1. Introduction

Renaissance and Mannerist sgraffito decorations were one of the most popular, interesting, and unique ways of decorating the walls of buildings in many European countries. Generally, it consisted of cutting out or scratching patterns in fresh plaster or plasters applied accurately on each other and covered with slaked lime. In this way, decorations imitating elements of rustication and various architectural details were made. Figural representations were also performed on façades using this technique. The artistic effect which is obtained through sgraffito is mainly associated with drawing, graphics, or chiaroscuro painting. Moreover, sgraffito in relation to architecture is used to define both the method and the final effect of wall decoration; the term itself was taken from the Italian sgraffiare, and the earlier Latin exgraffiare or dysgraffiare, which means to scrape or scratch.

The architectural origins of sgraffito date back to antiquity (Egypt, Rome). In subsequent periods, we note a several-fold increase in the popularity of using this technique of wall decoration, also outside Europe (Almohad Caliphate). Islamic influences resulted in the formation of a very original design (Mudéjar Art) in the 13th century in the Iberian Peninsula (

Ruiz Alonso 2019). At the same time, we observe in various countries—including Italy, Germany, and Poland—the appearance of single sgraffito decorations, mainly on sacred buildings. Italy turned out to be a particularly important place, where over the next three centuries the sgraffito technique was improved and the design was enriched.

The appearance of sgraffiti in the countries north of the Alps, mainly under the rule of the Habsburgs, to which Silesia also belonged at that time, is due, inter alia, to the migration of Italian builders and artists, especially those living in Ticino, Grisons and Lombardy. It was they who, at the beginning of the 16th century, and from the thirties of this century in particular, reached the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

In Silesia, the fashion for sgraffito lasted a long time, i.e., about 110 years (1540–1650). Its culmination fell during the period between the last third of the 16th century up to the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War (1570–1620).

During the following centuries, a certain amount of sgraffito decorations, along with the buildings they decorated, fell victim to fires and hostilities; many of them were probably destroyed during reconstructions and renovations; some, with the advent of the baroque, were covered with new plasters and decorations. Those preserved, on the wave of historicism, began to be subjected to restoration actions in 1867 which were carried out by German conservators. These works were continued after 1945 by Polish researchers and restorers. They included a total of over fifty objects, which today give an idea of the scale and beauty of this method of decorating walls.

2. The State of Research

It was only in 2003 that Silesian sgraffiti began to be studied on a larger scale, taking into account the existing knowledge about them which was scattered in numerous publications. The earliest of them (starting from 1853) constituted the fruit of German researchers’ interest in this problem (

Sammter 1853;

Lohde 1867;

Lutsch 1903;

Hahn 1912). Although priceless, as they bring out the issue of sgraffiti from complete non-existence, they turn out to be only a signal of the research problem; at best, they present selected and single decorations. In the 1960s, research into Silesian sgraffiti started to be continued by Polish scholars, among whom Tadeusz Rudkowski, the author of several monographic publications devoted to the decorations in Legnica, was particularly distinguished (

Rudkowski 1967,

1976a,

1976b), as well as conservators Zbigniew Skupio and Stanisław Stec (

Skupio 1979a,

1979b;

Stec 1979,

1982,

1992,

1996,

1997). All this is reflected in the research which has been conducted by the author of this article until today. It showed that the number of decorations existing today, most often in a rudimentary form, is about two hundred. It is supplemented by a list of over one hundred non-existent sgraffiti, which have been inventoried in the form of drawings or photographs, described or at least referred to.

The reference for research on Silesian sgraffiti has become the studies regarding a broader European context, starting with the already historical study entitled

Geschichtliches und technisches vom Sgraffitoputz (

Urbach 1928) through extensive studies devoted to Italian decorations (

Thiem and Thiem 1964) and Switzerland (

Berger 1897,

1909;

Könz and Widmer 1977); up to numerous articles concentrating on single objects or their groups (

Lasinio 1789;

Lange and Bühlmann 1867;

Semper 1868;

Bertram 1966;

Günther 1989;

Kohlert 2001;

Salema and Aquilar 2012;

Payne 2013;

Waisser 2014;

Farina 2016;

Dülberg 2018;

Ruiz Alonso 2020), including one monograph following a conference on sgraffiti conservation methods in various countries and regions (among others:

Klein 2019;

Zahn 2019;

Koller 2019). In this context, it should be emphasized that only Italian, Swiss, Spanish sgraffiti—with particular emphasis on decorations from Seville (

Ruiz Alonso 2002), Czech sgraffiti but only with regard to rustication variety (

Kubec 1996), Polish (

Rudkowski 2006), and, separately, Silesian sgraffiti (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003b) have their comprehensive monographs.

We owe the knowledge about sgraffiti from the area of Silesia to numerous publications which were mostly devoted to individual objects, especially those subjected to restoration, which began in 1867. In 1853 the first publication on Silesian sgraffiti appeared in print in “Deutsches Kunstblatt”, a newspaper of the German Artistic Association and was written by Adolf Sammter. It presented a description of the figural decoration of the sgraffito tenement house at 1 Wjazdowa Street in Legnica. We also owe a lot to the first archival iconographic materials, including the photographs and inventories of Max Lohde, who in 1867 published drawings depicting sgraffito decorations of the castle barn in Czosze (

Lohde 1867) (

Figure 1a,b); a year later, he published a four-part article devoted to sgraffiti in general (both Renaissance and 19th-century ones). The last extensive part of the article was devoted entirely to the description of decorations adorning the buildings of the monastery in Nawojów Łużycki. The first discussion of the conservation works which were carried out on the façades of the “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem” (At Quail’s Basket) house in Legnica became an opportunity to present all the Legnica sgraffiti, known at that time (largely from reports), which comprised nine objects. Its author was the then president of the Legnica Historical Society (Geschichts- und Altertums- Vereins zu Liegnitz)—Richard

Hahn (

1912).

We owe a more complete idea of the scale of the phenomenon in Silesia to the inventory of sgraffito decorations which Hans Lutsch included in his catalog of art monuments from the Silesian Province, and which was published in the years 1886–1903. In this catalog, he noted the presence, in a few cases synthetically (it concerned mainly figural compositions), of 180 cases of such decorations (

Lutsch 1903).

