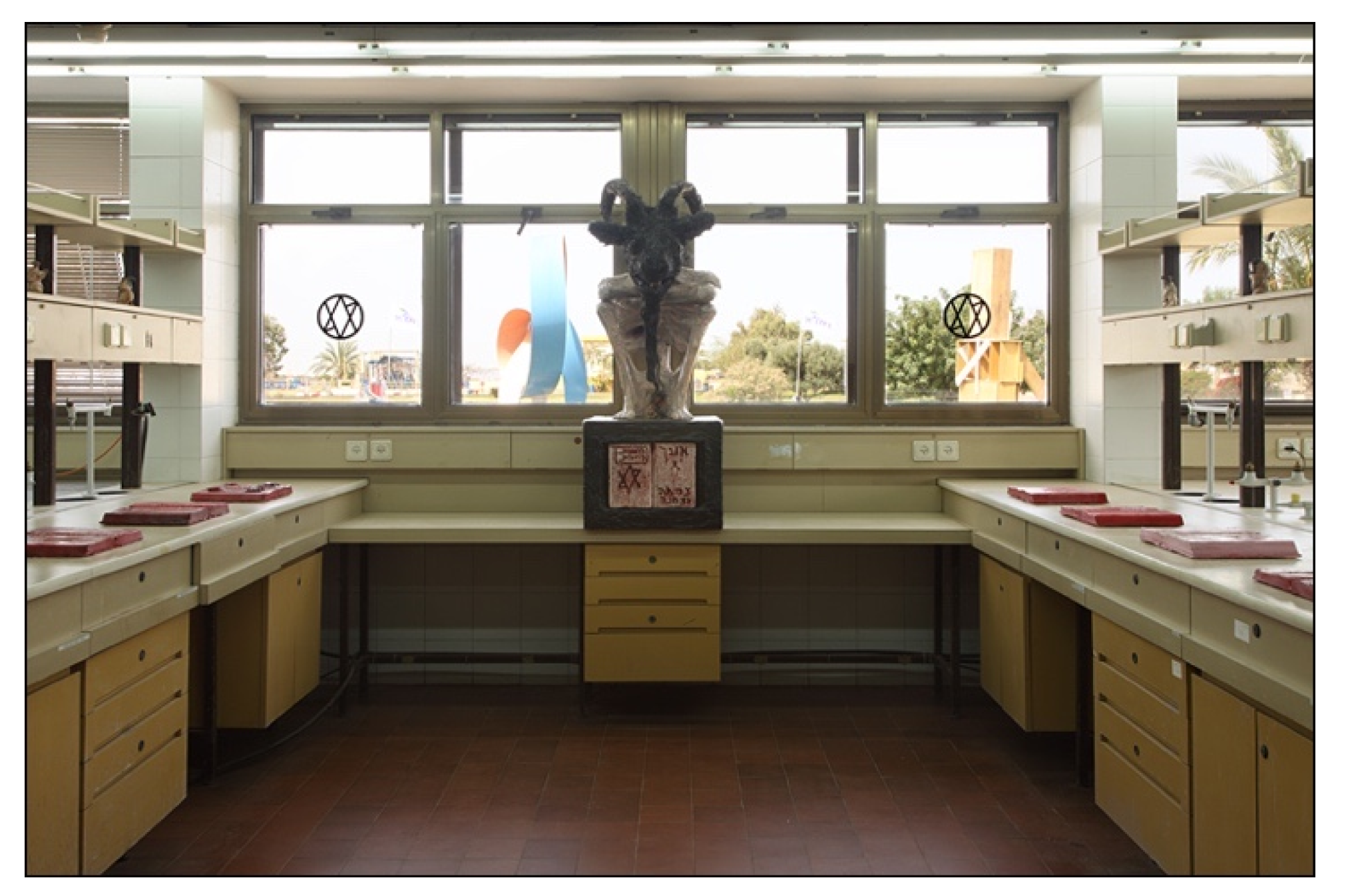

13 4. The First Temporary House of Uncleanliness: The Order of the Unclean and the Scientific World

Meshullam presented images of the

Order of the Unclean in four exhibitions, called Temporary Houses of Uncleanliness. The first was titled “Idolatry”, part of the group exhibition

Redemption via

the Gutters, curated by Galia Yahav in 2010 at the Shafdan wastewater treatment plant in Rishon LeZion (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). This large exhibition, featuring about twenty artists, sought to address “the normative perceptions of what is considered proper and improper, pure and impure, spoken and silenced in contemporary literature”.