After 1945, an inventory of the Renaissance Silesian sgraffiti was undertaken several times. In 1965, Jadwiga Skibińska estimated their number at around 100 (

Skibińska 1965). Estimates resulting from the research and inventory were extended in 1976 by Tadeusz Rudkowski, thanks to the data obtained mainly from pre-war German studies. This researcher has also provided us with the first extensive article devoted to sgraffiti after 1945. In 1967, the author, who was apparently inspired by Hahn’s report from 1909, published a monograph of ten decorations in Legnica (

Rudkowski 1967). Over time, German researchers, including Lothar

Hyss (

1993a,

1993b), also began to join the discussion on Silesian sgraffiti, but the descriptions and interpretations contained in his article refer mainly to sgraffiti known before 1945.

Descriptions of sgraffito decorations were also included in several MA theses which were prepared at the History of Art Department of the University of Wrocław (

Jędrzejczyk 1972;

Stankiewicz 1978;

Wędzik 1991). The remaining works mentioning sgraffiti come from monographic studies devoted to individual objects. They accompany unpublished historical and architectural studies which were prepared in the years 1960–1990 at the request of the Voivodship Conservators or by the Monuments Conservation Studios (

J. Eysymontt 1959,

1972;

K. Eysymontt 1971,

1979;

Różycka-Rozpędowska 1963,

1971). Stanisław Stec also has great merit in the field of research on the technologies of making and conservation of sgraffiti in Silesia (

Stec 1979,

1982,

1997).

Since the mid-1990s, due to the lack of a comprehensive study covering all the problems connected with Silesian sgraffiti, the author of this work has taken the first steps to develop them. At the beginning, three articles which were devoted to Silesian sgraffito decorations were published. The first one introduced general issues connected with Silesian sgraffiti. The next one dealt with geometric sgraffiti in Silesia (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2000,

2003a), whereas the third one dealt with the conservation of Silesian sgraffiti, which covered actions from the years 1867–1936 (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2001). In 2003, they were joined by the monograph entitled

Sgraffiti in Silesia 1540–1650 (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003b), and then subsequent publications appeared which developed the issues addressed in it and which were elaborated on the basis of subsequent research and findings (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2008,

2010).

4. Sgraffiti in Silesia

During the period of the creation of sgraffito decorations in Silesia, this region, co-creating the Czech Kingdom (which also included Bohemia, Moravia, Upper and Lower Lusatia), belonged to the Habsburg monarchy. The social and religious situation in Silesia (

Figure 2), as in a large part of Europe, was shaped from the 1520s by the Reformation movement. This was important for the renewal of religious and intellectual life. It also contributed to the growth of political independence of society from Catholic royal power.

Despite a great number of political and religious events, from the 1520s until the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, this was a time which was favorable for the development of the Silesian economy and most significantly to us—for the flourishing of art.

Increased economic activity in the 2nd half of the 16th century had a positive effect on construction investments. Lively contacts with Europe, favored by religious ferment, and sometimes simply cognitive or educational journeys, resulted in acquaintance with the latest trends in art and a greater openness in accepting various novelties. People returned from these peregrinations with pictures, graphics, books, stencils and awakened ideas about their own homes and the appearance of towns (

Wąs et al. 2002).

The location of Silesia at the intersection of trade routes had a beneficial effect not only on the economy, but also resulted in an influx of artists wandering these routes and offering their services. They came mostly from the artistic and geographical outskirts of Italy at the time, namely from the area of northern Lombardy and Ticino (around the lakes of Como, Lugano and Maggiore), which obviously influenced many Silesian decorations on the artistic level.

It is probable that one of many such groups created an artistic colony in Brzeg in the 1540s. It left a significant mark on not only Silesian art, but also northern German and Scandinavian art.

It should also be emphasized that in the territory of Silesia, the Renaissance almost hardly occurred in a “pure” classical form. The time when it appeared in the Silesian lands corresponded to the entrance of Italy into the stage of Mannerism.

In the development of Renaissance art in Silesia, we can distinguish stages which were closely connected with social and ideological changes and which from the 1520s were marked by the Reformation, and then, from around 1570, economic and social transformations as well as the counter-reformation activity of the Church and royals. In comparison to the Middle Ages, the group of recipients of artistic creative activity changed. The void left by the end of investment from the Catholic Church was filled by secular and bourgeois patronage (mainly wealthy merchants), but most of all by princely and noble patronage. Wealthy, educated doctors and lawyers also played a certain role.

The basis for new art was created by humanistic culture, which initially took shape in Silesia under the influence of Italy, southern Germany, and Cracow. After the middle of the century, as a result of changes in cultural and religious orientations, contacts with Protestant centers came to the fore in Germany, the Netherlands, and France. At the turn of the 17th century, Rudolf-like Prague became attractive again, especially for Catholic circles in Silesia (

Chrzanowski and Kornecki 1974).

The statement, which was supported by studies, expressing the fact that regardless of the direction of inspiration, the origin of performers and the time of construction, most of the architectural objects erected or modernized at that time in Silesia, both outstanding and inferior, emphasized their belonging to the world of Renaissance art with sgraffito decorations, is of key importance.

During the Renaissance and Mannerism, many different buildings and structures were remodeled and built from scratch in this region, including tenement houses, town halls and other objects such as schools, parish buildings, and fortifications. First of all, however, there was a large group of buildings which were erected thanks to the contributions of princes and nobility, namely manor, palace, and castle residences, a great number of which were the results of remodeling earlier layouts (

K. Eysymontt 2010). They became the showcase for Silesian architecture of the period in question. The most numerous group of sgraffito decorations will be connected with this type of building.

The results of the conducted research and analyzes allowed us to maintain that the first sgraffito decorations reached Silesia at the beginning of the 1540s, thanks to the artists connected with the Italian Parr family who came from the Ticino Bissone. Pioneering investments, however, were created at the initiative of Bishop Jakob von Salz (castle in Bolków), and then the townspeople of Lwówek (town hall), Hans von Schaffgotsch (castles: Gryf, Gryfów, Chojnik) and the Prince of Legnica and Brzeg, Jerzy II (castle in Brzeg). The center connected with the ducal castle in Żary also played a significant role in the spread of sgraffiti in Silesia in its northwestern part.

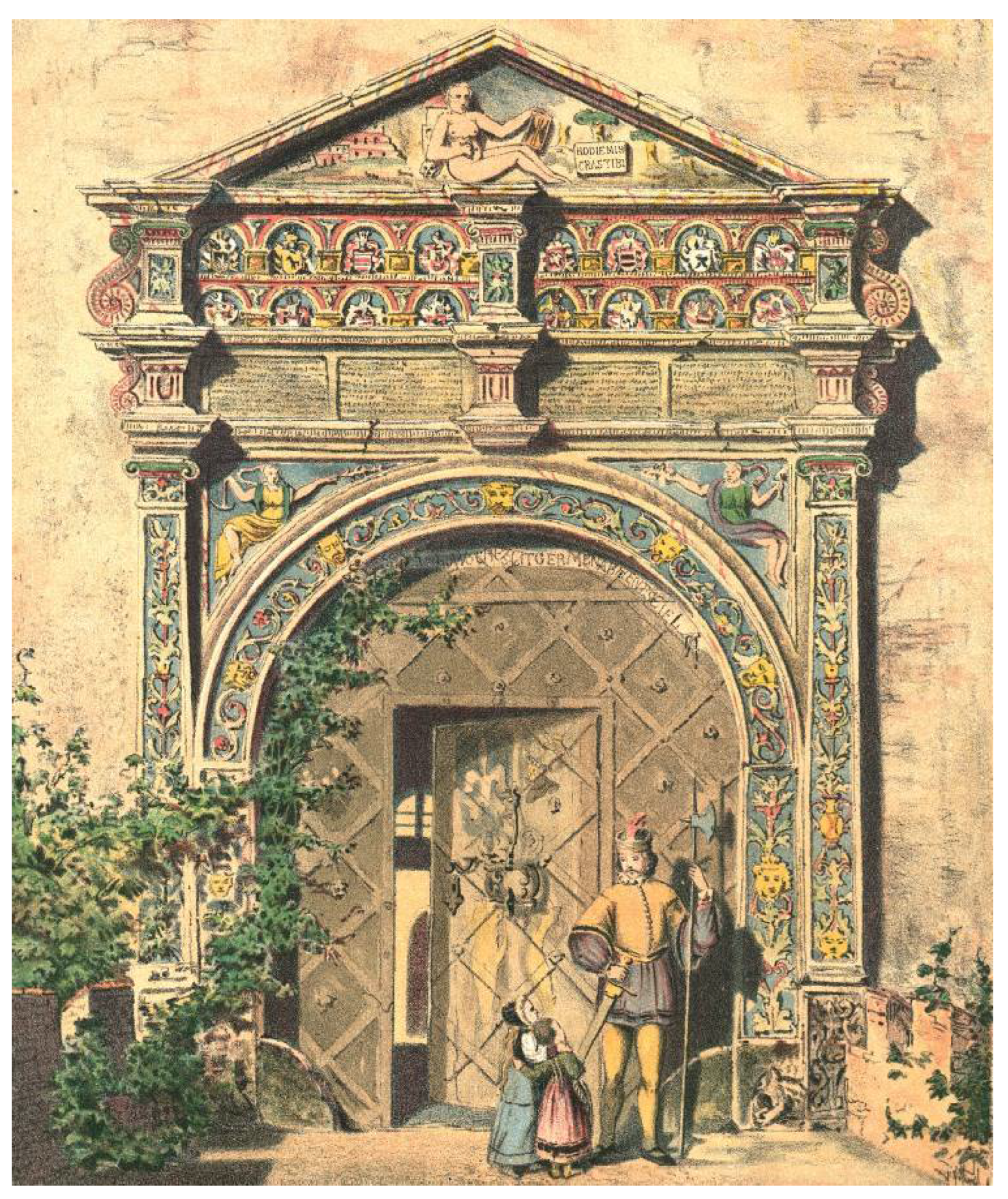

It is also important to state that in the early period, figural compositions dominated in sgraffito design. These include the abovementioned sgraffiti which decorate the town hall in Lwówek (1546) (

Figure 3), the castle Gryf (around 1546) (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the church in Gryfów (1551) (

Figure 6a,b), the manor house in Rudnica (around 1560) (

Pszczółkowski 2013) (

Figure 7a,b), the castle in Prószków (1563) (

Figure 8), the “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem” tenement house in Legnica (around 1565) and the manor house in Zagrodno (1567).

A small number of decorations on bourgeois buildings known to us—only fourteen tenement houses and eleven town halls—can be explained by faster changes in urban construction, which on the one hand caused fires, and on the other, allowed relative ease in modernizing the façades of tenement houses in the spirit of subsequent styles. A significant number of sgraffiti were also destroyed during subsequent renovations and during demolitions of buildings.

Statistical comparisons of preserved or mentioned decorations show that the most frequently decorated objects in Silesia, especially in the second phase, were various residential buildings, i.e., mansions, palaces, castles and castles, which were represented in total by approximately 120 examples.

They give way to decorations of churches, mainly medieval, which comprised 102 objects (three of them figural compositions), including one with use of sgraffiti in the interior (

Figure 3a,b). However, it should be emphasized that decorating objects of worship with sgraffiti on a large scale and unprecedented elsewhere seems to be a peculiarly Silesian feature. The remaining sgraffiti covered various public buildings, i.e., schools and offices (8), then barns (6), city gates (8), cemetery gates and walls, including defensive ones, surrounding churches (5), mills (3), stables (2), cemetery chapels (2), breweries (1), and gatehouses (2).

An important indicator which was taken into account when assessing the artistic level of sgraffiti in a given area was the number of figural representations. This type of design required greater skill from the artists and at the same time a higher level of requirements and wealth from founders.

As for Silesia, we know of about 30 figural decorations, including friezes with medallion portraits and figures placed at the gates (

Figure 4,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). It is a relatively small number (considering, additionally, the fact that none of these decorations has survived in a complete state). The comparison with the neighboring Czech Republic, where there are over 80 of them, is particularly striking. This comparison may, however, be unfair; it juxtaposes Silesia with a country whose material legacy was treated incomparably more favorably by history.