14 The various sections of the exhibition were presented in rooms and inner and outer spaces of the Shafdan complex, whereas “Idolatry” was presented in a local laboratory. The lab tables supported “scripture” sculptures and figures of preachers with human bodies and animal heads. At the center of the room, upon a “Chair of Abominations” sat a sculpted figure with a sinewy body and a goat head, who’s posture was inspired by a statue of Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec Lord of the Underworld. The central part of the body was missing, and it looked like a pair of crossed legs above which, on top of a spindly and stomach-less spine, a rib cage was afloat, to which the goat’s head and a pair of cross arms were attached (

Figure 4). The statue was placed on a black box in front of which was embedded a sculpture of a holy book open at a double spread, in which a dense text was written in red—lines from the

Book of Ro’akhem, which bore the large captions “Haze, Scraping and Stench” and “The Big Abominations”. Also seen was “Tethagram” (the combination of two Hebrew letters Teth, expressive of the symbiotic relation Meshullam identifies between purity and impurity—both words starting with that letter), as well as a rhombus-like symbol that will appear also in future works, which combines the iconic image of the Kabbalist Ladder of the Sefirot

15 and medical depictions of the human body.

Other exhibits included in “Idolatry” were positioned along the lab workstations as though they were raw materials, scientific manuals or objects in an experiment. On the tables, next to drainage ducts, taps and switches, lay open sculpted books and figures with human bodies and heads of bulls, deer, donkeys, goats and sheep (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). The creatures were sculpted to seem like preachers in the midst of homilies. They stood erect, wearing capes, their hands open wide, and some of them holding staffs. All sculpted books were designed as open at the center, their “pages” bearing red-colored texts from the

Book of Ro’akhem and the

Lexicon of Principles, ornamented with arabesques of the letter Teth and images reminiscent of illustrations of biblical figures. In some of the books, the bodily-sculptured aspect was further stressed using colored clay reliefs stuck on the pages, and deep engravings. The Tethagram logo was once again glued to the room windows and chemical cabinet.

Curator Yahav interpreted these works as part of a critical discourse. “The concept of redemption, senseless as it may seem from the heights of 2010”, read her curatorial article, “is discussed in the exhibition in critical terms, as a potential procedure, but also a preliminarily mendacious one—a false prophet even—of freedom. The works in the exhibition represent, each in its own manner, the internal bargaining with the discursive regime to which they are subjected, exposing the artistic convention they transcend” (

Yahav 2010). Regarding “Idolatry”, Yahav adds that it is “a visual representation of pushing the boundaries where the absoluteness of corruption produces purity, addition to alienness, to haze, to stench, to the priests and agents of evil produces a clean sanctity of unity”. In a press interview on the eve of the opening, Yahav explained that “The automatic horizon of this entire exhibition is almost inevitably the toilet bowl, i.e., Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain” (

Armon-Azoulay 2010). She proceeded to develop the similarity and difference between the work of art and the elimination of bodily wastes arguing that “There’s a similar sound to the ‘wastewater plant’ and ‘redemption through the gutters, but these are two contradictory procedures: the artistic act is to let the wastewater overflow, to speak of the unspoken. The exhibition makes a statement about the right to life in a political sense” (ibid). Further emphasizing the critical perspective, Yahav added: “The meaning of this work is accumulated by the way it tells its prohibitions, charting the discursive regime wherein it operates and with which it bargains—that is political action to me” (ibid).

Yahav’s interpretation maintains a dichotomous structure, with the difference being that instead of “flowing with” (and thereby obscuring) the structure, the works and their interpretation “reveal” its existence. Meaning is “accumulated by the way it tells its prohibitions, charting the discursive regime wherein it operates and with which it bargains”. This interpretation is anchored in critical theory, and in institutional critic in particular (

Bryan-Wilson 2003). It lays on the basic assumptions shared by the work and its interpretation regarding the differences and gaps between science and art, reason and monstrosity. According to this interpretation, Meshullam plants fictional, mythical and anti-rationalist objects, images and texts, in order to expose and criticize fictional, mythical and anti-rationalist aspects that still exist in a world whose stated values are grounded in realism, rationalism and scientific thought.

My point is that this is a possible critical reading, but not a necessary one. In what follows, I show that the sharing of common assumptions indeed confirms the exhibition’s curatorial agenda, but misses out on a fundamental element embodied in Meshullam’s work. Reading this element does not require the revealing of hidden principles, since it is explicit and expressed in the most immediate visual and textual layers of the exhibition. Thus, absurdly enough, the revealing of certain meanings Yahav identifies in the exhibition conceals the obvious meanings embodied therein. In other words, Meshullam does not make art in order to expose the “deviations” that “corrupt” the scientific structure, but in order to highlight the fact that deviations can be an inherent part thereof.

In his book

We Have Never Been Modern (

Latour [1991] 1993), Bruno Latour places quotation marks around terms such as “nature” and “science”. He argues that nature is a modern construct created, shaped and applied within specific ideological and historical frameworks. He attributes the oppositions of nature and culture and natural and artificial to a humanist, anthropocentric and modern worldview, fundamental to which is the hierarchic—and as he argues, modernistic—distinction between what is human and what is not. “Modernity is often defined in terms of humanism, either as a way of saluting the birth of ‘man’ or as a way of announcing his death. But this habit itself is modern, because it remains asymmetrical. It overlooks the simultaneous birth of ‘nonhumanity’—things, or objects, or beasts—and the equally strange beginning of a crossed-out God, relegated to the sidelines” (

Latour [1991] 1993, p. 13). These distinctions can shed new light on Meshullam’s work, and particularly the way it relates to the Shafdan labs and their status in the Israeli national ethos.

From with the drainage of the swamps in the early 20th century, through the drainage of the Hula Lake, the construction of the National Water Carrier, the discovery and exploitation of groundwater reservoirs, and the invention of drip irrigation around the middle of the century, to large-scale desalination toward the end of the century, water resource management and related technology development have been central to the Zionist and Israeli policy and cultural ethos (

Gvirtzman 2002;

Zeltzer 2011). This phenomenon has two main reasons. The first is the urgent need for water to provide for a growing population and expanding rural and urban settlement in an area much of which is desert and all of which is affected by frequent droughts and high evaporation rates. The second, strongly related to the first, is related to the modern-zionist ideology of “making the desert bloom”.

16 Viewing the country as a “barren” land that needs to be “flourished”, particularly by agricultural cultivation and afforestation (

Lifshitz and Biger 1996;

Weizman 2015), led to the seeking of water sources to provide for agricultural and urban settlements’ needs, to the installing of pumps and pipes to distribute the water to these settlements, and to developing cost-effective technologies for the reuse of waste and salt water. Added to these needs was a desire to protect nature against the damages of waste disposal, which has severely affected the local flora and fauna in Israel’s early decades (

Siegel 2015).

Established in the 1980s, the Shafdan wastewater treatment plant in Rishon LeZion is thus yet another link in a long chain of national water policies, central to which is the Jewish pioneer, who aspires to be in control of all natural phenomena and resources, deemed as available for his own welfare. It is therefore no coincidence that in this particular plant, Meshullam installed the first Temporary House of Uncleanliness. The most prominent aspect of this House was the nature of the exhibition space. A laboratory is not the natural home of an art exhibition, and science is not the natural context for imaginary monsters. In this exhibition, however, art, fiction and the supernatural have trespassed into the temple of nature, rationality, and scientific research. Scientific formula have been replaced by bleeding scriptures, part spell books, part monuments, the pure raw materials by a diverse medley of substances, and the white-robed professional staff by a series of mutant, exaggerated hybrid figures led by a “lab manager” in the form of a hybrid, skeletal beast.

Latour bases his idea of modernity on two principles: hybridization and purification. The former is the cross-breeding of separate concepts, views or elements, whereas the latter is the apparently contradictory process of maintaining their separation. Modernity, argues Latour, occurs only when the two processes occur in parallel: “

the modern Constitution allows the expanded proliferation of the hybrids whose existence, whose very possibility, it denies” (

Latour [1991] 1993, p. 34. italics in original), and “Modern men and women could thus be atheists even while remaining religious” (

Latour [1991] 1993, p. 33). Hybridization and purification are important elements in “Idolatry”. The former is primarily expressed in the statues that combine human and animal organs, and in the sculpting that combines rough materiality (clay, gypsum, paint, glue), and ready-mades (plastic doll body parts and cheap jewelry). Hybridization is also expressed in the missionary Doctrine of Uncleanliness that informs the exhibition, as for example in Chapter 52 of the

Book of Ro’akhem: “For out of the body, from its uncleanliness, from its filth, from its infliction—from these shall my words issue unto you, from it shall you spread it out of the forest, so that the people are infected by my creed”. It also manifests in a profoundly conceptual sense in the very choice of locating figurines, deities and grimoires in the temple of science. Thus, similarly to Latour, Meshullam does not relegate the monsters to the margins but places them at the heart of culture, and it appears that for both, the innovation does not lie in the very existence of such supernatural phenomena as monsters, but in the willingness to acknowledge the “monster” in the middle of the room.

The encounter of hybridization and purification that is evident in Meshullam’s work is expressed primarily in their very installation in the lab. Latour identify the initial separation of religion and science in the agreement between the Anglican Church and the Royal Society in the late 17th century. Under this agreement, the church enabled the scientist to published their works free of censorship, so long as they remain devoted to apolitical research and avoid issues such as divinity, morality, metaphysics and politics, which the Church sought to keep under its control. The separation between the lab and place of worship, and consequently between secularism and religion, was therefore not motivated by a religious or scientific need, but by the combination of the scientific community’s need to operate with relative freedom and that of the Church to enable scientific research that will not trespass on its sovereignty. Yehouda Shenhav calls it “A sociological deal between physics and metaphysics” (

Shenhav 2005, p. 80. See also

Funkenstein 1986; and

Proctor 1991).