Summing up, it can be said that Silesia, along with a great part of Transalpine Europe, especially that ruled by the Habsburgs, fell into sgraffito madness, making decorations performed with this technique one of the main features of the architecture of the period.

5. Function and Composition of Sgraffito Decorations in Silesia

5.1. Function

Aesthetic value, the main criterion of which is beauty, certainly played a significant role in Silesia as well. It seems, however, that it was not fundamental. An important part of sgraffito in this area was created out of the need to modernize medieval buildings, thus becoming the simplest sign of modernization and at the same time the cheapest way to do it because it did not require major construction investments. This is how decorations on church façades, which we know from many examples, were created. Among them, the most spectacular are the façade of the Wroclaw Cathedral and St. Mary Magdalene Church (

Figure 11).

Sgraffiti also played a significant role in the case of buildings of medieval origin, which underwent renaissance extensions. Covering the façades of these objects with sgraffito decorations made it possible to achieve the effect of merging and homogeneity. It was also sometimes effective in attempts at giving a new order to the façades in accordance with renaissance rules. This especially refers to big medieval castles (e.g., Bolków, Gryf).

Sgraffiti on the façades of newly erected buildings, except for figural sgraffiti, mainly replaced or complemented stone elements of the decor. With this in mind, division elements such as cornices, rusticated corners, and friezes were made using the sgraffito technique on façades which were covered with decorations of an architectural character. For the sake of the homogeneity of the composition, stone window frames, sometimes also portals, were surrounded with separate sgraffito forms. This method was dominant in the first phase of sgraffito use in Silesia. In the 1570s, a new way of using these decorations was introduced, which consisted in covering the entire surface of the façade with a composition with a motif of repeating rustication usually accompanied, although it was not a rule, by window casing and friezes.

The role of figural decorations was different. The examples known to us indicate, apart from the obvious aesthetic aspect, that there were also other reasons for their use. The first one constituted a manifestation of the social position and financial situation of the owner. The second one drew attention to his education and familiarity with art (Scholz’s house in Legnica). Figural compositions, which were placed on the façades of buildings, by using the selection of scenes, became an opportunity to express a message constituting a kind of a showcase for the owner, presenting his views and values.

5.2. Composition

The composition of sgraffito decorations in Silesia depended on several factors. The type of design used seems to be the main one, which was usually directly connected with the skills of performers and the wealth of investors. The dependence on the type of building and its architectural form is also visible. In the case of objects of medieval origin, the existing form was subject to retouching. With regard to buildings erected from scratch, we can guess the conscious shaping of the façade with sgraffito decorations in mind, which took on various composition schemes.

However, no clear predilection for the choice of design, and thus the composition of the object’s decoration, due to its function, was noticed. Single cases concerning objects of a defensive character (castles, defensive walls), where the use of a motif enhancing the optical power of a building was found (Oleśnica, Niemcza), do not allow us, however, to formulate a uniform thesis for all such objects and decorations connected with them, especially in relation to the use of figural sgraffiti to decorate the castle in Prószków.

The schemes, according to which Silesian sgraffiti were composed, differ significantly from those which prevailed in Italy. There, in most cases, the sgraffito decoration was subordinated to the regular structure of the façade and the architectural elements arranged on it, creating the background for them. This dependence is particularly clear in sgraffiti which were made in Tuscany and Rome. Let us add that a special case in Italy is the Lombard sgraffito, which was made in two ways. One of them alluded to the Roman opus reticulatum (e.g., the Sforza Castle in Milan). The second one had some features in common with Spanish decorations (including Segovia), which were created by combining native art with the artistic heritage of Islam (

Ruiz Alonso 2015). Only in small towns on the Italian and Swiss border do we find examples of sgraffiti which clearly dominate over simple architecture and are devoid of clear divisions or even stone detail. Three compositional schemes of decorations were used. We can find all of them in Silesian architecture.

The first of the schemes of Ticino origin used in Silesia can be found on the façades of the castle in Brzeg and mansions in Radzików, Białobrzezie and Słupice. It was based on the use of the sgraffito technique to make corner bossages, “profiled” cornices or flat moldings separating the stories and casings around windows (accompanying stone profiled frames), to which windowsills and pediments were added. The remaining areas of walls were covered with plaster with an uneven surface (the castle in Brzeg and manors in Radzików (

Figure 12), Białobrzezie and Słupice (

Figure 13).

The second scheme for composing façades with the use of sgraffiti, which was brought to Silesia from Ticino (although developed in Tuscany), was based on the division of the wall surface into horizontal strips by means of sgraffito friezes or cornices. These strips were filled with bossages with various motifs which were sometimes quite distant from the stone prototype (the manor house in Luboradz, formerly Dom Płócienników in Lubomierz, now a museum (

Figure 14)).

The third, which was the most common and, at the same time, the simplest way of solving the decoration composition in Silesia, had a Lombard-Ticino origin and consisted of the separation of three zones of sgraffito, i.e., a smooth low pedestal, a frieze strip under the eaves and the main central part filled with a repeating motif of bossages which were treated as a homogeneous patterned fabric in which various sizes of window openings were made without any particular care for keeping the pattern structure intact (town hall in Bolesławiec and Otmuchów, castle in Niemcza, manor house in Gola, tenement house in Otmuchów (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). A slightly different variant of this solution appeared where window casings were used, often filled with stylized floral motifs and candelabra patterns (the manor house in Gorzanów-Raczyn (

Figure 17), the castle in Otmuchów).

A different compositional strategy was used in the case of sgraffito figural decorations. Here, ready-made models developed in Austria and Germany were applied. Depending on the character of the composition, the effect of a sculptural or painting illusion was achieved. In the first case, the façade was divided into horizontal belts, which were filled with sgraffito architectural elements, most often arcaded niches in which sgraffito figures (most often allegorical), presented in sculptural poses, were “set”. The remaining narrower zones were filled with decorations with a frieze motif. In this way, inter alia, the decoration of the façade of the Scholz House in Legnica was solved.

In the second case, the zones separated by narrow cornices were filled with continuous scenes (of biblical, historical or mythological genres), the boundary of which was the length of the façade or the distance between the window openings (barn in Czocha (

Figure 1a,b), castle in Prószków (

Figure 8), Legnica and the house Pod Przepiórczym Koszem and manor house in Zagrodno.