Whereas the separation of church and science was born out of power struggles more than out of any organic intellectual development and essential needs,

17 it allows us to reread the way Meshullam’s work “tells its prohibitions”, as Yahav put it, and propose that Meshullam installs his statues, paintings and scriptures not in order to parodically “secularize” the “remains of theology” that haunt the lab, the gallery, public space and society in general, but to argue that “secularization” in that sense is impossible to begin with. In a way that is implied by Yahav’s interpretation, for example, secularization means pointing to the theological failures and blind spots that have still remained where secularization has yet to complete the mission, and Meshullam’s work, which as an artwork deals in “letting the wastewater overflow”, as mentioned, reveals how the “absoluteness of corruption” produces a “clean sanctity”. In that sense, the criticism lends support to the position of the Anglican Church vis-à-vis the Royal Society, with the difference between the two events lying in the different location of the gatekeeper.

Under the interpretation proposed here, however, Meshullam’s work places both secularism and religion between quotation marks, thereby challenging the very dichotomous separation between the two concepts and the values with which they are identified. Meshullam positions “Idolatry” quite elegantly in the laboratory space. The images are indeed monstrous, but they seem to be comfortable on the tables. While the books are “bleeding”, blood does not pool around them. This is not a space of violence, calamity or apocalyptic prophecy, but one wherein the “supernatural” is “naturally” and even casually blended. The hybrid preachers sanding on the lab workstations do not threaten us with the loss of rationality in case theology is readmitted into science, but serve as a reminder of the sources and motivations the two share. Science, writes theoretician John Gray, “has been used to support the conceit that humans are unlike all other animals in their ability to understand the world. In fact, its supreme value may be in showing that the world humans are programmed to perceive is a chimera” (

Gray 2003, p. 24). Meshullam seems to rise to Gray’s challenge by creating a world where there is no “secular” lab crew faced with demons, monsters and spells taken from the “religious” world. Rather, what we find in that wastewater plant—located simultaneously at the beating heart and the backyard of ultra-modern Israel—are two “orders”, one whose members wear capes and one whose members are dressed in white robes, both of which use formulas, texts and spells in a desperate attempt to understand the world and face its challenges.

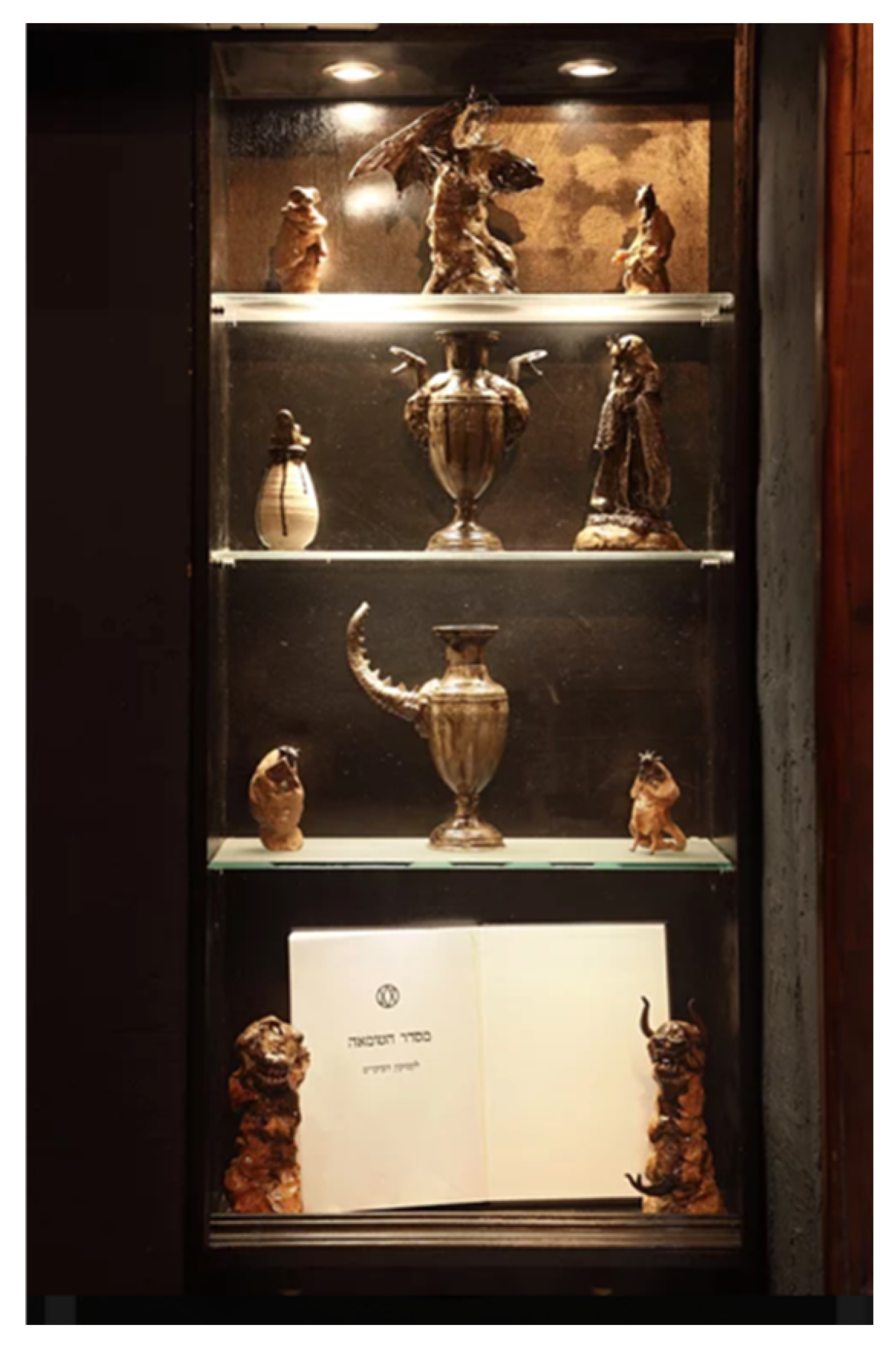

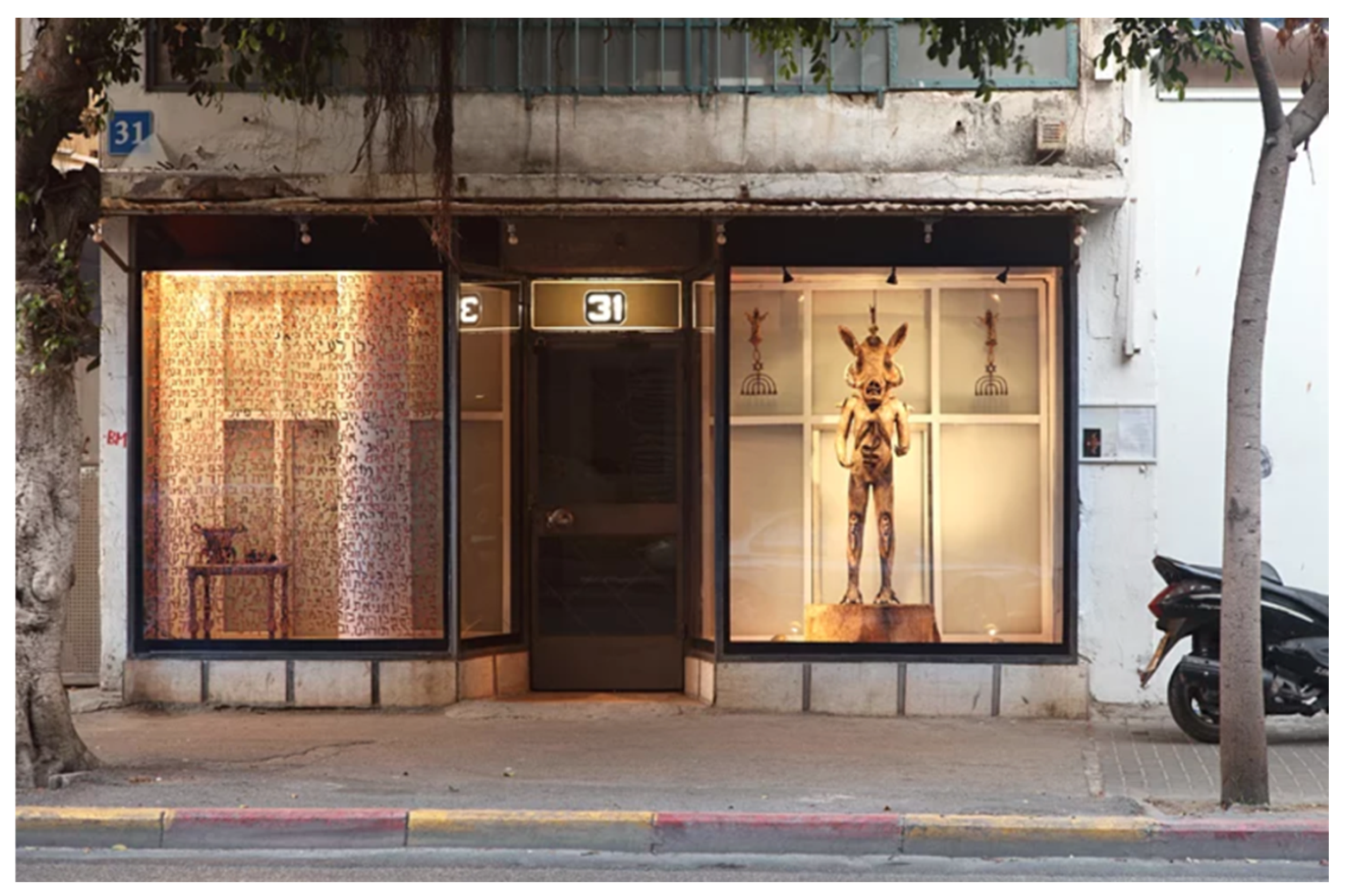

6. The Forth Temporary House of Uncleanliness—Nationalism and the Order of the Unclean

The Fourth Temporary House of Uncleanliness was opened in June 2012 at HaHanut Gallery in downtown Tel Aviv under the title