The characteristic way of using sgraffito in Silesia (on a smaller scale also in Austria and Bohemia) featured buildings of medieval origin, e.g., castles and residential towers as well as tenement houses, which began to show a lack of external architectural divisions with the advent of Renaissance fashions. For this reason, they were modernized or remodeled and then covered with sgraffito decorations without which the openings, especially windows, would “float” not be “fastened”, and also in order to organize the often-irregular layout of the façade. This effect was most often achieved by covering the entire wall with a uniform design based on the motif of bossages or by dividing the façade into horizontal belts by means of cornices and friezes.

Apart from secular objects, decorating walls with sgraffito also included, on a scale unprecedented anywhere else outside Silesia, a group of over a hundred Gothic churches. The vast majority of them were covered with sgraffiti with a bossage motif imitating stone cladding and all elements, walls and buttresses, towers and porches were “wrapped” as if with patterned paper. In this group, an interesting case constitutes the church in Gałów (

Figure 18a,b), which was decorated with the motif of a braid used in three variants, mainly as a frieze, but also as a decoration covering buttresses. The braids on the buttresses were positioned with Mannerist perversity, or perhaps only due to the lack of a sense of form, in a vertical layout, which at the same time optically weakened its constructional function.

On the basis of the structure, this time wooden, i.e., wattle and daub as well as timber framing, new unique ways of decorating façades were developed in Silesia. The element which constituted the basis of each decoration, namely relatively narrow moldings or bands, formed a composition surrounding the building, which Grundmann thought of as a

package tied with a string (

Grundmann 1982, vol. 1, p. 130).

Frame compositions were perfectly suitable for combining window openings which were arranged irregularly. Fastening the windows and corners into one organism gave the façades a homogeneous character. On the other hand, by contradicting the laws of structure when joining individual parts of the composition and using elements strongly contrasted with each other, namely thin moldings juxtaposed with large dimensions of buildings and the surface of walls covered with decorations, a Mannerist expression of the whole was obtained in Siestrzechowice (1593) (

Figure 19) and then on the church in Żórawina (1602), on the manor in Niwnica (1618), other ones on the castle in Świny—(before 1622) (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21), on the palace in Stara Kraśnica (

Figure 22) and on the local palace mill (around 1622) as well as on the palace in Dobroszyce (before 1630) (

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003b, pp. 207–18).

The most probable intention seems to transfer this idea from the wattle and daub and timber framing structure, while combining it with the mannerist, non-structural composition of the whole, which was inspired by the fitting ornament. We have here artistic effects characteristic of wooden construction, i.e., a rough texture and color of beams-strips, yellow or red, which is consistent with the colors of wooden elements of buildings erected in Germany at that time and combining it with the abstractness of fitting ornaments and its characteristic details.

Buildings which were covered with frame decorations belonged to people who constituted the Silesian elite of that time. The lord of Siestrzechowice—Andreas von Jerin—was the nephew of the bishop of Wroclaw who had the same name and at the same time the starost of the principality, and his family on the father’s side and uncle came from Swabia. We know Adam von Hanniwald, the owner of Żórawina, who held the title of imperial, archducal, and ducal councilor, as a seasoned collector and patron of the arts. Another individuality was the heir of Świny—Johann Sigismund Schweinichen, on whose tombstone it was written:

In his youth, he traveled through Germany, France, Italy, England and the Netherlands, learning foreign languages, noble arts and chivalrous exercises so much that he was ahead of many of his fellow countrymen. In his male years, he abandoned all worldly pastimes and devoted himself to solitary meditation on the mysteries of God and nature, on which he spent most of his life, and therefore he costly restored and greatly enlarged his home (

Schweinichen 1906, p. 250). Travel around Europe, contacts with the Prague court and the knowledge of art gained from them resulted in a more refined taste and a tendency to introduce innovations.

Summing up, in the territory of Silesia all types of sgraffito decoration compositions developed in Europe were used, apart from the Tuscan grotesque composition. The unique contribution seems to be the frame system, which is presented in the next part of the article.

Let us note, however, for the sake of order that before the appearance of sgraffiti, at the beginning of the first phase of the Silesian Renaissance, newly erected buildings (mainly from burgher foundations) were dominated by the shaping of the façade by means of rich stonework detail with Northern Italian ornamentation and divisions based on the levels of cornices above and below windows. It was only from the middle of 16th century, most probably due to the influx of Ticino, Grisons and Komasków immigrants, that a new façade organization was introduced. Afterwards they began to consciously give up any additional elements, subordinating its structure almost entirely to sgraffito decorations.

5.3. Design

Firstly, it should be emphasized that not all buildings which were erected in Silesia at that time were entirely covered with sgraffiti. The façades of a certain group of objects were colored over a larger area, most often in red (e.g., the manor house in Białobrzezie, called Rothschloss for this reason) or were covered with polychromes (e.g., the Dom Wagi (Libra House) in Nysa). The research also shows that there is a large group of objects on which the original, 16th- or 17th-century plasters have not survived, which eliminates the possibility of drawing any conclusions in their case.

A significant proportion of the types of sgraffito design which were developed by Italy appeared in Silesia. Various Italian ornamental motifs were also widely applied and supplemented with designs from northern Europe after 1570 (

Figure 23,

Figure 24,

Figure 25 and

Figure 26). Only wallpaper models of Lombard provenance and some ornaments, such as anthemions and grotesques, were not widely adopted. Among the preserved figural sgraffiti, we can find both types which are known to us from Austria, Germany and Bohemia and therefore inspired by both sculpture and painting.

In a few cases, we encounter motifs suggesting connections with those coming from Grisons. However, the most commonly represented group is that of the Silesian sgraffito decorations, which used the equivalent of architectural details and construction elements, namely window frames, portals, cornices, friezes, bossages (very differential) (author), as well as coats of arms, sundials and—presented above—wooden wattle and daub and timber framing structures.