Baal HaLoa. HaHanut is an independent center for fringe theater active in a small space (previously used as a store, hence its Hebrew name), and its operators turned its display window into a small art gallery. HaAliyah Street, where the gallery was located, is a crowded thoroughfare. It is used for commerce and residence, as well as a traffic route between Jaffa and downtown Tel Aviv and the city center. The Neve Sha’anan neighborhood where it is located has been—and to a large extent still is—a locus of friction, pooling into it some of the major conflicts in Israeli society (

Ben-Dror 2016). In the early 1990s, the New Tel Aviv Central Bus Station was opened at the end of the neighborhood, leading to severe deterioration in the quality of life and services for the local population, which was already disadvantaged (

Cahana and Etinger 2020). That decade also saw the arrival of large numbers of migrant workers in the neighborhood, and by the end of the 2000s, it assimilated thousands of asylum seekers from Sudan and Eritrea.

19During those years, a tiny area of only few square kilometers became a national symbol for the conflict between native, disadvantaged Jewish Israelis and refugees and migrant workers, mostly from Africa, against the background of political incitement, gentrifying real-estate entrepreneurs, social activists and artists, drug dealers and prostitutes. Together with aid organizations and activists from left and right, the distress of the local population attracted the interests of many municipal politicians, parliamentarians and government members, including the prime minister, who participated in demonstrations in the neighborhoods and added fuel to the fire. The conflicts did not skip the houses of worship in the area, as the demographic changes reduced the number of synagogue goers, while at the same time improvised churches for Africans cropped up in basements and private apartments.

20 The violent conflicts that occasionally flared in the neighborhood did not spare its religious centers.

21These characteristics gave the storefront window on HaAliyah Street a very different status from that of the internal exhibition spaces where previous Houses of Uncleanliness were exhibited. How do you deal with “uncleanliness” in a display window facing a sidewalk that looks like a sanitary hazard? What violent political dystopia can you describe in a neighborhood that is already characterized by poverty, crime, political and economic strife, and violent conflicts between social groups?

Meshullam’s response was to dive headlong into the swamp. In the gallery’s black-painted inner space, he hung monstrous animal head statues and placed a vitrine with copies of

The Book of Ro’akhem and

The Lexicon of Principles, as well as tiny “sacred objects” in the form of deities and various mutations referring to ancient mythologies and local deities (

Figure 9). In addition, he planned to hold a series of symposiums with artists and scholars. The core of the exhibit, however, was not displayed in the inner space, but rather in the gallery’s double display window. On its right side, Meshullam placed the “Baal HaLoa” statue—a large figure whose body was reminiscent of a human body with cow legs, and its head seemed like the hybrid of a bull and a boar (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). On its forehead was the Tethagram symbol that had accompanied the

Order of the Unclean from the very beginning, but here, for the first and hitherto last time, it was displayed next to the Star of David, which appeared on both sides of the statue, in both places positioned above another Jewish symbol—the Seven-Branch Menorah—hung upside down (

Figure 10 and

Figure 12).

22 Thus, a fictitious contemporary symbol was juxtaposed with two ancient and familiar ones, next to the head of a monstrous status, also fictitious and contemporary, and at the same time one that refers to ancient paganism. On the left side of the display window, the text of the “First Epistle to the Faithful” was painted in red glass paint under the title “The Creed of the Unanswered Question”.

The Menorah and Star of David are perhaps the most important Jewish symbols. Both recur in Jewish history, both in the Land of Israel and beyond, and both have become official state symbols when Israel became an independent state in 1948. Both also share a complex history, with studies showing that their status has changed over the years. The Menorah was said to have first appeared in the First Temple, as described in the Bible and in visual records from that time on. Nevertheless, as Israel Levin shows, the Menorah turned from a ritual object into a religious symbol only in the Byzantine era, as part of the emergence of a symbolic art concept and in response to the growing visibility of Christian symbols, primarily the cross (

Levine 2000).

The Star of David gained its iconic status even later. As opposed to the quintessentially Jewish image of the Menorah, this symbol appeared in various cultures throughout history, assigned with different meanings in ancient Egypt, in Christianity and Islam, as well as in medieval Kabbalistic circles (

Costa 1990;

Mishori 2000). According to Gershom Scholem, the Star of David became a distinct Jewish symbol only in the 19th century, again in response to Christianity (

Scholem [1948–1949] 2009). It spread gradually among Jewish communities worldwide, becoming, despite its lack of clearly identifiable Jewish roots, the symbol of the Zionist movement and subsequently the center of the Israeli flag.

Symbol transitions across religious and national cultures reflect transformations and struggles characteristic of many nationalist movement, as well as the very concept of nationalism.

23 The relationship between nationalism and religious traditions has been a part of nationalists’ discussions from its early beginning (

Ben-Israel 2019), and the cause of an intense argument that has started in the 1980s, whose echoes reverberate to this day. On one side were the modernist researchers such as

Eric Hobsbawm (

1990),

Ernest Gellner (

1983), and

Benedict Anderson (

1991), who viewed nationalism as a modern social product which creates histories, myths and customs according to its contemporary needs. On the other side was the “primordial” approach led by Anthony Smith (

Smith 1986,

2003;

A. D. Smith 1998),

Adrian Hastings (

1997) and

John Armstrong (

1982), according to whom modern nationalism was not a new or unprecedented phenomenon, but a more recent manifestation of ongoing religious, identity, and community currents with deep historical roots.

24This discussion is particularly relevant to the historiography of the Zionist movement and the State of Israel, whose laws define Judaism as both religion and nationality, privilege Jews on both counts, and support religious mechanisms that shape multiple aspects of the everyday lives of all its citizens, Jewish or not.

25 The Zionist national movement was born in late 19th-century Europe, and was constituted and seen in various senses as a secular movement. However, from its early beginnings and to this day, its development has been legitimized by an ancient biblical myth, traditional prayers expressing longings for Zion, and repeated historical attempts (albeit controversial) to return here (

Almog et al. 1994;

Fischer 2019;

Raz-Krakotzkin 1993,

2005;

Salmon 2001;

Shenhav 2015).

26 Without taking a stand in the modernist-primordialist debate, Yehuda Shenhav proposes to apply Latour’s perspective to point at a double asymmetry embodied therein (

Shenhav 2005). Its first part is embodied in the gap between the debate’s position on the question whether nationalism is modern or premodern, whereas the concept of modernity is acceptable to both sides as a natural and stable datum, rather than a social construct with historical contexts of its own. According to Shenhav, this asymmetry is parallel to discussions on the relation between religion and secularism, with the former seen as a factor in constant, socially engineered motion, whereas the latter is seen as a neutral and constant factor. The second asymmetry Shenhav identifies has to do with the relations between East an d West, with the former seen as more religious, and the latter tending to understate or even deny its religiousness. The outcome of these two asymmetries is the identification of religion and religiosity with the “moderns’ Others”, i.e., the “non-moderns”, most likely also non-Western.

27 Latour, Shenhav concludes, enables us to see through that dichotomous structure. He therefore proposes a basis for a new epistemology, showing that, first, the “modern”—just like the “premodern”—is a practical and discursive category reified in the political field; second, that the two models of nationalism (the primordial and modern) are not contradictory, but rather parallel aspects of modern nationalism; and third, that religion is integral to nationalism, in both the Western and non-Western world (

Shenhav 2005, p. 76).

In this spirit, and similarly to the previous exhibitions’ positionings regarding conflicts in Jewish-Israeli society as presented above, we will find how instead of taking sides, Meshullam’s exhibition is responsive to both, and more than it criticizes this or that stance, it examines their very separation and polarization. As an essentially fictional project, it appears to belong to the modernist side of the discussion, which views traditions as modern inventions designed to serve nationalist goals. However, examining the nature of the symbols in his works, their design and installation, points to a deep attachment to primordial religious elements. In this sense, even if the exhibition unravels the historical links of its sources, it is still bound by them and it is doubtful whether it can (or wants) to break free. This is emphasized by the very juxtaposition of the Menorah and Star of David, with all their religious and national connotations, to the hybrid image of obviously pagan Baal HaLoa, with the Tethagram branded on his forehead.

In juxtaposing old and new symbols, both religious and national, monotheist and pagan, Meshullam does not of course argue that there has been no Jewish history, but illustrates how every incursion into the archive of history necessarily redesigns according to the zeitgeist. His work brings the religious presence simmering at the foundation of national consciousness to the surface, drawing the boundaries of each element’s rights and wrongs. By planting modern national symbols in ancient religious contexts, Meshullam highlights the hybridization and purification practices of religiousness in national space. Whereas in the nationalist discourse the Menorah enters the hall of the nation shorn of both the rituals of the Temple it used to inhabit and the pagan religions literally occupying the same space,

28 and the Star of David is placed at the center of the Israeli flag, far removed from the ancient mystic elements associated therewith,

Baal HaLoa brings both symbols back to different spaces, albeit fictional, but in many senses more real in simulating their cultural environment in previous times. Thus, combining monumentality and transgression, imagined ancientness and complex contemporaneity, enables the viewer to be, if only for a moment, both ancient and modern, religious and nationalist, monotheist and pagan.

The attempted arson of

Baal HaLoa on 21 June 2012, shortly after the opening of the exhibition, forestalled the publication of critical reviews, apart for one comment that could hardly be considered as such, but must have led to the sabotage. On 15 June 2012, a rightwing website featured a post titled “A New Peak in the Vice of Sodom and Gomorra in Tel Aviv” (

Figure 13).