5.4. Figural Sgraffiti

Making figural sgraffito decorations required the employment of skilled artisans, i.e., costly artists. Moreover, investors had to be wealthy, educated people, well-versed in art. For this reason, figural decorations in all countries north of the Alps were created less frequently than other types of sgraffiti, mainly in richer towns and on splendid residential buildings outside towns. This regularity is also confirmed in Silesia, where they were to be found mainly on the façades of residences (palaces, manors, and castles) and tenement houses, but also on gates and gatehouses and, in one case, also on the walls of a junior high school. They decorate churches three times and appear indoors twice.

In Silesia, there are 37 sgraffito compositions in which figural motifs appeared, which accounts for approximately 12% of all known decorations created in this area (author).

For comparison, more than eighty figural decorations have survived to this day in the Czech Republic. It was also established that in some regions, such as the Czech-Austrian border, they account for almost half of all sgraffiti. Figural decorations which fill entire façades or constitute a dominant element on their surface, are known from eleven examples only, including the walls of courtyards and farm buildings. Their analysis allows us to draw a conclusion that they were made in this area according to both compositional models used in Europe, i.e., “sculptural” and “painting”, which in several cases are combined within one façade.

Figural compositions, especially those that are better preserved, with a rich content, from the beginning of research on sgraffito, aroused more interest (understandably) than other types of decorations. Thanks to this, they were described in detail and some of them were interpreted even in terms of iconography. This applies to sgraffiti covering the house in Wjazdowa Street in Legnica, which were described synthetically by

Sammter (

1853), and then sgraffiti in Nawojów Łużycki, which were presented in 1867 by Lohde , and also in Legnica—from the house “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem”, which were presented and interpreted by

Hahn (

1912). Years later, Rudkowski returned to this tenement house and supplemented some of Hahn’s findings (

Rudkowski 1967). Shortly thereafter, in his considerations on figural sgraffiti, Rudkowski included the sgraffiti from the “House of Scholz”, which were discovered in 1972 during the renovation of the building (

Rudkowski 1976a,

1976b).

Iconographic programs of Silesian figural sgraffiti are varied. Biblical, allegorical, and mythological scenes are dominant, but there are also battle, genre, and historical ones as well as illustrations of fairy tales. They carry three kinds of messages. Firstly, religious as well as political ideas, which in this respect is justified by the specific religious situation of a large part of Europe, including Silesia, requiring a clear declaration, often with political consequences. Another significant factor was also Luther’s recognition of art as an important element which promoted the

Bible (

sichtbares Wort) and supported the Word of God preached in sermons (

Harasimowicz 1986, pp. 15–24).

The second type of message of figural compositions had a status-related meaning. This group included performances illustrating the activities assigned or even reserved for representatives of a specific status. Among them, we can find, for example, hunting and scenes illustrating military activities (historical, biblical, and sometimes allegorical). For this reason, such scenes were placed on buildings which belonged to the nobility, especially those with an old genealogy, who followed the knightly customs of their ancestors.

Personifications of virtues (cardinal and theological), which were presented in various sets, were often added to them in order to define ideal qualities of household members. When these scenes appeared on bourgeois buildings, and such an example occurs in the tenement house “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem” in Legnica (hunting and military scenes) (

Figure 27 and

Figure 28), we can think about the special ambitions of a wealthy burgher with a high position and influence, aspiring to the status of nobility, perhaps already ennobled and thus manifesting the achievement of the desired status.

There is also the third type of message of figural representations, which was influenced by the special role assigned to education, especially in the humanities, during the Renaissance.

Hence, on the facades of houses and mansions, mythological, historical (preferably ancient) moralizing and allegorical scenes (with various types of personifications, mainly liberal arts) as well as illustrations of fairy tales, intended to reveal the education, reading, knowledge and wisdom of their owners. The compositional analysis of the sgraffiti known to us shows that figural scenes were placed in the area of the façade body and on the gables, whereas the ground floor was most often covered with rustication.

This is indicated by the preserved examples of decorations of the castle in Prószków and the Zagrodno manor. We also know three cases of placing figural representations in the gable zone only (the castle in Oleśnica, manors in Pawłowice and Gorzanów-Raczyn). The decoration of the manor house in Pawłowice (

Figure 29,

Figure 30 and

Figure 31), which was made on two gables, is unique in this group in terms of the richness of the iconographic program.

All scenes and characters were located, as was the case in other countries, in horizontal belts alternating between windows and the inter-window zone, separated by sgraffito or plaster cornices or friezes. In these belts, quadrangular fields for “painting” scenes were separated (the castle in Prószków, the “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem” house in Legnica) or the illusionistic, sgraffito divisions imitating pilasters, columns and arcades were introduced, between which individual and “sculptural” figures were most often “inserted” (houses from Legnica, i.e., “Przepiórczy Kosz” in Legnica (

Figure 27 and

Figure 28 “Scholz House” (

Figure 32,

Figure 33 and

Figure 34) and at 1 Wjazdowa Street). There were also mixed layouts (Pawłowice (

Figure 29), Zagrodno (

Figure 35,

Figure 36 and

Figure 37)). This list, as well as the comparison of the sgraffiti creation dates of different compositional types, proves their simultaneous appearance in the territory of Silesia.

We also meet with figural sgraffiti made on farm buildings (Lwówek, Czocha), where long walls of brick barns, on which compositions several meters long with hunting and genre scenes were placed, were used for decoration. In two cases known to us, figural representations (figures of mercenary foot soldiers and griffins) were connected with the gates leading to the residence (castles in Bolków and Grodno).

On the basis of the remains of sgraffito decorations and information about them, two urban enclaves of figural sgraffiti can be distinguished, namely Lwówek and Legnica. In Lwówek, there are two examples of this type of decoration, but only fragments of one of them, which is also the oldest figural sgraffito composition known in Silesia (at present inside the town hall) to have survived to this day. In Legnica, four groups of figural sgraffiti were found, not counting the portraits on medallions on the façade of the “Budy Śledziowe” (Herring Sheds), two of which have been preserved, i.e., on the “Pod Przepiórczym Koszem” house and on the “House of Scholz” (

Figure 32,

Figure 33 and

Figure 34).

In Silesia, figural decorations were sometimes accompanied by signatures, and even more rarely by inscriptions. Let us remember here that inscriptions were especially popular in Austrian towns, where they were written most often in gothic script in German and placed in decorative frames. On a much smaller scale—also in German—they occurred in southern Czech towns. Their sporadic occurrence in Silesia may be explained—as Rudkowski suggests—by weaker involvement of the Silesian community in the culture of the written word (

Rudkowski 1990, p. 332).

5.5. Technique and Technology of Creation

Writing about the technique and technology of making Silesian sgraffiti and their color is a difficult task since most of the decorations known to us have undergone, sometimes multiple times, conservation treatments, which have partially blurred their original shape. The second problem is the poor state of preservation of many sgraffiti, which makes it difficult to formulate unambiguous opinions. Difficulties are also caused by the ambiguity of the research results concerning the composition of mortars, which differ depending on the adopted method, showing differences of even several dozen percent (

Stec 1997, pp. 22–24). The third and perhaps the most important obstacle is the small number of thoroughly examined objects. For these reasons, it is difficult to find comprehensive and unambiguous summaries today, and the only thing to be presented is a summary of the current state of research on the technology of Silesian sgraffiti (

Stec 1997;

Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003b).

The research shows that Silesian sgraffiti were most often made as a two-layer piece. They consisted of a mortar with a thickness of 0.5 to 4 cm, which was usually placed on the leveling layer. The mortar was smoothed, rolled, and then painted with limewater. There is also one case (in Zagrodno) of making sgraffiti in plaster with two layers with a different composition, thickness and color of each mortar and painted with slaked lime.

About two-thirds of sgraffito decorations of which we know were made on yellowish sand plasters, which were sometimes enriched with various additives (e.g., lime lumps, coarser grains of multi-colored quartz, pieces of hard coal or wood, or ground brick) in order to improve their aesthetic value. In the case of about one third of decorations, most of which were made after 1600, a charcoal-colored plaster was used as the bottom layer, which resulted in shades ranging from silver gray to dark graphite. In a few cases, staining of plasters was used only in those parts of the wall which were directly connected with the decoration. The outer layer was usually coated with slaked lime, although there are known cases of dyeing it an ocher color after 1600. In terms of technology and techniques, a separate group of sgraffiti should include decorations limited only to imitations of architectural detail (window frames, corners, cornices), which were modeled directly on the Ticino solutions and implemented in Silesia by Parrs as well as those sgraffiti whose execution was influenced by the Mannerist method of enrichment by means of painting (frame and scrollwork-fitting sgraffiti).

Decorations from the castle gate in Zagórze seem to be a peculiarity among Silesian sgraffiti, both technological and technical. Their present condition is mainly the result of reconstruction works, which were carried out three times, i.e., in the years 1903–1904, 1957–1958, and in 2015. As a result of the first two actions, a smooth decoration engraved more than 1 cm deep, resembling a relief and placed on a rough background, was obtained. It was developed in two layers of mortar, the bottom—colored dark graphite with a coarse-grained filler—and the top, in the color of natural plaster. Then, both layers were painted; namely, the ornaments and figures were colored various shades of ocher and red; graphite backgrounds were given a gray-cobalt color (this applies to the background under the ornaments of window casing) or dark brick (on the rest of the façade). The coloring of ornaments can be considered consistent with the Mannerist modification of the sgraffito technique (we can see it in Silesia in the case of frame sgraffiti). Doubts, despite the assurances of the authors of the report on the work carried out, are raised by the depth of the engraving, which was unprecedented in the graphite technique and closer to relief. Recent treatments completely eliminated the color diversity, while significantly increasing the depth of the engraving in the undyed sand mortar, which made its further treatment as sgraffito unjustified.

Another technique was adopted for sgraffiti, which consisted only of decorations made of window casings, cornices and corners (the castle in Brzeg, manors in Białobrzezie, Radzików and Słupice). There, the upper 0.5 cm-thick layer of fine-grained mortar, which was directly involved in the execution of the sgraffiti, was applied only in the places where the decorations were made, i.e., around the stone window frames, on the corners and in the places where the sgraffito cornices and moldings were placed. This layer was kneaded, carefully smoothed, then painted white, and then the contours of the decorations were cut out, separating its individual parts with engraved lines, e.g., the components of cornices and windowsills. The remaining wall surfaces were covered with one layer of coarse-grained plaster, which was only slightly rubbed and stained reddish. In this way, the linear, textural, and color separation of the sgraffito drawing was obtained.

5.6. Color

Among the Silesian sgraffiti, we can find examples of two main color sets commonly found in Europe, both white-graphite and white-sand. Apart from the above-mentioned ones, in several places we can still find mortars with a reddish shade which was obtained by adding ground bricks to the plastering mass. Decorations in this color can be found on the walls of the parsonage in Chełmsko Śląskie (

Figure 38c and

Figure 39), the vestibule of the Church of the Virgin Mary and St. George in Oleśnica and in the frieze of the castle in Legnica. The bottom layers of sgraffiti from the manors in Gorzuchów, Pawłowice (

Figure 38b) and Piszkowice (Kłodzko Valley) also have a slightly pinkish color (thanks to the large content of brick and crushed stone). The rich pink sgraffito ornamentation, which once covered the façades of the Oppersdorf castle in Głogówek, which was rebuilt in the years 1586–1594, is known from descriptions only (

Kosian 1931, p. 132). Only fragments of bossages of the plinth part have survived until today, the brighter parts of which are painted here in a brick-pink color.

From the analysis of the decorations made in Silesia, it can be concluded that the most characteristic for this area is the sgraffito engraving, which uses the contrast of the natural color of plaster with the whiteness of limewater. The dark gray color of plaster, which was applied in Italy (in Tuscany and Rome), gained less recognition in Silesia and was used in about one third of buildings. Therefore, the thesis of Kanclerz, which was formulated for sgraffiti in Poland and thus generalized for Silesia, that (…)

in terms of color, black and white sgraffito prevails, was not confirmed (

Kanclerz 1963, p. 317).

The method of making sgraffiti in undyed plasters was developed in the Italian-Swiss border area and, probably thanks to the local sgraffito artists, it spread to Grisons, then to parts of Austria and Bohemia as well as to Southern Germany. On this basis, we can put forward a thesis that the choice of the color of the bottom layer was determined by the direction of sgraffito inspirations; to some extent also, especially at the initial stage, by their contractors’ origin.