29 Referring to himself as the Big Boss, the writer says he has been exposed to the exhibition while driving in Tel Aviv, and explains that the combination of the figure of a pig looking like “Jesus is always presented” and the “Magen David attached to an

inverted Hanukkah Menorah” (here and below, underlines in original) is designed to “present Judaism and the Jews as inferior to the pig, and the pig as if a deity next to the Jews”. The anonymous writer concludes the post with the statement “

Nazis in the State of Israel”. The post was followed by a brief discussion. Another forum member called Shlomo wondered, “How much would the leftist Jews be willing to pay to become free of the curse of Judaism? […. They] daydream that they are gentiles bought by Jews in infancy”. A third member, zelhar, claimed that the installation promoted atheism rather than Christianity, whereas UM-96 opined that this had to do with a satanic sect.

All this could have been conveniently ignored as anonymous ramblings in an esoteric forum, countless of which are posted daily—had it not been for the attempted arson. The fact that the post did resonate and even result in violence requires that we dwell on it and examine it in relation to previous responses to Meshullam’s oeuvre. As mentioned, no other comments on the exhibition have been published, and it is impossible to tell how the art world would have responded to it had it not been prematurely shut down (due to the property’s owner’s demand, and against the artist’s will

30). Given the consistent nature of the reviews on the previous Temporary Houses of Uncleanliness,

31 we may assume that this would have also been interpreted as a secular “overflowing of wastewater”, i.e., a parodic use of religious elements in order to point at the religious ghosts that still haunt national house as so many mythical monsters creeping in its infrastructure, which the suprastructure of the state institutes and laws seek to conceal with only partial success.

Conversely, the reading proposed here presents the exhibition as critiquing the pretenses of secularism itself to maintain a separation between a national, i.e., “modern” society, and a religious or “premodern” one. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin proposes to examine the Zionist national “secularism” as “the reformulation of the Jewish messianic principle (…) as a political national story in the modern sense. Zionism and the state are seen as the ‘realization of the utopian vision of the Return to Zion’ and as the fulfillment of messianic longings, if only by way of political action rather than a miracle” (

Raz-Krakotzkin 2019, p. 266). Moreover, he argues,

“The messianic element in Zionism derives precisely from the desire to ‘normalize’ Jewish existence, namely the definition of the people of Israel as a nation in the modern European sense. Messianism is therefore not opposed to nationalism, but is an effect of secular nationalism. What makes it unique is the tendency of uncritically accepting the rule (i.e., the European national model)” (

Raz-Krakotzkin 2019, p. 267).

The concept of secular messianism and its attempt to adopt the European model of nationalism while ignoring its contexts, can be used as a model for thinking of the exhibition space, and the array of symbols displayed in it. The Tethagram is composed, as mentioned, of the Hebrew letter Teth (ט), which appears twice within a circle to represent both impurity (טומאה) and purity (טהרה) (

Figure 14). It is shaped like a sharpened version of the Chinese Yin and Yang symbol, which depicts two contradictory but complementary forces, and is also reminiscent of the logo of the campaign for nuclear disarmament designed by Gerald Holtom in 1958, which became one of the symbols of peace movements worldwide. Above all, however, and as highlighted by the colors differences of the Tethagram shape in

Figure 12, it looks like a twisted Star of David—as though its vertices have been partially broken and stretched sideways, with the symmetrical and centralized balance of the triangle system disrupted. In this sense it may be argued that the Tethagram within a circle represents not only the first letter of “purity” and “impurity”, but also a religious-national order that seem to have been deflected, but is still trapped in the same paradigm.

Every discussion of the status of the symbols in the inner context of the exhibition will remain lacking, however, should it not account for their installation in a storefront window, an interim space that straddles the indoors and outdoors, a private piece of property projecting on the public passageway, blurring the distinction between an art exhibition and the center of a religious congregation or national community, in an environment laden with explicit national and religious tensions. Having previously transgressed the conventional boundaries between different practices and discourses, in this exhibition the artist also violated the spatial autonomy of the exhibition, and crossed into the street. In The Lexicon of Principles and N.G.H.P the act of transforming the gallery into a churchlike space maintained ironic distance—the entry thereto was accompanied from the first moment by the awareness that this was a theater of sorts, allowing the visitor to sit on the benches of the faithful and conduct a serious discussion of the relations between art and religion and between observing artworks and participating in rituals. The same was true of Idolatry, which consciously played on the tension between exhibition space and lab. In Baal HaLoa, the ironic distance was erased. Walking past the lighted window displaying religious and national symbols next to monsters, passers-by could not have known that this was an exhibition rather than a house of prayer, and if so, of what religion or sect. The blurring of boundaries between street and gallery, art and reality, has created in intermediate space which has in itself realized the complex state of mind the exhibit sought to introduce. The disruption of separation and neutrality—or rather the pointing to their falsehood—also disrupts the “normalization” of religion in the national framework, that is its bounding within well-defined areas separate from the general sphere, while ignoring the fact that the constitution of the general sphere is anchored itself in secularized messianic elements. Thus, the commenters in the rightwing website were wrong about the malicious intentions attributed to the artist and gallery, but touched a grain of truth: they correctly identified the fact that the exhibition offered to its viewers to be secular, that is messianic, that is religious, that is nationalist, or in other words, to challenge the very position and role of the barriers erected by the modern world between those concepts.