Most of the Silesian decorations on plaster stained with charcoal or burnt straw were created after 1600. In terms of color, the exceptions include the Oleśnica sgraffiti on the façades of the castle (

Figure 38a and

Figure 40) and the church porch. They were made of a light-gray-colored plaster (with the help of lumps of charcoal) which was covered with a layer of ocher dye. Sgraffiti from the “House of Scholz” in Legnica are ocher on the umber underlay. The original decorations on the tower of the town hall Bystrzyca Kłodzka were probably also made in a similar set of colors. All of them were made at the beginning of the 17th century when Mannerist trends prevailed in Silesia.

As a result of the research, it was also found that the strips making up the sgraffiti with a frame composition were colored. The applied color compositions refer to the sets typical of wattle and daub construction from Southern Germany. However, no reliable examples of multi-colored sgraffiti made entirely in the sgraffito technique have been found.

Summarizing the research results on the color of Silesian sgraffiti, we can state that they seem to be technologically and technically diverse, although due to the still small number of objects examined in this respect, it is difficult to provide a broader and unambiguous summary. The only ascertainable chronological sequences are connected with the addition of dyes to both sgraffito layers on a larger scale. In the first phase in this respect, in the years 1540–1600, the vast majority of sgraffiti in Silesia were made as two-color decorations in natural sand plaster coated with white limewater.

It can also be claimed that the background of the natural plaster color is connected with the activity of artists from Ticino and Grisons. Only after 1600 did they begin to use additives which dyed the bottom-layer graphite on a larger scale, which previously appeared sporadically. In some cases, the layer was combined with the ocher dye, replacing slaked lime, which can be connected with the strengthening of Mannerist tendencies in art and the arrival of new groups of sgraffito artists in Silesia. We also know examples of sgraffito decorations that were combined with different colored underpaintings from this period.

As a supplement to the findings regarding color, it should be added that sgraffito decorations were accompanied by painted stonework on a scale which is difficult to estimate today, due to damages. They were sometimes colored only to compensate for the shades of the different stones which made up the frames, as indicated by the remnants of polychrome in the color of ocher preserved in the castle in Brzeg. Individual stone elements were also painted in order to emphasize the aesthetic and compositional properties of detail, which is suggested by the red dye discovered on one of the stone casings of the manor in Warta Bolesławiecka, as well as clear traces of multicolored staining of the manor portal in Gola Dzierżoniowska (

Figure 41).

6. Summary

Today, after almost five hundred years have passed since the creation of the sgraffiti adorning the walls of Silesian buildings and structures, their study is quite a challenge. It is extremely urgent as only a “reminiscence” will soon remain of the Silesian sgraffiti—a small group consisting of just over 30 decorations.

The course of research to date allows us to formulate several conclusions as well as research questions. The general conclusion concerns the confirmation of the great popularity of sgraffito decorations in a large part of Europe in the period from the 15th to the mid-17th century (in some Spanish and Portuguese towns, even longer) and in the case of Silesia in the years 1540–1650. In this respect, Silesia was in no way inferior to the neighboring Bohemia and Moravia, where the largest concentration of sgraffito decorations in Europe was recorded, and to other countries or regions in which the sgraffito fashion reigned. It can even be said that for Silesia, sgraffiti constituted an iconic sign of the architecture of the period in question. It should be emphasized that decorating sacred objects, mostly Gothic style, on an unprecedented scale seems to be the Silesian fashion. It was also established that most of the sgraffito decorations in Silesia were financed by the nobility and then by the bourgeoisie.

There are also many indications that sgraffiti first appeared in Silesia thanks to the Parr family, who came from the Ticino Bissone. In the many other cases, the Italian influence was also confirmed.

The reference to the collected comparative material from other European countries allowed us, on the one hand, to show the sources of inspiration (Lombard, Ticino, Grisons, Dutch) for several types of compositions and many decorative motifs, and on the other, to distinguish a group of objects covered with sgraffiti in a unique way and having no analogies outside Silesia, i.e., frame composition and oval bossages.

In terms of the technology and techniques of sgraffito, no differences from those adopted in other European countries were found. However, we found combinations of sgraffiti with polychromes, which was much rarer than in the territory of Italy or Bohemia (

Vojtéchovsky and Waisser 2019;

Weyer and Klein 2019).

Among the research questions, an important, but still poorly recognized topic seems to be concerning the artists and organization of the workshop making sgraffito decorations. In view of the vestigial preservation of sgraffiti in Silesia and in search of more precise and comprehensive answers, we should rely on research conducted in all countries affected by “sgraffito madness”.

The collection and processing of the results of all research on sgraffito decorations subjected to successive conservation treatments not only in Silesia, but also in other countries since the mid-19th century also requires continuation.

There is also a need to exchange experiences on modern methods (

Morkunaite et al. 2019) and sometimes even entire conservation strategies implemented in different countries and in various centers. Educational practice in the scope of heritage restoration and conservation is an obvious factor as there were (and still do exist somewhere) clear local or national schools whose approaches may even conflict with each other. It is important to show how these regional traditions are manifested in the care of sgraffiti.

A broad discussion on the acceptable limits of the reconstruction of sgraffito decorations in the context of their authenticity is also necessary, as well as possible restoration interventions which often have to consider how to deal with the ‘multi-layered’ nature of a particular building. Furthermore, the balance between beauty and authenticity, taking into account our current knowledge about sgraffiti in the light of changing doctrines and conservation ideas, must be understood.

An excellent platform for such collaboration is the cyclical conference initiated by HAWK Hochschule für angewandte Wissenschaft und Kunst in Hildesheim in cooperation with the Niedersächsichen Landesamt für Denkmalpflege. Two meetings for “fans” and experts in this form of wall decoration already took place. The first one occurred in 2017 under the slogan “Sgraffito in Change. Materials, Techniques, Topics, and Preservation”. Its fruit, among other things, is a monograph published under the same title. The organizer of the second one in 2019 was Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci. It was entitled Sgraffito in Change. Original Realization vs. Secondary Interventions (monograph to be published). Researchers from Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Spain, Italy, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland participated in both meetings (

Jagiełło 2019). Further meetings of theoreticians and practitioners involved in the research and conservation of sgraffito decorations are planned.